Comparative Analysis of SPE Cartridges for Complex Matrices: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

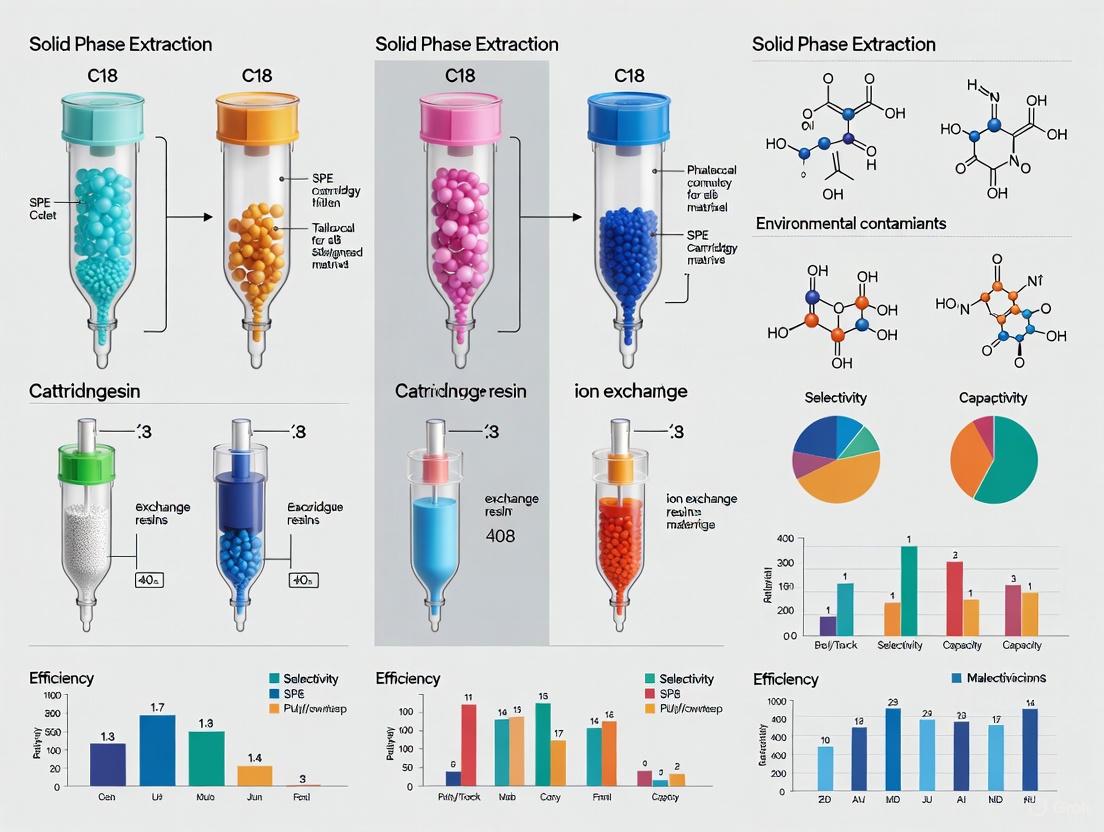

This article provides a comprehensive, application-focused guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) cartridges for diverse sample matrices.

Comparative Analysis of SPE Cartridges for Complex Matrices: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, application-focused guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) cartridges for diverse sample matrices. It covers foundational principles of SPE mechanisms and sorbent chemistry, details method development for biological, environmental, and food safety applications, and offers advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls like low recovery and matrix effects. The guide culminates in a rigorous comparative analysis of leading SPE products and validation strategies to ensure regulatory compliance, data integrity, and robust analytical performance in method development.

SPE Cartridge Fundamentals: Mechanisms, Sorbents, and Selection Criteria

Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) is a fundamental sample preparation technique that enables researchers to isolate, purify, and concentrate analytes from complex matrices. By understanding its core principles and workflow, scientists can select the optimal SPE approach for their specific application, significantly enhancing the accuracy and sensitivity of subsequent analyses like Liquid Chromatography (LC) or Mass Spectrometry (MS) [1] [2].

Core Retention Mechanisms in SPE

The separation power of SPE stems from exploiting specific chemical interactions between the analyte, the sorbent (stationary phase), and the solvents (mobile phase). The two principal mechanisms are polarity and ion exchange, which can be used independently or in combination [1].

Polarity-Based Mechanisms

Polarity-driven separations operate on the principle of "like dissolves like." The choice between normal-phase and reversed-phase mode depends on the relative polarities of the analyte and the sorbent [1].

- Reversed-Phase SPE: This is the most common mode. It uses a nonpolar sorbent (e.g., C18 or C8 bonded silica) and a polar mobile phase (e.g., water or buffers). It retains nonpolar analytes from polar sample matrices, such as organic contaminants in water [1].

- Normal-Phase SPE: This mode uses a polar sorbent (e.g., bare silica, alumina, or Florisil) and a nonpolar mobile phase (e.g., hexane or chloroform). It is ideal for isolating polar analytes from nonpolar sample matrices [1].

Ion Exchange Mechanisms

Ion exchange relies on electrostatic attractions, governed by the rule that "opposites attract." This mechanism is highly effective for analytes that are permanently charged or can be charged by adjusting the sample pH [1].

- Strong Ion Exchange: These sorbents have a permanent charge (e.g., quaternary ammonium for Strong Anion Exchange (SAX) or sulfonic acid for Strong Cation Exchange (SCX)).

- Weak Ion Exchange: These sorbents have a charge that depends on pH (e.g., amino groups for Weak Anion Exchange (WAX) or carboxylic acid for Weak Cation Exchange (WCX)).

A key strategic consideration is to pair a weak ion-exchange sorbent with a strong ionic analyte and a strong ion-exchange sorbent with a weak ionic analyte. This ensures sufficient retention while allowing for efficient elution later without needing extremely strong conditions [1].

The table below summarizes the primary retention mechanisms.

Table 1: Primary SPE Retention Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Sorbent Type | Analyte Property | Typical Sorbent Examples | Elution Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase | Nonpolar | Nonpolar | C18, C8, Phenyl, Polymerics | Less polar (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) |

| Normal-Phase | Polar | Polar | Silica, Diol, Florisil, Alumina | More polar (e.g., Methanol with water) |

| Cation Exchange | Negatively charged | Positively charged | SCX, WCX | High ionic strength, pH to neutralize charge |

| Anion Exchange | Positively charged | Negatively charged | SAX, WAX | High ionic strength, pH to neutralize charge |

The Standard SPE Workflow

A typical SPE procedure involves passing a liquid sample through a cartridge or disk containing the sorbent. The following sequence graph outlines the core steps, from conditioning to analyte elution.

Figure 1: The Four-Step Solid Phase Extraction Workflow.

- Conditioning: The sorbent bed is prepared by passing a solvent to solvate the functional groups and create a conducive environment for analyte retention. A reversed-phase C18 sorbent, for instance, is conditioned with methanol followed by water or buffer to prevent the sample from passing through without interaction [1] [2].

- Sample Loading: The prepared sample is passed through the cartridge. Target analytes are retained on the sorbent based on the selected mechanism (e.g., polarity, ion exchange), while unretained matrix components flow through to waste [2].

- Washing: A solvent of intermediate strength is used to remove undesired matrix components that are weakly bound to the sorbent without displacing the analytes of interest. This step is crucial for reducing background interference [1].

- Elution: The final step uses a small volume of a strong solvent to disrupt the analyte-sorbent interaction, thereby releasing the purified and concentrated analytes for collection. The elution solvent is chosen to be compatible with the subsequent analytical instrument [1] [2].

Comparative Analysis of SPE Formats and Sorbents

The performance of SPE can vary significantly based on the physical format of the device and the chemistry of the sorbent. Below is a comparison of common SPE configurations and a data-driven comparison of sorbent performances.

Table 2: Comparison of Common SPE Configurations

| Parameter | Cartridge | Disk | Pipette-Tip (PT-SPE) | Monolithic (m-SPE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorbent Weight | 4–30 mg [2] | 4–200 mg [2] | 4–400 µg [2] | Varies (single porous polymer) [3] |

| Sample Volume | 500 µL–50 mL [2] | Up to 1 L [2] | 0.5–1 mL [2] | Compatible with low volumes [3] |

| Key Benefits | Easy to use, wide range of sorbents, low cost [2] | Fast flow rates, good for large volumes, minimized channeling [2] | Very small elution volume, amenable to automation, no conditioning needed [2] | High permeability, low backpressure, robust porosity, enhanced reproducibility [3] |

| Primary Limitations | Slow flow rate, potential for channeling, plugging [2] | Can be costly, potential for decreased breakthrough volume [2] | Limited sorbent capacity, not suitable for large samples [2] | Material and application-specific limitations exist [3] |

A 2025 study provides a direct performance comparison between particle-packed SPE (p-SPE) and monolithic SPE (m-SPE) for the selective separation of trace lead (Pb) from aqueous matrices. Both columns used the same crown ether-based sorbent (AnaLig Pb-02) but in different physical forms [3].

