Advanced Interface Configurations for Peptide Analysis: A Guide for Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the current computational and analytical interfaces revolutionizing peptide research.

Advanced Interface Configurations for Peptide Analysis: A Guide for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the current computational and analytical interfaces revolutionizing peptide research. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of peptide analysis, details practical methodologies for mass spectrometry and structure prediction, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents validation frameworks for comparing tool performance. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this resource empowers scientists to select and implement the most effective interface configurations to accelerate the discovery and development of next-generation peptide therapeutics, diagnostics, and vaccines.

Understanding the Peptide Analysis Landscape: Core Concepts and Strategic Importance

The Expanding Role of Peptides in Therapeutics and Diagnostics

Peptides represent a unique class of pharmaceutical compounds that occupy the middle ground between small molecule drugs and larger biologics, offering superior specificity for targeting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) while maintaining satisfactory binding affinity and cellular penetration capabilities [1] [2]. Since the landmark introduction of insulin in 1922, peptide therapeutics have fundamentally reshaped modern pharmaceutical development, with over 60 peptide drugs currently approved for clinical use in the United States, Europe, and Japan, and more than 400 in various stages of clinical development globally [1] [2]. The peptide synthesis market, valued at $627.72 million in 2024, is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.93% to approximately $1,346.82 million by 2034, reflecting the expanding therapeutic applications and commercial interest in this modality [3].

This growth is largely driven by peptides' exceptional therapeutic properties, including high biological activity and specificity, reduced side effects, low toxicity, and the fact that their degradation products are natural amino acids, which minimizes systemic toxicity [1] [4]. The successful approval and market dominance of peptide drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Rybelsus) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro), which collectively generated billions in annual sales, underscore the transformative potential of peptide-based therapies for metabolic disorders, oncology, and rare diseases [1].

Comparative Analysis of Peptide-Based Therapeutics

Market Leadership and Therapeutic Performance

The peptide therapeutics market has demonstrated robust growth, dominated by metabolic disorder treatments while expanding into diverse therapeutic areas. The table below summarizes the commercial performance and therapeutic applications of leading peptide drugs.

Table 1: Market Performance and Therapeutic Applications of Leading Peptide Drugs

| Peptide Drug | Primary Indication(s) | Key Molecular Target(s) | 2024 Sales (USD Hundred Million) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide (Ozempic) | Type 2 Diabetes, Obesity | GLP-1 Receptor | $138.90 [1] | First oral GLP-1 RA; significant weight loss efficacy |

| Dulaglutide (Trulicity) | Type 2 Diabetes | GLP-1 Receptor | $71.30 [1] | Once-weekly dosing; cardiovascular risk reduction |

| Semaglutide (Rybelsus) | Type 2 Diabetes | GLP-1 Receptor | $27.20 [1] | First oral GLP-1 receptor agonist; high patient compliance |

| Tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound) | Type 2 Diabetes, Obesity | GIP and GLP-1 Receptors | N/A (Approved 2023) [1] | Dual receptor agonism; superior efficacy in clinical trials |

The remarkable commercial success of GLP-1 receptor agonists highlights the growing demand for peptide-based therapies, particularly in metabolic diseases. Tirzepatide represents a significant advancement as the first dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, demonstrating superior performance in the SURPASS phase III trials over single receptor agonists like dulaglutide and semaglutide [1]. Future candidates like retaglutide, which targets GCGR, GIPR, and GLP-1R, are emerging for treating type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, and obesity, indicating a trend toward multi-targeting peptides with enhanced therapeutic profiles [1].

Technological Platforms for Peptide Synthesis and Design

The development of peptide therapeutics relies on advanced synthesis technologies and computational design tools. The following table compares the major technological platforms enabling peptide drug development.

Table 2: Comparison of Peptide Synthesis and Design Technologies

| Technology Platform | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Leading Companies/ Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Sequential amino acid addition on solid support [3] | High efficiency, speed, simplicity; driven to completion with excess reagents [3] | Requires specialized equipment; high temperatures and strict reaction conditions [3] | Thermo Fisher, Merck KGaA, Agilent Technologies [5] |

| Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS) | Peptide chain growth in solution [3] | Flexibility in chemistry; high purity and yield; scale-up capabilities [3] | Time-consuming; labor-intensive purification steps [3] | Bachem, CordenPharma [5] [3] |

| Computational Peptide-Protein Interaction Tools | Analysis and design of peptide-protein interfaces [6] [2] | Enables rational design; predicts binding affinity and specificity | Requires expertise in computational methods | ATLIGATOR, Peptipedia [6] [4] |

| Integrated Peptide Databases | Consolidated information from multiple databases [4] | User-friendly; comprehensive data (92,055 sequences); predictive capabilities | Limited to existing knowledge | Peptipedia [4] |

The competitive landscape for peptide synthesis is led by established companies like Thermo Fisher Scientific, Merck KGaA, and Agilent Technologies, who provide comprehensive solutions including reagents, instruments, and synthesis services [5]. SPPS currently dominates therapeutic peptide production due to its efficiency and simplicity, though LPPS remains valuable for specific applications requiring high purity and flexibility in chemistry [3]. Computational tools like ATLIGATOR facilitate the understanding of frequent interaction patterns and enable the engineering of new binding capabilities by transferring motifs to user-defined scaffolds [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Alanine Scanning for Critical Residue Identification

Objective: To determine the contribution of individual amino acids to the biological activity of a therapeutic peptide.

Methodology:

- Peptide Library Synthesis: Generate a library of peptide analogs where individual amino acids in the lead sequence are systematically substituted with alanine [2].

- Biological Activity Assay: Screen each alanine-substituted analog for biological functionality using target-specific assays (e.g., receptor binding affinity, cellular response) [2].

- Data Analysis: Identify critical residues where alanine substitution results in significant loss of activity (>50% reduction typically indicates a critical residue) [2].

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: Correlate residue criticality with structural features to guide optimization [2].

Applications: This classic screening method enables researchers to identify which amino acids are essential for maintaining biological activity, providing crucial information for peptide optimization while maintaining targeting specificity and affinity [2].

Protocol: Termini Modification for Enhanced Stability

Objective: To improve proteolytic stability and in vivo half-life of peptide therapeutics through chemical modification.

Methodology:

- Terminal Assessment: Evaluate susceptibility to proteolysis by serum aminopeptidases (N-terminal) and carboxypeptidases (C-terminal) [2].

- Modification Strategy:

- Stability Validation: Conduct in vitro plasma stability assays and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies to confirm improved half-life [2].

- Functionality Confirmation: Verify that modifications maintain target binding affinity and biological activity through appropriate assays [2].

Applications: This approach addresses one of the major drawbacks of peptide drugs - their rapid proteolytic degradation in serum - thereby improving bioavailability and reducing dosing frequency [2].

