Statistical Analysis for Method Comparison Acceptance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for designing, executing, and interpreting method comparison studies to ensure regulatory acceptance and scientific validity in biomedical and clinical research.

Statistical Analysis for Method Comparison Acceptance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

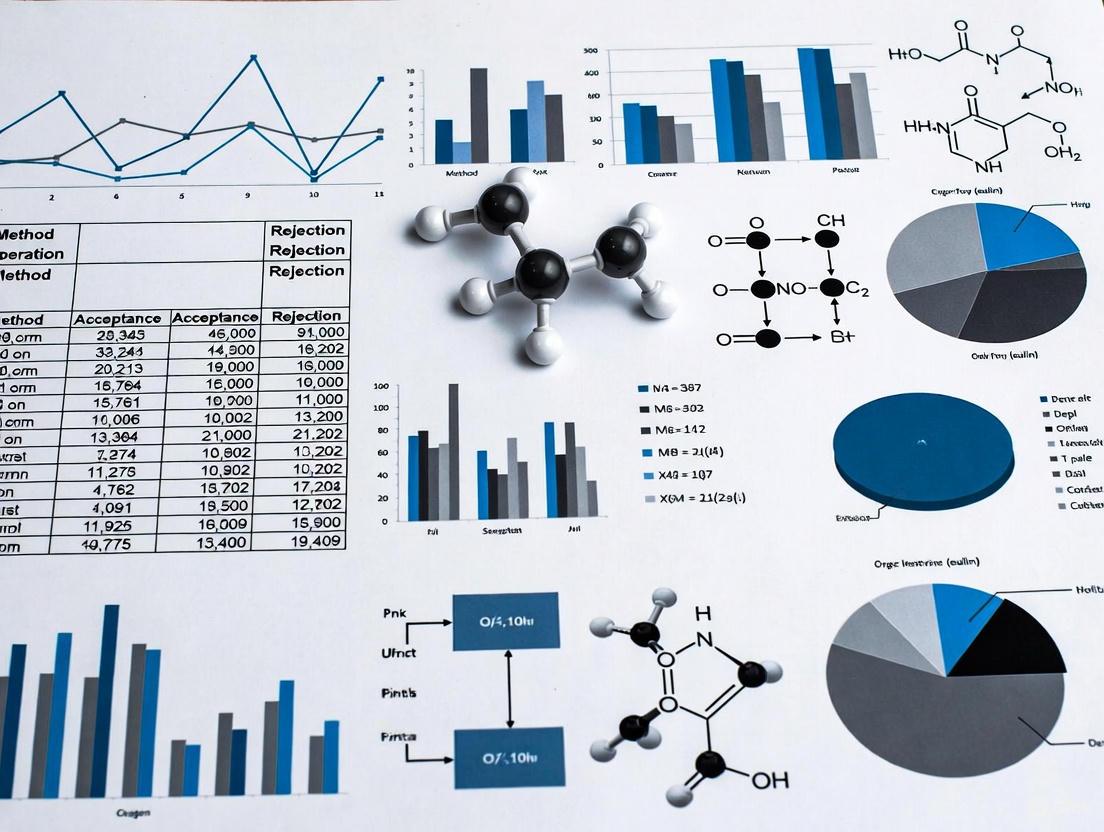

This article provides a comprehensive framework for designing, executing, and interpreting method comparison studies to ensure regulatory acceptance and scientific validity in biomedical and clinical research. It guides researchers through foundational concepts, appropriate statistical methodologies, troubleshooting of common pitfalls, and validation strategies. Covering key topics from CLSI EP09-A3 standards and Milano hierarchy for performance specifications to practical application of Deming regression, Bland-Altman plots, and bias estimation, this guide equips professionals with the knowledge to demonstrate that new and established methods can be used interchangeably without affecting patient results or clinical outcomes.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Method Comparison Studies

In the field of drug development and biomedical research, method comparison studies are fundamental for assessing the comparability of measurement procedures. These studies are conducted whenever a new analytical method is introduced to replace an existing one, with the primary goal of determining whether the two methods can be used interchangeably without affecting patient results and clinical outcomes. The core question these studies address is whether a significant bias exists between methods. If the bias is larger than a pre-defined acceptable limit, the methods are considered different and not interchangeable for clinical use [1].

The quality of a method comparison study directly determines the validity of its conclusions, emphasizing the need for careful planning and appropriate statistical design. A well-executed method comparison assesses the degree of agreement between the current method (often considered the reference) and the new method (the comparator). This process is a key aspect of method verification, specifically for assessing method trueness, and can be performed following established standards such as CLSI EP09-A3, which provides guidance on estimating bias using patient samples [1].

Key Concepts and Experimental Protocols

Fundamental Study Design and Protocol

A robust method comparison experiment requires meticulous design to ensure results are reliable and actionable. The following protocol outlines the critical steps:

- Sample Selection and Sizing: The study should utilize a minimum of 40 and preferably 100 patient samples. A larger sample size enhances the ability to detect unexpected errors stemming from interferences or sample matrix effects. Samples must be carefully selected to cover the entire clinically meaningful measurement range [1].

- Measurement Replication: To minimize the impact of random variation, duplicate measurements for both the current and new method are recommended. The mean of duplicate measurements (or the median for triplicate or more) should be used for data plotting and analysis [1].

- Sample Handling and Randomization: Samples must be analyzed within their stability period, ideally within 2 hours of blood sampling, and on the same day the sample was collected. The sample sequence should be randomized to avoid carry-over effects, and measurements should be conducted over several days (at least 5) and across multiple runs to simulate real-world conditions [1].

- Defining Acceptance Criteria: Prior to the experiment, the acceptable bias must be defined. Performance specifications should be based on one of the models in the Milano hierarchy, which includes criteria based on the effect on clinical outcomes, components of biological variation of the measurand, or state-of-the-art capabilities [1].

Statistical Protocols and Data Analysis Workflow

The analytical phase involves specific statistical protocols to quantify agreement and detect bias.

- Initial Graphical Analysis: The first step in data analysis is the graphical presentation of data using scatter plots and difference plots. Scatter plots help visualize the variability in paired measurements across the measurement range and can reveal outliers, extreme values, or gaps in the data coverage that must be addressed before further analysis [1].

- Bland-Altman Analysis for Bias Estimation: Difference plots, specifically Bland-Altman plots, are used to assess agreement. In this analysis, the differences between the two methods are plotted on the y-axis against the average of the two methods on the x-axis. The mean of the differences provides an estimate of the average bias between the methods. The limits of agreement (LoA), calculated as the mean difference ± 1.96 times the standard deviation of the differences, estimate the interval within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are likely to fall. These limits are used to judge whether the methods can be used interchangeably [2].

- Advanced Regression Techniques: For a more detailed analysis of the relationship between methods, advanced regression techniques such as Deming regression or Passing-Bablok regression are recommended. These methods are designed to handle measurement errors in both methods, unlike ordinary least squares regression [1].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of a method comparison study:

Inappropriate Statistical Methods

It is critical to understand why certain common statistical methods are inadequate for assessing method comparability. Correlation analysis is often misused; it measures the strength of a linear relationship (association) between two methods but cannot detect proportional or constant bias. A perfect correlation coefficient (r = 1.00) can exist even when two methods are giving vastly different values, demonstrating that high correlation does not imply agreement [1].

Similarly, the t-test is not adequate for this purpose. An independent t-test only determines if two sets of measurements have similar averages, which can be misleading. A paired t-test, while better suited for paired measurements, may detect statistically significant differences that are not clinically meaningful if the sample size is very large, or fail to detect large, clinically important differences if the sample size is too small [1].

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

Structured Data from Comparison Studies

The following table summarizes quantitative results from a hypothetical method comparison study, illustrating the type of data generated and how bias and limits of agreement are calculated. This example evaluates the interchangeability of two glucose measurement methods.

