A Systematic Guide to Optimizing ESI Ionization Voltage for Enhanced LC-MS Sensitivity and Reproducibility

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and analytical scientists on optimizing electrospray ionization (ESI) voltage in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

A Systematic Guide to Optimizing ESI Ionization Voltage for Enhanced LC-MS Sensitivity and Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and analytical scientists on optimizing electrospray ionization (ESI) voltage in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Covering foundational principles to advanced methodologies, it details the critical impact of ionization voltage on signal intensity, adduct formation, and overall method robustness. The content explores systematic optimization strategies, including univariate and multivariate Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches, alongside practical troubleshooting for common issues like electrical discharge and matrix effects. With a focus on application in drug development and biomedical research, this guide serves as an essential resource for developing sensitive, reliable, and quantitatively accurate LC-MS methods.

Understanding ESI Ionization Voltage: Principles and Impact on Signal Quality

The Role of Capillary Voltage in the Electrospray Process

In electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (MS), the capillary voltage (also referred to as the spray voltage or needle voltage) is the high direct current (DC) potential applied to the metal capillary or emitter to facilitate the ionization process. This voltage creates a strong electric field between the emitter and the mass spectrometer inlet, which is fundamental to the electrospray process. It is responsible for both charging the liquid emerging from the capillary to form a Taylor cone and generating the fine aerosol of charged droplets from which gas-phase ions ultimately desorb [1]. The optimal setting for this parameter is not universal; it varies significantly between instrumental setups and is profoundly influenced by experimental conditions, including solvent composition, flow rate, and the specific analytes under investigation [2] [3] [4]. This application note details the critical role of capillary voltage, providing quantitative data and structured experimental protocols to guide its optimization within the broader context of method development for ESI research.

Fundamental Principles and Effects

The primary function of the capillary voltage is to induce a charge on the liquid surface at the capillary tip. When the electrostatic forces overcome the surface tension of the liquid, the liquid deforms into a conical shape (Taylor cone) from which a fine jet emerges and disintegrates into a spray of highly charged droplets [1]. The voltage required to initiate and sustain a stable electrospray is dependent on several factors, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Factors Influencing Optimal Capillary Voltage

| Factor | Effect on Optimal Capillary Voltage | Underlying Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Composition | Higher aqueous content requires a higher voltage [4]. | Aqueous solvents have higher surface tension, requiring a stronger electric field to form the Taylor cone. |

| Flow Rate | Lower flow rates (e.g., nanoESI) generally require lower voltages [5]. | Smaller initial droplet size at low flow rates is more efficiently charged and desolvated. |

| Sample Conductivity | Higher ionic strength requires lower voltages [2]. | Increased conductivity allows for more efficient charge transport, reducing the voltage needed for spray formation. |

| ESI Source Geometry | Voltage application point (e.g., metal union vs. sample vial) changes the optimal value [2]. | The effective electric field strength is determined by the voltage drop across the emitter and the distance to the counter-electrode. |

| Interface Pressure | Sub-atmospheric pressure interfaces (e.g., SPIN-MS) can operate with different optimal ranges [6]. | Reduced pressure affects droplet evaporation and the electric field distribution. |

Beyond establishing the spray, the capillary voltage plays a significant role in the overall ionization process. Excessive voltage can lead to detrimental effects such as electrical discharge (particularly in negative ion mode), "rim emission" leading to an unstable signal, and promotion of unwanted electrochemical side reactions or gas-phase discharges that can cause oxidation of analytes and source components [2] [4]. Conversely, a voltage set too low may fail to initiate a stable electrospray or result in poor desolvation and inefficient ion formation. Furthermore, in capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS), the ESI needle voltage has been shown to modify the electroosmotic flow (EOF) within the separation capillary by up to ±30%, demonstrating that its influence extends beyond the spray tip and can affect upstream separation processes [7].

Quantitative Data and Optimization Studies

Impact on Signal Response

The effect of capillary voltage on signal intensity is analyte- and system-dependent. Systematic optimization has demonstrated that significant gains in sensitivity are achievable. For instance, in the determination of metabolites in human urine, a Face-Centered Central Composite Design (CCD) was used to optimize ESI source parameters. The capillary voltage was found to be a significant factor, and its optimization, in conjunction with other parameters, led to a marked increase in the MS signal for challenging compounds like 7-methylguanine [8]. A compelling real-world example comes from a Waters application note, where a scientist reported that for certain compounds, reducing the capillary voltage to 0.5 kV in positive ion mode provided a significantly better response compared to the more conventional 3–3.5 kV. These methods were successfully validated, highlighting that lower voltages can sometimes be optimal for specific analytes [9].

Table 2: Representative Capillary Voltage Ranges from Literature

| Application / Instrument Context | Typical / Optimized Voltage Range | Key Observation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| General ESI Operation | ~3 kV | Often set as a default value but may be sub-optimal for specific methods. | [1] |

| Sensitivity Increase for Specific Compounds | 0.5 kV (Positive Mode) | Significantly better response for some analytes compared to standard 3-3.5 kV. | [9] |

| DoE Optimization for Metabolites | 2 – 4 kV (Optimized via CCD) | A key factor for maximizing signal; optimal value depends on other source parameters. | [8] |

| NanoESI with Voltage Applied at Sample Vial | Lower than metal union application | Required optimal voltage is dependent on the point of application and solvent conductivity. | [2] |

Optimization via Design of Experiments (DoE)

A one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach to ESI optimization is inefficient and often fails to capture significant interaction effects between parameters. The use of statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a more robust and systematic framework [10] [8]. For example, a study on protein-ligand complexes used an Inscribed Central Composite Design (CCI) to optimize the ESI source, including capillary voltage, to maximize the relative abundance of the protein-ligand complex while minimizing dissociation. This approach was critical for obtaining an accurate equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), and it was noted that even structurally similar ligands (GMP and GDP) required different optimal ESI conditions [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for optimizing capillary voltage using a DoE approach:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization for LC-ESI-MS

This protocol is adapted from methods used to optimize the determination of metabolites in human urine [8].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Analyte Stock Solutions | To prepare standard solutions at relevant concentrations for infusion or LC-MS analysis. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol). To ensure minimal background interference and consistent mobile phase properties. |

| Acetic Acid or Formic Acid | A mobile phase additive to promote protonation in positive ion mode. |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | A volatile buffer for stabilizing pH without causing ion suppression. |

| Tuning Mix Solution | (e.g., ESI-L Low Concentration Tuning Mix). For initial instrumental calibration and performance verification. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initial Instrument Setup: Calibrate the mass spectrometer using a standard tuning mix. Establish a preliminary LC method or a direct infusion method delivering a solvent composition representative of the elution conditions for your analyte (e.g., 1% B in isocratic elution).

- Factor Selection and Range Definition: Select key ESI source parameters for optimization. Based on the literature, critical factors often include:

- Capillary Voltage (e.g., 2000 – 4000 V)

- Nebulizer Gas Pressure (e.g., 10 – 50 psi)

- Drying Gas Flow Rate (e.g., 4 – 12 L/min)

- Drying Gas Temperature (e.g., 200 – 340 °C)

- Screening Design:

- Use a two-level Fractional Factorial Design (FFD) to screen the selected factors.

- The response can be the peak area or height of a target analyte (e.g., one with poor ionization efficiency).

- Perform the experimental runs in random order to minimize bias.

- Statistically analyze the results (e.g., using ANOVA) to identify which factors have a significant effect on the response.

- Response Surface Modeling:

- For the significant factors identified in the screening step, apply a Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD) to model the response surface.

- The number of experimental runs will be determined by the design. Again, perform runs in random order.

- Data Analysis and Optimization:

- Using statistical software, fit the data to a quadratic model and generate response surface plots.

- Analyze the plots to understand the interaction effects between factors, particularly between capillary voltage and other source parameters.

- Use the model's prediction function to identify the factor settings that maximize the desired response (e.g., signal intensity).

- Validation:

- Experimentally validate the predicted optimal settings by analyzing the target analyte(s) under these conditions.

- Compare the signal intensity and stability with the pre-optimized conditions to confirm improvement.

Protocol 2: Optimization for Protein-Ligand Binding Studies

This protocol is derived from work on optimizing ESI conditions for native MS studies of protein-ligand complexes [10].

