Analytical Method Validation for Pharmaceutical Quantification: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Practices, and Regulatory Compliance

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for analytical method validation in pharmaceutical quantification.

Analytical Method Validation for Pharmaceutical Quantification: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Practices, and Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for analytical method validation in pharmaceutical quantification. It explores foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation protocols aligned with ICH Q2(R1), FDA, and EMA guidelines. Covering critical parameters from specificity and linearity to robustness and lifecycle management, the content addresses common challenges in techniques like HPLC and LC-MS/MS, offers optimization strategies, and emphasizes the role of validation in ensuring product quality, regulatory compliance, and patient safety.

The Pillars of Reliability: Understanding Analytical Method Validation and Its Regulatory Landscape

Defining Analytical Method Validation and Its Critical Role in Pharmaceutical Quality

Analytical method validation is the documented process of demonstrating that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring that the method consistently provides reliable and accurate data about the quality of a pharmaceutical product [1]. This process confirms that a method's performance characteristics—such as accuracy, precision, and specificity—meet predefined acceptance criteria established during method development [2]. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, validated analytical methods form the foundation of quality control, ensuring that drug products meet stringent standards for quality, safety, and efficacy throughout their lifecycle [1].

The role of analytical method validation extends beyond technical compliance to become a fundamental requirement for regulatory submissions worldwide. Regulatory bodies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and other international authorities require extensive validation data for both clinical trial applications and marketing authorizations [2]. Without properly validated methods, pharmaceutical companies risk unreliable data, regulatory noncompliance, and potential product recalls, making method validation an indispensable component of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing [1].

Core Validation Parameters and Their Significance

Analytical method validation systematically evaluates specific performance characteristics to ensure the method produces trustworthy results. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, particularly ICH Q2(R2), define the core parameters that must be assessed during validation [3] [4]. These parameters collectively demonstrate that an analytical procedure is fit-for-purpose, with the specific validation requirements depending on the type of method being validated (e.g., identification, impurity testing, or assay).

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters and Their Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Role in Method Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [1] [3] | Closeness of test results to the true value | Ensures method measures what it claims to measure |

| Precision [1] [3] | Degree of agreement among repeated measurements | Confirms method reproducibility under normal conditions |

| Specificity [1] [3] | Ability to distinguish analyte from interfering components | Demonstrates method selectivity in complex matrices |

| Linearity [3] | Ability to produce results proportional to analyte concentration | Establishes method's quantitative capabilities |

| Range [3] | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity | Defines method's operational boundaries |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) [1] [3] | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected | Determines method sensitivity for trace analysis |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) [1] [3] | Lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision | Establishes lower limit for reliable quantification |

| Robustness [1] [3] | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters | Assesses method reliability during normal use |

Each validation parameter serves a distinct purpose in establishing overall method reliability. Accuracy confirms that the method measures what it claims to measure, typically assessed by analyzing samples of known concentration or through spiking studies [1] [3]. Precision, which includes repeatability (intra-assay), intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst), and reproducibility (inter-laboratory), confirms that the method produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to multiple samplings of a homogeneous sample [3]. Specificity ensures the method can accurately measure the analyte in the presence of potential interferents like impurities, degradation products, or excipients, which is particularly critical for stability-indicating methods [1].

The relationship between these parameters creates a comprehensive picture of method performance. For instance, the validation of linearity and range establishes the concentration interval over which the method provides accurate and precise results, while LOD and LOQ define the method's sensitivity at lower concentration levels [3]. Robustness testing evaluates the method's resilience to small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters like temperature, pH, or mobile phase composition, helping to establish system suitability criteria and identify critical control points for consistent method application [1] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Accuracy and Precision Assessment

The experimental protocol for determining accuracy involves analyzing samples with known concentrations of the target analyte and comparing the measured values to the true values [3]. This is typically performed using a minimum of nine determinations across a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range [3]. For drug substance analysis, accuracy may be assessed by applying the method to synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities of impurities, or by comparing results with those from a well-characterized reference method [3]. For drug products, accuracy is often determined through recovery studies using placebo formulations spiked with known amounts of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

Precision validation encompasses repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility. Repeatability (intra-assay precision) is assessed by performing a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration, or nine determinations covering the complete specified range [3]. Intermediate precision evaluates the influence of random events within the same laboratory, such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment, with experimental designs that incorporate these variables systematically. Reproducibility expresses the precision between different laboratories, typically assessed during method transfer studies [3]. The results for both accuracy and precision are expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) for precision and percentage recovery for accuracy, with acceptance criteria dependent on the method's intended use and the stage of product development.

Specificity and Linearity Evaluation

Specificity experiments demonstrate that the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [1] [3]. The protocol typically involves challenging the method with samples containing potential interferents and demonstrating that the analyte response is unaffected. For chromatographic methods, this includes demonstrating resolution between closely eluting peaks, while for spectroscopic methods, it may involve showing no interference at the detection wavelength. For stability-indicating methods, specificity is proven by subjecting the sample to stress conditions (forced degradation) and demonstrating that the method can separate and quantify degradation products from the main analyte [1].

Linearity is established by preparing and analyzing a series of solutions with concentrations spanning the declared range of the method, typically using a minimum of five concentration levels [3]. The results are evaluated by plotting the response as a function of analyte concentration and applying statistical analysis of the regression line, including the y-intercept, slope, and correlation coefficient. The range is derived from the linearity data and is established by confirming that the method provides acceptable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity across the entire concentration interval [3].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

The landscape of analytical method validation has evolved significantly, with traditional approaches being supplemented by modern, risk-based methodologies. The recent simultaneous publication of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 represents a significant shift from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" approach to a more scientific, lifecycle-based model [3]. This evolution reflects the pharmaceutical industry's growing sophistication in analytical science and the need for more flexible, efficient validation strategies.

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Modern Validation Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Modern Lifecycle Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | One-time event after method development [3] | Continuous process throughout method lifetime [3] |

| Focus | Verification of predefined parameters [3] | Understanding and controlling method performance [3] |

| Regulatory Foundation | ICH Q2(R1) [3] | ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 [3] |

| Key Tool | Fixed validation protocol [3] | Analytical Target Profile (ATP) [5] |

| Change Management | Requires revalidation for most changes [1] | Science- and risk-based change management [3] |

| Data Utilization | Limited to validation report | Ongoing performance monitoring [5] |

The modern validation approach introduces the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) as a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance characteristics [3] [5]. By defining the ATP at the beginning of method development, laboratories can employ a risk-based approach to design a fit-for-purpose method and a validation plan that directly addresses its specific needs. This represents a fundamental shift from "validation as a conclusion" to "validation as a confirmation of proper design."

The enhanced approach described in ICH Q14, while requiring a deeper understanding of the method, allows for more flexibility in post-approval changes through a risk-based control strategy [3]. This is particularly valuable in today's fast-paced development environment, where methods may need to be adapted to changing manufacturing processes or analytical technologies. The traditional and modern approaches are not mutually exclusive; rather, the modern approach builds upon the foundation of traditional parameters while providing a more comprehensive framework for ensuring long-term method reliability.

