A Practical Framework for Systematic Error Estimation in Method Comparison Experiments

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on estimating and correcting systematic error (bias) in method comparison studies.

A Practical Framework for Systematic Error Estimation in Method Comparison Experiments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on estimating and correcting systematic error (bias) in method comparison studies. It covers foundational concepts distinguishing systematic from random error, details methodological approaches for study design and statistical analysis using techniques like Bland-Altman plots and regression, offers strategies for troubleshooting and bias mitigation, and outlines validation protocols and comparative frameworks. The content is designed to equip scientists with practical knowledge to ensure measurement accuracy, enhance data reliability, and maintain regulatory compliance in biomedical research and clinical settings.

Understanding Systematic Error: Definitions, Sources, and Impact on Measurement Validity

Defining Systematic Error (Bias) and Distinguishing it from Random Error

Fundamental Definitions and Core Concepts

In scientific research, measurement error is the difference between an observed value and the true value of a quantity. These errors are broadly categorized into two distinct types: systematic error (bias) and random error. Understanding their fundamental differences is crucial for assessing the quality of experimental data [1].

Systematic error, often termed bias, is a consistent or proportional difference between the observed and true values of something [1]. It is a fixed deviation that is inherent in each and every measurement, causing measurements to consistently skew in one direction—either always higher or always lower than the true value [2]. This type of error cannot be eliminated by repeated measurements alone, as it affects all measurements in the same way [2]. For example, a miscalibrated scale that consistently registers weights as 1 kilogram heavier than they are produces a systematic error [3].

Random error, by contrast, is a chance difference between the observed and true values that varies in an unpredictable manner when a large number of measurements of the same quantity are made under essentially identical conditions [2] [1]. Unlike systematic error, random error affects measurements equally in both directions (too high and too low) relative to the correct value and arises from natural variability in the measurement process [3]. An example includes a researcher misreading a weighing scale and recording an incorrect measurement due to fluctuating environmental conditions [1].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics that distinguish these two types of error.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Systematic and Random Error

| Characteristic | Systematic Error (Bias) | Random Error |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of Error | Consistent direction (always high or always low) [1] | Unpredictable direction (equally likely high or low) [3] |

| Impact on Results | Affects accuracy [1] | Affects precision [1] |

| Source | Problems with instrument calibration, measurement procedure, or external influences [4] | Unknown or unpredictable changes in the experiment, instrument, or environment [4] |

| Reduce via Repetition | No, it remains constant [2] | Yes, errors cancel out when averaged [1] |

| Quantification | Bias statistics in method comparison [5] | Standard deviation of measurements [3] |

The Impact on Measurement: Accuracy vs. Precision

The concepts of accuracy and precision are visually and functionally tied to the types of measurement error. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the true value, while precision refers to how reproducible the same measurement is under equivalent circumstances, indicating how close repeated measurements are to each other [1].

Systematic error primarily affects accuracy. Because it shifts all measurements in a consistent direction, the average of repeated measurements will be biased away from the true value [3]. Random error, on the other hand, primarily affects precision. It introduces variability or "scatter" between different measurements of the same thing, meaning repeated observations will not cluster tightly [1]. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these concepts.

Experimental Protocols for Estimating Systematic Error

The primary experimental design for estimating systematic error in analytical sciences and drug development is the method-comparison study. Its purpose is to determine if a new (test) method can be used interchangeably with an established (comparative) method without affecting patient results or clinical decisions [5] [6]. The core question is one of substitution: can one measure the same analyte with either method and obtain equivalent results? [5]

Key Design Considerations

A robust method-comparison study requires careful planning across several dimensions [7] [5] [6]:

- Selection of Comparative Method: An ideal comparative method is a reference method whose correctness is well-documented through definitive methods or traceable standards. This allows any observed differences to be attributed to the test method. In practice, many studies use a routine method already in clinical use, but large, medically unacceptable differences then require further investigation to identify which method is inaccurate [7].

- Sample Selection and Size: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended, though 100 or more is preferable to identify unexpected errors from interferences or sample matrix effects. The samples must cover the entire clinically meaningful measurement range, not just the analytical range. The quality of the experiment depends more on obtaining a wide range of values than simply a large number of results [7] [6].

- Timing and Replication: Specimens should be analyzed by both methods within a short time frame, ideally within two hours, to ensure specimen stability. The experiment should be conducted over multiple days (at least 5) and multiple analytical runs to capture real-world variability. While single measurements are common, performing duplicate measurements for both methods helps minimize the effects of random variation and identifies sample mix-ups or transposition errors [7] [6].

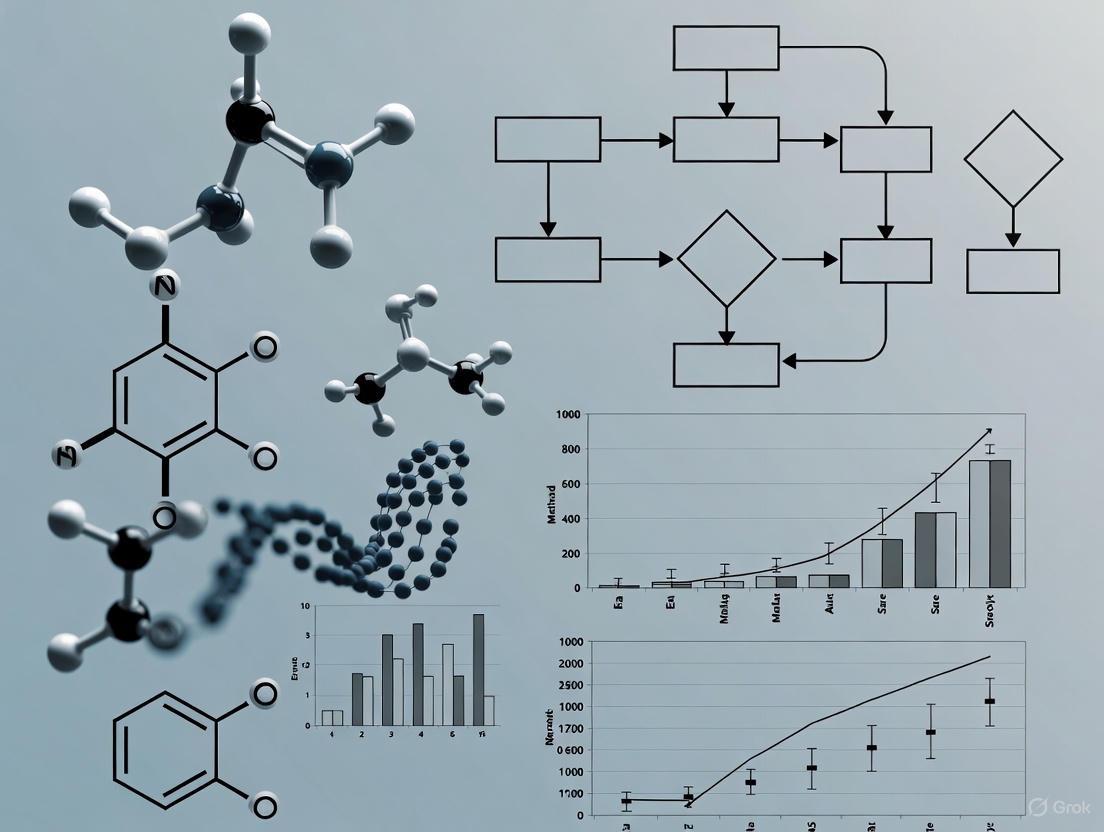

The workflow for a typical method-comparison experiment is outlined below.

