Strategic Experimental Design: A Practical Guide to Slashing Sample Preparation Time and Cost in Biomedical Research

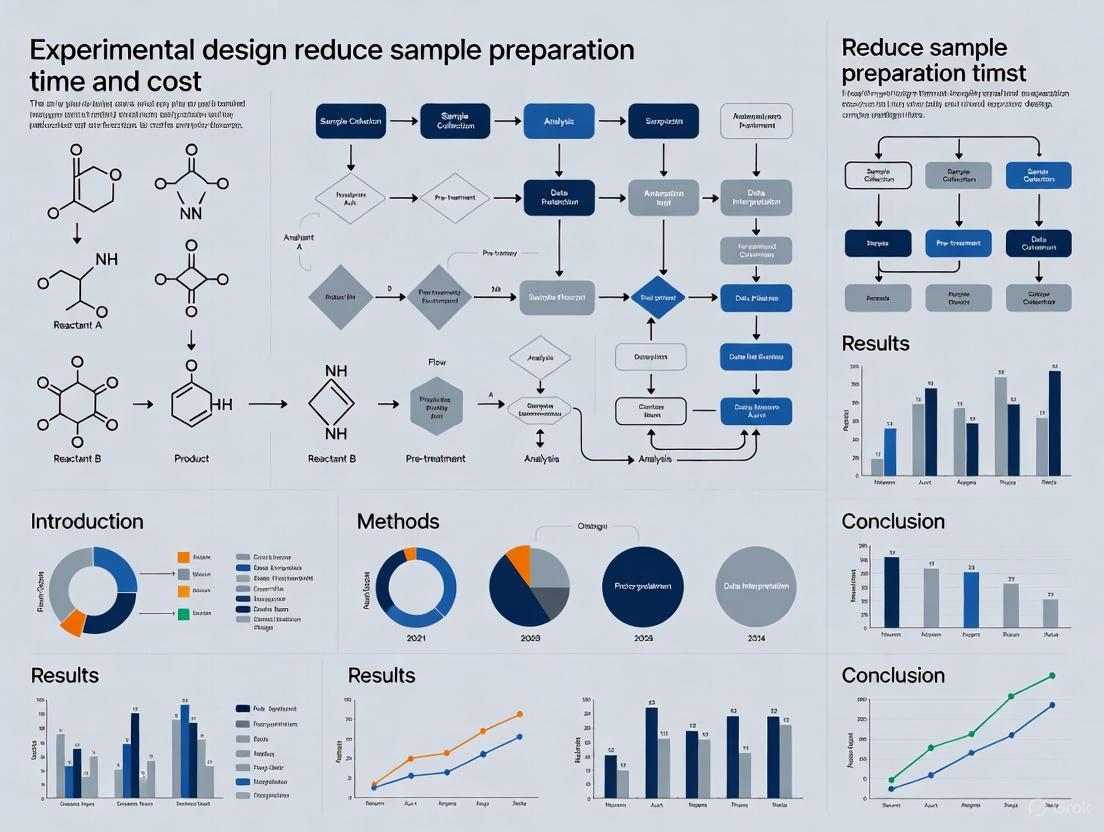

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging advanced experimental design (DOE) to dramatically reduce the time and financial burden of sample preparation.

Strategic Experimental Design: A Practical Guide to Slashing Sample Preparation Time and Cost in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging advanced experimental design (DOE) to dramatically reduce the time and financial burden of sample preparation. It explores the foundational principles of efficient design, presents real-world methodological applications from life science R&D, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common pitfalls, and validates the approach through comparative case studies and cost-benefit analysis. Readers will gain actionable insights to enhance throughput, conserve valuable reagents, and increase the robustness of their preparative workflows, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery while managing constrained budgets.

The High Cost of Inefficiency: Why Experimental Design is Your Most Powerful Tool for Cost Reduction

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Sample Preparation Challenges

| Common Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Analytical Recovery [1] | Analyte degradation; incomplete extraction; irreversible binding to solid phase; inefficient protein precipitation [1]. | Re-optimize extraction solvent, time, or temperature; use internal standards; change sorbent chemistry; confirm precipitation solvent efficacy and mixing/centrifugation steps [1]. |

| Inconsistent Results [1] | Variations in sample matrix; improper handling or storage; instrument miscalibration; operator technique [1]. | Implement Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs); use quality control checks; maintain and calibrate instruments; provide regular staff training [1]. |

| High Background Noise/Interference [1] [2] | Incomplete cleanup of complex sample matrix; co-eluting compounds; contamination [1] [2]. | Incorporate a wash step (e.g., in SPE); use selective sorbents or immunoaffinity columns; ensure proper sample filtration; use blanks to identify contamination source [1] [2]. |

| Sample Contamination [1] | Improper handling; unclean equipment; impure reagents or solvents [1]. | Wear appropriate PPE; establish rigorous cleaning protocols; use high-purity reagents; control the laboratory environment [1]. |

| Clogged Columns or Systems [1] | Incomplete removal of particulate matter; precipitation of analytes or matrix components [1]. | Perform sample filtration (e.g., membrane or glass fiber) or centrifugation prior to loading; ensure samples are fully dissolved and compatible with the mobile phase [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most impactful step to reduce sample preparation time and cost without compromising quality? Adopting modern, streamlined techniques like QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) can dramatically cut preparation time and solvent use, especially for analyzing pesticides in food or environmental samples. For liquid samples, Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) is highly efficient and can be automated, reducing manual labor and improving reproducibility [1].

Q2: How can we improve the reproducibility of manual protein precipitation? The key is strict adherence to a detailed protocol. This includes precise control over the sample-to-precipitation solvent ratio, ensuring consistent mixing or vortexing time, and standardizing centrifugation speed and duration. Using SOPs and regular technician training are crucial to minimize operator-based variation [1].

Q3: Our lab handles diverse sample types. How do we select the right sample preparation method? Selection should be based on:

- Sample State: Solid (e.g., tissue, soil) vs. Liquid (e.g., plasma, water) [1].

- Target Analytes: Small molecules vs. large proteins [2].

- Matrix Complexity: High (e.g., blood, food) vs. Low (e.g., buffer solutions).

- Required Sensitivity: Techniques like Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) or immunocapture can enrich trace analytes for highly sensitive detection [1] [2]. A pilot study comparing 2-3 candidate methods is often worthwhile to optimize for cost and time.

Q4: What are the emerging trends that can further reduce costs in sample preparation? The field is moving towards automation, miniaturization (using smaller sample volumes), and green chemistry (reducing hazardous solvent waste). Techniques like SALDI-TOF MS also integrate sample preparation and detection, streamlining the workflow [1] [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

This protocol provides a general methodology for extracting and purifying analytes from a liquid sample using SPE, which is a cornerstone technique for reducing interference and concentrating samples for analysis [1].

1. Objective To isolate, concentrate, and clean up target analytes from a complex liquid matrix (e.g., drugs from plasma, pollutants from water) using Solid-Phase Extraction.

2. Principle The sample is passed through a cartridge or plate containing a solid sorbent. Analytes are selectively retained on the sorbent based on chemical interactions (e.g., reversed-phase, ion-exchange). Interferences are washed away, and the purified analytes are then eluted with a strong solvent [1].

3. Materials and Equipment

- SPE cartridges or plates (e.g., C18 for reversed-phase)

- Vacuum manifold or positive pressure processor

- Collection tubes or plates

- Solvents: Conditioning solvent (e.g., methanol), Equilibration solvent (e.g., water or buffer), Wash solvent (e.g., water with 5% methanol), Elution solvent (e.g., pure methanol or acetonitrile)

- Sample tubes

- Pipettes and tips

4. Procedure

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Conditioning: Pass 1-2 column volumes of a strong solvent (e.g., methanol) through the sorbent bed to solvate it and remove any impurities. Do not allow the bed to run dry [1].

- Equilibration: Pass 1-2 column volumes of a weak solvent (e.g., water or a buffer matching the sample pH) to prepare the sorbent for sample retention [1].

