Paradigm Shift in Analytical Chemistry: AI, Sustainability, and Regulatory Evolution Reshaping Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative evolution of analytical chemistry, driven by artificial intelligence, green principles, and modernized regulations.

Paradigm Shift in Analytical Chemistry: AI, Sustainability, and Regulatory Evolution Reshaping Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative evolution of analytical chemistry, driven by artificial intelligence, green principles, and modernized regulations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines foundational technological shifts, new methodological applications in pharmaceutical quality control, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing complex analyses, and the critical framework for method validation and comparative assessment. By synthesizing these core intents, the article provides a comprehensive roadmap for navigating the current landscape and leveraging these changes to accelerate biomedical innovation and enhance therapeutic efficacy and safety.

The Foundations of Change: AI, Sustainability, and New Regulations Reshaping the Lab

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a profound metamorphosis, moving beyond its traditional role of simple compositional analysis to become an information science central to modern research and development [1]. This transformation is driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which are reshaping how chemists collect, process, and interpret data. Where analytical chemistry once focused on obtaining singular, precise measurements, it now increasingly employs a systemic approach that seeks comprehensive compositional understanding and discovers complex relationships within data [1]. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in drug development, where AI-enhanced methods are accelerating the identification of promising compounds, optimizing synthetic pathways, and predicting molecular behavior with unprecedented speed and accuracy. The discipline has evolved from a problem-driven, unit-operations-based practice to a discovery-driven, holistic endeavor that leverages large, multifaceted datasets to generate new hypotheses and knowledge [1].

The Evolution of Analytical Data Processing

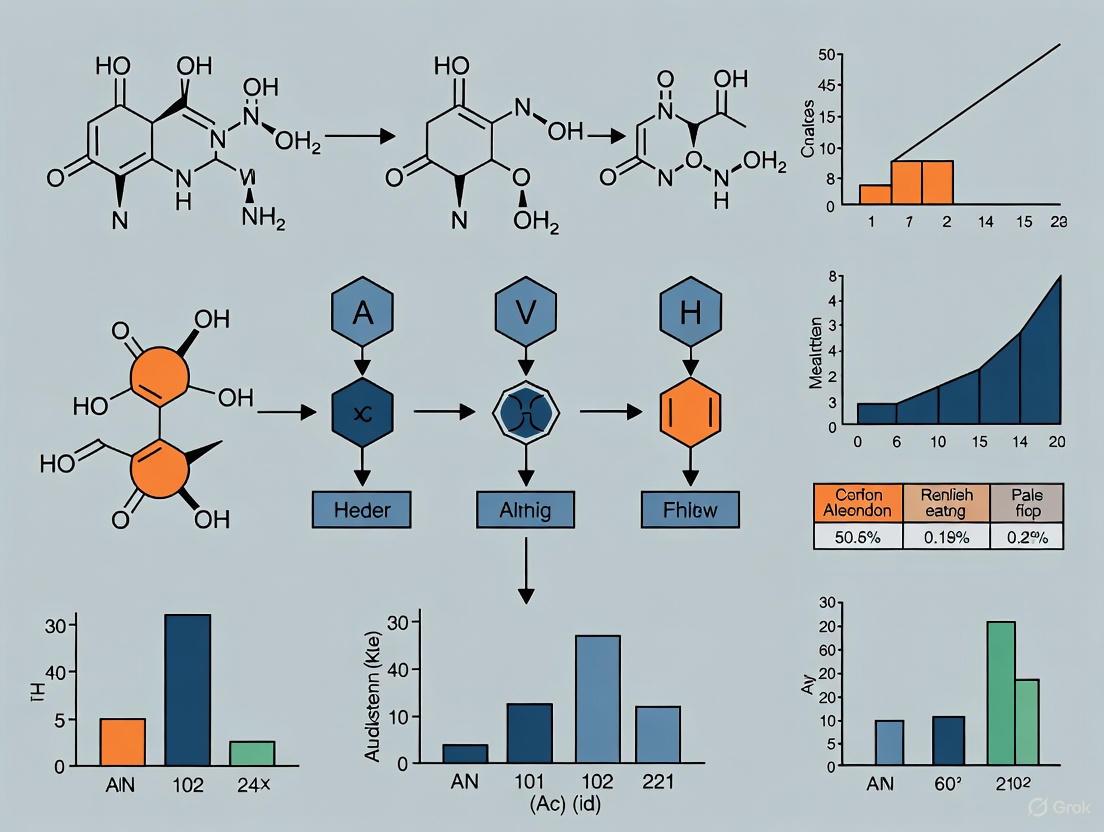

The metamorphosis of analytical chemistry is characterized by a fundamental reorientation in its operational model. Figure 1 contrasts the traditional linear approach with the modern, information-driven cycle enabled by AI and big data analytics.

From Traditional Analysis to Modern Information-Driven Cycles

Figure 1. Paradigm Shift: From Traditional Analysis to Modern Information-Driven Cycles. The traditional model (top) follows a linear, quality-focused path, while the AI-enhanced model (bottom) forms an iterative, discovery-driven cycle that continuously refines hypotheses and experimental design [1].

This shift has been catalyzed by several key technological developments. The massive and combined use of analytical instrumentation has enabled researchers to understand complex heterogeneous materials by revealing spatial-temporal relationships between chemical composition, structure, and material properties [1]. Furthermore, the integration of active learning—a specialized form of machine learning where the model selectively suggests new experiments to resolve uncertainties—has transformed experimental design from a human-centric process to an optimized, AI-guided workflow [2]. In one documented case, 1,000 researchers using an AI tool discovered 44% more new materials and filed 39% more patent applications compared to colleagues using standard workflows [3]. This demonstrates the profound impact of AI assistance on research productivity and output in real-world settings.

Core Machine Learning Methodologies in Chemistry

Fundamental Learning Approaches

ML algorithms can be broadly categorized into supervised and unsupervised learning, each with distinct applications in chemical research.

Table 1: Fundamental Machine Learning Approaches in Chemistry

| Learning Type | Key Characteristics | Common Algorithms | Chemistry Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Trained on labeled datasets with known outcomes [4] | Regression (Linear, Logistic) [4], Decision Trees [4], Random Forests [4], Support Vector Machines [4] | Property prediction [3], Reaction yield forecasting [3], Toxicity prediction [3] |

| Unsupervised Learning | Identifies patterns in unlabeled data [4] | Clustering Algorithms [5], Outlier Detection [5], Factor Analysis [5] | Customer segmentation [4], Anomaly detection in processes [4] |

Specialized Architectures for Chemical Data

The unique nature of chemical structures requires specialized ML approaches that can effectively represent molecular information:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These networks represent molecules as mathematical graphs where edges connect nodes, analogous to chemical bonds connecting atoms in molecules [3]. GNNs excel at supervised tasks like property and structure prediction, particularly when trained on large datasets containing thousands of structures [3]. They have been widely adopted in pharmaceutical companies because they can effectively link molecular structure to properties [3].

Transformer Models: Generative chemical models like IBM's RXN for Chemistry use transformer architecture to plan synthetic routes in organic chemistry [3]. These models, including MoLFormer-XL, often use Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) representations, translating a chemical's 3D structure into a string of symbols [3]. They learn through autocompletion, predicting missing molecular fragments to develop an intrinsic understanding of chemical structures [3].

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs): In molecular simulation, MLPs have become "a huge success" in replacing computationally demanding density functional theory (DFT) calculations [3]. Trained through supervised learning on DFT-calculated data, MLPs perform similarly to DFT but are "way faster," significantly reducing the computational time and energy requirements for simulations [3].

Predictive Modeling Approaches

Predictive modeling represents a mathematical approach that combines AI and machine learning with historical data to forecast future outcomes [6]. These models continuously adapt to new information, becoming more refined over time [6].