Table 1: Example Data and Bias Calculations from a Glucose Method Comparison Study

| Sample ID | Reference Method (mmol/L) | New Method (mmol/L) | Difference (New - Ref) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 6.2 | 6.0 | -0.2 |

| 4 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 0.5 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Mean | 6.5 | 6.8 | 0.3 |

| Std Dev | - | - | 0.25 |

Key Metrics:

- Average Bias (Mean Difference): 0.3 mmol/L

- Standard Deviation of Differences: 0.25 mmol/L

- Lower Limit of Agreement: 0.3 - (1.96 × 0.25) = -0.19 mmol/L

- Upper Limit of Agreement: 0.3 + (1.96 × 0.25) = 0.79 mmol/L [2]

The final interpretation involves comparing these calculated limits of agreement to the pre-defined clinically acceptable bias. If the interval from -0.19 to 0.79 mmol/L is deemed too wide for clinical purposes, the methods are not interchangeable.

Performance Metrics in Related Fields

The principles of performance evaluation are also applied in computational drug discovery. For example, drug-repurposing technologies like the CANDO platform use metrics such as Average Indication Accuracy (AIA) to benchmark their predictions. This metric evaluates the platform's ability to correctly rank drugs associated with the same indication within a specified cutoff (e.g., the top 10 most similar drugs). In one reported instance, CANDO v1 achieved a top10 AIA of 11.8%, significantly higher than a random control of 0.2% [3].

In drug response prediction modeling, performance is often evaluated using the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R-squared (R²) values. A recent study comparing machine learning and deep learning models for predicting drug response (ln(IC50)) reported RMSE values ranging from 0.274 to 2.697 for traditional ML models across 24 different drugs [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of method comparison studies relies on a suite of methodological tools and statistical solutions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Method Comparison Studies

| Tool/Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Patient Samples | Biological specimens used to cover the clinically meaningful measurement range and assess real-world performance [1]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Analyse-it) | Used to perform advanced statistical analyses, including Deming regression, Bland-Altman plots, and calculation of limits of agreement [2]. |

| CLSI EP09-A3 Guideline | Provides the standard protocol for designing and executing method comparison studies using patient samples to estimate bias [1]. |

| Bland-Altman Plot | A graphical method to visualize the agreement between two methods, plot the average bias, and establish the limits of agreement for interchangeability [1] [2]. |

| Deming & Passing-Bablok Regression | Statistical methods used to model the relationship between two methods while accounting for measurement errors in both variables, providing a more accurate analysis than simple linear regression [1]. |

| Random Number Generator | A tool (e.g., in Excel or specialized software) used to generate a randomization sequence for allocating samples or experimental units, a key step to minimizing bias in the study conduct [5]. |

| MEDICA16 | MEDICA16, CAS:87272-20-6, MF:C20H38O4, MW:342.5 g/mol |

| 1,3,5-Trihydroxyxanthone | 1,3,5-Trihydroxyxanthone, CAS:6732-85-0, MF:C13H8O5, MW:244.20 g/mol |

Visualizing the Bias Assessment Workflow

The process of analyzing data from a method comparison study to assess bias and agreement follows a structured path, as illustrated in the following diagram:

In the field of clinical laboratory sciences and pharmaceutical development, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline EP09-A3—titled Measurement Procedure Comparison and Bias Estimation Using Patient Samples—represents the current standard for evaluating the comparability of quantitative measurement procedures. This approved guideline, now in its third edition, provides the critical statistical and experimental framework for determining the bias between two measurement methods, thereby ensuring the reliability and interchangeability of data in both research and clinical decision-making [6]. The fundamental question addressed by EP09-A3 is whether two methods can be used interchangeably without affecting patient results and clinical outcomes [1]. Its application spans manufacturers of in vitro diagnostic (IVD) reagents, developers of laboratory-developed tests, regulatory authorities, and medical laboratory personnel who must verify method performance during technology changes, instrument replacements, or implementation of new assays [6].

The evolution from its predecessor (EP09-A2) to the current EP09-A3 edition reflects significant methodological advancements. The third edition, corrected in 2018, places greater emphasis on the process of performing measurement procedure comparisons, more robust regression techniques including weighted Deming and Passing-Bablok, and comprehensive bias estimation with confidence intervals at clinically relevant decision points [6]. This guideline is specifically designed for measurement procedures yielding quantitative numerical results and is not intended for qualitative tests, evaluation of random error, or total error assessment, which are covered in other CLSI documents such as EP12, EP05, EP15, and EP21 [6].

Core Principles and Experimental Design in EP09-A3

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

The EP09-A3 guideline establishes a standardized terminology framework essential for proper method comparison studies. Central to this framework is the concept of bias—the systematic difference between measurement procedures—which must be quantified and evaluated against predefined performance criteria [6]. The guideline emphasizes trueness assessment through comparison against a reference or comparative method, moving beyond simple correlation analysis to more sophisticated statistical approaches that detect both constant and proportional biases [1]. Understanding these key concepts is critical for designing compliant experiments and correctly interpreting results.

Essential Experimental Design Requirements

The EP09-A3 protocol mandates specific design elements to ensure statistically valid and clinically relevant comparisons:

Sample Requirements and Selection: The guideline recommends using at least 40 patient samples, with 100 samples being preferable to identify unexpected errors due to interferences or sample matrix effects. Samples must be carefully selected to cover the entire clinically meaningful measurement range and should represent the typical patient population [1]. When possible, duplicate measurements for both the current and new method should be performed to minimize random variation effects [1].

Sample Analysis Protocol: The analysis of samples should occur within their stability period (preferably within 2 hours of blood sampling) and on the day of collection [1]. The guideline recommends measuring samples over several days (at least 5) and multiple runs to mimic real-world testing conditions and account for routine variability [1]. Sample sequence should be randomized to avoid carry-over effects, and quality control procedures must be implemented throughout the testing process [1].

Defining Acceptable Performance: Before conducting the experiment, laboratories must define acceptable bias specifications based on one of three models in accordance with the Milano hierarchy: (1) based on the effect of analytical performance on clinical outcomes, (2) based on components of biological variation of the measurand, or (3) based on state-of-the-art capabilities [1].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and workflow in designing an EP09-A3-compliant method comparison study:

Statistical Analysis Framework and Data Interpretation

Visual Data Exploration Techniques

EP09-A3 emphasizes visual data inspection as a critical first step in method comparison studies before quantitative analysis. Two primary graphical methods are recommended:

Scatter Plots: These diagrams plot measurements from the comparative method (x-axis) against the experimental method (y-axis), allowing initial assessment of the relationship between methods across the measurement range. The scatter plot helps identify linearity, potential outliers, and gaps in the data distribution that might require additional sampling [1]. When duplicate measurements are performed, the mean or median of replicates should be used for plotting [1].

Difference Plots (Bland-Altman Plots): These plots display the differences between methods (y-axis) against the average of both methods (x-axis), enabling direct visualization of bias across the measurement range. Difference plots help identify constant or proportional bias, outliers, and potential trends where disagreement between methods may change with concentration levels [6] [1].

Quantitative Statistical Methods

EP09-A3 introduces various advanced statistical techniques for quantifying the relationship between measurement procedures:

Regression Analysis Techniques: The guideline describes several regression approaches, including:

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression: Traditional regression that assumes no error in the x-variable measurement

- Deming Regression: Accounts for measurement error in both methods compared

- Weighted Deming Regression: Extends Deming regression to address non-constant measurement variability across concentrations

- Passing-Bablok Regression: A non-parametric method that makes no distributional assumptions and is robust to outliers [6]

Bias Estimation with Confidence Intervals: The guideline mandates computation of bias estimates with confidence intervals at medically important decision levels rather than single-point estimates. This approach provides more clinically relevant information and acknowledges the uncertainty in bias estimates [6].

