Beyond the Basics: Mastering the Beer-Lambert Law for Robust Quantitative Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of the Beer-Lambert Law in quantitative spectrophotometry.

Beyond the Basics: Mastering the Beer-Lambert Law for Robust Quantitative Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of the Beer-Lambert Law in quantitative spectrophotometry. It moves from foundational principles, explaining the law's mathematical formulation and key components like absorbance and molar absorptivity, to practical methodologies for concentration determination and calibration curves. Crucially, it addresses common limitations and deviations—such as those caused by high concentrations, scattering in biological matrices, and chemical interactions—offering troubleshooting strategies and optimization techniques. Finally, the article covers validation protocols essential for regulatory compliance and explores advanced modifications and comparative data analysis methods, including machine learning, that enhance the law's utility for complex, real-world samples like blood and tissues.

The Core Principles: Deconstructing the Beer-Lambert Law for Quantitative Analysis

In the realm of quantitative analysis research, the Beer-Lambert law serves as the foundational principle enabling scientists to determine analyte concentrations through light absorption measurements. This empirical law bridges the gap between a material's molecular properties and its interaction with electromagnetic radiation, providing researchers in drug development and analytical chemistry with powerful tools for substance quantification. At the core of the Beer-Lambert law lie two fundamental optical concepts: transmittance and absorbance. These interrelated quantities describe how light propagates through matter, with their logarithmic relationship forming the mathematical basis for most modern spectroscopic techniques. The precision of concentration measurements in pharmaceutical analysis, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics directly depends on accurately understanding and applying this conceptual framework.

Fundamental Definitions: Transmittance and Absorbance

Transmittance

Transmittance (T) quantifies the fraction of incident light that passes through a sample material. When monochromatic light with an initial intensity ((I_0)) enters a sample, and light with intensity ((I)) exits on the other side, transmittance is defined as the ratio of these two intensities [1] [2]:

[ T = \frac{I}{I_0} ]

Transmittance is a dimensionless quantity with values ranging from 0 to 1, though it is frequently expressed as a percentage (%T) ranging from 0% to 100% [1]. A transmittance of 1 (or 100%) indicates that all incident light passes through the sample without any absorption or scattering, while a transmittance of 0 (0%) signifies complete attenuation where no light emerges from the sample [3].

Absorbance

Absorbance (A) represents the logarithm of the reciprocal of transmittance, providing a quantitative measure of how much light a sample absorbs at a specific wavelength [2] [3]:

[ A = \log{10}\left(\frac{I0}{I}\right) = -\log{10}(T) = \log{10}\left(\frac{1}{T}\right) ]

Unlike transmittance, absorbance has no upper limit, though values between 0.1 and 1 are typically ideal for analytical measurements [2]. An absorbance of 0 corresponds to 100% transmittance (no absorption), while an absorbance of 1 indicates 10% transmittance (90% absorption) [1]. This logarithmic scale makes absorbance directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species, as articulated in the Beer-Lambert law.

The Logarithmic Relationship and its Mathematical Foundation

Theoretical Basis

The logarithmic relationship between transmittance and absorbance stems from the fundamental physical principle that light attenuation through a homogeneous medium occurs exponentially rather than linearly. As light traverses through infinitesimally thin layers of a sample, each layer absorbs an equal fraction of the incident radiation [4]. This multiplicative absorption process naturally leads to an exponential decay of light intensity, which linearizes through logarithmic transformation [2] [4].

The transformation from the exponential domain of transmittance to the linear domain of absorbance represents a crucial mathematical convenience for quantitative analysis. While transmittance decreases geometrically with increasing concentration or path length, absorbance increases arithmetically, establishing the direct proportional relationship essential for analytical applications [1] [2].

Quantitative Relationship Table

The table below illustrates the precise mathematical relationship between absorbance and transmittance values [1]:

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100% |

| 0.1 | 0.79 | 79% |

| 0.3 | 0.50 | 50% |

| 0.5 | 0.32 | 32% |

| 1.0 | 0.1 | 10% |

| 2.0 | 0.01 | 1% |

| 3.0 | 0.001 | 0.1% |

| 4.0 | 0.0001 | 0.01% |

Table 1: Absorbance and transmittance value relationships

This inverse logarithmic relationship demonstrates why absorbance becomes the preferred quantity in analytical applications. For instance, when 90% of light is absorbed (A=1, T=0.1), doubling the concentration of the absorbing species would result in 99% absorption (A=2, T=0.01), not 180% absorption, which would be mathematically impossible [1] [3].

Mathematical Derivation

The derivation of this relationship begins with the differential form of the attenuation law. For a thin layer of thickness (dz), the decrease in radiant flux ((d\Phi_e)) is proportional to both the incident flux and the thickness [4]:

[ \frac{d\Phie(z)}{dz} = -\mu(z)\Phie(z) ]

Solving this differential equation with the boundary condition (\Phie(0) = \Phie^i) yields [4]:

[ \Phie^t = \Phie^i \exp\left(-\int_0^\ell \mu(z)dz\right) ]

where (\Phi_e^t) represents the transmitted flux through a path length (\ell). The transmittance is therefore [4]:

[ T = \frac{\Phie^t}{\Phie^i} = \exp\left(-\int_0^\ell \mu(z)dz\right) ]

Taking the base-10 logarithm of the reciprocal establishes the connection to absorbance [2] [4]:

[ A = -\log{10}(T) = \log{10}\left(\frac{\Phie^i}{\Phie^t}\right) = \frac{1}{\ln(10)}\int0^\ell \mu(z)dz \approx 0.4343\int0^\ell \mu(z)dz ]

This derivation confirms the logarithmic relationship between transmittance and absorbance while demonstrating how absorbance linearizes the exponential attenuation process.

The Beer-Lambert Law: From Theory to Application

Fundamental Principle

The Beer-Lambert law (also known as Beer's law) establishes a direct proportional relationship between absorbance and the concentration of an absorbing species [1] [2]. For a single attenuating species in a homogeneous solution, the law is mathematically expressed as [2] [3]:

[ A = \epsilon \cdot c \cdot l ]

Where:

- (A) is the measured absorbance (dimensionless)

- (\epsilon) is the molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient (typically in L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹)

- (c) is the concentration of the absorbing species (typically in mol/L or M)

- (l) is the optical path length through the sample (typically in cm)

The molar absorptivity ((\epsilon)) is a substance-specific constant that measures how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [2] [5]. This molecular property depends on both the chemical identity of the absorber and the wavelength of incident light.

Experimental Verification Methodology

Objective: To verify the linear relationship between absorbance and concentration as predicted by the Beer-Lambert law using a series of standard solutions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Spectrophotometer with appropriate wavelength selection capability

- Matched cuvettes (typically with 1.0 cm path length)

- Analytical balance

- Volumetric flasks

- Precise pipettes

- Stock solution of analyte (e.g., Rhodamine B in water)

- Solvent for dilution (e.g., deionized water)

Procedure:

- Prepare a stock solution of known concentration (e.g., 1.0×10â»Â³ M Rhodamine B)

- Create a series of standard solutions through precise serial dilution (e.g., 2.0×10â»â´ M, 4.0×10â»â´ M, 6.0×10â»â´ M, 8.0×10â»â´ M, 1.0×10â»Â³ M)

- Set the spectrophotometer to the wavelength of maximum absorption ((\lambda_{max})) for the analyte (e.g., 550 nm for Rhodamine B)

- Measure the blank (pure solvent) and zero the instrument

- Measure the absorbance of each standard solution in sequence, ensuring proper cuvette orientation

- Record absorbance values for each concentration

Data Analysis:

- Plot absorbance versus concentration

- Perform linear regression analysis

- Determine the correlation coefficient (R²) to assess linearity

- Calculate the molar absorptivity ((\epsilon)) from the slope of the calibration curve

Expected Results: The experiment should yield a linear calibration curve similar to published results for Rhodamine B, where absorbance at (\lambda_{max}) shows direct proportionality to concentration [1]. The slope of this curve provides the product (\epsilon \cdot l), from which (\epsilon) can be calculated knowing the path length (l).