- Sample Loading: Load the prepared sample (often pre-treated by filtration or centrifugation) onto the column. Use a slow, controlled flow rate to maximize analyte binding [1].

- Washing: Pass 1-2 column volumes of a weak wash solvent (e.g., 5% methanol in water) to remove weakly bound contaminants and matrix components without eluting the target analytes [1].

- Elution: Apply 1-2 column volumes of a strong elution solvent (e.g., pure organic solvent) to release the purified analytes into a clean collection tube. This fraction is now ready for analysis or concentration [1].

5. Key Considerations for Optimization

- Sorbent Selection: Match the sorbent chemistry (reversed-phase, normal-phase, ion-exchange) to the polarity and charge of your target analytes [1].

- pH Control: The pH of the sample and wash buffers can be critical for ionic compounds, as it affects whether the analyte is in a charged or neutral state, impacting retention [1].

- Solvent Strength: Carefully choose wash and elution solvents of appropriate strength to avoid losing analytes during the wash or failing to elute them completely [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Sample Preparation |

|---|---|

| C18 Sorbents [1] | A reversed-phase sorbent used in Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) to bind non-polar to moderately polar analytes from aqueous samples, facilitating cleanup and concentration. |

| QuEChERS Kits [1] | A ready-to-use kit for Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe extraction, primarily for pesticide residue analysis in food, integrating extraction and salt-based partitioning. |

| Protein Precipitation Plates [1] | Microplates designed for high-throughput protein removal from biological samples (e.g., plasma) using organic solvents, followed by vacuum filtration or centrifugation. |

| Immunoaffinity Columns [1] | Columns containing immobilized antibodies that specifically capture a target molecule (e.g., a specific protein or toxin) from a complex mixture, offering high selectivity. |

| SPME Fibers [1] | A solvent-free extraction tool where a coated fiber is exposed to the sample (headspace or liquid) to absorb volatiles or semi-volatiles for direct transfer to analytical instruments. |

| Oxythiamine Monophosphate | Oxythiamine Monophosphate|Research Chemical |

| Rivaroxaban metabolite M18 | Rivaroxaban Metabolite M18 |

Quantitative Data: Sample Preparation Technique Comparison

| Technique | Typical Sample Volume | Approx. Preparation Time | Relative Cost | Best For Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Precipitation [1] | 50-200 µL | 10-30 minutes | Low | Plasma, Serum |

| Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) [1] | 0.5-2 mL | 20-60 minutes | Medium | Plasma, Urine, Water |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) [1] | 1-100 mL | 30-90 minutes | Medium-High | Plasma, Urine, Water, Tissue Homogenates |

| QuEChERS [1] | 1-15 g | 15-45 minutes | Low-Medium | Fruits, Vegetables, Grains |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) [1] | 1-10 mL (headspace) | 5-60 minutes (incubation) | Low (per sample) | Volatiles from Blood, Urine, Food, Environmental |

Workflow Integration for Efficiency

The following diagram illustrates how the featured SPE protocol integrates into a complete analytical workflow, highlighting how robust sample preparation is the foundation for reliable and cost-effective data generation.

In the pursuit of scientific discovery, researchers often focus on advanced instrumentation and analytical techniques, overlooking a critical foundation: efficient experimental design for sample preparation. This step is not merely a preliminary chore; it represents a substantial, frequently underestimated portion of both time and financial resources in laboratory workflows. Adherence to traditional One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) methods and manual processes creates significant bottlenecks, inflating costs and delaying breakthroughs. This guide explores how modern experimental design and automation can dramatically reduce these burdens, enhancing both productivity and data quality.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary cost driver in analytical workflows, and why is it often overlooked? Sample preparation is the dominant cost driver, typically consuming over two-thirds of the total analysis time [3] [4]. It is frequently overlooked because the focus in research often falls on cutting-edge instrumentation and the analytical results themselves, while the foundational preparation step is considered routine.

2. How do OFAT (One-Factor-At-a-Time) methods increase hidden costs? OFAT experimentation is inefficient because it requires more experimental runs to gain limited information and fails to reveal interactions between factors [5]. This leads to higher costs in scientist time, equipment time, and consumables. It can also result in processes that are not robust, meaning they are sensitive to small, uncontrolled variations, potentially causing failures and requiring costly rework.

3. What is Design of Experiments (DOE) and how does it directly counter OFAT inefficiencies? DOE is a structured method for simultaneously testing multiple factors and their interactions to optimize a process [6]. It directly counters OFAT by providing a more complete understanding of the experimental space with far fewer runs. For example, one pharmaceutical company replaced a 672-run full factorial design with a 108-run D-optimal design, achieving the same conclusion with six times fewer wells [5].

4. My lab has a limited budget. Can automated sample preparation systems really provide a good return on investment? Yes. While there is an initial investment, the long-term savings in time and reagents, coupled with improved data quality, provide a strong return. For instance, the University of Cincinnati invested in a nitrogen evaporator, which reduced processing time for a batch of 10 samples from over 20 hours to just 1 hour—a 20x improvement in efficiency [3]. Such time savings directly translate into lower labor costs and higher throughput.

5. How does efficient sample preparation impact the overall quality and reliability of my data? Efficient, automated preparation minimizes manual handling, which reduces the risk of contamination, sample loss, and human error [3]. It also ensures uniform treatment of all samples, dramatically improving the consistency and reproducibility of your results [3] [4]. Furthermore, DOE helps build robust methods that are less sensitive to external variations, ensuring more reliable data [5].

Troubleshooting Common Inefficiencies

Problem 1: Prohibitively High Cost and Time Per Sample

Symptoms: Sample preparation costs rival or exceed instrumental analysis fees. Researchers spend most of their time on preparation rather than data interpretation.

- Root Cause: Reliance on manual, sequential processing methods (e.g., drying samples one vial at a time) and a high volume of experiments due to OFAT approaches.

- Solution:

- Adopt Automated Parallel Processing: Implement systems like multi-position nitrogen evaporators that can process entire sample batches simultaneously [3].

- Implement DOE for Factor Screening: Before optimization, use screening designs (e.g., fractional factorials) to identify the most influential factors. This prevents wasting resources on non-significant variables. One company screened 22 factors with a fractional factorial design in 320 runs; a full factorial would have required over 4.2 million runs [5].

Problem 2: Unacceptable Variability in Prepared Samples

Symptoms: High replicate variance, difficulty reproducing published methods, and inconsistent analytical results.

- Root Cause: Inconsistent manual techniques and a process that is sensitive to minor, uncontrolled variations.

- Solution:

- Automate Repetitive Tasks: Use automated liquid handlers and evaporators to ensure every sample is treated identically [7].

- Apply DOE for Robustness Testing: As part of a Quality by Design (QbD) framework, use DOE to test how your sample preparation method responds to small, deliberate changes in key factors (e.g., temperature, pH). This allows you to define a "design space" where the method is guaranteed to be robust. A company optimizing a transfection process used this approach to reduce variability by 81% [5].

Problem 3: Method Fails During Scale-Up or Transfer

Symptoms: A sample preparation method that works perfectly in development fails when used by another researcher or applied to a larger sample volume.

- Root Cause: The method was optimized using OFAT, which does not reveal factor interactions, making the process fragile and highly dependent on specific, uncontrolled conditions.