Table 2: Predictive Model Types and Their Chemical Applications

| Model Type | Function | Chemistry Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Classification Models | Predicts class membership or categories [5] [6] | Toxic vs. non-toxic compounds, Active vs. inactive molecules, Material type classification |

| Clustering Models | Groups data based on common characteristics [6] | Molecular similarity analysis, Customer segmentation for chemical products [4] |

| Outlier Models | Detects anomalous data points [6] | Fraud detection [4], Experimental anomaly identification, Quality control failure detection |

| Forecast Models | Predicts metric values based on historical data [6] | Reaction yield prediction, Sales forecasting for chemical products [4] |

| Time Series Models | Analyzes time-sequenced data for trends [6] | Reaction kinetics monitoring, Process parameter optimization over time |

AI-Driven Experimental Workflows

The integration of AI into practical laboratory research has led to the development of sophisticated experimental workflows that combine physical instrumentation with computational guidance.

Autonomous Experimentation Cycle

Figure 2. AI-Driven Autonomous Experimentation Cycle. This workflow illustrates how active learning algorithms guide iterative experimentation, optimizing the path to discovery with minimal human intervention [2].

Case Study: Catalyst Optimization for COâ‚‚ Conversion

Experimental Objective: Optimize a multi-material catalyst composition for converting carbon dioxide into formate to enhance fuel cell efficiency [2].

Methodology:

- Initial Dataset Preparation: Compile historical data on catalyst compositions, processing conditions (temperature, heat treatment duration), and corresponding performance metrics [2].

- Active Learning Setup: Implement an active learning algorithm that selectively suggests new experimental parameters to evaluate, focusing on areas of highest uncertainty or potential improvement [2].

- Iterative Experimentation:

- The AI system recommends specific metal combinations and processing parameters

- Automated systems execute experiments and collect performance data

- Results feed back into the active learning algorithm

- The process repeats with progressively refined suggestions [2]

- Validation: Top-performing catalysts identified through the AI-guided process undergo rigorous experimental validation.

Key Implementation Details:

- The active learning component significantly reduces the number of experiments required to identify optimal compositions [2].

- This approach optimizes both materials composition and processing conditions simultaneously [2].

- The system can autonomously handle routine tasks like valve control and liquid mixing through voice commands, reducing researcher workload [2].

Table 3: AI and Experimental Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| AiZynthFinder | Software Tool | Uses neural networks to guide searches for the most promising synthetic routes [3] |

| CRESt (Copilot for Real-World Experimental Scientist) | AI Lab Assistant | Voice-based system that suggests experiments, retrieves/analyzes data, and controls equipment [2] |

| AMPL (ATOM Modeling PipeLine) | Predictive Modeling Pipeline | Evaluates deep learning models for property prediction [3] |

| AlphaFold | Protein Structure Prediction | Creates graphs representing amino acid pairings to predict protein structures [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | ML Architecture | Specialized for molecular structure-property relationship modeling [3] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Simulation Tool | Replaces computationally intensive DFT calculations in molecular dynamics [3] |

| International Critical Tables | Data Resource | Comprehensive physical, chemical and thermodynamic data for pure substances [7] |

Validation and Benchmarking

As AI tools proliferate in chemical research, rigorous validation and benchmarking become essential to assess their real-world utility and limitations.

Benchmarking Frameworks

Several established benchmarking tools enable objective comparison of AI model performance:

- SciBench: Collates university-level questions to test large language models (LLMs) on chemistry knowledge, revealing that even advanced models like GPT-4 answered only approximately one-third of textbook questions correctly [3].

- Tox21: Standardized framework for comparing toxicity predictions of different models [3].

- MatBench: Provides benchmarks for predicting various properties of solid materials [3].

Reproducibility Challenges

General large language models such as ChatGPT exhibit significant reproducibility problems—when asked to perform the same task repeatedly, they often output multiple different responses [3]. This variability poses challenges for scientific applications requiring consistent, reproducible outputs. Furthermore, AI models trained on data from one chemical system are not necessarily transferable to other systems, creating considerable challenges for solving diverse chemistry problems [3].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the transformative potential of AI in chemistry, several significant challenges must be addressed:

- Data Quality and Availability: Machine learning tools require substantial, high-quality data. As a rule of thumb, having 1,000 or more data points enables meaningful analysis, with performance improving logarithmically with more data [3]. Data preparation and quality are key enablers of successful predictive analytics [5].

- Energy Consumption: While AI has a reputation for high energy usage, MLPs are actually reducing chemistry's computational electricity bills by replacing conventional DFT simulations that consume approximately 20% of U.S. supercomputer time [3].

- Interpretability and Trust: Many AI models function as "black boxes," making it difficult for chemists to understand and trust their recommendations. Developing more interpretable models and validation frameworks remains an ongoing challenge [3].

- Integration with Existing Workflows: Successfully implementing AI tools requires aligning them with research objectives and existing processes. Organizations must develop sound data governance programs and adapt processes to incorporate AI effectively [5].

The future of AI in chemical research points toward increasingly autonomous experimentation systems that combine machine learning with robotic instrumentation. These systems will enable "mass production of science" to address pressing global challenges like climate change [2]. As these technologies mature, establishing new standards for data sharing, validation, and collaborative research will be crucial for accelerating scientific progress across disciplines [2].

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, transforming from a routine service function to an enabling science that addresses complex interdisciplinary challenges [1]. This metamorphosis extends beyond technological advancement to encompass a profound re-evaluation of the environmental and societal impact of analytical practices [1] [8]. Where traditional analytical chemistry focused primarily on performance metrics like sensitivity and precision, the contemporary discipline must balance analytical excellence with environmental responsibility [9]. Green and Sustainable Analytical Chemistry represents the integration of this ethos into the core of analytical practice, driven by global sustainability imperatives, evolving regulatory expectations, and growing recognition that analytical methods themselves must align with the principles they help enforce in other industries [10]. This evolution from a "take-make-dispose" linear model toward a circular, sustainable framework represents one of the most significant transformations in the discipline's history, positioning analytical chemistry as a cornerstone of responsible scientific progress [1] [10].

Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is formally defined as the optimization of analytical processes to ensure they are safe, non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [11]. The framework for GAC is built upon 12 foundational principles that provide a systematic approach to designing and implementing sustainable analytical methods [12] [11]. These principles prioritize direct analysis methods that eliminate sample preparation stages where possible, advocate for minimizing sample sizes and reagent volumes, and promote the substitution of hazardous chemicals with safer alternatives [12]. Energy efficiency throughout the analytical process stands as another cornerstone principle, alongside the development and adoption of automated methods that enhance both safety and efficiency [12] [11]. A critical aspect of GAC involves the redesign of analytical methodologies to generate minimal waste, with parallel emphasis on proper waste management procedures for any materials that are produced [12]. The principles further advocate for multi-analyte determinations to maximize information obtained from each analysis, the implementation of real-time, in-situ monitoring to eliminate transportation impacts, and a fundamental commitment to ensuring the safety of analytical practitioners [11]. Underpinning all these practices is the imperative to choose methodologies that minimize overall environmental impact, thereby aligning analytical chemistry with the broader objectives of sustainable development [11].

Key Drivers for Adoption

Regulatory and Economic Imperatives

The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to adopt Green Analytical Chemistry principles due to tightening environmental regulations and compelling economic factors. Regulatory agencies are beginning to recognize the need to phase out outdated, resource-intensive standard methods in favor of greener alternatives [10]. A recent evaluation of 174 standard methods from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias revealed that 67% scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep metric (where 1 represents the highest possible greenness), highlighting the urgent need for method modernization [10]. Economically, GAC principles directly translate to reduced operational costs through decreased solvent consumption, lower waste disposal expenses, and improved energy efficiency [11]. The pharmaceutical analytical testing market, valued at $9.74 billion in 2025 and projected to reach $14.58 billion by 2030, represents a significant opportunity for implementing sustainable practices that simultaneously benefit both the environment and the bottom line [13].

