Accelerating Quantum Chemistry with Gaussian Process Surrogates: A Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate models and their transformative potential in quantum chemistry calculations.

Accelerating Quantum Chemistry with Gaussian Process Surrogates: A Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate models and their transformative potential in quantum chemistry calculations. It explores the foundational principles that make GPs ideal for capturing complex, non-linear relationships in chemical systems, detailing methodological steps for implementation, from data generation to model deployment. The content addresses key challenges like uncertainty quantification and active learning, and offers a rigorous framework for validating and benchmarking GP surrogates against traditional computational methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements to enable faster, more cost-effective, and uncertainty-aware discovery in computational chemistry and biomedicine.

What Are Gaussian Process Surrogates and Why Are They Ideal for Quantum Chemistry?

Computational quantum chemistry is indispensable for modern scientific discovery, enabling researchers to predict molecular properties, simulate chemical reactions, and design new materials and drugs. First-principles methods like density functional theory (DFT) provide high accuracy in modeling electronic structures but come with prohibitive computational costs that scale severely with system size [1]. This computational bottleneck restricts the scale and complexity of problems that can be practically studied, creating a critical barrier to progress in fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science [1] [2].

Surrogate models have emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, acting as fast, data-driven approximations to expensive quantum chemistry simulations. These models learn the relationship between molecular structure and quantum mechanical properties from existing computational data, enabling rapid predictions at a fraction of the computational cost. This article explores the implementation and application of Gaussian process surrogates and other machine learning interatomic potentials, providing detailed protocols and resources to help researchers overcome computational limitations in quantum chemistry simulations.

The Bottleneck Problem: Scale and Impact

Quantitative Dimensions of the Challenge

The computational expense of traditional quantum chemistry methods becomes evident when examining the resources required for typical research problems. The table below summarizes the scale of computational effort involved in various quantum chemistry applications.

Table 1: Computational Demands in Quantum Chemistry Applications

| Application Area | Representative System | Computational Method | Resource Requirements | Key Bottlenecks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Relaxations [1] | Small organic molecules (~10-50 atoms) | Density Functional Theory | ~300 million conformations across 3.5M trajectories | Energy/force calculations for non-equilibrium conformations |

| Reaction Barrier Calculation [3] | Surface diffusion/reactions | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) | 3-10x slower than surrogate-assisted | Hundreds/thousands of energy/force evaluations |

| Ice Photochemistry [2] | Defective ice structures | Quantum Mechanical Simulations | Advanced modeling impossible previously | Studying defects at sub-atomic scale requires extreme resources |

| Electronic Property Prediction [4] | Polyalkenes, acenes, polyenoic acids | Differentiable QM Workflows | Multiple property computations via Hamiltonian | Direct QM calculations for large molecular series |

Implications for Scientific Progress

These computational constraints have tangible consequences for research progress. In climate science, understanding how ice releases greenhouse gases when illuminated requires modeling complex defect interactions that has been "deceptively difficult to study" with conventional methods [2]. In drug discovery, the PubChemQCR dataset highlights the need for massive relaxation trajectory data (over 300 million molecular conformations) that would be infeasible with pure DFT approaches [1]. The emergence of predictive surrogates for quantum processors further underscores how even cutting-edge quantum hardware remains inaccessible for routine simulation, requiring classical emulation to broaden impact [5].

Gaussian Process Surrogates: Theory and Implementation

Gaussian Process Regression Fundamentals

Gaussian process regression (GPR) is a non-parametric Bayesian approach that has proven particularly valuable for quantum chemistry surrogates. GPR models a target function as a probability distribution over possible functions, providing not just predictions but also uncertainty quantification for each prediction [6]. This uncertainty estimate is crucial for determining when the surrogate model can be trusted and when the expensive underlying quantum chemistry calculation must be invoked.

The mathematical foundation of GPR begins with the assumption that any finite set of function evaluations follows a multivariate Gaussian distribution. For a training dataset ( D = {(xi, yi)}{i=1}^N ) with ( xi ) representing molecular descriptors and ( y_i ) the quantum chemical property of interest, the GP is completely specified by its mean function ( m(x) ) and covariance kernel ( k(x, x') ):

[ f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x, x')) ]

In practice, the squared exponential kernel is commonly used for its smoothness properties:

[ k(x, x') = \sigmaf^2 \exp\left(-\frac{\|x - x'\|^2}{2l^2}\right) + \sigman^2 \delta_{xx'} ]

where ( \sigmaf^2 ) is the signal variance, ( l ) is the length-scale parameter, and ( \sigman^2 ) is the noise variance.

GPR_calculator: An On-the-Fly Implementation

The GPR_calculator package implements these principles as a practical tool for quantum chemistry simulations [3]. This open-source package, built on Python and C++, integrates seamlessly with the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) and operates on an on-the-fly principle where the surrogate model is dynamically trained during simulations.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Surrogate Implementation

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR_calculator [3] | Python 3 & C++ (ASE-integrated) | On-the-fly surrogate for energy/force predictions | Uncertainty quantification, Adaptive training | NEB calculations, Molecular dynamics |

| PubChemQCR [1] | Dataset (Various formats) | Training/benchmarking ML interatomic potentials | 300M+ conformations with energy/force labels | MLIP development for organic molecules |

| PySCFAD [4] | Python (Differentiable) | Differentiable quantum chemistry workflow | Hamiltonian prediction, Multi-property learning | Electronic property prediction |

| Quantum GPR [7] | Quantum algorithms | Gaussian process regression using quantum kernels | Parameterized quantum circuits, Hardware-efficient | Bayesian optimization for chemistry |

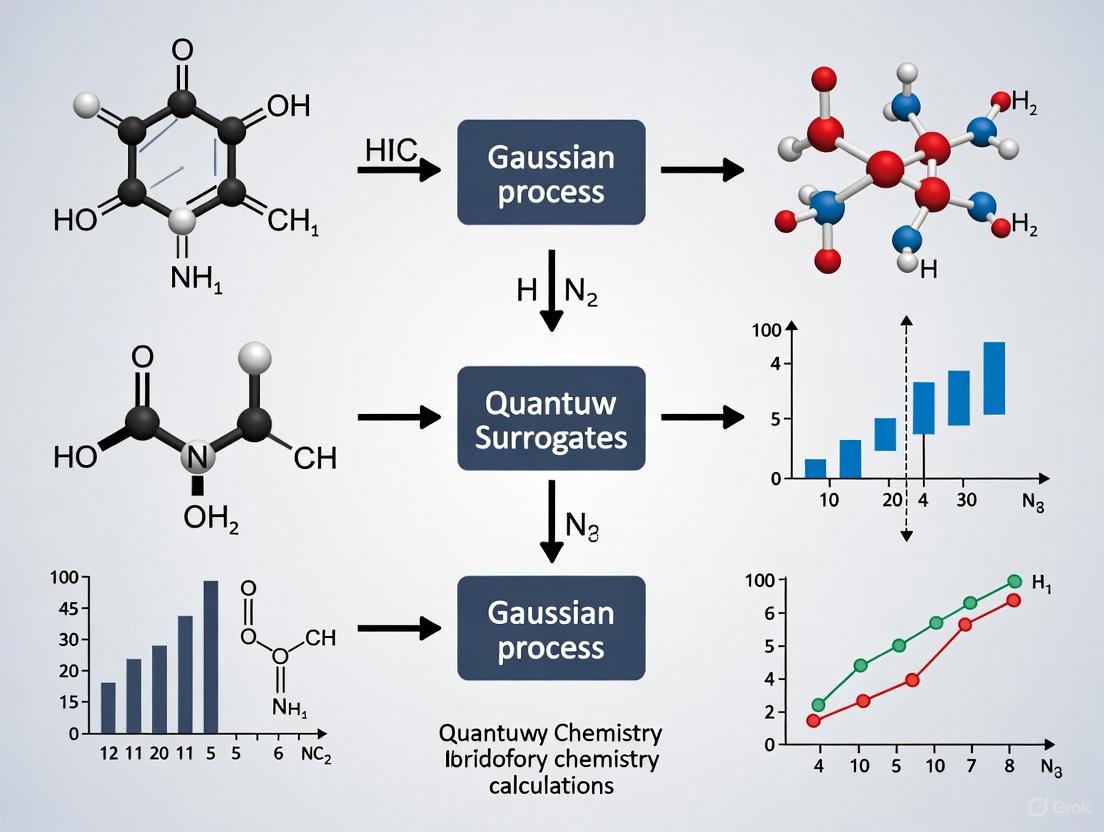

The following diagram illustrates the adaptive workflow used by GPR_calculator to minimize computational expense while maintaining accuracy:

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Nudged Elastic Band Calculations with GPR Surrogates

The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method is essential for locating transition states and calculating reaction barriers in chemical systems. This protocol details how to integrate GPR_calculator to accelerate these computations [3].

