2025 Analytical Chemistry Research Trends: A Comprehensive Overview of Innovations, Applications, and Sustainable Practices

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current research trends shaping analytical chemistry in 2025, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

2025 Analytical Chemistry Research Trends: A Comprehensive Overview of Innovations, Applications, and Sustainable Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current research trends shaping analytical chemistry in 2025, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores foundational shifts toward sustainable and circular analytical chemistry, examines emerging methodological advances in areas like microextraction and novel sensors, delivers essential troubleshooting and optimization strategies for core techniques like LC and GC, and outlines rigorous frameworks for method validation and comparative analysis to ensure data integrity and promote greener alternatives.

Paradigm Shifts: Embracing Sustainability, Circularity, and Novel Detection Principles

The modern analytical laboratory stands at a crossroads. As global environmental challenges intensify, the traditional "green chemistry" paradigm is evolving toward a more holistic framework that differentiates between mere circularity and true strong sustainability. While green chemistry has successfully raised awareness about reducing hazardous waste and improving efficiency, it often operates within a weak sustainability model that assumes technological advancements and economic growth can compensate for environmental damage [1]. This approach persists in many laboratories where incremental improvements like solvent recycling coexist with fundamentally resource-intensive processes.

A new paradigm is emerging that demands a critical distinction between circularity and sustainability in analytical practice. Circularity focuses primarily on keeping materials in use and minimizing waste through strategies like reagent recovery and instrument repurposing [1]. While valuable, this approach predominantly addresses economic and environmental considerations while often overlooking broader social impacts. In contrast, strong sustainability recognizes ecological limits and planetary boundaries, advocating for practices that not only minimize harm but actively contribute to ecological restoration and social well-being [1]. This framework challenges the very foundation of conventional analytical methods, pushing laboratories toward disruptive innovations rather than incremental improvements.

Positioned within broader research trends in analytical chemistry, this shift reflects the field's growing engagement with sustainability science [1]. The analytical community is increasingly applying its expertise in measurement, quantification, and method development to address complex environmental challenges, moving beyond traditional applications to fundamentally reconsider the environmental footprint of analytical processes themselves. This whitepaper provides a technical framework for differentiating circularity from strong sustainability in laboratory practice, offering practical protocols and assessment tools to guide this essential transition.

Theoretical Foundation: Circularity vs. Strong Sustainability

Conceptual Definitions and Distinctions

The transition to sustainable laboratory practice requires precise understanding of key concepts often used interchangeably but with distinct meanings and implications. Circularity in analytical chemistry describes a system focused on minimizing waste and keeping resources in use for as long as possible through strategies like recycling, recovery, and reuse [1]. This approach primarily operates within the environmental dimension and integrates strong economic considerations through reduced material costs and improved resource efficiency. However, circularity frameworks often underemphasize the social aspect of sustainability, creating an incomplete picture of true sustainable practice.

In contrast, sustainability constitutes a broader, normative concept tied to what societies deem important, with definitions varying across cultures, time, and locations [1]. The contemporary understanding of sustainability integrates the "triple bottom line" framework balancing three interconnected pillars: economic stability, social well-being, and environmental protection [1]. Within this framework, circularity serves as a stepping stone toward sustainability but does not guarantee it, as circular practices might still exceed ecological carrying capacities or create social inequities.

Table 1: Comparative Framework of Laboratory Sustainability Approaches

| Aspect | Green Chemistry | Circularity | Strong Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Reducing hazardous waste & emissions | Minimizing waste & resource loops | Operating within planetary boundaries |

| Economic View | Cost savings through efficiency | Economic value from resource cycling | Economic activities as subordinate to ecological limits |

| Social Dimension | Limited focus on operator safety | Limited social considerations | Explicit emphasis on social well-being & equity |

| Time Perspective | Short-term improvements | Medium-term resource management | Long-term system resilience |

| Innovation Approach | Incremental improvements | Process optimization | Disruptive, system-level redesign |

| Typical Metrics | Waste reduction, energy efficiency | Recycling rates, material circularity | Environmental regeneration, social benefit |

The distinction becomes critically important when assessing current laboratory practices. Analytical chemistry largely operates under a weak sustainability model where natural resources are consumed and waste generated under the assumption that technological progress will compensate for the environmental damage [1]. This model prioritizes performance metrics like analysis speed, sensitivity, and precision while often treating sustainability factors as secondary considerations [1].

Strong sustainability, conversely, acknowledges the existence of ecological limits, carrying capacities, and planetary boundaries [1]. It challenges the presumption that economic growth alone can resolve environmental issues and emphasizes practices and policies aimed at restoring and regenerating natural capital. For the analytical laboratory, this represents a fundamental shift from reducing negative impacts to creating positive ecological and social benefits through analytical practice.

Current Landscape and Assessment of Standard Methods

The urgency of transitioning to strong sustainability becomes evident when examining the current state of standard analytical methods. Recent research assessing the greenness scores of 174 standard methods and their 332 sub-method variations from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias revealed concerning results [1]. Using the widely adopted AGREEprep metric (where 1 represents the highest possible score), 67% of methods scored below 0.2, demonstrating poor greenness performance [1]. These findings highlight how official methods still rely heavily on resource-intensive, outdated techniques that perform poorly on key greenness criteria.

This assessment underscores a critical challenge: many laboratories remain locked into linear "take-make-dispose" models due to regulatory constraints and standardized protocols [1]. The transition to more sustainable practices requires not only technological innovation but also fundamental reform of methodological standards that currently impede progress toward stronger sustainability frameworks.

Practical Implementation: Strategies for the Modern Laboratory

Green Sample Preparation (GSP) Techniques

Sample preparation represents a significant opportunity for improving both circularity and sustainability in analytical workflows. Transitioning from traditional methods to Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles can dramatically reduce environmental impacts while maintaining analytical quality [1]. Key strategies include:

Accelerating Sample Preparation: Applying vortex mixing or assisting fields such as ultrasound and microwaves enhances extraction efficiency and speeds up mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy compared to traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [1]. These approaches typically apply to miniaturized systems that offer additional benefits of reduced sample size and minimized solvent and reagent consumption.

Parallel Processing: Handling multiple samples simultaneously increases overall throughput and reduces energy consumed per sample [1]. Modern automated systems enable parallel processing of numerous samples, making long preparation times less limiting while improving resource efficiency.

Automation: Automated systems save time, lower consumption of reagents and solvents, and consequently reduce waste generation [1]. Additionally, automation minimizes human intervention, significantly lowering risks of handling errors, operator exposure to hazardous chemicals, and laboratory accidents.

Process Integration: Traditional multi-step preparation methods often lead to material loss and increased consumption of energy and chemicals [1]. Streamlining these processes by integrating multiple preparation steps into a single, continuous workflow simplifies operations while cutting down on resource use and waste production.

Sustainable Solvent Selection and Management

Solvent use represents one of the most significant environmental impacts in analytical chemistry. Implementing sustainable solvent management strategies is essential for both circular and sustainable practices:

Ionic Liquids Application: Ionic liquids (ILs) characterized by minimal volatility and tunable physicochemical properties have emerged as viable alternatives for various extraction processes [2]. Their capacity for precise elimination of contaminants from industrial effluent, recyclability for reuse, and reduced energy requirements make them valuable for sustainable method development [2].

Solvent Recovery Systems: Implementing closed-loop solvent recovery systems transforms linear consumption patterns into circular resource flows. Modern distillation and recovery technologies can effectively reclaim high-purity solvents for reuse, reducing both environmental impacts and operational costs.

Alternative Solvent Evaluation: When selecting solvents, laboratories should employ comprehensive assessment tools that evaluate not only technical performance but also environmental, health, and safety parameters across the entire lifecycle.

