Comparative Method in Analytical Validation: A Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the comparative method, a critical experiment in analytical method validation used to estimate systematic error or inaccuracy.

Comparative Method in Analytical Validation: A Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the comparative method, a critical experiment in analytical method validation used to estimate systematic error or inaccuracy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts from defining the comparative method's purpose in assessing systematic error against a reference to the strategic selection of a comparator. The scope extends to methodological execution, including experimental design, data analysis techniques like difference plots and linear regression, and troubleshooting common pitfalls. Finally, it explores validation within a regulatory framework, discussing risk-based approaches for method changes and the distinctions between comparability and equivalency, synthesizing best practices for ensuring data reliability and regulatory compliance.

Comparative Method Fundamentals: Defining Purpose and Key Concepts

In analytical method validation, the comparison of methods experiment is a critical study designed to estimate the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new (test) analytical method relative to a established comparative method [1]. This process is foundational for ensuring the reliability of data in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and quality control laboratories. Systematic error, also known as bias, represents a consistent or proportional difference between observed values and the true value [2]. Unlike random error, which affects precision and varies unpredictably, systematic error skews measurements in a specific direction, potentially leading to false conclusions and decisions if left unquantified [2]. Determining this bias is therefore not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental requirement for demonstrating that a method is fit for its intended purpose and that future measurements in routine analysis will be sufficiently close to the true value [3].

The core principle of this comparison is to analyze a set of patient specimens or test samples using both the new method and a comparative method, then estimate systematic errors based on the observed differences [1]. The results are used to judge the acceptability of the test method, often against predefined medical or quality-based decision limits [4]. This process fits within a broader method validation plan, which typically also includes experiments for precision (replication) and specific investigations into potential interferences [1] [4].

Theoretical Foundations of Analytical Error

Distinguishing Random and Systematic Error

Understanding the distinction between random and systematic error is crucial for interpreting comparison of methods data.

Random Error: This is a chance difference between an observed value and the true value. It affects the precision of a measurement, meaning it causes variability when the same quantity is measured repeatedly under equivalent conditions [2]. In a dataset, random error causes observations to scatter randomly around the true value. In highly controlled settings, it can often be reduced by taking repeated measurements and using their average [2]. Sources of random error can include electronic noise in instruments, natural variations in experimental contexts, and slight fluctuations in how measurements are read [2] [5].

Systematic Error: This is a consistent or proportional difference between the observed values and the true value. It affects the accuracy (or trueness) of a measurement, meaning it consistently skews all measurements in a specific direction away from the true value [2]. Systematic error is also referred to as bias and is generally a more significant problem in research and analysis because it can lead to false conclusions about the relationship between variables [2]. It cannot be reduced by simply repeating measurements [6].

Table: Comparison of Random and Systematic Error

| Feature | Random Error | Systematic Error |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Unpredictable, chance differences | Consistent or proportional differences |

| Impact on Data | Affects precision (reproducibility) | Affects accuracy (trueness) |

| Direction of Effect | Equally likely to be higher or lower than true value | Consistently higher or lower than true value |

| Elimination | Cannot be eliminated, but can be reduced | Can potentially be eliminated by identifying the cause |

| Common Sources | Natural variations, imprecise instruments, procedural fluctuations | Miscalibrated instruments, flawed procedures, incorrect assumptions |

Systematic errors can be categorized based on their behavior, which helps in diagnosing their root cause [2] [5]:

- Constant Error (Offset Error): This error remains the same absolute amount across the entire analytical range. It occurs when a scale is not calibrated to a correct zero point and is also called an additive or zero-setting error [2] [5]. For example, a balance that always reads 0.5 grams over the true mass introduces a constant error.

- Proportional Error (Scale Factor Error): This error changes in proportion to the concentration of the analyte. It occurs when measurements consistently differ from the true value by a constant percentage (e.g., by 10%) and is also known as a multiplier error [2] [5]. An example would be an instrument where the response factor is incorrectly calculated.

These errors can originate from various aspects of the analytical process [6]:

- Instrumental Error: Caused by inaccurate instruments, such as a miscalibrated pH meter or a balance that does not function properly [6].

- Procedural Error: Arises from flaws in the experimental protocol or inconsistent application of procedures [6].

- Human Error: Includes transcriptional errors (e.g., recording data incorrectly) and estimation errors (e.g., misreading a scale) [6].

- Specimen-Based Error: In clinical chemistry, interferences from substances in a patient sample or instability of the analyte during storage can introduce systematic error specific to that specimen [1].

Designing the Comparison of Methods Experiment

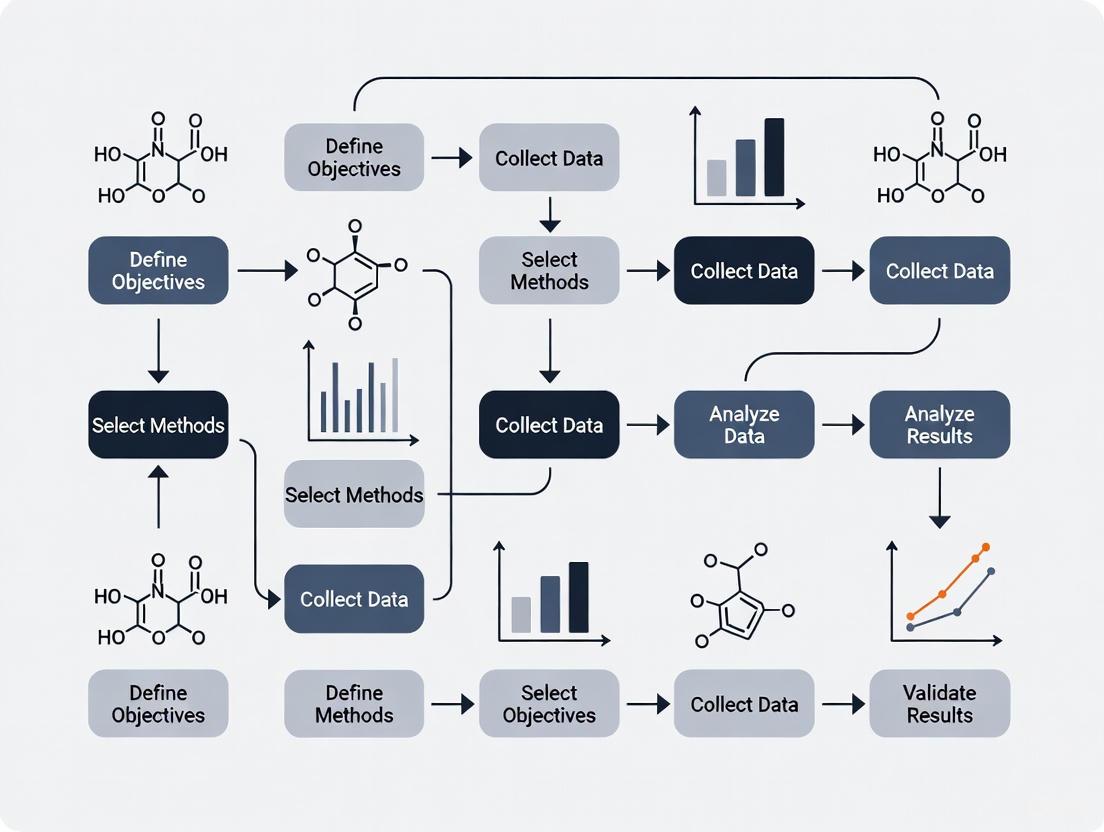

A well-designed experiment is essential for obtaining reliable estimates of systematic error. Key factors to consider are detailed below, and the overall workflow is summarized in the following diagram.

