UV vs. DAD Detectors: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between Ultraviolet (UV) and Diode Array Detection (DAD) in liquid chromatography.

UV vs. DAD Detectors: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between Ultraviolet (UV) and Diode Array Detection (DAD) in liquid chromatography. We explore the foundational principles, operational mechanisms, and distinct advantages of each detector. The content covers practical methodological applications, troubleshooting for common issues, and a comparative validation against other techniques like LC-MS. By synthesizing core intents from foundational knowledge to advanced application, this guide empowers scientists to optimize their analytical methods for accuracy, reliability, and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical and clinical research.

Core Principles: How UV and DAD Detectors Work

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a foundational analytical technique that measures the absorption of light in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum (typically 190-900 nm) [1] [2]. Its implementation in analytical chemistry has evolved from instruments that measure absorbance at a single wavelength to sophisticated detectors that capture full spectral data in real-time [1]. In the context of drug development and scientific research, understanding the distinction between a traditional UV spectrophotometer and a Diode Array Detector (DAD), also known as a Photodiode Array (PDA), is critical for selecting the appropriate analytical tool [1] [3]. While both operate on the principle of the Beer-Lambert law, which relates the absorption of light to the properties of the material through which the light is passing, their instrumental designs, data output, and applications differ significantly [2]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two core technologies, framing them within the broader paradigm shift from targeted single-wavelength analysis to comprehensive full-spectrum characterization.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

The Fundamental Operating Principles

At its core, any UV-Vis detection technique involves passing a beam of light through a sample and measuring the intensity of the light that emerges. The absorbance (A) is calculated as A = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I), where Iâ‚€ is the intensity of the incident light, and I is the intensity of the transmitted light [2]. This absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte, the path length of the light through the sample, and a substance-specific parameter known as its molar absorptivity, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [2]. The key differentiator between technologies lies in how they generate, select, and detect specific wavelengths of light to probe the sample.

UV Spectrophotometer Optical Design

A traditional UV or UV-Vis spectrophotometer is a single-wavelength or variable-wavelength detector. Its optical system is designed to select a specific wavelength before the light interacts with the sample [3].

- Light Source: Often uses two lamps: a Deuterium (Dâ‚‚) lamp for the UV range (190-380 nm) and a Tungsten (W) lamp for the visible range (380-900 nm) [2] [3].

- Wavelength Selection: A key component is the monochromator, typically a diffraction grating that disperses the broad-spectrum light. The angle of this grating is physically adjusted to allow only a narrow band of desired wavelengths to pass through the exit slit and onto the sample flow cell [2] [3].

- Detection: The selected monochromatic light passes through the flow cell, and a single photoreceptor (such as a photomultiplier tube) measures its intensity after the sample [3]. A reference beam is often used to compensate for source intensity fluctuations [2].

This sequential design means that to collect data at multiple wavelengths, the monochromator must be scanned over time, which is a limitation for capturing rapid spectral changes in a chromatographic peak.

Diode Array Detector (DAD) Optical Design

A Diode Array Detector (DAD) revolutionizes this process by being a multi-wavelength detector that captures the entire spectrum simultaneously [1] [4] [3].

- Light Source: Employs the same or similar broad-spectrum lamps (Dâ‚‚ and W) as the UV spectrophotometer [4].

- Optical Path: The fundamental difference is the order of components. In a DAD, the full-spectrum "white" light is first passed directly through the sample flow cell [3].

- Dispersion and Detection: The transmitted light, which now contains the absorption signature of the sample, is then focused onto a diffraction grating. This grating disperses the light, spreading it across an array of hundreds of photodiodes (e.g., 1024 diodes), each corresponding to a specific, narrow wavelength band [3]. All diodes measure their respective light intensities at the same time, capturing a complete UV-Vis spectrum in a single, rapid measurement (often in milliseconds) [1].

This parallel detection scheme is the source of the DAD's significant advantages for qualitative analysis and peak purity assessment.

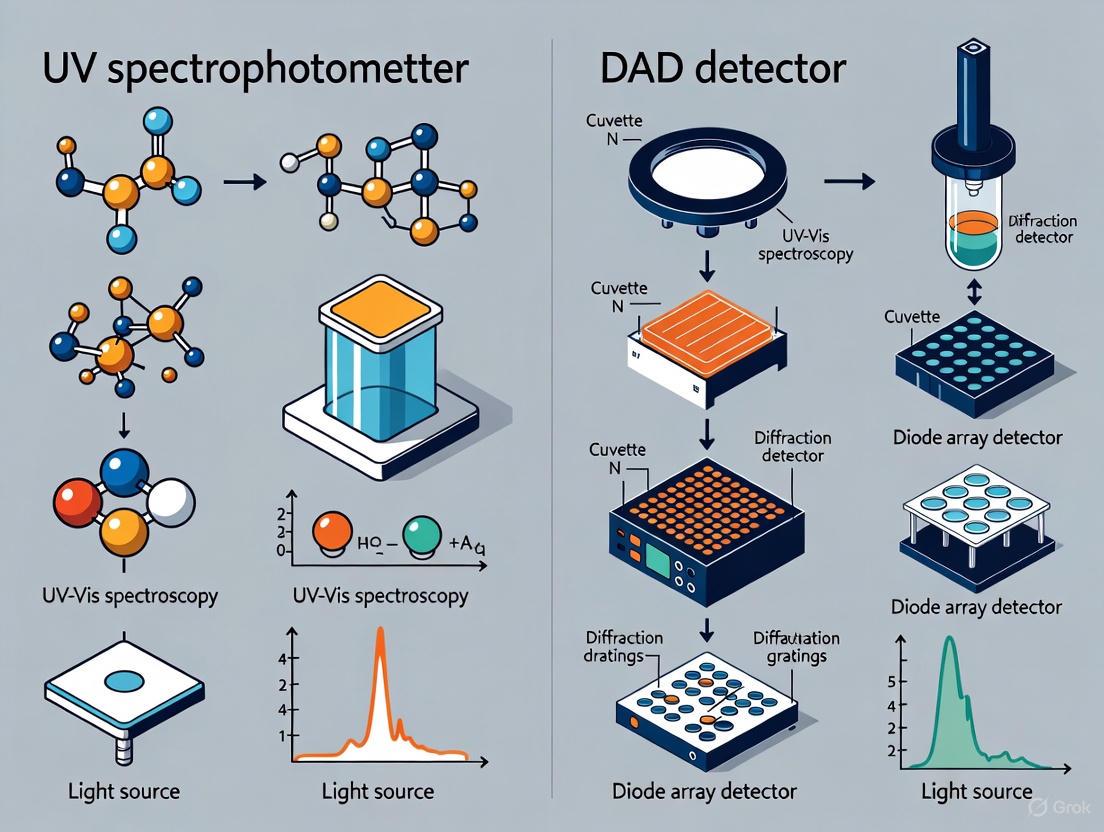

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in the optical paths of these two systems:

Technical Comparison and Data Output

The differing instrumental designs of UV and DAD detectors lead to a direct impact on the nature and richness of the data they produce, which in turn dictates their suitability for various analytical tasks.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of UV Spectrophotometer vs. Diode Array Detector

| Feature | UV Spectrophotometer | Diode Array Detector (DAD) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Type | Single- or Variable-Wavelength | Simultaneous Multi-Wavelength |

| Wavelength Selection | Before the sample (Pre-dispersion) | After the sample (Post-dispersion) [3] |

| Spectral Acquisition | Sequential; requires scanning over time | Parallel; full spectrum captured instantaneously [1] |

| Primary Data Output | Chromatogram (Absorbance vs. Time at λ) | 3D Data Cube (Absorbance vs. Time vs. Wavelength) [1] |

| Typical Sensitivity | Generally higher for a single wavelength due to greater light throughput | Slightly lower per wavelength due to light dispersion, but modern designs have minimized this gap [3] |

| Peak Purity Assessment | Not possible directly | Yes, by comparing spectra across a peak [1] |

| Spectral Fidelity | Excellent for a single wavelength | High, but can be more susceptible to lamp fluctuations as reference beam is not always used [3] |

The data output is a key differentiator. A UV detector produces a chromatogram—a two-dimensional plot of absorbance (at one or a few pre-selected wavelengths) over time. In contrast, a DAD generates a rich, three-dimensional data set, which can be visualized as a contour plot (wavelength vs. time, with absorbance as contour lines) or as a series of spectra extracted at any point in time [1] [3]. This allows a scientist to retrospectively interrogate the data, examining the spectrum of any peak without having to re-run the sample.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol 1: Quantification of a Target Analyte using a UV Detector

This protocol is ideal for routine, high-sensitivity quantification of known compounds where spectral confirmation is not required, such as in quality control (QC) labs [5].