Table 3: Experimental Comparison of p-SPE vs. m-SPE for Lead Separation

| Performance Metric | Particle-Based (p-SPE) | Monolithic (m-SPE) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability & Backpressure | Lower permeability, higher backpressure | High permeability, low backpressure [3] | Optimized flow rates for aqueous samples [3] |

| Structural Advantage | Packed bed of particles | Single, porous polymer structure with interconnected pores [3] | – |

| Overall Efficiency | Satisfactory Pb²⺠retention [3] | Enhanced selectivity, reproducibility, and efficiency [3] | Analysis of certified reference river water (NMIJ CRM 7202-c) [3] |

| Key Outcome | Effective for Pb separation | Enhanced performance for preferential separation of trace Pb from complex matrices [3] | Both columns were reusable over multiple cycles [3] |

Experimental Protocol: SPE for Dye Detection in Food

A 2025 study optimized an SPE method for detecting safranin T (SA) and rhodamine B (RhB) dyes in kids' candies using UHPLC-FLD [4].

- SPE Sorbent: Supel-Select HLB (a hydrophilic-lipophilic balanced polymer).

- Sample Prep: 2.0 g of candy was dissolved in water, centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded.

- SPE Procedure: The cartridge was conditioned with methanol and water. After loading, it was washed with 5% methanol and dried. Analytes were eluted with 2 mL of methanol.

- Results: The method showed high recovery (89.11–95.88%) and sensitivity, with limits of detection at 0.104 ng/mL for SA and 0.139 ng/mL for RhB [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right materials is critical for successful SPE method development. The following table details key reagents and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for SPE

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HLB Sorbent | Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balanced copolymer for broad-spectrum retention of acidic, basic, and neutral compounds [5]. | Extracting a wide range of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and dyes from water or food samples [4] [5]. |

| Ion Exchange Sorbents (WAX, WCX, MCX) | Selectively retain charged analytes via electrostatic interactions. WAX/WCX are weak exchangers; MCX is a mixed-mode cation exchanger [5]. | Isolating polar cations (e.g., specific antibiotics) using MCX [5] or anions using WAX. |

| C18 Sorbent | A reversed-phase sorbent with C18 (octadecyl) chains bonded to silica; highly nonpolar for retaining hydrophobic analytes [1]. | Classic reversed-phase extraction of non-polar to moderately polar compounds. |

| Monolithic Sorbent | A single, porous polymer structure (e.g., methacrylate) offering high flow rates and low backpressure [3]. | High-throughput applications and separation of trace metals from complex environmental matrices [3]. |

| AnaLig Pb-02 | A specialized sorbent functionalized with a crown ether for molecular recognition of specific ions like Pb²⺠[3]. | Selective separation and preconcentration of trace lead (Pb) from water [3]. |

| Ihmt-trk-284 | Ihmt-trk-284, MF:C25H27N7OS, MW:473.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antileishmanial agent-8 | Antileishmanial agent-8, MF:C18H16O4, MW:296.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Strategic Sorbent Selection for Comprehensive Analysis

The choice of sorbent profoundly impacts the chemical space covered in an analysis. A recent study evaluating SPE for non-targeted analysis of environmental water provides critical insights [5].

- HLB Sorbent Alone: Captures a broad range of chemical space and is a cost-effective, simple starting point for many applications. It alone detected 1,378 chemical features in surface water [5].

- Combined Sorbent Phases (e.g., HLB-WAX-MCX): Using mixed sorbents or phases increases the coverage of diverse chemistries. The HLB-WAX-MCX combination retained 222 out of 231 diverse surrogate chemicals, showing superior coverage, particularly for polar cations with the MCX sorbent [5].

The diagram below illustrates this strategic selection process based on analyte and matrix properties.

Figure 2: A Strategic Guide for Selecting SPE Sorbent Chemistry.

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is a fundamental sample preparation technique in modern analytical laboratories, enabling the concentration, purification, and enrichment of target analytes from complex matrices. The core of SPE technology resides in the sorbent material, which dictates the selectivity and efficiency of the extraction process. The choice of sorbent chemistry is paramount, as it must be compatible with the physicochemical properties of the target analytes and the sample matrix. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the four principal sorbent chemistries—reversed-phase, normal-phase, ion exchange, and mixed-mode—framed within ongoing research on SPE cartridge performance for different matrices. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article synthesizes current experimental data and methodologies to inform strategic sorbent selection.

Sorbent Chemistry Classifications and Mechanisms

SPE sorbents are classified based on their primary interaction mechanisms with analytes. The following sections detail the fundamental principles, characteristic sorbents, and ideal applications for each class. A comparative summary is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major SPE Sorbent Chemistries

| Sorbent Type | Retention Mechanism | Representative Sorbents | Typical Analyte Properties | Common Eluents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase | Hydrophobic interactions | C18, C8, Phenyl, C4 [6] | Non-polar or moderately polar | Acetonitrile, Methanol [6] |

| Normal-Phase | Polar interactions (dipole-dipole, H-bonding) | Silica, Aminopropyl (NHâ‚‚), Cyano (CN), Diol [6] | Polar | Hexane, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate [6] |

| Ion Exchange | Electrostatic attraction | SAX (Strong Anion), SCX (Strong Cation), WAX, WCX [6] | Ionic (acids, bases) | Buffer with competing ion/pH shift [6] |

| Mixed-Mode | Hydrophobic + Ionic | MCX (Cation), MAX (Anion) [6]; Zwitterionic [7] | Ionic with hydrophobic regions | Sequential: organic solvent then ionic eluent [7] |

Reversed-Phase SPE

Reversed-phase (RP) SPE is the most widely used mechanism, relying on hydrophobic interactions between a non-polar sorbent and non-polar or moderately polar regions of the analyte. Retention is favored in polar (aqueous) sample matrices, while elution is achieved with organic solvents. The workhorse sorbents in this category are C18 (octadecyl) and C8 (octyl) bonded silica, which provide a hydrophobic surface for retaining non-polar compounds [6]. Other variants like phenyl or cyanopropyl phases offer different selectivity for specific applications.

Normal-Phase SPE

In contrast, normal-phase (NP) SPE utilizes polar interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions, between a polar sorbent and polar analytes. Retention is strongest from non-polar solvents. Silica, with its active silanol groups, is a classic normal-phase sorbent [6]. Other functionalized sorbents like aminopropyl (NHâ‚‚), cyano (CN), and diol phases provide different polar interaction strengths and selectivities, making them suitable for isolating polar compounds like pigments, saccharides, or pharmaceuticals from non-polar interferences.

Ion Exchange SPE

Ion exchange (IE) SPE separates ionic compounds through electrostatic attraction between charged functional groups on the sorbent and oppositely charged analytes. Cation exchangers, such as Strong Cation Exchange (SCX), contain negatively charged groups (e.g., sulfonate) to capture basic compounds. Anion exchangers, such as Strong Anion Exchange (SAX), contain positively charged groups (e.g., quaternary ammonium) to capture acidic compounds [6]. The retention is highly dependent on the sample pH, which controls the ionization state of both the analyte and the sorbent. Elution is typically performed using a buffer with a high ionic strength or a pH that neutralizes the charge of either the analyte or the sorbent.

Mixed-Mode SPE

Mixed-mode sorbents combine two or more orthogonal retention mechanisms within a single cartridge, most commonly reversed-phase and ion exchange. This design allows for highly selective purification of analytes that possess both ionic and hydrophobic character, such as many pharmaceutical drugs. Sorbents like MCX (mixed-mode cation exchange) and MAX (mixed-mode anion exchange) are commercially available and widely used [6]. A recent advancement is the development of novel silica-based zwitterionic mixed-mode sorbents, which are functionalized with both quaternary amine and sulfonic groups alongside C18 chains, enabling simultaneous hydrophobic, strong cationic exchange (SCX), and strong anionic exchange (SAX) interactions [7]. The cleanup process typically involves a wash step to remove interferences retained by only one mechanism, followed by a selective elution for the target analytes.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Monolithic vs. Particle-Based Architectures

Beyond sorbent chemistry, the physical architecture of the SPE column significantly impacts performance. A 2026 study directly compared a monolithic SPE (m-SPE) column with a conventional particle-packed SPE (p-SPE) column, both functionalized with the same supramolecule (crown ether) for selective lead (Pb) separation. The m-SPE column demonstrated enhanced performance due to its high permeability, low backpressure, and robust porosity, which resulted in better selectivity, reproducibility, and overall efficiency [3]. This highlights how material engineering complements sorbent chemistry to improve throughput.

