Surrogate Models in Expensive Black-Box Optimization: Accelerating Discovery in Biomedicine and Beyond

This article explores the transformative role of surrogate models in tackling computationally expensive black-box optimization problems, with a special focus on applications in drug development and biomedical research.

Surrogate Models in Expensive Black-Box Optimization: Accelerating Discovery in Biomedicine and Beyond

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of surrogate models in tackling computationally expensive black-box optimization problems, with a special focus on applications in drug development and biomedical research. We provide a comprehensive foundation, covering the core challenge of optimizing systems where objective functions are implicit and evaluations require costly simulations or physical experiments. The article delves into key methodological approaches, including ensemble techniques and Gaussian Process regression, and examines their successful application in areas like virtual patient generation and force field parameterization. We further address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world deployment, and discuss rigorous validation frameworks to ensure model reliability and interpretability. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage surrogate-assisted optimization to accelerate their workflows.

The Black-Box Bottleneck: Why Traditional Optimization Fails in Complex Systems

Defining Expensive Black-Box Functions in Engineering and Biomedicine

In the optimization of complex systems across engineering and biomedicine, researchers often encounter problems classified as expensive black-box functions. A black-box function is an unknown system where users can observe inputs and outputs but cannot see the internal mechanisms or obtain gradient information [1]. These functions are deemed "expensive" because each evaluation is computationally intensive, time-consuming, or financially costly, requiring numerous simulations or physical experiments [2] [1]. The core challenge lies in optimizing these systems where traditional methods fail due to unknown objective function characteristics and prohibitive evaluation costs.

Surrogate-Based Optimization (SO) has emerged as a predominant technique addressing this challenge. SO employs a low-cost surrogate model to approximate the expensive black-box function, guiding the optimization process toward the global optimum while significantly reducing the number of expensive evaluations required [1]. This approach is particularly critical in fields like drug development, where surrogate endpoints act as proxies for clinical outcomes, accelerating research when direct measurement would be impractical or unethical [3] [4]. The fundamental trade-off in SO involves balancing exploration of new regions in the function space with exploitation of areas known to be promising, a balance that becomes particularly complex in batch evaluation settings where multiple function evaluations occur simultaneously [1].

Characteristics and Challenges

Defining Characteristics of Expensive Black-Box Functions

Expensive black-box functions exhibit several distinct characteristics that make them particularly challenging for optimization. The table below summarizes their key attributes and the corresponding challenges for researchers.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Expensive Black-Box Functions

| Characteristic | Description | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown Internal Mechanics | Only inputs and outputs are observable; internal processes are not transparent [1]. | Impossible to use derivative-based optimization methods or analytical solutions. |

| High Evaluation Cost | Each function evaluation requires significant computational resources, time, or financial investment [2] [1]. | Limits the number of evaluations that can be practically performed, requiring highly sample-efficient algorithms. |

| Lack of Gradient Information | The objective function's derivatives are typically unavailable or computationally prohibitive to estimate. | Prevents the use of efficient gradient-based optimization techniques. |

| Complex Design Landscape | Often characterized by high dimensionality, multi-modality, and noise [1]. | Difficult to navigate and easily trapped in local optima rather than finding global optimum. |

Domain-Specific Manifestations

The abstract concept of expensive black-box functions manifests differently across engineering and biomedicine domains, though they share fundamental similarities in their optimization challenges.

Table 2: Comparison of Black-Box Functions Across Domains

| Aspect | Engineering Applications | Biomedicine Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Function | Computer simulations (e.g., airfoil design), physical experiments [1]. | Clinical trial outcomes, biological system responses [3] [4]. |

| Evaluation Cost | Computationally expensive simulations requiring hours to days [2]. | Time-consuming clinical trials lasting years, high financial costs, ethical constraints [3]. |

| Typical Surrogates | Machine learning models, simplified physics models [1]. | Biomarkers, laboratory measurements, imaging biomarkers [3] [4]. |

| Validation Requirements | Agreement with high-fidelity models, physical experiments [2] [1]. | Analytical validation, clinical validation, proof of clinical utility [3] [4]. |

In engineering, expensive black-box functions appear in problems such as airfoil design and rover trajectory planning, where each simulation requires substantial computational resources [1]. In biomedicine, the relationship between a drug intervention and patient survival represents a black-box function where clinical endpoints (how patients feel, function, or survive) are expensive to measure due to long trial durations and large sample size requirements [3] [4]. In both domains, the fundamental challenge remains the same: optimizing an unknown, costly system with limited evaluation opportunities.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Surrogate Optimization Algorithms

Rigorous experimental evaluation of surrogate-based optimization algorithms requires standardized benchmarking methodologies. The EXPObench library provides a framework for comparing algorithms on real-life, expensive, black-box objective functions, addressing the historical lack of standardization in the field [2]. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for benchmarking:

Algorithm Selection: Choose diverse surrogate algorithms representing different approaches to the exploration-exploitation trade-off. A recent study compared six different surrogate algorithms on four expensive optimization problems from different real-life applications [2].

Problem Instances: Select benchmark problems from various domains with different characteristics. The EXPObench library includes problems from domains such as DNA binding, airfoil design, and hyperparameter optimization for MNIST classification [2] [1].

Evaluation Metrics: Define appropriate performance metrics, including:

- Convergence speed: The number of expensive function evaluations required to reach a target objective value.

- Solution quality: The best objective value found within a fixed computational budget.

- Robustness: Performance consistency across multiple runs and different problem instances.

Computational Budget: Set limits on the number of expensive function evaluations based on the problem's computational cost and practical constraints [2].

Statistical Analysis: Perform multiple independent runs of each algorithm on each problem instance to account for random variations, using appropriate statistical tests to determine significant performance differences.

This methodology has revealed that the best algorithm choice depends on evaluation time and available computation budget, with the continuous vs. discrete nature of the problem being less important than previously thought [2].

Validating Biomarkers as Surrogate Endpoints

In biomedical research, the use of surrogate endpoints requires rigorous validation to ensure they reliably predict meaningful clinical outcomes. The FDA outlines a comprehensive framework for biomarker validation [3] [4]:

Table 3: Validation Framework for Biomarkers as Surrogate Endpoints

| Validation Stage | Key Activities | Regulatory Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Validation | Assess assay sensitivity, specificity, precision, and reproducibility [3]. | Demonstrates the biomarker can be measured accurately and reliably. |

| Clinical Validation | Demonstrate the biomarker's ability to detect or predict disease state or treatment response [3]. | Establishes a relationship between the biomarker and the clinical outcome of interest. |

| Clinical Utility Evaluation | Evaluate whether using the biomarker improves patient outcomes or decision-making [3]. | Determines if the surrogate endpoint predicts clinical benefit in the specific context of use. |

The validation process requires accumulating evidence from epidemiological studies, therapeutic interventions, and pathophysiological research [4]. For a surrogate endpoint to be considered "validated," it must be supported by strong biological rationale and robust empirical evidence linking it to meaningful clinical outcomes [3]. The level of validation determines the regulatory acceptance:

- Candidate Surrogate Endpoints: Still under evaluation for their ability to predict clinical benefit [4].

- Reasonably Likely Surrogate Endpoints: Supported by strong mechanistic and/or epidemiologic rationale but insufficient clinical data for full validation; can support accelerated approval programs [4].

- Validated Surrogate Endpoints: Supported by clear mechanistic rationale and clinical data providing strong evidence that an effect on the surrogate endpoint predicts a specific clinical benefit [4].

