Adduct Formation in Electrospray Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This article provides a thorough examination of adduct formation in Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS), a critical phenomenon for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Adduct Formation in Electrospray Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a thorough examination of adduct formation in Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS), a critical phenomenon for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores fundamental mechanisms and common adduct species, details methodological applications for enhancing analytical capabilities, offers practical troubleshooting strategies for sensitivity and contamination issues, and presents validation techniques through comparative analysis with other ionization methods. By synthesizing current research and practical guidelines, this resource aims to empower professionals to strategically control, exploit, and troubleshoot adduct formation to improve data quality and analytical outcomes in biomedical and clinical research.

The What and Why of ESI Adducts: Core Mechanisms and Common Species

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the ionized species observed extend far beyond the simple protonated molecule [M+H]+ or deprotonated molecule [M-H]-. According to IUPAC recommendations, adduct ions are defined as "ions formed by the interaction of a precursor ion with one or more atoms or molecules to form an ion containing all the constituent atoms for the precursor ion as well as the additional atoms from the associated atoms or molecules" [1]. These adducts form through the association of the analyte (M) with various cations, anions, or neutral molecules present in the sample solution or mobile phase. In the context of electrospray research, understanding adduct formation is crucial as these species represent a fundamental aspect of the ionization mechanism, influencing everything from detection sensitivity to spectral interpretation [1] [2]. The formation of adducts is not merely an artifact but a complex process governed by equilibria in charged nanodroplets, which can be manipulated to analytical advantage but is often difficult to control [3] [2]. This technical guide delves into the nature, formation, and implications of adduct ions, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging these species in analytical methodologies.

Adduct Ion Formation Mechanisms and Electrospray Fundamentals

The Electrospray Ionization Process and Droplet Chemistry

Electrospray ionization operates by applying a high voltage to a liquid sample, dispersing it into a mist of highly charged droplets at atmospheric pressure [4] [5]. As these droplets travel towards the mass spectrometer inlet, solvent evaporation leads to droplet shrinkage and an increasing surface charge density. Eventually, the electric field strength within the charged droplet reaches a critical point where ions at the surface are ejected into the gaseous phase [5]. This soft ionization technique is particularly effective for polar, nonvolatile, and thermally labile molecules, including large biomolecules, as it produces gas-phase ions with minimal fragmentation [4]. The process preserves very weak noncovalent interactions in the gas phase and enables the analysis of high molecular weight compounds through the generation of multiply charged ions, which reduces their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) to within the measurable range of common mass analyzers [4].

Competitive Equilibria Governing Adduct Formation

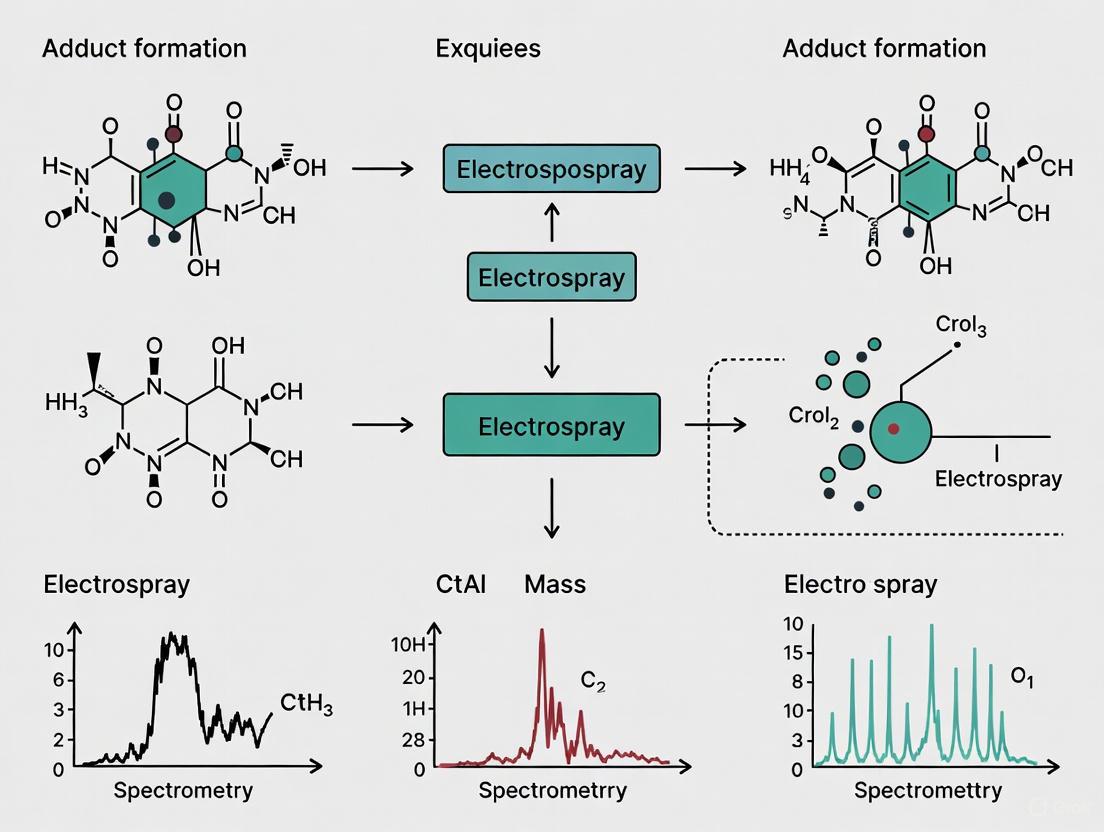

The specific ions observed in an ESI mass spectrum result from several competing equilibria established within the charged droplets. These equilibria involve the analyte and various cationic or anionic species present in the solution. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways leading to the formation of protonated molecules and common adduct ions.

The dominant pathway for a given analyte depends on multiple factors, including the proton affinity of the analyte relative to the solvent, the concentration and binding constants of available cations, and the surface activity of the resulting charged species [2]. The final observed mass spectrum reflects the sum of these competitive processes, with the relative abundance of each ion species providing insights into the underlying equilibria.

Comprehensive Taxonomy of Common Adduct Ions

Positive Ion Mode Adducts

In positive ion mode ESI-MS, analytes typically form adducts with cations. The most prevalent adducts arise from ubiquitous species such as protons, sodium, potassium, and ammonium ions, but many other adduct types are possible depending on the solution composition.

Table 1: Common Adduct Ions in Positive Ion Mode ESI-MS

| Adduct Ion | Nominal Mass Shift | Exact Mass Shift (Da) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

[M+H]+ |

M+1 | M+1.007276 | Most common ion in positive mode |

[M+NH4]+ |

M+18 | M+18.03382 | Common with ammonium additives |

[M+Na]+ |

M+23 | M+22.989218 | From glassware or salts |

[M+CH3OH+H]+ |

M+33 | M+33.033489 | Solvent-mediated adduct |

[M+K]+ |

M+39 | M+38.9632 | From buffers or impurities |

[M+CH3CN+H]+ |

M+42 | M+42.033823 | Solvent-mediated adduct |

[M+iPr+H]+ |

M+61 | M+61.06534 | With isopropanol solvent |

[M+DMSO+H]+ |

M+79 | M+79.02122 | With DMSO solvent |

[M+2Na]2+ |

M/2+23 | M/2+22.989218 | Doubly charged |

[M+H+Na]2+ |

M/2+12 | M/2+11.998247 | Doubly charged |

[M+2H]2+ |

M/2+1 | M/2+1.007276 | Common for peptides/proteins |

Negative Ion Mode Adducts

In negative ion mode, analytes typically form adducts with anions or undergo deprotonation. The specific adducts observed depend on the anions present in the mobile phase or sample.

Table 2: Common Adduct Ions in Negative Ion Mode ESI-MS

| Adduct Ion | Nominal Mass Shift | Exact Mass Shift (Da) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

[M-H]- |

M-1 | M-1.007276 | Most common ion in negative mode |

[M+Cl]- |

M+35 | M+34.969402 | Note M+37 isotope peak with ~1/4 intensity |

[M+CHO2]- |

M+45 | M+44.998201 | Formate adduct |

[M+CH3CO2]- |

M+59 | M+59.013851 | Acetate adduct |

[M+Br]- |

M+79 | M+78.918885 | Note M+81 isotope peak with ~equal intensity |

[M+CF3CO2]- |

M+113 | M+112.985586 | Trifluoroacetate adduct |

Analytical Implications of Adduct Formation in Research and Development

Challenges in Spectral Interpretation and Quantification

The formation of multiple adduct species presents both challenges and opportunities in analytical method development. From an interpretive standpoint, adduct formation complicates mass spectral analysis by producing multiple peaks for a single analyte, potentially leading to misinterpretation of results [1] [3]. This spectral complexity is particularly problematic in the analysis of complex mixtures, such as biological samples or herbal extracts, where peak capacity is already limited [6]. From a quantitative perspective, the distribution of an analyte's signal across multiple ionic forms can significantly reduce the sensitivity for any single species, potentially elevating limits of detection [2]. Furthermore, the reproducibility of adduct formation can be problematic, as minor variations in solvent composition, pH, or additive concentration can shift the equilibrium between different adduct forms, leading to inconsistent results between analyses [3] [2]. This is especially critical in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development, where method robustness is paramount.