- Solution:

- Use DOE for Optimization: Replace OFAT with response surface methodologies (RSM) to find a true optimum where the method is less sensitive to variation [8]. This involves:

Quantitative Analysis of Costs and Savings

The following tables summarize the cost burden of traditional methods and the demonstrated savings from adopting more efficient designs and technologies.

| User Type | Sample Preparation Charge (per sample) | Analytical Instrumentation (per hour) |

|---|---|---|

| Internal User | $76 | $30 |

| External User | $118 | $47 |

Table 2: Documented Savings from Efficient Methods

| Strategy | Case Study | Outcome & Savings |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Evaporation | University of Cincinnati: Manual vs. Nitrogen Evaporator | Time for 10 samples reduced from 20 hours to 1 hour (20x efficiency gain) [3]. |

| DOE vs. Full Factorial | Top 20 Pharma Company: 672-run full factorial vs. 108-run D-optimal | Reached same conclusion with 6 times fewer runs [5]. |

| DOE for Reagent Reduction | Pharma Assay Development | Identified a condition that halved expensive reagent use while maintaining quality [5]. |

| DOE for Media Optimization | Uncommon (Lab-Grown Meat) | Campaign took weeks instead of months; reduced costs "by an order of magnitude" [5]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Response Surface Methodology for Sample Preparation Optimization

This sequential protocol is designed to efficiently find the optimal settings for a sample preparation method (e.g., a liquid-liquid extraction) [8].

- Define Objective and Response: Clearly state the goal (e.g., "maximize extraction recovery of analyte X") and identify the measurable response (e.g., peak area from LC-MS).

- Identify Key Factors: Select the critical factors to optimize (e.g., solvent volume, pH, mixing time) based on prior knowledge or a screening design.

- Code Factor Levels: Convert natural factor values to coded units (-1, 0, +1) to simplify analysis and make coefficients comparable [8].

- Phase 1: Steepest Ascent

- Run a first-order design (e.g., a 2² factorial with center points) in the initial region.

- Fit a first-order model: ( y = \beta0 + \beta1x1 + \beta2x_2 + \varepsilon )

- Use the coefficients to determine the path of steepest ascent and conduct experiments along this path until the response no longer improves [8].

- Phase 2: Composite Design

- Once near the optimum, run a second-order design (e.g., Central Composite Design) around the new best point.

- Fit a second-order model: ( y = \beta0 + \beta1x1 + \beta2x2 + \beta{12}x1x2 + \beta{11}x1^2 + \beta{22}x2^2 + \varepsilon )

- Analyze and Validate

- Use the fitted model to locate the optimum factor settings.

- Run confirmatory experiments at the predicted optimum to verify the results.

The workflow for this sequential optimization is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Oligonucleotide Bioanalysis via LC-MS/MS

This protocol is adapted from a published study that systematically optimized sample preparation for oligonucleotides in rat plasma [9].

Sample Preparation Technique Screening:

- Prepare rat plasma samples spiked with a 16 mer oligonucleotide standard.

- In parallel, evaluate four different sample cleanup procedures: Protein Precipitation (PPT), Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE), and a hybrid method (LLE combined with SPE).

- Finding: LLE with phenol:dichloromethane (2:1, v:v) was the most efficient, offering a balance of low cost and low toxicity [9].

Optimization of Drying Conditions:

- Following LLE, the extracted sample needs to be dried and reconstituted.

- Test different conditions for the drying (evaporation) step. Key factors include temperature and time.

- Optimal Condition: Ethanol precipitation at -80 °C for 5 minutes was determined to be the most effective drying condition [9].

MS Parameter Tuning:

- Tune the mass spectrometric parameters to optimal conditions for the specific oligonucleotide.

- Method: The study used a Central Composite Design (a type of Response Surface Design) to efficiently optimize the MS parameters [9].

Method Validation:

- Fully validate the final, optimized workflow. The cited assay achieved a quantitative range of 0.25-1000 nM, with excellent accuracy and precision [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Optimized Sample Preparation

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Evaporator | Gently concentrates or completely dries samples by heating under a stream of nitrogen gas, preventing analyte degradation. | Evaporating solvents like methanol, acetonitrile, or hexane prior to LC-MS analysis [3] [4]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses and transfers liquids, enabling high-throughput operations and eliminating manual pipetting errors. | Setting up large-scale DOE campaigns for assay development or media optimization [7]. |

| Phenol:Dichloromethane (2:1) | Efficient solvent for Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) to remove proteins and other impurities from biological samples. | Sample cleanup for oligonucleotide analysis from rat plasma [9]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | A statistical experimental design used to efficiently fit a second-order (quadratic) model for response surface optimization. | Optimizing mass spectrometric parameters or final stages of a sample prep method [9]. |

| D-Optimal Design | An algorithm-based experimental design that is ideal for constrained or irregular experimental spaces, minimizing the number of runs. | Reducing the number of experiments in assay development from hundreds to just over a hundred while retaining model quality [5]. |

| Ethylenebis(oxy)bis(sodium) | Ethylenebis(oxy)bis(sodium), MF:C2H4Na2O2, MW:106.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Lactacystin Allyl Ester | (+)-Lactacystin Allyl Ester, MF:C18H28N2O7S, MW:416.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between blocking and randomization? Blocking is a technique used when you are aware of a specific nuisance factor (like age, gender, or machine) that could influence your results. You proactively group experimental units into homogeneous blocks to systematically remove this source of variation [10]. Randomization, in contrast, is a defense against unknown or uncontrollable nuisance factors. By randomly assigning treatments, you ensure these unaccounted factors are likely balanced across all groups, preventing systematic bias [11].

My sample size is small. Which method is more critical? In small studies, blocking is often more powerful. Simple randomization in a small sample can accidentally lead to imbalanced groups (e.g., all healthier subjects in the treatment group). Blocking ensures that the groups are comparable on the key blocking variable, which increases the precision of your experiment and your ability to detect a true effect [11].

Can blocking and randomization be used together? Absolutely, and they often should be. A standard approach is to first divide your experimental units into blocks based on a known important characteristic (like "high severity" and "low severity" patients). Then, within each block, you randomly assign subjects to different treatment groups. This combines the variance-reduction power of blocking with the bias-prevention power of randomization [12].

How does this save time and money? By reducing unexplained variability, you increase the "signal-to-noise" ratio in your experiment. This means you can:

- Detect effects with a smaller sample size, reducing the cost of materials and data collection [13].

- Get reliable results faster because you are less likely to need to repeat experiments due to inconclusive or confounded results.

- Optimize processes more efficiently, as in pharmaceutical development, where Design of Experiments (DoE) leads to robust formulations and manufacturing processes, minimizing costly late-stage failures [14] [15].

What is a "nuisance factor" and how do I identify one? A nuisance factor is a variable that is not of primary interest in your study but is suspected to affect the response variable. Examples include different batches of raw material, different operators, different days, or patient characteristics like age [10]. You identify them based on prior knowledge, scientific literature, or preliminary data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High variability within treatment groups is masking the effect I am trying to measure.

- Potential Cause: Known sources of variation (e.g., skill level of technicians, different equipment) are not being controlled.

- Solution: Implement a Blocked Design.

- Identify the Nuisance Factor: Determine which known and controllable variable is likely causing the variability (e.g., "Furnace Run" in a semiconductor process) [16].

- Create Blocks: Group your experimental units into blocks where the nuisance factor is held constant. For example, all tests within a single furnace run form one block [10].

- Randomize Within Blocks: Randomly assign all treatments to the units within each block. For instance, in each furnace run, test all different material dosages in a random order [16].

- Analyze with ANOVA for RCBD: Use a statistical model that includes both the treatment effect and the block effect, which allows you to isolate and remove the variability due to the blocks from the experimental error [10].

Problem: My treatment groups seem systematically different even before the experiment begins.

- Potential Cause: Selection or allocation bias, where pre-existing differences between groups are confounded with the treatment effect.

- Solution: Implement Randomization.

- Choose a Randomization Scheme:

- Simple Randomization: Assign each unit to a group completely at random (e.g., using a random number generator). Best for large sample sizes [11].

- Block Randomization: If you need to ensure equal group sizes at any point during the experiment, randomize within small blocks (e.g., for every 4 subjects, randomly assign 2 to treatment and 2 to control) [11].

- Stratified Randomization: If you have a very important prognostic factor, first create strata (similar to blocks) and then randomize within each stratum to ensure balance on that factor [11].

- Conceal the Allocation: Use a method that prevents the experimenter from knowing the next assignment, which prevents conscious or subconscious bias [11].

