Evaluating Transferability of Optimized Force Field Parameters: Strategies for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the transferability of optimized force field parameters in molecular simulations, a critical challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Evaluating Transferability of Optimized Force Field Parameters: Strategies for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the transferability of optimized force field parameters in molecular simulations, a critical challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. We explore foundational principles of transferable force fields, examine cutting-edge methodological approaches including machine learning and modular parameterization, address common troubleshooting scenarios, and establish robust validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from recent advancements, this guide equips researchers with practical strategies to enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and predictive power of molecular simulations across diverse chemical spaces and biological systems.

The Principles and Promise of Transferable Force Fields

In computational materials science, the concept of force field transferability refers to the ability of empirically derived interaction parameters to accurately describe material behavior across different structural configurations and chemical environments without requiring re-parameterization. This capability is particularly valuable for complex porous materials like zeolites and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), where quantum mechanical calculations remain computationally prohibitive for large-scale systems. The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that zeolites, with their relatively consistent SiOâ‚„ and AlOâ‚„ tetrahedral building blocks, often demonstrate higher inherent transferability, while MOFs, with their diverse metal nodes and organic linkers, present significant obstacles for parameter transferability [1] [2]. Evaluating and improving transferability is crucial for accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation materials for applications ranging from carbon capture to drug delivery.

Structural Foundations and Material Classification

The intrinsic transferability of force fields is fundamentally governed by the structural and chemical characteristics of the materials being studied.

Zeolites: A Landscape of Structural Consistency

Zeolites are crystalline microporous materials whose structures consist of tetrahedral TOâ‚„/â‚‚ primary building units (where T = Si, Al, among others) [2]. This consistent chemistry, primarily based on interconnected SiOâ‚„ and AlOâ‚„ tetrahedra, creates a favorable environment for force field transferability. The extensive research history and well-established characterization of zeolites have resulted in reliable, transferable force fields that can accurately predict properties across different zeolite frameworks [1].

Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Challenge of Chemical Diversity

In stark contrast to zeolites, MOFs are organic-inorganic hybrid materials with structures formed through coordination bonds between metal ions/clusters and organic ligands [2]. This combination creates an almost limitless chemical space; the tunability of both metal nodes and organic linkers enables thousands of possible structures but simultaneously complicates force field development [1] [3]. The remarkable diversity of building blocks in MOFs—from common zinc clusters to rare metalloporphyrins and from simple carboxylates to complex biomolecular derivatives—means that parameters developed for one MOF often fail to transfer accurately to another, even when they share similar topological features [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Differences Impacting Force Field Transferability

| Characteristic | Zeolites | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Bonds | Strong covalent (T-O-T) | Coordination bonds + covalent |

| Building Blocks | Limited variety of tetrahedral units | Virtually unlimited metal-ligand combinations |

| Chemical Consistency | High within material classes | Extremely low across framework types |

| Parameter Transfer Success | High between structurally similar frameworks | Limited, even within polymorphic forms |

Experimental and Computational Assessment Methodologies

The Polymorphic Replacement Approach for MOFs

A significant methodological advancement for evaluating force field transferability in MOFs involves the polymorphic replacement strategy [1]. This approach addresses the computational bottleneck of deriving force fields for large MOF structures by leveraging the fact that polymorphs—structures with identical building blocks but different coordination networks—should theoretically share transferable force field parameters.

The experimental protocol involves several critical steps:

- Polymorph Generation: Computationally generate multiple polymorphic structures of the target MOF using topological assembly algorithms [1] [4].

- Structure Selection: Identify a suitable polymorph with a smaller unit cell than the original target structure [1].

- Quantum Chemical Calculations: Perform density functional theory (DFT) simulations on the smaller polymorph to derive reference data for force field parameterization [1].

- Parameter Transfer: Apply the derived force field parameters to the original, larger MOF structure [1].

- Validation: Compare classical simulation results using the transferred force field against quantum chemical calculations for the original structure to assess transferability accuracy [1].

This methodology was successfully demonstrated with MOF-177, where parameters derived from a smaller polymorph accurately predicted interaction energies in the original structure, validating transferability across polymorphic forms [1].

Comparative Evaluation of Mechanical Properties

Another critical assessment approach involves evaluating how well transferred force fields reproduce mechanical properties compared to DFT calculations. Research on ZIF-8 has revealed that many existing classical force fields fail to reproduce non-linear mechanical behavior under pressure, particularly for pressures exceeding 0.2 GPa [5]. Furthermore, significant discrepancies in elastic constant values were observed for the same force field when different energy minimization algorithms were employed, suggesting that eigenmode-following approaches might be necessary to guarantee true minimum energy configurations for accurate mechanical property prediction [5].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Performance Metrics for Zeolites and MOFs

| Material | Structure | Surface Area (m²/g) | CO₂ Adsorption Capacity (mmol/g) | Thermal Stability | Force Field Transferability Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite | 13X | 300-800 [6] | 3.5-5.0 [6] | >800°C [7] | High within zeolite families |

| MOF | MIL-101(Cr) | ~5900 [7] | Up to 8.00 (at 5.3 bar) [7] | Up to 380°C [7] | Moderate to poor across different MOFs |

| MOF | MOF-177 | N/A | N/A | Up to 275°C [1] | Demonstrated across polymorphs [1] |

| Bio-MOF | Various hypothetical | Wide distribution [4] | Varies with structure [4] | Varies with building blocks [4] | Largely unexplored |

Case Studies and Experimental Data Analysis

MOF-177: A Transferability Success Story

The MOF-177 case study provides compelling evidence for force field transferability across polymorphic structures. Researchers successfully demonstrated that parameters derived from a smaller polymorph could accurately describe guest molecule interactions (H₂O and NH₃) in the original MOF-177 structure [1]. This approach dramatically reduced computational costs associated with conventional quantum chemical force field development while maintaining accuracy, establishing a viable pathway for parameterizing large, complex MOF structures that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive [1].

ZIF-8: Highlightting Mechanical Property Challenges

In contrast to the MOF-177 success, evaluation of ZIF-8 flexible force fields revealed significant limitations in transferability for mechanical properties [5]. Multiple existing classical force fields failed to reproduce the non-linear behavior of elastic constants under pressure when compared to DFT reference data [5]. This deficiency underscores the complex relationship between force field parameterization and the prediction of specific material properties, suggesting that transferability may be property-dependent rather than a universal characteristic.

Monolithic Structures: Performance Implications

Beyond atomic-level parameter transfer, research on structured adsorbents provides insights into practical performance implications. Studies comparing MIL-101(Cr) and 13X zeolite monoliths revealed that MIL-101(Cr) monoliths exhibited 1.3 times higher porosity, 20% shorter breakthrough times, and approximately 37% higher COâ‚‚ adsorption capacity at breakthrough compared to 13X zeolite monoliths [7]. These performance advantages demonstrate how material-level characteristics influenced by force field parameterization ultimately manifest in macroscopic application performance.