Outlier Detection: EP09-A3 recommends using the extreme studentized deviate method for objective identification of potential outliers that might unduly influence the statistical analysis [6].

The table below summarizes the key statistical methods described in EP09-A3 and their appropriate applications:

Table 1: Statistical Methods for Method Comparison Studies per EP09-A3

| Statistical Method | Type of Analysis | Key Assumptions | Appropriate Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deming Regression | Parametric regression | Constant ratio of measurement variances | Both methods have measurable error |

| Weighted Deming Regression | Parametric regression | Non-constant measurement variability | Precision varies across concentration range |

| Passing-Bablok Regression | Non-parametric regression | No distributional assumptions | Non-normal data, presence of outliers |

| Bland-Altman Difference Plots | Graphical agreement assessment | No specific distribution | Visualizing bias across measurement range |

| Bootstrap Iterative Technique | Resampling method | Representative sampling | Estimating confidence intervals for complex statistics |

Inappropriate Statistical Methods

EP09-A3 explicitly cautions against using inadequate statistical approaches that were commonly employed in earlier method comparison studies:

Correlation Analysis: Correlation coefficients (r) measure the strength of a relationship between methods but cannot detect constant or proportional bias. As demonstrated in examples, two methods can show perfect correlation (r=1.00) while having clinically unacceptable biases [1].

t-Tests: Both paired and independent t-tests are inadequate for method comparison. T-tests may fail to detect clinically significant differences with small sample sizes, or detect statistically significant but clinically irrelevant differences with large sample sizes [1].

Comparative Analysis: EP09-A3 vs. Previous Editions and Other Standards

Evolution from EP09-A2 to EP09-A3

The third edition of the EP09 guideline introduced substantial improvements over its predecessor:

Table 2: Key Differences Between EP09-A2 and EP09-A3

| Feature | EP09-A2 | EP09-A3 |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Applications | Limited coverage of comparison applications | Broader coverage including factor comparisons (e.g., sample tube types) |

| Data Visualization | Basic scatter plots | Enhanced emphasis on difference plots for visual bias inspection |

| Regression Methods | Basic Deming and Passing-Bablok | Weighted options, improved Deming, corrected Passing-Bablok descriptions |

| Bias Estimation | Single-point estimates | Bias at clinical decision points with confidence intervals |

| Outlier Detection | Limited guidance | Formalized extreme studentized deviate method |

| Statistical Complexity | Detailed mathematics in main text | Relocation of complex mathematical descriptions to appendices |

| Manufacturer Requirements | General bias characterization | Clear specification to use regression analysis for bias characterization |

These enhancements make EP09-A3 more applicable to diverse comparison scenarios, including those performed by clinical laboratories for sample type comparisons (e.g., serum vs. plasma) or reagent lot changes [6]. The addition of the bootstrap iterative technique for bias estimation provides a robust resampling method for determining confidence intervals when traditional parametric assumptions may not be met [6].

Relationship to Other CLSI Standards

EP09-A3 exists within a broader ecosystem of CLSI standards, each addressing specific aspects of method validation:

- EP05 and EP15: Focus on evaluation of random error and precision, whereas EP09-A3 specifically addresses systematic error (bias) [6]

- EP07: Provides guidance for measuring bias from individual sources such as sample interference, while EP09-A3 addresses overall method comparison [6]

- EP21: Concerns total error estimation, which combines both random and systematic error components [6]

- EP12: Covers qualitative test evaluation, while EP09-A3 is specifically for quantitative procedures [6]

Understanding this relationship helps laboratories implement a comprehensive validation strategy using complementary CLSI guidelines appropriate for their specific needs.

Implementation in Regulatory and Laboratory Environments

Case Studies and Practical Applications

Real-world implementations demonstrate the practical utility of EP09-A3 across diverse laboratory scenarios:

Immunoassay System Comparison: A 2021 study published in the International Journal of General Medicine applied the EP09-A2 protocol (a direct predecessor to EP09-A3) to compare HCG measurements between a Beckman Dxl 800 immunoassay analyzer and a Jet-iStar 3000 immunoassay analyzer. The study used 40 fresh serum specimens with 20 having abnormal HCG concentrations, analyzed over five consecutive days. Through regression analysis, researchers established a strong correlation (r=0.998) with the regression equation y=1.020x+12.96, determining that the estimated bias was within clinically acceptable limits [7].

Thyroid Hormone Testing Evaluation: A 2023 method comparison study of total triiodothyronine (TT3) and total thyroxine (TT4) measurements between Roche Cobas e602 and Sysmex HISCL 5000 analyzers successfully implemented EP09-A3 guidelines. The study demonstrated excellent analytical performance with acceptable biases for both systems, highlighting the guideline's suitability for evaluating method comparability across different technological platforms [8].

Software Tools Supporting EP09-A3 Implementation

Specialized statistical software packages have incorporated EP09-A3 protocols to streamline implementation:

Table 3: Software Solutions Supporting EP09-A3 Compliance

| Software Platform | EP09-A3 Features | Target Users | Regulatory Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP Evaluator 12.0+ | Advanced statistical module with multiple replicate handling, advanced regression algorithms | Clinical laboratories, IVD manufacturers | FDA 510(k) submissions, routine quality assurance |

| Analyse-it Method Validation Edition | Comprehensive CLSI protocol support including weighted Deming and Passing-Bablok regression | ISO 15189 medical laboratories, IVD developers | FDA submissions, ISO/IEC 17025 compliance, CLIA '88 compliance |

These software solutions help standardize the implementation of EP09-A3 statistical methods, reduce calculation errors, and generate publication-quality outputs suitable for regulatory submissions [9] [10].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following toolkit represents essential materials required for conducting EP09-A3-compliant method comparison studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Comparison Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in EP09-A3 Studies | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Samples | Primary material for method comparison | Cover clinical measurement range, include abnormal values, ensure stability |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring assay performance during study | Commutable, concentration near medical decision points |

| Calibrators | Ensuring proper instrument calibration | Traceable to reference standards, commutable with patient samples |

| Reagents | Test-specific reaction components | Lot-to-lot consistency, manufacturer-specified storage conditions |

| Statistical Software | Data analysis and regression calculations | CLSI EP09-A3 compliant algorithms, appropriate validation |

The CLSI EP09-A3 guideline represents the current standard for method comparison studies, providing a robust statistical framework for bias estimation between quantitative measurement procedures. Its comprehensive approach—encompassing experimental design, visual data exploration, advanced regression techniques, and clinical interpretation of bias—makes it indispensable for laboratories and manufacturers seeking to ensure result comparability across methods and platforms. The guideline's recognition by regulatory bodies like the FDA further underscores its importance in the method validation process [6].

As laboratory medicine continues to evolve with new technologies and platforms, the principles established in EP09-A3 provide a consistent methodology for evaluating method performance and ensuring that patient results remain comparable regardless of the testing platform used. Proper implementation of this guideline helps maintain data integrity across clinical and research settings, ultimately supporting accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions.

In laboratory medicine, defining the required quality of a test is fundamental to ensuring its clinical usefulness. Analytical Performance Specifications (APS) are "Criteria that specify the quality required for analytical performance to deliver laboratory test information that would satisfy clinical needs for improving health outcomes" [11]. The Milan Hierarchy Model, established during the 2014 consensus conference, provides a structured framework for setting these specifications, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to a more nuanced, evidence-based methodology [11] [12]. This model is critical for researchers and drug development professionals conducting method comparison studies, as it supplies the rigorous acceptance criteria against which new or existing analytical methods must be validated.

