A Practical Guide to Developing Accurate UV-Vis Calibration Curves for Compound Quantification in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on developing and validating UV-Vis calibration curves for precise compound quantification.

A Practical Guide to Developing Accurate UV-Vis Calibration Curves for Compound Quantification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on developing and validating UV-Vis calibration curves for precise compound quantification. It covers foundational principles grounded in the Beer-Lambert Law, detailed methodological protocols for creating linear and non-linear curves, advanced troubleshooting for common instrument and sample issues, and a comparative analysis of UV-Vis against other quantification techniques like HPLC and NMR. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application, troubleshooting, and validation strategies, this resource aims to enhance data reliability and methodological robustness in pharmaceutical and clinical research settings.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy and Calibration Fundamentals: Principles for Accurate Quantification

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is a fundamental principle in spectroscopy that establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of light by a substance and its concentration [1]. This law serves as the cornerstone for quantitative analysis in ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, enabling researchers to determine the concentration of analytes in solution by measuring how much light they absorb [2] [3]. In the context of drug development and analytical research, this principle provides the theoretical foundation for developing robust calibration curves essential for accurate compound quantification [4].

The law is mathematically expressed as: A = εbc Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (a dimensionless quantity)

- ε (epsilon) is the molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹)

- b is the path length of light through the solution (cm)

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (mol·L⁻¹) [1] [3]

This relationship indicates that absorbance is directly proportional to both the concentration of the substance and the path length of the light through the sample, with the molar absorptivity representing how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a specific wavelength [5].

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Concepts of Light Absorption

When monochromatic light passes through a solution containing an absorbing species, photons interact with molecules, promoting electrons to higher energy states. This interaction results in a measurable attenuation of the incident light beam [2]. The extent of light absorption depends on several factors, including the molecular structure of the analyte, the wavelength of light used, and the number of molecules in the light path [1].

The relationship between incident and transmitted light intensity is described through two key parameters:

- Transmittance (T): The ratio of transmitted light intensity (I) to incident light intensity (I₀), often expressed as a percentage [1]

- Absorbance (A): The logarithmic measure of light attenuation by the sample, calculated as A = log₁₀(I₀/I) [1] [3]

The following table illustrates the inverse logarithmic relationship between absorbance and transmittance:

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 0.3 | 50% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

Table 1: Relationship between absorbance and transmittance values [1]

The Components of the Beer-Lambert Equation

Molar Absorptivity (ε) The molar absorptivity coefficient is a substance-specific constant that measures how effectively a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [3]. This intrinsic molecular property depends on the electronic structure of the molecule and the solvent system used. Higher values indicate stronger absorption, with typical values ranging from 0 to over 100,000 L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹ for highly absorbing chromophores [5].

Path Length (b) The path length represents the distance light travels through the sample solution, typically determined by the width of the cuvette used for measurement [1]. Standard cuvettes have a path length of 1 cm, though specialized cells with shorter path lengths (e.g., 1 mm) are available for highly concentrated samples to maintain absorbance within the ideal measurement range [2].

Concentration (c) The concentration of the absorbing species in the solution, usually expressed in moles per liter (mol·L⁻¹ or M). The Beer-Lambert Law assumes a linear relationship between concentration and absorbance, which holds true for dilute solutions but may deviate at higher concentrations due to molecular interactions [6].

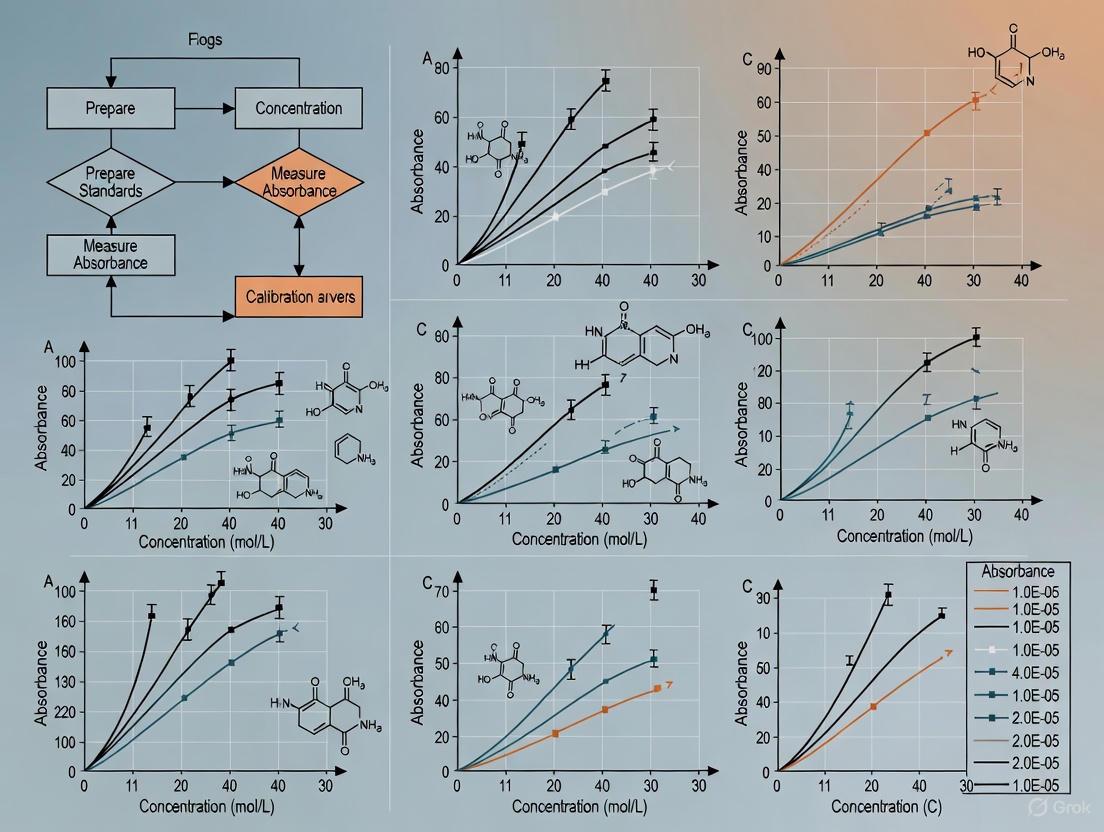

Figure 1: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Workflow

Practical Application: Developing UV-Vis Calibration Curves

Protocol for Calibration Curve Development

Materials and Reagents

- Standard solutions of the analyte at known concentrations

- Appropriate solvent for preparing standard and sample solutions

- UV-transparent cuvettes (quartz for UV, glass or plastic for visible range)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with wavelength selection capability

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes for accurate solution preparation

Step-by-Step Procedure

Instrument Preparation

Standard Solution Preparation

- Prepare a stock solution of the analyte with accurately known concentration.

- Create a series of standard solutions covering the expected concentration range of your samples through serial dilution [4]. Ensure concentrations fall within the linear range of the Beer-Lambert relationship (typically absorbance values between 0.1 and 1.0 AU) [2].

Blank Measurement

- Fill a cuvette with the pure solvent used to prepare your standard and sample solutions.

- Place the cuvette in the sample holder and measure the blank to establish the I₀ reference value [2].

Standard Measurements

Calibration Curve Generation

- Plot absorbance (y-axis) versus concentration (x-axis) for all standard solutions.

- Perform linear regression analysis to obtain the equation of the best-fit line: y = mx + b, where m represents the slope (εb) and b is the y-intercept [4].

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (r²) to validate linearity; values ≥0.995 indicate acceptable linearity for quantitative analysis [4] [7].

Sample Analysis

- Measure the absorbance of unknown samples under identical conditions.