Successful research into force field transferability requires specialized computational tools and resources.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Force Field Transferability Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Transferability Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Software | Molecular dynamics simulator | Evaluating mechanical properties & validation [5] [4] |

| VASP | Software | Quantum chemical calculations | Generating reference data for force field training [1] |

| Zeo++ | Software | Structure analysis | Calculating pore geometry & structural properties [4] |

| PORMAKE | Software | Structure generation | Assembling MOF structures from molecular building blocks [1] [4] |

| ReaxFF | Force Field | Reactive force field | Describing bond formation/breaking in complex systems [8] |

| UFF | Force Field | Universal force field | Initial structure optimization & screening [4] |

| CoRE MOF | Database | Experimentally-derived MOF structures | Source of validated structures for testing [3] |

| Bio-hMOF Database | Database | Hypothetical biological MOFs | Screening transferability across diverse biological building blocks [4] |

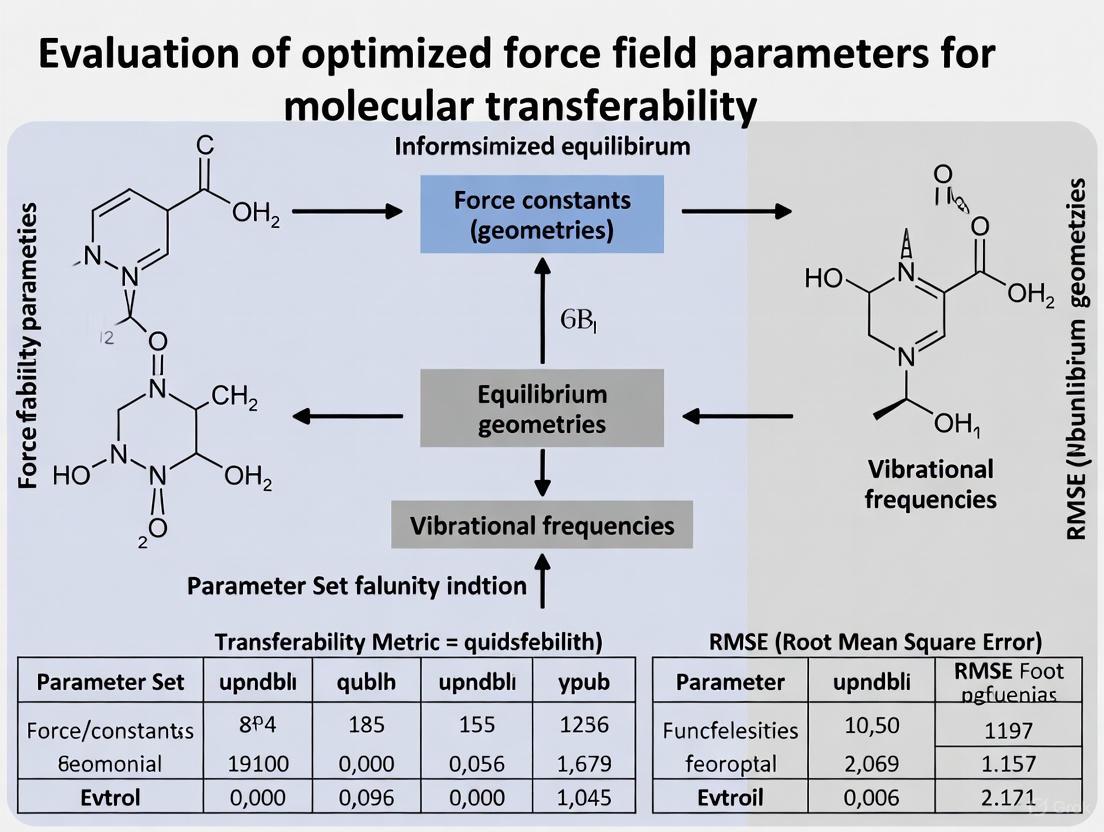

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

Force Field Transferability Assessment Workflow

Zeolite vs. MOF Transferability Characteristics

The transferability of force field parameters represents a critical frontier in computational materials science, with distinct challenges and opportunities for zeolites versus metal-organic frameworks. While zeolites benefit from inherent structural consistency that facilitates parameter transferability, MOFs present a more complex landscape where transferability is currently limited but demonstrably achievable through innovative approaches like polymorphic replacement. Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated force field optimization frameworks [8], expanding transferability assessments to emerging Bio-MOF categories [4], and establishing standardized validation protocols for evaluating transferability across material classes. As computational screening continues to drive materials discovery [3], improving force field transferability will remain essential for accurately predicting material behavior and accelerating the development of advanced porous materials for energy, environmental, and biomedical applications.

Transferable force fields are the foundational blueprints for molecular simulation, providing a reusable set of parameters to model intermolecular and intramolecular interactions across diverse chemical spaces. Unlike component-specific force fields, which are tailored for a single substance, transferable force fields act as generalized chemical construction plans for entire classes of molecules, specifying interactions between defined atom types or chemical groups [9]. Their architecture enables researchers to build component-specific models for molecules not originally present in the parametrization data, making them powerful tools for predictive simulation in drug development and materials science. The core challenge in force field science lies in balancing specificity with transferability; highly specific models may offer precision for trained systems but often fail to generalize, whereas simpler, more transferable models can sometimes deliver superior performance across a wider range of unseen molecules and properties [10].

The evolution of these tools has entered a transformative phase with the integration of machine learning (ML). Traditional empirical force fields, which have dominated the field for decades, rely on fixed parametric forms and pre-defined atom types. In contrast, emerging ML-based force fields use advanced algorithms to learn the potential energy surface from quantum mechanical data, offering a fundamentally different architecture for molecular modeling [11] [12]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these approaches, evaluating their performance, computational requirements, and suitability for different research applications in pharmaceutical and scientific development.

Comparative Analysis of Force Field Architectures

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The accuracy of force fields is rigorously assessed against experimental measurements and high-level quantum calculations across various physical properties. The following table summarizes benchmark results for key force field types, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Force Field Types

| Force Field Type | Liquid Density Error (%) | Enthalpy of Vaporization Error (%) | Dihedral Scans / Structural Accuracy | Computational Cost (Relative to Traditional FF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (OPLS-AA) [11] | ~1-5% (systematic deviations common) | ~2-6% | Good for parametrized fragments; may fail for novel chemistries | 1x (Baseline) |

| Machine Learning (NPLS) [11] | Significantly improved agreement with experiment after nuclear quantum corrections | Improved agreement with experiment | High accuracy for unseen molecules | ~10-1000x higher than traditional FF |

| Machine Learning (MACE-OFF) [12] | Accurate predictions for molecular liquids | Accurate predictions for molecular liquids | Accurate, easy-to-converge scans for unseen molecules | Highly optimized; enables protein simulations |

| Less-Specific/Transferable [10] | Saturation in accuracy for trained properties | Saturation in accuracy for trained properties | Marginal benefit vs. complex FFs; better for off-target properties | Lower data requirements |

Architectural Comparison and Specifications

The fundamental design choices of a force field—its level of atomistic detail, functional form, and parametrization strategy—define its architectural class and application domain.

Table 2: Architectural Specifications of Force Field Types

| Architectural Feature | Traditional Empirical (e.g., OPLS-AA, TraPPE) | Machine Learning (e.g., MACE-OFF, NPLS) |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Approach | Transferable construction plan based on atom types [9] | Data-driven model trained on quantum mechanical references [11] [12] |

| Common Detail Level | All-atom or united-atom [9] | All-atom |

| Functional Form | Fixed mathematical equations (e.g., Lenn-Jones, harmonic bonds) [9] | Flexible, complex functions (e.g., neural networks, transformers) [11] [12] |

| Parametrization Data Source | Mix of experimental data and quantum calculations [9] | High-level quantum mechanical (DFT, CCSD(T)) calculations [11] [12] |

| Transferability Mechanism | Pre-defined, human-specified atom types and rules [9] | Generalization learned from chemical space in training data [12] |

| Typical Application Scale | Biomolecular simulations, fluid properties [9] [12] | From small molecules to solvated proteins [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Evaluation

A standardized experimental protocol is essential for the objective comparison of force fields. The following workflow and methodologies are commonly employed in rigorous benchmarks.