The Core Models of the Milan Hierarchy

The Milan consensus formalized three distinct models for establishing APS, each with its own rationale and application [11].

Model 1: Clinical Outcome: This model is considered the gold standard, as it bases APS directly on the test's impact on patient health outcomes. It can be applied through direct evaluation of how different assay performances affect health outcomes or, more feasibly, through indirect evaluation using modeling or surveys of clinical decision-making [11].

Model 2: Biological Variation: This model sets specifications based on the innate biological variation of an analyte within and between individuals. For diagnostics, the goal is often defined as

SDa < 0.5 SDbiol, whereSDbiolis the total biological standard deviation. For monitoring, the more stringent specification of(SDa² + Bias²)â°Â·âµ < 0.5 SDIis used, whereSDIis the within-subject biological variation [12]. The European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) maintains a database of rigorously determined biological variation data for this purpose [11].Model 3: State of the Art: When outcome-based or biological variation data are unavailable, APS can be based on the best performance currently achievable by available technology. This can serve as a benchmark for improvement or a minimum standard that most laboratories can meet [11].

A Risk-Based Synthesis of the Models

A contemporary development in applying the Milan Hierarchy is the argument against rigidly assigning a measurand to a single model. Instead, a risk-based approach is recommended, which considers the purpose of the test in the clinical pathway, its impact on medical decisions, and available information from all three models before determining the most appropriate APS for a specific setting [11]. The final choice of model is influenced by the quality of the underlying evidence and the specific clinical application of the test.

Table 1: The Core Models of the Milan Hierarchy for Setting APS

| Model | Basis for Specification | Primary Application | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Clinical Outcome | Direct or indirect link to patient health outcomes [11] | Tests with a central role in clinical decisions and defined decision levels (e.g., HbA1c, cholesterol) [12] | The most clinically relevant approach; considered the ideal | Extremely difficult and resource-intensive to perform direct outcome studies [11] |

| Model 2: Biological Variation | Within- and between-subject biological variation of the analyte [11] [12] | Measurands under homeostatic control; widely applied for many routine tests | Provides a universally applicable, objective goal that is independent of current technology | May yield unrealistically tight goals for some tightly controlled measurands (e.g., electrolytes) [12] |

| Model 3: State of the Art | Current performance achieved by the best available or most commonly used methods [11] | Measurands where Models 1 and 2 cannot be applied (e.g., many urine tests) [12] | Pragmatic and achievable; useful for driving incremental improvement | Risks perpetuating inadequate performance if the "state of the art" is poor |

Experimental Protocols for Applying the Milan Models

Protocol for Establishing APS Based on Biological Variation (Model 2)

The application of Model 2 has been significantly refined through initiatives like the European Biological Variation Study (EuBIVAS) [11].

- Objective: To determine the desirable imprecision (CVa) and bias (Biasa) for an analytical method based on biological variation data.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Literature Search & Critical Appraisal: Systematically search for biological variation studies for the target measurand. All identified studies must be critically appraised using the Biological Variation Critical Appraisal Checklist (BIVAC) to grade their quality [11].

- Data Extraction: Obtain the estimated within-subject (CVI) and between-subject (CVG) biological variation coefficients from the highest-quality available study.

- Calculation of APS: Apply consensus formulas to derive performance specifications. The EFLM recommends several tiers of quality:

- Optimum:

CVa ≤ 0.25 CVIandBiasa ≤ 0.125 (CVI² + CVG²)â°Â·âµ - Desirable:

CVa ≤ 0.50 CVIandBiasa ≤ 0.25 (CVI² + CVG²)â°Â·âµ - Minimum:

CVa ≤ 0.75 CVIandBiasa ≤ 0.375 (CVI² + CVG²)â°Â·âµ

- Optimum:

- Data Analysis: The calculated CVa and Biasa are used as the acceptance criteria when validating a new method. The method's own imprecision and bias, determined through replication and comparison-of-methods experiments, must be equal to or less than these desirable specifications.

Protocol for Establishing APS Based on State of the Art (Model 3)

- Objective: To define APS based on the current performance achievable by available technology.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Data Collection: Gather large-scale performance data from External Quality Assessment (EQA) programs or method comparison peer-group analyses [11].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the distribution of performance (e.g., imprecision and bias) across a large number of laboratories or methods.

- Specification Setting: Choose a percentile of performance as the benchmark. This can be an aspirational goal (e.g., the performance level of the top 10% of methods) to drive improvement, or a minimum standard (e.g., the performance level achieved by 80% of laboratories) to identify and rectify poor performance [11].

Visualization of the Milan Model Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and applying the Milan models, incorporating the modern risk-based approach.

For researchers implementing the Milan models, specific tools and resources are essential.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for APS Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function in APS Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| BIVAC Checklist | A critical appraisal tool to grade the quality and reliability of published biological variation studies [11]. | European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) |

| Biological Variation Database | A publicly available database compiling quality-appraised biological variation data for numerous measurands [11]. | EFLM Biological Variation Database (biologicalvariation.eu) |

| Commutable EQA Materials | External quality control materials that behave like fresh human patient samples, essential for accurately assessing inter-laboratory bias and determining the "state of the art" [11]. | Various commercial and national EQA providers |

| Statistical Software for MU & TE | Software capable of complex calculations for measurement uncertainty and total error, integrating imprecision and bias data. | R, Python, SAS, or specialized validation software packages |

| Stable Sample Pools | For estimating a method's long-term imprecision (CVa) through repeated measurement over time, a key input for Models 2 and 3. | In-house prepared pools of human serum or other relevant matrices |

Comparative Analysis of Model Outcomes and Data Presentation

The choice of model directly influences the stringency of the performance specification, which can lead to different conclusions in a method comparison acceptance study.

Table 3: Comparison of Exemplary APS for Common Analytes from Different Models

| Measurand | Clinical Context | Model 1 (Outcome) | Model 2 (Biol. Var.) - Desirable | Model 3 (State of the Art) | Implied Decision in Method Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | Diagnosis of diabetes | Total Error < 5.0% (based on clinical guidelines) [11] | Total Error < 2.9% (based on CVI) | CV < 2.5% (based on EQA data) | A new method meeting Model 3 may fail the more stringent Model 1 and 2 criteria. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Monitoring inflammation | Not commonly established | CV < 14.6% (based on CVI) | CV < 10.0% (aspirational, based on best methods) [11] | Model 3 may drive adoption of superior methods, even if Model 2 is met. |

| Cortisol | Diagnosis (vs. Monitoring) | Requires very low bias for diagnosis [11] | Bias < 5.0% | Bias < 10.0% | A method suitable for monitoring (meeting Model 3) may be inadequate for diagnostic use (Model 1). |

The Milan Hierarchy Model provides a vital, structured framework for setting defensible analytical performance specifications. For the method comparison researcher, its power lies in moving from arbitrary quality goals to a justified, evidence-based selection process. The evolving best practice is not to slavishly adhere to a single model but to undertake a comprehensive, risk-based synthesis of available clinical outcome, biological variation, and state-of-the-art data. This ensures that the final APS is not only statistically sound but also clinically relevant, ultimately guaranteeing that laboratory results are fit-for-purpose in the context of patient care and drug development.

In method comparison studies, a critical yet often misunderstood area of statistical analysis, the misuse of correlation analysis and the t-test remains prevalent. This guide objectively compares these inadequate methods with robust alternatives like Bland-Altman difference plots and regression analyses, providing supporting experimental data and protocols. Framed within the broader context of statistical analysis for method comparison acceptance research, this article equips scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge to validate analytical techniques accurately and reliably.

The Fundamental Flaw: Using Association to Assess Agreement

A common misconception in method comparison studies is that a strong correlation between two measurement techniques indicates they can be used interchangeably. This is a fundamental error, as correlation measures the strength of a relationship, not the extent of agreement [1].