Visualizing the Beer-Lambert Law Relationship

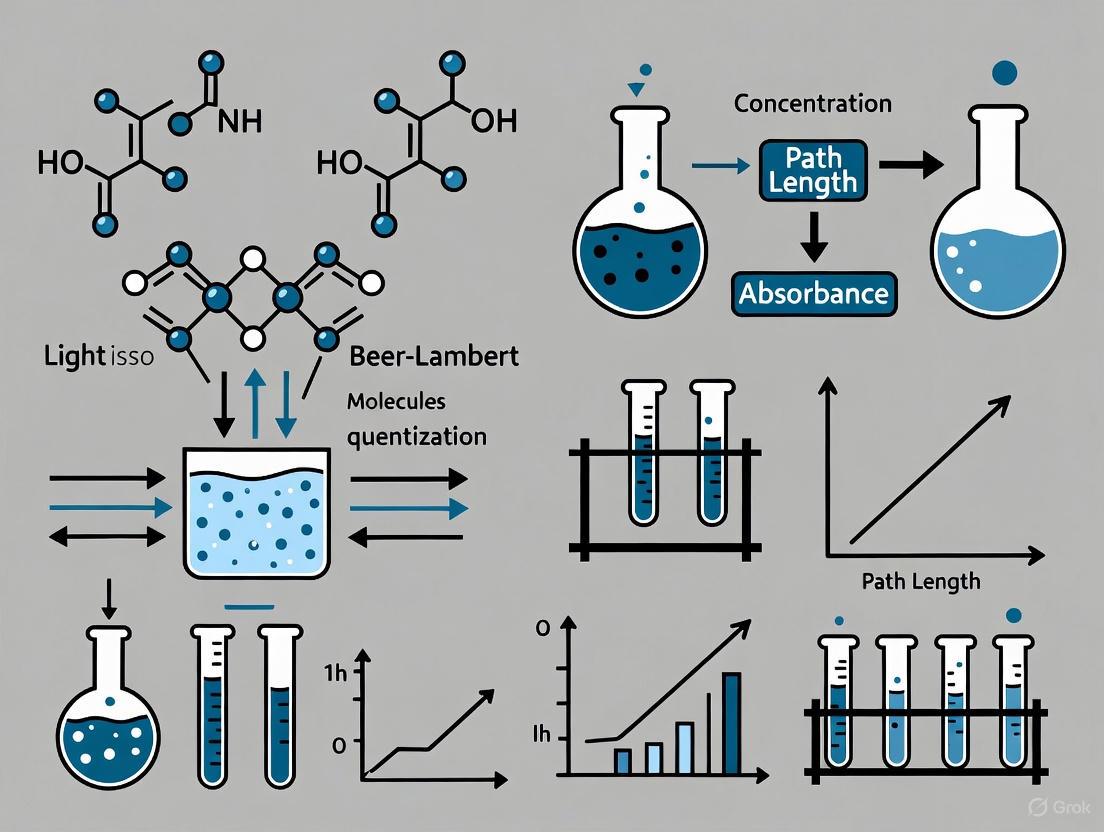

The following diagram illustrates the core principles and experimental workflow of the Beer-Lambert law:

Diagram 1: Beer-Lambert law principles and relationships

Advanced Considerations and Practical Limitations

Deviations from Beer-Lambert Law

While the Beer-Lambert law provides an excellent foundation for quantitative analysis, several factors can cause deviations from ideal linear behavior [6] [3]:

High Concentration Effects: At elevated concentrations (>0.01 M), intermolecular distances decrease, potentially altering absorptivity through molecular interactions or electrostatic effects [6] [3].

Chemical Equilibria: pH-dependent equilibria (e.g., acid-base indicators) can shift species distribution, changing effective molar absorptivity [6].

Instrumental Limitations: Stray light, polychromatic radiation, and detector non-linearity introduce measurement errors [6] [3].

Scattering Effects: Particulate matter or turbidity causes light scattering, increasing apparent absorption [3].

Fluorescence: Emitted light from fluorescent samples can reach the detector, reducing measured absorbance [6].

Multi-Component Analysis

For samples containing multiple absorbing species, the Beer-Lambert law becomes additive [6]:

[ A{total} = \epsilon1 \cdot c1 \cdot l + \epsilon2 \cdot c2 \cdot l + \cdots + \epsilonn \cdot c_n \cdot l ]

Quantifying individual components requires measuring absorbance at multiple wavelengths and solving simultaneous equations [6]:

[ \begin{aligned} A{\lambda1} &= \epsilon{1,\lambda1} \cdot c1 \cdot l + \epsilon{2,\lambda1} \cdot c2 \cdot l \ A{\lambda2} &= \epsilon{1,\lambda2} \cdot c1 \cdot l + \epsilon{2,\lambda2} \cdot c2 \cdot l \end{aligned} ]

Advanced mathematical approaches including derivative spectroscopy and multivariate calibration enable analysis of complex mixtures [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of absorption spectroscopy for quantitative analysis requires specific laboratory materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for experiments based on the Beer-Lambert law:

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Measures intensity of light before and after sample with wavelength selection capability [3] |

| Cuvettes (1 cm path length) | Contain sample solution with precise, reproducible optical path length [2] | |

| Solvents & Buffers | High-purity solvents (H₂O, CH₃OH, CHCl₃) | Dissolve analytes without contributing significant background absorption [6] |

| pH Buffer solutions | Maintain constant chemical environment to prevent shifts in absorption spectra [6] | |

| Reference Standards | Analytical standards (e.g., Rhodamine B) | Establish calibration curves with known concentrations for quantitative analysis [1] |

| Blank solutions | Contain all components except analyte to establish baseline measurements [3] | |

| Sample Preparation | Volumetric flasks | Provide accurate volume measurements for precise concentration preparation |

| Precision pipettes | Enable accurate transfer of liquid volumes for standard solution preparation | |

| Analytical balance | Allows precise weighing of solid standards for stock solution preparation |

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for absorption spectroscopy

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The logarithmic relationship between transmittance and absorbance underpins numerous critical applications in drug development:

Concentration Determination: Quantifying API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) concentration in solutions during drug formulation [5].

Purity Assessment: Detecting impurities through characteristic absorption signatures outside expected wavelengths [5].

Binding Studies: Monitoring ligand-receptor interactions through absorbance changes in titration experiments.

Dissolution Testing: Tracking drug release from formulations by measuring concentration in dissolution media over time.

Enzyme Kinetics: Following substrate depletion or product formation in enzymatic assays via absorbance changes.

The reliability of these applications fundamentally depends on properly establishing the relationship between absorbance and concentration through calibration curves, demonstrating the enduring practical significance of the transmittance-absorbance logarithmic relationship in pharmaceutical sciences.

The logarithmic relationship between transmittance and absorbance represents far more than a mathematical convenience—it forms the theoretical cornerstone for one of the most widely applied principles in analytical chemistry. By transforming the exponential nature of light attenuation into a linear relationship between absorbance and concentration, this fundamental concept enables precise quantitative analysis across diverse scientific disciplines. For drug development professionals and researchers, mastering these core principles ensures accurate implementation of spectroscopic methods, from routine quality control measurements to sophisticated research applications. As analytical technologies advance, the enduring relationship between transmittance and absorbance continues to underpin innovations in spectroscopic quantification, maintaining its central role in the scientific toolkit for quantitative analysis.

The Beer-Lambert Law (BLL), also referred to as the Beer-Lambert-Bouguer Law or simply Beer's Law, is a fundamental principle in spectroscopy that quantitatively describes the attenuation of light as it passes through a material [7]. This law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of light and the properties of the absorbing medium, making it indispensable for quantitative analysis across chemical, biological, and medical research [5]. The law's development spans over a century, beginning with Pierre Bouguer's 1729 work on light attenuation in the atmosphere, which established that light remaining in a collimated beam decreases exponentially with path length in a uniform medium [7]. Johann Heinrich Lambert later provided the mathematical formulation of this exponential relationship in 1760, while August Beer extended the law in 1852 to incorporate the concentration of solutions, completing the formulation we use today [7] [8].