Data Analysis and Visualization

The analysis of method-comparison data involves both graphical inspection and statistical quantification, moving beyond inadequate methods like correlation coefficients and t-tests, which cannot reliably assess agreement [6].

Graphical Inspection: The first and most fundamental step is to graph the data.

- Scatter Plots: A scatter diagram displays the test method results (y-axis) against the comparative method results (x-axis). This helps visualize the variability and linear relationship between methods across the measurement range [6].

- Difference Plots (Bland-Altman Plots): This is the recommended graphical method for assessing agreement. The plot displays the average of the two methods [(Test + Comparative)/2] on the x-axis and the difference between them (Test - Comparative) on the y-axis. This plot allows for visual inspection of the bias (the average difference) and how the differences vary across the measurement range [5].

Statistical Quantification:

- For a Wide Analytical Range: Use linear regression analysis (e.g., Deming or Passing-Bablok regression) to obtain the slope and y-intercept of the line of best fit. The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated as:

Yc = a + b*Xc, thenSE = Yc - Xc[7]. This helps identify proportional (slope) and constant (intercept) errors. - For a Narrow Analytical Range: Calculate the bias (mean difference) and the limits of agreement. The bias is the average of all individual differences (test method - comparative method). The limits of agreement are defined as

Bias ± 1.96 * Standard Deviation of the differences, representing the range within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are expected to lie [5].

- For a Wide Analytical Range: Use linear regression analysis (e.g., Deming or Passing-Bablok regression) to obtain the slope and y-intercept of the line of best fit. The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated as:

Table 2: Key Statistical Outputs in Method-Comparison Studies

| Statistical Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Regression Slope (b) | The change in the test method per unit change in the comparative method [7]. | b = 1: No proportional error.b > 1: Positive proportional error.b < 1: Negative proportional error. |

| Regression Intercept (a) | The constant difference between the methods [7]. | a = 0: No constant error.a > 0: Positive constant error.a < 0: Negative constant error. |

| Bias (Mean Difference) | The overall average difference between the two methods [5]. | Quantifies how much higher (positive) or lower (negative) the test method is compared to the comparative method. |

| Limits of Agreement (LOA) | Bias ± 1.96 SD of differences [5]. | The range where 95% of differences between the two methods are expected to fall. Used to judge clinical acceptability. |

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Method-Comparison Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Substances with one or more properties that are sufficiently homogeneous and well-established to be used for instrument calibration or method validation. Serves as an anchor for trueness [2]. |

| Patient-Derived Specimens | A panel of well-characterized clinical samples (serum, plasma, etc.) that cover the pathological and analytical range of interest. Essential for assessing performance with real-world matrix effects [7]. |

| Quality Control Materials | Stable materials with known assigned values, used to monitor the precision and stability of the measurement procedure during the comparison study over multiple days [7]. |

| Statistical Software Packages | Software (e.g., MedCalc, R, specialized CLSI tools) capable of performing Deming regression, Bland-Altman analysis, and calculating bias and limits of agreement, which are essential for proper data interpretation [5]. |

In research, systematic errors are generally considered a more significant problem than random errors [1] [3]. Random error introduces noise, but with a large sample size, the errors in different directions tend to cancel each other out when averaged, leaving an unbiased estimate of the true value [1]. Systematic error, however, introduces a consistent bias that is not reduced by repetition or larger sample sizes. It can therefore lead to false conclusions about the relationship between variables (Type I or II errors) and skew data in a way that compromises the validity of the entire study [1]. Consequently, the control of systematic error is a significant element in discussing a study's report and a key criterion for assessing its scientific value [8].

In the context of method comparison experiments, systematic error, often referred to as bias, represents a consistent, reproducible deviation of test results from the true value or from an established reference method's results [9]. Unlike random error, which scatters measurements unpredictably, systematic error skews all measurements in a specific direction, thus compromising the trueness of an analytical method [10]. The accurate estimation and management of these errors are foundational to method validation, ensuring that laboratory results are clinically reliable and that patient care decisions are based on sound data.

Systematic errors are particularly problematic in research and drug development because they can lead to false positive or false negative conclusions about the relationship between variables or the efficacy of a treatment [1]. In a method comparison experiment, the primary goal is to identify and quantify the systematic differences between a new (test) method and a comparative method. Any observed differences are critically interpreted based on the known quality of the comparative method; if a high-quality reference method is used, errors are attributed to the test method [7].

Systematic errors in laboratory and clinical measurements can originate from numerous aspects of the analytical process. Understanding their nature is the first step toward implementing effective detection and correction strategies.

Fundamental Classifications: Constant and Proportional Bias

Systematic errors manifest in two primary, quantifiable forms, which are often investigated during method comparison studies using linear regression analysis [9]:

- Constant Error (Offset Error): This is a consistent difference between the test and comparative methods that remains the same across the concentration range of the analyte. It is represented by the y-intercept (

a) in a linear regression equation (Y = a + bX). For example, a miscalibrated zero point on an instrument would introduce a constant error [1] [9]. - Proportional Error (Scale Factor Error): This error changes in proportion to the analyte's concentration. It is represented by the slope (

b) in the linear regression equation. A miscalibration in the scale factor of an instrument, such as a faulty calibration curve, is a typical cause [1] [9].

Table 1: Classification of Systematic Errors (Bias)

| Type of Bias | Description | Common Causes | Representation in Regression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Bias | A fixed difference that is consistent across the measurement range. | Improper instrument zeroing, sample matrix effects, or specific interferents. | Y-Intercept (a) |

| Proportional Bias | A difference that increases or decreases proportionally with the analyte concentration. | Errors in calibration slope, incorrect reagent concentration, or instrument drift. | Slope (b) |

The following diagram illustrates how these biases affect measurement results in a method comparison context.

The sources of systematic error span the entire testing pathway, from specimen collection to data analysis.

- Specimen-Related Issues: The sample matrix itself can be a significant source of error. Sample matrix effects occur when components of the specimen interfere with the assay, leading to erroneous results that may not occur with control materials [10]. Improper sample handling, such as prolonged storage at room temperature for unstable analytes (e.g., ammonia), can also introduce bias [7].

- Calibration and Instrumentation: Uncalibrated or miscalibrated instruments are a classic source of both constant and proportional bias [1] [10]. A failure in the traceability chain, where the calibration of a routine method cannot be traced back to a higher-order reference method or material, guarantees a systematic error in patient results [10].

- Reagents and Assay Specificity: Deteriorated or improperly prepared reagents can lead to consistently biased results. Furthermore, an assay may lack perfect specificity, meaning it partially measures substances other than the intended analyte, such as metabolites or structurally similar drugs, leading to a positive bias [10].

- Environmental and Operator Factors: Experimenter drift is a phenomenon where an operator's technique slowly changes over time due to fatigue or loss of motivation, leading to a gradual introduction of bias [1]. Consistent misinterpretation of protocols or data entry errors by a specific individual are also forms of operator-induced systematic error.

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Systematic Error

A well-designed method comparison experiment is the cornerstone for detecting and quantifying systematic error. The following protocol outlines the key steps.

Protocol: The Comparison of Methods Experiment

Purpose: To estimate the inaccuracy or systematic error of a new test method by comparing it to a comparative method using real patient specimens [7].