Technological and Innovation Drivers

Technological advancements serve as crucial enablers for Green Analytical Chemistry, making previously impractical approaches now feasible and efficient. Miniaturization technologies allow dramatic reductions in solvent consumption and waste generation while maintaining analytical performance [14]. Modern instrumentation platforms increasingly incorporate energy-efficient designs and support automation, enhancing throughput while reducing resource consumption per analysis [13]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning optimizes method development and operational parameters, identifying conditions that maximize both analytical performance and environmental sustainability [13]. Additionally, innovation in alternative solvents—including ionic liquids, supercritical fluids, and bio-based solvents—provides greener options for traditional analytical methodologies [13] [12]. These technological drivers collectively enable analytical chemists to maintain the high data quality required for pharmaceutical applications while significantly reducing environmental impact.

Educational and Cultural Shifts

The transformation toward sustainable analytical practices is being further driven by fundamental shifts in chemistry education and professional culture. Universities are increasingly integrating GAC principles into their curricula, equipping the next generation of chemists with the mindset and tools necessary to prioritize sustainability [11]. Dedicated courses now teach students to evaluate traditional analytical methods, identify opportunities for improvement, and theoretically design greener alternatives [11]. Beyond formal education, a broader cultural evolution within the scientific community is elevating the importance of environmental responsibility, with researchers demonstrating growing interest in minimizing the ecological footprint of their work [11]. This cultural shift is further reinforced by funding agencies and scientific publishers who are increasingly recognizing and rewarding innovative approaches that advance sustainability goals [8].

Green Metrics and Method Assessment

The implementation of Green Analytical Chemistry requires robust metrics to objectively evaluate and compare the environmental impact of analytical methods. Several assessment tools have been developed, each with distinct approaches and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Tools

| Metric | Approach | Key Parameters | Output Format | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [11] | Semi-quantitative | Persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, waste generation | Pictogram (four quadrants) | Simple, visual; lacks granularity |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [15] | Penalty point system | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste | Numerical score (higher=greener) | Simple calculation; limited scope |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [11] | Semi-quantitative | Multiple criteria across method lifecycle | Color-coded pentagram (5 sections) | Comprehensive lifecycle view; complex application |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [11] | Quantitative weighting | All 12 GAC principles | Circular pictogram (0-1 score) | Most comprehensive; requires software |

| E-Factor [15] | Quantitative | Total waste generated per kg of product | Numerical value (lower=greener) | Simple calculation; ignores hazard |

The E-Factor metric, while originally developed for industrial processes, has been adapted for analytical chemistry applications. In pharmaceutical analysis, E-Factor values typically range from 25 to over 100, significantly higher than other chemical sectors due to stringent purity requirements and multi-step processes [15]. The AGREE metric represents the most recent advancement in green assessment tools, incorporating all 12 GAC principles through a weighted calculation that generates an overall score between 0 and 1, providing a comprehensive and visually intuitive evaluation [11].

Table 2: E-Factor Values Across Chemical Industry Sectors [15]

| Industry Sector | Product Tonnage | E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|---|

| Oil refining | 10â¶-10⸠| <0.1 |

| Bulk chemicals | 10â´-10ⶠ| <1.0 to 5.0 |

| Fine chemicals | 10²-10ⴠ| 5.0 to >50 |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 10-10³ | 25 to >100 |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Green Sample Preparation Techniques

Sample preparation often represents the most environmentally impactful stage of analysis due to solvent consumption and waste generation. Several green sample preparation methodologies have been developed to address this concern:

Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) SPME combines extraction and enrichment into a single, solvent-free process. The protocol involves exposing a silica fiber coated with an appropriate adsorbent phase to the sample matrix, allowing analytes to partition into the coating [12]. After a predetermined extraction time, the fiber is transferred to the analytical instrument for desorption and analysis. Key parameters requiring optimization include fiber coating selection, extraction time, sample agitation, and desorption conditions [12]. The main advantages of SPME include minimal solvent consumption, reduced waste generation, and compatibility with various analytical techniques including GC, HPLC, and their hyphenation with mass spectrometry [12].

QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) The QuEChERS methodology employs a two-stage approach: initial extraction with acetonitrile followed by dispersive solid-phase extraction for cleanup [12]. The standard protocol involves weighing a homogenized sample into a centrifuge tube, adding acetonitrile and buffering salts, then vigorously shaking to partition analytes into the organic phase [12]. After centrifugation, an aliquot of the extract is transferred to a tube containing dispersive SPE sorbents (typically PSA and magnesium sulfate) for cleanup. The mixture is again centrifuged, and the final extract is analyzed directly or after dilution [12]. QuEChERS significantly reduces solvent consumption compared to traditional extraction techniques like liquid-liquid extraction, while maintaining effectiveness for a wide range of analytes.

Direct Chromatographic Analysis

Eliminating sample preparation entirely represents the greenest approach, with direct chromatographic methods offering the most sustainable option when feasible. Direct aqueous injection-gas chromatography (DAI-GC) allows for water sample analysis without extraction, through the injection of aqueous samples directly into GC systems equipped with proper guard columns [12]. Method development must focus on protecting the analytical column from non-volatile matrix components through the use of deactivated pre-columns and optimizing injection parameters to manage water's impact on the chromatographic system [12]. Although limited to relatively clean matrices, direct approaches provide significant environmental benefits by completely eliminating solvent consumption during sample preparation.

Solvent Replacement and Miniaturization Strategies

Chromatographic methods represent major sources of solvent consumption in analytical laboratories. Several strategic approaches can substantially reduce this environmental impact:

Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) SFC utilizes supercritical carbon dioxide as the primary mobile phase, significantly reducing or eliminating the need for organic solvents [13]. Method development involves optimizing parameters such as pressure, temperature, modifier composition and percentage, and stationary phase selection to achieve desired separations [13]. SFC is particularly advantageous for chiral separations and analysis of non-polar to moderately polar compounds, offering dramatically reduced solvent consumption compared to traditional normal-phase HPLC.

UHPLC and Method Transfer Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) systems operating at higher pressures allow the use of columns with smaller particle sizes (sub-2μm), enabling faster separations with reduced solvent consumption [12]. Transferring methods from conventional HPLC to UHPLC platforms typically involves adjusting flow rates, gradient programs, and injection volumes while maintaining the same stationary phase chemistry [12]. This approach can reduce solvent consumption by 50-80% while maintaining or improving chromatographic performance, representing a straightforward path to greener operations for many laboratories.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | HPLC mobile phase | Ethanol/water mixtures | Suitable for reversed-phase chromatography; less toxic [12] |

| Methanol | HPLC mobile phase, extraction solvent | Ethanol | Less hazardous; biodegradable [12] |

| Dichloromethane | Extraction solvent | Ethyl acetate | Less toxic; bio-based options available [9] |

| n-Hexane | Extraction solvent | Cyclopentyl methyl ether | Reduced toxicity; higher boiling point [9] |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Dispersive SPE sorbent | - | Removes fatty acids and sugars in QuEChERS [12] |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Chromatographic mobile phase | - | Replaces organic solvents in SFC [13] |

| Ionic liquids | Alternative solvents | - | Low volatility; tunable properties [13] |

| Endotoxin substrate | Endotoxin substrate, MF:C25H40N8O7, MW:564.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,5-Dipropylfuran | 2,5-Dipropylfuran|High-Purity Reference Standard | 2,5-Dipropylfuran for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Workflows

The transition to greener analytical practices requires systematic implementation. The following workflow diagrams illustrate strategic approaches for method development and technology integration.