In modern quantitative analysis research, particularly in pharmaceutical development, the Beer-Lambert Law serves as the cornerstone for determining analyte concentrations in solutions, monitoring chemical reactions, and ensuring product quality and consistency [5]. Its mathematical elegance and practical utility have ensured its enduring relevance across diverse scientific disciplines including analytical chemistry, biomedical engineering, environmental science, and materials characterization [9] [7]. The fundamental equation, A = εlc, provides researchers with a direct means to quantify concentrations of absorbing species through relatively straightforward absorbance measurements, making it one of the most widely applied relationships in spectroscopic analysis.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Core Equation and Component Definitions

The Beer-Lambert Law is mathematically expressed as:

A = εlc

Where:

- A is the absorbance (also called optical density), a dimensionless quantity representing the amount of light absorbed by the sample [2] [1] [5]

- ε is the molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient (in L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), a substance-specific constant that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [2] [5]

- l is the path length (in cm), representing the distance light travels through the solution, typically determined by the cuvette width [2] [5]

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (in mol/L) [2] [5]

The absorbance A is defined via the incident intensity (Iâ‚€) and transmitted intensity (I) through the logarithmic relationship:

This logarithmic relationship means that absorbance increases as transmittance decreases. The relationship between absorbance and transmittance values follows predictable patterns as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100% |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 50% |

| 1 | 0.1 | 10% |

| 2 | 0.01 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.001 | 0.1% |

Derivation and Theoretical Foundation

The Beer-Lambert Law can be derived by considering the differential attenuation of light passing through an infinitesimal layer of absorbing medium. The decrease in light intensity (-dI) across a thin layer of thickness dx is proportional to the incident intensity I, the concentration of absorbers c, and the thickness dx:

-dI/I = kcdx [10]

Where k is a proportionality constant. Integrating this differential equation from x = 0 to x = l (where I = Iâ‚€ at x = 0, and I = I at x = l) yields:

ln(Iâ‚€/I) = kcl [10]

Converting from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm gives:

logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I) = εlc [2] [10]

Where ε = k/2.303 is the molar absorptivity coefficient. This derivation establishes the fundamental exponential nature of light attenuation in absorbing media and justifies the logarithmic relationship defining absorbance [10].

Figure 1: Schematic representation of light attenuation through an absorbing medium, demonstrating the fundamental relationship described by the Beer-Lambert Law

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Quantitative Analysis

Verifying the Beer-Lambert Law and applying it for concentration determination requires meticulous experimental methodology. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for accurate spectrophotometric analysis:

Equipment and Reagents:

- High-quality spectrophotometer with wavelength selection capability [9]

- Matched quartz or optical glass cuvettes with defined path length (typically 1 cm) [5]

- Analytical balance for precise weighing [9]

- Volumetric flasks for accurate solution preparation [9]

- Pure solvent for preparing solutions [9]

- Standard reference material of known purity [9]

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform wavelength accuracy verification using holmium oxide or didymium filters with known absorption peaks [9]. Establish baseline correction with solvent-filled cuvettes to account for background absorption and reflection losses [11].

Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the analyte at known concentration, ensuring complete dissolution. Create a series of standard solutions through serial dilution, covering the expected concentration range of samples [9]. Maintain consistent temperature and chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) across all solutions to prevent chemical deviations [11].

Spectral Measurement: For each standard solution, measure absorbance at the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) determined from preliminary scans [5]. Record triplicate measurements for each concentration to assess precision. Measure blank solvent simultaneously to establish baseline.

Calibration Curve Construction: Plot average absorbance values against corresponding concentrations. Perform linear regression analysis to establish the relationship A = εlc, where the slope represents εl [1]. The correlation coefficient (R²) should exceed 0.995 for reliable quantitative work [1].

Sample Analysis: Measure unknown samples following the same procedure and determine concentration from the calibration curve [1].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Beer-Lambert Law Applications

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Measures light transmission/absorption | Wavelength accuracy ±1 nm, photometric accuracy ±0.001A [9] |

| Optical Cuvettes | Contains sample solution | Matched path length (±0.5%), transparent at measurement wavelength [5] |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and validation | Certified purity, stability in solvent [9] |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolve analytes without interference | UV-transparent if working in UV range, non-reactive with analyte [9] |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintain constant chemical environment | Appropriate pH control without absorbing at measurement wavelength [11] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The validation of Beer-Lambert Law adherence is demonstrated through the linear relationship between absorbance and concentration. As shown in Figure 3b of [1], a calibration curve for Rhodamine B solutions exhibits excellent linearity across concentration ranges typical for quantitative analysis. The molar absorptivity (ε) can be calculated from the slope of the calibration curve (ε = slope/l) and serves as a characteristic property of the analyte at specific wavelength [2] [1].

Deviations from linearity should be investigated through statistical analysis of residuals. Consistent patterns in residuals may indicate chemical interactions, instrumental artifacts, or concentrations outside the valid range for Beer-Lambert Law application [11] [9].

Figure 2: Systematic workflow for quantitative analysis using the Beer-Lambert Law, highlighting critical steps for ensuring measurement accuracy

Limitations and Deviations from Ideal Behavior

Fundamental Limitations

Despite its widespread utility, the Beer-Lambert Law operates under several simplifying assumptions that limit its applicability under non-ideal conditions. The law assumes: (1) monochromatic incident radiation; (2) non-scattering samples; (3) homogeneous distribution of absorbers; (4) low concentrations where absorber interactions are negligible; and (5) no fluorescent or photochemical processes [11] [7]. Violations of these assumptions lead to various types of deviations:

Fundamental (Real) Deviations: At high concentrations (typically >0.01M), the proximity between absorbing molecules decreases, leading to electrostatic interactions that alter absorptivity [11] [9]. The refractive index of the solution changes with concentration, affecting the light path and causing non-linearity [9]. Recent research incorporating electromagnetic theory has shown that these deviations can be modeled by extending the Beer-Lambert Law to include higher-order concentration terms:

A = (4πν/ln10) · (βc + γc² + δc³) · d [9]

Where β, γ, and δ are refractive index coefficients derived from electromagnetic principles [9].

Chemical Deviations: Chemical equilibria such as association, dissociation, polymerization, or complex formation can alter the effective concentration of absorbing species [11] [7]. Changes in pH, temperature, or solvent composition may shift these equilibria, resulting in non-linear absorbance-concentration relationships [11]. For example, acid-base indicators exhibit different absorption spectra in protonated versus deprotonated forms, leading to apparent deviations unless chemical speciation is accounted for [11].

Instrumental Deviations: The use of polychromatic light rather than truly monochromatic radiation causes deviations because ε varies with wavelength [11] [7]. Stray light reaching the detector without passing through the sample leads to inaccurate absorbance measurements, particularly at high absorbance values [11]. Improper calibration, cuvette mismatches, and detector non-linearity represent additional sources of instrumental error [11].

Table 3: Types of Deviations from Beer-Lambert Law and Mitigation Strategies

| Deviation Type | Causes | Impact on Linearity | Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental | High concentration, refractive index changes | Negative deviation at high concentrations | Sample dilution, higher-order correction models [9] |

| Chemical | Association/dissociation equilibria, solvent effects | Variable (positive or negative) | pH control, chemical buffering, low concentrations [11] |

| Scattering | Particulates, emulsions, turbid samples | Positive deviation | Sample filtration, centrifugation, refractive index matching [7] |

| Instrumental | Polychromatic light, stray light, fluorescence | Negative deviation at high absorbance | Bandwidth reduction, double-beam instruments, fluorescence filters [11] |

| Physical | Non-uniform path length, interface effects | Variable | Improved cuvette quality, controlled temperature [11] |

Interface and Interference Effects

When light encounters interfaces between different media (e.g., air-cuvette solution), reflection and refraction occur that are not accounted for in the basic Beer-Lambert formulation [11]. In thin films or samples with parallel interfaces, interference effects from forward and backward traveling waves can cause fluctuations in measured transmittance, leading to apparent deviations from predicted absorbance values [11]. These effects are particularly pronounced in infrared spectroscopy of thin films on reflective substrates, where interference fringes boldly demonstrate the limitations of the simple exponential absorption model [11].

For samples with well-defined interfaces, the relationship A = -log(T/Tâ‚€) is often used, where T is the transmittance of the sample and Tâ‚€ is the transmittance of a reference (e.g., pure solvent) [11]. This approach partially compensates for interface effects when the refractive indices of sample and reference are similar, but becomes increasingly inaccurate as the refractive index difference grows [11].