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Purified Protein | (e.g., Plasmodium vivax guanylate kinase). The target macromolecule for the binding study. |

| Ligand(s) | (e.g., GMP, GDP). The small molecule(s) that bind to the protein. |

| Volatile Buffer | (e.g., 10-200 mM Ammonium Acetate, pH 6.8). To maintain protein structure and non-covalent interactions while being compatible with ESI-MS. |

| Size Exclusion Spin Columns | (e.g., NAP-5 columns). For buffer exchange into the volatile ammonium acetate buffer. |

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Buffer exchange the purified protein into a volatile ammonium acetate buffer (e.g., 10 mM, pH 6.8) using size exclusion spin columns. Prepare working solutions of the protein and ligand at a fixed ratio (e.g., PvGK:GMP at 2:4.8 μM) in the volatile buffer. Incubate to reach binding equilibrium.

- Define Optimization Goal and Response: The goal is to preserve the solution-phase equilibrium in the gas phase. The response (Y) to be maximized is the relative abundance ratio of the protein-ligand complex to the free protein (PL/P), calculated from the sum of the intensities of all charge states.

- Experimental Design and Execution:

- Implement an Inscribed Central Composite Design (CCI). This design studies factors at five levels and is suitable when the experimental limits are close to the instrumental limits.

- Include the capillary voltage as one of the key factors, alongside others like nebulizer gas pressure, drying gas temperature and flow rate, and various lens voltages.

- Carry out the experiments by infusing the pre-incubated protein-ligand solution and acquiring mass spectra under the different parameter sets defined by the CCI.

- Data Analysis:

- Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to analyze the data and build a model linking the ESI parameters to the PL/P ratio.

- The optimal conditions are those that simultaneously maximize the PL/P ratio and minimize the dissociation of the complex during the ESI process.

- Method Application: Use the optimized capillary voltage and source conditions for subsequent titration or competition experiments to determine accurate equilibrium dissociation constants (KD).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for ESI Voltage Optimization

| Item | Category | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Volatile Buffers (Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate) | Buffer | Maintains solution pH and ionic strength without persistent residue that fouls the MS interface. Essential for native MS. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents & Additives (Water, ACN, MeOH, FA, AcOH) | Solvent | Minimizes chemical noise; additives promote analyte protonation/deprotonation. Solvent composition directly impacts optimal voltage. |

| Chemical Standards (e.g., tuning mix, target analytes) | Standard | Used for instrument calibration and as a test probe during method optimization to measure response. |

| Syringe Pump | Instrument | Provides stable, pulseless flow for direct infusion experiments, crucial for isolating the effect of voltage from LC pump fluctuations. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, R with 'rsm' package) | Software | Enables the design of experiments (DoE) and statistical analysis of results for efficient, robust optimization. |

Capillary voltage is a foundational parameter in the electrospray ionization process, with its optimal setting being highly conditional. Rather than being a "set-and-forget" value, it should be actively managed during method development. As demonstrated, the use of structured, multivariate approaches like Design of Experiments is far more effective than univariate testing for finding optimal conditions, especially when dealing with complex samples or when aiming to preserve non-covalent interactions. A deep understanding of the role of capillary voltage, combined with the systematic experimental protocols outlined herein, provides researchers and drug development professionals with a robust framework for enhancing the sensitivity, stability, and overall quality of their ESI-MS methods.

How Ionization Voltage Directly Influences Sensitivity and Detection Limits

In mass spectrometry, ionization voltage is a pivotal parameter that directly controls the efficiency of ion generation, profoundly influencing the sensitivity and detection limits of an analysis. This relationship is critical in techniques such as electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), where the applied voltage governs the initial formation of charged droplets and subsequent gas-phase ions [11] [4]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a meticulous understanding and optimization of this parameter is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental aspect of method development that can dictate the success or failure of an assay.

This application note delineates the direct mechanisms through which ionization voltage governs analytical sensitivity. It provides detailed, executable protocols for its systematic optimization, framed within the context of a broader thesis on maximizing performance in ESI-based research. By mastering the control of ionization voltage, scientists can significantly enhance signal intensity, lower detection limits for trace analyses, and improve the overall robustness and reproducibility of their mass spectrometric methods.

The Direct Link: Ionization Voltage and Analytical Sensitivity

Fundamental Mechanisms

The ionization voltage, typically applied to the ESI sprayer or the APCI corona needle, directly influences sensitivity through several key physical processes, the balance of which determines the final signal intensity.

Droplet Charging and Taylor Cone Formation: The electrospray process begins when a high voltage (typically 2-5 kV) is applied to a liquid capillary. This charge migrates to the liquid surface, and when the electrostatic repulsion overcomes the surface tension, the liquid deforms into a Taylor cone, from which a fine mist of charged droplets is emitted. The applied voltage directly dictates the charge density on these initial droplets [4] [12]. An optimal voltage ensures a stable cone-jet mode, which is the foundation of a stable and sensitive electrospray.

Coulombic Fissions and Ion Release: As the charged droplets travel towards the mass spectrometer inlet, solvent evaporation shrinks them until their surface charge density reaches the Rayleigh limit. At this point, they undergo Coulombic fissions, disintegrating into smaller, progeny droplets. This process repeats until gas-phase analyte ions are liberated into the gas phase, ready for detection. The initial voltage setting is the primary driver of this entire desolvation and ion release sequence [4].

Avoiding Non-Ideal Spray Modes and Discharge: Excessively high voltages can induce detrimental effects. In rim emission mode, the spray becomes unstable, emanating from the rim of the capillary rather than a single Taylor cone, leading to signal fluctuation and loss of sensitivity [4] [12]. Furthermore, particularly in negative ion mode or with highly aqueous mobile phases, high voltages can cause corona discharge, a electrical breakdown of the gas surrounding the sprayer. This results in the formation of protonated solvent clusters (e.g.,

H3O+(H2O)n) and can promote unwanted redox side reactions with the analyte, thereby diminishing the target ion signal [4].

Quantitative Relationships and Observed Effects

The following table summarizes the direct, quantitative impacts of ionization voltage on key analytical figures of merit, as observed in practical applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Ionization Voltage on Analytical Performance

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Observed Effect | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spray Stability | Voltage sufficient for stable Taylor cone (e.g., ~2.2 kV for MeOH) [12] | Stable signal with <5% RSD; Unstable, fluctuating signal with poor quantification. | LC-ESI-MS with standard reversed-phase solvents [4]. |

| Ion Signal Intensity | System-specific optimum, often lower than maximum attainable voltage. | Increase in signal for target ion [M+H]+; Signal loss due to discharge or side reactions. | Optimization for Penicillin G showed a "sweet spot" for intensity [4]. |

| Detection Limits | Voltage optimized for specific analyte and mobile phase. | Lower limits of detection (LOD); Increased background and chemical noise. | APCI ion source development for pesticides achieved LODs of 1-250 pg on-column [13]. |

| Ionization Pathway | Voltage tuned to favor proton transfer vs. discharge. | Clean spectrum with predominant [M+H]+; Spectrum dominated by solvent clusters and adducts. | Appearance of H3O+(H2O)n or CH3OH2+(CH3OH)n indicates discharge in positive mode [4] [12]. |

The relationship between voltage and signal intensity is not linear; it is characterized by an optimum. A voltage that is too low fails to initiate a stable electrospray, while a voltage that is too high induces instability and discharge, both scenarios leading to a precipitous drop in sensitivity and an increase in detection limits [4].

