Mastering the Trade-Off: A Practical Guide to Exploration and Exploitation in Bayesian Optimization for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the exploration-exploitation trade-off in Bayesian Optimization (BO), a critical challenge for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedicine.

Mastering the Trade-Off: A Practical Guide to Exploration and Exploitation in Bayesian Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the exploration-exploitation trade-off in Bayesian Optimization (BO), a critical challenge for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedicine. We cover foundational concepts, including acquisition functions and Gaussian Process surrogates, and detail methodological advances for high-dimensional, multi-objective problems. The guide addresses common pitfalls, such as performance degradation beyond 20 dimensions and the risks of incorporating unhelpful expert knowledge, and presents real-world case studies of successful BO implementation in large-scale combination drug screens. Finally, we offer validation frameworks and comparative analyses to help practitioners select and optimize BO strategies for their specific experimental constraints.

The Core Dilemma: Understanding Exploration vs. Exploitation in Bayesian Optimization

Defining the Black-Box Optimization Problem in Biomedical Research

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is a "black-box" function in the context of biomedical optimization?

In biomedical optimization, a "black-box" function represents your experimental system. You provide an input (e.g., a biological sequence, a drug concentration, an experimental protocol) and observe an output (e.g., therapeutic efficacy, protein expression level, cell growth rate). The internal workings of the system are complex, nonlinear, and not fully understood, meaning you cannot easily see or model the precise mechanism that transforms your input into the observed output. Evaluating this function is often expensive, time-consuming, and noisy [1] [2].

What are the standard mathematical and practical constraints of a black-box optimization problem?

The problem is formally defined as finding the global optimum (maximum or minimum) of a function ( f(x) ), subject to several key constraints that are common in biomedical settings [3] [2].

Table: Standard Constraints in Biomedical Black-Box Optimization

| Constraint Type | General Description | Biomedical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Feasible Set | Simple, often box constraints. | A drug concentration must be between 0 and 100 µM. |

| Function Structure | Lacks useful structure (e.g., concavity). | A cell growth response to multiple cytokines is nonlinear and multi-peaked. |

| Derivative-Free | Evaluations do not provide gradient information. | A high-throughput assay gives a viability score, not a gradient. |

| Expensive Evaluation | Severely limited number of evaluations. | A wet-lab experiment takes days or weeks and costs thousands of dollars. |

| Noise | Observations may be noisy. | Measurement error in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. |

Troubleshooting Common Optimization Challenges

My Bayesian optimization is converging too quickly to a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration?

This is a classic symptom of an imbalance tilted too heavily towards exploitation. The algorithm is overusing what it already knows and failing to investigate potentially more promising, uncertain regions.

- Adjust your acquisition function: The hyperparameter ( \epsilon ) in the Probability of Improvement (PI) function directly controls exploration. Increasing ( \epsilon ) makes the algorithm more likely to probe points with higher uncertainty [3].

- Switch your acquisition function: Consider using Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), which have more innate mechanisms for balancing exploration with exploitation. For UCB, the parameter ( \kappa ) explicitly controls this trade-off; a higher ( \kappa ) value places more weight on exploration [4] [5].

- Quantify exploration: Recent research has proposed metrics like "observation traveling salesman distance" and "observation entropy" to quantitatively measure the exploration characteristics of your optimization run. Analyzing this can help you diagnose an exploration deficit [6].

The performance of my optimization algorithm varies drastically across different biological tasks. How can I make my pipeline more robust?

This is a common and significant obstacle in real-world applications, where different biological systems can have vastly different landscape characteristics [7] [8].

- Adopt a population-based approach: Instead of relying on a single optimization algorithm, use a Population-Based Black-Box Optimization (P3BO) strategy. This method maintains an ensemble of different optimization algorithms. It allocates more evaluations to the methods that have recently proposed high-quality sequences, dynamically hedging against the poor performance of any single method [7] [8].

- Online hyperparameter adaptation: Use evolutionary optimization to adapt the hyperparameters of each method in your population online, further improving robustness and performance across diverse tasks [7].

How can I validate a black-box medical algorithm for clinical use, given its opacity and potential to change over time?

The opacity and plasticity (frequent updates) of these algorithms challenge traditional validation models like clinical trials [9].

- Implement a multi-step validation process:

- Procedural Validation: Ensure the algorithm was developed using well-vetted techniques and trained on high-quality, representative data.

- Predictive Validation: For algorithms that measure known quantities, use held-back test datasets to demonstrate performance against a ground truth.

- Continuous Real-World Validation: Integrate the algorithm into a learning health-care system where its outcomes are tracked and analyzed retrospectively. This provides ongoing validation and data for safe, dynamic updates [9].

- Prioritize transparency: Given the inherent opacity, details about the algorithmic development process, training data, and techniques should be as open as possible to facilitate independent review and build trust [9].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Setting up a Bayesian Optimization for a Biological Sequence Design Task

This protocol outlines the steps for using Bayesian Optimization (BO) to design biological sequences (e.g., proteins, DNA) with desired properties [7] [5].

- Problem Formulation: Define your search space ( X ) (e.g., all possible 100-amino-acid sequences) and the expensive black-box function ( f(x) ) to maximize (e.g., binding affinity measured in an assay).

- Choose a Surrogate Model: Select a probabilistic model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), to act as a surrogate for the true function. The GP will model your beliefs about the function and its uncertainty based on observed data.

- Select an Acquisition Function: Choose a function to guide the next experiment. Common choices are Expected Improvement (EI), Probability of Improvement (PI), or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [4] [5] [3].

- Initial Experimental Round: Run an initial set of experiments (e.g., using a Latin Hypercube design or random selection) to gather the first data points ( (x1, f(x1)), (x2, f(x2)), ... ).

- Iterative Optimization Loop: a. Update Surrogate: Use all collected data to update the posterior of the GP surrogate model. b. Maximize Acquisition: Find the point ( x{next} ) that maximizes the acquisition function ( \alpha(x) ). c. Conduct Experiment: Evaluate the true function ( f(x{next}) ) via your wet-lab assay. d. Augment Data: Add the new observation ( (x{next}, f(x{next})) ) to your dataset.

- Termination: Repeat Step 5 until a stopping condition is met (e.g., budget exhausted, performance plateau).

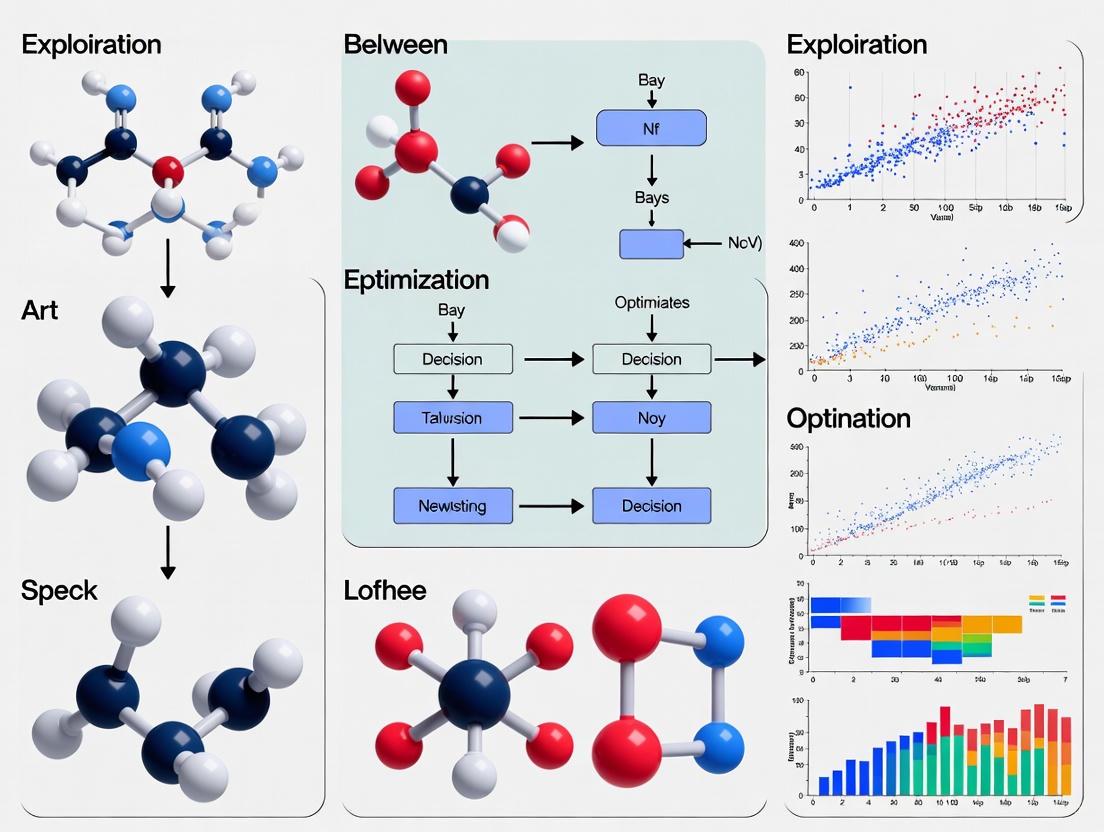

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of Bayesian Optimization:

What are the key acquisition functions and when should I use them?

Table: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions

| Acquisition Function | Mechanism | Best For | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Selects point with highest probability of being better than current best. | Quick convergence when the optimum region is roughly known. | ( \epsilon ): Controls exploration. Increase to explore more. [3] |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Selects point with highest expected improvement over current best. | A robust, general-purpose choice with a good balance. | None; generally well-balanced. [5] [3] |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Selects point that maximizes ( \mu(x) + \kappa\sigma(x) ). | Explicit, direct control over the exploration-exploitation trade-off. | ( \kappa ): Explicitly trades off mean (exploitation) and uncertainty (exploration). [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for a Black-Box Optimization Pipeline in Biomedicine

| Tool or Reagent | Function in the Optimization Workflow |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate | A probabilistic model that approximates the expensive black-box function, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates at untested points [5]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., EI, UCB) | The decision-making engine that uses the GP's predictions to propose the most informative next experiment, balancing exploration and exploitation [5] [3]. |

| High-Throughput Assay System | The wet-lab platform (e.g., plate reader, sequencer, flow cytometer) that provides the expensive functional readout for the designed sequences or conditions [1]. |

| Population-Based Optimizer (P3BO) | A meta-optimization framework that combines multiple algorithms to improve robustness across different tasks and biological systems [7] [8]. |

| Automated Experimentation Platform | Integrated robotic systems that physically prepare and test proposed samples, closing the loop for fully autonomous experimental optimization [1]. |

| LX-6171 | LX-6171, CAS:914808-66-5, MF:C22H20ClN3O, MW:377.9 g/mol |

| LY 178002 | LY 178002, CAS:107889-32-7, MF:C18H25NO2S, MW:319.5 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In Bayesian optimization, what is the equivalent of "digging where we already found gold"? This is exploitation. It involves sampling parameter sets where the surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) predicts a high reward, based on existing data. This is like a gold miner returning to a proven spot to extract more known gold [10] [4].

Q2: What does "exploring new terrain" correspond to in the algorithm? This is exploration. The algorithm probes regions of the parameter space where the model's uncertainty (variance) is high. While these areas might not have high predicted rewards, they could hide untapped potential, much like a prospector searching for a new, rich gold seam [10] [11].

Q3: How does the algorithm decide between these two strategies? The balance is managed by an acquisition function. This function uses the surrogate model's prediction (mean) and uncertainty (variance) to score every point in the space. The next point to evaluate is the one that maximizes this function, automatically balancing the desire for high rewards with the need to reduce uncertainty [4].

Q4: Our optimization seems stuck in a local region. Is the model too exploitative? This is a common issue. Your acquisition function may be over-prioritizing areas with good-but-not-optimal results. To encourage exploration, you can adjust the trade-off parameter in your acquisition function (e.g., increase κ in the Upper Confidence Bound function) or try a more explorative function like Thompson Sampling [4].

Q5: Why should we expect "heavy-tailed distributions" in our research, and what is the implication? Like gold in the earth, the effectiveness of different research avenues or parameter configurations is often spread unevenly. A few "seams" yield massive rewards, while many yield little. This "heavy-tailed" property means that finding these top percentiles is crucial for breakthrough success, justifying a rigorous search strategy [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Balancing Your Search

| Observed Issue | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solution / Workaround |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence to local optimum | Over-exploitation; acquisition function ignores high-uncertainty regions [4]. | Check the model's posterior variance in unsampled areas. Is it high? | Increase the exploration weight (e.g., κ) in the UCB acquisition function [4]. |

| Slow or no convergence | Over-exploration; the algorithm spends too many iterations in low-reward, high-uncertainty regions [10]. | Analyze the evaluation history. Are successive samples rarely in high-reward areas? | Switch to a more exploitative acquisition function (e.g., Probability of Improvement) or reduce the exploration weight [10]. |

| High model uncertainty everywhere | Insufficient initial data or an inappropriate kernel for the GP surrogate model [10]. | Review the initial design-of-experiments and the kernel's length-scales. | Expand the initial sampling (space-filling design) or re-specify the GP kernel to better match the function's properties [10]. |

| Performance plateaus after initial gains | The algorithm has exhausted "easy-to-find" gold and struggles to locate a richer seam [11]. | Compare current best reward to potential global optimum. Is there a large gap? | "Restart" the optimization with a more explorative setting or incorporate domain knowledge to guide the search to new regions [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing and Tuning Bayesian Optimization

1. Objective To efficiently find the global optimum of a black-box, expensive function by implementing a Bayesian Optimization (BO) procedure with a tunable exploration-exploitation trade-off.

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Initial Setup. Select a Gaussian Process (GP) with a Matérn kernel as the surrogate model. Choose an initial space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to collect the first set of observations [10].

- Step 2: Iteration Loop.

- Model Training: Update the GP model with all available

(parameters, reward)data. - Acquisition Maximization: Calculate the acquisition function across the parameter space. Select the next point

x*that maximizes this function. - Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the expensive function at

x*, record the reward, and add the new data point to the observation set [10] [4].

- Model Training: Update the GP model with all available

- Step 3: Termination. Continue the loop until a performance plateau is reached, a budget is exhausted, or the optimum is found within a desired tolerance.

3. Key Experiment: Acquisition Function Comparison

- Purpose: To empirically determine the most effective acquisition function for a specific problem domain.

- Procedure:

- Data Analysis: Summarize the results in a table for clear comparison.

Table: Sample Results from Acquisition Function Comparison on Benchmark Function

| Acquisition Function | Final Best Reward (Mean ± SD) | Iterations to Converge (Mean ± SD) | Notes on Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | 95.2 ± 3.1 | 45 ± 8 | Balanced trade-off; robust performance [4]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | 96.5 ± 2.5 | 38 ± 6 | More exploitative; faster convergence to good solutions [4]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | 90.1 ± 5.7 | 52 ± 10 | Prone to getting stuck in local optima [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Analogy |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | The core surrogate model that approximates the unknown objective function and provides predictions with uncertainty estimates [10] [4]. |

| Acquisition Function | The decision-making engine that balances exploration and exploitation by scoring the utility of evaluating each point [10] [4]. |

| Matérn Kernel | A common choice for the GP covariance function, controlling the smoothness of the surrogate model and how it generalizes from observed data [10]. |

| Space-Filling Design | The initial set of parameter evaluations (e.g., Latin Hypercube) that helps build a preliminary model before the sequential BO process begins [10]. |

| LY2109761 | LY2109761, CAS:700874-71-1, MF:C26H27N5O2, MW:441.5 g/mol |

| LY2183240 | LY2183240, CAS:874902-19-9, MF:C17H17N5O, MW:307.35 g/mol |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Bayesian Optimization Loop

Gold Analogy Core Concepts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a Gaussian Process (GP), and how does it function as a surrogate model?