- Choose a Randomization Scheme:

Problem: I have multiple known nuisance factors and a limited budget for experimental runs.

- Potential Cause: A simple blocked design may become too large and expensive if you try to block on too many variables.

- Solution: Use a Fractional Factorial Design for screening.

- Define Objective and Domain: Identify all input factors and the response you want to measure. For example, in developing pellets, factors may include binder percentage, granulation water, and spheronization speed [17].

- Select an Efficient Design: Choose a fractional factorial design (e.g., a 2^(5-2) design) that allows you to study multiple factors simultaneously in a reduced number of runs. This design is primarily used to identify which main effects are significant [17].

- Run and Analyze: Execute the experiments in a randomized order and perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The results will show you which factors have the largest impact on your response, allowing you to focus further optimization efforts on what truly matters [17].

Diagram 1: Decision flow for applying blocking and randomization.

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Table 1: Results from a Pharmaceutical Extrusion-Spheronization Screening Study This study used a fractional factorial design to screen five factors affecting pellet yield. The % Contribution (a measure of how much each factor explains the total variation in the data) helps identify critical factors for further optimization [17].

| Input Factor | Unit | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | % Contribution to Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binder (A) | % | 1.0 | 1.5 | 30.68% |

| Granulation Water (B) | % | 30 | 40 | 18.14% |

| Spheronization Speed (D) | RPM | 500 | 900 | 32.24% |

| Spheronizer Time (E) | min | 4 | 8 | 17.66% |

| Granulation Time (C) | min | 3 | 5 | 0.61% |

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Designs and Their Impact on Variance

| Design Type | Key Principle | Primary Benefit | Impact on Experimental Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completely Randomized Design (CRD) | Randomization alone [11] | Balances unknown lurking variables; ensures unbiased estimates [11] | Does not actively reduce error from known sources; error term includes all variability [10] |

| Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) | Blocking + Randomization within blocks [10] | Removes variability from a known, controllable nuisance factor [13] [16] | Partitions out and eliminates variability due to blocks, leading to a smaller, more precise estimate of error [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 3: Common Excipients in Tablet Formulation Development These inactive ingredients are critical components studied and optimized using DoE to achieve a robust drug product [14].

| Material | Category | Primary Function in Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Diluents | Excipient | Adds bulk to the tablet to make it a practical size for manufacturing and handling [14]. |

| Binders | Excipient | Promotes granulation and provides cohesion, ensuring the tablet remains intact after compression [14]. |

| Disintegrants | Excipient | Promotes the breakup of the tablet into smaller fragments upon contact with gastrointestinal fluid, enhancing drug dissolution [14]. |

| Lubricants | Excipient | Reduces friction during the tablet ejection process, preventing sticking to the machinery [14]. |

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | Active Component | The biologically active component of the drug product that produces the therapeutic effect [14]. |

| Desmopressin-d5 | Desmopressin-d5, MF:C46H64N14O12S2, MW:1074.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Enalaprilat N-Glucuronide | Enalaprilat N-Glucuronide Reference Standard | High-purity Enalaprilat N-Glucuronide for analytical research and ANDA. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

A flawed experimental design is the most expensive item in your budget.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is pseudoreplication and why is it a budget problem?

Pseudoreplication occurs when an analysis treats a dataset as if the sample size is larger than is appropriate, often because the individual measurements are not statistically independent [18]. This is a critical budget issue because it generates misleading, statistically significant results, creating false hope in a treatment or process. When this initial, flawed finding fails during later, more rigorous validation, you must repeat the entire costly experiment. One survey found that 58% of researchers had faced a research question where pseudoreplication was an unavoidable issue, highlighting its prevalence and the financial risk it poses [19].

2. How does a confounded variable lead to hidden costs?

A confounded variable is an unforeseen influence that is entangled with your experimental treatment, making it impossible to determine what truly caused the result [19]. For example, if all animals in a test group are housed in a single cage, any effect you see could be due to the treatment or the unique conditions of that cage. Confounding forces you to rerun experiments to disentangle these effects, directly consuming additional funds for reagents, animal models, and technician time.

3. I have limited resources and cannot replicate my experiment fully. What should I do?

While full replication is ideal, costly experiments like large-scale manipulations or long-term ecological studies sometimes face this challenge. In these cases, you must:

- Be Explicit: Clearly articulate the limitations and any potential confounding effects in your reports and publications [19].

- Use Statistical Solutions: Employ multilevel modeling or nested designs in your statistical analysis to account for non-independent data [19].

- Focus on Effect Sizes: Instead of relying solely on p-values, report the magnitude of the observed effects, which can provide valuable insights even when replication is limited [19].

4. What is the difference between a "sample" and an experimental "replicate," and why does it matter for my budget?

This is a fundamental distinction that protects your budget.

- An Experimental Replicate is an independent, randomized application of a treatment. It is the true unit of analysis for statistical inference.

- A Sample is a measurement within an experimental unit.

Treating multiple samples as if they were independent replicates is classic pseudoreplication. It artificially inflates your apparent sample size, leading to false positives and decisions based on inaccurate data, which are costly to correct later.

5. How can I check my experimental plan for these design flaws before spending any money?

Before starting your experiment, ask yourself these questions:

- For Pseudoreplication: "Is every data point I plan to analyze truly independent? Or are they grouped in a way (e.g., by time, location, or litter) that makes them correlated?"

- For Confounding: "Have I randomized treatments properly to ensure that no other systematic factor (like time of day, machine used, or technician) is perfectly aligned with my treatment groups?"

Consulting with a statistician or an experienced colleague during the design phase is one of the most cost-effective steps you can take.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Fixing Pseudoreplication

Pseudoreplication artificially inflates your sample size, leading to false positives and wasted resources. Follow this workflow to diagnose and fix it in your experimental design.

Detailed Fixes:

- Redesign Your Experiment: The most robust solution is to increase the number of independent experimental units. For instance, if testing a drug on 10 animals but measuring 100 cells from each, your true 'N' is 10 (animals), not 100 (cells). Budget for 20 animals across two groups, not for 2000 cell measurements from two animals.

- Employ Advanced Statistical Models: When a full redesign is not feasible, use statistical methods that account for non-independence.

- Nested Designs: Formally structure your data to reflect the hierarchy (e.g., cells nested within animals).

- Mixed Models: Use models with random effects (e.g.,

lmerin R) to correctly account for variance coming from different grouping levels (like cages or batches) [19]. This uses your data more efficiently and can prevent a total loss of investment.

Guide 2: Identifying and Controlling for Confounding Variables

A confounded variable can completely invalidate your results, forcing you to repeat work. This guide helps you identify and control for them.

Step 1: Identify Potential Confounders Before the experiment, brainstorm factors that could correlate with both your independent and dependent variables.

- Environmental: Time of day, room temperature, humidity, technician.

- Biological: Animal litter, cell passage number, batch of growth medium.

- Procedural: Order of processing, calibration of a specific instrument.

Step 2: Implement Control Mechanisms Integrate these controls directly into your experimental plan and budget.

Table 1: Strategies and Costs for Controlling Confounding Variables

| Strategy | Protocol Description | Impact on Budget & Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Randomly assigning experimental units to treatment or control groups to ensure confounders are distributed evenly. | Minimal direct cost. Requires planning time. Protects against unknown confounders. |

| Blocking | Grouping experimental units by a known confounder (e.g., litter, batch) and then randomizing treatments within each block. | Slightly increases complexity and required sample size. Highly cost-effective for known variables. |

| Balancing | Ensuring equal numbers of subjects or samples are assigned to each group. Often used with subject characteristics like sex or age. | Minimal cost. Easily integrated into design phase. Prevents group imbalance. |

| Statistical Control | Measuring the confounder and including it as a covariate in the final statistical analysis (e.g., ANCOVA). | Cost of measuring the covariate. Saves on having to re-do the experiment. |

Step 3: Validate Your Design Create a diagram of your experimental plan. If you can draw a direct arrow from a confounding variable to both your treatment assignment and your outcome, your design is at risk and needs the controls listed above.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Impact of Poor Design

The financial and temporal costs of poor design are quantifiable. The following table summarizes data from ecological and biomedical research on the prevalence and impact of these issues.