Green Analytical Method Development

Analytical Chemistry Paradigm Shift

The paradigm change in analytical chemistry from a narrow focus on analytical performance to a holistic embrace of sustainability principles represents a fundamental metamorphosis of the discipline [1]. This transition is not merely about replacing hazardous solvents or reducing waste, but rather constitutes a comprehensive reimagining of the role and responsibility of analytical science in addressing global sustainability challenges [10]. The principles and drivers of Green and Sustainable Analytical Chemistry are reshaping research priorities, methodological approaches, and educational frameworks across the pharmaceutical and chemical sciences [11]. While significant progress has been made in developing green metrics, alternative methodologies, and miniaturized technologies, the full integration of sustainability principles requires ongoing collaboration across industry, academia, and regulatory bodies [10]. As the field continues to evolve, the commitment to balancing analytical excellence with environmental stewardship will ensure that analytical chemistry maintains its essential role as an enabling science while minimizing its ecological footprint [8]. The ongoing metamorphosis toward greener analytical practices represents not just a technical challenge, but an ethical imperative for the scientific community [1] [10].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has ushered in a significant evolution in pharmaceutical analytical science with the introduction of the Q14 guideline on Analytical Procedure Development and the revised Q2(R2) guideline on Validation of Analytical Procedures [16]. These documents, which reached Step 4 of the ICH process in November 2023 and have since been implemented by major regulatory authorities including the European Commission and the US FDA, represent a fundamental shift from a traditional, prescriptive approach to a more holistic, science- and risk-based framework for the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle (APLC) [17] [18]. This change mirrors the broader paradigm in pharmaceutical development that emphasizes deep process understanding, quality by design (QbD), and risk management, first introduced in small molecule development via ICH Q8 and now being fully realized for analytical sciences. For researchers and drug development professionals, this new landscape offers both challenges and unprecedented opportunities to enhance scientific rigor, regulatory flexibility, and the overall quality of analytical data that underpins drug product quality.

The Evolving Framework: From Q2(R1) to a Lifecycle Approach

The previous regulatory framework, centered primarily on ICH Q2(R1), focused largely on the validation of analytical procedures as a discrete, one-time event. The new framework established by Q14 and Q2(R2) redefines validation as an integral part of a continuous lifecycle [16]. This evolution acknowledges that analytical procedures, like manufacturing processes, evolve and require continual verification and improvement to remain fit for purpose.

A key structural change is the division of the APLC across two complementary guidelines. ICH Q14 focuses on Analytical Procedure Development and lifecycle management, while ICH Q2(R2) covers the Validation of Analytical Procedures [16] [19]. This separation provides more detailed guidance on each stage while emphasizing their interconnectivity. The framework is further supported by ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management) and ICH Q12 (Product Lifecycle Management), creating a cohesive system for managing product and method quality throughout a product's commercial life [16] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core structure and workflow of this new analytical procedure lifecycle.

ICH Q14 Demystified: Analytical Procedure Development

Core Principles and the Enhanced Approach

ICH Q14 provides a structured framework for developing analytical procedures suitable for assessing the quality of both chemical and biological drug substances and products [16] [19]. A foundational concept introduced is the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), defined as a prospective summary of the required quality characteristics of an analytical procedure, expressing the intended purpose of the reportable value and its required quality [16] [19]. The ATP serves as the cornerstone for the entire procedure lifecycle, guiding development, validation, and continual improvement.

The guideline explicitly acknowledges two distinct approaches to development:

- The Minimal Approach: This represents the traditional methodology, focusing on testing identified attributes, selecting technology, conducting development studies, and defining the procedure description [19].

- The Enhanced Approach: This incorporates QbD principles, requiring the definition of an ATP, risk assessment, multivariate experiments, and the establishment of an analytical procedure control strategy and lifecycle change management plan [16] [19].

The enhanced approach, while not mandatory, is encouraged as it provides a systematic way to develop robust procedures and manage knowledge, ultimately facilitating post-approval changes and regulatory flexibility [16].

Key Elements and Their Strategic Importance

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) is the single most important element of the enhanced approach. It ensures the procedure is developed with a clear focus on its intended purpose and performance requirements. The ATP typically includes the analyte, the characteristic to be measured, the required performance criteria, and the conditions under which the measurement will be made [19].

Method Operable Design Region (MODR) is another critical concept, defined as the multivariate combination of analytical procedure input variables that have been demonstrated to provide assurance that the procedure will meet the requirements of the ATP [16]. Establishing a MODR provides flexibility, as changes within this region are not considered as post-approval changes, thereby reducing regulatory burden.

Robustness assessment receives heightened emphasis in Q14. The guideline indicates that robustness should be investigated during the development phase, prior to method validation [20]. This represents a strategic shift, encouraging a deeper understanding of method parameters and their ranges to ensure reliability during routine use.

The following workflow details the key decision points and activities in the enhanced analytical procedure development approach under ICH Q14.

ICH Q2(R2) Decoded: Modernizing Analytical Procedure Validation

What's New and What Remains

ICH Q2(R2) represents an evolution of the well-established validation principles from Q2(R1), expanding its scope and modernizing its application. The fundamental validation characteristics remain unchanged [20]:

- Specificity/Selectivity

- Accuracy/Precision (Repeatability and Intermediate Precision)

- Range/Linearity

However, the revised guideline provides significantly more detail and introduces new concepts. It expands the scope beyond chemical drugs to include biological/biotechnological products and clarifies the application to a broader range of analytical techniques [16] [18]. A notable advancement is the formal recognition of platform analytical procedures for the first time, which can streamline validation for similar molecules, particularly in the biologics space [18].

Key Changes and Implementation Challenges

Robustness: The definition of robustness has evolved from being concerned only with "small, but deliberate changes" to also include consideration of "stability of the sample and reagents" [20]. This broader scope requires a more comprehensive assessment of factors that could impact method performance during routine use.

Combined Accuracy and Precision: Q2(R2) allows for a combined approach to assessing accuracy and precision, which can be a more holistic way to evaluate procedure performance [16] [18]. Industry surveys indicate that 58% of companies are already using or planning to use such combined approaches [18].

Confidence Intervals: The guideline places greater emphasis on reporting confidence intervals for accuracy and precision, expecting the observed intervals to be compatible with acceptance criteria [18]. This has been identified as a significant implementation challenge, with 76% of survey respondents expressing concerns about the meaningfulness of intervals with limited replicates and a lack of internal expertise [18].

Multivariate Procedures: The annexes now include detailed examples for validating procedures based on innovative or multivariate techniques (e.g., NMR, ICP-MS), providing much-needed clarity for these increasingly important methodologies [16] [18].

Practical Implementation: Strategies for Success

A Comparative View of Validation Parameters

The table below summarizes the key validation parameters as outlined in ICH Q2(R2), providing a quick reference for researchers planning validation studies.

