Surrogate-Based Optimization in Process Systems Engineering: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of surrogate-based optimization (SBO) techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and biomedical engineering.

Surrogate-Based Optimization in Process Systems Engineering: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of surrogate-based optimization (SBO) techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and biomedical engineering. It covers the foundational principles of SBO as a solution for computationally expensive black-box problems common in process systems engineering. The scope extends to a detailed review of state-of-the-art methodologies, including Bayesian Optimization, deep learning surrogates, and ensemble methods, with specific applications in pharmaceutical process systems and prosthetic device design. The content further addresses critical challenges such as data scarcity and model reliability, offers comparative performance assessments of various algorithms, and concludes with future directions for integrating these powerful optimization techniques into biomedical and clinical research to accelerate innovation.

What is Surrogate-Based Optimization? Core Principles and Relevance to Biomedical Engineering

Surrogate-Based Optimization (SBO) has emerged as a powerful methodology for solving optimization problems where the objective function and/or constraints are computationally expensive to evaluate, poorly understood, or treated as a black-box system [1]. In process systems engineering, such challenges frequently arise when dealing with complex physics-based simulations (e.g., computational fluid dynamics), laboratory experiments, or large-scale process models [1]. The core principle of SBO is to approximate these expensive costly black-box functions with computationally cheap surrogate models–often called metamodels–which are then used to guide the optimization search efficiently [1] [2].

This approach is particularly valuable in data-driven optimization contexts, where derivative information is unavailable or unreliable, a category often referred to as derivative-free optimization (DFO) [1]. By constructing accurate surrogates from a limited set of strategically sampled data points, SBO algorithms can find optimal solutions with far fewer evaluations of the true expensive function, making them indispensable for modern engineering research and drug development where simulations or experiments are time-consuming and resource-intensive [3].

Mathematical Foundation and Key Algorithms

Problem Formulation

A generic unconstrained optimization problem can be formulated as shown in Equation 1, where the goal is to minimize an objective function ( f(\mathbf{x}) ) that depends on design variables ( \mathbf{x} ) within a feasible region ( \mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{n_{x}} ) [1].

[ \min{\mathbf{x}} f(\mathbf{x}) \quad \text{subject to} \quad \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{n{x}} ]

In real-world applications, this formulation often extends to include constraints, making the problem even more challenging. The objective function ( f ) is frequently treated as a black box, meaning its analytical form is unknown, and we can only observe its output for given inputs [1]. Evaluating this function is typically computationally expensive, creating the need for efficient optimization strategies like SBO.

The SBO Workflow

The standard SBO workflow involves these key iterative steps:

- Initial Sampling: Select an initial set of points ( \mathbf{x}1, \mathbf{x}2, ..., \mathbf{x}_n ) using a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach and evaluate the expensive true function ( f ) at these points [2].

- Surrogate Model Construction: Fit a surrogate model ( \hat{f} ) to the collected data ( {(\mathbf{x}i, f(\mathbf{x}i))} ).

- Infill Criterion: Use the surrogate to propose new promising candidate point(s) ( \mathbf{x}_{new} ) by optimizing an acquisition function.

- Model Update: Evaluate ( f(\mathbf{x}_{new}) ), add the new data to the training set, and update the surrogate model.

- Termination: Repeat steps 3-4 until a convergence criterion or evaluation budget is met [1] [2].

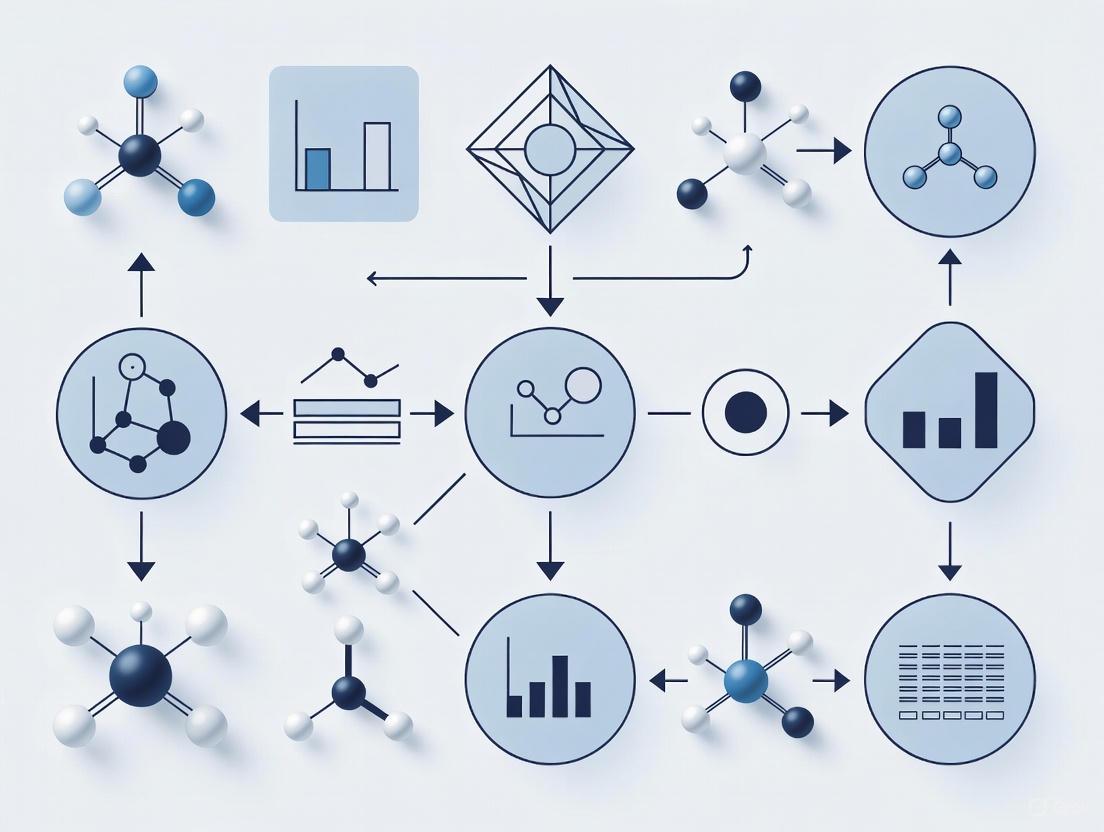

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Multiple surrogate modeling and optimization strategies have been developed, each with strengths suited to different problem types. The table below summarizes key algorithms and their primary characteristics.

Table 1: Key Surrogate-Based Optimization Algorithms and Characteristics

| Algorithm | Full Name | Surrogate Type | Key Features | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BO [1] | Bayesian Optimization | Gaussian Process (GP) | Provides uncertainty estimates; balances exploration vs. exploitation | Expensive black-box functions; hyperparameter tuning |

| TuRBO [1] | Trust Region Bayesian Optimization | Multiple local GPs | Uses trust regions for scalable high-dimensional optimization | High-dimensional problems |

| COBYQA [1] | Constrained Optimization by Quadratic Approximations | Quadratic approximation | Specifically designed for constrained problems | Optimization with explicit constraints |

| ENTMOOT [1] | Ensemble Tree Model Optimization Tool | Gradient-boosted trees | Handles mixed variable types well | Problems with categorical/continuous variables |

| SNOBFIT [1] | Stable Noisy Optimization by Branch and Fit | Local linear models | Robust to noisy function evaluations | Noisy experimental data |

Applications in Process Systems and Pharmaceutical Engineering

SBO finds extensive applications across process systems engineering and pharmaceutical research, where first-principles models are complex and simulations require significant computational resources.

Process Systems Engineering Case Studies

In chemical engineering, SBO enables efficient optimization of process systems under various constraints. Case studies demonstrate its effectiveness for reactor control optimization and reactor design under uncertainty, where traditional derivative-based methods struggle due to the computational cost of high-fidelity simulations [1]. These applications often feature stochastic elements and high-dimensional parameter spaces, making SBO particularly valuable [1].