Case Study: Mixed-Mode Sorbents for Basic Drugs

Research on four novel mixed-mode zwitterionic sorbents provides a clear example of performance optimization. In a study to determine drugs in environmental water samples, all sorbents initially retained both acidic and basic compounds. However, after optimizing the SPE protocol with a clean-up step, the sorbent identified as SiO2-SAX/SCX enabled the selective retention of basic compounds through ionic exchange interactions [7]. The validated method using this sorbent achieved apparent recoveries of 40-85% for basic drugs in spiked river water samples, with minimal matrix effects ranging from -17 to -4%, demonstrating high selectivity in a complex matrix [7].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Recent Sorbent Studies

| Study Focus | Sorbent Type | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Pb Separation [3] | Crown Ether-based (m-SPE vs p-SPE) | Lead (Pb²âº) | General Performance | m-SPE showed enhanced efficiency, selectivity, and reproducibility over p-SPE |

| Drugs in River Water [7] | Zwitterionic Mixed-Mode (SiO2-SAX/SCX) | Basic Drugs | Apparent Recovery | 40% to 85% |

| Matrix Effect | -17% to -4% | |||

| Ciguatoxin Cleanup [8] | Polystyrene-divinylbenzene vs. Silica | CTX1B & CTX3C Toxins | Chromatographic Efficiency | >79% |

| Toxicity Recovery | >53% |

Application in Toxin Analysis

The effectiveness of different sorbent chemistries is matrix-dependent. A 2025 study comparing six SPE cleanup strategies for ciguatoxins (CTXs) in fish tissue found that protocols using polystyrene-divinylbenzene (reversed-phase) and silica (normal-phase) cartridges were the most versatile [8]. These methods achieved chromatographic efficiencies over 79% and recovered over 53% of the toxin's toxicity, proving superior for the purification of these complex marine toxins from a challenging lipid-rich matrix [8].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General SPE Procedure

A standardized protocol is applicable to most SPE cartridges, with the specific solvents and conditions tailored to the sorbent chemistry and analytical goals. The following workflow diagram outlines the universal steps.

General SPE Workflow

Detailed Methodologies from Cited Research

- Sorbent: Supramolecule-equipped (crown ether) monolithic (m-SPE) or particle-packed (p-SPE) columns.

- Optimization Parameters: Key operational parameters, including solution pH, flow rate, washing solvent, and eluent composition, were systematically optimized to maximize Pb²⺠retention. The presence of counter anions was found to enhance retention on the m-SPE column.

- Interference Test: Potential interference from common matrix ions (e.g., Li, Na, Mg, K, Ca, Sr, Ba, Fe) was investigated using certified reference river water (NMIJ CRM 7202-c).

- Analysis: Eluates were analyzed via Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Sorbent: Novel silica-based zwitterionic sorbents with C18, quaternary amine, and sulfonic groups.

- Sample: Environmental water samples (100 mL river water, 50 mL effluent wastewater).

- SPE Optimization: A clean-up step was introduced to promote the selective retention of basic compounds via ionic exchange, suppressing the retention of acidic interferents.

- Analysis: Extracts were analyzed using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Method validation included appraisal of apparent recoveries, matrix effect, linearity, and limits of detection and quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents commonly used in SPE experiments, as evidenced by the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SPE Research

| Item | Function / Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SPE Cartridges | Core platform for extraction; choice defines mechanism. | C18, SCX, MCX, Mixed-mode Zwitterionic [6] [7] |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Method validation and ensuring accuracy in complex matrices. | NMIJ CRM 7202-c (river water) [3] |

| Buffer Solutions | Control sample pH, critical for ionization and retention in IE and Mixed-mode. | Acetate (pH 3-5), MES (pH 6), HEPES (pH 7-8), TAPS (pH 9-10) [3] |

| Eluents | Displace and recover analytes from the sorbent. | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Ethyl Acetate, EDTA solution [3] [8] |

| Internal Standards | Correct for variability in sample preparation and analysis. | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of target analytes. |

| Vacuum Manifold | Process multiple samples simultaneously by controlling flow. | Multi-port SPE vacuum manifold [3] |

| Glutaminyl Cyclase Inhibitor 5 | Glutaminyl Cyclase Inhibitor 5 | Explore Glutaminyl Cyclase Inhibitor 5, a potent small-molecule for Alzheimer's disease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Disodium succinate-13C2 | Disodium succinate-13C2, MF:C4H4Na2O4, MW:164.04 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that there is no single "best" sorbent chemistry. The optimal choice is a strategic decision based on the analyte's hydrophobicity, polarity, and ionic character, as well as the complexity of the sample matrix. Reversed-phase sorbents remain the versatile default for non-polar analytes, while ion exchange and mixed-mode sorbents offer superior selectivity for ionic compounds, especially in complex biological or environmental samples. The ongoing development of novel materials, such as zwitterionic mixed-mode sorbents and monolithic architectures, continues to push the boundaries of SPE performance, offering researchers enhanced efficiency, selectivity, and robustness for their analytical challenges.

The effectiveness of any analytical method is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the sample preparation step, where the choice of sorbent material plays a pivotal role. Recent advancements have moved beyond conventional phases to a new generation of advanced and hybrid sorbents engineered for superior performance. These materials, including tailored polymer-based phases, highly selective Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), and versatile graphene-based sorbents, offer enhanced capabilities for isolating target analytes from complex matrices. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these sorbent classes, evaluating their performance, experimental applications, and suitability for different sample types such as biological, environmental, and food matrices. By integrating supporting experimental data and detailed protocols, this review serves as a strategic resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize their solid-phase extraction (SPE) workflows.

Sorbents function as the heart of solid-phase extraction, mediating the selective interaction and retention of target compounds from a sample mixture. Their performance is governed by key characteristics including surface chemistry, pore structure, specific surface area, and the nature of functional groups. Conventional sorbents like C18 (reversed-phase) and silica (normal-phase) operate primarily through hydrophobic or polar interactions, respectively. While effective for many applications, their lack of specificity can be a limitation in complex matrices.

Advanced sorbent materials have been developed to overcome these limitations. Polymer-based phases, such as hydrophilic-lipophilic balanced (HLB) polymers, provide a mixed-mode interaction capability, making them suitable for a broad spectrum of analytes of varying polarity. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic polymers containing tailor-made recognition sites that are complementary to a specific target molecule in shape, size, and functional groups, conferring antibody-like specificity [9] [10]. Graphene-based materials, including graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO), offer an exceptionally high surface area and a unique structure that allows for multiple interaction mechanisms (e.g., π-π, electrostatic, hydrophobic) [11].

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the core sorbent classes discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Core Sorbent Classes for Solid-Phase Extraction

| Sorbent Class | Primary Interactions | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Exemplary Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Polymer-Based | Hydrophobic, Polar, Ionic | High capacity, broad applicability, predictable chemistry | Limited selectivity in complex matrices | Strata-X, HLB [12] [13] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Shape-specific, Hydrogen bonding, Hydrophobic | Engineered selectivity, reusability, chemical stability | Complex synthesis, potential for template leakage | MIP-monoliths, MIP-nanozymes [9] [14] |

| Graphene-Based Materials | π-π, Hydrophobic, Electrostatic | Ultra-high surface area, versatile functionalization | Potential for non-specific binding, cost of pure grades | GO, rGO, MGO (Magnetic GO) [11] |

| Hybrid Sorbents | Multiple combined mechanisms | Enhanced performance, synergistic effects | More complex synthesis and characterization | MIP/GO, GO@SiO₂, IL–CS–GOA [11] |

Performance Analysis and Experimental Data

To objectively compare the performance of these sorbents, it is essential to examine quantitative data from controlled experiments, particularly recovery rates and reusability, which are critical for analytical method validation and cost-effectiveness.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Experimental data from recent literature demonstrates the distinct capabilities of different advanced sorbents. MIPs consistently show high recovery rates (>80%) for their specific targets, even in challenging matrices, due to their custom-fit recognition sites [14] [11]. Their robustness allows for significant reusability, with some MIP-monoliths enduring over 200 cycles without substantial performance loss [9]. Graphene-based hybrids also show impressive performance; for instance, magnetic graphene oxide (MGO) composites achieved over 95% recovery for food colorants and demonstrated excellent reusability [11].