A Gaussian Process (GP) is a stochastic process—a collection of random variables indexed by time or space—where any finite collection of these variables has a joint Gaussian distribution [12]. As a surrogate model, it provides a probabilistic approach to approximating an unknown, often complex, function. Instead of specifying a parametric form for the function, a GP defines a prior distribution over possible functions directly in the function space, which is then updated with observed data to form a posterior distribution over these functions [13] [14]. This posterior is used to make predictions along with a measure of uncertainty (variance) at unobserved points, forming the core of its use in tasks like Bayesian optimization [13] [15].

2. What are the roles of the mean function and covariance kernel in a GP?

The mean function and covariance kernel (or covariance function) completely define a Gaussian Process [12].

- Mean Function: Often initially set to zero or a simple constant, it represents the expected value of the function before seeing any data. The posterior mean, after conditioning on data, becomes the primary prediction for the surrogate model [13].

- Covariance Kernel: This function,

k(x, x'), specifies the covariance between two function values at input pointsxandx'. It encodes prior assumptions about the function's properties, such as smoothness, periodicity, and how quickly the function values can change [13] [12]. The choice of kernel is critical as it controls the structure of the functions that the GP can model.

3. What are some common covariance kernels and their properties?

The table below summarizes frequently used kernels, where d = |x - x'| is the distance between two points [12].

| Kernel Name | Mathematical Form | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Squared Exponential | exp(-d² / (2ℓ²)) |

Very smooth, infinitely differentiable. |

| Matérn | (2^(1-ν)/Γ(ν) * (√(2ν)d/ℓ)^ν * K_ν(√(2ν)d/ℓ) |

Generalization of SE; controls smoothness via ν. |

| Ornstein-Uhlenbeck | exp(-d / â„“) |

Less smooth than SE; generates rough functions. |

| Periodic | exp(- (2 * sin(π d / p)²) / ℓ² ) |

Models repeating patterns, with period p. |

| Rational Quadratic | (1 + d²)^(-α) |

Scale mixture of SE kernels; more flexible. |

4. How do GPs balance exploration and exploitation in Bayesian Optimization?

In Bayesian Optimization (BO), the GP surrogate model is used to guide the search for the optimum of a black-box function. An acquisition function uses the GP's predictive mean (which encourages exploitation of known promising areas) and predictive variance (which encourages exploration of uncertain regions) to decide where to sample next [4]. The acquisition function formulates a trade-off between these two goals. For example, the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function, α_UCB(x) = μ(x) + κ σ(x), explicitly balances the mean prediction μ(x) (exploitation) and the uncertainty σ(x) (exploration) through the parameter κ [15] [4].

5. What are the common pitfalls when using GPs for Bayesian Optimization?

Several common issues can lead to poor performance [15]:

- Incorrect Prior Width: Mis-specifying the hyperparameters of the covariance kernel, particularly the lengthscale

ℓand signal varianceσ², can lead to a model that is overly confident or uncertain, misleading the optimization. - Over-smoothing: If the kernel function forces the surrogate model to be too smooth, it may fail to capture important local variations or sharp peaks of the underlying objective function.

- Inadequate Acquisition Function Maximization: The acquisition function can be multi-modal and complex. Using an ineffective optimizer to find its maximum can result in suboptimal query points.

- Poor Performance in High Dimensions: BO empirically struggles in domains with more than about 20 dimensions. The volume of the search space grows exponentially, making it difficult for the GP to model the function accurately with a limited budget of function evaluations [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Model Fit and Inaccurate Predictions

Symptoms:

- The GP mean function does not adequately fit the observed training data.

- Predictive uncertainty seems poorly calibrated (too confident or not confident enough).

Resolution:

- Check Kernel Choice: Your kernel may be too rigid for the function. A common default is the Squared Exponential kernel, which assumes smoothness. If your function has sharp changes or discontinuities, consider a different kernel like the Matérn class [12].

- Optimize Hyperparameters: The kernel hyperparameters (e.g., lengthscale

ℓ, signal varianceσ²) critically impact model performance. Use methods like maximum likelihood estimation or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to optimize these parameters based on your data, rather than relying on default values [15]. - Review the Mean Function: A zero-mean prior is common, but if there is a known underlying trend in your data, incorporating a non-zero mean function (e.g., linear or quadratic) can improve performance.

Problem 2: Ineffective Bayesian Optimization Convergence

Symptoms:

- The optimization process gets stuck in a local optimum.

- The algorithm fails to find a good solution within a reasonable budget of evaluations.

Resolution:

- Diagnose Exploration-Exploitation Balance: Analyze the behavior of your acquisition function. If it's over-exploiting, it may get stuck in local optima. If it's over-exploring, convergence will be slow. Try different acquisition functions (e.g., switch from Expected Improvement to Upper Confidence Bound) and adjust their parameters (e.g., the

κparameter in UCB) [15] [4]. - Validate Surrogate Model Quality: A poor GP model will misguide the acquisition function. Ensure your GP is providing a reasonable fit to the data collected so far (see Problem 1). The problem might be an over-smoothed surrogate model that fails to guide the search effectively [15].

- Ensure Thorough Maximization: The acquisition function itself needs to be maximized effectively. Use a robust optimizer with multiple restarts to find its true global maximum, rather than just a local peak [15].

Problem 3: Scaling Issues and High-Dimensional Challenges

Symptoms:

- Long computation times for model fitting and prediction.

- Noticeable performance degradation when the number of input dimensions exceeds 10-20.

Resolution:

- Employ Sparse GP Methods: For large datasets, use sparse Gaussian process approximations to reduce the computational complexity from O(n³) to more manageable levels.

- Leverage Problem Structure: In high dimensions, assume and exploit structure like sparsity (only a few dimensions are important) or use lower-dimensional embeddings [16]. Methods like Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspaces (SAAS) can be effective.

- Use Different Surrogates: For very high-dimensional problems (e.g., in molecule design), consider alternatives like Bayesian neural networks or ensembles, which might scale more favorably than standard GPs [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for Gaussian Process Regression

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for constructing and using a Gaussian Process surrogate model.

Methodology:

- Define Prior: Select a mean function (often zero) and a covariance kernel with initial hyperparameters. This defines your prior belief about the function space before seeing data [13] [12].

- Collect Data: Gather a set of input-output pairs

(x, y)from the function you wish to model. - Fit Model: Condition the GP prior on the observed data. This involves computing the posterior distribution, which is typically done analytically for GPs. Optimize the kernel hyperparameters (e.g., lengthscale, variance) by maximizing the marginal likelihood of the data [13] [14].

- Make Predictions: For any new test point

x*, the posterior GP provides a Gaussian predictive distribution for the function valuef(x*), characterized by a mean and variance [13]. - Utilize Model: Use the predictive distribution for downstream tasks. In Bayesian optimization, the mean and variance are fed into an acquisition function to select the next point to evaluate [15].

Integrated Bayesian Optimization Loop

The following diagram details the iterative loop that integrates the GP surrogate with an acquisition function for optimization.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Start with an initial dataset (e.g., from a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling).

- Model Update: Fit the GP surrogate model to all data collected so far.

- Acquisition Maximization: Use the GP's predictive distribution to compute the acquisition function over the domain. Find the point

x_nextthat maximizes this function. This step explicitly balances exploration and exploitation [15] [4]. - Function Evaluation: Evaluate the expensive black-box function at the chosen

x_next. - Data Augmentation: Add the new

(x_next, y_next)pair to the dataset. - Iterate: Repeat steps 2-5 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., evaluation budget exhausted or improvement falls below a threshold).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines the essential "reagents" or components needed to build and use Gaussian Process surrogate models effectively.