Advanced Applications in Research and Industry

Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications

The Beer-Lambert Law finds extensive application in biomedical research and drug development, particularly through modified formulations that address the unique challenges of biological matrices:

Pulse Oximetry: Modified Beer-Lambert Law forms the theoretical foundation for pulse oximeters, which noninvasively measure blood oxygen saturation [7] [12]. The modified equation accounts for the pulsatile nature of arterial blood and the strong scattering characteristics of biological tissues:

OD = -log(I/Iâ‚€) = DPF · μâ‚dᵢₒ + G [7]

Where OD is optical density, DPF is the differential pathlength factor accounting for increased photon pathlength due to scattering, μ₠is the absorption coefficient, dᵢₒ is the inter-optode distance, and G is a geometry-dependent factor [7]. By measuring absorbance at two wavelengths (typically 660 nm and 940 nm), the ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated hemoglobin can be determined despite the complex scattering environment of living tissues [7] [12].

Tissue Diagnostics: Extensions of the Beer-Lambert Law enable quantification of chromophore concentrations in living tissues, including hemoglobin, bilirubin, and cytochrome oxidase [7]. For analysis of blood, Twersky theory incorporates scattering effects from red blood cells:

OD = εcd - log(10^(-sH(1-H)d + qαq(1-10^(-sH(1-H)d))) [7]

Where H is hematocrit, s is a wavelength-dependent scattering factor, and q accounts for detection efficiency [7]. These modifications allow researchers to extract meaningful physiological information from highly scattering biological samples.

Pharmaceutical Analysis: In drug development, Beer-Lambert Law enables quantitative analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) during synthesis, purification, and formulation stages [5]. UV-Vis spectroscopy following the Beer-Lambert Law provides rapid assessment of drug concentration, purity, and stability in solution formulations [5]. The law's principles also underpin High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection, a workhorse technique for pharmaceutical analysis [5].

Multi-component Analysis and Recent Advancements

For systems containing multiple absorbing species, the Beer-Lambert Law exhibits additive properties, allowing quantification of individual components through multi-wavelength measurements [12]. The total absorbance at a given wavelength represents the sum of contributions from all absorbers:

A(λ) = Σεᵢ(λ)cᵢl [12]

Where εᵢ(λ) and cᵢ represent the molar absorptivity and concentration of the i-th component [12]. By measuring absorbance at multiple wavelengths and solving the resulting system of equations, concentrations of individual species in complex mixtures can be determined [12].

Recent research has integrated the Beer-Lambert Law with machine learning algorithms to enhance predictive accuracy in spectroscopic analysis of complex biological and environmental samples [5]. These approaches use large datasets to model non-linearities and interactions that traditional Beer-Lambert applications might overlook, improving diagnostics in medical imaging and environmental monitoring [5].

In microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip technologies, miniaturized spectrophotometric systems utilize the Beer-Lambert Law for on-chip chemical analysis [5]. These systems benefit from the law's simplicity and are being used in portable devices for point-of-care medical diagnostics and field-deployable environmental sensors [5].

Emerging electromagnetic theory-based extensions of the Beer-Lambert Law demonstrate exceptional performance in addressing fundamental deviations at high concentrations, achieving root mean square errors of less than 0.06 across various tested materials including potassium permanganate, potassium dichromate, and organic dyes [9]. These unified models incorporate effects of polarizability, electric displacement, and refractive index, providing more accurate absorption measurements across diverse fields [9].

The Beer-Lambert Law, embodied in the deceptively simple equation A = εlc, remains a cornerstone of quantitative spectroscopic analysis more than two centuries after its initial formulation. Its enduring utility stems from the robust linear relationship between absorbance and concentration that holds across diverse chemical systems when appropriate conditions are maintained. For researchers in drug development and related fields, understanding both the power and limitations of this fundamental law is essential for designing accurate analytical methods and properly interpreting spectroscopic data.

While the basic Beer-Lambert Law provides an excellent foundation for quantitative analysis, modern research continues to develop sophisticated extensions that address its limitations in complex, scattering, or high-concentration environments. From electromagnetic theory-based corrections for fundamental deviations to scattering-aware modifications for biological tissues, these advancements demonstrate the continued evolution of Bouguer, Lambert, and Beer's seminal insights. As spectroscopic technologies advance and applications expand into new domains, the core principles of the Beer-Lambert Law will undoubtedly continue to inform and enable quantitative analysis across scientific disciplines.

In the realm of quantitative chemical analysis, the Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) stands as a fundamental principle governing the interaction of light with matter. This law provides the theoretical foundation for quantitatively determining the concentration of analytes in solution, forming the basis for a vast array of spectroscopic methods used in research and industrial laboratories worldwide [2] [1]. The Beer-Lambert law establishes that the attenuation of light passing through a sample is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels through the sample [13]. The mathematical expression of this relationship is:

A = ε · c · l

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (a dimensionless quantity)

- c is the molar concentration of the analyte (mol/L)

- l is the path length of light through the sample (cm)

- ε is the molar absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) [2] [13]

While concentration and path length are experimental variables, molar absorptivity (ε) is an intrinsic molecular property that serves as a unique identifier for a substance under specific conditions—essentially acting as a "molecular fingerprint" [13]. This key parameter measures how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a given wavelength, representing the probability of an electronic transition occurring within the molecule [2]. The magnitude of ε reveals critical information about the nature of the absorbing species, with values ranging from less than 10 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ for forbidden transitions to over 100,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ for fully allowed electronic transitions [14].

Theoretical Foundations and Significance

The Physical Meaning of Molar Absorptivity

Molar absorptivity is not merely a proportionality constant in the Beer-Lambert equation; it embodies the fundamental interaction between a molecule's electronic structure and incident electromagnetic radiation. The magnitude of ε is directly related to the transition probability between electronic energy states—essentially quantifying how likely a photon of specific energy will be absorbed by a molecule [2]. This probability is governed by quantum mechanical selection rules and the Franck-Condon principle, making ε highly dependent on the molecular structure and its environment.

The value of ε provides crucial insights into the nature of the electronic transition. Low molar absorptivity values (ε < 1,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) typically indicate symmetry-forbidden or spin-forbidden transitions, whereas high values (ε > 10,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) characterize fully allowed π→π* transitions in conjugated systems [14]. This relationship makes molar absorptivity an invaluable tool for characterizing unknown compounds and verifying molecular structures in synthetic chemistry and natural product isolation.

Relationship to Molecular Structure and Electronic Transitions

The molar absorptivity of a compound is profoundly influenced by its molecular architecture. Extended conjugation in organic molecules dramatically increases ε values by creating more delocalized π-electron systems with higher transition probabilities [15]. For instance, the expansion of conjugated π-electron systems leads to both increased molar absorptivity and bathochromic shifts (shifts to longer wavelengths) in absorption maxima [15].

The presence of specific functional groups, stereochemistry, and molecular symmetry all contribute to the characteristic molar absorptivity profile of a compound. In biochemical applications, the molar absorptivity of proteins at 280 nm depends almost exclusively on the number of aromatic residues—particularly tryptophan—and can be predicted from the amino acid sequence [13]. Similarly, the molar absorptivity of nucleic acids at 260 nm can be predicted from the nucleotide sequence, enabling precise quantification in molecular biology applications [13].