Strategic exploitation of Adduct Formation

Despite these challenges, informed researchers can strategically exploit adduct formation to enhance analytical capabilities. For compounds with poor proton affinity or that are difficult to ionize via proton transfer, adduct formation with alternative cations can provide a sensitive detection pathway [2]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse analyte classes, including sugars, steroids, and various explosives [2]. In structural elucidation studies, the controlled formation of specific adducts can produce informative fragmentation patterns that reveal molecular structure. For instance, sodium and ammonium adduct-targeted product ion scans have been used to profile polyoxypregnanes and their glycosides (POPs) in herbal and biological specimens [6]. The diagnostic fragmentation of these adduct ions provided structural information that complemented data from protonated molecules.

Methodological Control of Adduct Formation

Experimental Design for Adduct Manipulation

Controlling adduct formation requires careful consideration of mobile phase composition and additives. The selection of appropriate additives represents one of the most effective strategies for directing adduct formation toward a single dominant species, thereby simplifying spectral interpretation and improving quantitative performance.

Table 3: Mobile Phase Additives for Controlling Adduct Formation

| Additive | Typical Concentration | Effect on Adduct Formation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formic Acid | 0.1% | Promotes [M+H]+ formation |

Common for positive mode; can sometimes enhance [M+Na]+ |

| Acetic Acid | 0.1% | Promotes [M+H]+ formation |

Less acidic alternative to formic acid |

| Ammonium Acetate | 5-10 mM | Promotes [M+NH4]+ or [M+H]+ |

Can suppress sodium adducts; volatile for LC-MS |

| Ammonium Formate | 5-10 mM | Promotes [M+NH4]+ or [M+H]+ |

Alternative to ammonium acetate |

| Methylamine | 1 mM | Promotes [M+CH3NH3]+ adducts |

Can enhance sensitivity for certain compounds |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | 0.1% | Strong [M+H]+ promotion |

Can cause ion suppression in ESI; use with caution |

| Alkylamines (C1-C12) | Variable | Forms [M+RNH3]+ adducts |

Chain length affects sensitivity; C6 often optimal |

Practical Workflow for Adduct Optimization

Developing a robust ESI-MS method requires a systematic approach to adduct optimization. The following diagram outlines a decision workflow for controlling adduct formation through mobile phase selection.

This workflow emphasizes an iterative approach to method development, where the initial screening with neutral mobile phases (e.g., water/acetonitrile without additives) provides a baseline understanding of the inherent adduction tendencies of the analyte [2]. Subsequent refinement through additive selection and concentration optimization allows researchers to steer the equilibrium toward the desired ionic form. The choice of additive should align with the analytical objectives—acidic modifiers generally promote [M+H]+ formation, ammonium salts can facilitate [M+NH4]+ adducts or [M+H]+, and alkylamines can create alternative adduction pathways for challenging analytes [2].

Case Studies in Pharmaceutical and Bioanalytical Applications

Adduct Formation in Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator (SARM) Analysis

Recent research on Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) containing nitrile functional groups revealed extensive adduct formation in ESI-MS, significantly impacting detection sensitivity and potentially leading to misinterpretation of analytical results [3]. This study systematically investigated mobile phase additives as a means to control adduct formation, identifying for the first time the formation of chloride adducts in SARM analysis [3]. Through a series of method development experiments, researchers evaluated various mobile phase combinations to achieve optimal HPLC-MS conditions, comparing adduct formation across different grades of water used for mobile phase preparation. The findings demonstrated that appropriate additive selection could dramatically reduce spectral complexity and improve quantitative reliability, essential for investigating the illicit use of these compounds in horse racing [3].

Covalent Protein-Drug Adduct Detection in Targeted Covalent Inhibitor Development

In pharmaceutical development, particularly for Targeted Covalent Inhibitors (TCIs), the direct detection of covalent protein-drug adducts provides critical evidence of the intended mechanism of action [7]. Mass spectrometric analysis has become an indispensable tool for confirming covalent adduct formation between electrophilic warheads in drug candidates and nucleophilic amino acid residues in protein targets [7]. The shift from considering covalent inhibition as a liability to actively designing TCIs has necessitated robust analytical methods for verifying covalent adduct formation. These methods must distinguish covalent adducts from noncovalent complexes, often requiring analysis under denaturing conditions that disrupt noncovalent interactions while preserving covalent bonds [7]. For reversible covalent inhibitors—an emerging class with compounds like nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) and rilzabrutinib—detection presents additional challenges as standard sample preparation conditions may induce dissociation of the reversible covalent ligand [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Adduct Research

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Adduct Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Adduct Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate | Volatile buffer that promotes [M+NH4]+ adducts or [M+H]+ |

LC-MS mobile phase additive to suppress sodium adducts |

| Alkylamine Additives | Forms alternative [M+RNH3]+ adducts for difficult-to-ionize compounds |

Enhancing sensitivity for analytes with low proton affinity |

| Acid Modifiers (Formic, Acetic) | Promotes [M+H]+ formation through solution acidification |

Positive ion mode ESI for basic compounds |

| High-Purity Solvents/Water | Minimizes unintentional adduct formation from ionic impurities | Essential for reproducible adduct formation across experiments |

| Metal Salts (Na, K) | Intentional formation of specific metal adducts for structural studies | Method development for adduct-targeted fragmentation |

| Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) Gases | Fragmentation of adduct ions for structural characterization | Tandem MS experiments for structural elucidation |

Adduct ions represent a fundamental aspect of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry that extends far beyond the conventional protonated molecule. Within electrospray research, understanding the mechanisms governing adduct formation—the competitive equilibria in charged droplets, the influence of mobile phase composition, and the structural factors affecting adduct stability—provides researchers with powerful levers for analytical method control. Rather than viewing adduct formation as an inconvenient artifact, scientists can strategically exploit these phenomena to address challenging analytical problems, from detecting poorly ionizable compounds to elucidating molecular structures through diagnostic fragmentation patterns. As ESI-MS continues to evolve as a cornerstone technique in pharmaceutical and bioanalytical research, mastery of adduct ion behavior will remain essential for developing robust, sensitive, and informative analytical methods. The experimental frameworks and methodological principles outlined in this technical guide provide a foundation for advancing this understanding and applying it to cutting-edge research in drug development and beyond.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a cornerstone soft ionization technique in modern mass spectrometry, renowned for its ability to produce gas-phase ions of thermally labile and large supramolecules without significant fragmentation [4]. This preservation of molecular integrity is crucial for analyzing biological macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, which would be destroyed by more traditional, harsher ionization methods. The "soft" nature of ESI results from the gentle process of ion formation, where a very little amount of residual energy is retained by the analyte, allowing even very weak noncovalent interactions to be preserved in the gas phase [4].

A defining feature of ESI, especially for large biomolecules, is its propensity to generate multiply charged ions [4]. Instead of producing a single ion by removing one electron or proton, ESI can add multiple protons to a single large molecule. This multiple charging has a profound effect: it reduces the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the resulting ions, thereby bringing them within the detectable mass range of common mass analyzers. This capability was groundbreaking, transforming mass spectrometry from a tool for small molecules into an essential technology for proteomics and the study of other biological macromolecules [4]. Within this specific ESI environment—characterized by minimal fragmentation and the presence of multiple charges—the phenomenon of adduct formation readily occurs. Adducts are species formed by the non-covalent attachment of ions or molecules from the solvent or mobile phase (e.g., sodium, potassium, ammonium, or chloride) to the analyte ion. While sometimes problematic for interpretation, the study of these adducts also provides a window into the ionization mechanism and the chemical properties of the analyte.

The ESI Process and the Mechanism of Multiple Charging

The Three-Stage Mechanism of ESI

The formation of ions in ESI is not an instantaneous event but a multi-stage process that transforms ions from solution into gas-phase ions suitable for mass analysis [8]. This process can be broken down into three critical stages, as illustrated in the diagram below.