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Covariance Kernels | Define the properties of the function space. The Squared Exponential kernel assumes smoothness, the Matérn kernel offers control over smoothness, and the Periodic kernel captures repeating patterns [12]. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | "Fits" the model to the data. Maximum Likelihood Estimation is common, but Bayesian approaches like MCMC can also be used to infer distributions over hyperparameters [15]. |

| Acquisition Functions | Guide the search in Bayesian Optimization. Expected Improvement (EI) measures the average improvement over the best-seen value, while Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) uses a confidence interval strategy [15] [4]. |

| Cholesky Decomposition | A key numerical linear algebra technique for stable and efficient computation of the GP posterior. It is used to compute the square root of the covariance matrix for sampling and prediction [14]. |

| LY256548 | LY256548, CAS:107889-31-6, MF:C19H27NO2S, MW:333.5 g/mol |

| LY-411575 | LY-411575, CAS:209984-57-6, MF:C26H23F2N3O4, MW:479.5 g/mol |

The Role of Acquisition Functions as Balancing Mechanisms

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental purpose of an acquisition function? The acquisition function is the core decision-making engine in Bayesian Optimization (BO). Its primary purpose is to guide the selection of the next point to evaluate in the expensive black-box function by quantitatively balancing exploration (sampling from uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling near known good solutions) [4] [17]. It converts the probabilistic predictions of the Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model into a single measure of utility for each point, creating a much cheaper function to optimize than the original problem [18] [17].

2. My BO algorithm is converging to a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration? This is a common symptom of an over-exploitative strategy. You can address it by:

- Tuning the acquisition function's parameter: If using the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), increase the

κorλparameter to give more weight to the uncertainσ(x)term [4] [18]. This makes the algorithm favor less-explored regions. - Switching the acquisition function: Consider using an acquisition function with more explorative properties. Probability of Improvement (PI) can be modified with a trade-off parameter, though it primarily focuses on the probability of improvement, not its magnitude [18].

3. My optimization is too random and not refining good solutions. How can I improve exploitation? This indicates excessive exploration. To encourage more exploitation:

- Tuning the acquisition function's parameter: For UCB, decrease the

κorλparameter. This shifts the balance towards the mean predictionμ(x), causing the algorithm to sample more aggressively around the current best solution [18]. - Switching the acquisition function: Expected Improvement (EI) naturally balances the size of potential improvements against their probability, often leading to a good balance, but it can be tuned to be more exploitative [15] [18].

4. How do I choose the right acquisition function for my problem? There is no single "best" acquisition function, as the optimal choice can depend on the specific problem landscape [19]. The following table compares the most common functions. Frameworks like BOOST automate this selection by testing candidate pairs on existing data to identify the best performer before the main optimization begins [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Form | Exploration-Exploitation Character | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [4] [18] | μ(x) + κσ(x) |

Explicit, tunable via κ parameter. |

Problems where a clear balance between exploration and exploitation is needed and can be predetermined. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) [15] [18] | (μ(x) - f(x*))Φ(Z) + σ(x)φ(Z) |

Balanced; considers both probability and magnitude of improvement. | General-purpose use; a strong default choice in many practical scenarios. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) [18] | Φ((μ(x) - f(x*)) / σ(x)) |

Tends to be more exploitative; can get stuck in local optima. | When you are primarily concerned with the likelihood of any improvement, however small. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Convergence Performance

Symptoms

- The algorithm fails to find the global optimum, getting stuck in a local minimum/maximum.

- Slow improvement in the best-observed value over successive iterations.

Diagnosis and Solutions Poor convergence often stems from an incorrect exploration-exploitation balance or other hyperparameter issues [15] [20].

- Diagnose the Balance: Plot the GP model and the acquisition function over the search space. Observe if the algorithm is consistently ignoring promising, uncertain regions (over-exploitation) or wasting evaluations on poor, random regions (over-exploration) [18].

- Adjust Acquisition Hyperparameters: As per the FAQs, tune parameters like

κin UCB. This is a critical step often overlooked in practice [15]. - Check Surrogate Model Hyperparameters: The performance of the acquisition function is dependent on a well-specified GP.

- Incorrect Prior Width: A poorly chosen kernel amplitude (prior width) can lead to overconfident or underconfident models, misleading the acquisition function. Use marginal likelihood maximization to fit GP hyperparameters [15].

- Over-smoothing: An excessively large lengthscale in the kernel can cause the GP to oversmooth the true function, missing important local features. Ensure the lengthscale is appropriately fitted to the data [15].

- Ensure Adequate Acquisition Maximization: The acquisition function itself must be globally optimized to suggest the best next point. Inadequate optimization (e.g., using a simple method that gets stuck in local optima of the acquisition function) can break the BO process. Consider using global optimization methods or advanced techniques like Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming (MIQP) for a piecewise-linear kernel approximation [21].

Problem: Inefficient Use of Evaluation Budget

Symptoms

- The algorithm seems to "dither" or make redundant evaluations in similar, suboptimal areas.

- The model uncertainty remains high in large portions of the search space even after many evaluations.

Diagnosis and Solutions This points to a failure in the acquisition function's guiding mechanism.

- Validate the Kernel Choice: The acquisition function's decisions are only as good as the GP model. An inappropriate kernel that doesn't match the function's characteristics (e.g., using a smooth RBF kernel for a noisy or discontinuous function) will provide poor guidance. Consider using more flexible kernels like the Matern kernel [22] or a modular kernel architecture [19].

- Implement Automated Configuration Selection: For a robust, hands-off approach, employ a framework like BOOST. It performs lightweight offline evaluations on your existing data to automatically select the best kernel-acquisition function pair before the costly optimization begins, ensuring an efficient configuration from the start [19].

- Account for Noise: In real-world biological experiments, noise (especially heteroscedastic noise) is common. Use a GP model that can incorporate a noise model to prevent the acquisition function from being misled by measurement errors [22].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Bayesian Optimization Loop

This is the foundational workflow for most BO applications.

Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Components for Bayesian Optimization

| Component | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | Approximates the unknown objective function; provides mean and uncertainty predictions. | Gaussian Process (GP) is the standard. Alternatives include Bayesian neural networks. |

| Kernel (Covariance Function) | Defines the smoothness and structure of the surrogate model. | RBF: Assumes smooth, infinitely differentiable functions. Matern: More flexible, better for rough or noisy functions [22]. |

| Acquisition Function | Balances exploration and exploitation to suggest the next evaluation point. | EI, UCB, PI. The choice is critical and can be automated [19]. |

| Acquisition Optimizer | Solves the inner loop problem of finding the point that maximizes the acquisition function. | L-BFGS-B, multi-start gradient descent, or global methods like MIQP [21]. |

Methodology:

- Initialization: Start with an initial dataset

D_n = {x_i, f(x_i)}of evaluated points, often generated by a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling). - Model Fitting: Fit a Gaussian Process surrogate model to the current data

D_n. - Acquisition Maximization: Using the trained GP, optimize the acquisition function

α(x)to select the next point to evaluate:x_(n+1) = argmax α(x). - Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the expensive black-box function at

x_(n+1)to obtainy_(n+1) = f(x_(n+1)). Add the new observation(x_(n+1), y_(n+1))to the datasetD_n. - Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., evaluation budget exhausted, convergence achieved).

Diagram 1: Standard Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Protocol 2: Automated Hyperparameter Selection with BOOST

This protocol, based on the BOOST framework, automates the critical choice of the kernel and acquisition function.

Methodology:

- Data Partitioning: Given an initial dataset

D_n, partition it into a reference subset (used as the initial training data for internal BO runs) and a query subset (treated as the unexplored search space for these internal runs) [19]. - Candidate Preparation: Prepare all possible kernel-acquisition function pairs from a user-defined candidate pool (e.g.,

{RBF, Matern} x {EI, UCB, PI}) [19]. - Internal BO Execution: For each candidate pair

(kernel, acquisition):- Fit a GP using the

kernelto the reference subset. - Run a full internal BO loop, using the

acquisitionfunction to select points from the query subset. - Record the number of iterations required for the internal BO to reach a target performance value [19].

- Fit a GP using the

- Configuration Selection: Select the candidate pair that achieved the target performance in the fewest internal iterations.

- Main Optimization: Proceed with the standard BO loop (Protocol 1) using the selected optimal kernel-acquisition pair for all subsequent expensive evaluations of the true function

f[19].

