From Spectra to Solutions: The Origins and Evolution of Chemometrics in Optical Spectroscopy

This article traces the historical and technical development of chemometrics in optical spectroscopy, a field born from the need to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data.

From Spectra to Solutions: The Origins and Evolution of Chemometrics in Optical Spectroscopy

Abstract

This article traces the historical and technical development of chemometrics in optical spectroscopy, a field born from the need to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data. It explores the foundational principles established in the mid-20th century, the evolution of key multivariate algorithms like PCA and PLS, and their critical application in modern drug development for quantitative analysis and quality control. The discussion extends to contemporary challenges in model optimization, calibration transfer, and the emerging role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in enhancing predictive accuracy and automating analytical processes for biomedical and clinical research.

The Data Deluge: How Spectroscopy's Evolution Forged a New Mathematical Discipline

Before the advent of chemometrics, spectroscopic analysis relied almost exclusively on univariate methodologies—the practice of correlating a single spectral measurement (typically absorbance at one wavelength) to a property of interest (typically concentration) [1]. This approach, while conceptually straightforward and mathematically simple, imposed significant limitations on the complexity of problems that could be solved using optical spectroscopy. The foundational principle governing this era was the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length of light through the solution [2]. Expressed mathematically as ( A = \epsilon \cdot c \cdot l ), where ( A ) is absorbance, ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity coefficient, ( c ) is concentration, and ( l ) is the path length, this law formed the bedrock of quantitative spectroscopic analysis for decades [2]. Researchers and analysts depended on this direct, one-dimensional relationship, utilizing instruments that were essentially sophisticated implementations of this core principle.

The instrumentation of this period, though innovative for its time, presented significant constraints. UV-Vis spectrophotometers consisted of fundamental components: a light source (typically tungsten/halogen for visible and deuterium for UV), a wavelength selection device (monochromator or filter), a sample compartment, and a detector (such as a photomultiplier tube or photodiode) [2]. These systems were designed to measure the attenuation of light at specific wavelengths, providing the raw data for univariate analysis. This technological paradigm, while enabling tremendous advances in chemical analysis, ultimately proved insufficient for the increasingly complex analytical challenges that emerged in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to natural product discovery, thereby creating the necessary conditions for the multivariate revolution that chemometrics would eventually bring [1].

Core Principles and Instrumentation of Early Spectroscopic Analysis

The pre-chemometrics era was defined by spectroscopic systems and methodologies that extracted information through isolated, single-wavelength measurements. The fundamental design and operational principles of these instruments directly shaped the analytical capabilities and limitations of the time.

Instrumentation and Measurement Fundamentals

Early spectroscopic systems were engineered to implement the Beer-Lambert law with precision and reliability. The monochromator, a centerpiece of these instruments, served to isolate narrow wavelength bands from a broader light source. These devices typically employed diffraction gratings with groove densities ranging from 300 to 2000 grooves per millimeter, with 1200 grooves per millimeter being common for balancing resolution and wavelength range [2]. The quality of these optical components directly influenced measurement quality; ruled diffraction gratings often contained more physical imperfections compared to the later-developed blazed holographic diffraction gratings, which provided significantly superior optical performance [2].

Sample presentation followed standardized approaches designed to maximize reproducibility within technical constraints. Cuvettes with a standard 1 cm path length were most common, though specialized applications sometimes required shorter path lengths down to 1 mm when sample volume was limited or analyte concentrations were high [2]. The choice of cuvette material was critical and constrained by wavelength requirements: plastic cuvettes were unsuitable for UV measurements due to significant UV absorption, standard glass cuvettes absorbed most light below 300-350 nm, and quartz cuvettes were necessary for UV examination because of their transparency across the UV spectrum [2]. These physical constraints of the measurement system inherently limited the types of analyses that could be performed successfully.

The Univariate Data Model

In univariate analysis, the analytical model was fundamentally simple: one wavelength measurement corresponded to one analyte concentration. The data structure for a calibration set consisted of a single vector of absorbance measurements at a chosen wavelength for each standard solution, correlated with a corresponding vector of known concentrations. This model assumed that absorbance at the selected wavelength was exclusively attributable to the target analyte, and that any variation in the measurement was normally distributed random error that could be averaged out through replication [1].

The process for method development followed a systematic but limited protocol:

- Spectral Scanning: Obtain a full absorbance spectrum of the pure analyte to identify its wavelength of maximum absorption (( \lambda_{max} )).

- Wavelength Selection: Choose ( \lambda_{max} ) for quantification to maximize sensitivity.

- Calibration Curve: Measure absorbance at ( \lambda_{max} ) for a series of standard solutions with known concentrations.

- Linear Regression: Establish the relationship between absorbance and concentration through the equation ( A = \epsilon \cdot c \cdot l + \text{error} ).

- Sample Analysis: Measure unknown samples at the same wavelength and calculate concentration using the established calibration curve.

This straightforward approach proved adequate for simple systems but contained critical underlying assumptions that would prove problematic for complex samples: specificity of the measurement, linear response across the concentration range, and absence of significant interfering phenomena.

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Early UV-Vis Spectrophotometers

| Component | Implementation in Pre-Chemometrics Era | Technical Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Dual lamps: Tungsten/Halogen (Vis), Deuterium (UV) | Required switching between sources at 300-350 nm; Intensity fluctuations over time [2] |

| Wavelength Selection | Monochromators with ruled diffraction gratings (300-2000 grooves/mm) | Physical imperfections in gratings; Limited optical resolution compared to modern systems [2] |

| Sample Containment | Quartz cuvettes (UV), Glass cuvettes (Vis), Standard 1 cm path length | Quartz expensive; Limited path length options; Precise alignment required [2] |

| Detection | Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs), Photodiodes | PMTs required high voltage; Limited dynamic range; Signal drift [2] |

Critical Limitations of Univariate Spectroscopic Analysis

The simplicity of the univariate approach belied significant methodological vulnerabilities that became increasingly problematic as analytical challenges grew more complex. These limitations emerged from fundamental spectroscopic phenomena and instrumental constraints that univariate methods could not adequately address.

Spectral Interference and Lack of Specificity

The most significant limitation of univariate analysis was its inability to deconvolve overlapping absorption bands from multiple analytes in a mixture [3] [4]. When compounds with similar chromophores were present simultaneously, their individual absorption spectra would superimpose, creating composite spectra where the contribution of individual components became indistinguishable [4]. This fundamental lack of specificity meant that absorbance at a single wavelength often represented the sum of contributions from multiple species, leading to positively biased concentration estimates for the target analyte [3].

Analysts attempted to mitigate these issues through methodological adjustments, including sample pre-treatment techniques such as extraction, filtration, and centrifugation to physically separate interfering compounds [4]. Other strategies included wavelength switching (selecting an alternative, less-specific wavelength with fewer interferents) and derivatization (chemically modifying the analyte to shift its absorption maximum away from interferents) [4]. However, these approaches increased analysis time, introduced additional sources of error, and often proved inadequate for complex matrices like natural product extracts or biological fluids [5] [4].

Sensitivity and Detection Limit Constraints

The univariate era faced significant challenges in detecting analytes at low concentrations, constrained by both instrumental limitations and fundamental spectroscopic principles. The effective dynamic range of Beer-Lambert law application was practically limited to absorbances below 1.0, as values exceeding this threshold resulted in insufficient light reaching the detector—less than 10% transmission—compromising measurement reliability [2]. This limitation necessitated either sample dilution or reduction of path length for concentrated samples, each approach introducing potential for error [2].

Instrumental noise from light source fluctuations, detector limitations, and environmental interference established practical detection boundaries that were particularly problematic for trace analysis [3] [4]. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) became a critical factor in determining reliable detection limits, with a benchmark SNR of 3:1 typically considered the minimum for confident detection [3]. While analysts could enhance sensitivity somewhat by optimizing path length or selecting wavelengths with higher molar absorptivity, these strategies offered limited gains against the fundamental constraints of instrumentation and the Beer-Lambert relationship itself [3].