- Droplet Formation: A dilute analyte solution is injected through a metal capillary (needle) at a low flow rate. A high voltage (typically 2-6 kV) applied to the capillary tip, relative to a nearby counter-electrode, disperses the liquid into a fine aerosol of charged droplets [4] [8]. A coaxial flow of dry nitrogen gas (nebulizing gas) is often used to assist in directing the spray and initiating solvent evaporation.

- Droplet Desolvation: As the charged droplets travel towards the mass spectrometer inlet, the solvent continuously evaporates, assisted by a flow of heated dry gas (drying gas) [4]. This evaporation reduces the droplet's size while its charge remains constant, leading to a dramatic increase in the droplet's surface charge density.

- Gas Phase Ion Formation: When the electrostatic repulsion within the droplet (Rayleigh limit) overcomes its surface tension, it undergoes Coulombic fission, splitting into smaller, offspring droplets [8]. This cycle of evaporation and fission repeats until the droplets are exceedingly small. Ultimately, the mechanism by which the final bare ion is released into the gas phase is theorized to be through one of two models: the Charge Residue Model (CRM), which posits that repeated fission events eventually leave a single, multiply charged analyte ion where the droplet once was, or the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM), which suggests that individual ions are desorbed or "evaporated" directly from the highly charged surface of the nanodroplet [4].

The Origin and Impact of Multiple Charging

The multiple charging observed in ESI, particularly for large molecules like proteins, is a direct consequence of the ionization mechanism. In positive ion mode, protons from the acidic solution can readily add to basic sites on the analyte molecule (e.g., amino groups in lysine, arginine, and the N-terminus of peptides). Because a single large biomolecule can have many such sites, it can accommodate multiple protons, becoming a multiply charged cation, [M+nH]ⁿ⁺ [4]. The distribution of these charge states in the mass spectrum is not random; it is influenced by the molecule's three-dimensional structure, with more unfolded, denatured states typically yielding higher charge states due to greater exposure of basic sites.

The primary benefit of multiple charging is the reduction of the m/z ratio. For example, a 50,000 Da protein acquiring 50 protons has an m/z of approximately 1,000, well within the range of most commercial mass analyzers. This allows for the accurate mass determination of very large molecules using instruments with limited m/z ranges [4].

Adduct Formation in the ESI Environment

The Nature and Challenge of Adducts

In the context of ESI-MS, an adduct is an ion formed by the non-covalent association of the analyte ion (e.g., [M+H]⁺) with another ion or neutral molecule present in the spray solution, such as a mobile phase additive or a buffer component. Common examples include sodium ([M+Na]⁺), potassium ([M+K]⁺), ammonium ([M+NH₄]⁺), and formate ([M+HCOO]⁻) adducts. The formation of these adducts is a widespread phenomenon that can complicate mass spectral interpretation by dispersing the signal for a single analyte across multiple m/z values, thereby adversely impacting sensitivity and potentially causing misinterpretation of results [3].

The stability and prevalence of an adduct are not arbitrary; they are governed by specific physicochemical principles. A key model for understanding adduct stability, particularly for multiply charged ions, is the proton-bound mixed dimer model. This model suggests that an adduct, such as [M – H + Anion]⁻, can be conceptualized as [M – H]⁻···H⁺···[Anion]⁻, where the proton is shared between the deprotonated analyte and the attaching anion. The maximum stability for such a structure is achieved when the two anions have approximately equivalent gas-phase basicities (GB) [9]. If their GBs are too dissimilar, the proton will preferentially reside with the more basic species, leading to the dissociation of the adduct.

A Model for Multiply Charged Adduct Formation

Research has shown that the formation of multiply charged adducts in negative ion ESI follows a predictable pattern based on the relationship between the charge state of the peptide and the gas-phase basicity of the attaching anion. A seminal study using [Glu] Fibrinopeptide B demonstrated this relationship systematically [9].

The peptide was introduced via ESI with various ammonium salts (NH₄X, where X = HSO₄⁻, I⁻, CF₃COO⁻, NO₃⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻, etc.). The observed adduct formation revealed a clear trend:

- Lower GB anions (e.g., HSO₄⁻, GB = 1265.0 kJ/mol) formed stable adducts predominantly at lower charge states (-1 and -2).

- Medium GB anions (e.g., NO₃⁻ and Br⁻, GB ~1330 kJ/mol) formed adducts only at the -2 charge state.

- Higher GB anions (e.g., Cl⁻, GB = 1373.6 kJ/mol) could form adducts at higher charge states, including the -3 charge state.

- Anions with very high GBs (e.g., CH₃COO⁻) formed no observable adducts at any charge state [9].

This behavior can be explained by considering the "apparent gas-phase basicity" (GBapp) of the proton-bearing sites on the peptide at different charge states. As the charge state of the peptide increases (becomes more negative), the Coulombic repulsion between sites makes it more difficult to remove a proton, effectively lowering the GBapp of the remaining sites. Therefore, a higher charge state peptide can only stabilize an adduct with a higher GB anion that can effectively match the lowered GBapp of its sites [9]. The inverse is true for lower charge states. This charge-state-dependent matching of GBapp is summarized in the diagram below.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Anion Adduct Formation with [Glu] Fibrinopeptide B [9]

| Anion | Gas-Phase Basicity (GB, kJ/mol) | Observed Adduct Charge States | Relative Adduct Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSO₄⁻ | 1265.0 ± 10.0 | -1, -2 | Forms adducts at lower charge states; can also form adducts with neutral H₂SO₄. |

| I⁻ | 1293.7 ± 0.84 | -1, -2 | Singly charged adduct decreases relative to HSO₄⁻. |

| NO₃⁻ | 1329.7 ± 0.84 | -2 | Adducts form only at the -2 charge state. |

| Br⁻ | 1331.4 ± 4.6 | -2 | Adducts form only at the -2 charge state. |

| Cl⁻ | 1373.6 ± 8.4 | -2, -3 | Can form adducts at the -3 charge state, unlike lower GB anions. |

| CH₃COO⁻ | ~1420 (est.) | None | Too high GB; no observable adducts formed. |

This model has been corroborated by other studies. For instance, research on Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) containing nitrile functional groups reported significant and complicated adduct formation, including the first evidence of chloride adduct formation in ESI-MS. This study further highlighted that the choice of mobile phase additives and even the grade of water used could drastically influence the type and extent of adducts observed, underscoring the need for careful control of the ESI environment [3].

Experimental Protocols for Studying ESI Adducts

To provide a concrete example of how adduct formation is investigated, the following section details a key experimental methodology from the literature.

Detailed Protocol: Investigating Peptide-Anion Adducts

This protocol is adapted from a fundamental study on multiply charged adduct formation between peptides and anions in negative ion ESI-MS [9].

Objective: To elucidate the mechanism of multiple adduct formation and characterize the stability of peptide-anion complexes based on anion gas-phase basicity and peptide charge state.

Materials and Reagents:

- Model Peptides: [Glu] Fibrinopeptide B (sequence: EGVNDNEEGFFSAR) and ACTH 22–39 (sequence: VYPNGAEDESAEAFPLEF). These hydrophilic peptides were chosen for their known sequences and mix of acidic/basic sites.

- Anion Sources: A series of ammonium salts (NH₄X), including X = HSO₄⁻, I⁻, CF₃COO⁻, NO₃⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻.

- Solvent: Pure methanol solution.

- Instrumentation: A Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer, chosen for its high mass resolution and accuracy, which is essential for confidently identifying the composition of multiply charged adducts.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of the model peptide (e.g., 3.2 μM [Glu] Fibrinopeptide B) in pure methanol.

- Prepare stock solutions of the ammonium salts (e.g., 64 μM) in methanol.

- Mix the peptide solution with the ammonium salt solutions to achieve the desired final concentrations for analysis. A control sample with no added salt is essential.

ESI-MS Analysis Conditions:

- Ion Mode: Negative ion ESI.

- Capillary Exit/Skimmer Voltages: Set to soft conditions (e.g., -35 V and -1.7 V, respectively) to promote adduct formation and minimize collisional-induced dissociation in the source region.

- Other Parameters: Follow standard instrument tuning procedures for optimal signal for the peptides of interest.

Data Interpretation:

- Identify the charge state distribution of the "bare" peptide (without added salts) from the control sample.

- For each ammonium salt addition, identify all new peaks corresponding to peptide-anion adducts (e.g., [Peptide + nX]ⁿ⁻) and note their charge states.

- Correlate the observed adduct charge states with the known gas-phase basicity of the anion (see Table 1).