Another significant application is system architecture optimization (SAO) for complex engineered systems like jet engines [2]. These problems present challenges such as mixed-discrete design variables (e.g., choosing component types and continuous parameters), multiple objectives, and hidden constraints where simulations fail for certain design configurations [2]. SBO successfully navigates these complex design spaces while managing evaluation failures that can affect up to 50% of proposed points in some applications [2].

Pharmaceutical and Energy System Applications

While the search results focus on process and energy systems, the methodologies translate directly to pharmaceutical applications. For instance, SBO can optimize drug formulation parameters, bioreactor operation conditions, or pharmaceutical crystallization processes where experiments are costly and time-consuming.

In energy systems, a recent study applied data-driven surrogate optimization to deploy heterogeneous multi-energy storage at a building cluster level [4]. This approach addressed the challenge of optimally selecting and sizing different energy storage technologies (batteries, thermal storage) for individual buildings with highly diversified energy use patterns [4]. The method utilized genetic programming symbolic regression to develop accurate surrogate models and an iterative optimization with automated screening to handle the mixed combinatorial-continuous optimization problem [4]. This demonstrates how SBO can manage problems with both configuration selection and parameter sizing decisions.

Essential Protocols for SBO Implementation

Protocol 1: Handling Hidden Constraints in SAO

System architecture optimization often encounters hidden constraints–regions of the design space where function evaluations fail due to non-converging solvers or infeasible physics [2]. This protocol outlines a strategy for managing these constraints using Bayesian Optimization with a Probability of Viability (PoV) prediction.

Table 2: Reagents and Computational Tools for Hidden Constraint Management

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Discrete Gaussian Process (MD-GP) [2] | Models objective function while handling both continuous and discrete variables | Essential for architectural decisions with both parameter types |

| Random Forest Classifier (RFC) [2] | Predicts failure regions and calculates Probability of Viability (PoV) | Can identify patterns leading to evaluation failures |

| Probability of Viability (PoV) Threshold [2] | Screening criterion for proposed infill points | Avoids evaluating points likely to violate hidden constraints |

| Ensemble Infill Strategy [2] | Generates multiple candidate points per iteration | Improves exploration while managing parallel evaluations |

Procedure:

- Initialization: Generate an initial Design of Experiments (DoE) with ( n_{doe} ) points, ensuring they are spatially distributed across the design space [2].

- Viability Screening: Evaluate all initial points and identify which evaluations succeed (viable) and which fail.

- Model Building:

- Train a mixed-discrete GP on viable points to model the objective function.

- Train a classification model (e.g., Random Forest) to predict PoV based on all evaluated points.

- Infill Point Selection:

- Generate candidate points by optimizing the acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement).

- Apply the PoV threshold to filter out candidates with high failure probability.

- Select the final infill points satisfying the PoV criterion.

- Iteration: Evaluate new points, update both models, and repeat until convergence.

The following diagram illustrates the hidden constraint handling strategy:

Protocol 2: Data-Driven Surrogate Optimization for Multi-Energy Storage Deployment

This protocol outlines a method for solving high-dimensional, nonlinear optimization problems using symbolic regression for surrogate modeling, particularly applicable to resource allocation problems with multiple technology options [4].

Procedure:

- Simulation Platform Development: Create a high-fidelity simulation model of the system (e.g., building cluster with multi-energy storage) to generate training data [4].

- Training Data Generation:

- Define input variables (e.g., storage configuration choices, sizing parameters).

- Run simulations across a wide range of input combinations.

- Record corresponding performance metrics (e.g., energy costs, demand response performance).

- Surrogate Model Development:

- Apply genetic programming symbolic regression to develop accurate, explicit surrogate models.

- Validate model accuracy against holdout simulation data.

- Iterative Optimization with Screening:

- Implement an optimization algorithm that uses the surrogate models.

- Include automated option screening to efficiently navigate combinatorial choices.

- Iteratively refine solutions while focusing computational resources on promising configurations.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of SBO Algorithms on Expensive Black-Box Functions

| Algorithm | Problem Type | Key Performance Insight | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [3] | General expensive black-box | Performance depends on evaluation time and available budget | Highly data-efficient for very expensive functions |

| Linear Surrogate SBO [5] | Airfoil self-noise minimization | Effective under small initial dataset constraints | Found design with 103.38 dB performance |

| CVAE Generative Approach [5] | Airfoil self-noise minimization | 77.2% of generated designs outperformed SBO baseline | Provides diverse portfolio of high-performing candidates |

| Symbolic Regression SBO [4] | Multi-energy storage deployment | Reduced energy bills by 8%-181% vs. baseline cases | Handled high dimensionality effectively |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Software and Visualization

Key Software Tools and Libraries

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for SBO Implementation

| Tool/Library | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SBArchOpt [2] | Bayesian Optimization for system architecture problems | Handles mixed-discrete, hierarchical variables and hidden constraints |

| IDAES Surrogate Tools [6] | Surrogate model visualization and validation | Creates scatter, parity, and residual plots for model assessment |

| EXPObench [3] | Benchmarking library for expensive optimization problems | Standardized testing of SBO algorithms on real-world problems |

| ALAMO/PySMO [6] | Surrogate model training | Automated surrogate model generation from data |

| RS-51324 | RS-51324, CAS:62780-15-8, MF:C11H11Cl2N3O2, MW:288.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| S-2474 | S-2474|COX-2/5-LOX Inhibitor|CAS 158089-95-3 |

Surrogate Model Visualization and Validation

Effective SBO requires rigorous validation of surrogate model quality. The IDAES toolkit provides specialized plotting functions for this purpose [6]:

- Surrogate Scatter Plots: Visualize the relationship between individual inputs and outputs, comparing surrogate predictions against validation data.

- Parity Plots: Compare surrogate predictions against true function values across the validation set; ideal models show points closely aligned to the y=x line.

- Residual Plots: Analyze prediction errors (residuals) to identify systematic biases or regions where the surrogate performs poorly.

Implementation Code:

The Critical Need for SBO in Process Systems Engineering and Drug Development

Optimization is a cornerstone of modern engineering and science, impacting cost-effectiveness, resource utilization, and product quality across industries [7]. In complex chemical and pharmaceutical systems, traditional optimization methods that rely on analytical expressions and derivative information often fail when applied to problems involving computationally expensive simulators or experimental data collection [1]. This challenge has catalyzed the emergence of surrogate-based optimization (SBO) as a powerful methodology that combines machine learning with optimization algorithms to navigate expensive black-box problems efficiently [8].

SBO techniques approximate expensive functions through surrogate models trained on available data, dramatically reducing the number of costly evaluations required to find optimal solutions [1] [8]. For process systems engineering and drug development, where experiments or high-fidelity simulations can be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, SBO provides a critical pathway to accelerate innovation while conserving resources [9]. This application note examines the transformative potential of SBO methodologies across these domains, providing structured protocols and frameworks for implementation.

Fundamental Principles of Surrogate-Based Optimization

Theoretical Foundation

SBO addresses optimization problems formulated as: $$\min{\mathbf{x}} f(\mathbf{x}), \quad \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{n{x}}$$ where $f$ represents an expensive-to-evaluate black-box function, and analytical expressions or derivative information are unavailable [1]. The core SBO approach replaces the expensive function $f(x)$ with a surrogate model $g(x)$ constructed from available data points using machine learning techniques [8].

The surrogate construction follows: $$\min{g} \sum{i=1}^{n} L(g(xi) - f(xi))$$ where $L$ represents a loss function between the surrogate predictions and actual function values [8]. This surrogate is then utilized within an acquisition function to determine promising new evaluation points: $$\arg \max_{x \in X} \alpha(g(x))$$ where $\alpha$ balances exploration against exploitation [8].