Method-Comparison Studies: Protocols and Statistical Analysis

Method-comparison studies are essential when introducing a new method to determine if it produces results equivalent to an established reference method [6]. The fundamental question addressed is whether one can measure the same analyte with either method and obtain comparable results, making these studies critical for method transfers, replacements, or technology upgrades.

Experimental Design for Method-Comparison

Proper design of a method-comparison study requires careful consideration of several factors. The samples should cover the entire reportable range of the method and should be measured simultaneously by both methods to avoid time-related changes in the sample [6]. The number of samples should be sufficient to provide statistical power, typically at least 40 samples distributed across the measuring range, with more samples required if the range is wide [6]. The samples should ideally be native patient samples representing the typical population encountered in routine testing, rather than spiked samples or standards, to ensure the comparison reflects real-world conditions.

Statistical Analysis and Interpretation

The statistical analysis of method-comparison data has evolved, with current recommendations emphasizing both regression analysis and difference plots (Bland-Altman plots) [6] [7]. While correlation coefficients were historically used, they are now considered insufficient because they measure the strength of relationship rather than agreement between methods [7]. Perfect correlation (r = 1.000) does not mean the methods agree—systematic differences can still exist [7].

Regression analysis, particularly Deming regression, provides estimates of constant systematic error (through the y-intercept) and proportional systematic error (through the slope) [7]. These estimates allow for the calculation of the predicted bias at any medically important decision level, providing crucial information about the clinical impact of method differences.

Bland-Altman analysis involves plotting the difference between the two methods against the average of the two methods [6] [7]. This visualization helps identify trends in the differences across the measuring range and establishes the limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations of the differences), within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are expected to fall [6].

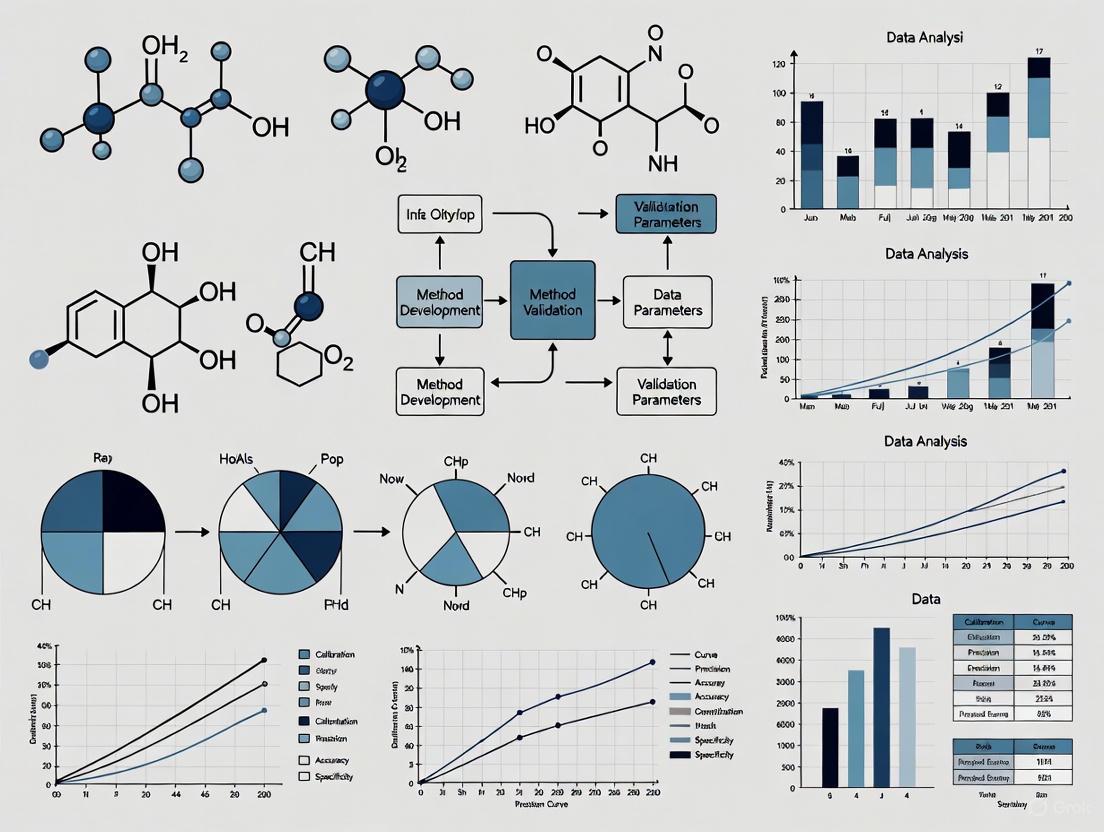

Method Comparison Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful analytical method validation relies on high-quality reagents and materials that ensure method reliability and reproducibility. The selection of appropriate reagents constitutes a critical aspect of method development and validation, directly impacting the method's performance characteristics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards [7] | Primary measure of accuracy; defines the analytical scale | Certified purity, proper documentation, and storage conditions |

| Chromatographic Columns | Defines separation characteristics; impacts specificity | Column chemistry, lot-to-lot reproducibility, stability |

| Mobile Phase Reagents | Creates separation environment; affects retention and selectivity | HPLC-grade purity, low UV absorbance, controlled pH |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Extract, isolate, or derivative analytes; minimize matrix effects | Purity, minimal background interference, lot consistency |

| Quality Control Materials [7] | Monitor method performance over time; assess precision | Commutability with patient samples, defined target values, stability |

| Cu(II)GTSM | Cu(II)GTSM, MF:C6H10CuN6S2, MW:293.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Methyl-1-propylhydrazine | 1-Methyl-1-propylhydrazine, CAS:4986-49-6, MF:C4H12N2, MW:88.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The quality of reference standards deserves particular emphasis, as these materials serve as the foundation for method accuracy [7]. Pharmacopeial standards, when available, provide the highest level of confidence due to their rigorous characterization and certification processes. For novel compounds without official standards, well-characterized in-house standards with comprehensive certificates of analysis are essential. During validation, it's advisable to analyze both commercial calibrators and primary standards together when possible to verify agreement, with any discrepancies investigated and resolved before proceeding with full validation [7].

The movement toward Quality-by-Design (QbD) principles in analytical method development further emphasizes the importance of understanding how reagent attributes affect method performance [5]. By applying risk assessment tools to identify critical reagent attributes, scientists can establish appropriate control strategies that ensure method robustness throughout its lifecycle. This proactive approach to reagent selection and qualification contributes significantly to reducing method variability and maintaining data integrity.

Analytical method validation stands as an indispensable discipline within pharmaceutical quality systems, serving as the critical bridge between method development and routine application. The evolving regulatory landscape, characterized by the adoption of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14, emphasizes a lifecycle approach that integrates development, validation, and ongoing monitoring into a seamless continuum [3]. This paradigm shift from a one-time validation event to continuous method verification represents the future of analytical quality in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The critical role of analytical method validation extends beyond regulatory compliance to fundamentally underpin product quality and patient safety. As pharmaceutical therapies become increasingly complex—with the rise of biologics, gene therapies, and personalized medicines—the demands on analytical methods and their validation will continue to intensify [8] [5]. By embracing modern validation approaches, implementing robust statistical analyses in method-comparison studies, and maintaining rigorous standards for research reagents, pharmaceutical scientists can ensure that analytical methods consistently generate reliable data to support the development and manufacture of high-quality drug products.

