Essential Career Skills for Analytical Chemistry Researchers: A 2025 Guide to Mastery from Foundations to AI

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for analytical chemistry researchers and drug development professionals to master the essential skills demanded by the modern laboratory.

Essential Career Skills for Analytical Chemistry Researchers: A 2025 Guide to Mastery from Foundations to AI

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for analytical chemistry researchers and drug development professionals to master the essential skills demanded by the modern laboratory. Covering the full spectrum from core principles and advanced instrumentation to cutting-edge troubleshooting and rigorous data validation, this article synthesizes the latest trends, including the impact of automation, AI, and regulatory compliance. Readers will gain actionable strategies to enhance their technical expertise, improve data integrity, and advance their careers in the competitive, data-driven landscape of pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Building a Powerful Foundation: Core Competencies and Career Pathways for the Modern Analytical Chemist

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by advancements in microtechnology, artificial intelligence (AI), and a global commitment to sustainability [1]. The modern analytical chemist's role has expanded beyond traditional chemical analysis to encompass high-level data science, method development, and the implementation of green laboratory practices. This whitepaper examines the core responsibilities, technical skills, and innovative methodologies that define the analytical chemist in 2025, framing these competencies within the essential career skills for research scientists in drug development and related fields.

The paradigm is shifting from merely operating instruments to an integrated approach where data interpretation, troubleshooting, and strategic problem-solving are paramount. Furthermore, the push for sustainability is reshaping laboratory workflows, making knowledge of green analytical chemistry (GAC) principles a critical and sought-after skill [2] [1]. For the contemporary researcher, proficiency in this expanded toolkit is no longer optional but a necessity for pioneering new scientific discoveries and maintaining relevance in a competitive landscape.

Core Responsibilities and Required Skill Sets

The daily work of an analytical chemist is anchored in a core set of responsibilities, each demanding a specific combination of hard and soft skills. Mastery of this skillset is what distinguishes a competent researcher and enhances their employability in sectors like pharmaceuticals, environmental science, and materials science [3] [4].

Key Responsibilities:

- Method Development and Validation: Creating, optimizing, and validating robust analytical procedures to identify and quantify compounds according to regulatory standards (e.g., ICH guidelines) [3] [4].

- Quality Control and Assurance: Implementing and adhering to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) to ensure the quality, consistency, and reliability of analytical results [3] [4].

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Transforming raw instrumental data into meaningful, defensible scientific conclusions using statistical tools and software [3] [5] [6].

- Instrument Operation and Maintenance: Operating, calibrating, and maintaining sophisticated analytical instrumentation while following Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) [3].

- Troubleshooting and Problem-Solving: Diagnosing and resolving issues that arise with analytical methods, instrumentation, or data quality [3] [1].

Essential Skills for the Modern Analytical Chemist:

The table below summarizes the critical skills, as identified from current industry job demands and resume keywords [3] [4].

Table 1: Essential Skills for an Analytical Chemist in 2025

| Skill Category | Specific Skills | Industry Relevance & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation Proficiency | HPLC, GC, GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR, FTIR, UV/Vis Spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry [3] [4] | Fundamental for separation, identification, and quantification of compounds in pharmaceuticals (e.g., potency testing) and environmental monitoring (e.g., pollutant detection). |

| Data Analysis & Software | Statistical Analysis, Data Interpretation, MINITAB, JMP, Python, R, MATLAB, Empower, Chromeleon [3] [5] [4] | Critical for ensuring data accuracy, performing statistical quality control, and automating data processing. AI real-time data interpretation is a growing trend [1]. |

| Compliance & Safety | GLP, GMP, FDA Regulations, ISO 17025, Laboratory Safety, Chemical Safety, SOPs [3] [4] | Non-negotiable in regulated industries like drug development to ensure patient safety and data integrity for regulatory submissions. |

| Technical & Lab Skills | Method Development, Analytical Method Validation, Sample Preparation, Titration, Wet Chemistry, Quality Control (QC) [3] [4] | The practical, hands-on skills required for daily laboratory work, from preparing samples for analysis to ensuring the validity of the methods used. |

Key Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The analytical chemist's expertise is demonstrated through the application of specific methodologies. The following section details core protocols and highlights the growing importance of qualitative analysis in conjunction with quantitative measurement.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Method Development for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Objective: To develop and validate a stability-indicating HPLC method for the assay and related substance analysis of a new active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [3] [4].

Experimental Protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Stock Solution: Accurately weigh and dissolve the API in a suitable solvent to yield a known concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL).

- System Suitability Solution: Prepare a mixture containing the API and its known potential degradants at specified levels.

- Test Solution: Prepare the drug product formulation as per the method, typically involving extraction into a diluent.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18, 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm or similar.

- Mobile Phase: Typically a gradient mixture of a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) and an aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate or formate, pH-adjusted).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection: UV-Vis or Photodiode Array (PDA) Detector, set at an appropriate wavelength for the API.

- Injection Volume: 10 µL.

- Column Temperature: 30°C.

-

- Specificity: Demonstrate that the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present (e.g., impurities, degradants, excipients). This is typically done by subjecting the API to stress conditions (forced degradation).

- Linearity and Range: Prepare and analyze API solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels, from below to above the expected range. The correlation coefficient (r) should be >0.999.

- Accuracy: Conduct a recovery study by spiking the drug product with known amounts of the API at multiple levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150%). Percent recovery should be within 98-102%.

- Precision:

- Repeatability: Inject six replicates of a standard solution and calculate the %RSD of the peak area (typically ≤1.0%).

- Intermediate Precision: Have a second analyst repeat the study on a different day using a different instrument to demonstrate ruggedness.

- Detection Limit (LOD) and Quantitation Limit (LOQ): Determine via signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., 3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ) or based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [5].