Materials and Software Requirements

- GPRcalculator package (https://github.com/MaterSim/GPRcalculator)

- Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)

- Base quantum chemistry calculator (e.g., GPAW, VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO)

- Initial and final state molecular configurations

Procedure

- System Setup

- Prepare the initial and final state configurations using ASE

- Generate the initial guess for the reaction path (typically 5-15 images)

- Configure the base DFT calculator with appropriate functional and basis set

GPR_calculator Configuration

- Initialize GPR_calculator with the base DFT calculator

- Set uncertainty threshold (typically 0.05-0.1 eV/Ã… for forces)

- Configure GPR kernel parameters (length scale, noise variance)

Adaptive NEB Execution

- For each NEB iteration:

- For each image in the band:

- GPR_calculator predicts energy and forces

- If uncertainty below threshold: use GPR predictions

- If uncertainty above threshold: invoke DFT calculation

- Update GPR model with new DFT data (if obtained)

- For each image in the band:

- Continue until NEB convergence criteria met (typically force < 0.05 eV/Ã…)

- For each NEB iteration:

Validation and Analysis

- Verify transition state with vibrational frequency analysis

- Compare reaction barrier with pure DFT calculation if feasible

- Document computational speedup (typically 3-10x acceleration [3])

Troubleshooting Notes

- If convergence issues occur: reduce uncertainty threshold to increase DFT calls

- If speedup is limited: increase uncertainty threshold or improve GPR training

- For complex reactions: ensure sufficient images in the elastic band

Protocol: Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials with PubChemQCR

This protocol outlines the development and benchmarking of ML interatomic potentials (MLIPs) using the PubChemQCR dataset, currently the largest publicly available collection of DFT-based relaxation trajectories for organic molecules [1].

Dataset Acquisition and Preparation

- Download PubChemQCR dataset (approximately 3.5 million trajectories)

- Preprocess molecular structures and partition into training/validation sets

- Extract energy and force labels at various theory levels

Model Training and Validation

- Select MLIP architecture (e.g., NequIP, MACE, SchNet)

- Train on energy and force labels using standardized splits

- Validate on both equilibrium and non-equilibrium geometries

- Benchmark against established baselines (9 representative models available)

Performance Metrics

- Force prediction accuracy (MAE, RMSE)

- Energy conservation in molecular dynamics

- Transferability to unseen molecular families

- Inference speed compared to direct DFT

Case Study: Quantum Surrogates for Electronic Structure

Beyond atomistic simulations, surrogate models can also approximate electronic structure computations. The following diagram illustrates a hybrid machine learning/quantum mechanics workflow for predicting multiple molecular properties from a surrogate Hamiltonian [4]:

This approach enables learning reduced-basis surrogate Hamiltonians that reproduce targets computed from much larger basis sets, significantly reducing computational expense while maintaining accuracy [4].

Performance Benchmarks and Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The effectiveness of surrogate models is quantified through both accuracy metrics and computational savings. The table below summarizes typical performance gains across different application domains.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks of Quantum Chemistry Surrogates

| Surrogate Method | Application Context | Accuracy Metrics | Speedup Factor | Uncertainty Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR_calculator [3] | NEB surface reactions | Forces within 0.05 eV/Ã… of DFT | 3-10x | Native via GPR variance |

| MLIPs (PubChemQCR) [1] | Molecular relaxations | Energy MAE < 1 kcal/mol | 100-1000x (inference) | Varies by architecture |

| Hybrid ML/QM [4] | Electronic properties | Multiple properties within 1-5% error | 10-100x | Via ensemble methods |

| QM Descriptor Prediction [8] | Low-data chemical tasks | Outperforms direct QM descriptors | 100x (descriptor prediction) | Hidden representations |

Strategic Selection: Descriptors vs. Hidden Representations

An important consideration in surrogate model design is whether to use predicted quantum mechanical descriptors as inputs to downstream models or leverage the hidden representations learned by the surrogate model. Recent research indicates that hidden representations often outperform explicit QM descriptors, except in very low-data regimes or when using carefully selected, task-specific descriptors [8]. This suggests that the internal states of surrogate models capture rich, transferable chemical information that may be more robust than pre-defined physical descriptors.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite their promising performance, current surrogate models face several limitations. Transferability remains challenging—models trained on specific molecular families often perform poorly on structurally distinct compounds [1]. Uncertainty quantification, while inherent in GPR approaches, requires careful calibration to prevent either excessive conservative behavior or overconfidence in predictions [6].

Future research directions include the development of quantum-enhanced GPR that uses quantum kernels to potentially improve performance [7], integration of surrogates with bootstrap embedding techniques to handle complex molecules [9], and creation of multi-fidelity models that leverage data from various levels of theory. The emergence of differentiable quantum chemistry workflows [4] also opens new possibilities for end-to-end learning of molecular representations.

As these methods mature, surrogate models are poised to dramatically expand the scope of quantum chemistry applications, enabling research on complex systems that were previously computationally prohibitive. By following the protocols and principles outlined in this article, researchers can begin integrating these powerful approaches into their computational workflows today.

Gaussian Processes (GPs) represent a powerful, non-parametric Bayesian approach for regression and classification, distinguished by their inherent capacity to quantify predictive uncertainty. Within quantum chemistry calculations, where ab initio computations are prohibitively expensive, GPs serve as efficient surrogate models, enabling the exploration of potential energy surfaces and molecular properties with principled uncertainty estimates. This application note delineates the core principles of Gaussian Process regression, detailing the mathematical foundations, operational mechanisms, and practical protocols for their implementation, with a specific focus on applications relevant to computational drug development.

Mathematical Foundations

From Distributions to Functions

A Gaussian Process extends the concept of a multivariate normal distribution to function spaces. While a multivariate normal distribution is defined over a finite-dimensional vector space, a GP defines a distribution over functions, where any finite collection of function values has a joint multivariate Gaussian distribution [10] [11]. Formally, a Gaussian Process is completely specified by its mean function ( m(\mathbf{x}) ) and covariance function ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') ), and is denoted as:

[ f(\mathbf{x}) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(\mathbf{x}), k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')) ]

For a set of inputs ( \mathbf{X} = {\mathbf{x}1, \mathbf{x}2, \dots, \mathbf{x}n} ), the corresponding function values ( \mathbf{f} = [f(\mathbf{x}1), f(\mathbf{x}2), \dots, f(\mathbf{x}n)]^\top ) follow a multivariate normal distribution:

[ \mathbf{f} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}, \mathbf{K}) ]

where ( \boldsymbol{\mu} = [m(\mathbf{x}1), m(\mathbf{x}2), \dots, m(\mathbf{x}n)]^\top ) is the mean vector, and ( \mathbf{K} ) is the ( n \times n ) covariance matrix with entries ( K{ij} = k(\mathbf{x}i, \mathbf{x}j) ) [10] [12]. This relationship establishes the foundation for performing Bayesian inference directly in the space of functions.

The Role of Kernels

The covariance function, or kernel, is the central component that dictates the properties of the functions drawn from a GP prior [11] [12]. It defines the similarity between two input points, determining the smoothness, periodicity, and scale of the function that the GP can model. The choice of kernel effectively encodes our prior assumptions about the underlying function we wish to learn.

