From Alchemy to AI: The Revolutionary Journey of Analytical Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of analytical chemistry's evolution, tracing its path from ancient qualitative observations to today's sophisticated instrumental techniques.

From Alchemy to AI: The Revolutionary Journey of Analytical Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of analytical chemistry's evolution, tracing its path from ancient qualitative observations to today's sophisticated instrumental techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational history, modern methodological applications, practical troubleshooting strategies, and current validation paradigms. The content highlights how breakthroughs in mass spectrometry, AI-driven data analysis, and green chemistry principles are directly impacting biomedical research, pharmaceutical quality control, and the development of innovative clinical diagnostics.

The Evolution of Analysis: From Ancient Arts to Classical Science

This whitepaper explores the foundational role of sensory evaluation—specifically taste and smell—in the early development of analytical chemistry. Long before the advent of modern instrumentation, ancient societies relied on these sophisticated sensory tools for material characterization, quality control, and technological innovation. By examining historical practices through the lens of contemporary analytical chemistry, we trace how sensory perception served as the original analytical instrument, establishing principles that would later formalize into a scientific discipline. This analysis reframes ancient sensory knowledge as a crucial evolutionary stage in the history of analytical science, with direct relevance to modern material and drug development research.

The human senses of taste and smell represent the most ancient forms of chemical analysis, serving as primary tools for characterizing materials, assessing quality, and ensuring safety for millennia before the development of instrumental methods. These sensory evaluation techniques formed the bedrock of early technological advances in domains including metallurgy, perfumery, food production, and medicine [1]. The fundamental principles established through these sensory-based analyses—detection, identification, differentiation, and quantification of chemical properties—would later become the core objectives of analytical chemistry as a formal scientific discipline [1].

Within the broader thesis of historical developments in analytical chemistry research, this paper positions sensory perception as the foundational methodology from which more sophisticated instrumental techniques eventually emerged. By examining specific historical case studies and reconstructing ancient analytical approaches, we demonstrate how early societies practiced essential analytical procedures through biological sensing, establishing patterns of empirical observation that would shape the future of chemical analysis.

Historical Context: Ancient Analytical Practices

Early Material Characterization

Ancient civilizations developed sophisticated material production techniques that relied heavily on sensory evaluation for quality control and process optimization. Evidence suggests that chemical processes were employed in perfumery, cheese-making, winery, metal polishing, and the production of dyes and ceramics as early as the time of Homer [1]. The renowned Attic pottery of ancient Greece, for instance, featured distinctive black gloss coatings whose production required precise control of firing conditions and material composition—parameters that artisans would have monitored through visual appearance, texture, and other sensory cues [1].

Perhaps the most technologically advanced ancient analytical application was the development of "Greek fire" (υγÏον πυÏ), an incendiary weapon used by the Byzantine Empire whose precise composition remains unknown today [1]. The development and deployment of this substance would have required rigorous sensory evaluation of raw materials and final product properties, representing an early form of quality assurance in military technology.

The Sensory Basis of Alchemy

Alchemy, as practiced in both the Hellenistic world and medieval Europe, relied extensively on sensory observation for material characterization. Alchemists employed taste, smell, and visual appearance to identify substances and monitor chemical transformations during their experiments [1]. While often shrouded in mystery and symbolism, these practices established crucial precedents for experimental observation and material manipulation that would later evolve into more systematic chemical analysis. The transition from alchemy to chemistry represented not the abandonment of sensory evaluation, but rather its integration with increasingly rigorous methodological frameworks.

The Sensory Toolkit of Early Societies

Biological Foundations of Sensory Analysis

The human sensory system provided ancient practitioners with a sophisticated analytical instrument capable of detecting and discriminating between countless chemical stimuli. The biological basis for this sensory analysis begins with specialized receptor cells that respond to specific classes of stimulus energies [2].

Olfactory transduction initiates when volatile molecules bind to G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the olfactory epithelium [3]. This binding triggers a cascade involving G-proteins (comprising α, β, and γ subunits), activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), generation of cyclic adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) as a second messenger, and ultimately the opening of ion channels that allow sodium and calcium ions to flow into the cell, propagating the neural signal [3]. This complex transduction mechanism enables the detection of odorants at extremely low concentrations, often in the order of parts per billion [3].

Gustatory transduction employs complementary mechanisms for detecting non-volatile compounds. Salty taste perception occurs directly through the influx of sodium ions (Na+) into gustatory cells, while sour taste detects hydrogen ion (H+) concentration [4]. Sweet, bitter, and umami tastes, however, involve more complex signal transduction through G protein-coupled receptors similar to those in olfaction [4]. The recent identification of potential fat-taste receptors further expands the analytical capabilities of the gustatory system [4].

Figure 1: Molecular transduction pathways for smell and taste.

Evolutionary Adaptations in Sensory Perception

Research on olfactory receptor genes provides compelling evidence for the evolutionary significance of chemical sensing in human development. Studies of the OR7D4 gene, which codes for a receptor sensitive to androstenone (a compound produced by pigs), reveal population-specific variations that correlate with differential sensitivity to this odorant [5]. Indigenous populations in Africa, where humans originated, generally maintain the ability to detect androstenone, while many populations from northern hemispheres show reduced sensitivity [5].

Statistical analysis of OR7D4 gene frequencies suggests these variations may result from natural selection, potentially linked to the domestication of pigs in Asia, where reduced sensitivity to androstenone would have made pork from uncastrated boars more palatable [5]. This genetic evidence demonstrates how sensory capabilities evolved in response to environmental and cultural factors, refining the biological analytical toolkit available to early societies.

Reconstructed Analytical Methodologies

Ancient Sensory Evaluation Protocols

Based on historical evidence and archaeological findings, we can reconstruct several key analytical methodologies that would have been employed in ancient societies for material characterization. These protocols relied exclusively on human sensory perception as the detection mechanism.

Table 1: Ancient Sensory Evaluation Techniques for Material Analysis

| Analytical Objective | Sensory Modality | Methodology | Historical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purity Assessment | Visual, Olfactory | Comparative analysis against reference materials | Evaluation of metals, spices, incense [1] |

| Quality Verification | Gustatory, Olfactory | Direct sampling with standardized tasting procedures | Food safety testing, wine quality assessment [1] |

| Process Monitoring | Visual, Olfactory | Temporal evaluation of sensory changes during production | Ceramic firing, fermentation, metallurgy [1] |

| Origin Identification | Olfactory, Gustatory | Geographic signature recognition through complex scent profiling | Provenance determination of resins, wines, oils [6] |

| Adulteration Detection | Visual, Gustatory, Olfactory | Deviation from expected sensory profile | Spice quality control, precious material verification [1] |

| 3-(3-Nitrophenoxy)aniline | 3-(3-Nitrophenoxy)aniline | 3-(3-Nitrophenoxy)aniline is a high-purity chemical for research use only (RUO). Explore its value as a building block in organic synthesis. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Aminopyridine-3,4-diol | 2-Aminopyridine-3,4-diol CAS 856954-76-2 - RUO | Get 2-Aminopyridine-3,4-diol (CAS 856954-76-2), a high-purity building block for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Modern Reconstruction of Ancient Analyses

Contemporary analytical techniques now allow us to reconstruct and validate ancient sensory evaluations. Gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O) represents a particularly powerful hybrid approach that combines instrumental separation with human sensory detection, effectively bridging ancient and modern analytical paradigms [7].

Protocol 1: Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry for Odor-Active Compound Analysis

Principle: This method integrates the separation capabilities of gas chromatography with the detection specificity of human olfaction to identify odor-active compounds in complex mixtures [7].