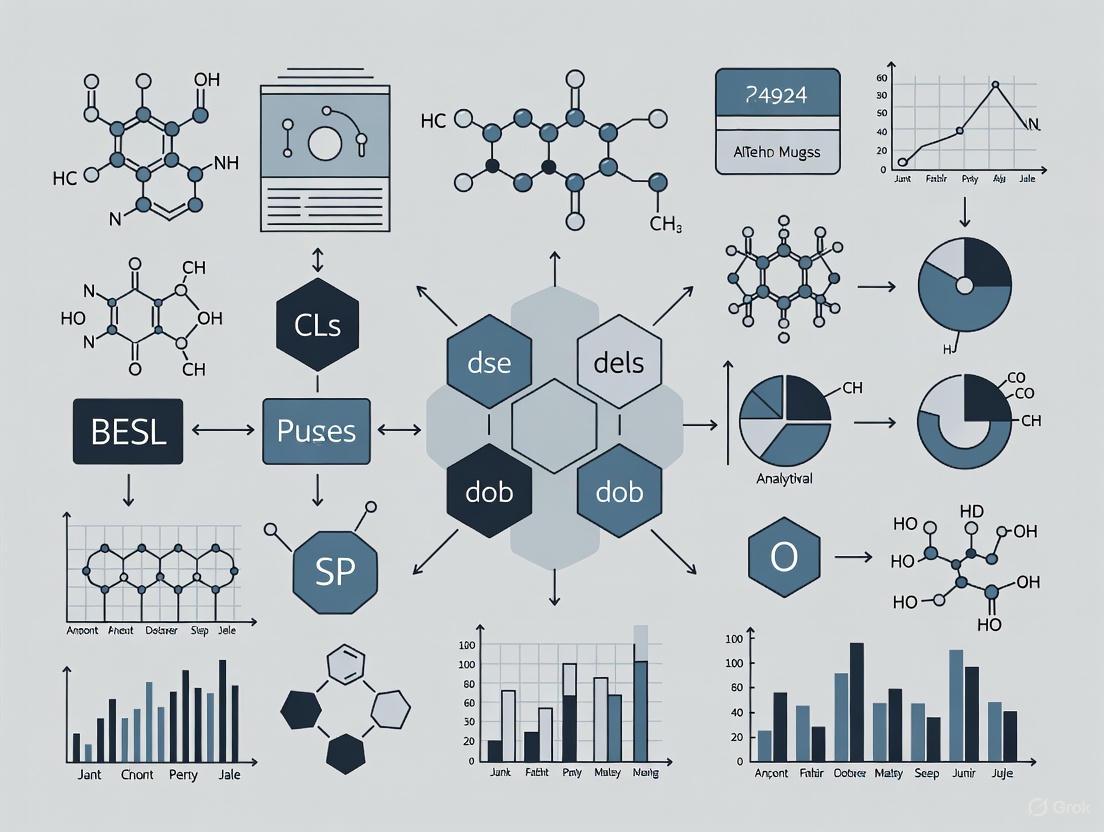

Diagram 1: HPLC Method Development Workflow

The Role of Qualitative Analysis in Identification

While quantitative analysis determines "how much" is present, qualitative analysis is fundamental to identifying "what" is present [7] [8] [9]. In an analytical context, this involves:

- Structural Elucidation: Using techniques like Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) to determine the molecular structure of an unknown compound or impurity [3] [6]. For example, NMR reveals the carbon-hydrogen framework, while MS provides information on molecular weight and fragmentation patterns.

- Compound Confirmation: Using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy to identify functional groups in a molecule, confirming its identity by matching its spectrum to a reference standard [3] [4].

- Hypothesis Generation: In research, qualitative observations often precede quantitative measurement. Discovering an unknown peak in a chromatogram (a qualitative finding) leads to hypotheses about its identity, which are then tested and quantified [7] [10].

This interplay is a critical research skill. A chemist must be adept at interpreting spectral and chromatographic data to make informed decisions about the identity and purity of substances before quantification.

Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Statistical Rigor

The ability to evaluate, organize, and draw meaningful conclusions from collected data is a cornerstone of the analytical chemist's role [3] [5] [6]. Data analysis in analytical chemistry serves to identify substances, quantify analytes, ensure quality, and document changes [6].

Statistical Tools for Data Interpretation

Robust data interpretation relies on statistical tools to ensure accuracy and reliability [5] [6].

Table 2: Key Statistical Tools for Analytical Data Interpretation

| Statistical Tool | Application in Analytical Chemistry | Example & Acceptability Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Statistics | Summarizes the central tendency and variability of a dataset. | Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), %RSD (Relative Standard Deviation). For a system precision test in HPLC, the %RSD of peak areas for six injections should be ≤1.0% [5]. |

| Hypothesis Testing (t-tests, ANOVA) | Determines if there is a statistically significant difference between two or more sets of data. | Student's t-test: Comparing the mean results of an API assay from two different laboratories. A p-value > 0.05 suggests no significant difference. ANOVA: Comparing the performance of multiple analysts or instruments for the same method [5]. |

| Regression Analysis | Models the relationship between the analytical response (signal) and the concentration of the analyte (dose). | Linear Regression for calibration curves. The correlation coefficient (r) should typically be >0.999. Used to calculate the concentration of unknown samples [5] [6]. |

| Quality Control Charts | Monitors the performance of an analytical method over time to ensure it remains in a state of control. | Plotting the result of a control standard on a Shewhart chart with upper and lower control limits (e.g., mean ± 3SD). Detects trends or shifts in method performance [5] [6]. |

Error and Uncertainty Analysis

A critical part of the analytical process is understanding and quantifying error [5]. This involves:

- Accuracy and Precision: Accuracy (closeness to the true value) is often assessed through recovery studies, while precision (reproducibility of measurements) is measured by standard deviation or %RSD [5].

- Propagation of Uncertainty: Estimating the overall uncertainty in a final result that is derived from several measurements, each with its own uncertainty [5].

Diagram 2: Data Analysis and Interpretation Workflow

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of analytical chemistry is being reshaped by several key innovations that are becoming essential knowledge for researchers.

- Miniaturization and Lab-on-a-Chip (LOC) Technology: LOC devices integrate one or more laboratory functions onto a single chip, drastically reducing sample and reagent volumes (to microliters or nanoliters), accelerating analysis times, and enabling portability for point-of-care diagnostics and on-site environmental monitoring [1].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: AI real-time data interpretation is revolutionizing workflows. Machine learning algorithms can automatically process complex chromatographic or spectral data, perform peak integration and deconvolution, and even predict optimal chromatographic conditions during method development. AI also enables predictive maintenance by monitoring instrument data to prevent downtime [1].

- Single-Molecule Detection: Moving beyond traditional "ensemble" measurements, techniques like single-molecule fluorescence microscopy and nanopore sensing are pushing detection limits to the ultimate frontier. This allows for the observation of individual molecules, uncovering heterogeneity and enabling the early detection of disease biomarkers at ultra-low concentrations [1].

- Sustainable Analytical Chemistry: The push for green analytical chemistry (GAC) is a major trend, focusing on reducing the environmental impact of analytical processes [2] [1]. This involves:

- Solvent Reduction and Replacement: Switching to greener solvents (e.g., water, CO2) and employing miniaturized methods to cut consumption.

- Waste Prevention: Implementing solvent-free methods (e.g., Solid-Phase Microextraction) and improving waste segregation for recycling.

- Energy Efficiency: Optimizing methods for shorter run times and utilizing less energy-intensive techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents used in modern analytical laboratories, along with their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item/Reagent | Function in Analytical Chemistry |

|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns (HPLC, GC) | The heart of the separation process. Contain a stationary phase that interacts differently with components in a mixture, causing them to elute at different times. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents & Buffers | The liquid that carries the sample through the chromatography system. Its composition is critical for achieving separation and must be of high purity (HPLC-grade) to avoid interference. |

| Certified Reference Standards | High-purity materials with a certified concentration or property. Essential for calibrating instruments, qualifying methods, and ensuring the accuracy and traceability of results. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemicals used to chemically modify an analyte to make it more detectable (e.g., by adding a fluorescent tag) or volatile enough for Gas Chromatography (GC) analysis. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Used for sample preparation to clean up complex samples and pre-concentrate analytes, which improves sensitivity and reduces matrix interference. |

| Tetracos-17-en-1-ol | Tetracos-17-en-1-ol, CAS:62803-17-2, MF:C24H48O, MW:352.6 g/mol |

| 9-cis-Lycopene | 9-cis-Lycopene, CAS:64727-64-6, MF:C40H56, MW:536.9 g/mol |

For analytical chemistry researchers and drug development professionals, the evolving landscapes of the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and environmental monitoring sectors present distinct career pathways and skill demands. These high-growth, technically driven fields increasingly rely on sophisticated analytical techniques to ensure drug efficacy, patient safety, and manufacturing quality. This whitepaper provides a detailed analysis of employment trends, market drivers, and core technical competencies across these sectors, with a specific focus on the practical applications of analytical chemistry. It aims to serve as a strategic career guide for scientists navigating these dynamic industries, highlighting where analytical expertise creates the most significant impact.

Employment and Market Analysis

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Employment

The U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing sector is a substantial employer, characterized by strong regional clusters and diverse sub-specialties. Recent data provides a detailed view of employment distribution and industry composition.

Table 1: Top U.S. States for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Employment (2025) [11]

| State | Number of Employees | Percentage of U.S. Total |

|---|---|---|

| New Jersey | 49,109 | 12.9% |

| California | 47,996 | 12.6% |

| Pennsylvania | 33,317 | 8.7% |

| New York | 28,006 | 7.3% |

| North Carolina | 22,931 | 6.0% |

| Massachusetts | 21,525 | 5.6% |

| Indiana | 16,932 | 4.4% |

| Illinois | 16,416 | 4.3% |

| Michigan | 15,728 | 4.1% |

| Maryland | 14,202 | 3.7% |

The industry is dominated by private firms (50.9%) and is segmented into four primary subindustries [11]:

- Pharmaceutical Preparations (SIC 2834): 50.9% (1,289 companies) producing finished drug products.