Table 1: Common Kernel Functions and Their Properties

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form | Function Properties | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = a^2 \exp\left(-\frac{|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|^2}{2\ell^2}\right) ) | Infinitely differentiable, very smooth | Generic smooth functions, potential energy surfaces |

| Matérn | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \frac{2^{1-\nu}}{\Gamma(\nu)} \left( \frac{\sqrt{2\nu}|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|}{\ell} \right)^\nu K_\nu \left( \frac{\sqrt{2\nu}|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|}{\ell} \right) ) | ( \nu )-times differentiable, less smooth than RBF | Noisy physical phenomena, molecular dynamics |

| Periodic | ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = a^2 \exp\left(-\frac{2\sin^2(\pi|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'|/p)}{\ell^2}\right) ) | Periodic with period ( p ) | Crystalline materials, oscillatory systems |

The hyperparameters of a kernel (e.g., length-scale ( \ell ), amplitude ( a )) control the specific characteristics of the functions. For instance, a larger length-scale implies slower variation, resulting in smoother functions, while the amplitude controls the vertical scale of the function variation [12].

How Gaussian Processes Work

The Predictive Distribution

The core of GPR lies in deriving the predictive distribution for function values ( \mathbf{f}* ) at new test points ( \mathbf{X}* ), conditioned on the training data ( \mathcal{D} = { \mathbf{X}, \mathbf{y} } ). The joint distribution of observed targets ( \mathbf{y} ) and predicted function values ( \mathbf{f}_* ) is:

[ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{y} \ \mathbf{f}* \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N} \left( \mathbf{0}, \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigman^2\mathbf{I} & \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}*) \ \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) & \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_, \mathbf{X}_*) \end{bmatrix} \right) ]

where ( \sigman^2 ) is the noise variance accounting for noisy observations ( \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{f} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon} ), with ( \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigman^2) ) [13]. Conditioning on the training data yields the key predictive equations for the posterior GP:

[ \begin{aligned} \text{Mean: } & \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{f}*] = \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) \left[ \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigma_n^2\mathbf{I} \right]^{-1} \mathbf{y} \ \text{Covariance: } & \operatorname{Cov}(\mathbf{f}_) = \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}*, \mathbf{X}) - \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}_, \mathbf{X}) \left[ \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigman^2\mathbf{I} \right]^{-1} \mathbf{K}(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}*) \end{aligned} ]

The mean prediction is a linear combination of the training outputs, weighted by the kernel-based similarity between test and training points. The covariance formula shows that the predictive uncertainty is the prior uncertainty minus the information gained from the training data [10] [12].

Quantifying Uncertainty

GPs provide a natural framework for uncertainty quantification. The predictive covariance captures the epistemic uncertainty (or model uncertainty) arising from a lack of data. This uncertainty is reducible – as more data is observed, the posterior uncertainty decreases, particularly in regions densely populated with training points [13] [12].

Table 2: Types of Uncertainty in Gaussian Process Models

| Uncertainty Type | Source | Representation in GP | Reducible? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epistemic (Model) | Lack of knowledge about the true function | Predictive variance ( \operatorname{Cov}(\mathbf{f}_*) ) | Yes |

| Aleatoric (Data) | Inherent noise in observations | Likelihood noise parameter ( \sigma_n^2 ) | No |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of Gaussian Process regression, from prior to posterior, highlighting how uncertainty is updated conditioned on data.

The visual interpretation of uncertainty is a hallmark of GPs. In regions with no training data, the confidence interval (often plotted as ±2 standard deviations) is wide, reflecting high uncertainty. As the model encounters data points, the confidence band narrows, indicating increased confidence in the predictions [11] [12]. The diagram below conceptualizes this relationship between data density and predictive uncertainty.

Experimental Protocols for Quantum Chemistry

Protocol: Building a GP Surrogate for a Potential Energy Surface (PES)

Objective: To create a computationally efficient GP surrogate model for a high-fidelity quantum chemistry PES calculation.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: For initial quantum chemistry calculations.

- Quantum Chemistry Software: e.g., Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, for reference calculations.

- Programming Environment: Python with libraries such as GPyTorch [14], scikit-learn [14], or NumPy.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GP Surrogate Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Data Generator | Produces high-fidelity training data. | DFT (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*), CCSD(T) calculations. |

| Descriptor Calculator | Transforms molecular structure into a model-ready input vector. | Internal coordinates (distances, angles), Coulomb matrices, SOAP descriptors. |

| GP Software Framework | Provides core GP functionality, hyperparameter optimization, and prediction. | GPyTorch (scalable GPs) [14], scikit-learn (standard GPs). |

| Hyperparameter Optimizer | Automates the maximization of the marginal likelihood. | L-BFGS-B optimizer, Adam (for stochastic variational GPs). |

Procedure:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Select representative molecular geometries (configurations) for which reference energies will be computed. Use sampling methods like Latin Hypercube Sampling or trajectory-driven sampling to ensure good coverage of the relevant configuration space.

- Reference Calculation: Execute high-level quantum chemistry calculations at each selected geometry to obtain the target potential energy. Record energies and, if available, atomic forces.

- Feature Engineering: Convert each molecular geometry into a suitable input vector (descriptor) for the GP. For PES, this could be a vector of internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals) or a more advanced descriptor like the Coulomb matrix.

- Model Training:

- Initialize GP: Define a mean function (often zero) and a kernel (e.g., a composite RBF kernel on each internal coordinate).

- Optimize Hyperparameters: Maximize the log marginal likelihood with respect to the kernel parameters (length-scales, amplitude) and the noise variance. The log marginal likelihood is given by [13]: [ \log p(\mathbf{y} | \mathbf{X}) = -\frac{1}{2} \mathbf{y}^\top (\mathbf{K} + \sigman^2\mathbf{I})^{-1} \mathbf{y} - \frac{1}{2} \log |\mathbf{K} + \sigman^2\mathbf{I}| - \frac{n}{2} \log 2\pi ]

- Model Validation: Predict energies for a held-out test set of geometries not used in training. Evaluate performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and assess the calibration of uncertainty estimates (e.g., check if ~95% of test points lie within the 95% credible interval).

- Deployment: Use the trained GP surrogate for tasks such as molecular dynamics simulations or geometry optimizations, leveraging its fast predictions and uncertainty estimates to guide the sampling process.

Addressing Computational Complexity

A primary limitation of exact GPR is its ( O(n^3) ) computational complexity due to the inversion of the ( n \times n ) covariance matrix [14] [13]. For large-scale quantum chemistry problems, this becomes prohibitive. Several scalable approximations are available:

- Sparse Gaussian Processes: These methods use a small set of ( m ) inducing points to summarize the dataset, reducing complexity to ( O(nm^2) ) [13].

- Deep Kernel Learning (DKL): Combines a deep neural network for feature extraction with a GP on top. The network learns transformative representations that are more amenable to modeling with a standard kernel [13].

- Stochastic Variational Inference: A state-of-the-art approach for scaling GPs to massive datasets, often implemented in libraries like GPyTorch [14].

Gaussian Processes offer a principled, probabilistic framework for regression that is particularly well-suited for applications in quantum chemistry. Their ability to provide predictions with inherent, quantifiable uncertainty makes them ideal surrogate models for expensive ab initio calculations. By understanding the core principles—the foundational multivariate Gaussian distribution, the critical role of the kernel, and the Bayesian conditioning mechanism—researchers can effectively deploy GPs to accelerate computational drug discovery and materials design. The ongoing development of scalable GP approximations ensures their continued relevance and applicability to the increasingly complex problems faced in modern scientific research.

In the field of computational chemistry and materials science, the high computational cost of accurate quantum chemistry calculations, such as those based on density functional theory (DFT), presents a significant bottleneck for high-throughput screening and the exploration of complex molecular systems [15] [16]. Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate models have emerged as a powerful machine learning strategy to overcome this barrier. These models approximate expensive-to-evaluate quantum chemistry functions, enabling rapid property prediction and efficient navigation of chemical space. Their adoption is primarily driven by two inherent advantages: non-parametric flexibility, which allows them to adapt to complex, multi-dimensional energy surfaces without a pre-defined functional form, and the provision of built-in error bars, which offer a quantifiable measure of prediction uncertainty. This application note details these advantages within the context of quantum chemistry research, providing structured data, experimental protocols, and visualizations to guide their implementation.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Performance

Core Advantages of Gaussian Process Surrogates

The utility of GP models in computational chemistry stems from their foundational statistical architecture, which provides distinct benefits over other surrogate modeling techniques.