Experimental Design:

- Selection of Comparative Method: Whenever possible, a reference method with documented correctness through traceability to definitive methods or reference materials should be used. If a routine method is used, differences must be interpreted with caution, as it may not be possible to determine which method is at fault [7].

- Specimen Selection and Number:

- A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended, selected to cover the entire working range of the method [7].

- Specimens should represent the spectrum of diseases and conditions expected in routine practice. Twenty carefully selected specimens covering a wide range may provide better information than 100 random specimens [7].

- For highly specific assessments, 100-200 specimens may be needed to evaluate whether the new method's specificity matches the comparative method [7].

- Measurement Process:

- Specimens should be analyzed by both methods within a short time frame (e.g., two hours) to minimize changes in the specimen [7].

- The experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 different days to account for run-to-run variability and to detect long-term systematic errors. Integrating the comparison with a long-term replication study over 20 days is preferable [7].

- While single measurements are common, performing duplicate measurements on different samples or in different analytical orders helps identify sample mix-ups or transposition errors and confirms the validity of discrepant results [7].

Data Analysis:

- Graphical Inspection: The first step is to graph the data. A difference plot (Bland-Altman-type plot) showing the difference between methods (test minus comparative) versus the comparative method's result is ideal for visualizing one-to-one agreement. This helps identify outliers and patterns of constant or proportional error [7].

- Statistical Calculations:

- For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression analysis (e.g., ordinary least squares) is used to calculate the slope (

b), y-intercept (a), and the standard error of the estimate (sy/x) [7] [9]. - The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (

Xc) is calculated as:Yc = a + b*Xc, thenSE = Yc - Xc[7]. - The correlation coefficient (r) is useful for assessing whether the data range is wide enough for reliable regression estimates; an

r < 0.99suggests the need for more data or alternative statistical approaches [7]. - For a narrow analytical range, calculating the average difference (bias) between the two methods via a paired t-test is often more appropriate [7].

- For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression analysis (e.g., ordinary least squares) is used to calculate the slope (

Alternative Protocol: Quality Control for Systematic Error Detection

Purpose: To continuously monitor for the presence of systematic error using control samples with known values [9].

Experimental Design:

- Use of Certified Reference Materials: Control samples with certified concentrations are analyzed with each analytical run [9].

- Levey-Jennings Plots: The control values are plotted on a Levey-Jennings chart over time, with control lines indicating the mean and standard deviations (e.g., ±1SD, ±2SD, ±3SD) established through a prior replication study [9].

- Application of Westgard Rules: Systematic control rules are applied to identify bias. These include [9]:

- 2

2sRule: Bias is indicated if two consecutive control values exceed the 2SD limit on the same side of the mean. - 4

1sRule: Bias is indicated if four consecutive control values exceed the 1SD limit on the same side of the mean. - 10

xRule: Bias is indicated if ten consecutive control values fall on the same side of the mean.

- 2

The workflow for this quality control process is depicted below.

Comparison of Detection and Quantification Methods

Different techniques offer varying strengths in detecting and quantifying systematic error. The choice of method depends on the stage of method validation (initial vs. ongoing) and the nature of the data.

Table 2: Comparison of Systematic Error Detection Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Quantitative Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method Comparison Experiment | Initial method validation and verification. | Uses real patient samples; estimates error at medical decision levels; characterizes constant/proportional error. | Labor-intensive; requires a carefully selected comparative method. | Slope, Intercept, Systematic Error (SE) at Xc |

| Levey-Jennings / Westgard Rules | Ongoing internal quality control. | Real-time monitoring; easy to implement and interpret; rules are tailored for specific error types. | Relies on stability of control materials; may not detect all matrix-related errors. | Qualitative (Accept/Reject Run) or violation patterns |

| Average of Normals / Moving Averages | Continuous monitoring using patient data. | Uses real patient samples; can detect long-term, subtle shifts; no additional cost for controls. | Requires sophisticated software; assumes a stable patient population. | Moving average value and control limits |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following materials are critical for conducting robust method comparison studies and controlling for systematic error.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systematic Error Estimation

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Higher-order materials with values assigned by a definitive method. Used to establish traceability and assess the trueness of the test method [10]. |

| Commercial Control Samples | Stable, pooled specimens with assigned target values. Used for daily quality control to monitor the stability of the analytical process and detect systematic shifts [10]. |

| Panel of Patient Specimens | A carefully selected set of 40-100 fresh patient samples covering the clinical reportable range. Essential for the comparison of methods experiment to assess performance across real-world matrices [7]. |

| Calibrators | Materials of known concentration used to adjust the instrument's response to establish a calibration curve. Their traceability is paramount to minimizing systematic error [10]. |

| Interference Check Samples | Solutions containing potential interferents (e.g., bilirubin, hemoglobin, lipids). Used to test the specificity of the method and identify positive bias caused by interference [10]. |

Strategies for Mitigation and Correction

Once a systematic error is identified and quantified, several strategies can be employed to mitigate or correct it.

- Calibration and Traceability: The most direct correction for a quantified bias is to apply a correction factor derived from the method comparison or recovery experiment. Ensuring that all calibrators are traceable to higher-order reference methods and materials, as per the ISO 17511 standard, is a fundamental preventative strategy [10].

- Method Improvement: If the source of error is identified, such as a specific interferent, the method protocol can be modified to eliminate it, for example, by introducing a purification step or using a more specific antibody [10].

- Triangulation: Using multiple techniques or instruments to measure the same analyte can help identify and correct for biases inherent in any single method [1].

- Regular Training and Standardization: Comprehensive training and calibration of all personnel involved in data collection and analysis reduces operator-dependent systematic errors. Standardizing protocols across all operators and sites is crucial [1] [11].

- Process Control: Implementing robust systems for specimen handling, storage, and processing can minimize pre-analytical sources of systematic error [7] [12].

The Impact of Uncorrected Bias on Data Integrity and Clinical Decision-Making

In laboratory medicine and clinical research, every measurement possesses a degree of uncertainty termed "error," which represents the difference between a measured value and the true value [9]. Systematic error, also known as bias, is a particularly challenging form of measurement error because it is reproducible and consistently skews results in the same direction, unlike random errors which follow a Gaussian distribution and can be reduced through repeated measurements [9]. Uncorrected systematic bias directly compromises data integrity by creating reproducible inaccuracies that cannot be eliminated through averaging or increased sample sizes, ultimately leading to flawed clinical decisions based on distorted evidence.

The growing integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare introduces new dimensions to the challenge of systematic bias. AI systems trained on biased datasets risk exacerbating health disparities, particularly when these systems demonstrate differential performance across patient demographics [13] [14]. In high-stakes clinical environments, opaque "black box" AI algorithms can compound these issues by making it difficult for healthcare professionals to interpret diagnostic recommendations or identify underlying biases [14]. These challenges necessitate robust methodological approaches for detecting, quantifying, and correcting systematic errors across both traditional laboratory medicine and emerging AI-assisted clinical decision-making.

Fundamental Classification of Biases

Table 1: Categories and Characteristics of Systematic Bias

| Bias Category | Definition | Common Sources | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Bias | Fixed difference between observed and expected values throughout measurement range | Instrument calibration errors, background interference | Consistent offset across all measurements |

| Proportional Bias | Difference between observed and expected values that changes proportionally with analyte concentration | Sample matrix effects, reagent degradation | Error magnitude increases with concentration |

| Algorithmic Bias | Systematic errors in AI/ML models leading to unfair outcomes for specific groups | Non-representative training data, flawed feature selection | Exacerbated health disparities, inaccurate predictions for minorities [13] [14] |

| Data Integrity Bias | Errors introduced through flawed data collection or processing | EHR inconsistencies, problematic data harmonization [13] | Compromised dataset quality affecting all downstream analyses |

In traditional laboratory settings, systematic errors frequently originate from instrument calibration issues, reagent degradation, or sample matrix effects that create either constant or proportional biases in measurements [9]. These technical biases can often be detected through method comparison studies using certified reference materials with known analyte concentrations.