- Calculate sample concentrations using the regression equation from the calibration curve [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Optically transparent cells for holding samples; quartz is essential for UV measurements due to its transparency at short wavelengths [2]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | High-purity compounds of known concentration for preparing calibration standards and verifying method accuracy [4]. |

| Spectral Solvents | High-purity solvents with minimal UV absorption in the wavelength range of interest (e.g., water, acetonitrile, methanol) [2]. |

| Buffer Systems | Solutions for maintaining constant pH, particularly important for analytes whose absorption properties are pH-dependent [7]. |

| Chromogenic Reagents | Chemicals that react with target analytes to produce colored compounds with specific absorption maxima (e.g., promethazine for potassium bromate detection) [7] [8]. |

Table 2: Essential materials for UV-Vis spectrophotometric analysis

Method Validation Parameters

When developing UV-Vis methods for quantitative analysis, several validation parameters must be established to ensure reliability, accuracy, and precision [4] [7].

Linearity The calibration curve should demonstrate a directly proportional relationship between absorbance and concentration. The correlation coefficient (r²) provides a measure of linearity, with values ≥0.995 generally considered acceptable for quantitative analysis [4] [7].

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

- LOD: The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, typically with a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 [4] [7]

- LOQ: The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy, typically with a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [4] [7]

Accuracy and Precision

- Accuracy: Measured as percentage recovery, indicates how close the measured value is to the true value [4]. Recovery rates of 90-110% are generally acceptable [4] [7].

- Precision: The degree of agreement among repeated measurements, expressed as relative standard deviation (%RSD) [4]. Values <2% RSD typically indicate good precision [4].

The following validation data from recent research illustrates typical performance parameters:

| Validation Parameter | Result | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.370-2.570 μg/mL | N/A |

| Regression Equation | Y = 0.020x + 0.030 | N/A |

| Correlation Coefficient (r²) | 0.9962 | ≥0.995 |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.005 μg/g | N/A |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 0.016 μg/g | N/A |

| Recovery Rate | 82.97-108.54% | 90-110% |

| Precision (%RSD) | 0.13% | <2% |

Table 3: Example method validation data for UV-Vis spectrophotometric determination [7]

Figure 2: UV-Vis Method Development and Validation Workflow

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

The Beer-Lambert Law finds diverse applications in pharmaceutical research, quality control, and drug development processes:

API Quantification UV-Vis spectroscopy enables the quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in raw materials, formulations, and dissolution media. For example, ascorbic acid content in beverage preparations was determined using a validated UV-Vis method with a standard vitamin C calibration curve, demonstrating 103.5% recovery with excellent precision (%RSD = 0.13%) [4].

Impurity Detection The technique can detect and quantify potentially harmful substances in pharmaceutical products. Recent research developed a green UV-Vis method for determining potassium bromate in bread using promethazine as a chromogenic reagent, achieving an LOD of 0.005 μg/g and LOQ of 0.016 μg/g [7] [8].

Dissolution Testing UV-Vis spectroscopy facilitates real-time monitoring of drug release from formulations during dissolution testing, providing critical data for biopharmaceutics classification and formulation optimization.

Biomolecule Analysis The method is widely employed for quantifying proteins, nucleic acids, and other biomolecules in drug discovery research, with specific applications in bacterial culturing, drug identification, and nucleic acid purity checks [2].

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Despite its widespread utility, the Beer-Lambert Law has limitations that researchers must consider for accurate quantitative analysis:

Deviations from Linearity The linear relationship between absorbance and concentration may deviate under certain conditions:

- High concentrations (>0.01 M): Molecular interactions and electrostatic effects can alter absorptivity [6]

- Chemical associations: Equilibrium processes such as dimerization or polymerization change effective molar absorptivity [6]

- Instrumental factors: Stray light, polychromatic radiation, and detector non-linearity can cause deviations [2] [6]

Scattering and Reflection Effects In real-world samples, light loss due to scattering (particularly in turbid solutions or biological tissues) and reflection at cuvette interfaces can lead to apparent deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law [9] [6]. For highly scattering media, modified versions of the law have been developed that incorporate differential pathlength factors to account for these effects [9].

Sample-Related Considerations

- Matrix effects: Complex sample matrices can cause apparent deviations through light scattering or interfering absorptions [8]

- pH dependence: Absorption spectra of ionizable compounds can shift significantly with pH changes [6]

- Temperature sensitivity: Molar absorptivity may vary with temperature, particularly for charge-transfer complexes [6]

Optimal Measurement Conditions To minimize errors and maintain linearity:

- Keep absorbance values between 0.1 and 1.0 AU [2]

- Use matched cuvettes with consistent path lengths [2]

- Employ high-purity solvents with minimal background absorption [2]

- Maintain constant temperature during measurements [6]

- Use monochromatic light with bandwidth narrower than the absorption band [6]

In the field of analytical chemistry, spectrophotometers are indispensable instruments for quantifying compound concentrations through UV-Vis spectroscopy. These instruments operate on the fundamental principle of measuring the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by a sample, following the Beer-Lambert Law which states that absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species [2]. The core components of a spectrophotometer include a stable light source, a wavelength selection system, a sample holder, and a detector [2]. The reliability of quantitative analysis, particularly in critical applications such as pharmaceutical drug development, hinges on selecting the appropriate spectrophotometer configuration and understanding its operational parameters. This application note provides a detailed comparison of single beam, double beam, and diode array spectrophotometers, with specific protocols for generating accurate UV-Vis calibration curves in compound quantification research.

Spectrophotometer Configurations: Principles and Comparison

Optical Designs and Operating Principles

Single Beam Spectrophotometers utilize the most straightforward optical design where a single light beam passes through the monochromator, through the sample, and to the detector [10]. This configuration requires separate measurements of the solvent blank (reference) and the sample, as the instrument cannot measure both simultaneously. The simplicity of this design makes it cost-effective but potentially susceptible to measurement drift from source instability.

Double Beam Spectrophotometers employ a mechanical chopper or beam splitter to divide the light from the source into two separate paths: a reference beam and a sample beam [11]. This design allows simultaneous measurement of the sample and reference, with the detector alternating between the two beams [11] [10]. The key advantage lies in the instrument's ability to automatically compensate for solvent absorption and source intensity fluctuations in real-time, providing enhanced stability and reliability [11].

Diode Array Spectrophotometers represent a significant advancement in detection technology. Instead of using a monochromator before the sample, these instruments pass polychromatic light through the sample and then disperse it onto an array of photodiodes [12]. This enables simultaneous detection of all wavelengths across the spectrum, dramatically reducing acquisition time and allowing for full spectral capture of chromatographic peaks [12]. The reversed optical path distinguishes this configuration from scanning monochromator-based systems.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Spectrophotometer Configurations

| Parameter | Single Beam | Double Beam | Diode Array |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Design | Single light path | Split beam: reference & sample | Polychromatic light with post-dispersion |

| Measurement Sequence | Sequential blank & sample | Simultaneous reference & sample | Simultaneous all wavelengths |

| Data Acquisition Speed | Moderate | Fast | Very fast (full spectrum in seconds) |

| Stability & Compensation | Susceptible to source drift | Real-time compensation for drift [11] | Stable, but different compensation approach |

| Wavelength Selection | Pre-sample monochromator | Pre-sample monochromator | Post-sample polychromator |

| Spectral Resolution | Dependent on monochromator slit width | Dependent on monochromator slit width | Determined by diode density and optics |

| Primary Applications | Routine quantitative analysis at fixed wavelengths | Kinetic studies, wavelength scanning [11] | Spectral scanning, peak purity assessment [12] |

| Approximate Cost | Low | Medium to High | High |

Performance Characteristics and Selection Criteria

The choice between spectrophotometer configurations depends heavily on the specific requirements of the quantification method. Double beam instruments offer superior stability because their readings are not easily affected by external factors such as energy and voltage fluctuations, lamp drift, and stray light [11]. This makes them particularly suitable for applications requiring high precision and for experiments extending over prolonged periods. Additionally, double beam spectrophotometers require minimal warmup time, which increases throughput and prolongs the lamp's lifespan [11].