Table 2: Sustainable Solvent Alternatives for Common Laboratory Applications

| Traditional Solvent | Sustainable Alternative | Key Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane | Terpene-based solvents | Biodegradable, low toxicity | Lipid extraction, chromatography |

| Acetonitrile | Ethanol-water mixtures | Reduced toxicity, renewable source | HPLC mobile phases |

| Hexane | Ionic liquids | Tunable properties, recyclable | Liquid-liquid extraction [2] |

| DMF | Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Biodegradable, low cost | Synthesis, extraction |

| Chloroform | Cyclopentyl methyl ether | Reduced environmental persistence | Pharmaceutical analysis |

Method Validation and Metrics

Quantitatively assessing the sustainability of analytical methods requires robust metrics and validation protocols. Laboratories should implement multi-criteria assessment frameworks that capture environmental, economic, and social dimensions:

Greenness Metrics Tools: The AGREEprep metric provides a comprehensive scoring system (0-1 scale) that evaluates multiple green chemistry principles [1]. Similar tools include the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) and HPLC-EAT for specific techniques.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Implementing full life cycle assessments for analytical methods provides a complete picture of environmental impacts from reagent production through to waste disposal, helping identify hotspots and improvement opportunities.

Social Impact Indicators: Developing metrics to assess social dimensions, including operator safety, community impacts, and accessibility of analytical technologies, represents a critical advancement toward strong sustainability assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Implementing circular and sustainable practices requires specific reagents, technologies, and approaches designed to minimize environmental impacts while maintaining analytical quality. The following toolkit highlights key solutions for modern sustainable laboratories:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Laboratories

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Sustainability Benefit | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Extraction solvents | Low volatility, recyclable, tunable properties | Liquid-liquid extraction for wastewater treatment [2] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green solvents | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable feedstocks | Synthesis of benzimidazole scaffolds [2] |

| Microextraction Devices | Sample preparation | Minimal solvent consumption (μL scale) | Parallel processing of multiple samples |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Sample preparation | Solvent-free extraction, reusable fibers | Automated analysis of volatile compounds |

| Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) | Separation technique | Uses COâ‚‚ instead of organic solvents | Chiral separations in pharmaceutical analysis |

| Portable Analytical Devices | On-site analysis | Reduced sample transport, real-time data | Field-based environmental monitoring |

| 4-Sulfanylbutanamide | 4-Sulfanylbutanamide|Research Chemical | Research-grade 4-Sulfanylbutanamide for laboratory use. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| (4-Aminobutyl)carbamic acid | (4-Aminobutyl)carbamic acid, CAS:85056-34-4, MF:C5H12N2O2, MW:132.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols for Sustainable Practice

Protocol 1: Ionic Liquid-Based Liquid-Liquid Extraction for Wastewater Analysis

This protocol demonstrates the application of recyclable ionic liquids for contaminant removal from wastewater, aligning with both circularity principles (through solvent recovery) and strong sustainability (through reduced ecosystem impacts) [2].

Principle: Ionic liquids (ILs) provide an alternative to volatile organic solvents for extracting contaminants from aqueous samples. Their tunable physicochemical properties allow for selective extraction of different contaminant classes, while their minimal volatility reduces atmospheric emissions [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Hydrophobic ionic liquid (e.g., [C₄MIM][PF₆])

- Aqueous sample containing target contaminants (micropollutants, dyes, or heavy metals)

- Centrifuge tubes (15 mL)

- Centrifuge

- Temperature-controlled mixer

- HPLC or GC system for analysis

Procedure:

- Add 10 mL of wastewater sample to a 15 mL centrifuge tube.

- Add 1 mL of selected ionic liquid to the sample.

- Mix vigorously for 10 minutes at 25°C using a temperature-controlled mixer.

- Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to achieve complete phase separation.

- Carefully separate the ionic liquid phase from the aqueous phase.

- Analyze the aqueous phase to determine extraction efficiency.

- Regenerate the ionic liquid by back-extraction or appropriate treatment for reuse.

Validation Parameters:

- Extraction efficiency for target contaminants

- Ionic liquid recovery rate after regeneration

- Number of reuse cycles without significant performance degradation

- Comparative energy consumption versus conventional methods

Protocol 2: Miniaturized Microwave-Assisted Extraction

This protocol illustrates how miniaturization and alternative energy sources can dramatically reduce solvent consumption and energy use compared to conventional extraction techniques.

Principle: Microwave energy accelerates extraction processes by directly transferring energy to molecules, reducing extraction times and solvent volumes while maintaining extraction efficiency.

Materials and Reagents:

- Microwave-assisted extraction system

- Miniaturized extraction vessels (10 mL)

- Reduced solvent volumes (1-2 mL per sample)

- Multi-sample rack for parallel processing

- Analytical balance

Procedure:

- Weigh 100 mg of sample into microwave extraction vessel.

- Add 2 mL of green solvent (e.g., ethanol-water mixture).

- Seal vessels and place in microwave system.

- Perform extraction at optimized temperature and time (e.g., 80°C for 10 minutes).

- Allow vessels to cool to room temperature.

- Filter extracts directly to analysis vials.

- Analyze using appropriate chromatographic technique.

Validation Parameters:

- Extraction yield compared to conventional methods

- Solvent consumption per sample

- Total energy consumption

- Analysis of co-extracted interferents

Technology Roadmap and Implementation Framework

Strategic Transition Pathways

Implementing strong sustainability in analytical laboratories requires a systematic approach that addresses both technological and organizational dimensions. The following roadmap outlines key transition pathways:

Digital Tools and Emerging Technologies

Advanced digital technologies play an increasingly important role in enabling both circular and sustainable laboratory practices:

AI and Machine Learning: Applications include optimizing chromatographic conditions, predicting method performance, and identifying sustainable solvent combinations [3]. AI algorithms can process large datasets from techniques like spectroscopy and chromatography, identifying patterns that human analysts might miss while optimizing resource efficiency [3].

Internet of Things (IoT): Connected sensors enable real-time monitoring of energy consumption, solvent usage, and waste generation, providing data-driven insights for continuous improvement of environmental performance.

Portable and Miniaturized Devices: The need for on-site testing in fields like environmental monitoring has increased demand for portable and miniaturized devices [3]. Examples include portable gas chromatographs for real-time air quality monitoring, which reduce the need for sample transport and associated environmental impacts [3].

The transition from green to sustainable analytical chemistry represents both an ethical imperative and a practical necessity for modern laboratories. While circularity provides important strategies for reducing waste and maintaining resource value, strong sustainability offers a more comprehensive framework that acknowledges ecological limits and integrates social well-being.

Implementing this transition requires moving beyond incremental improvements to embrace disruptive innovations that fundamentally reconfigure analytical processes. This includes adopting green sample preparation techniques, implementing sustainable solvent systems, applying comprehensive assessment metrics, and fostering collaborations across industry, academia, and regulatory bodies.

The analytical chemistry community has made significant progress in developing greener methods, but much work remains. Current assessments showing poor greenness scores for most standard methods highlight the urgency of this transition [1]. By differentiating circularity from strong sustainability and implementing the strategies outlined in this whitepaper, laboratories can play a crucial role in advancing both scientific knowledge and environmental stewardship, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable future.

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents a transformative, holistic paradigm in modern analytical science, moving beyond the purely environmental focus of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) to integrate analytical performance, ecological sustainability, and practical economic considerations. This whitepaper examines the WAC framework through its foundational RGB model, detailing its implementation via contemporary assessment tools and validated experimental methodologies. Within the broader context of analytical chemistry research trends, WAC establishes a standardized approach for developing methods that are simultaneously analytically superior, environmentally responsible, and practically viable, as evidenced by applications in pharmaceutical, environmental, and food analysis.

The historical development of green chemistry principles aimed primarily at minimizing waste and reducing the use of hazardous substances [4]. While Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) successfully applied these principles to analytical methods, its primary focus remained eco-centric, often overlooking critical parameters of analytical performance and practical implementation [4] [5]. This limitation created a need for a more comprehensive framework.

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), introduced in 2021, emerged as a holistic paradigm designed to overcome this limitation [4] [6]. The term "white" signifies the pure, balanced integration of quality, sensitivity, and selectivity with an eco-friendly and safe approach for analysts [4]. WAC redefines analytical research by embedding principles of validation efficiency, environmental sustainability, and cost-effectiveness into its core, fostering a new era of responsible science [6]. This approach is crucial for fostering truly sustainable and efficient analytical practices in scientific research and beyond, ensuring that environmental improvements do not come at the expense of analytical reliability or practical applicability [4] [5].