Table 1: Key Analytical Procedure Validation Parameters per ICH Q2(R2)

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Typical Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally in the presence of expected components [20]. | Comparison of chromatograms/analytical signals from pure analyte, placebo, and sample to demonstrate separation from interferents. |

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between the conventional true value and the value found [20]. | Spiked recovery experiments using drug product/components or comparison to a validated reference method. |

| Precision | Degree of scatter between a series of measurements from the same homogeneous sample [20]. | Repeated injections/preparations at multiple levels (repeatability, intermediate precision). |

| Repeatability | Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [20]. | Multiple determinations by same analyst, same equipment, short time frame. |

| Intermediate Precision | Establishes effects of random events on precision [20]. | Variations of days, analysts, equipment within the same laboratory. |

| Range/Linearity | The interval between upper and lower concentration for which it has been demonstrated that the procedure has a suitable level of accuracy, precision, and linearity [20]. | Series of concentrations across the claimed range, evaluated by statistical analysis of linearity. |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the Q14 and Q2(R2) principles requires careful selection and control of materials. The following table outlines key reagent solutions and materials critical for robust analytical development and validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Development & Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Quality & Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | To provide a known point of comparison for identity, potency, and impurity quantification; essential for method calibration and specificity/accuracy studies. | Well-characterized, high purity, with Certificate of Analysis (CoA); traceable to primary standards. |

| Critical Reagents | Reagents identified as high-risk through risk assessment (e.g., mobile phase buffers, derivatization agents) that significantly impact method robustness. | Controlled specifications; multiple lots should be tested during robustness studies [20]. |

| System Suitability Solutions | Mixtures to verify that the analytical system is performing adequately at the time of testing, a key part of the Analytical Procedure Control Strategy. | Stable, well-characterized mixtures that can measure key parameters (e.g., resolution, tailing). |

| Stability Study Samples | Samples subjected to stress conditions (heat, light, pH) to demonstrate the stability-indicating nature of the method (Specificity). | Generated under controlled stress conditions to create relevant degradants. |

Protocol for a Modern Robustness Study

In light of the updated guidelines, a science- and risk-based protocol for robustness studies is essential. The following detailed methodology aligns with expectations in both Q14 and Q2(R2).

Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical procedure provides reliable results when influenced by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and under normal, expected operational conditions, including consideration of sample and reagent stability [20].

Experimental Design:

- Risk-Based Parameter Selection: Identify critical method parameters through a prior risk assessment (e.g., Fishbone/ICH Q9). Examples include chromatographic parameters (column temperature, flow rate, pH of mobile phase, wavelength), sample preparation parameters (extraction time, solvent volume, shaking speed), and stability parameters (solution stability, standard and sample holding times) [20].

- Define Test Ranges: Establish realistic ranges for each parameter that represent small, expected variations around the setpoint (e.g., pH ± 0.1 units, temperature ± 2°C).

- Experimental Execution: Using an experimental design (e.g., fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman), systematically vary the selected parameters and measure their effect on Critical Method Performance Indicators (e.g., resolution, tailing factor, assay value, impurity quantification).

- Stability Evaluation: Incorporate studies to evaluate the stability of analytical solutions (standard and sample) under specified storage conditions over time [20].

Data Analysis:

- Use statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA, regression analysis) to identify parameters that have a significant effect on the responses.

- The procedure is considered robust if variations in parameters within the specified ranges do not cause the method performance to fall outside the ATP requirements.

Industry Readiness and Global Implementation

A recent industry survey conducted by ISPE provides a snapshot of the sector's readiness for these new guidelines [18]. While awareness is high, implementation varies, with several key challenges identified:

- Platform Procedures: Over 50% of respondents use platform analytical procedures in clinical development, but only about 10% have secured their approval for commercial products, indicating a significant opportunity for broader adoption and regulatory alignment [18].

- Combined Approaches: 58% of companies are already using or planning to use combined approaches for accuracy and precision, though challenges remain for highly variable methods like those for cell and gene therapies [18].

- Global Harmonization: Despite the ICH's goal of harmonization, a significant challenge is the uneven implementation and understanding across global health authorities, particularly smaller agencies [18].

Training materials were published by the ICH Implementation Working Group in July 2025 to support a harmonized global understanding, illustrating both minimal and enhanced approaches with practical examples [17].

The introduction of ICH Q14 and Q2(R2) marks a definitive paradigm change in analytical chemistry within the pharmaceutical industry. This shift from a discrete, validation-focused activity to an integrated, knowledge-driven Analytical Procedure Lifecycle demands a more strategic and scientifically rigorous approach from researchers and scientists. The enhanced approach, centered on the Analytical Target Profile and supported by risk management, offers a pathway to more robust, flexible, and fit-for-purpose analytical methods.

While challenges in implementation exist—particularly around statistical applications and global regulatory alignment—the long-term benefits of this new framework are clear: enhanced product quality, more efficient post-approval change management, and a stronger foundation for innovation in analytical technologies. For the analytical chemist, embracing this lifecycle mindset is no longer optional but essential for navigating the modern regulatory landscape and driving the development of future medicines.

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from centralized laboratories to the point of need. This paradigm shift is driven by the growing demand for real-time decision-making across various sectors, including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics. Traditional analytical instrumentation, while highly accurate, often requires significant infrastructure, specialized operating expertise, and lengthy sample transport procedures, creating critical delays. The emergence of sophisticated miniaturized technologies is dismantling these barriers, enabling precise chemical analysis at the bedside, in the field, or on the production line. This evolution represents more than mere technical convenience; it constitutes a fundamental change in the operational philosophy of analytical science, prioritizing timeliness, efficiency, and accessibility without compromising data integrity. As the global analytical instrumentation market, estimated at $55.29 billion in 2025, continues its growth trajectory, a significant portion of this expansion is fueled by innovations in portable and miniaturized systems [13].

Market Drivers and Quantitative Growth Trends

The transition toward portable analysis is not occurring in a vacuum. It is propelled by clear market needs and quantitative growth that underscores its strategic importance. Key drivers include the demand for rapid results in clinical settings, the need for on-site detection of environmental pollutants, and the requirement for decentralized quality control in the pharmaceutical industry.

The following table summarizes the projected market growth for key segments related to analytical chemistry, highlighting the significant financial investment and confidence in this evolving field.

Table 1: Analytical Chemistry Market Growth Projections

| Market Segment | 2025 Market Size (USD Billion) | Projected 2030 Market Size (USD Billion) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instrumentation Market [13] | 55.29 | 77.04 | 6.86% |

| Pharmaceutical Analytical Testing Market [13] | 9.74 | 14.58 | 8.41% |

Geographically, the Asia-Pacific region is expected to experience significant growth, driven by expanding pharmaceutical manufacturing and increasing environmental concerns, while North America currently holds the largest share in the pharmaceutical testing sector due to a high concentration of clinical trials and contract research organizations (CROs) [13].

Technological Frontiers in Miniaturization

Core Miniaturization Platforms and Architectures

The push for portability is being realized through several parallel technological advancements:

Micro-Total Analysis Systems (µ-TAS) and Microfluidics: These systems integrate full laboratory functions—including sample preparation, separation, and detection—onto a single chip-scale device. A groundbreaking innovation in this area is the development of pump- and tube-free microfluidic devices. Researchers have created a system where the analyte itself generates a gas (e.g., oxygen from a catalase reaction), creating pressure to drive an ink flow in a connected channel. The flow speed, measured by simple organic photodetectors (OPDs), correlates directly to the analyte concentration, enabling quantitative analysis with minimal hardware [21].

Portable Spectroscopy: Miniaturized Near-Infrared (NIR) spectrometers have become well-established tools. Their effectiveness, however, relies heavily on robust chemometric data analysis strategies to extract meaningful information from the complex data they generate [22].

Advanced Sample Preparation Materials: Effective analysis of complex samples requires pre-concentration and clean-up. Functionalized monoliths are particularly suited for miniaturized systems. Their porous structure allows for high flow rates with low backpressure. When functionalized with biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) or engineered as Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), they provide high selectivity, eliminating matrix effects that often plague LC-MS analyses [23]. Their miniaturization into capillaries or chips is essential for integration with portable nanoLC systems, reducing solvent consumption and cost [23].