Experimental Evidence: The Correlation Fallacy

The following experiment demonstrates that a perfect correlation can exist alongside a massive, clinically unacceptable bias.

TABLE I: Glucose measurements demonstrating the correlation fallacy [1]

| Sample Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose by Method 1 (mmol/L) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Glucose by Method 2 (mmol/L) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 |

Experimental Protocol: Glucose was measured in 10 patient samples using two different methods. Method 1 is the established reference, while Method 2 is a new technique under evaluation. The correlation coefficient (r) for the two datasets is calculated.

Resulting Data: The correlation coefficient for this dataset is 1.00 (P < 0.001), indicating a perfect linear relationship [1]. However, visual inspection and basic calculation reveal that Method 2 consistently yields values five times higher than Method 1. This proportional bias means the methods are not interchangeable, a fact entirely missed by the correlation analysis.

The Inadequacy of the T-Test for Method Comparison

The t-test is designed to detect differences between the mean values of two groups. However, in method comparison, agreement requires that measurements are close for each individual sample, not just that the group averages are similar [1].

Experimental Evidence: The T-Test's Blind Spot

This experiment shows how a t-test can fail to detect clear patterns of disagreement between two methods.

TABLE II: Glucose measurements demonstrating the t-test's inadequacy [1]

| Sample Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 (mmol/L) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Method 2 (mmol/L) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Experimental Protocol: Five patient samples are measured with two methods. An independent samples t-test is used to compare the results from Method 1 and Method 2.

Resulting Data: The mean for both Method 1 and Method 2 is 3.0 mmol/L. The independent t-test shows no significant difference (P < 0.001), suggesting comparability [1]. In reality, the methods are inversely related and would produce entirely different clinical interpretations for individual patients. The t-test failed because it only compared the central tendency, ignoring the paired nature of the data and the direction of differences for each sample.

The Sample Size Paradox of the Paired T-Test

The paired t-test, while an improvement, is still inadequate. Its ability to detect a difference is heavily influenced by sample size [1].

- With a large sample, it may detect a statistically significant but clinically meaningless bias.

- With a small sample, it may fail to detect a large and clinically important bias, as shown in the data below.

TABLE III: Example of a clinically significant bias missed by a paired t-test due to small sample size [1]

| Sample Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 (mmol/L) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| Method 2 (mmol/L) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

Resulting Data: The mean difference is -10.8%, which is clinically significant. However, with only five samples, the paired t-test reports a P-value of 0.208, which is not statistically significant [1]. This demonstrates how reliance on the t-test can lead to the acceptance of a poorly performing method.

Robust Alternatives for Method Comparison

The CLSI EP09-A3 standard provides guidance on proper statistical procedures for method comparison studies, emphasizing graphical presentation and specific regression techniques [1].

The Bland-Altman Difference Plot

The Bland-Altman plot (or difference plot) is the recommended graphical method to assess agreement between two measurement techniques [1].

Diagram 1: Workflow for creating and interpreting a Bland-Altman plot.

Interpretation: The plot visually reveals any systematic bias (the mean difference) and the random variation around that bias (95% limits of agreement). The key question is whether the observed bias and variation are small enough to be clinically acceptable, a decision that requires expert judgment, not just a statistical test [1].

Advanced Regression Techniques

For a more detailed analysis of the relationship between methods, advanced regression techniques are preferred over simple correlation.

- Deming Regression: Accounts for measurement error in both methods.

- Passing-Bablok Regression: A non-parametric method that is robust to outliers and does not require normally distributed data.

These methods provide reliable estimates of constant and proportional bias, which are critical for determining if two methods are interchangeable [1].

The Scientist's Statistical Toolkit

TABLE IV: Essential reagents and materials for a robust method comparison study

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| At Least 40 Patient Samples | To ensure sufficient statistical power and to identify unexpected errors due to interferences or sample matrix effects [1]. |

| Samples Covering Clinically Meaningful Range | To evaluate method performance across all potential values encountered in practice, from low to high [1]. |

| Duplicate Measurements | To minimize the effect of random variation and improve the reliability of the comparison [1]. |

| Pre-Defined Acceptable Bias | A performance specification (e.g., based on biological variation or clinical outcomes) established before the experiment to objectively judge the results [1]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, SPSS) | To perform specialized analyses like Deming or Passing-Bablok regression and generate Bland-Altman plots [13]. |

| A-205804 | A-205804, CAS:251992-66-2, MF:C15H12N2OS2, MW:300.4 g/mol |

| Aaptamine | Aaptamine, CAS:85547-22-4, MF:C13H12N2O2, MW:228.25 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol for a Compliant Method Comparison Study

A well-designed experiment is the foundation of a valid comparison.

Diagram 2: Step-by-step workflow for a robust method comparison study.

Key Protocol Steps:

- Pre-Analysis Planning: Define acceptable performance specifications a priori and secure a sufficient number of samples covering the entire clinical reportable range [1].

- Sample Analysis: Analyze samples within a narrow stability window (e.g., within 2 hours of collection) to prevent degradation. Randomize the sequence of analysis across both methods to avoid carry-over and time-related biases. Perform measurements over several days to ensure reproducibility [1].

- Data Analysis & Interpretation: Begin with graphical analyses (scatter and Bland-Altman plots) to visualize the data and detect outliers. Follow with robust regression analysis to quantify bias. Finally, compare the estimated bias to the pre-defined acceptable limit to make a decision on method interchangeability [1].

TABLE V: Summary of statistical methods for method comparison

| Method | Primary Function | Appropriate for Agreement? | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Analysis | Measures strength of a linear relationship | No | Fails to detect constant or proportional bias; perfect correlation can exist with total disagreement [1]. |

| T-Test (Independent) | Compares means of two independent groups | No | Only compares central tendency; ignores paired structure of data and individual differences [1]. |

| T-Test (Paired) | Compares means of two paired measurements | No | Highly sensitive to sample size; can miss large biases with small N or find trivial biases with large N [1]. |

| Bland-Altman Plot | Visualizes agreement and estimates bias | Yes | Provides direct visual and quantitative assessment of bias and its clinical acceptability [1]. |

| Deming/Passing-Bablok Regression | Quantifies constant and proportional bias | Yes | Accounts for errors in both methods; provides robust estimates of the relationship between methods [1]. |

In the rigorous field of analytical science, particularly during drug development and method validation, confirming that a new measurement procedure can adequately replace an established one is a common necessity. This process, known as a method-comparison study, seeks to answer a direct clinical question: can we measure an analyte using either Method A or Method B and obtain equivalent results without affecting patient outcomes? [1] [14] The foundational principles that underpin this assessment are the concepts of bias, precision, and agreement. These terms, often mistakenly used interchangeably with "accuracy" and "association," have specific statistical meanings. A clear understanding of their distinctions is critical for designing robust experiments, performing correct data analysis, and drawing valid conclusions about the interchangeability of two measurement methods [1] [14]. Misapplication of statistical tests, such as relying solely on correlation analysis or t-tests, is a common pitfall that can lead to incorrect interpretations and the adoption of flawed methods [1].

Defining the Core Concepts

Accuracy, Trueness, and Precision

According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the terminology surrounding measurement error is precisely defined [15]:

- Trueness refers to the closeness of agreement between the average of a large number of test results and a true or accepted reference value. It is a measure of systematic error [15].

- Precision is the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions. It is a measure of random error and is often described in terms of repeatability (same instrument, operator, short time period) and reproducibility (different instruments, operators, longer time periods) [15].

- Accuracy is a more general term that, in its ISO definition, encompasses both trueness and precision. It describes the closeness of a measurement to the true value, accounting for both systematic and random errors [15].

The relationship between these concepts is illustrated in the following diagram.