- Medicals and Botanicals (SIC 2833): 20.3% (515 companies) producing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and bulk chemicals.

- Biological Products (SIC 2836): 16.5% (417 companies) producing vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and cell therapies.

- Diagnostic Substances (SIC 2835): 12.4% (313 companies) producing reagents and test kits.

In contrast, the specific niche of generic pharmaceutical manufacturing employed 54,597 people in 2025 and has experienced a -2.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in employment from 2020-2025 [12].

Biotechnology Job Market

The U.S. biotechnology job market represents a critical and expansive component of the life sciences sector, demonstrating robust long-term growth despite recent market corrections [13].

Table 2: U.S. Biotech Job Market Trends (2023-2025)

| Metric | Figure / Trend |

|---|---|

| Total Direct U.S. Employment (2023) | Over 2.3 million workers |

| Economic Output (2023) | $3.2 trillion |

| Employment Growth (2019-2023) | +15% |

| 20-Year Growth in Life Sciences Research Employment | +79% (vs. +8% for overall U.S. jobs) |

| Current State (Late 2025) | Mixed resilience and fragility; record high of ~2.1 million jobs in March 2025, but sluggish growth and slight Q2 pullback. |

| Unemployment Rate (April 2025) | ~3.1% (for life and physical science occupations) |

The market is highly concentrated in major hubs, with the San Francisco Bay Area alone accounting for approximately 153,000 biotech jobs by mid-2023 [13]. Top clusters also include Boston-Cambridge, San Diego, New York/New Jersey, and the Washington D.C.-Baltimore region. Emerging hubs in North Carolina and Texas are growing rapidly, often driven by biomanufacturing investments and lower costs [13].

Environmental Monitoring Market

Environmental monitoring is a critical, rapidly growing segment within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, essential for ensuring product quality and regulatory compliance [14].

Table 3: Environmental Monitoring Market Overview

| Segment | Details |

|---|---|

| Global Pharmaceutical & Biotech EM Market (2023) | $24 billion [15] |

| Projected Market Value (2030) | $38.1 billion [15] |

| Projected CAGR (2024-2030) | 6.3% [15] |

| Broader Environmental Monitoring Market (2024) | $14.7 billion [16] |

| Projected Market (2029) | $18.6 billion [16] |

| Projected CAGR | 4.9% [16] |

| Key Growth Drivers | Stricter regulatory requirements, expansion of biopharma & sterile product manufacturing, technological advancements (real-time monitoring, AI, IoT) [14] [15]. |

This market encompasses monitoring of air quality, microbial contamination, particulate matter, and temperature controls within manufacturing and research facilities [14]. Leading players include Thermo Fisher Scientific, Merck & Co., Inc., Sartorius AG, and Agilent Technologies [15].

Core Technical Skills and Experimental Protocols

The convergence of these sectors demands a strong foundation in analytical chemistry, which is defined as "the science of obtaining, processing, and communicating information about the composition and structure of matter" [17]. The modern analytical chemist must be proficient in instrumentation, statistics, data analysis, and problem-solving across various industrial contexts [17].

Key Experimental Workflow: Pharmaceutical Environmental Monitoring

A core application of analytical chemistry in the regulated life sciences industry is environmental monitoring (EM) to ensure aseptic manufacturing conditions. The following workflow details a standard non-viable particulate monitoring protocol for a cleanroom.

Diagram Title: Pharmaceutical Cleanroom Air Monitoring Workflow

Detailed Methodology

- Objective: To monitor and control non-viable particulate levels in a Grade A (ISO 5) critical zone during aseptic filling operations, ensuring compliance with EU GMP Annex 1 and FDA guidance.

- Sampling Plan & Site Selection: Based on a formal risk assessment. Sampling locations are mapped in the cleanroom with sites selected to represent the critical zone (e.g., fill needles, open vials), background environment, and potential contamination risk areas. Sampling frequency is defined per batch and routine schedule [14].

- Instrumentation Setup:

- Laser Airborne Particle Counter: Calibrated and certified to ISO 21501-4.

- Calibration: Using a traceable standard (e.g., latex spheres or SEM photomicrograph) for particle size and count accuracy.

- Sampling Tube: Use a short, conductive tube to minimize particle loss.

- Flow Rate: Set to 1.0 cubic foot per minute (28.3 liters per minute) with isokinetic sampling head.

- Execution & Air Sampling:

- Sterilize the sampling head with a sterile, non-shedding wipe and 70% IPA before entering the cleanroom.

- Place the sampler in the predefined location without disrupting the unidirectional airflow.

- Initiate sampling for the prescribed duration (e.g., 1 minute per location for a total volume of 1 m³).

- Record sample volume, location, time, and operator ID.

- Data Analysis & Acceptance Criteria:

- The instrument software automatically calculates particle concentrations for specified sizes (e.g., ≥0.5µm and ≥5.0µm).

- Grade A/ISO 5 Action Limits: ≥0.5µm: 3,520 particles/m³ | ≥5.0µm: 20 particles/m³.

- Data is compared against these limits. Counts exceeding the limits trigger an alert and investigation.

- Data Integrity & Documentation: All data is recorded in a controlled worksheet or electronic system. The record includes instrument ID, calibration due date, sample locations, raw data, results versus limits, and a statement of compliance signed by the QA reviewer [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Environmental Monitoring & Analytical Testing

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Culture Media (e.g., Tryptic Soy Agar, Sabouraud Dextrose Agar) | Used for viable particulate monitoring to capture and grow environmental bacteria and fungi [14]. |

| ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kits | Contain luciferase enzyme and luciferin. Used for rapid hygiene monitoring by detecting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from microbial and organic residues. |

| Particle Count Standards (e.g., NIST-traceable latex spheres) | Essential for calibration and qualification of laser particle counters to ensure accurate size and count reporting [17]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | High-purity chemicals with certified concentrations for instrument calibration (e.g., HPLC, GC) and analytical method validation [17]. |

| Sterile Neutralizing Buffers | Used to inactivate residual disinfectants (e.g., on surface contact plates) to prevent false negative results in microbial testing [14]. |

| (Nitroperoxy)ethane | (Nitroperoxy)ethane|Research Compound |

| Verrucarin K | Verrucarin K|CAS 63739-93-5|Research Compound |

Industry Trends and Career Implications

Strategic Shaping the Pharmaceutical

The pharmaceutical industry faces significant business model pressures, prompting strategic shifts with direct implications for analytical scientists. PwC outlines four strategic bets companies are making [18]:

- Reinvent R&D Productivity: Leveraging AI and digital agents to accelerate drug discovery and development, reducing costs and timelines.

- Competitive Advantage through Focus: Exiting markets and functions without a competitive edge, focusing investment on core differentiators.

- Win with the Patient: Investing in direct-to-patient engagement platforms and personalized content to improve the patient experience.

- Deliver Health Solutions: Expanding beyond therapeutics into connected health solutions, diagnostics, and monitoring services.

For researchers, this underscores the growing value of data science, AI, and computational skills alongside deep analytical expertise. The ability to work with large datasets, develop predictive models, and operate sophisticated, automated instrumentation is becoming paramount [17] [18].

The Evolving Talent and Skills

The high demand for skilled talent persists, but the definition of required skills is evolving [13] [19]:

- Cross-Disciplinary Demand: There is a strong need for professionals who blend wet-lab skills with expertise in data science, bioinformatics, and regulatory affairs [13].

