Modern HPLC Method Development for Pharmaceutical Analysis: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to AI-Driven Optimization

This comprehensive guide explores modern High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method development tailored for pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals.

Modern HPLC Method Development for Pharmaceutical Analysis: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to AI-Driven Optimization

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores modern High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method development tailored for pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals. It systematically covers foundational principles and core concepts of reversed-phase, normal-phase, and ion-exchange chromatography. The article delves into advanced methodological approaches, including Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD), automation, and hyphenated techniques like LC-MS. A dedicated troubleshooting section provides practical solutions for common issues such as peak tailing, pressure anomalies, and baseline noise, supported by predictive maintenance strategies. Finally, the guide outlines rigorous validation protocols per ICH Q2(R2) guidelines and comparative analyses with emerging techniques, empowering scientists to develop robust, compliant, and efficient analytical methods.

HPLC Foundations: Core Principles, Instrumentation, and Separation Modes for Pharmaceutical Analysts

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) stands as a cornerstone technique for the separation, identification, and quantification of complex mixtures. The efficacy of any HPLC method in drug development hinges on a fundamental principle: the differential partitioning of analytes between a mobile phase and a stationary phase [1]. This application note delineates the core theoretical principles of this partitioning behavior and provides a detailed experimental protocol for the simultaneous determination of five COVID-19 antiviral drugs, framing the discussion within the context of HPLC method development for pharmaceutical research. Mastery of these principles empowers scientists to rationally design and optimize robust analytical methods, ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products.

Core Principles: The Partitioning Mechanism

At its core, HPLC separation is governed by the differential interaction of sample components with two immiscible phases [1].

- The Stationary Phase: This phase is fixed in place, typically consisting of solid particles packed into a column. These particles are often modified with specific functional groups (e.g., C18 chains) that define the phase's chemical character [1] [2].

- The Mobile Phase: This is a liquid that is pumped under high pressure through the column, transporting the sample along with it. Its composition can be a single solvent or a mixture, and it can be held constant (isocratic) or changed over time (gradient) [1] [2].

Separation occurs because each component in a mixture has a different affinity for the stationary phase relative to the mobile phase. Molecules with a higher affinity for the stationary phase will be retarded and take longer to elute from the column, while those with a higher affinity for the mobile phase will move through the system more quickly [1]. This continuous distribution process, known as partitioning, is the engine of chromatographic separation.

The Partition Coefficient and Retention Factor

The partitioning behavior of an analyte is quantitatively described by its partition coefficient (K), which represents the equilibrium concentration of the solute in the stationary phase divided by its concentration in the mobile phase [3] [4]. A higher K value indicates a stronger interaction with the stationary phase and a longer retention time.

In practical HPLC, the more directly useful parameter is the retention factor (k), previously known as the capacity factor. It is a dimensionless value that relates the partition coefficient to the volumes of the stationary and mobile phases in the column [4]. It is calculated as:

k = (tR - tM) / tM

where tR is the retention time of the analyte and tM is the void time—the time taken for a non-retained molecule to travel through the column [4]. A retention factor between 1 and 10 is generally considered desirable for a well-resolved peak [4].

Modes of Partition Chromatography

The nature of the stationary and mobile phases determines the primary mode of separation. The most common approach in pharmaceutical analysis is Reversed-Phase (RP) HPLC, which uses a non-polar stationary phase (e.g., C18-bonded silica) and a polar mobile phase (e.g., water-acetonitrile or water-methanol mixtures) [1] [2]. In this mode, more non-polar analytes are retained longer. In contrast, Normal-Phase (NP) HPLC employs a polar stationary phase (e.g., silica) and a non-polar mobile phase, where more polar analytes are retained longer [1].

Diagram: The Principle of Differential Partitioning in Reversed-Phase HPLC

Experimental Protocol: Simultaneous Analysis of Antiviral Drugs

The following validated protocol for the simultaneous determination of five COVID-19 antiviral drugs—favipiravir, molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, remdesivir, and ritonavir—serves as a practical exemplar of reversed-phase HPLC method development and application [5].

This is an isocratic reversed-phase HPLC method with UV detection, optimized for rapid analysis and high resolution of the target active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in pharmaceutical formulations.

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| HPLC System | Standard HPLC equipped with a pump, autosampler, column oven, and UV-Vis detector. |

| Analytical Column | Hypersil BDS C18 (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 µm particle size). C18 provides a non-polar surface for reversed-phase separation. |

| Mobile Phase | Methanol and Water (70:30, v/v). Methanol is an organic solvent that elutes analytes; water is the weak solvent in RPC. |

| pH Adjuster | Ortho-phosphoric acid (0.1%), used to adjust mobile phase pH to 3.0. Controls ionization of analytes for sharper peaks. |

| Analytical Standards | Reference standards of favipiravir, molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, remdesivir, and ritonavir (purity ≥98%). |

| Solvents for Sample Prep | HPLC-grade methanol and/or water for dissolving samples and standards. |

Detailed Chromatographic Conditions

Table: Optimized Chromatographic Parameters for Antiviral Drug Analysis [5]

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Stationary Phase | Hypersil BDS C18 (4.6 x 150 mm, 5 µm) |

| Mobile Phase | Water : Methanol (30:70, v/v) |

| pH | 3.0 (adjusted with 0.1% ortho-phosphoric acid) |

| Flow Rate | 1.0 mL/min |

| Detection Wavelength | 230 nm |

| Injection Volume | 10 µL |

| Column Temperature | Ambient (or controlled per system setup) |

| Run Time | ~ 5 minutes |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Accurately measure 700 mL of HPLC-grade methanol and 300 mL of HPLC-grade water. Mix thoroughly. Add 1 mL of ortho-phosphoric acid to achieve a 0.1% v/v concentration, and adjust the final pH to 3.0. Filter the prepared mobile phase through a 0.45 µm membrane filter and degas by sonication for 10 minutes.

- Standard Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh about 10 mg of each API reference standard into a single 10 mL volumetric flask. Dissolve and make up to volume with methanol to obtain a stock solution with a concentration of approximately 1 mg/mL for each drug. Further dilute with the mobile phase to prepare working standards in the linearity range of 10-50 µg/mL.

- Sample Solution Preparation: For tablet or capsule formulations, accurately weigh and powder a representative number of units. Transfer a portion of the powder equivalent to the weight of one unit into a volumetric flask. Add methanol, sonicate for 15-20 minutes to extract the APIs, then dilute to volume. Centrifuge and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 µm syringe filter before analysis.

- System Equilibration: Install the C18 column and pump the mobile phase through the system at the operational flow rate of 1.0 mL/min until a stable baseline is achieved (typically 30-60 minutes).

- Analysis and Data Acquisition:

- Inject the blank solvent (mobile phase) to confirm no interfering peaks are present.

- Sequentially inject the working standard solutions to establish the calibration curve and system suitability (checking for retention time reproducibility, peak symmetry, and resolution).

- Inject the prepared sample solutions and record the chromatograms.

- Calculation: Quantify the amount of each drug in the sample by comparing the peak area of the analyte in the sample solution to the corresponding calibration curve derived from the standard solutions.

Expected Results and Method Performance

This optimized method is validated to provide baseline separation of all five antiviral drugs with excellent resolution [5]. The method's performance, as per ICH guidelines, meets the following criteria:

Table: Validation Parameters and Expected Chromatographic Profile [5]

| Parameter | Result / Observation |

|---|---|

| Retention Time (tR) Order | Favipiravir (1.23 min) < Molnupiravir (1.79 min) < Nirmatrelvir (2.47 min) < Remdesivir (2.86 min) < Ritonavir (4.34 min) |

| Linearity (Range: 10-50 µg/mL) | Correlation coefficient (r²) ≥ 0.9997 for all five analytes |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) < 1.1% |

| Trueness (% Recovery) | 99.59% - 100.08% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.415 - 0.946 µg/mL |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 1.260 - 2.868 µg/mL |

Discussion: Implications for Pharmaceutical Method Development

The successful application of this protocol underscores several critical aspects of HPLC method development rooted in partitioning principles. The choice of a C18 column and a methanol-water mobile phase is classic for reversed-phase separation of moderately to highly non-polar molecules like the target antivirals [2]. Adjusting the pH to 3.0 with ortho-phosphoric acid is a strategic move to suppress the ionization of acidic or basic functional groups on the analytes, ensuring they are in a single, uncharged form for more predictable partitioning and sharper peak shape [2].