- The key finding to validate is whether higher GB anions form stable adducts predominantly at higher negative charge states of the peptide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for ESI Adduct Research

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ESI Adduct Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Salts (NH₄X) | Source of anions (X⁻) for adduction studies. Allows systematic variation of anion identity. | NH₄Cl, NH₄Br, NH₄H₂PO₄, NH₄HSO₄. Ammonium is volatile and avoids persistent salt contamination [9]. |

| Model Peptides | Well-characterized analytes with known sequences and protonation/deprotonation sites. | [Glu] Fibrinopeptide B, ACTH fragments. Their defined structure allows mechanistic insights [9]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Mobile phase for ESI; impurities can cause unintended adducts. | HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, water. High-grade water is critical, as chloride impurities are common [3]. |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Modify the ESI environment to control or suppress adduct formation. | Acids, bases, volatile buffers (ammonium formate/acetate). Concentration and type are critical variables [3]. |

| FT-ICR or High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Analyzer for accurately identifying the composition of multiply charged adducts. | Provides the high mass resolution needed to distinguish between closely related adduct species [9]. |

Electrospray Ionization creates a unique environment defined by its soft ionization character and the production of multiply charged ions. Within this environment, adduct formation is not a random artifact but a chemically governed process. The stability of these adducts, particularly for multiply charged analytes, is determined by a matching of the apparent gas-phase basicity of the analyte's charge sites with the gas-phase basicity of the attaching ion. This understanding, derived from systematic studies, provides researchers with a predictive framework. By carefully controlling experimental conditions—such as the choice of mobile phase additives, solvent purity, and instrument parameters—scientists can mitigate the confounding effects of adducts or strategically exploit them to glean information about analyte properties and ionization mechanisms. As ESI-MS continues to be a pivotal tool in drug development, proteomics, and metabolomics, a deep understanding of adduct formation remains essential for accurate data interpretation and method development.

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the formation of adduct ions is a fundamental ionization mechanism rather than an anomaly. Adduct ions are defined as ions formed by the interaction of a precursor ion with one or more atoms or molecules to form an ion containing all the constituent atoms of the precursor ion as well as the additional atoms from the associated atoms or molecules [1]. Within the context of electrospray research, understanding adduct formation is crucial for accurate molecular identification, sensitivity optimization, and methodological development. The controlled formation of adducts can significantly enhance detection capabilities for compounds that are otherwise challenging to analyze, such as those lacking easily ionizable functional groups [2]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive catalog of the most prevalent adducts observed in ESI-MS analyses, along with experimental frameworks for their predictable generation and application in pharmaceutical and biochemical research.

Core Principles of Adduct Formation in ESI

Electrospray ionization operates through the generation of charged droplets from a liquid sample, followed by droplet desolvation and gas-phase ion release. The specific ions observed in the mass spectrum result from a series of equilibria occurring within the ESI droplets and at their surfaces [2]. The process can be summarized by several key equilibria, combining both liquid-phase and gas-phase processes:

- M ⇄ [M + H]⁺ (Protonation)

- M ⇄ [M + Na]⁺ (Sodium Adduct Formation)

- M ⇄ [M + NH₄]⁺ (Ammonium Adduct Formation)

These equilibria coexist, and the dominant species observed depends on factors including the chemical properties of the analyte, the composition of the mobile phase, and the presence of various cationic species in the solution [2]. The surface activity of the resulting ion and its hydrophobicity also play significant roles in determining which adducts are preferentially observed in the mass spectrum [2]. While adduct formation is a powerful tool for ionization, the formation of multiple adducts for a single analyte can split the ion signal, potentially reducing sensitivity and complicating spectral interpretation [2].

Catalog of Common Adducts

The following sections provide a detailed catalog of the most frequently encountered adducts in ESI-MS, organized by ionization mode. The tables include both nominal mass shifts and exact mass additions, the latter being critical for high-resolution mass spectrometry applications.

Common Adducts in Positive Ion Mode

Table 1: Singly Charged Positive Ion Mode Adducts

| Adduct Ion | Nominal Mass Change | Exact Mass Change (Da) |

|---|---|---|

| [M + H]⁺ | M + 1 | M + 1.007276 |

| [M + NH₄]⁺ | M + 18 | M + 18.033823 |

| [M + Na]⁺ | M + 23 | M + 22.989218 |

| [M + CH₃OH + H]⁺ | M + 33 | M + 33.033489 |

| [M + K]⁺ | M + 39 | M + 38.963158 |

| [M + ACN + H]⁺ | M + 42 | M + 42.033823 |

| [M + 2Na - H]⁺ | M + 45 | M + 44.971160 |

Table 2: Multiply Charged and Dimer Adducts in Positive Mode

| Adduct Ion | Formula for m/z Calculation | Charge |

|---|---|---|

| [M + 2H]²⁺ | M/2 + 1.007276 | 2+ |

| [M + H + Na]²⁺ | M/2 + 11.998247 | 2+ |

| [M + 2Na]²⁺ | M/2 + 22.989218 | 2+ |

| [2M + H]⁺ | 2M + 1.007276 | 1+ |

| [2M + Na]⁺ | 2M + 22.989218 | 1+ |

| [2M + K]⁺ | 2M + 38.963158 | 1+ |

Common Adducts in Negative Ion Mode

Table 3: Common Negative Ion Mode Adducts

| Adduct Ion | Nominal Mass Change | Exact Mass Change (Da) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| [M - H]⁻ | M - 1 | M - 1.007276 | |

| [M + Cl]⁻ | M + 35 | M + 34.969402 | Look for M+37 isotope peak at ~1/4 intensity |

| [M + CHO₂]⁻ (Formate) | M + 45 | M + 44.998201 | |

| [M + CH₃CO₂]⁻ (Acetate) | M + 59 | M + 59.013851 | |

| [M + Br]⁻ | M + 79 | M + 78.918885 | Look for M+81 isotope peak at similar intensity |

Statistical analysis of mass spectral libraries reveals that the hydrogen adduct is the most predominant across databases. In positive mode, [M + H]⁺ accounts for approximately 74.0% of observed adducts, while in negative mode, [M - H]⁻ accounts for about 80.7% [10].

Experimental Protocols for Controlling Adduct Formation

The ability to manipulate adduct formation is a powerful tool for optimizing ESI-MS analyses. The following experimental parameters are key levers for controlling the observed ion species.

The Role of Mobile Phase Additives

Mobile phase additives are a highly effective measure for manipulating adduct formation efficiencies. An appropriate choice of additive can increase sensitivity by up to three orders of magnitude [2]. The additives influence the equilibria in the ESI droplets by providing specific cations or anions, or by modifying the solution pH.

Table 4: Common Mobile Phase Additives and Their Effects

| Additive | Typical Concentration | Primary Effect on Adduct Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Formic Acid | 0.1% | Promotes [M+H]+ formation; common for positive mode. |

| Acetic Acid | 0.1% | Similar to formic acid, slightly less acidic. |

| Ammonium Acetate | 1-10 mM | Can promote [M+NH4]+ in positive mode; [M+CH3CO2]- in negative mode. |

| Ammonia | 0.1% | Creates basic conditions, can suppress positive ionization and promote [M-H]-. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | 0.1% | Strong ion-pairing agent; can suppress ionization but useful for separation. |

| Lithium Chloride | Post-column infusion | Promotes formation of lithium adducts [M+Li]+ for specific applications like lipidomics [11]. |

| Alkylamines (e.g., Methylamine) | 1 mM | Can suppress multiple adduct formation, promoting a single [M+RNH3]+ species [2]. |

Protocol: Systematic Optimization of Mobile Phase for Adduct Control

- Initial Scouting: Begin with a standard mobile phase of water/acetonitrile without additives to observe the native adduct formation pattern of your analyte.

- Additive Selection for [M+H]⁺ Enhancement: To favor the formation of [M+H]⁺, add a volatile acid such as 0.1% formic acid or acetic acid to the aqueous phase. This increases the proton availability in the droplets.

- Additive Selection for Specific Cationic Adducts: To promote adducts like [M+Na]⁺ or [M+NH₄]⁺, consider additives that provide a source of the desired cation. For example, ammonium acetate can be a source for NH₄⁺. Note that sodium is often ubiquitous from glassware or solvent impurities, but its formation can be significantly influenced by mobile phase properties [2].

- Evaluation and Repeatability Assessment: Analyze the sample with the modified mobile phase. Monitor the signal intensity of the desired adduct and the overall signal-to-noise ratio. The use of additives has been shown to improve the repeatability of adduct formation efficiencies compared to additive-free mobile phases [2].

- Troubleshooting Multiple Adducts: If the formation of multiple adducts (e.g., simultaneous [M+H]⁺, [M+Na]⁺, and [M+K]⁺) splits the signal and reduces sensitivity, consider testing alkylamine additives like methylamine. These can form a single dominant [M+RNH₃]⁺ adduct, concentrating the signal into one species [2].