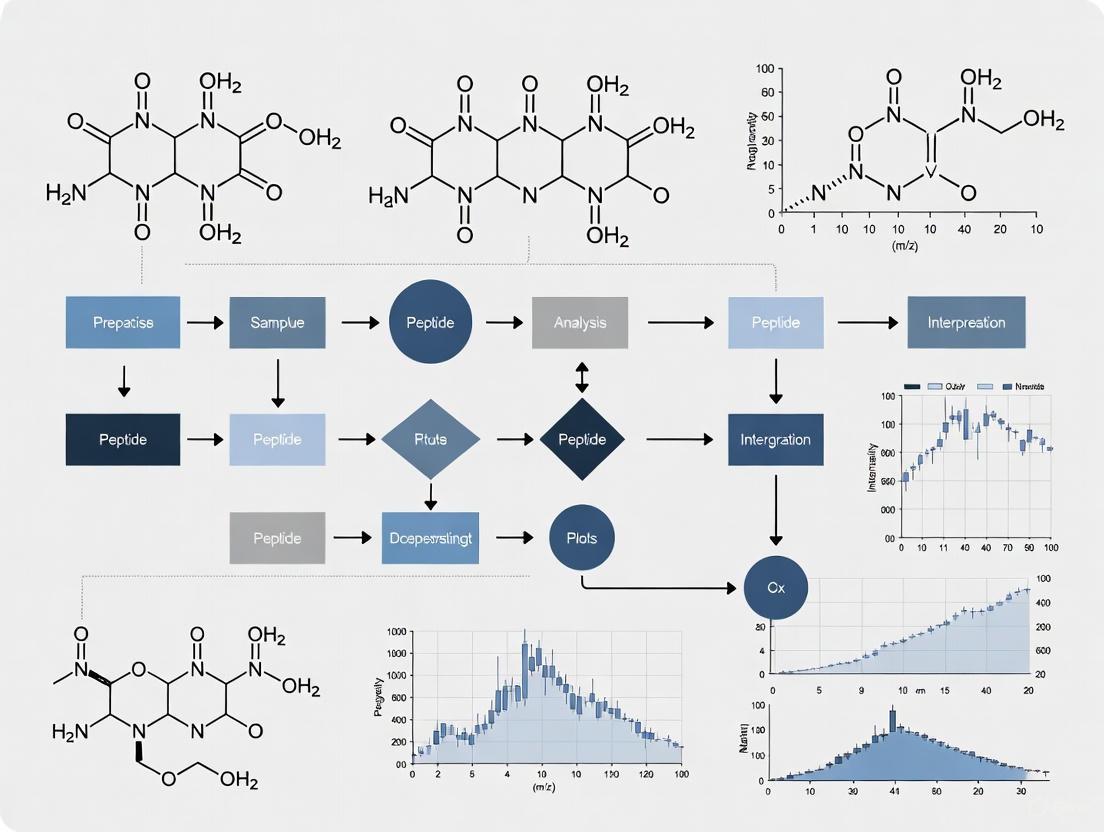

Visualization of Peptide Therapeutic Development Workflows

Peptide Drug Development Pathway

Peptide-Protein Interaction Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Peptide Analysis

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Representative Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Synthesizers | Automated solid-phase peptide synthesis | High-throughput capabilities; temperature control; monitoring systems | Agilent Technologies, Merck KGaA [5] |

| Specialty Resins & Protecting Groups | SPPS solid support and amino acid protection | Acid-labile; microwave-compatible; diverse functional groups | Thermo Fisher Scientific [5] |

| Chromatography Systems | Peptide purification and analysis | HPLC/UHPLC; preparative scale; high resolution | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Agilent Technologies [5] |

| Peptide Databases | Sequence analysis and activity prediction | Integrated information; machine learning applications; user-friendly | Peptipedia [4] |

| Computational Design Tools | Peptide-protein interaction analysis | Pattern recognition; motif extraction; 3D visualization | ATLIGATOR [6] |

The field of peptide therapeutics continues to evolve with several promising trends shaping its future. Next-generation peptide drugs are increasingly focusing on multifunctional agonists that simultaneously target multiple receptors, as demonstrated by the success of tirzepatide and the development of triagonist peptides targeting GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors [1] [2]. Advances in delivery systems, particularly for oral administration as pioneered by semaglutide (Rybelsus), are addressing one of the historical limitations of peptide drugs - their typically low oral bioavailability [1]. Furthermore, peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) and cell-targeting peptide (CTP)-based platforms show particular promise in overcoming challenges associated with traditional small molecule therapies, enhancing efficiency, and reducing adverse effects, with multiple platforms now in clinical trials [1].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in peptide drug development is accelerating the design of novel peptide sequences with optimized binding characteristics and reduced immunogenicity [5]. Tools like Peptipedia, which integrates information from 30 databases with 92,055 amino acid sequences, represent significant advances in consolidating peptide knowledge and enabling predictive analytics [4]. Additionally, the application of peptides in diagnostic domains continues to expand, with the first peptide radiopharmaceuticals like [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC for diagnosing somatostatin receptor-positive neuroendocrine tumors highlighting the versatility of peptide-based technologies in both therapeutic and diagnostic applications [1].

As peptide synthesis technologies advance and computational design tools become more sophisticated, the expanding role of peptides in therapeutics and diagnostics promises to deliver increasingly precise and customized treatment options for a wide range of diseases, ultimately advancing the era of precision medicine in pharmaceutical development.

Peptide-based therapeutics represent a rapidly growing class of pharmaceuticals that bridge the gap between small molecules and large biologics, offering high specificity and potency for treating conditions ranging from metabolic disorders to cancer [1] [7]. However, their development is hampered by significant analytical challenges centered on stability, degradation, and delivery. These intrinsic molecular characteristics directly impact the accuracy, reproducibility, and success of peptide research and development. The complex physicochemical properties of peptides, including their susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, poor membrane permeability, and structural instability, create substantial hurdles for researchers attempting to obtain reliable analytical data [8] [9]. This guide objectively compares these challenges and the experimental methodologies used to overcome them, providing a framework for evaluating analytical configurations within peptide research. As the peptide therapeutics market expands—projected to reach USD 778.45 million by 2030—addressing these challenges becomes increasingly critical for advancing therapeutic innovation [10].

Key Challenge 1: Structural Stability and Degradation

Mechanisms of Peptide Instability

Peptides face multiple stability challenges throughout their analytical lifecycle, primarily stemming from their inherent chemical and physical properties. The susceptibility to degradation arises from two primary mechanisms: enzymatic proteolysis and chemical degradation (hydrolysis, oxidation, and deamidation) [8] [11]. This instability is exacerbated during sample collection, storage, and analysis, with factors such as temperature, pH, and matrix effects significantly accelerating degradation processes. The complex structures of peptides with multiple functional groups and potential conformational variations make sequence verification, purity assessment, and structural characterization far more difficult than with traditional small molecules [8]. Furthermore, their broad concentration range in biological samples creates a complex mixture that challenges standard analytical methods, increasing the risk of undetected impurities or structural inconsistencies that can compromise research outcomes.

Table 1: Major Pathways of Peptide Instability and Contributing Factors

| Instability Pathway | Primary Contributing Factors | Impact on Analytical Results |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Degradation [8] [9] | Presence of proteases in plasma and tissues; sample handling time | Decreased recovery of parent peptide; generation of metabolite interference |

| Chemical Hydrolysis [11] | Extreme pH conditions; temperature fluctuations | Peptide bond cleavage; reduced assay accuracy and precision |

| Oxidation [8] | Exposure to light and oxygen; storage conditions | Structural modifications; formation of oxidative by-products |

| Deamidation [9] | pH shifts; elevated temperature; sequence-dependent | Altered peptide charge and properties; inaccurate quantification |

| Non-Specific Adsorption [8] [11] | Adherence to labware surfaces (glass, plastics) | Significant sample loss; poor reproducibility and recovery |

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Protocol 1: Evaluating Solution-Phase Stability

Objective: To determine the stability of a peptide under various storage conditions and pH environments to establish optimal handling procedures.

Materials: Peptide standard, low-binding microcentrifuge tubes, pH modifiers (e.g., acetic acid, ammonium hydroxide), protease inhibitors, HPLC system with UV/fluorescence detector or LC-MS/MS system, appropriate mobile phases.

Method:

- Prepare peptide stock solutions at a concentration relevant to experimental conditions (typically 1 mg/mL) in various buffers covering a pH range of 3.0-8.0.

- Aliquot samples into low-binding tubes and store at different temperatures (-80°C, -20°C, 4°C, and 25°C) for predetermined time points (immediately, 6h, 24h, 7 days) [8].

- At each time point, remove aliquots and immediately stabilize with acidification or protease inhibitors to halt degradation.

- Analyze samples using reverse-phase HPLC or LC-MS/MS with optimized separation conditions.

- Calculate percentage recovery by comparing peak areas to a freshly prepared standard. Monitor for new peaks indicating degradation products.

Data Interpretation: Stability is expressed as percentage of parent peptide remaining over time. The protocol identifies optimal pH and temperature conditions that minimize degradation, informing standard operating procedures for sample handling.

Protocol 2: Investigating Surface Adsorption

Objective: To quantify peptide loss due to non-specific adsorption to different laboratory surfaces and identify appropriate materials to minimize this loss.