Method Development and Calibration:

- Based on prior knowledge or a spectral scan, determine the wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_max) for the target analyte.

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of known concentration.

- Set the detector wavelength to the chosen λ_max.

- Inject the standards to create a calibration curve of peak area versus concentration.

Sample Analysis:

- Maintain the same wavelength and chromatographic conditions.

- Inject the unknown sample.

- Identify the target analyte based on its retention time.

- Quantify the analyte by comparing its peak area to the calibration curve.

Key Advantage for this Application: The UV detector often provides superior signal-to-noise for quantification at a single wavelength, making it highly sensitive and well-suited for regulated QC environments where methods are fixed [5].

Protocol 2: Method Development and Peak Purity Analysis using a DAD

This protocol leverages the full power of DAD for methods where identification and purity are as important as quantification, such as in pharmaceutical impurity profiling or natural product analysis [1].

Data Acquisition:

- The DAD is set to acquire data across a full wavelength range (e.g., 200-400 nm) throughout the chromatographic run.

- No pre-selection of a single wavelength is necessary.

Post-Run Interrogation and Method Optimization:

- Extract the chromatogram at the wavelength that provides the best signal-to-noise and separation for each compound.

- For any peak of interest, extract its UV-Vis absorption spectrum from the apex and compare it to a library spectrum for compound identity confirmation—a second factor in addition to retention time [1].

Peak Purity Assessment:

- This is a critical application for DAD. The software compares spectra from the upslope, apex, and downslope of the chromatographic peak.

- A high degree of spectral similarity indicates a pure peak. Spectral differences suggest a co-eluting impurity [1].

- Advanced software functions, like Shimadzu's i-PDeA, can even deconvolute and quantify the individual components in an unresolved peak using their unique spectral profiles [1].

Key Advantage for this Application: The DAD provides a second dimension of identification (spectral match) and is indispensable for revealing hidden impurities that a single-wavelength detector would miss.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for UV-Vis HPLC Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function and Critical Specifications |

|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Serve as the mobile phase; low UV absorbance to minimize baseline noise and drift. Must be spectrally pure for the wavelength range used. |

| Deuterium (Dâ‚‚) Lamp | Light source for the UV range (190-380 nm). A consumable item with a finite lifetime that requires periodic replacement [4]. |

| Tungsten (W) Lamp | Light source for the visible range (380-900 nm). Also a consumable item subject to replacement [4]. |

| Quartz Flow Cell | Container for the sample in the detector path. Quartz is essential for UV transparency; standard glass or plastic cuvettes absorb UV light [2]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | High-purity compounds used for instrument calibration, method validation, and creation of spectral libraries for compound identification. |

The following workflow diagram summarizes the decision-making process for selecting and applying these two detection technologies:

Market Trends and Future Outlook

The landscape of UV-Vis detection is dynamic, with several key trends shaping its future, particularly for diode array technology.

- Growth and Drivers: The global UV-Vis spectrometer market is projected for steady growth, driven by R&D investments in life sciences and pharmaceuticals, as well as environmental monitoring needs [6]. The North American DAD market, for instance, is seeing strong growth due to demand for precision and reliability in pharmaceutical and biotechnology applications [7].

- Technological Integration: A major trend is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning with DAD systems. AI algorithms are being developed to predict spectral shifts, automate compound identification, and enhance peak deconvolution, thereby reducing the analytical burden on scientists [7].

- Miniaturization and Portability: The development of compact, portable, and even handheld UV-Vis instruments is expanding the technique's application into field analysis, point-of-care testing, and on-site quality control [6].

- Sustainability: Manufacturers are increasingly focusing on developing energy-efficient instruments and promoting workflows that reduce solvent consumption, aligning with broader green chemistry initiatives [7].

- Hybrid and Advanced Detection: There is a growing trend towards hybrid technologies that combine DAD with other detection methods like mass spectrometry or fluorescence, offering multiparametric data from a single analytical run [7].

The choice between a traditional UV spectrophotometer and a Diode Array Detector is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the analytical question at hand. The UV detector excels in applications where high-sensitivity quantification of known compounds at a fixed wavelength is the primary goal, offering performance and often a lower cost for these specific tasks. In contrast, the DAD provides unparalleled qualitative power and analytical confidence through its ability to capture full spectral data for every data point in a chromatogram. This makes it indispensable for method development, peak purity analysis, and the identification of unknown compounds. Within the context of modern drug development, where regulatory demands for comprehensive analytical characterization are ever-increasing, the DAD has become a cornerstone technology. The ongoing trends of automation, AI integration, and miniaturization promise to further enhance the capabilities of both technologies, solidifying their critical role in the scientist's toolkit for years to come.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique that measures the absorption of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light by a sample in comparison to a reference or blank sample [2]. This property is influenced by the sample composition, providing critical information about the identity and concentration of chromophoric compounds present. The technique operates on the principle that electrons in different bonding environments within a substance require specific amounts of energy to promote to higher energy states, which we detect as absorption at characteristic wavelengths [2]. The diode array detector (DAD), also known as a photodiode array detector (PDA), represents a significant evolution in detection technology, enabling simultaneous monitoring of multiple wavelengths across the UV-Vis spectrum (typically 190-900 nm) and providing three-dimensional data (absorbance, wavelength, and time) that offers distinct advantages for compound identification, peak purity assessment, and method development [4] [1] [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of UV-Vis Spectrophotometer and DAD Configurations

| Feature | Traditional UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Diode Array Detector (DAD) |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Path Design | Single-beam or double-beam; pre-sample dispersion | Reversed optics; post-sample dispersion |

| Wavelength Selection | Monochromator with moving grating before sample | Fixed polychromator with diode array after sample |

| Wavelength Range | Typically 190-900 nm (depends on source and detector) | Typically 190-900 nm (depends on source and detector) |

| Data Acquisition | Sequential wavelength measurement | Simultaneous full-spectrum acquisition |

| Spectral Resolution | Controlled by slit width and grating | Determined by diode density and slit width |

| Primary Applications | Single wavelength quantification, kinetic studies | Multi-analyte detection, peak purity, method development |

Core Optical Components and System Architecture

The optical systems of both conventional UV-Vis spectrophotometers and diode array detectors are engineered around several critical components that work in concert to generate reliable spectroscopic data.

UV-Vis instrumentation typically employs two complementary light sources to cover the full spectral range. A deuterium (D₂) lamp provides continuous emission in the ultraviolet region (190–400 nm), while a tungsten-halogen (W) lamp covers the visible to near-infrared region (330–900 nm) [4] [9]. In some systems, a single xenon lamp may be used for both regions, though this approach is associated with higher costs and potential stability issues [2]. The transition between lamps typically occurs between 300-350 nm where their light emission characteristics are similar, ensuring a smooth switchover [2]. The light sources are designed for stability and longevity, as fluctuations in intensity directly impact measurement accuracy.

Wavelength Selection and Dispersion Systems

This represents the most significant architectural difference between conventional UV-Vis and DAD systems:

In a traditional UV-Vis spectrophotometer, a monochromator is placed before the sample. This system consists of an entrance slit, a diffraction grating that can be rotated to select specific wavelengths, and an exit slit [9] [8]. The grating's groove frequency (typically 300-2000 grooves per mm, with 1200 being common) determines the optical resolution, with higher frequencies providing better resolution but narrower usable wavelength ranges [2]. The selected monochromatic light then passes through the sample, and the transmitted intensity is measured by a single detector.