Analytical method validation is a critical process in pharmaceutical development that confirms a particular analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and consistency of data used to assess drug safety, quality, and efficacy. Regulatory frameworks provide structured approaches to validate these methods, with global harmonization efforts aimed at standardizing requirements across regions. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and United States Pharmacopeia (USP) establish the primary guidelines governing this field. For pharmaceutical manufacturers and researchers, understanding the similarities, differences, and recent updates within these frameworks is essential for regulatory compliance and successful application submissions across international markets.

The validation of analytical methods underpins the entire drug development lifecycle, from initial discovery through commercial manufacturing and post-approval changes. These methods are used to assess critical quality attributes including drug identity, potency, purity, and performance characteristics. As pharmaceutical modalities evolve to include more complex molecules such as biologics, cell therapies, and gene therapies, the analytical methods and their validation requirements must similarly advance. Recent trends emphasize a lifecycle approach to method validation, incorporating principles of Quality by Design (QbD) and real-time release testing to enhance method robustness while accelerating time-to-market.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

Table 1: Key Regulatory Guidelines for Analytical Method Validation

| Guideline | Issuing Authority | Current Version/Status | Geographic Applicability | Primary Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH Q2(R2) | International Council for Harmonisation | Implemented Oct 2025 [9] | Global (ICH member regions) | Analytical procedure validation for drug substances & products |

| FDA Guidance (Pharmaceutical) | U.S. Food and Drug Administration | Aligns with ICH Q2(R2) [5] | United States | Analytical methods for pharmaceutical applications |

| EMA Guideline | European Medicines Agency | Adopted ICH Q2(R2) [4] | European Union | Analytical methods for medicinal products |

| USP General Chapters | United States Pharmacopeia | USP 48-NF 43 (2025) [10] | Primarily United States | Compendial methods and standards |

The regulatory landscape for analytical method validation has recently undergone significant harmonization with the implementation of ICH Q2(R2) in October 2025, which has been adopted by both the FDA and EMA [9] [4]. This represents a major step toward global standardization, replacing previous region-specific requirements. The ICH guideline serves as the foundation for both FDA and EMA expectations, though each agency maintains specific administrative procedures and additional guidance documents for specialized areas such as bioanalytical method validation [11]. Meanwhile, USP standards continue to provide specific monographs and general chapters that define official testing methods and acceptance criteria recognized by FDA as legally enforceable for drugs marketed in the United States [10].

Validation Parameters and Requirements

Table 2: Comparison of Validation Parameters Across Frameworks

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R2) | FDA (Pharma) | EMA | USP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Recovery | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Precision (Intermediate Precision) | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Linearity | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Range | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required |

| Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required | Conditionally Required |

| Robustness | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

All major regulatory frameworks require demonstration of the same fundamental validation parameters, though implementation details may vary slightly. The ICH Q2(R2) guideline provides comprehensive definitions and methodological approaches for establishing each parameter, with FDA and EMA largely adopting these recommendations [4]. The EMA has historically provided more detailed practical guidance on experimental conduct, while FDA documentation offers more comprehensive reporting recommendations [11]. USP standards incorporate these same validation parameters but present them within the context of compendial methods that become legally recognized standards when referenced in a product monograph [10]. A significant evolution in the ICH Q2(R2) guideline is its emphasis on a lifecycle approach to method validation, encouraging continuous method verification and improvement rather than treating validation as a one-time activity [5].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Standard Validation Methodology

The validation of analytical methods follows systematically designed experimental protocols to demonstrate that the method consistently produces reliable results. A standard validation protocol includes the following elements:

Accuracy Studies: Typically determined using spiked recovery experiments with known concentrations of analyte across the specified range (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150% of target concentration). Accuracy should be established for each matrix component in the case of complex formulations. The percent recovery is calculated as

(Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) × 100, with acceptance criteria generally requiring recovery within 98-102% for drug substance assays [4].Precision Evaluation: Conducted at three levels: (1) Repeatability (intra-assay precision) using at least six determinations at 100% of the test concentration; (2) Intermediate precision examining within-laboratory variations (different days, analysts, equipment); and (3) Reproducibility between laboratories for methods transferred between sites. Results are expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD%), with criteria typically requiring ≤2% for assay methods [4].

Specificity/Discrimination: Demonstrated by analyzing samples containing potentially interfering compounds (impurities, excipients, degradation products) to confirm the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of these components. For stability-indicating methods, forced degradation studies (acid/base hydrolysis, oxidation, thermal stress, photolysis) are performed to demonstrate separation of degradation products from the analyte peak [4].

Protocol Implementation Across Frameworks

While the core validation parameters remain consistent across regulatory frameworks, implementation details may vary:

Linearity and Range: Established by preparing analyte solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels across the specified range. The response is plotted against concentration, and statistical analysis (correlation coefficient, y-intercept, slope of regression line) is performed. The ICH Q2(R2) guideline emphasizes that R² values alone are insufficient to demonstrate linearity, requiring additional statistical evaluation of residuals and lack-of-fit [12].

Detection and Quantitation Limits: Determined using signal-to-noise ratio (typically 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ) or based on the standard deviation of the response and slope of the calibration curve (

LOD = 3.3σ/SandLOQ = 10σ/Swhere σ is the standard deviation of response and S is the slope of the calibration curve) [4].Robustness Testing: Evaluated by deliberately varying method parameters (mobile phase composition, pH, flow rate, column temperature) within a realistic range and measuring the impact on method performance. Experimental design approaches such as Design of Experiments (DoE) are increasingly employed to efficiently evaluate multiple parameters simultaneously [5].

Visualization of Regulatory Relationships and Workflows

Figure 1: Regulatory Framework Relationships and Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Quantification and method calibration | Must be of certified purity and traceable to national/international standards |

| Chromatographic Columns | Separation of analytes from impurities | Column performance must be verified; multiple column batches should be evaluated for robustness |

| Biological Matrices | Simulation of in vivo conditions for bioanalytical methods | Source and handling must be documented; stability under storage conditions must be verified |

| Reagent-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation and sample dilution | Must meet purity specifications; potential interference must be characterized |

| System Suitability Standards | Verification of instrument performance prior to analysis | Must be stable and representative of analytes; criteria established in validation protocol |

The selection and qualification of research reagents represents a critical component of method validation. Certified reference standards serve as the foundation for establishing method accuracy, linearity, and range, and must be thoroughly characterized with documentation of purity, storage conditions, and stability data [10]. For chromatographic methods, multiple batches of columns from the same manufacturer and equivalent columns from different manufacturers should be evaluated during robustness testing to ensure method reliability when columns are replaced. In bioanalytical method validation, appropriate biological matrices (plasma, serum, urine) must be sourced and handled according to strict protocols to prevent analyte degradation or interference [13] [11]. All reagents should be accompanied by certificates of analysis and stored according to manufacturer recommendations, with documentation maintained for regulatory inspections.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of analytical method validation continues to evolve in response to technological advancements and regulatory harmonization. Several significant trends are shaping current practices:

Enhanced Lifecycle Management: The integration of ICH Q12 principles with ICH Q2(R2) promotes a more comprehensive lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, emphasizing continuous verification and management of post-approval changes [9] [5]. This represents a shift from traditional "one-time" validation toward ongoing method performance monitoring.