Apparatus:

- Gas chromatograph equipped with an odour port (ODP)

- Deactivated silica transfer line (heated to prevent condensation)

- Humidified carrier gas system (50-75% RH to prevent nasal dehydration)

- Optional parallel detection with FID or MS for compound identification [7]

Procedure:

- Prepare sample extracts using appropriate solvent extraction or headspace sampling techniques

- Inject sample into GC system with specified temperature program

- Splitting eluate between instrumental detector and odour port

- Trained assessors sniff the effluent from the odour port

- Record retention time, odour quality, intensity, and duration for each perceived odorant

- Correlate sensory data with chromatographic peaks for compound identification [7]

Data Analysis Methods:

- Detection Frequency: Count assessors detecting odor at each retention time (Nasal Impact Frequency)

- Dilution to Threshold: Prepare dilution series to determine Flavor Dilution factors

- Direct Intensity: Assessors rate perceived intensity using standardized scales [7]

This modern protocol effectively formalizes and quantifies the sensory evaluation practices that ancient practitioners would have performed intuitively when assessing aromatic materials like resins, spices, or fermented products.

The Research Toolkit: Ancient and Modern Parallels

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The transition from ancient sensory evaluation to modern analytical chemistry represents an evolution rather than a replacement of fundamental approaches. The following table compares ancient sensory tools with their modern instrumental counterparts, demonstrating the conceptual continuity in analytical methodology.

Table 2: Evolution of Analytical Tools from Ancient to Modern Practice

| Ancient Sensory Tool | Modern Analytical Equivalent | Primary Function | Technical Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Olfactory System | Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry (GC-O) [7] | Odorant detection and identification | Supplementation rather than replacement of biological detection |

| Taste Perception | Electronic Tongue / Spectroscopic Analysis | Compound identification and quantification | Objective measurement of previously subjective assessments |

| Visual Inspection | Microscopy / Spectroscopy [8] | Material characterization and purity assessment | Enhanced resolution and quantitative capabilities |

| Reference Materials | Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and quality assurance | Standardization and traceability |

| Artisan Knowledge | Chemometric Analysis [8] | Pattern recognition in complex data | Formalized statistical approaches to empirical observation |

| 2-Formyl-6-iodobenzoic acid | 2-Formyl-6-iodobenzoic acid, MF:C8H5IO3, MW:276.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-(Aminomethoxy)aceticacid | 2-(Aminomethoxy)aceticacid, MF:C3H7NO3, MW:105.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Workflow for Ancient Practice Reconstruction

Modern research into ancient analytical practices requires an interdisciplinary approach that combines historical analysis with experimental archaeology and sophisticated instrumental techniques. The following workflow outlines a systematic methodology for reconstructing and validating ancient sensory-based analyses.

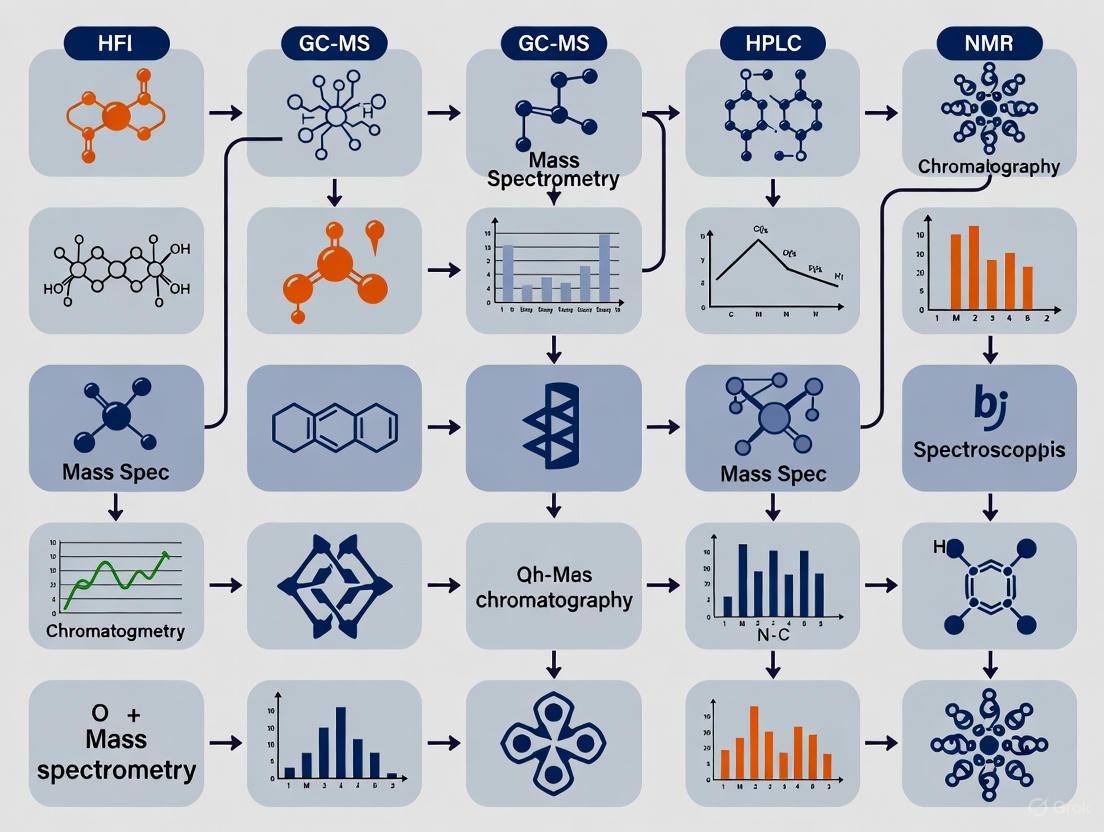

Figure 2: Interdisciplinary workflow for reconstructing ancient analytical methods.

Implications for Modern Research and Development

Sensory-Informed Drug Development

The historical reliance on sensory perception for material characterization finds surprising relevance in modern pharmaceutical development. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of olfactory and gustatory reception provides insights that extend beyond sensory evaluation to broader chemical recognition processes.

Olfactory receptors belong to the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) class [3], which represents a crucial drug target category in modern pharmacology. Approximately 34% of FDA-approved drugs target GPCRs, making this protein family one of the most therapeutically significant. The study of olfactory GPCRs and their ligand interactions thus provides valuable models for understanding receptor-ligand interactions more broadly, with direct implications for drug discovery and development.

Cognitive and Behavioral Dimensions

Modern neuroscience has revealed why sensory evaluation provided such a powerful analytical tool for ancient societies. Olfactory signals bypass the thalamic relay station used by other senses and project directly to the limbic system, the brain regions governing emotion, memory, and behavior [9]. This direct neural pathway explains the immediate emotional responses and strong memory associations triggered by scents, enhancing their reliability as analytical tools when combined with trained evaluation.

Contemporary research demonstrates that fragrance compositions create measurable, reproducible changes in brain activity observable through electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [9]. These findings validate the sophisticated understanding that ancient practitioners developed empirically regarding the effects of specific aromatic compounds on human physiology and psychology.

The history of analytical chemistry must be reconceptualized to acknowledge observation, taste, and smell as the original analytical methodologies that established fundamental principles of material characterization. Ancient societies employed sophisticated sensory-based analyses that represented the state of the art in chemical evaluation for millennia, developing empirical frameworks that would later formalize into scientific discipline. Rather than being rendered obsolete by instrumental advances, these sensory approaches have evolved into hybrid techniques like GC-O that integrate human perception with instrumental separation, demonstrating the enduring value of biological sensing in chemical analysis.

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these ancient origins provides valuable perspective on the fundamental nature of chemical recognition and receptor-ligand interactions. The continued study of these primal analytical tools not only enforces our historical understanding but also informs cutting-edge developments in materials science, pharmaceutical research, and chemical sensing technologies. As analytical chemistry continues to evolve with advances in automation, miniaturization, and data analysis [8], the human senses that started this scientific journey remain relevant, reminding us that the most sophisticated instruments often emulate biological systems that ancient societies mastered through empirical observation and sensory acuity.