Algorithm Taxonomy

Table: Classification of Major SBO Algorithms

| Algorithm Category | Representative Methods | Key Characteristics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Approaches | Bayesian Optimization (BO), TuRBO [7] | Uses probabilistic models; handles uncertainty effectively | High-dimensional problems with limited evaluations [7] |

| Local Approximation | COBYLA, COBYQA [7] | Constructs linear or quadratic local models | Low-dimensional constrained optimization [7] |

| Tree-Based Methods | ENTMOOT [7] | Uses decision trees as surrogates | Problems with structured input spaces [7] |

| Radial Basis Functions | DYCORS, SRBFStrategy [7] | Uses RBF networks as surrogates | Continuous black-box optimization [7] |

| Multimodal Frameworks | AMSEEAS [10] | Combines multiple surrogate models adaptively | Problems with complex response surfaces [10] |

SBO in Process Systems Engineering

Chemical Process Optimization

In chemical engineering, SBO enables efficient optimization of processes where first-principles models are computationally demanding or where processes are guided purely by collected data [1]. Applications range from reactor control optimization to resource utilization improvement and sustainability metrics enhancement [7]. The digitalization of chemical engineering through smart measuring devices, process analytical technology, and the Industrial Internet of Things has further amplified the need for data-driven optimization approaches [1].

Sustainable Process Design

SBO contributes significantly to sustainable engineering through three interconnected dimensions:

- SBO for Sustainability: Application to sustainable engineering problems aligned with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [8]

- Sustainability of SBO: Minimizing computational resources and energy consumption of optimization algorithms [8]

- Sustainability with SBO: Reducing expensive function evaluations of computationally intensive simulators [8]

Recent frameworks have demonstrated simultaneous improvements in multiple process metrics, including yield enhancement and process mass intensity reduction in pharmaceutical manufacturing [9].

SBO in Pharmaceutical Development

Drug Development Pipeline Optimization

The pharmaceutical sector increasingly depends on advanced process modeling to streamline drug development and manufacturing workflows [9]. SBO provides a practical solution for optimizing these complex systems while respecting stringent quality constraints.

A notable example is SPARC's development of SBO-154, an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for advanced solid tumors [11] [12] [13]. The successful completion of IND-enabling preclinical studies with favorable results demonstrates the potential of systematic optimization approaches in accelerating therapeutic development [13].

Pharmaceutical Process Optimization

Recent research has established novel SBO frameworks specifically designed for pharmaceutical process systems [9]. These frameworks integrate multiple software tools into unified systems for surrogate-based optimization of complex manufacturing processes, with demonstrated improvements in key metrics including:

- Yield improvement up to 3.63% in multi-objective optimization frameworks [9]

- Process Mass Intensity improvement of 7.27% in single-objective optimization [9]

- Maintenance of high purity levels while enhancing yield [9]

Integrated SBO Framework Protocol

Geometric Feature Knowledge-Driven Optimization

The aerodynamic supervised autoencoder (ASAE) framework provides a transferable methodology for leveraging domain knowledge in SBO [14]. This approach extracts features correlated with performance metrics to guide the optimization process more efficiently.

Diagram 1: Geometric feature knowledge-driven SBO workflow. This framework improves optimization efficiency by approximately twofold while achieving superior performance [14].

Adaptive Multi-Surrogate Protocol

The Adaptive Multi-Surrogate Enhanced Evolutionary Annealing Simplex (AMSEEAS) algorithm provides a robust methodology for time-expensive environmental and process optimization problems [10].

Experimental Protocol: AMSEEAS Implementation

Initialization Phase

- Define optimization problem: decision variables, objectives, constraints

- Select ensemble of surrogate models (Kriging, Radial Basis Functions, Neural Networks)

- Initialize population using Latin Hypercube Sampling

- Evaluate initial samples using expensive simulator

Iterative Optimization Phase

- Step 1: Train all surrogate models on current dataset

- Step 2: Calculate selection probabilities for each model based on recent performance

- Step 3: Select active surrogate using roulette-wheel selection

- Step 4: Generate candidate solutions using Evolutionary Annealing Simplex method

- Step 5: Evaluate promising candidates using expensive simulator

- Step 6: Update dataset and model performance metrics

Termination Phase

- Check convergence criteria (maximum evaluations, stability of solution)

- Return optimal solution and performance history

This multimodel approach ensures flexibility against problems with varying geometries and complex response surfaces, consistently outperforming single-surrogate methods in benchmarking studies [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for SBO Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in SBO Workflow | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Models | Kriging, Radial Basis Functions, Neural Networks, Decision Trees [7] | Approximate expensive objective functions | ENTMOOT (tree-based) [7], SRBF (radial basis) [7] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Bayesian Optimization, COBYLA, TuRBO [7] | Navigate surrogate surfaces to find optima | High-dimensional reactor control [7], Pharmaceutical process optimization [9] |

| Expensive Simulators | CFD, HEC-RAS, Pharmaceutical process models [14] [10] [9] | Provide ground truth data for surrogate training | Aerodynamic design [14], Hydraulic systems [10], Drug manufacturing [9] |

| Feature Learning | Aerodynamic Supervised Autoencoder (ASAE) [14] | Extract performance-correlated features from design space | Airfoil and wing optimization [14] |

| Multi-Model Frameworks | AMSEEAS [10] | Adaptive surrogate selection for complex problems | Time-expensive environmental problems [10] |

Performance Assessment Protocol

Benchmarking Methodology

Comprehensive SBO performance assessment requires standardized evaluation across multiple dimensions:

- Test Functions: Apply algorithms to diverse mathematical functions with known optima [7]

- Constraint Handling: Evaluate performance on both constrained and unconstrained problems [7]

- Dimensionality Scaling: Test scalability from low-dimensional to high-dimensional problems [7]

- Real-World Case Studies: Validate using chemical engineering and pharmaceutical applications [7] [9]

Quantitative Metrics

Table: SBO Performance Assessment Metrics

| Performance Dimension | Quantitative Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Efficiency | Number of expensive function evaluations to reach target objective | Lower values indicate superior performance |

| Solution Quality | Percentage improvement in objective function vs. baseline | Higher values indicate superior optimization |

| Computational Sustainability | Energy consumption and computational resources required | Lower environmental impact of optimization process |

| Robustness | Performance consistency across diverse problem types | Higher reliability across applications |

Surrogate-based optimization represents a paradigm shift in addressing complex, expensive optimization challenges across process systems engineering and pharmaceutical development. By leveraging machine learning to construct efficient approximations of costly simulations and experiments, SBO enables accelerated innovation while conserving computational and experimental resources. The structured frameworks and protocols presented in this application note provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing SBO across diverse domains, from sustainable process design to accelerated drug development. As SBO methodologies continue to evolve, their integration into industrial practice promises to enhance both the efficiency and sustainability of technological advancement across critical engineering and healthcare sectors.

Surrogate-based optimization has emerged as a pivotal technique in process systems engineering, particularly for tackling costly black-box problems where derivative information is unavailable or the evaluation of the underlying function is computationally expensive [7] [1]. This approach involves constructing approximate models, or surrogates, of complex systems based on data collected from a limited number of simulations or physical experiments. These surrogates are then used to drive optimization, significantly reducing computational burden [15]. The adoption of these techniques is accelerating the digital transformation in fields like pharmaceutical manufacturing, where they streamline drug development and manufacturing workflows, leading to substantial improvements in operational efficiency, cost reduction, and adherence to stringent product quality standards [15] [9]. This application note details the core advantages of surrogate-based optimization—computational efficiency, sensitivity analysis, and enhanced system insight—and provides detailed protocols for their implementation, framed within the context of process systems engineering research.

Computational Efficiency in Surrogate-Based Optimization

Computational efficiency is the most immediate advantage of surrogate-based optimization. In chemical and pharmaceutical engineering, high-fidelity models—such as those involving computational fluid dynamics, quantum mechanical calculations, or integrated process flowsheets—can be prohibitively time-consuming to evaluate, making direct optimization infeasible [1]. Surrogate models address this by acting as fast-to-evaluate proxies for these expensive simulations.

