Overcoming Specificity and Selectivity Challenges in Pharmaceutical Analytical Methods

This article provides a comprehensive framework for pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals to address critical challenges in analytical method specificity and selectivity.

Overcoming Specificity and Selectivity Challenges in Pharmaceutical Analytical Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals to address critical challenges in analytical method specificity and selectivity. It explores foundational principles distinguishing these concepts, outlines advanced methodological approaches for complex modalities like biologics, offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common failure modes, and details validation protocols aligned with ICH Q2(R2) and evolving regulatory standards. By integrating Quality-by-Design principles, lifecycle management, and emerging assessment tools, the content delivers actionable insights for developing robust, reliable analytical procedures that ensure product quality and patient safety.

Demystifying Specificity and Selectivity: Core Principles and Regulatory Expectations

Official IUPAC Definitions

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) provides precise, distinct definitions for specificity and selectivity in analytical chemistry.

Specificity

IUPAC defines specificity as a term that "expresses qualitatively the extent to which other substances interfere with the determination of a substance according to a given procedure." Specific is considered to be the ultimate of selective, meaning that no interferences are supposed to occur [1]. Specificity is the ideal state for an analytical method, representing absolute freedom from interference.

Selectivity

IUPAC provides both qualitative and quantitative definitions for selectivity:

- (Qualitative): "The extent to which other substances interfere with the determination of a substance according to a given procedure" [2].

- (Quantitative): "A term used in conjunction with another substantive (e.g. constant, coefficient, index, factor, number) for the quantitative characterization of interferences" [2].

Key Conceptual Relationship

The fundamental relationship between these concepts is that specificity represents the ultimate degree of selectivity [1] [3]. While selectivity can be graded (a method can be more or less selective), specificity is an absolute characteristic - few methods truly achieve it [3].

Table 1: IUPAC Definitions and Key Characteristics

| Term | Definition | Gradable? | Quantifiable? | Practical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ultimate freedom from interference by other substances | No | No | Absolute characteristic; ideal state |

| Selectivity | Extent to which other substances interfere with analyte determination | Yes | Yes (with coefficients, factors, etc.) | Can be graded and characterized quantitatively |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Common Issues and Solutions

Q1: Our method shows good recovery in pure standard solutions but fails with real samples. What could be causing this?

A: This typically indicates inadequate selectivity due to matrix effects. The method may be susceptible to interference from sample matrix components that weren't present in your pure standard solutions [3].

- Solution: Conduct comprehensive matrix matching during validation. Use standard addition methods to identify and compensate for matrix effects. Consider implementing additional clean-up steps or chromatographic separation to improve selectivity [4].

Q2: During method transfer between laboratories, we're getting different results for the same samples. Where should we focus our investigation?

A: This often stems from differences in method robustness rather than fundamental issues with specificity or selectivity [4].

- Solution:

- First, verify that both labs are using identical system suitability test parameters

- Conduct a ruggedness test examining the impact of small, deliberate variations in method parameters (pH, temperature, flow rate, etc.)

- Ensure both instruments are properly calibrated and maintained

- Document all procedural details to identify any subtle differences in execution [4] [5]

Q3: How can we demonstrate our method is truly specific for a degradation product that co-elutes with the main peak?

A: Achieving true specificity for co-eluting compounds requires orthogonal techniques [3].

- Solution: Implement hyphenated techniques like LC-MS/MS or LC-DAD to confirm peak purity. Use spectral comparison or mass spectral confirmation to demonstrate that the method can distinguish between the analyte and closely eluting impurities [6] [3]. Forced degradation studies can help validate the method's ability to separate and quantify degradation products from the active compound [4].

Q4: Our immunoassay was described as "specific" but we're seeing cross-reactivity with metabolites. Was this claim inaccurate?

A: Yes, this represents a common misuse of terminology. Immunological methods relying on antigen-antibody interactions are often described as specific, but they frequently show cross-reactivity and should more accurately be defined as selective rather than specific [3].

- Solution: Characterize the degree of cross-reactivity with known structurally similar compounds and report the method as selective with defined cross-reactivity percentages. Update method documentation to accurately reflect the selective nature of the assay [3].

Advanced Troubleshooting Scenarios

Q5: We need to adapt a selective method for a new matrix. What's the systematic approach?

A: Matrix adaptation requires re-evaluation of key validation parameters:

- Specificity: Test for new potential interferences in the novel matrix

- Selectivity: Evaluate whether the same degree of discrimination is maintained

- Accuracy and Precision: Conduct spike-recovery experiments in the new matrix

- Limit of Detection/Quantification: Determine if method sensitivity is affected by matrix components [4] [5]

Systematically document all experiments to demonstrate the method remains fit-for-purpose in the new context.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Method Selectivity

Objective: To experimentally demonstrate the selectivity of an analytical method against potentially interfering substances.

Materials:

- Analytical instrument (HPLC, GC, LC-MS, etc.)

- Analyte standard

- Potential interfering substances (related compounds, metabolites, matrix components)

- Appropriate solvents and reagents

Procedure:

Prepare individual solutions of the analyte and each potential interfering substance at concentrations expected in actual samples.

Analyze each solution separately to determine retention times/positions and detection characteristics.

Prepare mixture solutions containing the analyte and each potential interferent in combination.

Analyze the mixtures using the same method parameters.

Compare chromatograms/spectra to ensure:

Acceptance Criteria:

- Analyte peak purity meets established thresholds (e.g., >99%)

- Interference from any individual substance is <5% of analyte response

- Method can clearly distinguish analyte from closely related compounds

Protocol 2: Challenge Test for Specificity

Objective: To rigorously challenge a method's specificity using stressed samples.

Materials:

- Drug substance or product samples

- Equipment for stress conditions (heating, UV light, acid/base, oxidizing agents)

- Analytical instrumentation

- Reference standards

Procedure:

Subject samples to stress conditions:

- Acidic hydrolysis (e.g., 0.1N HCl, room temperature or elevated temperature)

- Basic hydrolysis (e.g., 0.1N NaOH, room temperature or elevated temperature)

- Oxidative degradation (e.g., 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, room temperature)

- Thermal degradation (e.g., 70°C for 2 weeks)

- Photolytic degradation (e.g., UV light per ICH Q1B) [4]

Analyze stressed samples alongside unstressed controls and placebo formulations (if applicable).

Evaluate chromatographic separation between:

- Analyte peak and degradation products

- Analyte peak and placebo components

- All peaks of interest from each other

Use orthogonal detection (e.g., DAD or MS) to confirm peak purity and identity.

Data Interpretation:

- The method demonstrates specificity if it can accurately quantify the analyte despite the presence of degradation products and matrix components

- All degradation products are satisfactorily resolved from the analyte peak

- Peak purity tests confirm homogeneous analyte peaks [4]

Table 2: Validation Parameters for Specificity and Selectivity Assessment

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Acceptance Criteria | Relevance to Specificity/Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Purity | Photodiode array or mass spectrometric detection | Peak homogeneity >99% | Direct measure of specificity |

| Resolution | Chromatographic separation of critical pairs | R ≥ 1.5 between analyte and closest eluting interference | Quantitative expression of selectivity |

| Forced Degradation | Stress testing under various conditions | Analyte stability-indicating; degradation products resolved | Demonstrates specificity against known and unknown impurities |

| Matrix Interference | Comparison of standards in solvent vs. matrix | Signal difference <5% | Measures selectivity against sample matrix |