The evolution from alchemy to modern chemistry represents a fundamental paradigm shift in humanity's approach to understanding matter and its transformations. This transition was not merely a change in terminology but a comprehensive restructuring of philosophical frameworks, methodological practices, and analytical techniques. Within the broader context of historical developments in analytical chemistry research, the emergence of systematic qualitative analysis marks a critical turning point that enabled the reproducible identification of substances based on their observable properties [10]. This transformation from the mystical traditions of alchemy to the empirical discipline of chemistry established the foundational principles upon which contemporary drug development and pharmaceutical research are built. The journey from the alchemist's laboratory to the modern research facility demonstrates how methodological rigor gradually supplanted esoteric beliefs while preserving and enhancing the practical experimental techniques developed over centuries of alchemical practice [11]. For today's researchers and scientists, understanding this historical context provides valuable insights into the epistemological foundations of analytical chemistry and its application to complex challenges in drug development.

Historical Background: From Empirical Craft to Systematic Science

The transformation from alchemy to chemistry occurred through centuries of accumulated practical knowledge and theoretical refinement. Ancient civilizations, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China, developed sophisticated chemical practices for metallurgy, brewing, pigment production, and medicine, establishing a rich repository of empirical knowledge without the underlying theoretical framework that would later characterize modern chemistry [10]. These practices were largely qualitative, focusing on observable characteristics and practical outcomes rather than quantitative measurements or systematic analysis.

Alchemy served as a crucial transitional phase between these ancient practical arts and modern chemical science. While often characterized by mystical goals such as the transmutation of base metals into gold or the search for the elixir of life, alchemists made substantial contributions to laboratory methodology through their development of essential apparatus and techniques [12]. They introduced and refined fundamental operations including distillation, sublimation, calcination, and filtration, creating the basic toolkit of the chemical laboratory [10]. Perhaps most significantly, alchemists discovered and characterized numerous elements and compounds, including mineral acids (sulfuric, nitric, and hydrochloric) and elements such as phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony, while maintaining detailed records of their properties and reactions [10] [11].

Table 1: Key Civilizational Contributions to Early Chemical Practices

| Civilization | Area of Expertise | Chemical Practices | Modern Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Egypt | Metallurgy, Pigment Production, Embalming | Extraction of metals, synthesis of pigments, use of preservatives | Understanding of redox reactions, material science |

| Mesopotamia | Brewing, Perfume Making, Glass Production | Fermentation processes, distillation of perfumes, creation of silicate-based materials | Biotechnological applications, perfume chemistry |

| Ancient China | Alchemy, Medicine, Gunpowder | Elixir of life attempts, discovery of potassium nitrate | Pharmaceutical chemistry, reaction kinetics |

| Ancient Greece | Philosophy, Early Atomic Theory | Speculation about nature of matter (earth, air, fire, water) | Conceptual foundation for atomic theory |

The theoretical limitations of alchemy eventually necessitated a more systematic approach. Alchemical practices were predominantly qualitative, relying on descriptive observations rather than precise measurement, and their theoretical frameworks often incorporated spiritual and metaphysical elements that resisted empirical verification [12]. The lack of standardized nomenclature and reproducible methodologies further impeded the cumulative progress of chemical knowledge, as findings were often obscured by symbolic language and secretive traditions.

The Transition to Systematic Qualitative Analysis

Conceptual and Methodological Shifts

The transformation from alchemy to chemistry required fundamental changes in both philosophical approach and practical methodology. The 17th and 18th centuries witnessed a decisive shift from qualitative descriptions to quantitative analysis, enabled by the development of more precise instrumentation, particularly accurate balances [10]. This emphasis on measurement and reproducibility marked a critical departure from alchemical traditions and established the foundation for systematic qualitative analysis.

Robert Boyle (1627-1691) challenged the prevailing Aristotelian concept of four elements and advocated for a corpuscular theory of matter, defining elements as substances that cannot be broken down into simpler components by chemical means [10]. His work with gases, culminating in Boyle's Law (Pâ‚Vâ‚ = Pâ‚‚Vâ‚‚ at constant temperature), demonstrated the power of quantitative relationships in understanding chemical behavior and encouraged the application of mathematical principles to chemical phenomena [10].

Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794) revolutionized chemistry through his meticulous attention to quantitative measurements, particularly his demonstration of the role of oxygen in combustion and his refutation of the phlogiston theory [10]. His formulation of the law of conservation of mass established that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions, providing a fundamental principle for quantitative analysis [10]. Lavoisier's systematic approach extended to chemical nomenclature, where he introduced a standardized naming system for elements and compounds that facilitated clearer communication and more accurate documentation of experimental results [10].

John Dalton (1766-1844) further advanced the systematic framework of chemistry with his atomic theory, which postulated that matter is composed of indivisible particles called atoms, that atoms of the same element are identical, and that chemical reactions involve the rearrangement of atoms [10]. This theoretical foundation provided a mechanistic explanation for the laws of definite and multiple proportions, enabling chemists to understand and predict the composition of compounds [10].

Table 2: Fundamental Laws Establishing Systematic Chemistry

| Law | Description | Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Law of Conservation of Mass | Mass is neither created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction. | Enabled quantitative analysis of reactions, leading to accurate stoichiometric calculations. | Burning wood in a closed container: the mass of the wood and oxygen consumed equals the mass of the ash and gases produced. |

| Law of Definite Proportions | A chemical compound always contains exactly the same proportion of elements by mass. | Allowed chemists to identify and characterize compounds based on their elemental composition. | Water (Hâ‚‚O) always contains 11.19% hydrogen and 88.81% oxygen by mass. |

| Law of Multiple Proportions | If two elements form more than one compound, the ratios of the masses of the second element which combine with a fixed mass of the first element will be ratios of small whole numbers. | Further validated atomic theory and provided a basis for understanding the composition of different compounds. | Carbon and oxygen form two compounds: carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚). For a fixed mass of carbon, the ratio of oxygen masses is 1:2. |

Key Figures and Their Contributions

Several pivotal figures bridged the gap between alchemical traditions and modern chemical science, each contributing unique insights and methodologies that advanced the systematic approach to qualitative analysis:

Jabir ibn Hayyan (c. 721–c. 815): Often called the "father of chemistry," this Persian alchemist introduced systematic experimentation and developed laboratory techniques such as distillation, crystallization, and calcination that would become standard practice in chemical laboratories [11]. His emphasis on experimental methodology, while still within an alchemical framework, established important precedents for empirical investigation.

Paracelsus (1493-1541): This Renaissance physician and alchemist shifted the focus of alchemical inquiry toward practical medicine, advocating the use of chemical remedies for treating disease [11]. He introduced laudanum (an opium tincture) and emphasized the medicinal application of minerals, establishing foundations for pharmacology and toxicology. His work demonstrated how chemical principles could be applied to practical challenges in healthcare.

Robert Boyle (1627-1691): As previously mentioned, Boyle's seminal work "The Sceptical Chymist" challenged alchemical dogma and established a corpuscular approach to matter [10]. He introduced rigorous experimental methods and emphasized the importance of publishing detailed methodologies to allow for replication and verification of results.

Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794): Lavoisier's meticulous approach to experimental quantification and his development of systematic nomenclature effectively established the modern science of chemistry [10]. His emphasis on precise measurement and mass balance in chemical reactions provided the methodological foundation for all subsequent analytical chemistry.

Development of Systematic Qualitative Analysis Techniques

Evolution of Laboratory Apparatus and Methods

The development of systematic qualitative analysis relied heavily on the refinement of laboratory apparatus and standardized procedures. Alchemists had created the basic toolkit of the chemical laboratory, including alembics for distillation, retorts for heating, and crucibles for high-temperature reactions [10]. These tools were progressively refined and specialized for specific analytical purposes as chemistry emerged as a distinct discipline.