The integration of artificial intelligence in healthcare introduces novel bias sources. AI systems fundamentally depend on their training data, and when this data originates from de-identified electronic health records (EHR) riddled with inconsistencies, the resulting models inherit and potentially amplify these flaws [13]. Additionally, algorithmic design choices and feature selection biases can create systems that perform unequally across patient demographics, particularly for underrepresented populations who may be inadequately represented in training datasets [14]. Healthcare professionals have reported instances where AI algorithms underperformed for minority patient groups or when identifying atypical presentations, raising serious concerns about fairness and reliability [14].

Detection Methodologies for Systematic Bias

Traditional Laboratory Detection Methods

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Bias Detection

| Methodology | Protocol Description | Key Statistical Measures | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison of Methods Experiment | Analyze ≥40 patient specimens by both test and comparative methods across multiple runs [7] | Linear regression (slope, y-intercept), systematic error estimation at medical decision points [7] | Laboratory method validation, instrument comparison |

| Levey-Jennings Plotting with Westgard Rules | Plot quality control measurements over time with control limits based on replication studies [9] | 2₂S rule, 4₁S rule, 10ₓ rule for systematic error detection [9] | Daily quality control monitoring |

| Statistical Process Control | Analyze patient results as "Average of Normals" or "Moving Patient Averages" [9] | Mean, standard deviation, trend analysis | Continuous bias monitoring using patient data |

Advanced and AI-Focused Detection Approaches

For AI-assisted healthcare tools, detection methodologies must address unique challenges. Bias audits using established open-source tools like IBM's AI Fairness 360 provide structured approaches to identify algorithmic disparities [13]. These tools can help quantify differential performance across patient demographics and identify potential fairness issues before clinical deployment.

The establishment of AI Ethics Boards modeled after Northeastern University's approach, which incorporates 40 ethicists and community members to review AI initiatives, represents an organizational approach to bias detection [13]. Similar to Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), these multidisciplinary committees can evaluate AI-based tools before implementation and incorporate diverse community perspectives to ensure adequate representation in care decisions [13]. Additionally, privacy-preserving techniques such as federated learning, implemented in projects like Europe's FeatureCloud, enable multi-institutional collaboration on model development without compromising patient privacy, potentially expanding dataset diversity [13].

Figure 1: Systematic Bias Detection Workflow. This diagram illustrates complementary approaches for identifying systematic errors in both traditional laboratory settings and AI-assisted healthcare tools.

Impact on Data Integrity and Clinical Outcomes

Data Integrity Compromises

Uncorrected systematic bias fundamentally undermines data integrity through several mechanisms. In laboratory medicine, both constant and proportional biases create reproducible inaccuracies that distort the relationship between measured values and true biological states [9]. When these biased measurements inform clinical decisions, the integrity of the entire decision-making process becomes compromised.

In AI-assisted healthcare, biased algorithms can systematically underperform for minority populations when trained on non-representative datasets, creating a form of digital discrimination that healthcare professionals find particularly concerning [14]. The "black box" nature of many complex AI models exacerbates these issues by making it difficult to identify the root causes of biased outcomes, creating transparency challenges that further erode data integrity [14]. When biased algorithms influence clinical workflows, the resulting decisions may reflect systemic inequities rather than objective clinical assessments.

Consequences for Clinical Decision-Making

The downstream effects of uncorrected bias on clinical decision-making can be profound. Healthcare professionals report reduced trust in AI-assisted decisions when they perceive potential biases, particularly for complex cases or rare conditions where algorithmic performance may be uncertain [14]. This trust erosion becomes especially problematic when biased triage recommendations during resource scarcity, such as that experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially disadvantage vulnerable patient populations [13].

Perhaps most concerning are situations where statistical errors in published literature remain uncorrected despite reader requests, as this prevents clinicians from basing their decisions on accurate evidence [15]. When such errors affect practice guidelines, they can influence care standards for numerous patients before the inaccuracies are identified and addressed.

Mitigation Strategies and Regulatory Considerations

Technical and Operational Mitigations

Several strategic approaches can mitigate the impact of systematic bias on data integrity and clinical decision-making:

Enhanced Dataset Development: Initiatives like the National Clinical Cohort Collaborative (N3C), which harmonizes data from over 75 institutions, provide templates for creating more inclusive datasets that better represent diverse patient populations [13]. Similarly, the All of Us Research Program aims to develop a nationwide database reflecting broader demographic diversity, though challenges of scale and speed remain [13].

Privacy-Preserving Collaboration: Techniques such as federated learning enable multi-institutional model development without centralizing sensitive patient data, as demonstrated by Google's Android, Apple's iOS, and Europe's FeatureCloud project [13]. These approaches facilitate broader data representation while maintaining privacy protections.

Continuous Monitoring Systems: Implementing post-deployment monitoring with continuous audit mechanisms, inspired by the Federal Aviation Administration's black boxes or the FDA's Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), can help detect and address failures in real-time [13]. Without such systems, troubleshooting biased AI systems in high-stakes clinical settings becomes extremely difficult.

Regulatory Frameworks and Future Directions

Regulatory agencies are increasingly focusing on bias mitigation in healthcare technologies. The FDA's draft regulatory pathway for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan provides a starting point for regulatory oversight, though agencies like HHS and CMS have yet to adopt similar comprehensive regulations [13]. The upcoming ICH E6(R3) guidelines, expected in 2025, will emphasize data integrity and traceability with greater scrutiny on data management practices throughout the research lifecycle [16].

Future regulatory innovation should address accountability gaps in AI-assisted decision-making, where healthcare professionals feel ultimately liable for patient outcomes while simultaneously relying on opaque algorithmic insights [14]. Clearer regulatory frameworks that define responsibility across developers, clinicians, and institutions will be essential for building trust in increasingly automated healthcare systems.

Figure 2: Clinical Impact Pathway of Uncorrected Bias. This diagram illustrates how systematic errors propagate through data systems to ultimately affect patient outcomes.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bias Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Bias Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provide known values for method comparison studies to quantify systematic error [9] | Laboratory method validation, instrument calibration |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitor analytical performance over time using Levey-Jennings plots and Westgard rules [9] | Daily quality control, bias trend detection |

| AI Fairness 360 Toolkit | Open-source library containing metrics to test for biases in AI models and datasets [13] | Algorithmic bias detection in healthcare AI |

| Diverse Biobank Specimens | Provide representative samples across demographics to test for population-specific biases | Bias assessment in diagnostic assays and AI models |

| Standardized EHR Data Templates | Facilitate interoperable, consistent data collection to reduce structural biases [13] | Healthcare dataset creation and harmonization |

Uncorrected systematic bias represents a fundamental challenge to data integrity and clinical decision-making across both traditional laboratory medicine and emerging AI-assisted healthcare. The consistent, reproducible nature of systematic errors means they cannot be eliminated through statistical averaging alone, requiring instead targeted detection methodologies and proactive mitigation strategies. As healthcare becomes increasingly dependent on complex algorithms and large-scale data analysis, maintaining vigilance against systematic bias becomes ever more critical for ensuring equitable, evidence-based patient care.