Selection of the Comparative Method

The choice of comparative method is paramount, as the interpretation of the experimental results hinges on the assumptions made about its correctness [1].

- Reference Method: The ideal comparative method is a reference method, a high-quality method whose correctness is well-documented through comparison with definitive methods and traceable reference materials [1]. When such a method is used, any observed differences are attributed to the test method.

- Routine Method: In many cases, a routine laboratory method serves as the comparative method. Its correctness may not be as rigorously documented [1]. If large and medically unacceptable differences are found, it becomes necessary to conduct additional experiments (e.g., recovery or interference studies) to identify which method is inaccurate.

Selection and Handling of Specimens

The quality of specimens used directly impacts the quality of the error estimates [1].

- Number of Specimens: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended [1]. The primary goal is to cover the entire working range of the method. Twenty carefully selected specimens covering a wide concentration range often provide better information than a hundred random specimens.

- Concentration Range: Specimens should be selected to provide results across the entire analytical range, from low to high values [1]. This is critical for reliably estimating proportional error using regression statistics.

- Stability and Handling: Specimens should generally be analyzed by both methods within two hours of each other to prevent degradation from causing observed differences [1]. Stability can be improved by refrigeration, freezing, or adding preservatives. A standardized handling procedure is essential prior to beginning the study.

Measurement Protocol and Timeline

The protocol must be designed to minimize the impact of extraneous variables.

- Replication: Common practice is single measurement by each method, but duplicate measurements are advantageous [1]. Duplicates act as a check for sample mix-ups, transcription errors, or other mistakes that could invalidate individual data points.

- Time Period: The experiment should be conducted over several days to minimize bias from a single analytical run. A minimum of 5 days is recommended, and the study can be extended over a longer period (e.g., 20 days) with only 2-5 specimens analyzed per day [1].

Data Analysis and Estimation of Systematic Error

Graphical Inspection of Data

The first step in data analysis is always to graph the results for visual inspection. This should be done while data is being collected to identify and immediately rectify any discrepant results.

- Difference Plot: When the two methods are expected to show one-to-one agreement, a difference plot (Bland-Altman-type plot) is used. The difference between the test and comparative method results (test - comparative) is plotted on the y-axis against the comparative method result on the x-axis [1]. The points should scatter randomly around the zero line. This plot readily reveals constant bias and can highlight concentrations where bias changes.

- Comparison Plot (Scatter Plot): For methods not expected to agree one-to-one, a scatter plot is used. The test method result (Y) is plotted against the comparative method result (X) [1]. A visual line of best fit can be drawn to show the relationship, helping to identify outliers and visualize proportional and constant error.

Statistical Calculation of Systematic Error

Statistical calculations provide numerical estimates of the systematic error. The appropriate statistical approach depends on the concentration range of the data.

For a Wide Analytical Range (e.g., glucose, cholesterol) - Linear Regression: Linear regression (least squares analysis) is used to calculate the slope (b) and y-intercept (a) of the line of best fit, along with the standard deviation of the points about the line (s~y/x~) [1]. The systematic error (SE) at a specific medical decision concentration (X~c~) is calculated as:

Y~c~ = a + bX~c~SE = Y~c~ - X~c~- Y-intercept (a): Estimates the constant systematic error.

- Slope (b): Estimates the proportional systematic error. A slope of 1.0 indicates no proportional error.

- Correlation coefficient (r): Is mainly useful for verifying that the data range is wide enough to provide reliable estimates of the slope and intercept. A value ≥ 0.99 is desirable [1].

For a Narrow Analytical Range (e.g., sodium, calcium) - Average Difference (Bias): When the concentration range is narrow, it is often best to calculate the average difference (bias) between the two methods [1]. This is typically derived from a paired t-test calculation, which also provides the standard deviation of the differences and a t-value to assess the statistical significance of the bias.

Table: Key Statistical Measures in Comparison of Methods

| Statistical Measure | Interpretation | Role in Estimating Systematic Error |

|---|---|---|

| Y-Intercept (a) | The value of Y when X is zero. | Estimates the constant systematic error. |

| Slope (b) | The change in Y for a one-unit change in X. | Estimates the proportional systematic error. |

| Standard Error of the Estimate (s~y/x~) | The standard deviation of the points around the regression line. | Quantifies the random scatter, which includes random error and any non-linear bias. |

| Average Difference (Bias) | The mean of (Test Result - Comparative Result). | Provides a single estimate of the average systematic error across the narrow range studied. |

Essential Reagents and Materials for a Comparison Study

The following table details key materials required for a robust comparison of methods experiment, particularly in a pharmaceutical or clinical chemistry context.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Characterized Patient Specimens | Serve as the core test material, providing a matrix-matched and clinically relevant sample for comparison across the analytical range [1]. |

| Reference Method Materials | Include calibrators and reagents for a well-defined comparative method to which the test method is benchmarked [1]. |

| Test Method Calibrators | Materials used to calibrate the new method under evaluation, ensuring it is operating according to its specified protocol. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pools | Samples with known (or assigned) values analyzed at intervals throughout the study to monitor the stability and performance of both the test and comparative methods over time. |

| Stabilizing Reagents | Preservatives or additives used to ensure analyte stability in specimens during the testing period, preventing degradation from being misinterpreted as systematic error [1]. |

Advanced Applications and Regulatory Context

The principles of method comparison extend beyond initial validation. In the pharmaceutical industry, analytical method comparability studies are critical for managing changes to analytical methods after a drug product has been approved [7]. This is a key part of Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) changes. A risk-based approach is recommended, where the extent of the comparability study (e.g., side-by-side comparison of results vs. a full statistical equivalency study) depends on the significance of the method change [7]. For instance, changing a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method to ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) for speed and efficiency would require demonstrating that the new method provides equivalent performance for critical attributes like assay and impurity profiles [7].

Furthermore, a holistic approach to validation integrates the concept of measurement uncertainty [3]. This is a parameter that characterizes the dispersion of values that could reasonably be attributed to the measurand, and it incorporates both random and systematic error components [8] [3]. The data generated from a carefully designed comparison of methods experiment is fundamental to quantifying the measurement uncertainty of the test method, ultimately ensuring that it is fit for its intended purpose.

In analytical method validation research, demonstrating that a new or altered method produces reliable and accurate results is paramount. This process fundamentally relies on comparing the candidate method against a benchmark. The choice of this benchmark—specifically, whether it is a Reference Method or a Comparative Method—critically influences the design, interpretation, and regulatory acceptance of the validation study. A Reference Method provides a definitive anchor with established accuracy, whereas a Comparative Method serves as a practical benchmark whose own correctness may not be fully documented [1]. Within the framework of a broader thesis on analytical method validation, understanding this distinction is not merely academic; it dictates the experimental protocol, the statistical analysis, and the justifiability of conclusions regarding a method's suitability for its intended purpose, such as ensuring drug safety and efficacy [7].

This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of the critical differences between Comparative and Reference Methods. It is structured to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select the appropriate benchmark, design rigorous comparison experiments, and apply correct data analysis techniques to draw defensible conclusions about their analytical methods.

Defining the Core Concepts

Reference Method

A Reference Method is an analytical procedure that has been rigorously validated and whose results are known to be correct through established traceability. The key characteristic of a reference method is its documented correctness, often established through comparison with an authoritative "definitive method" or via certified Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) [1]. Results from a reference method are considered to be the "true value" for the purpose of the comparison study. Consequently, any observed differences between the test method and the reference method are attributed to errors in the test method. These methods are typically characterized by high specificity, accuracy, and precision, and are often developed and maintained by national or international standards organizations [9].