- Non-Parametric Flexibility: Unlike parametric models that are constrained to a specific functional form, GPs are data-driven. They define a distribution over functions and update this distribution based on observed data, allowing them to learn the complex shape of a potential energy surface or a structure-property relationship directly from computational experiments [17]. This makes them exceptionally suitable for modeling the intricate, high-dimensional landscapes common in molecular simulations without prior knowledge of the underlying physical equations.

- Built-in Error Bars: A GP model not only provides a mean prediction for a given molecular structure but also a variance estimate, which serves as a built-in error bar [18] [19]. This uncertainty quantification is crucial for assessing the reliability of predictions. In the context of high-throughput screening, it helps identify when a prediction is an extrapolation and may be unreliable [15]. Furthermore, this feature is the cornerstone of active learning and Bayesian optimization, as it allows algorithms to strategically select the next most informative calculations by balancing exploration (sampling high-uncertainty regions) and exploitation (sampling regions predicted to be high-performing) [16] [19].

Quantitative Performance in Chemical Research

Recent studies have demonstrated the significant efficiency gains achieved by employing GP surrogates in various chemical research applications. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from the literature.

Table 1: Performance of Gaussian Process Surrogates in Chemical Research Applications

| Application Area | Comparison Method | Key Performance Metric | Result with GP Surrogate | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saddle Point Search (Molecular Reactions) | Standard Dimer Method | Reduction in Electronic Structure Calculations | Order of magnitude reduction [20] | |

| Saddle Point Search (Molecular Reactions) | Sella (Internal Coordinates) | Number of Electronic Structure Calculations | Similar performance using simpler Cartesian coordinates [20] | |

| Organic Molecule Discovery (OPVs) | Random Search | Discovery Efficiency of Promising Molecules | Identified 1000x more promising molecules [16] | |

| DFT Lattice Parameter Prediction | — | Mean Absolute Relative Error (MARE) | ~0.8-1.0% (with PBEsol/vdW-DF-C09) [15] | |

| Structural Response Estimation | Full Physics Simulation | Computational Cost | Comparable results at a fraction of the cost [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines a generalized workflow for deploying a GP surrogate to accelerate a typical computational chemistry task, such as a saddle point search or molecular property optimization.

Protocol 1: GP-Accelerated Saddle Point Search

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a GP surrogate model accelerating a quantum chemistry-driven saddle point search, such as the GPR-dimer method [20].

Workflow for GP-accelerated saddle point search

Procedure:

- Initialization: Begin with an initial atomic configuration, typically near a local energy minimum. Select a small number of initial configurations to seed the GP model and perform full quantum chemistry calculations on them [20].

- Quantum Chemistry Calculation: Execute a high-fidelity electronic structure calculation (e.g., DFT, Hartree-Fock) at the current geometry. Record the total energy and atomic forces [20].

- GP Model Update: Use the newly computed energy and force data to update (train) the Gaussian Process surrogate model. The model learns a mapping from atomic coordinates to the energy and forces [20] [19].

- Surrogate Prediction: The updated GP model now provides a fast approximation of the energy surface, including predictive mean and variance (uncertainty) for any proposed atomic configuration.

- Dimer Method Step: Using the surrogate model's predictions, perform multiple iterations of the minimum-mode following dimer method. This involves:

- Estimating the Lowest Eigenmode: Use the dimer (two nearby images of the system) to approximate the eigenvector corresponding to the lowest eigenvalue of the Hessian without explicitly constructing it [20].

- Updating the Geometry: Invert the force component along the minimum mode to guide the search uphill towards the saddle point, while minimizing forces in orthogonal directions. These steps are performed cheaply using the GP surrogate.

- Convergence Check: After the dimer method has progressed to a new geometry using the surrogate, check for convergence to a saddle point (vanishing forces, one negative Hessian eigenvalue). If converged, the protocol ends.

- Iteration: If not converged, return to Step 2 with the new geometry for another, infrequent, quantum chemistry calculation. This validates the surrogate's predictions and provides new, high-fidelity data to improve the model in the relevant region of the energy landscape [20].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Optimization for Molecular Discovery

This protocol describes how to use a GP surrogate within a Bayesian optimization (BO) framework to discover molecules with optimal properties, such as for organic photovoltaics [16].

Procedure:

- Define Chemical Space: Establish the search space using a library of molecular building blocks and the rules for connecting them (e.g., to form oligomers of a specific size) [16].

- Establish Evaluation Function: Define the target property to optimize (e.g., excited state energy, ionization potential). This function is computationally expensive, typically requiring quantum chemistry methods [16].

- Select Initial Population: Randomly select a small set of candidate molecules from the defined chemical space to form the initial training data.

- Evaluate Initial Candidates: For each candidate in the initial set, construct the molecule and compute its target property using the expensive evaluation function (e.g., DFT/TD-DFT calculations).

- Build GP Surrogate: Train a GP model on the accumulated data, mapping the molecular representation (e.g., fingerprint, descriptor) to the target property. The GP provides a posterior distribution over the entire chemical space.

- Suggest New Candidate(s): Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which leverages the GP's mean and uncertainty predictions, to propose the next most promising molecule(s) to evaluate. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting areas predicted to be high-performing [16] [19].

- Evaluate and Update: Compute the property of the newly suggested candidate using the expensive evaluation function. Add this new data point to the training set.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 5-7 until a computational budget is exhausted or a satisfactory molecule is found [16].

Uncertainty Quantification and Validation

The built-in error bars from a GP model are only useful if they are accurate and well-calibrated. Proper validation is essential.

Key Metrics for Validation

- Error-Based Calibration: This is considered a superior method for validating UQ [18]. It involves binning predictions by their predicted uncertainty and plotting the actual root-mean-square error (RMSE) against the mean predicted uncertainty for each bin. A well-calibrated model will have these values align closely with the line y=x.

- Spearman's Rank Correlation: This metric assesses whether higher predicted uncertainties correlate with larger absolute errors. A positive correlation is desired, but this metric can be sensitive to test set design and should not be used alone [18].

- Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL): NLL evaluates the model's probability density function by penalizing both inaccuracy and high uncertainty. Lower values indicate better performance, though it can be misleading if not interpreted alongside calibration plots [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and software components required for implementing the protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Components

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Workflow | Example Implementations / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | Provides high-fidelity training data (energy, forces) for the surrogate model. | Software such as Gaussian, ORCA, VASP, or CP2K. |

| GP Regression Software | Core engine for building and updating the surrogate model. | scikit-learn (Python), GPy (Python), GPflow (Python). |

| Optimization Algorithm | Navigates the surrogate surface to find minima, saddle points, or optima. | Dimer method, L-BFGS, Differential Evolution [19]. |

| Molecular Builder | Constructs molecular geometries from building blocks for discovery tasks. | stk software package [16]. |

| Acquisition Function | Guides Bayesian optimization by balancing exploration and exploitation. | Expected Improvement (EI), Constrained EI (CEI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [16] [19]. |

| Descriptor / Fingerprint | Represents a molecular structure as a numerical vector for the GP model. | ECFP fingerprints, Mordred descriptors, SOAP descriptors [16]. |

| Ro 41-0960 | Ro 41-0960, CAS:125628-97-9, MF:C13H8FNO5, MW:277.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SF1670 | SF1670, CAS:345630-40-2, MF:C19H17NO3, MW:307.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Uncertainty-Based Selection

The power of built-in error bars is most evident in active learning cycles. The following diagram illustrates how prediction uncertainty guides the selection of subsequent calculations.

Uncertainty-guided selection in active learning

This schematic shows a GP model's prediction for a target property across a molecular descriptor space. The solid line is the mean prediction, and the shaded region represents the uncertainty. An existing data point is shown in green. The next molecule selected for expensive calculation is the one with the highest uncertainty (yellow star), as acquiring its data will most effectively reduce the model's overall uncertainty in that region [16] [18]. This process ensures computational resources are used most efficiently to globalize the model or refine it near critical points like saddle points or optima.