Protocol Workflow Description

The experimental workflow for force field evaluation involves a cyclic process of training/parametrization and validation [11] [10]. Researchers first define the target chemical space, such as the alkane family or a set of drug-like molecules [11]. Reference data is then generated, typically from high-level quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., DFT or CCSD(T)) for energies and forces, and from experimental measurements for bulk properties [11] [12]. The force field is subsequently parametrized (for traditional FFs) or trained (for ML FFs) on a portion of this data. Molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are run using the prepared force field to compute the properties of interest [9]. Finally, the simulation results are rigorously compared against the held-out reference data to assess accuracy and transferability.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Dual-Space Active Learning for ML Force Fields: This methodology, used for developing models like NPLS, involves an active learning workflow that efficiently samples both configurational and chemical space [11]. A query-by-committee method is often employed, where multiple models form a "committee." Molecular configurations for which the committee disagrees most strongly are identified as candidates for additional quantum mechanical calculation. This strategy targets the most informative data points, improving model accuracy and transferability with fewer, more valuable training examples [11].

Liquid Property Benchmarking: To assess performance for condensed-phase systems, researchers simulate a panel of organic liquids (e.g., 87 organic molecules at 146 distinct state points [10]). Key thermodynamic properties such as density and enthalpy of vaporization are calculated from the simulations using statistical mechanical formulations. The results are then compared directly against experimental measurements to quantify error. Notably, for ML potentials like NPLS, path-integral molecular dynamics (PI-MD) can be used to incorporate nuclear quantum fluctuations, which has been shown to significantly improve agreement with experimental liquid densities [11].

Dihedral Scans and Intramolecular Transferability: This experiment tests a force field's ability to accurately describe internal rotations and conformational energies. The torsional angle of a specific bond is systematically rotated, and the single-point energy is calculated at each step [12]. The resulting potential energy surface is compared against a quantum mechanical benchmark. Accurate dihedral scans for molecules not included in the training set are a strong indicator of robust transferability, a key advantage demonstrated by modern ML force fields like MACE-OFF [12].

Biomolecular Simulation Stability Test: For force fields targeting biological applications, extended molecular dynamics simulations of peptides or proteins in explicit solvent are performed [12]. The stability of the simulation (e.g., no unphysical bond breaking or explosion) and the ability to capture known structural features, such as protein folding or peptide secondary structure, are critical qualitative benchmarks. This test evaluates the force field's performance at the scale and complexity required for drug discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The development and application of transferable force fields rely on a suite of software tools, databases, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Force Field Research and Application

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| TUK-FFDat [9] | Data Format | Standardized scheme for storing transferable force field parameters. | Enables interoperable data exchange; machine-readable. |

| MoSDeF [9] | Software Platform | Automates atom typing and system setup for molecular simulation. | Supports multiple force fields; enhances reproducibility. |

| OpenMM [9] [12] | Simulation Engine | Performs high-performance MD simulations, often with GPU acceleration. | Flexible; supports custom forces; integrates with ML potentials. |

| LAMMPS [12] | Simulation Engine | A versatile classical MD simulator with a large library of force fields. | Highly scalable for large systems; supports ML potentials via plugins. |

| MACE Architecture [12] | ML Model | A state-of-the-art equivariant graph neural network for building ML force fields. | High accuracy and data efficiency; demonstrated transferability. |

| ANI-2x [12] | ML Force Field | A widely used transferable ML potential for organic molecules. | Pioneered the use of large datasets for chemical generalization. |

| Antitumor agent-78 | Antitumor agent-78, MF:C13H19F3N2O5Pt, MW:535.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| KRAS G12C inhibitor 58 | KRAS G12C inhibitor 58, MF:C51H64ClF4N9O8S, MW:1074.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The architectural evolution of transferable force fields is moving toward a hybrid paradigm that marries the data-driven accuracy of machine learning with the physical rigor and interpretability of traditional empirical forms. Evidence suggests that for a wide range of properties, highly complex, less-transferable force fields do not necessarily provide superior accuracy and can perform worse on off-target properties, highlighting a key trade-off between specificity and generalizability [10]. Meanwhile, ML force fields like NPLS and MACE-OFF demonstrate that models trained on high-quality quantum data can achieve remarkable transferability, accurately predicting properties from gas-phase torsions to condensed-phase behavior and even enabling stable simulations of solvated proteins [11] [12]. The development of standardized data schemes, such as TUK-FFDat, will be crucial for ensuring interoperability and reproducibility as these diverse force field architectures continue to mature [9]. For researchers in drug development, the choice of force field architecture is no longer binary; it requires a strategic decision based on the specific target properties, the required level of accuracy, the available computational resources, and the importance of model interpretability in their scientific workflow.

The accuracy of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in drug discovery is fundamentally constrained by the force fields that describe the underlying potential energy surface. The core challenges of specificity (accurate description of diverse chemical entities), applicability (transferability across chemical space), and computational cost (balance between accuracy and efficiency) remain central to force field development. This guide objectively compares contemporary force field parameterization strategies—classical molecular mechanics (MM), machine learning force fields (MLFFs), and quantum mechanically derived force fields (QMD-FFs)—evaluating their performance against these critical benchmarks. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on parameter transferability, providing researchers with a quantitative foundation for selecting force fields appropriate to their specific scientific inquiry.

Performance Comparison of Force Field Paradigms

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of different force field classes, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations concerning specificity, applicability, and computational cost.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Force Field Paradigms for Drug Discovery Applications

| Force Field Paradigm | Representative Examples | Specificity / Accuracy | Applicability / Transferability | Computational Cost | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Molecular Mechanics (MM) | ByteFF [13], OPLS-AA, GAFF [9] | Moderate; limited by fixed functional forms. Accurate for equilibrium geometries but can struggle with torsional profiles and non-bonded interactions [13]. | High for covered chemical space, but requires extensive parameter libraries. | Low; highly efficient for large-scale/long-timescale biomolecular simulations [13]. | High-throughput screening, simulation of large biomolecular systems (proteins, DNA). |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | MACE-OFF [14], GNN-based potentials [15] | High; can approach ab initio accuracy for energies and forces [14]. | Good, but highly dependent on training data diversity. Performance drops for configurations not represented in training set [15]. | Moderate to High; more expensive than MM, but far cheaper than QM. Enables nanosecond-scale protein simulations [14]. | Systems where quantum accuracy is needed for properties like molecular crystals, peptide folding, and liquid structure [14]. |

| Quantum Mechanically Derived Force Fields (QMD-FFs) | JOYCE3.0 [16], AIM-based methods [17] | Very High; excellent agreement with higher-level theory for structures, condensed-phase properties, and spectroscopy [16]. | Environment-specific; parameters are derived for the specific system, ensuring high accuracy but limiting direct transferability [17]. | High (parameterization) to Moderate (simulation); cost is front-loaded in the parameterization process. | Detailed investigation of specific molecular systems, spectroscopic prediction, and design of advanced materials [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Transferability

Rigorous validation is essential for assessing the real-world performance and transferability of force fields. The following protocols detail standard benchmarking methodologies.

Intramolecular Conformational Energy Validation

Objective: To evaluate a force field's accuracy in describing the intramolecular potential energy surface (PES), which is critical for predicting conformational distributions [13].

Protocol:

- Dataset Curation: Select a diverse set of drug-like molecules and their molecular fragments, ensuring broad coverage of chemical space (e.g., from ChEMBL and ZINC20 databases) [13].

- Quantum Mechanical Reference: Perform geometry optimizations and torsional scans for each molecule/fragment at a high level of quantum mechanical theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) to generate reference energies and optimized geometries [13].

- Force Field Evaluation: For the same set of molecules and conformations, calculate single-point energies and optimized geometries using the target force field.

- Metrics: Quantify accuracy by calculating the root-mean-square error (RMSE) between force field and QM energies, and the deviation of optimized bond lengths and angles from QM references [13].

Condensed-Phase and Biomolecular Property Validation

Objective: To test transferability and robustness in simulating bulk properties and complex biomolecular behavior [14] [15].