Matrix Effects and Environmental Sensitivities

Complex sample matrices presented particularly formidable challenges for univariate spectroscopic methods. Matrix effects—where surrounding components in a sample altered the absorbance properties of the target analyte—were commonplace in biological, environmental, and pharmaceutical samples [4]. These effects could manifest as apparent enhancements or suppressions of absorbance, leading to inaccurate quantitation [4]. While matrix-matching of calibration standards offered some mitigation, this approach required thorough characterization of the sample matrix, which was often impractical for complex or variable samples [4].

Environmental factors introduced additional variability that compromised analytical precision. Temperature variations posed multiple problems: they could cause spectral shifts in absorption peaks due to altered molecular vibrations, modify solvent properties such as viscosity and refractive index, and even accelerate sample degradation for thermally labile compounds [4]. These sensitivities necessitated rigorous environmental control measures that were often difficult to maintain in routine analytical settings, contributing to method irreproducibility.

Table 2: Primary Limitations of Univariate Spectroscopic Analysis and attempted Mitigation Strategies

| Limitation Category | Specific Technical Challenges | Contemporary Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Interference | Overlapping absorption bands; Composite spectra from multiple chromophores; Non-specific measurements [3] [4] | Selective extraction; Wavelength optimization; Derivatization chemistry; Sample purification [4] |

| Sensitivity Constraints | Limited dynamic range (A < 1.0); Detector noise at low light levels; Poor signal-to-noise ratio for trace analysis [3] [2] | Path length optimization; Pre-concentration techniques; Signal averaging; Higher intensity light sources [3] |

| Matrix & Environmental Effects | Matrix-induced absorbance suppression/enhancement; Temperature-dependent spectral shifts; Solvent property variations [4] | Matrix-matched standards; Temperature control; Solvent selection; Kinetic methods for reaction monitoring [4] |

| Chemical & Physical Artifacts | Photodegradation of analytes during measurement; Chemical reactions in sample cuvette; Light scattering from particulates [4] | Light-blocking sample containers; Rapid analysis protocols; Filtration and centrifugation; Stabilizing agents [4] |

Experimental Protocols in the Univariate Paradigm

The methodological constraints of the pre-chemometrics era necessitated rigorous, multi-step experimental protocols designed to maximize reliability within the limitations of univariate analysis. These procedures emphasized purity, stability, and environmental control to generate analytically useful results.

Protocol for Natural Product Analysis via UV Spectroscopy

The analysis of natural products exemplifies the sophisticated methodologies developed to work within univariate constraints. Drawing from historical applications in drug discovery where natural products were crucial sources of bioactive compounds [5], a typical protocol would involve:

Sample Preparation:

- Extract plant or microbial material using appropriate solvent (methanol, ethanol, or water) through maceration or Soxhlet extraction [5].

- Concentrate extract under reduced pressure using rotary evaporation.

- Perform preliminary purification via liquid-liquid extraction or column chromatography to isolate compound classes [5].

- Filter final solution through 0.45μm membrane to remove particulate matter.

Instrument Calibration:

- Prepare standard solutions of reference compound in exact matrix as samples.

- Generate calibration curve with minimum of five concentration levels across working range.

- Verify linearity with correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.995.

- Include daily verification of wavelength accuracy using holmium oxide or didymium filters.

Spectroscopic Measurement:

- Scan from 200-800 nm to identify characteristic absorption maxima.

- Select primary analytical wavelength at ( \lambda_{max} ) and secondary wavelength for confirmation.

- Measure samples and standards in triplicate with blank subtraction.

- Maintain constant temperature using thermostatted cuvette holder (±0.5°C).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate concentrations using Beer-Lambert law with extinction coefficient from standards.

- Apply blank correction and dilution factors.

- Report mean values with standard deviation from replicates.

This protocol, while methodologically sound, remained vulnerable to co-extracted interferents with similar chromophores that could not be resolved without separation techniques [5].

Method Validation Approaches

In the absence of multivariate validation techniques, univariate methods relied on extensive verification procedures:

- Specificity Assessment: Compare absorption spectra of pure standards versus sample extracts to identify potential interferents [4].

- Linearity Verification: Analyze standard curves across stated concentration range with minimum R² requirement.

- Precision Evaluation: Perform repeated measurements (n=6) of homogeneous sample to determine relative standard deviation.

- Detection Limit Estimation: Establish based on signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 for lowest detectable concentration [3].

These validation approaches, while comprehensive for their time, could not fully compensate for the fundamental limitations of single-wavelength measurements in complex matrices.

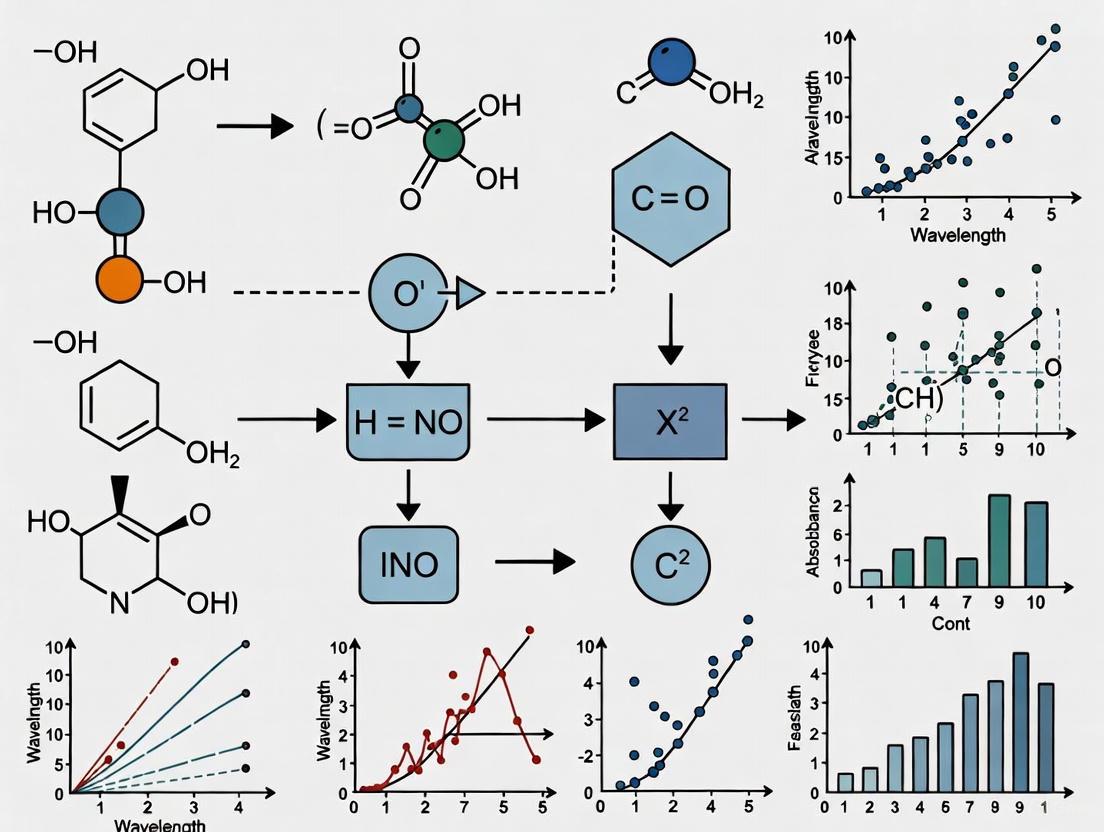

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for univariate spectroscopic analysis showing iterative interference mitigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The practical implementation of univariate spectroscopic analysis required carefully selected reagents and materials designed to maximize measurement accuracy within technological constraints. These fundamental tools formed the basis of reliable spectroscopy in the pre-chemometrics era.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Univariate Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Technical Specification | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | High-purity quartz; 1 cm standard path length; Optical clarity 200-2500 nm | Sample containment with minimal UV absorption; Standardized path length for Beer-Lambert law [2] |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | HPLC-grade solvents; Low UV cutoff: <200 nm for acetonitrile, <210 nm for methanol | Sample dissolution and dilution; Matrix for calibration standards; Minimal background absorption [2] |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Certified reference materials; Purity >99.5%; Documented uncertainty | Calibration curve generation; Instrument performance verification; Method validation [1] |

| Holmium Oxide Filters | Certified wavelength standards; Characteristic absorption peaks | Wavelength accuracy verification; Instrument performance qualification [1] |

| Buffer Systems | High-purity salts; pH-stable formulations; Minimal absorbance in UV | Maintain analyte stability; Control chemical environment; Minimize pH-dependent spectral shifts [4] |

| zinc;dioxido(dioxo)chromium | zinc;dioxido(dioxo)chromium, CAS:13530-65-9, MF:CrH2O4Zn, MW:183.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Ethylquinoxalin-2(1H)-one | 3-Ethylquinoxalin-2(1H)-one, CAS:13297-35-3, MF:C10H10N2O, MW:174.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Inevitable Transition Toward Multivariate Solutions