The path forward requires collaborative effort across multiple stakeholders—clinicians, laboratory professionals, AI developers, regulators, and patients—to develop comprehensive approaches to bias detection and mitigation. Through enhanced dataset diversity, robust methodological frameworks, continuous monitoring systems, and thoughtful regulatory oversight, the healthcare community can work toward minimizing the impact of systematic errors on both data integrity and the clinical decisions that shape patient outcomes.

In scientific research and drug development, the validity of quantitative data hinges on a clear understanding of core measurement concepts. Accuracy, precision, trueness, and measurement uncertainty are distinct but interrelated properties that characterize the quality and reliability of measurement results. Within the context of method comparison experiments, these concepts provide the framework for estimating systematic errors and determining whether a new analytical method is fit for its intended purpose. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) provide standardized definitions and methodologies for evaluating these parameters, ensuring consistency and comparability across laboratories and scientific studies [17].

This guide objectively compares these fundamental concepts, delineating their roles in systematic error estimation. We present structured experimental data, detailed protocols for method comparison studies, and visualizations of their logical relationships, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to critically assess measurement performance.

Defining the Concepts

Precision: The Measure of Dispersion

Precision describes the closeness of agreement between independent measurement results obtained under stipulated conditions [18] [19]. It is a measure of dispersion or scatter and is typically quantified by measures such as standard deviation or variance. High precision indicates low random error and high repeatability, meaning repeated measurements cluster tightly together. However, precision alone says nothing about a measurement's closeness to a true value; a method can be highly precise yet consistently wrong [18] [20].

- Factors Affecting Precision: Random errors, which are unpredictable fluctuations, influence precision. These can arise from environmental variations (e.g., temperature, humidity), electronic noise in instruments, or operator technique [18] [17] [19].

- Quantification: In a series of repeated measurements, precision is often expressed as the standard deviation. A smaller standard deviation indicates higher precision.

Trueness: The Proximity to a True Value

Trueness refers to the closeness of agreement between the average value of a large series of measurement results and a true or accepted reference value [18]. Unlike precision, which concerns scatter, trueness concerns the central tendency of the data. It provides information about how far the average of your measurements is from the real value and is a qualitative expression of systematic error, or bias [18] [17].

- Systematic Errors: The cause of low trueness is systematic error. These errors are consistent, predictable, and often stem from the measuring device itself or a biased procedure [18] [17]. For example, a scale that consistently reads 1 gram too high has a systematic error.

- Reference Value: Determining trueness requires a reference value, which is often established through calibration using a traceable standard [18].

Accuracy: The Combination of Trueness and Precision

Accuracy describes the closeness of a single measurement result to the true value [18] [21] [20]. It is the overarching goal in most measurements. A measurement is considered accurate only if it is both true (has low systematic error) and precise (has low random error). In other words, accuracy incorporates the effects of both trueness and precision [18].

To have high accuracy, a series of measurements must be both precise and true. Therefore, high accuracy means that each measurement value, not just the average of the measurements, is close to the real value [18]. The accuracy of a measuring device is often given as a percentage, indicating the maximum expected deviation from the true value under specified conditions [18].

Measurement Uncertainty: A Quantitative Statement of Doubt

Measurement uncertainty is a non-negative parameter characterizing the dispersion of the quantity values being attributed to a measurand [17]. In simpler terms, it is a quantitative statement about the doubt associated with a measurement result. Every measurement is subject to error, and uncertainty provides an interval around the measured value within which the true value is believed to lie with a certain level of confidence [17] [22] [23].

Uncertainty does not represent error itself but quantifies the reliability of the result. It is typically expressed as a combined standard uncertainty or an expanded uncertainty (e.g., ±0.03%) and encompasses contributions from both random effects (precision) and imperfect corrections for systematic effects (trueness) [18] [17]. As stated in the GUM, a measurement result is complete only when accompanied by a quantitative statement of its uncertainty [17].

Visualizing the Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between a true value, systematic error (influencing trueness), random error (influencing precision), and their combined effect on accuracy and measurement uncertainty.

Diagram 1: Relationship between measurement concepts. Systematic and random errors influence the measured value. Trueness and Precision are inversely related to these errors, respectively. Both are components of Accuracy, which itself is inversely related to Measurement Uncertainty.

Quantitative Comparison of Concepts

The table below provides a structured comparison of the four key concepts, summarizing their definitions, what they are influenced by, and how they are typically quantified.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Metrological Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Influenced By | Quantified By | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between repeated measurements [18] [19]. | Random errors [17]. | Standard Deviation (SD), Variance, Coefficient of Variation (CV) [17]. | ||

| Trueness | Closeness of the mean of measurement results to a true/reference value [18]. | Systematic errors (bias) [18] [17]. | Bias (mean - reference value) [18] [7]. | ||

| Accuracy | Closeness of a single measurement result to the true value [18] [21]. | Combined effect of both systematic and random errors [18]. | Total Error (often estimated as | Bias | + 2*SD) [24]. |

| Measurement Uncertainty | Parameter characterizing the dispersion of values attributable to a measurand [17]. | All sources of error (random and systematic) [17]. | Combined Standard Uncertainty, Expanded Uncertainty (e.g., ±0.03%) [18] [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Error Estimation

The comparison of methods experiment is a critical study designed to estimate the systematic error (bias) between a new test method and a established comparative method using real patient specimens [7]. The following provides a detailed protocol for executing this experiment.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key stages in a method comparison experiment, from planning and specimen preparation to data analysis and estimation of systematic error.

Diagram 2: Method comparison experiment workflow.

Detailed Methodologies

- Comparative Method Selection: The choice of comparative method is crucial. A reference method with documented correctness is ideal, as any differences can be attributed to the test method. When using a routine method as a comparative method, differences must be interpreted carefully, and additional experiments (e.g., recovery, interference) may be needed to identify which method is inaccurate [7].

- Specimen Selection and Handling: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended. These should be carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the spectrum of diseases expected in routine use [7]. Specimens should be analyzed by both methods within two hours of each other to avoid stability issues, unless specific preservatives or handling procedures (e.g., freezing) are validated [7].

- Measurement Protocol: Specimens should be analyzed over a minimum of 5 days, and ideally over a longer period (e.g., 20 days) to capture long-term sources of variation. While single measurements are common practice, performing duplicate measurements on different sample cups or in different analytical runs is advantageous as it helps identify sample mix-ups or transposition errors [7].

- Data Analysis and Systematic Error Estimation:

- Graphical Analysis: The data should first be graphed for visual inspection. A difference plot (test result minus comparative result vs. comparative result) is used when methods are expected to agree one-to-one. A comparison plot (test result vs. comparative result) is used otherwise. This helps identify outliers and the general relationship between methods [7].

- Statistical Calculations:

- For a wide analytical range (e.g., glucose, cholesterol), linear regression (Y = a + bX) is used. The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated as: Yc = a + bXc, then SE = Yc - Xc [7].

- For a narrow analytical range (e.g., sodium, calcium), the average difference (bias) between the two methods is calculated using a paired t-test. The standard deviation of the differences describes the distribution of these differences [7].

- Correlation Coefficient: The correlation coefficient (r) is more useful for assessing whether the data range is wide enough to provide reliable regression estimates (r ≥ 0.99 is desirable) than for judging method acceptability [7].