The introduction of specialized glassware enabled more sophisticated separation and identification techniques. Improved condensers, receivers, and fractionating columns enhanced the precision of distillation processes, allowing chemists to separate and identify components of complex mixtures based on their boiling points [10]. The development of specific reagents for detecting particular elements or functional groups represented another critical advancement, creating systematic pathways for identifying unknown substances through their characteristic reactions [10].

The fire assay technique, refined by alchemists and early metallurgists, demonstrates this evolution from art to systematic analysis. Originally developed for determining the precious metal content in ores and alloys, fire assay employed precise heating and fusion techniques to separate gold and silver from base metals [13]. Research on historical metallurgical practices has shown that these methods achieved approximately 95% accuracy in precious metal recovery, demonstrating the sophistication achievable even with early analytical techniques [13]. The methodology involved carefully controlled heating in specially designed crucibles with specific fluxes to separate metals based on their chemical properties, establishing principles that would later be applied to qualitative analysis of other substances.

Systematic Qualitative Analysis Schemes

The consolidation of qualitative analysis into systematic schemes for identifying elements and compounds represented a major advancement in chemical methodology. These schemes provided structured approaches for analyzing unknown substances through a sequence of carefully designed tests and observations. Key developments included:

Flame tests: The recognition that different elements impart characteristic colors to flames provided a simple but powerful tool for preliminary identification of metals such as sodium (yellow), potassium (violet), and copper (green).

Precipitation reactions: The systematic use of specific reagents to produce insoluble compounds became a cornerstone of qualitative analysis. For example, the addition of silver nitrate to solutions containing chloride, bromide, or iodide ions produced characteristic precipitates of different colors and solubilities.

Solution chemistry: The development of systematic approaches for analyzing ions in solution, including the separation of cations into groups based on their solubility properties, enabled the comprehensive identification of components in complex mixtures.

These systematic approaches transformed qualitative analysis from a collection of isolated tests into a coherent analytical framework that could be systematically taught and reproducibly applied. The publication of laboratory manuals detailing these schemes, complete with flowcharts and systematic procedures, made qualitative analysis a fundamental component of chemical education and practice.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The transition from alchemy to systematic chemistry required not only conceptual changes but also the development of specialized materials and reagents that enabled reproducible qualitative analysis. The following table details key research reagent solutions and essential materials that formed the foundation of systematic qualitative analysis, many with roots in alchemical practices but refined for precise analytical applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Qualitative Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Qualitative Analysis | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral Acids (H₂SO₄, HCl, HNO₃) | Solubilization of samples, pH adjustment, participation in specific precipitation reactions | Discovered by alchemists; essential for dissolving metals and minerals for analysis [10] |

| Litmus and Other Plant Extracts | pH indicators for determining acidic or basic character of solutions | Early examples of using natural products as analytical reagents; provided visual evidence of chemical properties |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Detection of halides through formation of characteristic precipitates (AgCl-white, AgBr-pale yellow, AgI-yellow) | Exemplified the development of specific reagents for systematic identification of ion groups |

| Barium Chloride (BaClâ‚‚) | Detection of sulfate ions through formation of insoluble barium sulfate | Demonstrated the principle of using precipitation reactions for identification and separation |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) | Group precipitation of metal sulfides in systematic qualitative analysis schemes | Key reagent in the development of systematic cation analysis; allowed separation based on solubility differences |

| Alembic and Retort Apparatus | Distillation and purification of solvents and reaction products | Developed by alchemists like Jabir ibn Hayyan; essential for purification and separation [11] |

| Crucibles and Cupels | High-temperature reactions and metallurgical assays | Used in fire assay techniques for precious metal analysis; enabled quantitative assessment of metal content [13] |

| (R)-7-Methylchroman-4-amine | (R)-7-Methylchroman-4-amine | |

| Lanost-9(11)-ene-3,23-dione | Lanost-9(11)-ene-3,23-dione, MF:C30H48O2, MW:440.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The development and standardization of these reagents and materials enabled the reproducible identification of substances based on their chemical properties, establishing qualitative analysis as a systematic discipline rather than an artisanal practice. The progression from universal reagents to highly specific testing agents mirrored the increasing sophistication of chemical knowledge and the growing understanding of structure-property relationships.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Systematic Qualitative Analysis Protocol for Inorganic Salts

The following experimental protocol exemplifies the systematic approach to qualitative analysis that developed during the transition from alchemy to modern chemistry. This methodology for analyzing an unknown inorganic salt demonstrates the logical, stepwise process that characterized the new chemical paradigm.

I. Preliminary Examination

- Physical Characterization: Note the color, crystal form, and hygroscopicity of the unknown salt. Specific colors may suggest the presence of particular metal ions (e.g., blue for hydrated copper compounds, green for nickel compounds).

- Heating Test: Place a small sample in a dry test tube and heat gently. Observe any decomposition, color changes, condensation of moisture, or evolution of gases, which may provide preliminary information about the salt's composition.

- Flame Test: Moisten a platinum or nichrome wire with concentrated hydrochloric acid, dip it into the sample, and introduce it into a non-luminous Bunsen flame. Observe the characteristic color imparted to the flame (e.g., violet for potassium, crimson for strontium, yellow for sodium).

II. Analysis of Anions

- Preliminary Tests: Conduct a series of preliminary tests to narrow down possible anions, including:

- Effervescence with dilute acid: Indicates carbonate or bicarbonate

- Test with silver nitrate: Acidify the solution with dilute nitric acid and add silver nitrate solution. Observe the precipitate formed (white - chloride, pale yellow - bromide, yellow - iodide)

- Test with barium chloride: Add barium chloride solution to an acidified sample. A white precipitate indicates sulfate.

- Confirmatory Tests: Perform specific confirmatory tests for anions suggested by the preliminary tests to verify their presence.

III. Analysis of Cations

- Preparation of Solution: Prepare a solution of the salt in distilled water or dilute acid if insoluble in water alone.

- Group Separation: Systematically separate cations into groups using the following scheme:

- Group I (Silver Group): Precipitate as chlorides with dilute HCl

- Group II (Copper Group): Precipitate as sulfides with Hâ‚‚S in acidic medium

- Group III (Iron Group): Precipitate as sulfides with Hâ‚‚S in basic medium

- Group IV (Calcium Group): Precipitate as carbonates with ammonium carbonate

- Group V (Soluble Group): Remain in solution after preceding separations

- Identification: Systematically identify each cation within its group using specific confirmatory tests.

This systematic protocol, with its logical flow and specific tests, represents the culmination of the transition from alchemical practices to methodical chemical analysis. The process can be visualized through the following workflow:

Historical Experimental Protocol: Fire Assay for Metals

The fire assay technique, perfected by alchemists and early metallurgists, represents one of the earliest systematic analytical methods. The following protocol, based on historical practices, demonstrates the sophisticated approach to metal analysis that existed even before the formal establishment of chemistry as a science:

Sample Preparation:

- Grind the ore or metal sample to a fine powder to ensure homogeneity and complete reaction.

- Weigh accurately using a balance, establishing the initial mass for quantitative determination.

Fusion:

- Mix the sample with appropriate fluxes (typically lead oxide, borax, and soda) in a fire clay crucible.

- The fluxes serve specific functions: lead oxide acts as a collector for precious metals, borax lowers the melting point, and soda creates a basic environment for silica dissolution.

Heating:

- Heat the crucible in a furnace to approximately 1000-1200°C until the contents become molten and reactions are complete.

- Maintain temperature for a specific period to ensure complete separation of the precious metals from the gangue (worthless rock material).

Separation:

- After cooling, break the crucible to retrieve the lead button containing the precious metals.

- Place the lead button in a porous bone ash cupel and heat in a oxidizing atmosphere.

- The lead oxidizes to litharge (PbO), which is absorbed by the cupel, leaving behind a precious metal prill.

Quantification:

- Weigh the precious metal prill to determine the metal content of the original sample.

- Calculate the concentration based on the initial sample mass and final prill mass.