The limitations of univariate analysis became increasingly problematic as analytical chemistry faced more complex challenges in the latter half of the 20th century. In pharmaceutical development, the need to characterize complex natural product extracts with overlapping chromophores highlighted the insufficiency of single-wavelength measurements [5]. In industrial settings, quality control of multi-component mixtures required faster analysis than sequential univariate measurements could provide. These pressures, combined with advancing computer technology, created the perfect environment for the emergence of chemometrics.

The transition began with recognition that spectral information existed beyond single wavelengths—that the shape of entire spectral regions contained valuable quantitative and qualitative information. Early attempts at leveraging this information included using absorbance ratios at multiple wavelengths and simple baseline correction techniques. However, these approaches still operated within a essentially univariate framework. The true paradigm shift occurred when mathematicians, statisticians, and chemists began developing genuine multivariate algorithms that could model complete spectral shapes and handle interfering signals mathematically rather than through physical separation [1].

This transition from univariate to multivariate thinking represented more than just a technical advancement—it constituted a fundamental change in how analysts conceptualized spectral data. Rather than viewing spectra as collections of discrete wavelengths, chemometrics enabled scientists to treat spectra as multidimensional vectors containing latent information that could be extracted through appropriate mathematical transformation. This conceptual shift, emerging from the documented limitations of the univariate approach, ultimately laid the foundation for modern spectroscopic analysis across pharmaceutical, industrial, and research applications.

Figure 2: Logical progression from univariate limitations to chemometrics development.

The 1960s marked a transformative period for analytical chemistry, characterized by the convergence of spectroscopic techniques and emerging computer technology. This decade witnessed the dawn of a new paradigm where computerized instruments began to handle multivariate data sets of unprecedented complexity, laying the direct groundwork for the formal establishment of chemometrics. Within optical spectroscopy research, this transition was particularly profound. Researchers moved beyond univariate analysis—which relates a single parameter to a chemical property—toward multiparameter approaches that could capture the intricate relationships governing chemical reactivity and composition [6]. This shift was driven by the recognition that chemical reactions and spectroscopic signatures are influenced by numerous factors simultaneously, often in a nonlinear manner [6]. The field's evolution from simple linear free energy relationships (LFERs) to multiparameter modeling required computational power to become practically feasible, setting the stage for the revolutionary developments that would follow in the 1970s with the formal coining of "chemometrics" [7].

The Pre-1960s Landscape: From Prisms to Parameters

Before the computer revolution, spectroscopic analysis was fundamentally limited by manual data acquisition and processing capabilities. The history of spectroscopy began with Isaac Newton's experiments with prisms in 1666, where he first coined the term "spectrum" [8] [9] [10]. The 19th century brought crucial advancements, including Joseph von Fraunhofer's detailed observations of dark lines in the solar spectrum and the pioneering work of Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen, who established that spectral lines serve as unique fingerprints for each chemical element [8] [9] [11]. By the early 20th century, scientists had developed fundamental quantitative relationships like the Beer-Lambert law for light absorption and understood that spectral data could reveal atomic and molecular structures [10].

Despite these advances, analytical chemistry remained constrained by manual computation. Researchers primarily relied on univariate calibration models, correlating a single spectroscopic measurement with a property of interest [6]. While foundational relationships like the Hammett equation (1937) and Taft parameters (1952) introduced quantitative structure-activity relationships, these typically handled only one or two variables simultaneously due to computational limitations [6]. The tedious nature of calculations meant that analyzing complex multivariate data sets was practically impossible, creating a critical bottleneck that would only be resolved with the advent of accessible computing power.

The 1960s Inflection Point: Technological Catalysts

The Computing Revolution

The 1960s witnessed the rise of mainframe computers that began to transform scientific data processing [12]. While still far from today's standards, these systems offered researchers unprecedented computational capabilities. The era saw the development of operational systems like the IBM System/360, Burroughs B5000, and Honeywell 200, which consolidated data from various business and scientific operations [12]. Particularly significant for scientific research were the emergence of minicomputers (e.g., DEC PDP-8) and time-sharing systems (e.g., MIT's CTSS), which allowed multiple users to share computing resources simultaneously—dramatically improving access to computational power [12]. Although programmable laboratory computers remained rare, the increasing availability of institutional computing centers enabled spectroscopists to process data that was previously intractable.

Instrumentation Advances

Spectroscopic instrumentation evolved significantly during this period. Improved diffraction gratings, building on Henry Rowland's 19th-century innovations, provided better spectral resolution [11]. The development of commercial spectrographs and the first evacuated spectrographs for ultraviolet measurements (e.g., for sulfur and phosphorus determination in steel) expanded practical analytical capabilities [10]. Infrared spectroscopy techniques advanced considerably due to instrumental developments during and after World War II, opening new avenues for molecular analysis [13]. These technological improvements generated increasingly complex data sets that demanded computer-assisted analysis, creating a virtuous cycle of instrumental and computational advancement.

Table 1: Key Technological Developments of the 1960s Era

| Development Area | Specific Advancements | Impact on Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Computer Systems | Mainframes (IBM System/360), Minicomputers (DEC PDP-8), Time-sharing systems (MIT CTSS) [12] | Enabled processing of complex multivariate data sets; allowed multiple users computational access |

| Spectroscopic Instruments | Improved diffraction gratings, Commercial spectrographs, Advanced IR spectroscopy techniques [13] | Generated higher-resolution, more complex data requiring computational analysis |

| Data Processing | Automatic comparators, Early pattern recognition algorithms, Batch processing systems [13] [12] | Reduced manual calculation burden; allowed analysis of larger data sets |

Early Multivariate Thinking in Chemistry

During the 1960s, a fundamental conceptual shift occurred as researchers began exploring multivariate statistical methods for chemical problems [7]. Pioneering papers discussed experimental designs, analysis of variance, and least squares regression from a theoretical chemistry perspective [7]. This period saw the earliest applications of multiple parameter correlations in chemical studies, moving beyond the limitations of single-variable approaches [6]. However, as noted in historical reviews, these pioneering works suffered from a "departmentalization of academic research," where statistical and chemical terminology diverged, limiting widespread adoption [7]. Additionally, knowledge of these multivariate methods "did not immediately reach laboratory analysts due to the more limited access to computing resources available in the 1960s" [7], creating a gap between theoretical possibility and practical application that would take another decade to bridge.