Diagram 2: BOOST Automated Configuration Workflow

A technical support guide for researchers navigating the balance between exploration and exploitation in Bayesian optimization.

Balancing exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (refining known good areas) is fundamental to effective Bayesian Optimization (BO). For researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development where each function evaluation is costly, quantitatively measuring this balance is crucial. This guide provides practical support for implementing novel exploration metrics in your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the novel methods for quantifying exploration in Bayesian Optimization?

Traditional analysis of acquisition functions often relies on qualitative observation. Recent research introduces two novel quantitative measures for exploration:

- Observation Traveling Salesman Distance (OTSD): This metric quantifies exploration by calculating the total Euclidean distance of the shortest possible path (a "Traveling Salesman" tour) that connects all observation points selected by an acquisition function in the search space. A higher OTSD indicates that the observations are more spread out, signifying greater explorative behavior [23] [6] [24].

- Observation Entropy (OE): This method uses an information-theoretic approach. It computes the empirical differential entropy of the distribution of observation points. A higher entropy value suggests a more uniform (or less clustered) distribution of points, which also corresponds to a higher degree of exploration [23] [6] [24].

These metrics move beyond heuristic assessment, providing a principled foundation for comparing acquisition functions and guiding their design [23] [6].

Why are my acquisition functions not exploring the search space effectively?

Ineffective exploration can stem from several common issues. The table below outlines potential problems and their solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Troubleshooting Guide & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Function Tuning | Overly exploitative parameter settings (e.g., low β in UCB, high ϵ in PI) [3] [4]. |

Systematically increase exploration parameters. For UCB, try a higher β value. For PI, ensure the ϵ parameter is not set too high, which can paradoxically lead to excessive, undirected exploration [3]. |

| Surrogate Model | Over-smoothing or an incorrect prior width in the Gaussian Process [15]. | Re-evaluate your GP kernel and its hyperparameters. A model that is too smooth may underestimate uncertainty in unexplored regions, preventing the AF from selecting points there. |

| Implementation | Inadequate maximization of the acquisition function [15]. | The AF must be optimized effectively to find its true global maximum. Ensure you are using a robust optimizer with multiple restarts to avoid getting stuck in poor local maxima. |

How do I implement OTSD and OE in my experimental workflow?

Implementing these metrics involves calculating them based on the sequence of points selected by your Bayesian Optimization routine.

Workflow Diagram: Integrating Novel Metrics into BO Analysis

Experimental Protocol for Metric Calculation

- Run Bayesian Optimization: Execute your BO routine for a predetermined number of iterations

t, collecting the sequence of observation points{Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚, ..., Xâ‚œ}[24]. - Calculate Observation Traveling Salesman Distance (OTSD):

- Input: The set of observation points

{Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚, ..., Xâ‚œ}. - Method: Solve the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) to find the shortest tour that visits each point exactly once and returns to the origin. The total Euclidean distance of this tour is the OTSD [23] [6].

- Implementation: Use a TSP solver (e.g.,

concordeor heuristic solvers innetworkx). Higher OTSD values indicate more spatial dispersion and higher exploration.

- Input: The set of observation points

- Calculate Observation Entropy (OE):

- Input: The set of observation points

{Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚, ..., Xâ‚œ}. - Method: Compute the empirical differential entropy of the observations. This often involves estimating the underlying probability distribution of the points (e.g., using kernel density estimation) and then calculating the entropy of that distribution [23] [6].

- Implementation: Use statistical libraries (e.g.,

scipy.stats.differential_entropy). Higher entropy indicates a more uniform spread of points.

- Input: The set of observation points

- Analysis: Use OTSD and OE to compare the exploration behavior of different acquisition functions across various benchmark problems. These metrics have been shown to strongly correlate, cross-validating their reliability [24].

What is the relationship between exploration and final performance?

The link between exploration and performance is problem-dependent. Some level of exploration is necessary to escape local optima and discover promising, unexplored regions of the search space [10] [15].

However, the relationship is not linear. Excessive exploration can be wasteful, especially with a limited evaluation budget. The goal is a well-balanced trade-off. Research using OTSD and OE has begun to uncover links between the explorative nature of acquisition functions and their empirical performance, helping to guide the selection of the right AF for a given problem class [23] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential "reagents" or components needed for experiments focused on quantifying exploration in Bayesian Optimization.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate | Provides a probabilistic model of the black-box function, estimating mean and uncertainty (variance) at any point [15] [4]. | The kernel choice (e.g., RBF) and its hyperparameters (lengthscale, amplitude) are critical. An ill-specified GP can misguide the entire BO process [15]. |

| Acquisition Functions (AFs) | Guides the search by balancing the GP's mean prediction (exploitation) and uncertainty (exploration) [3] [4]. | Common AFs include Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Probability of Improvement (PI). Each has a different inherent exploration tendency [23] [24]. |

| Benchmark Problems | Provides a controlled environment to test and compare the exploration metrics and AF performance. | Use a diverse set of synthetic (e.g., Branin, Hartmann) and real-world black-box functions to ensure robust conclusions [24]. |

| Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) Solver | Computational tool required to calculate the Observation Traveling Salesman Distance (OTSD) metric. | For large t, exact solvers may be slow; high-quality heuristic or approximation algorithms are sufficient [23]. |

| Entropy Estimation Library | Computational tool required to calculate the Observation Entropy (OE) metric. | Libraries like scipy in Python offer functions for differential entropy estimation. The choice of kernel and bandwidth for density estimation can influence results [23]. |

| LY456236 | LY456236, CAS:338736-46-2, MF:C16H16ClN3O2, MW:317.77 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lyngbyatoxin B | Lyngbyatoxin B|For Research Use Only | Lyngbyatoxin B is an oxidized derivative of the dermatotoxin Lyngbyatoxin A. This product is for research applications only and is not intended for personal use. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Comparing Acquisition Functions Using Novel Metrics

This protocol allows for a systematic, quantitative comparison of the exploration behavior of different acquisition functions.

Objective: To quantify and compare the exploration characteristics of Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Probability of Improvement (PI) on a standard benchmark function.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Select a benchmark function (e.g., a 2D Branin function). Define a limited evaluation budget (e.g., 50 iterations). Start with an initial design of 5 points via Latin Hypercube Sampling.

- Bayesian Optimization Loop: For each acquisition function (EI, UCB, PI):

- Run the BO algorithm for 50 iterations.

- At each iteration

t, record the selected pointX_t.

- Post-Run Analysis: After completing all runs, for each AF's sequence of 50 points:

- Compute the Observation Traveling Salesman Distance (OTSD).

- Compute the Observation Entropy (OE).

- Comparison: Compare the final OTSD and OE values for each AF. Higher values indicate greater exploration. Correlate these metrics with the final performance (best value found) to analyze the exploration-performance trade-off.

Expected Data and Results

The following table summarizes the type of quantitative data you can expect to collect from the described protocol. This structure allows for easy comparison across different acquisition functions.

| Acquisition Function | Observation TSD (↑ = More Exploration) | Observation Entropy (↑ = More Exploration) | Final Best Value (Performance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCB (β=2.0) | 45.2 | 3.1 | 0.95 |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | 38.7 | 2.8 | 0.97 |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | 32.1 | 2.4 | 0.89 |

| Random Search | 48.5 | 3.3 | 0.75 |

Diagram: OTSD Calculation on a 2D Plane

From Theory to Bench: Acquisition Functions and Advanced BO Strategies

In Bayesian optimization (BO), we aim to find the global optimum of a black-box function that is expensive to evaluate. The core of this process is the acquisition function, which uses the surrogate model (typically a Gaussian Process) to decide where to sample next. It strategically balances exploration (probing regions of high uncertainty) and exploitation (concentrating on areas known to have high performance) [3]. A well-balanced trade-off is crucial for sample-efficient optimization [6]. This guide addresses common questions and issues you might encounter when working with four key acquisition functions: Expected Improvement (EI), Probability of Improvement (PI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and Thompson Sampling.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between how PI and EI quantify the desire to sample a point?