Comparative Method

A Comparative Method is a more general term for any method used as a benchmark in a comparison study. It does not inherently carry the implication of documented, definitive accuracy. In most routine laboratory settings, the benchmark is a comparative method—often the existing routine method in use [1]. The interpretation of results is less straightforward than with a reference method. If differences between the test and comparative methods are small and medically or analytically acceptable, the two methods are considered to have comparable performance. However, if differences are large, additional experimentation is required to determine which method is producing the inaccurate results, as the error cannot be automatically assigned to the test method [1].

The following table summarizes the key distinctions between these two benchmarks:

| Feature | Reference Method | Comparative Method (Routine Method) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A method with rigorously documented correctness and traceability [1]. | A general term for any method used for comparison; its correctness is not necessarily documented [1]. |

| Assumption | Results are the "true value." [1] | Results are a "practical benchmark." |

| Interpretation of Differences | Differences are attributed to error in the test method [1]. | Differences must be interpreted carefully; large discrepancies require investigation to identify the source of error [1]. |

| Common Use Cases | Definitive validation studies; establishing traceability; certifying reference materials [9]. | Most routine method change studies in laboratories (e.g., HPLC to UHPLC transitions) [7]. |

| Regulatory Burden | Typically higher, as the reference method itself must be justified. | Can be lower, but requires robust statistical demonstration of equivalence. |

Experimental Design for Method Comparison

A well-designed experiment is the foundation of a reliable method comparison. Key factors must be considered to ensure the results are meaningful and representative of real-world performance.

Sample Selection and Size

The quality of patient specimens or samples is more critical than sheer quantity. However, a sufficient number is needed to ensure statistical power and to identify potential interferences.

- Number of Specimens: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is widely recommended, with 100-200 being preferable to fully assess specificity and identify matrix-related interferences [1] [10].

- Concentration Range: Specimens should be carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method, including critical medical decision concentrations [1] [10].

- Sample Quality: Specimens should represent the expected spectrum of diseases and conditions encountered in routine practice. They should be analyzed within a stable period, ideally within two hours of each other by both methods, to avoid degradation [1].

Data Collection Protocol

The protocol should mimic routine conditions while controlling for variables that could confound results.

- Replication: While single measurements are common, performing duplicate measurements in different analytical runs or in a randomized order is highly advantageous. Duplicates act as a validity check for individual methods and help identify sample mix-ups or transcription errors [1].

- Timeframe: The experiment should be conducted over several different analytical runs and a minimum of 5 days. Extending the study over a longer period, such as 20 days, helps minimize systematic errors that might occur in a single run and provides a more realistic estimate of long-term performance [1].

- Randomization: The sample sequence should be randomized to avoid carry-over effects and systematic bias [10].

Data Analysis and Statistical Approaches

The goal of data analysis is to identify, quantify, and judge the acceptability of systematic error (bias). A combination of graphical and statistical methods is essential.

Graphical Analysis: The First Step

Graphical inspection of the data should be performed as the data is collected to identify discrepant results for immediate re-analysis [1] [10].

- Scatter Plot: This plot displays the test method results (y-axis) against the comparative/reference method results (x-axis). It is excellent for showing the analytical range, linearity, and the general relationship between the methods. A line of identity (y=x) is often drawn; deviations from this line suggest bias [1] [10].

- Difference Plot (Bland-Altman Plot): This is a powerful tool for assessing agreement. The difference between the test and comparative method (y-axis) is plotted against the average of the two methods or the value of the comparative method (x-axis). This plot readily reveals the magnitude of differences, any systematic bias (the average difference), and whether the variability of differences is constant across the measuring range [1] [10] [11].

Statistical Calculations for Quantifying Error

While graphs provide a visual impression, statistical calculations put exact numbers on the observed errors.

- Linear Regression Analysis: For data covering a wide analytical range (e.g., glucose, cholesterol), linear regression is preferred. It provides statistics for the slope (b) and y-intercept (a) of the line of best fit, and the standard deviation of the points about that line (s~y/x~) [1].

- The slope indicates a proportional error.

- The y-intercept indicates a constant error.

- The systematic error (SE) at any critical decision concentration (X~c~) is calculated as: SE = Y~c~ - X~c~, where Y~c~ = a + bX~c~ [1].

- Correlation Coefficient (r): The correlation coefficient is mainly useful for assessing whether the range of data is wide enough to provide reliable estimates of the slope and intercept. A value of r ≥ 0.99 is generally considered acceptable for this purpose. It should not be used to judge the acceptability of the method, as high correlation can exist even with significant bias [1] [10].

- Paired t-test / Average Difference (Bias): For analytes with a narrow analytical range (e.g., sodium, calcium), it is often best to simply calculate the average difference between the two methods, also known as the bias. This is typically derived from a paired t-test, which also provides a standard deviation of the differences [1].

The following table outlines the core statistical measures used and their interpretation:

| Statistical Measure | What It Estimates | Interpretation in Method Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Slope (b) | Proportional difference between methods. | A slope of 1.00 indicates no proportional error. A slope of 1.05 indicates a 5% proportional error. |

| Y-Intercept (a) | Constant difference between methods. | An intercept of 0.0 indicates no constant error. A positive intercept indicates the test method consistently reads higher by that amount. |

| Standard Error of the Estimate (s~y/x~) | Random variation around the regression line. | A measure of the average scatter of the data points around the line of best fit. |

| Average Difference (Bias) | Systematic error averaged over all samples. | A positive value indicates the test method, on average, reads higher than the comparative method. |

| Standard Deviation of Differences | Dispersion of the individual differences. | Used to calculate the Limits of Agreement in a Bland-Altman plot (Mean Difference ± 1.96 SD) [11]. |

Essential Tools and Reagents for a Method Comparison Study

A successful method comparison study relies on more than just a protocol. The following toolkit is essential for execution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Method Comparison |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Patient Samples | The core of the study, providing a real-world matrix to assess method performance across a wide concentration range and disease spectrum [1] [10]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used to verify the accuracy of a Reference Method or to help troubleshoot large biases identified with a Comparative Method. Provides a traceable link to a standard [1]. |

| Stable Quality Control Materials | Used to monitor the precision and stability of both the test and comparative methods throughout the data collection period, ensuring both systems are in control. |

| Calibrators for Both Methods | Essential for ensuring that each instrument is properly calibrated according to its own specific procedure, a prerequisite for a valid comparison. |

| Appropriated Specimen Collection Tubes | To ensure specimen integrity. The type of anticoagulant or preservative must be appropriate for both analytical methods. |

| Data Analysis Software | Software capable of performing advanced statistical analyses (e.g., linear regression, Bland-Altman plots, Deming/Passing-Bablok regression) and generating high-quality graphs is indispensable [10] [11] [12]. |

| Ki16425 | Ki16425, CAS:355025-24-0, MF:C23H23ClN2O5S, MW:475.0 g/mol |

| L-167307 | L-167307, CAS:188352-45-6, MF:C22H17FN2OS, MW:376.4 g/mol |

Regulatory and Practical Considerations in the Pharmaceutical Industry

In regulated environments like drug development, method changes are common, and demonstrating comparability is a key requirement.

- Risk-Based Approach: Regulatory guidance on method comparability is not always explicit, leading to a risk-based approach in the pharmaceutical industry. The extent of the comparability study depends on the impact of the method change [7]. A minor change (e.g., within robustness parameters of an HPLC method) may not require a full equivalency study, whereas a major change (e.g., a different separation mechanism) typically will [7].

