How to Select a Comparative Method for Method Validation: A Strategic Guide for Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for researchers and drug development professionals to strategically select a comparative method for analytical method validation.

How to Select a Comparative Method for Method Validation: A Strategic Guide for Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for researchers and drug development professionals to strategically select a comparative method for analytical method validation. Covering foundational principles, regulatory requirements, and practical experimental design, it addresses common challenges and advanced optimization strategies. The guide synthesizes current regulatory expectations from FDA, EMA, and ICH guidelines with proven scientific approaches to ensure robust, defensible, and audit-ready validation outcomes that safeguard data integrity and product quality.

Understanding the Critical Role of a Comparative Method

Within the rigorous framework of analytical method validation, the process of method comparison serves a critical function: it estimates the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new (test) method by comparing its results to those from an established procedure [1]. The fundamental purpose of this experiment is to determine the agreement between methods measuring the same analyte, ensuring that patient results remain reliable and comparable when a new technique is introduced [2]. The selection of an appropriate method for this comparison—whether a reference method or a comparative method—is a pivotal decision that directly influences the interpretation of the data and the conclusions drawn about the test method's performance. This guide provides a detailed examination of these two cornerstone concepts, arming researchers and scientists with the knowledge needed to make informed choices in their method validation research.

Core Definitions and Hierarchical Relationship

The terms "reference method" and "comparative method" are not interchangeable; they occupy different tiers of a quality hierarchy based on their documented accuracy.

- Reference Method: A reference method carries a specific meaning, inferring a high-quality method whose results are known to be correct. This correctness is established through comparative studies with an accurate "definitive method" and/or through the traceability of standard reference materials [1]. In practice, when a test method is compared to a reference method, any observed differences are assigned to the test method. The documented correctness of the reference method provides a strong foundation for attributing error [1].

- Comparative Method: This is a more general term used for a method whose correctness has not been rigorously documented to the same standard. Most routine laboratory methods fall into this category. When large and medically unacceptable differences are found between a test method and a routine comparative method, it becomes necessary to conduct additional experiments, such as recovery and interference studies, to identify which method is inaccurate [1].

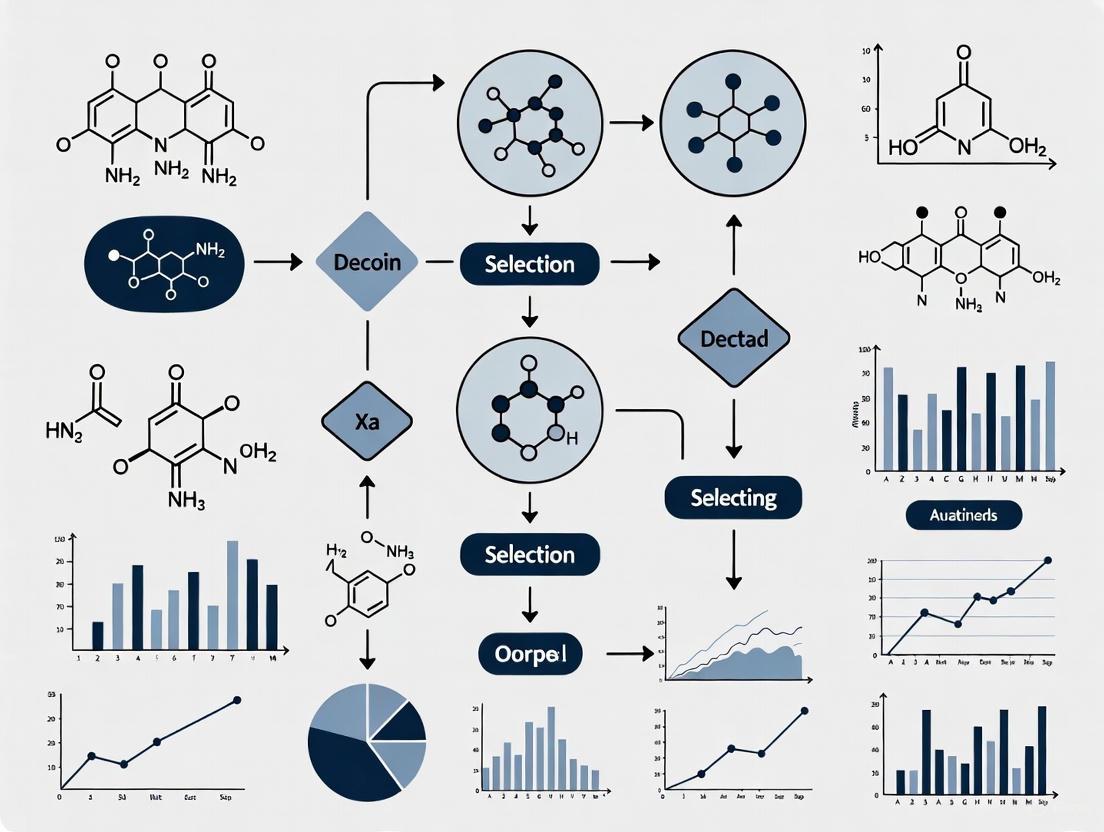

The relationship between these concepts, along with the associated level of confidence for error attribution, is illustrated in the following diagram.

Key Characteristics in a Comparative Table

The distinctions between a reference method and a comparative method extend beyond their basic definitions to encompass their foundational basis, the interpretation of results, and their typical applications. The table below provides a structured comparison of these key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Reference and Comparative Methods

| Characteristic | Reference Method | Comparative Method |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Definition | Well-documented correctness via definitive methods or traceable materials [1]. | General term for a method used in comparison; correctness not assumed [1]. |

| Primary Function | To provide an unquestioned benchmark for assessing a test method's inaccuracy [1]. | To assess the relative agreement between the new test method and a current, established method [3]. |

| Interpretation of Differences | Differences are conclusively attributed to the test method [1]. | Differences must be carefully interpreted; source of error (test or comparative method) is not known a priori [1]. |

| Typical Applications | Found in standardized, compendial settings (e.g., USP); used for definitive method validation [4]. | Used in routine laboratory practice for internal verifications, lot-to-lot reagent comparisons, and analyzer comparisons [2] [5]. |

| Regulatory & Quality Status | Often linked to a "gold standard" or a method that has undergone rigorous FDA review or collaborative trials [3]. | Represents the laboratory's current standard of practice, which may itself have been previously validated against a higher standard [1]. |

A Framework for Selecting a Comparison Method

Choosing between a reference method and a comparative method is not merely a technicality; it is a strategic decision that dictates the experimental design, data analysis, and ultimate conclusions of your validation study. The following workflow outlines the critical decision points and their consequences.

Guidance for Navigating the Selection Framework

Opt for a Reference Method When Possible: If a validated reference method is accessible and feasible for your laboratory to implement, it is the optimal choice. Its use provides the highest level of confidence in your systematic error estimates because the benchmark itself is unimpeachable. This path is strongly recommended for the initial validation of a novel method or when applying for regulatory approvals, as it offers the most defensible data [1] [3].

Using a Comparative Method Requires Rigor: When using a routine method for comparison, the focus shifts to demonstrating relative accuracy. A successful comparison shows that the new method agrees with the old one well enough for clinical purposes. However, the framework highlights a critical juncture: if differences are large, you must investigate further. You can no longer assume the new method is at fault; the discrepancy could originate from the comparative method itself [1]. Techniques like spiking studies (recovery) and interference testing are essential here to isolate the source of the error.