Protocol:

- Liquid Property Prediction: Simulate molecular liquids (e.g., water, organic solvents) and calculate properties such as density and heat of vaporization. Compare results with experimental data [14].

- Molecular Crystal Lattice Prediction: Perform geometry optimization on molecular crystals and compare predicted lattice parameters and enthalpies of formation with experimental crystallographic data [14].

- Biomolecular Dynamics: Run microsecond-to-nanosecond-scale MD simulations of peptides and proteins.

- Analysis: Monitor simulation stability, calculate conformational properties (e.g., J-coupling constants for peptides), and assess the ability to reproduce known behavior, such as peptide folding [14].

- Advanced Solid-Phase Benchmarking (for MLFFs):

Figure 1: A comprehensive workflow for benchmarking force field transferability, integrating both intramolecular and condensed-phase validation protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful development and application of advanced force fields rely on a suite of specialized software tools and databases.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Simulation Engine | A highly versatile and scalable MD simulator. | Computational Cost: Enables efficient large-scale simulations with various force fields [14] [15]. |

| OpenMM | Simulation Engine & Toolkit | An open-source library for high-performance MD simulations, especially on GPUs. | Computational Cost: Provides accelerated performance for complex force fields, including MLFFs [14] [9]. |

| geomeTRIC | Computational Chemistry | An optimizer for molecular geometries using QM calculations. | Specificity: Generates accurate reference data (optimized geometries, Hessians) for force field training [13]. |

| ChEMBL / ZINC20 | Database | Curated databases of bioactive molecules and commercially available compounds. | Applicability: Provides source molecules for building diverse, drug-like training and test sets [13]. |

| TUK-FFDat | Data Format | An SQL-based, machine-readable data scheme for transferable force fields. | Applicability: Promotes interoperability and reusability of force field parameters, enhancing transferability research [9]. |

| GCNCMC | Sampling Algorithm | A Monte Carlo method for grand canonical ensemble sampling. | Specificity/Computational Cost: Improves sampling of fragment binding in drug discovery, overcoming MD timescale limits [18]. |

| ForceBalance | Parametrization Tool | An automated tool for systematic optimization of force field parameters. | Specificity: Uses Bayesian inference to fit parameters against diverse QM and experimental data, improving accuracy [17]. |

| p-Toluic acid-d4 | p-Toluic Acid-d4|4-Methylbenzoic Acid-d4 | p-Toluic acid-d4 is a deuterium-labeled benzoic acid for quantitative tracer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| D-Arabitol-13C-2 | D-Arabitol-13C-2, MF:C5H12O5, MW:153.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The choice of a force field strategy involves a fundamental trade-off between specificity, applicability, and computational cost. Classical MM force fields like ByteFF offer an efficient and transferable solution for high-throughput applications and large biomolecular systems. Machine learning force fields like MACE-OFF deliver quantum-mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the cost, making them ideal for properties sensitive to electronic effects, though their transferability is intrinsically linked to training data quality. Environment-specific QMD-FFs from tools like JOYCE3.0 provide the highest specificity for targeted investigations but require significant computational investment and lack direct transferability. A critical finding for MLFFs is that their transferability cannot be assumed; comprehensive benchmarking across solid and liquid phases is mandatory [15]. The ongoing development of standardized data formats [9] and robust validation protocols ensures that the field continues to advance toward the goal of truly predictive molecular simulation in drug discovery.

Classical atomistic simulations are an established tool for investigating condensed-phase systems across computational physics, physical chemistry, molecular biology, and engineering [9]. The accuracy of these molecular dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations depends critically on the quality of the underlying potential-energy function or force field [19]. Force fields are mathematical descriptions of molecular interactions composed of parametric equations and corresponding parameter values [9].

A fundamental way to classify force fields is by their level of resolution, which determines which atoms are explicitly represented as interaction sites. The three primary resolutions are all-atom (AA), united-atom (UA), and coarse-grained (CG) models [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and applicability to molecular simulations, particularly within the context of force field transferability research.

Classification and Theoretical Foundations

Force fields can be systematically classified based on multiple attributes, including modeling approach, model detail level, interaction potential types, and parametrization approach [9]. The model resolution represents a key functional-form variant (FFV) that significantly influences force field accuracy and computational efficiency [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Force Field Representations

| Feature | All-Atom (AA) | United-Atom (UA) | Coarse-Grained (CG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | All atoms explicitly represented | Heavy atoms and polar hydrogens explicitly represented; aliphatic hydrogens merged | Multiple heavy atoms grouped into single interaction sites |

| Representation of CH₃ group | C and 3 H atoms as separate interaction sites | Single particle with mass of 15 g/mol [20] | Multiple monomers may be represented as single bead [21] |

| Degrees of freedom | Highest | Reduced (∼2-3x fewer sites than AA) | Drastically reduced (∼10x fewer sites than AA) |

| Computational cost | Highest | Moderate | Lowest |

| Common time step | ~1 fs | ~1-2 fs | ~10-20 fs |

| Target systems | Small molecules, detailed biomolecular studies | Larger systems, membrane proteins, polymers | Large-scale biomolecular complexes, polymer dynamics, materials |

Figure 1: Force Field Classification System and Characteristics

All-Atom (AA) Representation

All-atom force fields explicitly represent every atom in the system, including all hydrogen atoms. This approach preserves atomic detail and potentially offers higher accuracy in representing molecular geometry and interactions, particularly for hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions [19]. The explicit representation of all atoms comes at the cost of increased computational demand due to greater degrees of freedom and faster bond vibrations that limit integration time steps [20].

United-Atom (UA) Representation

United-atom models represent aliphatic carbon and hydrogen groups (e.g., CH, CH₂, CH₃) as single interaction sites, while preserving explicit representation for polar hydrogens and heavy atoms [19]. This representation was introduced early in molecular simulation history, partly due to compatibility with X-ray crystallography data that often lacked hydrogen coordinates [19]. UA models reduce the number of explicit interaction sites by approximately 2-3 times compared to AA models, with corresponding reductions in computational cost [19]. The elimination of fast aliphatic C-H bond vibrations also permits slightly longer integration time steps in molecular dynamics simulations [20].

Coarse-Grained (CG) Representation

Coarse-grained models represent multiple heavy atoms as single interaction sites or "beads," dramatically reducing system complexity [9]. For example, in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), CG models may represent entire monomer units as single beads [21]. This level of abstraction enables simulations of larger systems and longer timescales, making CG approaches particularly valuable for studying polymer dynamics, membrane systems, and large biomolecular complexes [21] [20]. The development of transferable CG models compatible with frameworks like Martini 3 facilitates the study of interactions between different molecular species across a broad chemical space [21].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Accuracy Assessment for Alkanes

Systematic studies comparing force field performance for n-alkanes provide valuable insights into the relative strengths of different representations. Research examining liquid properties of alkanes across different chain lengths has revealed that united-atom models can achieve comparable or even better accuracy than all-atom models for many liquid-phase properties [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AA vs UA Force Fields for n-Alkanes [22]

| Property | Best Performing Model Type | Specific Best Performer | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | United-Atom | GROMOS-UA | UA models systematically better than AA across temperature range (263.15-573.15 K) |

| Heat of Vaporization | United-Atom | GROMOS-UA | Comparable accuracy between best UA and AA models |

| Surface Tension | Mixed | GROMOS-UA (UA) & L-OPLS (AA) | Both representations can achieve comparable accuracy |

| Viscosity | United-Atom | GROMOS-UA | UA models showed superior performance |

| Overall Ranking | United-Atom | GROMOS-UA | UA models performed systematically better for liquid-phase properties |

A comprehensive assessment of force fields for n-alkanes considering different chain lengths found that "united-atoms models led to comparable or even better results than all-atom models in reproducing the properties of liquid phases of alkanes" [22]. The study, which evaluated density, heat of vaporization, surface tension, and viscosity across temperatures from 263.15 to 573.15 K, concluded that "the united-atom GROMOS force field performed systematically better than the other force fields in reproducing the liquid-phase properties of the considered alkane molecules" [22].