Gaussian Process (GP) regression is a powerful, non-parametric Bayesian approach for surrogate modeling, becoming an invaluable tool in computational science and engineering. Its ability to provide predictions with quantifiable uncertainty is particularly appealing for applications where computational expense is high and data points are scarce, such as in quantum chemistry calculations and material property prediction [21] [20]. By placing a prior distribution over functions and updating it with observed data to form a posterior distribution, GP regression offers a flexible framework for approximating complex input-output relationships. This article details the core workflow, from data conditioning to prediction, and provides specific protocols for its application in accelerating quantum chemistry research, drawing on recent advances in the field.

Core Principles of Gaussian Process Regression

A Gaussian Process is a collection of random variables, any finite number of which have a joint Gaussian distribution [14]. It is completely specified by its mean function, ( m(\mathbf{x}) ), and its covariance function, ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') ), and defines a distribution over functions ( f(\mathbf{x}) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(\mathbf{x}), k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')) ) [22]. For practical regression, we assume we observe a training dataset ( \mathcal{D} = {(\mathbf{x}i, yi)}{i=1}^{N} ), where ( yi = f(\mathbf{x}i) + \epsilon ) and ( \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigman^2) ) is an independent noise term.

The choice of the kernel function ( k(\cdot, \cdot) ) is critical as it encodes prior assumptions about the function's properties, such as smoothness and periodicity. A common choice is the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, ( k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}') = \sigma^2 \exp\left(-\tfrac{1}{2\ell^2}\|\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}'\|^2\right) ), where ( \sigma^2 ) is the signal variance and ( \ell ) is the characteristic length-scale [14]. The hyperparameters of the kernel, collectively denoted ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ), are typically learned from the data by maximizing the log marginal likelihood, a process that automatically incorporates Occam's Razor by balancing data fit with model complexity [21] [14].

The Gaussian Process Prediction Workflow

The fundamental goal in GP regression is to make predictions for the function values ( \mathbf{f}* ) at new, test input locations ( \mathbf{X}* ). The GP framework provides the full predictive distribution, not just a point estimate.

The Predictive Equations

Given a training set ( (\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{y}) ) and a kernel with optimized hyperparameters, the joint prior distribution of the observed outputs ( \mathbf{y} ) and the predicted function values ( \mathbf{f}* ) is [23]: $$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{y} \ \mathbf{f}* \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N} \left( \mathbf{0}, \begin{bmatrix} K(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigman^2\mathbf{I} & K(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) \ K(\mathbf{X}_, \mathbf{X}) & K(\mathbf{X}*, \mathbf{X}*) \end{bmatrix} \right) $$

By conditioning on the observed training data, we obtain the key predictive distribution for a single test point ( \mathbf{x}* ) [14] [23]: $$ p(f* | \mathbf{x}*, \mathcal{D}) = \mathcal{N}(\mu(\mathbf{x}), \sigma^2(\mathbf{x}_)) $$ where the predictive mean and variance are: $$ \mu(\mathbf{x}*) = K(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{X})[K(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigma_n^2\mathbf{I}]^{-1}\mathbf{y} $$ $$ \sigma^2(\mathbf{x}_) = K(\mathbf{x}*, \mathbf{x}) - K(\mathbf{x}_, \mathbf{X})[K(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{X}) + \sigman^2\mathbf{I}]^{-1}K(\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{x}*) $$

The predictive mean ( \mu(\mathbf{x}*) ) serves as the best point estimate, while the predictive variance ( \sigma^2(\mathbf{x}*) ) quantifies the model's uncertainty at that input location. This uncertainty naturally increases as one moves away from the observed data points [14].

Workflow Diagram and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow from data and prior specification to the final predictive distribution, highlighting the key computational steps.

Application in Quantum Chemistry and Material Science

GP surrogate models are particularly effective in quantum chemistry, where they can dramatically reduce the number of expensive electronic structure calculations needed for tasks like transition state searching and property prediction.

Accelerating Saddle Point Searches

A prime application is in locating first-order saddle points on high-dimensional potential energy surfaces, which is essential for modeling chemical reaction mechanisms and rates using transition state theory [20]. Goswami et al. demonstrated an efficient implementation of GP regression to accelerate the minimum mode following (dimer) method. In this GPR-dimer approach, a surrogate energy surface is constructed and updated after each electronic structure calculation. This method was applied to a test set of 500 molecular reactions, achieving an order of magnitude reduction in the number of electronic structure calculations required to converge to saddle points compared to the standard dimer method [20]. This performance was on par with an elaborate internal coordinate method (Sella), despite using simpler Cartesian coordinates, showcasing the power of GPR to handle systems with a wide range of stiffness in molecular degrees of freedom [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Saddle Point Search Methods on 500 Molecular Reactions [20]

| Method | Key Features | Relative Number of Electronic Structure Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Dimer Method | Uses Cartesian coordinates; no surrogate model | Baseline (~10x more than GPR-dimer) |

| Sella | Uses automated non-redundant internal coordinates | Similar to GPR-dimer |

| GPR-Dimer (This work) | Cartesian coordinates with GPR surrogate model | ~10x reduction vs. standard dimer |

Predicting Material Properties

Sigma profiles, which are histograms of the surface charge distributions of solvated molecules, are physically significant, low-dimensional descriptors suitable for predicting thermophysical material properties [24]. Salih et al. developed OpenSPGen, an open-source tool for generating sigma profiles, and used a Gaussian process as a simple surrogate model to predict material properties based on these profiles [24]. Their study concluded that a higher level of quantum chemical theory does not necessarily translate to more accurate predictions, providing an important guideline for the efficient use of computational resources.

Furthermore, the concept of common workflow interfaces, as demonstrated by the common relax workflow implemented for eleven quantum engines (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, CASTEP), enables robust and reproducible computation of material properties like equations of state [25]. These workflows abstract away code-specific complexities, allowing non-experts to leverage the implementer's expertise and use GP and other models for reliable property prediction and cross-verification [25].

Experimental Protocol: GPR for Quantum Chemistry Surrogates

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a GP surrogate model to accelerate a quantum chemistry task, such as a saddle point search or a property scan.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Components for GP Surrogate Modeling in Quantum Chemistry

| Component / Software | Function / Description | Relevance to Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Engine(e.g., CP2K, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs the underlying electronic structure calculations (DFT, HF) to compute energies and atomic forces. | Generates the high-fidelity training data (inputs: atomic coordinates; outputs: energy/forces) for the surrogate. |

| GP Software Library(e.g., GPyTorch, scikit-learn) | Provides implementations for kernel functions, hyperparameter optimization, and predictive inference. | Core engine for building and updating the surrogate model from quantum chemistry data. |

| Optimization Algorithm(e.g., L-BFGS, Adam) | Finds the hyperparameters that maximize the log marginal likelihood of the GP. | Used in the hyperparameter optimization step of the workflow. |

| Kernel Function(e.g., RBF, Matérn) | Defines the covariance structure of the GP, encoding assumptions about the smoothness of the potential energy surface. | Critical for model performance; choice impacts the quality of predictions and uncertainty estimates. |

| SPC 839 | SPC 839, CAS:219773-55-4, MF:C18H14N4O3S, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SSR504734 | SSR504734, CAS:742693-38-5, MF:C20H20ClF3N2O, MW:396.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Problem Setup and Initial Sampling:

- Define the domain of interest in the chemical space (e.g., a range of molecular geometries or reaction coordinates).

- Select an initial sampling strategy (e.g., random sampling, Latin Hypercube) to select a small set of input configurations ( \mathbf{X}_{\text{init}} ) for the first quantum chemistry calculations. This provides the initial training dataset ( \mathcal{D} ).

GP Prior and Kernel Selection:

- Define a prior mean function. A zero-mean function is often used for simplicity, assuming the data is normalized.