Diode array detectors provide significant advantages for method development and peak purity assessment because they capture the entire UV spectrum simultaneously [12]. This capability is invaluable for identifying compounds based on their spectral characteristics and for detecting potential impurities in analytical samples. The ability to retrospectively analyze data at different wavelengths without reinjection saves considerable time in method development.

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Different Spectrophotometer Configurations

| Configuration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Single Beam | Simple operation, lower cost, compact size | Requires separate blank measurement, susceptible to source drift, slower throughput |

| Double Beam | High stability, real-time blank correction, fast scanning [11] | Higher cost, more complex operation [11] |

| Diode Array | Rapid full spectrum acquisition, peak purity assessment [12] | Higher cost, potentially lower resolution depending on design |

Experimental Protocols for UV-Vis Calibration Curve Generation

General Preparation and Instrument Setup

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Specification |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytical Standard | Primary reference material of the target compound with known purity |

| Appropriate Solvent | HPLC-grade solvent transparent in the spectral region of interest |

| Volumetric Flasks | Class A, various sizes for standard solution preparation |

| Cuvettes | Quartz for UV range (190-380 nm); glass or plastic for visible range [2] |

| Buffer Salts | For maintaining stable pH when required by analyte properties |

Protocol 1: Instrument Startup and Qualification

- Power on the spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for the manufacturer-recommended time (typically 15-30 minutes; double beam instruments may require less warmup time [11]).

- Select the appropriate measurement mode (absorbance) and set the analytical wavelength based on the compound's λmax.

- For diode array systems, set the spectral acquisition range (typically 200-800 nm for full UV-Vis coverage).

- Perform instrument qualification using certified holmium oxide or didymium filters to verify wavelength accuracy.

- Using a matched pair of cuvettes, fill both with the blank solvent and perform a baseline correction to account for any solvent absorption or cuvette differences.

Standard Solution Preparation and Measurement

Protocol 2: Stock and Working Standard Preparation

- Accurately weigh an appropriate amount of the analytical standard using an analytical balance.

- Transfer quantitatively to a volumetric flask and dilute to volume with the selected solvent to create the stock standard solution.

- Calculate the stock solution concentration using the formula: C_stock = (mass × purity) / volume.

- Create a series of working standards by performing serial dilutions of the stock solution to cover the expected concentration range. Typically, 5-8 concentration levels are recommended for a calibration curve.

- Ensure all solutions are properly mixed and free of air bubbles before measurement.

Protocol 3: Absorbance Measurement and Data Collection

- Set the instrument to zero absorbance using the blank solvent contained in a cuvette identical to those used for samples.

- For single beam instruments: Measure each standard solution in sequence, rinsing the cuvette at least three times with the next standard to be measured.

- For double beam instruments: Place the blank in the reference position and measure each standard in the sample position [11].

- For diode array instruments: Acquire full spectra for each standard, noting the absorbance at the analytical wavelength.

- Record all absorbance values, ensuring they fall within the instrument's linear range (typically 0.2-1.0 AU for optimal performance).

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Protocol 4: Calibration Curve Generation and Validation

- Plot absorbance (y-axis) versus concentration (x-axis) for all standard solutions.

- Perform linear regression analysis to obtain the equation: y = mx + b, where m is the slope and b is the y-intercept.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (R²) to assess linearity; for quantitative work, R² should typically be ≥0.995.

- Determine the linear dynamic range by identifying where the response deviates from linearity (typically at higher concentrations).

- Calculate the limit of detection (LOD = 3.3σ/S) and limit of quantification (LOQ = 10σ/S), where σ is the standard deviation of the blank and S is the slope of the calibration curve.

Protocol 5: Sample Analysis and Quantification

- Prepare unknown samples in the same solvent system as the standards.

- Measure the absorbance of unknown samples using the same instrumental conditions as the calibration standards.

- Calculate the unknown concentration using the regression equation: Cunknown = (Aunknown - b) / m.

- For samples falling outside the calibration range, appropriately dilute and remeasure, applying the dilution factor in final concentration calculations.

- Include quality control samples with known concentrations to verify method accuracy throughout the analysis.

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Specialized Quantification Methods

In drug development, each spectrophotometer configuration offers unique advantages for specific applications. Double beam systems excel in kinetic studies where reaction progress is monitored over time at a specific wavelength, as their inherent stability minimizes baseline drift during extended measurements [11]. Diode array systems are particularly valuable for method development because they enable retrospective analysis at different wavelengths without reinjection and facilitate peak purity assessment by comparing spectra across a chromatographic peak [12].

For DNA and protein quantification, double beam spectrophotometers provide the rapid, reproducible measurements essential for high-throughput applications [11]. The simultaneous reference measurement capability allows for accurate ratio-based calculations (e.g., A260/A280 for nucleic acid purity) without concern for source fluctuation between measurements.

Troubleshooting and Method Validation

Common Issues and Solutions:

- Poor Linear Range: Ensure absorbance readings remain between 0.2-1.0 AU; dilute samples as needed.

- Baseline Drift: More common in single beam systems; allow sufficient lamp warmup time and maintain constant temperature.

- Spectral Noise: More pronounced at narrower bandwidths; use appropriate slit widths balancing resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

Method Validation Parameters: For regulatory applications such as pharmaceutical quality control, method validation should include assessment of linearity, accuracy, precision, LOD, LOQ, and robustness. The higher precision achievable with UV detection (<0.2% RSD) is particularly important in pharmaceutical testing where typical potency specifications for drug substances range from 98.0% to 102.0% [12].

The selection of an appropriate spectrophotometer configuration is critical for developing robust UV-Vis calibration methods in compound quantification research. Single beam instruments offer cost-effectiveness for routine fixed-wavelength analyses, while double beam configurations provide enhanced stability for dynamic experiments and scanning applications. Diode array systems deliver unparalleled speed and spectral information for method development and peak purity assessment. By following the detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can generate reliable calibration curves that meet the rigorous demands of pharmaceutical development and other quantitative analytical applications. The implementation of proper quality control measures and understanding of each instrument's capabilities and limitations will ensure accurate, reproducible results in compound quantification studies.

The Critical Role of Calibration Curves in Quantitative Analysis

In the realm of quantitative analytical science, the calibration curve, also known as a standard curve, serves as a fundamental cornerstone for determining the concentration of unknown substances. This methodological approach establishes a predictable relationship between the instrumental response and the analyte concentration, allowing researchers to convert measurable signals into meaningful quantitative data [13]. In the specific context of UV-Vis spectrophotometry, this technique leverages the principle that the absorbance of light by a chemical species is directly proportional to its concentration, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [13] [14].

The critical importance of calibration curves extends across numerous scientific disciplines, including pharmaceutical quality control, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research [13] [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, proper calibration ensures the accuracy, precision, and reliability of quantitative measurements, which form the basis for critical decisions regarding compound characterization, dosage formulation, and regulatory compliance [15]. Without robust calibration methodologies, the validity of experimental results remains questionable, potentially compromising research outcomes and product safety.

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry operates on the principle that molecules absorb light in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. When a sample is exposed to UV-Vis light, chromophores within the molecules undergo electronic transitions, absorbing specific wavelengths of light [13]. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components: a light source (typically a xenon lamp, or combination of tungsten/halogen and deuterium lamps), a wavelength selector (monochromator or filters), a sample holder (cuvette), and a detector [14].