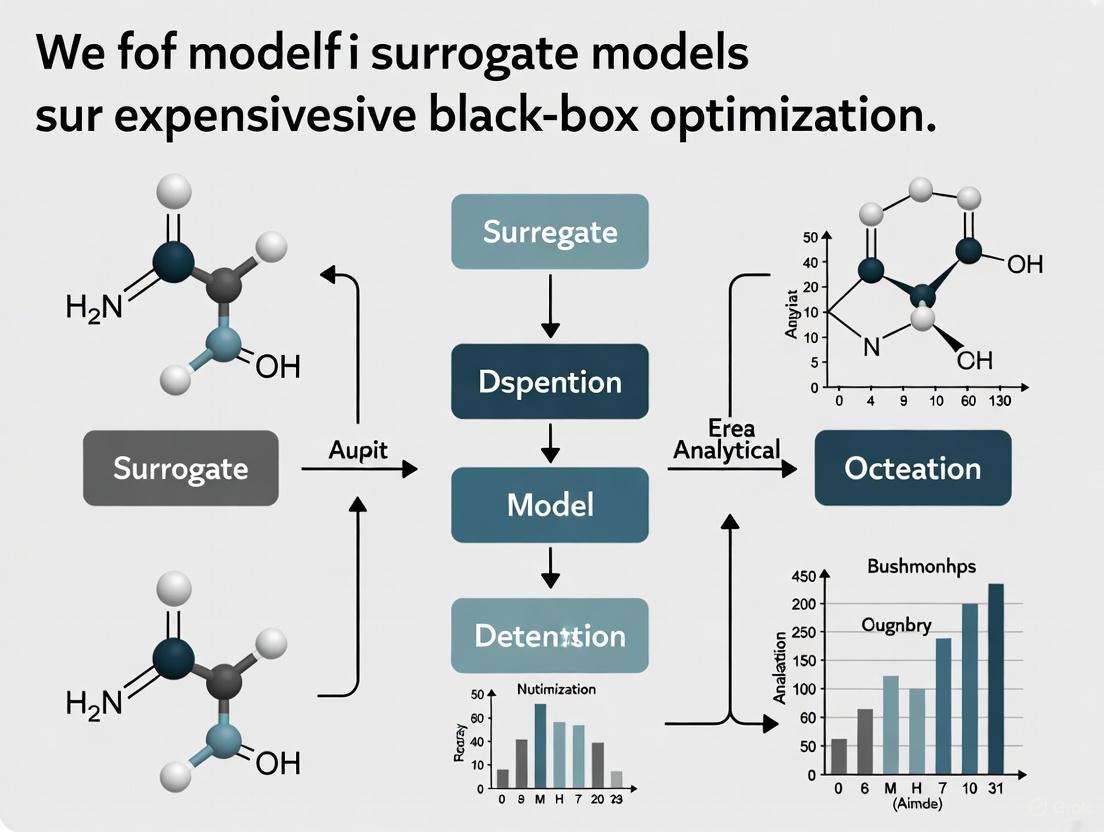

Visualization of Core Concepts

Surrogate Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative process of surrogate-based optimization for expensive black-box functions:

Surrogate Optimization Process

This workflow highlights the critical role of the acquisition function in managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off—a fundamental challenge in surrogate optimization where the algorithm must balance between exploring new regions of the search space and exploiting areas known to be promising [1]. The batch evaluation path is particularly relevant for complex systems where multiple evaluations can be performed simultaneously, adding complexity to the optimization process [1].

Biomarker Validation Pathway

The pathway for developing and validating biomarkers as surrogate endpoints in biomedical research involves multiple stages of evidence generation:

Biomarker Validation Pathway

This pathway emphasizes that biomarker validation is a progressive process requiring different types of evidence at each stage. The context of use is particularly critical, as a biomarker may be validated for one specific application but not others [4]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA require this rigorous validation before accepting surrogate endpoints in place of clinical outcomes for drug approval [3] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation and implementation of surrogate-based optimization methods require specific computational tools and resources. The table below outlines key resources mentioned in the research literature.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Surrogate Optimization and Biomarker Development

| Resource/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXPObench Library | Benchmark Library | Standardized benchmarking of surrogate algorithms on expensive optimization problems [2]. | Provides real-life expensive optimization problems for algorithm comparison and development. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Algorithmic Framework | Sequential design strategy for optimizing black-box functions [2]. | Hyperparameter tuning, simulation-based optimization in engineering and biomedicine. |

| Surrogate Endpoint Table | Regulatory Resource | Lists surrogate endpoints used for drug/biologic approval [4]. | Guides drug developers on acceptable surrogate endpoints for specific disease contexts. |

| Biomarker Qualification Program | Regulatory Pathway | Supports development of biomarkers for specific contexts in drug development [4]. | Provides framework for qualifying biomarkers for use in regulatory decision-making. |

These resources represent essential infrastructure for researchers working with expensive black-box functions. The EXPObench library addresses the critical need for standardization in evaluating surrogate algorithms [2], while the FDA's Surrogate Endpoint Table and Biomarker Qualification Program provide regulatory clarity for drug developers using surrogate endpoints in clinical trials [4].

Expensive black-box functions represent a fundamental challenge across engineering and biomedicine, where system complexity and evaluation costs prevent traditional optimization approaches. Surrogate-based methods have emerged as powerful strategies for addressing these challenges, employing low-cost models to guide optimization while minimizing expensive evaluations. In engineering, these methods enable efficient optimization of computational simulations and physical experiments, while in biomedicine, surrogate endpoints accelerate drug development when direct clinical outcome measurement is impractical.

The effective use of these approaches requires rigorous methodologies, including standardized benchmarking for optimization algorithms and comprehensive validation frameworks for biomarkers. Visualization of workflows and validation pathways helps researchers navigate these complex processes, while specialized tools and resources provide the necessary infrastructure for implementation. As research in both fields advances, the continued development and refinement of surrogate-based approaches will be essential for tackling increasingly complex optimization challenges in both engineering and biomedicine.

The escalating computational cost of high-fidelity simulations represents a critical bottleneck in scientific and engineering disciplines, from aerodynamics to drug development. This whitepaper examines how surrogate modeling and reduced-order modeling provide mathematically principled frameworks for overcoming this crisis. By constructing efficient approximations of expensive "black-box" functions, these techniques enable rapid exploration of design spaces, real-time simulation, and robust optimization while maintaining acceptable accuracy. The integration of machine learning with traditional physics-based modeling, alongside emerging paradigms like AI-enhanced turbulence modeling and Large Language Model-based optimizers, is creating a transformative pathway toward sustainable computational research.

Computational simulations have become indispensable across industrial and research sectors, but their increasing complexity creates a significant cost crisis.

Table 1: Computational Fluid Dynamics Market Growth and Drivers

| Metric | Value & Forecast | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market (2024) | USD 1.5 Billion [5] | Need to reduce prototyping costs and accelerate time-to-market [5] |

| Projected Market (2032) | USD 3.25 Billion [5] | Rising demand for electric vehicles and efficient thermal management systems [5] |

| CAGR (2024-2032) | 11.9% [5] | Growing complexity of products and need for high-fidelity simulations in defense/aerospace [5] |

| Alternative Forecast (2029) | Increase of USD 1.23 Billion from 2025 [6] | Cloud-based solutions, AI-powered simulations [6] [7] |

This growth reflects not only expanding adoption but also the critical need to address the underlying computational costs. In aerospace, high-fidelity CFD simulations can improve fuel efficiency by 12%, and in automotive engineering, they can lower energy use by 15% [6]. However, achieving these results traditionally requires massive computational resources. Similarly, in pharmaceutical development, Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models face intractable complexity when integrating multiscale biological data for personalized treatment optimization [8].

Surrogate Modeling: A Mathematical Foundation for Efficiency

Surrogate modeling addresses the computational cost crisis by constructing fast-to-evaluate approximations of high-fidelity models. These metamodels are built from a limited set of carefully chosen simulations and then used for tasks requiring numerous evaluations, such as optimization, uncertainty quantification, and real-time control.

Core Methodologies and Theoretical Frameworks

The fundamental approaches to surrogate modeling include:

- Physics-Based Reduced-Order Models (ROMs): These techniques project the high-dimensional equations governing a system (e.g., Navier-Stokes equations) onto a lower-dimensional subspace capturing the dominant system behaviors. Methods include Proper Orthogonal Decomposition and Gaussian Process Regression [6] [9].