Advanced Considerations in Systematic Error

Decomposing Systematic Error: Constant and Variable Bias

Traditional models often treat systematic error (bias) as a single, fixed value. However, recent research proposes decomposing bias into two components [24]:

- Constant Component of Systematic Error (CCSE): A stable, correctable offset.

- Variable Component of Systematic Error (VCSE(t)): A time-dependent function that behaves unpredictably over an extended period and cannot be efficiently corrected.

This distinction is critical because the standard deviation (s~RW~) derived from long-term quality control (QC) data includes contributions from both random error and the variable bias component. Using s~RW~ as a sole estimator of random error can lead to an overestimation of method precision and miscalculations of total error [24]. This refined model challenges the assumption that long-term QC data are normally distributed and has significant implications for accurately estimating measurement uncertainty.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Comparison Studies

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a traceable, true value for establishing trueness and calibrating instruments [17] [7]. |

| Stable Quality Control (QC) Pools | Monitors the stability and precision of the measurement method over time, helping to identify drift [7] [24]. |

| Patient Specimens | Serves as the core test material for comparison experiments, ensuring the evaluation covers realistic biological matrices and concentration ranges [7]. |

| Calibrators | Used to adjust the analytical output of the instrument to match the reference scale, directly addressing systematic error [7] [19]. |

In systematic error estimation for method comparison experiments, a clear demarcation between precision, trueness, accuracy, and measurement uncertainty is non-negotiable. Precision assesses random variation, trueness quantifies systematic bias, and accuracy encompasses both. Measurement uncertainty then provides a quantitative boundary for the doubt associated with any result, integrating all error components.

Advanced understanding, such as decomposing systematic error into constant and variable parts, allows for more sophisticated quality control models and accurate uncertainty budgets. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorously applying these concepts and the associated experimental protocols ensures that analytical methods are fit for purpose, supporting the generation of reliable and defensible data critical for scientific discovery and patient safety.

Systematic error, or bias, is defined as the systematic deviation of measured results from the actual value of the quantity being measured [25]. In the context of method comparison experiments, understanding bias is crucial because it directly impacts the interpretation of laboratory results and can lead to misdiagnosis or misestimation of disease prognosis when significant [25]. Bias represents one of the most important metrological characteristics of a measurement procedure, and its accurate estimation is fundamental for ensuring reliability in scientific research and drug development.

Systematic error can be categorized into different types based on its behavior across concentration levels. The two primary forms discussed in this guide are constant bias and proportional bias, which differ in how they manifest across the analytical measurement range [26] [25]. Proper identification of which type of bias is present, or whether both exist simultaneously, is essential for determining the appropriate correction strategy and assessing method acceptability [7]. This guide provides researchers with the experimental frameworks and statistical tools necessary to distinguish between these bias types accurately, supported by practical data analysis and visualization techniques.

Theoretical Foundations of Bias Types

Constant Bias

Constant bias occurs when one measurement method consistently yields values that are higher or lower than those from another method by a fixed amount, regardless of the analyte concentration [26] [27]. This type of bias manifests as a consistent offset between methods across the entire measurement range. In statistical terms, when comparing two methods using regression analysis, constant bias is represented by the intercept (b) in the regression equation y = ax + b [25]. If the confidence interval for this intercept does not include zero, a statistically significant constant bias is present [26].

Visual inspection of method comparison data reveals constant bias as a parallel shift between the line of best fit and the line of identity [26]. For example, if a new method consistently produces results that are 5 units higher than the reference method across all concentration levels—from very low to very high values—this represents a positive constant bias. The difference between methods remains approximately the same absolute value regardless of the concentration being measured.

Proportional Bias

Proportional bias exists when the difference between methods changes in proportion to the analyte concentration [26] [25]. Unlike constant bias, the magnitude of proportional bias increases or decreases as the level of the measured variable changes. This type of bias indicates that the discrepancy between methods is concentration-dependent [27].

In regression analysis, proportional bias is detected through the slope (a) in the equation y = ax + b [25]. If the confidence interval for the slope does not include 1, a statistically significant proportional bias is present [25]. Proportional bias can be either positive (the difference between methods increases with concentration) or negative (the difference decreases with concentration) [26]. Visual evidence of proportional bias appears as a gradual divergence between the line of best fit and the line of identity as concentration increases, creating a fan-like pattern in the difference plot.

Combined Bias Effects

In practice, methods can exhibit both constant and proportional bias simultaneously [26]. This combined effect occurs when there is both a fixed offset between methods and a concentration-dependent discrepancy. The regression equation would in this case show both an intercept significantly different from zero and a slope significantly different from 1 [26] [25].

Identifying these combined effects is particularly important for method validation, as each type of bias may have different sources and require different corrective approaches [7]. For instance, constant bias might stem from calibration issues, while proportional bias could indicate problems with analytical specificity or nonlinearity in the measurement response [28].

Table 1: Characteristics of Bias Types in Method Comparison

| Bias Type | Mathematical Representation | Visual Pattern | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Bias | y = x + b (b ≠ 0) | Parallel shift from identity line | Calibration errors, matrix effects |

| Proportional Bias | y = ax + b (a ≠ 1) | Divergence from identity line | Improper slope, instrument sensitivity |

| Combined Bias | y = ax + b (a ≠ 1, b ≠ 0) | Both shift and divergence | Multiple error sources |

Experimental Design for Bias Detection

Sample Selection and Preparation

Proper sample selection is critical for comprehensive bias assessment. A minimum of 40 patient specimens is recommended, carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method [7]. These specimens should represent the spectrum of diseases and conditions expected in routine application of the method. The quality of specimens is more important than quantity alone; 20 well-selected specimens covering the analytical range may provide better information than 100 randomly selected specimens [7].

Sample stability must be carefully controlled throughout the experiment. Specimens should generally be analyzed within two hours of each other by the test and comparative methods, unless specific analytes require shorter timeframes [7]. For unstable analytes, appropriate preservation techniques such as serum separation, refrigeration, or additive preservation should be implemented using standardized protocols to prevent handling-related discrepancies from being misinterpreted as analytical bias.

Measurement Protocol

The comparison experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 different days to account for daily variations in analytical performance [7]. Extending the study to 20 days with fewer specimens per day often provides more robust bias estimates by incorporating long-term reproducibility components [25]. This approach helps distinguish consistent systematic errors from random variations that occur under intermediate precision conditions.

When possible, duplicate measurements should be performed rather than single measurements [7]. Ideally, duplicates should represent different sample aliquots analyzed in different runs or at least in different order—not back-to-back replicates of the same cup. This duplicate analysis provides a check for measurement validity and helps identify discrepancies arising from sample mix-ups or transcription errors that could otherwise be misinterpreted as bias.

Reference Method Selection

The choice of comparison method significantly impacts bias interpretation. A reference method with documented accuracy through definitive methods or traceable reference materials is ideal, as any discrepancies can be attributed to the test method [7]. When using a routine method for comparison (termed a "comparative method"), differences must be carefully interpreted, as it may be unclear which method is responsible for observed discrepancies [7].

For materials used in bias estimation, reference values can be established through certified reference materials (CRMs), reference measurement procedures, or consensus values from external quality assessment schemes [28] [25]. However, research indicates that consensus values may not always approximate true values well, particularly for certain analytes like lipids and apolipoproteins, making reference method values preferable when available [28].