The instrument measures the transmittance (the percentage of light passing through the sample) and calculates the absorbance according to the mathematical relationship A = -log(T), where T is transmittance [14]. According to the Beer-Lambert law, absorbance (A) is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species: A = εMc, where ε is the molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient, M is the path length of the cuvette, and c is the concentration [13]. This linear relationship between absorbance and concentration forms the theoretical basis for quantitative analysis using calibration curves.

Mathematical Modeling of Calibration Curves

The fundamental mathematical model for a calibration curve in UV-Vis spectrophotometry is a linear relationship expressed as:

S = kC + b

Where S is the measured signal (absorbance), C is the analyte concentration, k is the sensitivity (slope), and b is the y-intercept [16]. This model assumes a first-order dependence of the signal on concentration. The sensitivity (k) represents the change in signal per unit change in concentration, while the intercept (b) ideally should be close to zero, though instrumental background or matrix effects may cause slight deviations [16].

The validity of this linear model must be experimentally verified across the concentration range of interest, as deviations from linearity may occur at higher concentrations due to instrumental limitations or chemical factors such as molecular associations [16]. For quantitative analysis, the coefficient of determination (R²) is used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the experimental data to the linear regression model, with values closer to 1.0 indicating a better fit [14].

Figure 1: Theoretical foundation of calibration curves showing the relationship between fundamental principles and practical application.

Performance Parameters for Method Validation

Critical Validation Parameters

For any quantitative analytical method, rigorous validation is essential to ensure the reliability and accuracy of results. Instrument validation for UV-Vis spectrophotometers encompasses multiple performance parameters that collectively determine the suitability of the method for quantitative analysis [17]. These parameters, as prescribed in standards such as JIS K0115 "General rules for molecular absorptiometric analysis," provide a comprehensive framework for assessing instrument performance [17].

Wavelength accuracy refers to the agreement between the instrument's measured wavelength values and the true wavelength values, typically verified using emission lines of deuterium or low-pressure mercury lamps or absorption peaks of certified reference materials [17]. Photometric accuracy assesses the correctness of absorbance or transmittance measurements, while photometric repeatability evaluates the precision of replicate measurements [17]. Stray light, defined as light outside the specified wavelength that reaches the detector, can significantly impact measurement accuracy, particularly at high absorbance values [17].

Comprehensive Performance Specifications

Table 1: Key performance parameters for UV-Vis spectrophotometer validation

| Performance Parameter | Definition | Impact on Quantitative Analysis | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Accuracy | Agreement between measured and true wavelength values | Affects spectral identification and selectivity | Typically ±0.1 nm for high-performance instruments [17] |

| Photometric Accuracy | Correctness of absorbance/transmittance measurements | Directly impacts concentration accuracy | Dependent on application requirements [17] |

| Stray Light | Light outside specified wavelength reaching detector | Causes non-linearity at high absorbance | Critical for high-absorbance samples [17] |

| Noise Level | Random fluctuations in measured signal | Affects detection and quantitation limits | Lower noise enables better detection of small peaks [17] |

| Baseline Flatness | Deviation from flat baseline across wavelength range | Impacts measurement consistency | Should be minimal across analytical range [17] |

The noise level, defined as the maximum deviation of absorbance measured over time, serves as an important indicator of instrument condition, particularly the state of the light source [17]. As lamps deteriorate over time, noise typically increases, adversely affecting measurement precision [17]. Baseline stability and flatness further contribute to measurement quality by ensuring consistent performance across the analytical wavelength range [17].

Experimental Protocols

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for calibration curve preparation

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Solution | High-purity analyte in appropriate solvent | Provides known concentrations for calibration [14] |

| Solvent | Deionized water or HPLC-grade organic solvents | Matrix for preparing standards and samples [14] |

| Volumetric Flasks | Class A, various volumes (e.g., 10 mL, 25 mL, 50 mL) | Precise preparation of standard solutions [14] |

| Pipettes and Tips | Calibrated, appropriate volume range | Accurate transfer of solutions [14] |

| Cuvettes | Quartz (UV) or glass (Vis), matched pathlength | Sample holder for spectrophotometer [14] |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Validated performance parameters | Instrument for absorbance measurements [17] [14] |

Step-by-Step Calibration Curve Protocol

Preparation of Standard Solutions

Begin by preparing a concentrated stock solution of the standard compound using an analytical balance and volumetric flask to ensure precise concentration [14]. The solvent should be identical to that used for unknown samples to maintain matrix matching. Prepare a series of standard solutions spanning the expected concentration range of unknown samples through serial dilution [14]. A minimum of five standard concentrations is recommended to establish a reliable calibration curve, with concentrations appropriately spaced to define the concentration-response relationship [14].

For the serial dilution, pipette a specific volume of the stock solution into the first volumetric flask and dilute to volume with solvent. Mix thoroughly, then transfer an aliquot from this solution to the next flask and repeat the process. This systematic approach ensures accurate preparation of decreasing standard concentrations while maintaining consistent matrix composition [14].

Absorbance Measurement and Data Collection

Transfer each standard solution to an appropriate cuvette, ensuring compatibility with the spectrophotometer's wavelength range (quartz for UV measurements, glass or plastic for visible range) [14]. Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the predetermined analytical wavelength, using solvent as the blank to zero the instrument [14]. Obtain multiple readings (typically 3-5 replicates) for each standard to assess measurement precision and enable statistical evaluation of the data [14].

Repeat the measurement process for unknown samples prepared in the same matrix as the standards. Maintain consistent measurement conditions (temperature, timing, instrument parameters) throughout the analysis to minimize variability. Record all absorbance values systematically, noting any deviations from expected values or observations during measurement.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for developing and applying calibration curves in quantitative analysis.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Construction of the Calibration Curve

Following data collection, plot the average absorbance values for each standard on the y-axis against the corresponding known concentrations on the x-axis [14]. The resulting graph should display a linear relationship across the working concentration range, with deviations from linearity potentially occurring at higher concentrations (limit of linearity) due to detector saturation or deviations from the Beer-Lambert law [14].

Apply linear regression analysis to the data points using appropriate statistical software, generating the equation y = mx + b, where y represents absorbance, m is the slope (sensitivity), x is the concentration, and b is the y-intercept [14]. The slope (m) of the calibration curve reflects the sensitivity of the method, with steeper slopes indicating greater sensitivity to concentration changes. The y-intercept (b) should theoretically pass through the origin (zero absorbance at zero concentration), though minor deviations may occur due to matrix effects or instrumental background [14].

Assessment of Curve Quality and Validation

Evaluate the quality of the calibration curve using the coefficient of determination (R²), which quantifies the goodness of fit of the experimental data to the linear regression model [14]. While R² values close to 1.0 (typically >0.995 for quantitative work) indicate a good fit, this parameter alone does not guarantee analytical suitability [15]. Additional statistical measures, including residual analysis and examination of homoscedasticity, provide deeper insight into the appropriateness of the linear model [15].

The phenomenon of heteroscedasticity, where the variance of measurements changes with concentration, is common in analytical data and should be addressed through appropriate weighting factors in the regression model if significant [15]. For proper method validation, include quality control (QC) samples with known concentrations across the calibration range to verify the accuracy and precision of the established curve [15]. The calibration curve should be reconstructed with each analytical batch to account for potential instrument drift over time [15].

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Matrix Effects and Mitigation Strategies

In quantitative analysis, matrix effects represent a significant challenge, occurring when components in the sample matrix enhance or suppress the analytical signal, leading to inaccurate concentration determinations [15]. These effects are particularly problematic in complex biological matrices where co-eluting compounds may interfere with the target analyte [15].