Systematic Comparison of UA vs AA Representations

A rigorous 2022 study directly compared united-atom and all-atom representations for saturated acyclic (halo)alkanes using the CombiFF approach, which enables comparison at optimal parameterization against the same experimental data [19]. The research optimized both UA and AA force field versions against 961 experimental values for pure-liquid densities (Ïliq) and vaporization enthalpies (ΔHvap) of 591 compounds [19].

Table 3: Extended Property Comparison Between Optimized UA and AA Force Fields [19]

| Property Category | Relative Performance (AA vs UA) | Specific Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Target Properties | Comparable accuracy | Liquid density (Ïliq), Vaporization enthalpy (ΔHvap) |

| AA More Accurate | AA superior | Shear viscosity (η) |

| Comparable Accuracy | No significant difference | Surface tension (γ), Isothermal compressibility (κT), Thermal expansion (αP), Dielectric permittivity (ϵ), Self-diffusion (D), Solvation free energy in cyclohexane (ΔGche) |

| UA More Accurate | UA superior | Isobaric heat capacity (cP), Hydration free energy (ΔGwat) |

For the target properties (Ïliq and ΔHvap), the optimized UA and AA representations "reach very similar levels of accuracy after optimization" [19]. When extended to other properties not included in the parameterization targets, the AA representation showed superior performance for shear viscosity (η), comparable accuracy for multiple properties including surface tension, compressibility, thermal expansion, dielectric permittivity, self-diffusion, and solvation free energy in cyclohexane, but less accurate results for isobaric heat capacity and hydration free energy [19].

Methodologies and Workflows

Force Field Development and Conversion

The development of systematic workflows for creating and converting between different resolution models represents an important advancement in force field methodology. Tools like AA2UA demonstrate automated approaches for converting all-atom models to their united-atom counterparts [23].

AA2UA is an open-source software that converts PDB files into LAMMPS-readable structure topology files, implementing mapping rules, bead types, charges, and masses according to specific UA force field requirements [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for complex systems like bituminous materials where computational efficiency gains from reduced representations are significant [23].

Figure 2: United-Atom Model Conversion Workflow

Coarse-Grained Model Development

The development of transferable coarse-grained models follows systematic parameterization approaches. For polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Cambiaso et al. developed a Martini 3-compatible CG model using structural and thermodynamic properties as targets, including experimental free energies of transfer [21]. Their approach involved:

- Atomistic Reference Simulations: Initial all-atom simulations of PDMS melt to establish baseline structural properties (density, gyration radius) [21]

- Bonded Interaction Parameterization: Using the reference atomistic simulations to parameterize CG bonded interactions [21]

- Non-Bonded Interaction Optimization: Tuning non-bonded interactions to reproduce thermodynamic properties and transfer free energies [21]

- Transferability Validation: Testing the model across different environments (melt, good solvent, bad solvent) and with different molecule types [21]

For crosslinked PDMS systems, Khot et al. employed iterative Boltzmann inversion (IBI) to develop a CG model from united-atom reference data, creating a hierarchical modeling approach that connected fundamental chemical features with macroscale properties [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for Force Field Development and Application

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | LAMMPS [23] [20], GROMACS [22] | Molecular dynamics engines for evaluating force field performance |

| Conversion Tools | AA2UA [23] | Converts all-atom PDB files to united-atom representations for LAMMPS |

| Force Field Databases | TUK-FFDat [9], OpenKIM [9], MoSDeF [9] | Structured databases for transferable force field parameters |

| Parameterization Tools | CombiFF [19], Iterative Boltzmann Inversion [20] | Automated approaches for force field parameter optimization |

| Reference Data | Experimental pure-liquid densities [19], vaporization enthalpies [19], quantum-mechanical rotational profiles [19] | Target data for force field parameterization and validation |

| Topoisomerase I inhibitor 4 | Topoisomerase I inhibitor 4, MF:C23H19FN4O, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antileishmanial agent-13 | Antileishmanial agent-13|For Research Use | Antileishmanial agent-13 is a research compound for studying leishmaniasis. It is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

Data Schemes and Interoperability

The development of generalized data schemes for transferable force fields addresses significant challenges in force field transparency, reproducibility, and interoperability [9]. The TUK-FFDat scheme provides an SQL-based format that is machine-readable, reusable, and interoperable, supporting both all-atom and united-atom transferable force fields [9]. Such standardized approaches facilitate more reliable comparisons between different force field representations and enhance the reproducibility of molecular simulations.

The choice between all-atom, united-atom, and coarse-grained force field representations involves important trade-offs between computational efficiency and representational accuracy. United-atom models frequently achieve comparable or sometimes better accuracy than all-atom models for many liquid-phase properties of organic compounds, while offering significant computational advantages [19] [22]. Coarse-grained models enable access to larger length and timescales, with ongoing developments improving their transferability across different chemical environments [21].

The transferability of optimized force field parameters depends critically on consistent parameterization approaches and systematic validation across multiple property types. Automated parameterization tools like CombiFF [19] and conversion utilities like AA2UA [23] support more rigorous comparisons between different representations. Standardized data schemes [9] further enhance the reproducibility and interoperability of force field research, facilitating more reliable assessments of different modeling approaches for specific application domains.

In molecular modeling, a transferable force field acts as a generalized chemical construction plan, specifying intermolecular and intramolecular interactions between different types of atoms or chemical groups rather than for a single specific substance [9]. The quality of molecular simulation results—whether for drug discovery, materials science, or biological systems—depends primarily on the quality of the employed force field [9]. However, a core challenge lies in ensuring that these force fields maintain accuracy when applied beyond their original parameterization conditions, a property known as transferability [24].

The evaluation of transferability is not monolithic; it requires assessing performance across different dimensions. A force field might demonstrate excellent thermodynamic transferability (across state points) but poor chemical transferability (across different molecular species), or vice-versa [9] [24]. This guide systematically compares benchmarking criteria and methodologies used to evaluate transferability across force field types, providing researchers with a structured framework for objective assessment. By establishing standardized evaluation protocols, we enable more rigorous development of force fields capable of reliable performance across expansive chemical spaces and diverse thermodynamic conditions.

Defining the Transferability Landscape: A Framework for Evaluation

Force fields can be systematically classified based on key attributes that inherently influence their transferability potential. Understanding this landscape is crucial for selecting appropriate benchmarking strategies.

Table: Classification Framework for Force Field Transferability

| Classification Attribute | Categories | Impact on Transferability |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Approach | Component-Specific | High accuracy for target system, limited transferability [9] |

| Transferable | Broader applicability, potential accuracy trade-offs [9] | |

| Model Detail Level | All-Atom | High-detail, computationally expensive [9] |

| United-Atom | Moderate abstraction, improved efficiency [9] | |

| Coarse-Grained | High abstraction, enables large-scale simulation [9] [24] | |

| Parametrization Approach | Top-Down (Fit to experimental data) | Ensures macroscopic property accuracy [24] |

| Bottom-Up (Fit to quantum mechanical data) | Preserves microscopic, first-principles consistency [24] [13] |

A critical challenge in transferability, particularly for coarse-grained models, is the transferability problem: models optimized at a specific thermodynamic state point often perform poorly outside those conditions [24]. This occurs because the effects of the removed degrees of freedom are themselves functions of thermodynamic conditions [24]. Consequently, a comprehensive benchmarking protocol must evaluate performance across multiple axes, including chemical diversity, thermodynamic states, and target properties.

Figure 1: Multidimensional framework for evaluating force field transferability across chemical space, thermodynamic conditions, and property prediction.