- The EHS Talent Shortage: A notable 57% of companies struggle to hire Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) professionals. This is driven by retiring Baby Boomers, new tech skill demands (AI, IoT, data analytics), and low career awareness among younger workers [19]. This gap represents a significant opportunity for analytical chemists with an interest in quality control and regulatory science.

- Focus on "Soft Skills": As the industry moves towards more collaborative and patient-centric models, skills like communication, problem-solving, and cross-functional teamwork are increasingly critical [17] [18].

The pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and environmental monitoring sectors offer robust and dynamic career landscapes for analytical chemists and drug development professionals. While each sector has unique characteristics, they are unified by a dependence on precise, reliable data generated through sophisticated analytical techniques. The successful scientist of the future will be one who couples a strong foundation in core analytical principles with an adaptive mindset, embracing new technologies like AI and data analytics, and understanding the broader regulatory and quality frameworks that govern these industries. By aligning their skill development with these key employment and market trends, researchers can strategically position themselves for long-term impact and career growth in these vital fields.

In the dynamic field of analytical chemistry, proficiency in chromatography, spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry is not merely advantageous—it is fundamental to success. For researchers and drug development professionals, these techniques form the essential toolkit for elucidating molecular structures, characterizing complex mixtures, and ensuring the quality and safety of pharmaceutical products [20]. The ability to accurately interpret the vast data streams generated by modern instruments is a critical, often angst-producing art that separates competent scientists from true experts [21]. As mass spectrometry (MS) in particular has evolved to couple with "every delivery system imaginable," the challenge has shifted from simply generating data to converting it into knowable information and applying it to solve complex problems [21]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these essential hard skills, framed within the context of career development for analytical chemistry researchers, to bridge the gap between academic knowledge and industrial application.

Mass Spectrometry: Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Mass spectrometry stands as a cornerstone technology in modern analytical science, providing unparalleled sensitivity and precision for identifying and quantifying a vast array of compounds [22]. Understanding its fundamental principles and evolving instrumentation landscape is crucial for effective application in research and development settings.

Core Mass Spectrometry Techniques

The mass spectrometer's data output results from our evolving ability to detect ions in a vacuum, beginning with analog electronics and oscilloscope displays [21]. Modern MS techniques can be categorized into several fundamental approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Quadrupole MS employs a quadrupole filter consisting of four parallel rods that generate an oscillating electric field to separate ions based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio [22]. This versatile and robust technique is valued particularly for quantitative analysis, targeted proteomics, lipidomics, metabolomics, forensics, and environmental monitoring [22]. Its ability to perform multiple stages of mass analysis in tandem quadrupole systems significantly enhances its application in complex mixture analysis and structural elucidation [22].

Time-of-Flight (TOF) MS measures the time ions take to travel through a flight tube to reach the detector, with lighter ions arriving faster than heavier ones [22]. This technique is renowned for its high-resolution and rapid analysis capabilities, making it indispensable in applications requiring accurate mass determination such as peptide mass fingerprinting in proteomics, polymer analysis, clinical analysis, and identification of complex mixtures [22]. Recent advancements like multi-reflecting TOF (MR-TOF) technology utilize multiple reflection stages within the flight tube to extend the ion pathlength, thereby improving mass resolution and accuracy without increasing the instrument's physical size [22].

Ion Trap MS utilizes a trapping field to confine ions in a three-dimensional space, allowing for their manipulation and analysis [22]. Various types include the quadrupole ion trap, ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) trap, and linear ion trap, which employ electric or magnetic fields to trap ions with specific m/z ratios [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for its capability to perform multi-stage mass spectrometry (MSâ¿), providing detailed structural information about analytes through multiple fragmentation stages [22]. This makes ion traps indispensable for complex sample analysis, including peptide sequencing in proteomics and structural elucidation of complex organic compounds [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Mass Spectrometry Techniques

| Technique | Key Separation Mechanism | Key Applications | Key Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole MS | Oscillating electric field filters ions by m/z | Quantitative analysis, targeted -omics, environmental monitoring | Versatile, robust, good for targeted analysis |

| Time-of-Flight (TOF) MS | Measures ion flight time through a field-free region | Proteomics, polymer analysis, complex mixtures | High resolution, rapid analysis, accurate mass measurement |

| Ion Trap MS | Electric/magnetic fields trap and eject ions by m/z | Peptide sequencing, structural elucidation, trace contaminant detection | Excellent for MSâ¿ experiments, detailed structural information |

Advanced and Hybrid Mass Spectrometry Systems

Technological evolution has produced increasingly sophisticated mass analyzers and hybrid systems that combine complementary strengths to address complex analytical challenges:

Orbitrap (Orbital Ion Trap) MS has emerged as a leading technique for high-resolution mass analysis, utilizing an electrostatic field to trap ions in an orbiting motion around a central electrode [22]. The frequency of this motion relates directly to the ion's m/z ratio, enabling highly accurate mass measurements [22]. Modern Orbitrap instruments can achieve exceptionally high mass resolution (>100,000) at m/z 35,000, making them particularly valuable for detailed molecular characterization and analysis of extremely complex biological samples [22].

Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) MS is renowned for its exceptional mass resolution and accuracy, trapping ions in a magnetic field and measuring their cyclotron motion using an oscillating electric field [22]. The Fourier transform of the resulting signal provides high-resolution mass spectra with unparalleled accuracy [22]. Recent innovations have enhanced its capability for ultrahigh resolution and complex mixture analysis through improved magnetic field strengths and more sensitive detectors [22].

Hybrid MS systems such as quadrupole-Orbitrap and quadrupole-TOF configurations combine the strengths of different mass analyzers to achieve superior sensitivity and mass accuracy [22]. The quadrupole-Orbitrap hybrid integrates a quadrupole mass filter for ion selection with an Orbitrap analyzer for high-resolution analysis, significantly enhancing sensitivity for detecting low-abundance compounds [22]. Similarly, quadrupole-TOF systems pair the mass filtering capability of a quadrupole with the high-resolution and accurate mass measurement of a TOF analyzer [22].

Table 2: Advanced and Hybrid Mass Spectrometry Systems

| System Type | Key Technology Components | Key Analytical Strengths | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbitrap MS | Electrostatic orbital trapping | Ultrahigh resolution (>100,000), high mass accuracy | Proteomics, metabolomics, structural biology |

| FT-ICR MS | Magnetic trapping with Fourier transform detection | Exceptional resolution and mass accuracy | Complex mixture analysis, petroleumomics, natural products |

| Quadrupole-Orbitrap Hybrid | Quadrupole mass filter + Orbitrap analyzer | High sensitivity for low-abundance compounds, high resolution | Biomarker discovery, trace contaminant analysis |

| Quadrupole-TOF Hybrid | Quadrupole mass filter + TOF analyzer | Good sensitivity with high resolution and accurate mass | Metabolite identification, forensic analysis |

The development of soft ionization techniques has dramatically expanded the application range of mass spectrometry, particularly for biological macromolecules:

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) has seen significant enhancements, particularly with the development of nano-electrospray ionization (nano-ESI), which uses extremely fine capillary needles to produce highly charged droplets from very small sample volumes [22]. This technique improves sensitivity and resolution by minimizing sample requirements and reducing background noise associated with larger volumes [22]. Nano-ESI is particularly beneficial for analyzing low-abundance biomolecules and complex mixtures where high sensitivity enables detection of trace analytes that might otherwise remain undetected [22].

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) has undergone innovations aimed at improving spatial resolution and quantification, including the development of new matrix materials with improved ultraviolet absorption properties that enhance ionization efficiency while reducing matrix-related noise [22]. Technological improvements in MALDI instrumentation, such as higher-resolution mass analyzers and advanced imaging techniques, have significantly enhanced spatial resolution, enabling more detailed analysis of biological tissues and complex samples [22]. MALDI imaging specifically allows researchers to visualize the distribution of metabolites, proteins, and lipids within tissue sections, providing critical insights into spatially resolved molecular information [22].