This methodology, with its careful control of conditions and quantitative measurements, achieved approximately 95% accuracy in precious metal recovery according to historical analyses [13]. It established important precedents for systematic analytical approaches that would later be applied more broadly in chemistry.

Legacy and Implications for Modern Research

The systematic foundations of qualitative analysis established during the transition from alchemy to chemistry continue to influence contemporary research practices, particularly in pharmaceutical development and analytical chemistry. The methodological rigor introduced by figures like Lavoisier and Boyle remains essential in modern drug discovery, where reproducible results and standardized protocols are critical for regulatory approval and clinical application [10].

Modern analytical techniques, including spectroscopy, chromatography, and mass spectrometry, represent the technological evolution of the basic principles established during this historical transition [10]. While these contemporary methods offer vastly improved sensitivity and specificity, they retain the fundamental logical structure of systematic qualitative analysis: hypothesis-driven investigation, controlled experimentation, and reproducible identification based on characteristic properties.

The historical development of qualitative analysis also offers important lessons for contemporary research methodology. The transition from alchemy to chemistry demonstrates how empirical observations, when systematically organized and subjected to theoretical framework, can evolve from artisanal practices to predictive science [10]. This historical precedent underscores the importance of maintaining rigorous standards in documentation, reproducibility, and methodological transparency—principles that remain essential for advancing scientific knowledge and its applications in drug development and other research fields.

For today's researchers and scientists, understanding this historical context provides valuable perspective on the epistemological foundations of their disciplines. The systematic approaches to qualitative analysis developed during the emergence of modern chemistry established patterns of scientific thinking that continue to guide research methodology, experimental design, and analytical verification in contemporary scientific practice.

The 18th century witnessed a fundamental transformation in chemical science, marking a decisive shift from qualitative observations to quantitative measurement. This revolution, central to the broader Chemical Revolution, established the foundational principles that would enable chemistry to evolve into a modern, predictive science. At the forefront of this change were Antoine Lavoisier and Joseph Louis Proust, whose systematic application of measurement—particularly through the chemical balance—introduced a new standard of precision and rigor. Their work replaced speculative systems with empirical data, leading to the overthrow of the phlogiston theory, the establishment of mass conservation, and the formulation of the law of definite proportions. This whitepaper examines the methodological innovations of Lavoisier and Proust, detailing the experimental protocols that underpinned this paradigm shift and analyzing their profound and lasting impact on the field of analytical chemistry, especially within modern contexts like pharmaceutical development.

The Pre-Quantitative Era: Phlogiston and Qualitative Chemistry

Prior to the late 18th century, Western chemistry was dominated by the phlogiston theory to explain combustion and calcination (the process of metals turning into calxes, or oxides). This theory postulated that all combustible materials contained a fire-like element called "phlogiston," which was released into the air during burning. A major weakness of this system was its qualitative and non-predictive nature; it described observations without a basis in measurable quantities. Furthermore, the theory struggled to explain why metals often gained weight during calcination (a process supposedly involving the loss of phlogiston). The prevailing chemical nomenclature was also chaotic, with substances named for their origin, appearance, or supposed medicinal properties (e.g., "oil of vitriol" for sulfuric acid), which hindered clear scientific communication and the systematic progression of knowledge [14]. This was the intellectual environment into which Lavoisier and Proust introduced their rigorous, quantitative methods.

Lavoisier: The Architect of the Chemical Revolution

Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-1794) is rightly considered the central figure of the Chemical Revolution. His most critical contribution was instituting the systematic use of the chemical balance in all experimental work, transforming chemistry into a quantitative science [15] [16]. He insisted on precise mass measurements of all reactants and products, which led him to formulate the law of conservation of mass—the principle that matter is neither created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction [16]. This principle became the cornerstone of modern chemistry. Using this methodology, Lavoisier demonstrated that combustion and calcination involved the combination of a substance with oxygen from the air, thereby conclusively disproving the phlogiston theory [17] [16]. His work showed that the weight gained by a metal during calcination was exactly equal to the weight of air absorbed in the process [16].

Key Experimental Protocol: The Mercury Calcination Experiment

Lavoisier's classic experiment on the calcination of mercury exemplifies his quantitative approach [17] [16].

- 1. Objective: To determine the role of air in the calcination of metals and to test the phlogiston theory.

- 2. Materials:

- Mercury (Hg)

- A known volume of air in a sealed system

- A glass retort and jar apparatus

- A precision balance

- 3. Procedure:

- A measured quantity of mercury was placed in a retort connected to a jar standing in a mercury bath, enclosing a known volume of air.

- The mercury was heated for several days until a red calx (mercuric oxide, HgO) formed on its surface.

- The system was allowed to cool, and it was observed that the volume of air had decreased by approximately one-fifth.

- The remaining air was tested and found to be unable to support combustion or life (it was "azote," later named nitrogen).

- The mercuric oxide calx was then collected and heated more strongly in a separate apparatus.

- The calx decomposed back into mercury and a gas was released.

- 4. Measurements and Data:

- The mass of the mercury before heating and after being converted to calx was measured.

- The volume of air before and after the first heating was recorded.

- The mass of the gas released from the decomposed calx was inferred by weighing the remaining mercury.

- 5. Interpretation and Conclusion: Lavoisier found that the gas released from the mercuric oxide was "pure air" (oxygen) and that it was this portion of the air that had combined with the mercury to form the calx. The total mass of the system remained unchanged. This experiment provided direct, quantitative evidence that combustion is a process of combination with oxygen, not the release of phlogiston.

Development of Systematic Nomenclature

In 1787, Lavoisier, along with colleagues Guyton de Morveau, Berthollet, and Fourcroy, published the Méthode de Nomenclature Chimique [14] [16]. This new system replaced the old, nonsystematic names with a logical one based on composition. For example, it introduced suffixes like -ide for binary compounds and -ate for salts containing oxygen [14]. This reform embedded the principles of the Chemical Revolution directly into the language of chemistry, allowing for the precise and unambiguous communication of chemical composition and reactions, a critical requirement for an advanced analytical science.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Contributions of Lavoisier and Proust

| Scientist | Key Contribution | Core Principle | Impact on Analytical Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antoine Lavoisier | Law of Conservation of Mass | Matter is conserved in chemical reactions; total mass of reactants equals total mass of products [16]. | Established the balance as the fundamental instrument of chemical analysis, enabling stoichiometric calculations. |

| Antoine Lavoisier | Oxygen Theory of Combustion | Combustion and calcination involve reaction with oxygen, not release of phlogiston [17] [16]. | Provided a correct theoretical framework for understanding oxidation-reduction reactions. |

| Antoine Lavoisier | Systematic Chemical Nomenclature | Names of compounds should reflect their chemical composition [14] [16]. | Standardized communication, allowing for the clear and efficient sharing of analytical findings. |

| Joseph Louis Proust | Law of Definite Proportions | A given chemical compound always contains its constituent elements in fixed and constant mass proportions [18] [19]. | Established the fundamental concept of chemical compounds, distinguishing them from mixtures and enabling formula determination. |

Proust: Establishing the Law of Definite Proportions

The Foundation of Chemical Stoichiometry

Joseph Louis Proust (1754-1826), a French chemist working for much of his career in Spain, built upon Lavoisier's quantitative methods to make a discovery of equal importance. Through meticulous analysis of various compounds, particularly metallic oxides and sulfides, Proust formulated the Law of Definite Proportions (or Proust's Law) between 1794 and 1804 [18] [19]. This law states that a chemical compound is always composed of the same elements in the same constant mass ratio, regardless of its source or method of preparation [19]. For example, he demonstrated that copper carbonate, whether prepared in the laboratory or derived from mineral sources, always contained the same proportions of copper, carbon, and oxygen [19]. This principle established the very definition of a pure chemical compound and laid the groundwork for stoichiometry, the study of quantitative relationships in chemical reactions.