In a diode array detector, a "reversed optics" configuration is employed where polychromatic (full spectrum) light first passes through the sample, and is then dispersed onto a diode array [10] [8]. The dispersion is typically achieved by a fixed holographic grating that spreads the transmitted light across an array of hundreds of individual photodiodes (typically 512 or 1024 elements), each measuring a specific, narrow wavelength band simultaneously [10] [8].

Flow Cells and Sample Compartments

The flow cell is a critical component where light-sample interaction occurs. It is a transparent, flow-through device with quartz windows at each end that define the optical pathlength [8]. Standard HPLC flow cells have volumes of 8-18 μL with a 10 mm pathlength, while UHPLC applications require smaller cells (0.5-1 μL) to maintain chromatographic resolution [8]. Quartz is essential for UV applications as it is transparent to most UV light, unlike glass or plastic which absorb significantly in the UV region [2]. Proper flow cell design minimizes band broadening while maximizing signal intensity through an optimized pathlength.

Detection Systems

Detection systems convert transmitted light intensity into electronic signals for data processing. Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) are commonly used in conventional spectrophotometers due to their high sensitivity and wide dynamic range; they operate via the photoelectric effect, where photons incident on a photocathode eject electrons that are then amplified through a series of dynodes [2] [9]. Silicon photodiodes are semiconductor devices that generate a photocurrent when photons with energy greater than the bandgap of silicon are absorbed, creating electron-hole pairs that are separated by an internal electric field [9]. In DAD systems, arrays of hundreds of individual photodiodes (512 or 1024 elements are common) enable simultaneous detection across the entire spectral range, with each diode dedicated to a specific narrow wavelength band [10] [8].

Diagram 1: Optical pathway comparison between traditional UV-Vis spectrophotometers and diode array detectors

Data Acquisition Pathways and Signal Processing

The data acquisition pathways differ fundamentally between conventional UV-Vis and DAD systems, leading to their distinct capabilities and applications.

Signal Formation and Processing

In both systems, absorbance (A) is calculated according to the Beer-Lambert law as A = -logâ‚â‚€(I/Iâ‚€) = εlc, where Iâ‚€ is the incident light intensity, I is the transmitted light intensity, ε is the molar absorptivity, l is the path length, and c is the concentration [2] [8]. In conventional UV-Vis systems, this calculation occurs sequentially for each wavelength as the monochromator rotates through its programmed range. In DAD systems, the calculation occurs simultaneously across all wavelengths, with the diode array capturing complete spectral data at each time point during chromatographic separation [4] [1].

Critical Detector Parameters and Their Optimization

Several operational parameters must be optimized to ensure data quality:

- Spectral Bandwidth: The range of wavelengths measured around a target wavelength, typically 1-8 nm. Narrower bandwidths provide better spectral resolution but reduce light throughput and signal-to-noise ratio [9] [10].

- Acquisition Rate: For chromatography applications, the data acquisition rate must be sufficient to capture peak profiles accurately, with a minimum of 20-25 data points across a chromatographic peak for reliable quantification [10].

- Reference Wavelength: Selective use of a reference wavelength (typically 60 nm higher than where analyte absorbance falls to 1 mAU) with a wide bandwidth (typically 100 nm) can compensate for baseline drift caused by refractive index changes during gradient elution [10].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Optimization Parameters

| Parameter | Impact on Data Quality | Quantitative Optimization | Qualitative Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Bandwidth | Narrow: better resolution; Wide: better S/N | 4-8 nm (prioritize signal-to-noise) | 1-4 nm (prioritize spectral features) |

| Slit Width | Controls light throughput to detector | 4-8 nm (better S/N) | 1-4 nm (better resolution) |

| Data Acquisition Rate | Point density across chromatographic peaks | 2-5 Hz (standard HPLC) | ≥10 Hz (fast UHPLC) |

| Response Time | Signal smoothing vs. peak distortion | 1-2 s (reduced noise) | 0.1-0.5 s (preserved peak shape) |

Experimental Protocols for System Characterization

Wavelength Accuracy Verification

Purpose: To validate the accuracy of wavelength selection and detection across the operational range. Materials: Holmium oxide or didymium (neodymium) glass filters, certified reference materials with known absorption maxima. Methodology:

- Place reference filter in sample compartment or flow cell

- Perform full spectrum scan from 190-900 nm with 1 nm bandwidth

- Record observed absorption maxima

- Compare measured peak wavelengths against certified values Acceptance Criteria: Deviation ≤ ±1 nm from certified values across UV-Vis range [9] [8]

Photometric Accuracy and Linearity Assessment

Purpose: To verify absorbance measurement accuracy across the dynamic range. Materials: Neutral density filters or certified potassium dichromate solutions in perchloric acid. Methodology:

- Measure absorbance of certified standards at multiple wavelengths

- Prepare serial dilutions covering absorbance range 0.1-3.0 AU

- Plot measured vs. certified absorbance values

- Calculate correlation coefficient and residual values Acceptance Criteria: Correlation coefficient R² ≥ 0.999, residuals within ±0.01 AU [8]

Stray Light Determination

Purpose: To quantify stray light that affects photometric linearity at high absorbances. Materials: High-purity potassium chloride or sodium iodide solutions. Methodology:

- Prepare 10-12% (w/v) KCl or NaI solution

- Measure absorbance at 198 nm (KCl) or 220 nm (NaI) with water reference

- Calculate percent transmittance: %T = 100 × 10^(-A) Acceptance Criteria: Stray light ≤ 0.1% T at specified wavelength [9]

Spectral Resolution Validation

Purpose: To confirm the instrument's ability to distinguish closely spaced spectral features. Materials: Toluene in hexane (0.02% v/v) or mercury vapor lamp. Methodology:

- Record toluene spectrum in hexane from 250-300 nm

- Measure peak-to-valley ratio between 269 nm and 266 nm

- Calculate resolution factor: R = A₂₆₉ / A₂₆₆ Acceptance Criteria: Resolution factor R ≥ 1.5 [9] [10]

Advanced DAD Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The unique capabilities of diode array detectors enable several advanced applications that are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research and quality control.

Peak Purity Assessment

Peak purity analysis compares UV spectra at multiple points across a chromatographic peak (up-slope, apex, and down-slope) to detect potential co-elution of impurities [1] [8]. Software algorithms calculate a peak purity index or purity angle by normalizing and comparing these spectra; a purity index close to 1.000 or a small purity angle indicates a homogeneous peak, while significant spectral differences suggest the presence of multiple compounds [1] [8]. This application is particularly valuable for stability-indicating methods and impurity profiling required by ICH guidelines [8] [11].

Spectral Deconvolution of Co-eluting Compounds

Advanced DAD software can mathematically resolve co-eluting compounds based on their spectral differences, even when chromatographic resolution is incomplete [1]. Techniques such as Shimadzu's i-PDeA function utilize the complete spectral information collected during the chromatographic run to deconvolute overlapping peaks, providing quantitative data for individual components without complete physical separation [1]. This capability is particularly useful for analyzing complex mixtures where complete chromatographic separation may be time-consuming or difficult to achieve.

Method Development and Transfer

During method development, the continuous spectral data collected by DAD systems facilitates optimal wavelength selection for quantification by identifying the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for each compound while minimizing interference from other sample components or mobile phase absorption [10]. This comprehensive data collection also simplifies method transfer between different laboratories or instruments by providing spectral evidence of equivalent separation and detection [12] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for UV-Vis and DAD Applications

| Material/Component | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterium (Dâ‚‚) Lamp | UV light source (190-400 nm) | Continuous spectrum, ~1000 hour lifespan [4] [8] |

| Tungsten-Halogen (W) Lamp | Visible light source (330-900 nm) | Continuous spectrum, ~2000 hour lifespan [4] [8] |

| Quartz Flow Cells | Sample containment for UV detection | 10 mm pathlength, 1-18 μL volume, high-pressure compatible [8] |

| Holmium Oxide Filters | Wavelength accuracy verification | Certified NIST-traceable absorption maxima [9] |

| Potassium Dichromate | Photometric linearity standards | High purity, certified for absorbance accuracy [8] |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | HPLC chromatographic separation | HPLC grade, low UV cutoff (e.g., ACN: 190 nm, MeOH: 205 nm) [10] |

The optical systems of both traditional UV-Vis spectrophotometers and diode array detectors incorporate sophisticated component architectures designed to measure light absorption by chemical compounds. While both technologies share fundamental principles based on the Beer-Lambert law, their optical pathways differ significantly—with conventional instruments employing pre-sample dispersion and sequential wavelength measurement, while DAD systems utilize post-sample dispersion and simultaneous full-spectrum acquisition. This fundamental architectural difference enables the DAD's advanced applications in peak purity assessment, spectral deconvolution, and multi-wavelength method development, making it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical analysis where reliability, peak identification, and impurity detection are paramount. Despite the growing prominence of mass spectrometric detection, UV-Vis and DAD technologies remain firmly established in research and quality control laboratories due to their robustness, precision, and fitness-for-purpose in quantifying chromophoric compounds.