- Probability of Improvement (PI) considers only the likelihood that a point will yield a better result than our current best observation. It does not account for the potential magnitude of that improvement [15] [18]. This can sometimes lead to overly greedy behavior and getting stuck in local optima.

- Expected Improvement (EI) considers both the probability of improvement and the expected amount of improvement. It is the expected value of the improvement function, ( I(x) = \max(f(x) - f(x^+), 0) ), where ( f(x^+) ) is the current best value [18]. This makes it less likely to get stuck and generally more efficient than PI [15].

Q2: How does the UCB acquisition function explicitly control the exploration-exploitation balance?

- The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function has an explicit form: ( \alpha_{UCB}(x) = \mu(x) + \beta \sigma(x) ), where ( \mu(x) ) is the mean prediction (exploitation) and ( \sigma(x) ) is the prediction uncertainty (exploration) [18].

- The parameter ( \beta ) acts as a direct dial between exploration and exploitation [18]:

- Small ( \beta ): The function is dominated by ( \mu(x) ), leading to more exploitation around areas expected to be good.

- Large ( \beta ): The function is dominated by ( \sigma(x) ), leading to more exploration of uncertain regions.

Q3: My Bayesian optimizer is converging to a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration?

- If using UCB: Increase the ( \beta ) parameter to give more weight to the uncertainty term [18].

- If using PI: Introduce or increase the ( \epsilon ) parameter, which acts as a trade-off parameter. A larger ( \epsilon ) encourages more exploration by requiring a new point to be significantly better than the current best to be considered a strong candidate [3].

- If using EI: While EI has no explicit parameter, its inherent balance often makes it more robust to this issue than PI. Ensuring your Gaussian Process model has appropriate lengthscales is also critical [15].

- General Tip: A poorly specified surrogate model can also cause this. An incorrect prior width or over-smoothing in the Gaussian Process can lead to poor performance and local convergence [15].

Q4: In a parallel computing environment, can I still use these standard acquisition functions?

- Standard EI, PI, and UCB are designed for sequential sampling. However, modifications exist for parallel experiments (batch BO). One common paradigm is "fantasy sampling," where you temporarily update the surrogate model with pending evaluations (using a "fantasy" outcome) before selecting the next point in the batch [25]. Advanced methods also include partitioning the design space to propose multiple, diverse points simultaneously [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimizer is overly greedy and gets stuck in local optima.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid convergence to a suboptimal solution; sampling only in a small region. | Using PI with ( \epsilon=0 ) or a very small value [3]. | Switch to the EI acquisition function, which is less prone to this. If using PI, increase the ( \epsilon ) parameter to force more exploration [3]. |

| The model is over-exploiting even with EI or UCB. | The Gaussian Process surrogate model may be over-smoothed (lengthscale too large) or have an incorrect prior width [15]. | Re-tune the GP hyperparameters. Consider using a different kernel or manually adjusting the lengthscale and amplitude to better reflect your beliefs about the function [15]. |

Problem: Optimizer explores too much and is slow to converge.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling appears random; slow improvement in objective function. | Using UCB with a ( \beta ) value that is too high [18]. | Reduce the ( \beta ) parameter in UCB to place more weight on the mean prediction and encourage exploitation [18]. |

| Sampling focuses only on the boundaries of the search space. | The GP prior variance (amplitude) might be set too high, making unexplored regions seem overly promising. | Review and adjust the kernel amplitude and lengthscale of your Gaussian Process to better match the observed data [15]. |

Problem: Inefficient optimization in high-dimensional spaces or with categorical variables.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Performance degrades significantly as the number of dimensions grows. | The "curse of dimensionality"; standard kernels (like RBF) become less effective. | Use a different surrogate model, such as a Bayesian neural network or an ensemble. For mixed variable types, ensure your kernel and optimization strategy can handle categorical variables [15] [25]. |

| The acquisition function itself is difficult to maximize. | The multi-modal nature of acquisition functions becomes harder to navigate in high dimensions. | Employ a robust optimizer for the inner acquisition function maximization loop, such as multi-start gradient ascent or a global optimizer [15]. |

Acquisition Function Comparison & Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the acquisition functions to help you select the right one for your experiment.

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Formulation | Key Mechanism | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | ( \alpha_{PI}(x) = P(f(x) \geq f(x^+) + \epsilon) ) [3] [18] | Maximizes the probability of exceeding the current best by any amount. Controlled by ( \epsilon ). | When evaluations are extremely expensive and a quick, good-enough solution is the goal. Use with caution and a tuned ( \epsilon ). |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | ( \alpha_{EI}(x) = \mathbb{E}[\max(f(x) - f(x^+), 0)] ) [15] [18] | Maximizes the expected amount of improvement over the current best. | General-purpose default choice. Provides a robust balance between exploration and exploitation without extra parameters. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | ( \alpha_{UCB}(x) = \mu(x) + \beta \sigma(x) ) [18] | Explicitly adds a weighted uncertainty term to the mean prediction. Controlled by ( \beta ). | When you need explicit, fine-grained control over the exploration-exploitation trade-off during the experiment. |

| Thompson Sampling | Sample a function from the GP posterior and choose its optimum [15]. | Randomly samples a plausible reward function and acts greedily. | Natural parallelization (batch BO). Simple to implement and effective for selecting multiple points at once. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key components for setting up a Bayesian optimization experiment.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function in the Bayesian Optimization Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | Provides a probabilistic surrogate for the expensive, black-box function. It estimates the mean ( \mu(x) ) and uncertainty ( \sigma(x) ) at any point ( x ) based on prior observations [3]. |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel | A common kernel (covariance function) for the GP. It defines the smoothness and lengthscale of the functions being modeled, determining how observations influence predictions at nearby points [15]. |

| Acquisition Function Optimizer | An algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS, multi-start optimization) used to find the point that maximizes the acquisition function. This is a crucial inner loop in the BO process [15]. |

| Reference Model / Expert Knowledge | In advanced parallel BO, a low-fidelity model or physics-based model can be used to guide the partitioning of the design space, making the search more efficient [25]. |

| MCP110 | MCP110, MF:C33H36N2O3, MW:508.6 g/mol |

| Mdivi-1 | Mdivi-1, CAS:338967-87-6, MF:C15H10Cl2N2O2S, MW:353.2 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Acquisition Functions

To empirically compare the performance of different acquisition functions (EI, PI, UCB) on a test problem, follow this detailed methodology.

- Select a Benchmark Function: Choose a known, multi-modal function with a global optimum, such as a modified Shekel function or a simple function like ( f(x) = \sin(12x) * x + 0.5 * x^2 ) for a 1D demo [26].

- Initialize the Experiment:

- Select 3-5 initial points ( X{train} ) via a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) or uniformly at random.

- Evaluate the benchmark function at these points to get ( y{train} ).

- Configure the Surrogate Model:

- Use a Gaussian Process with an RBF kernel.

- Optimize the GP hyperparameters (lengthscale, amplitude) by maximizing the marginal log-likelihood on the initial data.

- Iterate the Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- For a pre-defined number of iterations (e.g., 20-50):

- Fit the GP model on all current observations ( (X{train}, y{train}) ).

- For each acquisition function being tested (EI, PI, UCB):

- Find the next point ( x{next} ) by maximizing the acquisition function.

- "Evaluate" the benchmark function at ( x{next} ) (this is cheap since it's a known function).

- Record the new best function value found so far.

- For UCB, test different values of ( \beta ) (e.g., 0.1, 1.0, 2.0). For PI, test different ( \epsilon ) values (e.g., 0.01, 0.1).

- For a pre-defined number of iterations (e.g., 20-50):

- Metrics and Analysis:

- Plot the best value found versus the number of function evaluations for each method. The method that reaches the global optimum fastest is the most sample-efficient.

- Use quantitative measures like the observation traveling salesman distance or observation entropy to quantify the exploration characteristics of each method [6].

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the core iterative workflow of a Bayesian optimization experiment.

Logical Diagram of Acquisition Function Decisions

This diagram illustrates the decision-making logic behind the PI, EI, and UCB acquisition functions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the exploration-exploitation trade-off in Bayesian optimization?