- Data-Driven Surrogate Models: These models learn the input-output relationship of a system from simulation or experimental data, without explicit knowledge of the underlying physics. Machine Learning methods like Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are particularly powerful for this task [10] [8].

- Hybrid Mechanistic/ML Models: This emerging framework blends mechanistic understanding (e.g., physics-based ODEs) with data-driven ML components, leveraging the strengths of both approaches for systems where first-principles models are incomplete [8].

Experimental Protocols and Quantitative Validation

The development and validation of a surrogate model follow a rigorous, iterative protocol to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Workflow for Surrogate Model Development

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for developing and deploying a surrogate model.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol addresses the high cost of matrix operations in large-scale CFD surrogate modeling.

- Problem Setup: Define the geometric body and flow conditions for the high-fidelity CFD simulation.

- Local Error-Driven Optimization:

- Run initial high-fidelity simulations to identify that far-field physical parameters exhibit simpler relationships, while high-error regions are concentrated near geometric bodies [11].

- Introduce an optimization strategy that captures key points in these high-error regions [11].

- Construct a local surrogate model to iteratively optimize the shape parameters of a Radial Basis Function (RBF) network, replacing global flow field parameters with locally optimal ones [11].

- Validation: Compare the flow field predictions of the enhanced RBF surrogate against traditional CFD results and global optimization methods.

Quantitative Results: This method achieved a reduction in computational time of over 99% compared to traditional CFD, with the local parameter optimization strategy reducing costs by over 90% compared to global optimization methods, while maintaining an average prediction error below 2% [11].

This protocol details the development of a surrogate for textured journal bearings.

- Data Generation:

- Develop accurate CFD models employing a dynamic mesh algorithm.

- Execute simulations across a designed range of texture configurations to generate a comprehensive dataset.

- Model Selection and Training:

- Train and compare three ML methods: Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR).

- Select the best-performing method (ANN demonstrated superior prediction performance [10]).

- Enhance the ANN's prediction accuracy through an architecture design based on cross-validation and further optimization using a genetic algorithm, all without needing additional CFD datasets [10].

- Validation: Assess the final model's accuracy against a held-out test set of CFD results.

Quantitative Results: The genetic algorithm optimization improved the average prediction accuracy from 95.89% to 98.81%, and reduced the maximum error from 13.17% to 3.25% [10].

The LLM-based Entropy-guided Optimization with kNowledgeable priors (LEON) framework is a novel approach for black-box optimization in personalized treatment.

- Problem Formulation: Frame personalized medicine as a conditional black-box optimization problem: find a treatment strategy that optimizes a patient's clinical outcome based on their covariates [12].

- Constrained Optimization:

- Acknowledge that surrogate models (e.g., digital twins) are imperfect and may fail on unseen patient-treatment combinations [12].

- Apply constraints to limit the optimization to treatments that (a) have reliable surrogate predictions, and (b) are consistently proposed as high-quality by the LLM based on its embedded domain knowledge (e.g., from medical textbooks) [12].

- Implementation via 'Optimization-by-Prompting':

- Use the LLM as a stochastic engine to propose treatment designs in natural language.

- Guide the LLM's proposals using an objective function derived from the LEON framework, which incorporates the surrogate's output and a measure of the LLM's own certainty (entropy over equivalent treatment classes) [12].

Quantitative Results: In experiments on real-world treatment design problems, LEON achieved an average rank of 1.2 when compared against 10 other baseline optimization methods [12].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Surrogate Model Performance

| Application Domain | Surrogate Technique | Computational Saving | Accuracy Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Flow Field Prediction [11] | Enhanced Radial Basis Function (RBF) | >99% vs. traditional CFD; >90% vs. global optimization | Average error < 2% |

| Friction in Textured Journal Bearings [10] | ANN optimized with Genetic Algorithm | Drastic reduction in CFD runs needed | 98.81% average accuracy |

| Pharmaceutical Process Optimization [13] | Surrogate-based framework (Multi-Objective) | High-fidelity model evaluations reduced | Yield improved by 3.63% with high purity |

| Personalized Treatment Design [12] | LLM-based Optimizer (LEON) | Avoids costly in-vivo treatment testing | Outperformed 10 traditional & LLM-based methods |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Platforms

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial CFD Suites | ANSYS Fluent, Siemens STAR-CCM+ [6] | High-fidelity flow simulation, turbulence modeling, and heat transfer analysis. |

| ML/Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Building and training data-driven surrogate models like ANNs. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Genetic Algorithms [10], LEON [12] | Optimizing surrogate model parameters or directly optimizing designs. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | GPU-accelerated solvers [14], Cloud-based CFD [6] | Providing the computational power for high-fidelity simulation and training large surrogates. |

| Reduced-Order Modeling Tools | Operator Inference (OpInf), Sparse Identification (SINDy) [9] | Constructing physics-based low-dimensional models from high-fidelity data. |

| Belumosudil | Belumosudil, CAS:911417-87-3, MF:C26H24N6O2, MW:452.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| STX140 | STX140, CAS:401600-86-0, MF:C19H28N2O7S2, MW:460.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The convergence of AI, HPC, and computational modeling is creating a new paradigm for managing the cost crisis.

- AI-Powered CFD and QSP: Deep-learning-based turbulence modeling and AI-based adaptive meshing are poised to dramatically reduce simulation time and cost [7] [14]. In QSP, AI/ML is transitioning from a tool to an "active partner" that can autonomously propose, refine, and validate models [8].

- Quantum Computing for Simulation: Though nascent, quantum computing holds potential to revolutionize computational performance for specific classes of simulation and optimization problems, with quantum-powered CFD identified as a future trend [7].

- Democratization via Cloud and AI: Cloud-native CFD platforms and AI-assisted workflows are democratizing access to advanced simulation, lowering the barrier to entry for researchers without deep expertise in coding or numerical methods [6] [8].

The computational cost crisis in CFD and QSP is a significant challenge, but it is being systematically addressed by sophisticated surrogate modeling strategies. The experimental protocols and results presented demonstrate that it is possible to achieve orders-of-magnitude reduction in computational expense while preserving the predictive accuracy required for robust engineering design and personalized therapeutic optimization. The future lies in the continued development of hybrid models that seamlessly integrate mechanistic principles with data-driven learning, all within an increasingly automated and accessible computational ecosystem.

In the realm of expensive black-box optimization, where the evaluation of the true objective function requires substantial computational resources or costly physical experiments, surrogate models have emerged as a cornerstone methodology. Also known as metamodels or response surface models, a surrogate model is a cheap-to-evaluate approximation of a complex, computationally intensive process or function. The core premise is to build a mathematical model that learns the input-output relationship from a limited set of expensive function evaluations, creating a predictive model that can be exploited to guide the optimization process efficiently. This approach is particularly vital in scientific and engineering domains where a single function evaluation may involve running a high-fidelity simulation for hours or days, conducting a wet-lab experiment, or—as in the context of drug development—executing a rigorous clinical trial simulation or molecular docking study.

The role of surrogate models within expensive black-box optimization research is to drastically reduce the computational burden while maintaining acceptable solution quality. Traditional optimization algorithms often require thousands of function evaluations to converge to a satisfactory solution, which becomes prohibitive when each evaluation is exceptionally costly. By strategically employing surrogate models, researchers can interpolate between known data points, predict promising new candidate solutions and navigate the design space intelligently without invoking the expensive true function at every step. This paradigm has transformed optimization workflows across numerous disciplines, from aerospace engineering and materials science to pharmaceutical development, where it accelerates discovery while containing computational costs.