Quantitative Data on Molar Absorptivity Values

Table 1: Molar Absorptivity Values for Selected Phenolic Compounds in Different Solvents

| Compound | Solvent System | Wavelength (λmax, nm) | Molar Absorptivity (ε, L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coumaric Acid (COU) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 308 | 18,900 |

| Caffeic Acid (CAF) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 322 | 16,200 |

| Ferulic Acid (FER) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 322 | 14,100 |

| Sinapic Acid (SIN) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 322 | 16,700 |

| Catechin (CAT) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 279 | 4,171 |

| Epicatechin (EC) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 279 | 4,072 |

| Procyanidin B1 | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 279 | 7,943 |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside (Q-3-glc) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 255/355 | 21,515 |

| Chlorogenic Acid | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 326 | 20,500 |

Table 2: Molar Absorptivity Values at Fixed Wavelength (280 nm) for Comparison

| Compound | Solvent System | Molar Absorptivity at 280 nm (ε, L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|

| Coumaric Acid (COU) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 12,300 |

| Caffeic Acid (CAF) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 10,700 |

| Ferulic Acid (FER) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 11,200 |

| Sinapic Acid (SIN) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 10,800 |

| Catechin (CAT) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 4,171 |

| Epicatechin (EC) | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 4,072 |

| Procyanidin B1 | Methanol/Water (50/50 v/v) | 7,943 |

The data presented in Tables 1 and 2, derived from recent research on phenolic compounds, illustrates several key aspects of molar absorptivity [15]. First, the significant variation in ε values across different compound classes highlights its specificity as a molecular fingerprint. For example, hydroxycinnamic acids like coumaric acid exhibit substantially higher molar absorptivity (ε = 18,900 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) compared to flavan-3-ols like catechin (ε = 4,171 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) due to their more extended conjugation [15].

Second, the comparison between values at λmax versus a fixed wavelength of 280 nm demonstrates the importance of measuring absorbance at the wavelength of maximum absorption for accurate quantification. The approximately 30-40% reduction in molar absorptivity for hydroxycinnamic acids when measured at 280 nm rather than their λmax underscores how suboptimal wavelength selection can significantly impact analytical sensitivity [15].

Experimental Protocols for Accurate Determination

Methodology for Molar Absorptivity Measurement

Accurate determination of molar absorptivity requires meticulous experimental technique and attention to potential error sources. The following protocol, adapted from validated methodologies, ensures precise determination of this critical parameter [15] [16]:

Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh the analyte using a calibrated analytical balance with buoyancy correction. Dissolve in the appropriate solvent to prepare a stock solution of known concentration, typically in the range of 10â»âµ to 10â»Â³ M to ensure Beer-Lambert law adherence.

Spectroscopic Measurement: Using a properly calibrated UV-Vis spectrophotometer, scan the sample solution across the relevant wavelength range (typically 200-800 nm) to identify the absorption maximum (λmax). Measure the absorbance at λmax using a minimum of three independent sample preparations.

Path Length Confirmation: Precisely determine the cuvette path length using an electronic gauge, as nominal 1 cm path lengths often deviate by >0.1% and can introduce significant error [16].

Concentration Verification: Employ orthogonal quantification methods such as quantitative NMR (q-NMR) to verify solution concentration, especially for hygroscopic or high-molecular-weight compounds where weighing errors may occur [15].

Calculation: Compute molar absorptivity using the Beer-Lambert law rearranged as ε = A/(c·l), where c is the verified molar concentration, l is the confirmed path length, and A is the measured absorbance.

Advanced Consideration: Modified Beer-Lambert Law for Complex Media

In scattering biological media like tissue, the traditional Beer-Lambert law requires modification to account for light scattering effects. The Modified Beer-Lambert Law incorporates additional parameters:

Aλ = (εHHb(λ)CHHb + εHbO2(λ)CHbO2) · d · DPF + G

Where:

- d is the physical distance between light source and detector

- DPF is the differential pathlength factor accounting for increased pathlength due to scattering

- G represents light loss due to scattering [12]

This modified relationship is particularly important in biomedical applications such as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for tissue oximetry, where accurate determination of chromophore concentrations (e.g., oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin) depends on properly accounting for scattering effects [12].

Critical Experimental Considerations and Potential Pitfalls

Table 3: Key Error Sources in Molar Absorptivity Determination and Recommended Mitigations

| Error Source | Impact on Measurement | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Path Length Uncertainty | Direct proportional error in ε; >1% error common with nominal 1 cm cells | Calibrate cells with electronic gauge; ensure proper cell alignment [16] |

| Gravimetric Errors | Systematic concentration errors from buoyancy, hygroscopicity, impurities | Use calibrated balances with buoyancy correction; verify purity with q-NMR [15] [16] |

| Reflection Losses | Increased apparent absorbance, particularly at high absorbance values | Use matched cell pairs; apply reflection correction algorithms [16] |

| Finite Slit Width | Deviation from monochromatic assumption; spectral bandwidth errors | Use spectral bandwidth <10% of natural bandwidth of absorption band [16] |

| Chemical Deviations | Non-linearity from association/dissociation or aggregation | Verify Beer-Lambert law linearity across concentration range; use dilute solutions [15] [16] |

| Stray Light | Non-linearity, particularly at high absorbance values | Regular instrument maintenance; use appropriate filters [14] |

Solvent and Environmental Effects

The molar absorptivity of a compound is not an absolute constant but varies with the physicochemical environment. Solvent polarity, pH, and temperature can significantly influence both the position of absorption maxima (λmax) and the magnitude of ε [15]. For example, phenolic compounds exhibit bathochromic shifts (red shifts) and changes in molar absorptivity in alkaline conditions due to deprotonation of hydroxyl groups [15]. Similarly, the formation of supramolecular structures at higher concentrations can lead to deviations from the Beer-Lambert law, necessitating measurement in dilute solutions where proportionality between absorbance and concentration remains linear [15].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Drug Discovery and Development Workflows

The determination of molar absorptivity plays a critical role throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial compound characterization to formulation and quality control. In early discovery, ε values enable rapid quantification of lead compounds in biological matrices during ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) studies. During preclinical development, accurate molar absorptivity values are essential for validating analytical methods in accordance with regulatory guidelines such as ICH Q2(R1) [16].

High-throughput screening platforms often rely on UV-Vis spectroscopy with previously determined molar absorptivity values to quantify compound concentrations in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) stock solutions, ensuring accurate dosing in cellular assays. The determination of molar absorptivity is particularly valuable for compounds where other quantification methods (such as evaporative light scattering detection) show poor sensitivity or reproducibility.

Case Study: Natural Product Extraction and Standardization

Recent research on Alkanna tinctoria (alkanet) root extraction demonstrates the practical application of molar absorptivity in natural product standardization [17]. Researchers compared conventional solvents with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for extracting naphthoquinone pigments (alkannin derivatives) with natural coloring and antioxidant properties. By determining the molar absorptivity of these bioactive compounds, the team could accurately quantify extraction efficiency and standardize the resulting extracts for potential use as natural food colorants and functional food ingredients [17].

This application highlights how molar absorptivity serves as a bridge between basic analytical chemistry and applied industrial processes, enabling precise quantification, quality control, and standardization of complex natural product mixtures.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Conceptual Framework of Molar Absorptivity

Experimental Determination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Accurate Molar Absorptivity Determination

| Item | Specification | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Calibration traceable to NIST standards, capacity for buoyancy correction | Precise mass determination of analyte; fundamental for accurate concentration [16] |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Validated photometric accuracy, narrow spectral bandwidth, stray light specification <0.1% | Accurate absorbance measurement across UV-Vis range; identification of λmax [16] |

| Matched Cuvettes | Precisely matched path length (<0.5% variation), material appropriate for wavelength range | Contain sample and reference solutions; defined optical path length [16] |

| Quantitative NMR Standards | High-purity internal standards (e.g., maleic acid, DMSO-d₆) | Independent concentration verification; purity assessment [15] |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Low UV cutoff, minimal fluorescent impurities | Sample dissolution; establishment of solvent baseline [15] |

| Path Length Gauge | Electronic gauge with ±0.0001 cm accuracy | Direct measurement of actual cuvette path length [16] |

| pH Buffer Systems | High-purity buffers with minimal UV absorption | Control of ionization state for pH-sensitive analytes [15] |

| Gomisin D | Gomisin D, MF:C28H34O10, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Saralasin TFA | Saralasin TFA, MF:C44H66F3N13O12, MW:1026.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Molar absorptivity stands as a cornerstone parameter in analytical spectroscopy, serving as a unique molecular fingerprint that bridges theoretical molecular structure with practical quantitative analysis. Its precise determination enables researchers across pharmaceutical development, natural products chemistry, and materials science to accurately quantify compounds in solution, standardize analytical methods, and advance scientific discovery. While the Beer-Lambert law provides the fundamental framework for understanding light-matter interactions, recognizing the limitations and potential pitfalls in molar absorptivity determination remains essential for generating high-quality, reproducible scientific data. As analytical technologies advance, the precise characterization of this fundamental molecular property will continue to play a vital role in quantitative chemical analysis and drug development research.