In Bayesian optimization, the goal is to find the global optimum of an expensive black-box function with as few evaluations as possible. Exploration involves sampling in regions of the search space where uncertainty is high, aiming to discover new, potentially better optima. Exploitation, conversely, involves sampling in regions where the model already predicts high performance, refining the search around the current best candidate. A successful acquisition function must balance these two competing goals [24] [3].

Q2: Which specific parameters directly control this trade-off?

The balance is explicitly controlled by tunable parameters within acquisition functions. The most common are:

β(beta) in the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function [24] [4].ε(epsilon) in the Probability of Improvement (PI) acquisition function [3].κ(kappa) is another parameter, synonymous withβ, used in UCB [4] [27].ξ(xi) serves a similar purpose in the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function [27].

Q3: How does the β parameter in UCB work?

The UCB acquisition function is defined as α_UCB(x) = μ(x) + β * σ(x), where μ(x) is the predicted mean and σ(x) is the predicted uncertainty at point x [4].

- A larger

βvalue places more weight on the uncertainty term (σ(x)), encouraging exploration by favoring points with high variance [24] [4]. - A smaller

βvalue places more weight on the mean (μ(x)), encouraging exploitation by favoring points predicted to be high-performing [4].

Q4: How does the ε parameter in PI work?

The Probability of Improvement acquisition function selects the point with the highest probability of improving over the current best value by a margin [3]. The ε parameter defines this margin.

- A larger

εvalue forces the algorithm to seek improvement over a higher target, which encourages exploration of more uncertain regions [3]. - A smaller

εvalue (e.g., close to zero) makes the algorithm greedy, as it only looks for any improvement, leading to more exploitation around the current best candidate [3].

Q5: What are common issues when setting these parameters?

- Over-exploration: Setting

β(for UCB) orε(for PI) too high can cause the optimization to jump around uncertain but ultimately unproductive regions for too long, failing to converge on the true optimum [3]. - Over-exploitation: Setting

βorεtoo low can make the algorithm converge too quickly to a local optimum, missing the global solution because it did not explore the space sufficiently [3]. - Problem-dependent optimal values: There is no universal "best" value for these parameters. The optimal setting depends on the specific properties of the black-box function being optimized [4].

Q6: Are there acquisition functions that do not require manual tuning of these parameters?

Yes. Expected Improvement (EI) is a popular acquisition function that automatically balances exploration and exploitation without an explicit scheduling parameter in its most standard form [28]. It considers both the probability of improvement and the magnitude of that improvement [3] [27]. Some modern research also focuses on developing adaptive mechanisms that automatically adjust the trade-off during the optimization process [10].

Parameter Control at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key parameters and their effects.

| Acquisition Function | Control Parameter | Effect of a Larger Parameter Value | Effect of a Smaller Parameter Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | β (or κ) |

Increases exploration [24] [4] | Increases exploitation [4] |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | ε |

Increases exploration [3] | Increases exploitation [3] |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | ξ |

Increases exploration [27] | Increases exploitation [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Exploration

Recent research has introduced quantitative measures to analyze the exploration behavior of acquisition functions, moving beyond qualitative assessment. The following protocol, based on Papenmeier et al. (2025), allows researchers to empirically measure exploration [24] [6].

Objective: To quantify and compare the exploration characteristics of different acquisition functions (e.g., UCB with varying β) on a given black-box optimization problem.

Materials:

- A black-box function to optimize (e.g., a synthetic test function or a hyperparameter tuning task).

- A Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model.

- The acquisition functions under test.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Start with an initial design of points (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sample) to build the initial GP model.

- Bayesian Optimization Loop: Run the Bayesian optimization algorithm for a fixed number of iterations for each acquisition function and parameter setting.

- Data Collection: Record the sequence of observation points

X_obs = {x_1, x_2, ..., x_n}selected by each acquisition function. - Quantification: Calculate exploration metrics on the set

X_obs:- Observation Traveling Salesman Distance (OTSD): Compute the total Euclidean distance of the shortest path (a traveling salesman tour) connecting all observation points. A higher OTSD indicates that points are more spread out, signifying greater exploration [24] [6].

- Observation Entropy (OE): Calculate the empirical differential entropy of the observations. A higher entropy value also indicates a more dispersed set of points and greater exploration [24] [6].

- Analysis: Compare the OTSD and OE values across different acquisition functions and parameter settings. Functions or parameter settings with higher metric values are more explorative.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential computational "reagents" required for experiments in Bayesian optimization exploration.

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate | A probabilistic model that provides a posterior distribution (mean μ(x) and uncertainty σ(x)) over the black-box function given observed data [24] [28]. |

| Acquisition Functions (UCB, PI, EI) | Heuristics that use the GP posterior to decide the next point to evaluate by balancing exploration and exploitation [3] [4] [28]. |

| Synthetic Test Functions | Well-understood benchmark functions (e.g., Branin, Hartmann) used to validate and compare optimization algorithms in a controlled setting. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Task | A real-world task, such as tuning a neural network, where the black-box function is the validation loss/accuracy as a function of hyperparameters [29] [27]. |

| Observation Metrics (OTSD, OE) | Quantitative measures used to assess the level of exploration exhibited by an acquisition function based on its selected points [24] [6]. |

| (+)-Medioresinol | (+)-Medioresinol, CAS:40957-99-1, MF:C21H24O7, MW:388.4 g/mol |

| MK-886 | MK-886, CAS:118414-82-7, MF:C27H34ClNO2S, MW:472.1 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: The optimization run appears to get stuck in a local minimum and fails to find a better global solution.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of over-exploitation. The algorithm is refining its search too aggressively in one region without exploring other promising areas.

Solution:

- For UCB: Systematically increase the

βparameter. If using a fixedβ, try a schedule that starts with a higher value and decreases over time [24]. - For PI: Increase the

εparameter to force the acquisition function to consider points that offer improvement over a higher target, which typically lie in more uncertain regions [3]. - Consider Switching AFs: Try using the Expected Improvement (EI) function, which inherently balances the amount of improvement and its probability, or test newer, adaptive acquisition functions [10] [27].

Problem: The optimization is slow to converge, and evaluations are wasted on clearly poor regions of the search space.

Diagnosis: This indicates over-exploration. The algorithm is spending too many resources reducing global uncertainty instead of focusing on high-performing regions.

Solution:

- For UCB: Decrease the

βparameter to give more weight to the predicted mean [4]. - For PI: Decrease the

εparameter to make the search more greedy, focusing on points with any probability of improvement over the current best [3]. - Validation: Use the quantitative metrics OTSD and OE. If their values are significantly higher for your run compared to a baseline, it confirms excessive exploration [24].

Core Concepts: BATCHIE and the Exploration-Exploitation Balance

BATCHIE (Bayesian Active Treatment Combination Hunting via Iterative Experimentation) is a platform that uses Bayesian active learning to make large-scale combination drug screens tractable. It addresses the fundamental challenge of scale, where the number of possible experiments in a combination screen grows exponentially with the number of drugs, doses, and cell lines involved [30].