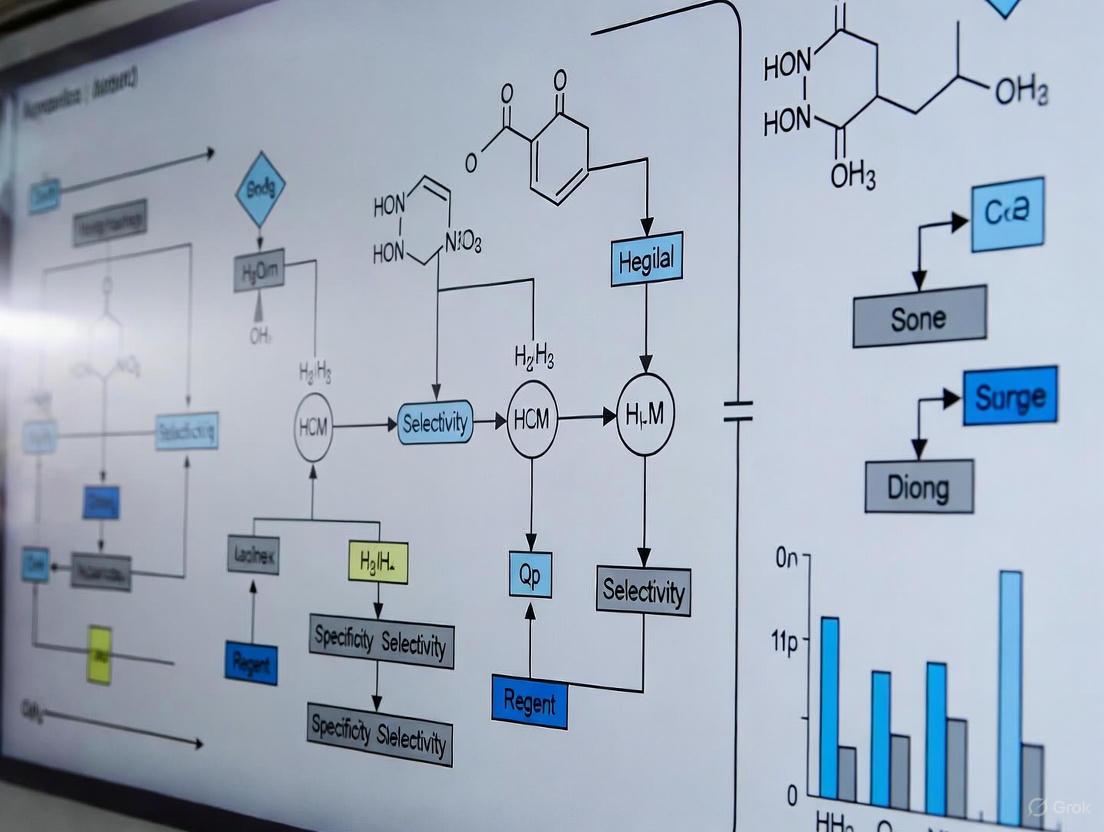

Visualization Diagrams

Achieving Specificity Through Selectivity Enhancement

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity/Selectivity Enhancement

Table 3: Essential Materials for Method Development

| Material/Technique | Function in Specificity/Selectivity | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hyphenated Techniques (LC-MS/MS) | Provides orthogonal separation and identification; confirms peak purity through spectral data | Distinguishing closely eluting compounds; confirming analyte identity in complex matrices [6] [3] |

| Chromatography Columns (various phases) | Enhances separation selectivity through different interaction mechanisms | Method development for resolving complex mixtures; optimizing separation of critical pairs |

| Immunoaffinity Sorbents | Provides high biological selectivity for specific analytes | Sample clean-up for complex biological matrices; extracting target analytes from interfering substances [3] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Synthetic materials with predetermined selectivity for target molecules | Selective extraction and pre-concentration of specific analytes; reducing matrix effects |

| Chemical Derivatization Reagents | Modifies analyte properties to enhance detection selectivity | Improving chromatographic separation; enhancing detection characteristics for specific compound classes |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Systematically optimizes multiple method parameters for maximum selectivity | Robustness testing; establishing method operable design regions [6] |

| Pentylcyclohexyl acetate | Pentylcyclohexyl Acetate|CAS 85665-91-4|For Research | Pentylcyclohexyl acetate is a chemical reagent for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. |

| Copper nickel formate | Copper Nickel Formate | CAS 68134-59-8 | Copper nickel formate is a chemical compound for research use only (RUO). It serves as a precursor for synthesizing Cu-Ni bimetallic nanoparticles and catalysts. Not for personal or human use. |

Advanced Tools for Challenging Separations

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS): Provides exact mass measurements for confident compound identification and distinguishing isobaric compounds [6]

- Multi-Attribute Methods (MAM): Consolidates analysis of multiple quality attributes into single assays, particularly valuable for biologics characterization [6]

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Enables real-time monitoring and control, supporting quality assurance through continuous verification of method performance [6]

The Critical Role in Patient Safety and Product Quality Assurance

Welcome to the Analytical Method Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and scientists address common challenges in analytical method development and validation, directly supporting specificity and selectivity research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical parameters to ensure method specificity and selectivity? Specificity and selectivity are validated by demonstrating that the method can accurately measure the analyte in the presence of potential interferences like impurities, degradants, or matrix components [4]. Key parameters include assessing resolution from known interferents and demonstrating the absence of false positives or negatives through forced degradation studies [4].

Q2: How can a Quality-by-Design (QbD) approach improve my analytical methods? A QbD approach involves defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) early on and using risk-based design and statistical tools like Design of Experiments (DoE) to understand the method's operational range [6]. This creates a more robust and reliable method by systematically evaluating the impact of method parameters on performance characteristics [7].

Q3: What should I do if my method's performance changes after transfer to a quality control (QC) lab? This indicates a potential ruggedness issue. First, verify that the method was adequately validated and that all critical parameters were documented. Ensure comprehensive training and knowledge transfer has occurred between teams. The receiving lab should perform a robustness study to identify sensitive parameters and establish a control strategy for consistent performance [6].

Q4: When is it acceptable to modify an already-validated method? Methods can be changed to improve reliability or efficiency. If changes are necessary—due to process changes, obsolete reagents, or technological improvements—a revalidation is required [7]. The extent of revalidation (from partial verification to full validation) depends on the significance of the change. Regulatory submissions must be amended accordingly [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Resolving Chromatographic Peak Issues

Common Symptoms and Solutions:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Investigative Action & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing [8] | Active sites on column [8], prolonged analyte retention [8] | - Use a different column chemistry (e.g., end-capped).- Modify mobile phase (e.g., use buffers or competing amines). |

| Split Peaks [8] | Contamination at inlet [9], blocked frit [9] | - Check and replace guard column.- Flush system with strong solvent.- Inspect and clean injector needle. |

| Extra / Ghost Peaks [8] | Sample carryover [8] [9], mobile phase contamination [8] | - Increase flush time in gradient.- Prepare fresh mobile phase.- Ensure thorough cleaning of auto-sampler. |

| Broad Peaks [8] | Column overloading [8], low column temperature [8], excessive tubing volume [8] | - Reduce injection volume.- Increase column temperature.- Use tubing with narrower internal diameter. |

Guide: Addressing Baseline Problems

Common Symptoms and Solutions:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Investigative Action & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Noise [8] | Air bubbles in system [8], contaminated detector cell [8], leaking pump seal [8] | - Degas mobile phase and purge system.- Clean or replace detector flow cell.- Check and replace pump seals if worn. |

| Baseline Drift [8] | Column temperature fluctuation [8], mobile phase composition change [8], contaminated flow cell [8] | - Use a thermostat-controlled column oven.- Prepare fresh mobile phase.- Flush flow cell with strong organic solvent. |

| High Backpressure [8] | Column blockage [8], flow rate too high [8], mobile phase precipitation [8] | - Reverse-flush column if possible, or replace.- Lower the flow rate.- Flush system with compatible solvent and prepare fresh mobile phase. |

| Low or No Pressure [8] | Major leak in system [8], air bubbles [8], faulty check valves [8] | - Identify and tighten leaking fittings.- Prime and purge the pump.- Inspect and replace check valves. |

Guide: Managing Sensitivity and Signal Problems

Common Symptoms and Solutions:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Investigative Action & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of Sensitivity [8] | Contaminated column or guard column [8], blocked injector needle [8] [9], incorrect mobile phase [8] | - Replace guard column.- Flush or replace the injector needle.- Prepare new mobile phase with correct composition. |

| Irreproducible Response [9] | Analyte Adsorption onto active surfaces in flow path (e.g., stainless steel) [9] | - Coat the entire flow path (tubing, valves, fittings) with an inert material like Dursan or SilcoNert to prevent adsorption of sticky compounds [9]. |

| Carryover [9] | Analyte Adsorption/Desorption from active flow path surfaces [9] | - Implement the same solution: ensure all flow path components are inert-coated to prevent analyte sticking and subsequent release [9]. |

| Retention Time Shifts [9] | Small changes in flow rate or solvent composition (HPLC) [4]; temperature fluctuations (GC) [4] | - Strictly control mobile phase preparation and use a column oven for HPLC.- Ensure temperature stability for GC [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Forced Degradation Study for Specificity

Objective: To demonstrate the method's ability to measure the analyte without interference from degradation products.