To mitigate matrix effects, several strategies can be employed. The use of matrix-matched calibrators, where standards are prepared in a matrix similar to the unknown samples, helps minimize differences between calibration and sample matrices [15]. For endogenous analytes, creating a "blank" matrix through stripping techniques (e.g., charcoal treatment, dialysis) or using synthetic matrices can provide appropriate calibration media, though commutability between the calibrator matrix and native patient samples must be verified [15]. The incorporation of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) for each target analyte represents the most effective approach for compensating for matrix effects, as these compounds experience nearly identical ionization suppression/enhancement as the native analytes while being distinguishable mass spectrometrically [15].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common issues may arise during calibration curve development that require troubleshooting. Non-linearity at higher concentrations may indicate detector saturation, stray light effects, or chemical associations such as dimerization [17] [14]. This can be addressed by diluting samples, using a shorter pathlength cuvette, or restricting the analytical range. Poor reproducibility between replicates often results from instrumental issues (e.g., lamp degradation, excessive noise) or solution handling problems (incomplete mixing, pipetting errors) [17].

Abnormal intercept values significantly different from zero may suggest contamination in reagents, incorrect blank preparation, or non-specific interference in the matrix [16]. Inconsistent QC sample recovery might indicate calibration curve instability, matrix effects differences between standards and samples, or analyte degradation [15]. Regular instrument validation, including checks of wavelength accuracy, photometric accuracy, and stray light, helps identify and correct instrumental contributions to these issues [17].

Application in Drug Development and Research

In pharmaceutical research and development, calibration curves play an indispensable role in multiple stages of the drug development pipeline. During drug discovery, they facilitate the quantification of lead compounds in biological matrices for preliminary pharmacokinetic assessments. In preclinical development, validated calibration methods enable accurate determination of drug concentrations in plasma, tissues, and excreta for comprehensive ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) studies [15].

For bioavailability and bioequivalence studies, rigorously validated calibration curves with appropriate matrix matching are essential for generating reliable pharmacokinetic data [15]. In formulation development, UV-Vis spectrophotometry with proper calibration supports the assessment of drug stability, solubility, and release profiles from dosage forms. The implementation of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines requires documented calibration procedures and regular performance verification to ensure data integrity and regulatory compliance [17] [15].

The critical role of calibration curves extends to quality control laboratories, where they are employed for assay determination, impurity quantification, and content uniformity testing of pharmaceutical products [13]. In these regulated environments, calibration methods must be thoroughly validated according to regulatory guidelines, with defined acceptance criteria for accuracy, precision, linearity, and range [15]. The selection of appropriate calibration standards, matrix considerations, and statistical evaluation of curve fit all contribute to the overall quality and reliability of analytical results supporting drug development and manufacturing.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique used to determine the concentration of compounds in solution [18]. The successful quantification of analytes, particularly in critical fields like drug development, relies on a thorough understanding of three core parameters: molar absorptivity, path length, and dynamic range. These parameters are intrinsically linked through the Beer-Lambert law, which forms the theoretical basis for absorption spectroscopy [19] [20]. This application note details the definition, relationship, and practical application of these parameters within the context of developing robust UV-Vis calibration curves for compound quantification research, providing scientists with the protocols needed to generate reliable and reproducible data.

Theoretical Foundations

The Beer-Lambert Law

The relationship between light absorption and the properties of a solution is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law. The equation is expressed as:

A = εbc

Where:

- A is the measured Absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹)

- b is the Path Length (cm)

- c is the Concentration (mol·L⁻¹) [19] [18] [20]

This law states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels through the sample [19].

In-Depth Parameter Analysis

Molar Absorptivity (ε)

Molar absorptivity, also known as the extinction coefficient, is a physical constant that defines how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a specific wavelength [20] [21]. It is a measure of the amount of light absorbed per unit concentration [20]. Its value is influenced by the chemical identity of the analyte and the solvent, as well as environmental factors such as temperature and pH [21].

- Significance: A compound with a high molar absorptivity is very effective at absorbing light, allowing for its detection at lower concentrations [20] [21]. Values can vary significantly between compounds and are typically on the order of 10⁵ L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹ for simple molecules [19].

- Dependence: Because its value can be affected by the chemical environment (e.g., solvent, pH, temperature) and instrument-specific factors, it is often determined empirically through calibration curves rather than relied upon from literature [19] [21].

Path Length (b)

The path length is the distance that light travels through the sample solution, typically measured in centimeters (cm) [19]. In standard spectroscopy, this is determined by the width of the cuvette, with 1 cm being the most common [18].

- Significance: Absorbance increases in direct proportion to the path length [19] [22]. This property can be leveraged analytically; for very dilute samples, using a long pathlength cell (e.g., 50 mm or 100 mm) can increase the absorbance signal, making quantification more reliable [23] [22]. Conversely, for very concentrated samples, a shorter path length can bring an otherwise off-scale absorbance into the measurable range.

- Variable Pathlength Technique: This method involves measuring absorbance at multiple path lengths for a single concentration. A plot of Absorbance vs. Path Length yields a straight line whose slope (m) is equal to the product of the molar absorptivity and the concentration (m = εc). This technique averages out minor inconsistencies and can negate the need for background subtraction [23].

Dynamic Range

The dynamic range in UV-Vis spectroscopy refers to the concentration interval over which a change in concentration produces a proportional (linear) change in the measured absorbance, in accordance with the Beer-Lambert Law [14].

- Limits: The lower limit of the dynamic range is determined by the limit of detection (LOD), the smallest concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise. The upper limit is the limit of linearity (LOL), the concentration at which the instrument begins to saturate and the absorbance-concentration relationship deviates from linearity [14].

- Practical Impact: A calibration curve is considered valid only within the dynamic range of the instrument for that specific analyte under the specified conditions [14]. Attempting to quantify a sample outside this range will lead to significant errors.

Table 1: Key Parameters in UV-Vis Quantification

| Parameter | Symbol & Units | Definition | Role in Beer's Law | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Absorptivity | ε (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹) | Measure of how strongly a species absorbs light at a given wavelength [20] [21]. | Proportionality constant linking absorption to concentration [19]. | Compound-specific; can be affected by solvent, pH, and temperature [21]. |

| Path Length | b (cm) | Distance light travels through the sample solution [19]. | Directly proportional to absorbance [19]. | Can be varied using specialized cells to adjust absorbance for low/high concentrations [23] [22]. |

| Dynamic Range | - | Concentration range over which absorbance response is linear [14]. | Defines the valid range for the equation A = εbc. | Calibration curves are only valid within this range; limits are LOD and LOL [14]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a UV-Vis Calibration Curve

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for creating a calibration curve to quantify an unknown sample, a cornerstone technique in analytical chemistry and biochemistry [14] [13].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coat, and safety glasses [14].

- Standard Solution: A concentrated stock solution of the pure analyte with a known, accurately determined concentration [14].

- Solvent: High-purity solvent (e.g., deionized water, methanol) matching the solvent of the unknown sample [14].

- Pipettes and Tips: Calibrated precision pipettes and corresponding tips for accurate liquid handling [14].

- Volumetric Flasks/Microtubes: For preparing standard solutions with precise volumes [14].

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: Instrument with a light source, wavelength selector, and detector [18] [14].

- Cuvettes: Sample holders compatible with the spectrophotometer and the wavelength range (e.g., quartz for UV) [14].

- Computer: For instrument control, data collection, and analysis [14].

Procedure:

- Prepare Stock Solution: Accurately weigh the solute and transfer it to a volumetric flask. Dilute to the mark with solvent to create a concentrated stock solution [14].

- Generate Standard Solutions: Perform a serial dilution to create a minimum of five standard solutions spanning the expected concentration range of the unknown. For example, prepare standards at 100%, 75%, 50%, 25%, and 10% of the stock concentration. Use volumetric flasks and change pipette tips between each transfer to ensure accuracy [14].