Experimental Paradigms: Multivariate Analysis in Practice

Spectral Pattern Recognition for Material Identification

One of the earliest applications of computerized multivariate analysis in spectroscopy involved pattern recognition for material identification and classification. Researchers began developing protocols to leverage the full spectral signature rather than individual peaks.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol: Spectral Pattern Recognition for Material Classification

| Step | Procedure | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation | Prepare standardized samples using reference materials; ensure consistent presentation to spectrometer | Control for physical properties (particle size, moisture); use internal standards when possible |

| 2. Spectral Acquisition | Collect spectra across multiple wavelengths using UV-Vis, IR, or fluorescence spectrometers | Standardize instrument parameters (slit width, scan speed, resolution); collect background spectra |

| 3. Data Digitization | Convert analog spectral signals to digital format using early analog-to-digital converters | Ensure adequate sampling frequency; maintain signal-to-noise ratio through multiple scans |

| 4. Feature Extraction | Identify characteristic spectral features (peak positions, intensities, widths) | Use derivative spectra to resolve overlapping peaks; normalize to correct for concentration effects |

| 5. Statistical Classification | Apply clustering algorithms or discriminant analysis to group similar spectra | Implement k-nearest neighbor or early principal component analysis; validate with known samples |

The experimental workflow for these early multivariate analyses can be visualized as follows:

Multi-Component Quantitative Analysis

A second major experimental breakthrough came from multi-component analysis, which allowed researchers to simultaneously quantify several analytes in a mixture without physical separation. This approach represented a significant advancement over traditional methods that required purification before measurement.

The fundamental challenge addressed was that spectral signatures often overlap in complex mixtures. Through computerized analysis, researchers could deconvolute these overlapping signals by applying multivariate regression techniques to extract individual component concentrations. This methodology was particularly valuable for pharmaceutical analysis, where researchers needed to quantify multiple active ingredients or detect impurities without lengthy separation procedures.

The logical relationship between the experimental challenge and computational solution is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Early Multivariate Spectroscopy

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Multivariate Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | High-purity compounds with known properties | Create calibration models for multivariate regression |

| Diffraction Gratings | Disperse light into constituent wavelengths | Generate high-resolution spectra for pattern recognition |

| Photomultiplier Tubes | Detect low-intensity light signals | Convert spectral information to electrical signals for digitization |

| Analog-to-Digital Converters | Transform analog signals to digital values | Enable computer processing of spectral data |

| Punched Cards/Paper Tape | Store digital data and programs | Input spectral data and analysis routines into mainframe computers |

| Matrix Algebra Software | Perform complex mathematical operations | Solve systems of equations for multi-component analysis |

| 2-Amino-3-chlorobutanoic acid | 2-Amino-3-chlorobutanoic acid, CAS:14561-56-9, MF:C4H8ClNO2, MW:137.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Osmium(4+);oxygen(2-) | Osmium(4+);oxygen(2-), CAS:12036-02-1, MF:O2Os, MW:222.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Birth of Chemometrics: From Practice to Discipline

The methodological and technological advances of the 1960s culminated in the early 1970s with the formal establishment of chemometrics as a distinct chemical discipline. In 1972, Svante Wold and Bruce R. Kowalski introduced the term "chemometrics," with the International Chemometrics Society being founded in 1974 [7]. This formal recognition was a direct outgrowth of the work begun in the previous decade, as the field coalesced around two primary objectives: "to design or select optimal measurement procedures and experiments and to provide chemical information by analyzing chemical data" [7].

The computational advances from the 1970s that gave scientists broader access to computers were applied to the instrumental chemical data that had become increasingly complex throughout the 1960s [7]. As computing resources became "more accessible and cheaper," the chemometric approaches pioneered in the previous decade rapidly disseminated through the analytical chemistry community [7]. This led to exponential growth in chemometrics applications, particularly as researchers gained the ability to handle "a large data amount" and perform "advanced calculations" [7]. The 1960s had provided both the instrumental capabilities and the conceptual framework; the 1970s supplied the computational infrastructure needed to establish chemometrics as a transformative discipline within analytical chemistry.

The 1960s served as the true catalyst for the computerized revolution in spectroscopic analysis, creating the essential foundation for modern chemometrics. This decade witnessed the critical transition from univariate to multivariate thinking in analytical chemistry, supported by the emergence of computerized instruments capable of handling complex data sets. The pioneering work of this period established the conceptual and methodological frameworks that would enable researchers to extract meaningful chemical information from intricate spectroscopic data.

The legacy of this transformative decade extends throughout modern analytical science. Today's sophisticated chemometric techniques—including principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares (PLS) regression, and multivariate curve resolution (MCR)—all trace their origins to the fundamental realignment that occurred during the 1960s [7]. The pioneering researchers who first paired spectroscopic instruments with computational analysis opened a new frontier in chemical measurement, creating a paradigm where complex multivariate relationships could be not merely observed but quantitatively modeled and understood. This foundation continues to support advances across analytical chemistry, from pharmaceutical development to materials science, demonstrating the enduring impact of this critical period in the history of chemical instrumentation.

The field of analytical chemistry underwent a profound transformation in the late 20th century, driven by the increasing computerization of laboratory instruments and the consequent generation of complex, multivariate datasets. Within this context, chemometrics emerged as a new scientific discipline, formally establishing itself as the chemical equivalent of biometry and econometrics. This field dedicated itself to developing and applying mathematical and statistical methods to extract meaningful chemical information from intricate instrumental measurements [14] [15]. While the term "chemometrics" had been used in Europe in the mid-1960s and appeared in a 1971 grant application by Svante Wold, it was the transatlantic partnership between Wold and Bruce R. Kowalski that truly institutionalized the field, providing it with a foundational philosophy, a collaborative society, and dedicated communication channels [14] [15]. The rise of techniques like optical spectroscopy, which produced rich but complex spectral data, created the perfect environment for chemometrics to demonstrate its power, ultimately reshaping the landscape of modern analytical chemistry for both academia and industry [14].

The Founding Figures and Institutionalization of a Discipline

Bruce R. Kowalski: The Maverick Mind

Bruce R. Kowalski (1942–2012) possessed an academic background that uniquely predisposed him to a cross-disciplinary approach. His double major in chemistry and mathematics at Millikin University was an unusual combination at the time, yet it perfectly foreshadowed his life's work [14]. After earning his PhD in chemistry from the University of Washington in 1969 and working in industrial and government research, he moved to an academic career, first at Colorado State University and then at the University of Washington where he became a full professor in 1979 [14]. His early research at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory with Charles F. Bender on PATTRN, a proprietary pattern recognition system for chemical data, planted the seeds for what would become chemometrics [14]. Kowalski was not only a prolific scientist with over 230 publications but also a dedicated mentor who advised 32 PhD students, ensuring his philosophies would be carried forward by future generations [14]. Former student David Duewer noted that Kowalski "wasn't just a prolific scientist; he was a mentor who changed lives," highlighting his contagious enthusiasm and unwavering support for his students and collaborators [14].

Svante Wold: The European Counterpart

Svante Wold served as the European pillar in the foundation of chemometrics. While specific biographical details in the search results are limited, it is documented that he coined the term "chemometrics" in a 1971 grant application [14] [15]. More importantly, his meeting with Kowalski in Tucson in 1973 ignited a powerful transatlantic partnership that would rapidly advance the formalization of the field [14]. Wold's contributions, particularly in multivariate analysis methods like partial least squares (PLS) regression, became cornerstones of the chemometrics toolkit [15].

Forging a Discipline: Key Institutional Milestones

The partnership between Wold and Kowalski quickly moved from theoretical discussion to concrete institution-building. Together, they established the fundamental structures needed to nurture a nascent scientific community.

Table: Foundational Institutions in Chemometrics

| Institution | Year Established | Founders | Primary Role and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemometrics Society | June 10, 1974 | Svante Wold and Bruce Kowalski | Created an initial community for researchers interested in combining chemistry with mathematics and statistics, reducing their isolation [14]. |

| Journal of Chemometrics | 1987 | Bruce Kowalski (founding editor) | Provided a consolidated, high-profile forum for research that was previously scattered throughout the literature [14]. |

| Center for Process Analytical Chemistry (CPAC) | 1984 | Bruce Kowalski and Jim Callis | An NSF Industry-University Cooperative Research Center that became a global model for interdisciplinary collaboration between academia and industry [14]. |

The philosophical stance of the new field was articulated clearly in Kowalski's 1975 landmark paper, "Chemometrics: Views and Propositions," where he defined chemometrics as "any and all methods that can be used to extract useful chemical information from raw data" [14]. This was a paradigm shift that positioned statistical modeling and data interpretation as being equally vital to analytical chemistry as instrumentation and wet chemistry [14]. The joint statement from Wold and Kowalski to prospective chemometricians emphasized that the field should prioritize real-world data interpretation over theoretical abstraction, a declaration of practical scientific utility that resonated across both academia and industry [14].