Key Experimental Protocol: Analysis of Copper Carbonates

Proust's defense of his law against Claude-Louis Berthollet (who argued for variable composition) was based on exhaustive and reproducible analyses [18] [19].

- 1. Objective: To demonstrate that copper carbonate has a constant composition, unlike a physical mixture.

- 2. Materials:

- Samples of copper carbonate from natural minerals (e.g., malachite)

- Copper carbonate synthesized in the laboratory

- Nitric acid (for dissolution)

- Sodium hydroxide or potassium carbonate (for precipitation)

- Precision balance

- 3. Procedure (Gravimetric Analysis):

- A precise mass of a natural copper carbonate mineral was dissolved in nitric acid, producing copper nitrate, carbon dioxide, and water.

- A solution of sodium hydroxide or potassium carbonate was then added to the copper nitrate solution to precipitate copper carbonate.

- The precipitate was filtered, carefully washed, dried, and weighed.

- The mass of the precipitated copper carbonate was compared to the mass of the original mineral sample.

- The same procedure was repeated with copper carbonate synthesized from pure copper and carbonates.

- 4. Measurements and Data: Proust consistently found that the ratio of copper to carbon to oxygen by mass was identical in both the natural and synthetic samples. Any variations fell within his experimental error, which he worked tirelessly to minimize.

- 5. Interpretation and Conclusion: The invariant mass composition provided robust evidence for the Law of Definite Proportions. Proust generalized this finding, stating that "iron is... subject by that law of nature which presides over all true combinations, to two constant proportions of oxygen. It does not at all differ in this regard from tin, mercury, lead etc." [18]. This established that compounds are distinct entities with a fixed atomic architecture.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual shift in chemical composition understanding driven by Lavoisier's and Proust's work.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Instruments

The work of Lavoisier and Proust was enabled by a suite of instruments and reagents that formed the core of the 18th-century analytical laboratory. The following table details these essential tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials in 18th-Century Quantitative Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Analysis | Specific Example of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Balance | To obtain accurate mass measurements of reactants and products, the fundamental data for quantitative analysis [15]. | Used by Lavoisier to prove mass conservation in mercury calcination [16] and by Proust to determine fixed mass ratios in copper carbonate [19]. |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) | As an analytical reagent to precipitate metal sulfides from solution, allowing for their separation and quantitative analysis [20] [18]. | Proust developed its use to separate and analyze metals like copper and lead, contributing to his data for the law of definite proportions [20]. |

| Aqua Regia | A mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid, used to dissolve noble metals such as platinum and gold [20]. | Proust used aqua regia to purify platinum, separating it from other metals in Spanish colonial ores [20]. |

| Standard Solutions | Solutions of known concentration used in volumetric (titrimetric) analysis to determine the concentration of an analyte [14]. | While refined by Gay-Lussac, the principles were established by Lavoisier's quantitative approach. Used to analyze acidity or metal ion concentration. |

| Oxygen Gas (Oâ‚‚) | The key reactive gas identified by Lavoisier, used to study combustion, respiration, and the formation of oxides [17] [16]. | Central to Lavoisier's experiments demonstrating that combustion is reaction with oxygen, not phlogiston release [16]. |

| 1-(Pyrazin-2-yl)ethanethiol | 1-(Pyrazin-2-yl)ethanethiol, MF:C6H8N2S, MW:140.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-(Pentan-2-yl)azetidine | 2-(Pentan-2-yl)azetidine|Research Chemical | This high-purity 2-(Pentan-2-yl)azetidine is a valuable azetidine scaffold for medicinal chemistry and drug discovery research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Experimental Workflows in Gravimetric Analysis

The definitive quantitative method of the 18th century was gravimetric analysis, which relies on the precise measurement of mass. The workflow established by Proust for analyzing compound composition is a classic example of this technique, the principles of which are still taught and used today. The following diagram outlines the general workflow and its specific application in Proust's experiments.

Impact and Legacy in Modern Analytical Science and Drug Development

The quantitative spirit championed by Lavoisier and Proust forms the bedrock of modern chemical and pharmaceutical practice. Their legacy is not merely historical but is actively embedded in contemporary research and quality control protocols.

Foundation for Atomic Theory and Stoichiometry: Proust's Law of Definite Proportions provided the critical experimental evidence that John Dalton required to propose his atomic theory in the early 19th century. The fixed mass ratios of compounds naturally suggested that they were formed by the combination of atoms of fixed mass. This, combined with Lavoisier's conservation of mass, established stoichiometry as a core field of chemistry, allowing for the precise calculation of reactant and product quantities in industrial processes [19].

Standardization and Purity Control in Pharmaceuticals: The Law of Definite Proportions is a fundamental principle underlying the regulation of pharmaceuticals. The efficacy and safety of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) are dependent on its exact chemical structure and purity [19]. For example, a 500 mg acetaminophen tablet must contain precisely that mass of the pure compound to be effective and safe. Any significant deviation, as would occur if the compound did not obey Proust's law, would render the drug unreliable. Gravimetric analysis and its modern chromatographic and spectroscopic descendants are used to enforce this standard, ensuring every batch of a drug has the defined composition [19].

Modern Analytical Techniques: The conceptual framework of quantitative measurement pioneered by Lavoisier and Proust is the direct ancestor of all modern analytical techniques. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Mass Spectrometry, and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy are sophisticated tools that ultimately provide quantitative data on the identity, structure, and purity of chemical substances. The requirement for precise, reproducible data that these techniques fulfill was first established as a non-negotiable standard of chemical practice during the 18th-century shift.

The 18th-century shift, led by Lavoisier and Proust, was a watershed moment in the history of science. By insisting on quantitative precision, experimental rigor, and systematic logic, they transformed chemistry from a qualitative and speculative pursuit into a true physical science. Lavoisier's conservation of mass and Proust's law of definite proportions provided the indispensable foundation for all subsequent chemical theory, including atomic theory and stoichiometry. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, this legacy is ever-present. The rigorous standards of purity, composition, and measurement that govern modern laboratories are the direct descendants of the principles established in the chemical revolution, ensuring that the quantitative spirit of Lavoisier and Proust continues to drive scientific progress and safeguard public health.

The 19th century witnessed a profound transformation in analytical chemistry, marking a pivotal shift from purely chemical methods to physically-oriented instrumentation. This period established the foundational principles that would shape modern chemical analysis, moving the discipline from its empirical roots toward more rational scientific activities [21]. The introduction of sophisticated instruments represented more than mere technical improvement; it constituted a revolutionary change in how chemists interrogated matter. This revolution was characterized by the integration of precision measurement, physical principles, and standardized methodologies that enabled more accurate, reliable, and reproducible analyses [22]. The development of balances, spectroscopes, and electrochemical tools during this era not only enhanced analytical capabilities but also fundamentally altered the relationship between chemists and their objects of study, paving the way for the instrumental dominance that would characterize 20th-century analytical chemistry [23].

This transition positioned analytical chemistry as an autonomous branch of chemistry, gradually expanding its role from exclusively serving chemical science toward supporting diverse fields including environmental monitoring, health sciences, and industrial quality control [21]. The 19th-century instrumental revolution established the essential toolkit that would enable these broader applications, creating a paradigm in which instruments served as intermediaries that extended human sensory capabilities and provided unprecedented access to the molecular world. By examining the specific developments in balances, spectroscopes, and electrochemical tools, we can trace the critical trajectory that transformed analytical chemistry from its qualitative origins to the sophisticated quantitative science we recognize today.

Historical Context: The Shift from Classical to Instrumental Methods

Prior to the 19th century, analytical chemistry relied predominantly on what historians would later term "wet chemistry" techniques—methods based primarily on chemical reactions and visual observations [22]. Analysts determined chemical composition through a series of known reactions, observing color changes, precipitate formation, or gas evolution to identify unknown substances [23]. While these methods could be elegant in their simplicity, they suffered from significant limitations in specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy. The qualitative traditions of the 18th century, though systematically refined through classification systems and reaction schemes, provided limited quantitative data and often required substantial amounts of sample and time [22].