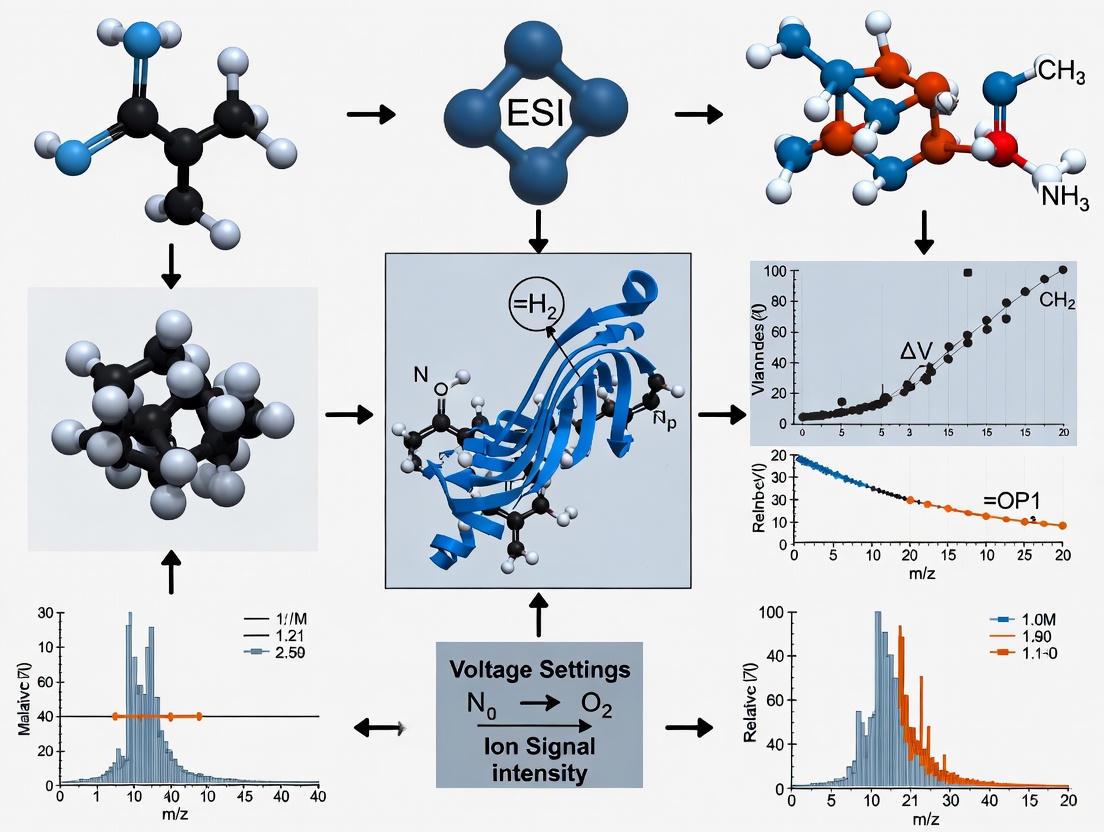

Figure 1: The direct causal pathways showing how ionization voltage influences sensitivity and detection limits through specific physical phenomena.

Experimental Protocols for Ionization Voltage Optimization

Systematic Single-Factor Optimization for ESI

This protocol provides a foundational method for establishing optimal sprayer voltage for a specific analyte or application.

Principle: To empirically determine the ionization voltage that yields the maximum stable signal for a target analyte by sequentially testing a range of voltages while holding other parameters constant.

Materials & Reagents:

- Mass spectrometer with tunable ESI source.

- Syringe pump or LC system for continuous infusion.

- Standard solution of the target analyte, prepared in a compatible solvent (e.g., 50% methanol, 0.1% formic acid) at a concentration of 1-10 µM.

- Solvent for mobile phase/infusion.

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Infuse the analyte standard directly into the ESI source at a flow rate of 5-10 µL/min using a syringe pump. Alternatively, use an isocratic LC method with a composition matching the elution conditions of the analyte.

- Baseline Parameters: Set the source temperature and desolvation gas flows to typical values (e.g., 150°C and 10 L/min for nitrogen). Set the cone voltage to a low-to-moderate value (e.g., 20-30 V) to minimize in-source fragmentation initially.

- Voltage Ramp: Select the

Spray VoltageorCapillary Voltageparameter. Starting from a low voltage (e.g., 1.5 kV for positive mode), increase the voltage in increments of 0.1 - 0.2 kV. - Signal Monitoring: At each voltage step, allow the signal to stabilize for 30-60 seconds. Record the peak area or height of the primary ion (e.g.,

[M+H]+) and monitor the signal stability (e.g., %RSD over 30 seconds). - Identify Optimum: Plot the signal intensity against the applied voltage. The optimal voltage is at the plateau just before the onset of signal instability or a marked increase in baseline noise, which indicates rim emission or discharge [4] [12].

Statistical Design of Experiments (DOE) for Complex Systems

For more complex analyses, such as the study of non-covalent protein-ligand complexes where preserving solution-phase equilibria is critical, a univariate approach is insufficient. A multivariate strategy using Design of Experiments (DOE) is required [10].

Principle: To efficiently model the response surface and identify the optimal combination of ionization voltage and other interdependent source parameters (e.g., gas flows, temperature) that maximizes the relative abundance of the intact complex.

Materials & Reagents:

- Purified protein and ligand solutions in a volatile buffer (e.g., 10-50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8-7.5).

- LC-MS system or direct infusion apparatus.

Procedure:

- Factor Selection: Identify key factors for optimization. For ESI, these typically include:

- A: Capillary / Spray Voltage

- B: Nebulizer Gas Pressure

- C: Desolvation Gas Temperature

- D: Cone Voltage / Declustering Potential

- Experimental Design: Utilize a Central Composite Design (CCI). This design efficiently explores the multi-dimensional parameter space by including factorial points, center points, and axial points, allowing for the estimation of linear, interaction, and quadratic effects [10].

- Response Measurement: For each experimental run, prepare the protein-ligand complex at a known concentration and ratio. The primary response variable (Y) is the relative ion abundance of the protein-ligand complex to the free protein (

PL/P), calculated by summing the intensities of all charge states [10]. - Data Analysis and Modeling: Use response surface methodology (RSM) software to fit a quadratic model to the experimental data. The model will reveal the significance of each factor and their interactions.

- Prediction and Verification: The software predicts the optimal parameter settings that maximize the

PL/Pratio. These predicted conditions must then be experimentally verified to confirm the performance.

- Factor Selection: Identify key factors for optimization. For ESI, these typically include:

Figure 2: Workflow for systematically optimizing ionization voltage and interdependent parameters using Design of Experiments.

Protocol for APCI Corona Needle Current Optimization

While ESI uses a sprayer voltage, APCI utilizes a corona discharge needle, and the optimal current is a key tuning parameter.

Principle: To set the corona needle current to a value that maximizes reactant ion formation for efficient chemical ionization while minimizing discharge-induced noise and analyte fragmentation.

Procedure:

- Introduce the analyte into the APCI source via GC or LC.

- Set the corona needle current to a low value (e.g., 1-2 µA).

- Gradually increase the current in steps of 0.5 µA while monitoring the signal of the protonated molecule

[M+H]+. - The optimal current is typically in the range of 2-5 µA [11]. A constant current within this range is maintained from the corona needle to ensure stable ionization conditions. Excessive current can lead to increased background and thermal degradation of the analyte [11] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ionization Voltage Optimization

| Item | Function & Rationale | Optimization Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (HPLC-MS grade water, methanol, acetonitrile) | Minimizes background ions and metal adduct formation ([M+Na]+, [M+K]+) that can distort signal distribution and complicate spectra. Essential for reproducible electrospray. |

Use plastic vials to avoid leached metal ions from glass. Low surface tension solvents (MeOH, ACN) require lower onset voltages [4] [12]. |

| Volatile Buffers (Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate) | Provides controlled pH for analyte ionization while being compatible with ESI/APCI due to high volatility, preventing source contamination and signal suppression. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 1-20 mM). Avoid non-volatile salts (e.g., phosphates, sulfates) which cause intense adducts and signal suppression [4] [10]. |

| Analyte-Specific Standard | Serves as the model compound for direct optimization of source parameters, including ionization voltage, for a specific assay. | Prepare in the mobile phase used for the analysis. Infuse at the expected elution composition to find the "sweet spot" for ion production [4] [10]. |

| Syringe Pump | Allows for direct infusion of standard solutions, enabling rapid and decoupled optimization of ionization parameters without the variability of an LC separation. | Critical for the initial single-factor optimization protocol. Provides a constant supply of analyte for stable signal monitoring during voltage ramping. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R with 'rsm' package) | Enables the design of multivariate experiments (DOE) and analysis of the resulting data via Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to find global optima. | Necessary for moving beyond one-factor-at-a-time approaches, especially for sensitive systems like protein-ligand complexes [10]. |

Ionization voltage is not an isolated parameter; its optimal setting is deeply intertwined with other source conditions and the chemical nature of the sample. A holistic view is essential for achieving the lowest possible detection limits.