The Technical Framework: Core Concepts and Methodologies

The emergence of chemometrics was a direct response to the limitations of classical univariate analysis when faced with the complex data generated by modern spectroscopic instruments.

The Limitation of Classical Methods and the Need for Multivariate Analysis

For much of the 20th century, quantitative spectroscopy relied on univariate calibration curves (or working curves), where the concentration of a single analyte was correlated with a spectroscopic measurement (e.g., absorbance) at a single wavelength [15]. This approach, based on the Beer-Lambert law, was only effective for simple mixtures where spectral signals did not overlap [15]. However, for complex samples—such as biological fluids, pharmaceutical tablets, or environmental samples—spectral signatures inevitably overlapped, making it impossible to quantify individual components using a single wavelength. This limitation created an urgent need for mathematical techniques that could handle multiple variables simultaneously.

Foundational Chemometric Methods

Chemometrics provided a solution through multivariate analysis, which considers entire spectral regions or multiple sensor readings to build predictive models.

Table: Core Chemometric Techniques for Spectral Analysis

| Method | Primary Function | Key Application in Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Calibration | Relates multivariate instrument response (e.g., a full spectrum) to chemical or physical properties of a sample [15]. | Enables quantitative analysis of multiple analytes in complex mixtures where spectral bands overlap. |

| Pattern Recognition (PR) | Identifies inherent patterns, clusters, or classes within multivariate data [14]. | Used for classification of samples (e.g., authentic vs. counterfeit drugs, origin of food products) based on their spectral fingerprints. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Reduces the dimensionality of a dataset while preserving most of the variance, transforming original variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components [15]. | An exploratory tool to visualize data structure, identify outliers, and understand the main sources of variation in spectral datasets. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression | Finds a linear model by projecting the predicted variables (e.g., concentrations) and the observable variables (e.g., spectral intensities) to a new, lower-dimensional space [15]. | The most widely used method for building robust quantitative calibration models from spectral data, especially when the number of variables (wavelengths) exceeds the number of samples. |

Kowalski's early work was deeply involved with pattern recognition, as evidenced by his collaboration on the PATTRN system and his 1972 paper with Bender titled "Pattern recognition. A powerful approach to interpreting chemical data" [14]. This work was considered by Svante Wold to be a seminal contribution to analytical chemistry [14]. Furthermore, Kowalski and his collaborators made significant advances in multiway analysis, including methods like Direct Trilinear Decomposition (DTLD) and Tensorial Calibration [14]. These techniques are crucial for analyzing complex data with three or more dimensions (e.g., from excitation-emission fluorescence spectroscopy), preserving the natural structure of the data for more accurate and interpretable results [14].

The Net Analyte Signal Concept

Kowalski, in collaboration with Karl Booksh, Avraham Lorber, and others, also advanced the theory of the Net Analyte Signal (NAS) [14]. The NAS represents the portion of a measured signal that is uniquely attributable to the analyte of interest, excluding contributions from other interfering components. This concept is critical for calculating key figures of merit in calibration models, such as selectivity and sensitivity [14]. A key innovation was demonstrating that NAS could be computed not only using traditional direct calibration models but also with more practical inverse calibration models (like PLS), which broadened its applicability to real-world scenarios like determining protein content in wheat using near-infrared spectroscopy [14].

Experimental Protocols: A Workflow for Spectral Analysis

The application of chemometrics to optical spectroscopy follows a systematic workflow that transforms raw spectral data into actionable chemical knowledge. The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for developing a multivariate calibration model, such as for quantifying an active ingredient in a pharmaceutical tablet using Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy.

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

- Reference Sample Set: Prepare a carefully designed set of calibration samples that encompass the expected natural variation in the chemical and physical properties of interest (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) concentration, excipient ratios, moisture content) [15].

- Reference Analysis: Determine the "true" concentration or property value for each calibration sample using a validated primary reference method (e.g., HPLC for API concentration). The quality of the chemometric model is critically dependent on the accuracy of this reference data [15].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect spectra for all calibration samples using a well-calibrated spectrophotometer. Ensure consistent instrumental conditions (e.g., resolution, number of scans, temperature) and sample presentation (e.g., particle size for powders, pathlength for liquids) throughout the measurement process [15].

Data Preprocessing and Model Development

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply mathematical treatments to the raw spectra to remove or minimize non-chemical sources of variance, thereby enhancing the relevant chemical information.

- Common Techniques: Savitzky-Golay smoothing (to reduce high-frequency noise), Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) (to correct for light scattering effects in powders), and derivatives (to resolve overlapping peaks and remove baseline drift) [15].

- Model Calibration: Use the preprocessed spectra (

X-matrix) and the reference values (Y-matrix) to build a calibration model.- For a PLS regression, the algorithm projects both the spectral data and the concentration data into a new latent variable space, maximizing the covariance between

XandY[15]. - The optimal complexity of the model (e.g., the number of latent variables in PLS) must be determined to avoid underfitting or overfitting.

- For a PLS regression, the algorithm projects both the spectral data and the concentration data into a new latent variable space, maximizing the covariance between

- Model Validation: Assess the predictive ability and robustness of the calibrated model using an independent set of validation samples not used in the calibration step.

- Key Validation Metrics: Calculate the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and the coefficient of determination (R²) between the predicted values and the reference values. A robust model will have a low RMSEP and a high R² [15].

The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage experimental workflow, from sample preparation to a validated predictive model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The practical application of chemometrics in spectroscopic research and development relies on a combination of specialized software, reference materials, and instrumental components.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemometric Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Role in Chemometrics |

|---|---|---|

| Chemometrics Software | • PLS_Toolbox (Eigenvector Research)• The Unscrambler• MATLAB with in-house scripts | Provides the computational engine for implementing multivariate algorithms (PCA, PLS, etc.), data preprocessing, and model visualization [14] [16]. |

| Reference Materials | • Certified calibration standards• Validation sets with known reference values | Serves as the ground truth for building and validating calibration models. The accuracy of these materials directly determines model performance [15]. |

| Spectrophotometer | • NIR, IR, Raman, or UV-Vis spectrometer | The primary data generator. Must be stable and well-characterized to produce high-quality, reproducible spectral data for modeling [14] [15]. |

| Sample Presentation Accessories | • Liquid transmission cells• Fiber optic probes• Powder sample cups | Ensures consistent and representative interaction between the sample and the light beam, minimizing unwanted physical variation in the spectra [15]. |

| Allyl phenethyl ether | Allyl phenethyl ether | High-Purity Reagent | Allyl phenethyl ether for research applications. A versatile chemical for organic synthesis and fragrance R&D. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| (1-Butyloctyl)cyclohexane | (1-Butyloctyl)cyclohexane|High-Purity Reference Standard |

The creation of accessible software was a cornerstone of Kowalski's vision for chemometrics. He co-founded Infometrix in 1978 with Gerald Erickson, a company dedicated to bringing advanced data analysis tools directly to practicing chemists [14]. Furthermore, the work of Kowalski and his students using MATLAB laid the groundwork for Barry Wise and Neal Gallagher to create Eigenvector Research, Inc. in 1995, which remains a leading developer of chemometrics software today [14].

The formalization of chemometrics by Svante Wold and Bruce Kowalski represented a genuine paradigm shift in analytical chemistry. It moved the discipline's focus beyond mere instrumental measurement to the sophisticated extraction of meaning from complex data [14] [15]. Kowalski himself framed this as a new intellectual framework for problem-solving, where mathematics functions not just as a modeling tool but as an investigative "data microscope" to explore and uncover hidden relationships [15].