Materials: Peptide standard, various container materials (standard polypropylene, low-binding polypropylene, glass), protein-blocking agents (e.g., BSA), LC-MS/MS system with optimized sensitivity.

Method:

- Prepare peptide solutions at concentrations spanning the expected analytical range (e.g., 1 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL) in appropriate matrix.

- Transfer aliquots to different container types, including those treated with surface passivation agents.

- Store samples for 1-4 hours at room temperature and 4°C to simulate typical handling conditions.

- Analyze samples and compare to a reference standard that was not exposed to container surfaces.

- Calculate recovery percentages for each container type and concentration.

Data Interpretation: Low-binding materials typically demonstrate recovery rates >85%, whereas standard plastics may show recovery as low as 50-60% for certain peptides, guiding selection of appropriate labware [8].

Peptide Degradation Pathways: This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which peptides degrade during analysis, leading to analytical inaccuracies.

Key Challenge 2: Analytical Detection and Quantification

Bioanalytical Complexities in Peptide Research

The accurate detection and quantification of peptides present unique challenges that differentiate them from both small molecules and large proteins. A primary obstacle is the typically low in vivo concentrations at which peptides remain biologically active, often in the nanomolar range, coupled with high levels of endogenous compounds that interfere with detection [8]. This complexity is magnified in mass spectrometry, where peptides generate multiple charged ions, spreading the signal across different charge states and reducing assay sensitivity [8]. Additionally, high protein binding in plasma further complicates accurate measurement, as strongly bound peptides may not be released using standard protein precipitation methods, leading to underestimation of total drug exposure [8]. These factors collectively demand specialized approaches to achieve the sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility required for rigorous peptide analysis.

Advanced Methodologies: LC-MS/MS Optimization

Protocol 3: Developing Ultra-Sensitive LC-MS/MS Assays

Objective: To establish a robust LC-MS/MS method capable of detecting and quantifying peptides at low nanogram to picogram per milliliter concentrations in complex matrices.

Materials: LC-MS/MS system with electrospray ionization (ESI), stable isotope-labeled internal standards, solid-phase extraction (SPE) plates, low-binding pipette tips and plates, mobile phase additives (e.g., formic acid), mass spectrometry-compatible solvents.

Method:

- Systematic Ion Optimization: Directly infuse peptide standard solution (100 ng/mL) to identify predominant precursor ions. Study multiple charge states to determine optimal transitions for each peptide [8].

- Sample Preparation: Implement sample concentration techniques such as solid-phase extraction or protein precipitation with acidified organic solvents to enrich peptides and clean up matrices.

- Chromatographic Optimization: Employ ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with sub-2μm particle columns to enhance separation efficiency. Use gradient elution with water/acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Operate in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode with carefully optimized collision energies for each transition. Use high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) when interference is anticipated.

- Validation: Establish lower limits of quantification (LLOQ) using signal-to-noise ratios >10:1. Validate accuracy (85-115%) and precision (<15% CV) across the analytical range.

Data Interpretation: A successfully optimized method should detect peptides at pharmacologically relevant concentrations with minimal interference from matrix components, enabling accurate pharmacokinetic profiling.

Protocol 4: Addressing Protein Binding Challenges

Objective: To accurately measure free versus protein-bound peptide concentrations for correct interpretation of pharmacokinetic data.

Materials: Ultracentrifugation equipment or equilibrium dialysis apparatus, physiological buffer (pH 7.4), LC-MS/MS system, appropriate membrane with molecular weight cutoff.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate peptide with plasma or relevant protein solution at 37°C for 30 minutes to establish binding equilibrium.

- Separation Techniques: Apply ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 hours or equilibrium dialysis for 4-16 hours to separate free from bound peptide.

- Analysis: Carefully collect the free fraction (ultracentrifugation) or buffer compartment (equilibrium dialysis) and analyze using the optimized LC-MS/MS method.

- Calculation: Determine the percentage of protein binding by comparing free concentration to total concentration.

Data Interpretation: Understanding protein binding extent is crucial for dose selection and pharmacodynamic predictions, as only the free fraction is considered pharmacologically active [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Platforms for Peptide Quantification

| Analytical Platform | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS [8] [11] | High specificity and selectivity; ability to monitor multiple analytes simultaneously; structural insight into metabolites | Multiple charge states reduce sensitivity; requires specialized expertise and optimization | Targeted quantification of peptides and metabolites in complex matrices |

| Ligand-Binding Assays [11] | Potentially higher throughput; established workflows for some targets | Antibody cross-reactivity; limited structural information; development time for new antibodies | High-throughput screening when specific antibodies are available |

| Affinity-Based Platforms (SomaScan, Olink) [12] | Capability for large-scale studies; extensive published literature for comparison | Limited to predefined targets; may miss novel modifications or metabolites | Large cohort studies; biomarker discovery |

| Benchtop Protein Sequencers (Platinum Pro) [12] | Single-amino acid resolution; no special expertise required; benchtop operation | Different data type from MS or affinity platforms; emerging technology | Sequence verification; novel peptide characterization |

Key Challenge 3: Delivery and Bioavailability

Biological Barriers to Effective Peptide Delivery

The delivery of peptide therapeutics faces substantial biological barriers that directly impact their analytical detection and therapeutic efficacy. The primary challenge is poor permeability across biological membranes, resulting from high polarity and molecular size, which leads to limited oral bioavailability (typically <1%) [1] [9]. This limited absorption is compounded by rapid enzymatic degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and quick clearance in the liver, kidneys, or blood, dramatically reducing half-life [1]. Additionally, the mucus layer and epithelial barriers in the GI tract further restrict absorption, with the densely-packed lipid bilayer structures of epithelial cell membranes and narrow paracellular space (3–10 Å) effectively blocking passive diffusion of most peptides [9]. These delivery challenges necessitate specialized formulation strategies and create analytical complexities in measuring true absorption and distribution.

Strategies for Enhanced Delivery and Assessment

Protocol 5: Evaluating Permeability Enhancement Strategies

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of various formulation approaches in improving peptide permeability using in vitro models.

Materials: Caco-2 cell monolayers or artificial membranes, permeability assay buffers, transport apparatus, LC-MS/MS system, permeation enhancers (e.g., absorption promoters, lipid-based systems), chemically modified peptide analogs.

Method:

- Model Preparation: Culture Caco-2 cells on permeable supports for 21 days until tight junctions form and transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values exceed 300 Ω·cm².

- Sample Application: Apply peptide solutions with and without permeability enhancers to the apical compartment. Include controls for monolayer integrity.

- Sampling: Collect samples from the basolateral compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Analysis: Quantify peptide concentration in basolateral samples using validated LC-MS/MS methods.

- Calculation: Determine apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) and compare between formulations.

Data Interpretation: Successful permeability enhancement typically shows 2-10 fold increases in Papp values while maintaining cell viability and monolayer integrity.

Protocol 6: Assessing Half-Life Extension Approaches

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of structural modifications in prolonging peptide circulation time.

Materials: Peptide analogs with half-life extension strategies (PEGylation, lipidation, Fc fusion), animal models, LC-MS/MS system, appropriate sampling equipment.

Method:

- Dosing: Administer modified and unmodified peptides via relevant routes (subcutaneous, intravenous) to animal models.

- Serial Blood Sampling: Collect blood samples at multiple time points post-administration (e.g., 5, 15, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours).

- Sample Processing: Immediately stabilize samples with protease inhibitors and process to plasma.

- Analysis: Quantify peptide concentrations using validated LC-MS/MS methods with appropriate sensitivity.

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Calculate key parameters including half-life (t½), area under the curve (AUC), and clearance (CL).

Data Interpretation: Successful half-life extension strategies demonstrate significantly increased half-life and AUC values compared to unmodified peptides, supporting less frequent dosing regimens [7].