Mechanism of Efficiency Gains

The efficiency is achieved through a two-phase process. First, a surrogate model is trained on a carefully selected dataset of input-output pairs from the expensive high-fidelity model or physical process. Subsequently, the optimization algorithm operates on the surrogate model, which can be evaluated orders of magnitude faster than the original system [15] [16]. This decoupling allows for extensive exploration and exploitation of the design space without the constant computational cost of running the full simulation.

Quantitative Evidence from Case Studies

Empirical studies across process engineering confirm these efficiency gains. In a pharmaceutical manufacturing case study, a surrogate-based optimization framework was applied to an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturing flowsheet. The results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate that the framework successfully identified process conditions that led to measurable improvements in key performance indicators, all while avoiding the computational cost of repeatedly running the full process model [15] [9].

Table 1: Performance Improvements in a Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Case Study Using Surrogate-Based Optimization

| Optimization Type | Key Performance Indicator | Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Objective | Yield | +1.72% | [15] |

| Single-Objective | Process Mass Intensity | +7.27% | [15] |

| Multi-Objective | Yield | +3.63% (while maintaining high purity) | [15] [9] |

Another case study involving the optimization of a wet granulation process using an autoencoder-based inverse design reported computational times averaging under 4 seconds for the optimization run, highlighting the dramatic speed-up achievable with these methods [16].

Protocol: Implementing Surrogate-Based Optimization for Process Design

This protocol outlines the steps for applying surrogate-based optimization to a chemical or pharmaceutical process, such as the API manufacturing flowsheet referenced in the case study [15].

Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Step 1: Define Optimization Objectives and Constraints. Clearly articulate the goal (e.g., maximize yield, minimize energy consumption) and identify all process constraints (e.g., purity must exceed a certain threshold, operating pressure must remain within a safe window).

- Step 2: Select Input Variables. Identify the key decision variables (e.g., temperature, catalyst concentration, flow rates) and their feasible ranges.

- Step 3: Generate Initial Training Data. Use a space-filling design of experiments (DoE), such as Latin Hypercube Sampling, to select an initial set of points within the input variable space. The number of initial points should be a multiple (typically 5-10x) of the number of input variables.

- Step 4: Run High-Fidelity Simulations/Experiments. Execute the expensive, high-fidelity process model or physical experiment at each of the points specified by the DoE. Record the corresponding output metrics (e.g., yield, purity, cost).

Surrogate Model Construction and Validation

- Step 5: Choose a Surrogate Model Type. Select an appropriate machine learning model based on the problem characteristics. Common choices include:

- Gaussian Process Regression (Kriging): Excellent for uncertainty quantification, used in Bayesian Optimization [7] [1].

- Gradient-Boosted Trees (e.g., via ENTMOOT): Handles complex, non-linear relationships and naturally manages input constraints [7] [17].

- Random Forests: Robust and provides feature importance metrics, as demonstrated in the mandibular movement study [18].

- Neural Networks: Suitable for very high-dimensional and non-linear problems [17] [16].

- Step 6: Train the Model. Use the input-output data collected in Steps 3-4 to train the selected surrogate model.

- Step 7: Validate Model Accuracy. Assess the predictive performance of the surrogate on a separate, held-out test dataset using metrics like R² or Mean Squared Error. If accuracy is insufficient, return to Step 3 to augment the training data or to Step 5 to select a different model.

Optimization and Iteration

- Step 8: Perform Optimization over the Surrogate. Use a suitable optimization algorithm (e.g., evolutionary algorithms, branch-and-bound for tree surrogates, or dedicated solvers like Gurobi with OMLT/Pyomo) to find the input values that optimize the objective function, subject to the defined constraints [17].

- Step 9: Validate and Update. Run the high-fidelity model at the optimal point identified by the surrogate. To improve the model, add this new data point to the training set and retrain the surrogate (iterative updating). Repeat until convergence or a computational budget is reached.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this iterative process.

Enabling Sensitivity Analysis and System Insight

Beyond finding an optimum, surrogate-based optimization provides a powerful pathway for sensitivity analysis and deeper system insight. The surrogate model itself becomes a source of knowledge about the process.

Quantitative Sensitivity Analysis

Once trained, the surrogate model can be interrogated to determine how sensitive the output is to changes in each input variable. For tree-based models like those used in ENTMOOT or Random Forests, techniques like Gini importance or permutation importance can rank variables by their influence on the objective function [18] [17]. In the study using mandibular movement signals, feature importance analysis from a Random Forest model revealed that "event duration, lower percentiles, central tendency, and the trend of MM amplitude were the most important determinants" for classifying hypopnea events [18]. This quantitative insight guides engineers toward the most critical process parameters.

Visualizing Trade-offs and the Design Space

In multi-objective optimization, surrogates are used to construct Pareto fronts, which visually represent the trade-offs between competing objectives [15]. For instance, a Pareto front can show how much product purity must be sacrificed to achieve a higher yield. This allows researchers and decision-makers to visually navigate the design space and select an optimal operating point that balances multiple criteria, such as yield, purity, and sustainability [15]. Advanced methods like autoencoder-based inverse design further enhance insight by performing dimensionality reduction, which allows for the visualization of complex, high-dimensional design spaces in two or three dimensions, thereby improving process understanding [16].

Protocol: Conducting Global Sensitivity Analysis with a Trained Surrogate

This protocol describes how to use a trained surrogate model to perform a global sensitivity analysis, identifying the most influential input variables in your process.

Model-Based Sensitivity Indices

- Step 1: Trained Surrogate Model. Begin with a fully trained and validated surrogate model from Section 3.2.

- Step 2: Generate Large Sample Set. Create a large number of random input vectors (e.g., 10,000+) uniformly distributed across the entire feasible input space.

- Step 3: Run Predictions. Use the surrogate model to predict the output for each of these input vectors.

- Step 4: Calculate Sensitivity Indices.

- For Tree-Based Models (Random Forest, ENTMOOT): Use built-in feature importance metrics. These typically measure the total decrease in node impurity (e.g., Gini or Mean Squared Error) weighted by the number of samples reaching that node, averaged over all trees.

- For Other Models (Gaussian Processes, Neural Networks): Calculate Sobol indices. This involves computing the variance of the conditional expectation of the output. The first-order Sobol index (Si) measures the main effect of each input variable, while the total-order index (STi) includes interaction effects.

Interpretation and Visualization

- Step 5: Rank Variables. Rank all input variables from highest to lowest based on their calculated importance index (e.g., Gini importance or total-order Sobol index).

- Step 6: Create a Bar Chart. Plot the normalized importance scores in a bar chart for clear visual comparison.

- Step 7: Analyze and Report. The variables with the highest scores have the greatest influence on the process output. This knowledge allows researchers to focus experimental and control efforts on these key parameters.

The diagram below maps the logical flow of this analytical process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of surrogate-based optimization requires a suite of computational tools and models. The table below lists essential "research reagents" for scientists in this field.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Software for Surrogate-Based Optimization Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENTMOOT | Software Tool | Multi-objective black-box optimization using gradient-boosted trees (Gurobi as solver). | [7] [17] |

| OMLT | Python Package | Represents machine learning models (NNs, trees) within the Pyomo optimization environment. | [17] |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Algorithm/ Framework | Efficient global optimization for expensive black-box functions, using Gaussian processes. | [7] [1] |

| TuRBO | Algorithm | State-of-the-art variant of BO that scales to high-dimensional problems. | [7] |

| Random Forest | Algorithm/ Model | Robust surrogate model that also provides feature importance for sensitivity analysis. | [18] |

| Autoencoder | AI Model | Used for inverse design and dimensionality reduction to visualize complex design spaces. | [16] |

| High-Fidelity Process Model | Digital Reagent | The complex, computationally expensive simulation of the physical process being optimized. | [15] [16] |

| Saroaspidin B | Saroaspidin B, CAS:112663-68-0, MF:C25H32O8, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Saroaspidin C | Saroaspidin C, CAS:112663-70-4, MF:C26H34O8, MW:474.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Surrogate-based optimization represents a paradigm shift in how complex engineering systems are designed and improved. By leveraging computationally efficient surrogate models, researchers can solve previously intractable optimization problems, as evidenced by successful applications in pharmaceutical manufacturing that led to tangible improvements in yield and process intensity [15] [9]. Furthermore, the analytical power of these models extends beyond finding a single optimum; they enable rigorous sensitivity analysis to identify key process drivers and provide visual tools like Pareto fronts to understand critical trade-offs between competing objectives [15] [18]. As the field progresses, the integration of advanced AI, such as autoencoders for inverse design [16], and robust software frameworks, like OMLT and ENTMOOT [17], will continue to deepen system insight and accelerate innovation across process systems engineering.