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is a fundamental relationship in absorption spectroscopy that connects the attenuation of light to the properties of a substance through which it passes [13]. This principle serves as the cornerstone for quantitative analysis across numerous scientific disciplines, enabling researchers to determine the concentration of analytes in solution by measuring how much light they absorb at specific wavelengths [14]. In the context of pharmaceutical research and drug development, where precise quantification of compounds is paramount, understanding and applying this law is essential for techniques ranging from simple concentration verification to sophisticated chromatographic analysis.

When electromagnetic radiation passes through a medium containing absorbing molecules, photons of specific energies may be absorbed, promoting electrons to higher energy states [15]. The likelihood of absorption at a given wavelength depends on the molecular structure and electronic configuration of the analyte, creating unique spectral fingerprints that can be exploited for both identification and quantification purposes [16]. The Beer-Lambert Law provides the mathematical framework to translate these absorption measurements into meaningful chemical information, forming the theoretical basis for ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and absorbance detection in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [15].

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Concepts and Mathematical Formulation

The Beer-Lambert Law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of light by a substance and three key parameters: the concentration of the absorbing species, the path length the light travels through the material, and the intrinsic ability of the substance to absorb light at a specific wavelength [14]. This relationship is mathematically expressed as:

A = εlc

Where:

- A is the absorbance (a dimensionless quantity) [13] [14]

- ε is the molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient (typically in L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) [14]

- l is the path length of light through the sample (typically in cm) [14]

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (typically in mol/L) [14]

Absorbance is derived from experimental measurements of light intensity and has a logarithmic relationship with transmittance [13]:

A = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I) = -logâ‚â‚€(T)

Where:

- Iâ‚€ is the intensity of incident light [13] [14]

- I is the intensity of transmitted light [13] [14]

- T is the transmittance (I/Iâ‚€) [13]

This logarithmic relationship means that each unit increase in absorbance corresponds to a tenfold decrease in transmittance [13]. The following table illustrates this fundamental relationship between absorbance and transmittance:

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance Values

| Absorbance | Transmittance |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

Requirements for Applicability

For the Beer-Lambert Law to apply accurately, several conditions must be met [17]:

- Monochromatic Light: The incident light should consist of a single wavelength [17]

- Homogeneous Solution: The sample must be uniform and non-scattering [17]

- Dilute Solutions: Absorbing particles must not interact with each other [17]

- No Secondary Processes: The measurement should not be affected by fluorescence or photochemical reactions [17]

- Optimal Absorbance Range: For best results, absorbance values should typically fall between 0.2 and 0.8 [17]

Deviations from these conditions can lead to nonlinear relationships between absorbance and concentration, limiting the law's accuracy for quantitative applications [17].

Instrumentation for UV-Vis Absorbance Detection

Fundamental Spectrophotometer Design

UV-Vis spectrophotometers operate on the principle of measuring the difference in light intensity before and after it passes through a sample [16]. All instruments in this category share several core components, regardless of their specific configuration:

- Light Source: Typically deuterium (Dâ‚‚) lamps for UV regions (190-380 nm) and tungsten (W) or halogen lamps for visible regions (380-900 nm) [3] [16]

- Wavelength Selection System: Monochromators (using diffraction gratings) or filters to select specific wavelengths [16]

- Sample Holder: Cuvettes with defined path lengths (typically 1 cm) or flow cells for HPLC [13] [15]

- Detector: Photodiodes, photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), or diode arrays to convert light intensity to electrical signals [16]

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of a UV-Vis absorbance measurement system:

Single vs. Double Beam Spectrophotometers

UV-Vis spectrophotometers are primarily categorized into single beam and double beam configurations, each with distinct advantages and limitations [18] [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Single Beam and Double Beam Spectrophotometers

| Feature | Single Beam | Double Beam |

|---|---|---|

| Light Path | Single beam passes through sample only [18] | Beam split into reference and sample paths [18] |

| Measurement Approach | Sequential measurement of blank and sample [19] | Simultaneous measurement of sample and reference [18] |

| Accuracy | Moderate, susceptible to source fluctuations [18] | High, compensates for source instability [18] [19] |

| Stability | Prone to drift due to environment and lamp aging [18] | Excellent stability through real-time compensation [18] [19] |

| Measurement Speed | Slower due to manual switching between blank and sample [19] | Faster with real-time reference correction [19] |

| Cost | Lower initial and maintenance costs [18] [19] | Higher due to complex optical design [18] [19] |

| Optimal Applications | Education, routine analyses, cost-sensitive environments [18] [19] | Research, pharmaceutical QC, high-precision applications [18] [19] |

The double beam design provides significantly better stability and accuracy because any fluctuations in the light source equally affect both beams and are therefore canceled out in the absorbance calculation [18]. This ratiometric measurement makes double beam instruments particularly valuable for applications requiring high precision and long-term stability [18] [19].

Detector Technologies in HPLC

UV-Vis Detectors

UV-Vis detectors are among the most common detection systems used in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [15]. These detectors employ a deuterium lamp as a light source for ultraviolet wavelengths, with some models incorporating an additional tungsten lamp for visible light detection [3]. The operational principle involves shining monochromatic light through the HPLC flow cell onto a photodetector, which converts light intensity into an electrical signal corresponding to absorbance [15].

In a conventional UV-Vis detector, light from the source is directed onto a diffraction grating, which disperses it into different wavelengths [3]. The grating angle is adjusted to select a specific wavelength that then passes through the flow cell containing the separated analytes [3]. A key feature of many modern UV detectors is the ability to monitor reference light divided from the light source before it reaches the flow cell, enabling compensation for lamp intensity fluctuations [3]. This design is particularly suited for targeted analyses where specific compounds are monitored at predetermined wavelengths, such as natural product analyses commonly performed at 220 nm and 274 nm [1].

Photodiode Array (PDA) Detectors

Photodiode Array (PDA) detectors, also known as Diode Array Detectors (DAD), represent a significant advancement in absorbance detection technology [1] [15]. Unlike conventional UV-Vis detectors that monitor one or a few discrete wavelengths, PDA detectors capture the entire spectrum simultaneously [1] [3]. This comprehensive wavelength coverage is achieved through a reversed optical path: light from the source passes directly through the flow cell, and the transmitted light is then dispersed by a diffraction grating onto an array of photodiodes (typically 1024 elements) [15] [3].