Interdependence with Source Geometry and Gas Flows: The optimal sprayer position relative to the sampling cone is analyte-specific. Smaller, polar molecules benefit from the sprayer being farther from the cone, while larger, hydrophobic analytes perform better with the sprayer closer [4]. Furthermore, the efficiency of nebulization and desolvation, controlled by gas flow rates and temperatures, works in concert with the ionization voltage to determine the final ion yield. Inefficient desolvation cannot be compensated for by simply increasing the voltage.

The Role of Mobile Phase Composition: The surface tension of the mobile phase directly influences the voltage required to form a Taylor cone. Highly aqueous eluents (high surface tension) require a higher spray voltage onset, which also increases the risk of corona discharge. The addition of even 1-2% of an organic solvent like methanol or isopropanol can lower the required voltage and improve spray stability and sensitivity [4] [12]. The ionization voltage must therefore be re-optimized if the mobile phase composition is significantly altered.

In conclusion, ionization voltage is a master variable that exerts direct and powerful control over the sensitivity and detection limits in ESI and APCI mass spectrometry. A deliberate, systematic approach to its optimization—ranging from straightforward single-factor studies to sophisticated multivariate DOE—is a non-negotiable component of rigorous method development. By understanding the underlying mechanisms and applying the detailed protocols outlined in this note, researchers can reliably unlock the full performance potential of their mass spectrometric analyses, thereby accelerating discovery and development in pharmaceutical and other life science research.

In electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry, the voltage applied at the sprayer capillary is a foundational parameter that directly controls the formation of a stable spray and the efficient generation of gas-phase ions. This application note details a systematic methodology for optimizing this key variable, framed within a broader research thesis on establishing robust ESI methods. An inappropriate sprayer voltage can lead to unstable spray modes, significant signal noise, and electrical discharge, ultimately compromising quantitative accuracy and detection sensitivity [14] [12]. We provide researchers and drug development professionals with explicit protocols, quantitative data, and visual guides to navigate this critical optimization process, thereby enhancing the reliability of LC-MS data in analytical and bioanalytical applications.

The Fundamental Relationship

The electrospray process initiates when a high voltage (typically 2–5 kV) is applied to a liquid flowing through a metal capillary, forming a Taylor cone from which a fine mist of charged droplets is emitted [15] [16]. The stability of this process hangs in a delicate balance: sufficient voltage is required to overcome the liquid's surface tension and form a stable cone-jet, but excessive voltage leads to instability and electrical discharge.

- Voltage and Spray Modes: As voltage increases, the spray can transition through distinct modes. A stable cone-jet mode typically offers the best performance, characterized by a single jet producing a uniform droplet plume. Further voltage increases can induce a multi-jet mode or a rim-jet mode, which may degrade signal stability [17].

- Electrical Discharge: Particularly problematic in negative ion mode, electrical discharge (a "spark") occurs when the electric field strength is high enough to ionize the surrounding gas. This phenomenon leads to a dramatic increase in chemical noise, signal instability, and a loss of analyte sensitivity [18] [12]. Discharge can be identified by the appearance of solvent cluster ions and a sudden, erratic signal drop [14].

- The "Less is More" Principle: A guiding adage in ESI optimization is that "if a little bit works, a little bit less probably works better" [18]. Erring on the side of lower, stable voltages often yields more reproducible results and minimizes the risk of discharge and unwanted side reactions.

Experimental Protocols for Voltage Optimization

Optimizing ionization voltage is not a one-time setup but a critical step for ensuring robust method performance. The following protocols provide a framework for systematic optimization.

Protocol 1: Establishing a Stable Spray and Diagnosing Discharge

Objective: To identify the voltage window that produces a stable electrospray and to recognize the signs of electrical discharge.

Materials:

- Mass spectrometer with an adjustable ESI source.

- Syringe pump for direct infusion.

- HPLC-grade solvent (e.g., 50:50 water:methanol with 0.1% formic acid for positive mode).

- A pure standard solution (e.g., 1 µM MRFA peptide or a relevant analyte).

Method:

- Initial Setup: Infuse the standard solution directly into the ESI source at a flow rate typical for your application (e.g., 5-10 µL/min for nano-ESI or 0.2-0.5 mL/min for pneumatically-assisted ESI). Set the source temperature and desolvation gas flows to standard values.

- Voltage Ramp and Observation: Position a digital microscope to observe the spray plume if possible. While monitoring the total ion current (TIC), gradually increase the capillary voltage from 0 kV in increments of 0.1-0.2 kV.

- Identify the Onset Voltage: Note the voltage at which a stable Taylor cone and a single jet are formed. This is the onset of a stable cone-jet mode.

- Monitor for Discharge: Continue increasing the voltage while observing the TIC signal and baseline noise. A sudden increase in baseline noise and signal instability, often accompanied by visual confirmation of a spark or the mass spectral appearance of solvent cluster ions (e.g., H₃O⁺(H₂O)ₙ in positive mode), indicates electrical discharge [14] [12].

- Document the Range: Document the voltage range between the onset of a stable cone-jet and the onset of discharge.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Assessment of Signal Stability and Peak Area

Objective: To quantitatively determine the optimal voltage that provides the best compromise between signal intensity and signal stability for a target analyte.

Materials:

- LC-MS system with an autosampler.

- Standard solution of the target analyte.

- Appropriate LC column and mobile phase for isocratic or gradient elution.

Method:

- Chromatographic Separation: Develop an LC method where the analyte elutes with a reasonable retention time.

- Iterative Data Acquisition: Make repetitive injections of the standard at different, fixed capillary voltages. The voltage should be varied in a systematic way (e.g., from 2.0 kV to 3.5 kV in 0.1 or 0.2 kV steps) [19].

- Data Analysis: For each injection, calculate the chromatographic peak area and the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the signal intensity across the peak.

- Determine the Optimum: Plot the peak area and signal RSD against the applied voltage. The optimal voltage is typically identified as the point where the peak area is maximized and the RSD is minimized, just below the onset of instability [19].

Key Data and Observations

The following tables consolidate critical experimental data and observations from the literature and internal studies to guide the optimization process.

Table 1: Impact of Sprayer Voltage on Key MS Performance Metrics

| Spray Voltage (kV) | Spray Mode Observed | Relative Peak Area | Signal Noise Level | Observed Phenomena |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | Unstable / Pulsating | 100 (Baseline) | High | Large, irregular droplets; low ionization efficiency [19] |

| 2.5 | Stable Cone-Jet | 138 | Low | Optimal Taylor cone; stable signal [19] |

| 3.0 | Multi-Jet / Rim-jet | 125 | Moderate | Multiple emission points; increased signal variance [17] |

| >3.5 | Rim-jet / Discharge | 90 (or signal loss) | Very High | Electrical discharge; signal suppression and instability [12] |

Table 2: Threshold Electrospray Voltages for Common Solvents [12]

| Solvent | Surface Tension (dyne/cm) | Typical Onset Voltage (kV) |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol | 22.5 | 2.2 |

| Isopropanol | 21.8 | 2.0 |

| Acetonitrile | 19.1 | 2.5 |

| Water | 72.8 | 4.0 |

Visualizing the Optimization Workflow and Spray Modes

The logical relationship between voltage adjustment and the resulting spray state can be visualized through the following workflow and spray mode diagrams.

Diagram 1: ESI Voltage Optimization Workflow. This logic flow guides the systematic tuning of the sprayer voltage to identify the stable operating window.