Optimization is fundamental to chemical engineering and pharmaceutical development, directly impacting cost-effectiveness, resource utilization, and product quality [7] [19]. The methods for achieving optimal decisions have undergone a significant evolution, shifting from traditional model-based approaches to modern data-driven paradigms. This transition has been particularly impactful in process systems engineering and drug development, where the ability to optimize complex, expensive-to-evaluate systems without explicit analytical models provides a distinct advantage [19] [1].

Traditional optimization relied on algebraic or knowledge-based expressions that could be optimized using derivative information [1]. However, the rise of digitalization, smart sensors, and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has generated abundant process data, creating a need for algorithms that can leverage this information directly [19] [1]. This gave rise to data-driven optimization, also known as derivative-free, zeroth-order, or black-box optimization [1]. In this context, "black-box" refers to systems where the objective and constraint functions are only available as outputs from experiments or complex simulations, making derivative information unavailable or unreliable [19]. This review traces this methodological evolution, framed within the context of surrogate-based optimization for process systems engineering, and provides application notes and protocols for drug development researchers.

The Paradigm Shift: From Traditional to Data-Driven Methods

Traditional Model-Based Optimization

The traditional decision-making approach in chemical engineering leverages first-principles models—algebraic or differential equations derived from physical laws—that are optimized using derivative information from their analytical expressions [1]. This approach requires a deep mechanistic understanding of the system to develop accurate, differentiable models.

Key Limitations:

- Model Development Cost: Creating accurate first-principles models is time-consuming and requires expert knowledge.

- Computational Expense: Solving complex models involving rigorous differential-algebraic equations can be computationally prohibitive.

- Inflexibility: These models struggle to adapt to systems with unknown mechanisms or high stochasticity.

The Rise of Data-Driven and Surrogate-Based Optimization

Data-driven optimization bypasses the need for explicit first-principles models. It treats the system as a "black box," using input-output data to guide the search for an optimum [19] [20]. A dominant subset of these methods is surrogate-based optimization (also known as model-based derivative-free optimization). These methods iteratively construct and optimize approximate models of the expensive black-box function [7] [1].

The catalyst for this shift includes:

- Data Abundance: Proliferation of data from sensors and process analytical technology [19] [1].

- Problem Complexity: Increased need to optimize systems where models are unknown, proprietary, or too expensive to run frequently [19].

- Algorithmic Advances: Development of robust algorithms for building and optimizing surrogates.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Data-Driven Optimization Paradigms

| Feature | Traditional Optimization | Data-Driven (Surrogate-Based) Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Core Input | Analytical model expressions | Input-output data from experiments or simulations |

| Derivative Use | Uses analytical gradients | Derivative-free; uses only function evaluations |

| Model Basis | First-principles (white-box) | Surrogate models (black-box or grey-box) |

| Computational Focus | Solving the model | Minimizing number of expensive function evaluations |

| Ideal Application | Well-understood, differentiable systems | Expensive black-box problems with unknown mechanisms |

Key Algorithmic Families in Data-Driven Optimization

Derivative-free optimization (DFO) algorithms can be categorized into three main families [19] [1].

Direct Search Methods

These methods directly compare function values without constructing a surrogate model. Examples include the Nelder-Mead (simplex) algorithm and pattern search. They are often simple to implement but may require more function evaluations for convergence [19] [1].

Finite-Difference Methods

These methods approximate gradients using function evaluations, enabling the use of gradient-based optimization algorithms. Examples include finite-difference BFGS and Adam. They bridge direct and model-based methods [1].

Model-Based (Surrogate-Based) Methods

This is the most prominent family for expensive black-box problems. It involves:

- Design of Experiments: Selecting points in the design space to run the expensive evaluation.

- Surrogate Model Construction: Fitting a computationally cheap model to the collected data.

- Surrogate Optimization: Optimizing the surrogate to propose new candidate points.

- Model Update: Re-evaluating the expensive function at promising points and updating the surrogate [7] [19].

Table 2: Key Surrogate-Based Optimization Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Description | Strengths | Common Use Cases in Pharma/PSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Uses Gaussian processes to model the objective and an acquisition function to guide sampling [7] [1]. | Handles noise naturally; provides uncertainty estimates. | Hyperparameter tuning, stochastic simulation optimization [7] [21]. |

| Trust-Region Methods (e.g., Py-BOBYQA, CUATRO) | Constructs local polynomial models within a trust region that is adaptively updated [19]. | Strong theoretical convergence guarantees. | Flowsheet optimization, real-time optimization [19]. |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) Methods | Uses RBFs as global surrogates (e.g., DYCORS, SRBF) [7]. | Effective for global exploration. | Process design, reactor optimization [7] [19]. |

| Tree-Based Methods (e.g., ENTMOOT) | Uses ensemble trees (like random forests) as surrogates [7]. | Handles categorical variables and non-smooth functions. | Material and process design with mixed variable types. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and historical evolution of these key optimization methodologies.

Application in Process Systems Engineering and Drug Development

Data-driven optimization addresses critical challenges in process systems engineering and Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), enabling more efficient and predictive design [22].

Pharmaceutical Process Design and Optimization

In drug development, surrogate-based optimization is used to streamline manufacturing process design. A key application is optimizing tablet manufacturing processes to control Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), such as dissolution behavior [23].

Protocol 1: Surrogate Modeling for Tablet Dissolution Behavior Prediction

Objective: To develop a surrogate model for predicting dissolution behavior in tablet manufacturing, identifying critical process parameters for efficient process design [23].

Workflow Summary: The diagram below outlines the surrogate modeling workflow for linking manufacturing inputs to dissolution profiles.

Materials and Reagents:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): e.g., Paracetamol (200 mg per tablet) [23].

- Excipients: Lactose monohydrate (70 mg), Microcrystalline cellulose (30 mg) [23].

- Simulation Software: gPROMS for mechanistic flowsheet modeling [23].

- Programming Environment: Python with Scikit-learn for Random Forest regression [23].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Input Space: Identify variable input parameters

P(e.g., material properties, granulation liquid-to-solid ratio, compression force) and their feasible ranges [23]. - Generate Data via Mechanistic Modeling: Execute the mechanistic flowsheet model in gPROMS with different combinations of

Pto generate corresponding dissolution profilesD_mech(t). This is the expensive "black-box" function evaluation [23]. - Parameterize Output: Fit the raw dissolution profile

D_mech(t)to a Weibull model (or other suitable function) to extract key parameters (e.g., shape and scale factors). This converts a time-series profile into a manageable set of numbers [23]. - Train Surrogate Model: Using the input parameters

Pas features and the fitted Weibull parameters as targets, train a Random Forest regression model. This model learns the mappingP -> Weibull Parameters[23]. - Validate Model: Compare the dissolution profile

D_surr(t)predicted by the surrogate model against profiles generated by the mechanistic model for a validation dataset to ensure accuracy [23]. - Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis: Use the trained, fast-to-evaluate surrogate model to run extensive sensitivity analyses or optimization routines to identify critical process parameters and optimal operating conditions [23].

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) Manufacturing

A unified surrogate-based optimization framework can drive substantial improvements in API manufacturing metrics like yield, purity, and sustainability [15].