Mathematical Foundations and Model Types

Theoretical Framework

Surrogate-assisted optimization operates on a fundamental mathematical framework. Let ( f(\mathbf{x}) ) be the expensive black-box function to be minimized (or maximized), where ( \mathbf{x} ) represents a vector of decision variables within a search space ( \Omega ). The goal is to find ( \mathbf{x}^* = \arg\min{\mathbf{x} \in \Omega} f(\mathbf{x}) ). Given the expense of evaluating ( f ), a surrogate model ( \hat{f}(\mathbf{x}) ) is constructed to approximate ( f ) based on a dataset ( \mathcal{D} = {(\mathbf{x}i, f(\mathbf{x}i))}{i=1}^n ) of initial evaluations.

The surrogate modeling process involves two interdependent components: model selection and experimental design. Model selection concerns choosing the functional form of ( \hat{f} ) (e.g., Gaussian process, neural network, polynomial) and fitting its parameters to the observed data ( \mathcal{D} ). Experimental design involves selecting the points ( \mathbf{x}_i ) at which to evaluate the expensive true function to build and refine the surrogate. This is typically done through adaptive sampling strategies that balance exploration (sampling in uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling where the surrogate predicts good performance).

The general surrogate-assisted optimization loop follows these steps:

- Initial Sampling: Select an initial set of points ( \mathbf{x}1, \mathbf{x}2, ..., \mathbf{x}_n ) using a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) and evaluate them using the expensive function ( f ) to form the initial dataset ( \mathcal{D} ).

- Model Building: Construct the surrogate model ( \hat{f} ) using the collected data ( \mathcal{D} ).

- Surrogate Optimization: Use an efficient optimization algorithm to find candidate points that are optimal according to a criterion (e.g., expected improvement, lower confidence bound) that combines ( \hat{f} ) and its uncertainty.

- Expensive Evaluation: Evaluate the most promising candidate point(s) using the true expensive function ( f ).

- Model Update: Augment the dataset ( \mathcal{D} ) with the new evaluation results and update the surrogate model.

- Termination Check: Repeat steps 3-5 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., budget exhausted, solution quality achieved).

Types of Surrogate Models

Several statistical and machine learning models are commonly employed as surrogates, each with distinct strengths, weaknesses, and applicability domains.

Gaussian Processes (GPs): Also known as Kriging, GPs are a Bayesian non-parametric approach that provides not only a prediction but also an estimate of uncertainty (variance) at any point. This built-in uncertainty quantification makes them particularly valuable for optimization, as it naturally facilitates balancing exploration and exploitation. They are especially effective for modeling continuous, smooth functions with limited data but scale poorly to very large datasets and high dimensions due to ( O(n^3) ) computational complexity for training [15].

Radial Basis Functions (RBFs): RBF models form predictions as a linear combination of basis functions that depend only on the radial distance from the prediction point to the data points. They are flexible interpolators capable of handling irregular, non-linear response surfaces. While they don't naturally provide uncertainty estimates like GPs, they are computationally efficient and have been successfully integrated into global optimization algorithms [16].

Polynomial Regression Models: These are parametric models that fit a polynomial (linear, quadratic, etc.) to the data. They are simple, fast to build and evaluate, and work well for approximating low-order, smooth functions. However, they may lack the flexibility to capture complex, highly non-linear behavior and can be sensitive to outliers. Tools like ALAMO (Automated Learning of Algebraic Models for Optimization) can automate the process of identifying appropriate polynomial structures [16].

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): ANNs are universal function approximators capable of learning highly complex, non-linear relationships from large volumes of data. They scale well to high-dimensional problems. Their drawbacks include the need for relatively large training datasets, careful tuning of architecture and hyperparameters, and the lack of inherent, well-calibrated uncertainty estimates without specialized variants like Bayesian neural networks [16].

Random Forests (RF): As an ensemble method, RF constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their predictions. They are robust to noisy data and can handle mixed variable types (continuous and categorical). However, they are typically not interpolators and may not perfectly fit the training data, which can be a disadvantage if the true function is deterministic [15].

Support Vector Machines (SVM): SVMs, particularly Support Vector Regression (SVR), seek to find a function that deviates at most by a margin from the observed data. They are effective in high-dimensional spaces and memory efficient, but their performance is sensitive to the choice of the kernel and regularization parameters [15].

The following table provides a comparative summary of these key surrogate model types based on recent benchmark studies:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Surrogate Model Types

| Model Type | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Representative Performance (R²/Accuracy) | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process | Built-in uncertainty, strong with limited data | Poor scaling with data size ((O(n^3))) | High accuracy on benchmarks [15] | Low (training), High (prediction) |

| Radial Basis Functions | Flexible interpolator, computationally efficient | No native uncertainty quantification | High accuracy on training data [16] | High |

| Polynomial Regression | Simple, fast, interpretable | Limited to low-order nonlinearities | Good balance of efficiency/reliability [16] | Very High |

| Artificial Neural Networks | Handles complexity & high dimensions | Data-hungry, complex tuning | Fast convergence (e.g., 2 iterations in TRF) [16] | Low (training), High (prediction) |

| Random Forest | Robust to noise, handles mixed variables | Not an exact interpolator | Comparable to GP on early-stage optimization [15] | Medium |

| Support Vector Machine | Effective in high dimensions, memory efficient | Sensitive to hyperparameters | Performance varies with kernel choice [15] | Medium |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Detailed Methodologies for Surrogate Construction and Use

Implementing surrogate models effectively requires a structured, iterative protocol. The following workflow details a standard methodology, adaptable to various model types and application domains.

Diagram 1: Surrogate-assisted optimization workflow

Phase 1: Initial Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Objective: To select an initial set of points in the design space that provides maximum information with a minimal number of expensive evaluations.

- Protocol: Use a model-independent, space-filling design such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS). For a problem with

ddimensions and an initial budget ofnpoints, LHS ensures that each dimension is partitioned intonintervals and each interval is sampled exactly once. This provides better coverage of the design space than random sampling. - Data Collection: Run the expensive black-box function (e.g., a high-fidelity simulation, a molecular docking calculation like RosettaVS [17], or a clinical trial simulation [18]) at each of the

ndesign points. The result is the initial training dataset ( \mathcal{D} = {(\mathbf{x}i, f(\mathbf{x}i))}_{i=1}^n ).

Phase 2: Surrogate Model Construction and Validation

- Objective: To train a surrogate model

Å·that accurately approximatesf(x)based on the initial datasetD. - Protocol:

- Model Selection: Choose a model type based on the problem characteristics (see Table 1). For instance, use Gaussian Processes for problems with limited data and a need for uncertainty quantification, or Neural Networks for large, high-dimensional datasets.

- Training: Fit the model parameters to the dataset

D. For a Gaussian Process, this involves optimizing the kernel hyperparameters to maximize the marginal likelihood. For a Neural Network, this involves minimizing a loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error) via gradient descent. - Validation: Assess the model's predictive accuracy using techniques like cross-validation or a hold-out test set. Common metrics include R² score, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Kendall's Tau rank correlation [19]. The model must be sufficiently accurate before proceeding to the optimization phase.

Phase 3: Model-Based Optimization and Infill Criterion

- Objective: To use the surrogate model to propose new, promising candidate points for evaluation with the expensive function.

- Protocol:

- Define an Acquisition Function: An acquisition function

a(x), derived from the surrogate model, guides the search by balancing prediction and uncertainty. A common choice is the Expected Improvement (EI):EI(x) = (f_min - ŷ(x)) * Φ(Z) + s(x) * φ(Z)fors(x) > 0, whereZ = (f_min - ŷ(x)) / s(x),ŷ(x)is the surrogate prediction,s(x)is its uncertainty,f_minis the best observed value, andΦandφare the standard normal CDF and PDF. This favors points with low predicted values (exploitation) and/or high uncertainty (exploration). - Optimize the Acquisition Function: Find the point

x_candidatethat maximizesa(x). Sincea(x)is cheap to evaluate, this inner optimization can be performed aggressively using a standard optimizer like CMA-ES [15] or a multi-start quasi-Newton method.

