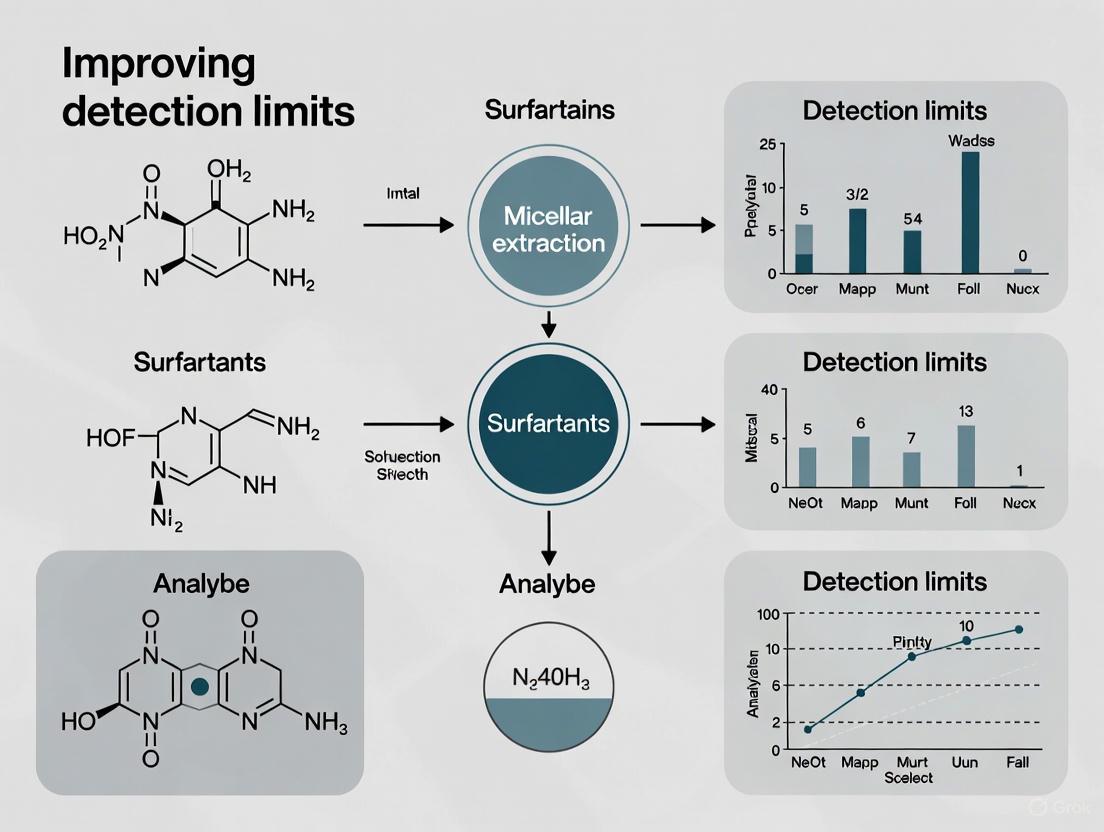

Advanced Strategies to Improve Detection Limits in Micellar Extraction: A Guide for Analytical Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies to enhance the sensitivity and lower the detection limits of micellar extraction methods, crucial for analyzing trace-level compounds in complex matrices.

Advanced Strategies to Improve Detection Limits in Micellar Extraction: A Guide for Analytical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies to enhance the sensitivity and lower the detection limits of micellar extraction methods, crucial for analyzing trace-level compounds in complex matrices. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of micelle-mediated extraction, details cutting-edge methodological workflows and their applications in biomedical and environmental analysis, discusses systematic optimization and troubleshooting of key parameters, and validates these techniques through comparative analysis with conventional methods. The scope is firmly grounded in the latest research, offering practical insights for implementing these efficient and sustainable sample preparation techniques.

Micellar Fundamentals: Unlocking the Core Principles for Enhanced Sensitivity

FAQs on Micelle Fundamentals and CMC

What is the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC)? The Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) is the specific concentration of a surfactant in a solution above which the formation of micelles becomes appreciable. Below the CMC, surfactant molecules primarily exist as monomers. Once the concentration surpasses the CMC, any additional surfactant molecules spontaneously aggregate to form micelles, which are self-assembled structures where hydrophobic chains are shielded from the aqueous environment by hydrophilic head groups [1] [2].

Why is determining the CMC critical for improving detection limits in analytical methods like micellar extraction? The CMC is a fundamental parameter for optimizing micellar extraction methods. Operating at or above the CMC ensures a sufficient population of micelles to solubilize target analytes, directly impacting the method's extraction efficiency and recovery rate [3]. Furthermore, understanding the CMC of natural surfactants, like tea saponin, is key to developing greener analytical methods that can offer high selectivity and lower toxicity without compromising performance, thereby potentially improving practical detection limits by reducing background interference [3] [4].