Statistical Analysis Methods

Regression Analysis

Regression analysis provides the primary statistical approach for identifying and quantifying both constant and proportional bias [7]. The fundamental regression equation for method comparison is:

y = ax + b

Where 'y' represents test method results, 'x' represents comparative method results, 'a' is the slope (indicating proportional bias), and 'b' is the intercept (indicating constant bias) [25]. The standard deviation of points about the regression line (s~y/x~) quantifies random error around the systematic error relationship.

For medical decision-making, systematic error at critical decision concentrations (X~c~) should be calculated as:

Y~c~ = a + bX~c~ SE = Y~c~ - X~c~

This calculation provides the clinically relevant bias at important medical decision levels [7]. When the correlation coefficient (r) is below 0.99, additional data collection or alternative regression approaches may be necessary, as simple linear regression may provide unreliable estimates of slope and intercept [7].

Difference Analysis (Bland-Altman)

The Bland-Altman method provides an alternative approach for assessing agreement between methods by plotting differences between measurements against their averages [29]. This method is particularly valuable for visualizing the magnitude and pattern of bias across the measurement range and for identifying individual outliers or concentration-dependent effects [28].

While Bland-Altman analysis effectively detects the presence of bias, it does not inherently distinguish between constant and proportional components without additional modifications [27] [29]. For this reason, many methodologies recommend combining Bland-Altman visualization with regression analysis to fully characterize the nature of systematic error [28].

Hypothesis Testing for Bias

Statistical hypothesis testing provides a framework for determining whether observed biases are statistically significant. Two common approaches include:

- Equality test: The null hypothesis states that bias equals zero against the alternative that it does not. A small p-value indicates statistically significant bias [30].

- Equivalence test: The null hypothesis states that bias falls outside a predefined interval of practical equivalence. A small p-value supports that bias is within acceptable limits [30].

These tests are complementary to point estimates of bias and should be interpreted in conjunction with confidence intervals and medical relevance considerations [30].

Table 2: Statistical Methods for Bias Detection and Characterization

| Method | Primary Function | Bias Detection Capability | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Models relationship between methods | Constant (intercept) and proportional (slope) | Regression equation, s~y/x~ |

| Bland-Altman Analysis | Visualizes agreement and differences | Overall bias pattern and range | Mean difference, limits of agreement |

| Least Products Regression | Handles error in both variables | Constant and proportional bias with error in both methods | Unbiased slope and intercept estimates |

| Hypothesis Testing | Determines statistical significance | Whether bias is statistically different from zero | p-values, confidence intervals |

Visualization Approaches

Regression Plots

Regression Analysis Workflow

Regression plots provide the most direct visualization for identifying constant and proportional bias. The graph displays test method results on the Y-axis versus comparative method results on the X-axis [7]. The line of identity (y = x) represents perfect agreement, while the regression line (y = ax + b) shows the actual relationship.

Visual interpretation focuses on the relationship between these two lines. A constant bias appears as a parallel vertical shift between the lines, while proportional bias manifests as differing slopes causing the lines to converge or diverge across the concentration range [26]. The dispersion of points around the regression line indicates random error, which should be considered when interpreting the practical significance of systematic error [26].

Difference Plots

Difference Plot Creation Process

Difference plots (Bland-Altman plots) display the difference between methods against the average of the two methods [28] [29]. This visualization excels at showing the magnitude and pattern of disagreement across the measurement range.

A horizontal distribution of points around zero indicates no systematic bias. A horizontal distribution offset from zero suggests constant bias. A sloping pattern or fan-shaped distribution indicates proportional bias, where differences increase or decrease with concentration [26]. The mean difference represents the average bias, while the limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 SD) show the expected range for most differences between methods [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Method Comparison Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provide reference quantity values for bias estimation | Commutability, traceability, uncertainty documentation |

| Commutable Control Materials | Mimic fresh patient sample properties | Matrix similarity, stability, homogeneity |

| Calibrators | Establish measurement traceability | Value assignment by reference method, stability |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor measurement performance | Well-characterized values, appropriate concentrations |

| Patient Sample Pool | Assess real-world performance | Diverse pathologies, concentration ranges, stability |

Data Interpretation and Clinical Implications

Assessing Statistical vs. Practical Significance

A statistically significant bias does not necessarily imply medically relevant consequences [30]. For large sample sizes, even trivial biases may achieve statistical significance, while clinically important biases in small studies may lack statistical significance [30]. Therefore, bias evaluation must consider both statistical testing and clinical context.

Researchers should compare estimated biases at medically important decision concentrations to established analytical performance specifications (APSs) [25]. These specifications define the quality required for analytical performance to deliver clinically useful results without causing harm to patients [25]. The systematic error at critical decision levels should be small enough not to affect clinical interpretation or patient management decisions.

Corrective Strategies Based on Bias Type

The type of bias identified dictates the appropriate corrective approach:

- Constant bias: Often correctable through calibration adjustment or blank correction. This may involve re-calibrating instruments or applying a fixed correction factor to all results [31].

- Proportional bias: Typically requires slope correction or method-specific calibration. This may involve using different calibrators or mathematical correction based on the established proportional relationship.

- Combined bias: Needs a comprehensive approach addressing both constant and proportional components, potentially involving method optimization or replacement if corrections are complex [26].

After implementing corrections, verification studies should confirm that biases have been effectively reduced to clinically acceptable levels across the measurement range.

Impact on Reference Intervals and Clinical Decision Limits

When changing measurement methods, significant biases may necessitate reference interval verification or establishment [26]. If a new method shows consistent positive constant bias compared to the previous method, reference intervals may need corresponding adjustment to maintain consistent clinical interpretation [26].

For proportional bias, the impact on patient classification depends on where medical decision limits fall relative to the convergence point of method comparisons. If decision limits are below the convergence point for negative proportional bias, reference intervals might not need adjustment, as the bias would only affect high values [26]. Understanding these relationships is essential for maintaining consistent clinical interpretation across method changes.

Conducting Robust Method Comparison Studies: From Design to Statistical Analysis

In method comparison studies, accurate and reliable results depend on controlling key pre-analytical and biological variables. The integrity of research on diagnostic platforms, biomarker assays, or pharmacokinetic parameters hinges on a rigorous experimental design that minimizes systematic error. This guide objectively compares methodological approaches by focusing on three foundational pillars: sample selection, timing, and accounting for physiological range. Failure to adequately control these factors introduces systematic errors (biases) that compromise the validity of a method's reported performance against its alternatives. This analysis provides a structured comparison of design protocols, supported by experimental data and clear visual workflows, to guide researchers in drug development and related fields toward more robust and generalizable method comparison experiments.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Understanding the following concepts is essential for designing method comparison experiments that accurately estimate and minimize systematic error.

- Systematic Error: A consistent, reproducible error due to the measurement method itself, as opposed to random error. In method comparison studies, it represents the bias between a new method and a reference standard.

- Sample Selection: The process and criteria by which biological specimens are chosen for a study. Biased selection can lead to a sample population that does not adequately represent the target physiological range, skewing method performance estimates [32].

- Physiological Range: The spectrum of values for a given analyte that can be observed in a healthy or diseased population. A method must be validated across this entire range to be clinically useful, as performance can vary at different concentrations [32].

- Method Comparison Experiment: A study designed to evaluate the agreement between two or more measurement methods, typically comparing a new method to an established reference.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

The following section compares standard and optimized protocols for the three critical design considerations, summarizing key differentiators and their impact on systematic error.