Materials:

- Acid/Base: 0.1M HCl, 0.1M NaOH

- Oxidizing Agent: 3% Hydrogen Peroxide

- Thermal Chamber: For solid and solution state stress

- Light Cabinet: For photostability testing (e.g., as per ICH Q1B)

Methodology:

- Stress Conditions: Expose the drug substance to various stress conditions.

- Acidic/Basic Hydrolysis: Treat with 0.1M HCl and 0.1M NaOH at room temperature for several hours.

- Oxidative Degradation: Treat with 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ at room temperature.

- Thermal Degradation: Heat solid and solution samples at 60°C for a defined period.

- Photolytic Degradation: Expose to specified light conditions.

- Sample Analysis: After stress, neutralize, dilute, or prepare samples as appropriate and analyze using the method under validation.

- Data Analysis: Assess chromatograms for the appearance of new peaks (degradants). Confirm that the analyte peak is pure and resolved from all degradant peaks, and that mass balance is achieved (approximately 98-102%).

Protocol 2: Design of Experiments (DoE) for Robustness Testing

Objective: To systematically evaluate the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters.

Materials:

- Statistical software (e.g., JMP, Design-Expert)

- HPLC/UHPLC system capable of precise parameter control

Methodology:

- Identify Critical Parameters: Select key variables (e.g., pH of mobile phase, column temperature, flow rate, gradient time) based on prior knowledge.

- Design the Experiment: Use a fractional factorial or response surface design to define the high and low levels for each parameter.

- Execute Runs: Perform the chromatographic runs in the randomized order specified by the DoE.

- Evaluate Responses: For each run, measure critical responses like resolution, tailing factor, and retention time.

- Statistical Analysis: Use the software to build models and identify which parameters have a statistically significant effect on the responses. Establish a Method Operational Design Range (MODR) where the method performs satisfactorily [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SilcoNert / Dursan Coatings [9] | Inert coatings applied to flow path components (tubing, fittings) to prevent adsorption of reactive analytes like Hâ‚‚S, amines, and proteins, thereby reducing carryover and peak tailing. |

| UHPLC Columns [6] | Columns packed with sub-2-micron particles that provide higher efficiency, better resolution, and faster analysis compared to traditional HPLC columns. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents with minimal impurities to reduce background noise and ion suppression in mass spectrometry, ensuring sensitivity and accurate quantification. |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Internal Standards | Used in bioanalytical methods (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to correct for analyte loss during sample preparation and for matrix effects, improving accuracy and precision. |

| qPCR Assays | Essential for biologics and cell & gene therapy analysis, used to quantify and validate specific DNA sequences, such as detecting residual host cell DNA or viral vector copy numbers [6]. |

| Arsine, dichlorohexyl- | Arsine, dichlorohexyl-, CAS:64049-22-5, MF:C6H13AsCl2, MW:230.99 g/mol |

| 2-Octyldodecyl acetate | 2-Octyldodecyl Acetate|CAS 74051-84-6|Supplier |

Method Development and Troubleshooting Workflows

Troubleshooting Logic Flow

Analytical Method Lifecycle Management

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main difference between FDA and EMA in their approach to method validation?

While both agencies follow ICH guidelines, their emphasis can differ. The FDA explicitly requires system suitability tests to be an integral part of the validation protocol and expects robustness to be thoroughly described in validation reports. The EMA also expects system suitability but may be less explicit in its requirement and often considers robustness evaluation as important but not always strictly mandatory for all methods. Global submissions should address both expectations [10].

Q2: At what stage during drug development should analytical methods be validated?

For GMP activities, methods should be properly validated, even for Phase I studies, following a phase-appropriate validation approach [7]. Method validation is typically executed against commercial specifications prior to process validation, which usually occurs during the pivotal clinical phase. Full validation is generally completed 1-2 years prior to commercial license application to ensure sufficient real-time stability data [7].

Q3: Can an analytical method be changed after it has been validated?

Yes, methods can be changed when necessary due to process changes, reagent availability, or technology improvements [7]. However, the extent of changes determines the revalidation requirements, ranging from simple verification to full validation. Method comparability results should be provided, and in some cases, product specifications may need re-evaluation. Regulatory submissions must be amended to reflect these changes [7].

Q4: How does ICH Q2(R2) differ from previous versions?

ICH Q2(R2) emphasizes a lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, integrating development and validation with a stronger focus on science-based and data-driven robustness assessments. It provides updated guidance on deriving and evaluating various validation tests for both chemical and biological/biotechnological drug substances and products [11] [6].

Q5: What are the key challenges in analytical method validation for biopharmaceuticals?

Biopharmaceuticals present unique challenges, especially for novel modalities like cell and gene therapies or patient-specific cancer vaccines. These include developing surrogate potency methods when direct assays don't exist, managing extended development timelines, and addressing product-specific suitability even when using established platform technologies [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Specificity and Selectivity Challenges

Problem: Interference from sample matrix components in complex biologics.

- Root Cause: Matrix effects from biological components can cause ion suppression in LC-MS/MS or non-specific binding in ligand-binding assays [7] [12].

- Solution:

- Implement extensive sample preparation techniques (protein precipitation, solid-phase extraction)

- Use alternative sample dilution methods to minimize matrix effects

- Employ the standard addition method or surrogate matrix approaches for endogenous compounds [12]

- Conduct parallelism assessments to ensure accurate quantification [12]

Problem: Inconsistent specificity for degradation products in stability-indicating methods.

- Root Cause: Inadequate chromatographic separation or insufficient detection specificity [4].

- Solution:

- Apply Quality by Design (QbD) principles with Design of Experiments (DoE) to optimize separation parameters [7] [6]

- Utilize multi-dimensional analytical techniques (LC-MS/MS, LC-UV-DAD) for enhanced specificity confirmation [6]

- Perform forced degradation studies under various stress conditions to validate method specificity for degradation products [4]

Problem: Method lacks robustness when transferred between laboratories.

- Root Cause: Incomplete understanding of critical method parameters and their acceptable ranges [7].

- Solution:

- Conduct comprehensive robustness studies using statistical experimental design (DoE) during method development [7] [6]

- Establish Method Operational Design Ranges (MODRs) that define acceptable parameter variations [6]

- Implement a method transfer protocol with predefined acceptance criteria and parallel testing [4]

Regulatory Compliance Issues

Problem: Regulatory submissions rejected due to insufficient validation data.

- Root Cause: Incomplete validation parameters or inadequate statistical evaluation [4].

- Solution:

- Ensure all validation parameters specified in ICH Q2(R2) are addressed based on the method's purpose (identification, testing for impurities, assay) [11]

- Provide sufficient data points for each validation parameter to ensure statistical significance [4]

- Include system suitability tests as part of the validation protocol, particularly for FDA submissions [10]

Problem: Inconsistencies in global submissions due to differing FDA and EMA expectations.

- Root Cause: Regional variations in regulatory emphasis and documentation requirements [10].

- Solution:

- Develop validation protocols that satisfy both FDA's explicit system suitability requirements and EMA's harmonization expectations [10]

- Maintain comprehensive documentation that demonstrates method robustness, even when not strictly required [10]

- Implement ALCOA+ principles for data integrity to meet both agencies' expectations [6]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Specificity and Selectivity Assessment for Chromatographic Methods

Purpose: To demonstrate the method's ability to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents.

Materials and Reagents:

- Reference standards of analyte and potential impurities/degradation products

- Blank matrix (placebo formulation for drug products or appropriate solvent for drug substances)

- Forced degradation samples (acid/base, oxidative, thermal, photolytic stress conditions)

- Mobile phase components and other chromatographic reagents

Procedure:

- Prepare individual solutions of the analyte and all known potential interferents

- Inject blank matrix to determine background interference

- Inject individual components to confirm resolution and retention times

- Inject mixture of analyte and interferents to demonstrate separation

- Perform forced degradation studies and analyze samples to demonstrate separation of degradation products

- Quantify any co-eluting peaks and calculate resolution factors

Acceptance Criteria:

- Resolution between analyte and closest eluting peak: ≥ 2.0

- Peak purity index: ≥ 0.999 for the analyte peak

- No interference at the retention time of the analyte from blank matrix

Protocol 2: Robustness Testing Using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Purpose: To identify critical method parameters and establish acceptable ranges for robust method performance.