The isocratic elution with a 70:30 methanol-to-water ratio was sufficient to elute all compounds within 5 minutes while maintaining resolution, demonstrating that a simple, robust method can be developed through rational optimization of the partitioning conditions. This approach aligns with modern trends that leverage digital twins and AI to predict retention and optimize methods with minimal experimentation, as highlighted in recent conferences [6]. Understanding the core principles of differential partitioning allows scientists to make such rational decisions during method development, ultimately leading to efficient, reliable, and transferable analytical methods for ensuring drug quality.

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) remains a cornerstone technology for the separation, identification, and quantification of compounds in complex mixtures. The evolution toward Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has brought about significant advancements in pressure capabilities, column technology, and detection systems, enabling faster analyses with superior resolution and sensitivity [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these modern components is crucial for developing robust analytical methods that meet stringent regulatory requirements. This application note details the core components of contemporary HPLC/UHPLC systems, provides structured experimental protocols for their evaluation, and discusses their critical role in pharmaceutical method development within a research thesis framework.

Core Components of a Modern HPLC/UHPLC System

Ultra-High-Pressure Pump Systems

The pump is the cornerstone of any HPLC/UHPLC system, responsible for delivering the mobile phase at a constant and precise flow rate against the high backpressure generated by modern sub-2 µm particles. Contemporary systems demonstrate significant pressure capability variations, which directly influence the choice of column particle size and analysis speed.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern HPLC/UHPLC Pump Capabilities

| System Model | Max Pressure (bar) | Max Flow Rate (mL/min) | Key Features | Suitability for Pharmaceutical Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimadzu i-Series [8] | 1,015 (70 MPa) | Not Specified | Compact, integrated design; eco-friendly operation | High-performance method development and routine analysis |

| Knauer Azura HTQC [8] | 1,240 | Up to 10 | Configured for high-throughput quality control | Ideal for QC labs requiring short cycle times |

| Thermo Fisher Vanquish Neo [8] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Tandem direct injection workflow for parallel operations | Excellent for high-throughput screening in drug discovery |

| Waters Alliance iS Bio [8] | 830 (12,000 psi) | Not Specified | Bio-inert design; MaxPeak HPS technology | Essential for analyzing metal-sensitive biomolecules |

| Agilent 1290 Infinity III [8] | 1,300 | Up to 5 | Includes level sensing and maintenance software | Versatile for R&D and demanding multi-method applications |

Modern pumps are often part of sophisticated binary or quaternary systems that generate highly accurate gradients. A critical parameter in gradient methods is the dwell volume—the volume from the point of mixing to the column inlet. Differences in dwell volume between systems can cause significant retention time shifts and altered selectivity, making it a paramount consideration during method transfer between instruments in pharmaceutical development [9].

Advanced Column Technologies

The column is the heart of the separation, where interactions between the stationary phase and analytes occur. Recent innovations have focused on enhancing efficiency, peak shape, and chemical stability.

Table 2: Recent Innovations in HPLC/UHPLC Column Technology

| Column Product | Particle Technology | Stationary Phase | Key Attributes | Ideal Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halo 120 Ã… Elevate C18 [10] | Superficially Porous Particles (SPP) | C18 | Wide pH stability (2-12); high-temperature stability | Robust method development for APIs and impurities |

| Evosphere C18/AR [10] | Monodisperse Fully Porous Particles (MFPP) | C18 and Aromatic Ligands | Higher efficiency; separates oligonucleotides without ion-pairing reagents | Analysis of complex biomolecules like oligonucleotides |

| Aurashell Biphenyl [10] | SPP | Biphenyl | Hydrophobic, π–π, dipole, and steric mechanisms | Metabolomics, isomer separations, polar compound analysis |

| Halo Inert [10] | SPP with Passivated Hardware | Various (C18, etc.) | Prevents adsorption to metal surfaces | Analysis of phosphorylated compounds and metal-sensitive analytes |

| Raptor C8 [10] | SPP | C8 (Octylsilane) | Faster analysis with C18-like selectivity | General-purpose analysis of acidic to slightly basic compounds |

A major trend is the use of inert or biocompatible hardware to prevent analyte adsorption and improve recovery for sensitive compounds like pharmaceuticals that chelate metals [10]. Furthermore, the transfer of methods from traditional fully porous particles (FPP) to modern superficially porous particles (SPP) can yield significant savings in solvent consumption and analysis time while maintaining resolution [9].

Advanced Detection Systems

Detection is the final critical step, and modern systems offer unparalleled sensitivity and specificity.

- Vacuum Ultraviolet (VUV) Detectors: The Hydra Multi-Channel VUV detector operates in the 120-240 nm range, where all molecules absorb light. It provides universal detection with high spectral selectivity across 12 bands, follows Beer's Law for linearity, and is invaluable for identifying compounds with poor UV chromophores [8].

- Charged Aerosol Detectors (CAD): Celebrating 20 years of development, CAD is a near-universal detector renowned for its quantitative capabilities. Its response is independent of a compound's chemical structure, making it ideal for quantifying analytes without UV chromophores, such as carbohydrates, lipids, and excipients in pharmaceuticals. Key settings like evaporation temperature and the power function application are critical for versatility and linearity [11].

- Mass Spectrometric (MS) Detectors: MS remains the gold standard for sensitivity and compound identification. New systems like the Sciex 7500+ MS/MS offer enhanced resilience and up to 900 MRM/sec capability for quantifying vast numbers of compounds in a single run [8]. High-resolution instruments like the ZenoTOF 7600+ utilize Zeno Trap and Electron Activated Dissociation (EAD) for advanced structural elucidation in proteomics and biomarker research [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: System Suitability and Dwell Volume Determination

1. Purpose: To verify the performance of a modern UHPLC system and characterize its dwell volume, ensuring it is suitable for intended pharmaceutical analyses and facilitating robust method transfer.

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for System Characterization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC Grade Water | Mobile phase component | Minimizes baseline noise and system contamination. |

| UHPLC Grade Acetonitrile | Organic mobile phase modifier | Low UV cutoff and high purity for sensitive detection. |

| Dwell Volume Test Mix | A solution of an unretained, UV-absorbing compound. | Typically 0.1% acetone or caffeine in water [9]. |

| C18 Reference Column | A standardized column for performance testing. | e.g., 50 x 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 µm FPP or SPP C18. |

| System Suitability Standard | A mixture of known compounds to assess performance. | Contains caffeine, phenol, and related compounds in mobile phase. |

3. Procedure:

- Dwell Volume Measurement:

- Set the system to 100% aqueous mobile phase (e.g., water) at 1.0 mL/min and a low UV wavelength (e.g., 210 nm).

- Perform a blank injection.

- Create a gradient method that immediately switches to 100% organic (e.g., acetonitrile) containing 0.1% acetone after injection.

- Inject the dwell volume test mix and run the gradient method.

- The dwell volume is calculated as: Dwell Volume (mL) = Retention Time of the Step Gradient Center (min) × Flow Rate (mL/min) [9].

- System Performance Check:

- Reconstitute the system suitability standard in the starting mobile phase.

- Inject the standard onto the C18 reference column using a specified gradient method (e.g., 5-90% acetonitrile in water over 10 minutes).

- Evaluate the resulting chromatogram for parameters like peak asymmetry, theoretical plates, and retention time reproducibility.

4. Data Analysis: Compare the measured dwell volume to the value specified in the target method for transfer. For system performance, ensure that asymmetry factors are between 0.8-1.5, theoretical plates meet the column manufacturer's specifications, and retention time RSD is <0.5%.

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for characterizing a UHPLC system.

Protocol: Method Transfer from HPLC to UHPLC

1. Purpose: To successfully transfer and validate an existing HPLC method to a modern UHPLC platform, leveraging smaller particle sizes and higher pressures to reduce analysis time and solvent consumption while maintaining data quality.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Analytical Standard: The target Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and its known impurities.

- Column Equivalency Tools: Utilize tools based on the Hydrophobic Subtraction Model (HSM) to identify UHPLC columns with selectivity equivalent to the original HPLC column [9].

- Mobile Phase Buffers: Identical to the original method, but filtered through 0.2 µm membranes.

3. Procedure:

- Column Selection: Use HSM-based column comparison tools to select a UHPLC column (e.g., SPP, 2.7 µm) that is equivalent in selectivity to the original HPLC column (e.g., FPP, 5 µm) [9].