The RGB Framework: The Core of WAC

The WAC framework is operationalized through the RGB model, which evaluates analytical methods across three independent dimensions: Red, Green, and Blue [4]. When these three aspects are optimally balanced, the resulting methodology is considered "white" — complete and coherent [4].

The Three Pillars Explained

- Green (Environmental Impact): This dimension encompasses the traditional principles of GAC, focusing on minimizing environmental harm. It evaluates factors such as waste generation, energy consumption, toxicity of reagents, and operator safety [4] [5]. The goal is to prevent waste, use safer chemicals, and design for energy efficiency.

- Red (Analytical Performance): The red dimension ensures that the method's primary analytical function is not compromised. It assesses critical performance parameters including sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision, linearity, and robustness [4] [6]. A method cannot be considered "white" if it is environmentally friendly but fails to deliver reliable, high-quality analytical data.

- Blue (Practical & Economic Factors): This dimension addresses the practical realities of implementing a method in routine laboratories or industrial settings. It considers cost, analysis time, simplicity of operation, ease of automation, and the need for specialized equipment or operator skills [4]. A method that is both green and analytically sound but is prohibitively expensive or complex is not sustainable in practice.

Visualizing the RGB Workflow

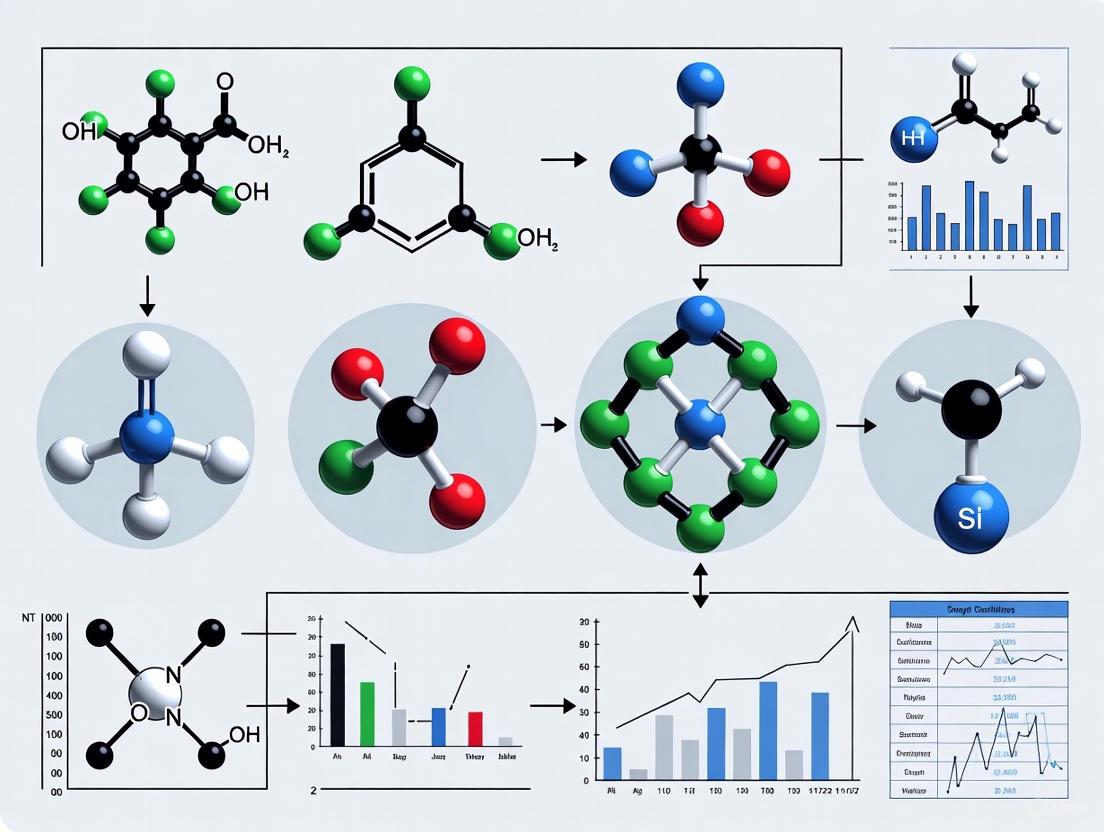

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between the three pillars of WAC and the resulting outcome.

Quantitative Assessment Tools and Metrics

The transition from theoretical framework to practical application is facilitated by a suite of quantitative assessment tools. These metrics allow researchers to score and compare methods, providing a visual and numerical representation of their "whiteness."

Greenness Assessment Tools

Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate the greenness (the "G" in RGB) of analytical methods, each with specific strengths and focuses. The table below summarizes the key greenness assessment tools.

Table 1: Key Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Year | Key Metrics Assessed | Output Format | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale [4] | ~2010 | Reagent toxicity, energy use, waste | Numerical score | >75: Excellent greenness; <50: Unacceptable |

| NEMI (National Environment Methods Index) [4] | ~2000 | Persistence, toxicity, waste volume | Pictogram (4 quadrants) | Simple pass/fail for 4 criteria |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [4] [5] | 2018 | Sample collection, preparation, storage, reagents, waste, instrumentation | Multi-stage pictogram | 5-color scale for each stage (green to red) |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [4] [5] | 2020 | 12 Principles of GAC | Circular pictogram with score | Score 0-1; closer to 1 is greener |

| AGREEprep (for sample preparation) [5] | ~2021 | 10 criteria specific to sample prep | Circular pictogram with score | Score 0-1; closer to 1 is greener |

| AGSA (Analytical Green Star Area) [4] | 2025 | Automation, miniaturization, operator safety | Star-shaped diagram | Larger green area indicates greener method |

The WAC Toolkit: Integrating Red, Green, and Blue

To achieve a true "white" assessment, tools for the red and blue dimensions are equally important. The table below outlines the key tools that complete the WAC toolkit.

Table 2: The Complete WAC Toolkit: RGB Assessment Metrics

| Assessment Dimension | Tool Name & Acronym | Key Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|

| Red (Analytical Performance) | Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) [4] | Reproducibility, trueness, recovery, matrix effects, sensitivity, linearity |

| Blue (Practicality) | Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) [4] | Cost, time, number of analytes, type of analysis, automation, operational simplicity |

| Overall Innovation | Violet Innovation Grade Index (VIGI) [4] | Degree of methodological innovation and novelty |

| Cycloocta[c]pyridazine | Cycloocta[c]pyridazine | High-purity Cycloocta[c]pyridazine for research applications. A valuable scaffold in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Sulfonyldicyclohexane | Sulfonyldicyclohexane|C13H22O2S|Research Chemical | Sulfonyldicyclohexane (C13H22O2S) is a high-purity reagent for catalysis and material science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Case Study: White Analysis of Mn and Fe in Beef

A published case study demonstrates the practical application of WAC principles for the simultaneous determination of Manganese (Mn) and Iron (Fe) in beef samples using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) and Microwave-Induced Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (MP AES) [5]. This method was evaluated against a traditional microwave-assisted digestion and FAAS analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

1. Reagents and Solutions:

- Stock Standard Solutions: 1000 mg Lâ»Â¹ of Fe and Mn.

- Extraction Acids: A mixture of 1.4 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ and 1.2 mol Lâ»Â¹ HCl, prepared from concentrated acids via sub-boiling distillation.

- Dilutions: All dilutions prepared gravimetrically.

- Calibration Ranges: 0.060–5.0 mg kgâ»Â¹ for Fe and 0.015–2.0 mg kgâ»Â¹ for Mn.

2. Sample Preparation:

- Beef samples were defatted, ground, and dried at 103 °C until constant weight.

- The dried samples were ground into a fine powder using a porcelain mortar.

3. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) Procedure:

- Sample Weight: 0.35 g of dry powdered beef was weighed into a 25 mL glass flask.

- Acid Addition: 15.00 g of the mixed acid solution (0.7 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ and 0.6 mol Lâ»Â¹ HCl final concentration) was added.

- Sonication: The flask was placed in a Cole-Parmer 8893 ultrasonic bath (47 kHz) for 10 minutes. Up to 6 samples could be processed simultaneously.

- Cavitation Mapping: The optimal position for sample flasks in the bath was determined using an aluminum foil test to identify the point of highest cavitation activity, ensuring extraction efficiency and reproducibility [5].