Bias and Precision in Method-Comparison Studies

In the specific context of a method-comparison study, where a new method is tested against an established one, the terminology is often operationalized as follows [14]:

- Bias: This represents the systematic error or the mean difference between the new method and the established comparison method. It quantifies how much higher (positive bias) or lower (negative bias) the new method reads on average [14] [2]. It is the primary measure of inaccuracy in a comparison study.

- Precision: Here, precision typically refers to the repeatability of a method—the degree to which it produces the same result on repeated measurements of the same sample [14]. The standard deviation (SD) of the differences between paired measurements is a key measure of this variability.

Agreement vs. Association

A critical distinction must be made between agreement and association.

- Agreement answers the question: "Do the two methods produce the same value for the same sample?" It is concerned with the identity of the measurements and is assessed by examining the differences between paired results [1] [16].

- Association answers the question: "Is there a linear relationship between the measurements from the two methods?" It assesses whether one variable changes predictably with another, but not whether the values are identical [1].

A high correlation can exist even when there is a large, clinically unacceptable bias, as demonstrated in the example below where two methods for measuring glucose have a perfect correlation (r=1.00) but are not comparable due to a large proportional bias [1].

Table: Example Demonstrating Perfect Association but Poor Agreement

| Sample Number | Method 1 (mmol/L) | Method 2 (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 | 15 |

| 4 | 4 | 20 |

| 5 | 5 | 25 |

| 6 | 6 | 30 |

| 7 | 7 | 35 |

| 8 | 8 | 40 |

| 9 | 9 | 45 |

| 10 | 10 | 50 |

Source: Adapted from acutecaretesting.org [1]

Designing a Method-Comparison Experiment

A well-designed experiment is the cornerstone of a valid method comparison. Careful planning minimizes the impact of extraneous variables and ensures the results are reliable [1] [17].

Key Design Considerations

- Selection of Methods: The two methods must be intended to measure the same underlying quantity (measurand). Comparing a pulse oximeter (measuring oxygen saturation) with a transcutaneous oxygen sensor (measuring partial pressure) is not appropriate, even if the results are related [14].

- Sample Number and Selection: A minimum of 40 patient samples is recommended, with larger numbers (100-200) providing better ability to detect issues like sample-specific interferences [1] [17]. Samples must be carefully selected to cover the entire clinically meaningful measurement range, not just a narrow interval [1] [17] [14].

- Replication and Timing: Whenever feasible, duplicate measurements should be performed for at least one of the methods to minimize random variation and help identify outliers [1] [17]. Measurements by the two methods should be made as simultaneously as possible to ensure the underlying quantity has not changed [14].

- Time Period: The experiment should be conducted over multiple runs and a minimum of 5 days to capture typical day-to-day performance variations and mimic real-world conditions [1] [17].

- Specimen Stability: Samples should be analyzed within their stability window, ideally within 2 hours of each other, to ensure differences are not due to sample degradation [17].

Experimental Protocol for a Comparison Study

The following workflow outlines the key stages of a robust method-comparison experiment.

Analyzing and Interpreting Comparison Data

Graphical Analysis: The First and Essential Step

Before any statistical calculations, data must be visualized to identify patterns, outliers, and potential problems [1] [17].

- Scatter Plots: A scatter diagram plots the result from the new method (y-axis) against the result from the comparative method (x-axis). This provides a visual impression of the linearity of the relationship and the range of data. A visual line of identity (y=x) can be added to help judge agreement [1].

- Bland-Altman Difference Plots: This is the recommended graphical tool for assessing agreement [14]. The plot displays the average of the two measurements for each sample on the x-axis [(Method A + Method B)/2] and the difference between the two measurements (Method A - Method B) on the y-axis. This plot allows for direct visualization of the bias and its consistency across the measurement range [14].

Statistical Analysis: Quantifying Bias and Agreement

Statistical calculations provide numerical estimates of the errors observed graphically.

- Bias and Limits of Agreement: As proposed by Bland and Altman, the primary statistics for agreement are the bias (mean difference) and the limits of agreement (LOA), defined as Bias ± 1.96 × SD of the differences [14] [2]. The LOA estimate the interval within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are expected to lie. If the differences within these limits are not clinically important, the two methods can be considered interchangeable [14] [2].

- Linear Regression: For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression (e.g., Deming or Passing-Bablok) is useful. It models the relationship as Y = a + bX, where the intercept (a) indicates constant bias and the slope (b) indicates proportional bias. The systematic error at any critical medical decision concentration (Xc) can be calculated as SE = (a + bXc) - Xc [17].

Table: Summary of Key Analytical Techniques in Method Comparison

| Technique | Primary Purpose | Key Outputs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland-Altman Plot | Visual assessment of agreement across measurement range. | Mean difference (Bias), Limits of Agreement (Bias ± 1.96SD). | If the bias is small and the LOA are clinically acceptable, methods may be interchangeable. |

| Linear Regression | Model the relationship between methods and identify error types. | Y-intercept (constant bias), Slope (proportional bias), Standard Error of the Estimate (sy/x). | Intercept significantly different from 0 suggests constant bias; slope significantly different from 1 suggests proportional bias. |

| Correlation Analysis | Assess the strength of a linear relationship. | Correlation Coefficient (r), Coefficient of Determination (r²). | Not a measure of agreement. A high r can exist even with large, clinically unacceptable bias [1]. |

A Decision Framework for Method Interchangeability

The following diagram synthesizes the analytical steps into a logical framework for deciding whether two methods can be used interchangeably.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials required for conducting a high-quality method-comparison study in an analytical laboratory.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method-Comparison Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Samples | A minimum of 40-100 unique samples, carefully selected to cover the entire clinically reportable range. These are the core "reagents" for testing real-world performance and specificity [1] [17]. |

| Commercial Quality Control (QC) Materials | Used to verify that both the new and comparative methods are operating within predefined performance specifications for precision and trueness before and during the analysis of patient samples. |

| Reference Standard / Calibrator | A material with a known assigned value, traceable to a higher-order reference method. It is used to calibrate the comparative method (if it is a reference method) and ensure the accuracy base of the measurement scale [17]. |

| Statistical Software Package | Software capable of performing specialized analyses such as Bland-Altman plots, Deming regression, and Passing-Bablok regression is essential for correct data interpretation [14]. |

| Stable Sample Collection Tubes | Appropriate collection containers with necessary preservatives or anticoagulants to ensure specimen integrity and stability throughout the testing period, which may extend over several hours [17]. |

| AG1557 | AG1557, CAS:189290-58-2, MF:C16H14IN3O2, MW:407.21 g/mol |

| AGK2 | AGK2, CAS:304896-28-4, MF:C23H13Cl2N3O2, MW:434.3 g/mol |

Navigating the essential terminology of bias, precision, and agreement is fundamental to conducting valid method-comparison studies. Remember that association, measured by correlation, is not agreement. A successful comparison relies on a robust experimental design that incorporates a sufficient number of samples across a wide range, analyzed in duplicate over multiple days. The data must first be visually inspected using scatter and Bland-Altman difference plots, followed by quantitative analysis to estimate bias and its 95% limits of agreement. Only when both the average bias and the spread of differences (the limits of agreement) fall within pre-defined, clinically acceptable limits can two methods be considered truly interchangeable for use in research and patient care.