The core of the BATCHIE methodology is its Probabilistic Diameter-based Active Learning (PDBAL) criterion. This algorithm selects experiments that are expected to minimize the distance between any two posterior samples after observing the new results. This approach comes with theoretical guarantees for near-optimal experimental designs, ensuring efficient navigation of the vast search space. The goal is to maximally reduce uncertainty about drug combination responses across all cell lines, which directly embodies a principled balance between exploring uncertain regions of the experimental space and exploiting areas that already show promise [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model & Performance | Poor predictive accuracy on unseen combinations [20]. | Incorrect prior width; Over-smoothing; Inadequate acquisition function maximization [20]. | Tune GP hyperparameters; Validate against a held-out test set; Ensure robust maximization of the acquisition function [20]. |

| Optimization performs worse than traditional Design of Experiments (DoE) [31]. | Problem over-complication via high-dimensional feature space; Misalignment between expert knowledge and core optimization goal [31]. | Simplify the problem formulation; Use feature selection to reduce dimensionality; Re-evaluate if added expert knowledge simplifies or complicates the objective [31]. | |

| Algorithm & Design | Algorithm gets stuck in local optima. | Imbalance skewed too heavily towards exploitation [22]. | Switch acquisition function to one favoring more exploration (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound); Adjust the trade-off parameter in the acquisition function [22]. |

| High uncertainty in predictions persists after several batches. | Batches are not sufficiently informative. | Use the PDBAL criterion to ensure each batch maximally reduces global posterior uncertainty [30]. | |

| Experimental & Data | High experimental noise obscuring the signal. | Inherent biological variability; measurement error [22]. | Implement heteroscedastic noise modeling if noise levels vary; Incorporate technical replicates into the experimental design [22]. |

| Integrating data from different experimental fidelities (e.g., docking vs. IC50) [32]. | Unknown or varying correlation between fidelities across the search space [32]. | Use a Multifidelity BO (MF-BO) framework like Targeted Variance Reduction (TVR); Let the surrogate model learn the relationship between fidelities [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does BATCHIE fundamentally differ from standard Bayesian Optimization?

BATCHIE uses an active learning framework aimed at modeling the entire experimental space optimally. In contrast, standard Bayesian Optimization typically seeks to find a single optimizer of an objective function. For objectives like the therapeutic index, individual evaluations in BO might require experiments on combinations across several cell lines, which can be wasteful. BATCHIE leverages all observed experiments, regardless of how many cell lines a combination is tested on, resulting in a globally informative model that can identify many promising candidates, not just one [30].

Q2: We have historical data from previous, smaller screens. Can BATCHIE use this?

Yes, integrating historical knowledge is a powerful way to accelerate Bayesian Optimization. Advanced methods like DeltaBO have been developed for this purpose. It uses a novel uncertainty-quantification approach built on the difference function between the source (historical) and target tasks. When source and target tasks are similar, this can lead to a much faster convergence rate compared to starting from scratch [33].

Q3: What kind of predictive model does BATCHIE use, and can we use our own?

BATCHIE is compatible with any Bayesian model capable of modeling combination drug screen data. The reference implementation uses a hierarchical Bayesian tensor factorization model. This model contains embeddings for each cell line and each drug-dose, and it decomposes the combination response into individual drug effects and interaction terms [30]. The platform is designed to be flexible, allowing integration of other existing or future Bayesian machine learning methods by ensuring they can quantify posterior uncertainty [30].

Q4: Why is my BO algorithm only sampling points at the boundary of the parameter space?

This is a known failure mode sometimes called "boundary oversampling." It indicates that the algorithm's exploration-exploitation balance might be off, often due to high uncertainty at the boundaries of the search space. To remedy this, review and potentially adjust the acquisition function's behavior and ensure the search space is correctly defined based on physically meaningful constraints [31].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a BATCHIE Screen

The following workflow outlines the core steps for running a BATCHIE-driven combination drug screen.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Batch Design:

- The process begins with an initial batch of experiments designed using classical Design of Experiments (DoE) principles to achieve broad coverage of the drug and cell line space [30].

- Practical Note: The size of this batch should be sufficient to provide a baseline for the model.

Experiment Execution:

- The designed combination experiments (e.g., drug A + drug B on cell line X at specific doses) are run in the lab, and the cell viability or other response metrics are measured [30].

Bayesian Model Training:

- The experimental results are used to train a Bayesian probabilistic model. BATCHIE's reference implementation uses a hierarchical Bayesian tensor factorization model [30].

- The model estimates a distribution over drug combination responses for each cell line, providing both a prediction and a measure of uncertainty.

Adaptive Batch Design with PDBAL:

- For all subsequent batches, BATCHIE uses the Probabilistic Diameter-based Active Learning (PDBAL) criterion [30].

- The model's posterior distribution simulates plausible outcomes for candidate experiments. PDBAL selects the batch of experiments that is expected to most significantly reduce the overall posterior uncertainty across the entire experimental space. This ensures every new batch is maximally informative [30].

Iteration and Stopping:

- Steps 2-4 are repeated. The model is updated with each new batch of results, becoming progressively more accurate.

- The loop terminates when the experimental budget is exhausted or the model's posterior has converged to a concentrated distribution, indicating that further experiments may yield diminishing returns.

Hit Prioritization:

- The final, optimally trained model is used to predict the effectiveness of all untested combinations.

- The top-ranked combinations, based on the desired metric (e.g., high therapeutic index, strong synergy), are prioritized for final experimental validation [30].

Signaling and Workflow Diagrams

Logical Workflow of the PDBAL Algorithm

The PDBAL algorithm is the engine that balances exploration and exploitation in BATCHIE.

Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization for Drug Discovery

For projects that incorporate data of different fidelities, the following MF-BO workflow can be integrated.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Screen | Specific Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Library | The set of compounds being tested for combination effects. | A library of 206 drugs was used in the prospective BATCHIE study [30]. |

| Cell Line Panel | A collection of biological models representing the disease. | The BATCHIE study used 16 pediatric cancer cell lines, focusing on sarcomas [30]. |

| Bayesian Model | The probabilistic surrogate that guides experiment selection. | Hierarchical Bayesian Tensor Factorization model [30]. Can be substituted with other Bayesian models. |

| Viability Assay | To measure the cell response (e.g., death or growth inhibition) to drug treatments. | Not specified in results, but common examples include CellTiter-Glo. |

| Docking Software | (For virtual screens) Used as a low-fidelity experiment to predict drug binding. | DiffDock or Autodock Vina can be used [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my Bayesian Optimization perform poorly as I add more variables to my experiment?

This is a classic symptom of the "curse of dimensionality". As the number of dimensions increases, the volume of your search space grows exponentially, making it incredibly difficult for the algorithm to find good solutions with a limited number of experiments. The surrogate model (like a Gaussian Process) becomes less accurate, and the acquisition function struggles to identify promising regions [34] [35]. Furthermore, incorporating irrelevant expert knowledge as additional features can inadvertently create a higher-dimensional, more complex problem that impairs optimization performance [31].

2. My data is very sparse (many zero values). How does this affect my model and what can I do?

Sparse data, common in fields like text mining or user ratings, increases model complexity, storage needs, and processing time. It can make it difficult for models to learn robust patterns [36]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Feature Removal: Use techniques like LASSO regularization or variance thresholds to remove non-informative sparse features [36].

- Densification: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or feature hashing to transform sparse features into a denser, lower-dimensional format [36].

3. When should I use linear vs. non-linear dimensionality reduction methods?

The choice depends on the structure of your data:

- Linear Methods (e.g., PCA): Best when the underlying relationships between variables are linear. PCA is fast and preserves the global data structure but fails to capture complex non-linear patterns [37].

- Non-Linear Methods (e.g., Kernel PCA, t-SNE, UMAP): Essential for capturing complex, non-linear manifolds. Kernel PCA can reveal intricate patterns that PCA misses, while t-SNE and UMAP are powerful for visualizing high-dimensional data by preserving local relationships [37]. The table below provides a detailed comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Best Use Case | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA [37] | Linear | Finds orthogonal directions that maximize variance. | Linearly separable data; pre-processing for other algorithms. | Low (O(n³) for full decomposition). |

| Kernel PCA (KPCA) [37] | Non-linear | Uses the "kernel trick" to perform PCA in a higher-dimensional space. | Capturing complex non-linear structures. | High (O(n³) due to eigen-decomposition of kernel matrix). |

| Sparse KPCA [37] | Non-linear | Approximates KPCA using a subset of data points to improve scalability. | Large datasets where standard KPCA is too slow. | Medium (Depends on subset size m, where m ≪ n). |

| t-SNE [37] | Non-linear | Preserves local neighborhoods and reveals cluster structures. | Data visualization and cluster analysis in 2D or 3D. | High. |

| UMAP [37] | Non-linear | Preserves both local and more of the global data structure. | Visualization of high-dimensional data with complex structures. | High, but often faster than t-SNE. |

4. My BO algorithm keeps sampling at the edges of the parameter space and gets stuck. What's happening?