My solution properties show a gradual change instead of a sharp break at the CMC. What does this indicate? A gradual transition, rather than a sharp break in properties like surface tension or conductivity, often indicates a low aggregation number or a less cooperative assembly process [1]. The steepness of the transition at the CMC is highly dependent on the aggregation number (n). For surfactants that form large micelles (high n), the transition is very sharp and cooperative, resembling a two-state system. For aggregates with smaller n, the transition from monomers to aggregates will be more gradual [1].

How can I distinguish between a protein-detergent complex and an empty detergent micelle in structural biology? This is a common challenge, especially with small membrane proteins. A protein embedded in a detergent micelle will typically yield a particle of a different size and potentially more structural heterogeneity compared to an empty micelle. Strategies to confirm you are looking at the protein complex include:

- Multiple Ab Initio Models: Generate several independent initial models; consistent features across models are more likely to be protein-derived.

- 2D Classification Refinement: Carefully sort your particles through multiple rounds of 2D classification to separate classes that show defined secondary structure features (like alpha-helices) from those that are featureless, which are likely empty micelles [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent CMC values obtained from different measurement techniques.

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Tension | Measures the reduction of surface tension with increasing surfactant concentration. A break point marks the CMC. | Widely used; provides information on surface activity [2]. | Can be affected by impurities and equilibrium time [6]. |

| Conductivity | Measures the change in specific conductance with concentration. A slope change is observed for ionic surfactants at the CMC. | Simple and straightforward for ionic surfactants [6]. | Not suitable for non-ionic surfactants [6]. |

| Fluorescent Probing | Uses a hydrophobic dye (e.g., pyrene) whose fluorescence spectrum shifts upon incorporation into a micelle. | Highly sensitive; very low sample consumption; suitable for low CMC values [2]. | Requires specific dye and instrumentation; can be influenced by dye-micelle interactions. |

Recommended Protocol: Conductivity Measurement for Ionic Surfactants

- Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the ionic surfactant (e.g., SDS).

- Dilution Series: Create a series of dilutions covering a concentration range below and above the expected CMC.

- Measurement: Measure the specific conductance of each solution at a constant temperature using a calibrated conductivity meter.

- Data Analysis: Plot conductivity (y-axis) versus surfactant concentration (x-axis). Fit linear trendlines to the data points below and above the break point. The CMC is determined as the concentration at the intersection of these two linear regions [6].

Problem: Low extraction recovery during micellar extraction of analytes from a complex matrix.

- Cause 1: Surfactant concentration is below or too close to the CMC.

- Solution: Ensure the surfactant concentration is sufficiently above the CMC to maximize the number of micelles available for solubilizing target analytes. For instance, in the extraction of flavonoids from Ginkgo nuts using tea saponin, the concentration was optimized to 3% (w/v) to achieve high recovery [3].

- Cause 2: The micelle structure is not suitable for the target analyte.

- Cause 3: Instability of the micellar system under experimental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH).

- Solution: Perform stability studies, including freeze/thaw cycles and storage at elevated temperatures, to ensure the microemulsion remains stable. Remember that these systems are lyotropic and can be temperature-sensitive [7].

Problem: Difficulty in forming a stable microemulsion for solubilizing high amounts of oil-soluble actives.

- Cause: Incorrect ratio of surfactant to co-surfactant, or an unsuitable co-surfactant.

- Solution: Utilize ternary phase diagrams to map out the precise ratios of water, surfactant, and co-surfactant (e.g., a C5–C6 linear alcohol) that yield a stable, transparent microemulsion phase. This is an empirical but systematic approach to identify the optimal formulation window [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | A synthetic anionic surfactant. Known for its strong solubilizing power and well-characterized CMC [1]. | Commonly used in model studies of micelle formation and protein denaturation. |

| Tea Saponin | A natural, non-ionic biosurfactant derived from Camellia plants. Amphiphilic, with a hydrophobic triterpenoid core and hydrophilic sugar chains [3]. | Used as a green alternative for micellar extraction of flavonoids and lactones from Ginkgo nuts [3] [4]. |

| DDM (n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside) | A non-ionic detergent frequently used in membrane protein biochemistry for solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins. | Purification of a small membrane-anchored protein with three transmembrane helices for structural studies [5]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 6000 | A polymer used in aqueous two-phase systems (ATPS). | Combined with salts like (NH₄)₂SO₄ for the in-situ enrichment of target compounds after micellar extraction [3]. |

| Pyrene | A fluorescent probe. Its fluorescence spectrum is sensitive to the polarity of its environment, making it ideal for CMC determination. | Used in the fluorescent probe method to determine the CMC of amphiphilic polymers and surfactants [2]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Micelle Formation and CMC Determination