- Define an Acquisition Function: An acquisition function

Phase 4: Expensive Evaluation and Model Update

- Objective: To refine the surrogate model with new data, improving its accuracy in promising regions of the search space.

- Protocol:

- Evaluate the expensive function at

x_candidateto obtainf(x_candidate). - Augment the dataset:

D = D ∪ (x_candidate, f(x_candidate)). - Update the surrogate model with the new, augmented dataset.

- Evaluate the expensive function at

- Iteration and Termination: Repeat Phases 3 and 4 until a termination criterion is met. This is typically a maximum number of expensive evaluations, a computational budget, or a stagnation criterion (e.g., no significant improvement in

f_minover a number of iterations).

Advanced Strategy: Trust-Region Framework

To enhance the reliability of surrogate-assisted optimization, especially with local surrogate models, a Trust-Region (TRF) framework is often employed [16]. This method constrains the optimization of the acquisition function to a local region where the surrogate is trusted to be accurate. The trust region is dynamically adjusted based on the performance of the candidate points. If a candidate point leads to significant improvement, the trust region may be expanded; if not, it is contracted. This approach prevents the algorithm from making overly ambitious, unreliable steps based on a poor surrogate prediction in a distant region. Studies have shown that within a TRF, models like Kriging and ANN can achieve convergence in as few as two iterations [16].

Case Studies in Scientific Research

Drug Discovery: AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening

The field of drug discovery provides a compelling case for the power of surrogate modeling. Structure-based virtual screening, which involves computationally docking millions of small molecules into a protein target to predict binding affinity, is prohibitively expensive at scale. To address this, researchers developed RosettaVS, a high-accuracy docking method, and integrated it into an AI-accelerated virtual screening platform [17].

- Surrogate Role: In this platform, a surrogate model is used to approximate the docking score from the RosettaVS method. The model is trained on-the-fly using an active learning loop.

- Implementation: The system begins by docking a small, diverse subset of a multi-billion compound library. The results are used to train a surrogate model that predicts the docking score for unseen compounds. This cheap-to-evaluate surrogate then triages the vast chemical space, selecting only the most promising candidates for the expensive, high-precision RosettaVS docking.

- Outcome: This surrogate-assisted strategy enabled the screening of multi-billion compound libraries against two unrelated protein targets in less than seven days, leading to the discovery of several hit compounds with micromolar binding affinity—a task that would be computationally intractable using high-fidelity docking alone [17].

Model Merging in Large Language Models (LLMs)

In machine learning, merging multiple fine-tuned LLMs into a single, more capable model is an emerging technique. This process involves hyperparameters that significantly affect the merged model's performance, creating a black-box optimization problem.

- The Problem: Evaluating a single merging configuration requires physically merging the models and running benchmark evaluations, which can take several minutes on high-end GPUs. Optimizing these hyperparameters via a brute-force search is therefore infeasible [19].

- Surrogate Solution: Researchers created SMM-Bench, a surrogate benchmark for model merging optimization. They collected a large dataset of merging hyperparameters and their corresponding performance scores on tasks like Japanese mathematics. They then trained surrogate models (e.g., using LightGBM) to predict a merged model's performance directly from its hyperparameters [19].

- Outcome: The resulting surrogate models achieved high prediction accuracy (R² > 0.92), allowing for the development and comparison of hyperparameter optimization algorithms at a fraction of the cost. This enables researchers to efficiently find optimal merging configurations without the need for thousands of time-consuming physical merge-and-evaluate cycles [19].

Table 2: Performance of Surrogate Models in Case Studies

| Application Domain | Expensive Function (Black-Box) | Surrogate Model Used | Key Quantitative Result | Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery (Virtual Screening) [17] | High-precision molecular docking (RosettaVS) | Active learning-based surrogate (AI model) | Discovery of hits with single-digit µM affinity | Screening completed in <7 days for billion-compound library |

| LLM Model Merging [19] | Physical model merging and benchmark evaluation | LightGBM model predicting accuracy from hyperparameters | Surrogate R² scores: 0.950 - 0.962 on test sets | Enables algorithm development without physical merging |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational tools and platforms that function as essential "reagents" for implementing surrogate-assisted optimization in scientific research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surrogate-Assisted Optimization

| Tool / Platform Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Surrogate Modeling | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALAMO [16] | Automated Modeling Tool | Automates the development of accurate algebraic (e.g., polynomial) surrogate models from data. | Integration of carbon capture technologies; general chemical process optimization. |

| CMA-ES [15] [19] | Optimization Algorithm | A state-of-the-art evolutionary strategy often used to optimize the acquisition function in the inner loop of surrogate-assisted optimization. | Black-box optimization benchmarks; hyperparameter tuning for model merging. |

| RosettaVS & OpenVS [17] | Virtual Screening Platform | Provides a high-accuracy docking function and an open-source platform that uses active learning (surrogate modeling) to triage ultra-large chemical libraries. | Drug discovery, lead compound identification for protein targets like KLHDC2 and NaV1.7. |

| SMM-Bench [19] | Surrogate Benchmark | A pre-constructed surrogate model that predicts LLM performance after merging, based on hyperparameters, eliminating the need for physical merging during optimization. | Development and testing of hyperparameter optimization algorithms for model merging techniques. |

| LightGBM [19] | Machine Learning Library | A gradient boosting framework used to build high-performance surrogate models for regression tasks, such as predicting merged model accuracy. | Creating surrogate benchmarks for continuous and mixed-variable optimization problems. |

| LEON [12] | LLM-based Optimizer | Leverages large language models as black-box optimizers, using their internal knowledge as a prior to propose candidate solutions where surrogate models are unreliable. | Personalized medicine treatment design under distribution shift in patient populations. |

| SL 0101-1 | SL 0101-1, CAS:77307-50-7, MF:C25H24O12, MW:516.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| T-5224 | T-5224, CAS:530141-72-1, MF:C29H27NO8, MW:517.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Surrogate models stand as a pivotal technology in the advancement of expensive black-box optimization research. By serving as cheap-to-evaluate approximations, they break the computational bottleneck that hinders progress in fields ranging from drug discovery to artificial intelligence. The continued development of more accurate, data-efficient, and scalable surrogate modeling techniques, coupled with intelligent frameworks like trust regions and active learning, promises to further expand the boundaries of problems we can solve. As evidenced by their transformative impact in virtual screening and model merging, the strategic application of surrogate models is not merely a convenience but a fundamental enabler of modern computational science and engineering.

Surrogate models, also known as metamodels or emulators, are approximation mathematical models used when an outcome of interest cannot be easily measured or computed directly. They are engineering methods designed to mimic the behavior of computationally expensive simulations or physical experiments as closely as possible while being significantly cheaper to evaluate [20]. In the context of expensive black-box optimization, where objective function evaluations may take hours, days, or substantial financial resources, surrogate models provide a practical pathway for design optimization, design space exploration, sensitivity analysis, and "what-if" analysis that would otherwise be impossible due to the computational burden [20].

The fundamental challenge in surrogate modeling is generating a model that is as accurate as possible using as few expensive simulations or experiments as possible [20]. This process typically involves three iterative steps: sample selection through design of experiments (DOE), construction of the surrogate model with optimized parameters, and appraisal of the surrogate's accuracy [20]. The accuracy of the resulting surrogate depends critically on both the number and location of samples in the design space and the choice of surrogate modeling technique appropriate for the problem characteristics [21].

Within the broader thesis on the role of surrogate models in expensive black-box optimization research, understanding the core surrogate families is essential. These models form the foundational approximation capabilities that enable optimization algorithms to navigate complex design spaces with limited function evaluations. Recent benchmarking studies have demonstrated that the best surrogate-based optimization algorithm depends significantly on the evaluation time and available computation budget, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate surrogate model families for specific problem contexts [2].