Materials and Reagents:

- System suitability standard and test sample

- Chromatographic reagents from multiple lots (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Identify potential critical method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, flow rate)

- Design a Plackett-Burman or Fractional Factorial experiment to screen parameters

- Define low, medium, and high levels for each parameter based on normal operating conditions

- Execute experimental runs in randomized order

- Measure critical responses (resolution, tailing factor, efficiency, retention time)

- Analyze data using statistical methods to identify significant effects

- Establish Method Operational Design Ranges (MODRs) for critical parameters

Acceptance Criteria:

- All system suitability criteria met throughout the MODR

- No significant trends or failures in method performance within the MODR

- Statistical significance (p < 0.05) for critical parameter effects

Regulatory Requirements Comparison

Table 1: Key Regulatory Guidelines for Analytical Method Validation

| Guideline | Scope | Key Focus Areas | Status/Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICH Q2(R2) [11] | Analytical procedures for drug substances & products (chemical & biological) | Validation tests for assay, purity, impurities, identity; lifecycle approach | Current scientific guideline |

| ICH Q14 [6] | Analytical procedure development | Enhanced approach for method development, QbD principles | Forthcoming guideline |

| FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation (M10) [13] | Bioanalytical assays for nonclinical & clinical studies | Chromatographic & ligand-binding assays for drugs & metabolites | Final (November 2022) |

| EMA Bioanalytical Method Validation [14] | Bioanalytical methods for pharmacokinetic & toxicokinetic data | Quantitative concentration data for animal & human studies | Superseded by ICH M10 (July 2022) |

Table 2: Method Validation Parameters and Regulatory Expectations

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R2) Requirements [11] | FDA Emphasis [10] | EMA Emphasis [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Required for identification, purity tests, and assays | Must demonstrate no interference from placebo, impurities, or matrix | Expected, particularly for stability-indicating methods |

| Accuracy | Required with defined methodology for recovery assessment | Risk-based approach with appropriate confidence intervals | Harmonized approach across EU member states |

| Precision | Repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility | System suitability as integral part of validation | Expected but may allow some flexibility based on method purpose |

| Linearity | Demonstrated across specified range with statistical measures | Appropriate number of data points with correlation coefficient | Similar to ICH with focus on practical range of use |

| Range | Established from linearity, accuracy, and precision data | Must cover all intended sample concentrations | Consistent with ICH recommendations |

| Robustness | Should be considered during development phase | Should be thoroughly described in validation reports | Evaluated but not always strictly required |

Workflow Diagrams

Analytical Method Lifecycle Management

Specificity Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Primary standard for quantification and method calibration | Use well-characterized, high-purity materials; implement two-tiered approach linking working standards to primary reference standards [7] |

| Chromatographic Columns | Stationary phase for separation | Select appropriate chemistry (C18, C8, HILIC, etc.) with multiple lots for robustness testing [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | Mobile phase components for LC-MS | Low UV absorbance, high purity to minimize background noise and ion suppression [6] |

| Surrogate Matrices | Alternative matrix for standard curves for endogenous compounds | Use for biomarker assays or endogenous compound analysis when authentic matrix is not available [12] |

| Stability-Indicating Stress Reagents | For forced degradation studies (acid, base, oxidants) | Use to validate method specificity by creating degradation products [4] |

| System Suitability Standards | Verify system performance before sample analysis | Mixture of key analytes to check resolution, tailing factor, and reproducibility [10] |

| 2-Propylheptane-1,3-diamine | 2-Propylheptane-1,3-diamine|C10H24N2 Supplier | |

| Arotinolol, (R)- | Arotinolol, (R)-, CAS:92075-58-6, MF:C15H21N3O2S3, MW:371.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, achieving reliable analytical results is paramount. The accuracy of these results is consistently challenged by three major classes of interference: matrix effects, impurities, and degradants. These interference sources can significantly compromise data integrity, leading to inaccurate quantification, reduced method sensitivity, and ultimately, flawed scientific conclusions. Within the critical research on analytical method specificity and selectivity, understanding and mitigating these interferences is not merely a procedural step but a foundational requirement for ensuring that a method can unequivocally distinguish the analyte from other components. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological support to identify, quantify, and overcome these common yet challenging obstacles.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Matrix Effects

Q1: What is a matrix effect in analytical chemistry? The matrix refers to all components of a sample other than the analyte of interest. A matrix effect is the alteration of the analytical signal caused by these co-eluting matrix components. This interference can lead to either suppression or enhancement of the analyte signal, affecting the accuracy and reliability of the results [15] [16]. In techniques like LC-MS, this is often due to matrix components interfering with the ionization efficiency of the analyte [17].

Q2: How can I quantify the matrix effect in my assay? The matrix effect (ME) can be quantitated by comparing the analytical response of an analyte in a matrix extract to its response in a pure solvent. The following formula is commonly used [15]: ME = 100 × (A(extract) / A(standard))

- A(extract): Peak area of the analyte when diluted with matrix extract.

- A(standard): Peak area of the same concentration of analyte in a pure solvent.

A value of 100 indicates no matrix effect. A value below 100 indicates signal suppression, and a value above 100 indicates signal enhancement [15]. An alternative formula (ME = 100 × (A(extract)/A(standard)) - 100) sets 0 as the ideal value, with negative and positive values indicating suppression and enhancement, respectively [15].

Q3: What practical steps can I take to reduce matrix effects?

- Improve Sample Cleanup: Utilize more selective extraction or cleanup procedures (e.g., SPE, QuEChERS) to remove interfering matrix components [16].

- Use Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards: These standards experience nearly identical matrix effects as the analyte, effectively compensating for signal loss or enhancement [16] [17].

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Prepare calibration standards in a matrix that is free of the analyte but otherwise identical to the sample (e.g., using an extract from an organically grown source for pesticide analysis) [17].

- Standard Addition Method: Add known amounts of the analyte to the sample itself. This is particularly useful for complex or unknown matrices, as it accounts for the matrix influence directly [15].

- Chromatographic Optimization: Improve the separation to ensure the analyte elutes away from the matrix interferences, thus reducing co-elution [16].

FAQ: Impurities and Degradants

Q4: Why are new, unknown peaks appearing in my chromatogram? The appearance of unknown peaks can be attributed to several factors:

- Sample Degradation: The analyte may be degrading over time due to exposure to light, heat, or the solvent itself [18]. Omeprazole, for instance, is known to be unstable in acidic environments [18].

- Mobile Phase Contamination/Decomposition: Impurities in solvents or buffers, or the formation of degradation products from the mobile phase over time, can elute as extraneous peaks [18].

- System Carryover: A contaminated autosampler needle or injector can introduce traces from a previous, high-concentration sample [18]. Running a solvent blank can help diagnose this issue.

- Reagent Interactions: Impurities in reagents can react with the analyte or other sample components to form new compounds [19].

Q5: What is forced degradation, and why is it performed? Forced degradation, or stress testing, is the intentional degradation of a drug substance or product under conditions more severe than accelerated stability conditions. Its primary objectives are [20]:

- To establish the intrinsic stability of the molecule and elucidate its degradation pathways.

- To identify and characterize likely degradation products.

- To validate the stability-indicating properties of an analytical method by demonstrating its ability to separate the analyte from its degradants.

Q6: How much degradation is sufficient for a forced degradation study? While not strictly defined by regulations, degradation of drug substances between 5% and 20% is generally accepted for method validation [20]. A common target is approximately 10% degradation [20]. It is crucial to avoid over-stressing, which may generate secondary degradants not seen in real-time stability studies.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Matrix Effect

This protocol is adapted from guidelines for mass spectrometry-based analysis [17].