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Optimization of an API Manufacturing Process

Objective: To optimize an API manufacturing flowsheet for competing objectives (e.g., maximize yield and purity, minimize environmental impact) using surrogate-based methods [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- Dynamic System Model: A high-fidelity dynamic model of the API manufacturing process (e.g., in gPROMS or Aspen Plus) [15].

- Optimization Framework: Software tools for surrogate modeling (e.g., Python, MATLAB) and multi-objective optimization (e.g., NSGA-II).

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Objectives and Decision Variables: Identify key performance indicators (e.g., Yield, Process Mass Intensity) and the process variables to be optimized [15].

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Use a space-filling DoE (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to define a set of decision variable combinations to simulate.

- Run High-Fidelity Simulations: Execute the dynamic process model for each combination from the DoE to generate the corresponding objective function values.

- Construct Surrogate Models: Train individual surrogate models for each objective using the simulation data.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Apply a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm to the surrogates to generate a Pareto front, which reveals the trade-offs between competing objectives [15].

- Decision Making: Select the optimal operating point from the Pareto front based on project priorities. Validate the selected point with a final high-fidelity simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for conducting data-driven optimization studies in process systems engineering and drug development.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Driven Optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Simulators(gPROMS, Aspen Plus) | Software | Serves as the "expensive black-box" to generate high-fidelity input-output data for training surrogates [23]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression | Statistical Model | A core surrogate model in Bayesian Optimization; provides predictions with uncertainty estimates [7] [21]. |

| Random Forest / Decision Trees | Machine Learning Model | A surrogate model that handles non-smooth functions and mixed variable types effectively [7] [23]. |

| Trust-Region Algorithm | Optimization Framework | Manages the trade-off between global exploration and local exploitation by dynamically adjusting the region where the surrogate is trusted [19]. |

| Radial Basis Functions (RBF) | Mathematical Function | Used to construct flexible global surrogate models that interpolate scattered data points [7] [19]. |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling | Algorithm | An experimental design method to generate efficient, space-filling samples from the input parameter space for initial surrogate training [15]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Acquisition Function | In Bayesian Optimization, guides the selection of the next sample point by balancing prediction mean and uncertainty [7]. |

| SB-204900 | (2R,3S)-N-Methyl-3-phenyl-N-[(Z)-2-phenylvinyl]-2-oxiranecarboxamide | Research-use (2R,3S)-N-Methyl-3-phenyl-N-[(Z)-2-phenylvinyl]-2-oxiranecarboxamide. Study its role in synthesizing bioactive molecules. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| SB 216763 | SB 216763, CAS:280744-09-4, MF:C19H12Cl2N2O2, MW:371.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evolution from traditional to data-driven optimization represents a fundamental shift in how complex systems are designed and controlled. Surrogate-based optimization techniques have emerged as a powerful methodology for tackling expensive black-box problems prevalent in process systems engineering and pharmaceutical development. By leveraging input-output data to construct computationally efficient surrogate models, these methods enable the optimization of systems where first-principles models are difficult, expensive, or impossible to develop and use directly. As demonstrated in applications ranging from tablet manufacturing to API process intensification, this data-driven paradigm shortens development timelines, reduces costs, and enhances the robustness of process design, ultimately accelerating the delivery of innovative therapies to patients.

In process systems engineering, optimization serves as a cornerstone for enhancing cost-effectiveness, resource utilization, product quality, and sustainability metrics [7] [1]. The rise of digitalization, smart measuring devices, and sensor technologies has intensified the need for sophisticated data-driven optimization approaches [1]. This document establishes foundational protocols for properly structuring optimization problems, with particular emphasis on formulation within surrogate-based optimization frameworks where derivative information may be unavailable or computationally expensive to obtain [7] [1]. A well-formulated optimization problem precisely defines the decision levers (variables), the performance metrics (objectives), and the operational limits (constraints) that govern the system under investigation.

Table 1: Core Components of an Optimization Problem

| Component | Definition | Role in Optimization | Examples in Process Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Variables | Quantities controlled by the optimizer to find the optimal solution [24] [25]. | Define the search space of possible solutions. | Reactor temperature, catalyst concentration, flow rates [1]. |

| Objective Function | A function to be minimized or maximized [26] [24] [25]. | Defines the performance criterion for evaluating solutions. | Minimize production cost, maximize product yield, minimize energy consumption [7]. |

| Constraints | Conditions that must be satisfied for a solution to be feasible [26] [24]. | Delineate the boundaries of acceptable operating conditions. | Maximum pressure limits, minimum purity requirements, safety thresholds [26]. |

Fundamental Concepts and Mathematical Formulation

Decision Variables

Decision variables (DVs) represent the independent parameters that the optimizer adjusts to find the optimum. In chemical engineering, these often pertain to geometric, operational, or physical aspects of a system [24]. DVs can be continuous (able to take any value within a range, such as temperature) or discrete (limited to specific values or types, such as the number of reactors) [24]. A critical practice is to begin with the smallest number of DVs that still captures the essence of the problem, thereby reducing complexity and improving the likelihood of convergence to a meaningful solution [24]. Furthermore, linearly dependent variables that control the same physical characteristic should be avoided to prevent an ill-posed problem with infinite equivalent solutions [24].

Objective Function

The objective function, typically denoted by ( Z ) or ( f ), is a real-valued function that quantifies the goal of the optimization, whether it is to minimize cost or maximize efficiency [26] [25]. In a general mathematical sense, an optimization problem is formulated as shown in Equation 1 [24]:

[ \begin{align} \text{Minimize} \quad & f_{\text{obj}}(\mathbf{x}) \ \text{With respect to} \quad & \mathbf{x} \ \text{Subject to} \quad & g_{\text{lb}} \leq g(\mathbf{x}) \leq g_{\text{ub}} \ \quad & h(\mathbf{x}) = h_{\text{eq}} \end{align} ]

Here, ( \mathbf{x} ) is the vector of decision variables, ( f_{\text{obj}} ) is the objective function, ( g(\mathbf{x}) ) represents inequality constraints with lower and upper bounds, and ( h(\mathbf{x}) ) represents equality constraints [26] [24]. It is standard to frame problems as minimizations; a maximization problem can be converted by applying a negative sign to the objective function (e.g., maximize profit is equivalent to minimize negative profit) [24].

Constraints

Constraints define the feasible region by setting conditions that the decision variables must obey. They can be classified as:

- Inequality Constraints: Specify that a function of the variables must be greater than or less than a specified value (e.g., ( hj(\mathbf{x}) \geq dj )) [26].

- Equality Constraints: Require that a function of the variables must exactly equal a specified value (e.g., ( gi(\mathbf{x}) = ci )) [26].

A design satisfying all constraints is feasible, while one violating any constraint is infeasible [24]. Unlike variable bounds, which are strictly respected, optimizers may temporarily violate constraints during the search process to navigate the design space [24].

Surrogate-Based Optimization in Process Systems

The Role of Surrogates in Data-Driven Optimization

Surrogate-based optimization, a class of model-based derivative-free methods, is particularly valuable when optimizing costly black-box functions [7] [1]. These scenarios arise when the objective function or constraints are determined by expensive experiments (e.g., in-vitro chemical experiments) or high-fidelity simulations (e.g., computational fluid dynamics) where derivatives are unavailable or unreliable [1]. The core idea is to construct a computationally efficient surrogate model (or meta-model) that approximates the expensive true function based on a limited set of evaluated data points [7] [1]. The optimizer then primarily works with this surrogate to navigate the design space efficiently.

Two prominent perspectives for developing these models are:

- Surrogate-Led Approach: The data-driven model takes precedence in guiding the optimization search.

- Mathematical Programming-Led Approach: The surrogate is tightly integrated into a traditional optimization framework, with the algorithm dictating the search trajectory [27].

A critical consideration in surrogate-based optimization is the verification problem—ensuring that the optimum found using the surrogate corresponds to the optimum of the underlying high-fidelity "truth" model [27].