- Scaling Calculations: Calculate the new UHPLC method parameters to maintain the same linear velocity and gradient slope. Key formulas include:

- Flow Rate (UHPLC) = Flow Rate (HPLC) × [Particle Size (HPLC) / Particle Size (UHPLC)]²

- Gradient Time (UHPLC) = Gradient Time (HPLC) × [Column Volume (UHPLC) / Column Volume (HPLC)] × [Flow Rate (HPLC) / Flow Rate (UHPLC)]

- Dwell Volume Adjustment: Account for the difference in dwell volume between the original and new systems by adding an isocratic hold at the start of the gradient or adjusting the gradient start time [9].

- Method Execution: Perform the analysis on the UHPLC system using the scaled method parameters and the selected equivalent column.

4. Data Analysis: Compare chromatograms from the original and transferred methods. Critical quality attributes include resolution of the critical pair, tailing factor of the main peak, and overall run time. The transfer is successful if all system suitability criteria are met.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and consumables critical for modern HPLC method development in pharmaceutical research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Development

| Category | Specific Item | Function & Importance in Pharmaceutical Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Stationary Phases | Halo 120 Ã… Elevate C18 [10] | Provides robust performance across wide pH (2-12) and temperature ranges, ideal for method development. |

| Evosphere C18/AR [10] | Enables separation of challenging biomolecules like oligonucleotides without ion-pairing reagents. | |

| Halo Inert [10] | Passivated hardware minimizes metal-analyte interactions, crucial for accurate analysis of metal-sensitive compounds. | |

| Mobile Phase Additives | MS-Grade Acids (e.g., Formic Acid) | Provides low-UV-cutoff ion-pairing for optimal MS sensitivity in proteomics and metabolomics. |

| High-Purity Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) | Essential for controlling pH and ionic strength, impacting retention and selectivity of ionizable APIs. | |

| Calibration & QC | System Suitability Test Mixes | Validates column and instrument performance against predefined criteria before analytical runs. |

| Data Analysis Tools | Hydrophobic Subtraction Model (HSM) Tools [9] | Quantifies column selectivity differences, enabling rational, science-based column selection and method transfer. |

| 1H-Isoindole-1,3-diamine | 1H-Isoindole-1,3-diamine, CAS:53175-37-4, MF:C8H9N3, MW:147.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,6-Dichloroisoquinoline | 3,6-Dichloroisoquinoline |Supplier | 3,6-Dichloroisoquinoline (≥98%) is a chemical building block for pharmaceutical research. This product is for research and further manufacturing use only, not for human use. |

Modern HPLC and UHPLC systems represent a significant evolution from their predecessors, driven by ultra-high-pressure pumps, advanced column particle technology, and sophisticated detection systems. For the pharmaceutical researcher, a deep understanding of these components—including the impact of dwell volume, the selectivity of modern stationary phases, and the capabilities of inert hardwar—is fundamental to developing robust, transferable, and efficient analytical methods. The integration of AI and machine learning for method development, as highlighted at recent conferences like HPLC 2025, further promises to streamline this complex process [6]. By leveraging the protocols and component knowledge outlined in this application note, scientists can effectively utilize modern HPLC technology to accelerate drug development and ensure product quality.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) serves as a cornerstone analytical technique throughout pharmaceutical drug development and quality control. Selecting the appropriate separation mode is critical for achieving optimal resolution, accuracy, and efficiency in analyzing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and detecting impurities. This application note provides a detailed comparison of four fundamental HPLC separation modes—Reversed-Phase, Normal-Phase, Ion-Exchange, and Size-Exclusion Chromatography—within the context of pharmaceutical analysis. Each technique offers unique selectivity and application suitability based on the physicochemical properties of the analytes. The content is structured to guide researchers and drug development professionals in method development, providing not only theoretical comparisons but also practical protocols, current trends, and visualization tools to inform strategic separation choices for small molecules and biopharmaceutical products.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

The core mechanism of each chromatographic mode exploits different physicochemical properties of analytes to achieve separation. Understanding these principles is a prerequisite for effective method development in pharmaceutical analysis.

Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RPC) is the most prevalent mode for analyzing small molecule pharmaceuticals. It separates compounds based on hydrophobicity using a non-polar stationary phase (typically C18 or C8 bonded silica) and a polar mobile phase (e.g., water-acetonitrile or water-methanol mixtures). Hydrophobic molecules interact more strongly with the stationary phase and are thus retained longer [12] [13]. Its versatility makes it suitable for a wide range of APIs, impurity profiling, and stability-indicating methods [14].

Normal-Phase Chromatography (NPC), in contrast, utilizes a polar stationary phase (e.g., silica) and a non-polar mobile phase (e.g., hexane or chloroform with ethyl acetate or isopropanol). Separation is based on analyte polarity, with polar compounds interacting more strongly with the stationary phase and eluting later [12] [15]. NPC is particularly well-suited for separating lipophilic compounds, geometric isomers, and analytes with poor aqueous solubility [12] [15].

Ion-Exchange Chromatography (IEX) separates ionic or ionizable compounds based on their charge. The stationary phase contains charged functional groups (cationic or anionic) that interact with oppositely charged analytes. Elution is typically achieved by increasing the ionic strength or shifting the pH of the mobile phase [16]. IEX is indispensable for characterizing charge variants of biotherapeutics, such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and for analyzing ionic impurities [17] [16].

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) separates molecules based on their hydrodynamic volume or size in solution. The stationary phase contains porous particles; smaller molecules can enter the pores and are delayed, while larger molecules are excluded from the pores and elute first. A key application in biopharmaceuticals is the quantitation of protein aggregates, which is critical for assessing product safety and efficacy [18].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of HPLC Separation Modes

| Feature | Reversed-Phase (RPC) | Normal-Phase (NPC) | Ion-Exchange (IEX) | Size-Exclusion (SEC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Mechanism | Hydrophobicity [13] | Polarity (H-bonding, dipole-dipole) [12] [15] | Electrostatic charge [16] | Molecular size/Hydrodynamic volume [18] |

| Stationary Phase | Non-polar (C18, C8) [13] | Polar (Silica, Amino, Diol) [15] | Charged (Cationic or Anionic) [16] | Porous (Silica or Polymer) [18] |

| Mobile Phase | Polar (Water + Organic Solvent) [13] | Non-polar (Organic Solvents) [15] | Aqueous Buffer [16] | Aqueous Buffer [18] |

| Elution Order | Polar first, Non-polar last [12] | Non-polar first, Polar last [12] | Weakly charged first, Strongly charged last | Large first, Small last [18] |

| Primary Pharma Applications | API assay, Impurity profiling, Dissolution testing [14] | Isomer separation, Lipid analysis [15] | mAb charge variant analysis, Ion impurity testing [17] [16] | Protein aggregation, Oligomeric state [18] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for selecting an appropriate separation mode based on analyte properties:

Detailed Techniques and Protocols

Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RPC)

Principles and Pharmaceutical Relevance RPC is the workhorse of pharmaceutical HPLC due to its robust nature, high resolution, and excellent compatibility with a wide range of APIs and related substances. The separation is governed by hydrophobic interactions, making it ideal for most small organic molecules with some degree of hydrophobicity [13]. Modern trends focus on developing high-throughput methods using superficially porous particles (SPP) and UHPLC instrumentation to reduce analysis time and solvent consumption [14].

Detailed Protocol: Universal Gradient Method for Multiple NCEs This protocol is adapted from a published universal method for the assay of multiple New Chemical Entities (NCEs), demonstrating the high-throughput capabilities of modern RPC [14].

- Column: Waters Cortecs C18+ (50 mm x 3.0 mm, 2.7 µm). The C18+ phase provides superior peak shape for basic analytes.

- Mobile Phase A: 0.05% Formic acid in water.

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile.

- Gradient Program:

- 5% B to 60% B over 2.0 min

- 60% B to 95% B over 0.5 min

- Hold at 95% B for 0.3 min

- Re-equilibrate at 5% B for 0.8 min

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40 °C

- Detection: UV at 220 nm (or MS-compatible)

- Injection Volume: 1 µL

Method Notes: This fast, ballistic gradient is ideal for high-throughput screening and in-process control. For stability-indicating methods requiring higher peak capacity, the gradient time can be extended to 10 minutes, which can increase peak capacity (Pc) from approximately 100 to 300 [14]. An alternative mobile phase A, such as 20 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.7), can be used for better buffering capacity and pH control for critical separations.

Normal-Phase Chromatography (NPC)

Principles and Pharmaceutical Relevance NPC separates compounds based on adsorption to a polar stationary phase. It is particularly valuable for analyzing very non-polar compounds that are poorly retained in RPC, for separating positional and geometric isomers which have different polar interaction potentials, and for natural product isolation [12] [15]. A significant drawback is its sensitivity to trace water, which can deactivate the stationary phase and alter retention times.