- Prepare Samples: Transfer the standard solutions and the unknown sample(s) into clean, labeled cuvettes. Ensure the unknown samples are prepared using the same buffer and pH as the standards [14].

- Measure Absorbance:

- Zero (blank) the spectrophotometer using a cuvette filled only with solvent [18].

- Place each standard solution in the spectrophotometer and measure the absorbance at the predetermined analytical wavelength (typically at an absorbance maximum).

- Obtain between three and five replicate readings for each standard to assess precision [14].

- Repeat the measurement process for the unknown sample(s).

- Plot Data and Analyze: Plot the average absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration (x-axis) for each standard. Use statistical software to fit the data to a linear regression (y = mx + b), and determine the coefficient of determination (R²) to assess the goodness of fit. An R² value of 0.9 or better is typically acceptable [18] [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Protocol 2: Leveraging Variable Path Length for Slope Spectroscopy

This method is particularly useful for obtaining accurate concentration data without the need for a full calibration curve or when sample consistency is variable [23].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- All materials from Protocol 1, except:

- Variable Pathlength Cell: A sample holder whose path length can be accurately and reproducibly varied [23].

Procedure:

- Prepare Sample: Place the sample of unknown concentration into the variable pathlength cell [23].

- Measure at Multiple Path Lengths: Without changing the sample concentration, measure the absorbance at several different, accurately known path lengths [23].

- Plot and Calculate Slope: Plot the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the path length (x-axis). This should yield a straight line. Perform a linear regression to determine the slope (m) of the line [23].

- Determine Concentration: The slope (m) from the plot is equal to the product of the molar absorptivity and the concentration (m = εc). If the molar absorptivity (ε) is known for the compound, the concentration (c) can be calculated directly as c = m / ε [23].

Data Analysis and Application

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships and Ranges for Key Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Units | Proportionality | Typical Values / Range | Analytical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Absorptivity (ε) | L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹ | Directly proportional to A [19]. | Up to ~100,000 for simple molecules [19]. | High ε enables lower detection limits [20] [21]. |

| Path Length (b) | cm | Directly proportional to A [19]. | Standard: 1 cm; Long-path: 2, 5, 10 cm [22]. | 10x longer path → 10x higher A for same concentration [22]. |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Unitless | Measures linearity of calibration curve [14]. | >0.9 for an acceptable calibration [18]. | Quantifies reliability of the calibration model [14]. |

Visualizing Parameter Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the core relationship between the parameters of the Beer-Lambert Law and the experimental techniques used to manipulate them for accurate quantification.

A rigorous understanding of molar absorptivity, path length, and dynamic range is non-negotiable for developing precise and accurate UV-Vis calibration methods in quantitative research. Molar absorptivity provides the fundamental link between a compound's chemical structure and its light-absorbing properties. Path length offers a practical tool to optimize analytical signals for a wide range of concentrations. Finally, the dynamic range defines the operational limits within which the Beer-Lambert Law holds true. By applying the detailed protocols and principles outlined in this application note, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their spectroscopic data is robust, reliable, and suitable for critical decision-making processes.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique used for the quantitative analysis of compounds in solution. The reliability of this quantification is critically dependent on the quality of the calibration curve, which itself is heavily influenced by the proper selection and handling of samples and solvents. This document outlines key considerations and detailed protocols for ensuring optimal absorbance measurements within the context of developing robust UV-Vis calibration curves for compound quantification research, particularly relevant to drug development.

The foundational principle of UV-Vis quantification, the Beer-Lambert Law (A = εbc), establishes a linear relationship between absorbance (A) and the concentration (c) of an analyte in solution [18]. However, this relationship can be compromised by inappropriate sample and solvent choices, leading to inaccurate concentration predictions. This note provides a structured approach to mitigate these risks.

Fundamental Principles and the Impact of Sample & Solvent

The accuracy of a calibration curve begins with understanding how the measurement environment—the solvent and the sample itself—affects light absorption.

The Beer-Lambert Law and the Solvent Blank

The Beer-Lambert Law is the cornerstone of absorbance quantification [18]. A critical, often overlooked, step in its application is the use of a blank reference to zero the instrument. The blank must contain the same solvent and any other chemical components present in the sample, except for the analyte of interest. This corrects for any light absorption or scattering caused by the solvent or cuvette, ensuring that the measured absorbance is due solely to the target compound [18].

Sample Limitations

UV-Vis spectroscopy performs best with true solutions. As noted in the search results, if a sample is more of a suspension of solid particles in a liquid, the sample will scatter light more than absorb it, leading to skewed and unreliable data [18]. While accessories for solid samples exist, the technique is most efficient and accurate for liquids and solutions.

Critical Considerations for Solvents and Samples

The following table summarizes the key factors researchers must evaluate when selecting and preparing solvents and samples for UV-Vis calibration.

Table 1: Critical Solvent and Sample Considerations for UV-Vis Absorbance Measurements

| Factor | Consideration | Impact on Absorbance Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Transparency | The solvent must not absorb significantly in the spectral region where the analyte absorbs. | A solvent with a high background absorbance will reduce the available light path, decreasing the signal-to-noise ratio and the dynamic range for detection [14]. |

| Solvent-Analyte Chemical Compatibility | The solvent must fully dissolve the analyte without reacting with it. | Incomplete dissolution can cause light scattering. Chemical reactions can alter the analyte's chemical structure and its absorptivity (ε), invalidating the calibration [14]. |

| Matrix Effects | For complex samples (e.g., biological fluids), other components in the sample can scatter light or absorb at the same wavelength as the analyte. | This can cause signal suppression or enhancement, leading to a non-linear calibration curve and inaccurate quantification of the unknown [15]. |

| Sample Homogeneity | The sample must be a clear, homogeneous solution. | Suspended particles or turbidity cause significant light scattering, which is measured as absorbance, leading to a positive bias in the concentration calculation [18]. |

| Pathlength | The distance light travels through the sample (typically defined by the cuvette). | According to the Beer-Lambert Law, absorbance is directly proportional to pathlength. Using a consistent, appropriate pathlength is crucial for accurate calibration [18]. |

Advanced Consideration: Mitigating Matrix Effects

In bioanalysis, where samples are complex matrices like plasma, a "blank matrix" is used to prepare calibration standards. This is a material (e.g., drug-free plasma) that is as representative as possible of the sample matrix but devoid of the analyte. Using matrix-matched calibrators helps to compensate for matrix effects, ensuring the signal-to-concentration relationship is conserved between standards and unknown samples [15]. For endogenous analytes where a true blank is unavailable, the method of standard additions can be applied [24].

Experimental Protocol: Developing a UV-Vis Calibration Curve

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for preparing standards and generating a reliable calibration curve for compound quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Protects the researcher from exposure to hazardous chemicals and samples [14]. |

| High-Purity Analytical Standard | A solution with a known, high concentration of the pure analyte. Serves as the source for preparing all calibration standards [14]. |

| UV-Transparent Solvent | A solvent (e.g., HPLC-grade water, methanol, acetonitrile) that does not absorb in the UV-Vis range of interest, ensuring analyte signal is not obscured [14]. |

| Precision Pipettes and Calibrated Tips | Allows for accurate and precise measurement and transfer of liquid volumes, which is critical for preparing standards of exact concentrations [14]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | Used for precise preparation of standard solutions to ensure accuracy in concentration [14]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | The instrument used to measure the absorbance of light by the standard and unknown samples [18] [14]. |

| Spectrophotometer Cuvettes | Sample holders that must be clean and matched. Quartz is required for UV range measurements due to its transparency at short wavelengths [14]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the overall workflow for creating and validating a UV-Vis calibration curve.