Quantitative Benchmarks: Comparative Performance Metrics Across Force Fields

Rigorous benchmarking requires quantitative metrics that enable direct comparison between force fields. These metrics typically evaluate accuracy against reference data from experiments or high-level quantum mechanical calculations.

Performance in Biomolecular Systems

For protein force fields, agreement with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) observables serves as a critical benchmark. The ff99SB force field, for instance, demonstrates excellent agreement with experimental order parameters and residual dipolar couplings [25]. When evaluated using scalar J-coupling constants for short polyalanines—sensitive probes of local backbone conformation—ff99SB achieved χ² values below 2.0, ranking it among the best performing models for these systems [25]. The choice of solvent model also impacts performance, with TIP4P-Ew providing a 3-16% reduction in deviation from experiment compared to TIP3P in these tests [25].

Performance in Drug-like Molecule Coverage

For small molecule force fields, accuracy across expansive chemical space is paramount. Recent data-driven approaches like ByteFF, trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragments and 3.2 million torsion profiles, demonstrate state-of-the-art performance in predicting relaxed geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies [13]. Such extensive benchmarking across diverse chemical spaces ensures force field parameters are dominated by local structures, enabling consistent transfer from small molecules to similar structural motifs in larger systems [13].

Table: Key Quantitative Metrics for Force Field Benchmarking

| Metric Category | Specific Observables | Force Field Comparison | Experimental/Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties | NMR Scalar Coupling Constants (J-couplings) | ff99SB shows excellent agreement (χ² < 2.0 for Ala₅) [25] | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [26] [25] |

| Residual Dipolar Couplings | ff99SB dynamics comparable to best static structural models [25] | NMR in Aligning Media [25] | |

| Protein Backbone Dihedral Distributions | ff99SB improves secondary structure balance vs. ff94 [25] | Room Temperature Protein Crystallography [26] | |

| Energetic Properties | Torsional Energy Profiles | ByteFF excels in accuracy across diverse chemical space [13] | Quantum Mechanics (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) [13] |

| Conformational Energies & Forces | ByteFF demonstrates state-of-the-art performance [13] | Quantum Mechanics [13] | |

| Thermodynamic Properties | Density, Free Energies | ML CG force fields show improved temperature transferability [24] | Experimental Measurements / All-Atom Simulation [24] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Assessing Transferability

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for consistent and reproducible evaluation of force field transferability. Below are detailed methodologies for key benchmarking experiments.

NMR Data Validation Protocol

Objective: To validate force field accuracy against experimental NMR observables that probe structure and dynamics [26] [25].

- System Preparation: Solvate the protein or peptide of interest in a water box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P-Ew) with appropriate ions to simulate physiological conditions.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform extensive MD simulations (e.g., replica-exchange MD for enhanced sampling) using the force field being evaluated [25].

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate NMR observables from the simulation trajectory:

- Scalar J-Couplings: Compute using Karplus equations (e.g., employing DFT1, DFT2, or Original parameter sets) from sampled backbone dihedral angles [25].

- Order Parameters (S²): Determine from the analysis of bond vector fluctuations.

- Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs): Calculate from the average molecular alignment.

- Statistical Comparison: Quantify agreement with experimental data using statistical measures such as χ² values or root-mean-square deviations (RMSD) [25].

Thermodynamic Transferability Assessment

Objective: To evaluate coarse-grained force field performance across varying thermodynamic conditions (temperature, density) [24].

- Training Data Generation: Run all-atom simulations at multiple state points (temperatures, densities) to generate reference data for forces and/or configurations.

- Force Field Parametrization: Employ machine learning approaches like Hierarchically Interacting Particle Neural Networks (HIP-NN) or traditional force-matching to develop the CG force field using data from either single or multiple state points [24].

- Cross-State-Point Validation: Simulate the CG model at state points not included in the training data.

- Property Calculation: Compare structural properties (radial distribution functions), thermodynamic properties (density, pressure), and potential of mean force (PMF) between CG predictions and reference all-atom data [24].

Chemical Space Coverage Evaluation

Objective: To assess force field performance across diverse drug-like molecules [13].

- Dataset Curation: Generate a large, diverse set of molecular fragments from databases like ChEMBL and ZINC, covering a wide range of chemical functionalities [13].

- Quantum Mechanical Reference: Optimize molecular geometries and compute torsional profiles at a consistent QM level (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) to create a reference dataset [13].

- Force Field Parameter Prediction: Use graph neural networks (GNNs) or traditional methods to assign parameters for all molecules in the test set.

- Accuracy Assessment: Calculate deviations between force field predictions and QM reference data for molecular geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies [13].

Figure 2: Generalized experimental workflow for force field transferability benchmarking.

Essential Research Toolkit for Transferability Studies

Successful evaluation of force field transferability relies on specialized software tools, databases, and computational resources.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Transferability Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| LAMBench [27] | Benchmarking System | Evaluates Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) on generalizability, adaptability, and applicability across domains. |

| TUK-FFDat [9] | Data Scheme/SQL Format | Provides interoperable data format for transferable force fields, enabling consistent comparison. |

| HIP-NN-TS [24] | Machine Learning Architecture | Develops transferable coarse-grained force fields via automated training pipeline. |

| ByteFF Training Dataset [13] | QM Dataset | Offers 2.4M optimized fragments & 3.2M torsion profiles for benchmarking small molecule force fields. |

| OpenMSCG [24] | Software | Generates traditional two-body effective potentials for comparison against ML approaches. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) [13] | ML Model | Predicts MM parameters directly from molecular structure; ensures permutational and chemical invariance. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer [13] | Computational Tool | Optimizes molecular geometries at specified QM level for reference data generation. |

| Mtb-IN-3 | Mtb-IN-3|Anti-Tuberculosis Research Compound | Mtb-IN-3 is a potent compound for research into Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Atr-IN-29 | Atr-IN-29 is a potent, selective ATR kinase inhibitor for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The benchmarking of force field transferability requires a multifaceted approach that integrates validation against experimental data, testing across thermodynamic conditions, and evaluation over expansive chemical spaces. No single metric suffices; rather, comprehensive assessment requires multiple lines of evidence from both bottom-up (quantum mechanical) and top-down (experimental) references.

The most promising developments in this field leverage machine learning to enhance transferability. For instance, graph-convolutional neural networks like HIP-NN-TS demonstrate improved thermodynamic transferability for coarse-grained models [24], while data-driven approaches like ByteFF provide unprecedented coverage of drug-like chemical space [13]. Furthermore, standardized benchmarking systems like LAMBench are emerging to systematically evaluate generalizability, adaptability, and applicability across diverse atomistic systems [27].

As force field development continues to evolve, the adoption of consistent benchmarking protocols, interoperable data formats [9], and comprehensive evaluation metrics will be crucial for developing truly transferable force fields that reliably accelerate scientific discovery and drug development.

Advanced Parameterization Techniques and Real-World Applications

The development of accurate force fields is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which are essential tools in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. Traditional force fields, based on fixed mathematical forms parameterized for specific systems, often face a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy, particularly for complex molecular interactions and chemical reactions. The emergence of machine learning (ML), and specifically Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), has initiated a paradigm shift. GNNs can learn the complex relationship between a molecule's structure and its potential energy surface directly from high-quality quantum mechanical data, promising to combine the accuracy of ab initio methods with the speed of classical molecular mechanics.