Diagram 2: ESI Spray Mode Transitions. Visual representation of how spray morphology changes with increasing voltage, from unstable spray to optimal cone-jet and finally to destructive discharge.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for ESI Voltage Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Solution | Provides a consistent signal for evaluating intensity and stability. | MRFA peptide; a drug compound standard. Use a concentration in the linear dynamic range [19]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Ensure low chemical background and consistent surface tension. | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water (with 0.1% Formic Acid). Low surface tension solvents (ACN, MeOH) require lower onset voltages [12]. |

| Syringe Pump | Allows for direct infusion of standard solutions, isolating the ESI process from LC variability. | A pump capable of delivering flow rates from µL/min to mL/min. |

| Digital Microscope | Enables visual inspection and confirmation of the spray plume and spray mode. | A Dino-lite digital microscope is suitable for observing cone-jet formation and instability [17]. |

| Inert Gas Supply | Serves as the drying/nebulizing gas for stable spray formation. | High-purity nitrogen is standard. Optimizing gas flow and temperature is crucial for desolvation [12]. |

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the successful transfer of analytes from the liquid phase to the gas phase as ions is not merely a function of the instrument's capabilities, but is profoundly influenced by the synergistic relationship between the mobile phase composition and the applied electrospray voltage. The establishment of a stable electrospray is a delicate balancing act, governed by the physical properties of the solvent system, which are in constant flux during gradient elution liquid chromatography (LC) [3]. This application note delineates a systematic methodology for optimizing ionization voltage by treating the mobile phase not as a passive carrier, but as an active participant in the ionization process. We provide a detailed experimental protocol, complete with quantitative data and visualization tools, to guide researchers in harnessing solvent effects for enhanced MS sensitivity and signal stability.

Theoretical Foundation: The Electrospray Process and Solvent Properties

The electrospray ionization mechanism initiates with the application of a high voltage to a liquid, generating a fine aerosol of charged droplets at the capillary tip [16]. These droplets undergo desolvation and Coulomb fissions, eventually leading to the release of gas-phase ions [20]. The stability and efficiency of this entire process are critically dependent on the physical-chemical properties of the mobile phase, which directly influence the electric field required for its initiation and maintenance.

Key Solvent Properties Governing Electrospray:

- Surface Tension (γ): Lower surface tension solvents (e.g., methanol, isopropanol) facilitate the formation of a stable Taylor cone and require a lower onset voltage for electrospray, as the electrostatic forces can more easily overcome the surface tension of the liquid [4].

- Dielectric Constant: A solvent must possess a sufficiently high dielectric constant to allow for the separation of charge, which is essential for the electrospray process [18].

- Vapor Pressure: Solvents with higher vapor pressures (e.g., acetonitrile) evaporate rapidly from charged droplets, aiding in the shrinkage of droplets and the efficient release of gas-phase ions [18].

- Conductivity: The presence of electrolytes (e.g., acids, salts) increases the solution's conductivity, promoting the formation of charged droplets. However, excessive salts can lead to adduct formation and signal suppression [4].

During a reversed-phase LC gradient, the mobile phase transitions from an aqueous-rich to an organic-rich composition. This evolution concurrently alters the aforementioned solvent properties, thereby shifting the optimal voltage window for stable electrospray operation [3]. Operating at a voltage that is too low for the current solvent composition may result in an unstable spray or failure to initiate. Conversely, a voltage that is too high can induce electrical discharge, particularly in negative ion mode, or promote unwanted electrochemical side reactions, leading to increased noise and signal irreproducibility [18] [4].

Quantitative Data: Solvent Properties and Their ESI-MS Performance

The following tables summarize key solvent properties and their established performance in ESI-MS, providing a reference for predicting optimal voltage settings.

Table 1: Physical Properties of Common LC-ESI-MS Solvents and Their General ESI Suitability

| Solvent | Surface Tension (mN/m, approx. 20°C) | Vapor Pressure (kPa, approx. 20°C) | Dielectric Constant (approx.) | ESI Suitability & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 72.8 | 2.3 | 80.1 | High surface tension requires higher spray voltages; often mixed with organic modifiers [4]. |

| Acetonitrile | 29.3 | 11.8 | 35.9 | Excellent; low surface tension, high vapor pressure. One of the best ESI solvents [21] [18]. |

| Methanol | 22.6 | 12.9 | 32.7 | Very good; low surface tension promotes stable Taylor cone formation [4]. |

| Isopropanol | 21.7 | 4.4 | 18.3 | Good; can be added (1-2%) to highly aqueous eluents to lower surface tension [4]. |

| Acetone | 23.7 | 24.7 | 20.7 | Found to be one of the best solvents for providing intense ESI-MS signals [21]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 26.4 | 17.6 | 7.6 | Found to be one of the best solvents for providing intense ESI-MS signals [21]. |

| Dichloromethane | 26.5 | 58.2 | 9.1 | Found to be one of the best solvents for providing intense ESI-MS signals [21]. |

| Trifluorotoluene | ~22 | ~3.6 | ~9.2 | A promising new ESI-MS solvent with good performance [21]. |

Table 2: Experimentally Determined ESI-MS Signal Performance of Various Solvents Data adapted from a systematic study testing 14 solvents for their ability to provide strong ESI-MS signals for permanently charged ions [21].

| Solvent Classification | Solvent | Relative ESI-MS Signal Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Best Performers | Acetonitrile | Among the best for intense signals |

| Acetone | Among the best for intense signals | |

| Dichloromethane | Among the best for intense signals | |

| Tetrahydrofuran | Among the best for intense signals | |

| Trifluorotoluene | Promising, high performance | |

| Common & Suitable | Methanol | Good performance |

| Isopropanol | Good performance with low surface tension | |

| Requires Careful Optimization | Water (highly aqueous) | Capable of signal but prone to instability; benefits from modifiers |

The relationship between solvent composition, its physical properties, and the required operational voltage is a dynamic system. The diagram below illustrates the core logical workflow for matching electrospray voltage to the mobile phase.

Figure 1: Logical workflow for determining initial ESI voltage settings based on mobile phase composition.

Experimental Protocols for Voltage Optimization

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for establishing the optimal electrospray voltage for a given LC-ESI-MS method, with a focus on accounting for solvent composition changes during a gradient.

Protocol 1: Initial Static Optimization via Infusion

Objective: To determine a baseline voltage for a specific solvent composition, typically the starting point of a gradient.

Materials & Reagents:

- Standard Solution: Prepare a solution of your analyte at a relevant concentration in the initial mobile phase (e.g., 95% Solvent A, 5% Solvent B).

- Syringe Pump: For continuous infusion of the standard solution.

- LC-ESI-MS System: Mass spectrometer with tunable source parameters.

Procedure:

- Infuse the standard solution directly into the ESI source at the method's flow rate, bypassing the LC column.

- Set initial source parameters based on instrument manufacturer recommendations (e.g., desolvation gas temperature and flow, nebulizer gas flow).

- Select a starting voltage (e.g., 2.5 kV for positive mode) and monitor the base peak intensity or the signal for a specific ion of interest.

- Systematically increment the voltage in steps of 0.1 - 0.2 kV.

- Record the signal intensity and stability (e.g., by the Signal-to-Noise ratio or the relative standard deviation of the signal over 1-2 minutes) at each voltage step.

- Identify the optimal voltage range: The goal is the lowest voltage that provides a stable, intense signal. As advised in the literature, "if a little bit works, a little bit less probably works better" [18]. Avoid the upper plateau where discharge or instability may begin.

- Repeat the process for the final mobile phase composition (e.g., 5% Solvent A, 95% Solvent B). This will establish the voltage range required throughout the gradient.

Protocol 2: Dynamic Optimization for Gradient Elution LC-MS

Objective: To account for changing solvent composition during a gradient and either select a single, robust constant voltage or implement a voltage gradient.

Materials & Reagents:

- Test Sample: A mixture containing your analytes.

- LC System: Configured with the intended gradient method.

- ESI-MS System: Capable of monitoring spray current and/or allowing programmable voltage changes during a run.

Procedure: A. Feedback-Based Optimization via Spray Current

- Run the LC gradient with the MS detector off or in a non-acquisition mode, but with the ESI voltage applied.

- Monitor the spray current in real-time. The spray current is a direct indicator of electrospray health [3].

- Observe the current trend. Typically, the current will increase as the organic solvent percentage increases due to changes in conductivity and viscosity.

- Identify anomalies. A sudden drop or high noise in the current indicates an unstable spray regime (e.g., discharge or rim emission) [3].

- Adjust the applied voltage until the spray current is stable and relatively smooth throughout the entire gradient run. This voltage may be a compromise but ensures continuous operation.

B. Establishing a Programmable Voltage Gradient

- Based on Protocol 1 and the findings from A, define a voltage program that correlates with the LC gradient timetable.

- Start at the higher voltage optimal for the aqueous beginning of the gradient.