Detailed Protocol: Separation of Phospholipid Classes This protocol exemplifies the use of NPC for the separation of complex, polar lipids, a common application in pharmaceutical excipient analysis and lipid-based drug delivery systems [15].

- Column: Silica gel column (e.g., 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: Utilize a ternary gradient or isocratic mixture of non-polar and polar organic solvents. A typical example is a mixture of n-hexane, isopropanol, and a small percentage of water or acid/buffer (e.g., 5-10 mM ammonium acetate). The exact proportions must be optimized for the specific lipid classes of interest.

- Elution Mode: Isocratic or gradient elution, where the polarity is increased over time by raising the concentration of the more polar solvent (e.g., isopropanol).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Column Temperature: Ambient or 30 °C

- Detection: Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD) or Mass Spectrometry (MS), as many lipids lack strong UV chromophores.

Method Notes: Ensure all solvents are anhydrous and use a sealed solvent system to prevent atmospheric moisture from affecting the method's reproducibility. Column reactivation cycles with anhydrous solvents may be necessary if performance declines [15].

Ion-Exchange Chromatography (IEX)

Principles and Pharmaceutical Relevance IEX is critical for the analysis of charged molecules. In the development of biotherapeutics like monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), IEX is the premier technique for resolving and quantifying charge variants (e.g., deamidated, sialylated, or glycated species) that can impact stability and biological activity [16]. Recent trends include the effective use of pH gradients and coupling with mass spectrometry for variant identification.

Detailed Protocol: Charge Variant Analysis of a Monoclonal Antibody This protocol outlines a standard analytical method for profiling the charge heterogeneity of a mAb [16].

- Column: Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) column (e.g., 250 mm x 4.0 mm, 5 µm polymeric or hybrid bead-based column).

- Mobile Phase A: 10-20 mM Sodium phosphate buffer, pH ~6.0.

- Mobile Phase B: Mobile Phase A + 0.5 M Sodium chloride (NaCl).

- Gradient Program: A shallow linear gradient from 0% to 40-50% B over 25-30 minutes is typical.

- Flow Rate: 0.8 - 1.0 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 25 - 30 °C

- Detection: UV at 280 nm

- Sample Preparation: The mAb sample should be dialyzed or diluted into Mobile Phase A to eliminate external salt effects.

Method Notes: Method development should focus on optimizing the buffer pH, which dictates the net charge on the protein, and the gradient slope to achieve the desired resolution of acidic and basic variants. The use of hybrid organic/inorganic particles can reduce undesirable secondary interactions with surface silanols [16].

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Principles and Pharmaceutical Relevance SEC is a non-adsorptive technique where separation is driven by entropy. It is predominantly used in the biopharmaceutical industry for the quantitation of protein aggregates and fragments [18]. Monitoring aggregates is a regulatory requirement, as they can impact product efficacy and potentially induce immunogenic responses. The separation is ideally performed under non-denaturing conditions to preserve the native quaternary structure.

Detailed Protocol: Aggregate Analysis of a Therapeutic Protein This protocol describes a standard quality control (QC) method for quantifying high molecular weight (HMW) aggregates and low molecular weight (LMW) fragments in a protein drug substance or product [18].

- Column: Diol-coated hybrid organic/inorganic SEC column (e.g., 300 mm x 7.8 mm, 1.7 - 5 µm). The diol coating minimizes ionic and hydrophobic interactions.

- Mobile Phase: 100-200 mM Sodium phosphate or Sodium chloride buffer, pH 6.8, containing 0.02% sodium azide (if applicable). The high ionic strength is critical to suppress any non-size exclusion interactions.

- Elution Mode: Isocratic.

- Flow Rate: 0.5 - 1.0 mL/min (optimized for resolution)

- Column Temperature: 20 - 25 °C (controlled temperature is essential for reproducibility)

- Detection: UV at 214 nm or 280 nm

- Injection Volume: 10 - 20 µL of a 1-2 mg/mL protein solution.

Method Notes: The column should be calibrated with a set of standard proteins of known molecular weight to confirm the separation range. The use of sub-2 µm particles in UHPLC-SEC formats can significantly reduce run times while maintaining resolution [18].

Advanced Applications and Data Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the correct materials is fundamental to successful method development. The table below lists key reagents and their functions for each chromatographic mode.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Development

| Separation Mode | Essential Materials | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase | C18/C8 Columns (e.g., Cortecs C18+) [14] | Hydrophobic stationary phase for primary retention. |

| Acetonitrile & Methanol [19] | Organic modifiers to control elution strength. | |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid/Formic Acid [14] | Ion-pairing/additives to suppress analyte ionization and improve peak shape. | |

| Normal-Phase | Silica/Diol/Amino Columns [15] | Polar stationary phase for adsorption-based separation. |

| n-Hexane, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate [15] | Non-polar organic solvents to control elution strength. | |

| Isopropanol, Methanol [15] | Polar modifiers to adjust mobile phase strength in NP-HPLC. | |

| Ion-Exchange | SCX/SAX Columns [16] | Charged stationary phase for separation based on electrostatic interactions. |

| Sodium/Potassium Phosphate Buffers [16] | To create and control mobile phase pH and ionic strength. | |

| Sodium Chloride [16] | Salt for gradient elution by competing with analytes for stationary phase charges. | |

| Size-Exclusion | Diol-bonded Hybrid Particles [18] | Hydrophilic, inert stationary phase to minimize non-specific binding. |

| Phosphate Buffers with ~150 mM NaCl [18] | High ionic strength mobile phase to shield against ionic interactions with pores. | |

| Protein Molecular Weight Standards [18] | For column calibration and determination of molecular size. | |

| KadlongilactoneF | KadlongilactoneF, MF:C30H38O7, MW:510.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Methoxybutane-2-thiol | 1-Methoxybutane-2-thiol | 1-Methoxybutane-2-thiol (C5H12OS) is a chemical building block for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or personal use. |

Integrated Workflows and Orthogonal Methods

In modern pharmaceutical analysis, especially for complex molecules like biotherapeutics, a single chromatographic mode is often insufficient for comprehensive characterization. Orthogonal methods, which employ different separation mechanisms, are required to confirm results and gain a deeper understanding of product attributes.

A powerful example is the two-dimensional coupling of SEC with RPC. SEC can be used in the first dimension to separate a protein drug from its aggregates. Each fraction can then be automatically transferred to a second RPC column, which separates the monomers and aggregates based on hydrophobicity, potentially revealing variants that are not distinguishable by size alone. Similarly, IEX is frequently coupled directly to Mass Spectrometry (MS). While this requires volatile mobile phases (e.g., ammonium salts instead of sodium phosphate) and careful flow adjustment, it allows for the direct identification of the chemical modifications (e.g., deamidation, oxidation) responsible for the observed charge variants [16]. Affinity chromatography, though not a core mode discussed here, is another critical orthogonal technique, often used for selective extraction or depletion of specific targets like glycoproteins or abundant serum proteins before further analysis [20].

The following diagram illustrates a typical analytical workflow for a biopharmaceutical, integrating multiple separation techniques:

The strategic selection of an HPLC separation mode is a foundational decision in pharmaceutical method development. Reversed-Phase Chromatography remains the most versatile and widely applied technique for small molecule drug analysis. Normal-Phase Chromatography offers unique selectivity for non-polar compounds and isomers. For the burgeoning field of biopharmaceuticals, Ion-Exchange and Size-Exclusion Chromatography are indispensable for characterizing critical quality attributes like charge heterogeneity and protein aggregation.

This application note provides a framework for selection, detailed protocols for implementation, and highlights the growing importance of using these techniques in orthogonal workflows, often coupled with powerful detectors like mass spectrometry. As the industry advances with new modalities such as gene therapies and complex antibody-drug conjugates, the continued evolution and clever application of these core separation modes will remain vital to ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of pharmaceutical products.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) stands as a cornerstone technique in pharmaceutical analysis, essential for drug development, quality control, and regulatory compliance. The performance of any chromatographic method is fundamentally dictated by the choice of column technology. In recent years, innovations in column design have dramatically enhanced separation efficiency, speed, and sensitivity. This application note focuses on three pivotal technologies shaping modern HPLC: fully porous sub-2-µm particles, core-shell (superficially porous) particles, and monolithic columns. Framed within the context of HPLC method development for pharmaceutical research, this document provides a structured comparison, detailed application protocols, and visual guides to assist scientists in selecting and implementing the optimal column technology for their analytical challenges.