Addressing Unwanted Adducts and Contamination

Adduct formation is not always desirable and can stem from contamination.

- Source Investigation: Common sources of metal cations like Na⁺ and K⁺ include solvent impurities, leachates from glassware, and mobile phase additives [1] [2]. Contaminants from plasticizers (e.g., n-butyl benzenesulfonamide) or gases from nitrogen generators can also create persistent background ions and unexpected adducts [12].

- Mitigation Strategies: Using high-purity solvents and additives, periodic cleaning of the fluidic path, and installing appropriate filters on gas lines can help minimize contamination-related adducts.

Visualization of Adduct Formation and Control Pathways

The following diagram summarizes the key factors influencing adduct formation and the decision-making process for experimental control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful management of adduct formation relies on the use of specific reagents and computational tools.

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Tools for Adduct Research

| Tool or Reagent | Function/Description | Application in Adduct Research |

|---|---|---|

| Volatile Acids (Formic, Acetic) | Mobile phase additives to lower pH and increase proton concentration. | Promotes the formation of [M+H]+ in positive ion mode. |

| Ammonium Salts (e.g., Acetate, Formate) | Volatile salts used as mobile phase additives. | Source of ammonium ions for [M+NH4]+ formation; can also provide anions for negative mode. |

| Alkylamines (e.g., Methylamine) | Basic mobile phase additives. | Can consolidate signal into a single [M+RNH3]+ species, improving sensitivity and repeatability. |

| Lithium Salts (e.g., LiCl) | Post-column infusion reagents. | Promotes the formation of lithium adducts [M+Li]+, useful for analyzing neutral lipids like triglycerides [11]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Water and organic solvents (ACN, MeOH) with minimal ionic contamination. | Reduces the formation of unpredictable metal adducts (e.g., [M+Na]+, [M+K]+) from impurities. |

| Mass Spectrometry Adduct Calculator (MSAC) | A Python-based tool for calculating expected m/z for a wide range of adducts. | Automates the prediction of potential adduct masses for compound identification, supporting custom adduct lists [10]. |

| ESI Adduct Calculator (Fiehn Lab) | An Excel-based tool for calculating adduct masses. | Provides a user-friendly interface for predicting common and less common adduct m/z values [13]. |

The predictable formation and interpretation of common adducts such as [M+H]⁺, [M+Na]⁺, [M+NH₄]⁺, and [M+K]⁺, along with their negative mode counterparts, are foundational skills in electrospray ionization research. By leveraging the detailed quantitative data, experimental protocols, and tools outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can transform adduct formation from an unpredictable variable into a controlled parameter. This control enables enhanced detection sensitivity, improved compound identification confidence, and more robust analytical methods. Mastery of adduct behavior is not merely about spectral interpretation; it is about actively designing mass spectrometric analyses to yield the most chemically informative and analytically precise results possible.

This technical guide explores the fundamental processes within electrospray ionization (ESI) that fundamentally influence the formation and detection of analyte adducts. The journey of a charged droplet—from its generation at the capillary tip to the release of gas-phase ions—is governed by the intertwined dynamics of solvent evaporation and Coulombic fission. These processes not only determine ionization efficiency but also directly promote chemical interactions that lead to adduction, a critical phenomenon in drug development and proteomic research. This paper synthesizes current experimental evidence and theoretical models to provide researchers with a mechanistic understanding of adduct formation, supported by quantitative data, detailed protocols, and analytical workflows for its study.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that has revolutionized the analysis of macromolecules, particularly in the fields of proteomics and pharmaceutical science [4]. Its operation hinges on the production of a fine aerosol of charged droplets from an analyte solution, followed by sequential solvent evaporation and droplet disintegration until gas-phase ions are liberated. A pivotal, yet often complicating, feature of ESI is the propensity of analytes to form adducts—complexes where the analyte of interest is non-covalently or covalently bound to solvent molecules, salts, or other buffer components, or undergoes specific chemical modifications. These adducts manifest in the mass spectrum as additional peaks, which can be misinterpreted without a deep understanding of their origin.

Within the context of drug development, adduct formation takes on a more serious tone. Certain drugs can form reactive metabolites that covalently bind to proteins, a process linked to time-dependent enzyme inhibition and adverse drug reactions [14] [15]. Understanding the droplet lifecycle is therefore not merely an analytical exercise but a necessity for accurately interpreting mass spectrometric data, quantifying drug-protein interactions, and mitigating the risk of drug-induced toxicities.

The Core Mechanisms of the Droplet Lifecycle

The pathway from a liquid sample to a gas-phase ion is a cyclic process of evaporation and fission, culminating in ion release. The following diagram illustrates this core lifecycle.

Stage 1: Droplet Formation and Initial Evaporation

The ESI process begins when a high voltage (typically 2-6 kV) is applied to a metal capillary through which a dilute analyte solution is pumped. This strong electric field disperses the liquid into a fine aerosol of highly charged droplets [4]. These initial droplets are often larger and longer-lived than traditionally assumed, with documented sizes ranging from 2 μm to over 100 μm depending on the solvent, flow rate, and spray mode [16]. As these droplets travel towards the mass spectrometer inlet, the neutral solvent (e.g., methanol, water, acetonitrile) begins to evaporate, a process often assisted by a coaxial flow of heated drying gas [17] [4].

Stage 2: Coulombic Fission and the Rayleigh Limit

Solvent evaporation causes the droplet to shrink while its charge remains relatively constant. This leads to an increase in charge density on the droplet surface. Lord Rayleigh theoretically determined the maximum charge a droplet can sustain—the Rayleigh limit—where the electrostatic repulsion of the like charges equals the surface tension holding the droplet together [17]. Upon reaching this limit, the droplet becomes unstable and undergoes Coulomb fission [18] [17]. This fission event is not an explosion but a controlled disintegration where the parent droplet ejects smaller, progeny droplets.

Table 1: Characteristics of Coulombic Fission Events in Different Systems

| Droplet Type | Observed Fission Characteristics | Mass Loss per Fission | Charge Loss per Fission | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Solvents (e.g., Water) | Successive fissions at similar normalized diameters; repeatable over droplet lifetime. | ~1.0 - 2.3% | ~10 - 18% | [18] [17] |

| Methanol | Average of 13.2 (±4.4) progeny droplets detected per fission event. | ~81% of net charge released via progeny droplets. | [19] | |

| Nanofluids (Water/Alumina) | Damped deformations; larger mass expelled; can split in half in extreme cases. | Larger than pure water | N/A | [18] |

Stage 3: Pathways to Gas-Phase Ions and Adducts

After multiple cycles of evaporation and fission, two primary models explain the final release of gas-phase ions, which directly informs adduct observation:

- Charge Residue Model (CRM): Proposed by Dole, this model suggests that the evaporating droplet undergoes fission cycles until a progeny droplet containing a single analyte molecule is formed. The final solvent molecules evaporate, leaving the analyte with the droplet's residual charge. This mechanism is generally accepted for large, folded proteins and can lead to the observation of multiple-charged ions and adducts with any non-volatile species present in the final droplet [17] [4].

- Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): This model posits that when the droplet radius becomes very small (e.g., ~10 nm), the electric field at its surface is strong enough to field-desorb solvated ions directly into the gas phase. This mechanism is thought to dominate for smaller ions and can also promote adduction if the desorbed ion is a complex rather than a bare analyte [17].

The journey of these droplets is remarkably robust; evidence shows that large, charged droplets can survive to penetrate deep into the vacuum stages of mass spectrometers, where their sudden disintegration can contribute to spectral noise and contamination [16].

Linking the Droplet Lifecycle to Adduct Formation

The conditions within an evaporating charged droplet create a unique microenvironment that actively promotes adduct formation through several mechanisms.

Concentration and Context Factors

As solvent evaporates, all non-volatile species in the droplet—including the analyte, buffers, salts, and drug metabolites—become increasingly concentrated. This elevated concentration dramatically increases the probability of interactions. For non-covalent adducts, this can mean the stabilization of quasi-molecular ions like [M+H]+ or [M+Na]+ [17]. For covalent chemistry, it provides the conditions necessary for reactive, short-lived species to encounter and modify proteins. This "context factor," driven by the physical chemistry of the droplet, is a critical element in drug hypersensitivity reactions, where a drug's metabolite forms a covalent adduct with a protein, haptenating it and triggering an immune response [15].