From Theory to Practice: Designing and Executing Your Comparison Study

In method comparison and acceptance research, the integrity of scientific conclusions is fundamentally dependent on a meticulously planned study design. The determination of sample size, measurement range, and data collection timing forms the critical foundation for producing statistically sound and reproducible results. These elements directly influence a study's ability to detect clinically relevant differences between measurement methods while minimizing resource expenditure. Recent surveys of published research indicate that improper attention to these design elements remains a prevalent issue, undermining the reliability of scientific findings across various fields [18] [19]. This guide examines optimal design parameters for studies involving 40-100 specimens, contextualized within a broader thesis on statistical methodology for method comparison acceptance. We present objective comparisons of different methodological approaches supported by experimental data and provide detailed protocols for implementation.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Fundamental Principles of Sample Size Determination

Sample size planning represents a critical balance between statistical power, practical constraints, and ethical considerations. An underpowered study with insufficient samples risks failing to detect true methodological differences, while an excessively large sample wastes resources and may identify statistically significant but clinically irrelevant effects [20]. In method comparison studies, sample size determination requires explicit consideration of several statistical parameters: the acceptable margin of agreement between methods, the expected variability in measurements, and the desired confidence level for estimated parameters [19].

For studies within the 40-100 specimen range, researchers must consider both the precision of agreement limits and the assurance probability that observed agreement will fall within predefined clinical acceptability thresholds. Recent methodological advancements have enabled more exact sample size procedures that account for the distributional properties of agreement metrics, moving beyond traditional rules-of-thumb that often proved inadequate for specific research contexts [19].

The Role of Measurement Range and Timing

The measurement range included in a method comparison study must adequately represent the entire spectrum of values encountered in clinical practice. Restricting the range of measured values may lead to biased agreement estimates and limit the generalizability of study findings. The Preiss-Fisher procedure provides a visual tool for assessing whether study specimens adequately cover the clinically relevant measurement range [19].

The timing of measurements introduces additional methodological considerations, particularly regarding the management of autocorrelation, seasonality effects, and non-stationary data in longitudinal assessments. Proper accounting for these temporal factors is essential for obtaining unbiased estimates of method agreement [18]. For studies implementing repeated measurements, the timing between assessments must be sufficient to minimize carryover effects while maintaining clinical relevance.

Methodological Approaches

Statistical Methods for Sample Size Determination

Table 1: Statistical Methods for Sample Size Determination in Method Comparison Studies

| Method | Application Context | Key Assumptions | Sample Size Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bland-Altman with Confidence Intervals [19] | Method comparison with single measurements | Normally distributed differences between methods | Based on expected width of confidence interval for limits of agreement |

| Equivalence Testing for Agreement [19] | Studies with repeated measurements (k ≥ 2) | Known unacceptable within-subject variance (σ²U) | Derived from degrees of freedom calculation; depends on number of replicates |

| LOAM for Multiple Observers [19] | Inter-rater reliability with multiple observers | Additive two-way random effects model | Precision improved more by increasing observers than increasing subjects |

| Simulation-Based Approaches [21] [19] | Complex models with multiple variance components | Model parameters can be specified | Flexible approach for advanced statistical models |

Experimental Design Considerations

The selection of an appropriate experimental design depends on the specific research question, measurement constraints, and analytical requirements. Parallel designs where measurements are obtained simultaneously by different methods facilitate direct comparison but may not be feasible for all measurement modalities. Repeated measures designs allow for the estimation of within-subject variability but require careful consideration of time interval selection to minimize learning effects and biological variation [22].

For studies evaluating the impact of interventions or temporal trends, interrupted time series (ITS) designs provide a robust quasi-experimental framework. Proper implementation of ITS requires careful attention to autocorrelation, seasonality, and model specification to avoid biased effect estimates [18]. Recent surveys indicate that these methodological considerations are often overlooked in practice, highlighting the need for more rigorous design reporting.

Diagram 1: Method Comparison Study Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential phases in designing and implementing a method comparison study, highlighting critical decision points at each stage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Method Comparison Studies (40-60 Specimens)

This protocol is optimized for preliminary method comparison studies with moderate resource availability:

Sample Selection and Preparation: Select 40-60 specimens to adequately represent the entire clinical measurement range. Use the Preiss-Fisher procedure to visually confirm appropriate range coverage [19]. Ensure specimens are stable throughout the testing period to minimize degradation effects.

Measurement Procedure: Perform duplicate measurements with each method in randomized order to control for time-dependent effects. Maintain consistent environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) throughout testing. Blind operators to previous results and method identities to prevent measurement bias.

Data Collection: Record all measurements using structured electronic data capture forms. Include relevant covariates that may influence measurement variability (operator, batch, time of day). Implement quality control checks to identify transcription errors or measurement outliers.

Statistical Analysis: Apply Bland-Altman analysis with calculation of 95% limits of agreement. Compute confidence intervals for agreement limits using exact procedures rather than asymptotic approximations [19]. Assess normality of differences using graphical methods and formal statistical tests.

Protocol for Comprehensive Method Validation (80-100 Specimens)

This enhanced protocol provides greater precision for definitive method validation studies:

Sample Selection Strategy: Employ stratified sampling across the clinical range to ensure uniform representation. Include 80-100 specimens to improve precision of variance component estimates. Consider including known reference standards to assess accuracy.

Measurement Design: Implement a balanced design with repeated measurements (2-3 replicates per method) to enable estimation of within-subject variance components. Randomize measurement order across operators and instruments to minimize systematic bias.

Timing Considerations: Standardize time intervals between repeated measurements to control for biological variation. For stability assessments, incorporate planned intervals that reflect clinical usage patterns. Document environmental conditions at each measurement time point.

Advanced Statistical Analysis: Employ variance component analysis to partition total variability into within-subject, between-subject, and method-related components. For multiple observers, use the Limits of Agreement with the Mean (LOAM) approach to account for rater effects [19].

Comparative Analysis and Results

Sample Size Recommendations Across Study Types

Table 2: Recommended Sample Sizes for Different Study Designs

| Study Objective | Minimum Sample Size | Recommended Sample Size | Key Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary Method Comparison | 40 | 50-60 | Expected difference between methods, within-subject variability |

| Definitive Agreement Study | 60 | 80-100 | Clinical agreement margins, assurance probability |

| Inter-rater Reliability | 30 subjects, 3-5 raters | 40 subjects, 5-8 raters | Number of raters, variance components |

| Longitudinal Method Monitoring | 40 with repeated measures | 60-80 with repeated measures | Autocorrelation, seasonality effects |

Impact of Sample Size on Precision of Agreement Estimates

Empirical investigations demonstrate that sample sizes below 40 specimens often produce unacceptably wide confidence intervals for clinical agreement limits. Analysis of variance component stability indicates that 50 specimens with 3 repeated measurements generally provides sufficient precision for most method comparison applications [19]. Increasing sample size beyond 100 specimens yields diminishing returns for precision improvement, with greater gains achieved through optimized measurement design and increased replication.

Studies incorporating multiple observers demonstrate that precision improvement depends more on increasing the number of observers than increasing the number of subjects. This highlights the distinctive design considerations for inter-rater reliability studies compared to method comparison applications [19].

Diagram 2: Factors Influencing Sample Size Decisions. This diagram illustrates the relationship between sample size and key study quality metrics, highlighting the balance between precision and feasibility.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Method Comparison Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Reference Standards | Calibration and quality control | Verify measurement accuracy across methods; essential for traceability |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring measurement precision | Should span clinically relevant range; used to assess within- and between-run variability |

| Specimen Collection Supplies | Standardized sample acquisition | Consistency critical for minimizing pre-analytical variability |

| Data Management System | Structured data capture | Essential for maintaining data integrity and supporting statistical analysis |

| Statistical Software Packages | Data analysis and visualization | R, SAS, or Python with specialized packages for agreement statistics |

| Apiole | Apiole, CAS:523-80-8, MF:C12H14O4, MW:222.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arctigenin mustard | Arctigenin Mustard|CAS 26788-57-8|MCE | Arctigenin mustard is a biologically active compound for research use only (RUO). It is not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Specialized Methodological Tools

Advanced method comparison studies benefit from specialized analytical tools, including the mlpwr package in R for simulation-based power analysis of complex designs [21]. This package enables researchers to optimize multiple design parameters simultaneously, such as balancing the number of participants and measurement time points within resource constraints. For studies employing Bland-Altman analysis, specialized R scripts are available for exact sample size calculations and confidence interval estimation [19].