A critical challenge for any novel force field is its transferability—the ability to make accurate predictions for molecules, states, or properties not included in its training data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary GNN architectures for force field prediction, evaluating their performance, computational demands, and crucially, their transferability, to aid researchers in selecting and developing robust models for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of GNN Force Field Architectures

Various GNN architectures have been adapted and developed for force field prediction. Their designs incorporate different strategies to handle the physical symmetries inherent in molecular systems, such as rotation and translation invariance.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of several state-of-the-art GNN models used for force field prediction:

Table 1: Comparison of Graph Neural Network Models for Force Field Prediction

| Model Name | Symmetry Handling | Number of Parameters | Computational Efficiency (MD time, ns/day) | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SchNet [28] | E(3)-invariant | ~0.49 Million | 22.5 | Uses continuous-filter convolutional layers; a well-established benchmark. [29] |

| DimeNet++ [28] | E(3)-invariant | ~1.49 Million | 6.0 | Incorporates directional message passing for improved angular information. |

| Equiformer [28] | SE(3)/E(3)-equivariant | ~7.84 Million | 3.0 | Uses attention mechanisms designed to be equivariant to 3D rotations and translations. |

| NequIP [15] | E(3)-equivariant | Not Specified | Not Specified | Employs irreducible representations for high data efficiency and accuracy. |

| Grappa [30] | Molecular Graph-based | Not Specified | Highly Efficient | Predicts parameters for a molecular mechanics force field, not energies/forces directly. |

| CGCNN [28] | E(3)-invariant | ~0.25 Million | 45.0 | Originally designed for crystalline materials; lower accuracy in force prediction. [28] |

| ForceNet [28] | Translation-invariant | ~11.37 Million | 25.7 | Focuses on force prediction directly, using an invariant architecture. |

Performance and Transferability Metrics

Beyond architectural differences, the practical utility of a GNN force field is measured by its accuracy and stability in simulations. Standard metrics include the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of energy and force predictions on test datasets. However, as highlighted by recent research, low MAE does not guarantee reliable molecular dynamics simulations or transferability [15].

A study benchmarking GNN models on lithium-ion conductors demonstrated that while many models achieved high R² scores (>0.98) for force prediction on held-out test data from the same material (Li({10})GeP(2)S({12})), their performance varied significantly when transferred to different materials (Li(3)PS(4) and Li(4)GeS(_4)) [28]. Models like CGCNN and SchNet showed "clearly incorrect force predictions" in this transferability test [28]. Furthermore, radial distribution function (RDF) analysis from MD simulations revealed that some models with accurate force predictions still produced unstable or physically implausible simulation trajectories [28].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Metrics for GNN Force Fields

| Validation Metric | What It Measures | Insight Provided | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/Force MAE | Deviation from reference (DFT) energies/forces. | Basic predictive accuracy on similar data. | Necessary but insufficient for assessing simulation reliability [28] [15]. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | Probability of finding atom pairs at a distance. | Structural integrity of the simulated material. | Can reveal catastrophic failures (e.g., lattice mismatch) not apparent from MAE alone [28]. |

| Phonon Density of States | Vibrational frequency distribution. | Accuracy in capturing solid-phase dynamics. | Models trained only on liquid data fail this test; requires solid-phase training data [15]. |

| Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) | Average particle mobility over time. | Liquid-phase dynamics and diffusivity. | A standard test, but should be complemented with other metrics [15]. |

| X-ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy (XPCS) | Density fluctuations at various length scales. | Dynamic behavior in the liquid phase. | Part of a comprehensive benchmarking suite beyond RDF and MSD [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the development of transferable and reliable GNN force fields, a rigorous and multi-faceted validation protocol is essential. Relying solely on energy/force errors or a single property like RDF is inadequate [15]. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive experimental validation strategy.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

1. Training Data Curation: The foundation of a transferable model is a diverse training dataset. For material properties, this means including configurations from both solid and liquid phases and across a range of temperatures [15]. For instance, a model trained only on liquid argon configurations failed to reproduce the correct phonon density of states in the solid phase, a deficiency only remedied by including solid-phase data [15]. For universal force fields like EMFF-2025 (for energetic materials) or Grappa (for biomolecules), the training set must span a wide chemical space of the target molecules [31] [30].

2. Free Energy Profile Calculation: Assessing a model's ability to describe reaction pathways or conformational changes is crucial. This can be done efficiently by re-weighting trajectories from a reference simulation (e.g., using umbrella sampling) to estimate the free energy profile with the new GNN force field, as demonstrated with SchNet for protein folding [29]. This provides a more sensitive metric of performance than energy error alone.

3. Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Analysis: RDFs, calculated from an MD trajectory, describe the probability of finding an atom at a distance from a reference atom. It is a fundamental test of structural integrity. Studies categorize RDFs as stable (MAE < 0.02) or unstable, with failures manifesting as lattice mismatch or complete structural collapse [28].

4. Phonon Density of States and XPCS: These advanced tests provide a more comprehensive validation. Phonon DOS validates the model's description of atomic vibrations in solids [15]. Computational XPCS probes density fluctuations at various length scales in liquids, offering insights beyond simple diffusivity [15]. A model must pass these tests to be considered truly transferable across phases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Developing and applying GNN force fields requires a suite of software tools and datasets. The table below lists key "research reagents" essential for work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for GNN Force Field Research

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to GNN Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|

| GraNNField [28] | Software Package | Implements & compares GNN models for MD. | Provides a unified framework for training and benchmarking models like SchNet, DimeNet++, and Equiformer. |

| DP-GEN [31] | Software Framework | Automated active learning for generating training data. | Used in developing EMFF-2025 to efficiently explore configurational space and build robust datasets. |

| OpenMM / GROMACS [30] | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance molecular dynamics. | Standard engines for running simulations; Grappa is designed to integrate directly with them. |

| LAMMPS [28] | MD Simulation Engine | Large-scale atomic/molecular simulator. | Often used as a platform to integrate and test new machine-learning force fields. |

| Materials Project [28] | Database | Repository of computed material properties. | Source of initial structures and data for training and benchmarking, especially for inorganic materials. |

| Espaloma Dataset [30] | Dataset | QM data for small molecules, peptides, and RNA. | A standard benchmark for evaluating the accuracy of force fields on diverse chemical spaces. |

| ANI-nr / CHNO Datasets [31] | Dataset | QM data for organic molecules (C, H, N, O). | Critical for training general-purpose force fields for organic chemistry and energetic materials. |

| Pan KRas-IN-1 | Pan KRas-IN-1, MF:C33H36F3N5O3, MW:607.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ER degrader 7 | ER degrader 7, MF:C33H31F4N3O5SSe, MW:736.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of GNN-based force fields is rapidly maturing, with models like SchNet, DimeNet++, and Equiformer demonstrating high accuracy on par with DFT at a fraction of the cost. However, this comparison guide underscores that raw predictive accuracy on a test set is an incomplete measure of a model's value. Transferability is the critical frontier. The development of comprehensive benchmarking suites that include RDF, phonon DOS, and XPCS signals is essential to build trust in these models [15]. Furthermore, innovative approaches like Grappa, which leverages GNNs to assign parameters to a physically interpretable molecular mechanics force field, offer a promising path toward achieving excellent transferability and stability while retaining the high efficiency of traditional MD [30]. As these tools evolve, supported by robust experimental protocols and diverse datasets, they are poised to unlock new possibilities in the molecular simulation of drugs, materials, and biological systems.

The accurate description of molecular interactions through force fields is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery. The fundamental challenge lies in creating models that are both computationally efficient and highly accurate across expansive chemical spaces. With synthetically accessible chemical space for drug candidates rapidly expanding, traditional "look-up table" approaches for force field parameterization are increasingly inadequate [32]. This limitation is particularly acute for complex molecular systems such as those found in mycobacterial membranes, which contain unique lipids with remarkable structural complexity [33]. In response to these challenges, modular parameterization strategies—often termed "divide-and-conquer" approaches—have emerged as powerful methodologies that systematically decompose complex molecules into manageable fragments for parameterization before reintegrating them into a coherent whole. These strategies are transforming force field development by enhancing transferability, improving accuracy, and enabling the modeling of biologically and pharmacologically relevant systems that were previously intractable with conventional methods. This review objectively compares the performance, methodologies, and applications of contemporary modular parameterization strategies, evaluating their effectiveness within the broader context of transferable force field research.