Technical Profiles of Primary Surrogate Families

Polynomial Response Surfaces

Polynomial Regression (PR) represents one of the classical and most straightforward approaches to surrogate modeling. This method employs polynomial functions of varying degrees to approximate the relationship between input variables and the response output. The primary advantage of PR lies in its computational efficiency and simplicity in both implementation and interpretation. According to comparative studies on surrogate models for design optimization, PR demonstrates superior efficiency in model generation compared to more complex alternatives [21].

The mathematical formulation of a polynomial response surface typically begins with a first or second-order polynomial, though higher orders are possible. A second-order model with k variables takes the form: y = β₀ + Σβᵢxᵢ + Σβᵢᵢxᵢ² + Σβᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε, where y represents the predicted response, xᵢ denotes the input variables, β coefficients are determined through regression techniques, and ε signifies the error term. The coefficients are typically estimated using ordinary least squares regression, which provides a closed-form solution to the parameter estimation problem.

Polynomial response surfaces are particularly valuable for problems with smooth, low-dimensional response surfaces and when computational budget is severely constrained. They also excel in sensitivity analysis, as they readily provide information about the main effects of design variables and their interaction effects. Research comparing surrogate techniques has confirmed that PR is better suited than kriging-based models for determining which design variable has the greatest impact on response [21]. However, PR models struggle with highly nonlinear, irregular, or discontinuous response surfaces, where they may require impractically high polynomial degrees to achieve acceptable accuracy, leading to overfitting and numerical instability.

Radial Basis Functions (RBF)

Radial Basis Function models constitute a flexible class of surrogate models that approximate the target function through a linear combination of basis functions that depend only on the radial distance from specific center points. The general form of an RBF model is f(x) = Σwᵢφ(||x - cᵢ||), where φ represents the radial basis function, cᵢ denotes the center points, wᵢ represents the weights, and ||x - cᵢ|| indicates the Euclidean distance between the prediction point and centers. Common choices for the basis function include Gaussian (φ(r) = e^(-εr²)), multiquadric (φ(r) = √(1+(εr)²)), inverse multiquadric (φ(r) = 1/√(1+(εr)²)), and thin plate spline (φ(r) = r²ln(r)) functions.

The key advantage of RBF models lies in their ability to approximate arbitrary functions without requiring explicit knowledge of the underlying function form. They are considered "mesh-free" methods, meaning they do not require structured input data, making them particularly suitable for problems with irregularly spaced sample points. RBF models generally provide more accurate approximations for highly nonlinear functions compared to polynomial response surfaces, though they may be outperformed by kriging for certain function types.

Implementation of RBF models requires selection of an appropriate basis function and determination of the shape parameter ε where applicable. The weights wᵢ are typically determined by solving a linear system that ensures exact interpolation at the training points (for interpolating models) or through regularized approaches (for approximating models when noise is present). The Surrogates.jl package in the Julia programming language provides implementation tools for radial basis methods alongside other surrogate modeling techniques [20].

Kriging

Kriging, also known as Gaussian Process Regression, is a powerful geostatistical interpolation method that has gained widespread adoption in surrogate modeling for expensive black-box functions. Kriging provides not only predictions at unknown points but also an estimate of prediction uncertainty, making it particularly valuable for adaptive sampling strategies in optimization. The kriging model consists of two components: a global trend function (often a constant or low-order polynomial) and a departure term representing local variations: f(x) = μ(x) + Z(x), where μ(x) represents the global trend and Z(x) is a stationary Gaussian process with zero mean and covariance Cov(Z(xᵢ), Z(xⱼ)) = σ²R(θ; xᵢ, xⱼ), where R is the correlation function with parameters θ.

A distinctive strength of kriging is its statistical foundation, which provides a measure of uncertainty at any point in the design space. This uncertainty quantification enables the implementation of efficient infill criteria such as Expected Improvement (EI) or Lower Confidence Bound (LCB) that balance exploration (sampling in uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling near promising observed points). Comparative analyses have concluded that kriging-based models are superior to polynomial regression for assessing max-min search results due to their ability to predict a broader range of objective values [21].

The implementation of kriging requires selection of an appropriate correlation function (typically Gaussian, Exponential, or Matern) and estimation of the correlation parameters θ through maximum likelihood estimation or cross-validation. This parameter estimation can be computationally demanding for large datasets, though recent advancements have addressed this limitation through techniques such as kriging by partial-least squares reduction [20]. Kriging has demonstrated particular effectiveness in benchmarking studies on expensive black-box optimization problems, where its uncertainty quantification capabilities enable more efficient global search [2].

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Support Vector Regression is a machine learning approach adapted from Support Vector Machines for regression tasks. SVR seeks to find a function that deviates at most by ε from the observed training data while maintaining maximum flatness. The fundamental principle involves mapping input data to a high-dimensional feature space using kernel functions, then performing linear regression in this transformed space. The mathematical formulation of SVR can be expressed as f(x) = Σ(αᵢ - αᵢ*)K(xᵢ, x) + b, where αᵢ and αᵢ* are Lagrange multipliers, b is the bias term, and K(xᵢ, x) represents the kernel function.

The ε-insensitive loss function used in SVR provides inherent robustness to outliers, as errors smaller than ε are not penalized. This characteristic makes SVR particularly suitable for problems with noisy data or potential outliers. Additionally, the kernel trick enables SVR to handle highly nonlinear relationships without explicitly transforming the input data, with common kernel choices including linear, polynomial, radial basis function, and sigmoid kernels.

SVR implementation requires careful selection of three hyperparameters: the regularization parameter C (controlling the trade-off between model complexity and training error), the insensitivity parameter ε (defining the margin within which errors are ignored), and any kernel-specific parameters (such as γ for the RBF kernel). These parameters are typically optimized through cross-validation techniques. While SVR may be computationally intensive during training for very large datasets, it generally offers strong generalization performance and robustness for moderate-sized experimental designs commonly encountered in expensive black-box optimization problems.

Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative performance of surrogate models across key metrics

| Performance Metric | Polynomial Regression | Radial Basis Functions | Kriging | Support Vector Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Speed | Fastest [21] | Moderate | Slow | Moderate to Slow |

| Prediction Speed | Fastest | Fast | Fast | Fast |

| Accuracy for Smooth Functions | High for low-order polynomials | Moderate to High | High | Moderate to High |

| Accuracy for Nonlinear Functions | Low unless high degree | High | High | High |

| Noise Handling | Poor (requires regularization) | Moderate | Good (nugget effect) | Excellent (ε-insensitive loss) |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Limited (prediction intervals) | Limited | Excellent (posterior distribution) | Limited |

| Theoretical Foundation | Least-squares regression | Numerical analysis | Gaussian processes | Statistical learning theory |

Table 2: Implementation considerations and typical use cases

| Aspect | Polynomial Regression | Radial Basis Functions | Kriging | Support Vector Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size Requirements | Small (≥ k+1 for linear) | Moderate to Large | Small to Moderate | Moderate to Large |

| Dimensionality Handling | Curse of dimensionality | Curse of dimensionality | Curse of dimensionality | Feature selection possible |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Best-Suited Applications | Preliminary analysis, sensitivity studies [21] | Scattered data approximation | Global optimization [2] | Noisy data, high-dimensional problems |

| Software Availability | All major packages | Surrogates.jl [20] | SMT, Surrogates.jl [20] | Various ML libraries |

The comparative analysis reveals distinct strengths and limitations for each surrogate family. Polynomial regression demonstrates superior efficiency in model generation, making it particularly valuable when computational resources for surrogate construction are limited [21]. However, its limitations in handling complex nonlinearities restrict its application to relatively smooth, low-dimensional problems.

Kriging-based models excel in scenarios requiring global approximation accuracy and uncertainty quantification, which explains their prevalence in expensive black-box optimization frameworks [2] [21]. The ability to predict a broader range of objective values makes kriging particularly suitable for max-min search operations in optimization contexts [21]. However, this capability comes at the cost of increased computational requirements during model training.