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Performance of Advanced and Hybrid Sorbents

| Sorbent Material | Target Analyte(s) | Matrix | Extraction Technique | Recovery (%) | Reusability (Cycles) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiGO-C18 | Aflatoxins (G2, G1, B2, B1) | Food | Pipette-tip SPE (PT-SPE) | >70 | 10 | [11] |

| IL-TGO | Fipronil | Chicken Eggs | PT-SPE & DSPE | >90 | 15 | [11] |

| MGO@UIO-66 | Food Colorants | Soft Drinks, Candies | UA-DSPE | >95 | 6 | [11] |

| N-GQDs/Fe₃O₄@SiO₂/IRMOF-1/MIP | Phenylureas | Cucumber, Tomato | d-MSPE | >80 | 4 | [11] |

| TPhP-MIPs/GO | Triphenyl Phosphate | Environmental Water | DI-SPME | >70 | 110 | [11] |

| GO@MIL | Inorganic Antimony | Water, Tea, Honey | d-µ-SPE | >97 | Not Specified | [11] |

| MIP-Monoliths | Various Biomarkers | Biological Fluids | Online SPE | >90 | >200 | [9] |

Analysis of Key Trends

The data reveals a clear trade-off between universal applicability and target-specific performance. Generic polymer phases like HLB offer a good balance for screening multiple analytes, while MIPs and functionalized graphene hybrids provide superior selectivity and cleaner extracts for specific targets. The integration of MIPs with monolithic structures yields not only high selectivity but also exceptional durability, making them ideal for automated, high-throughput analysis [9]. Furthermore, the emergence of green and sustainable sorbents, such as biomass-based MIPs and bio-sourced graphene, represents a significant trend toward eco-friendly analytical chemistry without compromising performance [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide practical guidance, this section outlines standard and miniaturized protocols for employing these sorbents, as well as key synthesis methodologies.

Standard SPE Workflow

The fundamental steps for a conventional SPE protocol are consistent across different sorbent types and are critical for achieving optimal recovery and cleanliness [12] [13].

Step-by-Step Protocol [12] [13]:

- Conditioning: Activate the sorbent bed by passing 1-2 column volumes of a weak organic solvent (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile). This wets the surface and prepares it for interaction.

- Equilibration: Pass 2-3 column volumes of a solvent that matches the sample matrix (often water or a buffer). This prevents the sample solvent from deactivating the sorbent and ensures efficient retention.

- Sample Loading: Slowly pass the prepared sample through the conditioned sorbent. The target analytes are retained based on the sorbent's chemistry, while some interferences may pass through.

- Washing: Remove weakly bound matrix interferences by applying 1-2 column volumes of a "strong" wash solvent. This solvent is chosen to disrupt non-specific bonds without eluting the targets (e.g., 5% methanol in water for reversed-phase).

- Elution: Release the purified analytes from the sorbent using a small volume of a strong solvent (e.g., pure methanol or acetonitrile, often with a modifier like acid or base for ionic compounds). The eluent is collected for analysis.

Synthesis of Key Hybrid Sorbents

Synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [10]: The bulk polymerization method is a common approach. It involves dissolving the template molecule, functional monomers, and a cross-linker in a porogenic solvent. The mixture is purged with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) to remove oxygen, and polymerization is initiated thermally or by UV light. The resulting rigid polymer block is then ground, sieved to a desired particle size, and extensively washed to remove the template molecule, thereby leaving behind specific recognition cavities.

Synthesis of a COP@ZIF-8 Core-Shell Sorbent [16]: This protocol describes the creation of an advanced coordination polymer-based sorbent for gas adsorption, showcasing the principles of hybrid material synthesis.

- COP Synthesis: A solvothermal method is used. Aluminum chloride (10 g) is added to a mixture of 1,2-dichloroethane (66.67 mL) and benzene (3.34 mL) and stirred at room temperature. The mixture is aged for 24 hours, then quenched with a methanol/ice mixture. The resulting yellow precipitate is sequentially washed with hot water, ethanol, chloroform, and DCM, then dried under vacuum.

- COP@ZIF-8 Formation: COP (100 mg) is dispersed in methanol (19 mL) via sonication. Poly-vinylpyrrolidone (20 mg) is added as a stabilizer and stirred for 12 hours. Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (200 mg) is added, followed by the addition of a methanol solution containing 2-methylimidazole (250 mg). The mixture is agitated for 45 minutes, then centrifuged. The solid product is washed with methanol and dried.

Functionalization of Graphene-Based Materials [11]: Graphene oxide (GO), synthesized typically via a modified Hummers' method, serves as the platform. Its oxygen-containing functional groups (epoxy, hydroxyl, carboxyl) allow for covalent anchoring of various modifiers, such as ionic liquids (ILs), silica nanoparticles (@SiO₂), or magnetic materials (e.g., Fe₃O₄ to form MGO). These reactions are typically carried out in solution under controlled temperature and pH conditions to form the final hybrid sorbent (e.g., IL-GO, GO@SiO₂).

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of methods using advanced sorbents requires specific reagents and materials. The following table lists key items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Sorbent Applications

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HLB Sorbent | Broad-spectrum extraction of polar and non-polar analytes from complex matrices (e.g., plasma, urine). | Excellent for unknown screening; high capacity [12]. |

| Mixed-Mode Cation Exchange (MCX) | Selective extraction of basic compounds; provides orthogonal retention (ionic + hydrophobic). | Essential for clean extracts of basic drugs from biological fluids [12]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Highly selective extraction of a specific target analyte or class (e.g., aflatoxins, pharmaceuticals). | Functions as a "synthetic antibody"; requires method-specific validation [9] [10]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | High-capacity sorbent for aromatic and hydrophobic compounds; platform for hybrid sorbents. | High surface area; can be functionalized for specific applications [11]. |

| Magnetic Graphene Oxide (MGO) | Enables rapid dispersive micro-SPE (d-µ-SPE) and magnetic separation, eliminating centrifugation. | Simplifies and speeds up the sample preparation process [11]. |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Effective removal of polar matrix interferences like fatty acids, sugars, and organic acids. | Commonly used in QuEChERS and for food matrix cleanup [12]. |

| Graphitized Carbon Black (GCB) | Removal of planar molecules and pigments (e.g., chlorophyll, carotenoids). | Can also retain planar analytes if not carefully managed [12]. |

| Strata-X PRO Sorbent | Polymeric sorbent with integrated matrix removal features, streamlining the SPE workflow. | Can reduce the number of steps in the SPE protocol [13]. |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-25 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-25, MF:C58H48O8P2, MW:934.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Topoisomerase I inhibitor 2 | Topoisomerase I Inhibitor 2|RUO|DNA Replication Research |

The landscape of sorbent materials for sample preparation is rich with specialized options, each offering distinct advantages. Conventional polymer phases provide a robust, general-purpose tool, while MIPs deliver unparalleled specificity for targeted analyses. Graphene-based materials offer high capacity and a versatile platform for creating advanced hybrids. The choice of sorbent is not a one-size-fits-all decision but a strategic one, dependent on the analytical goal—whether it is broad-spectrum screening or the precise quantification of a specific compound in a complex matrix like biological fluids, food, or environmental samples. The ongoing trends toward miniaturization, automation, and green chemistry will continue to drive innovation in this field, further enhancing the sensitivity, efficiency, and sustainability of analytical methods.

Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) is a foundational sample preparation technique used extensively by researchers and scientists to purify, concentrate, and isolate analytes from complex matrices such as biological fluids, environmental samples, and food products prior to chromatographic analysis [17] [2]. The effectiveness of SPE hinges on the meticulous design and construction of the extraction cartridge itself. This guide provides a comparative structural analysis of the SPE cartridge, deconstructing its core anatomical components—the polypropylene housing, the frits, and the sorbent bed mass. Understanding the interplay between these components is crucial for selecting the optimal cartridge for specific application needs, ultimately impacting critical performance metrics such as recovery, reproducibility, and throughput in drug development and analytical research.

Structural Decomposition and Function

An SPE cartridge is an integrated system where each physical component plays a critical role in the overall extraction performance. The structure is primarily composed of a polypropylene tube containing a precisely measured mass of sorbent material, secured between two porous frits [18] [19].

Polypropylene Housing

The cartridge body, or housing, is typically constructed from high-density or serum-grade polypropylene [18] [20] [19]. This material is chosen for its excellent chemical inertness, ensuring it does not react with or introduce contaminants into the sample or elution solvents. The standardized syringe-like shape and bottom outlet allow for universal compatibility with various vacuum manifolds and positive pressure systems [20]. For analyses particularly sensitive to organic leachates, specialized cartridges with glass housing are available [18].