Essential Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

A well-defined experimental protocol is vital to ensure that the observed differences truly reflect analytical performance and are not artifacts of poor design. The following protocols and considerations are central to a robust comparison, whether you are using a reference or a comparative method.

Quantitative Method Comparison Protocol

For quantitative assays, such as those measuring an active pharmaceutical ingredient or a clinical metabolite, the comparison relies on analyzing a set of patient samples by both the test and comparative methods.

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for a Quantitative Comparison

| Parameter | Recommendation & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Number | Minimum of 40 patient specimens [1] [2]. To ensure a reliable estimate of systematic error. | Sample quality (covering the entire working range) is more important than a very large number. 20 carefully selected specimens can be better than 100 random ones [1]. |

| Sample Type & Range | Patient samples should cover the entire working range and represent the expected spectrum of diseases [1]. | At least 50% of samples should be outside the reference interval to validate performance at clinically decision-making concentrations [2]. |

| Time Period | A minimum of 5 different days is recommended [1]. | This minimizes bias from a single analytical run and incorporates normal day-to-day variation into the study [1]. |

| Measurements | Analyze each specimen in singlicate by both methods as common practice; duplicate measurements are advantageous [1]. | Duplicates act as a check for sample mix-ups, transposition errors, and other mistakes. Without duplicates, discrepant results should be reanalyzed immediately [1]. |

| Data Analysis | Graph the data (difference or comparison plots) and calculate appropriate statistics [1]. | Visual inspection identifies outliers. For wide analytical ranges, use linear regression to estimate systematic error (SE) at medical decision concentrations: ( Yc = a + bXc ), ( SE = Yc - Xc ) [1]. |

Qualitative Method Comparison Protocol

For qualitative tests (positive/negative results), the comparison is analyzed using a 2x2 contingency table to assess agreement relative to the comparative method [3].

Table 3: 2x2 Contingency Table for Qualitative Method Comparison

| Comparative Method: Positive | Comparative Method: Negative | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate Method: Positive | a (True Positive, TP) | b (False Positive, FP) | a + b |

| Candidate Method: Negative | c (False Negative, FN) | d (True Negative, TN) | c + d |

| Total | a + c | b + d | n (Total N) |

From this table, two primary metrics of agreement are calculated [3]:

- Positive Percent Agreement (PPA): = 100% × [a / (a + c)] - Indicates how well the candidate method detects positive samples relative to the comparator.

- Negative Percent Agreement (NPA): = 100% × [d / (b + d)] - Indicates how well the candidate method detects negative samples relative to the comparator.

It is critical to understand that PPA and NPA are estimates of sensitivity and specificity, respectively. These can only be reported as true sensitivity/specificity if the comparative method is a highly accurate "gold standard" or reference method. Otherwise, they remain measures of agreement [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The reliability of a method comparison is contingent on the quality and stability of the materials used. Below is a list of essential items and their functions in a typical comparison study.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function & Importance in Comparison Studies |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | A substance with one or more property values that are certified by a validated procedure, providing a metrological traceability link to a primary standard. Serves as the foundation for a reference method comparison [1]. |

| Patient Specimens | Naturally occurring matrices that account for real-world interferences and the spectrum of sample types. They are the preferred sample type for assessing systematic error with real clinical material [1] [2]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Stable materials with known expected values used to ensure that both the test and comparative methods are operating within acceptable performance limits before and during the comparison study [2]. |

| Appropriate Anticoagulants & Preservatives | Used in sample collection tubes to maintain specimen stability (e.g., prevent coagulation, slow metabolite degradation). Ensures that differences are analytical, not pre-analytical [1] [2]. |

| Fresh Mobile Phases / Reagents | Critical for chromatographic and enzymatic methods. Aged mobile phases must perform equivalently to fresh ones (e.g., within ±2% for response, resolution) to avoid introducing bias [4]. |

| Guibourtinidol | Guibourtinidol |

| Ethyl thiazol-2-ylglycinate | Ethyl thiazol-2-ylglycinate, MF:C7H10N2O2S, MW:186.23 g/mol |

The distinction between a reference method and a comparative method is fundamental to designing, executing, and interpreting a method validation study. A reference method provides an authoritative benchmark, allowing for definitive attribution of systematic error to the test method. In contrast, a comparative method serves as a practical standard for assessing relative agreement, but requires careful interpretation and potentially further investigation when discrepancies arise. The choice between them should be guided by availability, regulatory requirements, and the intended use of the test. By adhering to robust experimental protocols—including appropriate sample selection, replication, and statistical analysis—researchers can generate defensible data that ensures the reliability and fitness-for-purpose of new analytical methods in both drug development and clinical practice.

In pharmaceutical research and development, the choice of a comparative method is a foundational scientific and strategic decision that directly influences data integrity, product quality, and ultimately, regulatory success. A comparative method in method validation serves as a benchmark against which the performance, accuracy, and reliability of a new analytical procedure are measured. Within the current regulatory landscape, where data integrity is a paramount focus for agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the selection and execution of this method are more critical than ever [6]. Regulatory bodies have explicitly stated that data integrity issues are a primary reason for delays in application approvals, such as Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) [7].

The principles of ALCOA+, which mandate that data be Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate, along with being Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available, form the bedrock of regulatory expectations [8] [9]. The choice of an inappropriate, unvalidated, or poorly documented comparative method can directly undermine these principles, leading to data that is not trustworthy. Recent enforcement trends, including an increase in warning letters and the rejection of studies from contract research organizations (CROs) due to data integrity concerns, highlight the tangible risks of inadequate practices [10] [9]. This guide provides a detailed framework for researchers and scientists to select, validate, and document comparative methods that ensure data integrity and facilitate regulatory acceptance.

The Regulatory Landscape and Data Integrity Fundamentals

Regulatory agencies worldwide are intensifying their scrutiny of data governance practices. The FDA's 2025 focus areas include systemic quality culture, robust audit trails, and oversight of contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) [6]. Similarly, the EU's 2025 updates to EudraLex Volume 4, specifically the revised Annex 11 and Chapter 4, formally mandate ALCOA+ principles and emphasize data lifecycle management [6]. These updates represent a significant shift from viewing ALCOA+ as best practice to treating it as a mandatory requirement for compliance.

The consequences of data integrity failures are severe and multifaceted. A recent analysis of FDA Warning Letters revealed that violations related to data "Endurance" and "Availability" have been increasing post-pandemic [9]. Furthermore, the FDA has taken public action against CROs where data integrity concerns were identified, requiring sponsors to repeat essential studies and leading to changes in the therapeutic equivalence ratings of approved generic drugs [10]. This not only results in significant financial losses and delays but also damages an organization's credibility with regulators.

Table: Recent Regulatory Actions Stemming from Data Integrity Concerns

| Event | Regulatory Impact | Consequence for Sponsor |

|---|---|---|

| FDA Declaration on Raptim Research [10] | Certain bioequivalence studies deemed unacceptable due to data integrity concerns. | Must repeat essential in vitro studies; marketed products may receive a "BX" rating, indicating they are not recommended for automatic substitution. |

| Analysis of 1766 FDA Warning Letters (2016-2023) [9] | Increase in citations for "Endurance" (data remains available) and "Availability." | Regulatory actions (e.g., Warning Letters, Import Alerts), increased inspectional scrutiny, and application delays. |

| EU's 2025 Annex 11 Update [6] | Mandatory audit trails, identity & access management controls, and explicit management responsibility for data integrity. | Requires potentially expensive upgrades to older computerized systems and implementation of strengthened data governance frameworks. |

The selection of a comparative method is deeply intertwined with these data integrity requirements. The method must be fully validated itself, its operational lifecycle must be documented within a robust quality system, and the resulting data must be secured within a tamper-evident audit trail to meet contemporary regulatory standards [8] [6].