Formulation for Black-Box Problems

In derivative-free optimization, the generic unconstrained problem is formulated as [1]:

[ \begin{align} \min_{\mathbf{x}} \quad & f(\mathbf{x}) \ \text{s.t.} \quad & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{n_{x}} \end{align} ]

However, unlike in traditional optimization, there is no analytical expression for ( f(\mathbf{x}) ) to compute derivatives [1]. The algorithm must strategically explore the space, balancing the need to gather information about the function (exploration) with the goal of using existing information to find the optimum (exploitation) [1]. Termination is often based on a maximum number of function evaluations or runtime, as ensuring convergence to a true optimum is challenging when the function itself is unknown [1].

Table 2: Key Considerations for Surrogate-Based Optimization Formulation

| Aspect | Consideration | Implication for Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Function Evaluation Cost | Evaluations are computationally expensive or time-consuming [1]. | The optimization algorithm must be sample-efficient. The number of function evaluations is a key performance metric. |

| Noise | Deterministic models can be corrupted by computational noise, making numerical derivatives unreliable [1]. | Algorithms must be robust to noise. Smoothing or stochastic modeling techniques may be required. |

| Constraints | Constraints may also be black-box functions [7]. | Constraint handling methods (e.g., penalty functions, feasible region modeling) must be integrated into the surrogate framework. |

| Dimensionality | Problems can be high-dimensional (e.g., reactor control) [7] [1]. | The choice of surrogate model (e.g., Random Forests, Bayesian Optimization) must scale effectively with the number of variables. |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

A Protocol for Problem Formulation

- Define the Goal: Precisely state the engineering goal in qualitative terms. Example: "Minimize the energy consumption of a distillation column while maintaining product purity above 99.5%."

- Identify and Bound Decision Variables: List all parameters under the optimizer's control. Categorize as continuous or discrete. Establish realistic physical bounds for each variable (e.g., ( 300 \text{K} \leq T \leq 500 \text{K} )). Start with a minimal set to simplify initial problem solving [24].

- Formalize the Objective Function: Translate the qualitative goal into a single, quantifiable scalar function. For multiple objectives, employ techniques like Pareto optimization or weighted sum methods [28].

- Specify All Constraints: Document all equality and inequality constraints derived from physical limits, safety regulations, product specifications, and operational requirements [26] [24].

- Select the Modeling Paradigm: Determine if the problem can be modeled with analytical expressions (suitable for gradient-based optimizers [24]) or requires a black-box/surrogate-based approach due to expensive or noisy function evaluations [7] [1].

- Iterate and Refine: Begin with a simplified problem and achieve convergence. Subsequently, analyze the results, check for physical meaningfulness, and gradually increase the problem's complexity by adding variables or constraints, re-optimizing at each stage [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Surrogate-Based Optimization

| Tool / Algorithm | Category | Primary Function | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [7] [1] | Surrogate-Based / Model-Based DFO | Uses probabilistic models to balance exploration and exploitation. | Global optimization of expensive black-box functions. |

| TuRBO [7] | Surrogate-Based / Model-Based DFO | A state-of-the-art BO method that uses trust regions. | High-dimensional, stochastic optimization problems. |

| CONLABy Linear Approximation) [7] | Surrogate-Based / Model-Based DFO | Constructs linear approximations for derivative-free optimization. | Low-dimensional constrained problems. |

| ENTMOOT [7] | Surrogate-Based / Model-Based DFO | Uses ensemble tree models (e.g., GBDT) as surrogates. | Problems where tree-based models provide high accuracy. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization [1] | Direct DFO / Metaheuristic | A population-based method inspired by social behavior. | Global search for non-convex or noisy problems. |

| Nelder-Mead Simplex [1] | Direct DFO | A pattern search method that operates on a simplex geometry. | Local optimization of low-dimensional problems without derivatives. |

| SB-218078 | SB-218078, CAS:135897-06-2, MF:C24H15N3O3, MW:393.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SB-273005 | SB-273005, CAS:205678-31-5, MF:C22H24F3N3O4, MW:451.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Formulating an optimization problem with well-defined decision variables, constraints, and objectives is a foundational step in applying surrogate-based techniques to process systems engineering. This formulation dictates the effectiveness and efficiency of the optimization algorithm, especially when dealing with costly black-box functions prevalent in chemical engineering and drug development. By adhering to structured protocols—starting simple, carefully selecting variables and constraints, and iteratively refining the problem—researchers can navigate complex design spaces to discover optimal, feasible, and meaningful solutions. The integration of robust surrogate modeling techniques ensures that these data-driven optimization strategies are both computationally tractable and scientifically sound, enabling advancements in automated control and decision-making for complex processes.

A Deep Dive into SBO Algorithms and Their Real-World Biomedical Applications

In the realm of process systems engineering, the optimization of complex systems is often hampered by computationally expensive simulations. Surrogate modeling, also known as metamodeling, has emerged as a powerful technique that uses simplified models to mimic the behavior of these complex, computationally intensive simulations [29]. By acting as efficient proxies, surrogate models enable faster evaluations and make large-scale optimization feasible across various engineering domains, including pharmaceutical manufacturing, materials design, and medical device development [15] [30] [29]. The fundamental premise of surrogate-based optimization is to replace the expensive "black-box" function evaluations with inexpensive approximations, thereby dramatically reducing computational costs while maintaining acceptable accuracy [1] [31].

The adoption of surrogate modeling is particularly valuable in process systems engineering where competing objectives need to be balanced, such as minimizing production costs while maximizing product purity in pharmaceutical manufacturing [15] [29]. These models provide engineers with the capability to perform extensive sensitivity analyses, explore design spaces thoroughly, and identify optimal trade-offs between conflicting objectives—tasks that would be prohibitively expensive using full-scale simulations [29]. As the pharmaceutical sector increasingly depends on advanced process modeling techniques to streamline drug development and manufacturing workflows, surrogate-based optimisation has emerged as a practical and efficient solution for driving substantial improvements in operational efficiency, cost reduction, and adherence to stringent product quality standards [15].

Taxonomy of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

Surrogate models can be broadly classified into several distinct categories based on their mathematical foundations, implementation complexity, and application domains. The taxonomy presented below encompasses the spectrum from traditional polynomial approaches to advanced machine learning techniques.

Table 1: Classification of Primary Surrogate Modeling Techniques

| Model Type | Mathematical Foundation | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Response Surfaces (PRS) | Low-order polynomial equations [29] | Simplicity, interpretability, low computational cost [29] | Stress-strain prediction, system dynamics approximation [29] |

| Kriging/Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | Gaussian process theory, spatial correlation [29] | Uncertainty quantification, handles nonlinearity [32] [29] | Stent geometry optimization, structural mechanics [29] |

| Radial Basis Functions (RBF) | Basis functions dependent on distance from centers [31] | Good interpolation properties, handles irregular data [31] | High-dimensional expensive optimization [31] |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) | Orthonormal polynomial series [33] | Global sensitivity analysis, uncertainty quantification [33] | Atmospheric chemistry models, inverse modeling [33] |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Layers of interconnected nodes inspired by biological brains [29] [33] | Captures complex nonlinear relationships, handles large datasets [29] | Fluid flow optimization, biological response prediction [29] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Statistical learning theory, kernel methods [30] | Effective with limited data, handles high-dimensional spaces [30] | Microstructural optimization of materials [30] |

Traditional and Machine Learning-Based Surrogates

Beyond the fundamental classification, surrogate models can be further categorized as either traditional mathematical approximations or modern machine learning techniques. Traditional methods include Polynomial Response Surfaces, Kriging, and Polynomial Chaos Expansion, which are typically grounded in well-established mathematical principles and often provide greater interpretability [29] [33]. In contrast, machine learning-based surrogates such as Artificial Neural Networks and Support Vector Machines excel at capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional spaces but often require larger training datasets and offer less interpretability [29].