Ambient Ionization Techniques including desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) and direct analysis in real time (DART) represent a significant leap forward by enabling sample analysis at ambient temperatures and pressures without extensive preparation [22]. DESI sprays charged solvent droplets onto a sample surface to desorb and ionize analytes for immediate analysis, while DART utilizes a stream of excited atoms or molecules to ionize samples directly from their native state [22]. These techniques have expanded MS applications to include on-site analysis in forensic investigations, environmental monitoring, and quality control in manufacturing processes [22].

Chromatography and Separation Science

Chromatography techniques remain fundamental to analytical chemistry, providing the critical separation power needed to resolve complex mixtures before detection and characterization.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has become an indispensable analytical technique known for its high accuracy and time efficiency in metabolite analysis [20]. Over time, it has evolved to play a crucial role in biological metabolite research, with LC-MS-based techniques now regarded as essential tools in metabolomics studies [20]. Due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and rapid data acquisition, LC-MS is well suited for detecting a broad spectrum of nonvolatile hydrophobic and hydrophilic metabolites [20]. The integration of novel ultra-high-pressure techniques with highly efficient columns has further enhanced LC-MS, enabling the study of complex and less abundant bio-transformed metabolites [20].

The historical development of LC-MS marks groundbreaking innovations in analytical methodologies, with its integration first conceptualized in the mid-20th century as the analytical chemistry community sought to develop versatile tools for complex sample analysis [20]. The first commercial LC-MS system emerged in the 1970s, beginning a new era that allowed scientists to combine the advantages of both LC and MS for real-time, accurate, high-resolution analysis [20]. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, technology evolved significantly with the introduction of new ionization techniques like electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) that dramatically enhanced sensitivity and expanded the range of detectable analytes [20].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) provides exceptional separation efficiency for volatile and semi-volatile compounds, making it particularly valuable in metabolomics, environmental analysis, and forensic applications [23]. Modern GC-MS systems include single quadrupole configurations for routine analysis, triple quadrupole systems for enhanced sensitivity and specificity in targeted analyses, and GC-Time-of-Flight systems capable of providing accurate mass measurements for untargeted studies and complex mixture analysis [23]. The core strength of GC-MS lies in its ability to separate complex mixtures of small molecules with high resolution, particularly when coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometers like the Leco GC-HRT+ GC/Time-of-Flight MS, which delivers exceptional mass accuracy and resolution for compound identification [23].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Proper experimental design is paramount to generating reliable, reproducible data in analytical chemistry. This section outlines fundamental methodologies and protocols that form the foundation of rigorous analytical research.

Mass Spectrometry Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for mass spectrometry-based analysis, from sample preparation to data interpretation:

Targeted vs. Untargeted Analysis Approaches

Analytical methods can be broadly categorized into targeted and untargeted approaches, each with distinct objectives and methodologies:

Targeted Analysis focuses on identifying and quantifying a pre-defined set of compounds with high sensitivity and specificity [24]. In metabolomics, targeted panels are developed to provide high-confidence compound identification through direct comparison to known chemical standards, enabling precise quantification of compounds within specific metabolic pathways [24]. Targeted assays in proteomics, such as parallel-reaction monitoring (PRM), enable the detection and quantification of a predetermined subset of proteins with high sensitivity and reproducibility across many samples [24].

Untargeted Analysis aims to comprehensively detect as many features as possible in a sample without prior knowledge of its composition [24]. This hypothesis-generating approach uses library matching for compound identification and is particularly valuable for biomarker discovery and detecting novel metabolites or lipids [24]. In proteomics, data-independent acquisition (DIA) has emerged as an alternative comprehensive identification and quantification method, fragmenting all ions within specific mass ranges to generate more signals for each peptide, resulting in more reliable relative quantification than conventional label-free approaches [24].

Stable Isotope Tracing and Metabolic Flux Analysis

Metabolic tracing experiments provide critical understanding of metabolic flux within biological systems by introducing heavy stable isotopes (such as ¹³C) and using mass spectrometry to detect alterations in isotope patterns, determining the fraction of each metabolite pool containing the heavy atoms [24]. These analyses can be either targeted or untargeted and require unlabeled control samples to correct for naturally occurring isotopes already present in the system [24]. Proper experimental design and sample handling are essential for generating meaningful flux data, and core facilities typically provide guidance throughout this process [24].

Absolute Quantitation Methodologies

While many metabolomics and proteomics approaches provide relative quantitation, absolute quantitation requires additional method development and specific controls [24]. This approach involves preparing and analyzing target metabolites or peptides at known concentrations to generate a dilution curve, with the response used to quantitate biological samples through regression analysis [24]. Absolute quantitation requires isotopically labeled internal standards added to both experimental and quantitation samples to correct for matrix effects and instrument variability [24]. These methods require metabolite- and matrix-specific development to ensure accurate quantitation but provide the highest level of quantitative precision once established [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful analytical chemistry research requires careful selection and application of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for experiments in chromatography and mass spectrometry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Correct for matrix effects and instrument variability | Absolute quantitation in targeted MS |

| EquiSPLASH Standard Mixture | Validate accuracy of lipid identification and quantification | Lipidomics by LC-MS |

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Multiplexed relative protein quantification | Proteomics (up to 16 samples simultaneously) |

| Trypsin | Proteolytic digestion of proteins to peptides | Bottom-up proteomics |

| Heavy Isotope-labeled Peptides | Internal standards for targeted protein quantification | Parallel-reaction monitoring (PRM) assays |

| Chemical Isotope Labeling (CIL) Reagents | Enhance sensitivity and quantification in metabolomics | LC-tandem mass spectrometry |

| Perfluorinated Compounds | Calibrate m/z scale in electron ionization MS | Instrument calibration |

| Chromatography Columns | Separate complex mixtures prior to detection | LC-MS and GC-MS analyses |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents | Improve retention of polar metabolites | Reverse-phase LC-MS of polar compounds |

Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Bioinformatics

The ability to effectively process, analyze, and interpret complex datasets is increasingly critical in modern analytical chemistry, where advanced instrumentation generates vast amounts of data requiring sophisticated bioinformatics approaches.

Critical Data Analysis Skills

Survey results from the analytical chemistry community identify several data analysis topics as among the most important skills for new hires, with method qualification, data interpretation, standard additions and internal standards, and system calibration and system suitability ranked highest by both industrial managers and scientists [25]. Nearly all data analysis categories were marked as "useful" or "very useful" by respondents, underscoring the critical importance of these skills in industrial settings [25].

For mass spectrometry data specifically, interpretation begins with identifying an ion that represents the intact molecule—in atmospheric pressure ionization modes like ESI or APCI, this involves looking for ions representing the protonated (M + H) or deprotonated (M - H) molecule while considering potential adduct ions forming with solvent and other molecules [21]. Applying the nitrogen rule helps determine whether analytes contain an odd or even number of nitrogen atoms, while using the intensity of isotope peaks provides additional information about elemental composition [21]. For larger molecules (above 500 Da), accounting for mass defect becomes essential, as the monoisotopic mass peak will be offset from where the nominal mass peak should be observed by an amount equal to the mass defect of the ion [21].

Bioinformatics and Computational Tools

Modern core facilities employ specialized software and informatics pipelines for metabolomics and proteomics investigations, with computational services including data processing, imputation, statistical analyses, data visualization, and various specialized bioinformatics analyses [24]. Common software platforms include Waters Progenesis QI and Thermo Compound Discoverer for untargeted processing of LC/MS data, Agilent Profiler and MassProfiler Professional for untargeted analysis of GC/MS data, and specialized tools like SCiLS Lab for MALDI imaging data and PolyTools for polymer data [23]. The ability to work with these computational tools and interpret their outputs is increasingly essential for analytical chemists.