This fundamental difference in optical design enables several advanced capabilities:

- Full Spectrum Acquisition: Continuous monitoring of all wavelengths in real-time [1]

- Spectral Confirmation: Compound identification through spectral matching in addition to retention time [1] [15]

- Peak Purity Assessment: Detection of co-eluting compounds by comparing spectra across a chromatographic peak [1]

- Method Development: Selection of optimal wavelengths for routine analysis based on full spectral data [1]

The following diagram illustrates the key differences in optical layout between conventional UV and PDA detectors:

Comparative Analysis: UV vs. PDA Detectors

Table 3: Performance Comparison Between UV and PDA Detectors for HPLC

| Characteristic | UV Detector | PDA Detector |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Selection | Before flow cell [15] [3] | After flow cell [15] [3] |

| Spectral Data | Single or few discrete wavelengths [1] | Full UV-Vis spectrum continuously [1] [15] |

| Qualitative Power | Limited to retention time matching [1] | Spectral confirmation plus retention time [1] [15] |

| Peak Purity Assessment | Not possible without additional runs | Built-in capability through spectral comparison [1] |

| Sensitivity | Generally higher light throughput [3] | Potentially higher noise due to light splitting [3] |

| Method Development | Requires prior knowledge of optimal wavelengths | Enables post-run wavelength optimization [1] |

| Data Complexity | Simple chromatograms at fixed wavelengths | Three-dimensional data (time, absorbance, wavelength) [15] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower initial investment | Higher cost due to complex optics and electronics [3] |

For pharmaceutical applications, PDA detectors offer significant advantages in method development and validation through their peak purity assessment capabilities [1]. By comparing UV spectra at different points across a chromatographic peak (up-slope, apex, and down-slope), analysts can detect potential co-elution that might otherwise go unnoticed with single-wavelength detection [1]. This functionality is particularly valuable in regulated environments where demonstrating method specificity is required for compliance [1].

Practical Applications and Experimental Approaches

Quantitative Analysis Using Calibration Curves

The primary application of the Beer-Lambert Law in pharmaceutical research is quantitative analysis through calibration curves [13]. This approach involves measuring absorbance values of standard solutions with known concentrations, then fitting these data points to establish a linear relationship between absorbance and concentration [13] [16].

A typical experimental protocol for creating a calibration curve includes:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Create a series of solutions with known concentrations spanning the expected range of the unknown samples [13] [16]

- Blank Measurement: Use the solvent or buffer without analyte as a reference to establish baseline absorbance [16]

- Absorbance Measurement: Record absorbance values for each standard at the optimal wavelength (typically λmax) [16]

- Data Analysis: Plot absorbance versus concentration and perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the calibration curve [13] [16]

- Sample Measurement: Measure unknown samples under identical conditions and calculate concentration using the calibration equation [13]

The following diagram illustrates this quantitative workflow:

Advanced Measurement Techniques

Beyond simple single-wavelength measurements, several advanced applications of the Beer-Lambert Law provide solutions for challenging analytical scenarios:

Dual Wavelength Measurements: Used when interfering substances contribute to absorbance at the primary analytical wavelength. The absorbance is calculated as A = Aλ₠- k×Aλ₂, where k is a correction factor [17]. This approach is commonly employed in environmental analysis, such as total nitrogen determination where A₂₂₀ is corrected using A₂₇₅ to account for dissolved organic matter interference [17]

Multi-Component Analysis: When multiple absorbing species with overlapping spectra are present in a sample, concentrations can be determined by measuring absorbance at multiple wavelengths and solving simultaneous equations based on each component's unique molar absorptivity at these wavelengths [16]

Peak Deconvolution: Advanced PDA software can mathematically resolve co-eluting peaks in chromatography based on their spectral differences, enabling quantification without physical separation [1]. The i-PDeA (intelligent Peak Deconvolution and Analysis) function exemplifies this approach, using both chromatographic and spectral information for virtual separation of unresolved compounds [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UV-Vis Absorbance Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Calibration and verification of instrument performance [20] | NIST standards (mAbs, tryptophan, uracil) for compliance with USP/Ph. Eur. guidelines [20] |

| Optical Cuvettes | Sample containment with defined path length [16] | Quartz for UV work (transparent down to 190 nm); plastic/disposable for visible range only [16] |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | HPLC eluent for compound separation [15] | High purity, UV-transparent solvents (e.g., HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, water) [15] |

| Standard Compounds | Calibration curve establishment [13] [16] | High-purity analytes for generating quantitative reference data [13] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain consistent pH environment [16] | Phosphate, Tris, or other buffers with minimal UV absorbance in region of interest [16] |

| (6S)-CP-470711 | (6S)-CP-470711, MF:C18H26N6O2, MW:358.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| VH032-thiol-C6-NH2 | VH032-thiol-C6-NH2, MF:C29H43N5O4S2, MW:589.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Considerations for Pharmaceutical Applications

Method Validation and Regulatory Compliance

In pharmaceutical development, UV-Vis methods must undergo rigorous validation to ensure reliability, accuracy, and precision [20]. Key validation parameters include:

Linearity and Range: Demonstration that the response is proportional to analyte concentration across the specified range [13] [17]. The Beer-Lambert Law typically holds best in the absorbance range of 0.2-0.8, though modern instruments may extend this dynamic range [17] [20]

Accuracy: The closeness of measured values to the true value, often established using certified reference materials [20]. Instruments like the Lunatic and Stunner systems demonstrate accuracy within 2% of NIST reference values, complying with USP and European Pharmacopoeia guidelines [20]

Precision: The degree of agreement among repeated measurements, expressed as relative standard deviation [20]. High-quality systems can achieve precision within 1% [20]

Specificity: The ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of potential interferents [1]. PDA detectors excel in this area through peak purity assessment and spectral confirmation [1]

Microvolume and High-Throughput Applications

Modern drug discovery increasingly requires analytical techniques that conserve precious samples while providing high-throughput capabilities [20]. Advanced UV-Vis systems address these needs through innovative designs:

Fixed Pathlength Microvolume Cells: Systems like the Lunatic and Stunner implement fixed pathlength microcuvettes (0.1 mm and 0.7 mm) in a 96-well plate format, enabling analysis of 2 μL samples with a 10-minute throughput for 96 samples [20]

Extended Dynamic Range: The combination of different pathlengths allows concentration measurement across a wider range without dilution - from 0.02-200 mg/mL for IgG and 1.5-13,750 ng/μL for nucleic acids [20]

Evaporation Prevention: Microfluidic circuits prevent sample evaporation and cross-contamination, critical for accurate quantitative results [20]

The Beer-Lambert Law remains the fundamental principle underpinning UV-Vis absorbance detection, providing the theoretical foundation for quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical research and drug development. While the basic relationship A = εlc has remained unchanged, its implementation through increasingly sophisticated instrumentation continues to evolve. From traditional single beam spectrophotometers to advanced PDA detectors with peak deconvolution capabilities, the application of this law has expanded to address complex analytical challenges.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate detection technology involves careful consideration of analytical requirements, regulatory needs, and practical constraints. UV detectors offer simplicity and sensitivity for targeted analyses, while PDA systems provide comprehensive spectral data for method development and validation. As pharmaceutical analyses demand higher throughput, minimal sample consumption, and greater reliability, innovations in absorbance detection continue to enhance our ability to apply this fundamental principle to the challenging problems of modern drug development.

In the realm of analytical chemistry, the detection and quantification of compounds fundamentally rely on their ability to interact with light. At the heart of this interaction is the chromophore, a functional group within a molecule responsible for its absorption of ultraviolet (UV) or visible light. Understanding chromophores and the spectral response of compounds is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals who utilize techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to separate and analyze complex mixtures. The core principle governing this interaction is the Beer-Lambert Law (often simply called Beer's Law), which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the pathlength (d) of the light through the solution: A = ε × c × d. The constant of proportionality, ε, is the molar absorptivity (or molar absorption coefficient), a compound-specific value that defines how strongly a chromophore absorbs light at a particular wavelength [21]. A higher molar absorptivity translates to a lower detectable concentration, making it a critical parameter for assay sensitivity.

This technical guide explores the fundamental properties that make a compound detectable by UV spectroscopy, framed within a critical comparison of two predominant detection technologies: the traditional UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (often referred to as a Variable Wavelength Detector or VWD in chromatography) and the more information-rich Diode Array Detector (DAD or PDA). The choice between these detectors represents a significant methodological decision in analytical research, balancing sensitivity, specificity, and the depth of information required for compound identification and purity assessment.

Fundamental Principles of Chromophores and UV-Vis Absorption

What is a Chromophore?