The Beer-Lambert law stands as a cornerstone of quantitative chemical analysis, providing the fundamental relationship between light absorption and the properties of matter. This principle is indispensable across scientific disciplines, enabling researchers to determine concentrations of analytes with precision in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring. The law, expressed as A = εlc, establishes a linear relationship where absorbance (A) depends on the molar absorptivity (ε), path length (l), and concentration (c) of the absorbing species [2] [5]. The historical development of this law represents a remarkable convergence of astronomical observation, mathematical formulation, and chemical experimentation spanning more than a century. Understanding this evolution is crucial for researchers applying this principle to modern analytical challenges, as it provides context for the law's limitations and appropriate implementation in sophisticated research environments, particularly in drug development where accurate quantification is paramount.

Historical Development and Key Contributors

The formulation of what became known as the Beer-Lambert law was not the work of a single individual but rather a cumulative scientific achievement involving multiple contributors across different disciplines and eras. The journey began with atmospheric studies, progressed through mathematical formalization, and culminated in applications to chemical solutions.

Pierre Bouguer (1729): The Astronomical Foundation

The earliest documented work leading to the absorption law comes from French mathematician and astronomer Pierre Bouguer, who published his findings in 1729 [4] [18]. Bouguer was investigating atmospheric extinction—the attenuation of starlight as it passes through Earth's atmosphere. In his seminal work "Essai d'Optique," he made a crucial discovery: light intensity decreases exponentially with the path length through the absorbing medium [4] [11]. Bouguer expressed this relationship in terms of a geometric progression, establishing that each equal thickness layer of the atmosphere absorbs an equal fraction of light that passes through it [4]. His work provided the initial conceptual framework for understanding light attenuation, though it remained specific to atmospheric contexts without explicit connection to chemical concentration.

Johann Heinrich Lambert (1760): Mathematical Formalization

German mathematician and physicist Johann Heinrich Lambert expanded upon Bouguer's findings in his 1760 work "Photometria" [4] [18]. Lambert is credited with expressing the relationship in precise mathematical form similar to its modern representation [4]. He proposed that the decrease in light intensity (dI) when passing through an infinitesimal layer of thickness (dx) is proportional to both the incident intensity (I) and the thickness itself: -dI = μIdx, where μ is the absorption coefficient [4]. By solving this differential equation, Lambert arrived at the exponential decay law: I = I₀e^(-μd) [4]. This mathematical formalization generalized Bouguer's astronomical observations into a fundamental principle of light propagation through any uniform medium, creating what became known as the Bouguer-Lambert law.

August Beer (1852): Extension to Chemical Solutions

German physicist August Beer made the crucial connection to chemistry in 1852 [4] [18]. While studying colored solutions, Beer discovered that light absorption depended not only on path length but also on the concentration of the absorbing species [4] [19]. In his seminal paper on the absorption of red light in colored liquids, Beer noted that transmittance remained constant as long as the product of the volume fraction of solute and cuvette thickness (φ·d) stayed constant [18]. Beer's work differed from his predecessors in that he explicitly accounted for reflection losses at interfaces before concluding that the absorption itself followed the exponential relationship [18]. Although Beer didn't combine his findings with Lambert's law into a single equation, he established the concentration dependence essential for quantitative chemical analysis.

Subsequent Developments and Formal Unification

The unification of these separate discoveries into the modern Beer-Lambert law occurred gradually through the late 19th and early 20th centuries:

- 1857: Bunsen and Roscoe advanced the formulation in their work on photochemical absorption [18]

- 1888: Hurter defined optical density as the natural logarithm of opacity [18]

- 1900: Luther defined the term "Extinktion" (equivalent to absorbance) [18]

- 1913: Robert Luther and Andreas Nikolopulos provided what is possibly the first modern formulation of the combined law [4] [18]

This gradual synthesis created the comprehensive relationship essential for modern spectroscopic quantification.

Table: Historical Contributors to the Beer-Lambert Law

| Contributor | Year | Key Contribution | Context of Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pierre Bouguer | 1729 | Exponential decay of light with path length | Astronomical observations of atmosphere |

| Johann Heinrich Lambert | 1760 | Mathematical formalization of absorption law | Fundamental photometry research |

| August Beer | 1852 | Concentration dependence of absorption | Colored chemical solutions |

| Bunsen & Roscoe | 1857 | Advanced formulation of absorptivity | Photochemical absorption studies |

| Luther & Nikolopulos | 1913 | Modern formulation combining all elements | Spectroscopic quantification |

Mathematical Formulation and Derivation

The modern Beer-Lambert law represents a synthesis of the historical discoveries into a precise mathematical relationship that enables quantitative analysis. The derivation proceeds from fundamental principles of light absorption.

Fundamental Differential Form

The derivation begins by considering a monochromatic light beam of intensity I passing through an infinitesimally thin layer of thickness dx within a homogeneous absorbing medium. The decrease in intensity dI is proportional to:

- The incident intensity I

- The thickness dx

- The concentration of absorbers c

This relationship can be expressed as: -dI/dx = μI = εcI [4] [19]

Where μ is the attenuation coefficient and ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient. The negative sign indicates decreasing intensity with increasing path length.

Integration to Final Form

To obtain the relationship for a finite thickness, we integrate the differential equation:

∫(dI/I) = -εc∫dx [4]

Where C is the integration constant. When x = 0 (entry point into the medium), I = Iâ‚€ (incident intensity). Thus:

C = ln(Iâ‚€) [19]

Substituting and rearranging:

ln(I/I₀) = -εcx [4]

Converting to decadic logarithms (more convenient for measurement):

logâ‚â‚€(I/Iâ‚€) = -(ε/2.303)cx [19]

Defining absorbance A = -logâ‚â‚€(I/Iâ‚€) and molar absorptivity ε = (ε/2.303):

This is the modern form of the Beer-Lambert law, where A is absorbance (dimensionless), ε is molar absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), c is concentration (mol/L), and x is path length (cm).

Equivalent Formulations

The law can be expressed in multiple equivalent forms:

- Exponential form: I = I₀e^(-μx) = I₀10^(-εcx) [4] [19]

- Transmittance form: T = I/I₀ = 10^(-A) = 10^(-εcx) [2] [1]

- Attenuation coefficient form: A = μx where μ = εc [4]

Table: Parameters in the Beer-Lambert Law

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | A | Dimensionless | Logarithmic measure of light absorbed by sample |

| Molar Absorptivity | ε | L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ | Measure of how strongly a species absorbs light at specific wavelength |

| Concentration | c | mol/L | Amount of absorbing species in solution |

| Path Length | x | cm | Distance light travels through the sample |

| Transmittance | T | Dimensionless or % | Ratio of transmitted to incident light intensity |

| Incident Intensity | Iâ‚€ | Arbitrary units | Light intensity entering the sample |

| Transmitted Intensity | I | Arbitrary units | Light intensity exiting the sample |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Implementing the Beer-Lambert law in research requires careful experimental design and execution. The following protocols ensure accurate quantitative measurements for drug development and analytical research applications.