Career Development and Skill Application

Technical proficiency must be coupled with strategic career development to maximize impact in analytical chemistry research positions. Understanding industry expectations and skill requirements is essential for success.

Essential Skills for Industrial Positions

Recent surveys of the analytical chemistry community reveal clear priorities for new hires, with liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry identified as the most important techniques for new hires to understand, followed closely by gas chromatography [25]. Perhaps surprisingly, fundamental skills including accurate weighing techniques and solution preparation and volumetric techniques were identified as the most crucial laboratory skills, followed by buffer preparation, solution miscibility, effective sampling, and sample diluent effects [25].

The largest differentiation between "manager" and "scientist" respondents appeared in the importance of transferable skills [25]. While critical thinking and problem solving, time management, project management, and teamwork were ranked as highly important by both groups, managers placed significantly higher importance on online communication and teleconferencing, oral communication, and written communication [25]. This suggests that those more involved in hiring processes value strong communication skills in new industry hires, highlighting the need to develop both technical and soft skills for career advancement [25].

Bridging the Academia-Industry Gap

Many new scientists discover a "wide chasm" between the information provided during education and what is needed to perform effectively in industrial positions [26]. While academic environments teach students to research, explore science, and learn independently, industry typically expects employees to know what is required to perform their jobs, with less tolerance for learning through mistakes [26]. Successful transition requires acknowledging these differences and seeking opportunities for continued learning outside formal education, including short courses, professional society resources, and mentorship [26].

Professional societies including the Coblentz Society, Society for Applied Spectroscopy, and ACS Subdivision on Chromatography and Separations Chemistry offer valuable resources including curated research and educational webcasts, links to practical information, downloadable resources, and networking opportunities [26]. In-person short courses at professional meetings like EAS, Pittcon, and SciX provide practical continuing education on specific topics, while virtual learning opportunities offer flexible alternatives [26]. These resources are particularly valuable for techniques like infrared spectroscopy, which industrial surveys rank in the top five expected skills but which academia often covers inadequately [26].

Mastering chromatography, spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry requires both deep technical knowledge and practical application skills that extend beyond instrumental operation to encompass experimental design, data interpretation, and problem-solving capabilities. As these technologies continue evolving with innovations in ionization sources, mass analyzers, and hybrid systems, the fundamental principles of accurate measurement, rigorous validation, and critical interpretation remain constant. For researchers and drug development professionals, developing these essential hard skills creates a foundation for scientific innovation, enabling the precise characterization of complex biological systems, ensuring product quality and safety, and ultimately advancing human health through improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. By combining technical expertise with complementary soft skills and maintaining commitment to continuous learning, analytical chemists can effectively bridge the academia-industry gap and position themselves for successful, impactful careers at the forefront of scientific discovery.

In the highly technical field of analytical chemistry and drug development, success is often attributed to proficiency with instrumentation and methodological expertise. However, the increasing complexity of research, characterized by interdisciplinary collaboration and large datasets, demands a parallel mastery of critical soft skills. This whitepaper delineates the essential roles of problem-solving, communication, and systems thinking, framing them within the career development framework for analytical chemistry researchers. These competencies are not ancillary; they are the foundational elements that enable effective application of technical knowledge, driving innovation and ensuring the integrity and impact of scientific outcomes.

Problem-Solving: A Structured Methodology for Analytical Challenges

Effective problem-solving in analytical chemistry transcends simple troubleshooting; it is a systematic process for navigating from an ambiguous symptom to a validated, actionable solution.

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Root Cause Analysis for HPLC Peak Tailing

- Problem Definition: A routine Quality Control (QC) analysis using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) shows a significant increase in peak tailing for a key active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), exceeding the system suitability criteria (Asymmetry Factor > 2.0).

- Hypothesis Generation: Potential causes are brainstormed and prioritized.

- Primary Hypothesis: Column degradation or contamination.

- Secondary Hypothesis: Inappropriate mobile phase pH or composition.

- Tertiary Hypothesis: Sample-related issues (e.g., solvent mismatch, contamination).

- Experimental Design & Data Acquisition: A sequential, controlled investigation is performed.

- Replace HPLC Column: Install a new, certified column from the same lot and re-inject the system suitability standard.

- Prepare Fresh Mobile Phase: If step 1 fails, prepare a new batch of mobile phase from fresh, high-purity reagents and repeat the injection.

- Sample Diluent Investigation: If step 2 fails, re-prepare the sample using a diluent that more closely matches the mobile phase composition.

- Data Analysis & Interpretation: Quantitative data from each experiment is collected and compared against acceptance criteria.

Table 1: Quantitative Data from HPLC Peak Tailing Investigation

| Experiment Step | Asymmetry Factor (Tailing) | Resolution (from closest peak) | Observation & Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Problem | 2.4 | 4.5 | Fails system suitability. Problem confirmed. | |

| New Column Installed | 1.1 | 5.0 | Peak symmetry restored. Isolates cause to the column. | |

| Fresh Mobile Phase | 1.1 | 5.0 | (Not performed, as problem was resolved) | N/A |

| Conclusion | Root Cause: Column degradation. The original column was exposed to a pH outside its stable range during a previous method development experiment. |

- Solution Implementation & Validation: The degraded column is replaced. A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) is updated to include stricter logging of column usage and pre-use pH checks for all mobile phases.

Communication: The Catalyst for Collaboration and Impact

Precise, audience-tailored communication is the mechanism through which research gains value and utility.

Experimental Protocol: Structuring a Cross-Functional Team Meeting

- Objective: To align the Analytical Development, Process Chemistry, and Formulation teams on a critical stability-indicating method discrepancy.

- Pre-Meeting Information Synthesis:

- For Technical Peers (Analytical Chemists): Prepare detailed chromatograms, statistical analysis of peak area %RSD, and forced degradation study data.

- For Project Managers & Chemists: Create a high-level summary slide focusing on project timeline impact, potential root causes (e.g., excipient interaction), and required resources.

- Agenda & Execution:

- State the Problem (2 min): "The HPLC method for Project X is showing a 15% increase in impurity B after 3-month accelerated stability, but only in the final tablet formulation, not the API alone."

- Present the Data (5 min): Show comparative chromatograms and a summary table.

- Facilitate Hypothesis Generation (10 min): Use a whiteboard to map potential chemical interactions between the API and excipients under stress conditions.

- Define Actionable Next Steps (3 min): Assign tasks: Analytical to develop a LC-MS method for impurity identification; Formulation to provide excipient compatibility data.

- Post-Meeting Follow-up: Distribute meeting minutes with a clear table of action items, owners, and deadlines.

Systems Thinking: Mapping Interdependencies in Drug Development

Systems thinking allows researchers to see their work as part of a larger, interconnected process, anticipating downstream consequences and identifying leverage points for innovation.

Diagram: Systems Map of an Analytical Method Development Workflow

Diagram Title: Analytical Method Development System

This map visualizes how forced degradation studies (a key analytical activity) directly inform method optimization, creating a critical feedback loop. A failure in this node would lead to a non-stability-indicating method, causing regulatory and safety risks downstream.