Frits: The Gatekeepers

Positioned above and below the sorbent bed, frits are porous discs that perform two essential functions: they permanently contain the sorbent particles within the cartridge, and they act as a preliminary filter for the sample and solvent solutions [18] [19]. The most common frit material is polyethylene, though alternative materials like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE or Teflon), stainless steel, or glass are used for specific analytical challenges, such as the analysis of phthalate esters (PAEs) where interference from plasticizers must be avoided [18] [20]. The quality of the frits is vital; they must ensure uniform solvent flow without becoming clogged by particulates.

Sorbent Bed Mass

The sorbent bed is the functional heart of the cartridge, where the chemical separation occurs. The bed mass refers to the weight of the solid sorbent material packed into the housing, which directly determines the cartridge's capacity—the total amount of analyte and interfering substances it can retain [17] [20]. Sorbents can be broadly classified into several categories based on their retention mechanism, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Classification of Common SPE Sorbents by Retention Mechanism

| Sorbent Type | Retention Mechanism | Representative Sorbents | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed Phase | Hydrophobic (non-polar) interactions [21] | C18, C8, HLB [6] | Non-polar analytes from polar matrices (e.g., water) [22] |

| Normal Phase | Polar interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) [21] | Silica, Diol, Florisil [6] | Polar analytes from non-polar matrices (e.g., hexane) [22] |

| Ion Exchange | Electrostatic (charge) interactions [21] | SCX, SAX, WCX, WAX [6] | Ionic compounds; charge can be controlled via pH [22] |

| Mixed-Mode | Combined mechanisms (e.g., hydrophobic + ionic) [21] | MCX, MAX [6] | Fractionating complex samples with diverse analytes [21] |

Comparative Performance Data: Bed Mass and Cartridge Sizing

Selecting the correct cartridge size and bed mass is a fundamental step in method development. The choice is governed by two primary factors: the volume of the sample and the total compound load (including both target analytes and matrix interferences) [19]. An undersized cartridge will lead to "breakthrough," where analytes are not retained, resulting in low recovery. An oversized cartridge wastes solvents, increases processing time, and may require larger, more difficult-to-evaporate elution volumes.

Table 2: SPE Cartridge Sizing Guide Based on Sample Volume and Compound Load

| Sample Volume | Total Compound Load | Recommended Cartridge Size | Typical Sorbent Bed Mass | Typical Elution Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - 10 mL [19] | 2 - 6 mg [19] | 1 mL [19] | 50 - 100 mg [17] | 0.1 - 0.2 mL [17] |

| 10 - 100 mL [19] | 6 - 1000 mg [19] | 3 mL [19] | 200 - 500 mg [17] [19] | 1 - 3 mL [17] |

| 100 mL - 1 L [19] | >1000 mg [19] | 6 mL [19] | 500 - 1000 mg [17] | 2 - 6 mL [17] |

The capacity of a bonded silica sorbent is typically 1-5% of its mass. Therefore, a 100 mg cartridge should not be expected to retain more than 5 mg of total material [20]. For robust method development, it is recommended that the total estimated load of the target compound and interferents should not exceed half of the cartridge's capacity [20].

Experimental Protocol: Standard SPE Workflow

The following detailed methodology outlines a standard bind-and-elute procedure using a reversed-phase SPE cartridge, a common scenario in bioanalytical and environmental labs.

Title: Standard SPE Bind-and-Elute Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Prepare the sample to ensure optimal retention of the analyte. This may involve dilution with water or a buffer, pH adjustment to ensure the analyte is in the correct ionic form, and filtration or centrifugation to remove particulates that could clog the frits [17]. For instance, serum and plasma are often diluted with an equal volume of water or buffer [17].

- Conditioning: Pass 1-2 column volumes of methanol (or acetonitrile) through the cartridge to solvate the sorbent and activate the bonded functional groups. This is followed by 1-2 column volumes of water or a buffer that matches the sample's matrix [17] [19]. Critical: Do not allow the sorbent bed to dry out after conditioning, as this can lead to poor and inconsistent analyte recovery [17].

- Equilibration: Pass 1-2 column volumes of the sample solvent (e.g., the same aqueous buffer used in pre-treatment) through the conditioned cartridge to prepare the sorbent surface for the sample [17].

- Sample Loading: Apply the pre-treated sample to the top of the cartridge reservoir. A controlled, slow flow rate (e.g., 1-2 mL/min) is crucial to maximize the interaction time between the analytes and the sorbent, preventing breakthrough [17].

- Washing: Use 1-2 column volumes of a solvent that is strong enough to remove undesired matrix interferences but weak enough to leave the target analytes bound. A common wash for reversed-phase SPE is a water/organic solvent mix (e.g., 5% methanol) [17].

- Elution: Apply 1-2 small aliquots of a strong solvent to disrupt the analyte-sorbent interactions and collect the purified analytes. For reversed-phase SPE, this is typically a pure organic solvent like methanol or acetonitrile. Using two small volumes is more efficient at displacing the analyte than one large volume, leading to a more concentrated final extract [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of SPE requires more than just the cartridge. The table below lists key reagents and equipment essential for setting up and performing SPE in a research environment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for SPE

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SPE Vacuum Manifold | Processes multiple cartridges simultaneously by applying negative pressure [19]. | 12-, 24-, or 96-port models; may include flow control valves and collection racks [19]. |

| Positive Pressure System | Uses gas pressure to drive solvents; offers more precise flow control than vacuum and prevents channeling [19]. | Electronically controlled or air-actuated systems [19]. |

| Conditioning Solvents | Activate the sorbent and prepare it for sample loading [19]. | Methanol, Acetonitrile; followed by water or aqueous buffer [17] [19]. |

| Wash & Elution Solvents | Selectively remove interferences (wash) and recover target analytes (elution) [17]. | Wash: 5% MeOH in water. Elution: Pure MeOH, ACN, or custom mixes [17]. |

| Buffers & pH Adjusters | Control the ionic form of ionizable analytes to maximize retention on ion-exchange or mixed-mode sorbents [22]. | Formic acid, Ammonium acetate, Phosphate buffers [17]. |

| Connectors & Adapters | Link cartridges to solvent reservoirs or sample tubes to increase loading capacity [18] [19]. | Male/female luer connectors, sample reservoir tubes [19]. |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-13 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-13, MF:C13H8Cl2N2O4, MW:327.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ramatroban-d4 | Ramatroban-d4 | Ramatroban-d4 is a deuterated internal standard for precise quantification of Ramatroban in research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is a foundational technique in modern analytical workflows, serving to purify, concentrate, and isolate target analytes from complex sample matrices. The core principle of SPE involves the differential distribution of analytes between a solid stationary phase (sorbent) and a liquid mobile phase (sample matrix and solvents). Successful separation hinges on selecting a sorbent chemistry that exploits specific molecular interactions with target compounds while minimizing retention of matrix interferents. The strategic selection of SPE sorbents directly determines critical method performance parameters, including extraction recovery, matrix cleanup efficiency, detection sensitivity, and method reproducibility [23].

The evolution of SPE from its early applications in the 1940s to its current sophisticated form has been marked by the development of diverse sorbent materials with specialized functionalities [2]. While C18 silica became the first widely adopted "universal" sorbent, contemporary analytical challenges require a more nuanced approach that matches sorbent properties to specific analyte characteristics and matrix compositions [24]. Modern SPE method development has shifted from empirical trial-and-error toward predictive approaches based on chromatographic retention data and solvation parameters, enabling analysts to systematically determine optimal sorbent chemistry, loading capacity, and elution conditions [24]. This framework provides a structured methodology for selecting sorbents based on scientifically-established interaction mechanisms, helping analysts navigate the extensive portfolio of available materials to develop robust, efficient extraction methods.

Fundamental SPE Interaction Mechanisms

Understanding the primary interaction mechanisms between analytes and sorbents is essential for strategic selection. SPE separations predominantly exploit three categories of molecular interactions: polarity-based, ion exchange, and mixed-mode mechanisms. Each mechanism follows distinct chemical principles and is optimally suited for specific analyte properties.

Polarity-Based Interactions

Polarity-based interactions operate on the principle of "like dissolves like," where compounds with similar polarity to the sorbent surface exhibit stronger retention [25]. These interactions form the basis for two complementary operational modes:

Reversed-Phase SPE: Utilizes hydrophobic sorbents (e.g., C18, C8, polymeric hydrocarbons) with polar aqueous samples. This mode retains non-polar to moderately polar analytes through van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions. The strength of retention increases with the hydrophobicity of both the analyte and the sorbent ligand—C18 provides stronger retention than C8 due to its longer alkyl chain [23] [25].

Normal-Phase SPE: Employs polar sorbents (e.g., silica, Florisil, alumina) with non-polar organic samples. This mode retains polar analytes through hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, and π-π bonding. Normal-phase separations are particularly effective for removing polar interferents from non-polar sample matrices [23] [25].