Adoption of Advanced Technologies: Regulatory frameworks are increasingly accommodating sophisticated analytical technologies including high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), multi-attribute methods (MAM), and hyphenated techniques such as LC-MS/MS [5]. These technologies enable more comprehensive characterization of complex molecules but require specialized validation approaches.

Quality by Design (QbD) Principles: Method development and validation increasingly incorporates QbD approaches, employing statistical design of experiments (DoE) to systematically optimize method parameters and establish method operable design regions [5]. This science-based approach enhances method robustness while providing greater regulatory flexibility.

Real-Time Release Testing (RTRT): There is growing regulatory acceptance of RTRT approaches that utilize process analytical technology (PAT) to enable quality control based on process data rather than end-product testing [5]. This shift requires validation of in-line or on-line analytical methods integrated directly into manufacturing processes.

Digital Transformation: Regulatory agencies are increasingly addressing data integrity requirements for computerized analytical systems, with emphasis on the ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate) [5]. Cloud-based laboratory information management systems (LIMS) and electronic notebooks must undergo rigorous validation to ensure data reliability.

The ongoing harmonization of regulatory expectations through ICH initiatives, particularly the implementation of ICH Q2(R2), provides greater consistency for global drug development while accommodating technological innovation in analytical sciences. Pharmaceutical manufacturers and researchers should maintain awareness of these evolving standards to ensure compliance and optimize their analytical development strategies.

In the development and quality control of pharmaceuticals, the reliability of analytical data is paramount. This reliability is established through a rigorous process called analytical method validation, which demonstrates that a laboratory test method is suitable for its intended purpose [14]. For researchers and scientists in drug development, understanding and effectively evaluating the core validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity, and Range—is a fundamental skill. These interconnected parameters form the foundation for ensuring that analytical methods consistently produce trustworthy data to support the safety, efficacy, and quality of drug substances and products [15].

The Pillars of Method Validation: Core Parameters Defined

The five core parameters provide a complete picture of an analytical method's performance, from its basic function to its boundaries of reliable operation. Their definitions and significance are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Definition and Significance of Core Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Core Definition | Significance in Pharmaceutical Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a test result and an accepted reference value (the "true" value) [15] [14]. | Ensures that the measured concentration of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or impurity is correct, directly impacting dosage and safety assessments [16]. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [15] [14]. | Evaluates the method's random error and reproducibility, guaranteeing consistent results across different analysts, days, and equipment [15]. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or excipients [15] [14]. | Confirms that the measured signal is solely from the target analyte, which is critical for identity tests, impurity profiling, and stability-indicating methods [17]. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range [15]. | Demonstrates that the method's response (e.g., chromatographic peak area) is a predictable function of the analyte's concentration, which is foundational for accurate quantification. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has suitable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity [15]. | Defines the operational limits of the method, ensuring it is validated for all concentrations encountered during testing, from the lower limit of quantitation to 120-130% of the specification limit [18]. |

A Quantitative Framework: Acceptance Criteria and Data Interpretation

Establishing pre-defined, justified acceptance criteria is critical for objective method validation [19]. The following table provides a summary of typical acceptance criteria for these parameters, illustrating how quantitative data is used to judge method suitability.

Table 2: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Core Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Data Presentation & Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | ≤ 10% of tolerance (for analytical methods) [20]. Often expressed as % Recovery (e.g., 98-102%) [19]. | Reported as: % Bias, % Recovery, or % of tolerance.Calculation: (Mean Observed Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) * 100 [15]. |

| Precision | Repeatability: ≤ 25% of tolerance (for analytical methods) [20]. Expressed as %RSD (e.g., ≤ 2% for assay) [19]. | Reported as: % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD), Standard Deviation, or % of tolerance.Calculation: (Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100 [20] [15]. |

| Specificity | Demonstrate no interference from blank or placebo. For chromatographic methods, ensure baseline resolution of analytes from potential interferents [15]. | Reported as: Chromatographic resolution, spectral comparison, or demonstration of no response in blank. For quantification, specificity can be reported as a % of tolerance (Excellent: ≤5%) [20]. |

| Linearity | A correlation coefficient (R²) of ≥ 0.998, visually random residual plot, and a y-intercept not significantly different from zero [20] [19]. | Reported as: Correlation coefficient (R²), slope, y-intercept, and residual plot from a linear regression analysis [15]. |

| Range | Specified from a low to high concentration, encompassing the product specification limits. For an assay, typically 80% - 120% of the test concentration [15] [18]. | Defined by: The lowest and highest concentrations for which accuracy, precision, and linearity have been demonstrated. The range must cover all specification limits [18]. |

From Theory to Practice: Experimental Protocols for Parameter Assessment

Protocol for Accuracy and Precision

Accuracy and precision are often evaluated concurrently in a single experimental design [18].

- Methodology: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations across the specified range of the procedure, typically comprising three concentrations (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration), each analyzed in triplicate [15]. The samples are typically prepared by spiking a placebo with known quantities of the reference standard of the analyte [15].

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the mean recovery for each concentration level. The mean recovery should be within the pre-defined acceptance criteria (e.g., 98-102%) [19].

- Precision (Repeatability): Calculate the %RSD for the nine determinations (or for the triplicate at the 100% level). The %RSD should meet the pre-defined criteria [15].

Protocol for Specificity

- Methodology: For an assay, specificity is demonstrated by analyzing samples containing the analyte along with potential interferents. This includes:

- Individually: The pure analyte, the placebo/excipients, and potential impurities or degradation products.

- In Combination: The analyte spiked into the placebo along with impurities/degradation products [15].

- Forced degradation studies (stressing the drug product under acid, base, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic conditions) are also used to demonstrate the method's stability-indicating properties [18].

- Data Analysis: The method is specific if there is no interference from the placebo or degradation products at the retention time of the analyte, and if the analyte peak is pure (as demonstrated by techniques like diode-array detection). For quantification, the recovery of the analyte from the spiked mixture should be within acceptance criteria for accuracy [20].

Protocol for Linearity and Range

- Methodology: Prepare a minimum of five concentrations of the analyte over a range that encompasses the specification limits, typically from 80% to 120% of the target concentration for an assay [15] [18]. Analyze each concentration, and plot the instrument response (e.g., peak area) against the theoretical concentration.

- Data Analysis: Perform linear regression analysis on the data to calculate the correlation coefficient (R²), slope, and y-intercept. Visually inspect the plot of residuals (the difference between the calculated and observed values) versus concentration; it should show no systematic pattern [20]. The range is then established as the interval between the lowest and highest concentrations for which the linearity, accuracy, and precision are acceptable [15].