A Framework for Selecting a Comparative Method

Selecting a fit-for-purpose comparative method requires a structured, risk-based approach that aligns with the analytical procedure's intended use and regulatory context.

Core Principles for Selection

The following principles should guide the selection process:

- Scientific Justification: The chosen method must be scientifically sound and appropriate for the analyte and matrix. This requires a thorough understanding of the chemical, biological, and physical properties involved.

- Regulatory Precedence and Harmonization: Where possible, leverage methods described in recognized pharmacopoeias (USP, EP) or ICH guidelines. Be aware of potential variations in validation requirements across different regulatory bodies (ICH, EMA, WHO, ASEAN) as identified in comparative studies [11].

- ALCOA+ by Design: The method's workflow should be designed to inherently produce data that meets ALCOA+ principles. This includes using validated, access-controlled computerized systems that generate secure audit trails from the point of data creation [8] [6].

- Practical Feasibility: The method must be operable within the constraints of the laboratory's equipment, personnel expertise, and timeline, without compromising quality.

The Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for selecting a comparative method, integrating both scientific and data integrity considerations.

Key Selection Criteria

When evaluating candidate methods, a comparative assessment against defined criteria is essential. The table below outlines critical factors.

Table: Key Criteria for Comparative Method Selection

| Criterion | Description | Considerations for Data Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Scientific Robustness | The inherent reliability, accuracy, and precision of the method. | A robust method minimizes variability and the potential for "data cherry-picking" or manipulation to achieve desired results. |

| Regulatory Standing | The method's acceptance and history of use in regulatory submissions. | Well-established methods reduce regulatory uncertainty. Any deviation must be thoroughly justified and validated. |

| System Suitability | The ability to demonstrate that the system is operating as intended at the time of analysis. | Clear, predefined system suitability criteria are essential for ensuring the Original and Accurate nature of the data generated in a specific run [11]. |

| Automation & Control | The degree of automation and built-in electronic controls. | Automated systems with locked methods and integrated audit trails significantly enhance data Attributability and reduce transcription errors [6] [12]. |

| Validation Complexity | The extent and complexity of validation required. | The validation process for the comparative method itself must be meticulously documented to demonstrate the method is fit-for-purpose. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Method Validation

Once a comparative method is selected, its rigorous validation is imperative. The following protocols provide a detailed methodology for key experiments.

Protocol for a Comparative Accuracy Study

Objective: To demonstrate that the new method provides results that are statistically equivalent or superior to those obtained by the validated comparative method.

Materials and Reagents:

- Certified Reference Standards (with known purity and concentration)

- Placebo/formulation matrix (excluding the active ingredient)

- Test samples (e.g., drug product batches)

- All solvents and reagents as per the analytical procedures for both methods

Procedure:

- Preparation of Solutions: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations over a specified range (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target concentration) using the placebo matrix spiked with the reference standard. This should include three concentration levels, each analyzed in triplicate.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze these prepared solutions using both the new method and the comparative method in a randomized sequence to avoid bias.

- Data Collection: Record the raw data (e.g., peak areas, absorbance) directly into a compliant computerized system, ensuring all data is attributable and contemporaneous [8].

- Calculation and Comparison: For each level, calculate the recovery percentage and compare the results from both methods using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., student's t-test, equivalence testing).

Data Integrity Considerations:

- The sequence of analysis should be pre-defined in the protocol to ensure objectivity.

- All electronic data should be saved with associated audit trails; any manual data entries must be justified and witnessed per SOP [6].

Protocol for an Intermediate Precision Study

Objective: To evaluate the impact of random variations within the laboratory (different analysts, different days, different equipment) on the results of the comparative method itself.

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Two analysts (Analyst A and B) will perform the analysis on two different days (Day 1 and Day 2) using the same calibrated instrument where possible, or two different instruments of the same model.

- Sample Preparation: A homogeneous sample batch (e.g., at 100% concentration) is prepared and subdivided.

- Analysis: Each analyst prepares and analyzes six sample replicates on their respective days, following the same standardized method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the %Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) for the results from all analysts and all days combined.

Data Integrity Considerations:

- The system suitability tests must be met before each analytical run begins.

- The audit trail for the computerized system must be reviewed to confirm there were no unauthorized changes to the method or processing parameters between runs [8] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for executing robust comparative method validation studies.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Comparative Validation Studies

| Item | Function | Critical Quality Attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Serves as the primary benchmark for quantifying the analyte and establishing method accuracy. | Certified identity, purity, and stability; sourced from a qualified and reputable supplier (e.g., USP, EDQM). |

| Placebo/Blank Matrix | Allows for assessment of specificity and accuracy without interference from the active ingredient. | Must be truly representative of the final product formulation, excluding only the analyte of interest. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | Verifies that the chromatographic or analytical system is performing adequately at the time of the test. | Well-characterized mixture that provides consistent, predefined performance parameters (e.g., resolution, tailing factor). |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Used in mass spectrometric methods to correct for analyte loss during preparation and instrument variability. | High isotopic purity and chemical stability; must behave identically to the analyte but be distinguishable by the mass spectrometer. |

| Cinnolin-6-ylmethanol | Cinnolin-6-ylmethanol | Cinnolin-6-ylmethanol is For Research Use Only. Explore its applications in medicinal chemistry for developing antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Not for human use. |

| 1,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole | 1,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole|CAS 78787-77-6 | High-purity 1,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole for research. Explore its applications in anticancer studies and material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Visualizing the Data Lifecycle in a Regulated Environment

Ensuring data integrity requires control over the entire data lifecycle, from generation through to archival and destruction. The following diagram maps this lifecycle and its critical control points.

In the current regulatory climate, the choice of a comparative method is a critical decision with far-reaching implications for data integrity and regulatory acceptance. It is not merely a technical formality but a core component of a company's quality culture and data governance framework. By adopting a systematic, principle-based approach to selection, following rigorous and well-documented experimental protocols, and implementing robust controls throughout the data lifecycle, pharmaceutical researchers can generate data that is not only scientifically valid but also inherently trustworthy. This commitment to excellence in comparative method practices builds a solid foundation for regulatory confidence, smooths the path to approval, and, most importantly, ensures the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicines for patients.

In pharmaceutical development and healthcare research, demonstrating that an analytical method is reliable and fit for its intended purpose is a fundamental regulatory and scientific requirement. Method validation provides documented evidence that a process consistently produces a result meeting its predetermined specifications and quality attributes. Within a broader thesis on selecting a comparative method for validation research, this guide establishes that the core objectives are intrinsically linked: proving method reliability is a direct prerequisite for ensuring patient safety [13]. A method that is not reliable cannot accurately quantify product quality or detect potential patient risks, leading to inadequate safety diagnoses and the implementation of ineffective interventions [13]. This guide details the experimental protocols, data analysis frameworks, and essential tools required to achieve these twin objectives through a comparative method validation approach.