- Equivalency vs. Comparability: The terms are sometimes differentiated. Analytical method equivalency may refer specifically to a formal statistical study to demonstrate that two methods generate equivalent results for the same sample, while analytical method comparability is a broader term that includes the evaluation of all method performance characteristics (accuracy, precision, specificity, etc.) [7].

- Documentation: A successful regulatory submission for a method change typically includes the reason for the change, complete validation data for the new method, and a side-by-side comparability/equivalency study data package [7].

The distinction between a Reference Method and a Comparative Method is a critical conceptual foundation in analytical method validation. A Reference Method acts as a definitive anchor, allowing for unambiguous assignment of error to the test method. In contrast, a Comparative Method provides a practical benchmark, requiring careful interpretation of differences and potentially further investigation to identify the source of error. The choice between them dictates the experimental design, from sample selection and replication to the statistical analysis of systematic error using regression or bias calculations.

A rigorous method comparison study, employing both graphical techniques and appropriate statistics, is not merely a regulatory checkbox. It is a scientific exercise that ensures the continued quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products by guaranteeing that analytical methods—the tools used to make critical decisions—are providing trustworthy and reliable results.

In analytical method validation, accurate identification and quantification of systematic error is fundamental to establishing method suitability and ensuring data integrity in drug development. Systematic errors, which consistently alter results from true values, manifest primarily as constant or proportional errors. This guide provides a technical framework for differentiating between these error types within Comparison of Methods (COM) experiments, a critical component of analytical method validation. We detail experimental protocols for error detection, statistical methodologies for quantification, and practical strategies for error mitigation, providing researchers and scientists with the tools necessary to enhance the reliability of analytical measurements in pharmaceutical development.

In the context of analytical method validation, a comparative method is used to estimate the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new test method [1]. Systematic error is defined as the difference between a measured value and the unknown true value of a quantity that occurs consistently in the same direction [13] [14]. Unlike random errors, which vary unpredictably and can be reduced by averaging repeated measurements, systematic errors affect all measurements predictably and are not eliminated through replication [5] [14]. This consistent bias makes systematic error particularly problematic in analytical chemistry and drug development, where it can compromise method validity and lead to incorrect conclusions about drug quality, safety, and efficacy.

The Comparison of Methods (COM) experiment serves as the primary approach for assessing systematic error using real patient specimens [1]. In this framework, differences between a test method and a carefully selected comparative method are attributed to the test method, especially when a reference method with documented correctness is used [1]. Systematic errors are clinically significant when they exceed acceptable limits at critical medical decision concentrations, potentially impacting patient diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and therapeutic drug monitoring [1].

Systematic errors are primarily categorized as constant or proportional, a distinction crucial for diagnosing their source and implementing appropriate corrections [1] [13]. A constant error persists as a fixed value regardless of the analyte concentration, while a proportional error changes in magnitude proportionally to the analyte concentration [13]. Understanding this distinction enables researchers to determine whether a method requires recalibration at the zero point (to address constant error) or across the analytical range (to address proportional error), ultimately ensuring the method's fitness for its intended purpose in pharmaceutical analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Error Types

Characterization of Systematic vs. Random Error

Measurement error is an inherent aspect of all analytical procedures and can be classified into two primary categories: systematic error and random error [14]. The table below summarizes their fundamental characteristics:

Table 1: Characteristics of Systematic and Random Error

| Characteristic | Systematic Error | Random Error |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Consistent, directional bias in measurements [5] | Unpredictable fluctuations in measurements [5] |

| Cause | Imperfect calibration, instrumental faults, flawed methods [5] [13] | Electronic noise, environmental fluctuations, procedural variations [5] [14] |

| Directional Effect | Always alters results in the same direction [15] [14] | Affects results in both positive and negative directions equally [14] |

| Impact on Results | Affects accuracy (closeness to true value) [14] | Affects precision (reproducibility of measurements) [5] [14] |

| Statistical Mitigation | Not reduced by averaging multiple measurements [14] | Reduced by averaging multiple measurements [14] |

| Detectability | Can be difficult to detect without reference materials [13] | Revealed by variability in repeated measurements [13] |

Differentiating Constant and Proportional Systematic Errors

Systematic errors are further differentiated based on their relationship with the concentration of the analyte being measured.

Constant Error (Offset Error): This error remains fixed in magnitude across the analytical measurement range [13] [14]. It represents a consistent offset or displacement from the true value. A common example is a zero setting error, where an instrument does not read zero when the quantity to be measured is zero [5] [13]. For instance, a balance that consistently reads 1.5 mg when nothing is placed on it introduces a constant error of +1.5 mg to every measurement.

Proportional Error (Scale Factor Error): This error's magnitude changes in proportion to the true value of the analyte concentration [13] [14]. It arises from a multiplicative factor rather than an additive one. An example is a multiplier error in which the instrument consistently reads changes in the quantity greater or less than the actual changes [5]. For example, if a method has a 2% proportional error and the true value is 200 mg/dL, the measured value will be 204 mg/dL (error of +4 mg/dL); if the true value is 100 mg/dL, the measured value will be 102 mg/dL (error of +2 mg/dL) [13].

Complex Errors: In practice, methods often exhibit a combination of both constant and proportional errors. The total systematic error at any given concentration is the sum of the constant error and the proportional error at that concentration [1].

Experimental Design for Error Differentiation

The Comparison of Methods Experiment

The Comparison of Methods (COM) experiment is the cornerstone for estimating systematic error in method validation [1]. The purpose is to analyze patient samples by both a new test method and a comparative method, then estimate systematic errors based on the observed differences [1].

Key Experimental Factors:

Comparative Method Selection: Ideally, a reference method with documented correctness through definitive method comparison or traceable standard materials should be used. Differences are then attributed to the test method [1]. When using a routine comparative method, large, medically unacceptable differences require additional experiments to identify the inaccurate method [1].

Specimen Requirements: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended, selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the expected disease spectrum [1]. Specimen quality and concentration range are more critical than sheer quantity, though 100-200 specimens may be needed to assess method specificity [1].

Replication and Timing: Analysis should be performed in duplicate across multiple runs over at least 5 days to minimize systematic errors from a single run and identify sample-specific issues [1].

Specimen Stability: Specimens should be analyzed within two hours of each other by both methods unless stability data supports other handling conditions. Proper handling is critical to prevent differences due to specimen degradation rather than analytical error [1].

Data Analysis and Graphical Interpretation

Initial Graphical Inspection: Graphing data as it is collected allows for visual error assessment and identification of discrepant results needing confirmation [1].

Difference Plot: For methods expected to show 1:1 agreement, a difference plot (test result minus comparative result on the y-axis versus comparative result on the x-axis) is ideal. Differences should scatter randomly around the zero line. Consistent deviations above or below zero at certain concentrations suggest systematic error [1].

Comparison Plot (Scatter Plot): For methods not expected to show 1:1 agreement, a scatter plot (test result on y-axis versus comparative result on x-axis) is used. A visual line of best fit reveals the general relationship, helping identify outliers and the nature of systematic error [1].

Statistical Analysis for Error Quantification: For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression analysis (least squares) is preferred to estimate systematic error at medically important decision concentrations and determine the constant and proportional components [1].

The regression line is defined as: ( Yc = a + bXc ), where:

- ( Yc ) = Value estimated by the test method at decision concentration ( Xc )

- ( a ) = Y-intercept (estimates constant error)

- ( b ) = Slope (estimates proportional error)

- ( X_c ) = Medical decision concentration

The systematic error (SE) at the decision concentration is calculated as: ( SE = Yc - Xc ) [1].