Diagram: Communication & Problem-Solving Feedback Loop

Diagram Title: Collaborative Problem-Solving Cycle

This diagram illustrates the iterative relationship between communication and problem-solving. The "Collaborative Analysis" node is the nexus where data is interpreted through dialogue, leading to decisions that close the loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Collaborative Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Soft Skill Application

| Item / Tool | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Serves as the single source of truth for experimental data, enabling transparent, auditable, and collaborative problem-solving. |

| Structured Meeting Agendas | A protocol for communication that defines objectives, roles, and time allocations, maximizing meeting efficiency and outcomes. |

| Project Management Software (e.g., Jira, Asana) | Provides a visual system for tracking complex projects, making task interdependencies (systems thinking) explicit for the entire team. |

| Visualization Tools (e.g., Spotfire, Graphviz) | Enables the creation of system maps and data dashboards, facilitating the communication of complex relationships and trends. |

| Decision Matrix | A quantitative framework for problem-solving that weights potential solutions against predefined criteria (e.g., cost, time, risk). |

| gold;silver | gold;silver, CAS:63717-64-6, MF:AgAu, MW:304.835 g/mol |

| lithium;aniline | Lithium;Aniline|C6H6LiN|CAS 62824-63-9 |

Analytical chemistry is the science of obtaining, processing, and communicating information about the composition and structure of matter. It is the art and science of determining what matter is and how much of it exists [17]. This field makes significant contributions to nearly all areas of scientific inquiry and industry, from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, building a career in analytical chemistry requires a strategic combination of formal education, specialized training, and practical skill development.

The employment outlook for analytical chemists remains strong, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting a 6% growth in employment for chemists and materials scientists through 2032, higher than the average for all occupations [27]. This growth is driven by ongoing research in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and environmental science, creating consistent demand for skilled professionals who can perform complex analyses and operate sophisticated instrumentation.

Educational Pathways in Analytical Chemistry

Degree Programs and Their Value

Formal education provides the foundational knowledge necessary for a successful career in analytical chemistry. The depth and specialization of one's education directly correlate with career opportunities and earning potential, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Educational Pathways and Salary Ranges in Analytical Chemistry

| Degree Level | Typical Completion Time | Key Skills Developed | Median Salary Range | Common Career Paths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associate Degree | 2 years | Basic laboratory techniques, safety protocols, sample preparation | $35,649 - $47,503 | Laboratory Assistant, Research Associate, Laboratory Technician [28] |

| Bachelor's Degree | 4 years | Instrument operation, quantitative analysis, data interpretation | $60,604 - $89,000 | Chemist, Materials Scientist, Pharmacologist [28] [27] |

| Master's Degree | 2 years post-baccalaureate | Advanced method development, research design, specialization | $70,587 - $120,000 | Research Chemist, Production Chemist, Chemistry Instructor [28] [27] |

| Doctoral Degree | 4-6 years post-baccalaureate | Independent research, complex problem-solving, leadership | $96,915 - $131,000 | Chemistry Professor, Chemical Engineer, Research Director [28] [27] |

Bachelor's degrees in chemistry typically offer both Bachelor of Arts (BA) and Bachelor of Science (BS) options. The BA provides a broad foundation with flexibility for interdisciplinary study, while the BS emphasizes a more rigorous curriculum with extensive laboratory work and advanced theoretical concepts [29]. For drug development professionals, the BS pathway often provides better preparation for technical roles, though both can lead to successful careers in analytical chemistry.

Graduate education offers significant financial advantages. Master's degree holders typically earn 20-30% more than those with only bachelor's degrees [29]. Doctoral degrees provide the highest earning potential, with median salaries reaching $131,000 for analytical chemists with PhDs [27]. Beyond financial benefits, advanced degrees open doors to research leadership positions and academic appointments.

Specialized Certifications and Credentials

Certifications provide focused, practical training that complements formal education. These credentials demonstrate specific competency areas to employers and can significantly enhance career prospects. For analytical chemists working in regulated industries like pharmaceutical development, certifications in quality systems and specialized techniques are particularly valuable.

Table 2: Key Professional Certifications for Analytical Chemists

| Certification | Issuing Organization | Focus Areas | Experience Requirements | Renewal Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialist in Chemistry (SC(ASCP)) | American Society for Clinical Pathology | Clinical chemistry, laboratory techniques | More than 2 years of work experience | Every 10 years [30] |

| Certified Quality Auditor (CQA) | American Society for Quality | Audit principles, quality systems, standards | More than 2 years of work experience | Every 3 years [30] |

| Certified Chemical Engineer (CCE) | International Certification Commission | Chemical processes, engineering principles | More than 2 years of work experience | Every 3 years [30] |

| Certified Laboratory Technician (CLT) | National Certification Agency | Laboratory operations, testing procedures | Varies by specialization | Varies [31] |

| HPLC Certification | International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering | Chromatography method development, operation | Typically requires demonstration of competency | Varies [31] |

University-based certificate programs also provide valuable specialized training. The University of Toledo offers a 12-credit hour analytical chemistry certificate that incorporates classroom and laboratory courses in analytical chemistry, instrumental analysis, and separation methods [32]. Graduates report that this credential positively differentiated their resumes and contributed to them being chosen over other candidates for positions.

As noted by Dr. Jon Kirchhoff, who developed the UToledo certificate program: "The success students are having to quickly obtain employment in the chemical industry strongly supports the value of the certificate. Analytical skills will always be in high demand." [32]

The Impact of Specialized Training on Career Advancement

Career Opportunities and Specialization Paths

Specialized training in analytical chemistry opens doors to diverse career paths across multiple sectors. The pharmaceutical industry remains a major employer of analytical chemists, who contribute to drug development, quality control, and regulatory compliance. Other significant employment sectors include academia (61% of analytical chemists), industry (25%), and government or military organizations (12%) [27].

The career progression for analytical chemists typically follows one of two primary pathways: a technical specialist track or a research leadership track. The following diagram illustrates these progression pathways and key decision points:

For drug development professionals, specialized training in techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Mass Spectrometry, and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is particularly valuable. As instrumentation becomes more sophisticated, employers increasingly seek analytical chemists with specific experience in these advanced techniques [17].

Salary Enhancement Through Specialized Training

The financial return on investment in specialized training and education is significant across all career stages. According to recent data, analytical chemists with bachelor's degrees earn a median salary of $89,000, while those with master's degrees earn $120,000, and PhD holders command $131,000 [27]. This represents a 47% salary premium for doctoral degrees over bachelor's degrees.

Certifications also contribute to increased earning potential. Analytical chemists with specialized certifications often advance more quickly into senior roles with greater responsibility and compensation. Paige Wlodkowski, a recent graduate who completed an analytical chemistry certificate program, reported that the credential was a key differentiator during job interviews and contributed directly to her being selected for her current position [32].

Another certificate program graduate, Ximena Fernandez-Paucar, noted that her specialized training enabled her to learn her job more quickly and earn a raise in less than a year. "I was able to learn my job pretty quickly because I was already familiar with the instrumentation we used in lab classes I had to take to earn the certificate," she explained [32].

Essential Technical Skills and Methodologies

Core Analytical Techniques

Analytical chemists in drug development and research rely on a comprehensive toolkit of separation, spectroscopic, and quantitative techniques. Mastery of these methods is essential for designing experiments, interpreting results, and troubleshooting analytical challenges.