Spectrophotometer Calibration and Operation

Equipment Preparation Protocol:

- Allow the spectrophotometer to warm up for at least 15-30 minutes to stabilize the light source and detector [20]

- Select the appropriate wavelength, typically the maximum absorbance wavelength (λmax) of the analyte [20] [5]

- Using a matched cuvette, fill with blank solution (solvent without analyte) and measure to establish 100% transmittance (A = 0) baseline [20]

- Verify instrument performance using standard reference materials if available

Critical Parameters:

- Path length consistency: Use matched cuvettes with exactly known path length (typically 1.00 cm) [2] [5]

- Stray light minimization: Ensure cuvette cleanliness and proper instrument maintenance

- Bandwidth selection: Use appropriate spectral bandwidth based on analyte and concentration

Standard Curve Generation for Quantitative Analysis

Procedure for External Calibration:

- Prepare a series of 5-8 standard solutions covering the expected concentration range of the unknown [20]

- Ensure standards bracket the unknown concentration with appropriate distribution

- Measure absorbance of each standard at the predetermined analytical wavelength

- Plot absorbance versus concentration and perform linear regression analysis [21] [20]

- Verify linearity (R² > 0.995 typically) and check that the line passes through or near the origin [20]

Quality Control Measures:

- Prepare standards in triplicate to assess precision

- Include quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations

- Monitor for deviations from linearity which may indicate chemical or instrumental issues

Sample Analysis and Data Interpretation

Unknown Sample Measurement:

- Prepare unknown samples using the same methodology as standards

- Measure absorbance under identical instrumental conditions

- Calculate concentration from standard curve: cunknown = (Aunknown - intercept)/slope [21]

- Apply dilution factors if necessary

Validation Procedures:

- Perform spike recovery experiments to verify accuracy

- Conduct replicate measurements to determine precision

- Compare results with alternative methodologies when possible

Diagram: Beer-Lambert Law Quantitative Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the Beer-Lambert law in research requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the analytical context. The following toolkit details essential components for spectroscopic quantification in pharmaceutical and biochemical research.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Quantification

| Item | Specifications | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | UV-Vis range (190-1100 nm), <±0.001 A precision, <±1 nm accuracy | Measures intensity of light before and after sample, calculates absorbance |

| Cuvettes | Matched pairs, path length 1.000 cm ± 0.5%, material appropriate for wavelength (glass, quartz, plastic) | Holds sample solution at fixed path length for reproducible measurements |

| Primary Standard | High purity (>99.9%), appropriate solubility, known molar absorptivity | Establishes calibration curve with known concentrations for quantification |

| Solvent | Spectral grade, low absorbance in analytical region, appropriate for analyte | Dissolves analyte without interfering with measurements, establishes baseline |

| Buffer Systems | Appropriate pH control, minimal absorbance, chemical compatibility with analyte | Maintains constant chemical environment, prevents pH-induced spectral shifts |

| Volumetric Glassware | Class A tolerance, appropriate capacity (pipettes, flasks) | Precise preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions |

| Reference Material | Certified absorbance standards (e.g., potassium dichromate) | Verifies spectrophotometer performance and accuracy |

| ZEN-3862 | ZEN-3862, MF:C19H17FN2O3, MW:340.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KB02-JQ1 | KB02-JQ1, MF:C38H43Cl2N7O6S, MW:796.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Limitations and Modern Challenges

Despite its fundamental importance, the Beer-Lambert law has specific limitations that researchers must recognize to avoid inaccurate quantification in critical applications such as drug development.

Fundamental Limitations and Deviations

Electromagnetic Theory Incompatibilities: The Beer-Lambert law represents an approximation that doesn't fully align with electromagnetic theory, particularly due to its neglect of wave optics effects [18] [11]. These limitations manifest as:

- Interference effects: In thin films or samples with parallel interfaces, light waves interfere constructively and destructively, causing oscillations in measured intensity that deviate from the ideal exponential decay [18] [11]

- Reflection losses: The law assumes all intensity loss results from absorption, but reflections at interfaces further reduce transmitted intensity [18]

- Optical saturation: At very high light intensities, the absorption coefficient may become intensity-dependent, violating the law's fundamental assumptions [19]

Chemical and Physical Deviations:

- High concentration effects: At elevated concentrations (>0.01M), intermolecular distances decrease, potentially altering absorptivity through molecular interactions [11] [19]

- Refractive index changes: Significant concentration-dependent changes in refractive index can invalidate the assumption of constant molar absorptivity [18] [11]

- Molecular associations: Equilibrium processes such as dimerization, aggregation, or complex formation at higher concentrations change the nature of absorbing species [11] [19]

Methodological Considerations for Accurate Application

Sample-Related Considerations:

- Microhomogeneity requirement: Samples must be homogeneous at the microscopic level; heterogeneous systems (e.g., suspensions, emulsions) cause scattering losses not accounted for in the law [11]

- Stray light effects: In samples with high absorbance (>2), stray light in the spectrophotometer becomes a significant source of error [1]

- Fluorescence interference: For fluorescent compounds, emitted light may reach the detector, artificially lowering measured absorbance [19]

Instrumental and Operational Factors:

- Polychromatic radiation deviation: Strictly requires monochromatic light; bandwidth effects cause deviations as absorptivity varies across the wavelength band [19]

- Temperature dependence: Molar absorptivity coefficients often exhibit temperature sensitivity that must be controlled in precise work [5]

Diagram: Beer-Lambert Law Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Advanced Applications and Contemporary Research

The Beer-Lambert law continues to evolve beyond its traditional applications, with contemporary research expanding its utility through technological innovations and interdisciplinary approaches.

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

Drug Development and Quality Control:

- Potency determination: Quantitative analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in formulation development [5]

- Dissolution testing: Monitoring drug release from dosage forms through continuous absorbance measurement [5]

- Biomolecular quantification: Protein, nucleic acid, and enzyme concentration measurements in biochemical assays [5]

Clinical Diagnostics:

- Pulse oximetry: Modified application for determining blood oxygen saturation through differential absorption at multiple wavelengths [5]

- Bilirubin monitoring: Quantification of bilirubin levels in neonatal blood samples [5]

- Therapeutic drug monitoring: Measuring drug concentrations in patient sera for dose optimization [5]

Technological Innovations and Methodological Advances

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques:

- Multi-wavelength analysis: Simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes through matrix-based extensions of Beer's law [5]

- Derivative spectroscopy: Application to overlapping absorption bands through differentiation techniques [5]

- Non-linear absorption spectroscopy: Extensions to high-intensity regimes where traditional assumptions break down [5]

Integration with Emerging Technologies:

- Microfluidic systems: Miniaturized spectrophotometric cells for high-throughput screening and portable analytical devices [5]

- Machine learning enhancement: Algorithms to correct for deviations and improve prediction accuracy in complex mixtures [5]

- Remote sensing applications: Atmospheric monitoring of pollutants and greenhouse gases through long-path absorption measurements [5]

The historical journey from Bouguer's atmospheric observations to Beer's chemical applications demonstrates how fundamental scientific principles evolve through interdisciplinary contributions. For today's researchers, understanding this context provides not just theoretical background but practical insight into both the power and limitations of this essential quantification tool. As spectroscopic technologies advance, the core principles established by these pioneers continue to enable precise quantitative analysis across the spectrum of scientific inquiry, particularly in pharmaceutical development where accurate concentration measurement remains indispensable to research and quality assurance.

The Beer-Lambert Law (BLL), often referred to as Beer's Law, represents a cornerstone of quantitative absorption spectroscopy, forming the foundational principle for analytical techniques across chemical, pharmaceutical, and biological disciplines [4] [2]. This empirical relationship describes the attenuation of light as it passes through a homogeneous medium, providing the theoretical basis for determining analyte concentration through optical measurements [1] [20]. In its common form, the law states that absorbance (A) is proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species (c), the path length of light through the medium (l), and the species' molar absorptivity (ε), expressed as A = εlc [2] [20].

Within quantitative analysis research, particularly in drug development, understanding the precise boundaries of this relationship is not merely academic—it is fundamental to analytical accuracy. The Beer-Lambert law functions as an idealized model, and its correct application hinges on satisfying specific physicochemical and instrumental conditions [11] [18]. This guide details these critical assumptions, provides methodologies for their validation, and outlines the consequences of their violation, thereby enabling researchers to generate reliable, reproducible quantitative data.

Fundamental Mathematical Formulation and Historical Context

The Beer-Lambert law finds its origins in the 18th century with the work of Pierre Bouguer, who established that light intensity decays exponentially as it travels through an absorbing medium [4] [18]. Johann Heinrich Lambert later formalized this mathematical relationship, while August Beer, in the mid-19th century, demonstrated the proportionality of absorption to the concentration of the solute in a solution [4] [18]. The modern, merged form of the law was first presented by Robert Luther and Andreas Nikolopulos in 1913 [4].

The derivation begins with the differential form of the law. For a collimated beam of monochromatic light with intensity I traversing an infinitesimal thickness dz of a homogeneous medium, the decrease in intensity -dI is proportional to the incident intensity I, the thickness dz, and the concentration of absorbers c, leading to the differential equation: -dI = μ I dz, where μ is the attenuation coefficient [4]. Integration over a finite path length l yields the integral form of the law.