Step 1: Prepare a Concentrated Stock Solution

- Accurately weigh the solute and transfer it to a volumetric flask.

- Dilute to the mark with the appropriate solvent to create a stock solution of known, high concentration [14].

Step 2: Prepare Calibration Standards via Serial Dilution

- A minimum of five standards are recommended for a good calibration curve [14].

- Label a series of volumetric flasks or microtubes with the target concentrations. The standards should span the expected concentration range of the unknown samples, from just above the estimated unknown concentration down to an order of magnitude lower [18].

- Perform a serial dilution:

- Pipette a specific volume of the stock solution into the first flask.

- Dilute to the mark with solvent and mix thoroughly.

- Pipette from this first dilution into the next flask.

- Repeat the process of dilution and transfer to create the series of standards [14].

Step 3: Measure Absorbance of Standards and Unknowns

- Zero the Instrument: Place a cuvette filled only with the solvent (the blank) into the spectrophotometer and set the absorbance to zero. This critical step must be performed before reading any standards or unknowns [18].

- Measure Standards: Transfer each standard to a clean cuvette and obtain an absorbance reading at the predetermined wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax). Obtain between three and five replicate readings for each standard to assess precision [14].

- Measure Unknowns: Transfer the unknown samples to a cuvette and measure their absorbance under the exact same conditions. Ensure the unknown samples are prepared in the same buffer and at the same pH as the standards [14].

Step 4: Plot the Data and Generate the Calibration Curve

- Plot the average absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration (x-axis) for each standard.

- Fit the data to a linear regression model (y = mx + b) using statistical software. The output provides the slope (m) and y-intercept (b) of the calibration line [14].

- Examine the plot. A well-behaved curve will appear linear over a specific range, with a non-linear section (limit of linearity, LOL) indicating detector saturation at high concentrations [14].

Step 5: Examine and Validate the Calibration Curve

- Assess Linearity: The coefficient of determination (R²) quantifies the goodness of fit. However, an R² close to 1.0 is not sufficient alone to prove linearity. Use residual plots and other statistical tests (e.g., lack-of-fit test) to validate the model [25].

- Check for Heteroscedasticity: Over a wide concentration range, the variance of the response can change (heteroscedasticity). If the data shows increasing scatter with concentration, a weighted least squares regression should be used to improve accuracy, especially at the lower end of the calibration range [25] [15].

- Use Quality Controls (QC): Quality Control samples prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations within the calibration range should be analyzed to verify the accuracy and precision of the method during validation and routine use [25].

Data Analysis and Advanced Fitting Methodologies

For simple systems, a linear regression is sufficient. However, for complex molecules like conjugated organic dyes, advanced fitting functions may be required to accurately interpret UV-Vis spectra. Recent research demonstrates the efficacy of a modified Pekarian function (PF) for fitting spectra with high accuracy, especially for bands that are vibronically resolved or completely unresolved [26]. This approach, which optimizes five parameters defining the band shape, can provide a more accurate deconvolution of overlapping bands compared to traditional Gaussian or Lorentzian functions, allowing for more precise extraction of quantitative information [26].

Step-by-Step Protocol: Developing Robust UV-Vis Calibration Curves

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a foundational analytical technique in research and drug development, used to determine the concentration of compounds in solution. The principle relies on the measurement of how much ultraviolet or visible light is absorbed by a sample, described by the Beer-Lambert law [2]. This relationship between absorbance and concentration is quantifiable through a calibration curve, making accurate and precise curve construction critical for reliable results. This protocol details the development of a pharmaceutical-compliant UV-Vis calibration curve, providing a standardized methodology for researchers and scientists engaged in compound quantification.

Principles and Theory

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, molecules absorb light of specific wavelengths, promoting electrons to higher energy states. The amount of light absorbed at a given wavelength is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a solution, provided the path length is constant [2]. This relationship is expressed by the Beer-Lambert law:

A = εlc

Where:

- A is the measured Absorbance (no units)

- ε is the molar absorptivity (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹)

- l is the path length of the cuvette (cm)

- c is the concentration of the analyte (mol·L⁻¹)

A calibration curve is a plot of absorbance (y-axis) against known concentrations of standard solutions (x-axis). The data is typically fit with a linear regression, yielding an equation (y = mx + b) that is used to calculate the concentration of unknown samples based on their absorbance [14] [27]. The coefficient of determination (R²) quantifies the goodness of fit, with a value close to 1.0 indicating a highly linear relationship [14].

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details the essential materials required for the preparation of standard solutions and execution of the calibration protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for UV-Vis Calibration Curve Preparation

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Lab coat, gloves, and safety glasses to ensure user safety [14] [28]. |

| Standard Solution | A concentrated stock solution of the analyte with a known, high purity [14]. |

| Solvent | High-purity solvent (e.g., deionized water, methanol) matching the sample matrix and transparent in the UV-Vis range [14]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | Class A glassware for precise preparation and dilution of standard solutions [29] [30]. |

| Pipettes and Tips | Calibrated precision pipettes and corresponding tips for accurate liquid transfer [14]. |

| Cuvettes | Sample holders; quartz for UV analysis, glass or plastic for visible light only [14] [2]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument comprising a light source, wavelength selector, and detector to measure absorbance [2]. |

| Analytical Balance | For precise weighing of solid solutes to prepare stock solutions [14]. |

| Vortex Mixer | To ensure thorough mixing and homogeneity of solutions (Optional) [14]. |

Instrumentation

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer is the core instrument. Key components include [2]:

- Light Source: Often a combination of a deuterium lamp (UV) and a tungsten or halogen lamp (visible).

- Wavelength Selector: A monochromator with a diffraction grating (typically >1200 grooves/mm) to isolate specific wavelengths.

- Detector: A photomultiplier tube (PMT) or photodiode to convert light intensity into an electrical signal.

For regulated pharmaceutical environments, instruments like the PerkinElmer LAMBDA 365+ with enhanced security (ES) software ensure 21 CFR Part 11 compliance and support workflows from R&D to QC [31].

Experimental Protocol

Preparation of Standard Solutions

- Prepare Stock Solution: Accurately weigh the analyte and transfer it to a volumetric flask. Dilute to the mark with solvent to create a concentrated stock solution [14].

- Perform Serial Dilution: Label a series of volumetric flasks for the standard concentrations.

- Pipette a calculated volume of the stock solution into the first flask.

- Dilute to the mark with solvent and mix thoroughly. This is the first standard.

- Repeat this process, sequentially pipetting from the previous dilution into the next flask and diluting to create a series of at least five standards covering the expected concentration range of the unknown samples [14].

Spectrophotometric Measurement

- Instrument Setup: Turn on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow it to initialize. Set the desired wavelength based on the analyte's absorption maximum [28].

- Establish Baseline: Fill a cuvette with the pure solvent (blank) and place it in the sample holder. Collect a baseline or zero the absorbance [2] [28].

- Measure Standards: Transfer each standard solution into a clean cuvette and place it in the spectrophotometer. Record the absorbance value. Obtain between three and five replicate readings for each standard to assess precision [14].

- Measure Unknowns: Transfer the unknown samples to cuvettes and measure their absorbance following the same procedure used for the standards [14].

Data Analysis and Curve Fitting

- Plot the Data: Create a scatter plot with concentration on the x-axis and the average absorbance for each standard on the y-axis [14].

- Perform Linear Regression: Fit the data to a linear regression model (y = mx + b) using statistical software. The output provides the slope (m, sensitivity) and y-intercept (b) [14] [27].

- Calculate R²: Obtain the coefficient of determination (R²) to evaluate the linearity of the curve. An R² value >0.995 is typically desirable for quantitative work [14].

- Determine Unknown Concentrations: Use the regression equation (y = mx + b) to calculate the concentration (x) of unknown samples based on their measured absorbance (y) [27].