The Role of Coulombic Fissions in Partitioning

Coulombic fission events are not merely a means of droplet size reduction; they are active partitioning steps. During fission, the distribution of chemical species between the parent and progeny droplets is not necessarily even. A study on raloxifene, a drug that forms a reactive diquinone methide metabolite, highlights this. Researchers found that specific peptides in enzymes like CYP3A4 were modified on nucleophilic amino acids like cysteine. The use of stable isotope-labeled raloxifene (raloxifene-d4) allowed for precise quantification of these adducts, revealing significant interindividual variability in their formation in human liver microsomes [14]. This variability can be influenced by the fission process, which selectively concentrates certain ions in progeny droplets, thereby influencing which analytes are ultimately observed and the extent of their modification.

The following diagram outlines the pathway from drug incubation to the detection of a protein adduct, a key process in understanding drug-induced toxicities.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Droplet Processes and Adduction

To study the phenomena described, researchers employ a range of techniques from direct droplet observation to proteomic analysis of adducts.

Protocol: High-Speed Imagery for Coulombic Fission Dynamics

This method directly characterizes the fission events of evaporating droplets [18].

- Objective: To measure droplet diameter and deformation dynamics during Coulombic fission for pure liquids and nanofluids.

- Materials:

- Electrodynamic balance or similar levitation apparatus.

- High-speed camera (capable of >10,000 fps).

- Syringe pump for controlled droplet generation.

- Laser light source for illumination and scatter measurement.

- Test solutions: pure water, methanol, or nanofluids (e.g., water/alumina).

- Procedure:

- A single droplet is levitated within the electrodynamic balance.

- The droplet is allowed to evaporate freely while being illuminated by a laser.

- The high-speed camera records the droplet's scatter signal and physical shape.

- The recording continues until the droplet reaches its Rayleigh limit and undergoes Coulomb fission.

- The video is analyzed to determine the normalized diameter at fission, the number of progeny droplets, and the deformation characteristics (e.g., axis ratio oscillations).

- Key Measurements: Time-resolved droplet size, fission diameter, progeny droplet count, and deformation damping (for nanofluids).

Protocol: Quantifying Drug-Protein Adducts via DIA Proteomics

This protocol details the methodology for identifying and quantifying covalent drug-protein adducts, as demonstrated in studies on raloxifene [14].

- Objective: To quantify the amount of covalent adducts formed between reactive drug metabolites and specific amino acid residues on target proteins.

- Materials:

- Enzyme source: Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) or recombinant P450 supersomes.

- Model drug: e.g., Raloxifene or stable isotope-labeled variant (raloxifene-d4).

- LC-MS/MS system with ESI source.

- Proteomic software: Skyline for data analysis.

- Trypsin for protein digestion.

- Procedure:

- Incubation: HLMs or supersomes are incubated with the drug (and its isotope label) to allow for metabolic activation and adduct formation.

- Digestion: The protein mixture is denatured and digested with trypsin into peptides.

- LC-ESI-MS Analysis: The peptide mixture is separated by liquid chromatography and introduced into the mass spectrometer via an ESI source.

- Data Acquisition: Mass spectra are acquired using Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) to fragment all ions within selected m/z windows.

- Data Analysis:

- Skyline is used to quantify modified and unmodified peptides.

- A clear retention time shift is used to identify adducted peptides.

- "Non-modifiable" peptides from the target protein are used to normalize and quantify the total protein amount across samples.

- The relative quantity of adducted peptides is compared to enzyme activity data to correlate adduct formation with functional inactivation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ESI Droplet and Adduct Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Electrodynamic Balance | Levitates a single droplet for isolated observation. | Studying Coulomb fission dynamics of isolated methanol droplets [19]. |

| High-Speed Camera | Captures rapid, time-resolved images of droplet deformation and fission. | Measuring progeny droplet production and deformation damping in nanofluids [18]. |

| Nanoelectrospray Emitter | A fine capillary tip for producing very small initial droplets at low flow rates. | Improving ionization efficiency and reducing initial droplet size in ESI-MS [17]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Drug | Serves as an internal standard for precise quantification. | Differentiating and quantifying raloxifene vs. raloxifene-d4 protein adducts [14]. |

| Data Analysis Software (Skyline) | Open-source software for quantitative proteomic data analysis. | Quantifying drug-adducted peptides from DIA LC-MS/MS runs [14]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) | A complex enzyme source containing human drug-metabolizing enzymes. | Studying metabolic activation of drugs and subsequent protein adduction in a physiologically relevant system [14]. |

The lifecycle of a charged droplet in ESI—from formation through evaporation to Coulombic fission—is far from a simple desolvation process. It is a dynamic sequence of events that creates a unique reaction vessel where concentration, charge, and physical instability converge to promote the formation of both non-covalent and covalent adducts. For researchers in drug development, a mechanistic understanding of this lifecycle is paramount. It provides the framework for explaining why adducts form, predicting their impact on analytical results, and ultimately, for designing better drugs and analytical methods to minimize undesirable reactions. As ESI continues to be a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, appreciating the intricate journey of the droplet remains essential for accurate data interpretation and innovation in biomedical research.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) has established itself as a cornerstone technique in modern mass spectrometry, particularly for the analysis of large, non-volatile, and thermally labile molecules. A fundamental aspect of the ESI process is the formation of adduct ions, which are defined as ions formed by the interaction of a precursor ion (the analyte) with one or more atoms or molecules, containing all the constituent atoms of the original analyte plus the adducted species [1]. In the context of ESI, this phenomenon is not merely a side effect but is often the very mechanism by gas-phase ions are produced from solution. The formation and behavior of these adducts can be strategically categorized into two distinct classes: intended adducts, which are deliberately promoted through method development to enhance ionization efficiency, spectral quality, and quantitative accuracy; and unintended adducts, which arise from ubiquitous contaminants in solvents, samples, and laboratoryware, often leading to spectral complexity and analytical inaccuracies. This guide delves into the core principles, strategies, and practical methodologies for mastering adduct formation, framing it within the broader thesis that a deep understanding of this process is not optional but essential for robust electrospray research and development.

The following diagram outlines the core strategic decision-making process for managing adduct formation, helping researchers navigate between intentional and unintentional adduct scenarios.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Types of Adduct Ions

The formation of adduct ions in ESI is primarily governed by the interactions between the analyte and various species present in the electrospray droplet. The charged-residue mechanism (CRM) is particularly relevant for larger molecules and complexes, where the evaporation of solvent from a charged droplet culminates in a gas-phase ion that incorporates adducted species from the original solution [20]. The nature of the adduct is heavily influenced by the ionization mode.

Table 1: Common Adduct Ions in Electrospray Mass Spectrometry

| Ion Mode | Adduct Ion | Nominal Mass Change | Exact Mass Change (Da) | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | [M+H]⁺ | M + 1 | M + 1.007276 | Default for basic analytes |

| [M+NH₄]⁺ | M + 18 | M + 18.03382 | Alternative for non-basic polar analytes | |

| [M+Na]⁺ | M + 23 | M + 22.989218 | Common unintended adduct; also intentional | |

| [M+K]⁺ | M + 39 | M + 38.9632 | Common unintended adduct; also intentional | |

| [M+Li]⁺ | M + 7 | M + 6.941 | Intentional for lipids in normal-phase LC | |

| Negative | [M-H]⁻ | M - 1 | M - 1.007276 | Default for acidic analytes |

| [M+Cl]⁻ | M + 35 | M + 34.969402 | Intentional or from buffer | |

| [M+CHO₂]⁻ | M + 45 | M + 44.998201 | Formate adduct from buffer | |

| [M+CH₃CO₂]⁻ | M + 59 | M + 59.013851 | Acetate adduct from buffer | |

| [M+Br]⁻ | M + 79 | M + 78.918885 | Intentional additive |

In positive ion mode, the most common adduct is the protonated molecule [M+H]⁺. However, cations such as ammonium (NH₄⁺), sodium (Na⁺), and potassium (K⁺) readily form [M+Na]⁺, [M+K]⁺, and [M+NH₄]⁺ adducts [1]. As demonstrated in the penicillin G case study, more complex adducts like [M+2K-H]⁺ can also form, where one metal cation displaces an acidic proton and another adducts to a basic site [21]. In negative ion mode, deprotonation to form [M-H]⁻ is typical, but adducts with anions like chloride ([M+Cl]⁻) or formate ([M+CHO₂]⁻) are also frequently observed [1]. The strategic use of anions with low proton affinity, such as bromide (Br⁻) or iodide (I⁻), has been shown to mitigate ionization suppression in complex matrices by facilitating the removal of excess sodium ions, thereby reducing chemical noise [20].