Table 1: Comparison of Standard vs. Optimized Methodological Approaches

| Design Consideration | Standard Practice | Optimized Practice | Impact on Systematic Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Selection | Convenience sampling; limited demographic/health coverage [32]. | Stratified sampling to cover the full physiological range, including pathological states [32]. | Reduces spectrum bias and improves the generalizability of the bias (difference) estimate between methods. |

| Timing | Single timepoint collection; unstandardized processing delays. | Multiple timepoints to account for diurnal/biological rhythms; standardized processing protocols. | Minimizes bias introduced by biological variability and sample degradation, providing a more stable performance estimate. |

| Physiological Range | Validation primarily within "normal" range [32]. | Deliberate inclusion of values spanning the entire expected clinical range (low, normal, high) [32]. | Ensures the method's performance is characterized across all relevant conditions, revealing context-specific biases. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol for a Comprehensive Method Comparison Study

This detailed protocol is designed to systematically control for sample, timing, and range-related biases.

- Define Scope and Reference: Clearly identify the new method and the reference method against which it is being compared. The reference standard should be a widely accepted "gold standard" if available.

- Ethical Approval and Informed Consent: Obtain all necessary ethical approvals and informed consent from participants before sample collection.

- Stratified Sample Recruitment: Recruit participants to ensure coverage across key demographic strata (e.g., age, sex) and health statuses (healthy, target disease, co-morbidities) to populate the full physiological range [32].

- Standardized Sample Collection:

- Timing: For analytes with known diurnal variation (e.g., cortisol), collect samples at a standardized time of day. If relevant, collect multiple samples over time from the same subject.

- Processing: Implement a standard operating procedure (SOP) for sample handling (e.g., centrifugation speed and time, aliquot volume, storage temperature) to minimize pre-analytical variation.

- Blinded Measurement: Analyze each sample using both the new and reference methods in a blinded fashion, where the operator is unaware of the result from the other method.

- Data Collection and Storage: Record all results in a structured database, including sample ID, demographic data, collection timestamp, and results from both methods.

Protocol for a Longitudinal Variability Assessment

This protocol specifically investigates the impact of timing on method performance.

- Participant Selection: Recruit a cohort of subjects representative of the target population.

- Baseline Sampling: Collect an initial sample from each participant following the standardized collection SOP.

- Follow-up Sampling: Collect subsequent samples from the same participants at predetermined intervals (e.g., 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months).

- Parallel Analysis: Analyze all samples using both the new and reference methods within the same analytical run, where possible, to minimize inter-assay variation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the within-subject and between-subject variability for both methods and assess the stability of the method difference (bias) over time.

The following tables summarize hypothetical experimental data that would be generated from the protocols described above, illustrating how different design choices impact the outcomes of a method comparison.

Table 2: Impact of Sample Selection on Reported Method Bias This table compares the average bias observed when a method is tested on a limited versus a comprehensive sample population.

| Sample Population | Sample Size (n) | Average Bias (Units) | 95% Limits of Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Adults Only | 40 | +0.5 | -2.1 to +3.1 |

| Full Physiological Range | 120 | +1.2 | -4.8 to +7.2 |

Table 3: Effect of Timing/Processing Delays on Analyte Stability This table shows how measured concentrations of a stable and a labile analyte change with processing delays, affecting method agreement.

| Processing Delay | Measured Concentration (Stable Analyte) | Measured Concentration (Labile Analyte) |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate (Baseline) | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| After 2 hours (RT) | 99.8 | 87.5 |

| After 4 hours (RT) | 99.5 | 75.2 |

| After 24 hours (4°C) | 98.9 | 65.8 |

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for a robust method comparison experiment, incorporating the critical design considerations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Method Comparison Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Provides a ground-truth value with known uncertainty, used to calibrate equipment and validate the accuracy of both the new and reference methods, directly impacting systematic error estimation. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | (e.g., high, normal, low concentration pools). Monitored across analytical runs to ensure method precision and stability over time, helping to distinguish systematic shift from random error. |

| Biobanked Samples | Well-characterized residual clinical samples stored under controlled conditions. Used for initial validation and to test method performance across a wide physiological range without the need for immediate, fresh recruitment. |

| Stabilizing Reagents | (e.g., protease inhibitors, RNA stabilizers). Added to samples immediately upon collection to preserve analyte integrity, mitigating bias introduced by pre-analytical delays and ensuring the measured value reflects the in-vivo state. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Reduces manual pipetting error during sample preparation and reagent addition, a potential source of systematic bias, especially in high-throughput settings. |

Implementing Bland-Altman Analysis for Assessing Agreement and Bias

Bland-Altman analysis, first introduced in 1983 and further detailed in 1986, has become the standard methodological approach for assessing agreement between two measurement techniques in clinical and laboratory research [29] [33]. This analytical technique was developed specifically to address the limitations of correlation analysis in method comparison studies. While correlation measures the strength of a relationship between two variables, it fails to quantify the actual agreement between measurement methods [33]. The Bland-Altman method quantifies agreement by analyzing the differences between paired measurements, providing researchers with a straightforward means to evaluate both systematic bias (fixed or proportional) and random error between methods [34] [35].

The core output of this analysis is the limits of agreement (LoA), which define an interval within which 95% of the differences between the two measurement methods are expected to fall [33] [36]. This approach has gained widespread acceptance across numerous scientific disciplines, with the original 1986 Lancet paper ranking among the most highly cited scientific publications across all fields [29]. For researchers investigating systematic error estimation in method comparison experiments, Bland-Altman analysis provides a robust framework for determining whether two methods can be used interchangeably or whether systematic biases preclude their equivalent application in research or clinical practice.

Fundamental Principles and Analytical Approach

Core Components of Bland-Altman Analysis

The Bland-Altman method operates on a fundamentally different principle from correlation analysis, focusing specifically on the differences between methods rather than their covariation. The analysis generates several key parameters that collectively describe the agreement between two measurement techniques:

Mean Difference (Bias): The average of the differences between paired measurements (Method A - Method B) [35]. This represents the systematic bias between methods, with values significantly different from zero indicating consistent overestimation or underestimation by one method relative to the other.

Limits of Agreement: Defined as the mean difference ± 1.96 times the standard deviation of the differences [33] [36]. These limits create an interval expected to contain 95% of the differences between the two measurement methods if the differences follow a normal distribution.

Clinical Agreement Threshold: A predetermined value representing the maximum acceptable difference between methods based on clinical requirements, biological considerations, or analytical goals [33] [36]. This threshold is not determined statistically but must be established a priori based on the specific research context.

The Bland-Altman Plot

The visual representation of the analysis is the Bland-Altman plot, which displays the relationship between differences and magnitude of measurement [34]. This scatter plot is constructed with the following axes:

- X-axis: The average of the two measurements for each subject [(Method A + Method B)/2]

- Y-axis: The difference between the two measurements for each subject (Method A - Method B)

The plot typically includes three horizontal lines: one at the mean difference (bias), and two representing the upper and lower limits of agreement [37] [36]. This visualization enables researchers to detect patterns that might indicate proportional bias, heteroscedasticity (where variability changes with measurement magnitude), or outliers that warrant further investigation.

Table 1: Key Components of a Bland-Altman Plot

| Component | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference (Bias) | Average of all differences between paired measurements | Systematic over/underestimation by one method |

| Limits of Agreement | Mean difference ± 1.96 × SD of differences | Range containing 95% of differences between methods |

| Data Points | Individual difference values plotted against averages | Visual assessment of agreement patterns and outliers |

| Clinical Threshold | Predetermined acceptable difference | Reference for evaluating clinical significance |

Methodological Variations and Advanced Applications