The 19th century ushered in a new epistemological approach where instruments became central to chemical investigation. This transition was part of a broader scientific revolution characterized by the rising importance of instrumentation across multiple disciplines [23]. Several interconnected factors drove this transformation in chemistry:

- Industrial demands: The Industrial Revolution created pressing needs for standardized materials, quality control in manufacturing, and analysis of ores and alloys, driving the development of more precise analytical tools [22]

- Theoretical advances: Growing understanding of physics principles, particularly in optics and electricity, provided the theoretical foundation for new instrumental approaches

- Technological innovations: Improvements in manufacturing capabilities enabled the production of more precise mechanical and optical components

- Professionalization of science: The emergence of chemistry as a distinct profession with specialized training and research agendas created an environment conducive to instrumental innovation

This period saw analytical chemistry move gradually from its pure empirical nature toward more rational scientific activities, transforming itself into an autonomous branch of chemistry [21]. The instrumental revolution of the 19th century thus established the essential foundation upon which the more dramatic innovations of the 20th century would build, including the semi-automated analytic instruments that would trigger what some scholars have termed the "second chemical revolution" between 1945 and 1965 [24].

The Precision Balance: Quantifying Matter with Accuracy

Technical Evolution and Mechanisms

The precision balance represents one of the most fundamental instrumental advances of the 19th century, enabling the transition from qualitative observation to quantitative measurement in chemistry. Early mechanical balances evolved significantly throughout the century, with key improvements in beam design, bearing mechanisms, weight calibration, and damping systems. These innovations progressively reduced measurement uncertainty while increasing weighing speed and operational convenience.

The analytical balance developed during this period offered unprecedented accuracy, becoming indispensable for both qualitative and quantitative analyses [22]. The precision achieved in these instruments made gravimetric analysis—a technique relying on measuring the mass of a substance to determine relative quantities of components in a mixture—a reliable quantitative method [22] [8]. This was particularly crucial for applications in pharmaceutical formulation and metallurgical analysis, where small measurement errors could have significant consequences.

Table 1: Evolution of Precision Balance Capabilities in the 19th Century

| Period | Typical Capacity | Precision | Key Innovations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 19th Century | 100-200g | ±10mg | Brass beams, knife-edge bearings | Apothecary uses, educational demonstrations |

| Mid-19th Century | 50-100g | ±1mg | Glass enclosures, mechanical tare | Pharmaceutical compounding, basic research |

| Late 19th Century | 25-50g | ±0.1mg | Damped oscillations, precision weights | Elemental analysis, metallurgy, advanced research |

Experimental Protocols in Gravimetric Analysis

The enhanced capabilities of precision balances enabled the development of sophisticated gravimetric methodologies. A representative protocol for determining sulfate concentration illustrates the meticulous approach required:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the sample in distilled water and acidify with hydrochloric acid to prevent precipitation of carbonates or phosphates

- Precipitation: Heat the solution nearly to boiling and slowly add excess barium chloride solution with constant stirring to form barium sulfate crystals: [ \text{Ba}^{2+}(aq) + \text{SO}4^{2-}(aq) \rightarrow \text{BaSO}4(s) ]

- Digestion: Maintain the solution at near-boiling temperature for 1-2 hours to promote particle growth and improve filterability

- Filtration: Use ashless filter paper of fine porosity, pre-weighed to ±0.1mg, and transfer all precipitate quantitatively using a rubber policeman and wash bottle

- Washing: Rinse the precipitate with small portions of hot distilled water until washings show no chloride reaction with silver nitrate test

- Ignition: Carefully fold the filter paper, place in a pre-weighed porcelain crucible, char the paper without flaming, then ignite at 800-900°C for 1 hour

- Weighing: Cool in a desiccator and weigh the crucible with barium sulfate to constant mass (±0.2mg difference between successive weighings)

- Calculation: Apply gravimetric factor to calculate sulfate content: [ \text{% SO}4^{2-} = \frac{\text{mass of BaSO}4 \times 0.4116}{\text{mass of sample}} \times 100 ]

This methodology, enabled by precision balances, allowed chemists to achieve accuracy within 0.1-0.2% for suitable analytes, establishing gravimetric analysis as the definitive reference method for quantitative analysis throughout the 19th century and beyond [22] [8].

Diagram 1: Gravimetric Analysis Workflow for Sulfate Determination

Spectroscopes: Decoding Light-Matter Interactions

Theoretical Principles and Instrumental Design

The development of spectroscopes in the 19th century fundamentally transformed chemical analysis by enabling the identification of elements through their characteristic light emissions and absorptions. The foundational principle—that each element produces unique spectral lines when heated—was established through the collaborative work of Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff, who discovered rubidium (Rb) and caesium (Cs) in 1860 using flame emissive spectrometry [8]. This period saw spectroscopy evolve from simple optical devices to sophisticated analytical instruments capable of both qualitative identification and quantitative determination [25].

The typical spectrometer design of the late 19th century incorporated several essential components:

- Light source: Flame, arc, or spark to excite sample atoms

- Sample introduction system: Various means of introducing solid or liquid samples into the excitation region

- Wavelength dispersion element: Prism or diffraction grating to separate light into constituent wavelengths

- Detection and measurement system: Visual observation, photographic plates, or early photoelectric devices

The fundamental relationship governing atomic spectroscopy is expressed as: [ \Delta E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda} ] where ΔE represents the energy difference between electronic states, h is Planck's constant, ν is frequency, c is the speed of light, and λ is wavelength. This relationship explained why each element exhibited characteristic line spectra, as the energy differences between electronic states are unique for each atomic species.

Table 2: Progression of Spectroscopic Techniques in the 19th Century

| Technique | Excitation Source | Dispersion Method | Detection Limit | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame Spectroscopy (1860s) | Bunsen burner | Prism | ~0.1% | Alkali and alkaline earth metal detection |

| Arc/Spark Spectroscopy (1870s) | Electrical discharge | Prism | ~0.01% | Metallurgical analysis, element discovery |

| Quantitative Emission Spectrometry (1890s) | Controlled spark | Improved gratings | ~0.001% | Quantitative metal analysis |

Experimental Protocol: Flame Spectroscopic Analysis of Alkali Metals

The flame test, systematically developed by Bunsen and Kirchhoff, provided a straightforward yet powerful method for elemental identification:

Apparatus Setup:

- Utilize a Bunsen burner with non-luminous flame to minimize background emission

- Employ a platinum wire fused into a glass rod as a sample holder, cleaning between tests by dipping in hydrochloric acid and heating until no color imparts to the flame

- Position a direct-vision spectroscope with calibrated wavelength scale for observation

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve solid samples in minimal hydrochloric acid to create concentrated solutions

- For refractory materials, employ borax bead tests or preliminary concentration steps

Excitation and Observation:

- Moisten the clean platinum wire with the test solution and introduce into the flame base

- Observe through the spectroscope and record the position of emission lines against the calibrated scale

- Compare with reference spectra of known elements

Characteristic Spectral Lines:

- Potassium: Doublet at 766.5 nm and 769.9 nm (violet)

- Sodium: Doublet at 589.0 nm and 589.6 nm (yellow)

- Lithium: Single line at 670.8 nm (carmine red)

- Calcium: Multiple lines including 422.7 nm, 616.2 nm, and others

Semi-Quantitative Assessment:

- Estimate concentration by comparing line intensity with standards of known concentration

- For more precise work, employ photographic recording and densitometric measurements

This methodology enabled the discovery of new elements and provided chemists with a powerful tool for rapid elemental screening, particularly for metals that were difficult to identify through wet chemical methods [8]. The sensitivity of flame tests for elements like sodium (detectable at nanogram levels) demonstrated the remarkable potential of instrumental methods to surpass traditional chemical tests in detection capability.