Delivery Barriers and Strategies: This diagram outlines the major biological barriers to effective peptide delivery and corresponding strategies to overcome them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful peptide analysis requires specialized reagents and materials designed to address their unique challenges. The following toolkit outlines essential components for robust peptide research workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Peptide Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Binding Labware [8] | Minimizes peptide adsorption to surfaces | Essential for tubes, plates, and pipette tips; critical for hydrophobic peptides |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards [8] | Improves accuracy and precision of quantification | Corrects for recovery variations and matrix effects in LC-MS/MS |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails [8] | Prevents enzymatic degradation during processing | Must be added immediately upon sample collection |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Plates [11] | Sample cleanup and concentration | Enhances sensitivity and reduces matrix interference |

| LC-MS/MS Systems [8] [11] | High-sensitivity detection and quantification | Requires optimization for multiple charge states common with peptides |

| Ultra-Performance LC Columns [11] | Enhanced chromatographic separation | Sub-2μm particles provide superior resolution for complex mixtures |

| Permeation Enhancers [9] | Improves membrane penetration in delivery studies | Includes absorption promoters and lipid-based systems |

| pH Modifiers [9] | Stabilizes peptides in solution | Critical for maintaining peptide integrity during storage and analysis |

The analytical landscape for peptide research is defined by the intricate interplay between stability limitations, detection challenges, and delivery barriers. Successful navigation of this landscape requires integrated approaches that combine appropriate analytical platforms with specialized handling protocols. LC-MS/MS has emerged as the cornerstone technology for peptide quantification, offering the specificity needed to distinguish closely related analogs and metabolites, though it demands careful optimization to address peptides' multiple charge states and sensitivity limitations [8] [11]. The critical importance of sample handling cannot be overstated—implementing immediate stabilization, using low-binding materials, and controlling temperature conditions are essential practices that directly impact data quality and reproducibility [8]. As peptide therapeutics continue to expand into new therapeutic areas including metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and oncology, addressing these fundamental analytical challenges will remain pivotal for advancing both basic research and clinical development [7]. The experimental protocols and comparative analyses provided here offer a framework for researchers to systematically evaluate and optimize their analytical configurations, ultimately supporting the development of more effective peptide-based therapeutics.

Peptide analysis is a cornerstone of modern proteomics and drug discovery, enabling researchers to decipher complex biological systems and develop novel therapeutics. The field has evolved significantly from traditional analytical techniques to sophisticated computational approaches, each offering unique capabilities for characterizing peptide structures, interactions, and functions. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the predominant peptide analysis interfaces, from established workhorses like mass spectrometry to emerging AI-driven modeling platforms, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate technologies based on their specific experimental needs, resource constraints, and research objectives.

Core Peptide Analysis Technologies: A Comparative Framework

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Peptide Analysis Technologies

| Technology | Primary Applications | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Experimental Outputs | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Peptide identification, sequencing, post-translational modification (PTM) analysis, quantification [13] [14] | Mass accuracy (ppm), resolution, sensitivity (femtomole to attomole), dynamic range [14] | Mass-to-charge (m/z) spectra, fragmentation patterns, protein identification from peptide fragments [13] | Complex peptide mixtures (from digested proteins), often requires liquid chromatography separation [15] [13] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | 3D structure elucidation, molecular conformation, dynamics, stereochemistry, impurity profiling [16] | Magnetic field strength (MHz), resolution, ability to detect isomers and chiral centers [16] [17] | 1D and 2D spectra (e.g., COSY, HSQC, HMBC) showing atomic connectivity and spatial relationships [16] | Intact proteins or peptides in solution, typically requires deuterated solvents [16] |

| AI-Driven Modeling | Peptide-protein interaction prediction, complex structure modeling, de novo peptide design [18] [19] | DockQ score (0-1 scale), false positive rate (FPR), precision, recall [19] | Predicted 3D structures of complexes, binding affinity estimates, confidence metrics (e.g., p-DockQ) [19] | Protein and peptide sequences; structural templates where available [19] |

| Traditional Biochemical Methods | Peptide library screening, binding affinity measurement, functional characterization [20] [18] | Binding affinity (Kd), reaction kinetics, specificity, throughput [20] | Covalent binding confirmation (e.g., via SDS-PAGE), specificity profiles, kinetic parameters [20] | Purified protein/peptide components, potential need for labeling or immobilization [20] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Across Analysis Platforms

| Technology | Structural Resolution | Sensitivity | Quantitative Capability | Experimental Workflow Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | Medium (sequence level) | High (femtomole) [14] | Excellent (with labeling strategies) [13] [14] | High (sample preparation, separation, instrument operation) [15] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | High (atomic level) [16] | Low to Medium (millimolar) | Good (absolute quantification possible) [16] | Medium (specialized sample preparation, data interpretation) [16] |

| AI-Driven Modeling | High (atomic coordinates) [19] | N/A (computational) | N/A (predictive confidence scores) | Low to Medium (computational resources, expertise) [19] |

| Traditional Biochemical Methods | Low (functional assessment) | Variable | Good (with appropriate controls) [20] | Medium (assay development, optimization) [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analysis Modalities

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for Peptide Identification

LC-MS/MS represents the workhorse methodology for high-throughput peptide analysis in proteomics. The standard protocol involves multiple stages with specific quality control checkpoints [15].

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Protein Extraction: Isolate proteins from biological samples using appropriate lysis buffers while maintaining protease inhibition.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest proteins into peptides using sequence-specific proteases (typically trypsin) at 37°C for 4-18 hours.

- Peptide Cleanup: Desalt and concentrate peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction columns.

- Peptide Quantification: Determine peptide concentration using colorimetric assays (e.g., BCA assay) prior to analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis Parameters:

- Chromatography: Nano-flow HPLC systems with C18 reverse-phase columns (75μm internal diameter) at flow rates of 200-300 nL/min [13]

- Gradient: Shallow acetonitrile gradients (typically 2-35% over 60-120 minutes) for optimal peptide separation

- Mass Spectrometry: Data-dependent acquisition on hybrid instruments (e.g., LTQ-Orbitrap) with survey scans at high resolution (≥30,000) and MS/MS scans for top N precursors [14]

- Fragmentation: Collision-induced dissociation (CID) or higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) for peptide sequencing [14]

Performance Metrics Implementation: Rudnick et al. established 46 system performance metrics for rigorous quality assessment of LC-MS/MS analyses [15]. Key metrics include:

- Chromatographic Performance: Peak width at half-height (target: <30 seconds), interquartile retention time period

- Ion Source Stability: MS1 signal stability with minimal >10-fold fluctuations (IS-1A, IS-1B metrics)

- Dynamic Sampling Efficiency: Ratio of peptides identified by different numbers of spectra (DS-1A, DS-1B metrics)

- Identification Consistency: Monitoring elution order differences between runs (C-5A, C-5B metrics) [15]

AI-Driven Peptide-Protein Complex Prediction with TopoDockQ

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have revolutionized predictive modeling of peptide-protein interactions. The TopoDockQ workflow exemplifies this approach with enhanced accuracy for model selection [19].

Computational Protocol:

- Structure Prediction: Generate peptide-protein complex models using AlphaFold2-Multimer or AlphaFold3 with default parameters.

- Feature Extraction: Apply persistent combinatorial Laplacian (PCL) mathematics to characterize topological features and shape evolution at peptide-protein interfaces.

- Quality Assessment: Process topological features through the TopoDockQ deep learning model to predict DockQ scores (p-DockQ).

- Model Selection: Rank predicted complexes by p-DockQ scores and select highest-quality models for further analysis.

Validation Framework:

- Benchmark Datasets: Evaluate performance on standardized datasets (SINGLEPPD, PFPD, LEADSPEP) filtered to ≤70% sequence identity to training data [19]

- False Positive Reduction: TopoDockQ achieves at least 42% reduction in false positive rate compared to AlphaFold's built-in confidence score [19]

- Precision Enhancement: Implements 6.7% average increase in precision across diverse evaluation datasets while maintaining high recall [19]

ResidueX Workflow for Non-Canonical Peptides: For advanced applications incorporating non-canonical amino acids:

- Scaffold Selection: Prioritize natural peptide scaffolds generated by AlphaFold based on p-DockQ scores

- ncAA Incorporation: Systematically introduce non-canonical amino acids using the ResidueX workflow

- Conformation Validation: Assess structural integrity of modified peptides through molecular dynamics simulations [19]

NMR Spectroscopy for Peptide Structure Elucidation

NMR provides unparalleled atomic-level structural information for peptides in solution, making it indispensable for characterizing three-dimensional structure and dynamics [16].