- Centrifugation: The resulting suspension was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 28,000 g. The supernatant was used for analytical determination.

4. Analytical Determination:

- Analysis was performed using MP AES, an environmentally friendly technique that uses nitrogen plasma, avoiding the combustible gases required by other atomic spectroscopy methods [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for the UAE/MP AES Method

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ultrasonic Bath (47 kHz) | Provides energy for cavitation, accelerating the extraction process without external heating. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) & Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Diluted acids act as the extractant, dissolving Mn and Fe from the beef matrix. |

| Microwave-Induced Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (MP AES) | Analytical technique for quantification; uses environmentally friendly nitrogen plasma. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) ERM-BB184 | Validates method trueness and precision (Quality Control). |

| Centrifuge | Separates the solid residue from the analyte-containing supernatant after extraction. |

| Coronen-1-OL | Coronen-1-ol (C24H12O) |

| Cyclopenta[kl]acridine | Cyclopenta[kl]acridine|CAS 31332-53-3|RUO |

Workflow Visualization of the UAE Method

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for the UAE method, highlighting its simplicity and efficiency.

WAC Assessment of the Case Study

The application of the RGB model to this case study reveals its strengths as a "white" method [5]:

- Green Dimension: The method scored highly due to the use of diluted (not concentrated) acids, low energy consumption (short time, no heating), minimal waste, and the use of environmentally friendly MP AES.

- Red Dimension: Excellent analytical performance was demonstrated by the accurate and precise quantification of both Mn and Fe, despite their challenging concentration ratio of over 1:100 in beef.

- Blue Dimension: The method is practical, requiring only 10 minutes of extraction, no specialized equipment beyond a common ultrasonic bath, and enables high throughput with the simultaneous preparation of up to 6 samples.

This case proves that it is possible to develop a method that is simple, fast, and green without sacrificing analytical performance, embodying the core principle of WAC [5].

WAC in the Context of Broader Research Trends

White Analytical Chemistry aligns with and supports several key trends in modern analytical research as identified for 2025:

- Demand for Sustainability: The push for environmentally friendly procedures, miniaturized processes, and energy-efficient instruments is a primary driver in the field [3]. WAC provides the framework to quantify and achieve this sustainability without compromising other goals.

- Integration of AI and Automation: Artificial intelligence is being used to optimize chromatographic conditions and enhance data analysis [3]. The Blue dimension of WAC directly assesses the practicality and ease of automation of a method, facilitating this trend.

- Growth of Portable and On-Site Testing: The need for portable devices in environmental monitoring, food safety, and forensics is increasing [3]. These devices are inherently strong in the Blue (practicality) and Green (reduced lab resources) dimensions, making WAC an ideal model for their development.

- Advanced Materials and Techniques: Innovations such as new eco-friendly solvents (e.g., Cyrene), microextraction techniques (e.g., FPSE, CPME), and automated sample preparation are rapidly being adopted [4] [6]. WAC offers a standardized way to evaluate and compare the overall merit of these novel approaches.

The global analytical instrumentation market, estimated at $55.29 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at a CAGR of 6.86%, reaching $77.04 billion by 2030 [3]. This growth is fueled by R&D in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, as well as stringent regulatory requirements—all areas where the balanced, sustainable approach of WAC is increasingly critical.

The field of clinical diagnostics is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by innovations in molecular biology and nanotechnology. Established techniques like quantitative PCR (qPCR) and next-generation sequencing, while powerful, face challenges related to operational costs, sophisticated equipment requirements, and technical limitations in detecting subtle genetic variations or short fragmented nucleotides [7]. In response, three disruptive technologies—CRISPR-Cas systems, aptamers, and nanoscale measurement platforms—are emerging as foundational elements for next-generation diagnostic platforms. These technologies are converging to create biosensing systems with unprecedented sensitivity, specificity, and versatility, enabling detection targets ranging from nucleic acids to small molecules, proteins, and entire pathogens [8] [7]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these emerging biosensing platforms within the context of analytical chemistry research trends, detailing their mechanisms, applications, and implementation protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

CRISPR-Cas Systems in Molecular Diagnostics

Fundamental Mechanisms and Classification

CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins) systems have evolved from a revolutionary gene-editing tool to a powerful diagnostic platform. These systems function as programmable molecular scissors that can be directed to specific nucleic acid sequences with precision. Their utility in diagnostics stems from two primary activities: targeted cleavage of specific sequences and collateral cleavage of surrounding nucleic acids upon target recognition [7].

CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly categorized into two classes based on their effector modules:

Class I Systems (including types I, III, and IV) utilize multiprotein complexes for target recognition. The type III-A systems, such as MORIARTY and SCOPE, represent the primary Class I systems used in biosensing. These complexes recognize target RNA molecules, activating CRISPR polymerases that produce cyclic oligonucleotides (cOAs) as secondary messengers. These cOAs then activate nonspecific RNases that cleave single-stranded RNA fluorophore-quencher pairs, generating detectable fluorescent signals [7].

Class II Systems employ single-protein effectors, making them more suitable for diagnostic applications. This class includes:

- Type II (Cas9): Primarily used for targeted DNA binding and cleavage, often implemented as catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) for diagnostic applications without cleavage [7].

- Type V (Cas12): Targets DNA and exhibits collateral cleavage activity against single-stranded DNA upon target recognition [7].

- Type VI (Cas13): Targets RNA and demonstrates collateral cleavage activity against single-stranded RNA [7].

The collateral cleavage activity of Cas12 and Cas13 proteins is particularly valuable for diagnostic applications, as a single target recognition event can trigger the cleavage of thousands of reporter molecules, providing significant signal amplification [7].

Implementation Platforms and Workflows

The diagnostic application of CRISPR-Cas systems has been realized through several established platforms:

SHERLOCK (Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing) utilizes Cas13 for RNA detection. Upon target recognition, Cas13's collateral cleavage activity degrades reporter RNA molecules, generating a fluorescent signal [7].

DETECTR (DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter) employs Cas12 for DNA detection, with collateral cleavage of single-stranded DNA reporters upon target binding [7].

HOLMES (a one-HOur Low-cost Multipurpose highly Efficient System) combines Cas12 with LAMP amplification for DNA detection [7].

These platforms have demonstrated exceptional performance characteristics during the COVID-19 pandemic, matching the accuracy of PCR tests but with faster turnaround times (typically within 1-2 hours) and the potential for point-of-care application [7].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR Diagnostic Platforms

| Platform | Cas Protein | Target | Detection Limit | Time to Result | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHERLOCK | Cas13 | RNA | Attomolar range | 1-2 hours | Viral pathogens (SARS-CoV-2, Zika, Dengue) |

| DETECTR | Cas12 | DNA | Attomolar range | 30-45 minutes | HPV, SARS-CoV-2, bacterial pathogens |

| HOLMES | Cas12 | DNA | Attomolar range | 1 hour | Nucleic acid targets, SNP detection |

| MORIARTY | Type III-A | RNA | Not specified | Variable | Research applications |

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Based Detection of Viral RNA

Principle: This protocol utilizes the Cas13-based SHERLOCK platform for detecting specific viral RNA sequences through collateral cleavage of fluorescent reporters [7].

Materials:

- Purified Cas13 protein

- Custom-designed crRNA targeting viral sequence

- Fluorescently quenched RNA reporter molecule

- Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) reagents

- Fluorescence plate reader or lateral flow strip

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract RNA from patient sample (saliva, nasopharyngeal swab).

- Nucleic Acid Amplification: Perform isothermal RPA amplification (37°C for 15-20 minutes) to enhance detection sensitivity.

- CRISPR Reaction Setup:

- Combine 10 μL amplified product with 10 μL reaction mix containing:

- 200 nM Cas13 protein

- 200 nM crRNA

- 100 nM fluorescent RNA reporter

- Reaction buffer

- Combine 10 μL amplified product with 10 μL reaction mix containing:

- Incubation and Detection:

- Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes

- Measure fluorescence using plate reader or visual readout via lateral flow strip

Validation: Include appropriate positive and negative controls. The assay should demonstrate 95% positive predictive agreement and 100% negative predictive agreement compared to reference methods [7].