- Choose a kernel function. The Matérn kernel (e.g., Matérn 5/2) is a robust default for modeling potential energy surfaces, as it does not assume excessive smoothness [20]. The RBF kernel is another common choice.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization:

- Using the initial dataset ( \mathcal{D} ), optimize the GP hyperparameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ) (e.g., length-scales, output scale, noise variance). This is typically done by maximizing the log marginal likelihood using a gradient-based optimizer [14] [21]: $$ \log p(\mathbf{y} | \mathbf{X}, \boldsymbol{\theta}) = -\frac{1}{2} \mathbf{y}^{\top} (K{\boldsymbol{\theta}} + \sigman^2 I)^{-1} \mathbf{y} - \frac{1}{2} \log |K{\boldsymbol{\theta}} + \sigman^2 I| - \frac{n}{2} \log 2\pi $$

Active Learning and Sequential Design:

- Use the trained GP to select the next evaluation point ( \mathbf{x}_{\text{next}} ). Instead of random sampling, an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound) that leverages the GP's predictive uncertainty can be used to choose the most "informative" point [21]. In saddle point searches, the search direction is guided by the minimum mode of the Hessian, and the GP surrogate is updated at each step [20].

- Run the quantum chemistry calculation at ( \mathbf{x}{\text{next}} ) to obtain the true output ( y{\text{next}} ).

- Augment the training data: ( \mathcal{D} \leftarrow \mathcal{D} \cup {(\mathbf{x}{\text{next}}, y{\text{next}})} ).

Model Update and Prediction:

- Update the GP posterior by re-conditioning on the augmented dataset. In practice, this may involve retraining the hyperparameters or using sequential update formulas.

- Make predictions for any test point ( \mathbf{x}_* ) using the predictive equations (Section 3.1). The process from steps 4-5 is repeated until convergence (e.g., saddle point forces are below a threshold, or the property of interest is determined with sufficient certainty).

Workflow for an Adaptive Saddle Point Search

The GPR-dimer method integrates the GP surrogate directly into the optimization loop, as shown in the following workflow.

The Gaussian Process workflow provides a rigorous probabilistic framework for building surrogate models that are both predictive and self-diagnostic of their uncertainty. As demonstrated in quantum chemistry, integrating GPR with electronic structure calculations can lead to dramatic efficiency gains, such as reducing the number of required energy and force evaluations by an order of magnitude in saddle point searches. The key to success lies in the careful choice of the kernel, robust hyperparameter estimation, and an active learning strategy that intelligently selects new data points. By following the protocols outlined herein, researchers can effectively deploy GP surrogates to accelerate costly computational experiments, from mapping reaction pathways to screening material properties, thereby enhancing the scope and reliability of computational discovery.

Implementing GP Surrogates: A Step-by-Step Guide for Chemical Workflows

In the realm of quantum chemistry-driven drug discovery and materials science, Gaussian process (GP) surrogates have emerged as powerful tools for accelerating the prediction of molecular properties while quantifying uncertainty. The performance of these surrogates critically depends on the careful selection and preprocessing of quantum chemical descriptors—numerical representations that encode chemical information from molecular structures. These descriptors transform molecular entities into a structured input space where meaningful patterns can be learned by machine learning algorithms. Molecular descriptors are defined as the final result of a logical and mathematical procedure that transforms chemical information encoded within a symbolic representation of a molecule into a useful number [26].

The fundamental challenge in constructing effective GP surrogates lies in the fact that quantum chemical calculations, while accurate, are computationally prohibitive for large-scale screening. For instance, coupled cluster (CC) methods like CCSD(T)—considered the "gold standard" of quantum-chemical prediction—suffer from a steep (O(N^7)) scaling where (N) is the number of electrons [27]. By leveraging carefully chosen descriptors, GP surrogates can achieve target accuracy with a dramatic reduction in data generation cost, often by over an order of magnitude [27]. However, this requires a systematic approach to descriptor management that balances computational efficiency with chemical relevance—a balance we explore in this application note through structured protocols and practical implementations for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Taxonomy of Quantum Chemical Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be systematically classified based on the type of molecular representation they derive from and their invariance properties. A robust descriptor should be invariant to molecular manipulations that don't alter intrinsic molecular structure, including atom numbering, spatial reference frame, and molecular conformations [26].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors with Examples and Applications

| Descriptor Class | Description | Examples | Key Applications | Invariance Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0D (Constitutional) | Derived from molecular formula without structural information | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts | Initial screening, simple QSAR | Atom labeling, rotation, translation |

| 1D (Topological) | Based on 2D molecular structure and connectivity | Structural fragments, molecular fingerprints | Similarity searching, virtual screening | Atom labeling, rotation, translation |

| 2D (Geometrical) | Derived from 3D molecular structure | WHIM descriptors, GETAWAY descriptors, 3D-MoRSE | Protein-ligand docking, conformation-dependent properties | Atom labeling only |

| 3D (Quantum Chemical) | From electronic structure calculations | Partial charges, HOMO/LUMO energies, dipole moments, Fukui functions | Reactivity prediction, reaction mechanism analysis | Atom labeling only (conformation-dependent) |

| 4D (Interaction Fields) | Based on molecular interaction potentials | GRID, CoMFA descriptors | Binding affinity prediction, pharmacophore modeling | Dependent on alignment procedure |

Quantum chemical descriptors specifically encompass electronic properties calculated through quantum mechanical methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) or Hartree-Fock (HF). DFT focuses on electron density (\rho(r)) and calculates properties through the Kohn-Sham equations, while HF approximates the many-electron wave function as a single Slater determinant [28]. These descriptors provide critical insights into reactivity, binding affinities, and reaction mechanisms that are inaccessible through classical methods.

For DNA reaction prediction, researchers have developed specialized descriptor matrices incorporating stacking terms, dangling terms, looping terms, and initiating terms, with features including identifier numbers, energy values from quantum chemical calculations, and entropy values derived from physically motivated statistical models [29]. This demonstrates how domain-specific knowledge can inform descriptor design for particular applications.

Preprocessing Methodologies for Enhanced Predictive Performance

Raw quantum chemical descriptors often require careful preprocessing to optimize their utility in Gaussian process surrogates. Feature selection plays a crucial role in improving the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning algorithms by identifying relevant features that significantly influence the target response [30].

Feature Selection Techniques

Comparative analyses of preprocessing methods for molecular descriptors reveal distinct performance characteristics across techniques:

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for Molecular Descriptors

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filtering Methods | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Ranks features by importance and recursively eliminates weakest | Computationally efficient, model-agnostic | May ignore feature dependencies | Good for initial feature reduction |

| Wrapper Methods | Forward Selection (FS), Backward Elimination (BE), Stepwise Selection (SS) | Uses model performance to guide feature selection | Considers feature interactions, finds optimized subsets | Computationally intensive, risk of overfitting | FS, BE, and SS coupled with nonlinear regression exhibit promising R-squared scores [30] |

| Embedded Methods | Regularization (L1, L2), Tree-based importance | Feature selection incorporated into model training | Balanced approach, model-specific | Tied to specific algorithm | Effective for high-dimensional descriptor spaces |

Data Scaling and Transformation Protocols

Beyond feature selection, additional preprocessing steps enhance descriptor quality:

Descriptor Repurposing: Existing datasets of quantum chemical properties can be repurposed to build data-efficient downstream machine learning models. For hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions, researchers successfully identified key valence bond descriptors and used publicly available datasets of pre-computed quantum chemical properties of organic radicals to build surrogate models [31].

Gram Matrix Regularization: For quantum Gaussian process regression, careful regularization of the Gram matrix is essential to preserve variance information, which is critical when the surrogate model is used for Bayesian optimization [7].

Multitask Learning: The multitask framework accommodates wider training set structures by leveraging both expensive (e.g., CC) and cheap (e.g., DFT) data sources, effectively reducing data generation costs by opportunistically exploiting existing data sources [27].

Diagram 1: Descriptor Preprocessing Workflow. This workflow outlines the sequential steps for transforming raw quantum chemical descriptors into optimized inputs for Gaussian process surrogates.

Experimental Protocol: Building Gaussian Process Surrogates with Preprocessed Descriptors

Protocol 1: Multitask Gaussian Process Regression for Molecular Property Prediction

Purpose: To leverage heterogeneous quantum chemical data sources for predicting molecular properties at high fidelity levels (e.g., CCSD(T)) with reduced computational cost.