Table 2: Interpretation of Linear Regression Parameters in Error Analysis

| Regression Parameter | Mathematical Representation | Interpretation in Error Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Slope (b) | ( b = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(Xi - \bar{X})(Yi - \bar{Y})}{\sum{i=1}^{n}(X_i - \bar{X})^2} ) | Deviation from 1.0 indicates proportional error. |

| Y-Intercept (a) | ( a = \bar{Y} - b\bar{X} ) | Deviation from 0 indicates constant error. |

| Standard Error of Estimate (sâ‚/â‚“â‚Ž) | ( s{y/x} = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(Yi - \hat{Y}i)^2}{n-2}} ) | Measures random dispersion around the regression line. |

The correlation coefficient (r) is primarily useful for assessing whether the data range is sufficiently wide to provide reliable slope and intercept estimates, not for judging method acceptability. An r value ≥ 0.99 suggests reliable regression estimates [1].

For narrow concentration ranges, calculating the average difference (bias) between methods using a paired t-test is often more appropriate than regression analysis [1].

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing a COM experiment, analyzing data, and differentiating error types using the statistical approaches described.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instrumental solutions essential for conducting robust Comparison of Methods experiments and systematic error analysis in pharmaceutical method validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for COM Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Technical Specification Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides traceable standards for calibration and accuracy assessment; crucial for identifying systematic error. | Purity certification, metrological traceability, stability documentation. |

| Patient-Derived Specimens | Matrix-matched samples for realistic method comparison across clinical decision levels. | Cover pathological range, appropriate stability, informed consent. |

| Ultra-Pure Water & Solvents | Sample preparation, dilution, and mobile phase preparation for chromatographic methods. | Specified grade (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS), low organic/particulate content. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalizes variation in sample preparation and analysis; improves precision and accuracy in LC-MS. | High isotopic purity, co-elution with analyte, minimal matrix effects. |

| Calibration Verification Materials | Independent materials not used in calibration to verify method accuracy post-calibration. | Commutability with patient samples, target values with uncertainty. |

| UFLC-DAD System | High-separation efficiency analysis for specificity/selectivity assessment in complex matrices. | Detector linearity, pressure limits, injection precision, DAD spectral resolution. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Economical quantitative analysis; used for accuracy and linearity assessment where applicable. | Wavelength accuracy, photometric linearity, stray light specification. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Performs linear regression, t-tests, ANOVA, and calculates measurement uncertainty. | Validated algorithms, GMP/GLP compliance features, audit trail capability. |

| Kopsinine | Kopsinine, CAS:559-51-3, MF:C21H26N2O2, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KPT-6566 | RORγ Inverse Agonist|2-[[4-[[[4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]imino]-1-oxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthyl]thio]acetic Acid | 2-[[4-[[[4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]imino]-1-oxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthyl]thio]acetic Acid is a potent RORγ inverse agonist for autoimmune disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Statistical Analysis and Error Quantification

Advanced Regression Analysis

While simple linear regression is commonly used in COM studies, advanced regression techniques may be necessary when certain assumptions are violated. Deming regression and Passing-Bablok regression account for measurement error in both methods, providing more reliable estimates of constant and proportional error when the comparative method is not a definitive reference method. These methods are particularly valuable when the correlation coefficient (r) is less than 0.99, indicating a narrow data range relative to method imprecision [1].

Total Error Approach

Modern method validation emphasizes a total error approach, which combines both systematic error (bias) and random error (imprecision) to assess overall method suitability [16]. This approach acknowledges that both error types impact the usefulness of analytical results. Statistical tolerance intervals that cover a specified proportion (beta) of future measurements with a defined confidence level are used to ensure the total error remains within acceptable limits at critical decision concentrations [16]. This framework formally controls the risk of accepting unsuitable analytical methods, unlike traditional ad-hoc acceptance criteria [16].

Error Propagation in Calculations

Understanding how constant and proportional errors propagate through calculations is essential. The rules of error propagation demonstrate that:

- For addition/subtraction, absolute errors (characteristic of constant error) are added [15].

- For multiplication/division, relative or percentage errors (characteristic of proportional error) are added [15].

- For powers, the relative error is multiplied by the power [15].

These principles allow researchers to predict how errors in raw measurements will affect final calculated results in pharmaceutical analysis.

Case Study: Error Analysis in Pharmaceutical Validation

A recent study comparing Ultra-Fast Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector (UFLC−DAD) and spectrophotometric methods for quantifying metoprolol tartrate (MET) in tablets provides a practical example of systematic error assessment in pharmaceutical method validation [17].

Experimental Protocol:

- Methods Compared: UFLC−DAD (test method) and UV spectrophotometry (comparative method).

- Analyte: Metoprolol tartrate extracted from commercial 50 mg and 100 mg tablets.

- Validation Parameters: Specificity/selectivity, sensitivity, linearity, range, accuracy, precision, and robustness were assessed for both methods [17].

- Statistical Analysis: ANOVA and Student's t-test at 95% confidence level were used to compare results from both methods [17].

Results and Error Interpretation: The UFLC−DAD method demonstrated superior specificity and could analyze both 50 mg and 100 mg tablets, while the spectrophotometric method was limited to 50 mg tablets due to concentration limitations [17]. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the methods for the 50 mg tablets, indicating that systematic error between the methods was not statistically or medically significant for this formulation [17]. This finding validates the use of the simpler, more economical spectrophotometric method for quality control of the 50 mg tablets, demonstrating how COM studies can guide resource-efficient analytical practices without compromising data quality.

Mitigation Strategies for Systematic Errors

Reducing Constant Error

- Regular Calibration: Frequently compare instrument readings with known standard quantities, particularly at zero concentration, to identify and correct offset errors [13] [14].

- Method of Standard Additions: This technique accounts for constant matrix effects that may cause interference by adding known amounts of analyte to the sample [13].

- Blank Correction: Consistently measure and subtract the blank signal from all sample measurements to eliminate constant background interference [13].

Reducing Proportional Error

- Calibration Across Working Range: Use multiple calibration standards across the entire analytical measurement range to establish a proper response curve and correct for proportional effects [13].

- Internal Standardization: Use internal standards that closely mimic the analyte's behavior to correct for proportional losses during sample preparation or analysis [17].

- Instrument Linearity Verification: Regularly verify that instrument response is proportional to analyte concentration throughout the claimed working range [17].

General Approaches for Both Error Types

- Method Triangulation: Use multiple analytical techniques or instruments to measure the same samples; consistent differences suggest systematic error in one method [14].

- Participate in Proficiency Testing: Analyze external quality control samples with values assigned by reference methods to identify unrecognized systematic error [1].

- Robustness Testing: Deliberately vary key method parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, mobile phase composition) during validation to identify sources of systematic error before routine use [17].

Differentiating between constant and proportional systematic error is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity in analytical method validation for drug development. Through carefully designed Comparison of Methods experiments, appropriate statistical analysis, and informed interpretation of regression parameters, researchers can accurately characterize the nature and magnitude of systematic error. This understanding directly informs effective mitigation strategies, ensuring that analytical methods produce reliable, accurate data suitable for regulatory submission and quality control. As the pharmaceutical industry advances with increasingly complex therapeutics, robust error analysis remains fundamental to demonstrating method suitability, ultimately protecting patient safety and ensuring drug efficacy.