The pursuit of higher efficiency and faster separations has driven the evolution of column packings from large, fully porous particles to advanced materials engineered for performance.

Sub-2-µm Fully Porous Particles: These are the smallest of the traditional fully porous packings. Their key advantage is the very short diffusion path for analytes, which significantly reduces band-broadening and leads to high peak efficiency. However, this comes at the cost of very high backpressure, necessitating specialized Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) instrumentation capable of operating at pressures up to 1200–1300 bar [21] [22]. Their small particle size and narrow pore frits also make them more susceptible to clogging from complex samples [23].

Core-Shell Particles: These particles feature a solid, non-porous core surrounded by a thin, porous outer shell. This architecture is the key to their performance. The solid core limits the depth of pore penetration, drastically shortening the path for analyte diffusion and mass transfer. This results in a dramatic reduction in band-broadening (the C-term in the van Deemter equation) and significantly higher efficiency, especially at higher flow rates [21] [24]. Because they are typically larger than sub-2-µm particles (e.g., 2.6-2.7 µm), they generate much lower backpressure, allowing near-UHPLC performance on conventional HPLC systems with 400-600 bar pressure limits [21] [24] [23].

Monolithic Columns: Instead of a bed of packed particles, monolithic columns consist of a single, continuous porous solid (typically silica or polymer) permeated by a network of macropores (flow-through channels) and mesopores (providing surface area). This bimodal pore structure creates a highly permeable scaffold, enabling very high flow rates with exceptionally low backpressure [25] [26]. This makes them ideal for rapid separations and high-throughput applications, including the analysis of large biomolecules like viruses, nucleic acids, and proteins [25] [27]. Recent innovations focus on functionalized monoliths (e.g., with antibodies, aptamers, or molecularly imprinted polymers) for highly selective online sample preparation and extraction [26].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key HPLC Column Technologies

| Characteristic | Sub-2-µm Porous Particles | Core-Shell Particles | Monolithic Columns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Particle/Structure Size | < 2 µm | 2.6 - 2.7 µm (e.g., 1.7µm core + 0.5µm shell) [21] | Continuous bed with ~2µm macropores [26] |

| Typical Operating Pressure | Very High (up to 1200-1300 bar) [21] | Moderate (400 - 600 bar) [24] [23] | Low [25] [26] |

| Separation Efficiency | Very High | Very High (comparable to sub-2µm porous particles) [21] | Good to High (excels for fast flow rates) |

| Best Suited For | Ultrafast separations on UHPLC systems | High-efficiency separation of small molecules on HPLC/UHPLC systems [21] | Fast separations, large biomolecules (proteins, viruses, nucleic acids) [25] [27] |

| Instrument Requirements | UHPLC system | Standard HPLC or UHPLC system [21] | Standard HPLC system |

| Key Advantage | Maximum efficiency and speed | High efficiency with lower backpressure | Very high flow rates with minimal backpressure |

The following workflow diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate column technology based on analytical requirements and instrument capabilities.

Application Notes in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Application Note AN-101: Fast Analysis of Pharmaceutical Tablets using Core-Shell Technology

Objective: To demonstrate a rapid and efficient quality control method for the separation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and related impurities in a tablet formulation using a core-shell column on a conventional HPLC system.

Background: Core-shell columns are exceptionally well-suited for pharmaceutical quality control labs that require high-throughput analysis without the capital investment for UHPLC instrumentation. Their high efficiency results in superior peak capacity and resolution, which is critical for separating complex mixtures of APIs and their degradants [21] [24].

Key Results: A method transferring a legacy separation from a 5µm fully porous column to a 2.6µm core-shell C18 column can reduce analysis time by up to 70% while maintaining or improving resolution. The backpressure remains below 300 bar, allowing use on standard HPLC equipment [21].

Application Note AN-102: Selective Sample Preparation using Functionalized Monoliths

Objective: To utilize an online molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) monolith for the selective extraction and quantification of a specific drug metabolite from human plasma.

Background: Analyzing trace compounds in complex biological matrices requires selective sample clean-up. Functionalized monoliths, with their high permeability and customizable selectivity, are ideal for online Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) coupled with LC, minimizing manual handling and improving reproducibility [26].

Key Results: Implementation of an online MIP-monolith SPE method for cocaine in plasma achieved the necessary detection limits using only 100 nL of sample and an overall solvent consumption in the order of a microliter per sample. The selective extraction simplified the extract composition to the point that a subsequent analytical separation was not required [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol P-101: Fast Separation of Small Molecules on a Core-Shell Column

This protocol describes the method development and execution for the rapid separation of a small molecule drug and its potential impurities using a C18 core-shell column.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Protocol P-101

| Item | Function / Specification | Example (Brand) |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC System | Standard HPLC instrument capable of 400 bar and low-dispersion. | Agilent 1260 Infinity II, Shimadzu Nexera |

| Analytical Column | Core-Shell C18 column, 2.6 µm, 100 x 3.0 mm or 150 x 4.6 mm. | Phenomenex Kinetex, Waters Cortecs, Agilent Poroshell |

| Mobile Phase A | Aqueous buffer (e.g., 10 mM Ammonium Formate, pH 3.0). | MS-grade water with additive |

| Mobile Phase B | Organic solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile, HPLC grade). | HPLC-grade Acetonitrile |

| Standard Solution | Drug substance and impurity standards dissolved in diluent. | Prepared in water:ACN (90:10, v/v) |

| Sample Vials | Low-volume inserts (e.g., 250 µL) to minimize extra-column volume. | Polypropylene vials with inserts |

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Equip the HPLC system with a low-dispersion kit if available. Use minimal length of tubing with 0.005-inch internal diameter and a low-volume UV detector flow cell (e.g., 1 µL) [21] [23].

- Initial Conditions:

- Column: C18 core-shell, 100 x 3.0 mm, 2.6 µm.

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 35 °C.

- Detection: UV at 254 nm.

- Injection Volume: 2 µL.

- Mobile Phase: (A) Water with 0.1% Formic Acid; (B) Acetonitrile.

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 10 minutes.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the column with initial mobile phase composition for at least 5 column volumes (approx. 3-4 minutes) before the first injection.

- System Suitability Test: Inject a standard mixture of the drug and its impurities. Calculate plate count (should be > 150,000 plates/m), tailing factor (< 1.2), and resolution between the critical pair (> 1.5) [24].

- Method Optimization: If resolution is insufficient, adjust gradient slope (e.g., 5% B to 95% B over 15 minutes) or temperature (e.g., 40-45 °C). The low backpressure of core-shell columns allows for increased flow rates (e.g., 1.5-2.0 mL/min) to further reduce run time without exceeding pressure limits.

- Sample Analysis: Inject prepared samples and quantify against a calibrated standard.

Protocol P-102: Online SPE-LC/MS for Biomolecule Analysis using a Monolithic Column

This protocol outlines the use of a functionalized monolithic column for the selective online extraction and LC/MS analysis of a large biomolecule, such as an oligonucleotide or protein.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Protocol P-102

| Item | Function / Specification | Example (Brand) |

|---|---|---|

| 2D-LC or Online SPE System | System capable of column switching and multi-port valves. | Any modern 2D-LC system |

| Extraction Column | Functionalized monolithic column (e.g., Affinity, MIP). | Lab-made MIP monolith in capillary [26] |

| Analytical Column | Wide-pore SEC or reversed-phase column for biomolecules. | Ultra-wide pore SEC column [27] |

| Mobile Phase (Loading) | Aqueous buffer compatible with the extraction mechanism (e.g., PBS). | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) |

| Mobile Phase (Elution) | Solvent that disrupts analyte-sorbent interaction (e.g., ACN with 0.1% TFA). | MS-compatible eluent |

| Biological Sample | Clarified plasma, serum, or cell lysate. | Centrifuged and diluted as needed |

Procedure:

- System Configuration: Set up an online SPE-LC/MS system. The monolithic extraction column is placed in the sample loop position of a 2-position/6-port switching valve. The analytical column is in the main flow path.

- Extraction Phase (Valve in Load Position):

- Perload the monolithic column with loading buffer.

- Inject the processed biological sample (e.g., 10 µL of diluted plasma) onto the monolithic column using the loading pump with an aqueous buffer at a high flow rate (e.g., 100 µL/min). Matrix components are washed to waste while the target biomolecule is selectively retained.