Ion Exchange Mechanisms

Ion exchange SPE operates on the principle of "opposites attract," utilizing electrostatic interactions between charged analytes and oppositely charged sorbent functional groups [25]. The effectiveness of ion exchange depends critically on the charge states of both the analyte and sorbent, which are controlled by solution pH relative to their pKa values. This mechanism encompasses several sorbent types:

Strong Cation Exchange (SCX): Features permanently charged sulfonic acid groups that attract and retain positively charged basic compounds. SCX is recommended for weak basic analytes that can be selectively eluted by neutralizing their charge [23] [25].

Strong Anion Exchange (SAX): Contains quaternary ammonium groups with permanent positive charges that retain negatively charged acidic compounds. SAX is ideal for weak acids that can be neutralized for elution [23] [25].

Weak Ion Exchangers: Include carboxylic acid (weak cation exchange) and amino groups (weak anion exchange). These sorbents exhibit pH-dependent ionization and are typically paired with strong acidic or basic analytes to enable gentle elution conditions [25].

Mixed-Mode and Selective Interactions

Mixed-mode sorbents incorporate multiple interaction mechanisms within a single material, typically combining reversed-phase and ion exchange functionalities. This design provides enhanced selectivity for analytes with specific functional groups and enables sophisticated cleanup protocols through sequential elution based on different interaction types [24] [2]. Advanced selective sorbents have also been developed for challenging applications:

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Synthetic polymers containing tailor-made recognition sites complementary to specific target molecules in shape, size, and functional group orientation [24] [2].

Immunosorbents: Utilize immobilized antibodies that provide high specificity for particular analytes or compound classes through biological recognition [24].

Restricted Access Materials (RAM): Prevent macromolecular matrix components (e.g., proteins) from accessing retention sites while allowing smaller analytes to penetrate and interact with the sorbent interior [24] [2].

Strategic Sorbent Selection Framework

Selecting the optimal SPE sorbent requires systematic consideration of analyte properties, matrix composition, and analytical objectives. The following strategic framework provides a step-by-step methodology for matching sorbent chemistry to specific application requirements.

Analyte-Driven Sorbent Selection

The chemical properties of target analytes represent the primary consideration for sorbent selection. The decision pathway begins with classifying compounds according to their polarity and ionization characteristics:

Table 1: Sorbent Selection Based on Analyte Properties

| Analyte Characteristic | Recommended Sorbent Type | Specific Sorbent Examples | Retention Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-polar | Reversed-phase | C18, C8, HLB | Hydrophobic interactions |

| Moderately polar | Reversed-phase | HLB, C8 | Hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance |

| Polar (uncharged) | Normal-phase | Silica, Florisil | Polar interactions (H-bonding, dipole) |

| Strong acids | Strong anion exchange | SAX | Ionic attraction |

| Weak acids | Weak anion exchange | NHâ‚‚, MAX | Ionic/polar interactions |

| Strong bases | Strong cation exchange | SCX | Ionic attraction |

| Weak bases | Weak cation exchange | WCX, MCX | Ionic/hydrophobic interactions |

| Mixed functionality | Mixed-mode | MCX, MAX, HLB-CX | Combined ionic/hydrophobic |

| Planar molecules | Graphitized carbon | GCB | π-π interactions |

For non-polar analytes such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), reversed-phase sorbents like C18 provide strong hydrophobic retention, enabling efficient concentration from aqueous matrices [23]. Moderately polar compounds may be effectively retained on sorbents with balanced hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity, such as hydrophilic-lipophilic balanced (HLB) polymers, which maintain retention across a wide pH range (1-14) [23] [26]. For polar uncharged analytes, normal-phase sorbents like silica or Florisil utilize hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions for retention [23].

The ionization state of analytes critically influences sorbent selection for ionizable compounds. Strong acids (low pKa) remain ionized across most pH ranges and are best retained on strong anion exchange (SAX) sorbents, while weak acids (pKa 2-8) require pH control approximately two units above their pKa to ensure ionization for effective retention on weak anion exchange materials like NHâ‚‚ [25]. Similarly, strong bases pair with strong cation exchange (SCX) sorbents, while weak bases are optimally retained on weak cation exchange (WCX) materials [25]. Compounds containing both ionic and hydrophobic functional groups, such as many pharmaceutical compounds, are ideally suited for mixed-mode sorbents (e.g., MCX, MAX) that combine ion exchange and reversed-phase mechanisms [24] [23].

Matrix-Specific Method Optimization

The sample matrix composition significantly influences sorbent selection by introducing competing interactions and potential interferents that can compromise extraction efficiency. Different matrices present characteristic challenges that require tailored cleanup approaches:

Table 2: Matrix-Specific Sorbent Selection and Cleanup Strategies

| Sample Matrix | Primary Interferences | Recommended Sorbent | Cleanup Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological fluids | Proteins, lipids | HLB, C18, RAM | Protein precipitation, phospholipid removal |

| Plasma/Serum | Phospholipids, proteins | Mixed-mode cation exchange, HLB | Selective elution, protein denaturation |

| Fruits/Vegetables | Sugars, organic acids, pigments | PSA, GCB, C18 | Anion exchange, planar interaction |

| Water | Humic acids, organic matter | C18, HLB, Mixed-mode | Hydrophobic retention, ion exchange |

| Soil/Sediment | Humic matter, hydrocarbons | C18, Florisil | Normal-phase cleanup after extraction |

| Grains/Cereals | Lipids, pigments | PSA, Florisil, GCB | Lipid removal, pigment adsorption |

Biological matrices like plasma and serum contain phospholipids and proteins that can cause matrix effects in LC-MS analysis. For these samples, mixed-mode cation exchange (MCX) sorbents provide effective cleanup by retaining basic drugs while excluding phospholipids, or restricted access materials (RAM) that physically exclude proteins while retaining small molecule analytes [23] [2]. Food matrices such as fruits and vegetables typically contain sugars, organic acids, and pigments that interfere with analysis. For pesticide residue analysis in these matrices, combination cleanups using primary secondary amine (PSA) to remove organic acids and graphitized carbon black (GCB) to adsorb planar pigments have proven highly effective [23]. Environmental water samples may contain diverse organic matter including humic acids, which can be addressed using reversed-phase sorbents like C18 or HLB for hydrophobic compounds, or mixed-mode sorbents for ionic contaminants [24] [23].

The following decision workflow provides a systematic approach for selecting sorbents based on analyte and matrix properties:

Figure 1: Sorbent Selection Decision Workflow

Analytical Method Considerations

The choice of detection method and regulatory requirements further refine sorbent selection. LC-MS/MS applications typically require cleaner extracts than HPLC-UV methods, favoring sorbents with superior selectivity such as mixed-mode or molecularly imprinted polymers [23]. GC-MS methods often prioritize complete removal of non-volatile interferents that could accumulate in the injection port or cause elevated baseline noise [23]. Regulatory methods frequently specify particular sorbents, such as Florisil for EPA pesticide methods (8081/8082) or C18 for various pharmaceutical applications according to USP monographs [23].

Throughput requirements also influence sorbent selection and format choice. High-throughput laboratories benefit from 96-well SPE plates with standardized sorbent masses that enable automation, while manual methods may utilize traditional cartridges or disks [23] [2]. The trend toward miniaturization has produced various formats including pipette-tip SPE for limited sample volumes, solid-phase microextraction (SPME) for solvent-free extraction, and disk formats for processing large sample volumes without clogging [2].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Validating sorbent performance through systematic experimentation is essential for developing robust SPE methods. The following section presents standardized protocols and comparative performance data for different sorbent-analyte combinations.

Standard SPE Method Protocol

A generalized SPE protocol encompasses four sequential stages: conditioning, sample loading, washing, and elution. Each stage must be optimized based on the selected sorbent chemistry and analyte properties [23] [25]:

Conditioning: Sequential passage of 3-5 mL of methanol (or elution solvent) followed by 3-5 mL of water or sample buffer through the sorbent bed. This step solvates the sorbent and creates an optimal environment for analyte retention. Reversed-phase sorbents require organic solvent followed by aqueous phase, while normal-phase sorbents need organic conditioning without aqueous exposure [25].

Sample Loading: Application of the prepared sample to the sorbent bed at controlled flow rates (typically 1-10 mL/min). Flow control is critical to ensure adequate interaction time between analytes and sorbent surfaces. For ionizable analytes, sample pH should be adjusted to promote the desired charge state (approximately 2 pH units above pKa for acids, 2 units below pKa for bases) [25].