Aptamers as Versatile Recognition Elements

Selection and Engineering of Aptamers

Aptamers are synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind to specific targets with high affinity and specificity through defined three-dimensional structures. These molecules are selected through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment (SELEX), an iterative process that screens combinatorial oligonucleotide libraries containing up to 10^15 unique sequences [9] [10].

The SELEX process consists of three core steps repeated over 5-20 cycles:

- Incubation: A randomized oligonucleotide library is incubated with the target molecule.

- Partitioning: Target-bound sequences are separated from unbound sequences.

- Amplification: Recovered sequences are amplified via PCR (for DNA) or RT-PCR (for RNA) for subsequent selection rounds [10].

Advanced SELEX methodologies have been developed to enhance efficiency and success rates:

- Microfluidic SELEX (M-SELEX): Utilizes microfluidic chips for rapid separation of high-affinity aptamers [9].

- PhotoSELEX: Incorporates photoactivatable nucleotides that form covalent bonds with targets upon irradiation, reducing selection rounds and improving specificity [10].

- Cell-SELEX: Uses whole cells as targets to generate aptamers against native cell surface markers [9].

- In vivo SELEX: Conducts selection within living organisms to identify aptamers with optimal in vivo performance [9].

Aptamers offer several advantages over antibodies as recognition elements, including superior stability, minimal batch-to-batch variation, ease of modification, and non-immunogenicity [9]. Their relatively small size (5-30 kDa) enables better tissue penetration compared to antibodies [9].

Structure and Modification Strategies

Aptamers fold into diverse three-dimensional structures including stem-loops, pseudoknots, G-quadruplexes, and three-way junctions [10]. This structural diversity enables precise molecular recognition through various interactions including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions [10].

To enhance stability and performance, various modification strategies have been developed:

- Backbone Modifications: Incorporation of 2'-fluoro, 2'-amino, or 2'-O-methyl groups improves nuclease resistance [11].

- Spiegelmers: Use of L-ribose nucleotides (mirror-image forms) creates complete nuclease resistance [11].

- End Capping: Addition of inverted thymidine or other blocking molecules at the 3' end prevents exonuclease degradation [9].

- SOMAmers (Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamers): Incorporation of modified nucleotide bases with functional groups (e.g., benzyl, naphthyl) enhances affinity and expands target range [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Aptamer Modification Technologies

| Modification Type | Key Features | Advantages | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2'-Fluoro/2'-O-Methyl | Sugar modification | Enhanced nuclease resistance, maintained binding affinity | Pegaptanib (Macugen) |

| Spiegelmers | L-nucleotides (mirror image) | Complete nuclease resistance, minimal immunogenicity | NOX-E36 (anti-CCL2 for diabetic nephropathy) |

| SOMAmers | Side chain modifications | Expanded chemical diversity, improved affinity for challenging targets | SOMAscan proteomic platform |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) | Bridged nucleic acids | High thermal stability, superior mismatch discrimination | Research applications |

Experimental Protocol: SELEX for Protein-Targeting Aptamer Selection

Principle: Isolation of high-affinity DNA aptamers against a specific protein target through iterative selection and amplification [10].

Materials:

- Single-stranded DNA library (randomized 40-60 nt region flanked by constant primer binding sites)

- Purified target protein

- Negative selection targets (related proteins, selection matrix)

- PCR reagents with biotinylated primers

- Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads

- Binding buffer (optimized for ionic strength and pH)

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Synthesize initial DNA library (10^14 molecules) and amplify by PCR.

- Negative Selection: Incubate library with negative selection targets or bare matrix for 30 minutes, collect unbound sequences.

- Positive Selection:

- Incubate pre-cleared library with target protein (1-100 nM) for 45-60 minutes in binding buffer.

- Separate protein-bound sequences from unbound using filtration, EMSA, or magnetic separation.

- Recovery and Amplification:

- Elute bound sequences (heat denaturation or specific elution buffers).

- Amplify by PCR using biotinylated primers.

- Generate single-stranded DNA using streptavidin bead separation.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for 8-15 rounds with increasing selection stringency (reduced incubation time, increased wash stringency, decreased target concentration).

- Cloning and Sequencing: Clone final pool and sequence individual candidates.

- Characterization: Synthesize candidate aptamers and determine binding affinity (Kd) via methods like surface plasmon resonance or filter binding.

Critical Parameters:

- Buffer composition must mimic intended application conditions [10].

- Include appropriate controls to monitor selection progress.

- Use counter-selection steps to eliminate non-specific binders.

Integration of Aptamers with CRISPR-Cas Systems

Hybrid Biosensing Architectures

The integration of aptamers with CRISPR-Cas systems creates powerful biosensing platforms that extend detection capabilities beyond nucleic acids to include a wide range of analytes. These hybrid systems function by converting the presence of non-nucleic acid targets into programmable nucleic acid sequences that can activate CRISPR-based detection [8].

Several innovative mechanisms enable this signal conversion:

- Direct Detection: Aptamers directly conjugated to activators of CRISPR systems trigger detection upon target binding [8].

- Lock Activation: Target binding induces conformational changes in aptamer structures, activating CRISPR systems that were previously inhibited [8].

- Sandwich Design: Multiple aptamers recognizing different epitopes of the same target create complexes that activate CRISPR detection [8].

- Induction of Conformations: Aptamer switching between different structural states generates activators for CRISPR systems [8].

- Split Aptamers: Target binding facilitates the assembly of split aptamer fragments, creating functional CRISPR activators [8].

These integrated systems have been successfully applied to detect diverse targets including ions, small molecules, proteins, cells, bacteria, and viruses, significantly expanding the application range of CRISPR diagnostics [8].

Experimental Protocol: Aptamer-CRISPR Platform for Small Molecule Detection

Principle: This protocol describes a lock activation approach where small molecule binding to an aptamer triggers the release of a DNA activator for Cas12a detection [8].

Materials:

- Cas12a protein and crRNA complex

- Single-stranded DNA reporter (fluorophore-quencher)

- Designer aptamer-switch construct (aptamer sequence linked to inhibitor sequence)

- Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) reagents

- Target small molecule samples

Procedure:

- Aptamer-Switch Design:

- Design a DNA construct containing: (i) the small molecule-binding aptamer sequence, (ii) a complementary inhibitor sequence that blocks the Cas12a activator, and (iii) a Cas12a activator sequence released upon target binding.

- Sample Incubation:

- Mix 50 μL sample containing target molecule with 10 μL aptamer-switch construct (100 nM).

- Incubate at 25°C for 20 minutes to allow target binding and activator release.

- CRISPR Detection:

- Add 10 μL of the reaction mixture to 30 μL Cas12a detection mix containing:

- 50 nM Cas12a

- 75 nM crRNA

- 200 nM ssDNA reporter

- Reaction buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 45 minutes.

- Add 10 μL of the reaction mixture to 30 μL Cas12a detection mix containing:

- Signal Measurement:

- Monitor fluorescence development using a plate reader or portable fluorometer.

- Alternatively, use lateral flow strips for visual detection.

Applications: This method has been successfully implemented for detection of various small molecules including toxins (microcystin-LR), pharmaceuticals, and metabolites with sensitivities in the nanomolar to picomolar range [8].

Nanoscale Rulers and Measurement Platforms

Advanced Nanoscale Detection Modalities

Nanoscale measurement platforms leverage unique phenomena at the nanoscale to enable highly sensitive detection of biomolecular interactions. These technologies provide "molecular rulers" that can measure distances, interactions, and concentrations with exceptional precision.

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) utilizes noble metal nanoparticles (gold, silver) that exhibit coherent oscillation of free electrons when excited by incident light at specific wavelengths. Changes in the local dielectric environment induced by biomolecular binding cause shifts in the LSPR wavelength (Δλ), enabling sensitive detection [12]. Key advantages include label-free detection, high sensitivity to surface binding events, and compatibility with miniaturized platforms [12].

Bipolar Electrochemistry employs conductive materials that couple redox reactions at their opposite poles when placed in a potential gradient. In closed bipolar electrochemistry (CBE) systems, electron transfer reactions in an analytical cell are coupled to optical readout systems in a separate reporter cell, enabling physical segregation of detection and readout steps to minimize background interference [12]. Optical readout strategies include:

- Electrochromic Readout: Electron transfer produces colorimetric changes (e.g., methyl viologen color shift) [12].