Table 1: Equivalent Formulations of the Beer-Lambert Law

| Formulation | Equation | Variable Definitions | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decadic (Chemist's) Form | ( A = \log{10}\left(\frac{I0}{I}\right) = \epsilon l c ) | ( A ): Absorbance ( I_0 ): Incident Intensity ( I ): Transmitted Intensity ( \epsilon ): Molar Absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) ( l ): Path Length (cm) ( c ): Concentration (mol·Lâ»Â¹) | Analytical Chemistry, Solution Spectroscopy [1] [2] |

| Napierian (Physicist's) Form | ( \tau = \ln\left(\frac{I_0}{I}\right) = \sigma l n ) | ( \tau ): Optical Depth ( \sigma ): Absorption Cross-Section (cm²) ( n ): Number Density (molecules·cmâ»Â³) | Atmospheric Physics, Astrophysics [4] |

| Additive Absorbance Form | ( A{total} = l \sumi \epsiloni ci ) | ( \epsiloni ): Molar Absorptivity of species *i* ( ci ): Concentration of species i | Multi-component Mixture Analysis [4] |

For a single analyte in a homogeneous solution, the relationship between transmittance and absorbance is logarithmic. The transmittance ( T = I / I0 ) is related to absorbance by ( A = -\log{10} T ) [1]. This is visualized in the following workflow, which outlines the core logical relationship of the BLL from its fundamental principle to its final application for concentration determination.

Core Assumptions and Their Limitations

The Beer-Lambert law is an idealization, and its strict linear relationship between absorbance and concentration holds only under a specific set of conditions. Deviations from these assumptions lead to non-linearity and analytical inaccuracies [11] [18]. The following table systematically outlines these critical assumptions, their theoretical basis, and the consequences of their violation.

Table 2: Core Assumptions of the Beer-Lambert Law and Implications of Violations

| Assumption | Theoretical Basis | Consequences of Violation | Typical Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic Light | ε is a function of wavelength (λ). Using polychromatic light where ε varies across the bandwidth leads to an averaged, non-linear response [11] [20]. | Negative deviation from linearity; calibration curves curve downward at high absorbances. | Applicable at all concentrations, effect worsens with A. |

| Absorbing Species Act Independently | Absorbances are additive; no chemical interactions (e.g., association, dissociation, complexation) between molecules that alter their absorption spectrum [4] [22]. | Non-additivity of absorbances; predicted vs. measured values diverge. | Highly dependent on chemical system. |

| Uniform Path Length & Homogeneity | The law assumes a perfectly collimated beam through a homogenous, scatter-free medium with constant path length l [4] [11]. | Scattering losses measured as false absorption; path length is ill-defined. | Applicable at all concentrations. |

| Linearity up to ~0.01 M | At high concentrations, the average distance between molecules decreases, altering their electrostatic environment (e.g., via refractive index changes) and affecting their absorptivity [11] [18]. | Negative deviation from linearity; calibration curve flattens. | Typically < 0.01 M; varies by analyte. |

| No Scattering or Reflection Losses | The model considers only absorption. Scattering and reflection at cuvette interfaces reduce transmitted intensity I [4] [11]. | Positive deviation; measured absorbance is higher than true absorption. | Applicable at all concentrations. |

| Strictly Absorbing Solutes in Non-Absorbing Solvents | The solvent is assumed to be perfectly transparent at the analytical wavelength and not to interact with the solute in a way that changes ε [11]. | Spectral shifts and changes in ε; inaccurate quantification. | Dependent on solute-solvent interactions. |

A critical, often overlooked limitation stems from the wave nature of light. The BBL law is a macroscopic, phenomenological relationship that does not fully account for electromagnetic effects. In samples with well-defined parallel interfaces (e.g., thin films on IR-transparent substrates like ZnSe or Si), light behaves as a wave, leading to interference through the constructive and destructive interaction of forward and backward traveling waves [11] [18]. This results in intensity fluctuations (fringes) and band-shape distortions that are not related to chemical changes but purely to optical conditions [11]. These effects are pronounced in infrared (IR) spectroscopy of thin films and make quantitative interpretation without wave-optics-based corrections difficult [11].

Experimental Validation and Protocol Design

Validating the adherence of an analytical method to the Beer-Lambert law is a prerequisite for accurate quantitative work. The following section provides a detailed protocol for establishing a reliable calibration model.

Reagent and Instrument Preparation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Specification / Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Standard | High-purity reference material for preparing stock and working standard solutions. | Purity must be certified; hygroscopic materials require special handling. |

| Spectrophotometric Solvent | A solvent that is transparent at the analytical wavelength and does not chemically interact with the analyte. | Must have a refractive index close to that of the final sample solution to minimize interface effects [11]. |

| Volumetric Glassware | Class A volumetric flasks and pipettes for accurate and precise dilution and volume measurement. | Calibration errors are a primary source of uncertainty in standard curve preparation. |

| Spectrophotometer Cuvettes | Matched cuvettes with a defined path length (typically 1.00 cm); material must be transparent to the wavelength range (e.g., quartz for UV, glass/plastic for VIS). | Path length must be consistent; scratches or residues on windows cause scattering [1]. |

| Double-Beam Spectrophotometer | Instrument capable of measuring absorbance at a specific wavelength with low stray light and high photometric accuracy. | The use of a double-beam instrument compensates for source drift. The blank is used to set 0%T and 100%T [20]. |

Core Validation Protocol: Linearity and Additivity

Experiment 1: Verification of Linearity and Determination of Linear Dynamic Range

- Stock Solution Preparation: Accurately prepare a stock solution of the analyte at a concentration believed to be near the upper limit of the expected linear range.

- Dilution Series: Perform a serial dilution (e.g., 5-8 levels) to create standard solutions covering a range of concentrations. Ensure all dilutions are performed quantitatively with volumetric glassware.

- Spectrophotometric Measurement: Using a stable, thermostatted spectrophotometer, measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the predetermined wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax). The λmax is identified by recording an absorption spectrum of a mid-range standard [20].

- Blank Measurement: A blank containing only the solvent must be measured and used to zero the instrument before reading the standards [20].

- Data Analysis & Linearity Assessment: Plot the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the corresponding concentration (x-axis). Perform linear regression analysis. The correlation coefficient (R²) should be >0.995. The linear dynamic range is defined by the concentration interval over which the curve remains linear and passes through the origin [1] [20].

Experiment 2: Verification of Absorbance Additivity

This test is crucial for validating the assumption of independent absorbers, which is especially important in multi-analyte formulations or in the presence of matrix interferents [22].

- Prepare Individual Solutions: Prepare separate solutions of two different analytes (e.g., a yellow and a blue dye, #1 and #4 from the reference) at known concentrations in the same solvent [22].

- Measure Individual Absorbances: Measure the absorbance of each individual solution at a chosen wavelength (λ).

- Prepare and Measure a Mixture: Create a mixture containing known volumes of the two individual solutions. Measure the absorbance of this mixture at the same wavelength (λ).

- Calculate Predicted Absorbance: The predicted absorbance of the mixture, A_pred, is calculated based on the dilution of each component:

- Apred = (VA / Vtotal) * AA + (VB / Vtotal) * AB where VA and VB are the volumes of the individual solutions, Vtotal is the total volume of the mixture, and AA and AB are the measured absorbances of the individual solutions [22].

- Compare Results: Compare the measured absorbance of the mixture to the predicted value. Agreement within experimental error validates the additivity assumption for that specific pair of analytes at the chosen wavelength. A significant discrepancy suggests a chemical interaction or other interference [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for this additivity experiment, helping to diagnose potential issues when the law appears to fail.

Advanced Considerations for Quantitative Research

For researchers engaged in high-precision analysis, such as in drug development, moving beyond basic validation is necessary. Key advanced considerations include:

The Solvent Environment and Molar Absorptivity: The molar absorptivity (ε) is not a universal constant. It depends on the solvent environment because light interacts with and polarizes matter. A dye molecule in different solvents (even without chemical interaction) can exhibit different colors and thus different ε values due to changes in polarizability [11]. This necessitates that calibration curves be prepared in the same solvent and matrix as the unknown samples.