Washing: Removal of weakly retained matrix interferents using 3-5 mL of a solution that disrupts matrix-sorbent interactions without significantly eluting target analytes. Common wash solutions include water or mild buffers (5-10% methanol) for reversed-phase SPE, or non-polar organic solvents for normal-phase SPE [25].

Elution: Recovery of target analytes using 1-5 mL of a solvent that effectively disrupts analyte-sorbent interactions. Reversed-phase separations typically employ organic solvents (acetonitrile, methanol), while ion exchange methods use pH-adjusted buffers or high-ionic-strength solutions to neutralize electrostatic attraction [25].

Comparative Performance Data

Experimental data from systematic comparisons provides valuable guidance for sorbent selection. The following table summarizes performance metrics for different sorbent types applied to common analytical challenges:

Table 3: Comparative Sorbent Performance Data

| Application | Sorbent Type | Average Recovery (%) | Matrix Effects (% Suppression) | Key Interferences Removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Drugs in Plasma | MCX | 95-102 | <15% | Phospholipids, proteins |

| C18 | 85-92 | 25-40% | Proteins only | |

| HLB | 90-96 | 20-30% | Proteins, some phospholipids | |

| Acidic Pesticides in Water | MAX | 92-98 | <10% | Humic acids, anions |

| C18 | 75-85 | 30-50% | Hydrophobic interferents only | |

| SAX | 88-94 | 15-25% | Inorganic anions | |

| PAHs in Soil Extracts | C18 | 94-99 | N/A | Aliphatic hydrocarbons |

| Florisil | 90-96 | N/A | Polar organics | |

| GCB | 85-92 | N/A | Planar pigments | |

| Mycotoxins in Cereals | HLB | 89-95 | 10-20% | Lipids, pigments |

| PSA | 85-91 | 15-25% | Sugars, fatty acids | |

| Immunoaffinity | 95-103 | <5% | Matrix-specific |

Mixed-mode cation exchange (MCX) sorbents demonstrate superior performance for basic drugs in plasma, providing both high recovery (>95%) and significant reduction of matrix effects (<15% suppression) compared to conventional reversed-phase sorbents [23]. For acidic compounds in environmental water samples, mixed-mode anion exchange (MAX) sorbents offer enhanced selectivity against humic acid interferents while maintaining excellent recovery [23]. Specialized sorbents like immunoaffinity materials provide exceptional cleanup for specific analyte classes such as mycotoxins, though at higher cost and with narrower application range [24].

Case Study: Lead Extraction from Aqueous Matrices

Recent research comparing monolithic (m-SPE) versus particle-packed (p-SPE) columns for lead extraction demonstrates how sorbent architecture influences performance. Using supramolecular crown ether-functionalized sorbents specifically designed for Pb²⺠recognition, researchers optimized parameters including solution pH, flow rate, and elution conditions [3]. Both column types exhibited excellent Pb²⺠retention with minimal interference from common matrix ions, but the monolithic columns demonstrated advantages due to their high permeability, low backpressure, and robust porosity [3]. These characteristics translated to enhanced selectivity, reproducibility, and overall efficiency, particularly for processing larger sample volumes [3]. Both column types maintained performance over multiple cycles without significant efficiency loss, demonstrating the potential for reusable SPE in environmental monitoring applications [3].

The following workflow illustrates the experimental protocol for comparative sorbent evaluation:

Figure 2: Sorbent Performance Evaluation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following essential materials represent key solutions for implementing the SPE selection framework described in this guide:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SPE Method Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SPE | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase Sorbents | C18, C8, HLB, Polymer-based | Hydrophobic retention of non-polar analytes | C18 for strong retention; HLB for polar compounds |

| Normal-Phase Sorbents | Silica, Florisil, Alumina | Polar retention mechanisms | Effective for pigment removal |

| Ion Exchange Sorbents | SCX, SAX, WCX, NHâ‚‚ | Ionic retention of charged analytes | pH control critical for performance |

| Mixed-Mode Sorbents | MCX, MAX, WAX, WCX | Combined ionic/hydrophobic retention | Ideal for pharmaceutical compounds |

| Selective Sorbents | MIPs, Immunosorbents, RAM | Molecular recognition | High specificity but limited application range |

| Conditioning Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water | Sorbent activation | Match to sorbent chemistry |

| Elution Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Buffer solutions | Analyte recovery | Strength matched to retention mechanism |

| Buffer Systems | Ammonium acetate/formate, Phosphate | pH control for ionizable compounds | Volatile buffers preferred for MS |

Strategic selection of SPE sorbents based on systematic analysis of analyte properties, matrix composition, and analytical requirements represents a critical foundation for robust method development. The framework presented in this guide enables researchers to navigate the complex landscape of available sorbents by applying scientifically-established principles of molecular interactions. As SPE technology continues to evolve, trends point toward increased selectivity through molecular recognition mechanisms, enhanced reusability, and greater compatibility with automated high-throughput platforms [24] [2]. The integration of advanced materials such as molecularly imprinted polymers, immunosorbents, and monolithic architectures further expands the application range of SPE while improving efficiency and sustainability [24] [3] [27]. By applying this systematic selection framework, researchers can develop extraction methods that deliver optimal recovery, superior cleanup, and enhanced analytical sensitivity across diverse application domains.

Application-Optimized SPE Methods for Challenging Matrices

The determination of drugs and their metabolites in biological fluids is fundamental to toxicological analysis, pharmacokinetic studies, and pharmaceutical development. [27] However, the complexity of biological matrices—plagued by endogenous compounds and typically low analyte concentrations—demands efficient sample preparation to achieve the sensitivity and selectivity required in modern analytical chemistry. Among sample preparation techniques, Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) has emerged as a powerful tool, gradually replacing traditional methods like liquid-liquid extraction (LLE). [28] SPE offers significant advantages over LLE, including lower solvent consumption, enormous saving of time, increased extraction efficiency, decreased evaporation volumes, higher selectivity, cleaner extracts, greater reproducibility, and avoidance of emulsion formation. [28] The core of SPE technology lies in the cartridges and their sorbents, which selectively retain and elute analytes, achieving concentration, purification, and enrichment of target compounds from complex matrices. [6] This guide provides a comparative analysis of SPE cartridges for extracting drugs and metabolites from plasma, serum, and urine, delivering objective performance data and experimental protocols to inform method development in bioanalytical laboratories.

SPE Cartridge Fundamentals and Classification

SPE cartridges are typically constructed from polypropylene or other inert plastic materials, pre-packed with 100–500 mg of sorbent secured between upper and lower frits. [6] The extraction process leverages various interaction mechanisms between the analyte and the solid sorbent, primarily classified by retention mechanism. [28] [6]

Table 1: Classification of SPE Sorbents by Retention Mechanism

| Type | Description | Retention Mechanism | Representative Sorbents | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed Phase | Utilizes hydrophobic interactions | Hydrophobic dispersion forces | C18, C8, Phenyl, C4, HLB | Non-polar or moderately polar compounds [6] |

| Normal Phase | Employs polar interactions | Hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions | Silica, Aminopropyl (NHâ‚‚), Cyano (CN), Diol | Polar compounds [6] |

| Ion Exchange | Separates ionic compounds | Electrostatic (ionic) interactions | SAX (Strong Anion Exchange), SCX (Strong Cation Exchange) | Acidic or basic ionic compounds [6] |

| Mixed-Mode | Combines two or more mechanisms | Hydrophobic + Ionic interactions | MCX, MAX, PCX | Basic or acidic drugs; offers superior cleanup [6] [29] |

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for processing a biofluid sample through an SPE cartridge, from conditioning to analyte elution.

Comparative Performance Data for SPE Cartridges

The selection of an appropriate SPE sorbent is matrix- and analyte-dependent. Experimental data from comparative studies provides critical insight for making an informed choice.

Extraction of Specific Analytes from Urine

A definitive study compared a traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) method with a modern Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) method for detecting morphine in urine, followed by chromatographic analysis. [28]

Table 2: SPE vs. LLE for Urinary Morphine Detection (n=58)

| Extraction Method | Chromatography | Detection Rate | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLE-TLC (Liquid-Liquid Extraction) | Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) | 48% (28/58) | Traditional, routine method |

| SPE-HPTLC (Solid Phase Extraction) | High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) | 74% (43/58) | Higher recovery, cleaner extracts, avoids emulsion formation [28] |

The data demonstrates the clear superiority of the SPE-based method, which improved the detection rate for urinary morphine by over 50% compared to the traditional LLE approach. [28]

Extraction Efficiencies for Carboxylic Acids from Water

While not a biological fluid, a study on carboxylic acid extraction from water provides a valuable model for understanding sorbent selectivity, which can be extrapolated to metabolic acids in biofluids.