Diagram 2: Atomic Emission Spectroscopy Workflow

Electrochemical Tools: Harnessing Electricity for Analysis

Potentiometric and Voltammetric Foundations

The 19th century witnessed the emergence of electroanalytical chemistry as a distinct subdiscipline, founded on pioneering work in electrolysis, galvanic cells, and electrode processes. Electrochemical methods developed during this period measured the potential (volts) and/or current (amps) in electrochemical cells containing the analyte [8]. These approaches provided chemists with entirely new dimensions for chemical analysis, enabling determinations based on electrical rather than purely chemical properties.

Four main categories of electroanalytical methods emerged during this period, categorized according to which aspects of the electrochemical cell were controlled and measured:

- Potentiometry: Measurement of electrode potential under conditions of zero current

- Coulometry: Measurement of charge transfer over time

- Amperometry: Measurement of cell current over time at constant potential

- Voltammetry: Measurement of current while systematically varying the applied potential

The development of reliable reference electrodes, particularly the calomel electrode (Hg/Hgâ‚‚Clâ‚‚), provided stable reference potentials against which unknown half-cell potentials could be measured. The Nernst equation, formulated in 1889, provided the fundamental relationship between electrode potential and analyte concentration: [ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q ] where E is the measured potential, Eâ° is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is absolute temperature, n is number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, and Q is the reaction quotient.

Experimental Protocol: Potentiometric Titration of Chloride

Potentiometric methods provided an objective, quantitative approach to endpoint detection in titrations, particularly for colored or turbid solutions where visual indicators proved unreliable:

Electrode System:

- Reference electrode: Saturated calomel electrode (SCE) with potassium chloride salt bridge

- Indicator electrode: Silver wire electrode for halide determinations

- Potential measuring device: Potentiometer or high-impedance voltmeter capable of ±1 mV precision

Titration Setup:

- Prepare 0.1M silver nitrate titrant standardized against pure sodium chloride

- Transfer known volume of chloride sample to titration vessel with magnetic stirrer

- Immerse electrodes ensuring liquid junction stability of reference electrode

- Record initial potential reading before titrant addition

Titration Procedure:

- Add titrant in progressively smaller increments as endpoint approaches (1.0 mL, 0.5 mL, 0.1 mL)

- Allow potential stabilization (≤ 2 mV drift per minute) after each addition before recording volume and potential

- Continue titration until well past the equivalence point (typically 150% of expected volume)

Endpoint Determination:

- Plot potential (E) versus titrant volume (V)

- Identify endpoint as the point of maximum slope (dE/dV)

- Alternatively, calculate second derivative (d²E/dV²) to precisely locate endpoint where second derivative equals zero

Calculation: [ \text{Cl}^- \text{ concentration} = \frac{M{\text{AgNO}3} \times V{\text{eq}}}{V{\text{sample}}} \times 35.45 \text{ g/mol} ] where M is molarity of silver nitrate, Vâ‚‘q is equivalence point volume, and Vsample is sample volume

This methodology typically achieved precision of 0.5-1.0% relative standard deviation, significantly better than visual endpoint detection methods which were susceptible to subjective interpretation and limited by solution color or turbidity [8]. The development of these electrochemical methods represented a crucial step toward objective, instrument-based analysis that minimized analyst-dependent variables.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The instrumental revolution of the 19th century relied not only on sophisticated apparatus but also on carefully formulated reagent solutions that enabled precise and reproducible analyses. These reagents represented the intersection of traditional chemical knowledge with emerging instrumental approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents in 19th Century Instrumental Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Chemical Composition | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barium Chloride Solution | BaCl₂·2H₂O in distilled water | Selective sulfate precipitation | Gravimetric sulfate determination via BaSO₄ formation |

| Silver Nitrate Titrant | Standardized AgNO₃ solution | Halide quantification via precipitation | Potentiometric chloride determination, Mohr method |

| Platinum Loop/Wire | High-purity Pt wire | Sample introduction for spectroscopy | Flame tests, emission spectroscopy |

| Calomel Reference Electrode | Hg/Hgâ‚‚Clâ‚‚ in saturated KCl | Stable reference potential | All potentiometric measurements |

| Standard Buffer Solutions | Phosphate, phthalate, or borate systems | pH meter calibration | Potentiometric pH determination |

| Nessler's Reagent | Kâ‚‚HgIâ‚„ in KOH | Ammonia detection and quantification | Colorimetric ammonia determination in environmental samples |

| Standard Metal Solutions | Known concentrations of metal ions | Quantitative calibration | Spectroscopy calibration curves |

| GlehlinosideC | GlehlinosideC, MF:C26H32O13, MW:552.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| z-4-Nitrocinnamic acid | z-4-Nitrocinnamic acid, MF:C9H7NO4, MW:193.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Impact and Legacy: Paving the Way for Modern Analytical Chemistry

The instrumental revolution of the 19th century established the conceptual and technical foundation for contemporary analytical science. The integration of balances, spectroscopes, and electrochemical tools into chemical practice created a new paradigm in which instrumentation, standardization, and physical measurement became central to analytical chemistry [23]. This transition positioned the discipline for the dramatic developments that would follow in the 20th century, including the rise of semi-automated instruments that would trigger what Davis Baird identified as the "second chemical revolution" between 1945 and 1965 [24] [23].

The legacy of 19th-century instrumentation is particularly evident in several enduring principles of modern analytical chemistry:

- The calibration paradigm: The practice of creating calibration curves by comparing instrument response to known standards, essential for analyzing unknown samples, became established methodology [25]

- Hybrid techniques: The combination of separation methods with detection techniques, prefigured by the coupling of chemical separations with instrumental measurements, would evolve into powerful hyphenated techniques like GC-MS and LC-MS [8]

- Automation trends: The drive toward reducing human error and variability through instrumental measurement established the conceptual foundation for the automated analyzers that would transform analytical laboratories in the late 20th century [24]

- Interdisciplinary applications: The expansion of analytical chemistry from purely chemical questions to applications in environmental monitoring, industrial quality control, and pharmaceutical analysis began during this period and accelerated throughout the following century [21]

Perhaps most significantly, the 19th-century instrumental revolution established instrumentation as a legitimate form of chemical knowledge rather than merely supplemental to theoretical understanding [23]. This epistemological shift would prove essential as analytical chemistry continued its evolution into the digital age, with 21st-century developments in big data, machine learning, and miniaturized sensors all building upon the foundational principles established during the instrumental revolution of the 1800s [8]. The balances, spectroscopes, and electrochemical tools of this period thus represent not merely historical curiosities but the essential precursors to the sophisticated analytical instrumentation that continues to drive scientific discovery today.

The field of analytical chemistry has undergone a profound transformation, entering a modern era characterized by instrumental dominance and significant interdisciplinary impact. This shift moves the discipline beyond its traditional role of mere chemical identification, positioning it as a central pillar in solving complex challenges across pharmaceuticals, environmental science, and systems biology. The integration of advanced instrumentation with sophisticated data analytics has enabled researchers to achieve unprecedented levels of sensitivity, specificity, and throughput. This article explores the key technological drivers, detailed experimental methodologies, and expansive applications that define contemporary analytical chemistry, framing these developments within its broader historical evolution as an indispensable scientific discipline.

Key Trends and Market Drivers

The current landscape of analytical chemistry is shaped by several convergent trends. The push for sustainability has catalyzed the adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles, promoting techniques that reduce solvent consumption and waste, such as supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) and microextraction methods [26]. Simultaneously, the demand for rapid, on-site results is driving the development and deployment of portable and miniaturized devices for real-time monitoring in environmental and forensic science [26].

Perhaps the most transformative trend is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). AI algorithms are now essential for processing the massive datasets generated by modern instrumentation, identifying patterns and anomalies that elude human analysts. In high-throughput screening and chromatographic method development, AI and automation are streamlining workflows and reducing human error [26].