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Isotope Labeling: For peptides >20 residues, incorporate ¹³C and ¹⁵N isotopes via recombinant expression or synthetic incorporation.

- Sample Conditions: Dissolve peptide to 0.1-1.0 mM concentration in appropriate deuterated buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, pH 6.5-7.5).

- Spectral Acquisition:

- 1D Experiments: ¹H NMR with water suppression, ¹³C NMR with DEPT editing

- 2D Experiments: COSY (proton-proton correlations), TOCSY (through-bond correlations), NOESY/ROESY (through-space correlations), HSQC (heteronuclear ¹H-¹³C correlations), HMBC (long-range ¹H-¹³C correlations) [16]

- Data Processing: Apply Fourier transformation, phase correction, and baseline correction to raw data.

Structure Calculation Protocol:

- Spectral Assignment: Sequentially assign all proton and carbon resonances using correlation data.

- Constraint Generation: Convert NOE cross-peaks into distance constraints, derive dihedral constraints from coupling constants.

- Structure Calculation: Implement simulated annealing protocols in programs like CYANA or XPLOR-NIH.

- Structure Validation: Analyze Ramachandran plots, restraint violations, and structural quality using MolProbity.

Application to Pharmaceutical Development: NMR structure elucidation services play critical roles in pharmaceutical development, including:

- API Characterization: Confirmation of active pharmaceutical ingredient structure and stereochemistry

- Impurity Profiling: Identification and structural determination of isomeric impurities undetectable by LC-MS

- Batch Consistency: Monitoring conformational stability across manufacturing lots [16]

Visualizing Analytical Workflows

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows for major peptide analysis technologies showing distinct pathways from sample preparation to analytical outputs.

Diagram 2: Decision framework for selecting appropriate peptide analysis methodologies based on research objectives and sample characteristics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Peptide Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Peptide Analysis Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Lys-C Proteases | Sequence-specific protein digestion into peptides | Mass spectrometry sample preparation | Protease purity, activity validation, digestion efficiency [13] |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Peptide desalting and concentration | Sample cleanup prior to LC-MS/MS | Recovery efficiency, salt removal capacity, compatibility with sample volume [13] |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, CD₃OD) | NMR-active solvents without interfering proton signals | NMR spectroscopy | Isotopic purity, cost, compatibility with sample pH range [16] |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC, TMT) | Quantitative proteomics using mass differentials | MS-based quantification | Labeling efficiency, cost, multiplexing capability, fragmentation characteristics [13] [14] |

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher System | Covalent peptide-protein conjugation | Biochemical validation of interactions | Reaction kinetics, specificity, compatibility with biological systems [20] |

| Phage Display Libraries | High-throughput screening of peptide binders | Functional peptide discovery | Library diversity, display efficiency, screening stringency [18] |

| AlphaFold2/3 Software | Protein-peptide complex structure prediction | AI-driven modeling | Computational requirements, sequence input requirements, confidence metrics [19] |

The evolving landscape of peptide analysis technologies offers researchers an expanding toolkit for addressing diverse scientific questions. Mass spectrometry remains the cornerstone for high-throughput identification and quantification, while NMR provides unparalleled structural details for well-behaved systems. Traditional biochemical methods continue to offer crucial functional validation, and AI-driven modeling has emerged as a transformative approach for predictive structural biology. The most effective research strategies often employ orthogonal methodologies that leverage the complementary strengths of multiple platforms, with selection criteria guided by specific research questions, sample characteristics, and resource constraints. As these technologies continue to advance—with MS achieving greater sensitivity, NMR becoming more accessible through benchtop systems, and AI models incorporating more sophisticated topological features—the integration of multiple analytical interfaces will further accelerate discoveries in peptide science and therapeutic development.

The integration of artificial intelligence and computational tools is revolutionizing peptide analysis, a field critical to advancing therapeutic drug development. However, the rapid emergence of new tools necessitates a structured framework for their evaluation. This guide establishes a standardized approach for assessing peptide-analysis tools based on three core criteria: predictive accuracy, user-experience usability, and computational throughput. We present a comparative analysis of contemporary platforms, supported by experimental data, to equip researchers and scientists with the methodology for selecting optimal tools for their specific research configurations.

Peptide analysis tools have become indispensable in modern bioinformatics and drug discovery pipelines. These tools address complex challenges from predicting peptide-protein interactions to optimizing peptide sequences for desired physicochemical properties. The performance of these tools directly impacts the speed, cost, and success of research outcomes. Yet, with diverse tools available, making an informed selection is challenging without consistent benchmarks.

Evaluating tools based solely on a single metric, such as claimed accuracy, provides an incomplete picture. A tool with high theoretical accuracy may be impractical due to a steep learning curve, poor integration into existing workflows, or prohibitive computational demands. Therefore, a holistic evaluation must balance three interconnected pillars: the accuracy of the results, the usability of the interface and workflow, and the throughput or computational efficiency. This guide defines these criteria and applies them to a selection of prominent tools, providing a model for objective comparison in the field.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Throughput

To objectively compare tool performance, we summarize key quantitative metrics from published in silico evaluations and benchmarks. These metrics primarily address the criteria of accuracy and throughput.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of AI-Driven Peptide Analysis Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Accuracy / Performance Metrics | Reported Experimental Throughput / Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| TopoDockQ [19] | Peptide-protein interface quality assessment | Reduces false positive rates by at least 42% and increases precision by 6.7% over AlphaFold2's built-in confidence score across five evaluation datasets [19]. | N/A |

| PepEVOLVE [21] | Dynamic peptide optimization for multi-parameter objectives | Outperformed PepINVENT, achieving higher mean scores (~0.8 vs. ~0.6) and best candidates with a score of 0.95 (vs. 0.87). Converged in fewer steps on a benchmark optimizing permeability and lipophilicity [21]. | N/A |

| Transformer-based AP Predictor [22] | Prediction of decapeptide aggregation propensity (AP) | Achieved high accuracy in AP prediction with a 6% error rate. Predictions were consistent with experimentally verified peptides [22]. | Reduced AP assessment time from several hours (using CGMD simulation) to milliseconds [22]. |

| InstaNovo/InstaNovo+ [23] | De novo peptide sequencing from mass spectrometry data | Exceeded state-of-the-art performance, identifying thousands of new human leukocyte antigens peptides not found with traditional methods [23]. | N/A |

Defining the Core Evaluation Criteria

A comprehensive tool evaluation extends beyond raw performance numbers. The following criteria form a triad for holistic assessment.

Accuracy and Reliability

For peptide research, accuracy is not a single metric but a multi-dimensional concept. Evaluators should consider:

- Predictive Precision: The tool's ability to correctly identify true positives. For example, TopoDockQ's 6.7% increase in precision directly translates to more reliable model selection and less time wasted on false leads [19].

- False Positive Rate (FPR): The proportion of incorrect positive identifications. A low FPR is critical. TopoDockQ's 42% reduction in FPR significantly enhances research efficiency [19].

- Generalization: Performance on data not seen during the tool's training phase. This is often tested on independent, time-filtered, or sequence-identity-filtered datasets to mitigate data leakage, as demonstrated in TopoDockQ's evaluation across five distinct "70%" subsets [19].

Usability and User Experience (UX)

Usability assesses how effectively and efficiently researchers can use the tool to achieve their goals. This is evaluated through qualitative UX research methods [24] [25]:

- Comparative Usability Testing: Pitting two or more tools or interfaces against each other using the same set of tasks with representative users. This method helps identify which design leads to faster task completion, fewer errors, and higher user satisfaction [24].