Foundational Principles and Experimental Design

Defining the Validation Framework

A robust method validation study begins with a clear experimental plan. The overarching goal is to demonstrate that the method's performance characteristics are acceptable for the intended application, thereby ensuring the safety and efficacy of the resulting data [14] [15]. The process involves a logical sequence of steps, from defining quality requirements to judging the acceptability of the method's performance [14]. The following workflow outlines the critical stages of method validation.

Implementing Design of Experiments (DOE)

A systematic approach using Design of Experiments (DOE) is a powerful tool for method characterization and validation [15]. DOE moves beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time studies, enabling a more efficient and accurate quantification of how factors influence method performance. The key steps in applying DOE are:

- Define the Purpose: Clearly state the goal of the study, such as assessing repeatability, intermediate precision, accuracy, linearity, or resolution [15].

- Define the Range: Establish the range of concentrations and the solution matrix the method will be used to measure. This defines the characterized "design space" [15].

- Perform a Risk Assessment: Identify all materials, equipment, analyst techniques, and method steps that may influence precision, accuracy, or other key responses. This risk assessment pinpoints where characterization is most needed [15].

- Design the Experimental Matrix: For a small number of factors (e.g., 2-3), a full factorial design may be suitable. For more factors, a D-optimal design can more efficiently explore the design space [15].

- Identify an Error Control Plan: Measure and record uncontrolled factors (e.g., analyst name, ambient temperature, hold times) during the study to account for their potential influence [15].

This structured approach ensures that the method is thoroughly understood and validated across a range of conditions, contributing directly to its reliability and, by extension, patient safety.

Key Performance Characteristics and Experimental Protocols

The following performance characteristics are typically assessed during method validation. The experiments must be designed to generate quantitative data that statistically proves the method's reliability.

Precision

Precision, the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements, is often broken down into repeatability and intermediate precision.

- Experimental Protocol: To determine repeatability, a minimum of 6 to 10 replicate measurements of a homogeneous sample at 100% of the test concentration should be performed. For intermediate precision, the same procedure is repeated on a different day, with a different analyst, or using different equipment [15]. The standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (RSD) are calculated from the results.

Accuracy

Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and a reference value, which is accepted as either a conventional true value or an accepted reference value.

- Experimental Protocol: Accuracy is typically established using a minimum of 9 determinations over a minimum of 3 concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., 3 concentrations, 3 replicates each). The sample matrix is spiked with a known quantity of the analyte, and the recovery is calculated as a percentage of the known added amount [15].

Linearity and Range

Linearity is the ability of the method to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte. The range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations for which linearity has been demonstrated.

- Experimental Protocol: A minimum of 5 concentrations are prepared and analyzed in duplicate [15]. The response is plotted against the concentration, and a linear regression model is fitted. The correlation coefficient (r), y-intercept, and slope are calculated.

The data from validation experiments should be summarized clearly for evaluation and comparison against acceptance criteria. The following table provides a template for presenting key validation parameters.

Table 1: Example Summary of Method Validation Results

| Performance Characteristic | Protocol Summary | Result | Acceptance Criterion | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (Recovery %) | 9 determinations at 3 levels (80%, 100%, 120%) | Mean Recovery = 99.5% | 98.0% - 102.0% | Pass |

| Repeatability (RSD %) | 10 replicates of 100% test concentration | RSD = 0.8% | NMT* 2.0% | Pass |

| Intermediate Precision (RSD %) | 10 replicates, different analyst & day | RSD = 1.2% | NMT 2.0% | Pass |

| Linearity (Correlation Coefficient) | 5 concentrations (50%-150%), duplicate | r = 0.999 | NLT* 0.998 | Pass |

NMT: No More Than; NLT: No Less Than

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of a method is dependent on the quality of the materials used. The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting a robust method validation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Item | Function / Purpose | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for determining accuracy and bias; used to calibrate the analytical procedure [15]. | High purity, well-characterized, and documented stability. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for method validation and quality control to verify accuracy; provides a known and traceable analyte concentration in a representative matrix. | Certified purity and concentration, supplied with a certificate of analysis, traceability to SI units. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Form the mobile phase, sample diluent, and reaction media; essential for achieving desired chromatography and detector response. | Appropriate grade (e.g., HPLC, GC), low UV absorbance, minimal particulate matter. |

| Stable, Well-Characterized Test Samples | The material on which the validated method will be performed; used for precision and robustness studies. | Representative of future test samples, homogeneous, and stable for the duration of the testing. |

| Cyclononanamine | Cyclononanamine, CAS:59577-26-3, MF:C9H19N, MW:141.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole | 2,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole|High-Purity Reference Standard | High-purity 2,6-Dimethyl-9H-carbazole for research. Explore its applications in medicinal chemistry and materials science. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Case Study: Validation of a Comparative In Vitro Test Method

A 2025 study on the calcification of bioprosthetic heart valves provides a robust example of a comparative method validation. The researchers developed an accelerated dynamic in vitro calcification test to replace expensive and time-consuming large animal studies for evaluating anti-calcification treatments [16].

- Objective: To validate a novel in vitro test method by comparing the calcification tendency of two differently pretreated groups of porcine heart valve bioprostheses.

- Experimental Protocol: Two groups (N=4 each) of aortic bioprostheses were subjected to accelerated dynamic in vitro calcification testing. Calcification was monitored using high-speed video documentation and microscopy [16].

- Comparative Analysis: The extent of calcification was quantified using multiple techniques: μ-CT for semi-destructive quantification and colorimetry/complexometry for destructive chemical quantification. The structural identity of the deposits was confirmed as "biological apatite" using X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), and the location within the valve structure was identified via von Kossa staining [16].

- Outcome and Reliability Link: The quantitative results showed a "distinctly stronger calcification tendency" for the non-pretreated group compared to the anti-calcifying pretreated group. The study confirmed the method's reliability by demonstrating that its quantitative results and structural findings were comparable with, and in line with, published in vivo observations [16]. This validated in vitro method provides a cost-effective and animal-saving tool, contributing to the safer development of more durable heart valves.

Proving method reliability through a structured, comparative validation strategy is not merely a regulatory formality; it is a critical component of patient safety. A method that has been rigorously tested for its precision, accuracy, and robustness under a range of conditions, as demonstrated through DOE and statistical analysis, generates trustworthy data. This reliable data forms the foundation for making correct decisions about drug product quality, clinical diagnostics, and medical device performance, ultimately ensuring that the products reaching patients are safe and effective. The frameworks, protocols, and tools outlined in this guide provide a pathway for researchers to achieve these core objectives, embedding reliability and safety into the very fabric of their analytical methods.

In the global pharmaceutical landscape, the validation of analytical methods is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a fundamental pillar of drug quality, safety, and efficacy. For researchers selecting a comparative method for validation studies, navigating the harmonized yet complex framework of international guidelines is paramount. The core of this framework is built upon the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guideline, which provides the foundational validation parameters. This is operationalized in the United States via FDA regulations (21 CFR Part 211) and USP General Chapter <1225>, and in the European Union via European Medicines Agency (EMA) adoption of ICH standards. A modernized, lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, reinforced by the simultaneous issuance of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14, moves beyond a one-time validation event to an integrated process of development, validation, and continuous improvement [17]. This guide provides a detailed roadmap for scientists to understand these requirements and strategically select a robust comparative method for their validation research.

The Regulatory Landscape and Key Guidelines

The integrity of analytical data is the bedrock of pharmaceutical quality control and regulatory submissions. A clear understanding of the roles and interrelationships of the major regulatory bodies and their guidelines is the first step in selecting an appropriate method.