- Program a linear or stepwise decrease in voltage as the organic modifier increases. For example, if the organic phase increases from 5% to 95% over 20 minutes, the voltage might be programmed to decrease from 3.5 kV to 2.0 kV over the same period.

- Validate the method by running the sample and comparing the signal stability and intensity across the chromatogram against a constant-voltage method.

The dynamic process of a gradient elution and its impact on the electrospray is complex. The following diagram maps the experimental workflow and the cause-effect relationships involved in optimizing for this condition.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for optimizing ESI voltage during a gradient elution, highlighting the cause-effect relationships and the strategy for dynamic adjustment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for ESI Voltage Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function / Role in Optimization | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol) | High-purity solvents minimize chemical noise and ion suppression, providing a clean baseline for accurately assessing signal intensity and stability. | Avoid using "HPLC-grade" solvents that may contain non-volatile additives which can contaminate the source [4]. |

| Volatile Mobile Phase Additives (e.g., Formic Acid, Acetic Acid, Ammonium Acetate) | Promotes analyte ionization (e.g., by protonation) and increases solution conductivity, aiding electrospray formation. | Use at low concentrations (0.1% - 0.2%). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) can cause ion suppression due to strong ion-pairing [18]. |

| Fused Silica or Coated ESI Emitters | The conduit from which the electrospray is generated. Its diameter and condition affect the flow rate regime and spray stability. | Nano-electrospray emitters (<10 µm i.d.) are ideal for low flow rates (<1 µL/min) and offer superior ionization efficiency [20]. |

| Syringe Pump | For direct infusion experiments during initial static optimization (Protocol 1). | Provides a pulseless, consistent flow essential for stable spray and accurate voltage assessment. |

| Conductive Vials (e.g., Polypropylene) | Sample containers that minimize the introduction of metal cation adducts (e.g., [M+Na]+). | Glass vials can leach metal ions, leading to unwanted adducts in the mass spectrum [4]. |

| Standard Reference Compounds (e.g., Caffeine, MRFA peptide, Ultramark) | Well-characterized compounds used to benchmark instrument performance and optimize source parameters. | Allows for consistent tuning and comparison of results across different days and instruments. |

Concluding Recommendations

Optimizing the electrospray voltage in concert with the mobile phase composition is a critical step in developing a robust and sensitive LC-ESI-MS method. The prevailing adage in the field, "if a little bit works, a little bit less probably works better," is a prudent guide for voltage selection, favoring stability over maximized signal at the risk of discharge [18]. For gradient elution methods, a single, carefully chosen constant voltage is often sufficient, but for methods requiring maximum performance across the entire chromatogram, a programmable voltage gradient is a powerful strategy. By adopting the systematic, solvent-centric approach outlined in this application note, researchers can significantly improve data quality, reproducibility, and the overall success of their ESI-MS analyses.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a cornerstone technique in mass spectrometry for analyzing biomolecules and metabolites. While the primary goal of voltage optimization is often maximizing signal intensity, a more nuanced effect lies in its control over spectral complexity. The applied voltage directly influences the electrochemical environment within the ESI source, thereby governing the formation of various ion species beyond the simple protonated or deprotonated molecule. This includes the generation of adducts (e.g., [M+Na]⁺, [M+K]⁺), in-source fragments, and multiply charged ions, which collectively increase spectral complexity and can complicate data interpretation [22]. Understanding and controlling this voltage-dependent phenomenon is therefore not merely a matter of sensitivity, but a critical step for achieving cleaner spectra and more accurate metabolite annotation in untargeted studies. This application note details protocols for systematically investigating voltage effects to optimize spectral quality and minimize analytical ambiguity.

Key Concepts and Voltage Relationships

The electrical potential applied to the ESI emitter is a key variable in the ionization process. It affects the charging of the liquid droplet, the efficiency of droplet desolvation, and the final emission of gas-phase ions. The mechanism of adduct formation is intrinsically linked to these processes.

Alternating Current (AC) vs. Direct Current (DC) ESI: The operational voltage ranges and spray characteristics differ significantly between AC and DC ESI. AC ESI, which utilizes a sinusoidal potential, creates a much narrower spray cone (approximately 12° half-angle) compared to DC ESI (approximately 49° half-angle) due to a mechanism called "preferential entrainment" [23]. However, AC ESI is more susceptible to gas discharges, limiting its operable voltage range. Stable operation for AC ESI is often achieved between 200-1000 V amplitude, whereas DC ESI can typically function effectively at higher potentials (2-3 kV) [23]. This voltage ceiling can limit the absolute signal intensity achievable with AC ESI, which may be 1-2 orders of magnitude lower than optimized DC ESI.

Adduct Formation and Complexity: In untargeted metabolomics, a single metabolite can generate multiple features in the mass spectrum with different m/z values but the same retention time. This complexity arises from the ESI source acting as an electrochemical reactor, producing a variety of ions including adducts, isotopic peaks, and in-source fragments [22]. A large-scale characterization of 142 data sets revealed 271 distinct m/z differences relating to feature pairs from the same metabolite, with a core set of 32 occurring in over 50% of studies [22]. The table below summarizes some commonly observed feature types.

Table 1: Common Feature Types Contributing to Spectral Complexity in ESI-MS

| Feature Type | Description | Example m/z Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Adducts | Ions formed by the association of the analyte with other ions (e.g., from solvent or mobile phase). | +22 Da (Na⁺), +38 Da (K⁺) |

| In-Source Fragments | Ions produced by the fragmentation of the analyte within the ion source. | -18 Da (H₂O loss), -44 Da (CO₂ loss) |

| Multiply Charged Ions | Analytes that have acquired more than one charge, common in proteins and peptides. | m/z = (M+2H)²⁺, (M+3H)³⁺ |

| Neutral Losses | Loss of an uncharged molecule from a charged ion. | Specific to functional groups |

Quantitative Data on Voltage and Performance

A comparative study of AC and DC ESI provides quantitative insight into how voltage constraints impact analytical figures of merit. The use of an electronegative nebulizing gas like sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) can extend the operating voltage range of AC ESI by approximately 50% by suppressing gas discharges, though this does not necessarily translate to appreciably higher signal intensities [23].

The optimal performance is analyte-dependent. For instance, in the analysis of the peptide MRFA, AC ESI utilizing SF₆ provided the best limits of detection (LOD), nearly an order of magnitude lower than DC ESI with nitrogen (N₂) and half that of DC ESI with SF₆ [23]. Conversely, for caffeine, DC ESI outperformed AC ESI, indicating that the benefits of a particular ionization mode and voltage setting can be compound-specific [23]. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from this study.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of AC ESI and DC ESI under Optimized Conditions

| Parameter | AC ESI (with N₂) | AC ESI (with SF₆) | DC ESI (with N₂) | DC ESI (with SF₆) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Voltage Range | 200 - 1000 V (amplitude) | ~50% wider than with N₂ [23] | 2000 - 3000 V [23] | Similar to N₂ range |

| Absolute Signal Intensity | Lower (at peak voltages) | Not appreciably improved | 1-2 orders of magnitude greater than AC ESI [23] | High |

| Signal-to-Background | Comparable to DC ESI, qualitatively cleaner spectra [23] | Comparable | Comparable to AC ESI | Comparable |

| LOD for MRFA | Not the best | Best (½ of DC SF₆, 1/10 of DC N₂) [23] | Worst | Intermediate (2x AC SF₆) |

| LOD for Caffeine | Not the best | Not the best | Best | Not the best |

Furthermore, the transferability of ionization efficiency (IE) scales between different MS instruments has been demonstrated [24]. While the general trends of how molecular structure affects IE remain consistent, the numerical logIE values can vary, with root mean squared differences between instruments ranging from 0.21 to 0.55 log units [24]. This underscores that while voltage optimization is universally critical, the specific optimal value may be instrument-dependent.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Voltage Optimization for Minimal Adduct Formation

Primary Objective: To identify the ESI voltage that minimizes adduct-related spectral complexity while maintaining sufficient signal intensity for a target analyte.

Materials and Reagents:

- Standard solution of target analyte (e.g., caffeine, MRFA) at a known concentration (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL).

- HPLC-grade solvents and mobile phase additives (e.g., 0.1% formic acid).

- Internal standard (e.g., asparagine) [23].

- Mass spectrometer with ESI source and direct infusion capability.