- Electrofluorigenic Readout: Redox reactions generate fluorescent signals (e.g., conversion of resazurin to resorufin) [12].

- Electrochemical Plasmon Readout: Galvanic electrodeposition shifts LSPR wavelength to monitor reactions [12].

Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs) are nanophotonic structures that confine light to zeptoliter volumes, enabling single-molecule observation in real time by reducing the observation volume below the diffraction limit of light [12]. This technology is particularly valuable for studying biomolecular interactions and enzymatic activities at single-molecule resolution.

Nanoscale Reference Materials and Standardization

The development of reliable nanoscale diagnostics depends on the availability of well-characterized reference materials to ensure measurement accuracy and reproducibility. Nanoscale reference materials (RMs), certified reference materials (CRMs), and reference test materials (RTMs) play crucial roles in method validation, instrument calibration, and quality control [13].

Key parameters requiring characterization in nanodiagnostics include:

- Particle size, size distribution, and shape

- Surface chemistry and charge

- Composition and crystal structure

- Specific surface area

- Dispersion stability and agglomeration state [13]

International standardization efforts are led by organizations including ISO, IEC, ASTM International, and the OECD, which develop consensus standards for nanomaterial characterization. However, regulatory approval of nanomaterials faces challenges due to varying definitions of nanomaterials across jurisdictions, differing in size thresholds (1-100 nm typically) and measurement methods [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Emerging Diagnostic Platforms

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Suppliers/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Enzymes | Cas9, Cas12a, Cas13a | Programmable nucleic acid recognition and cleavage | Sherlock Biosciences, Mammoth Biosciences [7] |

| Guide RNAs | crRNA, sgRNA | Target specificity for CRISPR systems | Integrated DNA Technologies, Synthego [7] |

| Aptamer Libraries | Random DNA/RNA libraries, Modified nucleotide libraries | Source for SELEX selection | TriLink BioTechnologies, Baseclick [9] |

| Signal Reporters | Fluorophore-quencher oligonucleotides, Electrochemical reporters | Detection of binding/catalytic events | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher [8] [7] |

| Isothermal Amplification | RPA, LAMP kits | Nucleic acid amplification without thermal cycling | TwistDx, New England Biolabs [7] |

| Nanoplasmonic Materials | Gold nanoparticles, Silver nanoplates | LSPR-based detection platforms | nanoComposix, Sigma-Aldrich [12] |

| Reference Materials | Gold nanoparticles, Polystyrene beads | Method validation and calibration | National Institute of Standards and Technology, JRC Nanomaterials Repository [13] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 4: Comprehensive Comparison of Emerging Diagnostic Platforms

| Parameter | CRISPR-Based Detection | Aptamer-Based Sensors | Nanoplasmonic Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Attomolar range for nucleic acids [7] | Nanomolar to picomolar for proteins [9] | Picomolar range for proteins [12] |

| Assay Time | 1-2 hours (including amplification) [7] | Minutes to hours (varies by format) | Minutes (real-time binding) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate (limited by reporter options) | High (multiple aptamer sequences) | Moderate (spatially encoded arrays) |

| Target Range | Primarily nucleic acids, expanding via aptamer integration [8] | Extensive: ions, small molecules, proteins, cells [9] | Primarily proteins, nucleic acids, cellular targets |

| Equipment Needs | Moderate (isothermal incubation, fluorescence detection) | Low to moderate (varies by transduction method) | High (spectroscopic instrumentation) |

| Point-of-Care Potential | High (lateral flow formats) [7] | High (various biosensor formats) [10] | Moderate (miniaturization challenges) |

| Cost per Test | Low to moderate | Low (after development) | Moderate to high |

| Commercialization Status | Emerging (SHERLOCK, DETECTR) [7] | Established and emerging (SOMAscan, aptamer-based assays) [11] | Research phase with some commercial systems |

The convergence of CRISPR-Cas systems, aptamers, and nanoscale measurement platforms represents a paradigm shift in clinical diagnostics, enabling detection capabilities that were previously unimaginable. These technologies individually offer unique advantages—CRISPR provides unprecedented specificity and signal amplification, aptamers deliver remarkable versatility in target recognition, and nanoscale platforms enable ultra-sensitive measurement of molecular interactions. However, their true potential emerges through integration, as demonstrated by aptamer-CRISPR hybrid systems that combine the target diversity of aptamers with the detection power of CRISPR [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these emerging platforms offer powerful tools for biomarker discovery, therapeutic monitoring, and point-of-care diagnostics. The field is rapidly evolving, with ongoing advances in CRISPR enzyme engineering, aptamer selection methodologies, and nanofabrication techniques promising even more capable diagnostic systems in the near future. As these technologies mature and overcome current challenges related to standardization and regulatory approval, they are poised to fundamentally transform the landscape of clinical diagnostics and personalized medicine.

Advanced functional materials are revolutionizing the field of analytical chemistry by providing unprecedented capabilities in separation, detection, and sensing. Among these materials, boron nitride nanosheets (BNNS) and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) have emerged as particularly promising platforms due to their exceptional properties and versatile applications. BNNS, two-dimensional materials composed of boron and nitrogen atoms arranged in hexagonal lattices, offer remarkable thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties that make them ideal for demanding analytical environments [14]. Meanwhile, MIPs represent a biomimetic approach to molecular recognition, creating synthetic polymers with tailor-made binding sites that exhibit antibody-like specificity for target molecules [15] [16]. The integration of these materials into analytical systems enables enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and stability across various applications including pharmaceutical analysis, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of both material systems, detailing their fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, characterization techniques, and analytical applications. Special emphasis is placed on recent advancements and experimental protocols that facilitate the effective implementation of these materials in cutting-edge analytical chemistry research.

Boron Nitride Nanosheets (BNNS) in Analytical Chemistry

Fundamental Properties and Characteristics

Boron nitride nanosheets belong to the family of two-dimensional materials and are characterized by their exceptional combination of physical and chemical properties that make them highly suitable for analytical applications:

Structural Characteristics: BNNS feature a hexagonal lattice structure similar to graphene but with alternating boron and nitrogen atoms, creating a highly stable and inert material [14]. This structure contributes to their impressive thermal stability, maintaining integrity at temperatures up to 800°C in oxidizing atmospheres.

Mechanical Properties: BNNS exhibit remarkable mechanical strength with a high elastic modulus (approximately 0.7-1.0 TPa) and tensile strength, making them ideal for composite materials and durable sensors [14]. Recent molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that the armchair configuration of BNNS possesses higher elastic modulus irrespective of stacking sequence and applied strain rate [17].

Thermal Conductivity: The in-plane thermal conductivity of BNNS ranges from 200-500 W/mK, enabling efficient heat dissipation in analytical devices and enhancing signal stability in thermal-based detection methods [18].

Electrical Insulation: Unlike graphene, BNNS are electrical insulators with a wide bandgap (5-6 eV), making them excellent dielectric materials for electronic applications and preventing interference in electrochemical sensing platforms [14] [18].

Table 1: Key Properties of Boron Nitride Nanosheets Relevant to Analytical Applications

| Property | Value Range | Analytical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Conductivity | 200-500 W/mK | Heat dissipation in analytical devices |

| Young's Modulus | 0.7-1.0 TPa | Mechanical stability in sensors |

| Band Gap | 5-6 eV | Electrical insulation in electrochemical systems |

| Specific Surface Area | 300-500 m²/g | Enhanced loading capacity for analytes |

| Oxidation Temperature | >800°C | Stability in harsh analytical conditions |

Synthesis Methodologies

Various synthesis approaches have been developed for BNNS production, each offering distinct advantages for analytical applications:

Top-Down Synthesis Methods

Top-down methods involve exfoliating bulk hexagonal boron nitride into nanosheets:

Liquid-Phase Exfoliation: This method utilizes solvent-assisted ultrasonic treatment to separate BN layers through cavitation forces. Common solvents include N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), dimethylformamide (DMF), and isopropanol, with optimal concentration ranges of 0.1-1 mg/mL [14]. The process typically involves probe sonication at 200-500 W for 2-8 hours followed by centrifugation at 3,000-10,000 rpm to remove unexfoliated material.