International Council for Harmonisation (ICH): The ICH provides a harmonized framework to ensure global consistency in drug development and manufacturing. Its guidelines, once adopted by member regions, become the global gold standard, ensuring a method validated in one region is recognized worldwide. The primary guidelines for analytical procedures are ICH Q2(R2) on validation and ICH Q14 on procedure development [17].

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): As a key member of ICH, the FDA adopts and implements ICH guidelines. Compliance with ICH Q2(R2) is a direct path to meeting FDA requirements for submissions like New Drug Applications (NDAs) and Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). The FDA's own regulations, codified in 21 CFR Part 211, stipulate the Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) requirements for finished pharmaceuticals, which mandate that laboratory controls include the establishment of scientifically sound test methods [17] [18] [19].

European Medicines Agency (EMA): The EMA, representing the European Union, is another key regulatory member of ICH. It adopts ICH guidelines as scientific standards, meaning ICH Q2(R2) forms the basis for analytical procedure validation for marketing authorizations in the EU [20].

United States Pharmacopeia (USP): The USP publishes legally recognized standards for drugs and dietary supplements in the United States. USP General Chapter <1225> "Validation of Compendial Methods" provides detailed guidance on validating analytical procedures, harmonizing to the extent possible with ICH principles. Per CGMP regulations, users of USP methods are not required to fully validate them but must verify their suitability under actual conditions of use [21].

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between these key guidelines and the analytical procedure lifecycle:

Figure 1: The Interplay of Global Guidelines in the Analytical Lifecycle

Core Validation Parameters According to ICH Q2(R2) and USP

The selection of a comparative method must be justified by demonstrating that the method meets predefined performance characteristics. ICH Q2(R2) and USP <1225> define these core validation parameters, which form the critical criteria for your evaluation.

The table below summarizes the definitions and methodological approaches for establishing these key parameters, providing a clear framework for your validation studies.

Table 1: Core Analytical Procedure Validation Parameters and Their Determination

| Parameter | Definition | Common Methodological Approaches for Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [21] | The closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value. | For drug substances: Analyze a standard of known purity (e.g., USP Reference Standard). For drug products: Analyze synthetic mixtures or spike the placebo with known amounts of analyte. Assess using a minimum of 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels. |

| Precision [21] | The degree of scatter among repeated measurements from a homogeneous sample. | Repeatability: Multiple analyses by the same analyst, same equipment, short time. Intermediate Precision: Different days, different analysts, different equipment within the same lab. Reproducibility: Between different laboratories (collaborative studies). |

| Specificity [21] | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | For assays: Spike with impurities/excipients and demonstrate the assay is unaffected. For impurity tests: Spike with impurities and demonstrate they are determined with accuracy and precision. Use chromatographic peak purity tests (e.g., diode array, mass spectrometry). |

| Linearity [17] | The ability of a method to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration. | Analyze a series of samples with analyte concentrations across a specified range. Plot response vs. concentration and evaluate using statistical methods for linearity (e.g., correlation coefficient, y-intercept, slope). |

| Range [17] | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which linearity, accuracy, and precision have been demonstrated. | Established based on the intended use of the method, confirmed by the linearity and accuracy/precision data across the interval. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) [21] | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated. | Visual evaluation: Analyze samples with known low concentrations. Signal-to-noise: Compare measured signals from low concentration samples with blank samples (typically 2:1 or 3:1 ratio). |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) [21] | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitated with acceptable accuracy and precision. | Visual evaluation. Signal-to-noise (typically 10:1 ratio). Based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve. |

| Robustness [17] | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Deliberately vary parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, flow rate) and evaluate the impact on the analytical results. |

The Modernized Lifecycle Approach: ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14

The recent simultaneous issuance of ICH Q2(R2) and the new ICH Q14 guideline marks a significant evolution from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" validation model to a more scientific, lifecycle-based approach [17]. This shift is critical for researchers planning a long-term strategy for their analytical procedures.

From Validation to Lifecycle Management: Analytical procedure validation is no longer a one-time event conducted at the end of development. It is a continuous process that begins with method development and continues throughout the method's entire lifecycle, including post-approval changes [17].

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP): ICH Q14 introduces the ATP as a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and its required performance characteristics [17]. The ATP is the foundational document that should guide the selection and development of your comparative method. It proactively defines what the method needs to achieve, ensuring it is "fit-for-purpose" from the very beginning.

Enhanced vs. Minimal Approach: ICH Q14 describes two pathways for method development. The traditional, minimal approach is based on univariate experimentation. The enhanced approach encourages a more systematic, science- and risk-based development, often involving multivariate studies to understand the method's operational range thoroughly. While requiring more initial investment, the enhanced approach allows for more flexible and streamlined post-approval change management [17].

Inclusion of New Technologies: ICH Q2(R2) has been expanded to explicitly include guidance for modern techniques, such as multivariate analytical procedures, ensuring the guidelines remain relevant in an era of rapid technological advancement [17].

A Strategic Roadmap for Selecting and Validating a Comparative Method

For the researcher, the following step-by-step roadmap integrates the regulatory requirements into a practical workflow for selecting and validating a comparative method.

Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

Before any laboratory work begins, define the ATP. This is a crisp, quantitative statement of the method's requirements. What analyte is being measured? What is the expected concentration range? What level of accuracy and precision is required? The ATP sets the target for all subsequent activities [17].

Conduct a Risk Assessment

Employ quality risk management principles (ICH Q9) to identify potential variables that could impact method performance. Consider factors related to the sample (matrix effects, stability), the method (critical operational parameters), and the instrumentation. This risk assessment will directly inform the robustness studies in your validation plan and help define the method's control strategy [17].

Develop a Validation Protocol

Based on the ATP and risk assessment, create a detailed, prospective validation protocol. This protocol is the blueprint for your study and should explicitly define:

- The objective of the validation.

- The validation parameters to be tested (referencing Table 1).

- The detailed experimental design for each parameter.

- The predefined acceptance criteria for each parameter, derived from the ATP.

Execute Validation and Document Results

Execute the studies as outlined in the validation protocol. Meticulously document all raw data, results, and calculations. The results should be summarized and compared against the acceptance criteria. Any deviation must be investigated and justified.

Establish a Lifecycle Management Plan

Once the method is validated, maintain it under a state of control. Implement a system for change management to manage any future modifications in a structured manner. The enhanced knowledge from an ICH Q14-based development can facilitate a more science-based assessment of changes, potentially reducing regulatory reporting burdens [17].