Strategic Intentional Adduct Formation for Analytical Enhancement

Enhancing Ionization Efficiency and Signal Response

Intentional adduct formation is a powerful tool for analytes with poor proton affinity or that are challenging to ionize via traditional pathways. A prominent example is the analysis of lipids under normal-phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) conditions, where the non-polar solvents are incompatible with standard ESI. A validated solution is the post-column addition of lithium chloride (LiCl) in water-isopropanol, which promotes the formation of lithium adducts [M+Li]⁺ [11]. This approach provides access to molecular ion information for neutral lipids like triacylglycerols (TG) and sterol esters (SE), which otherwise fragment heavily or ionize poorly under APCI. The lithium adducts also yield structurally informative fragmentation patterns in MS² and MS³ experiments [11].

Another powerful strategy is ammonium salt doping, particularly with ammonium fluoride (NH₄F). Studies across multiple MSI techniques, including IR-MALDESI, MALDI, and nano-DESI, have reported significant increases in ion abundance for a range of biomolecules. The proposed mechanism involves the highly electronegative fluoride ion capturing protons to facilitate the formation of [M-H]⁻ ions in negative mode [22]. The effect is pronounced; nano-DESI-MSI observed a 10–110-fold signal increase for various lipid classes using a 500 µM NH₄F dopant [22]. The atomic properties of the halide play a critical role, with the smaller, more electronegative fluoride (compared to Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) resulting in the largest signal enhancement, likely due to its positioning in the ESI droplet interior and its stronger interactions with water clusters [22].

Controlling Adduct Distribution for Quantitative Accuracy

Perhaps the most critical application of intentional adduction is to force the analyte signal into a single, dominant ion species, thereby improving quantitative accuracy and reliability. The case study of penicillin G, a potassium salt, is a quintessential example. Initial analysis in acetonitrile/water without additives showed no [M+H]⁺ signal (m/z 335) but a dominant [M+K]⁺ peak (m/z 373) and a second intense peak at m/z 411, identified as the [M+2K-H]⁺ adduct [21]. This distribution is problematic for quantification, as the efficiency of ion formation could vary with the sample's inherent potassium content.

The research team systematically tested two additive strategies, summarized in the workflow below.

The results, summarized in the table below, demonstrate that while acidification successfully produced the protonated molecule, the addition of potassium acetate to drive the formation of a single, intense metal adduct provided the best quantitative ion [21].

Table 2: Optimization Results for Penicillin G Analysis via ESI-MS

| Ion Species | Theoretical m/z | Relative Intensity (No Additive) | Relative Intensity (0.2% Formic Acid) | Relative Intensity (50 µM Potassium Acetate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M+H]⁺ | 335 | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| [M+K]⁺ | 373 | 100% | 5% | 2% |

| [M+2K-H]⁺ | 411 | 80% | 10% | 100% (Highest Intensity) |

Managing Unintended and Problematic Adduct Formation

Unintended adducts predominantly manifest as metal ion adducts, notably with sodium ([M+Na]⁺) and potassium ([M+K]⁺), which can suppress the desired protonated or deprotonated molecules and complicate mass spectra. Key contamination sources include:

- Glassware: The glass manufacturing process introduces metal salts that can leach into aqueous solutions. A primary mitigation strategy is to use plastic vials instead of glass for LC-MS analyses, though one must be aware of potential plasticizer leaching [23].

- Solvents and Additives: HPLC-grade solvents, particularly acetonitrile, can contain surprising amounts of sodium and other metal ions. Selecting high-purity MS-grade solvents is crucial [23].

- Biological Samples: These contain high concentrations of various salts that lead to adduct formation and matrix suppression. Rigorous sample preparation protocols like solid-phase extraction (SPE) or liquid-liquid extraction are often necessary to clean up samples prior to ESI-MS analysis [23].

- Laboratory Hygiene: Soaps, detergents, and residues from previous users of shared instrumentation are insidious sources of salts. A best practice is to flush the instrument thoroughly after each run [23].

Advanced Strategies for Complex Matrices

For samples that cannot be thoroughly desalted without losing the analyte or altering its native state, advanced ionization strategies are required. The use of submicron or theta emitters (with internal diameters < 1 µm) has been shown to significantly reduce metal ion adduction. The principle is that smaller initial droplets contain fewer metal ions, leading to cleaner spectra [20]. Theta emitters, which feature a septum dividing the capillary into two channels, allow for the rapid mixing of a sample containing non-volatile salts with a volatile ammonium acetate stream just prior to ionization. This promotes a population of droplets relatively depleted of salts, enabling the mass analysis of proteins and complexes directly from physiologically relevant buffers [20].

Furthermore, gas-phase activation techniques can be employed to decluster heavily adducted ions after they are formed. Applying collisional activation in the interface region (using the cone voltage or declustering potential) or in a subsequent collision cell can energize the ions, causing the weakly bound adducts (like solvent molecules or salts) to dissociate, thereby reducing spectral complexity and baseline noise [23] [20].

Essential Experimental Protocols and Toolkit

Detailed Protocol: Intentional Lithium Adduction for Lipid Analysis

This protocol enables the coupling of normal-phase LC (NPLC) with ESI-MS for the analysis of neutral lipids, adapted from a study analyzing wheat and soya lipid extracts [11].

- Chromatographic Separation: Perform NPLC separation using non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, toluene, dichloromethane) on a suitable NPLC column.

- Post-Column Addition Setup: Connect a syringe or auxiliary pump containing the doping solution to the LC effluent via a low-dead-volume T-connector. Ensure all tubing is chemically resistant.

- Doping Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of lithium chloride (LiCl) in water-isopropanol. The exact concentration must be optimized but is typically in the low mM range.

- Infusion and Mixing: Infuse the LiCl solution at a precise, controlled flow rate to mix with the column effluent post-separation. The combined flow is then directed into the ESI source.

- MS Detection: Operate the mass spectrometer in positive ESI mode. Monitor for [M+Li]⁺ adducts of target lipid classes (e.g., triacylglycerols, sterol esters). Utilize MS² and MS³ fragmentation of these adducts to obtain structural information on fatty acid chains and sterol nuclei.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Adduct Management

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate (Volatile) | MS-compatible buffer for exchange of non-volatile salts; promotes [M+NH₄]⁺ or [M+H]⁺/[M-H]⁻. | Standard concentration: 10-200 mM. Maintains protein conformation in "native" MS [20]. |

| Ammonium Fluoride (NH₄F) | ESI dopant for significant signal enhancement in negative mode, particularly for lipids and metabolites. | Optimal concentration is critical (e.g., ~70 µM for IR-MALDESI); enhances [M-H]⁻ formation [22]. |

| Lithium Chloride (LiCl) | Additive for forming [M+Li]⁺ adducts of low-/medium-polarity lipids in NPLC-ESI-MS. | Post-column addition is required for NPLC compatibility [11]. |

| Potassium Acetate | Additive to control and drive formation of a single, dominant metal adduct species (e.g., [M+2K-H]⁺). | Used to force ion current into one channel for improved quantitative accuracy [21]. |

| Formic Acid | Common mobile phase additive for positive mode to promote [M+H]⁺ formation via solution acidification. | Typical concentration 0.1-0.2%. Avoid with sodium-sensitive analytes [21]. |

| Plastic Vials | Sample vials to minimize leaching of sodium and potassium ions from glass. | Potential for plasticizer contamination; use high-quality, MS-certified vials [23]. |

| Theta Emitters / Submicron Emitters | Specialized emitters to analyze samples directly from high-salt, physiologically relevant buffers. | Reduces adduction via smaller droplet formation; requires specialized pullers [20]. |

The dichotomy between intended and unintended adduct formation represents a central paradigm in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Unintended adducts from contamination introduce analytical chaos, complicating spectra and jeopardizing quantification. In contrast, the strategic, intentional promotion of specific adducts is a sophisticated tool that can unlock ionization for stubborn analytes, boost signal intensity, and impose order on the ionization process for superior quantitative results. The journey from viewing adducts as a nuisance to wielding them as a deliberate instrument of analysis is a hallmark of advanced ESI-MS practice. By applying the principles, strategies, and practical methods outlined in this guide—from simple solvent additives to advanced emitter technology—researchers and drug development professionals can transform their understanding of adduct formation from a problem to be solved into a powerful parameter for method optimization.

Strategic Control and Exploitation of Adducts for Enhanced Analysis

The direct coupling of normal-phase liquid chromatography (NP-LC) with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) presents significant technical challenges that have limited its widespread adoption in analytical chemistry. Unlike reversed-phase chromatography, which predominantly uses MS-compatible solvents like water, methanol, and acetonitrile, normal-phase separation relies on hydrophobic organic solvents such as hexane, chloroform, and ethyl acetate that are fundamentally incompatible with stable electrospray ionization [24]. These solvents exhibit poor conductivity, low polarity, and rapid evaporation characteristics that disrupt the electrostatic spraying process essential for ESI operation. Additionally, the inherent incompatibility of these normal-phase solvents with the ionization process results in unstable spray formation, significantly reduced sensitivity, and potentially complete ionization failure [24].