Materials and Software:

- Quantum chemistry packages (Gaussian, Qiskit, AmberTools) -Descriptor calculation software (alvaDesc, Mordred, RDKit)

- GP regression library (GPyTorch, scikit-learn)

- Dataset: Primary level (CCSD(T)) and secondary level (DFT with various functionals) data

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Assemble training sets from coupled-cluster (CC) and density functional theory (DFT) data. Include DFT data generated by a heterogeneous mix of exchange-correlation functionals without imposing artificial hierarchy on functional accuracy [27].

Descriptor Calculation:

- For each molecule, compute 3D quantum chemical descriptors including HOMO/LUMO energies, partial charges, dipole moments, and Fukui functions.

- Apply invariance checks to ensure descriptor values are independent of molecular orientation or atom numbering.

Descriptor Preprocessing:

- Apply Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify the most relevant descriptors for the target property.

- Use Stepwise Selection (SS) with a nonlinear regression model to further refine the descriptor set.

- Standardize selected descriptors to zero mean and unit variance.

Model Training:

- Implement multitask Gaussian process regression with a coregionalization kernel to capture relationships between different fidelity levels.

- Configure the GP to preserve variance information through careful regularization of the Gram matrix [7].

- Train using a combined loss function that incorporates data from all fidelity levels.

Validation:

- Assess performance on a hold-out test set containing only primary level (CCSD(T)) predictions.

- Compare against single-fidelity models and Δ-learning approaches to quantify improvement.

Expected Outcomes: The multitask GP surrogate should predict at CC level accuracy with a reduction to data generation cost by over an order of magnitude [27]. The model should effectively leverage cheaper DFT calculations to enhance predictions without requiring strict alignment between different data sources.

Protocol 2: Quantum Gaussian Process Regression for Bayesian Optimization

Purpose: To implement a quantum Gaussian process regression approach using quantum kernels based on parameterized quantum circuits for Bayesian optimization of molecular structures.

Materials and Software:

- Quantum simulation environment (Qiskit, PennyLane)

- Hardware-efficient feature map implementation

- Bayesian optimization framework (BoTorch, Ax)

- Dataset: Molecular descriptors and target properties

Procedure:

- Quantum Kernel Design:

- Implement a hardware-efficient feature map using parameterized quantum circuits.

- Construct quantum kernels based on the feature map for Gaussian process regression.

Descriptor Preparation:

- Calculate electronic structure descriptors including molecular orbital energies, electron densities, and correlation energies.

- Apply forward selection (FS) to identify descriptors most relevant to the optimization target.

- Normalize descriptors to ensure compatibility with quantum feature maps.

Model Integration:

- Employ the quantum kernels within the Gaussian process regression framework.

- Apply careful regularization of the Gram matrix to preserve variance information [7].

- Configure the GP as a surrogate model for Bayesian optimization.

Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Use the quantum GP surrogate to suggest new molecular structures for evaluation.

- Update the GP model with new data points acquired through the optimization process.

- Iterate until convergence to optimal molecular configuration.

Validation:

- Apply the quantum Bayesian optimization algorithm to hyperparameter optimization of a machine learning model performing regression on a real-world dataset.

- Benchmark against classical Bayesian optimization to verify matching performance [7].

Expected Outcomes: The quantum Gaussian process should preserve variance information critical for Bayesian optimization and match the performance of classical counterparts while demonstrating potential for quantum advantage on suitable hardware.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Chemical Descriptor Management

| Tool Name | Type | Key Functionality | Descriptor Coverage | License | Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alvaDesc | Desktop Application | Calculates and analyzes molecular descriptors and fingerprints | 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors | Proprietary, commercial | GUI, CLI, KNIME, Python [26] |

| Mordred | Python Library | Computes molecular descriptors from RDKit molecules | 0D, 2D, 3D descriptors | Free open source | Python only [26] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Fundamental cheminformatics operations and descriptor calculation | 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors | Free open source | Python, C++ [26] |

| scikit-fingerprints | Python Library | Calculates molecular fingerprints and descriptors | 0D, 1D, 2D descriptors | Free open source | Python only [26] |

| Dragon | Desktop Application | Comprehensive descriptor calculation (now discontinued) | 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors | Proprietary, commercial | GUI, CLI, KNIME [26] |

| PaDEL-descriptor | Java Application | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | 0D, 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors | Free | GUI, CLI, KNIME [26] |

Diagram 2: Tool Selection Guide. This decision tree helps researchers select appropriate software tools based on their technical requirements and constraints.

Structuring the input space through careful selection and preprocessing of quantum chemical descriptors establishes the foundation for effective Gaussian process surrogates in quantum chemistry applications. By implementing the protocols outlined in this application note—from comprehensive descriptor taxonomies to sophisticated preprocessing techniques and specialized GP implementations—researchers can significantly enhance the predictive performance of their models while managing computational costs.

The emerging paradigm emphasizes opportunistic data utilization through multitask learning and descriptor repurposing, allowing models to leverage existing heterogeneous data sources [27] [31]. As quantum computing hardware advances, quantum Gaussian process regression with specialized quantum kernels offers promising avenues for capturing complex molecular relationships that challenge classical methods [7].

Future developments will likely focus on automated descriptor selection algorithms, integrated pipelines combining quantum simulation with machine learning, and standardized benchmarking protocols for evaluating descriptor efficacy across diverse molecular domains. By adopting systematic approaches to descriptor management, researchers can unlock more of the potential in Gaussian process surrogates for accelerating quantum chemistry-driven discovery across pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

The accurate mapping of chemical configuration space is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science, particularly for developing robust machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and quantum chemistry models. The configuration space, or potential energy surface (PES), encompasses all possible spatial arrangements of atoms within a molecular system, with each point corresponding to a specific energy value. Efficiently sampling this high-dimensional space is computationally challenging yet critical for capturing both stable equilibrium states and the transition states that dictate chemical reactivity. Within the context of using Gaussian process surrogates for quantum chemistry calculations, sophisticated sampling strategies become indispensable for constructing accurate models while minimizing computationally expensive electronic structure calculations. This document outlines key strategies and provides detailed protocols for the efficient sampling of chemical configuration space, enabling more effective construction of Gaussian process regression (GPR) models and other surrogate surfaces in quantum chemistry.

Key Sampling Strategies and Quantitative Comparisons

Several advanced strategies have been developed to address the challenges of sampling high-dimensional chemical spaces. These methods range from those designed to explore reactive pathways to those that efficiently select diverse training sets for machine learning models. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these key strategies.

Table 1: Key Strategies for Sampling Chemical Configuration Space

| Strategy Name | Primary Sampling Focus | Key Advantage | Reported Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPR-Accelerated Saddle Point Search [32] | Transition states on PES | Order-of-magnitude reduction in electronic structure calculations | ~10x fewer calculations than dimer method [32] |

| Automated Reaction Space Sampling [33] | Reaction pathways and transition states | Fully automated; no reliance on human intuition | Combines fast tight-binding with selective high-level refinement [33] |

| Gradient-Guided FPS (GGFPS) [34] | Molecular configurations for ML training | Superior data efficiency; reduces prediction error variance | Up to 2x reduction in training cost vs. FPS [34] |

| Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) [35] | Chemical feature space for small datasets | Enhances model performance with limited data | Outperforms random sampling, especially on small sets [35] |

The quantitative performance of these strategies is critical for resource-intensive computational research. The application of Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) acceleration to minimum mode following (dimer) methods has demonstrated an order-of-magnitude reduction in the number of required electronic structure calculations when locating saddle points, a common bottleneck in reaction pathway analysis [32]. For machine learning applications, Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) in a property-designated chemical feature space has been shown to consistently produce models with superior predictive accuracy and robustness compared to those trained on randomly sampled datasets, an effect that is particularly pronounced with smaller training set sizes [35]. The newer Gradient-Guided FPS (GGFPS) further builds upon this by incorporating gradient (molecular force) information, which helps to cure the under-sampling of equilibrium geometries often seen with standard FPS, leading to more balanced training and lower prediction errors [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides step-by-step protocols for implementing two of the most impactful sampling strategies discussed.

Protocol: GPR-Accelerated Saddle Point Search

This protocol describes the implementation of a Gaussian process regression-accelerated minimum mode following method for locating transition states, as detailed by Goswami et al. [32].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Computational Environment: C++ implementation of the GPR surrogate model.