A chromophore is a region in a molecule where the energy difference between molecular orbitals falls within the range of ultraviolet or visible light. When light of a specific energy (wavelength) hits this chromophore, electrons are promoted from a ground state to an excited state, resulting in the absorption of that light. The specific wavelengths absorbed and the intensity of that absorption depend on the chemical structure and the electronic environment of the chromophore. Common chromophores in organic molecules include carbonyl groups (C=O), aromatic rings (e.g., benzene, naphthalene), azo groups (-N=N-), and sequences of conjugated double bonds [21]. The presence of these groups is a primary indicator that a compound will be amenable to UV-Vis detection.

Key Parameters in Spectral Response

The detectability of a compound is not a binary proposition but is instead governed by several key parameters derived from its UV-Vis spectrum:

- λ_max (Maximum Absorbance Wavelength): This is the wavelength at which a compound has its strongest absorption. It is a characteristic property of the chromophore and is often used for selective detection in HPLC to maximize sensitivity for a target analyte [8].

- Molar Absorbance (Molar Absorptivity or ε): This is a measure of how strongly a chromophore absorbs light at a specific wavelength, typically reported in Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹. It is an intrinsic property of the molecule. A higher ε value allows for detection at lower concentrations. For example, the chromophore p-Nitroanilide (pNA) has an ε of ~9,450 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ at 405 nm, making it a highly sensitive probe for enzyme activity assays [21].

- Spectral Bandwidth: This refers to the range of wavelengths that pass through the detector's optical system. A narrower bandwidth can provide better selectivity but may reduce light throughput and signal-to-noise ratio [8].

The following table summarizes the spectral properties of several common chromophores used in biochemical and pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Spectral Properties of Common Chromophores in Research

| Chromophore | Detection Wavelength (λ_max) | Molar Absorption Coefficient (ε) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Nitroanilide (pNA) | 405 - 410 nm | 9,450 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ (405 nm) | Assays for serine and cysteine proteases [21] |

| p-Nitrophenyl (ONp) | 347 nm | 5,500 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ | Esterase activity measurements (pH-independent) [21] |

| 2,4-Dinitrophenyl (Dnp) | 365 nm | 17,300 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ | Peptide cleavage assays after organic extraction [21] |

| 3-(2-Furyl)acryloyl (FA) | 322 - 345 nm | 13,400 - 24,700 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ | Continuous assays for proteases (measured by decrease in absorbance) [21] |

| Thiobenzyl Ester (SBzl) | 324 nm / 410 nm | 19,800 / 14,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ | Enzyme activity via reaction with DTNB (Ellman's reagent) [21] |

A Comparative Analysis: UV Spectrophotometer vs. Diode Array Detector

Operational Principles and Optical Designs

The fundamental difference between a UV Spectrophotometer (VWD) and a Diode Array Detector (DAD) lies in the sequence of optical events: dispersion before detection for VWD versus dispersion after detection for DAD.

A Variable Wavelength Detector (VWD) uses a deuterium (and often a tungsten) lamp to generate polychromatic light. This light passes through a monochromator, typically a movable diffraction grating, which selects a specific, user-defined wavelength. This single wavelength of light then passes through the sample flow cell and onto a single photodiode, which measures its intensity [8] [15]. This design is illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: UV-VWD Optical Path

In contrast, a Diode Array Detector (DAD/PDA) exposes the sample in the flow cell to the entire spectrum of light from the source. The transmitted light is then focused onto a diffraction grating, which disperses it across an array of hundreds of photodiodes (e.g., 512 or 1024). Each diode simultaneously measures the intensity of a specific, narrow band of wavelengths [8] [15]. This allows for the continuous collection of the full spectrum of every analyte as it elutes from the column.

Diagram 2: DAD Optical Path

Comparative Advantages and Limitations in Practice

The different optical designs of VWD and DAD detectors lead to distinct advantages and limitations, which determine their suitability for various applications in drug development and research.

Table 2: Comparison of UV-VWD and DAD Detectors

| Feature | UV-Visible Detector (VWD) | Diode Array Detector (DAD/PDA) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Dispersion before the flow cell; sequential detection [15] | Dispersion after the flow cell; parallel detection [15] |

| Spectral Data | Measures absorbance at one or a few pre-selected wavelengths [1] | Measures the entire UV-Vis spectrum (190-800+ nm) in real-time [15] [1] |

| Sensitivity | Generally higher for a single, optimized wavelength due to greater light throughput [22] [8] | Slightly lower per wavelength but compensates with rich spectral data |

| Peak Identification | Based on retention time only [1] | Based on retention time and spectral matching [15] [1] |

| Peak Purity Assessment | Not possible, as co-eluting peaks go undetected if they absorb at the monitored wavelength | Excellent; software compares spectra across a peak to detect impurities [8] [1] |

| Method Development | Requires prior knowledge of analyte wavelengths | Ideal for unknowns; allows retrospective data analysis at different wavelengths [22] |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting a detector based on analytical goals.

Diagram 3: Detector Selection Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Drug Development

Detailed Methodology: Quantitation of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

The following protocol, adapted from a study on the antifungal drug Posaconazole, exemplifies a standard HPLC-DAD method for API quantification in a suspension dosage form [12].

1. Objective: To develop a sensitive, selective, and validated HPLC-DAD method for the quantitation of Posaconazole in bulk powder and a commercial oral suspension.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- API Standard: Posaconazole bulk powder.

- Internal Standard (IS): Itraconazole (structurally related compound).

- Mobile Phase: HPLC-grade acetonitrile and 15 mM potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (KHâ‚‚POâ‚„) buffer.

- Solvent: HPLC-grade methanol for sample and standard preparation.

- Equipment: HPLC system equipped with a binary pump, autosampler, thermostatted column compartment, and Diode Array Detector (DAD).

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC-DAD Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Specification | Role in the Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Zorbax SB-C18 Column | 4.6 x 250 mm, 5 µm particle size [12] | Stationary phase for reverse-phase separation of analytes. |

| Potassium Dihydrogen Orthophosphate | 15 mM aqueous solution, pH-adjusted [12] | Buffer component in mobile phase to control pH and improve peak shape. |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Organic modifier [12] | Mobile phase component to elute analytes from the C18 column. |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Solvent [12] | For preparing stock and working standard solutions. |

| Diode Array Detector (DAD) | Spectral scanning from 190-800 nm [12] [15] | Detection, quantification, and spectral confirmation of Posaconazole. |

3. Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Zorbax SB-C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm)

- Mobile Phase: Gradient elution from Acetonitrile:Buffer (30:70) to (80:20) over 7 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 1.5 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 25°C

- Injection Volume: 20 µL

- DAD Detection: 262 nm (quantitative wavelength), with continuous spectral acquisition from 200-400 nm for peak purity [12].

4. Sample Preparation:

- Standard Solutions: A 100 µg/mL stock solution of Posaconazole is prepared in methanol. Serial dilutions are made to prepare calibration standards ranging from 5-50 µg/mL.

- Suspension Dosage Form: 0.1 mL of the oral suspension (40 mg/mL) is diluted to 10 mL with methanol. An aliquot is centrifuged, and the supernatant is mixed with the internal standard (Itraconazole) and further diluted with methanol before injection [12].

5. Data Analysis:

- Quantification: A calibration curve of peak area (at 262 nm) versus concentration is constructed. The concentration of Posaconazole in the unknown suspension is calculated using the linear regression equation.

- Peak Purity and Identification: The UV spectrum of the Posaconazole peak in the sample is overlaid and compared with the spectrum from the standard using the DAD software. A high match (or purity index) confirms the identity and homogeneity of the peak, indicating no co-eluting impurities [12] [1].

Advanced Application: Peak Purity and Deconvolution with DAD

A powerful application of DAD is illustrated in the analysis of cannabinoids. Neutral cannabinoids (e.g., THC, CBD) and acidic cannabinoids (e.g., THCA, CBDA) have distinct UV spectral profiles due to their different chromophores. While they can be separated chromatographically, DAD provides a second dimension of confirmation. The DAD can collect the spectrum for each peak, allowing the analyst to distinguish between the neutral and acidic classes based on their characteristic λ_max and spectral shape, even without a perfect chromatographic separation [1].