The legacy of these founding fathers is profound. The methodologies they championed have become so pervasive in spectroscopy and other analytical techniques that quantifying their full impact is challenging [16]. From enabling real-time process analytical chemistry in pharmaceutical manufacturing to facilitating the analysis of complex biological systems, the principles of chemometrics continue to underpin modern chemical analysis. As the field continues to evolve with the rise of machine learning and artificial intelligence, the foundational work of Wold and Kowalski in establishing a rigorous, data-centric philosophy ensures that chemometrics will remain essential for transforming raw data into chemical knowledge for the foreseeable future [15].

The field of optical spectroscopy is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional, often rigid analytical approaches toward a dynamic, data-driven paradigm. This shift represents a fundamental change in how researchers extract chemical information from spectroscopic data. Chemometrics, classically defined as the mathematical extraction of relevant chemical information from measured analytical data, has evolved from relying primarily on established methods like principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares (PLS) regression to incorporating advanced artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) frameworks [17]. This evolution enables automated feature extraction, nonlinear calibration, and the analysis of increasingly complex datasets that were previously intractable. The integration of these technologies transforms the spectroscopist's toolkit from a set of predetermined rituals into a powerful "data microscope" capable of revealing hidden patterns, relationships, and anomalies with unprecedented clarity and depth. This paradigm shift is particularly impactful in drug development and materials science, where the ability to perform robust exploratory analysis on complex spectroscopic data accelerates discovery and enhances analytical precision.

Core Methodologies: From Classical to AI-Enhanced Chemometrics

The foundation of modern exploratory analysis in spectroscopy is built upon a progression of mathematical techniques, from classical multivariate methods to contemporary machine learning algorithms.

Classical Multivariate Methods

Classical methods form the essential backbone of chemometric analysis, providing interpretable and reliable results for a wide range of applications. These methods are particularly valuable for establishing baseline models and for situations where model interpretability is paramount.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised technique that identifies the dominant patterns in spectral data by projecting it onto a new set of orthogonal axes (principal components) that maximize variance. It is predominantly used for exploratory data analysis, outlier detection, and visualizing sample clustering [17].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression: A supervised method that projects both predictor variables (spectral intensities) and response variables (e.g., concentration) to new latent variables, maximizing the covariance between them. It is the workhorse for quantitative calibration models in spectroscopy [17] [18].

- Classical Least Squares (CLS): Based on the direct application of Beer's law, CLS assumes that the absorbance spectrum of a mixture is a linear combination of the pure component spectra. It is foundational for understanding multivariate calibration but can be sensitive to spectral artifacts [18].

Modern Machine Learning and AI Frameworks

The advent of AI has dramatically expanded the capabilities of chemometrics, introducing algorithms that can handle nonlinear relationships and automate feature discovery.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): Effective for both classification and regression (SVR), SVMs find the optimal boundary or function that separates classes or predicts values in a high-dimensional space. Their use of kernel functions makes them powerful for tackling nonlinear problems in spectroscopic data [17].

- Random Forest (RF): An ensemble method that constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their results. RF is highly robust against overfitting and spectral noise, and it provides feature importance rankings that help identify diagnostically significant wavelengths [17].

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): A advanced boosting algorithm that builds trees sequentially, with each new tree correcting the errors of the previous ones. XGBoost often delivers state-of-the-art performance for complex, nonlinear tasks like pharmaceutical composition analysis [17].

- Neural Networks (NN) and Deep Learning: These models, particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), can automatically learn hierarchical features from raw or minimally preprocessed spectral data. They excel at pattern recognition but typically require large datasets and tools for interpretability [17]. Bayesian Deep Learning represents a further advancement, providing principled uncertainty estimates alongside predictions, which is crucial for assessing model reliability in exploratory contexts [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Chemometric Methodologies for Spectroscopic Data

| Method | Type | Primary Use | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Unsupervised | Exploration, Dimensionality Reduction | Simple, interpretable, no labeled data required | Purely descriptive, no predictive capability |

| PLS | Supervised | Quantitative Calibration | Handles correlated variables, robust for linear systems | Assumes linearity, performance degrades with strong nonlinearities |

| SVM/SVR | Supervised | Classification, Regression | Effective in high dimensions, handles nonlinearity via kernels | Performance sensitive to parameter tuning |

| Random Forest | Supervised | Classification, Regression | Robust to noise, provides feature importance | Less interpretable than single decision trees |

| XGBoost | Supervised | Classification, Regression | High predictive accuracy, handles complex nonlinearities | Model can be complex and less transparent |

| Neural Networks | Supervised | Classification, Regression, Feature Extraction | Automates feature engineering, models complex nonlinearities | High computational cost, requires large data, "black box" nature |

Experimental Protocol: A Practical Workflow for Robust Analysis

Implementing a successful exploratory analysis requires a structured workflow. The following protocol, adaptable for various spectroscopic techniques (NIR, IR, Raman), details the steps from data collection to model deployment, using a real-world example of analyzing a three-component system (e.g., benzene, polystyrene, gasoline) [18].

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Sample Preparation & Spectral Acquisition: Assemble a training set of samples with known composition (e.g., 20 samples with varying concentrations of the three constituents). Collect absorbance or reflectance spectra across a defined wavelength range using an appropriate spectrometer [18].

- Data Formatting and Organization: Ensure spectral data is structured in a consistent matrix format, where rows represent individual spectra and columns represent intensities at specific wavelengths or wavenumbers. This structured format is crucial for subsequent matrix operations [18].

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply necessary preprocessing techniques to mitigate physical artifacts and enhance chemical information. Common steps include:

- Scatter Correction: Using Multiplicative Signal Correction (MSC) or Standard Normal Variate (SNV).

- Derivatization: Applying Savitzky-Golay derivatives to remove baseline offsets and enhance spectral resolution.

- Normalization: Scaling spectra to a standard unit to account for path length or concentration effects.

Model Building and Validation

- Data Splitting: Divide the preprocessed dataset into a training set (e.g., 20 spectra) for building the model and a separate validation set (e.g., 12 real-world samples) for evaluating its predictive performance on unknown data [18].

- Descriptor/Feature Calculation (Optional for AI models): For advanced AI models like ARISE, which is used for crystal structure identification, the input data (atomic coordinates, chemical species) is converted into a suitable descriptor such as the Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP). This step creates a vector representation that is invariant to physical symmetries like rotation and translation, which is key for robust pattern recognition [19].

- Algorithm Selection and Training: Choose one or more algorithms from Section 2 based on the analysis goal (e.g., PLS for quantification, RF for classification). Train the model using the training set. For Bayesian Deep Learning models, this involves using stochastic regularization techniques like dropout to enable uncertainty estimation [19].

- Model Validation and Interpretation: Use the validation set to assess model performance. For quantitative models, calculate metrics like Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP). For classification, use a confusion matrix. Utilize tools like feature importance (RF) or explainable AI (XAI) frameworks (for DNNs) to interpret which spectral regions drive the predictions, ensuring chemical interpretability [17].