The Critical Role of Green Chemistry

The miniaturization trend aligns perfectly with the principles of green analytical chemistry. Techniques such as micro-extraction, miniaturized SPE, and capillary-scale separations dramatically reduce solvent consumption and waste generation, aligning analytical practices with global sustainability goals [13] [24]. This is not merely a peripheral benefit but a core guiding principle for the development of new methods, as the field increasingly prioritizes environmentally benign procedures [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pump-Free Microfluidic CRP Detection

To illustrate the practical implementation of a portable device, the following is a detailed methodology based on a published approach for quantifying C-reactive protein (CRP), a key clinical biomarker [21].

Principle

The assay quantifies CRP by measuring the flow rate of an ink solution pushed by oxygen gas generated in a catalase-linked enzymatic reaction. The CRP in the sample is captured on a surface, and catalase-labeled nanoparticles are bound proportionally. Upon addition of hydrogen peroxide, the bound catalase produces oxygen, creating pressure that drives the ink flow. The higher the CRP concentration, the faster the ink flows.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Pump-Free CRP Detection

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| CRP-Specific Antibodies | Used to functionalize the chamber surface for capturing CRP from the sample. |

| Catalase-Conjugated Nanoparticles | Secondary detection particles; catalase enzyme generates the oxygen gas that drives the fluidics. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) Solution | Substrate for the catalase enzyme. Its decomposition produces Oâ‚‚ gas. |

| Ink Solution | A visually opaque fluid whose flow rate is the measurable output of the assay. |

| Organic Photodetectors (OPDs) | Printed, inexpensive sensors that detect the passage of the ink by measuring blocked light. |

| Microfluidic Chip with Integrated Chambers | The core platform, featuring a sample chamber and an connected ink channel. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Surface Functionalization: The sample chamber is pre-treated with CRP-specific antibodies to create a capture surface.

- Sample Incubation: A solution containing the analyte (e.g., human serum with CRP) is added to the chamber. CRP antigens bind to the immobilized antibodies.

- Washing: Unbound sample components are washed away.

- Detection Probe Incubation: Catalase-coated nanoparticles, which are also conjugated with CRP antibodies, are added. These bind to the captured CRP, forming a "sandwich" complex. The amount of bound catalase is proportional to the initial CRP concentration.

- Second Washing: Unbound nanoparticles are removed.

- Reaction Initiation: A solution of hydrogen peroxide is introduced into the chamber.

- Gas Generation & Detection: The bound catalase decomposes Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ into water and oxygen gas. The gas pressure displaces the ink in the connected channel.

- Data Acquisition: The OPDs record the time taken for the ink front to pass between two set points. This flow rate is the primary data.

- Quantification: The flow rate is compared against a calibration curve of known CRP concentrations to determine the concentration in the unknown sample.

The workflow below visualizes this integrated analytical process.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promising advancements, the widespread adoption of miniaturized devices faces several hurdles. The high initial cost of advanced instruments and the significant skill gap in operating these new tools and interpreting complex data remain barriers for many laboratories [13]. Furthermore, effective data management and analysis infrastructures are needed to handle the volume of information generated by these technologies [13].

Looking beyond 2025, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and predictive modeling will further optimize analytical processes and data interpretation [13]. Quantum sensors show potential for unprecedented sensitivity in environmental and biomedical applications [13]. The rise of the Internet of Things (IoT) will enable "smart" connected laboratories and portable devices, facilitating real-time monitoring and control [13]. Finally, the fusion of portable devices with big data and artificial intelligence is poised to create powerful networks for remote monitoring and complex problem-solving [24].

The transition to on-site and miniaturized analytical devices is a definitive paradigm change in chemical research and application. This shift is powered by technological innovations in microfluidics, materials science, and detection methodologies, all converging to create powerful, portable, and increasingly sustainable analytical tools. While challenges related to cost and expertise persist, the trajectory is clear: analytical chemistry is moving out of the centralized laboratory and into the field, the clinic, and the factory. This evolution empowers researchers and drug development professionals with immediate, data-driven insights, ultimately accelerating scientific discovery and enhancing decision-making across the spectrum of science and industry.

The analytical instrumentation sector is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, evolving from a supportive role into a primary enabler of scientific advancement across diverse fields. This transformation is encapsulated in the metamorphosis of analytical chemistry from performing simple, problem-driven measurements to conducting holistic, discovery-driven analyses that generate complex, multi-parametric data [8]. Within this context, the global analytical instrumentation market has demonstrated robust growth, with its value increasing from USD 57.37 billion in 2024 to an estimated USD 60.22 billion in 2025. Projections indicate a rise to USD 84.77 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.99% [25]. Alternative forecasts suggest an even more accelerated growth trajectory, with the market potentially reaching USD 115.17 billion by 2034 [26]. This expansion is fundamentally driven by rising research complexity, heightened regulatory requirements, and an escalating need for precision in quality assurance across scientific and industrial verticals [25]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the market forces shaping this dynamic sector, detailing its quantitative trajectory, primary growth drivers, and the evolving methodologies that define its future.

The analytical instrumentation market is characterized by its vital role in identification, separation, and quantification of chemical substances, serving as a backbone for clinical diagnostics, life sciences research, and therapeutic development [26]. The market's growth is underpinned by substantial demand from key end-user sectors, including pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, food and beverage, and environmental monitoring [25] [27].

Table 1: Global Analytical Instrumentation Market Size Projections

| Base Year | Base Year Value (USD Billion) | Forecast Period | Projected Value (USD Billion) | CAGR (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 54.85 | 2025-2034 | 115.17 | 7.70 | [26] |

| 2024 | 60.22 | 2025-2032 | 84.77 | 4.99 | [25] |

| 2024 | 51.22 | 2025-2032 | 76.56 | 5.90 | [27] |

| 2024 | 60.00 | 2025-2034 | 111.40 | 6.50 | [28] |

This growth is not uniform across all segments. A detailed segmentation reveals distinct areas of emphasis and opportunity.

Table 2: Market Segmentation by Product, Technology, and Application (2024-2025)

| Segmentation Category | Leading Segment | Market Share or Value | Key Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Product | Instruments | 52.9% share (2025) [27] | Superior analytical capabilities, versatility, integration of automation and digital technologies [27]. |

| By Technology | Spectroscopy | USD 17.9 Billion (2024) [28] | Demand for precise, non-destructive analytical techniques in R&D; integration of AI and ML [28]. |

| By Technology | Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | 40.3% share (2025) [27] | High sensitivity and specificity; growing demand in molecular diagnostics and life sciences research [27]. |

| By Application | Life Sciences R&D | 42.1% share (2025) [27] | Advancements in drug development, personalized medicine, and complex clinical trials [27] [28]. |

| By End Use | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Industry | USD 28.1 Billion (2024) [28] | Rising R&D expenditures, focus on biopharmaceuticals and personalized medicine, stringent quality control [28]. |

Regional analysis highlights the Asia-Pacific region as the fastest-growing market, fueled by a large and expanding industrial base, increasing R&D investments, and a strong focus on automation [27]. Meanwhile, established markets like the United States, valued at USD 21.5 billion in 2024, continue to grow steadily, driven by their robust pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries and strict environmental and safety regulations [28].

Primary Market Forces and Growth Drivers

Regulatory Stringency and Quality Control Imperatives

Globally, stringent regulations are compelling industries to adopt advanced analytical tools for compliance. In the pharmaceutical sector, regulations like Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) set by the FDA mandate thorough testing and validated methods to ensure product safety and quality [26] [27]. Similarly, environmental regulations from bodies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) drive demand for instruments that monitor pollutants in air and water [26]. This regulatory climate necessitates investment in state-of-the-art instrumentation to ensure data integrity and compliance, making it a powerful market driver.