Comparative Analysis of Modular Parameterization Approaches

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of four prominent modular parameterization strategies identified in current literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Modular Parameterization Strategies

| Strategy Name | Core Methodology | Representative Force Field | Key Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragment-Based QM Parameterization [33] | Divides large molecules into chemically logical segments for individual QM calculation of charges/geometries. | BLipidFF (Bacteria Lipid Force Fields) | High accuracy for complex lipids; Captures unique membrane properties; Excellent experimental validation. | Computationally expensive for large systems; Requires careful fragment capping. |

| Data-Driven Graph Neural Network [32] [13] | Uses GNNs trained on vast QM datasets of molecular fragments to predict parameters end-to-end. | ByteFF | Expansive chemical space coverage; High throughput; Automatically preserves chemical symmetry. | Requires massive, high-quality training datasets; "Black box" nature may reduce interpretability. |

| Bayesian Inference of Conformational Populations (BICePs) [34] | Uses Bayesian inference to reconcile simulation ensembles with sparse/noisy experimental data. | N/A (Reweighting algorithm) | Robust to experimental noise/outliers; Quantifies uncertainty in parameters. | Complex statistical framework; Computationally intensive sampling process. |

| Standardized Data Scheme [9] | Formalizes transferable force fields into a machine-readable, interoperable data scheme (TUK-FFDat). | N/A (Framework for multiple FFs) | Promotes reproducibility and interoperability; Enables automated workflows. | Does not specify parameterization method itself; An infrastructure tool. |

Performance Benchmarks and Experimental Validation

Quantitative benchmarks are crucial for objectively assessing the performance of parameterization strategies. The following table compiles key experimental data from validation studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of Modular Parameterization Strategies

| Validation Metric | Fragment-Based QM (BLipidFF) [33] | Data-Driven GNN (ByteFF) [32] [13] | Bayesian BICePs [34] | | :--- | :--- | :--- | : :--- | | Accuracy vs. QM Data | N/A (Parameters directly derived from QM) | Excels in predicting relaxed geometries, torsional profiles, and conformational energies/forces. | N/A (Method focuses on reconciling with experimental data) | | Accuracy vs. Experimental Data | Excellently captures α-mycolic acid bilayer rigidity and diffusion rates; Matches FRAP experimental data. | State-of-the-art performance on various benchmark datasets for drug-like molecules. | Effectively refines ensembles against sparse/noisy ensemble-averaged measurements. | | Chemical Space Coverage | Validated for key mycobacterial lipids (PDIM, α-MA, TDM, SL-1). | Trained on 2.4M optimized fragments and 3.2M torsion profiles; exceptional for drug-like molecules. | Tested on a 12-mer HP lattice model and a von Mises-distributed polymer model. | | Computational Efficiency | QM calculations are expensive but performed once for modular library. | GNN prediction is fast after initial training; training is computationally intensive. | MCMC sampling is computationally intensive; variational optimization improves efficiency. | | Resilience to Error | N/A (Assumes high-quality QM data) | N/A (Depends on training data quality) | Demonstrates resilience to unknown random and systematic errors in training data. |

Key Experimental Protocols

The validation of these strategies relies on rigorous experimental and simulation protocols:

BLipidFF Validation [33]: Force field parameters for mycobacterial lipids were developed using a modular QM strategy. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were then performed using these parameters. Key validation metrics included measuring the lateral diffusion coefficient of α-mycolic acid bilayers and comparing the results directly with Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) experiments. Furthermore, the force field's ability to capture the high tail rigidity of outer membrane lipids was confirmed against fluorescence spectroscopy measurements.

ByteFF Validation [32] [13]: The performance of the ByteFF force field was assessed on multiple benchmark datasets. Protocols involved comparing ByteFF's predictions of molecular geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies and forces against high-level QM reference data. This provides a comprehensive evaluation of its accuracy in describing the intramolecular potential energy surface.

BICePs Validation [34]: The algorithm's effectiveness was demonstrated by refining force field parameters for a 12-mer HP lattice model. The optimization used ensemble-averaged distance measurements as restraints in the Bayesian inference framework. Performance was quantitatively assessed through repeated optimizations and under varying levels of introduced experimental error.

Workflow Visualization: The Divide-and-Conquer Paradigm

The modular parameterization process can be visualized as a structured workflow, illustrating the logical flow from molecule to validated force field. The diagram below outlines the core steps common to these strategies, highlighting the "divide-and-conquer" philosophy.

Successful implementation of modular parameterization strategies requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Modular Parameterization

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Parameterization |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian09 [33] | Software | Performs quantum mechanical (QM) geometry optimization and energy calculations for molecular fragments. |

| Multiwfn [33] | Software | Conducts electronic structure analysis, including Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) charge fitting. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [32] [13] | Algorithm/Software | Maps molecular graphs of fragments to force field parameters in an end-to-end, data-driven manner. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer [13] | Software | Optimizes molecular geometries using QM calculations, crucial for generating training data. |

| Bayesian Inference (BICePs) [34] | Algorithm | Provides a statistical framework for robust parameter refinement against noisy experimental data. |

| TUK-FFDat [9] | Data Scheme | A standardized, machine-readable format for storing and sharing transferable force field parameters, ensuring interoperability. |

| ChEMBL / ZINC Databases [13] | Data | Provide vast, diverse molecular structures used for generating fragment datasets to train machine-learning models like ByteFF. |

Modular "divide-and-conquer" strategies represent a paradigm shift in force field parameterization, directly addressing the critical need for transferability across expansive chemical spaces. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that while fragment-based QM approaches like BLipidFF provide high accuracy for specialized, complex molecules, data-driven GNN approaches like ByteFF offer unparalleled coverage and throughput for drug-like chemical space. Simultaneously, Bayesian inference methods like BICePs provide a robust statistical framework for dealing with experimental uncertainty.

The future of modular parameterization likely lies in the hybridization of these approaches. For instance, the interpretability and physical grounding of QM-based fragment methods could be combined with the scalability and automation of GNNs. Furthermore, the adoption of standardized data schemes like TUK-FFDat will be crucial for ensuring reproducibility, facilitating collaboration, and enabling the seamless integration of these advanced parameterization strategies into automated, high-throughput computational workflows for drug discovery and materials science. As these methodologies continue to mature and converge, they will significantly enhance the reliability and scope of molecular simulations, providing deeper insights into complex biological and chemical systems.

Computational modeling of large molecular systems faces significant barriers due to the exponential scaling of resource requirements with system size. This review evaluates polymorphic structure replacement as a methodology for reducing computational costs in force field parameterization for metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and pharmaceutical compounds. By leveraging chemically identical but structurally simpler polymorphs, researchers can derive accurate interaction parameters while avoiding prohibitive quantum chemical calculations on massive systems. Experimental data from case studies on MOF-177 and pharmaceutical polymorph prediction demonstrate that force fields parameterized on smaller polymorphs show excellent transferability to original complex structures, with computational cost reductions of several orders of magnitude. This approach provides a practical pathway for simulating large porous materials and understanding complex polymorphic landscapes where direct quantum mechanical calculations would be computationally intractable.

Computational costs for quantum chemical simulations scale dramatically with system size, creating significant challenges for modeling large molecular systems. Density functional theory (DFT) computation costs grow with the third power of system size, making direct calculations prohibitively expensive for metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with large unit cells or flexible pharmaceutical molecules with complex conformational landscapes [1]. Similar scalability issues affect advanced methods like diffusion Monte Carlo, where computational cost ultimately shows exponential scaling for systems containing several hundred atoms [35].