The workflow below illustrates the strategic sequence for establishing and validating the linear range of an analytical method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful validation study relies on high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table lists key reagent solutions and their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Provides the accepted "true value" for the analyte, serving as the benchmark for all accuracy and linearity assessments. Its purity and qualification are foundational [15]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Ensure the analytical background (e.g., mobile phase, sample solvent) does not generate interfering signals, which is crucial for achieving the required specificity, LOD, and LOQ. |

| Well-Characterized Placebo | A mixture of all drug product excipients without the API. Used in specificity experiments to prove excipients do not interfere, and in accuracy studies for recovery calculations [15]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | A specific mixture used to verify that the analytical system (e.g., HPLC) is performing adequately at the time of the test. It typically checks for parameters like resolution, precision, and tailing factor [15]. |

| Stability-Indicating Solutions | Samples of the drug substance or product that have been intentionally degraded (e.g., by heat, light, acid). Used to rigorously challenge the method's specificity and prove it can monitor stability [18]. |

| Azanium;iron(3+);sulfate | Azanium;iron(3+);sulfate, MF:FeH4NO4S+2, MW:169.95 g/mol |

| N-Boc-6-methyl-L-tryptophan | N-Boc-6-methyl-L-tryptophan|Building Block |

The Interconnected Framework of Analytical Validation

The core validation parameters are not isolated checklist items; they form an integrated system where the performance of one parameter directly influences or depends on others. For instance, the validation of Range is contingent on having already demonstrated acceptable Linearity, Accuracy, and Precision across that interval [15]. Similarly, a method's Accuracy can be compromised by a lack of Specificity if interfering substances contribute to the measured signal [14]. The following diagram illustrates this critical interdependence.

Ultimately, a robust analytical method is one where all core parameters have been thoroughly investigated and balanced. The data generated from these validation studies provides the documented evidence required by regulators and gives drug development professionals the confidence to make critical decisions about product quality, from early development through to commercial batch release [20] [19]. This rigorous approach ensures that every medicine that reaches patients is proven to be safe, effective, and of high quality.

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, ensuring that analytical methods produce reliable, accurate, and reproducible results is paramount. Method validation provides documented evidence that a procedure is fit for its intended purpose and meets regulatory standards. Among the key performance characteristics established during this process are the Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), robustness, and ruggedness. These parameters define the sensitivity and reliability of an analytical method, confirming it can consistently detect and measure analytes at low concentrations and withstand minor, expected variations in operational conditions. This guide explores these advanced parameters, comparing methodologies and providing the experimental protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Understanding the Fundamental Parameters

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ)

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is defined as the lowest concentration of an analyte in a sample that can be reliably detected, though not necessarily quantified, under the stated operational conditions of the method [21] [22]. It represents the point at which a measured signal can be distinguished from background noise with a defined level of confidence. In practice, it is a limit test that specifies whether an analyte is above or below a certain value [23].

The Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), also called the Limit of Quantification, is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy [21] [24]. Unlike the LOD, the LOQ requires that the method provides reliable numerical results at that low concentration, making it crucial for accurate quantification at trace levels [22].

Robustness and Ruggedness

Robustness is the capacity of an analytical method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in its method parameters [25]. It provides an indication of the method's reliability during normal use [21] [26]. In essence, a robust method will yield consistent results despite minor changes in predefined parameters, such as mobile phase pH, column temperature, or flow rate in liquid chromatography (LC) methods.

Ruggedness is a closely related term, often used interchangeably with robustness. However, some interpretations make a distinction: ruggedness may refer to the degree of reproducibility of results under a variety of normal test conditions, such as different analysts, laboratories, instruments, or reagent lots [23] [26]. It is a measure of the method's susceptibility to variations in external, environmental factors.

Experimental Determination and Protocols

Protocols for Determining LOD and LOQ

There are multiple accepted approaches for determining LOD and LOQ. The choice of method depends on the specific application and regulatory requirements.

Table 1: Methods for Determining LOD and LOQ

| Method | Description | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) | Compares the measured signal from a low-concentration sample to the background noise [21] [23]. | LOD: S/N ≥ 3:1 [21] [22]LOQ: S/N ≥ 10:1 [21] [22] | Chromatographic methods (HPLC, LC-MS) where baseline noise is easily measurable. |

| Standard Deviation of the Response and Slope | Uses the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [23]. | LOD = 3.3 × (SD/S)LOQ = 10 × (SD/S)Where SD = standard deviation of response, S = slope of the calibration curve [23]. | A statistical approach applicable when a calibration curve is available; often used in a regulated environment. |

| Empirical Protocol (Based on CLSI Guideline EP17) | A rigorous statistical method involving the analysis of blank and low-concentration samples [27]. | LoB = meanblank + 1.645(SDblank)LOD = LoB + 1.645(SDlow concentration sample)LOQ ≥ LOD, meeting predefined bias/imprecision goals [27]. | Provides a high level of confidence; used to fully characterize assay performance at low concentrations, particularly in clinical laboratories. |

The following workflow outlines the typical process for determining LOD and LOQ using the signal-to-noise and statistical calculation methods:

Protocols for Evaluating Robustness and Ruggedness

The evaluation of robustness involves deliberately introducing small, plausible variations into method parameters and monitoring their effect on key method responses [25]. A typical protocol involves the following steps:

Factor Identification: Select factors from the method's operating procedure that are likely to vary. For an LC method, this could include:

Experimental Design: Use a structured experimental design, such as a Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial design, to efficiently screen a large number of factors with a minimal number of experimental runs [25].

Execution and Analysis: Perform the experiments in a randomized order and analyze the results. Calculate the effect of each factor variation on the responses, which can include quantitative results (e.g., assay value, impurity content) or system suitability parameters (e.g., resolution, tailing factor) [25].

The results of a robustness test are used to define which parameters need strict control and to set evidence-based limits for System Suitability Tests (SSTs) to ensure the method's validity whenever it is used [25].

Ruggedness, when distinguished from robustness, is assessed through intermediate precision or reproducibility studies. This involves testing the same set of samples under different conditions, such as with different analysts, on different instruments, in different laboratories, or on different days [23]. The results are compared using statistical measures like the Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) or a Student's t-test to determine if there is a significant difference between the results obtained under the varied conditions.

Comparative Analysis and Data Presentation

Comparison of LOD and LOQ Determination Methods

Table 2: Comparison of LOD and LOQ Methodologies

| Aspect | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Statistical (SD/Slope) | Empirical (EP17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Low | Medium | High |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Widely accepted, especially in chromatography [23] [22] | Accepted by ICH and other guidelines [23] | High, based on CLSI standard [27] |

| Key Advantage | Simple and quick to perform | Based on calibration data, less arbitrary | Most rigorous; provides high statistical confidence |

| Key Limitation | Requires a clear, measurable baseline; can be subjective | Relies on the quality of the calibration curve | Resource-intensive (requires ~60 replicates for establishment) [27] |

| Ideal Use Case | Routine, in-lab verification of method sensitivity | Full method validation for regulatory submission | Critical applications where the lowest reliable limits must be definitively known |

Key Factors for Robustness Testing in Chromatography

The parameters tested for robustness are highly method-dependent. The following table lists common factors for Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) methods, which are particularly sensitive to variations.