Expansion in Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology R&D

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry is a pivotal force, accounting for a dominant share of the market [28]. The escalating prevalence of chronic and infectious diseases has intensified the need for innovative drug discovery and development. Analytical instruments are indispensable at every stage, from drug discovery and formulation development to clinical trials and quality control in commercial manufacturing [27]. The surge in biopharmaceuticals, including monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and cell and gene therapies, has further catalyzed the adoption of advanced tools for precise molecular analysis and biomarker discovery [28].

Technological Transformation and Innovation

The sector is being reshaped by several interconnected technological trends:

- Automation and AI Integration: Automation in data collection, sample analysis, and reporting is becoming prevalent. AI-driven systems enhance accuracy, reduce human error, and enable real-time analysis and predictive insights, thereby optimizing workflows [25] [28].

- Miniaturization and Portability: There is a growing trend toward developing smaller, compact devices that maintain high performance. These portable instruments are cost-effective and convenient for field testing, expanding the applications of analytical instrumentation into new, on-site environments [27] [28].

- Hyphenated Techniques and Data Handling: Modern techniques, such as UHPLC coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry, produce enormous, complex datasets. This shift requires new approaches to data management and analysis, positioning analytical chemistry as a generator of "big data" [8].

Analytical Frameworks for Market and Technical Analysis

Understanding the complex trajectories within the analytical instrumentation sector requires robust methodological frameworks. Researchers and strategic analysts can adapt several comparative and quantitative approaches to dissect market dynamics and technological integration.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) for Implementation Success

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a methodology suited for analyzing intermediate numbers of cases (e.g., 10-50) to identify combinations of conditions that lead to a specific outcome [29] [30]. This is particularly useful for understanding the successful implementation of new analytical technologies or strategies within an organization.

Experimental Protocol for a QCA Study:

- Define the Outcome: Clearly articulate the outcome of interest (e.g., "Successful implementation of a new laboratory information management system").

- Select Cases: Identify a set of cases that exhibit the outcome and a set that does not. For example, select 10-15 laboratories where implementation was successful and a similar number where it was not [29] [30].

- Identify Causal Conditions: Based on theory and prior knowledge, select conditions hypothesized to influence the outcome (e.g., "Strong organizational capacity," "Comprehensive planning process," "Adequate funding," "Staff training adequacy") [29].

- Data Collection and Calibration: Gather data for each case on each condition. Calibrate the data into sets using crisp-set (0 or 1) or fuzzy-set (0 to 1) scores to denote the presence or degree of each condition [30].

- Construct a Truth Table: Build a truth table listing all logically possible combinations of conditions and the observed outcome for the cases matching each combination.

- Boolean Minimization: Use software (e.g., fs/QCA) to analyze the truth table via Boolean algebra. This process simplifies the complex combinations of conditions to identify the minimal configurations that are sufficient for the outcome [29] [30].

- Interpretation and Validation: Interpret the resulting configurations (e.g., "The combination of strong organizational capacity AND comprehensive planning is sufficient for successful implementation"). Validate the findings by returning to the case studies to ensure the solution makes sense [30].

Diagram: QCA Methodology Workflow

Quantitative Comparative Analysis for Strategic Positioning

Quantitative comparisons based on well-defined variables allow for strategic analysis across companies, regions, or product segments [31]. This approach can illuminate how different entities deal with general market forces.

Methodology for Quantitative Comparison:

- Variable Selection: Identify simple, salient, and objective quantitative variables for comparison. In a market context, these could include R&D expenditure as a percentage of sales, year-over-year growth rate in specific product segments, or geographic revenue distribution [31].

- Data Sourcing: Collect data from standardized sources, such as company annual reports, industry consortiums, and market research publications, to ensure comparability [32] [33].

- Statistical Characterization: Analyze the data to characterize the distribution of key metrics. This could involve creating rank-size distributions for company market share or analyzing the relationship between R&D investment and market growth [31].

- Contextual Interpretation: Interpret the quantitative findings within the specific contextual factors of each case, such as regional regulatory climates or corporate strategy, to draw meaningful strategic insights [31] [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective operation of modern analytical instrumentation relies on a suite of supporting reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions essential for experimental workflows in this sector.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Analytical Instrumentation

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provide a certified value for a specific property to calibrate instruments and validate methods. | Ensuring accuracy in trace element analysis using ICP-MS [27]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Act as internal standards in mass spectrometry to correct for matrix effects and quantification errors. | Precise quantification of drugs and metabolites in complex biological matrices during pharmacokinetic studies [27]. |

| Chromatography Columns and Sorbents | Facilitate the separation of complex mixtures into individual components based on chemical properties. | HPLC and UHPLC for purity testing and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) characterization [27] [26]. |

| Enzymes and Master Mixes | Catalyze specific biochemical reactions under controlled conditions. | Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for amplifying specific DNA sequences in diagnostics and genetic testing [27] [8]. |

| High-Purity Solvents and Mobile Phase Additives | Serve as the carrier medium for samples in separation techniques, affecting resolution and efficiency. | Preparing mobile phases for liquid chromatography to achieve optimal separation of analytes [27]. |

| 2-Acetamidobenzoyl chloride | 2-Acetamidobenzoyl Chloride|CAS 64180-31-0 | |

| 7-Nitro-1H-indazol-6-OL | 7-Nitro-1H-indazol-6-OL|Research Chemical | High-purity 7-Nitro-1H-indazol-6-OL for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

The Integrated Future: AI and the Connected Laboratory

The next paradigm shift in the analytical instrumentation sector is the movement toward fully integrated, data-driven laboratory environments. The convergence of AI, IoT, and automation is creating a new ecosystem for scientific discovery.

Diagram: Technology Integration in Modern Lab

This integration enables predictive maintenance by detecting performance anomalies from sensor data, remote operation and monitoring of highly specialized instruments, and the growth of smart labs where all instruments and infrastructure are centrally managed on a digital platform [27]. This drives consistency, improves regulatory compliance, and fosters collaborative research across geographic boundaries, ultimately accelerating the pace of scientific innovation.

The analytical instrumentation sector is on a strong growth trajectory, fundamentally shaped by the paradigm change of becoming an enabling science. Its evolution is driven by relentless regulatory demands, expansive R&D in the life sciences, and transformative technological innovations. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, navigating this landscape requires an understanding of both the quantitative market forces and the sophisticated analytical frameworks needed to decode them. The future of the sector lies in its increasing integration, intelligence, and indispensability in solving the world's most complex scientific challenges.

Modern Methodologies in Action: From Self-Driving Labs to Advanced QC

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional manual methodologies toward an era of intelligent, automated research systems. This paradigm shift, driven by the emergence of self-driving laboratories (SDLs), represents the latest in a series of revolutionary changes that have periodically reshaped chemical science—from the transition from alchemy to systematic chemistry, to the incorporation of quantum mechanics, and more recently, to the adoption of green chemistry principles [34]. SDLs combine artificial intelligence (AI) with robotic automation to execute multiple cycles of the scientific method with minimal human intervention, fundamentally accelerating the pace of discovery in chemistry and materials science [35] [36]. This transformation addresses pressing global challenges in energy, healthcare, and sustainability that demand research solutions at unprecedented speeds [35] [37]. By integrating automated experimental workflows with data-driven decision-making, SDLs are not merely incremental improvements but represent a fundamental restructuring of the research process itself—a true paradigm shift that is redefining the roles of human researchers and machines in scientific discovery.

The Architecture of Autonomy: Technical Foundations of SDLs

Defining the Self-Driving Laboratory

A self-driving laboratory is an integrated system comprising automated experimental hardware and AI-driven software that work in concert to achieve human-defined research objectives [37]. Unlike conventional automated equipment that simply executes predefined protocols, SDLs incorporate a closed-loop workflow where experimental results continuously inform and refine the AI's selection of subsequent experiments [35]. This creates an iterative cycle of hypothesis generation, experimentation, and learning that dramatically accelerates the optimization of materials, molecules, or processes [38].