Table 2: Documented Impacts of Pseudoreplication and Confounding in Research

| Metric | Field / Context | Reported Statistic | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of Pseudoreplication | Ecological Experiments (1984) | 48% of published papers | [20] |

| Prevalence of Pseudoreplication | Primate Communication Studies | 39% of studies (88% avoidable) | [19] |

| Prevalence of Pseudoreplication | Logging & Biodiversity | 68% of studies | [19] |

| Unavoidable Pseudoreplication | Survey of Ecologists | 58% of researchers encountered it | [19] |

| False Inference Rate | Pseudoreplicated Logging Studies | 0% to 69% (depending on taxa) | [19] |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | Phase I (Safety) | ~52% | [21] |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | Phase II (Efficacy) | ~28.9% | [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust Experimental Design

| Item / Concept | Function in Experimental Design | Budget Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | To implement mixed models and nested analyses that correctly handle non-independent data. | Free, open-source options available. Investment in training is highly cost-effective. |

| Random Number Generator | To ensure truly random assignment of subjects/treatments, preventing selection bias. | Built into most software; no cost. Critical for valid results. |

| Blocking Factor | A known source of variability (e.g., assay batch, day) that is controlled for in the design. | Planning for blocking may slightly increase logistical complexity but saves cost on repeats. |

| Pilot Study | A small-scale preliminary experiment to identify unforeseen confounders and optimize protocols. | A small, upfront investment that can prevent massive, full-scale experiment failures. |

| Consulting Statistician | An expert to review your experimental design before you begin wet-lab work. | Hourly rate. Potentially the highest return-on-investment for avoiding costly design flaws. |

| Betamethasone 21-Acetate-d3 | Betamethasone 21-Acetate-d3, MF:C24H31FO6, MW:437.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Furagin-13C3 | Furagin-13C3, MF:C10H8N4O5, MW:267.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Workflow for a Cost-Conscious Design

Integrate the following workflow into your planning process to safeguard your budget.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can my team justify the use of animal subjects in our proposed study? Animal research is considered justifiable when there is genuine uncertainty about the relative merits of the interventions being compared (a state known as equipoise), when the potential human benefits are significant and cannot be obtained by other methods, and when all principles of the "3Rs" (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) are rigorously applied to minimize harm [22] [23] [24]. This must be reviewed and approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

FAQ 2: What are the core ethical principles we must adhere to for human trials? The core ethical principles are respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, as outlined in the Belmont Report [23]. In practice, this translates to:

- Voluntary Participation: Participants must be free to choose to participate and withdraw at any time without penalty [25].

- Informed Consent: Participants must receive and understand all relevant information about the study's purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits before agreeing to participate [25] [26].

- Minimization of Harm: All possible sources of physical, psychological, social, or legal harm must be identified and mitigated [25].

- Confidentiality: Participants' identifiable information must be protected from unauthorized access or disclosure [25].

FAQ 3: Our resources are limited. What is the most cost-effective experimental design improvement? Implementing blocking is a highly effective strategy. Blocking groups similar experimental units together, which reduces variability and makes it easier to detect genuine treatment effects. This leads to more precise results without requiring a larger sample size, saving both time and money [27]. Furthermore, a careful power analysis to determine the optimal sample size prevents the massive costs of both under-powered (too few subjects, leading to inconclusive results) and over-powered (unnecessarily large sample sizes, wasting resources) studies [28] [29].

FAQ 4: What are the consequences of poor experimental design? Poor design can lead to confounded results, false conclusions, and substantial resource waste. Specifically, it can cause:

- Confounding: When the effect of your variable of interest is mixed up with other variables, making your results uninterpretable [27].

- Pseudo-replication: Treating non-independent data points as independent, which inflates statistical significance and leads to invalid, misleading conclusions [27].

- Increased Risk of Bias: Without proper randomization and blinding, conscious or unconscious biases can skew the results, compromising their credibility [29] [27].

FAQ 5: How can we reduce the number of animal subjects without compromising data quality? The principle of Reduction from the "3Rs" framework directly addresses this. Key methods include:

- Consulting a Statistician: To use the minimum number of animals required to achieve statistical significance [24].

- Improving Experimental Techniques and Data Analysis: Using more precise measurements or more sensitive analytical techniques can provide robust data from fewer subjects [24].

- Sharing Information: Ensuring experiments are not duplicated by performing thorough literature searches and data sharing with other researchers [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Variability in Results and Inefficient Resource Use

Problem: Data has high noise-to-signal ratio, making it difficult to detect true treatment effects. This often leads to repeating experiments, wasting time, reagents, and animal/human subjects.

Solution: Employ design techniques that control for nuisance variables.

- 1. Implement Blocking: Group subjects based on known sources of variability (e.g., age, weight, litter, or batch of reagents). This allows you to isolate and remove the effect of these variables from your analysis, making the treatment effect clearer [27].

- 2. Increase Randomization: Randomly assign subjects to treatment or control groups. This helps to evenly distribute unmeasured, confounding variables across all groups, reducing systematic bias [29] [27].

- 3. Use Control Variables: Keep as many conditions as possible constant across all experimental units (e.g., diet, lighting, time of day) to ensure any observed effects are due to the independent variable alone [29].

Issue 2: Ethical Dilemma Involving a Control Group

Problem: Withholding a potentially beneficial intervention from the control group for the sake of comparison raises ethical concerns.

Solution: Utilize ethical and scientifically sound alternatives to a pure "no treatment" control.

- 1. Use an Active Control: Instead of a placebo or no treatment, provide the control group with the current standard of care or best available treatment. This tests the new intervention against what is already considered effective [23].

- 2. Adopt a Dose-Response Design: Compare multiple doses of the new intervention. This avoids a true "no treatment" group and can provide more informative data on the optimal dosing level.

- 3. Plan for Post-Study Access: Ensure that all participants, including those in the control group, have access to the effective intervention after the study is successfully completed [23].

Issue 3: Sample Preparation is a Major Bottleneck and Source of Cost

Problem: Sample preparation is time-consuming, leads to significant analyte loss, and consumes expensive reagents.

Solution: Optimize and automate the sample preparation workflow.

- 1. Optimize Preparation Parameters: Use experimental design techniques like factorial design to systematically test and identify the optimal conditions for parameters such as temperature, time, and pH. This achieves the best results with the least resources [30].

- 2. Automate Repetitive Tasks: For large numbers of samples, automation (e.g., robotic pipetting) improves accuracy, consistency, and speed while reducing labor costs and human error [30] [31].

- 3. Use Quality Reagents: Poor quality reagents can cause contamination or degradation, forcing you to repeat experiments. Investing in high-quality, compatible reagents reduces waste and error from the start [30].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in ensuring ethical and efficient research.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Ethical & Efficiency Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Consumables (e.g., filters, pipette tips) | Ensure accuracy and prevent contamination during sample handling. | Reduces experimental error and the need for repetition, saving samples and subjects [30]. |

| Proper Anesthetics & Analgesics | Prevent pain and distress in animal subjects during and after procedures. | Core to the "Refinement" principle of the 3Rs; is an ethical imperative for humane treatment [24]. |

| Cell Culture Systems | Used for in vitro modeling of biological processes. | Serves as a Replacement for live animals in early-stage toxicity or efficacy screening [22] [24]. |

| Standard of Care Therapeutics | The current best-available treatment for an active control group. | Addresses the ethical concern of withholding treatment from human participants or animal subjects [23]. |

| Calibrated Standards & Controls | For instrument calibration and quality control of assays. | Ensures data accuracy and reproducibility, preventing waste of resources on invalid results [30] [31]. |

Experimental Workflow for Ethical and Efficient Design

The diagram below outlines a structured workflow that integrates ethical and efficiency checkpoints into the experimental design process.