Within the broader context of electrospray ionization research, understanding and controlling adduct formation is crucial for successful MS analysis. The formation of mass adducts represents a common phenomenon in ESI-MS that is poorly understood yet profoundly impacts analytical sensitivity and accuracy [3]. As research by Schug, McNair, and others has demonstrated, adduct formation can be influenced by numerous factors including mobile phase composition, inorganic ion concentration, and the presence of specific functional groups in analytes [3]. When considering normal-phase LC-ESI-MS, these challenges are exacerbated by the solvent systems employed, creating a dual problem of both ionization efficiency and unpredictable adduct formation that can complicate spectral interpretation and quantitative analysis.

The fundamental solvent limitations of normal-phase chromatography with ESI-MS have prompted researchers to investigate alternative approaches, with post-column additive introduction emerging as a promising solution to bridge this compatibility gap. This technique allows the analytical benefits of normal-phase separations – particularly for non-polar compounds, chiral separations, and compounds that retain poorly in reversed-phase systems – to be maintained while overcoming the ionization barriers presented by traditional normal-phase solvents [24] [25].

The Science of Post-Column Modification for ESI Compatibility

Fundamental Principles of ESI Incompatibility with NP Solvents

Electrospray ionization operates through the formation of a stable Taylor cone and subsequent Coulombic explosion of charged droplets, a process fundamentally dependent on the physicochemical properties of the solvent system. Normal-phase solvents typically exhibit low dielectric constants and poor conductivity, which directly impede the efficient formation of charged droplets necessary for successful ion generation [24]. The non-polar nature of solvents like hexane and chloroform significantly reduces their ability to stabilize charges, while their rapid evaporation characteristics can lead to premature aerosol formation or incomplete desolvation in the ESI source. These factors collectively contribute to the well-documented ionization suppression observed when attempting direct coupling of NP-LC with ESI-MS [24].

The ionization mechanism in electrospray involves multiple complex processes including droplet formation, solvent evaporation, and ion emission, each sensitive to solvent properties. Methanol and acetonitrile, the workhorse solvents of reversed-phase LC-MS, possess ideal properties for ESI including appropriate surface tension, boiling point, and dielectric constant. In contrast, normal-phase solvents disrupt the delicate charge separation process, leading to inefficient ion production. Research findings indicate that the signal suppression encountered with NP solvents can be so severe that alternative ionization techniques, particularly atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), are often recommended for normal-phase applications [24]. APCI operates through a different mechanism involving gas-phase chemical ionization that proves more tolerant to the organic solvents used in normal-phase chromatography, though it may not be suitable for all analyte classes [24].

Post-column additive introduction addresses NP-LC/ESI-MS incompatibility by modifying the mobile phase composition after chromatographic separation but prior to ionization. This technique introduces a MS-compatible solvent containing ionization-enhancing agents that transform the physicochemical properties of the eluent stream, creating an environment conducive to stable electrospray formation [25]. The approach preserves the chromatographic integrity achieved through normal-phase separation while overcoming the ionization barriers presented by the original mobile phase.

The effectiveness of this strategy was demonstrated in a method developed for analyzing acid herbicides and their degradation products, where post-column addition of ammonia in methanol significantly enhanced ionization in negative ESI mode [25]. In this application, the researchers utilized a normal-phase separation with a water-methanol mobile phase containing 2 mM ammonium acetate. The post-column introduction of 0.8 M ammonia in methanol at a flow rate of 0.05 mL/min into the primary chromatographic flow of 0.15 mL/min resulted in substantially improved sensitivity for the target compounds, particularly the degradation products that exhibited poor ionization efficiency without this modification [25].

Table 1: Common MS-Compatible Additives for Post-Column Introduction

| Additive Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Bases | Ammonia, Trimethylamine | Enhance negative mode ionization for acidic compounds | ESI, APCI |

| Volatile Acids | Formic acid, Acetic acid | Promote positive mode ionization for basic compounds | ESI, APCI |

| Volatile Salts | Ammonium acetate, Ammonium formate | Facilitate adduct formation and charge stabilization | ESI |

| Polar Solvents | Methanol, Isopropanol, Methanol-water mixtures | Improve solvent polarity and droplet formation | ESI |

The mechanistic role of these additives extends beyond simply adjusting polarity. They function by multiple complementary actions: modifying the surface tension and conductivity of the final solution, providing readily ionizable species that facilitate charge transfer to analytes, and in some cases, promoting specific adduct formation that enhances detection of target compounds [25] [1]. For instance, the introduction of ammonium salts can promote the formation of [M+NH₄]⁺ adducts in positive ion mode, while acetate addition can generate [M+CH₃COO]⁻ adducts in negative ion mode, providing alternative ionization pathways for compounds that exhibit poor protonation or deprotonation efficiency [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Workflow for Post-Column Additive Methods

The implementation of successful post-column additive introduction for NP-LC/ESI-MS requires careful method development and optimization. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and procedural steps in establishing a robust analytical method using this approach:

Figure 1: Method development workflow for post-column additive introduction in NP-LC-ESI-MS.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Acidic Compound Analysis

Based on the research examining acid herbicides and their degradation products [25], the following specific protocol demonstrates the successful application of post-column additive introduction:

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 (50 × 4.6 mm i.d., 1.8 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Water-methanol gradient with 2 mM ammonium acetate

- Flow Rate: 0.15 mL/min

- Gradient Program: Methanol content varying from 65% to 90% over the separation

- Injection Volume: Typically 10-20 μL

Post-Column Modification Setup:

- Additive Solution: 0.8 M ammonia in methanol

- Preparation: 6.5 mL of ammonium hydroxide (21% w/w) added to 93.5 mL methanol

- Additive Flow Rate: 0.05 mL/min

- Mixing Tee: Use a low-dead-volume PEEK mixing tee

- Connection: Capillary tubing (approximately 100 μm i.d.) of minimal length

Mass Spectrometric Parameters:

- Ionization Mode: Negative ion electrospray (ESI-)

- Source Temperature: Optimized between 300-350°C

- Ion Spray Voltage: Typically -3500 to -4500 V

- Nebulizer Gas: Optimized for stable spray formation

- Detection: Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) with two transitions per compound

This methodology enabled low nanogram-per-liter determination of acid herbicides and their degradation products in surface water samples, demonstrating the sensitivity achievable with properly optimized post-column introduction [25]. The addition of ammonia significantly enhanced ionization efficiency for the degradation products, which traditionally exhibited poor response in conventional LC-ESI-MS methods.

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of post-column additive methods requires attention to several practical considerations. The flow rate ratio between the chromatographic mobile phase and the additive stream must be carefully optimized to balance sufficient modification of eluent properties against potential dilution effects. In the cited method [25], a 3:1 ratio (0.15 mL/min analytical flow vs. 0.05 mL/min additive flow) provided optimal enhancement without significant peak broadening.

The mixing efficiency between the chromatographic effluent and the additive stream critically impacts method performance. Inadequate mixing can result in heterogeneous ionization conditions and consequently, signal instability. The use of specially designed mixing tees with appropriate internal volumes and capillary dimensions following the tee promotes complete mixing before the ESI source.

System compatibility represents another crucial consideration. As noted in forum discussions on NP-HPLC/MS compatibility, HPLC systems may require modification for normal-phase eluents, including seal changes and thorough flushing to eliminate buffer salts when switching between reversed-phase and normal-phase modes [24]. These precautions prevent system damage and maintain chromatographic integrity.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of post-column additive introduction for NP-LC/ESI-MS requires specific reagents and instrumentation designed to address the unique challenges of this technique. The following table summarizes the key components of the "research toolkit" for this application:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Post-Column Additive Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Hydroxide | Provides basic medium for negative ion ESI enhancement | 0.8 M in methanol [25] | Use high purity (e.g., OmniTrace Ultra, >99%) |

| Formic Acid | Acidic additive for positive ion ESI enhancement | 0.1-1.0% in methanol or isopropanol | Volatile; compatible with ESI-MS |

| Ammonium Acetate | Provides ammonium ions for adduct formation | 2-50 mM in mobile phase [25] | Volatile salt; avoid precipitation |

| Methanol (HPLC-MS Grade) | Polar organic solvent for additive preparation | HPLC-MS grade with low residue | Maintains ESI compatibility |