The following workflow diagrams the complete experimental process from preparation to analysis.

Workflow for UV-Vis Calibration

Data Interpretation and Quality Control

Evaluating the Calibration Curve

A well-constructed calibration curve should have a significant linear portion. At higher concentrations, the relationship may become non-linear (limit of linearity), indicating the instrument is nearing saturation [14]. The linear dynamic range should be used for quantification.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Data Analysis and Validation

| Parameter | Description & Target Value |

|---|---|

| Linear Range | The concentration interval over which the absorbance-concentration relationship remains linear. |

| Slope (m) | Represents the sensitivity of the method. A steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity. |

| Y-Intercept (b) | Should be close to zero. A significant offset may indicate matrix interference. |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Quantifies linearity. A value of >0.995 is typically expected for quantitative analysis [14]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration that can be detected (but not necessarily quantified). |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. |

Quality Assurance and Compliance

For pharmaceutical analysis, compliance with global pharmacopoeia standards (USP, Eur. Ph., JP) is mandatory [31]. This includes:

- Instrument Qualification: Regular operational qualification (OQ) according to standards such as USP <857> to ensure instrument performance [31].

- Volumetric Equipment Calibration: Regular gravimetric calibration of flasks and pipettes is essential for data integrity [29] [30].

- Data Integrity: Use of compliant software with audit trails and electronic records to meet 21 CFR Part 11 regulations [31].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Cuvette Selection: Use quartz cuvettes for UV light measurements, as glass and plastic absorb UV light [2].

- Absorbance Range: Keep absorbance readings below 1.0 to remain within the instrument's dynamic range. Dilute samples that are too concentrated [2].

- Path Length Consistency: Ensure all measurements use cuvettes of the same path length (typically 1 cm) [2].

- Sample Clarity: Ensure samples are clear and free of particulates that could scatter light.

- Temperature Control: Be aware that temperature fluctuations can impact some measurements and reaction kinetics [27].

In quantitative analytical research, particularly in studies involving UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy for compound quantification, the preparation of a concentrated stock solution is a fundamental prerequisite for generating reliable calibration curves [32] [33]. A stock solution of accurately known concentration serves as the primary reference from which all subsequent standards and dilutions are derived. The integrity of the entire calibration process, and by extension the accuracy of compound quantification in unknown samples, hinges on the precision and care taken during this initial step [34]. This protocol details a standardized methodology for preparing a concentrated aqueous stock solution, framed within the context of developing a UV-Vis calibration model.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table catalogs the essential materials and reagents required for the accurate preparation of a concentrated stock solution.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for Stock Solution Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Provides precise measurement of solute mass, which is critical for calculating exact molarity [34]. |

| Purified Water | Acts as the solvent; using purified water ensures that impurities do not contaminate the solution or interfere with subsequent UV-Vis analysis [34]. |

| High-Purity Solute | The compound to be quantified (e.g., chalcone, polystyrene nanoplastics). High purity ensures an accurate and specific spectroscopic signal [32] [33]. |

| Volumetric Flask | Designed to contain a precise volume of liquid at a specified temperature, ensuring the final solution volume is accurate [34]. |

| Weigh Boats | Used to contain the solute during weighing on the analytical balance, preventing spillage and contamination [34]. |

| Magnetic Stir Plate & Stir Bar | Facilitates the rapid and even dissolution of the solute in the solvent, leading to a homogeneous stock solution [34]. |

| pH Meter | Monitors and allows for adjustment of the solution's pH, which can be critical for solute stability and UV-Vis absorbance characteristics [34]. |

Experimental Protocol

Calculation of Solute Mass

The first step involves calculating the exact mass of solute required to achieve the desired concentration and volume of the stock solution.

- Define Parameters: Determine the target concentration (e.g., 5 M) and final volume (e.g., 1 L) of your stock solution.

- Obtain Molecular Weight: Find the molecular weight (MW) of the solute, typically listed on the container, in g/mol.

- Apply Formula: Use the following formula to calculate the required mass [34]:

Mass (g) = Concentration (mol/L) × Volume (L) × Molecular Weight (g/mol)Example: To prepare 1 L of a 5 M solution of a compound with a MW of 50 g/mol: Mass (g) = 5 mol/L × 1 L × 50 g/mol = 250 g

Step-by-Step Preparation Procedure

Follow this detailed methodology to prepare the stock solution [34].

- Weigh the Solute: Using an analytical balance and a weigh boat, carefully measure the mass of solute calculated in the previous step.

- Transfer Solvent: Pour approximately three-quarters of the final volume of purified water into a clean beaker. For a 1 L solution, use about 750 mL of water.

- Dissolve the Solute: a. Place a magnetic stir bar into the beaker. b. Set the beaker on a magnetic stir plate and begin stirring. c. Gradually add the weighed solute to the stirring water.

- Adjust pH (if necessary): Once the solute is fully dissolved, measure the pH of the solution. Adjust to the desired pH using dilute sodium hydroxide (to increase pH) or dilute hydrochloric acid (to decrease pH). Add these reagents slowly to avoid overshooting the target.

- Finalize Volume (Q.S. to Volume): a. Using a funnel, quantitatively transfer the solution from the beaker into a volumetric flask of the target volume (e.g., 1 L). b. Carefully add purified water ("q.s." or quantum satis) until the bottom of the meniscus is level with the calibration mark on the neck of the flask. c. Cap the flask and invert it several times to ensure complete mixing and homogeneity.

Workflow and Data Integration for UV-Vis Calibration

The prepared stock solution is the foundation for a workflow that culminates in the creation of a UV-Vis calibration curve, a critical tool for quantifying compounds in unknown samples [32] [33]. This process involves serial dilution, spectroscopic measurement, and data analysis.

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Dilution and Data Generation for Calibration

The concentrated stock solution is used to prepare a series of standard solutions of known concentration through dilution, which are then analyzed via UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Table 2: Example Dilution Scheme and Data Recording for Calibration

| Standard Solution | Volume of Stock (mL) | Volume of Solvent (mL) | Final Concentration (µg/mL) | UV-Vis Absorbance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 |

| Std 1 | 1.00 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 0.150 |

| Std 2 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 2.00 | 0.305 |

| Std 3 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 0.590 |

| Std 4 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 0.885 |

| Std 5 | 8.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 1.180 |

Note: Example assumes a stock solution concentration of 10 µg/mL. The dilution formula used is: C₁V₁ = C₂V₂ [34].

Calibration Curve Construction Logic

The data from Table 2 is used to establish a mathematical relationship between concentration and absorbance, forming the calibration model.

The resulting calibration curve, defined by the equation ( y = mx + c ) (where ( y ) is absorbance, ( m ) is the slope, ( x ) is concentration, and ( c ) is the y-intercept), provides the model to calculate the concentration of an unknown sample based on its measured absorbance [33]. The linearity of this relationship, often indicated by an R² value close to 1 (e.g., 0.9994), validates the method's effectiveness over the specified concentration range [33].

Within the methodology for developing a UV-Vis calibration curve for the precise quantification of analytes in drug development, the preparation of standard solutions via serial dilution is a critical foundational step. The accuracy of the entire analytical procedure hinges on the precision with which these standard concentrations are prepared. This protocol details a reliable method for performing serial dilutions to create a standard curve, enabling researchers to quantify unknown compound concentrations with high confidence [35] [14].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following reagents and equipment are essential for the accurate preparation of standard solutions and subsequent spectrophotometric analysis [14].

Table: Essential Materials for Serial Dilution and UV-Vis Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Concentrated Stock Solution | A solution with a precisely known, high concentration of the analyte of interest. Serves as the source for all subsequent dilutions [35] [14]. |