Ethical and Efficient Experimental Workflow

The 3Rs Framework for Animal Research

This table provides a detailed breakdown of the "3Rs" principle, which is the ethical cornerstone of humane animal experimentation.

| Principle | Goal | Detailed Methodologies & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Replacement | Use non-animal alternatives | Complete Replacement: Use of computer models, human cell cultures, or epidemiological studies [24]. Incomplete Replacement: Using cells or tissues derived from humanely killed animals (e.g., serum for cell culture) to avoid using live animals for the entire experiment [24]. |

| Reduction | Minimize the number of animals used | Statistical Consultation: Using power analysis to determine the minimum number of animals needed for statistically significant results [24]. Improved Techniques: Using advanced imaging or data analysis to get more information from each subject [24]. Sharing Data: Avoiding duplication of experiments through literature reviews and data sharing [24]. |

| Refinement | Minimize pain and distress | Humane Endpoints: Setting early endpoints for experiments (e.g., specific tumor size or clinical sign) rather than death [24]. Proper Analgesia: Using appropriate anesthetics and pain relief for all potentially painful procedures [24]. Environmental Enrichment: Providing housing that allows for the expression of natural behaviors (e.g., shelters, social groups) [24]. |

From Theory to Bench: Implementing DOE to Streamline Sample Preparation Workflows

In the context of research aimed at reducing sample preparation time and cost, selecting the correct experimental design is a critical first step. Efficient design allows you to gather the maximum amount of information from a minimal number of experiments, directly saving on reagents, materials, and valuable researcher time. This guide compares three powerful design approaches—Fractional Factorial, D-Optimal, and Taguchi designs—to help you select the right methodology for your specific experimental challenges.

Comparison of Design Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three experimental design methods to provide a quick overview.

| Feature | Fractional Factorial Design | D-Optimal Design | Taguchi Design | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Efficiently screen a large number of factors to identify the most important ones [32]. | Maximize the information gained for a specific model with a limited number of runs [33]. | Optimize process performance and robustness while reducing variation [34] [35]. | |

| Typical Use Case | Initial factor screening when many factors are involved [32]. | Constrained design spaces or non-standard models (e.g., with quadratic terms) [33]. | Industrial process improvement and making products robust to environmental "noise" [34]. | |

| Design Basis | Pre-defined, orthogonal arrays that fractionate a full factorial [34] [32]. | Computer algorithm that selects runs from a candidate set to maximize |X'X | [33] [36]. | Pre-defined, highly fractionated orthogonal arrays based on linear graphs [34]. |

| Information on Interactions | Varies by design Resolution; some interactions may be confounded (aliased) [32]. | Model-dependent; you can specify which interactions to include, but estimates may be correlated [33]. | Requires pre-selection of interactions to study before the experiment is run [34]. | |

| Key Advantage | High efficiency and clarity for screening; cost-effective [32] [37]. | Flexibility for complex models and constrained experimental regions [33]. | Very attractive for practitioners due to high fractionation and focus on robustness [34]. | |

| Key Disadvantage | Loss of information on higher-order interactions due to aliasing [32] [37]. | "Optimality" is model-dependent; designs are not guaranteed to be orthogonal [33]. | Risky if interactions are not correctly identified in advance [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. I have more than 5 factors to investigate and am very limited by sample preparation time and cost. Which design should I start with?

For screening many factors with limited resources, a Fractional Factorial Design is often the most appropriate starting point [32]. It is specifically designed to identify the "vital few" factors from the "trivial many" with the fewest experimental runs [37]. For example, studying 6 factors can be reduced from a full factorial requiring 64 runs to a fractional factorial requiring only 16 or even 8 runs, offering tremendous savings in time and cost [32].

2. What does the "Resolution" of a Fractional Factorial Design mean, and why is it important?

Resolution indicates the level of confounding between the effects in your design and is crucial for correct interpretation [32].

- Resolution III: Main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions. Use these with caution, only when interactions are negligible [32].

- Resolution IV: Main effects are not confounded with each other or with two-factor interactions, but two-factor interactions are confounded with one another. This is a popular compromise between information and cost [34] [32].

- Resolution V: Main effects and two-factor interactions are not confounded with each other. This provides high-quality information but at a higher cost [32].

3. My experimental region has constraints; some factor combinations are impossible or too expensive to run. Which design can handle this?

A D-Optimal Design is specifically suited for this scenario [33]. You can define a candidate set of all feasible experimental runs, and the algorithm will select the best subset from this custom space to build your design, something pre-defined classical designs cannot do.

4. How do I approach interactions with a Taguchi design?

Taguchi designs require you to decide which interactions are likely to be significant before conducting the experiment, using prior process knowledge and linear graphs [34]. This differs from standard factorial designs, where you often analyze the data first to see which interactions are important. An incorrect pre-selection in a Taguchi design can lead to missing significant interactions [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Selecting the Right Experimental Design

Use the following workflow to guide your initial selection.

Guide 2: Resolving Confounding in Fractional Factorial Designs

If you discover that important effects are aliased in your results, follow this protocol.

Problem: After running a Resolution III or IV fractional factorial, you cannot determine which of two confounded effects is truly significant.

Methodology:

- Identify the Alias Structure: Before the experiment, always check the alias table from your statistical software to understand the confounding pattern [34]. For example, you might find that factor A is confounded with the BC interaction (A = BC).

- Apply the Heredity Principle: After analyzing the data, use the heredity principle—significant interactions are more likely to occur between factors that themselves have significant main effects [34].

- Augment the Design: If the heredity principle does not provide a clear answer and the confounded effect is critical, you need to augment your design. This involves running additional, strategically chosen experiments to "break" the alias [33]. Software tools can often generate a set of follow-up runs to de-alias the specific effects of interest.

Guide 3: Implementing a D-Optimal Design for a Custom Model

This protocol outlines the steps to generate a D-Optimal design when standard designs are not suitable.

Objective: To create an experimental design that efficiently fits a specified model, given a limited number of runs and a constrained experimental region.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define the Model: Specify the mathematical model you wish to fit (e.g., a quadratic model: Y = β₀ + βâ‚A + β₂B + β₃A² + β₄B² + β₅AB).

- Create the Candidate Set: Generate a comprehensive list of all technically feasible experimental runs. This is often a full factorial of all possible factor levels you are willing to consider, excluding any impossible combinations [33]. For example, with factors at 5, 2, and 2 levels, your candidate set would have 5x2x2=20 points.

- Specify the Number of Runs: Determine the maximum number of experiments you can perform, based on cost and time constraints for sample preparation.

- Run the Algorithm: Use statistical software (e.g., MATLAB, Minitab, JMP) with a D-optimal algorithm (

rowexch,cordexch, etc.) to select the best set of runs from your candidate set for your specified model and run count [36]. The algorithm maximizes the determinant |X'X|, minimizing the generalized variance of your parameter estimates [33]. - Check Design Diagnostics: Examine the D-efficiency value and the standard error of prediction across the design points. A higher D-efficiency indicates a better design [33].

- Randomize Runs: Once satisfied, randomize the order of the selected runs before execution to avoid systematic bias.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Workflows

The following table lists key materials and systems that are integral to implementing high-throughput, cost-efficient experiments, directly supporting the thesis of reducing sample preparation time.

| Item | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Automated Sample Preparation System | Drives productivity and accuracy by performing labor-intensive, repetitive tasks (e.g., pipetting) consistently and without fatigue, enabling high-throughput experimentation [38]. |

| Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses reagents and samples in micro-volumes, reducing human error and reagent consumption, which directly lowers costs and improves reproducibility [38]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Automation | Automates the complex, multi-step library preparation workflow for NGS, increasing throughput to thousands of samples per day while maintaining high data quality [38]. |

| Microfluidic Systems | Optimizes reagent use by drastically reducing reaction volumes and dead volume, leading to significant cost savings, especially with expensive reagents [38]. |

In biopharmaceutical research and development, assays are fundamental procedures used to evaluate the biological effects of drug candidates on molecular or biochemical targets [39]. However, the cost of running these experiments is substantial, driven by expensive reagents, scientist time, equipment usage, and consumables [5]. Estimates indicate that pharmaceutical companies can invest up to 40% of their revenue in R&D, with the industry's Internal Rate of Return falling to just 1.2% in 2022 [5].