In the tightly regulated pharmaceutical environment, the comparative method is a critical, structured process for evaluating the performance of a new or modified analytical procedure against an established one. This methodology is foundational to ensuring that data generated for product quality attributes remains reliable, consistent, and defensible when analytical methods evolve. Framed within a broader thesis on analytical method validation research, the comparative method is not a standalone validation activity but an integral component of a holistic Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management strategy [18]. Its core function is to provide a scientific and statistical basis for concluding whether a new method can successfully replace an existing one without compromising the quality, safety, or efficacy assessment of the drug product.

The need for comparative studies arises from the dynamic nature of drug development and manufacturing. Changes are inevitable, whether driven by technology upgrades (e.g., transitioning from HPLC to UHPLC), process improvements, or regulatory updates [18]. In such cases, simply validating the new method according to regulatory guidelines like ICH Q2 is necessary but insufficient. Validation demonstrates that a method is capable of performing as intended for its new, isolated application. In contrast, a comparative study demonstrates that the new method performs equivalently to, or better than, the legacy method that was used to generate the original stability and specification data [7]. This direct comparison is what underpins the continuity of data packages submitted to regulatory agencies and ensures that patient safety is protected through consistent product quality monitoring.

Conceptual Framework: Comparability vs. Equivalency

Within the sphere of the comparative method, a crucial distinction exists between "comparability" and "equivalency." These terms are often used interchangeably, but they represent distinct concepts with different regulatory implications, as highlighted in industry discussions and regulatory guidance [18] [7].

Analytical Method Comparability: This is a broader evaluation to determine if a modified method yields results that are sufficiently similar to the original method to ensure consistent product quality. It is typically employed for lower-risk procedural changes where the fundamental methodology remains largely unchanged. A successful comparability study confirms that the modified procedure produces the expected results and that product quality decisions remain unaffected. These changes often fall under internal change control and may not require immediate regulatory filings [18].

Analytical Method Equivalency: This is a more rigorous, formal subset of comparability. It involves a comprehensive assessment, often requiring full validation of the new method, to demonstrate that a replacement method performs equal to or better than the original. Equivalency studies are necessary for high-risk changes, such as replacing a method with one based on a completely different separation mechanism or detection technique. Such changes require regulatory approval prior to implementation [18] [7].

The International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (IQ) working group further refined this distinction, noting that "equivalency" may be restricted to a formal statistical study to evaluate similarities in method performance characteristics or the results generated for the same samples [7].

Table 1: Distinguishing Between Comparability and Equivalency

| Feature | Comparability | Equivalency |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Broader evaluation of method performance | Formal, statistical demonstration of equivalence |

| Risk Level | Low to Moderate | High |

| Typical Triggers | Minor modifications within the method's design space | Replacement of a method; major changes to methodology |

| Regulatory Impact | Often managed via internal change control; may not require a immediate filing | Requires prior regulatory approval |

| Study Rigor | May leverage prior knowledge and robustness data | Requires a comprehensive side-by-side study, often with full validation of the new method |

Visualizing the Decision Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for determining when and how to implement a comparative method study within a risk-based framework.

Regulatory Landscape and Current Industry Practice

Despite its critical importance, the regulatory landscape for analytical method comparability is less clearly defined than for initial method validation. While clear guidelines like ICH Q2(R2) exist for validation, specific guidance on how or when to perform comparability or equivalency studies is sparse [7]. Regulatory documents, such as the FDA's 2003 draft guidance on Comparability Protocols, indicate that the need for and extent of an equivalency study depends on the proposed change, product type, and the test itself [7]. This lack of prescriptive detail has led to a wide range of practices across the pharmaceutical industry.

A survey conducted by the IQ Consortium revealed several key insights into current industry practices concerning HPLC assay and impurities methods [7]:

- 68% of participants viewed "comparability" and "equivalency" as two different concepts.

- 79% of companies lacked specific standard operating procedures (SOPs) dedicated to analytical method comparability, though over half addressed it within general change control policies.

- 47% of participants had received questions from health authorities on comparability packages, indicating regulatory scrutiny in this area.

- 100% of participants evaluated the need for a comparability or equivalency study when a method change was made, with 63% using a risk-based approach to determine its necessity.

Table 2: Industry Practices for Method Comparability (Based on IQ Survey)

| Practice Area | Survey Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Terminology Understanding | 68% distinguish between comparability and equivalency | Industry recognizes a nuanced, risk-based approach. |

| Internal Governance | 79% lack specific SOPs for comparability | Practices are often decentralized or embedded in other procedures. |

| Regulatory Scrutiny | 47% have received regulatory questions | Agencies are actively reviewing comparability justifications. |

| Risk-Based Application | 63% do not require studies for all changes | A risk-based approach is widely adopted for efficiency. |

The introduction of ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development formalizes a more structured, lifecycle approach. It encourages a science- and risk-based framework for developing, validating, and managing analytical procedures, which inherently includes managing changes through comparability and equivalency studies [18]. A harmonized industry approach, as championed by groups like the IQ Consortium, can reduce regulatory filing burdens and encourage the adoption of innovative analytical technologies.

Designing a Method-Comparison Study: Detailed Experimental Protocols

A well-designed method-comparison study is paramount for generating defensible data. The core principle is that the two methods must measure the same underlying quality attribute (e.g., assay potency or impurity content) [19]. The following protocols detail the key experiments for a robust comparability/equivalency study.

Protocol for Sample Analysis and Data Collection

The foundation of any comparison is the direct, side-by-side testing of samples using both the original and new methods [18].

1. Objective: To generate paired data sets from both methods that represent the expected range of the product's quality attributes.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Representative Drug Substance/Product Samples: A minimum of three independent batches is recommended to capture product and process variability [7]. These should include lots that span the expected manufacturing range (e.g., from low to high potency if possible).

- Reference Standards: Qualified and traceable reference standards for the analyte of interest.

- Mobile Phases/Reagents: Prepared according to both the old and new analytical procedures.

3. Procedure:

- Prepare samples and standards according to both methods' procedures.

- Analyze all selected sample batches using both the original method and the new method.

- The order of analysis should be randomized to avoid systematic bias (e.g., time-based degradation of samples or reagents) [19].

- For each sample, the two analyses should be performed as closely in time as possible ("simultaneous sampling") to ensure the analyte has not changed [19].

- A sufficient number of replicate injections per sample should be performed to allow for a meaningful assessment of precision.

Protocol for Statistical Evaluation and Data Interpretation

Once paired data is generated, statistical tools are used to quantify the agreement between the two methods.

1. Objective: To statistically determine the bias and the limits of agreement between the original and new methods.

2. Methodology:

- Data Pairing: For each sample, record the result from the original method (Method A) and the new method (Method B). The unit of analysis is the difference between the paired results.

- Bland-Altman Analysis: This is a recommended statistical approach for method-comparison [19].

- Calculate the difference between the two methods for each pair (e.g., New Method - Original Method).

- Calculate the average of the two methods for each pair ([Method A + Method B]/2).

- Plot the differences (y-axis) against the averages (x-axis) to create a Bland-Altman plot.

- Calculate the bias (the mean of all the differences).

- Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of the differences.

- Determine the Limits of Agreement (LOA) as Bias ± 1.96 SD.

3. Interpretation:

- The bias indicates the systematic difference between the methods. A bias of zero means no average difference.

- The LOA defines the range within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are expected to lie.

- The clinical or quality impact is assessed by comparing the LOA to pre-defined acceptance criteria. These criteria should be based on the method's performance requirements and the product's Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [18] [19]. If the LOA falls entirely within a clinically or quality-acceptable range, the two methods can be considered equivalent.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key research reagent solutions and materials essential for conducting a method-comparison study for a chromatographic method.