Table 3: Key Factors for Robustness Evaluation in LC-MS Methods

| Parameter Category | Specific Factor | Likelihood of Uncontrollable Change | Recommended Variation | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography | Mobile phase pH | Medium | ± 0.5 units | Strong effect on retention if analyte pKa is near mobile phase pH [28] |

| Organic solvent content | Low to Medium | ± 2% (relative) | Influences retention time and analyte signal in MS [28] | |

| Column temperature | Low | ± 5 °C | Influences retention time and resolution [28] | |

| Flow rate | Low | ± 20% | Influences retention time and resolution [28] | |

| Column batch/age | Medium | Different batches | Can affect retention time, peak shape, and ionization [28] | |

| Sample Preparation | Injection solvent composition | Low/High | ± 10% (relative) | Can seriously affect retention and peak shape, especially in UHPLC [28] |

| Matrix effect (sample source) | High | 6 different sources | Influences recovery and ionization suppression; critical for LoQ/LoD [28] | |

| Mass Spectrometry | Drying gas temperature | Low | ± 10 °C | Can influence analyte ionization efficiency [28] |

| Nebulizer gas pressure | Low | ± 5 psi | Can influence analyte ionization efficiency [28] |

The relationship between the core validation parameters and the experimental workflow for robustness testing is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for successfully validating analytical methods, particularly in pharmaceutical quantification.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Item | Function / Role in Validation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standards | Certified reference materials are essential for accurate preparation of calibration standards and spiked samples to determine accuracy, LOD, LOQ, and linearity [23]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents and Additives | High-purity solvents minimize background noise and ion suppression in MS, directly impacting the accuracy of S/N measurements for LOD/LOQ and the reliability of robustness tests [28]. |

| Characterized Chromatographic Columns | Multiple columns from different batches are used during robustness testing to evaluate the method's sensitivity to this critical component [28] [25]. |

| Buffer Solutions with Calibrated pH Meters | Essential for precise mobile phase preparation. Small variations in pH are a key factor in robustness studies, especially for ionizable analytes [28]. |

| Simulated or Real Matrix Blanks | Required for determining the Limit of Blank (LoB), which is the first step in the empirical LOD protocol, and for assessing specificity and matrix effects [27]. |

| (Z)-pent-3-en-2-ol | (Z)-pent-3-en-2-ol|For Research |

| 3-O-Methyl 17beta-Estradiol | 3-O-Methyl 17beta-Estradiol|RUO |

A thorough understanding and rigorous application of LOD, LOQ, robustness, and ruggedness parameters form the bedrock of a reliable analytical method. While LOD and LOQ define the fundamental boundaries of a method's sensitivity, robustness and ruggedness quantify its reliability and transferability under realistic conditions. The experimental data and protocols presented here provide a framework for pharmaceutical scientists to design validation studies that not only comply with regulatory guidelines but also ensure that their analytical methods will perform consistently in quality control laboratories, during technology transfers, and throughout the drug development lifecycle. Employing a structured approach to these advanced parameters ultimately de-risks the analytical process and bolsters confidence in the data generated for critical pharmaceutical products.

The Impact of Inadequate Validation on Product Safety and Regulatory Submissions

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical development, the validation of analytical methods is not merely a regulatory formality but a critical cornerstone for ensuring product safety and efficacy. Inadequate validation can compromise the entire drug development lifecycle, leading to the release of substandard products and causing significant regulatory setbacks. Analytical method validation provides the essential data that regulatory agencies rely on to assess the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products. When these methods are not properly developed and validated, the consequences extend far beyond the laboratory, directly impacting patient health and a company's ability to bring vital medicines to market. This article explores the tangible impacts of validation failures, supported by recent research and case studies, and provides a structured overview of the protocols necessary to maintain the highest standards in pharmaceutical analysis.

The Critical Role of Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Defining Analytical Method Validation

Analytical method validation is the formal, systematic process of proving that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose [29]. It involves a series of laboratory studies to demonstrate that the method consistently produces accurate, reliable, and reproducible data when used to test a pharmaceutical material. Key parameters established during validation include accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness [29]. These parameters are globally harmonized under guidelines such as ICH Q2(R1) and are non-negotiable for regulatory submissions to bodies like the FDA and EMA [29].

Linking Validation to Product Safety and Regulatory Success

A properly validated method acts as a primary control, ensuring that every batch of a drug product contains the correct amount of the active ingredient, is free from harmful levels of impurities, and will maintain its quality and stability throughout its shelf life [29]. Without this assurance, patients may be exposed to significant risks. Concurrently, regulatory agencies mandate validated methods to ensure that the data submitted in support of product approvals—such as New Drug Applications (NDAs) or Investigational New Drug (IND) applications—is scientifically sound and reliable [29]. Inadequate validation is a common root cause of regulatory actions, including Complete Response Letters and clinical holds, which can derail development timelines and require costly remediation efforts [30].

Documented Impacts of Inadequate Validation

Compromised Product Safety and Quality

Recent studies on products from illegal and unregulated markets provide stark evidence of how a lack of controlled manufacturing and quality oversight leads to dangerous products reaching consumers.

Case Study: Illicit Pregabalin and Bodybuilding Supplements

- Pregabalin Content Variability: Analysis of 40 suspicious pregabalin samples from the Saudi Arabian market revealed significant variability in pregabalin content. Furthermore, about 30% of the samples contained toxic adulterants, posing a direct threat to consumer safety [31].

- Undeclared Active Ingredients: In a broader study of 601 samples seized from the illegal market, which were suspected to contain substances like selective estrogenic receptor modulators (SERMs) and aromatase inhibitors, 35% of the samples did not contain the declared active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Even when the declared API was present, 6.4% of samples contained an additional, undeclared API, creating a high risk of unintended side effects and drug interactions [31].

- Contaminated Dietary Supplements: The application of a combined LC-MS Q-TOF/1H-NMR approach to dietary supplements purchased online found unauthorized botanical extracts containing L-dopa. These products were either overdosed or under-dosed, highlighting the critical absence of quality control in their production [31].

These findings from the field underscore a fundamental principle: the absence of a robust quality framework, which includes validated analytical methods, allows substandard and falsified products to proliferate, directly endangering public health.

Regulatory and Commercial Consequences

The regulatory pathway for a new drug is complex and demanding. Inadequate validation of the analytical methods used to generate critical data is a frequent contributor to submission failures.

Common Regulatory Deficiencies

Regulatory remediation specialists identify several common areas where inadequate validation leads to submission stalls [30]:

- Data Integrity Gaps: Discrepancies between datasets and summary documents, or concerns about electronic data compliance (e.g., 21 CFR Part 11), can undermine the credibility of an entire submission [30].

- Scientific and Clinical Data Gaps: This includes insufficient statistical analyses, inadequate safety signal characterization, and ambiguities in endpoint data, all of which can originate from analytical methods that are not fit-for-purpose [30].

- CMC and Manufacturing Issues: Incomplete process validation, inadequate stability data, and gaps in demonstrating control over the manufacturing process are red flags for regulators [30]. For instance, failing to establish scientifically justified residue limits in cleaning validation is a common cause of FDA 483 observations [32].