The rising costs have intensified the need for more efficient experimental approaches. One powerful solution that has emerged is Design of Experiments (DOE), a statistical methodology that enables researchers to systematically investigate multiple factors simultaneously while significantly reducing experimental runs and associated costs [5]. Within the DOE framework, D-optimal design represents a particularly efficient approach for optimizing assay conditions while minimizing resource consumption [40].

This case study examines how D-optimal design was successfully implemented to halve the use of expensive reagents in a critical assay while maintaining data quality and reliability.

Understanding D-Optimal Design

What is D-Optimal Design?

D-optimal design is a statistical approach to experimental design that selects a subset of experimental conditions to maximize the determinant of the information matrix (X'X), where X is the design matrix [40]. This mathematical criterion ensures that the selected experimental runs provide the maximum possible information about the system being studied while minimizing the variance of estimated parameters [40] [41].

Unlike traditional experimental methods such as One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) or full factorial designs, D-optimal design does not require testing all possible factor combinations [40]. Instead, it strategically selects the most informative experimental points, making it exceptionally efficient for complex systems with multiple factors.

Key Benefits for Assay Development

- Efficiency: Dramatically reduces the number of experimental runs required [40]

- Cost-effectiveness: Lowers consumption of expensive reagents and resources [5]

- Enhanced accuracy: Provides better parameter estimates for more reliable models [40]

- Robustness: Creates processes that are inherently robust to external variations [5]

- Interaction detection: Effectively identifies interactions between multiple factors [5]

Case Study: Halving Expensive Reagent Use

Experimental Background and Challenge

A top-20 pharmaceutical company faced significant costs in running an expensive assay that required large amounts of costly cytokines and growth factors, typically ranging from $370-$860 for 10-100µg [5]. Their traditional approach used a full factorial design requiring 672 experimental runs, consuming substantial quantities of these expensive reagents and requiring extensive researcher time.

The research team sought to reduce costs while maintaining the quality and reliability of their assay results. Their objective was to identify conditions that would minimize reagent use without compromising the assay's performance metrics.

Methodology Implementation

The team implemented a D-optimal design to investigate a wide selection of factors influencing assay performance. The methodology included:

Factor Identification: Key factors affecting assay performance were identified, including reagent concentrations, incubation times, and temperature parameters.

Experimental Design: A custom D-optimal design was created using statistical software (potentially JMP, Design-Expert, or R packages like AlgDesign) [40]. This design specified only 108 experimental runs compared to the 672 runs required for a full factorial approach.

Model Validation: The team employed validation techniques including residual analysis to ensure model assumptions were met [40].

The mathematical foundation of this approach maximized the determinant of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), where F = X'X, with X representing the design matrix [40]. This optimization ensured maximum information gain from each experimental run.

Results and Cost Savings

The implementation of D-optimal design yielded significant benefits:

Table: Comparative Results of Full Factorial vs. D-Optimal Design

| Parameter | Full Factorial Design | D-Optimal Design | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of experimental runs | 672 | 108 | 6.2x reduction |

| Expensive reagent consumption | Baseline | ~50% of baseline | Approximately halved |

| Assay quality | Maintained | Maintained | Similar performance |

| Resource requirements | High | Significantly reduced | Substantial cost savings |

The investigation resulted in a model with two peak conditions, one of which approximately halved expensive reagent use while maintaining similar assay quality [5]. This outcome demonstrated that D-optimal design could identify experimental conditions that significantly reduced costs without compromising data integrity.

Implementation Framework for D-Optimal Design

Step-by-Step Protocol

Implementing D-optimal design for assay optimization follows a systematic process:

Define Experimental Objectives

- Clearly identify primary response variables to optimize

- Establish success criteria for the assay

- Determine constraints and practical limitations

Select Factors and Levels

- Identify continuous factors (e.g., temperature, concentration, time)

- Identify categorical factors (e.g., reagent types, methods)

- Establish appropriate ranges for each factor based on experimental feasibility and physiological relevance [42]

Choose Experimental Design Type

Generate Design Matrix

- Use statistical software (R, Python, JMP, Design-Expert) to create the D-optimal design [40]

- Validate design properties and power

- Randomize run order to minimize confounding effects

Execute Experiments and Collect Data

- Follow designed experimental protocol precisely

- Implement quality control measures

- Document any deviations from the planned protocol

Analyze Results and Build Model

- Use regression analysis to model relationship between factors and responses

- Validate model assumptions through residual analysis [40]

- Identify significant factors and interactions

Verify Optimal Conditions

- Conduct confirmation runs at predicted optimal conditions

- Compare actual results with model predictions

- Refine model if necessary

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Their Functions in D-Optimal Assay Optimization

| Material/Resource | Function | Considerations for Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Expensive reagents (cytokines, growth factors) | Critical assay components | Primary target for reduction through optimal concentration finding [5] |

| Statistical software (JMP, R, Design-Expert) | Design generation and analysis | Essential for implementing D-optimal approach [40] |

| Liquid handling systems | Precise reagent dispensing | Automated systems improve reproducibility and minimize waste [43] |

| Microplates (96, 384, 1536-well) | Experimental platform | Miniaturization reduces reagent volumes [42] |

| Detection instrumentation | Signal measurement | Modern readers with temperature control enhance reproducibility [42] |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate Model Fit After D-Optimal Experimentation

Symptoms:

- Poor correlation between predicted and actual results

- High variability in confirmation runs

- Residual plots showing non-random patterns

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Important factors omitted from initial experimental design

- Solution: Conduct preliminary factor screening experiments to identify critical variables before D-optimal design

- Cause: Insufficient model complexity (e.g., using linear model when quadratic terms are needed)

- Solution: Augment design with additional points to support higher-order models

- Cause: Experimental error larger than anticipated

- Solution: Replicate critical points to better estimate error variance and refine model [40]

Issue 2: Constrained Experimental Space Limitations

Symptoms:

- Difficulty generating feasible experimental combinations

- Software cannot create design within specified constraints

- Optimal conditions fall at boundary of experimental space

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overly restrictive factor ranges

- Solution: Revisit factor boundaries based on physiological relevance and practical feasibility [42]

- Cause: Complex constraints between multiple factors

- Solution: Use specialized algorithms for constrained D-optimal designs (e.g., CDsampling R package) [44]

- Cause: Mixed factor types (continuous and categorical) with limited runs

- Solution: Prioritize factors based on preliminary knowledge and consider separate designs for different categorical levels [40]

Issue 3: Clusterization of Sampling Points

Symptoms:

- D-optimal design places multiple runs at identical or very similar conditions

- Inadequate coverage of the experimental space

- Limited ability to estimate all model parameters

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Algorithm converging to local optimum

- Solution: Use multiple random starts in design generation algorithm [45]

- Cause: Too few runs for the model complexity

- Solution: Increase number of experimental runs or reduce number of factors in model [45]

- Cause: Correlations between factors in candidate set

- Solution: Review factor selection and eliminate redundant factors [45]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does D-optimal design compare to traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approaches for assay development?

A1: D-optimal design is substantially more efficient than OFAT approaches. While OFAT varies one factor while holding others constant, D-optimal design systematically explores multiple factors simultaneously. This enables identification of factor interactions that OFAT would miss, provides more complete understanding of the experimental space, and typically requires fewer total runs to achieve better models. Case studies have shown D-optimal designs achieving 6-fold reductions in experimental runs compared to full factorial designs while obtaining equivalent or superior information [5].

Q2: When should I consider using D-optimal design instead of other DOE methods like fractional factorial or central composite designs?