Table 3: Essential Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Research

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Primary Applications in Drug Development | Key Instrumentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Methods | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Gas Chromatography (GC), Capillary Electrophoresis | Purity analysis, pharmacokinetic studies, metabolite identification | Chromatographs, columns, detectors, autosamplers [3] |

| Spectroscopic Techniques | Mass Spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy | Structure elucidation, quantitative analysis, impurity profiling | Spectrometers, magnets, radiofrequency generators [3] |

| Quantitative Analysis | Titrimetric Analysis, Volumetric Analysis, Calorimetry | Assay development, content uniformity, stability testing | Balances, burettes, calorimeters, pH meters [3] |

| Microscopy and Surface Analysis | Scanning Electron Microscopy, Atomic Force Microscopy | Particle characterization, formulation development, contaminant identification | Microscopes, probes, vacuum systems [3] |

Experimental Design and Workflow

Well-designed analytical procedures follow a systematic workflow that ensures reliable, reproducible results. The methodology for pharmaceutical analysis typically involves sample preparation, instrument calibration, data acquisition, and statistical validation. The following diagram illustrates a generalized analytical workflow for drug development applications:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful analytical chemistry research requires access to specialized materials and reagents. Table 4 details essential components of the analytical chemist's toolkit with specific applications in pharmaceutical research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Common Applications in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | Stationary phase for compound separation | HPLC and GC method development for API and impurity separation |

| Reference Standards | Calibration and method validation | Quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Ionization assistance and calibration | LC-MS method development for metabolite identification |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR spectroscopy without hydrogen interference | Structural elucidation of novel compounds |

| Buffer Solutions | pH control in mobile phases and samples | Maintaining stability of analytes during separation |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemical modification to enhance detection | Improving volatility for GC analysis or detectability for HPLC |

| Quality Control Materials | Verification of analytical method performance | System suitability testing and ongoing method validation |

| Octadeca-7,9-diene | Octadeca-7,9-diene | Octadeca-7,9-diene is an 18-carbon diene for research. This compound is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Mercury;nickel | Mercury;nickel, CAS:62712-31-6, MF:HgNi, MW:259.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Navigating the Evolving Job Market

Current Employment Trends

The job market for analytical chemists is evolving in response to technological advances and industry needs. While automation has reduced demand for routine analysis, it has increased the need for professionals who can troubleshoot complex instruments, interpret sophisticated data, and ensure regulatory compliance [17] [27]. This shift places a premium on problem-solving skills and specialized technical knowledge.

Geographic factors also influence employment opportunities. States with significant pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, including California, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Texas, have the highest concentrations of analytical chemists [27]. These regional hubs offer the greatest number of positions but also feature more competitive job markets.

Networking plays a crucial role in job searches for analytical chemists. According to ACS data, informal channels through colleagues or friends account for 21% of successful job searches, while websites like LinkedIn and Indeed account for 56% [27]. Participating in undergraduate research (29%), summer research programs (21%), and internships (11%) significantly enhances graduates' employment prospects [27].

Future Directions in Analytical Science

Technological innovation continues to reshape analytical chemistry, creating new specializations and career opportunities. Separation science advancements, miniaturized instrumentation, and increased data sophistication are driving evolution in the field. As Monika Sommerhalter of California State University - East Bay notes: "The skill of learning itself! Being able to acquire new skills will become more important as technological progress speeds up." [33]

The growing emphasis on "green" chemistry principles is creating demand for analytical chemists who can develop environmentally sustainable methodologies [33]. Similarly, the expansion of biopharmaceuticals requires analytical professionals with expertise in macromolecule characterization. These emerging specializations represent promising career pathways for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategic educational planning and specialized training are critical for building a successful career in analytical chemistry. Formal degrees provide foundational knowledge, while certifications and focused credentials develop specific technical competencies that enhance employability and earning potential. For drug development professionals and researchers, continuous skill development in advanced instrumentation, regulatory compliance, and emerging methodologies ensures continued relevance in a dynamic field.

The integration of robust educational pathways with strategic professional development creates a powerful framework for career advancement. By aligning training with industry needs and technological trends, analytical chemists can position themselves for rewarding careers with significant impact across the scientific landscape.

Mastering Methods and Applications: Advanced Techniques for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

Analytical chemistry is the branch of chemistry concerned with the development and application of methods to identify the chemical composition of materials and quantify the amounts of components in mixtures [34]. In the contemporary laboratory, the analytical workflow is a systematic process that transforms a chemical question into a reliable, reported result. This process is foundational to fields ranging from pharmaceuticals and biochemistry to forensic science and environmental monitoring [34]. For the modern researcher, proficiency in navigating this end-to-end workflow is a critical career skill, directly impacting the quality, efficiency, and interpretability of scientific data. The advent of automation and sophisticated data analysis tools has further refined these workflows, making them more robust yet complex [35]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step framework for this journey, from the initial problem definition to the final report.

The Analytical Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The entire analytical process can be conceptualized as a cycle of six key stages, each feeding into the next, with data analysis and interpretation acting as the central nervous system for the entire operation. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the critical relationships between its components.

Step 1: Problem Definition and Scoping

The first and most crucial step is to clearly define the analytical problem. A well-articulated problem guides all subsequent decisions.

- Objective: Precisely state what information is needed. Is it the identity of a compound (qualitative analysis), its concentration (quantitative analysis), or the structural elucidation of a new molecule? [34]

- Key Questions:

- What is the analyte (the substance to be measured)?

- What is the expected concentration range?

- What is the sample matrix (the material containing the analyte), and what potential interferences are present?

- What level of accuracy, precision, and detection limit is required?

- How will the results be used, and what regulations or standards must be met?

Step 2: Method Selection and Validation

Based on the problem definition, an appropriate analytical method must be selected and its performance characteristics verified.

- Method Selection: Choose from classical (e.g., titration, gravimetric analysis) or modern instrumental techniques (e.g., spectroscopy, chromatography, mass spectrometry) based on the analyte and required sensitivity [34]. Hybrid techniques like LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) are often selected for their powerful separation and identification capabilities [34].

- Method Validation: The chosen method must be validated to prove it is fit for purpose. Key parameters are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Analytical Method Validation

| Validation Parameter | Description | Typical Protocol / Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of the measured value to the true value. | Analyze samples of known concentration (e.g., certified reference materials) and calculate percent recovery. |

| Precision | Closeness of repeated measurements to each other. | Perform multiple analyses (n≥6) of a homogeneous sample and calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD). |

| Linearity & Range | The ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration over a specific range. | Analyze a series of standard solutions at different concentrations and perform linear regression (y = mx + c). The coefficient of determination (R²) should be >0.99. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration that can be detected. | LOD = 3.3 × (Standard Deviation of the Response / Slope of the Calibration Curve). |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | LOQ = 10 × (Standard Deviation of the Response / Slope of the Calibration Curve). |

| Specificity/Selectivity | The ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of interferences. | Compare chromatograms or spectra of the sample with and without the analyte, or with known interferences present. |

Step 3: Sample Handling and Preparation

The integrity of the analysis is highly dependent on proper sample handling. Errors introduced at this stage cannot be corrected later.

- Sample Collection: Obtain a representative sample using statistically sound sampling plans. Use appropriate containers to avoid contamination or degradation.

- Sample Preservation: Stabilize the sample if analysis is not immediate (e.g., refrigeration, freezing, or adding chemical preservatives).

- Sample Preparation: Transform the sample into a form suitable for analysis. This is often the most time-consuming step and can include:

- Homogenization: Ensuring the sample is uniform.

- Extraction: Isolating the analyte from the matrix (e.g., Liquid-Liquid Extraction, Solid-Phase Extraction).

- Clean-up: Removing interfering substances.

- Pre-concentration: Increasing the analyte concentration to meet detection limits.

- Derivatization: Chemically modifying the analyte to improve its detectability or volatility.

Step 4: Analysis and Data Acquisition

This step involves the actual measurement using the selected and validated instrumental method.

- Instrument Calibration: Before analysis, the instrument must be calibrated using standard solutions of known concentration to establish the relationship between the instrument's response and the analyte concentration. This can involve external standard calibration, internal standard calibration, or the method of standard additions.

- Quality Control (QC): During the analysis run, QC standards (e.g., blanks, continuing calibration verification standards, and control samples) are analyzed at regular intervals to ensure the instrument performance remains stable and the data generated is reliable [35].

- Data Acquisition: The instrument software records the raw data (e.g., chromatograms, spectra, voltammograms).

Step 5: Data Processing, Interpretation, and Chemometrics

Raw data is processed to extract meaningful information, which is then interpreted in the context of the original problem.

- Data Processing: This includes smoothing, baseline correction, peak integration (in chromatography), and spectral deconvolution. Modern software, like Mnova, often automates these workflows for efficiency and reproducibility [35].