Table 3: Essential Materials for a Method-Comparison Study

| Item | Function & Importance in Comparative Studies |

|---|---|

| Representative Sample Batches | Provides a matrix that captures real-world variability. Using multiple, independent batches is critical to demonstrate that equivalency holds across the product manufacturing range. |

| Qualified Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for quantifying the analyte in both methods. Ensures that any observed differences are due to the method and not the standard. |

| Method-Specific Mobile Phases & Buffers | Prepared exactly as specified in each procedure. Differences in pH, ionic strength, or organic composition can significantly impact chromatographic separation and results. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | Verifies that the chromatographic system (for each method) is performing adequately before the comparative analysis is initiated, ensuring data integrity. |

| Stability-Indicating Solutions | (e.g., stressed samples) May be used to demonstrate that the new method has equivalent or better ability to separate degradants from the main peak, a key aspect for stability-indicating methods. |

| L-669083 | L-669083, CAS:130007-52-2, MF:C29H29IN4O5S, MW:672.5 g/mol |

| KT5823 | KT5823, CAS:126643-37-6, MF:C29H25N3O5, MW:495.5 g/mol |

Integrating the comparative method into the overall validation plan requires a proactive, risk-based strategy. The principles of Quality by Design (QbD) should be applied from the method development stage. This involves defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) which outlines the required performance characteristics of the method [18]. A well-developed method, with a understood design space established through robustness testing, is inherently more manageable when changes become necessary. A change within the method's design space might only require a comparability assessment, while a change outside the design space would likely trigger a full equivalency study [18] [7].

The risk assessment should consider:

- Impact on Product Quality: The criticality of the test method to the determination of product CQAs.

- Extent of the Change: A minor change (e.g., column dimensions within defined limits) is lower risk than a major change (e.g., a different chromatographic technique).

- Stage of Product Lifecycle: Changes post-approval are typically more stringently controlled than those during clinical development.

By embedding comparability and equivalency studies as formal components within the change management system, pharmaceutical companies can ensure that method improvements and technology transfers are executed efficiently, with maintained regulatory compliance and unwavering assurance of product quality and patient safety.

Executing a Comparison of Methods Study: Experimental Design and Analysis

Within the framework of comparative analytical method validation research, the principles of experimental design are paramount for generating reliable, reproducible, and defensible scientific data. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three foundational pillars of robust experimentation: determining specimen number (sample size), executing proper specimen selection, and ensuring specimen stability. In comparative studies, where the goal is to objectively evaluate the performance of one analytical method against another or against a standardized benchmark, a flawed design in any of these areas can compromise the entire validation process [20] [17]. A well-considered design not only controls for variability and bias but also ensures that the study is powered to detect scientifically meaningful differences, thereby upholding the integrity of the conclusions drawn regarding method equivalence, superiority, or compliance [21].

The following sections will dissect each of these core components, providing detailed methodologies, structured data presentation, and visual workflows tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and related fields.

Foundational Principles of Experimental Design

The statistical design of experiments is guided by several key principles that work in concert to enhance the validity and efficiency of research. These principles are critical for managing uncertainty and ensuring that observed effects are attributable to the variables under investigation rather than to confounding factors [21] [22].

- Replication: Repeating the experiment or measurements multiple times increases the reliability of the results and provides a more precise estimate of experimental error. Natural variability is always present; replication is essential for understanding this variability and for increasing the rigor of the findings [21].

- Randomization: The random assignment of treatments or specimens to experimental units is crucial for spreading unspecified and potential confounding variables evenly across all treatment groups. This process ensures the validity of statistical inference by mitigating biases that could arise from systematic differences between groups [21] [22]. For instance, in visual science, treatments might be randomly assigned to different groups of patients or the order of treatment might be randomized [21].

- Blocking: This technique involves grouping experimental units that are similar to one another (e.g., eyes from the same subject, animals from the same litter) into blocks. By comparing treatments within these homogenous blocks, the known but irrelevant sources of variation are reduced, leading to greater precision in estimating the treatment effects [21] [22].

- Multifactorial Design: Instead of varying one factor at a time, a more efficient approach is to study multiple factors simultaneously. This design allows for the investigation of interaction effects—where the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor—providing a more comprehensive understanding of the system [21].

- Sequential Approach: Dedicating only a portion of the overall research budget and plan to an initial experiment is a prudent strategy. The results from one experiment inform and refine the subsequent experimental steps, allowing for a more adaptive and efficient research process [21].

Specimen Number: Power and Sample Size

Determining the appropriate number of specimens, or sample size, is a critical step in the planning phase of any experiment. This process, known as a power analysis, ensures that the study has a high probability of detecting a treatment effect if one truly exists, thereby minimizing the risk of false-negative (Type II) errors [21].

The Importance of Power Analysis

A well-executed power analysis is essential for both practical and ethical reasons. An underpowered study (with too few specimens) may fail to uncover meaningful effects, wasting resources and potentially halting promising research avenues. Conversely, an overpowered study (with more specimens than necessary) can be a wasteful use of resources and may unnecessarily expose subjects to risk [21]. Furthermore, funding agencies and scientific journals now increasingly require rigorous power justifications to ensure that the proposed research is feasible and likely to yield interpretable results [21].

Key Factors Influencing Sample Size

The required sample size in an experiment is influenced by several interconnected factors, whose relationships are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Factors Affecting Sample Size Determination in Experimental Design

| Factor | Description | Relationship to Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | The probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis (typically set at 80% or higher). | Sample size increases with higher desired power [21]. |

| Effect Size | The magnitude of the difference or effect that is considered scientifically or clinically meaningful. | Sample size increases as the detectable difference becomes smaller [21]. |

| Measurement Variability | The inherent variance or standard deviation in the measured response. | Sample size increases proportionally to the variance [21]. |

| Type I Error (α) | The probability of incorrectly rejecting a true null hypothesis (false positive), often set at 0.05. | Sample size increases with a more stringent (smaller) α value [21]. |

| Test Directionality | Whether the statistical test is one-sided or two-sided. | Two-sided tests, which do not assume the direction of the effect, require a larger sample size than one-sided tests [21]. |

Conducting a Power Analysis

The process typically involves using specialized software (e.g., G*Power, Lenth's applets) to calculate the required sample size based on the anticipated effect size, estimated variability, and chosen levels for power and significance [21]. This analysis provides perspective on whether a well-designed experiment is feasible with the available resources and helps to formally justify the number of specimens included in the study.

Specimen Selection: Randomization and Blocking

The process of selecting and assigning specimens to experimental groups is as crucial as determining the total number. Proper methodology here directly controls for selection bias and confounding variables.

Randomization Techniques

Randomization is the cornerstone for ensuring the validity of causal inference. Several designs can be employed:

- Completely Randomized Design: Every experimental subject or specimen is assigned to a treatment group entirely at random, using tools like random number generators. This is the simplest form of randomization [23].

- Randomized Block Design: Also known as stratified random design, this approach involves first grouping specimens based on a shared characteristic (e.g., age, sex, baseline severity, batch of raw material) that is expected to influence the response. Random assignment to treatments is then performed within each of these blocks. This method controls for the known variability introduced by the blocking factor, leading to more precise comparisons [21] [23].

Between-Subjects vs. Within-Subjects Designs

The unit of assignment and measurement is another critical consideration in specimen selection.

- Between-Subjects Design: Each individual specimen or subject receives only one level of the experimental treatment. This design requires a larger total sample size to achieve the same power as a within-subjects design but avoids potential carryover effects [23].