Overcoming these deficiencies requires comprehensive remediation, including root cause analysis, data reanalysis, and rigorous response document preparation—processes that demand significant time and resources and delay patient access to new therapies [30].

Essential Analytical Method Validation Protocols

To avoid the severe consequences of inadequate validation, the pharmaceutical industry adheres to strict, internationally recognized validation protocols. The following workflow and parameters, based primarily on ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, outline the standard approach.

Core Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

The table below details the core parameters, their definitions, and standard experimental methodologies as per ICH guidelines [29].

Table 1: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters and Protocols

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Protocol & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | Protocol: Inject samples of placebo, analyte, and analyte spiked with potential interferents (impurities, degradants). Acceptance: Peak purity tools confirm analyte peak is pure; resolution from nearest interfering peak is typically > 2.0. |

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the conventional true value and the value found. | Protocol: Spike a known amount of analyte into a placebo matrix at multiple levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150% of target). Analyze replicates. Acceptance: Mean recovery should be 98–102% for API assay. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. | Protocol: - Repeatability: Analyze 6 samples at 100% concentration. - Intermediate Precision: Different analyst/day/equipment. Acceptance: RSD < 1.0% for API assay repeatability. |

| Linearity | The ability to obtain test results proportional to the analyte concentration. | Protocol: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentrations across a specified range (e.g., 50-150% of target). Plot response vs. concentration. Acceptance: Correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.999. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte for which suitability is demonstrated. | Protocol: Established from linearity and precision data. Must encompass the intended working concentrations. |

| Robustness | A measure of method capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Protocol: Small changes in HPLC conditions (e.g., flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, temperature ±2°C, mobile phase pH ±0.1). Acceptance: System suitability criteria are still met in all variations. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of validated methods relies on high-quality, consistent materials. The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in analytical methods like HPLC.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Highly purified, well-characterized substance used as a benchmark for quantifying the analyte and confirming method identity and specificity [29]. |

| Chromatography Columns | The heart of HPLC/UPLC separation; different chemistries (C18, C8, phenyl) are selected to achieve optimal resolution of the API from impurities and matrix components [29]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity mobile phase components that minimize baseline noise, prevent system damage, and ensure reproducible retention times and detector response. |

| Biological Indicators (BIs) | Used in sterilization validation; contain a known population of highly resistant microbial spores (e.g., Geobacillus stearothermophilus) to challenge and verify the efficacy of sterilization cycles [33]. |

| Chemical Indicators | Used in sterilization validation; verify that physical parameters (e.g., temperature, radiation dose) were delivered to the product location [33]. |

| Anti-osteoporosis agent-2 | Anti-osteoporosis agent-2|Research Compound |

| Cerium(3+);acetate;hydrate | Cerium(3+);acetate;hydrate, MF:C2H5CeO3+2, MW:217.18 g/mol |

The evidence is clear: inadequate validation of analytical methods and related processes has a direct and profound impact on pharmaceutical product safety and regulatory success. From the very real dangers of adulterated and mislabeled products in illegal markets to the costly regulatory roadblocks faced by compliant companies, the stakes could not be higher. Adherence to established validation protocols, such as ICH Q2(R1), is not a bureaucratic hurdle but a fundamental prerequisite for ensuring that every drug product is safe, effective, and of high quality. As the industry evolves with the adoption of Quality by Design (QbD) principles [34] and more advanced analytical technologies, the foundational requirement for rigorous, well-documented validation remains constant. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a steadfast commitment to validation excellence is synonymous with a commitment to patient safety and therapeutic innovation.

From Theory to Practice: Method Development and Application Across Analytical Techniques

The landscape of pharmaceutical analytical method development has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from traditional empirical approaches to systematic, science-driven methodologies. This evolution is largely guided by the Quality by Design (QbD) framework, a proactive system rooted in ICH Q8-Q11 guidelines that emphasizes building quality into products and processes through predefined objectives rather than relying solely on end-product testing [35]. Systematic method development represents a structured approach that begins with predefined objectives and emphasizes product and process understanding based on sound science and quality risk management [5] [35]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, adopting this systematic workflow is crucial for developing robust, reliable analytical methods that not only meet stringent regulatory standards but also enhance operational efficiency and reduce the risk of late-stage failures.

The core distinction between traditional and modern approaches lies in their fundamental philosophy. Traditional pharmaceutical quality control historically relied on reactive endpoint testing and empirical "trial-and-error" development, which often led to batch failures, recalls, and regulatory non-compliance due to insufficient understanding of critical quality attributes and process parameters [35]. In contrast, systematic method development under the QbD framework employs proactive risk management and structured experimentation to establish method robustness, design space, and control strategies, thereby ensuring consistent method performance throughout its lifecycle [5] [35].

Foundational Principles of Systematic Method Development

Core QbD Principles for Analytical Methods

Systematic method development under the QbD framework is governed by several interconnected principles that collectively ensure method robustness and reliability. The foundation begins with establishing the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), which defines the method's intended purpose and performance requirements [35]. This is followed by identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) that link product quality attributes to safety and efficacy using risk assessment and prior knowledge [35]. A systematic risk assessment then evaluates material attributes and process parameters impacting CQAs, leading to the identification of Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) [5] [35].

The principle of design space establishment is central to QbD—it defines the multidimensional combination of input variables (e.g., mobile phase composition, pH, temperature) that have been demonstrated to ensure method quality as defined by CQAs [35]. Operating within the design space provides regulatory flexibility, as changes within this established space do not require re-approval [35]. A control strategy implements monitoring and systems to ensure method robustness, while lifecycle management emphasizes continuous improvement through ongoing performance monitoring and method refinement [5].

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

The systematic approach to method development aligns with global regulatory expectations outlined in various ICH guidelines. ICH Q8(R2) provides the foundation for Pharmaceutical Development and introduces the concepts of QTPP, CQAs, and design space [35]. ICH Q9 formalizes Quality Risk Management, providing systematic processes for assessment, control, communication, and review of risks [35]. ICH Q10 outlines the Pharmaceutical Quality System, while ICH Q11 covers Development and Manufacture of Drug Substances [35].

For analytical procedures specifically, ICH Q2(R1) and the forthcoming ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 set the benchmark for method validation, emphasizing precision, robustness, and data integrity [5]. These guidelines collectively provide a comprehensive framework for developing and validating analytical methods that meet global regulatory standards from agencies including the FDA and EMA [5] [35].

The Systematic Method Development Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: Define Method Objectives and Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP)

The initial phase of systematic method development establishes a clear foundation by defining the method's purpose and performance expectations. This begins with establishing a prospectively defined summary of the analytical method's quality characteristics [35]. The QTPP document lists target attributes including the specific analyte, required sensitivity (detection and quantification limits), precision, accuracy, linearity range, robustness requirements, and intended application [35] [36]. For pharmaceutical quantification methods, the purpose typically involves measuring Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), related substances, residual solvents, or other impurities to evaluate potency, bioavailability, and stability [36].