Prepare Solutions:

- Matrix-matched Sample: Extract a blank matrix (e.g., drug-free plasma, homogenized organic strawberry). Spike a known volume of a standard analyte solution (e.g., 100 µL of 50 ppb solution) into a known volume of the blank matrix extract (e.g., 900 µL) to achieve the desired concentration.

- Neat Standard: Prepare a standard at the same concentration in pure solvent (e.g., 100 µL of 50 ppb standard added to 900 µL solvent).

Analysis: Inject both solutions into the LC-MS or GC-MS system using the validated analytical method.

Calculation: Calculate the Matrix Effect (ME) using the formula provided in the FAQ section.

ME = 100 × (Peak Area of Matrix-matched Sample / Peak Area of Neat Standard)- Interpret the results as follows:

| ME Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 85% - 115% | Minimal matrix effect |

| < 85% | Signal suppression |

| > 115% | Signal enhancement |

Protocol 2: Forced Degradation Study to Identify Degradants

This protocol outlines standard stress conditions to generate degradation products for method development [21] [20].

Acid and Base Hydrolysis: Prepare a solution of the drug substance (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M NaOH, respectively. Store these solutions typically at elevated temperatures (e.g., 40°C, 60°C) and sample at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 3, 5 days) [20]. Neutralize the samples before analysis.

Oxidative Degradation: Expose the drug solution to an oxidizing agent such as 3% hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). Studies can be performed at room temperature or elevated temperatures (e.g., 25°C, 60°C) for shorter durations (e.g., 24 hours) [20].

Photodegradation: Expose the solid drug substance and/or solution to a light source that provides combined UV and visible radiation (as per ICH Q1B guidelines), typically at 1x and 3x ICH exposure levels [20].

Thermal Degradation: Study the solid drug substance by storing it in stability chambers at elevated temperatures (e.g., 60°C, 80°C) and different relative humidity levels (e.g., 75% RH) for specified durations [20].

Analysis: Analyze the stressed samples alongside an unstressed control using the developed chromatographic method (e.g., HPLC with a PDA or MS detector) to track the formation and separation of degradation products.

The workflow for a typical forced degradation study is outlined below:

Data Presentation

The table below summarizes typical experimental conditions used in forced degradation studies to predict the stability of a drug molecule [20].

| Degradation Type | Experimental Conditions | Typical Storage Conditions | Sampling Time Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Hydrolysis | 0.1 M HCl | 40°C, 60°C | 1, 3, 5 days |

| Base Hydrolysis | 0.1 M NaOH | 40°C, 60°C | 1, 3, 5 days |

| Oxidation | 3% H₂O₂ | 25°C, 60°C | 1, 3, 5 days (often ≤24h) |

| Photolysis | ICH-compliant light source | Not Applicable (NA) | 1, 3, 5 days |

| Thermal | Heat chamber (solid state) | 60°C / 75% RH, 80°C | 1, 3, 5 days |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for conducting experiments related to interference sources.

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Compensates for matrix effects and recovery losses during sample preparation, crucial for accurate MS quantification [16] [17]. |

| High-Purity HPLC/Spectroscopy Grade Solvents | Minimizes baseline noise and ghost peaks caused by impurities in the mobile phase [22]. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Phosphate, Formate, Acetate) | Controls mobile phase pH, which is critical for reproducible retention times and controlling the ionization state of ionic analytes [18]. |

| Stress Agents (e.g., HCl, NaOH, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Used in forced degradation studies to deliberately generate degradants and understand the stability profile of a drug molecule [21] [20]. |

| SPE Sorbents and Cartridges | Used for sample cleanup to remove matrix components, thereby reducing matrix effects and protecting the analytical column [16]. |

| 9-Hydroxyvelleral | 9-Hydroxyvelleral Research Compound |

| Diholmium tricarbonate | Diholmium Tricarbonate|Ho₂(CO₃)₃ |

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

When facing an analytical problem, follow a logical, step-by-step approach to identify the root cause. The following diagram maps out this troubleshooting logic:

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Stability and Degradation in Complex Biologics

Problem: A bispecific antibody formulation shows increased aggregation and high viscosity at high concentrations, making subcutaneous administration difficult.

Potential Cause 1: Protein-Protein Interactions and Unfavorable Excipient Profile

- Investigation Procedure: Systematically screen excipients (e.g., surfactants, sugars, amino acids) using a high-throughput platform to identify those that effectively reduce viscosity and prevent aggregation. Assess protein-protein interaction parameters using dynamic light scattering (DLS) or static light scattering (SLS) [23].

- Solution: Optimize the formulation with a careful mix of excipients, such as surfactants (e.g., polysorbate 80) and viscosity-reducing agents (e.g., histidine, arginine), to disrupt protein-protein interactions without compromising stability [23].

Potential Cause 2: Stress from Manufacturing and Administration

- Investigation Procedure: Perform in-use stability and compatibility testing. Simulate the administration process, including dilution into IV bags and passage through administration sets, filters, and closed system transfer devices (CSTDs). Monitor for subvisible particle formation and protein loss due to adsorption [24].

- Solution: Redesign the formulation to withstand interfacial stress, potentially by optimizing surfactant type and concentration. Select administration components that minimize surface interactions and particle generation [24].

Guide 2: Overcoming Analytical Method Gaps for Gene Therapy Potency

Problem: Inconsistent and unreliable potency assay results for an AAV-based gene therapy, causing delays in product release and regulatory filings.

Potential Cause 1: Late Development of Functional Potency Assays

- Investigation Procedure: Review the assay development timeline. Confirm if the functional potency assay was initiated early in development, as it often takes up to a year to fully develop and validate [25].

- Solution: Initiate potency assay development in parallel with other critical analytical methods, not after. Begin during pre-clinical or early-phase development to ensure it is ready for later-stage regulatory submissions [25].

Potential Cause 2: Misapplication of Bioanalytical Guidance

- Investigation Procedure: Review the bioanalytical method validation plan. Check if it inappropriately applies drug-centric validation criteria (e.g., from ICH M10) without considering the Context of Use (COU) for the biomarker or potency assay [12].

- Solution: Develop a COU-driven bioanalytical study plan. Tailor accuracy, precision, and other validation parameters to the specific objectives of the potency measurement and the subsequent clinical decisions it will inform, rather than applying fixed criteria [12].

Guide 3: Ensuring Specificity and Selectivity for New Modalities

Problem: Analytical methods for an Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) fail to specifically quantify the intact conjugate in patient plasma, leading to inaccurate pharmacokinetic data.

Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Sample Preparation and Matrix Effects

- Investigation Procedure: Evaluate the sample preparation protocol for extracting the ADC from plasma. Use techniques like surrogate matrix, surrogate analyte, or standard addition to account for the complex biological matrix and endogenous interferences [12] [26].

- Solution: Implement robust sample preparation, such as solid-phase extraction or immunoaffinity capture, followed by LC-MS/MS analysis with a stable isotope-labeled internal standard to correct for matrix effects and improve specificity [26].

Potential Cause 2: Method Limitations in Resolving Complex Heterogeneity

- Investigation Procedure: Characterize the method's ability to resolve the intact ADC from its naked antibody, free payload, and other metabolites. Use orthogonal techniques like SEC-MS or IEX-MS to confirm separation [23] [27].

- Solution: Employ a multi-attribute method (MAM) using high-resolution LC-MS to monitor multiple critical quality attributes (CQAs) simultaneously, ensuring selective quantification of the intact product amidst its variants and impurities [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How early in development should we focus on formulation stability for a novel biologic? As early as possible. Basic formulation work should begin soon after candidate selection. Early stability data guide process development and create a stronger CMC story from the start. Addressing formulation later can introduce significant risks and expensive delays [23].

Q2: What are the key regulatory expectations for stability studies supporting a Biologics License Application (BLA)? Regulators expect comprehensive, long-term stability data from at least three batches of the drug product, typically covering the proposed shelf life (e.g., 24 months). Studies must include rigorous testing of potency, degradation products (aggregates, fragments), and chemical modifications. The data must justify the expiration date and storage conditions through statistical shelf-life modeling [27].

Q3: Our gene therapy product is a novel AAV serotype. How can we develop a platform analytical method? While full platform approaches are challenging for highly diverse gene therapies, you can platform the framework. Develop product-agnostic assays for universal attributes (e.g., host cell DNA, residual impurities) and focus custom development on the few product-specific assays critical for your serotype, such as genome titer, potency, and capsid integrity [25].