The core innovation of SDLs lies in their ability to navigate complex experimental spaces with an efficiency unattainable through human-led experimentation [39]. As one researcher notes, "SDL can navigate and learn complex parameter spaces at a higher efficiency than the traditional design of experiment (DOE) approaches" [39]. This capability is particularly valuable for multidimensional optimization problems where interactions between variables create landscapes too complex for human intuition to traverse effectively.

Classification and Levels of Autonomy

SDLs can be classified according to their level of autonomy, similar to the system used for self-driving vehicles [35] [36]. Two complementary frameworks have emerged to characterize this autonomy:

a) Integrated Autonomy Levels: This framework defines five levels of scientific autonomy, with most current SDLs operating at Level 3 (conditional autonomy) or Level 4 (high autonomy) [36]:

- Level 1 (Assisted Operation): Machine assistance with specific laboratory tasks (e.g., robotic liquid handlers)

- Level 2 (Partial Autonomy): Proactive scientific assistance, such as AI-generated experimental protocols

- Level 3 (Conditional Autonomy): Autonomous performance of at least one full cycle of the scientific method, requiring human intervention only for anomalies

- Level 4 (High Autonomy): Systems capable of automating protocol generation, execution, data analysis, and hypothesis adjustment

- Level 5 (Full Autonomy): Complete automation of the scientific method—not yet achieved [36]

b) Two-Dimensional Autonomy Framework: This alternative system evaluates autonomy separately across hardware and software dimensions [35]. Hardware autonomy ranges from manual experiments (Level 0) to fully automated laboratories (Level 3), while software autonomy progresses from human ideation (Level 0) to generative approaches where computers define both search spaces and experiment selection (Level 3) [35]. In this framework, a true Level 5 SDL would achieve Level 3 in both dimensions—a milestone that remains unrealized [35].

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow of a closed-loop SDL system:

Performance Metrics: Quantifying SDL Effectiveness

As SDL technologies mature, standardized performance metrics have emerged to enable meaningful comparison across different platforms and applications. These metrics provide crucial insights into the capabilities and limitations of various SDL architectures [39].

Key Performance Indicators for SDLs

Table 1: Essential Performance Metrics for Self-Driving Laboratories

| Metric | Description | Reporting Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Degree of Autonomy | Extent of human intervention required for regular operation | Classify as piecewise, semi-closed-loop, or closed-loop [39] |

| Operational Lifetime | Total time platform can conduct experiments | Report demonstrated vs. theoretical, and assisted vs. unassisted [39] |

| Throughput | Rate of experiment execution | Include both sample preparation and measurement phases; report demonstrated and theoretical maximum [39] |

| Experimental Precision | Reproducibility of experimental platform | Quantify using unbiased sequential experiments under optimization conditions [39] |

| Material Usage | Total quantity of materials consumed per experiment | Break down by active quantity, total used, hazardous materials, and high-value materials [39] |

| Optimization Efficiency | Performance of experiment selection algorithm | Benchmark against random sampling and state-of-the-art selection methods [39] |

Throughput deserves particular attention as it often represents the primary bottleneck in exploration of complex parameter spaces. It is influenced by multiple factors including reaction times, characterization method speed, and parallelization capabilities [39]. Notably, recent advances have demonstrated dramatic improvements in this metric—a newly developed dynamic flow SDL achieves at least 10 times more data acquisition than previous steady-state systems by continuously monitoring reactions instead of waiting for completion [38] [40].

Operational lifetime must be contextualized by distinguishing between demonstrated and theoretical capabilities. For example, one microfluidic SDL demonstrated an unassisted lifetime of two days (limited by precursor degradation) but an assisted lifetime of one month with regular maintenance [39]. This distinction is crucial for understanding the practical labor requirements and scalability of SDL platforms.

Implementation Architectures: Experimental Frameworks and Reagent Systems

Breakthrough Experimental Protocols

Recent advances in SDL methodologies have introduced transformative experimental approaches that dramatically accelerate materials discovery:

Dynamic Flow Experimentation: Traditional SDLs utilizing continuous flow reactors have relied on steady-state flow experiments, where the system remains idle during chemical reactions that can take up to an hour to complete [38]. A groundbreaking approach developed at North Carolina State University replaces this with dynamic flow experiments, where chemical mixtures are continuously varied through the system and monitored in real-time [38] [40].

This methodology enables the system to operate continuously, capturing data every half-second throughout reactions rather than single endpoint measurements [40]. As lead researcher Milad Abolhasani explains, "Instead of having one data point about what the experiment produces after 10 seconds of reaction time, we have 20 data points—one after 0.5 seconds of reaction time, one after 1 second of reaction time, and so on. It's like switching from a single snapshot to a full movie of the reaction as it happens" [38]. This "streaming-data approach" provides the AI algorithm with substantially more high-quality experimental data, enabling smarter, faster decisions and reducing the number of experiments required to reach optimal solutions [40].

Flow-Driven Data Intensification: Applied to the synthesis of CdSe colloidal quantum dots, this dynamic flow approach yielded an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency while reducing both time and chemical consumption compared to state-of-the-art fluidic SDLs [38]. The system successfully identified optimal material candidates on the very first attempt after training, dramatically accelerating the discovery pipeline [40].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

SDL platforms require specialized materials and reagents tailored to automated, continuous-flow environments. The following table details key components for advanced SDL systems, particularly those focused on nanomaterials discovery:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDL Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in SDL Context | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Continuous Flow Reactors | Enable dynamic flow experiments with real-time monitoring | Fundamental architecture for high-throughput screening and optimization [38] |

| CdSe Precursor Chemicals | Model system for quantum dot synthesis and optimization | Used as testbed for demonstrating dynamic flow experimentation advantages [38] |

| Real-time Characterization Sensors | In-line monitoring of material properties during synthesis | Critical for capturing transient reaction data in dynamic flow systems [38] |

| AI-Driven Experiment Selection Algorithms | Autonomous decision-making for next experiment choice | "Brain" of the SDL that improves with more high-quality data [40] |

The integration of these components creates a highly efficient discovery engine. As demonstrated in the NC State system, the combination of dynamic flow reactors with real-time monitoring and AI decision-making reduces chemical consumption and waste while accelerating discovery—advancing both efficiency and sustainability goals [38].

The Future Evolution of SDLs: Towards Democratization and Specialization

The ongoing evolution of SDL technologies points toward two complementary futures: centralized facilities offering shared access to advanced capabilities, and distributed networks of specialized platforms enabling targeted research [37].

Centralized facilities (analogous to CERN in particle physics) would concentrate resources and expertise, providing broad access to sophisticated instrumentation through virtual interfaces [37]. This model offers economic advantages through shared infrastructure and potentially more straightforward regulatory compliance for hazardous materials [37].

Distributed networks of smaller, specialized SDLs would leverage modular designs and open-source platforms to create collaborative ecosystems [37]. This approach favors flexibility and rapid adaptation to emerging research needs, potentially lowering barriers to entry through developing low-cost automation solutions [37].

A hybrid model may ultimately emerge, where individual laboratories develop and refine experimental workflows using simpler systems before deploying them at scale in centralized facilities [37]. This combines the flexibility of distributed development with the power of centralized execution.

The philosophical implications of this technological shift are profound. SDLs represent both the culmination and transformation of reductionist approaches in chemistry, enabling unprecedented exploration of complex, multidimensional parameter spaces while potentially fostering more integrative perspectives on chemical systems [34]. As these technologies mature, they promise not only to accelerate discovery but to fundamentally reshape how we conceptualize and pursue chemical research.