Defining the QTPP requires understanding the analytical method's role in the broader product development pipeline. This includes considering whether the method will be used for release testing, stability studies, in-process testing, or characterization [5]. Each application has distinct requirements that influence method development strategy. For instance, stability-indicating methods must adequately separate and quantify degradation products, while release methods focus on accuracy and precision for specific quality attributes [5] [36].

Step 2: Analyze Analyte and Review Existing Knowledge

Comprehensive analyte characterization and literature review form the scientific foundation for efficient method development. Analyte characterization involves collecting biological, chemical, and physical properties of the analyte, including pKa values, solubility profile across different pH ranges, stability under various conditions (light, heat, pH), spectral properties, and chromophore characteristics [36]. This information guides selection of appropriate analytical techniques and conditions.

A thorough literature review assesses previous methodologies, publications, and regulatory submissions for the same analyte or structurally similar compounds [36]. This step examines journals, books, pharmacopeial monographs, and internal company databases to identify established methods that can be adapted or optimized [36]. The review should also consider prior knowledge from related molecules or analytical platforms, which can inform risk assessment and experimental design [35]. If no suitable previous methods exist in the literature, the development proceeds without this foundation, requiring more extensive experimentation [36].

Step 3: Select and Design the Analytical Method

Based on the QTPP and knowledge gathered, an appropriate analytical technique is selected and initially designed. For pharmaceutical quantification, chromatographic techniques—particularly High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC)—are most commonly employed due to their versatility, sensitivity, and ability to separate complex mixtures [5] [36] [37]. The selection process considers the nature of the analyte (volatility, polarity, molecular weight), required sensitivity, sample matrix, and available instrumentation [36].

Method design involves making initial decisions on key parameters, including detection technique (UV, MS, CAD), column chemistry (C18, C8, HILIC, etc.), mobile phase composition (aqueous/organic ratio, buffer type and pH), and preliminary gradient or isocratic conditions [36] [37]. This stage may also incorporate hyphenated techniques such as LC-MS/MS for enhanced specificity and sensitivity, particularly for complex matrices or trace analysis [5]. The initial method design establishes the foundation for subsequent optimization through systematic experimentation.

Step 4: Risk Assessment and Experimental Planning (DoE)

A science-based risk assessment identifies variables with potential impact on method CQAs, followed by structured experimental planning. Risk assessment tools such as Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA), Ishikawa diagrams, or risk estimation matrices systematically evaluate material attributes and process parameters to identify critical factors [35]. This prioritizes experimentation on high-risk variables rather than testing all possible factors [5].

Design of Experiments (DoE) employs statistical models to optimize method conditions through multivariate studies rather than one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches [5] [35]. DoE efficiently explores the interaction effects between multiple variables simultaneously, establishing mathematical relationships between Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [35]. Common DoE approaches for method development include full factorial, fractional factorial, central composite, and Box-Behnken designs, selected based on the number of factors and desired resolution [35]. The experimental design defines the framework for method optimization and design space establishment.

Step 5: Method Optimization and Design Space Establishment

Method optimization through structured experimentation transforms initial method conditions into a robust, well-characterized analytical procedure. The optimization process systematically changes parameters individually and in combination based on the experimental design, monitoring their effect on CQAs such as resolution, peak symmetry, tailing factor, runtime, and sensitivity [36]. Modern approaches leverage automation and robotics to execute multiple experimental conditions efficiently, eliminating human error and boosting experimentation throughput [5].

The culmination of optimization is the establishment of the method design space—the multidimensional combination of input variables (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, gradient slope) proven to ensure quality as defined by CQAs [35]. The design space is derived from experimental data and mechanistic models, enabling flexible operation within regulatory-approved boundaries [35]. Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs) are established for each critical parameter, defining the boundaries within which method performance remains acceptable without requiring revalidation [35]. This represents a significant regulatory advantage, as changes within the design space do not require regulatory re-approval [35].

Step 6: Method Validation and Control Strategy

Once optimized, the method undergoes formal validation to demonstrate its suitability for intended use, followed by implementation of a control strategy. Method validation systematically assesses validation parameters including accuracy, precision, specificity, detection limit, quantification limit, linearity, range, and robustness according to ICH Q2(R1) and forthcoming ICH Q2(R2) guidelines [5] [38]. Modern validation approaches adopt a lifecycle perspective, with validation unfolding in three phases: (1) method design and feasibility, (2) qualification under stress conditions, and (3) continuous performance monitoring [5].

The control strategy encompasses planned controls to ensure consistent method performance within the design space [35]. This includes procedural controls (e.g., SOPs for system suitability testing), real-time monitoring through Process Analytical Technology (PAT), and performance trending [5] [35]. A robust control strategy ensures the method remains in a state of control throughout its lifecycle, with continuous improvement mechanisms to refine methods based on accumulated data and experience [35].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete systematic method development process:

Systematic Method Development Workflow

Advanced Approaches: AI and Machine Learning in Method Development

Artificial Intelligence for Method Optimization

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning represents a transformative advancement in systematic method development. AI algorithms optimize method parameters and predict equipment maintenance needs, while pattern recognition technologies refine data interpretation [5]. These technologies enhance method reliability by modeling complex, non-linear relationships between multiple input parameters and output CQAs that may be difficult to identify through traditional experimentation.

Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful iterative method for molecular discovery and method optimization [39]. This approach uses probabilistic models to balance exploration of unknown parameter spaces with exploitation of known promising regions, accelerating the identification of optimal method conditions [39]. In pharmaceutical applications, multifidelity Bayesian optimization (MF-BO) combines information from experiments of differing costs and fidelities, enabling more efficient resource allocation during method development [39]. For instance, lower-fidelity screening experiments (e.g., rapid gradient scouting) can be strategically combined with higher-fidelity confirmatory experiments (e.g, robust separation optimization) to build accurate predictive models with reduced experimental burden [39].

Deep Learning for Pharmaceutical Predictions

Deep learning models demonstrate superior performance for predicting pharmaceutical properties and optimizing formulation parameters, offering significant advantages over traditional machine learning approaches [40]. These models automatically extract non-linear features from complex input data, enabling accurate predictions of critical quality attributes based on molecular descriptors and formulation parameters [40].

Advanced architectures address common pharmaceutical data challenges, including small and imbalanced datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces dimensionality to improve prediction performance and training efficiency, while Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks (WGAN) overcome data limitation through synthetic data generation [40]. For instance, deep learning models with PCA have successfully predicted disintegration time of oral fast disintegrating films (OFDF), while WGAN-enhanced models have accurately predicted cumulative dissolution profiles for sustained-release matrix tablets (SRMT) [40]. These capabilities enable more efficient method development by predicting optimal conditions before laboratory experimentation.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Systematic Approaches

The performance advantages of systematic method development over traditional approaches are evident across multiple dimensions, from development efficiency to regulatory outcomes. The table below summarizes key comparative aspects:

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Systematic QbD Approach | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Philosophy | Empirical, trial-and-error [35] | Science-based, risk-managed [35] | 40% reduction in batch failures [35] |

| Experimental Design | One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) [35] | Design of Experiments (DoE) [5] [35] | Fewer experimental iterations, identification of interactions [5] |

| Parameter Understanding | Limited, based on fixed conditions [35] | Comprehensive, through design space [35] | Established Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs) [35] |