Q4: What is the biggest mistake teams make with potency assays for cell and gene therapies? The most common mistake is delaying the development of the functional potency assay. While the FDA may not require it for Phase 1, developing it can take up to a year. Starting too late is a major cause of delays in later-stage regulatory filings [25].

Q5: How can we demonstrate specificity in a potency assay for a CAR-T cell product? The assay must specifically measure the product's intended biological function (e.g., tumor cell killing). This involves using relevant, well-characterized target cells and controls, including empty vector controls and non-transduced T cells, to ensure the measured response is due to the CAR and not non-specific immune activation [28].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Challenges and Mitigation Strategies for Novel Modalities

| Modality | Key Challenge | Proposed Mitigation Strategy | Critical Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bispecific Antibodies | Aggregation, high viscosity at high concentration [23] | Predictive stability modeling; optimized excipient screening [23] | SE-HPLC, DLS, viscosity measurement |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | Complex heterogeneity, drug-to-ratio (DAR) distribution [23] | Multi-attribute method (MAM) by LC-MS [27] | HIC, HRAM LC-MS |

| AAV Gene Therapies | Empty/full capsid ratio, potency assay relevance [29] [25] | Orthogonal methods for capsid quantification; early development of cell-based potency assays [25] | AUC, Mass Photometry, cell-based assays |

| Cell Therapies (e.g., CAR-T) | Functional potency, product variability [28] | Development of mechanism-based bioassays [28] | Flow cytometry, cytokine release assays, cytotoxicity assays |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Surrogate Matrix | Used in biomarker and endogenous compound bioanalysis to create calibration standards when the natural biological matrix is unavailable or interfered [12]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Added to samples during LC-MS/MS analysis to correct for variability in sample preparation, matrix effects, and instrument response, improving accuracy and precision [26]. |

| Relevant Reference Standard | A well-characterized sample of the analyte used to calibrate instruments and validate method performance, ensuring data accuracy and comparability [26] [27]. |

| Platform Purification Resins | Pre-characterized chromatography resins (e.g., for AAV purification) used in platform processes to accelerate development and improve consistency, though may require customization for novel serotypes [25]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Excipient Screening for Protein Stabilization

Objective: To rapidly identify excipients that minimize aggregation and viscosity in a high-concentration protein formulation.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Prepare a master solution of the target protein at the desired concentration.

- Excipient Panel: Dispense the protein solution into a 96-well plate containing a pre-defined library of excipients (e.g., salts, sugars, surfactants, amino acids) at various concentrations.

- Incubation: Seal the plate and incubate under stressed conditions (e.g., 40°C with agitation) to accelerate degradation.

- Analysis:

- Aggregation: Quantify soluble aggregates using a plate-reader-based size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or static light scattering (SLS).

- Viscosity: Measure viscosity in each well using a micro-viscometer.

- Stability: Monitor other CQAs like subvisible particles by microflow imaging.

- Data Analysis: Use statistical software to rank excipients based on their ability to suppress aggregation and reduce viscosity [23].

Protocol 2: Forced Degradation Studies for Method Robustness

Objective: To challenge the specificity and selectivity of an analytical method by exposing the product to stressed conditions and ensuring the method can resolve degradation products from the main peak.

Methodology:

- Stress Conditions: Aliquot the drug substance and subject it to various stress conditions:

- Thermal: Incubate at 40°C for 1-4 weeks.

- pH: Expose to low (e.g., pH 3-4) and high (e.g., pH 9-10) conditions.

- Oxidation: Treat with hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 0.1%).

- Light: Expose to UV and visible light per ICH Q1B.

- Mechanical: Subject to agitation/vortexing.

- Analysis: Analyze stressed samples and unstressed controls using the developed method (e.g., RP-HPLC, IEX, CEX).

- Evaluation: Assess the method's ability to:

- Detect new peaks (degradants) without co-elution with the main peak (demonstrating specificity).

- Accurately quantify the main peak in the presence of degradants (demonstrating selectivity) [27].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Analytical Method Development Workflow

Stability and Degradation Pathway Analysis

Advanced Techniques for Achieving Robust Specificity in Complex Analyses

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQs on Common Resolution Issues

Q1: My peaks are overlapping or co-eluting. What are the most effective ways to improve resolution?

The resolution (Rs) of two closely eluting peaks is governed by the equation: Rs = (1/4)√N * [(α-1)/α] * [k2/(1+k2)], where N is column efficiency, α is selectivity, and k is retention factor [30]. The most powerful approaches target these parameters:

- Change Selectivity (α): This is the most effective strategy for drastically improving resolution [30].

- Modify the Mobile Phase pH: This is highly effective for ionizable compounds, as it alters their hydrophobicity. A pH change of 1-2 units can significantly shift retention times [31].

- Change the Organic Modifier: Switching from acetonitrile to methanol or tetrahydrofuran can alter interaction mechanisms and peak spacing. Figure 4 provides a guide for estimating equivalent solvent strengths [30].

- Adjust Buffer or Additive Concentration: Changes can impact the retention of ionic analytes [31].

- Increase Column Efficiency (N): This sharpens peaks, improving resolution for moderately overlapped peaks.

- Use a Column with Smaller Particles: Columns packed with sub-2 µm particles provide higher plate numbers and sharper peaks [30].

- Increase Column Temperature: Higher temperatures reduce mobile phase viscosity and increase diffusion rates, enhancing efficiency. A good starting point is 40–60 °C for small molecules [30].

- Use a Longer Column: Doubling column length can increase peak capacity by approximately 40%, which is valuable for complex samples like protein digests [30].

- Optimize Retention Factor (k): Ensure analyte peaks elute within the optimal k range of 2-10. This can be achieved by reducing the strength of the mobile phase (e.g., decreasing the percentage of organic solvent) [30].

Q2: My peaks are tailing. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Peak tailing (asymmetry factor >1.2) compromises resolution, quantitation, and reproducibility [32]. The common causes and solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Peak Tailing

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Secondary interactions with ionized residual silanol groups on the stationary phase (especially for basic compounds) [32]. | - Operate at a lower pH (e.g., pH <3) to suppress silanol ionization [32].- Use a highly deactivated (end-capped) column [32]. |

| Column bed deformation or partially blocked inlet frit [32]. | - Reverse the column and flush with strong solvent [32].- Substitute the column to confirm the problem [32]. |

| Sample overloading or viscous sample [32]. | - Dilute the sample and re-inject [32].- Use a sample clean-up procedure (e.g., Solid-Phase Extraction) [32]. |

| Inappropriate solvent for sample dissolution [32]. | - Whenever possible, dissolve and inject samples in the mobile phase [32]. |

Q3: How can I track and identify peaks when developing a new method or screening conditions?

While UV spectra can be featureless, making peak tracking difficult, most modern software can create derivative spectra (dA/dλ) [33]. These 1st-order derivative spectra contain more useable maxima and minima, providing additional data points to increase confidence when identifying or tracking peaks across different method conditions [33].

Q4: I am experiencing inconsistent retention times and selectivity. What should I investigate?

Retention time instability often points to issues with method equilibration or mobile phase/sample composition.

- Insufficient Equilibration: In gradient elution, allow for at least 10 column volumes for re-equilibration after the gradient [32].

- Mobile Phase Instability: Evaporation of volatile components or buffer degradation can change composition over time. Cover solvent reservoirs and prepare fresh mobile phase frequently [32].

- Sample Solvent Effects: Injecting a sample dissolved in a solvent stronger than the mobile phase can cause peak distortion and retention time shifts. Dissolve the sample in the mobile phase or a weaker solvent whenever possible [32].

- Column Temperature Fluctuation: Use a column oven to maintain a constant temperature [32].

Advanced Strategy: Multidimensional Modeling for Robust Methods

For high-value applications like pharmaceutical development, multidimensional modeling is a powerful tool to define a Method Operable Design Region (MODR)—a set of robust method conditions where baseline separation (Rs ≥ 1.5) is consistently achieved despite minor, expected variations [31].