- Elution and Transfer (Valve in Inject Position):

- Switch the valve to place the monolithic column in line with the analytical column and MS detector.

- A gradient from the analytical pump elutes the retained biomolecule from the monolith and transfers it directly to the analytical column for separation.

- Separation and Detection:

- Re-equilibration: After elution, switch the valve back to the load position and re-equilibrate both the monolithic and analytical columns for the next run.

The following diagram illustrates the fluidic path and logical sequence of the online SPE-LC/MS protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful implementation of advanced column technologies requires attention to both the column itself and the supporting instrumental components. The following table lists key considerations for the chromatographer's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Toolkit for Implementing Advanced Column Technologies

| Toolkit Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Low-Dispersion HPLC System | Instrument with minimal extra-column volume (injector, tubing, detector cell) is critical to preserve the high efficiency generated by narrow peaks from modern columns [21] [23]. |

| Narrow-Bore Connection Tubing | Tubing with 0.005-inch or smaller internal diameter is essential to reduce band broadening before and after the column [24]. |

| Low-Volume Detector Flow Cell | A flow cell with a volume ≤ 1 µL is required to accurately detect the very narrow peaks produced without artificial peak broadening [21] [23]. |

| MS-Compatible Mobile Phase Additives | High-purity, volatile additives (e.g., ammonium formate, trifluoroacetic acid) are necessary for reliable LC/MS detection, especially in proteomics and metabolomics [27]. |

| Column Oven | Maintaining a stable and precise column temperature is crucial for reproducible retention times, especially when using high flow rates or method transfer [21]. |

| 1,3-Di(pyren-1-yl)benzene | 1,3-Di(pyren-1-yl)benzene, MF:C38H22, MW:478.6 g/mol |

| 4-Biphenylyl disulfide | 4-Biphenylyl disulfide, CAS:19813-92-4, MF:C24H18S2, MW:370.5 g/mol |

The strategic selection of column technology is a critical determinant of success in pharmaceutical HPLC method development. Core-shell particles offer an outstanding balance of high efficiency and moderate operating pressure, making them a versatile first choice for most small molecule applications on existing HPLC infrastructure. Sub-2-µm fully porous particles provide the ultimate in separation speed and resolution but require a significant investment in UHPLC instrumentation and are more demanding to maintain. Monolithic columns, particularly when functionalized, open up powerful paradigms for high-throughput and selective analysis of large biomolecules and complex biological samples. By understanding the intrinsic characteristics and optimal application domains of each technology, pharmaceutical scientists can develop robust, efficient, and fit-for-purpose analytical methods that accelerate drug development and ensure product quality.

In high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method development for pharmaceutical analysis, the successful separation of complex mixtures hinges on a fundamental understanding of key molecular properties of the analytes. Among these, acid dissociation constant (pKa), partition coefficient (Log P), and overall hydrophobicity are paramount. These properties directly govern the interaction between analytes, the mobile phase, and the stationary phase, thereby controlling retention, selectivity, and peak shape [28] [29]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on advanced HPLC method development, provides a detailed examination of these properties. It offers structured experimental data, practical protocols, and contemporary toolkits to enable researchers to rationally design and optimize robust chromatographic methods.

Core Molecular Properties: Definitions and Chromatographic Impact

The interplay of molecular properties presents both challenges and opportunities in method development. For instance, the simultaneous analysis of a five-drug combination—Aceclofenac, Paracetamol, Phenylephrine HCl, Cetirizine HCl, and Caffeine—exemplifies this complexity. Their physicochemical properties span a broad range: pKa values from 2.9 to 10.4 and Log P values from -0.07 to 4.88 [28]. This diversity necessitates a strategic approach to mobile phase and stationary phase selection to achieve baseline separation for all components.

Table 1: Molecular Properties of a Five-Drug Combination Model

| Drug Substance | pKa | Log P | Key Property Consideration for HPLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aceclofenac (AFC) | 3.44 (acidic) | ~4.88 | Highly hydrophobic, acidic; retention strongly influenced by mobile phase pH. |

| Paracetamol (PCM) | 9.38 (weakly acidic) | 0.46 | Relatively polar; requires weak elution conditions. |

| Phenylephrine HCl (PPN) | 9.69 (basic) | -0.70 to -0.69 | Highly polar, basic cation at low pH; prone to silanol interactions. |

| Cetirizine HCl (CZN) | 3.58, 7.74 (zwitterionic) | 0.86 to 2.98 | Zwitterionic; retention behavior is highly dependent on pH, which dictates its net charge. |

| Caffeine (CFN) | ~14.0 (neutral) | -0.07 | Neutral compound; retention governed primarily by hydrophobic interactions. |

The Role of pKa and Ionization

The pKa of a molecule indicates the pH at which half of the molecules are ionized. In reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC), the ionization state of an analyte is critical because the uncharged, neutral form is significantly more retained on the hydrophobic stationary phase than its charged counterpart [29]. Controlling the mobile phase pH is therefore a powerful tool for modulating retention and selectivity. For a mixture containing ionizable compounds, the pH should be selected to suppress the ionization of most analytes to ensure adequate retention, or to create differences in ionization states to improve resolution [28]. For example, a buffer pH of 5.8 was strategically used to optimize the separation of Erastin and Lenalidomide in a recent study [30].

Lipophilicity Metrics: Log P and Log D

- Log P: Defined as the logarithm of the partition coefficient of the unionized compound between octanol and water. It represents the intrinsic lipophilicity of a molecule [31] [32].

- Log D: Defined as the logarithm of the distribution coefficient at a specific pH, accounting for all ionized and unionized species present. Log D provides a more accurate picture of a compound's apparent lipophilicity under the chromatographic conditions used [29] [32].

The relationship between Log P and Log D is governed by the pH of the environment and the analyte's pKa. For a monoprotic acid, the equation is: Log D = Log P - log(1 + 10^(pH - pKa)) [29]. This equation highlights that for an acidic compound, as the pH increases above its pKa, ionization increases and Log D decreases. The inverse is true for basic compounds. This principle is directly applicable to predicting how a change in mobile phase pH will affect an analyte's retention time [29].

Hydrophobicity and Retention Mechanism

Hydrophobicity drives the primary retention mechanism in RP-HPLC—the partitioning of analytes into the non-polar stationary phase. Analytes with higher hydrophobicity (higher Log P/D) will have longer retention times [28] [33]. The challenge in separating complex mixtures lies in the fact that the elution order of compounds is not governed by a single property but by the combined effect of pKa, Log P, and the specific chemistry of the stationary phase. The use of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles provides a systematic framework to navigate this complexity, ensuring the development of robust and reliable methods [28] [30].

Experimental Protocol: HPLC Method Development for Multi-Component Formulations

This protocol outlines a systematic, AQbD-based approach for developing a stability-indicating HPLC method for a five-drug combination, based on a published study [28].

Materials and Equipment

- HPLC System: Alliance HPLC system (Waters) with Photodiode-Array (PDA) detector.

- Software: Empower 2.0 for data acquisition; Design-Expert for AQbD-based optimization.

- Column: Waters X-Terra RP-18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm). This column provides a stable base for method development.

- Chemicals: HPLC-grade solvents (ethanol, phosphate buffer components), reference standards of all five Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Risk Assessment and Scouting Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP). Identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) such as mobile phase pH, organic modifier ratio, and gradient profile. Use a scouting gradient to assess the initial separation profile of the mixture.

Step 2: Systematic Optimization via Design of Experiments (DoE)

- Factors: Buffer pH (e.g., 2.9-4.1), ethanol ratio in mobile phase (e.g., 25-45%), and gradient time.

- Responses: Retention time of the last eluting peak, resolution between critical peak pairs, and peak tailing factor.

- Design: A Central Composite Design can be employed to model the relationship between factors and responses efficiently.

Step 3: Method Validation Validate the final method as per ICH Q2(R2) guidelines for:

- Linearity: Over a specified range for each analyte (e.g., R² > 0.995).

- Accuracy: Via recovery studies (e.g., 98-102%).

- Precision: Both repeatability and intermediate precision (%RSD < 2%).

- Specificity: Confirm resolution from forced degradation products.

Step 4: Forced Degradation Studies Stress the sample under acidic, basic, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic conditions. Inject the stressed samples to demonstrate the stability-indicating nature of the method, confirming that the analyte peaks are well-resolved from degradation products [28].