Mechanical Exfoliation: Using shear forces generated by ball milling or high-shear mixers, this method can produce BNNS with controlled thickness. Ball milling parameters typically involve rotation speeds of 300-600 rpm for 20-50 hours with grinding aids such as sodium hydroxide or urea [14].

Ion-Intercalation Assisted Exfoliation: Alkali metal ions (Li+, K+) or ammonium compounds are inserted between BN layers to weaken interlayer interactions, followed by mild sonication or stirring. Lithium intercalation typically uses n-butyllithium in hexane at room temperature for 24-48 hours [14].

Bottom-Up Synthesis Methods

Bottom-up approaches build BNNS from molecular precursors:

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): This method enables large-area, high-quality BNNS growth on catalytic substrates such as copper or nickel foils [18]. Typical parameters involve boron-containing precursors (borazine, ammonia borane) at temperatures of 800-1100°C under controlled atmospheres. Advanced CVD techniques now enable production of BNNS with controlled layer numbers and minimal defects.

Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis: Using autoclave reactors at temperatures of 150-300°C and autogenous pressure, this method provides good control over BNNS morphology. Common precursors include boric acid and urea with reaction times of 12-24 hours [14].

Analytical Applications

BNNS have found diverse applications in analytical chemistry:

Gas Sensing: BNNS functionalized with specific recognition elements exhibit excellent sensitivity to gases such as NO₂, NH₃, and CO at parts-per-million levels, with response times under 60 seconds [14] [18]. The insulating properties prevent current leakage, enhancing signal-to-noise ratios.

Thermal Management in Analytical Devices: BNNS-polymer composites effectively dissipate heat in miniaturized analytical systems, maintaining temperature stability in microfluidic separation devices and high-performance liquid chromatography systems [18].

Energy Storage for Portable Analytical Systems: BNNS-enhanced electrodes in supercapacitors and batteries provide power sources for field-deployable analytical instruments, offering improved cycle life and energy density [18].

Solid-Phase Extraction: BNNS-functionalized substrates efficiently extract organic contaminants and biomolecules from complex matrices, with recovery rates exceeding 85% for compounds like bisphenol A and pharmaceuticals [14].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) in Analytical Chemistry

Fundamental Principles and Recognition Mechanisms

Molecularly imprinted polymers are synthetic polymers possessing specific recognition sites complementary to target molecules in shape, size, and functional group orientation [15] [16]. The molecular imprinting process involves arranging functional monomers around a template molecule followed by polymerization and template removal, creating cavities with specific molecular recognition capabilities.

Three primary imprinting approaches have been developed:

Covalent Imprinting: Pioneered by Wulff, this method utilizes reversible covalent bonds between template and functional monomers [16]. While providing homogeneous binding sites, the approach requires chemical derivatization of templates and exhibits slow binding kinetics.

Non-covalent Imprinting: Developed by Mosbach, this approach relies on self-assembly of template and monomers through hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects [16]. This method offers greater versatility but may produce binding site heterogeneity.

Semi-covalent Imprinting: This hybrid approach combines covalent imprinting with non-covalent rebinding, offering the stability of covalent chemistry during polymerization and the operational convenience of non-covalent interactions during analysis [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Imprinting Approaches

| Parameter | Covalent | Non-covalent | Semi-covalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Homogeneity | High | Moderate | High |

| Template Versatility | Low | High | Moderate |

| Binding Kinetics | Slow | Fast | Fast |

| Template Removal | Difficult | Easy | Moderate |

| Common Applications | Specialty chemicals | Pharmaceuticals, environmental analysis | Biomolecules, chiral separation |

Synthesis Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Bulk Polymerization Protocol

For general MIP synthesis targeting small molecules (e.g., pharmaceuticals, pesticides):

Pre-polymerization Mixture Preparation: Dissolve template (0.1-0.5 mmol), functional monomer (0.4-2.0 mmol), and cross-linker (2.0-5.0 mmol) in porogenic solvent (5-10 mL) [15] [16]. Common functional monomers include methacrylic acid (for basic templates), 4-vinylpyridine (for acidic templates), and acrylamide (for neutral templates). Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) and trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TRIM) are frequently used cross-linkers.

Polymerization Initiation: Degas the mixture by purging with nitrogen or argon for 5-10 minutes. Add free-radical initiator such as azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 0.01-0.05 mmol) and initiate polymerization either thermally (50-60°C for 12-24 hours) or photochemically (UV light at 365 nm for 1-2 hours) [16].

Template Removal: Grind the polymer block and sieve to desired particle size (typically 25-50 μm). Extract template using Soxhlet extraction with methanol-acetic acid (9:1 v/v) for 24-48 hours, followed by washing with pure methanol to remove acetic acid [15].

Nanoparticle Synthesis via Precipitation Polymerization

For nanoMIPs with improved binding kinetics and application compatibility:

Monomer Solution Preparation: Dissolve template (0.05-0.2 mmol), functional monomer (0.2-0.8 mmol), and cross-linker (1.0-3.0 mmol) in acetonitrile or toluene (50-100 mL) [19]. The higher solvent volume promotes precipitation of nanoparticles during polymerization.

Polymerization Conditions: Add AIBN initiator (0.5-2.0 mol% relative to double bonds) and heat at 60°C with stirring at 150-200 rpm for 12-24 hours. NanoMIPs precipitate during the reaction and can be collected by centrifugation at 10,000-15,000 rpm for 20 minutes [19].

Template Extraction: Wash nanoparticles sequentially with methanol-acetic acid (9:1 v/v), methanol, and deionized water through centrifugation-redispersion cycles. Final product can be lyophilized for storage or dispersed in appropriate buffer [19].

Advanced MIP Formats for Analytical Applications

Stimuli-Responsive MIPs

Smart MIPs that respond to environmental changes enable controlled release and enhanced analytical capabilities:

pH-Responsive MIPs: Incorporate functional monomers with ionizable groups (e.g., acrylic acid, 4-vinylpyridine) that change conformation with pH, triggering template release at specific pH values [15]. Applications include gastrointestinal-targeted drug delivery and sample preparation with pH-selective extraction.

Thermo-Responsive MIPs: Utilize monomers such as N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) that undergo conformational changes at specific temperatures (typically 30-35°C) [16]. These enable temperature-controlled extraction and release in analytical sample preparation.

Photo-Responsive MIPs: Incorporate azobenzene or spiropyran derivatives that change conformation upon light irradiation, allowing remote-controlled molecular recognition [16].

MIP-Based Composite Materials

Magnetic MIPs: Combine MIPs with magnetic nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) for rapid separation using external magnets, significantly simplifying sample preparation [20]. Synthesis typically involves coating magnetic nanoparticles with silica followed by MIP layer formation through surface-initiated polymerization.

MIP-Coated Sensors: Deposit MIP layers on transducer surfaces (QCM, SPR, electrochemical electrodes) for specific analyte recognition with direct signal transduction [20]. Coating methods include electropolymerization, drop-casting, and in-situ polymerization.

Integrated BNNS-MIP Systems and Hybrid Approaches

The combination of BNNS and MIPs creates synergistic materials with enhanced analytical performance:

BNNS-MIP Composite Fabrication

A representative protocol for creating BNNS-MIP core-shell structures:

BNNS Functionalization: Treat BNNS (50 mg) with oxygen plasma or acid oxidation to create surface hydroxyl groups. React with 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate (1% v/v in toluene) at 70°C for 12 hours to introduce polymerizable vinyl groups [14].

Surface-Initiated Polymerization: Prepare pre-polymerization mixture containing template (0.1 mmol), functional monomer (0.4 mmol), cross-linker (2.0 mmol), and initiator (AIBN, 0.02 mmol) in acetonitrile (20 mL). Add functionalized BNNS (20 mg) and initiate polymerization at 60°C for 24 hours with agitation [16].

Characterization and Validation: Confirm composite formation using TEM, FTIR, and TGA. Evaluate binding capacity through batch adsorption experiments and compare with non-imprinted control composites.

Analytical Performance of BNNS-MIP Hybrids

Integrated BNNS-MIP systems demonstrate enhanced performance in various analytical applications:

Enhanced Thermal Stability: BNNS core improves composite stability up to 400°C, enabling applications in high-temperature environments [14].