Discussion and Implementation Guidelines

Interpretation of Findings

The evidence presented supports the conclusion that sample sizes between 40-100 specimens represent an optimal range for most method comparison studies, providing sufficient statistical power while maintaining practical feasibility. Studies employing fewer than 40 specimens frequently demonstrate inadequate precision in agreement estimates, while those exceeding 100 specimens often represent inefficient resource allocation unless particularly small effect sizes or complex variance structures are anticipated.

The measurement range inclusion emerges as a critical factor frequently overlooked in methodological planning. Specimens must adequately represent the entire clinical spectrum to ensure agreement estimates remain valid across all potential applications. Restricting measurement range to a narrow interval represents a common methodological flaw that limits the utility of study findings.

Practical Recommendations for Implementation

Preliminary Studies: For initial method comparisons, target 50-60 specimens with duplicate measurements. This provides robust estimates of agreement while conserving resources for definitive validation if required.

Definitive Validation: Plan for 80-100 specimens with appropriate replication when establishing method agreement for regulatory submissions or clinical implementation decisions.

Range Considerations: Ensure specimens are distributed across the entire clinically relevant measurement range rather than clustered around specific values.

Timing Optimization: Standardize measurement intervals and account for potential temporal effects through appropriate statistical modeling.

Reporting Standards: Adhere to Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) to ensure transparent and complete reporting of methodological details and results [19].

By implementing these evidence-based recommendations, researchers can optimize their study designs to produce methodologically sound, efficient, and clinically relevant method comparison studies.

In method comparison and acceptance research, the integrity of experimental conclusions rests upon two foundational pillars of data collection: appropriate replication of measurements and rigorous randomization. These practices are crucial for controlling variability and ensuring that observed differences are attributable to the methods being compared rather than extraneous factors. Duplicate measurements provide a mechanism for quantifying and controlling random error inherent in any analytical system, while randomization serves as a powerful tool for minimizing bias and establishing causal inference in experimental designs. Within statistical analysis frameworks, these methodologies protect against both Type I errors (false positives) and Type II errors (false negatives) by ensuring that variability is properly accounted for and that comparison groups are functionally equivalent before treatment application [23] [24]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, implementing systematic approaches to replication and randomization is not merely advisory but essential for producing reliable, defensible, and actionable scientific evidence.

The Role and Implementation of Duplicate Measurements

Understanding Technical and Biological Replicates

In experimental science, not all replicates are equivalent. Understanding the distinction between technical and biological replicates is fundamental to appropriate study design:

- Technical replicates involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample using the same experimental procedure. They primarily serve to quantify the variability introduced by the measurement technique itself (e.g., running the same serum sample multiple times on an analyzer) [25].

- Biological replicates are measurements taken from distinct biological specimens (e.g., blood samples from different individual patients). They account for natural biological variability and form the bedrock of sound statistical inference about populations [25].

The strategic choice between these replicate types depends on the research question. Technical replicates control for methodological noise, while biological replicates ensure that findings are generalizable beyond a single sample.

Comparison of Measurement Approaches

The number of repeated measurements per sample represents a practical balance between statistical precision and resource efficiency. The table below summarizes the key considerations for single, duplicate, and triplicate measurements:

Table: Comparison of Technical Replication Strategies

| Replication Approach | Primary Use Case | Error Management Capability | Throughput & Resource Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Measurements | Qualitative analysis, high-throughput screening when group means are more important than individual values | No error detection or correction; relies on retesting criteria for outliers | Maximum throughput and resource efficiency |

| Duplicate Measurements | Quantitative analysis where balance between accuracy and efficiency is needed; recommended for most ELISA applications | Enables error detection through variability thresholds (e.g., %CV >15-20%) but requires retesting if threshold exceeded | Optimal balance; approximately 50% lower throughput than single measurements |

| Triplicate Measurements | Situations requiring high precision for individual sample quantification; when data precision is paramount | Allows both error detection and correction through outlier exclusion; provides most reliable mean estimate | Lowest throughput and efficiency; ~67% lower than single measurements |

As illustrated, duplicate measurements typically represent the "sweet spot" for most quantitative applications, enabling error detection while maintaining practical efficiency [25]. Single measurements are suitable only when the consequences of undetected measurement errors have been compensated by the assay design or when qualitative results are sufficient.

Experimental Protocol for Replication Experiments

A standardized replication experiment estimates the random error (imprecision) of an analytical method. The following protocol is adapted from clinical laboratory validation practices [26]:

Material Selection: Select at least two different control materials that represent medically relevant decision concentrations (e.g., low and high clinical thresholds).

Short-term Imprecision Estimation:

- Analyze 20 samples of each material within a single analytical run or within one day.

- Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) for each material.

- Acceptance criterion: Short-term imprecision (SD) should be ≤ 0.25 × total allowable error (TEa).

Long-term Imprecision Estimation:

- Analyze one sample of each material on 20 different days.

- Calculate the mean, SD, and CV for each material.

- Acceptance criterion: Total imprecision (SD) should be ≤ 0.33 × TEa.

This structured approach systematically characterizes both within-run/day and between-day components of variability, providing a comprehensive picture of method performance.

Diagram: Measurement Replication Strategy Selection

Randomization Principles and Applications

Conceptual Basis for Randomization

Randomization serves as the cornerstone of causal inference in experimental research. By randomly assigning experimental units to treatment or control conditions, researchers ensure that the error term in the average treatment effect (ATE) estimation is zero in expectation [24]. Formally, this can be expressed as:

$$ \bar{Y1} - \bar{Y0} = \bar{\beta1}+\sum{j=1}^J \gammaj(\bar{x}{1j}-\bar{x}_{0j}) $$

Where the second term represents the "error term" - the average difference between treatment and control groups unrelated to the treatment. Randomization ensures this error term equals zero in expectation, making the ATE estimate ex ante unbiased [24]. This process effectively balances both observed and unobserved covariates across treatment groups, creating comparable groups that differ primarily in their exposure to the experimental intervention.

Randomization Units in Experimental Design

The choice of randomization unit fundamentally affects the design, interpretation, and statistical power of an experiment. The following table compares common randomization units:

Table: Comparison of Randomization Units in Experimental Design

| Randomization Unit | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| User ID-Based | Assigns unique users to groups for test duration | Consistent user experience across sessions; ideal for long-term effects measurement | Requires user registration/login; potential privacy concerns; reduced sample size |

| Cookie-Based | Uses browser cookies to assign anonymous users | Privacy-friendly; no registration required; larger potential sample size | Inconsistent across devices/browsers; vulnerable to user deletion; short-term focus |

| Session-Based | Assigns variants per user session | Rapid sample size accumulation; suitable for single-session behaviors | Inconsistent user experience; cannot measure long-term effects |

| Cluster-Based | Randomizes groups rather than individuals | Minimizes contamination; practical when individual randomization impossible | Reduces effective sample size; requires more complex power calculations |

The optimal randomization unit depends on the research context, with the general principle being to select the unit that minimizes contamination between treatment and control conditions while maintaining practical feasibility [27] [24].

Randomization Methods and Implementation

Several methodological approaches to randomization exist, each with distinct advantages:

Simple Randomization: Comparable to a lottery with replacement, where each unit has equal probability of assignment to any group. This approach may result in imbalanced group sizes, particularly with small samples [24].

Permutation Randomization: Assignment without replacement ensures exactly equal group sizes when the final sample size is known in advance. This approach maximizes statistical power for a given sample size and is typically implemented using statistical software for replicability [24].