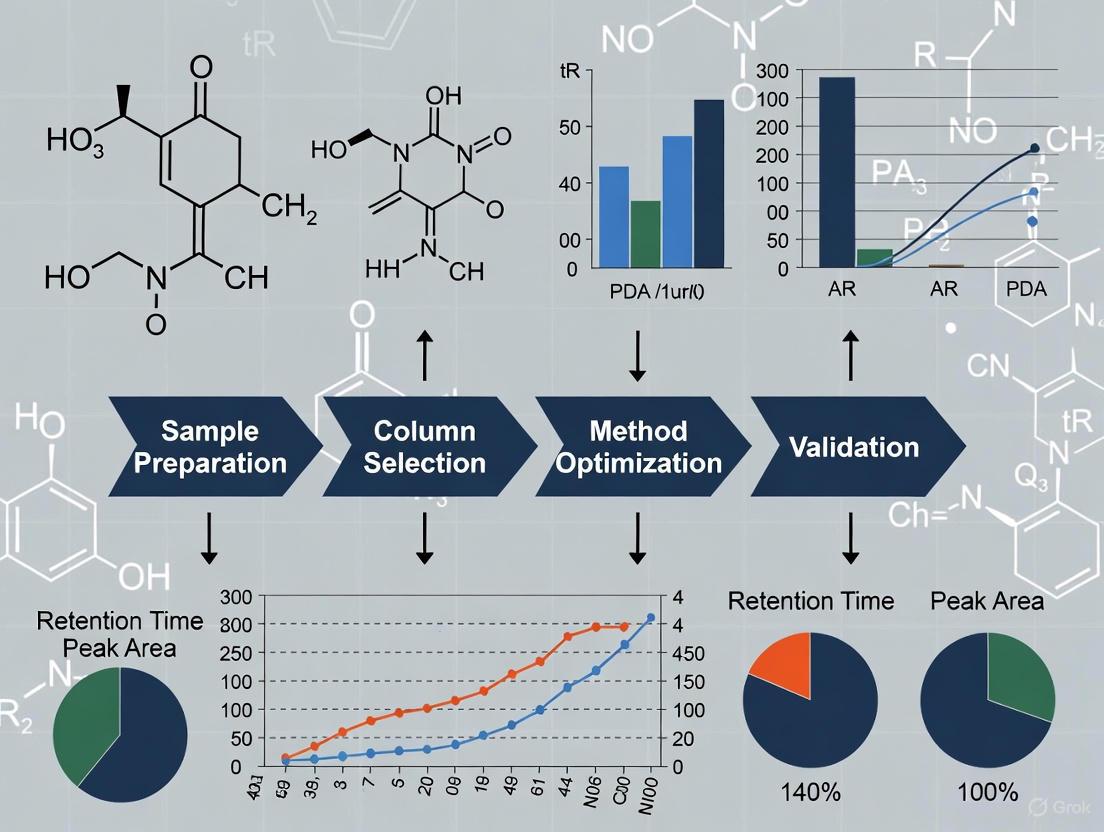

Diagram 1: HPLC Method Development Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced HPLC

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| RP-18 Column | Standard C18 stationary phase for general reverse-phase separations. | Waters X-Terra RP-18, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm [28]. |

| Biocompatible/Inert Column | For metal-sensitive compounds (e.g., phosphorylated analytes), improves peak shape and recovery. | Halo Inert, Restek Inert HPLC Columns [10]. |

| Phenyl-Hexyl Column | Provides alternative selectivity via π-π interactions with aromatic analytes. | Halo 90 Å PCS Phenyl-Hexyl [10]. |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | A common volatile buffer for LC-MS compatibility, usable across a range of pH. | e.g., 10 mM, pH adjusted with formic acid or ammonia [30]. |

| Triethylamine (TEA) | Mobile phase additive to mask residual silanols on silica columns, improving peak shape for basic compounds. | e.g., 0.1% v/v in buffer [34]. |

| Ethanol | A greener alternative to acetonitrile as an organic modifier. | HPLC grade [28]. |

| 5-Ethynyl-2-nitropyridine | 5-Ethynyl-2-nitropyridine|RUO | |

| MappiodosideA | MappiodosideA, MF:C28H38N2O11, MW:578.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The rational design of HPLC methods in pharmaceutical analysis is a science-driven process. A deep understanding of the target analytes' pKa, Log P, and hydrophobicity allows researchers to move beyond empirical "trial-and-error" approaches. By leveraging this knowledge within an AQbD framework and utilizing modern chromatographic tools, scientists can efficiently develop robust, stability-indicating methods that ensure product quality and patient safety. This systematic approach is indispensable for analyzing increasingly complex pharmaceutical formulations, such as multi-drug combinations.

Advanced HPLC Method Development: AQbD, Automation, and Multi-Attribute Method Applications

Implementing Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) for Robust Method Development

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) represents a systematic, scientific, and risk-based framework for analytical method development that ensures quality is built into methods rather than merely tested. Originating from Quality by Design (QbD) principles applied to pharmaceutical manufacturing, AQbD has emerged as a transformative approach for developing robust, reproducible, and fit-for-purpose analytical procedures, particularly in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method development for pharmaceutical analysis [35]. Unlike traditional trial-and-error approaches, AQbD emphasizes proactive development, deep methodological understanding, and continuous improvement throughout the analytical method lifecycle [35] [36].

The fundamental distinction between traditional and AQbD approaches lies in their foundational philosophy. Traditional method development often relies on repetitive, univariate experimentation with limited understanding of parameter interactions, potentially resulting in methods vulnerable to minor operational variations. In contrast, AQbD employs structured experimentation, multivariate analysis, and quality risk management to identify and control Critical Method Parameters (CMPs), thereby establishing a Method Operable Design Region (MODR) within which method performance remains guaranteed [37] [36]. This paradigm shift enhances method robustness, reduces out-of-specification (OOS) results, and provides regulatory flexibility throughout the method lifecycle [35] [38].

The AQbD Workflow: A Step-by-Step Framework

Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) serves as the cornerstone of AQbD implementation, defining the intended purpose, performance requirements, and quality criteria for the analytical method [36]. As stated by regulatory perspectives, "An analytical target profile that is parallel to QTPP is the first step in QbD. It outlines the purpose of the process for developing analytical methods and connects the outcomes to QTPP" [35]. The ATP translates analytical needs into measurable performance characteristics, typically derived from ICH Q2(R1) validation parameters but incorporating probabilistic performance standards [36].

For impurity profiling methods in pharmaceutical analysis, the ATP should specify requirements for selectivity, sensitivity, accuracy, and precision. For example, in developing a UHPLC method for CPL409116 impurity profiling, researchers defined the ATP to include "a robust, selective, and specific method" with "LOQ on the reporting threshold level of 0.05%" to meet regulatory requirements for impurity control [37]. A well-constructed ATP for a potency assay might state: "The procedure must be able to accurately and precisely quantify drug substance in film-coated tablets over the range of 70%-130% of the nominal concentration with accuracy and precision such that reported measurements fall within ± 3% of the true value with at least 95% probability" [36].

Identifying Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) and Risk Assessment

Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) represent the measurable performance characteristics that define method quality and must be controlled to ensure the method meets its ATP [37]. For chromatographic methods, typical CMAs include resolution between critical pairs, peak symmetry, tailing factor, theoretical plate count, and retention time [37] [39]. In the CPL409116 method development, researchers specifically identified "the resolution between the peaks (≥2.0) and peak symmetry of analytes (≥0.8 and ≤1.8)" as their primary CMAs [37].

Risk assessment forms the foundation for identifying and prioritizing Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) that potentially impact CMAs. As outlined in ICH Q9, quality risk management employs various tools including Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams, Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), and risk estimation matrices [35]. These tools systematically evaluate potential sources of variation in method parameters, materials, instruments, and environments, categorizing factors as high, medium, or low risk based on their severity, occurrence, and detectability [35]. The output of risk assessment guides subsequent experimentation by focusing resources on high-risk factors.

Design of Experiments (DoE) and Optimization

Design of Experiments (DoE) represents the systematic approach for evaluating multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously to efficiently understand their relationship with CMAs [35]. Through carefully constructed experimental designs, analysts can model the response surface and identify optimal method conditions while minimizing experimental burden. Common DoE approaches include screening designs (full or fractional factorial) to identify significant factors, followed by response surface methodologies (Box-Behnken, Central Composite Designs) for optimization [37] [39].