This approach uses a first-principles model calibrated with a minimal number of experiments (e.g., 4 runs for a 2-parameter model) to predict separation patterns across a wide range of conditions (e.g., gradient time, temperature, and pH) [31]. This strategy can be applied to:

- Column Interchangeability: Identify shared MODRs across different C18 columns, ensuring equivalent performance and mitigating supply chain issues [31].

- Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility: Compare column batches to select method conditions that are robust against minor manufacturing variations [31].

- HPLC System Comparability: Account for instrumental differences (e.g., dwell volume, thermal control) when transferring methods between systems [31].

The following workflow outlines the systematic application of this modeling approach in method development.

Systematic Workflow for Robust Method Development

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Targeted Isolation of Natural Products using UHPLC-Guided Workflow

This protocol leverages advanced metabolite profiling for the targeted isolation of specific compounds from complex natural extracts, a common challenge in drug discovery from natural sources [34].

1. Metabolite Profiling and Compound Prioritization:

- Instrumentation: UHPLC system coupled to PDA and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) [34].

- Analytical Column: Reversed-phase column (e.g., C18) with sub-2 µm particles [34].

- Method: Run a generic, wide-window gradient (e.g., 5-100% organic modifier over 20-60 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Use HRMS/MS data for putative annotation of metabolites (dereplication). Prioritize compounds based on desired properties (e.g., structural novelty, bioactivity from assays) [34].

2. Analytical Method Transfer to Semi-Preparative Scale:

- Objective: Replicate the selectivity of the analytical UHPLC separation at the semi-prep scale.

- Tool: Use HPLC modeling software to transfer the analytical gradient to semi-preparative conditions via chromatographic calculation, ensuring similar selectivity [34].

- Semi-Preparative Column: Use a column with the same bonded phase chemistry as the analytical column but with larger internal diameter and particle size (e.g., 5-10 µm) [34].

3. Targeted Isolation with Multi-Detection Guidance:

- Setup: Connect the semi-prep HPLC to UV, MS, and/or Evaporative Light Scattering (ELSD) detectors.

- Process: Inject the extract. Use the real-time detector signals to precisely trigger the collection of fractions containing the target ions (from MS) or chromophores (from UV), while monitoring for purity [34].

- Scale: This approach can be applied from milligram to gram amounts of extract depending on the system and column size [34].

Protocol 2: Systematic Optimization for Complex Biological Samples

This protocol is designed to achieve rapid, high-resolution separation of complex biological samples (e.g., plasma, tissue extracts) which are prone to matrix effects and co-elution [35].

1. Sample Preparation to Mitigate Matrix Effects:

- Technique: Use protein precipitation (PP) with acetonitrile, which is simple but may not fully remove phospholipids. For cleaner extracts, employ Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) [35].

- Internal Standard: Whenever possible, use a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (SIL-IS) for each analyte to correct for matrix-induced ion suppression/enhancement in LC-MS [35].

2. Column and Mobile Phase Screening:

- Strategy: Use an automated UHPLC system with switching valves to screen different stationary phases (e.g., C18, phenyl, HILIC) and mobile phase conditions (pH, organic modifier) [36].

- Initial Conditions: Start with a fast, wide-gradient (e.g., 5-95% acetonitrile in 10 min) at a temperature of 40-60°C on a short column (e.g., 50 mm) packed with sub-2 µm particles [36].

3. Resolution Optimization via Parameter Fine-Tuning:

- If co-elution persists:

- Flatten the gradient: Decrease the rate of organic modifier increase to improve resolution [30].

- Adjust pH: For ionizable compounds, fine-tune pH in 0.2-0.5 unit increments to maximize selectivity differences [31].

- Change organic modifier: Switch from acetonitrile to methanol to alter selectivity [30].

- Increase temperature: Elevate temperature to 60-90°C for large molecules to enhance efficiency [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for HPLC/UHPLC Method Development

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Columns with sub-2 µm Particles | Foundation of UHPLC; provide high efficiency and resolution, enabling faster separations [36]. |

| Superficially Porous Particles (Core-Shell) | Provide efficiency similar to sub-2 µm fully porous particles but with lower backpressure, compatible with a wider range of HPLC systems [30]. |

| High-Purity Buffers & Additives | Essential for controlling mobile phase pH and ionic strength; critical for reproducible retention of ionizable compounds [31]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Minimize UV absorbance background noise and MS chemical noise, improving detection sensitivity [33] [35]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | Gold standard for compensating matrix effects and analyte loss during sample preparation in quantitative LC-MS bioanalysis [35]. |

| In-line Filter (0.22 µm) & Guard Column | Protect the analytical column from particulate matter and strongly adsorbed matrix components, extending column life [32]. |

| Modeling & Method Development Software | Allows for predictive method development and robust optimization with minimal experimental runs, saving time and resources [31]. |

| 2,2,6-Trimethyldecane | 2,2,6-Trimethyldecane Reference Standard |

| 2,6-Dicyclohexyl-p-cresol | 2,6-Dicyclohexyl-p-cresol, CAS:7226-88-2, MF:C19H28O, MW:272.4 g/mol |

Peak purity assessment is a critical analytical procedure within pharmaceutical development, directly supporting a broader thesis on enhancing analytical method specificity and selectivity. It ensures that a chromatographic peak for a primary analyte, such as a drug substance, is not attributable to more than one component, like a co-eluting degradant or impurity. This evaluation is foundational for validating stability-indicating methods, which are mandated for regulatory submissions. Within the pharmaceutical industry, two predominant techniques facilitate this assessment: Photodiode Array (PDA or DAD) detection and Mass Spectrometry (MS) detection [37] [38]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols to address the specific challenges researchers face in implementing these techniques.

Understanding Peak Purity Assessment

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is peak purity assessment? Peak purity assessment is a set of analytical procedures used to demonstrate that a chromatographic peak is spectrally homogeneous, meaning it originates from a single compound. This is a direct measure of an analytical method's selectivity and is a crucial component of forced degradation studies for regulatory filings [37].

Why is it crucial for method specificity and selectivity research? A method's ability to accurately measure the analyte of interest without interference from other components is its specificity. Peak purity assessment is the experimental proof that the method can distinguish the main analyte from impurities, even under stressful conditions that generate degradants. Without this confirmation, stability studies risk being compromised by undetected co-elutions, leading to inaccurate stability conclusions [37].

Key Techniques at a Glance

The following table summarizes the two primary techniques used for peak purity assessment.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Peak Purity Assessment Techniques

| Feature | Diode Array Detector (DAD/PDA) | Mass Spectrometry (MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Compares UV-Vis absorption spectra across a chromatographic peak [37] [39]. | Monitors mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) across a chromatographic peak [37] [38]. |

| Primary Output | Purity angle and purity threshold (or spectral similarity factor) [37]. | Extracted Ion Chromatograms (XICs), comparison of mass spectra [37] [38]. |

| Key Strength | Efficient, non-destructive, and well-understood for detecting co-elutions with different UV spectra [37]. | Highly selective and sensitive; can detect co-elutions with minimal spectral difference if they have different masses [37] [38]. |

| Key Limitation | Cannot distinguish co-eluting compounds with nearly identical UV spectra; prone to false negatives/positives under certain conditions [37]. | Higher cost and complexity; not universal (e.g., for isomers with identical mass); destructive technique [37] [40]. |

Diagram 1: Peak Purity Assessment Workflow

Diode Array Detection (DAD/PDA) Deep Dive

How It Works

A Diode Array Detector uses a broad-spectrum light source (e.g., Deuterium and Tungsten lamps). The light passes through the sample flow cell, and after dispersion by a holographic grating, the full spectrum of light is projected onto an array of diodes. This allows for the simultaneous detection of absorbance across a wide UV-Vis range (typically 190-900 nm) for each data point collected during the chromatographic run [39]. For peak purity, the key is to compare the UV spectra obtained at different points across the peak—typically the upslope, apex, and downslope [37].

Commercial software algorithms calculate spectral contrast. For example, in Waters' Empower software, spectra are treated as vectors, and the "purity angle" (a weighted average of the angles between all spectra in the peak and the apex spectrum) is compared to a "purity threshold" (which accounts for spectral noise). A peak is considered pure if the purity angle is less than the purity threshold [37]. Agilent's OpenLab uses a similar approach, calculating a similarity factor [37].