Table 3: SPE Sorbent Efficiency for Carboxylic Acids in Water

| Sorbent Type | Aliphatic Carboxylic Acid Efficiency | Aromatic Carboxylic Acid Efficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silica (Normal Phase) | 92.1% | Not Specified | Achieved the highest aliphatic acid efficiency [30] |

| Strata X (Polymeric Reversed Phase) | Not Specified | 28% | Achieved the highest aromatic acid efficiency [30] |

| C-18 (Reversed Phase) | Lower than Silica | Lower than Strata X | Efficiency was lower for both acid types [30] |

Purification of Phosphopeptides from Complex Digests

For proteomic and metabolomic applications, the purification of phosphorylated peptides is critical. A comparison of 16 different sorbents revealed significant performance variations.

Table 4: SPE for Phosphopeptide Purification (from 1 µg tissue digests)

| Sorbent Category | Specific Sorbents Performing Well | Performance Gain vs. Commercial SPE | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase (RP) | 2 of 8 tested | 22-58% more unique phosphopeptides identified | Sample loss significantly reduced [31] [32] |

| Graphite | 1 of 5 tested | 22-58% more unique phosphopeptides identified | Recovery higher by 132-155% [31] [32] |

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) | 1 of 1 tested | 22-58% more unique phosphopeptides identified | Excellent results for low-amount samples [31] [32] |

This study highlights that up to 88% recovery can be achieved using an appropriately selected SPE method and that a significant proportion (30%) of identified phosphopeptides may be unique to each specific SPE method. [31] [32]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, detailed methodologies from key cited studies are provided below.

This protocol describes the sample preparation and analysis used to generate the comparative data in Table 2.

- Sample Hydrolysis: A 20 mL aliquot of urine is acidified with 1 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid and heated at 100°C for 15 minutes to hydrolyze glucuronide conjugates. The mixture is then cooled.

- pH Adjustment: The pH of the hydrolyzed sample is adjusted to 8-9 using concentrated ammonia solution.

- SPE Procedure:

- Cartridge: LiChrolut TSC SPE columns (300 mg, 3 mL).

- Conditioning: The column is conditioned with 2 x 3 mL of methanol, drawn slowly without letting the sorbent bed dry.

- Loading: 3 mL of the pH-adjusted sample is loaded onto the column at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

- Washing: Interfering components are removed by passing 2 x 3 mL of distilled water through the column at 2 mL/min.

- Drying: The column is dried under a vacuum of 10 in.Hg.

- Elution: Morphine is eluted with 2 mL of methanol:ammonia (9:1) without applying vacuum.

- Analysis: The eluate is dried under a nitrogen stream, reconstituted in 100 µL methanol, and 5 µL is spotted on an HPTLC plate. The plate is developed in a saturated chamber with ethyl acetate:methanol:ammonia (85:10:5) and visualized.

This innovative protocol uses a customized SPE cartridge for microsampling, storage, and direct analysis of biofluids.

- Device Preparation: A homemade SPE cartridge is created by packing 10 mg of a sorbent (e.g., Mixed-Mode Cation-Exchange (MCX), Polymeric Cation-Exchange (PCX), or HLB) into a 1 mL plastic syringe, secured between two frits.

- Microsampling: The cartridge is used to collect a small volume (<20 µL) of raw biofluid (blood, plasma, serum, or urine) via the syringe plunger.

- Storage: The collected sample is stored in the dry-state within the SPE sorbent at room temperature. Remarkably, analytes like diazepam have shown stability for over a year using this method.

- Direct Analysis: The SPE cartridge is directly coupled to an Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometer (ESI-MS). The sorbent is wetted with an elution solvent, and the analyte is directly eluted into the MS for analysis, bypassing the need for chromatography.

This protocol outlines a standard SPE procedure applicable to various aqueous samples, including biofluids.

- Conditioning: The cartridge (e.g., Silica, C-18, Strata X) is conditioned with 5 mL of methanol, followed by 5 mL of deionized water.

- Sample Loading: A large volume (e.g., 1.5 liters for environmental water) is loaded onto the SPE column using a vacuum manifold apparatus at a rate of 10 mL/min.

- Elution:

- For Strata X, analytes are eluted with 5 mL of acetone, followed by 5 mL of methylene chloride.

- For silica-based cartridges, a mixture of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and methanol (1:1, v/v) is used.

- Post-Processing: The eluted sample is dried under a controlled laminar flow, reconstituted in a GC-grade solvent (e.g., methylene chloride), and injected for instrumental analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful SPE-based bioanalysis relies on several key components. The following table details essential reagents and materials.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for SPE Bioanalysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Mode SPE Cartridges (e.g., MCX, PCX) | Combines hydrophobic and ionic interactions for superior cleanup of basic/acidic drugs from complex matrices. [29] | Extraction of illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine) from plasma and urine; provides cleaner extracts. [29] |

| Polymer-based Sorbents (e.g., HLB) | Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balanced copolymers; retain a wide range of analytes without ion-exchange groups. [6] [29] | Generic method development; purification of phosphopeptides; microsampling of diverse biofluids. [31] [29] |

| Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) Cartridges | Retain positively charged analytes at low pH via electrostatic interactions. [6] | Selective extraction of basic drugs and metabolites from biological matrices. [6] |

| Strata X Sorbent | A polymeric reversed-phase sorbent with high capacity and retention for a broad spectrum of compounds. [30] | Efficient extraction of aromatic carboxylic acids from aqueous matrices. [30] |

| Acidified Iodoplatinate Reagent | A chemical visualization spray used to detect the presence of specific compounds like morphine on TLC/HPTLC plates. [28] | Confirmation of morphine presence in urinary extracts after SPE and TLC development. [28] |

| Antimycobacterial agent-2 | Antimycobacterial agent-2, MF:C31H50O5, MW:502.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| APJ receptor agonist 6 | APJ receptor agonist 6, MF:C29H34FN3O5, MW:523.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of SPE is continuously evolving to meet demands for higher sensitivity and throughput. Key trends include:

- Advanced Sorbent Materials: Engineered materials such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks, graphene oxide, and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are being integrated into SPE designs. These materials offer enhanced selectivity and capacity for target analytes in complex matrices. [6] [27]

- Automation and Online Systems: Online SPE systems that couple directly to HPLC or MS are gaining traction. These systems improve throughput and precision by fully automating the extraction and analysis process. [33] One study noted that while online Turbulent Flow Chromatography (TFC) produced better matrix removal, online SPE offered superior peak shape and efficiency. [33]

- Innovative Microsampling Platforms: The concept of using SPE cartridges themselves as microsampling and storage devices is a significant innovation. [29] This approach, which enables room-temperature storage and stabilizes labile analytes for extended periods, is poised to revolutionize remote sampling and biobanking, particularly in resource-limited settings. [29]

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is a cornerstone technique in modern environmental analysis, enabling researchers to isolate and concentrate trace pollutants from complex matrices such as water and soil [2]. This sample preparation method has largely superseded traditional liquid-liquid extraction due to its reduced organic solvent consumption, shorter processing time, and superior efficiency [2]. The core principle of SPE involves the partitioning of analytes between a liquid sample and a solid sorbent, which selectively retains target compounds while allowing interfering matrix components to pass through [2]. The retained analytes are subsequently recovered using an appropriate elution solvent, resulting in a purified and concentrated extract ready for instrumental analysis [2]. The selection of appropriate SPE cartridges is particularly critical in environmental monitoring where target analytes often exist at trace levels amidst complex sample matrices, necessitating efficient enrichment and cleanup procedures to achieve the sensitivity and specificity required by regulatory standards [34].

The evolution of SPE technology has introduced multiple configurations and sorbent chemistries tailored to different analytical challenges. From traditional particle-packed cartridges to advanced monolithic designs, each format offers distinct advantages for specific applications [3] [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of SPE cartridge performance for trace pollutant enrichment from water and soil samples, presenting experimental data to inform researchers' selection process within the broader context of comparative SPE cartridge research for different matrices.

SPE Cartridge Types and Configurations

Structural Classifications and Operational Characteristics

SPE cartridges are available in several physical configurations, each designed to address specific sample processing requirements. The most common formats include traditional cartridges, disks, and multi-well plates, with each system offering distinct advantages and limitations for environmental applications [2].

Table 1: Comparison of SPE Configurations for Environmental Applications

| Parameter | Cartridge | Disk | Multi-well SPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorbent Weight | 4–30 mg [2] | 4–200 mg [2] | 3–200 mg [2] |

| Applicable Volume | 500 μL–50 mL [2] | 0.5–1 L [2] | 0.65–2 mL [2] |

| Primary Applications | Wide variety of sample matrices [2] | Substantial water samples [2] | High-throughput biological samples [2] |