- Data-Driven Design Decisions: Leveraging behavioral data (e.g., where users click, time on task) over subjective opinions to inform interface improvements. This removes guesswork from tool design [24].

- Structured Data Analysis: A four-step process ensures insights are trustworthy:

- Collect relevant observational and behavioral data [25].

- Assess each data point for authenticity, consistency, and potential biases (e.g., was feedback spontaneous or led by the facilitator?) [26] [25].

- Explain the data by synthesizing observations into coherent insights about user behavior [25].

- Check the explanations for a "good fit" against the entire dataset, iterating as needed [25].

Throughput and Computational Efficiency

Throughput measures the computational resources required to obtain a result, directly impacting project timelines and costs.

- Speed-Up Factor: The relative improvement in processing time compared to a baseline method. The Transformer-based AP predictor's shift from hours to milliseconds represents a million-fold speed-up, enabling rapid screening that was previously impossible [22].

- Scalability: The tool's ability to maintain performance as the size of the input data (e.g., peptide library size, protein length) increases.

- Resource Consumption: The demand for hardware resources like CPU, GPU, and memory, which influences accessibility for research groups without high-performance computing infrastructure.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure reproducible and fair comparisons, the following experimental methodologies are employed in the field.

Protocol for In Silico Peptide Design Benchmarking

This protocol is used to benchmark generative and optimization tools like PepEVOLVE.

- Dataset Curation: A standardized benchmark dataset is selected, such as the Rev-binding macrocycle benchmark for optimizing permeability and lipophilicity [21].

- Baseline Establishment: A baseline model (e.g., PepINVENT) is run on the dataset to establish initial performance metrics [21].

- Experimental Run: The new tool (e.g., PepEVOLVE) is executed on the identical dataset with the same computational resources [21].

- Metric Comparison: Key performance indicators (KPIs) are compared, including:

- Mean score across generated peptides.

- Score of the best-performing candidate.

- Number of optimization steps required for convergence [21].

Protocol for Predictive Accuracy and Generalization

This protocol, used for tools like TopoDockQ, tests accuracy and robustness.

- Data Splitting: The primary training dataset (e.g., SinglePPD-Training) is held aside [19].

- Creation of Filtered Evaluation Sets: Multiple independent evaluation datasets (e.g., LEADSPEP, Latest, ncAA-1) are filtered to include only complexes with a protein-peptide sequence identity product of ≤70% relative to the training set. This creates the "70%" subsets (e.g., LEADSPEP_70%) to test generalization [19].

- Performance Measurement: The tool is run on these filtered sets, and metrics like precision, recall, F1 score, and false positive rate are calculated and compared against a standard (e.g., AlphaFold2's confidence score) [19].

Experimental workflow for assessing predictive accuracy and tool generalization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Beyond software, computational peptide research relies on key data resources and molecular modeling techniques.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Materials

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CGMD) Simulation [22] | Computational Method | Used as a validation tool to simulate peptide aggregation behavior and calculate metrics like Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) to define Aggregation Propensity (AP) [22]. |

| Filtered Evaluation Datasets (e.g., *_70%) [19] | Data Resource | Independent datasets filtered by sequence identity to the training data. Used to rigorously test a tool's generalization ability and prevent overestimation of performance due to data leakage [19]. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (NCAAs) [19] [21] | Molecular Building Block | Incorporated into peptide scaffolds to improve stability, bioavailability, and specificity. Their support is a key feature for advanced therapeutic peptide design [19]. |

| CHUCKLES Representation [21] | Data Schema | A SMILES-like representation that enables atom-level control over both natural and non-natural amino acids in peptide sequences, facilitating generative modeling [21]. |

| DockQ Score [19] | Evaluation Metric | A continuous metric (0-1) for evaluating the quality of peptide-protein interfaces, serving as a target for models like TopoDockQ to predict [19]. |

Integrated Workflow for Tool Evaluation and Selection

Selecting the right tool requires integrating all three criteria. The following workflow provides a logical pathway for researchers to make a data-driven decision.

Logical workflow for integrated tool evaluation

- Define Research Objective: Clearly state the primary goal (e.g., "optimize a lead peptide for permeability," "assess the quality of a docked peptide-protein complex").

- Assess Accuracy: Shortlist tools that demonstrate high performance on metrics relevant to the objective (see Table 1). Prioritize tools validated on independent datasets to ensure reliability.

- Evaluate Usability: For the shortlisted tools, investigate the user interface and workflow. If possible, conduct a lightweight comparative test. Is the tool well-documented? Does it integrate with your existing software environment? A tool with slightly lower accuracy but excellent usability may lead to higher overall productivity.

- Analyze Throughput: Consider computational demands against available resources. A high-throughput tool enables rapid iteration, which is crucial for screening large libraries or during iterative optimization cycles.

- Make an Integrated Decision: Weigh the findings from the three criteria. The optimal tool is the one that offers the best balance of robust accuracy, manageable usability, and acceptable throughput for the specific research context.

The landscape of peptide analysis tools is dynamic and powerful. Navigating it successfully requires moving beyond singular claims of performance. By adopting a structured evaluation framework based on Accuracy, Usability, and Throughput, researchers can make objective, defensible decisions. This guide provides the definitions, metrics, and experimental protocols to implement this framework. As the field evolves, applying these consistent criteria will be essential for validating new tools, driving iterative improvements in interface design, and ultimately accelerating the development of next-generation peptide therapeutics.

A Practical Toolkit: Configuring Interfaces for Mass Spectrometry and Structural Analysis

Leveraging PepMapViz for Versatile Peptide Mapping and Visualization from MS Data

Within the evolving landscape of peptide analysis research, the evaluation of interface configurations for mass spectrometry (MS) data interpretation has become increasingly critical. PepMapViz emerges as a versatile R package specifically designed to address the visualization challenges in proteomics research. This toolkit provides researchers with comprehensive capabilities for mapping peptides to protein sequences, identifying distinct domains and regions of interest, accentuating mutations, and highlighting post-translational modifications, all while enabling comparisons across diverse experimental conditions [27] [28]. The package represents a significant advancement in the toolkit available for MS data interpretation, filling a crucial niche between raw data processing and biological insight generation.

The importance of effective peptide visualization tools continues to grow alongside advancements in mass spectrometry technologies, which generate increasingly complex datasets. As noted in the literature, modern proteomics requires flexible tools that can integrate data from multiple sources and provide coherent visual representations for comparative analysis [29]. PepMapViz addresses this need by supporting data outputs from popular mass spectrometry analysis tools, enabling researchers to maintain their established workflows while enhancing their analytical capabilities through standardized visualization approaches. This positions PepMapViz as a valuable contributor to the peptide analysis research ecosystem, particularly for applications requiring comparative visualization across experimental conditions or software platforms.

Comparative Tool Analysis: Capabilities and Performance

Functional Capabilities Comparison

When evaluating interface configurations for peptide analysis, direct comparison of functional capabilities provides crucial insights for tool selection. The following table summarizes key features across PepMapViz and related platforms based on current documentation:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Peptide Mapping and Visualization Tools

| Feature | PepMapViz | Traditional Methods | Specialized Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Import Compatibility | Supports multiple popular MS analysis tools [29] | Often platform-specific | Variable, typically limited |

| Visualization Type | Linearized protein format with domain highlighting [27] | Basic sequence viewers | Domain-specific solutions |

| PTM Visualization | Comprehensive modification highlighting [28] | Limited or absent | Focused on specific modifications |

| Comparative Analysis | Cross-condition comparisons [29] | Manual processing required | Limited to specific applications |

| Immunogenicity Prediction | MHC-presented peptide cluster visualization [29] | Specialized tools only | Dedicated immunogenicity platforms |

| Implementation | R package with Shiny interface [28] | Various platforms | Standalone applications |

| Accessibility | Open source (MIT License) [28] | Mixed | Often commercial |

The comparative analysis reveals PepMapViz's particular strengths in multi-software compatibility and comparative visualization capabilities. Unlike traditional methods that often require researchers to switch between specialized tools for different analysis aspects, PepMapViz provides a unified environment for comprehensive peptide mapping. This integrated approach significantly enhances workflow efficiency, particularly for complex analyses involving multiple experimental conditions or data sources.