The following workflow diagram encapsulates this strategic roadmap:

Figure 2: Strategic Roadmap for Method Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental to conducting the experiments described in the validation protocols. Sourcing high-quality materials from reputable suppliers is critical to generating reliable and defensible data.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Substance Reference Standard [22] [21] | Serves as the primary benchmark for establishing accuracy, linearity, and precision. Its certified purity and identity are essential for all quantitative measurements. | Preparation of calibration standards for assay and impurity methods. Used in accuracy/recovery studies. |

| Impurity and Degradation Product Standards [22] [21] | Used to validate specificity, LOD, LOQ, and accuracy for impurity tests. Demonstrates the method can separate and quantify known impurities. | Forced degradation studies (stress testing). Specificity and selectivity experiments. Establishing the range for impurity quantitation. |

| Placebo/Matrix Components | Essential for validating specificity and accuracy in drug product methods. Ensures that excipients or matrix components do not interfere with the analyte signal. | Accuracy studies by spiking the placebo with known amounts of analyte. Specificity chromatograms to show no interfering peaks. |

| High-Purity Solvents and Reagents | Form the basis of mobile phases, sample solutions, and buffer preparations. Their quality directly impacts baseline noise, detection sensitivity, and reproducibility. | Preparation of mobile phases for chromatography. Sample and standard preparation. Robustness testing of method parameters. |

| 2-Bromobenzo[h]quinazoline | 2-Bromobenzo[h]quinazoline | 2-Bromobenzo[h]quinazoline is a versatile nitrogen heterocycle building block for anticancer and antimicrobial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 2-Cyclopentylpyridine | 2-Cyclopentylpyridine (CAS 56657-02-4) - For Research Use | Get high-purity 2-Cyclopentylpyridine (CAS 56657-02-4). This C10H13N compound is for research applications only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Navigating the global regulatory guidelines for analytical method validation requires a deep understanding of the harmonized principles in ICH Q2(R2) and their regional implementations by the FDA and EMA. The strategic selection of a comparative method is no longer just about meeting a fixed set of validation parameters. It is about adopting a modernized, science- and risk-based lifecycle approach, as championed by ICH Q14. By starting with a well-defined Analytical Target Profile, conducting thorough risk assessments, and executing a detailed validation plan, researchers can develop robust, reliable, and defensible analytical methods. This rigorous approach not only ensures compliance with global regulatory standards from the FDA, EMA, and USP but also ultimately guarantees the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products reaching patients.

A Step-by-Step Strategy for Selecting Your Comparative Method

The selection of an appropriate comparative method is the foundational step in method validation research. This process determines the reference point against which a new or alternative measurement procedure (the "test method") will be evaluated. The intended use of the test method dictates the performance requirements that the comparative method must help verify, establishing the criteria for selecting a scientifically sound reference [23]. An improperly selected comparative method compromises the entire validation study, potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions about the test method's performance and inappropriate implementation in research or clinical practice.

This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured framework for establishing robust method selection criteria, detailed experimental protocols for comparison, and the statistical tools required for data interpretation, all framed within a rigorous method validation context.

Core Principles and Terminology

Defining Key Performance Characteristics

A clear understanding of key metrological terms is essential for establishing meaningful selection criteria. These definitions form the vocabulary for setting performance benchmarks.

- Accuracy vs. Bias: In method-comparison studies, accuracy typically refers to the closeness of agreement between a test method's results and an accepted reference value. When comparing two clinical methods, the difference in values is more precisely termed bias, which represents the systematic difference of the test method relative to the comparative method [23].

- Precision: This term has two contextual definitions: 1) the closeness of agreement between independent results obtained under stipulated conditions (repeatability), and 2) the degree to which values cluster around the mean of their distribution. Repeatability is a necessary precondition for assessing agreement between methods [23].

- Linearity: The ability of a method to obtain results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range [24].

- Limits of Agreement: A statistical range within which a specified percentage of differences between two measurement methods are expected to fall. Typically, the 95% limits of agreement are calculated as the mean difference (bias) ± 1.96 times the standard deviation of the differences [23].

Hierarchical Criteria for Method Selection

The ideal comparative method is one whose correctness is well-documented. The following hierarchy should guide the selection process, with Category 1 representing the gold standard.

Table: Hierarchy of Comparative Methods for Validation Studies

| Category | Method Type | Key Characteristics | Implication for Bias Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Definitive or Reference Method | A method of highest accuracy in a hierarchy of methods, confirmed through rigorous interlaboratory testing and traceability to reference materials [1]. | Any observed bias is confidently attributed to the test method. |

| Category 2 | Established Routine Method | A method in widespread use and accepted as providing clinically reliable results, but without the formal documentation of a reference method. | Differences must be interpreted with caution. Small differences indicate relative accuracy; large differences require investigation to identify the inaccurate method [1]. |

| Category 3 | Previous Generation Method | The method currently being used, which the new test method is intended to replace. | The goal is to demonstrate equivalent performance to avoid disruptive clinical impacts. |

Experimental Design and Protocols

A robust experimental design is critical for generating reliable data on method comparability. The following protocols outline the key considerations.

Specimen Selection and Handling

The quality of the specimen panel used for comparison directly influences the validity of the results.

- Number of Specimens: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended to provide a reasonable basis for statistical analysis [1] [23]. The primary goal is to cover the entire working range of the method; 20 well-selected specimens covering a wide concentration range can be more informative than 100 random specimens [1].

- Concentration Range: Specimens must be selected to cover the entire physiological and pathological range for which the test method will be used. For example, a thermometer must be validated across hypothermic, normothermic, and febrile ranges to be clinically useful [23].

- Specimen Stability and Timing: For dynamic physiological parameters, measurements must be taken simultaneously or within a time frame where the analyte is stable. The order of measurement should be randomized to avoid systematic bias from time-dependent changes [23]. Stability can be managed through preservatives, refrigeration, or prompt analysis [1].

Data Collection Protocol

The protocol for running specimens and collecting data must minimize introduced variability.

- Measurement Replication: While single measurements per specimen are common, duplicate measurements are strongly recommended. Duplicates should be performed on different aliquots, ideally in different analytical runs, to help identify sample mix-ups, transposition errors, and other mistakes that could invalidate individual data points [1].

- Study Duration: The comparison experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 days, and preferably extended over a longer period (e.g., 20 days) to capture inter-day analytical variation and make the study more representative of routine practice [1].

Figure 1: High-level workflow for a method comparison study.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Graphical Analysis of Data

Visual inspection of data is a fundamental first step in analysis, allowing researchers to identify patterns, outliers, and potential problems.

- Bland-Altman Plot: This is the recommended graph for assessing agreement between two methods. The difference between the paired measurements (Test - Comparative) is plotted on the Y-axis against the average of the two measurements on the X-axis. This plot visually reveals the bias (mean difference) and the spread of the differences (limits of agreement), and can help identify concentration-dependent bias [23].

- Comparison/Scatter Plot: The test method result is plotted on the Y-axis against the comparative method result on the X-axis. A line of identity (y=x) is drawn; if the methods agree perfectly, all points will lie on this line. This plot is useful for visualizing the analytical range and the general relationship between methods [1].

Figure 2: The three-phase analytical workflow for comparison data.

Statistical Methods and Interpretation

Statistical calculations provide numerical estimates of the errors between methods.

Table: Statistical Methods for Analyzing Method Comparison Data

| Statistical Method | Calculation | Application Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias & Limits of Agreement | Bias = Mean of differencesLOA = Bias ± 1.96*SDdiff | Preferred for narrow analytical ranges or when a single estimate of agreement is needed across the range [23]. | The bias is the estimated systematic error. The LOA define the range where 95% of differences between the two methods are expected to lie. |

| Linear Regression | Y = a + bXwhere Y = Test method, X = Comparative method | Used for data covering a wide analytical range. Provides estimates of constant error (y-intercept, a) and proportional error (slope, b) [1]. | A perfect agreement would have a slope of 1 and an intercept of 0. The systematic error at any decision level Xc is SE = (a + b*Xc) - Xc. |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | Measures the strength of the linear relationship between two methods. | Mainly useful for verifying that the data range is wide enough to give reliable regression estimates. An r ≥ 0.99 is desirable for this purpose [1]. | Not a measure of agreement. High correlation can exist even when there is consistent bias between methods. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful execution of a method-comparison study requires both conceptual knowledge and practical tools. The following table details essential resources.