Another important distinction lies in their implementation strategies: static surrogates are constructed prior to the optimization process, often using simplified physics or relaxed internal tolerances, while dynamic surrogates are built and updated iteratively as the optimization progresses [31]. Research has also explored hybrid approaches, such as combining static surrogates as input for quadratic models within optimization algorithms like Mesh Adaptive Direct Search (MADS) [31].

Comparative Analysis of Surrogate Models

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of different surrogate modeling techniques is crucial for selecting the appropriate approach for specific applications in process systems engineering.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

| Model Type | Data Efficiency | Computational Cost | Handling Nonlinearity | Uncertainty Quantification | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Response Surfaces | High [29] | Low [29] | Low to moderate [29] | No | High [29] |

| Kriging/GPR | Medium [29] | Medium to high [29] | High [29] | Yes [32] [29] | Medium |

| Radial Basis Functions | Medium | Medium | Medium to high [31] | Limited | Medium |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion | Medium [33] | Medium [33] | Medium to high [33] | Yes [33] | Medium to high |

| Artificial Neural Networks | Low (requires more data) [29] | High (training phase) [29] | Very high [29] | Limited | Low [29] |

| Support Vector Machines | Medium to high [30] | Medium to high | High [30] | Limited | Low to medium |

Guidelines for Model Selection

Selecting the appropriate surrogate model depends on multiple factors, including the characteristics of the underlying process, available computational resources, and the specific objectives of the optimization study. For early-stage design exploration or problems with relatively smooth response surfaces, Polynomial Response Surfaces remain a practical choice due to their simplicity and low computational requirements [29]. When dealing with highly nonlinear systems with limited data and a need for uncertainty quantification, Kriging models are particularly advantageous [29]. For problems involving large datasets and complex, nonlinear relationships, Artificial Neural Networks often provide superior performance despite their higher computational demands and reduced interpretability [29].

In practical applications, researchers often employ ensemble approaches that combine multiple surrogate types to leverage their respective strengths [31]. Additionally, the choice of surrogate model may evolve throughout an optimization campaign, starting with simpler models for initial exploration and progressing to more sophisticated techniques as the region of interest becomes more defined.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Frameworks

General Workflow for Surrogate-Assisted Optimization

The implementation of surrogate-based optimization follows a systematic workflow that integrates data generation, model training, and iterative refinement. The following diagram illustrates this generalized framework:

This workflow visualization captures the iterative nature of surrogate-based optimization, highlighting the critical stages of data generation, model training, and convergence checking before proceeding to final optimization.

Protocol 1: Surrogate Model Development for Pharmaceutical Process Optimization

Objective: To develop and validate surrogate models for optimizing Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturing processes with multiple competing objectives (yield, purity, Process Mass Intensity) [15].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Process Simulation Software: High-fidelity model of the API manufacturing process (e.g., dynamic system model) [15]

- Sampling Tool: Design of Experiments implementation with Latin Hypercube Sampling capability [32] [34]

- Surrogate Modeling Framework: Software with multiple surrogate modeling techniques (Gaussian Process Regression, Polynomial Chaos Expansion, Neural Networks) [32]

- Optimization Algorithms: Single- and multi-objective optimization algorithms compatible with surrogate models [15] [1]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Parameter Selection and Range Definition:

Design of Experiments:

High-Fidelity Simulation:

Surrogate Model Training:

- Partition data into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets [34]

- Train multiple surrogate types (PRS, Kriging, ANN, PCE) on training data

- Optimize hyperparameters for each model type using cross-validation

Model Validation:

Implementation in Optimization Framework:

Expected Outcomes: The protocol should yield validated surrogate models capable of accurately predicting API process performance metrics. Successful implementation typically achieves 1.5-3.6% improvement in yield while maintaining or improving purity standards, as demonstrated in pharmaceutical case studies [15].

Protocol 2: Microstructural Optimization of Structural Materials

Objective: To optimize microstructural features of structural materials (e.g., wrought aluminum alloys) for enhanced mechanical properties using surrogate modeling [30].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- 3D Image-Based Simulation: Finite element software capable of simulating mechanical behavior based on microstructural data [30]

- Microstructural Characterization Tools: Quantitative analysis of size, shape, and spatial distribution of microstructural features [30]

- Feature Selection Algorithm: For reducing dimensionality of design parameters (e.g., from 41 to 4 key parameters) [30]

- Support Vector Machine Framework: With infill sampling criterion for efficient optimization [30]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Microstructural Quantification:

Parameter Space Coarsening:

- Implement two-step coarsening process to reduce parameter dimensionality [30]

- Apply feature importance analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Finalize 3-5 critical parameters that dominantly affect mechanical performance

Training Data Generation:

SVM Surrogate Model Development:

- Train Support Vector Machine models with infill sampling criterion [30]

- Implement active learning strategy to focus simulations on promising regions

- Validate model predictions against additional numerical simulations

Microstructural Optimization:

- Apply optimization algorithms to identify optimal microstructural parameters [30]

- Balance competing objectives (strength, durability, damage resistance)

- Verify optimal configurations through targeted validation simulations

Expected Outcomes: Identification of optimal microstructural characteristics (e.g., small, spherical particles with sparse dispersion perpendicular to loading direction) that enhance mechanical performance while suppressing internal stress concentrations [30].

Implementing surrogate-based optimization requires both computational tools and methodological frameworks. The following table outlines key components of the researcher's toolkit for successful surrogate modeling applications in process systems engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Surrogate-Based Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Methods | Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [32] [31] | Space-filling experimental designs for computer experiments [32] [31] | Initial training data generation [32] |

| Infill Criteria | Expected Improvement (EI) [31] | Balances exploration and exploitation during optimization [31] | Sequential sample selection [31] |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) [33] | Global sensitivity analysis to identify influential parameters [33] | Parameter screening and reduction [30] [33] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Bayesian Optimization (BO) [1] | Efficient global optimization for expensive black-box functions [1] | Single and multi-objective optimization [15] [1] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Gaussian Process Regression (Kriging) [32] [29] | Provides uncertainty estimates with predictions [32] [29] | Reliability-based design optimization [31] |

| Software Environments | COMSOL [32], MATLAB [34], Python/Keras [33] | Integrated platforms for simulation and surrogate modeling [32] [34] [33] | End-to-end implementation [32] [34] [33] |

Applications in Process Systems Engineering and Biomedical Fields

Pharmaceutical Process Optimization

Surrogate-based optimization has demonstrated significant value in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where it enables simultaneous improvement of multiple critical quality attributes. Case studies show that unified surrogate optimization frameworks can achieve a 1.72% improvement in Yield and a 7.27% improvement in Process Mass Intensity in single-objective optimization, while multi-objective approaches deliver a 3.63% enhancement in Yield while maintaining high purity levels [15]. These improvements are particularly notable given the stringent regulatory requirements and complex multi-step processes characteristic of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The application of surrogate modeling in quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) has revolutionized virtual patient creation, where machine learning surrogates pre-screen parameter combinations to efficiently identify plausible virtual patients [34]. This approach addresses the challenge of computational expense in mechanistic QSP models, which traditionally required evaluating thousands of parameter combinations to find viable virtual patients. By using surrogates for pre-screening, researchers can focus full model simulations only on the most promising parameter sets, dramatically improving computational efficiency [34].

Materials Design and Medical Device Development

In materials science, surrogate modeling enables the optimization of microstructural features to enhance material performance. The integration of limited 3D image-based numerical simulations with microstructural quantification and optimization processes has proven effective for designing structural materials with superior properties [30]. This approach successfully handles complex design spaces with multiple parameters quantitatively expressing size, shape, and spatial distribution of microstructural features.

Medical device design represents another promising application area, where surrogate models help balance competing objectives such as minimizing device size while maximizing strength or ensuring durability without compromising biocompatibility [29]. The technique enables comprehensive design space exploration with significantly reduced computational cost compared to traditional finite element analysis or computational fluid dynamics simulations [29]. For stent development, for instance, sensitivity analysis using surrogate models can reveal how changes in strut thickness or material composition affect flexibility and restenosis risk, guiding refinements to enhance overall device performance [29].