Improved Binding Kinetics: The high surface area of BNNS (300-500 m²/g) provides increased binding site accessibility, reducing equilibrium time from hours to minutes for some analytes [14].

Mechanical Robustness: BNNS reinforcement extends MIP operational lifetime, with composites maintaining recognition capability after >100 extraction cycles [14].

Experimental Protocols for Analytical Applications

BNNS-Based Solid-Phase Extraction for Environmental Analysis

Objective: Extract and preconcentrate pharmaceutical residues from water samples using BNNS sorbents.

Materials: BNNS (commercially available or synthesized), C18 cartridge housings, water samples, HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile, target pharmaceuticals (e.g., diclofenac, ibuprofen, carbamazepine).

Procedure:

- Column Preparation: Pack BNNS (50 mg) into empty SPE cartridges between polypropylene frits.

- Conditioning: Pre-wet with methanol (5 mL) followed by deionized water (5 mL) at flow rate of 1-2 mL/min.

- Sample Loading: Pass water sample (100-500 mL, pH adjusted to 7.0) through cartridge at 3-5 mL/min.

- Washing: Remove interferences with water:methanol (95:5 v/v, 5 mL).

- Elution: Collect analytes with methanol (5 mL) containing 1% acetic acid.

- Analysis: Concentrate eluent under nitrogen stream and analyze by HPLC-MS/MS.

Performance Metrics: Recovery rates typically exceed 85% with RSD <8%, and detection limits of 0.1-5 ng/L achievable [14].

MIP-Based Sensor for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Objective: Develop electrochemical sensor for therapeutic drug monitoring using MIP recognition elements.

Materials: Glassy carbon electrode, MIP nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, Nafion solution, phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4), target drug solution (e.g., theophylline, antiepileptics).

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Polish glassy carbon electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) and wash thoroughly.

- MIP Immobilization: Mix MIP nanoparticles (5 mg/mL) with Nafion solution (0.5% in ethanol) and deposit 10 μL on electrode surface. Dry at room temperature.

- Binding Experiment: Immerse modified electrode in sample solution containing target analyte for 15-30 minutes with gentle stirring.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Transfer electrode to clean measurement cell containing supporting electrolyte. Perform differential pulse voltammetry from -0.2 to +0.8 V.

- Quantification: Measure oxidation current and correlate with calibration curve.

Performance Metrics: Typical detection limits of 1-10 nM, with linear range of 10 nM - 10 μM, and selectivity coefficients >10 against structurally similar compounds [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BNNS and MIP Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hexagonal Boron Nitride (h-BN) Powder | Precursor for BNNS synthesis | Particle size <10 μm recommended for efficient exfoliation |

| N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | Solvent for BNNS exfoliation | Enables high-yield production of few-layer BNNS |

| Borazine | CVD precursor for BNNS | Requires careful handling under inert atmosphere |

| Methacrylic Acid | Functional monomer for MIPs | Ideal for templates with basic functional groups |

| Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Cross-linker for MIPs | Provides mechanical stability to imprinted cavities |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Polymerization initiator | Thermal decomposition at 60-70°C |

| 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate | Coupling agent for composites | Enables covalent bonding between BNNS and polymers |

| Trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TRIM) | High-crosslinking monomer | Creates rigid MIP structures with improved selectivity |

| Acridine-4-sulfonic acid | Acridine-4-sulfonic acid, CAS:861526-44-5, MF:C13H9NO3S, MW:259.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 8-Bromo-3'-guanylic acid | 8-Bromo-3'-guanylic acid|High-Purity Research Compound | 8-Bromo-3'-guanylic acid is a guanosine monophosphate analog for biochemical research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

BNNS Synthesis and Functionalization Pathways

MIP Development and Implementation Workflow

BNNS-MIP Composite Synergy in Analytical Systems

Boron nitride nanosheets and molecularly imprinted polymers represent two complementary advanced materials that are transforming analytical chemistry practices. BNNS provide exceptional thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties that enhance the stability and performance of analytical systems, while MIPs offer biomimetic molecular recognition capabilities that rival natural antibodies. The integration of these materials creates synergistic composites with enhanced analytical performance.

Future research directions include developing more sustainable synthesis methods, improving the homogeneity of MIP binding sites, enhancing the functionalization strategies for BNNS, and creating intelligent responsive systems that adapt to analytical environments. As these materials continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly play increasingly important roles in addressing complex analytical challenges across pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical domains.

The experimental protocols and fundamental principles detailed in this technical guide provide researchers with the foundational knowledge required to implement these advanced materials in their analytical workflows, contributing to the ongoing advancement of analytical science.

Technological Frontiers: Microextraction, Hyphenated Techniques, and Advanced Instrumentation

Modern Microextraction Techniques for Exposome Research and Biomonitoring

The exposome is defined as the cumulative measure of all environmental exposures and associated biological responses throughout an individual's lifespan, from conception to death [21] [22] [23]. This concept encompasses exposures from the environment, diet, behavior, and endogenous processes, serving as an environmental complement to the genome for understanding disease etiology. While genetic factors account for only approximately 10-50% of disease risk for most complex conditions, environmental factors contribute significantly to the remaining risk, with estimates suggesting over 70% of nonviolent deaths in the United States can be attributed to factors such as cigarette smoking, dietary imbalance, and air pollution [23] [24].

Biomonitoring serves as a critical tool for characterizing the internal exposome by measuring environmental chemicals, their metabolites, or reaction products in biological matrices. Traditional biomonitoring approaches typically employ targeted analyses to quantify specific, predefined chemicals in fluids like blood and urine. In contrast, exposomic biomonitoring aims to capture a broader spectrum of exposures through untargeted or semi-targeted methods, including all exposures of potential health significance whether from endogenous or exogenous sources [21] [22]. The advancement of microextraction techniques has become fundamental to exposomic research by enabling efficient, minimally invasive sampling and preparation of complex biological matrices for comprehensive analysis.

Microextraction Techniques in Exposome Research

Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME)

In vivo SPME represents a significant advancement for non-lethal monitoring of the exposome in living organisms. This technique involves the direct insertion of a fiber coated with a biocompatible extraction phase into tissues or biological fluids to extract both toxicants and endogenous metabolites without causing significant harm [25]. A key application demonstrated the non-lethal sampling of muscle tissue in sixty white suckers (Catastomus commersonii) from sites in the Athabasca River near oil sands development regions. The methodology enabled the extraction of a wide range of endogenous metabolites, primarily related to lipid metabolism, and the tentative identification of petroleum-related toxins [25].

The experimental protocol for in vivo SPME typically involves:

- Fiber Preparation: SPME fibers are coated with appropriate extraction phases (e.g., mixed-mode coatings for broad metabolite coverage) and conditioned according to manufacturer specifications.

- In vivo Sampling: Carefully inserting the fiber into the target tissue (e.g., fish muscle) for a predetermined equilibrium time (typically 30-60 minutes).

- Sample Desorption: Placing the fiber into a compatible solvent or directly coupling with LC-HRMS systems for analyte desorption and analysis.

- Metabolite Profiling: Using high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., LC-HRMS) to identify extracted compounds and multivariate statistical analysis to reveal significant changes in metabolic pathways in response to environmental toxicants [25].

Advanced Sampling and Preparation Methods

Solid-Phase Microextraction-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (SPME-GC/MS) has been innovatively applied in human biomonitoring studies, particularly for investigating health risks in contaminated sites. In one study, a semiconductor gas sensor array was trained using SPME-GC/MS to analyze human semen, blood, and urine samples from populations in contaminated sites in Italy [26]. The volatile organic compound (VOC) fingerprints obtained allowed researchers to discriminate between different contamination sources and predict chemical concentrations identified by GC/MS, providing a potentially rapid screening method for population studies [26].

For complex matrices like food, which represents a major exposure source, QuEChERSER (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe, Efficient, and Robust) has emerged as a "mega-method" that extends traditional QuEChERS approach. This method enables complementary determination of both LC- and GC-amenable compounds, significantly expanding analyte coverage. In one application, QuEChERSER facilitated the determination of 245 chemicals across 10 different food commodities, including both non-fatty and fatty products [27].