Furthermore, advanced software functions like i-PDeA (intelligent Peak Deconvolution Analysis) can mathematically resolve co-eluting peaks. Since each compound has a unique UV spectrum, the detector can collect data from an unresolved chromatographic peak and, using the spectral information, deconvolute it to provide quantitative results for each individual component. This is a significant advantage over VWD, where co-elution might go entirely unnoticed or be misinterpreted as a single pure compound [1].

The detectability of a compound in UV-Vis spectroscopy is fundamentally governed by the presence of a chromophore with a sufficiently high molar absorptivity at an accessible wavelength. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between a UV spectrophotometer (VWD) and a Diode Array Detector (DAD) is a critical one that directly impacts the quality, reliability, and depth of analytical data. The VWD offers superior sensitivity and is a cost-effective workhorse for routine, targeted analyses where the analytes and their optimal wavelengths are well-characterized. In contrast, the DAD provides comprehensive spectral information that is indispensable for method development, peak purity analysis, and the confident identification of compounds in complex matrices. By understanding the principles of chromophores and the operational capabilities of these detectors, scientists can make informed decisions that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of their analytical methods, ultimately supporting robust drug development and quality control processes.

The evolution of ultraviolet (UV) detection systems for analytical chemistry represents a remarkable journey of technological innovation, transitioning from simple fixed-wavelength instruments to sophisticated diode array detectors capable of full-spectrum analysis. This whitepaper delineates the historical progression of UV detection technologies, examining the underlying principles, performance characteristics, and practical implications of each developmental stage. Framed within the context of distinguishing conventional UV spectrophotometers from modern diode array detectors (DAD), this analysis provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical reference. The critical operational distinctions between these detection modalities are explored through detailed experimental protocols, quantitative performance comparisons, and visualizations of optical pathways, offering practitioners a scientific basis for detector selection aligned with analytical requirements in regulated and research environments.

Ultraviolet detection technology has served as a cornerstone of analytical chemistry, particularly in high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), where it provides reliable, sensitive measurement of chromophoric compounds. The fundamental operating principle of all UV detectors relies on the Beer-Lambert Law, which establishes a linear relationship between analyte concentration and light absorption at specific wavelengths [8] [2]. This relationship enables both quantification and identification of substances based on their characteristic absorption patterns. The success of HPLC as a pervasive analytical technique in scientific discovery and quality control applications is largely attributable to the availability of sensitive and reliable UV detectors [8].

Within pharmaceutical development and quality control laboratories, UV detectors have maintained prominence despite the emergence of more sophisticated detection methods like mass spectrometry. This persistence is attributed to their exceptional reliability, ease of use, and universal response to chromophoric compounds, including most pharmaceuticals [8]. The technique's precision—typically achieving less than 0.2% relative standard deviation—makes it indispensable for regulatory testing where drug potency specifications often require demonstration of 98.0% to 102.0% purity [8]. Understanding the historical progression and technical distinctions between UV detector types is thus essential for optimal analytical method development.

Historical Progression of UV Detector Technologies

First Generation: Fixed Wavelength Detectors

The earliest UV detectors for HPLC emerged in the late 1960s and employed fixed wavelength configurations based on low-pressure mercury lamps with a strong emission line at 254 nm [8]. These pioneering instruments utilized simple cutoff filters to eliminate other high-order wavelengths from the source, providing a cost-effective but spectrally limited detection solution. Alternative wavelengths such as 280 nm or 265 nm could occasionally be accessed by adding phosphor to the source, while zinc lamps provided limited capacity for lower wavelength analyses around 214 nm [8].

The technical limitations of these early systems were significant, with reported noise specifications of approximately ±0.2 mAU—roughly 50 times less sensitive than modern detectors [8]. Despite these constraints, fixed wavelength detectors established UV detection as a viable approach for liquid chromatography and addressed many fundamental analytical needs of the period. Their simplicity and affordability contributed to early adoption of HPLC methodologies, particularly in academic and quality control environments where detection flexibility was secondary to reliability and cost considerations. Today, fixed wavelength UV detectors are found predominantly in low-cost or portable systems where analytical requirements remain specific and constrained [8].

Second Generation: Variable Wavelength Detectors

The 1980s witnessed a significant technological advancement with the introduction of variable wavelength detectors (VWD), also termed UV-visible (UV-vis) absorbance detectors [8]. These instruments represented a substantial improvement over fixed wavelength systems by incorporating a deuterium arc discharge lamp that provided continuous emission across the 190–600 nm UV-vis spectrum [8]. This expanded wavelength range enabled method development flexibility and improved analytical selectivity through wavelength optimization specific to target analytes.

The core innovation of variable wavelength detectors was the incorporation of a monochromator—an optical system consisting of an entrance slit, movable diffraction grating (or prism), and exit slit [8]. This configuration allowed users to select specific analytical wavelengths by rotating the motorized grating to direct desired wavelengths through the exit slit toward the flow cell. The transmitted light then impinged on a single photodiode that transformed light energy into electrical signals proportional to analyte concentration [8]. This design marked a significant advancement in detection flexibility, though it remained constrained to sequential wavelength monitoring rather than simultaneous multi-wavelength detection.

Table 1: Evolution of UV Detector Technologies

| Generation | Time Period | Light Source | Wavelength Selection | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Wavelength | Late 1960s | Low-pressure mercury lamp (254 nm) | Cutoff filters | Simplicity, low cost, reliability | Limited wavelength options, poor sensitivity (±0.2 mAU noise) |

| Variable Wavelength (VWD) | 1980s | Deuterium lamp (190-600 nm) | Monochromator with movable grating | Wavelength flexibility, improved selectivity | Sequential wavelength measurement only |

| Diode Array (DAD/PDA) | 1990s-present | Deuterium and tungsten lamps | Fixed grating with diode array | Full spectrum acquisition, peak purity assessment | Higher cost, greater complexity |

Third Generation: Diode Array Detectors (DAD)

A paradigm shift in UV detection occurred with the commercialization of photodiode array detectors (PDA), also known as diode array detectors (DAD) [8]. The pioneering instrument in this category, the Hewlett-Packard (HP) 8450A, revolutionized the field in the early 1980s by introducing diode array technology that enabled capture of a complete spectrum in a single measurement [23]. Unlike variable wavelength systems where the grating moves to select wavelengths, diode array detectors employ a fixed diffraction grating that simultaneously disperses the entire light spectrum after it passes through the sample onto a linear array of discrete photodiodes [24].

This fundamental reversal in optical geometry—placing the wavelength dispersion element after rather than before the sample—represents the core innovation of diode array technology [24]. Each photodiode in the array corresponds to a specific nanometer region of the spectrum, typically configured with 512 or 1024 elements, enabling simultaneous monitoring of all wavelengths [8]. This design eliminates moving parts from the optical path and facilitates rapid, full-spectrum acquisition in milliseconds to seconds, depending on instrument design [24]. The technological progression continued with instruments like the HP 8453 and Agilent Cary 8454, which refined the original concept with improved resolution and sensitivity [23].

Technical Comparison: UV Spectrophotometers vs. DAD Detectors

Optical Configurations and Operating Principles

The fundamental distinction between conventional UV spectrophotometers and diode array detectors lies in their optical configurations and sequence of analytical operations. Variable wavelength detectors employ a pre-sample monochromator configuration, where light from the source passes through the monochromator to select a specific wavelength before reaching the flow cell [8]. This design necessitates sequential wavelength measurement and limits data collection to predefined wavelengths of interest.

In contrast, diode array detectors utilize a post-sample dispersion architecture where polychromatic light passes through the sample before being separated into its constituent wavelengths by a fixed grating [24]. The dispersed light then strikes a photodiode array detector, enabling simultaneous measurement of all wavelengths across the UV-vis spectrum [1]. This fundamental difference in optical geometry confers distinct advantages for applications requiring rapid spectral acquisition or retrospective data analysis.

Diagram 1: Optical configurations of VWD and DAD systems

Performance Characteristics and Analytical Capabilities

The operational differences between conventional UV and DAD detectors translate to distinct performance characteristics and analytical capabilities. While both detector types adhere to the fundamental principles of UV absorption spectroscopy, their applications diverge significantly based on their respective technical strengths.