- Quantum Chemistry Engine: Software capable of computing electronic energies and atomic forces (e.g., Hartree-Fock, DFT codes).

- Initial Coordinates: Starting molecular configuration in Cartesian coordinates.

- Dimer Method Code: For estimating the lowest eigenmode of the Hessian matrix.

2. Procedure 1. Initialization: Begin with an initial molecular configuration. Start the dimer method to estimate the direction of the lowest eigenmode. 2. Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform a quantum chemistry calculation (e.g., DFT) at the current geometry to obtain the true energy and atomic forces. 3. GPR Surrogate Update: Use this new data point to update the Gaussian process surrogate model of the potential energy surface. 4. Surrogate-Assisted Optimization: Use the updated GPR model to perform multiple, computationally inexpensive steps of the minimum mode following algorithm. The surrogate model predicts energies and forces, guiding the search for the saddle point without calling the electronic structure calculator. 5. Convergence Check: Assess convergence criteria (e.g., force thresholds). If not converged, return to Step 2. 6. Termination: The procedure terminates once the saddle point geometry is identified, characterized by one imaginary frequency (negative eigenvalue of the Hessian).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative nature of this protocol:

Protocol: Automated Sampling for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

This protocol, derived from the work on automated chemical reaction space sampling [33], outlines a multi-stage procedure for generating diverse training data for MLIPs.

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Reactant Database: A source of initial molecular structures (e.g., GDB-13).

- Structure Generation: OpenBabel (with MMFF94 force field) and RDKit for 3D structure generation and manipulation.

- Fast Quantum Method: GFN2-xTB for initial pathway exploration.

- Pathway Methods: Single-Ended Growing String Method (SE-GSM) and Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) with climbing image (CI-NEB) codes.

- High-Level Refinement: Ab initio software (e.g., DFT) for final data refinement.

2. Procedure 1. Reactant Preparation: * Source molecular skeletons from a database like GDB-13. * Generate canonical SMILES strings and convert them to initial 3D structures using the MMFF94 force field. * Perform a conformational isomer search using tools like Confab. * Re-optimize all final reactant structures with a semi-empirical method (e.g., GFN2-xTB). 2. Product Search (SE-GSM): * For each reactant, automatically generate driving coordinates (e.g., 'BREAK 1 2') using a graph enumeration algorithm. * Run the Single-Ended Growing String Method, guided by these coordinates, to identify possible reaction products and transition states without prior knowledge of the endpoint. * Filter out trivial pathways (e.g., strictly uphill energy trajectories, repetitive structures). 3. Landscape Search (NEB): * For each valid reactant-product-transition state triad, generate initial intermediate "images" via interpolation. * Run the Nudged Elastic Band method with Climbing Image (CI-NEB) to optimize the minimum energy path. * To enhance dataset diversity, sample not only the final converged path but also intermediate paths from the optimization trajectory. Apply filters based on convergence and force thresholds to ensure data quality. 4. Refinement and Database Generation: * Refine the filtered structures (reactants, products, transition states, and pathway images) using a higher-level ab initio method (e.g., DFT) to obtain accurate energies and forces. * Compile the final, diverse dataset of molecular configurations suitable for training robust MLIPs.

The following workflow diagram maps out this multi-stage automated process:

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section catalogs essential software tools and algorithms that form the foundation of modern chemical configuration space sampling methodologies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Configuration Space Sampling

| Tool/Algorithm | Type | Primary Function in Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [32] | Statistical/Machine Learning Model | Acts as a surrogate for the quantum mechanical potential energy surface, drastically reducing the number of expensive electronic structure calculations needed during geometry optimization and transition state searches. |

| Single-Ended Growing String Method (SE-GSM) [33] | Path Sampling Algorithm | Explores reaction pathways from a single reactant to discover unknown products and transition states without prior knowledge of the endpoint, automating reaction network exploration. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB/CI-NEB) [33] | Path Sampling Algorithm | Finds the minimum energy path and accurate transition state between a known reactant and product, providing configurations along the reaction coordinate for MLIP training. |

| Gradient-Guided FPS (GGFPS) [34] | Data Selection Algorithm | Selects a diverse and representative set of molecular configurations from a larger pool (e.g., MD trajectories) for training ML models, using force norms to ensure good coverage of both equilibrium and non-equilibrium structures. |

| Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) [35] | Data Selection Algorithm | Selects the most structurally diverse molecules from a chemical database based on descriptors, maximizing the coverage of chemical feature space in small training sets to improve model generalization. |

| GFN2-xTB [33] | Semi-Empirical Quantum Method | Provides a fast but reasonably accurate quantum mechanical method for initial, large-scale exploration of potential energy surfaces and reaction pathways before high-level refinement. |

| OpenSPGen [24] | Descriptor Generation Tool | Generates sigma profiles, which are physically significant, size-independent molecular descriptors that can be used to define a chemical space for sampling and machine learning. |

| RDKit [33] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Used for generating and manipulating molecular structures, calculating molecular descriptors, and fingerprinting, which are essential for preparing reactants and defining feature spaces for sampling. |

| T900607 | T900607, CAS:261944-52-9, MF:C14H10F5N3O4S, MW:411.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Totarol | (+)-Totarol, CAS:511-15-9, MF:C20H30O, MW:286.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The computational cost of high-fidelity quantum chemistry methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), presents a major bottleneck in computational materials science and drug development research. These calculations become prohibitively expensive for complex simulations like reaction pathway searches, which require hundreds or thousands of energy and force evaluations. On-the-fly surrogate modeling has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome this barrier, creating computationally efficient approximations that learn during simulation execution. This approach is particularly valuable for researchers investigating complex molecular systems and surface reactions where exhaustive sampling of the potential energy surface is necessary.

Gaussian Process Regression has established itself as a cornerstone technique for these surrogate models due to its data efficiency and native uncertainty quantification capabilities. Unlike pre-trained machine learning force fields that require extensive curated datasets, on-the-fly GPR models dynamically build their training set during simulation, making them ideal for exploratory research where comprehensive training data may not exist beforehand. The GPR_calculator package exemplifies this methodology, implementing a hybrid approach that intelligently switches between the surrogate model and expensive first-principles calculations based on predictive uncertainty. This framework provides researchers with a practical tool for accelerating demanding quantum chemistry workflows while maintaining the accuracy required for scientific discovery.

Theoretical Foundations of Gaussian Process Surrogates

Gaussian Process Regression Fundamentals

Gaussian Process Regression is a non-parametric Bayesian machine learning technique that provides a principled framework for uncertainty-aware prediction. In the context of quantum chemistry simulations, a GP defines a distribution over potential energy functions, where the energy and forces of a molecular configuration can be modeled as drawn from a multivariate Gaussian distribution. This distribution is characterized by a mean function, often set to zero after normalizing training data, and a covariance function (kernel) that encodes prior assumptions about the function's smoothness and length scales.

The key advantage of GPR for scientific applications lies in its explicit uncertainty quantification. For any new atomic configuration, the GP provides not only a predicted energy and forces but also an estimate of the prediction variance. This uncertainty estimate enables adaptive sampling strategies where the surrogate model can automatically identify when its predictions are potentially unreliable and request verification from the high-fidelity calculator. The probabilistic nature of GPs makes them particularly data-efficient compared to neural network approaches, often achieving chemical accuracy with relatively small training sets—a critical advantage when each training point requires an expensive DFT calculation.

Mathematical Framework

The GPR model assumes that the target values (energies and forces) are drawn from a Gaussian process characterized by a kernel function (k(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{x'})) that defines relationships between input vectors [36]. For a set of training data ({\boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{Y}}), the predictive distribution for a new test point (\boldsymbol{x}_*) is Gaussian with mean and variance given by:

[ \bar{f}* = \boldsymbol{k}^T\boldsymbol{K}^{-1}\boldsymbol{Y} ] [ \mathbb{V}[f_] = k(\boldsymbol{x}*, \boldsymbol{x}) - \boldsymbol{k}_^T\boldsymbol{K}^{-1}\boldsymbol{k}_* ]