Diagram 1: Chemometric Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The modern chemometrics workflow relies on a combination of software tools, computational libraries, and color-accessible visualization palettes to ensure reproducible and insightful analysis.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Modern Chemometric Analysis

| Tool/Resource Category | Example | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments & Toolboxes | MATLAB with PNNL Chemometric Toolbox [18] | Provides a structured environment and pre-built scripts for implementing classic methods like CLS, PCR, and PLS on spectroscopic data. |

| AI/ML Code Libraries | ai4materials [19] | A specialized code library designed for materials science, allowing for the integration of advanced descriptors and AI models like Bayesian NNs. |

| Colorblind-Friendly Palettes (Qualitative) | Tableau Colorblind-Friendly [20], Paul Tol Schemes [21] | Pre-designed color sets (e.g., blue/orange) that ensure data points and lines are distinguishable by all users, critical for inclusive science. |

| Colorblind-Friendly Palettes (Sequential/Diverging) | ColorBrewer [21] | An interactive tool for selecting palettes suitable for heatmaps and other visualizations of continuous data, with options for colorblind safety. |

| Color Simulation Tools | Color Oracle [21], NoCoffee Chrome Plugin [20] | Software that simulates various forms of color vision deficiency (CVD) on the screen, allowing for real-time checking of visualizations. |

| Advanced Descriptors | Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [19] | A powerful descriptor that converts atomic structures into a rotation-invariant vector representation, enabling robust structural recognition and comparison. |

| Aconitic acid, triallyl ester | Aconitic acid, triallyl ester, CAS:13675-27-9, MF:C15H18O6, MW:294.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dehydroabietal | Dehydroabietal | High-Purity Compound for Research | Dehydroabietal for research applications. High-purity, For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Visualization and Accessibility: Designing for Inclusive Science

Effective communication of analytical results is a cornerstone of the data microscope paradigm. Adhering to accessibility guidelines ensures that findings are interpretable by the entire scientific community, including the 8% of men and 0.5% of women with color vision deficiency (CVD) [20] [21].

Core Principles for Accessible Visualizations

- Avoid Exclusive Reliance on Problematic Color Combinations: The most common rule—"don't use red and green together"—is an oversimplification. The problem extends to combinations of red, green, brown, and orange, as well as blue/purple and pink/gray, which can appear identical to individuals with different types of CVD [20].

- Leverage Colorblind-Friendly Palettes: Utilize palettes designed for accessibility, such as the built-in scheme in Tableau or those provided by Paul Tol. These often use color pairs like blue/orange, blue/red, or blue/brown, which remain distinguishable under common CVD conditions [20] [21].

- Use Multiple Visual Encodings: When color must be used in a potentially problematic way, supplement it with other encodings. For line charts, use dashed lines, different line widths, or direct data labels. For scatter plots, use different shapes or icons. This ensures the data is decipherable even if the color is not [22] [21].

- Exploit Lightness (Value) Contrast: If using red and green is mandatory, ensure they differ significantly in lightness (e.g., a light green and a dark red). This creates a sequential-like appearance in grayscale, allowing differentiation based on light vs. dark [20].

Diagram 2: Accessible Visualization Principles

The integration of advanced AI and ML frameworks with classical chemometric principles has fundamentally transformed optical spectroscopy from a discipline reliant on established rituals to one empowered by a dynamic, exploratory "data microscope." This paradigm shift, rooted in the origins of chemometrics as a means to extract chemical information from complex data, enables researchers and drug development professionals to move beyond simple quantification. They can now uncover non-apparent structural regions, quantify prediction uncertainty, and perform robust analysis on noisy experimental data [19]. By adopting the structured methodologies, experimental protocols, and accessible visualization practices outlined in this guide, scientists can fully leverage this new paradigm, accelerating discovery and ensuring their insights are robust, interpretable, and inclusive.

Beyond Beer's Law: Core Chemometric Algorithms and Their Spectroscopic Applications

The field of chemometrics, which applies mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data, finds its origins in the fundamental principles of optical spectroscopy. At the heart of this relationship lies the Beer-Lambert Law, a cornerstone of spectroscopic analysis that establishes a linear relationship between the concentration of an analyte and its light absorption. This law provides the theoretical justification for Classical Least Squares (CLS), a foundational chemometric technique for quantitative multicomponent analysis. The development of these tools is deeply intertwined with the history of spectroscopy itself, which began with Isaac Newton's use of a prism to disperse sunlight and his subsequent coining of the term "spectrum" in the 17th century [9] [8]. The 19th century brought pivotal advancements from scientists like Bunsen and Kirchhoff, who established that each element possesses a unique spectral fingerprint, thereby laying the groundwork for spectrochemical analysis [9]. The mathematical underpinning of CLS, the least squares method, was formally published by Legendre in 1805 and later connected to probability theory by Gauss, cementing its status as a powerful tool for extracting meaningful information from experimental data [23]. This whitepaper explores the synergistic relationship between the Beer-Lambert Law and CLS, detailing their role as the foundational tool for quantitative analysis in modern spectroscopic applications, particularly in pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundations

The Beer-Lambert Law: Principles and Limitations

The Beer-Lambert Law describes the attenuation of light as it passes through an absorbing medium. It provides the fundamental linear relationship that enables quantitative concentration measurements in spectroscopy [24] [25].

Mathematical Formulation

The law is formally expressed as: [ A = \epsilon \cdot c \cdot l ] Where:

- ( A ) is the absorbance (a dimensionless quantity)

- ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity (or molar extinction coefficient) in L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹

- ( c ) is the concentration of the absorbing species in mol/L

- ( l ) is the path length of light through the sample in cm [25] [26]

Absorbance is defined logarithmically in terms of light intensities: [ A = \log{10} \left( \dfrac{Io}{I} \right) ] Where ( I_o ) is the incident light intensity and ( I ) is the transmitted light intensity [24] [25].

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Despite its widespread utility, the Beer-Lambert Law has important limitations that analysts must consider:

- Deviations at High Concentrations: At high concentrations (typically >10 mM), electrostatic interactions between molecules can lead to non-linear behavior, invalidating the direct proportionality between absorbance and concentration [26].

- Chemical and Environmental Effects: Changes in pH, solvent composition, temperature, and the presence of interfering species can alter molar absorptivity, leading to inaccurate concentration measurements [26].

- Instrumental Limitations: Stray light, inadequate spectral bandwidth, and fluorescence can cause significant deviations from ideal Beer-Lambert behavior [24] [25].

Classical Least Squares (CLS) Theory

Classical Least Squares is a multivariate calibration method that extends the Beer-Lambert Law to mixtures containing multiple absorbing components. The CLS model assumes that the total absorbance at any wavelength is the sum of absorbances from all contributing species in the mixture [27].

Mathematical Framework of CLS

For a multicomponent system, the absorbance at wavelength ( i ) is given by: [ Ai = \sum{j=1}^n \epsilon{ij} \cdot cj \cdot l + e_i ] Where:

- ( A_i ) is the total absorbance at wavelength ( i )

- ( \epsilon_{ij} ) is the molar absorptivity of component ( j ) at wavelength ( i )

- ( c_j ) is the concentration of component ( j )

- ( l ) is the path length (typically constant and thus often incorporated into ( \epsilon ))

- ( e_i ) is the residual error at wavelength ( i )

In matrix notation for all wavelengths and samples: [ \mathbf{A} = \mathbf{C} \mathbf{K} + \mathbf{E} ] Where:

- ( \mathbf{A} ) is the matrix of absorbance spectra

- ( \mathbf{C} ) is the matrix of concentrations

- ( \mathbf{K} ) is the matrix of absorption coefficients

- ( \mathbf{E} ) is the matrix of residuals [27]

The CLS solution minimizes the sum of squared residuals: [ \min \sum \mathbf{E}^2 ] The estimated calibration matrix ( \hat{\mathbf{K}} ) is obtained from: [ \hat{\mathbf{K}} = (\mathbf{C}^T \mathbf{C})^{-1} \mathbf{C}^T \mathbf{A} ] For predicting concentrations in unknown samples: [ \mathbf{C}{unknown} = \mathbf{A}{unknown} \hat{\mathbf{K}}^T (\hat{\mathbf{K}} \hat{\mathbf{K}}^T)^{-1} ]

Experimental Protocols

CLS Calibration and Validation Protocol

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for developing and validating a CLS model for quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical compounds.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for CLS Analysis

| Item | Specifications | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Double-beam, 1 nm bandwidth or better | Measures absorbance spectra of samples and standards |

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm path length, matched pairs | Holds samples for consistent light path measurement |

| Analytical Balance | 0.1 mg precision | Precisely weighs standards for solution preparation |

| Volumetric Flasks | Class A, various sizes | Prepares standard solutions with precise volumes |

| Pure Analyte Standards | Pharmaceutical grade (>98% purity) | Provides known concentrations for calibration model |

| HPLC-grade Solvent | Spectroscopic grade, low UV absorbance | Dissolves analytes without interfering absorbance |

| pH Meter | ±0.01 pH accuracy | Monitors and controls solution pH when necessary |

| Syringe Filters | 0.45 μm nylon or PTFE | Removes particulates that could cause light scattering |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Standard Solution Preparation

- Prepare stock solutions of each pure analyte component at approximately 1000 μg/mL in appropriate solvent.