Variable Wavelength Detectors excel in routine quantitative analyses where method parameters are well-established and target analytes are known. Their optimized single-wavelength detection provides excellent signal-to-noise ratio for quantification and can achieve noise specifications below ±1.0 × 10â»âµ AU in advanced systems [8]. This makes them ideally suited for quality control environments where reliability, cost-effectiveness, and simplicity are prioritized over spectral information.

Diode Array Detectors offer expanded analytical capabilities through full-spectrum data acquisition. Key advantages include:

Peak Purity Assessment: By comparing UV spectra across different time points of a chromatographic peak (upslope, apex, and downslope), DAD enables detection of co-eluting compounds through spectral differences [8] [1]. This capability is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis for confirming analyte purity and detecting potential impurities.

Spectral Library Matching: Full UV-vis spectra serve as qualitative fingerprints for compound identification through comparison with reference standards [1]. While not as definitive as mass spectrometric identification, this provides a valuable orthogonal identification mechanism.

Post-analysis Data Interrogation: The collection of complete spectral data throughout the analysis enables retrospective method development and investigation of unexpected peaks without reinjection [1].

Multi-component Analysis: Advanced software capabilities, such as Shimadzu's i-PDeA function, leverage spectral differences to mathematically resolve co-eluting compounds through deconvolution algorithms [1].

Table 2: Analytical Capabilities Comparison Between VWD and DAD

| Analytical Parameter | Variable Wavelength Detector | Diode Array Detector |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Range | 190-600 nm (with deuterium lamp) | 190-900 nm (with supplemental tungsten) |

| Spectral Acquisition | Sequential single wavelengths | Simultaneous full spectrum |

| Peak Purity Assessment | Not available | Comprehensive via spectral comparison |

| Spectral Data | Limited to selected wavelengths | Complete UV-vis spectrum for all peaks |

| Method Development Flexibility | Limited; requires predefined wavelengths | Extensive; post-acquisition wavelength optimization |

| Co-elution Detection | Limited to chromatographic resolution | Spectral deconvolution capabilities |

| Quantitative Precision | <0.2% RSD [8] | <0.2% RSD [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Peak Purity Assessment Using Diode Array Detection

Principle: Peak purity assessment validates chromatographic peak homogeneity by comparing UV spectra acquired at different time points across the peak profile. Significant spectral variations suggest potential co-elution of impurities with the target analyte [1].

Materials:

- HPLC system equipped with diode array detector

- Suitable chromatographic column and mobile phase

- Reference standards of target analyte and potential impurities

- Data analysis software with peak purity algorithm

Methodology:

- Establish chromatographic conditions that provide baseline separation of all known related substances from the main peak.

- Configure DAD to acquire full UV spectra (typically 200-400 nm) throughout the chromatographic run with appropriate spectral resolution (1-2 nm).

- Inject sample solutions and acquire three-dimensional data (absorbance, wavelength, time).

- Using the instrument software, select multiple spectra from the target peak: typically at the upslope (10% peak height), apex (100% peak height), and downslope (10% peak height).

- Normalize the acquired spectra and apply the peak purity algorithm to calculate correlation coefficients between spectra.

- Interpret results: purity angle less than purity threshold generally indicates homogeneous peak [1].

Critical Parameters:

- Adequate signal-to-noise ratio (>100) for reliable spectral comparison

- Appropriate spectral normalization to correct for concentration effects

- Sufficient number of data points across the peak (≥20) for meaningful assessment

Wavelength Optimization for Variable Wavelength Detection

Principle: Maximizing analytical sensitivity and selectivity through systematic identification of optimal detection wavelength(s) for target analytes.

Materials:

- UV-vis spectrophotometer with scanning capability

- Standard solutions of target analytes at appropriate concentrations

- Matched quartz cuvettes or suitable solvent-matched reference

Methodology:

- Prepare standard solutions of target analytes in appropriate solvent at concentrations yielding absorbance values between 0.5-1.0 AU.

- Fill reference cell with pure solvent or blank solution.

- Scan samples across relevant UV range (typically 200-350 nm for pharmaceuticals).

- Identify wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for each analyte from the absorption spectrum.

- Evaluate potential interference from matrix components or other analytes at selected wavelengths.

- For multiple analyte detection, identify wavelengths that balance sensitivity and selectivity requirements, potentially employing multiple detection wavelengths for a single run.

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent transparency at selected wavelengths

- Spectral bandwidth appropriate for application (typically 1-2 nm for quantification)

- Verification of Beer-Lambert law linearity at selected wavelength

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for UV Detection Applications

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterium Lamp | Provides continuous UV spectrum (190-400 nm) | Typical lifetime 1000-2000 hours; replacement required when intensity drops [8] |

| Tungsten/Halogen Lamp | Extends detection to visible range (400-900 nm) | Often used complementarily with deuterium source in DAD systems [2] |

| Quartz Flow Cells | Sample containment for absorbance measurement | Standard pathlength 10 mm; UHPLC cells 0.5-1 µL volume [8] |

| Mobile Phase Filters | Removes particulate matter that causes light scattering | 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm membranes compatible with organic solvents |

| Reference Standards | Method calibration and peak identification | Certified reference materials with documented purity for quantitative work |

| Spectrophotometric Solvents | Sample dissolution and mobile phase preparation | UV-transparent solvents (ACN, MeOH, Hâ‚‚O) with minimal UV cutoff [2] |

| Flow Cell Seals | Maintains fluidic integrity of detection flow cell | Regular replacement prevents leaks and pressure fluctuations |

| Fluoflavine | Fluoflavine, MF:C14H10N4, MW:234.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lipid N2-3L | Lipid N2-3L, MF:C48H93N3O8, MW:840.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

UV detection technologies serve critical roles throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle, from early drug discovery through quality control of final dosage forms. Regulatory frameworks, including ICH guidelines, implicitly assume the use of UV detection for stability-indicating HPLC methods of drug substances and products, with sensitivity requirements in the 0.05–0.10% range for impurity detection [8]. Specific pharmaceutical applications include:

Identity Testing: UV spectrophotometry provides confirmation of drug substance identity through comparison of absorption spectra with reference standards, ensuring correct labeling and material identification [25] [5]. The characteristic wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) serves as a primary identity parameter in many pharmacopeial monographs.

Assay and Potency Determination: Quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) utilizing Beer-Lambert law relationships represents the most prevalent application of UV detection in pharmaceutical analysis [5]. The high precision achievable with modern UV detectors (<0.2% RSD) enables reliable potency determinations against strict specifications (typically 98.0–102.0%) [8].

Impurity Profiling: UV detectors provide sensitive detection and quantification of process-related impurities and degradation products in drug substances and products [5]. The normalized area-under-the-curve (AUC) values obtained with UV detection are often equated with purity percentages by weight in pharmaceutical quality control [8].

Dissolution Testing: UV spectrophotometry serves as the primary analytical technique for evaluating drug release from solid oral dosage forms in dissolution testing [25] [5]. The ability to rapidly quantify API concentration in dissolution media makes UV detection ideally suited for this high-throughput application.

Diagram 2: HPLC system configuration with detector options

The evolution of UV detection systems from fixed wavelength to modern diode array technology represents a continuous trajectory toward greater information density and analytical capability. While mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful complementary technique, UV detection maintains significant relevance in pharmaceutical analysis due to its exceptional reliability, quantitative precision, and regulatory acceptance [11]. The persistence of LC-UV/DAD methodologies, particularly in quality control environments, underscores the technique's enduring value for applications where established methods and cost-effectiveness are prioritized [11].

Future developments in UV detection technology will likely focus on integration with complementary detection modalities, miniaturization for portable applications, and enhanced data processing capabilities. Advanced algorithms for spectral deconvolution, such as Shimadzu's i-PDeA function that enables virtual separation of chromatographically unresolved peaks, represent the current forefront of DAD innovation [1]. Similarly, modern instruments like the Agilent Cary 3500 combine the rapid spectral acquisition of diode array systems with the high performance of double monochromator designs, eliminating traditional tradeoffs between speed and precision [23].