Table: Essential Toolkit for Method-Comparison Studies

| Tool or Resource | Function | Example Use in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| CLSI Guidelines (e.g., EP09-A3) | Provide standardized, internationally recognized protocols for designing and evaluating method-comparison studies [24]. | Ensures the study design, sample size, and statistical analysis meet regulatory and accreditation standards (e.g., FDA, CAP). |

| Specialized Software (e.g., Analyse-it, MedCalc) | Performs complex statistical analyses (Deming regression, Passing-Bablok, Bland-Altman plots) that are not standard in general statistical packages [23] [24]. | Automates the creation of Bland-Altman plots and calculation of bias, limits of agreement, and regression statistics with confidence intervals. |

| Reference Materials | Substances with one or more sufficiently homogeneous and well-established property values used for calibration or assignment of a value [1]. | Used to verify the calibration and traceability of the comparative method, especially if it is a candidate reference method. |

| Power Analysis Tools | Used during the design phase to calculate the necessary sample size based on desired power, alpha, and the smallest clinically important difference [23]. | Prevents a underpowered study that might fail to detect a clinically significant bias between the methods. |

| 3-Methoxypyrrolidin-2-one | 3-Methoxypyrrolidin-2-one, MF:C5H9NO2, MW:115.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyridazino[1,2-a]cinnoline | Pyridazino[1,2-a]cinnoline|High-Qurity|RUO |

Selecting an appropriate analytical procedure is a critical foundational step in method validation research. This decision directly influences the complexity, cost, and timeline of your validation studies and ultimately determines the reliability of the quality control data generated for your drug substance or product. The process involves identifying and evaluating existing methods before committing to laboratory experiments. There are three primary sources for these methods: compendial (officially published in pharmacopeias), reference (from scientific literature or a previously validated source), and routine (in-house developed or modified methods). A systematic evaluation at this stage ensures the selected procedure is fit-for-purpose, aligns with the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), and complies with relevant regulatory guidelines [25] [26]. This guide provides a detailed framework for sourcing and evaluating these potential methods within a comparative method validation strategy.

Categories of Analytical Methods

Compendial Methods

Compendial methods are standardized procedures published in official compendia such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), European Pharmacopoeia (EP), or Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP). They are legally recognized by regulatory authorities and are validated for their intended use.

- Advantages: They are readily available, universally accepted, and do not require full validation, significantly reducing development time and resources. Their use facilitates global market access [26].

- Considerations: While they do not require full validation, their implementation is not without obligation. A compendial verification is required to demonstrate that the method works as expected under the actual conditions of use in your laboratory, with your specific instrument operator, and for your specific drug product [26].

- Typical Applications: Ideal for well-established, simple drug molecules with known and controlled properties. They are commonly used for assays, identification tests, and related substance tests for drugs that have been on the market for some time.

Reference Methods

Reference methods are well-characterized procedures that have been previously validated. They can be sourced from scientific literature, collaborators, or contract research organizations (CROs).

- Advantages: Provides a strong, data-backed starting point, which can be particularly valuable for novel drug modalities or complex analytical techniques. Using a reference method can help in bridging knowledge gaps [27].

- Considerations: The extent of the available validation data can vary. A thorough assessment is needed to determine if the existing validation meets current regulatory standards (e.g., ICH Q2(R1)) and is suitable for your product's specific Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). The process of method transfer from the source laboratory must be meticulously planned and documented [26] [27].

- Typical Applications: Highly valuable in early product development, for biologics, and when a platform method from a similar product can be adapted [26].

Routine Methods

Routine methods are typically in-house developed procedures or modifications of existing methods. They are developed when no suitable compendial or reference method exists.

- Advantages: Can be perfectly tailored to control the specific CQAs of a unique product or to overcome specific challenges related to the sample matrix. They offer maximum flexibility.

- Considerations: This path is the most resource-intensive, requiring full method development and validation from scratch. It demands a deep understanding of the molecule's chemical properties and the analytical technique. The entire lifecycle management, from development to ongoing performance verification, falls on the developing laboratory [25] [27].

- Typical Applications: Essential for new chemical entities, complex formulations like combination products, or when a new analytical technique offers superior specificity or sensitivity.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Method Sources

| Characteristic | Compendial Method | Reference Method | Routine/In-House Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Effort | Low | Moderate | High |

| Regulatory Acceptance | High (Pre-established) | Requires Assessment | Must be Demonstrated |

| Validation Requirement | Verification | Transfer/Partial Validation | Full Validation |

| Cost & Timeline | Low/Fast | Moderate/Medium | High/Slow |

| Flexibility | Low | Moderate | High |

| Ideal Use Case | Standardized, simple drugs | Novel drugs with existing models | Unique CQAs, no existing method |

A Framework for Method Evaluation

Once potential methods are sourced, a systematic, risk-based evaluation must be conducted to select the most suitable candidate for validation.

Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and Fit-for-Purpose

The evaluation begins with a clear definition of the ATP. The ATP is a predefined objective that outlines the required performance characteristics of the method [25] [26]. It states what the method needs to achieve (e.g., "quantify impurity X at a level of 0.1% with an accuracy of 90-110%") rather than how to achieve it. The fit-for-purpose concept is central to this, meaning the validation scope should be appropriate for the product's development stage—simpler approaches for early stages and full validation for commercial filing [26].

The principles of Quality by Design (QbD) can be applied during method development to build robustness into the procedure by understanding the impact of critical method parameters [25].

Key Parameters for Evaluation

The following performance characteristics, as defined in guidelines like ICH Q2(R1), should be evaluated against the ATP to determine a method's suitability [28].

- Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. For drug products, it is typically assessed by spiking known amounts of analyte and measuring percent recovery [28].

- Precision: The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. This includes repeatability (intra-assay), intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst, inter-equipment), and reproducibility (inter-laboratory) [28].

- Specificity: The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components like impurities, degradants, or matrix. This is demonstrated by resolving the analyte peak from the closest eluting potential interferent [28].

- Linearity and Range: The ability to obtain test results proportional to analyte concentration within a given range. Linearity is demonstrated across a minimum of five concentration levels [28].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) & Quantitation (LOQ): The lowest concentration that can be detected or quantitated with acceptable accuracy and precision. These are often determined based on signal-to-noise ratios (3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ) or statistical approaches [28].

- Robustness: A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate), indicating its reliability during normal usage [28].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Key Evaluation Parameters

| Parameter | Experimental Protocol Summary | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Analyze a minimum of 9 determinations across 3 concentration levels covering the specified range. For drug products, use synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities [28]. | Report as % recovery of the known, added amount (e.g., 98-102%). |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Analyze a minimum of 9 determinations covering the specified range (e.g., 3 concentrations, 3 replicates each) or 6 determinations at 100% of test concentration [28]. | Report as % Relative Standard Deviation (% RSD). |

| Linearity | Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentrations spanning the declared range of the method [28]. | Correlation coefficient (r²), slope, and y-intercept of the calibration curve. Residuals should be random. |

| Specificity | For chromatographic methods, inject samples containing potential interferents (impurities, degradants, matrix). Use peak purity tools (e.g., photodiode-array or mass spectrometry) to demonstrate the analyte peak is pure [28]. | Resolution between the analyte and closest eluting peak; Peak purity index match. |

| Robustness | Deliberately vary method parameters (e.g., ± 0.1 pH units, ± 2°C column temperature) using an experimental design (e.g., Design of Experiments) and monitor the effect on system suitability criteria [28] [27]. | Method meets system suitability requirements despite variations. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical decision process for sourcing and evaluating analytical methods.