In the development of a stability-indicating HPLC method for acetylsalicylic acid, ramipril, and atorvastatin in polypills, researchers employed a Box-Behnken response surface methodology to optimize three CMPs: "buffer pH, gradient slope and % CH3OH initial content" [40]. Similarly, for the quantification of Picroside II, a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was implemented to optimize chromatographic factors using Design Expert software [39]. The power of DoE lies in its ability to mathematically model complex relationships and predict method performance across the experimental space, enabling science-based decision-making rather than empirical optimization.

Establishing the Method Operable Design Region (MODR)

The Method Operable Design Region (MODR) represents the multidimensional combination and interaction of CMPs where method performance consistently meets CMA requirements defined in the ATP [37] [35]. Establishing the MODR provides operational flexibility, as changes within this region do not require revalidation, enhancing method lifecycle management [38]. The MODR is typically generated through Monte Carlo simulations based on the mathematical models derived from DoE, calculating the probability of meeting CMA specifications across the experimental space [37] [40].

For the favipiravir RP-HPLC method development, "The method operable design region (MODR) and the robust set point were calculated using a Monte Carlo simulation method using the MODDE 13 Pro software" [41]. The MODR represents the region where the method is robust to minor, expected variations in operational parameters, thereby minimizing the risk of OOS results during routine application. Documenting the MODR provides regulatory agencies with evidence of method understanding and control, facilitating post-approval changes within the defined region [38].

Control Strategy and Lifecycle Management

A control strategy comprises systematic procedures and monitoring activities to ensure the method remains in a state of control throughout its lifecycle [36]. This includes system suitability tests (SST) derived from the MODR boundaries, defined calibration frequencies, and preventative maintenance schedules. As noted in AQbD principles, "The management approach is not a onetime procedure used in the method development stage; it could change in different stages during the method lifecycle" [35].

The control strategy is directly informed by the knowledge gained during method development, with SST parameters specifically selected based on their sensitivity to method robustness [36]. For chromatographic methods, this typically includes resolution between critical pairs, tailing factor, theoretical plates, and retention time reproducibility. The enhanced method understanding provided by AQbD enables a risk-based control strategy focused on truly critical aspects rather than arbitrary specifications, providing both operational flexibility and reliability [38].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing AQbD for HPLC Method Development

Protocol for AQbD-Based HPLC Method Development

Step 1: Define ATP and CMAs

- Convene a multidisciplinary team to define the ATP based on method intent and regulatory requirements

- Document the ATP with measurable performance criteria: "The procedure must be able to accurately and precisely quantify drug substance in film-coated tablets over the range of 70%-130% of the nominal concentration with accuracy and precision such that reported measurements fall within ± 3% of the true value with at least 95% probability" [36]

- Identify CMAs (e.g., resolution ≥2.0 between all peaks, peak symmetry 0.8-1.8, LOQ ≤0.05%) [37]

Step 2: Conduct Risk Assessment

- Brainstorm potential CMPs using an Ishikawa diagram with categories: instrument, method, materials, environment, analyst, and measurement [35]

- Employ an FMEA to score factors based on severity, occurrence, and detectability

- Prioritize high-risk factors for subsequent DoE (e.g., mobile phase pH, stationary phase, gradient profile, column temperature) [37] [41]

Step 3: Perform Screening Experiments

- Select an appropriate screening design (e.g., fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman) to evaluate the significance of high-risk CMPs

- For a method with 5-6 potential CMPs, a resolution IV fractional factorial design provides a balance between run numbers and ability to detect interactions

- Execute experiments in randomized order to avoid bias

- Analyze results to identify statistically significant factors (p < 0.05) affecting CMAs

Step 4: Optimize Using Response Surface Methodology

- For 2-4 significant factors, implement a Box-Behnken or Central Composite Design

- Include center points to estimate curvature and experimental error

- For example, in the development of a method for favipiravir, a d-optimal experimental design was used to study "three high level risk factors (X1: ratio of solvent, X2: pH of the buffer, X3: column type)" and their impact on "peak area (Y1), retention time (Y2), tailing factor (Y3) and theoretical plates count (Y4)" [41]

- Fit mathematical models to the data and evaluate model adequacy (R², adjusted R², prediction error)

Step 5: Establish MODR Using Monte Carlo Simulation

- Define CMA acceptance criteria based on ATP requirements

- Perform Monte Carlo simulations (≥10,000 iterations) to predict the probability of meeting all CMA criteria across the experimental space [37] [41]

- Identify the MODR as the region where probability exceeds a predetermined threshold (typically ≥90% or ≥95%)

- Verify the MODR boundaries through confirmatory experiments

Step 6: Develop Control Strategy

- Define system suitability tests based on MODR boundaries

- Establish controls for material attributes (e.g., column qualification, reagent specifications)

- Document operational ranges for CMPs within the MODR

- Implement a method performance monitoring program

Protocol for AQbD-Based Method Validation

- Specificity: Demonstrate separation from placebo, impurities, and degradation products using forced degradation studies under acid, base, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic conditions [40] [39]

- Linearity and Range: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentration levels across the specified range (e.g., 50-150% of target concentration). Calculate correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and residual sum of squares [39]

- Accuracy: Perform recovery studies at three levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150%) with triplicate determinations. Report percent recovery and RSD [39]

- Precision:

- Repeatability: Six replicate preparations at 100% concentration, RSD ≤ 2% [39]

- Intermediate precision: Different day, analyst, and instrument; RSD ≤ 3%

- Robustness: Deliberately vary CMPs within MODR (e.g., flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, temperature ±2°C, mobile phase composition ±2%) and demonstrate CMA compliance [37]

- Solution Stability: Monitor standard and sample solutions over 24-48 hours at room temperature and refrigerated conditions; report percent change

Case Studies and Applications

Pharmaceutical Impurity Profiling

The implementation of AQbD for the development of a UHPLC method for CPL409116 impurity profiling demonstrates the comprehensive application of AQbD principles [37]. Researchers employed a full fractional design 2² for screening, followed by a fractional factorial design 2(4−1) for robustness testing, examining eight different stationary phases and mobile phase pH ranging from 2.6 to 6.8 [37]. The MODR was generated using Monte Carlo simulations, and the method was successfully validated per ICH Q2(R1). This systematic approach enabled the development of a robust method for quantifying nine impurities with LOQ at 0.05% for all impurities, successfully controlling the purity of CPL409116 during large-scale synthesis for preclinical and clinical trials [37].

Stability-Indicating Methods

In the development of a stability-indicating HPLC method for acetylsalicylic acid, ramipril, and atorvastatin in fixed-dose polypills, AQbD principles were applied with Box-Behnken response surface methodology for optimization [40]. The MODR was approved by establishing a robust zone using Monte Carlo simulation and capability analysis [40]. The method demonstrated excellent performance with determination coefficients (R²) higher than 0.9939, good precision (RSD < 7.7%), and accuracy expressed as average percent relative recovery between 91.4-106.7%. The forced degradation studies confirmed the stability-indicating capability, with successful quantification of the APIs in commercially available Trinomia capsules [40].

Green AQbD Approaches

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly embracing the integration of AQbD with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles to develop environmentally sustainable methods [42]. This approach employs eco-friendly solvents such as ethanol and water instead of traditional acetonitrile or methanol, while maintaining analytical performance through structured AQbD development [42]. Greenness assessment tools including AGREE, GAPI, AMGS, and Analytical Eco-Scale provide quantitative metrics for environmental impact. For instance, a recent AQbD-driven RP-HPLC method for quantifying irbesartan in chitosan nanoparticles employed an ethanol-sodium acetate mobile phase and achieved high green scores while maintaining regulatory compliance [42].

Table 1: AQbD Application Case Studies in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Pharmaceutical Analyte | AQbD Elements | Analytical Technique | Key Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPL409116 (impurity profiling) | Full factorial design, MODR with Monte Carlo simulations | UHPLC-UV | LOQ at 0.05% for all nine impurities; Validated per ICH Q2(R1) | [37] |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, ramipril, atorvastatin | Box-Behnken design, MODR with Monte Carlo simulations | HPLC-UV | R² > 0.9939; Precision RSD < 7.7%; Applied to commercial polypill | [40] |

| Picroside II | Box-Behnken design, Risk assessment | RP-HPLC | Linear range 6-14 μg/mL; Precision RSD < 2%; Specific with forced degradation | [39] |

| Favipiravir | d-optimal design, MODR with Monte Carlo simulations | RP-HPLC-UV/DAD | Precision RSD < 2%; Greenness score >75; Successfully applied to tablets | [41] |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for AQbD Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function in AQbD | Examples/Specifications | Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|