Radial Basis Functions offer a balanced approach with good accuracy for nonlinear functions and straightforward implementation. Support Vector Regression provides distinct advantages for problems with noisy evaluations or potential outliers, thanks to its ε-insensitive loss function. Recent benchmarking studies indicate that the optimal choice of surrogate algorithm depends significantly on the evaluation time of the objective and the available computational budget, rather than simply whether the problem is continuous or discrete [2].

Implementation Methodologies

Experimental Protocol for Surrogate-Assisted Optimization

The effective implementation of surrogate models in expensive black-box optimization follows a structured methodology that balances exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization process. The following workflow outlines the standard experimental protocol for surrogate-assisted optimization:

Diagram 1: Workflow for surrogate-assisted optimization

The process begins with initial sample selection through Design of Experiments (DOE). The selection of appropriate design points significantly impacts surrogate model performance, with both the number and location of design points affecting model accuracy [21]. For initial sampling, space-filling designs such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or orthogonal arrays are commonly employed to maximize information gain from limited expensive evaluations.

Following initial sampling, surrogate model construction proceeds with careful attention to model selection and parameter tuning. As highlighted in benchmarking studies, the best-performing surrogate algorithm depends on both the evaluation time of the objective and the available computational budget [2]. Model hyperparameters are typically optimized through cross-validation techniques, though in Bayesian approaches such as kriging, maximum likelihood estimation is commonly employed.

The optimization phase exploits the cheap-to-evaluate surrogate to identify promising candidate points for subsequent expensive evaluation. The search process may employ various techniques, from mathematical programming for convex problems to evolutionary algorithms or other global search methods for nonconvex problems. Critical to this process is the infill criterion, which determines which points warrant expensive evaluation. For kriging, Expected Improvement is a popular criterion, while for other surrogates, probability of improvement or lower confidence bounds may be employed.

The sequential process of model updating and refinement continues until convergence criteria are met or the evaluation budget is exhausted. Convergence may be determined by improvement thresholds, maximum iterations, or stabilization of the best solution found. Throughout this process, the balance between exploration (sampling in uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known good solutions) is paramount to optimization efficiency [22].

Model Validation and Error Assessment

Rigorous validation protocols are essential for ensuring surrogate model reliability in optimization contexts. The following procedures represent established methodologies for surrogate model validation:

Cross-Validation: Particularly k-fold cross-validation, where the available data is partitioned into k subsets, with k-1 sets used for training and the remaining set for validation. This process is repeated k times with different validation sets, and the error metrics are averaged across all folds. For expensive black-box problems where data is scarce, leave-one-out cross-validation (where k equals the number of samples) is often employed.

Hold-Out Validation: When sufficient data is available, a hold-out set (typically 20-30% of the data) is reserved before model training and used exclusively for error assessment. This approach provides an unbiased estimate of generalization error but reduces the data available for model construction.

Predictive Error Metrics: Quantitative assessment employs various error metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for overall accuracy, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for robustness to outliers, and R² (coefficient of determination) for proportion of variance explained. For deterministic computer experiments without random error, the PRESS statistic (prediction sum of squares) and associated R²_prediction metric are particularly valuable.

Visual Diagnostic Tools: Graphical analyses including scatter plots of predicted versus actual values, residual plots, and slice plots provide crucial insights into model behavior, revealing patterns such as systematic bias, heteroscedasticity, or regions of poor fit that may not be apparent from numerical metrics alone.

Implementation of these validation techniques ensures that surrogate models provide reliable approximations before their deployment in optimization loops, preventing misleading optimization results due to poor surrogate accuracy.

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Surrogate models have found particularly valuable applications in pharmaceutical research and development, where complex biological systems and expensive experimentation create ideal conditions for surrogate-assisted approaches. The pharmaceutical sector increasingly depends on advanced process modeling techniques to streamline drug development and manufacturing workflows, with surrogate-based optimization emerging as a practical and efficient solution for managing computational complexity [13].

In drug development applications, surrogate models enable researchers to navigate complex design spaces with limited experimental iterations, substantially reducing development timelines and costs. For API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) manufacturing process optimization, studies have demonstrated that surrogate-based approaches can achieve significant improvements in key metrics such as yield and process mass intensity while maintaining high purity standards [13]. Single-objective optimization frameworks have achieved 1.72% improvement in yield and 7.27% improvement in process mass intensity, while multi-objective frameworks have managed 3.63% enhancement in yield while maintaining high purity levels [13].

The use of surrogate endpoints represents another critical application of surrogate modeling concepts in pharmaceutical development. Regulatory agencies such as the FDA acknowledge surrogate endpoints as "markers, such as laboratory measurement, radiographic image, physical sign, or other measure, that is not itself a direct measurement of clinical benefit" but that can predict clinical benefit [23]. Examples include reduction in amyloid beta plaques for Alzheimer's disease, skeletal muscle dystrophin for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and serum insulin-like growth factor-I for acromegaly [23].

Table 3: Exemplary surrogate endpoints in pharmaceutical development

| Disease Area | Surrogate Endpoint | Clinical Correlation | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Reduction in amyloid beta plaques | Reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit | Accelerated approval [23] |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | Skeletal muscle dystrophin | Reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit | Accelerated approval [23] |

| Cystic Fibrosis | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) | Known to predict clinical benefit | Traditional approval [23] |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | Estimated glomerular filtration rate | Known to predict clinical benefit | Traditional approval [23] |

Beyond development phases, surrogate models also play crucial roles in pharmaceutical manufacturing optimization. A novel surrogate-based optimization framework for pharmaceutical process systems has demonstrated effectiveness in optimizing complex API manufacturing processes, highlighting particular value in multi-objective optimization contexts where Pareto fronts reveal trade-offs between competing objectives such as yield, purity, and sustainability [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential computational tools for surrogate modeling research

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Modeling Toolbox (SMT) [20] | Surrogate model construction and validation | Extensive surrogate model library, derivatives support, gradient-enhanced modeling | Python package |

| Surrogates.jl [20] | Surrogate modeling implementation | Radial basis methods, kriging, random forests | Julia package |

| SAMBO Optimization [20] | Sequential optimization | Tree-based models, Gaussian process models, arbitrary model support | Python library |

| EXPObench [2] | Benchmarking library | Standardized expensive optimization problems, algorithm comparison | Public benchmark library |

| IEMSO Framework [22] | Explainability metrics | Model-agnostic explainability, transparency assessment | Methodology framework |

The computational tools outlined in Table 4 represent essential resources for researchers implementing surrogate modeling approaches. The Surrogate Modeling Toolbox (SMT) deserves particular emphasis as it provides a comprehensive collection of surrogate modeling methods, sampling techniques, and benchmarking functions in a Python environment [20]. Its distinctive focus on derivatives, including training derivatives for gradient-enhanced modeling and prediction derivatives, differentiates it from other surrogate modeling libraries [20].

For benchmarking studies, EXPObench provides standardized expensive optimization problems that enable meaningful comparison of different surrogate algorithms [2]. This benchmarking library addresses the critical need for standardization in evaluating surrogate algorithms on real-life, expensive, black-box objective functions, which has traditionally made it difficult to draw substantive conclusions about algorithmic performance and provide evidence-based recommendations for method selection [2].

The emerging area of explainability in surrogate optimization is addressed by the Inclusive Explainability Metrics for Surrogate Optimization (IEMSO) framework, which offers model-agnostic metrics to enhance transparency, trustworthiness, and explainability of surrogate optimization approaches [22]. This comprehensive set of metrics covers four primary categories: Sampling Core Metrics, Batch Properties Metrics, Optimization Process Metrics, and Feature Importance, providing both intermediate and post-hoc explanations to practitioners throughout the optimization process [22].