- Dilute stock solutions to prepare 15-20 calibration standards with concentrations spanning the expected range (typically 5-95% of maximum expected concentration).

- Ensure standards adequately represent all possible mixture ratios of the components.

- Record exact concentrations of all standards (independent variables for CLS model).

Step 2: Spectral Acquisition

- Zero the spectrophotometer with pure solvent in the reference cuvette.

- Collect absorbance spectra of all standard solutions across an appropriate wavelength range.

- Use a spectral resolution of at least 1 nm and collect a sufficient number of data points (≥5 points per peak width).

- Maintain constant instrumental parameters (slit width, scan rate, response time) throughout analysis.

- Replicate measurements (n=3) for each standard to assess measurement precision.

Step 3: Data Preprocessing

- Visually inspect all spectra for anomalies or instrumental artifacts.

- Apply necessary preprocessing: baseline correction, smoothing (if needed), and wavelength alignment.

- Arrange spectra into the absorbance matrix A (samples × wavelengths).

- Arrange known concentrations into the concentration matrix C (samples × components).

Step 4: Model Calibration

- Calculate the calibration matrix K using the CLS formula: ( \mathbf{K} = (\mathbf{C}^T \mathbf{C})^{-1} \mathbf{C}^T \mathbf{A} ).

- Verify matrix conditioning; if ( \mathbf{C}^T \mathbf{C} ) is ill-conditioned, use more standards or reduce component count.

- Store the calculated K matrix for future predictions.

Step 5: Model Validation

- Prepare an independent set of validation standards not used in calibration.

- Predict concentrations using the CLS model and compare with known values.

- Calculate figures of merit: Root Mean Square Error of Calibration (RMSEC), Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP), and correlation coefficients (R²).

- For pharmaceutical applications, ensure model meets ICH Q2(R1) validation guidelines for accuracy, precision, and linearity.

Advanced Protocol: Complex-Valued CLS for Non-Ideal Systems

For systems exhibiting significant deviations from Beer's Law due to molecular interactions or solvent effects, complex-valued CLS offers improved performance by incorporating the full complex refractive index [27] [28].

Complex Refractive Index Acquisition

- Theoretical Background: The complex refractive index is given by ( \hat{n} = n + ik ), where ( n ) is the real part (refractive index) related to dispersion, and ( k ) is the imaginary part (absorption index) related to absorption [27].

- Measurement Techniques:

- Use spectroscopic ellipsometry to directly measure both ( n ) and ( k ) spectra [27].

- Alternatively, derive the complex refractive index from conventional absorbance spectra using Kramers-Kronig transformations [27].

- For attenuated total reflection (ATR) measurements, apply advanced correction algorithms based on Fresnel's equations [27].

Complex-valued CLS Implementation

- Construct a complex-valued absorbance matrix ( \mathbf{\hat{A}} ) incorporating both real and imaginary components.

- Apply complex-valued CLS algorithm: ( \mathbf{\hat{C}} = \mathbf{\hat{A}} \mathbf{\hat{K}}^T (\mathbf{\hat{K}} \mathbf{\hat{K}}^T)^{-1} ), where ( \mathbf{\hat{K}} ) is the complex calibration matrix [28].

- Utilize the self-correction mechanism inherent in complex-valued CLS, which can reduce mean absolute error to approximately 26-46% compared to using only absorption spectra for certain binary mixtures [28].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

The combination of CLS and the Beer-Lambert Law provides powerful tools for drug development applications, from early discovery to quality control.

Drug Formulation Analysis

CLS enables simultaneous quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and degradation products in complex formulations without requiring physical separation. A typical application involves:

- Multicomponent Vitamin Analysis: Simultaneous determination of water-soluble vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B12, and C) in multivitamin formulations using UV-Vis spectroscopy and CLS calibration.

- Dissolution Testing Monitoring: Real-time quantification of API release during dissolution testing using fiber-optic UV-Vis probes and CLS models.

- Stability Testing: Tracking degradation product formation in accelerated stability studies by detecting spectral changes and quantifying components via CLS.

Biological Fluid Analysis

The principles of CLS find applications in therapeutic drug monitoring, though often requiring more advanced preprocessing to handle complex matrices:

- Protein Binding Studies: Monitoring drug-protein interactions by detecting spectral shifts and quantifying bound versus unbound drug fractions.

- Metabolite Kinetics: Tracking parent drug and metabolite concentrations in incubation studies for metabolic stability assessment.

Table 3: CLS Method Validation Parameters for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Validation Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Typical CLS Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | 98-102% | 99.5-101.5% |

| Precision (% RSD) | ≤2% | 0.3-1.5% |

| Linearity (R²) | ≥0.998 | 0.999-0.9999 |

| Range | 50-150% of target concentration | 20-200% for well-behaved systems |

| Limit of Detection | Signal-to-noise ≥3 | Component-dependent (typically 0.1-1% of range) |

| Robustness | %RSD ≤2% with variations | Method-dependent |

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Integration with Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

Modern implementations of CLS are evolving beyond traditional UV-Vis spectroscopy:

- Complex-Valued Chemometrics: Emerging approaches incorporate both real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index, preserving phase information and improving linearity with analyte concentration [27]. This is particularly valuable for systems exhibiting significant deviations from ideal Beer-Lambert behavior.

- Hyperspectral Imaging: CLS algorithms applied to hyperspectral imaging data enable spatial quantification of API distribution in solid dosage forms, providing critical quality attributes for process analytical technology (PAT).

- Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy: Combining CLS with 2D-COS enhances selectivity for analyzing overlapping peaks in complex mixtures like natural products or degradation mixtures.

Computational Enhancements

- Hybrid Machine Learning-CLS Models: Integration of CLS with artificial neural networks (ANNs) or support vector machines (SVMs) to handle non-linearities while maintaining interpretability.

- Real-Time Process Monitoring: Implementation of CLS in embedded systems for continuous manufacturing, enabled by efficient matrix computation algorithms and miniaturized spectrometers.

- Advanced Preprocessing Algorithms: Development of digital filters and chemometric methods that automatically correct for light scattering, baseline drift, and other interferences before CLS application.

The synergy between the Beer-Lambert Law and Classical Least Squares represents a foundational paradigm in analytical chemistry, with profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development. From its historical origins in the earliest spectroscopic observations to its modern implementation in complex-valued chemometrics, this partnership continues to provide robust, interpretable methods for quantitative analysis. The physical principles embodied in the Beer-Lambert Law grant CLS a theoretical foundation lacking in many purely empirical chemometric techniques, while the mathematical framework of least squares enables precise multicomponent quantification even in complex matrices. For drug development professionals, mastery of these tools remains essential for efficient formulation development, rigorous quality control, and innovative research methodologies. As spectroscopic technologies advance toward higher dimensionality and faster acquisition, the core principles of CLS and the Beer-Lambert Law will continue to underpin new analytical methodologies, ensuring their relevance for future generations of scientists.

Modern optical spectroscopy, including techniques like Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman spectroscopy, generates complex, high-dimensional data crucial for pharmaceutical analysis. These techniques produce detailed spectral profiles containing a wealth of hidden chemical and physical information. However, the utility of this data hinges on the ability to extract meaningful insights from what is often a complex web of correlated variables. This challenge catalyzed the rise of chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data—with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression emerging as foundational tools for handling complexity.