Troubleshooting Guide for PDA-based PPA

Table 2: Common PDA PPA Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| False Negative (PPA passes, but impurity is co-eluting) | 1. Impurity has a nearly identical UV spectrum to the parent compound.2. Impurity concentration is too low.3. Impurity elutes very close to the peak apex [37]. | 1. Employ an orthogonal technique like MS.2. Increase sample load or stress conditions to generate higher impurity levels.3. Optimize the chromatographic method to improve separation. |

| False Positive (PPA fails for a pure peak) | 1. Significant baseline shift due to mobile phase gradients.2. Suboptimal integration or background noise.3. UV measurement at extreme wavelengths (<210 nm) [37]. | 1. Use a mobile phase blank for background subtraction.2. Re-integrate the chromatogram and adjust PPA processing parameters (e.g., baseline points).3. If possible, select a wavelength with higher analyte absorbance and lower noise. |

| High Spectral Noise | 1. Low analyte concentration.2. Detector lamp failure or aging.3. Contaminated flow cell [37] [41]. | 1. Concentrate the sample or use a path length flow cell.2. Check lamp hours and replace if necessary.3. Flush the flow cell thoroughly with appropriate solvents. |

Experimental Protocol: PDA-based Peak Purity

Objective: To demonstrate the spectral homogeneity of the main analyte peak in a stressed sample using a PDA detector.

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC System: Equipped with a Diode Array Detector (e.g., Agilent 1260 Infinity II DAD, Waters Alliance with 2998 PDA, or Scion 6430 DAD) [37] [39].

- Software: CDS with PPA algorithm (e.g., Waters Empower, Agilent OpenLab CDS, Shimadzu LabSolutions) [37].

- Analytical Column: As per the validated method (e.g., C18, 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: Prepared as per the validated method.

- Samples: Stressed sample (e.g., acid/base/oxidative degraded) and a reference standard of the pure analyte.

Procedure:

- System Suitability: Ensure the LC system meets all suitability criteria (e.g., retention time reproducibility, plate count, tailing factor) before analysis.

- Data Acquisition: Inject the stressed sample and acquire chromatographic data with PDA detection. Set the PDA to acquire a full spectrum (e.g., 210-400 nm) at a sufficiently high rate (e.g., 1 spectrum/second) to obtain multiple spectra across the peak of interest.

- Data Processing:

- Integrate the chromatogram at the appropriate wavelength.

- Select the main analyte peak for PPA.

- In the CDS software, initiate the peak purity algorithm. The software will typically automatically select spectra from the peak start, apex, and end for comparison.

- Review the overlaid normalized spectra and the calculated purity result (e.g., Purity Angle and Purity Threshold in Empower, or Similarity in OpenLab).

- Interpretation: A peak is considered spectrally pure if the software-specific criterion is met (e.g., Purity Angle < Purity Threshold). Visually confirm that the overlaid normalized spectra from different parts of the peak are identical.

Mass Spectrometry Detection Deep Dive

How It Works

LC-MS separates ions by their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio. For peak purity assessment, the goal is to demonstrate that the same precursor ions, product ions, and/or adducts attributed to the parent compound are present consistently across the entire chromatographic peak [37] [38]. This is typically assessed by examining the Extracted Ion Chromatograms (EICs or XICs) for key ions and comparing mass spectra taken at the peak front, apex, and tail [37] [38].

If an impurity with a different molecular weight is co-eluting, its distinct m/z signal will cause the EIC for that ion to peak at a different retention time or show a distorted shape. Furthermore, the mass spectrum will change across the peak as the relative proportions of the analyte and impurity change [38]. Chemometric techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can also be applied to the full MS data set to detect subtle spectral changes indicating impurity presence [38].

Troubleshooting Guide for MS-based PPA

Table 3: Common MS PPA Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| No Peaks / Low Signal | 1. Ion source contamination or improper ionization.2. Gas leaks or incorrect gas pressures.3. Incorrect MS tuning or calibration [41] [40]. | 1. Clean the ion source and check ionization mode (positive/negative).2. Use a leak detector to check for gas leaks, especially at column connectors and valves [41].3. Re-tune and re-calibrate the mass spectrometer according to manufacturer protocols. |

| Poor Mass Accuracy/Resolution | 1. Instrument calibration drift.2. Contaminated analyzer.3. Signal saturation [40]. | 1. Re-calibrate using the appropriate standard.2. Schedule routine instrument maintenance.3. Dilute the sample or reduce the injection volume. |

| Cannot Distinguish Isomers | 1. Fundamental limitation: Isomers have identical m/z ratios [40]. | 1. Optimize the chromatographic method to achieve baseline separation.2. Use tandem MS (MS/MS) to compare fragment ion patterns if the isomers fragment differently. |

| Signal Drift/Instability | 1. Contaminated API interface.2. Fluctuations in mobile phase delivery or gas flow. | 1. Clean the interface components (e.g., orifice, skimmer).2. Check LC pump performance and ensure gas supplies are stable and sufficient. |

Experimental Protocol: MS-based Peak Purity

Objective: To demonstrate the mass spectral homogeneity of the main analyte peak in a stressed sample using an LC-MS system.

Materials and Reagents:

- LC-MS System: Single quadrupole or higher-end MS system (e.g., Waters QDa, Agilent MSD, Sciex API systems) [37] [38] [40].

- Software: Instrument control and data processing software.

- Analytical Column: As per the validated method.

- Mobile Phase: Volatile buffers compatible with MS (e.g., ammonium formate, ammonium acetate) and MS-grade organic solvents.

- Samples: Stressed sample and a reference standard of the pure analyte.

Procedure:

- MS Tuning: Tune and calibrate the mass spectrometer for optimal sensitivity and mass accuracy for the analyte of interest.

- Method Setup: Configure the LC-MS method. Set the mass spectrometer to scan a relevant m/z range that includes the [M+H]+ (or other relevant adducts) of the analyte and its potential degradants.

- Data Acquisition: Inject the stressed sample and acquire data in full-scan mode.

- Data Processing:

- Examine the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC).

- Generate Extracted Ion Chromatograms (XICs) for the primary ion of the analyte (e.g., [M+H]+) and for any potential or known impurity ions.

- Extract and overlay mass spectra from at least three points across the analyte peak: the leading edge, the apex, and the trailing edge.

- Interpretation: The peak is considered pure by MS if:

- The EIC for the analyte ion is symmetrical and overlaps perfectly with the TIC peak.

- The overlaid mass spectra from across the peak are identical, showing the same ions with the same relative abundances.

- There are no detectable, consistently evolving EICs for other ions within the retention time window of the main peak.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials for Peak Purity Assessment Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Volatile Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate) | Essential for LC-MS mobile phases to prevent ion suppression and source contamination. Non-volatile salts can clog the MS interface [38]. |

| MS-Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | High-purity solvents minimize background noise and chemical noise in mass spectrometry, ensuring high-quality spectra [40]. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Stressed samples (e.g., via heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) are required to generate potential degradants against which the method's selectivity and peak purity must be demonstrated [37]. |

| Reference Standards | Highly pure analyte standards are critical for system suitability testing and as a spectral reference for comparison during PDA and MS analysis [37]. |

| PDA Calibration Solution | A solution like holmium oxide is used to validate the wavelength accuracy of the PDA detector, ensuring spectral data is reliable [37]. |

| MS Calibration Solution | A standard containing compounds of known mass (e.g., sodium formate for TOF, manufacturer-specific mix for quadrupoles) is used to calibrate the m/z scale for accurate mass measurement [40]. |

| Chloroac-met-OH | Chloroac-met-OH, MF:C7H12ClNO3S, MW:225.69 g/mol |

| 1,3-Benzodioxole-4,5-diol | 1,3-Benzodioxole-4,5-diol|CAS 23780-63-4 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My PDA peak purity passes, but I still suspect a co-elution. What should I do? This is a common scenario, often due to the limitations of PDA. A passing PDA result only confirms that no impurities with different UV spectra were detected. You should:

- Spike with Markers: Spike the sample with available impurity standards and see if the peak shape or purity result changes.

- Employ Orthogonal Detection: The most powerful approach is to analyze the sample using LC-MS. MS can often separate and detect co-eluting species based on mass, even if their UV spectra are identical [37].