The four primary surrogate families—Polynomial Response Surfaces, Radial Basis Functions, Kriging, and Support Vector Regression—each offer distinct advantages and limitations for expensive black-box optimization problems. Polynomial models provide computational efficiency and sensitivity analysis capabilities, RBF offers flexible interpolation for irregularly spaced data, Kriging delivers uncertainty quantification for adaptive sampling, and SVR provides robustness to noisy data. The optimal selection depends critically on problem characteristics including computational budget, evaluation time, nonlinearity, noise presence, and dimensional complexity.

Within pharmaceutical applications, surrogate modeling approaches have demonstrated significant practical impact from drug development through manufacturing optimization. The ability to approximate complex system behaviors while drastically reducing computational or experimental burden makes surrogate-assisted approaches particularly valuable in resource-constrained research environments. Future research directions will likely focus on enhancing model explainability, developing more effective hybrid approaches, and creating standardized benchmarking frameworks to facilitate appropriate method selection across diverse application domains. As surrogate modeling continues to evolve, its role in enabling efficient optimization of expensive black-box functions across scientific and engineering disciplines appears increasingly indispensable.

In computationally expensive domains such as drug development and materials science, optimizing black-box functions presents a fundamental challenge: balancing the accuracy of a model with the high cost of evaluating it. Surrogate models have emerged as a powerful solution, acting as computationally cheap proxies for expensive simulations or physical experiments. This whitepaper explores the central role of surrogate models in managing the accuracy-evaluation cost trade-off. We detail the experimental protocols and methodologies that underpin their success, provide a quantitative analysis of their performance, and visualize the key workflows. Framed within broader thesis research on black-box optimization, this guide equips researchers and scientists with the practical knowledge to implement these techniques effectively, thereby accelerating discovery while managing computational resources.

In many scientific and engineering fields, particularly in drug development and materials science, researchers aim to optimize complex systems—such as a drug's efficacy or an alloy's strength—where the relationship between input parameters and the output objective function is unknown, complex, and expensive to evaluate. This is the realm of expensive black-box optimization (BBO) [24]. Each evaluation of this black-box function could represent a days-long physical experiment, a computationally intensive quantum simulation, or a costly clinical trial.

The primary goal is to find the optimal input parameters that maximize or minimize this expensive function with the fewest possible evaluations. This process is inherently constrained by a fundamental trade-off: the need for high model accuracy, which often requires more data and complex models, versus the prohibitive cost of obtaining that data through function evaluations. Surrogate models, also known as metamodels, address this trade-off by learning an approximation of the expensive black-box function from a limited set of initial evaluations. This model can then be used to inexpensively screen a vast space of possibilities, guiding the optimization process toward promising regions without the constant need for costly evaluations [24] [25] [26].

Technical Foundations: Surrogate Models in Optimization

A surrogate model is a mathematical model trained to approximate the input-output relationship of an expensive black-box function. The core workflow involves a loop of exploration and exploitation, where the surrogate's predictions are used to decide which points to evaluate next in the original expensive function.

Key Surrogate Model Types

Different surrogate models offer varying balances of expressive power, computational overhead, and data efficiency.

- Gaussian Process Regression (GPR): Also known as Kriging, GPR is a cornerstone of Bayesian optimization. It provides not just a prediction but also a measure of uncertainty (variance) at any point in the input space. This allows for a principled balance between exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known promising areas [26].

- Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS): MARS is a non-parametric regression technique that models complex nonlinear relationships by partitioning the input space and fitting simple splines in each region. Its parsimonious nature makes it robust and less prone to overfitting. Enhanced versions like Tree-Knot MARS (TK-MARS) have been specifically tailored for surrogate optimization, improving its performance in high-dimensional spaces [24].

- Radial Basis Functions (RBF): RBF models use a weighted sum of basis functions that depend only on the distance from a center point. They are flexible interpolators commonly used in surrogate optimization algorithms [24].

- Neural Networks (NNs): With their high capacity for modeling complex, high-dimensional relationships, NNs are increasingly used as surrogates, particularly in scenarios with large amounts of training data [26].

The Optimization Workflow

The integration of a surrogate into an optimization framework follows a sequential, iterative process, visually summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram: Surrogate Model Optimization Workflow

This workflow highlights the closed-loop process where data from expensive evaluations continuously refines the surrogate model, which in turn guides the selection of future evaluation points.

Quantitative Analysis of Cost-Accuracy Trade-offs

The choice of surrogate model and optimization strategy directly impacts the efficiency and success of a campaign. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from various studies, highlighting the performance of different approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Surrogate Models and Optimization Algorithms

| Model / Algorithm | Context / Domain | Key Performance Findings | Dimensionality Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Knot MARS (TK-MARS) [24] | General Global Optimization | Outperforms original MARS within a surrogate optimization algorithm; successfully detects important input variables. | Effective in high-dimensional spaces with variable screening. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) with EI [26] | Materials Design (e.g., HEA) | A common baseline; performance can degrade as search space dimensionality increases, potentially missing promising regions. | Struggles in high-dimensional spaces (D ≥ 6). |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) [26] | Materials Design (e.g., HEA) | Consistently outperforms traditional Bayesian Optimization (BO) in high-dimensional cases (D ≥ 6) through more dispersed sampling and better landscape learning. | Particularly promising for high-dimensional spaces (D ≥ 6). |

| BO/RL Hybrid [26] | Materials Design (e.g., HEA) | Creates a synergistic effect, leveraging BO's early-stage exploration strength with RL's later-stage adaptive self-learning. | Robust across different dimensionalities. |

| LLMs/MLLMs as Judges [27] | Multimodal Search Relevance | Model performance is use-case dependent; no single model consistently outperforms all others. Inclusion of vision in small models can hinder performance. | Highlights context-dependency of cost-accuracy trade-offs. |

A critical finding from recent research is that no single model is universally superior. The performance is often use-case dependent [27]. For instance, in high-dimensional materials design, Reinforcement Learning (RL) demonstrates a statistically significant advantage (p < 0.01) over traditional Bayesian optimization, whereas in other contexts like multimodal search, the optimal model varies significantly with the application [27] [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure the successful application of surrogate-assisted optimization, researchers must follow rigorous experimental protocols. The following sections detail two foundational methodologies.

Virtual Patient Generation in Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP)

In drug development, QSP models simulate disease progression and drug effects. Generating Virtual Patients (VPs)—parameter sets that yield biologically plausible behaviors—is a classic expensive BBO problem. The traditional method of random sampling is inefficient, with a vast majority of model runs typically not resulting in valid VPs [25]. A surrogate-assisted workflow dramatically improves efficiency:

Stage 1: Generate Training Data Set

- Step 1.1: Choose Parameters: Select a subset of sensitive model parameters to vary, informed by sensitivity analysis and knowledge of biological variability. For example, a psoriasis QSP model might select 5-20 parameters related to cell proliferation and cytokine clearance [25].

- Step 1.2: Sample Parameters: Sample the chosen parameters using defined distributions (e.g., uniform fold-change from a reference value).

- Step 1.3: Simulate QSP Model: Run the full, expensive QSP model for each sampled parameter set under relevant simulated protocols (e.g., untreated disease, treatment response).

Stage 2: Generate Surrogate Models

- Train a suite of machine learning models (e.g., using Regression Learner App [25]) where the inputs are the sampled parameters and the outputs are the constrained model responses (e.g., cell population counts at a final timepoint). Each constrained output variable gets its own surrogate model.

Stage 3: Pre-screen and Validate VPs

- Pre-screen Phase: Use the trained surrogate models to rapidly predict outcomes for millions of new parameter sets. Only parameter sets where the surrogate predictions pass all biological constraints are accepted as candidate VPs.

- Validation Phase: Run the full QSP model for the pre-screened candidate VPs to confirm their validity. This workflow ensures that the "overwhelming majority of parameter combinations preâ€vetted using the surrogate models result in valid VPs" when tested in the original model [25].

Dataset Cleansing via Black-Box Optimization