Procedure:

- System Setup: Tune the mass spectrometer's ion optics parameters using a calibration mix and keep these parameters constant for the entire experiment [23]. Mount the ESI emitter at a fixed distance (e.g., 5 mm) from the mass spectrometer inlet.

- Direct Infusion: Introduce the analyte solution via direct infusion at a constant flow rate (e.g., 500 nL/min) [23].

- Voltage Ramp: For DC ESI, incrementally increase the applied voltage (e.g., in 100 V steps) from a low starting point (e.g., 1 kV) up to the point of instability or gas discharge. For each voltage, allow the signal to stabilize for 2-3 minutes.

- Data Acquisition: At each voltage step, acquire mass spectra for a set period (e.g., average 40 scans) [23]. Ensure the automatic gain control and maximum injection times are held constant.

- Data Analysis: For each voltage, extract the following:

- Absolute intensity of the target ion (e.g., [M+H]⁺).

- Intensities of all major adduct ions (e.g., [M+Na]⁺, [M+K]⁺).

- Calculate the ratio of the target ion intensity to the sum of all major adduct intensities (Target-to-Adduct Ratio).

- Optimization: Plot the Target-to-Adduct Ratio and the absolute target ion intensity against the applied voltage. The optimal voltage is typically at the point where the Target-to-Adduct Ratio is maximized, yet the absolute intensity remains acceptable for sensitivity requirements.

Protocol 2: Characterization of Voltage-Dependent Spectral Complexity in a Mixture

Primary Objective: To profile the formation of different feature types (adducts, fragments) across a voltage gradient for a complex mixture.

Materials and Reagents:

- Complex standard mixture or representative biological extract.

- HPLC system coupled to MS.

- Data processing software capable of peak picking and correlation analysis (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL).

Procedure:

- LC-MS Analysis: Inject the sample and run a chromatographic separation. At set time intervals during the run (or in subsequent runs), automatically step the ESI voltage through a pre-defined range.

- Data Processing: Process the raw data to extract all m/z-retention time features.

- Feature Correlation Pairing: For data acquired at each voltage, within overlapping retention time windows (e.g., 2s width, 1s overlap), calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient and the m/z difference for all possible feature pairs [22].

- Filtering: Filter the resulting pairs to retain those with a high correlation (e.g., ≥0.5), statistical significance (p-value ≤0.05), and presence in a sufficient proportion of samples (e.g., ≥30%) [22].

- Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation (GKDE): Perform GKDE on the m/z distances from the filtered pairs to identify the most common m/z differences present at each voltage. This reveals the predominant adducts and neutral losses [22].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the GKDE results across the voltage gradient. The voltage that produces the simplest spectrum (fewest dominant m/z differences) or the most reproducible adduct profile is a candidate for optimized untargeted screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for ESI Voltage Optimization Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Stainless Steel Emitter | The electrode through which high voltage is applied to the analyte solution. A 50 µm internal diameter is common [23]. |

| Calibration Tune Mix | A standard solution (e.g., caffeine, MRFA, Ultramark 1621) for tuning ion optics and calibrating the mass spectrometer before experiments [23]. |

| Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF₆) | An electronegative nebulizing gas that suppresses gas discharges, allowing for a wider operable voltage range, particularly in AC ESI [23]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., Asparagine) | Added to samples to monitor signal consistency and perform normalization during quantitative LOD analyses [23]. |

| Function Generator & RF Amplifier | Essential equipment for generating and amplifying the high-frequency sinusoidal potential required for AC ESI experiments [23]. |

| High-Voltage DC Power Supply | Provides the stable, direct current high voltage for conventional DC ESI experiments [23]. |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for optimizing ESI voltage based on analytical goals, integrating the concepts and protocols described in this document.

Diagram 1: ESI Voltage Optimization Workflow

Voltage optimization in ESI-MS is a critical step that extends far beyond simple signal maximization. As demonstrated, the applied voltage directly influences the electrochemical processes that lead to adduct formation and increased spectral complexity. A systematic approach to voltage optimization, as outlined in the provided protocols, allows researchers to make an informed trade-off between sensitivity and spectral cleanliness. By adopting these practices, scientists can develop more robust and interpretable LC-MS methods, leading to greater confidence in metabolite annotation and quantitative analysis in fields ranging from drug development to untargeted metabolomics.

Systematic Strategies for Ionization Voltage Optimization in Method Development

The achievement of optimal sensitivity and robustness in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) is fundamentally rooted in the meticulous optimization of the ion source. The ionization voltage, among other source parameters, directly influences the efficiency with which analyte molecules are converted into gas-phase ions, impacting the ultimate detection limit of the method [6]. Within the broader thesis on method development for optimizing ionization voltage in ESI research, two distinct philosophical approaches emerge: the traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) strategy and the multivariate statistical approach known as Design of Experiments (DoE). The choice between these paths is not merely a procedural detail but a strategic decision that affects the efficiency, reliability, and depth of understanding of the optimization process. This application note delineates the conceptual and practical differences between OVAT and DoE, providing researchers and drug development professionals with clear protocols to implement a modern, quality-by-design (QbD) approach in their ESI-MS method development.

Fundamental Principles: OVAT versus DoE

The Traditional OVAT Approach

The OVAT strategy, also referred to as OFAT (one-factor-at-a-time), is a univariate procedure where the effect of a tested parameter is assessed by changing its level while keeping all other factors constant at a nominal value [8]. For instance, a researcher might optimize the capillary voltage across a range of values while holding factors like nebulizer gas pressure, drying gas flow rate, and temperature fixed. After identifying a putative optimal voltage, they would then proceed to optimize the next parameter, such as gas temperature, again while holding all others constant, including the newly "optimized" voltage.

Inherent Limitations: While intuitively straightforward, this method carries significant drawbacks. It explores only a small fraction of the total experimental domain and, most critically, fails to account for potential interactions between factors [8] [25]. An interaction occurs when the effect of one factor (e.g., ionization voltage) depends on the level of another factor (e.g., nebulizer pressure). The OVAT procedure is also inefficient, often requiring a high number of experimental runs to probe the design space inadequately [8].

The Multivariate DoE Framework

Design of Experiments (DoE) is a chemometrics-based, multivariate technique that systematically varies multiple factors simultaneously according to a predefined experimental plan [8] [26]. The core strength of DoE is its ability to efficiently determine significant experimental variables, build mathematical models for the responses, and identify optimal factor settings from a minimum number of experiments [8].

- Factorial Designs: Used for screening to identify which factors among many have a significant influence on the response.

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Used for optimization after screening. Designs like Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD) are employed to model curvature and locate a true optimum [8] [10].

- Key Advantage: DoE quantitatively measures the effects of individual factors and, crucially, the interactions between them. This provides a more comprehensive understanding of the system and often leads to more robust and superior optimal conditions compared to OVAT [8] [27] [25].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the distinct steps and logical flow for both optimization strategies.

Comparative Analysis: A Side-by-Side Evaluation

The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of the OVAT and DoE approaches across several critical dimensions for ESI optimization.

Table 1: A direct comparison of OVAT and DoE optimization strategies.

| Characteristic | One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) | Multivariate Design of Experiments (DoE) |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires a high number of runs [8]. | High; maximum information from a minimum number of runs [8] [26]. |

| Handling of Factor Interactions | Cannot detect or quantify interactions [8] [25]. | Explicitly measures and models interactions between factors [8] [27]. |

| Modeling Capability | No mathematical model of the system is built. | Builds a quantitative mathematical model (e.g., quadratic) for the response [8] [27]. |

| Risk of Finding False Optimum | High, due to ignored interactions [25]. | Low; a robust optimum is found by considering the entire design space [26]. |

| Underlying Assumption | Assumes factors are independent (no interactions). | Makes no assumption of independence; tests for interactions. |

| Best Application Context | Quick, preliminary checks of a very limited number of factors. | Rigorous method development for robustness, QbD, and understanding complex systems. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Case Study: DoE for LC-MS/MS Metabolite Analysis

A study aimed at the simultaneous quantification of 18 metabolites in human urine provides a robust protocol for DoE application in ESI optimization. The goal was to improve the response of 7-methylguanine (positive mode) and glucuronic acid (negative mode), which had the poorest ionization characteristics [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials used in the featured LC-MS/MS metabolomics study.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Source Example |

|---|---|---|

| 7-Methylguanine & Glucuronic Acid | Model compounds representing analytes with poor ionization efficiency for optimization. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade) | Mobile phase component; ensures low background noise and high MS compatibility. | J.T. Baker |

| Acetic Acid (≥99.7%) | Mobile phase additive (0.06%) to promote ionization in negative and positive modes. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Human Urine Samples | Complex biological matrix for testing the applicability of the optimized method. | N/A |

| Ammonium Acetate | Common volatile buffer for LC-MS to control pH without suppressing ionization. | Fluka [10] |

Protocol 1: Multivariate DoE Optimization Workflow

- Factor Selection and Level Definition: Select key ESI source parameters and define their experimental ranges based on instrument limits and preliminary knowledge. In the case study, the factors were: Capillary Voltage (2000–4000 V), Nebulizer Pressure (10–50 psi), Drying Gas Flow Rate (4–12 L/min), and Drying Gas Temperature (200–340 °C) [8].