- Within-Subjects Design: Each individual specimen or subject receives all experimental treatments consecutively, with their response measured for each. This design, also known as a repeated measures design, is highly efficient as it uses each subject as its own control, thereby eliminating variability between subjects and reducing the required sample size. Counterbalancing (randomizing the order of treatments) is essential in this design to control for order effects [21] [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Assignment Designs

| Feature | Between-Subjects Design | Within-Subjects Design |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Assignment | Each subject receives only one treatment. | Each subject receives all treatments. |

| Sample Size Requirement | Larger | Smaller |

| Key Advantage | Avoids carryover effects. | Controls for subject-to-subject variability; greater statistical power. |

| Key Consideration | Requires careful randomization to ensure group equivalence. | Requires counterbalancing to control for order effects. |

| Example | Subjects randomly assigned to either a control group or a single treatment group. | The same subject is measured for performance after receiving a placebo, a low dose, and a high dose of a drug, in a randomized order. |

Specimen Stability: Ensuring Data Integrity

In analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the stability of specimens and solutions is a critical component of method validation. It ensures that the analytical results obtained are an accurate reflection of the sample at the time of collection and are not artifacts of degradation during storage or processing [24].

Leading Principles of Stability Assessment

Stability in a bioanalytical context refers not only to the chemical integrity of the molecule but also to the constancy of the analyte concentration over time. This can be affected by solvent evaporation, adsorption to containers, precipitation, or changes in immunoreactivity for large molecules [24]. The core principle is that all conditions encountered during sample collection, storage, and processing must be demonstrated to ensure stability. The storage duration assessed during validation should be at least equal to the maximum anticipated storage period for any individual study sample [24].

Key Types of Stability Assessments

A comprehensive stability assessment covers all relevant conditions, as outlined in the table below.

Table 3: Key Stability Assessments in Bioanalytical Method Validation

| Stability Type | Description | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Bench-Top Stability | Evaluates analyte stability in the biological matrix at ambient temperature for the expected duration of sample processing. | Deviation from reference value ≤ 15% (chromatography) or ≤ 20% (ligand-binding assays) [24]. |

| Freeze/Thaw Stability | Assesses stability after multiple (e.g., 3-5) cycles of freezing and thawing. | Deviation from reference value ≤ 15% (chromatography) or ≤ 20% (ligand-binding assays) [24]. |

| Long-Term Frozen Stability | Determines stability in the biological matrix at the intended storage temperature (e.g., -20°C or -70°C). | Deviation from reference value ≤ 15% (chromatography) or ≤ 20% (ligand-binding assays) [24]. |

| Stock Solution Stability | Assesses stability of the analyte in stock solution under storage (e.g., refrigerated) and bench-top conditions. | Deviation from reference value ≤ 10% [24]. |

| Solution Stability | For HPLC/GC, evaluates standard and sample solutions in the prepared diluent over time in an autosampler or refrigerator. | For Assay: % Difference in Response Factor ≤ 2.0% [25].For Related Substances: No new peak ≥ Quantitation Limit; % difference for known impurities within set limits (e.g., ≤ 10%) [25]. |

Detailed Protocol: Solution Stability for Assay by HPLC

The following is a standardized protocol for establishing the stability of standard and sample solutions used in an assay method, crucial for ensuring the validity of analytical runs that may span several hours or days [25].

- Preparation: Prepare the standard and sample solutions as per the analytical method procedure.

- Aliquoting: Label six vials as V0 (initial), V1, V2, V3, V4, and V5. Transfer the solution into each vial.

- Time Points: Analyze the solutions at specified intervals, for example: V0 at 0 hours, V1 at 12 hours, V2 at 24 hours, V3 at 36 hours, V4 at 48 hours, and V5 at 60 hours.

- Analysis: At each time point, prepare a fresh standard solution and inject it in six replicates. Then, inject the corresponding stability solution (e.g., V1) in duplicate.

- Calculation:

- Calculate the Response Factor (RF) for each injection: RF = Area Response / Concentration.

- Calculate the average RF for the fresh standard (RFfresh) and for the stability solution (RFstability).

- Calculate the percentage difference:

% RF Difference = ( |RF_fresh - RF_stability| / ((RF_fresh + RF_stability)/2) ) * 100

- Acceptance Criterion: The solution is considered stable at a given time point if the % RF Difference is ≤ 2.0% [25].

The Comparative Method Validation Framework

In analytical chemistry, comparative method validation research involves systematically evaluating a new method (the "test method") against an established reference method to demonstrate its suitability for the intended purpose. The experimental design principles discussed are integral to this framework, ensuring the comparison is fair, unbiased, and scientifically sound [20] [17].

Experimental Workflow for Comparative Validation

A typical workflow for a comparative analytical method validation study, integrating the core elements of specimen number, selection, and stability, is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Comparative Method Validation Workflow

Application of Principles in Comparative Studies

- Specimen Number: The sample size for the comparison must be sufficient to provide adequate power for statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test, ANOVA) used to evaluate differences in accuracy, precision, or other key parameters between the two methods [21] [17]. Underpowered comparisons may lead to incorrect conclusions about method equivalence.

- Specimen Selection: Specimens used in the comparison should be representative of the future routine samples and should be assigned for analysis by the two methods in a randomized order to prevent systematic bias. A randomized block design might be used if specimens come from different sources or batches [21] [23].

- Specimen Stability: The integrity of the comparison relies on the analyte remaining unchanged during the analysis. If one method is slower or requires different sample preparation, stability must be demonstrated for the entire process duration for both methods. For instance, solution stability must cover the time a sample resides in the autosampler for each method [24] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials commonly used in experiments for analytical method validation, along with their critical functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Provides a highly characterized substance with known purity and identity, serving as the benchmark for quantifying the analyte in samples and for preparing calibrators [17] [24]. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | A compound added in a constant amount to all samples, calibrators, and quality controls. It corrects for variability in sample preparation, injection volume, and instrument response, improving accuracy and precision [24]. |

| Appropriate Biological Matrix | The blank biological fluid or tissue (e.g., plasma, serum, urine) used to prepare calibrators and quality control samples. It should mimic the composition of the actual study samples to ensure accurate assessment of specificity and potential matrix effects [24]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Spiked samples with known concentrations of the analyte at low, medium, and high levels within the calibration range. They are analyzed alongside unknown samples to monitor the method's accuracy, precision, and stability over time [24]. |

| Chromatographic Solvents & Mobile Phases | High-purity solvents and buffers used to prepare mobile phases and sample diluents. Their composition, pH, and purity are critical for achieving optimal separation, peak shape, and detector response in chromatographic methods [17] [25]. |

| Stabilizers | Reagents (e.g., enzyme inhibitors, antioxidants, chelating agents) added to biological samples or solutions to prevent analyte degradation, adsorption, or other changes during storage and processing [24]. |

| KU-0060648 | KU-0060648, CAS:881375-00-4, MF:C33H34N4O4S, MW:582.7 g/mol |

| L-685458 | L-685458, CAS:292632-98-5, MF:C39H52N4O6, MW:672.9 g/mol |

The rigorous application of sound experimental design principles pertaining to specimen number, selection, and stability forms the bedrock of credible comparative analytical method validation research. By systematically addressing sample size through power analysis, controlling bias via randomization and blocking, and ensuring data integrity through comprehensive stability testing, scientists can generate high-quality, reproducible data. This structured approach not only fulfills regulatory expectations but also builds a solid scientific foundation for making confident decisions about the validity and applicability of new analytical methods, ultimately contributing to the advancement of drug development and pharmaceutical quality control.