Application Performance Metrics

While comprehensive benchmark studies are not yet available in the literature, performance characteristics can be inferred from the tool's architecture and application scope. PepMapViz demonstrates particular effectiveness in:

- Cross-software data integration: The ability to import and harmonize peptide data outputs from multiple mass spectrometry analysis tools enables more robust comparative analyses than single-platform approaches [29]

- Antibody therapeutics development: Specialized functionality for visualizing Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)-presented peptide clusters in different antibody regions provides unique value for predicting immunogenicity during antibody drug development [27]

- Post-translational modification (PTM) analysis: Comprehensive PTM coverage visualization across different experimental conditions facilitates understanding of modification patterns and their potential functional consequences [29]

The package's implementation in R provides a foundation for reproducible research through scriptable analyses while maintaining accessibility via its interactive Shiny interface [28]. This dual-approach architecture caters to both computational biologists requiring programmable solutions and experimental researchers preferring graphical interfaces.

Experimental Framework and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Protocol

To objectively assess peptide mapping tools within research environments, we propose a standardized experimental protocol that leverages published methodologies:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Tool Performance Evaluation

| Stage | Procedure | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preparation | Curate datasets from multiple MS platforms (e.g., DIA, targeted proteomics) | Standardized input files |

| Tool Configuration | Implement identical analysis parameters across tools | Configuration documentation |

| Peptide Mapping | Execute sequence mapping with domain annotation | Mapping accuracy, coverage statistics |

| PTM Analysis | Process modified peptide datasets | Modification detection sensitivity |

| Comparative Visualization | Generate cross-condition comparisons | Visualization clarity, information density |

| Result Interpretation | Conduct blinded analysis by multiple domain experts | Consensus scores, insight generation |

This protocol emphasizes the importance of cross-platform compatibility testing, which aligns directly with PepMapViz's documented capability to import data from multiple mass spectrometry analysis tools [29]. The experimental design also addresses the need for standardized benchmarking metrics in visualization tool assessment, particularly for quantifying the effectiveness of comparative analyses across different experimental conditions.

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for utilizing PepMapViz in peptide mapping studies:

PepMapViz Experimental Workflow

This workflow initiates with data import functionality that supports multiple mass spectrometry data formats, followed by automated peptide mapping to parent protein sequences. The subsequent domain annotation and PTM highlighting stages leverage the package's specialized capabilities for identifying functional regions and modifications. The workflow culminates in comparative visualization across experimental conditions, a core strength of PepMapViz that enables researchers to identify patterns and differences across datasets [29] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for Peptide Mapping

Successful implementation of peptide mapping studies requires both computational tools and appropriate experimental resources. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in the context of PepMapViz-aided analyses:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Peptide Mapping Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometers | Generate raw peptide fragmentation data | Data generation for all downstream analysis |

| Protein Databases | Provide reference sequences for mapping | Essential for peptide-to-protein assignment |

| Enzymatic Reagents | (e.g., Trypsin) Protein digestion | Standardized sample preparation |

| PTM-specific Antibodies | Enrichment of modified peptides | Enhanced detection of post-translational modifications |

| Quantification Standards | Isotope-labeled reference peptides | Absolute quantification in targeted proteomics |

| Chromatographic Columns | Peptide separation pre-MS analysis | Sample fractionation to reduce complexity |

| Cell Culture Systems | Biological context for experimental conditions | Generation of physiologically relevant samples |

These research reagents form the foundational ecosystem within which PepMapViz operates, transforming raw experimental data into biologically interpretable visualizations. The integration between wet-lab reagents and computational tools like PepMapViz represents a critical interface in modern proteomics, enabling researchers to connect experimental manipulations with computational insights through effective visualization strategies.

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Specialized Use Cases

PepMapViz demonstrates particular utility in several advanced application domains that extend beyond conventional peptide mapping:

- Antibody Therapeutics Development: The package enables visualization of MHC-presented peptide clusters across different antibody regions, providing insights into potential immunogenicity risks during biotherapeutic development [29] [27]. This application addresses a critical challenge in antibody engineering by predicting regions likely to elicit immune responses.

- Cross-Platform Method Validation: Researchers can compare results across different mass spectrometry analysis software using PepMapViz's unified visualization framework, facilitating method development and validation studies [29]. This capability is particularly valuable when evaluating new instrumentation or analytical approaches.

- Disease Mechanism Elucidation: By enabling detailed visualization of peptide coverage across protein domains and modifications under different experimental conditions, PepMapViz supports investigations into molecular mechanisms underlying disease processes [27]. The comparative visualization capabilities are essential for identifying differences between healthy and disease states.

Integration Framework

The following diagram illustrates how PepMapViz integrates within a comprehensive peptide analysis ecosystem, highlighting key interfaces with data sources and downstream applications:

PepMapViz Research Integration Framework

This integration framework highlights PepMapViz's role as an analytical hub that connects diverse data sources with research applications. The package interfaces with established search tools like Comet [29] and specialized databases such as CysDB for cysteine modification information [29], consolidating information from these disparate sources into coherent visual representations. This integrated approach enables researchers to transition seamlessly from data processing to biological interpretation, accelerating insight generation in therapeutic development and disease research applications.

PepMapViz represents a significant advancement in the toolkit available for peptide mapping and visualization from mass spectrometry data. Its capabilities for comparative visualization, cross-platform data integration, and specialized applications in immunogenicity prediction position it as a valuable contributor to proteomics research workflows. While comprehensive performance benchmarks relative to all alternatives are not yet available in the literature, the tool's documented functionality and implementation approach address several critical gaps in current peptide analysis methodologies.

For researchers evaluating interface configurations for peptide analysis, PepMapViz offers a compelling combination of analytical versatility and accessibility through both programmatic and interactive interfaces. Future developments in this field would benefit from standardized benchmarking approaches and expanded functionality for emerging proteomics technologies, building upon the foundation established by tools like PepMapViz to further enhance our ability to extract biological insights from complex peptide datasets.

Utilizing Protein Cleaver for In Silico Proteolytic Digestion and Peptide Detection Prediction

In silico proteolytic digestion represents a critical preliminary step in mass spectrometry-based proteomics, enabling researchers to predict the peptide fragments generated from protein sequences through enzymatic cleavage. This process is vital for experiment design, optimizing protein identification, and characterizing challenging targets. This guide provides a performance-focused comparison of Protein Cleaver, a recently developed web tool, against established and next-generation computational alternatives. The evaluation is framed within a broader thesis on configuring optimal computational interfaces for peptide analysis, assessing tools based on their digest prediction capabilities, integration of structural and sequence annotations, and applicability to drug discovery workflows.

Protein Cleaver is an interactive, open-source web application built using the R Shiny framework. It is designed to perform in silico protein digestion and systematically annotate the resulting peptides. Its key differentiator is the integration of peptide prediction with comprehensive sequence and structural visualization features, mapping peptides onto both primary sequences and tertiary structures from databases like the PDB or AlphaFold. It utilizes the cleavage rules from the cleaver R package, which provides rules and exceptions for 36 proteolytic enzymes as described on the Expasy PeptideCutter server [30].

A primary strength of Protein Cleaver is its user-friendly interface, which combines the neXtProt sequence viewer and the MolArt structural viewer. This provides researchers with an interactive platform to visually inspect regions of a protein that are likely or unlikely to be identified, incorporating additional annotations such as disulfide bonds, post-translational modifications, and disease-associated variants retrieved in real-time from UniProt [30].

Other tools in the ecosystem offer varied approaches. ProsperousPlus is a command-line tool pre-loaded with models for 110 protease types, offering breadth but lacking integrated visualization [30]. PeptideCutter from Expasy is a classic web-based tool but does not integrate structural mapping or bulk analysis features [30]. Emerging machine learning methods, such as those based on the ESM-2 protein language model and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), represent a shift towards deep learning for cleavage site prediction. The ESM-2 model, fine-tuned on data from the MEROPS database, uses transformer encoders to generate contextual embeddings for each amino acid to predict cleavage sites, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering. However, it is limited to natural amino acids and linear peptides [31]. The GNN approach represents peptides as hierarchical graphs, enabling it to handle cyclic peptide structures and those containing non-natural amino acids, which is a significant advantage for peptide therapeutic development [31].