- Screening Design (Optional but Recommended): For studies with many factors (>4), begin with a screening design like a two-level Fractional Factorial Design (FFD). This identifies which factors have a significant effect on the response (e.g., MS signal intensity) with a minimal number of runs, allowing you to focus on the critical parameters in subsequent steps [8].

- Optimization Design: Use a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design to model curvature and locate the optimum. Apply a Face-Centered Central Composite Design (CCD) or a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) to the significant factors identified in the screening phase [8].

- Experimental Execution: Prepare a standard solution of the target analytes at a relevant concentration. Run the experiments in a randomized order as dictated by the design matrix to minimize the impact of external biases and instrumental drift [8] [26].

- Data Analysis and Model Fitting: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Modde Pro, R) to perform analysis of variance (ANOVA) and fit a mathematical model (e.g., a quadratic polynomial) to the response data. The software will output coefficients for each factor and their interactions, indicating the magnitude and direction of their effect [8].

- Visualization and Optimization: Generate response surface plots from the model to visualize the relationship between two factors and the response. Use the model's optimization function to pinpoint the factor settings that maximize the desired response (e.g., signal intensity) [8].

- Verification: Confirm the predicted optimum by performing a verification run under the suggested conditions. Apply the final optimized settings to the analysis of real samples, such as human urine in the case study, to validate method performance [8].

Protocol for a Basic OVAT Optimization

For comparative purposes, a standard OVAT protocol is outlined below.

Protocol 2: One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) Procedure

- Establish Baseline: Set all ESI parameters (capillary voltage, gas flows, temperature, etc.) to the instrument manufacturer's default or a sensible mid-range value.

- Optimize First Factor: Infuse a standard solution of your analyte. Vary the first factor (e.g., capillary voltage) in small increments over its practical range while monitoring the MS response (e.g., peak area or height in Total Ion Chromatogram or Extracted Ion Chromatogram).

- Set and Proceed: Note the value of the first factor that yields the highest response. Set this factor to that value and do not change it for the remainder of the procedure.

- Iterate: Move to the next factor (e.g., nebulizer pressure). Vary it across its range while holding all others constant, including the previously optimized voltage.

- Repeat: Continue this process sequentially until all factors of interest have been tested and set to their individual "best" values.

The choice between OVAT and DoE is a strategic one with significant implications for the quality and efficiency of an ESI-MS method. While the OVAT approach is conceptually simple, its inability to account for factor interactions and its inefficiency make it suboptimal for rigorous method development, especially for complex matrices or multi-analyte methods [8] [25].

The multivariate DoE approach, while requiring initial planning and statistical analysis, provides a superior path. It delivers a deeper understanding of the ionization process, efficiently uncovers optimal and robust operating conditions, and aligns with modern QbD principles mandated in regulated industries like pharmaceutical development [8] [26] [27]. For researchers seeking to maximize sensitivity, ensure robustness, and build a scientifically defensible method, DoE is the unequivocally recommended optimization path.

Implementing Design of Experiments (DoE) for Efficient Multi-Parameter Optimization

Optimizing Electrospray Ionization (ESI) for mass spectrometry is a complex challenge, as ionization efficiency is influenced by multiple interacting parameters. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches are inefficient for this multi-parameter system and often fail to reveal critical parameter interactions [26]. Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a systematic, statistical framework that enables researchers to efficiently explore these complex relationships using a minimal number of experiments, leading to more robust and optimized ESI methods [10] [28].

The fundamental advantage of DoE in ESI research lies in its ability to simultaneously vary multiple factors according to a predetermined experimental plan, allowing for the identification of not only main effects but also interaction effects between parameters [29]. This approach is particularly valuable when optimizing ESI conditions for specific applications, such as protein-ligand binding studies where preserving solution-phase equilibria is crucial [10], or for analyzing complex mixtures like oxylipins where different chemical classes exhibit distinct ionization behaviors [28].

DoE Experimental Design and Workflow

Key Experimental Design Strategies

Several DoE designs are particularly relevant for ESI optimization, each with specific applications and advantages:

Central Composite Design (CCD): This response surface methodology is ideal for modeling curvature in response surfaces and identifying optimal parameter settings. CCD includes factorial points, center points, and axial points, providing comprehensive information about factor effects and interactions. It has been successfully applied to optimize SFC separation conditions for lipids [29] and to enhance metabolite detection in data-dependent acquisition modes [30].

Fractional Factorial Designs: These designs are valuable for screening a large number of factors to identify the most influential parameters, thereby reducing experimental burden in initial optimization phases [28].

Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Following screening designs, RSM enables detailed modeling of the relationship between factors and responses, facilitating the identification of optimal operating conditions [10].

The table below summarizes the key design approaches and their applications in analytical chemistry:

Table 1: DoE Design Strategies for ESI Optimization

| Design Type | Key Characteristics | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | Models curvature, identifies optimal conditions with 3-5 levels per factor | SFC separation of lipids [29]; Metabolite coverage in DDA mode [30] |

| Fractional Factorial | Screens many factors efficiently with reduced experiments | Initial optimization of oxylipin ionization [28] |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) | Models relationship between factors and responses | Protein-ligand complex optimization [10]; SFC-MS separation [29] |

| Inscribed Central Composite (CCI) | Used when factor limits represent instrumental boundaries | ESI source optimization for protein-ligand complexes [10] |

Comprehensive DoE Workflow for ESI Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for implementing DoE in ESI parameter optimization:

Figure 1: DoE Workflow for ESI Optimization

This workflow begins with clearly defined optimization objectives, such as maximizing signal intensity, improving signal-to-noise ratios, or preserving protein-ligand complexes [10]. Subsequent stages involve identifying critical factors, selecting appropriate experimental designs, executing experiments, performing statistical analysis, and validating the optimized conditions.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

ESI Parameter Optimization Using Central Composite Design

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for systematic optimization of ESI parameters using a Central Composite Design, adapted from published approaches for protein-ligand complexes [10] and lipid analysis [29].

Materials and Equipment

- Mass spectrometer with ESI source

- Syringe pump or LC system for sample introduction

- Analytical standards of target compounds

- Appropriate solvents and mobile phase additives

Step-by-Step Procedure

Factor Selection and Range Determination

- Select critical ESI parameters for optimization based on preliminary experiments or literature data. Common factors include capillary voltage, drying gas temperature, nebulizer gas pressure, and sheath gas flow rate [26] [10].

- Define practical ranges for each factor based on instrument limitations and preliminary experiments.

Experimental Design Implementation

- Generate a Central Composite Design using statistical software (e.g., R, Design-Expert, or Modde Pro).

- For 4 factors, a typical CCD requires 24-30 experimental runs, including factorial points, axial points, and center points [10].

- Randomize the run order to minimize systematic error.

Sample Preparation and Analysis

- Prepare standard solutions at appropriate concentrations in relevant matrix.

- For protein-ligand studies, prepare solutions with fixed protein concentration and varying ligand concentrations [10].

- Analyze samples according to the experimental design, ensuring system equilibration between runs.

Response Measurement

Data Analysis and Model Building

- Perform statistical analysis using Response Surface Methodology.

- Identify significant factors and interaction effects through ANOVA.

- Generate contour plots and response surfaces to visualize factor relationships.