A2: D-optimal design is particularly valuable in these scenarios:

- When dealing with constrained experimental spaces where traditional designs are impossible

- When working with irregularly shaped experimental regions

- When adding runs to an existing experimental design

- When dealing with resource limitations that prevent running full factorial or standard fractional factorial designs

- When working with mixed factor types (both continuous and categorical) in the same design [40]

Q3: What are the key assumptions of D-optimal design and how can I validate them?

A3: Key assumptions include:

- Linearity: The relationship between factors and responses can be adequately modeled by the chosen model form

- Independence: Experimental errors are independent

- Constant Variance: Variance of errors is constant across the experimental space

- Normality: Errors are normally distributed

Validation techniques include:

- Residual analysis to check for patterns

- Normal probability plots of residuals

- Actual vs. predicted value plots

- Confirmation runs at optimal conditions [40]

Q4: How can I implement D-optimal designs with limited statistical expertise?

A4: Several user-friendly software options are available:

- Commercial software: JMP and Design-Expert provide intuitive interfaces for generating D-optimal designs

- R packages: AlgDesign and OptimalDesign offer powerful capabilities for users with some programming experience [40]

- Python libraries: pyDOE2 and statsmodels provide DOE capabilities including D-optimal designs [40]

Many of these tools include wizards and tutorials to guide users through the design process. However, consulting with a statistician for complex designs is still recommended.

Q5: Can D-optimal design be applied to cell-based assays with biological variability?

A5: Yes, D-optimal design can be highly effective for cell-based assays. To account for biological variability:

- Include replication in the design to better estimate error variance

- Consider blocking structure to account for batch effects

- Use appropriate model structures that acknowledge biological systems often show nonlinear responses

- Ensure environmental factors like temperature are carefully controlled, as these significantly impact assay reproducibility [42]

The case study of Oxford Biomedica demonstrated successful application of DOE to optimize lentiviral vector transduction, achieving an 81% reduction in variability alongside significant resource savings [5].

The implementation of D-optimal design presents a powerful methodology for substantially reducing assay development costs while maintaining or even improving data quality. The case study demonstrates that approximately 50% reduction in expensive reagent use is achievable while maintaining assay performance through strategic experimental design.

Future directions in this field include:

- Integration with automation: Combining D-optimal design with automated liquid handling systems for enhanced reproducibility and efficiency [43]

- Miniaturization approaches: Implementing D-optimal designs in miniaturized assay formats to further reduce reagent consumption [42]

- Bayesian extensions: Incorporating Bayesian methods for adaptive optimal designs that evolve as data is collected [45]

- Cross-disciplinary applications: Extending these methodologies beyond pharmaceutical development to areas like food science and materials development, as demonstrated by applications in Hibiscus tea optimization [46]

As the pressure for cost-efficient drug discovery intensifies, statistical approaches like D-optimal design will become increasingly essential tools in the researcher's toolkit, enabling more informative experiments with fewer resources and accelerating the development of new therapeutics.

Your Fractional Factorial Design FAQs

What is a Fractional Factorial Design and why should I use it?

A Fractional Factorial Design is a statistical method for investigating the effects of multiple factors (variables) on a response by testing only a carefully selected subset of all possible factor combinations [47]. You should use it to achieve significant resource savings; it can reduce your experimental runs by 50%, 75%, or more compared to a Full Factorial Design, which requires testing every single combination [48] [49]. This makes it an indispensable tool for initial screening experiments when you have many factors and need to identify the most important ones quickly and cost-effectively [50].

What does 'Resolution' mean, and which one should I choose for my experiment?

Resolution is a critical property of a fractional design that tells you which effects in your experiment are confounded, or aliased, with one another [47] [50]. In practice, this means you cannot distinguish between aliased effects. The choice of resolution involves a trade-off between experimental size and the clarity of the information you obtain [32].

The table below summarizes the most common resolution levels:

| Resolution | Key Capabilities | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Estimate main effects [47]. | Main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions [47] [50]. Use with caution. | Initial screening of many factors where two-factor interactions are assumed to be negligible [51]. |

| IV | Estimate main effects unconfounded by two-factor interactions [47]. | Two-factor interactions are confounded with other two-factor interactions [47] [50]. | A safe and common choice for screening, providing good confidence in main effects [32]. |

| V | Estimate main effects and two-factor interactions unconfounded by other two-factor interactions [47]. | Two-factor interactions are confounded with three-factor interactions (which are often negligible) [47] [32]. | When you need clear information on both main effects and two-way interactions. |

How do I generate a Fractional Factorial Design?

Generating a design involves a few key steps [48] [32]:

- Define Objectives & Factors: Clearly state your goal. Select the

kfactors you wish to investigate and set their high (+) and low (-) levels. - Choose Fraction & Resolution: Decide on the fraction size (e.g., 1/2, 1/4) based on your resources. This determines the resolution and the number of runs

N, calculated asN = 2^(k-p)wherepis the number of generators [47] [50]. - Select Generators: Choose generators (e.g.,

D = ABC) to define how the levels of the additional factors are determined based on the base design. This establishes the defining relation (e.g.,I = ABCD) [47] [50]. - Construct Design Matrix: Use the generators to create a table of all experimental runs. Statistical software like Minitab, JMP, or R greatly simplifies this process [48] [49].

The workflow for this process is summarized in the following diagram:

I've run my experiment and found significant effects, but they are aliased. What can I do?

When significant effects are aliased, you cannot be sure which one is the true active effect. To break the aliasing and deconfound these effects, use a Fold Over technique [50]. This involves running a second, complementary fraction where the signs for all factors (or a specific subset) are reversed [50]. Combining the original data with the fold-over data effectively doubles the experiment size and allows you to separate the previously confounded effects.

What are common pitfalls and how can I avoid them?

- Pitfall 1: Ignoring the Alias Structure. Assuming all estimated effects are clear without checking what they are confounded with.

- Pitfall 2: Assuming All Interactions are Zero.

- Solution: If a main effect appears significant and is aliased with a strong two-factor interaction (e.g., in Resolution III designs), the interaction could be the real driver. Use prior knowledge or a follow-up experiment to verify [32].

- Pitfall 3: Choosing an Incorrect Generator.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key conceptual "reagents" for designing and executing a fractional factorial study.

| Item / Concept | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Design Generators | Rules (e.g., D = ABC) that define how to construct the fractional design from a full factorial, determining which effects are aliased [47] [50]. |

| Defining Relation | The complete set of identity relations (e.g., I = ABD = ACE = BCDE) from which the entire alias structure can be derived [47]. |

| Alias Structure | A table showing which effects in the model are confounded and cannot be estimated separately. This is the direct result of the defining relation [47] [50]. |

| Resolution | A single value (III, IV, V, etc.) that summarizes the overall confounding pattern of the design, guiding the experimenter on its capabilities and limitations [47]. |

| Analysis Software (e.g., Minitab, JMP, R) | Essential tools for generating the design matrix, randomizing run order, and analyzing the resulting data to estimate effects and identify significance [48] [49]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Practical Screening Example

Objective: To screen five factors (A, B, C, D, E) influencing a chemical reaction yield to identify the most impactful ones for future optimization. A full factorial would require 2^5 = 32 runs.

Methodology: A 2^(5-1) Fractional Factorial Design

- Design Selection: A half-fraction (

p=1) is selected, requiring2^(5-1) = 16runs. This is a Resolution V design, meaning no main effect or two-factor interaction is aliased with another main effect or two-factor interaction [50]. - Generator & Defining Relation: The generator is set to

E = ABCD. The defining relation is thereforeI = ABCDE[50]. - Alias Structure: With this high-resolution design, the alias structure is favorable [50]:

- Main effects are aliased only with four-factor interactions.

- Two-factor interactions are aliased only with three-factor interactions.

- Since higher-order interactions are typically negligible, we can clearly interpret the main effects and two-factor interactions.

- Implementation: The design matrix is constructed by first creating a full