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison of In Silico Digestion Tools

| Feature | Protein Cleaver | ProsperousPlus | PeptideCutter (Expasy) | ESM-2/GNN Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Enzymes | 36 | 110 | ~20 | 29 (in cited study) |

| Structural Visualization | Yes (Integrated 3D viewer) | No | No | No |

| Sequence Annotation | Extensive (UniProt, PTMs, variants) | Limited | Basic | Model-dependent |

| Bulk Digestion Analysis | Yes | Not specified | No | Possible |

| Handling of Non-Natural AAs | No | Not specified | No | Yes (GNN approach only) |

| Primary Use Case | Proteomics experiment planning & visualization | Protease-specific cleavage prediction | Basic cleavage site prediction | Cleavage prediction for therapeutic peptide design |

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Proteome Coverage and Enzyme Efficiency

A critical metric for in silico digestion tools is their ability to simulate proteome coverage. Protein Cleaver's bulk digestion feature was used to assess the performance of 36 proteases across the entire reviewed human proteome (UniProt). The findings demonstrate that the choice of protease significantly impacts theoretical coverage [30].

While trypsin is the gold standard in practice, the analysis revealed that neutrophil elastase, a broad-specificity protease, could theoretically cover 42,466 out of 42,517 proteins in the human proteome, slightly outperforming trypsin, which covered 42,403 proteins. However, this broad specificity can produce shorter, less unique peptides, potentially complicating protein identification in real experiments. This highlights a key utility of Protein Cleaver: enabling data-driven protease selection by balancing coverage with peptide suitability for MS analysis [30].

Table 2: Theoretical Proteome Coverage of Selected Proteases in the Human Proteome (as assessed by Protein Cleaver)

| Protease | Specificity | Theoretical Protein Coverage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Elastase | Broad | 42,466 / 42,517 (∼99.9%) | Highest coverage, but peptides may be less informative |

| Trypsin | High (C-term to K/R) | 42,403 / 42,517 (∼99.7%) | Gold standard; ideal peptide properties for MS |

| Chymotrypsin (High Spec.) | High (C-term to F/W/Y) | ~42,450 (Inferred) | Effective for hydrophobic/transmembrane regions |

| Proteinase K | Broad | ~42,460 (Inferred) | Very broad specificity, high coverage |

Application on Challenging Targets: G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs are notoriously difficult to analyze via MS due to their hydrophobic transmembrane domains, which lack the lysine and arginine residues targeted by trypsin. Protein Cleaver was employed to compare trypsin and chymotrypsin for in silico digestion of GPCRs [30].

The tool predicted that chymotrypsin (high specificity) produces a significantly higher number of identifiable peptides for GPCRs than trypsin. This is because chymotrypsin cleaves at aromatic residues (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), which are more prevalent in transmembrane domains. Protein Cleaver's structural viewer visually confirmed that peptides identifiable with chymotrypsin were predominantly located in these traditionally "hard-to-detect" regions [30]. This case study underscores the tool's value in designing targeted proteomics experiments for specific protein families, particularly integral membrane proteins.

Comparison with Advanced ML Predictors

The performance of traditional rule-based tools like Protein Cleaver can be contrasted with modern machine learning approaches. A study on ESM-2 and GNN models reported their performance on 29 different proteases from the MEROPS database [31]. While direct head-to-head numerical comparison is not possible due to different test sets, the ML models demonstrate high predictive accuracy by learning complex patterns from large datasets of known cleavage sites.

For example, the ESM-2 model leverages its self-attention mechanism to capture contextual relationships within the peptide sequence, while the GNN approach excels by representing the peptide as a graph of atoms and amino acids, making it uniquely capable for peptides with non-natural amino acids or cyclic structures [31]. This represents a different paradigm: whereas Protein Cleaver applies known biochemical rules, ML models learn these rules from data, which can potentially capture more complex or subtle cleavage specificities.

Experimental Protocols for Tool Evaluation

Protocol 1: Bulk Protease Assessment for Proteome-Wide Coverage

This protocol, derived from the methodology in Protein Cleaver's foundational publication, allows for the systematic evaluation of multiple proteases [30].

- Input Preparation: Compile a list of UniProt accessions for the organism of interest (e.g., the entire reviewed human proteome) or provide a multi-FASTA file of protein sequences.

- Parameter Setting:

- Set the minimum and maximum peptide length (e.g., 6–30 amino acids).

- Set the mass range suitable for MS detection (e.g., 700–3500 Da).

- Define the number of allowed miscleavages (e.g., 0–2) to simulate real-world experimental conditions.

- Tool Execution: Run the bulk digestion analysis, selecting all proteases to be evaluated (e.g., the 36 available in Protein Cleaver).

- Output Analysis:

- For each protease, record the number and percentage of proteins that yield at least one peptide within the set parameters.

- Calculate the average number of peptides per protein and the average sequence coverage.

- Rank proteases based on the desired metric (e.g., overall coverage or number of unique peptides).

Protocol 2: Targeted Analysis for Specific Protein Families

This protocol, based on the GPCR case study, is designed to optimize enzyme selection for challenging targets [30].

- Target Selection: Upload a set of protein sequences belonging to a specific family (e.g., GPCRs, ion channels) via their UniProt accessions or a FASTA file.

- Comparative Digestion: Perform in silico digestion using a panel of candidate enzymes (e.g., trypsin, chymotrypsin, AspN, GluC).

- Data Extraction and Visualization:

- For each enzyme, extract the list of predicted peptides and their positions.

- Use the integrated sequence viewer to highlight "detectable" versus "undetectable" regions for each enzyme.

- Use the structural viewer (if structures are available from PDB or AlphaFold) to map the peptides onto the 3D model and identify domains that are well-covered or poorly covered.

- Decision Point: Select the enzyme that provides the best combination of sequence coverage, number of peptides, and coverage of functionally or therapeutically relevant domains.

Diagram 1: Workflow for evaluating proteases using Protein Cleaver

Table 3: Key Resources for In Silico and Experimental Peptide Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Cleaver | Software Tool | Interactive in silico digestion with structural annotation and bulk analysis [30]. |

| MEROPS Database | Database | Curated resource of proteases and their known cleavage sites; used for training ML models [31]. |

| UniProt Knowledgebase | Database | Provides protein sequences and functional annotations; primary input for digestion tools [30]. |

| BIOPEP-UWM | Database | Repository of bioactive peptide sequences; used for predicting bioactivity in hydrolysates [32]. |

| Trypsin | Protease | Gold-standard enzyme for proteomics; cleaves C-terminal to Arg and Lys [30]. |

| Chymotrypsin | Protease | Cleaves C-terminal to aromatic residues; useful for hydrophobic domains missed by trypsin [30]. |

| Bromelain | Protease | Plant cysteine protease used in generating bioactive peptide hydrolysates from food sources [32]. |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Source of predicted protein structures for visualization when experimental structures are unavailable [30]. |

The choice of an in silico proteolytic digestion tool depends heavily on the research question. Protein Cleaver stands out for its integrated, visual, and systematic approach to protease selection, particularly for standard proteomics and challenging targets like GPCRs. Its strengths are user-friendliness, excellent visualization, and robust bulk analysis for experiment planning. Rule-based alternatives like PeptideCutter offer simplicity, while ProsperousPlus provides a wider array of proteases. For specialized applications involving cyclic or synthetic peptides containing non-natural amino acids, emerging machine learning models like GNNs and fine-tuned protein language models represent the cutting edge, though they often lack the integrated annotation and visualization features of Protein Cleaver. A cohesive peptide analysis research interface would ideally leverage the strengths of each—perhaps using ML for precise cleavage prediction and a tool like Protein Cleaver for downstream visualization and experimental planning.