Method Sourcing and Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful evaluation and validation of an analytical method depend on the quality and consistency of the materials used. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Evaluation & Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for quantifying the analyte and establishing method accuracy, linearity, and precision. Their purity and traceability are paramount [27]. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Artificially degraded samples (via heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) are used to demonstrate method specificity by proving the method can separate the analyte from its degradation products [26]. |

| System Suitability Standards | A reference preparation used to verify that the chromatographic system (or other instrument) is performing adequately at the time of testing. Parameters like retention time, tailing factor, and plate count are monitored [28]. |

| High-Purity Reagents & Solvents | Essential for preparing mobile phases, buffers, and sample solutions. Impurities can cause baseline noise, ghost peaks, and interference, adversely affecting LOD/LOQ and specificity. |

| Spiking Materials (Impurities) | Isolated or synthesized impurities, aggregates, or related substances are used in spiking studies to prove method accuracy and specificity for impurity tests, as demonstrated in the SEC case study [26]. |

| 5-Fluoro-2-methylpiperidine | 5-Fluoro-2-methylpiperidine HCl |

| 3-Vinylpiperidine | 3-Vinylpiperidine|High-Purity Research Chemical |

Regulatory and Lifecycle Considerations

Under the ICH Q14 guideline, analytical procedures are now viewed through a lifecycle management lens [25]. This means that the initial selection of a method should consider its long-term suitability and the potential for future changes.

When changes to a method are necessary, a risk-based assessment is required to determine the level of study needed. Two key concepts are:

- Comparability: Demonstrating that a modified method yields results sufficiently similar to the original. This is often sufficient for low-risk changes [25].

- Equivalency: A more rigorous assessment, often requiring a full validation, to demonstrate a replacement method performs equal to or better than the original. This is required for high-risk changes and needs regulatory approval [25].

For methods used at multiple sites, a formal analytical transfer process is mandatory to confirm the method performs consistently in the receiving laboratory. Approaches include comparative testing, covalidation, or validation at the receiving site [26].

Sourcing and evaluating potential analytical methods is a strategic process that sets the trajectory for successful method validation. By systematically assessing compendial, reference, and routine methods against a predefined Analytical Target Profile, scientists can select the most efficient and robust path forward. Adopting a lifecycle mindset, as encouraged by ICH Q14, and employing a fit-for-purpose approach ensures that the chosen method is not only validated for today's needs but remains suitable and compliant throughout the product's lifetime. A rigorous evaluation at this stage is an investment that pays dividends in robust data, regulatory success, and the assurance of product quality and patient safety.

The comparison of methods experiment is a critical component of method validation, serving to estimate the systematic error, or inaccuracy, of a new test method relative to a comparative method [29]. When framed within the broader thesis of selecting a comparative method, the design of this experiment is paramount. The fundamental assumption is that the comparative method provides correct results; the interpretation of the experimental outcomes hinges on this premise [29]. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed protocol for designing and executing this definitive experiment, ensuring that the selected comparator provides a robust benchmark for assessing the new method's performance.

Key Factors in Experimental Design

The integrity of the comparison study depends on several key design factors, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Experimental Design Factors for Method Comparison

| Factor | Consideration & Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Comparative Method | Preferably a reference method; otherwise, a routine method with documented correctness [29]. | Errors are attributed to the test method if the comparator's correctness is known. Discrepancies with a routine method require careful interpretation [29]. |

| Number of Specimens | Minimum of 40 patient specimens, carefully selected to cover the entire working range [29]. For specificity assessment, 100-200 specimens are recommended [29]. | Quality and range of concentrations are more critical than a large number of random specimens. A wide range ensures reliable statistical estimates [29]. |

| Measurements | Common practice: single measurement. Advantageous: duplicate measurements on different samples or in different runs [29]. | Duplicates act as a check for sample mix-ups, transposition errors, and other mistakes, validating discrepant results [29]. |

| Time Period | A minimum of 5 days, ideally extended over a longer period (e.g., 20 days) with 2-5 specimens per day [29]. | Minimizes systematic errors that could occur in a single analytical run and incorporates routine day-to-day variation [29]. |

| Specimen Stability | Analyze test and comparative methods within two hours of each other, unless stability data indicates otherwise [29]. | Prevents specimen degradation from being a source of observed difference between the methods [29]. |

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Graphical Analysis

The first step in data analysis is to graph the results for visual inspection, ideally as data is collected [29].

- Difference Plot: Used when methods are expected to show one-to-one agreement. This plot displays the difference between the test and comparative results (test minus comparative) on the y-axis against the comparative result on the x-axis. Data should scatter around the zero line, allowing for immediate identification of large discrepancies and potential constant or proportional errors [29].

- Comparison Plot: Used when methods are not expected to agree one-to-one (e.g., different enzyme reaction conditions). This plot displays the test result on the y-axis against the comparative result on the x-axis. A visual line of best fit shows the general relationship [29].

Statistical Calculations

Statistical calculations provide numerical estimates of systematic error. The appropriate method depends on the analytical range of the data [29].

For a Wide Analytical Range (e.g., glucose, cholesterol): Linear Regression Analysis Linear regression (least squares analysis) is used to calculate the slope (b) and y-intercept (a) of the line of best fit, and the standard deviation of the points about that line (s~y/x~) [29]. The systematic error (SE) at a specific medical decision concentration (X~c~) is calculated as follows:

Y~c~ = a + bX~c~SE = Y~c~ - X~c~Example: Given a regression line Y = 2.0 + 1.03X, the systematic error at X~c~ = 200 is calculated as Y~c~ = 2.0 + 1.03200 = 208, thus SE = 208 - 200 = 8 mg/dL* [29]. The correlation coefficient, r, is also calculated. A value ≥ 0.99 indicates a sufficiently wide data range for reliable regression estimates [29].For a Narrow Analytical Range (e.g., sodium, calcium): Average Difference (Bias) The average difference (bias) between the two methods is calculated, typically using a paired t-test, which also provides the standard deviation of the differences [29].

Table 2: Summary of Statistical Methods for Data Analysis

| Analysis Method | Application | Key Outputs | Estimation of Systematic Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Wide analytical range | Slope (b), Y-intercept (a), Standard Error of Estimate (s~y/x~) | SE = (a + bX~c~) - X~c~ at critical decision concentration X~c~ [29] |

| Paired t-test / Average Difference | Narrow analytical range | Mean difference (Bias), Standard deviation of differences | The mean difference itself is the estimate of constant systematic error [29] |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for designing and executing a comparison of methods experiment, from planning to final interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful comparison experiment relies on carefully selected materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for the Comparison Experiment

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Characterized Patient Specimens | The core of the experiment. These should cover the clinical range and represent the expected spectrum of diseases to challenge the method's real-world performance [29]. |

| Reference Materials / Controls | Used to verify the correct calibration and ongoing performance of both the test and comparative methods throughout the study period. |

| Calibrators for Test Method | Essential for establishing the correct calibration curve for the new method prior to and during the analysis of patient specimens. |

| Reagents for Test Method | The specific chemical reagents, antibodies, or other detection molecules required for the analytical reaction of the candidate method. |

| Reagents for Comparative Method | The specific reagents required for the established comparative or reference method. |