Green Micellar Extraction Workflow

Core Principles: The Micellar Solubilization Powerhouse

Micelles are nanoscale aggregates formed by surfactant molecules in aqueous solutions. When the surfactant concentration exceeds the critical micelle concentration (CMC), these molecules spontaneously self-assemble into organized structures with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic shell [8]. This unique architecture is the foundation of their solubilizing power.

The hydrophobic core provides a compatible microenvironment for non-polar analytes, effectively shielding them from the aqueous surroundings. Simultaneously, the interactive shell, composed of the surfactants' polar head groups, stabilizes the entire structure in water and can engage in electrostatic or other specific interactions with analytes [8]. Solubilization occurs when poorly water-soluble compounds become incorporated into the micelles—either within the hydrophobic core, at the core-shell interface, or within the palisade layer of the shell—significantly increasing their apparent solubility in the aqueous phase [8].

This solubilization capability is harnessed in micelle-mediated extraction (MME), a green alternative to conventional solvent extraction. MME uses aqueous surfactant solutions instead of harmful organic solvents to efficiently isolate target substances from complex matrices [8]. The selectivity and efficiency of the extraction are governed by the interactions between the analyte and the specific surfactant used.

Troubleshooting Common Micellar Extraction Experiments

This section addresses frequent challenges researchers face when working with micellar extraction techniques.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Micellar Extraction

| Problem | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Extraction Efficiency | Surfactant concentration below CMC [8] | Confirm surfactant concentration is well above the CMC. Ensure stock solutions are fresh and properly prepared. |

| Incorrect surfactant type for target analyte [9] | Match surfactant character to analyte: ionic surfactants for charged species, non-ionic for non-polar compounds [9]. | |

| Inefficient mass transfer | Incorporate ultrasound (UAMME) or microwave (MAMME) to enhance analyte transfer into micelles [8]. | |

| Phase Separation Issues (Cloud Point Extraction) | No phase separation upon heating | Verify temperature is above the cloud point of the specific non-ionic surfactant being used [9]. |

| Surfactant-rich phase volume is too small | Increase the initial sample volume or surfactant concentration to obtain a larger volume of the coacervate phase for easy handling [9]. | |

| Formation of Stable Emulsions | Presence of surfactant-like compounds (e.g., phospholipids, proteins) in the sample [10] | - Gently swirl instead of shaking the vessel [10].- Add brine to increase ionic strength and "salt out" the emulsion [10].- Centrifuge the sample to break the emulsion [10]. |

| Poor Detection Limits | Insufficient preconcentration factor | Increase the sample-to-surfactant ratio in CPE to maximize the concentration of analyte in the small surfactant-rich phase [9]. |

| Interference from surfactant in detection | For HPLC, use surfactants compatible with detection (e.g., Brij-35 for UV). For MS detection, consider supported liquid extraction to avoid introducing surfactant into the instrument [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I increase the selectivity of my micellar extraction for a specific analyte? Selectivity can be fine-tuned by manipulating the chemical environment. You can adjust the pH of the solution to control the charge state of ionizable analytes, which affects their interaction with ionic micelles. Adding salts (salting-out effect) can enhance the extraction efficiency of hydrophobic compounds into the micellar phase. Furthermore, selecting a surfactant with a specific head group (e.g., cationic CTAB for anionic analytes) can leverage electrostatic interactions for improved selectivity [9].

Q2: Why is my micellar solution viscous or turbid, and is this a problem? A slight increase in viscosity is normal for concentrated surfactant solutions. However, turbidity can indicate that the solution is at or near its cloud point. For standard MME, this is undesirable. Ensure you are working at a temperature sufficiently below the cloud point. If you are intentionally performing cloud point extraction, turbidity is the expected first step before phase separation upon heating [9].

Q3: Can I use micellar extraction for metal ion analysis? Yes. This typically involves a two-step process. First, metal ions are chelated with a hydrophobic organic ligand to form a neutral complex. Subsequently, this complex is solubilized and extracted into the hydrophobic core of the micelles, often followed by cloud point extraction to preconcentrate the metals for trace analysis [9].

Protocols for Key Micellar Extraction Methodologies

Protocol: Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) for Preconcentration of Organic Analytes

Principle: This method uses a thermo-reversible phase separation of a non-ionic surfactant solution to isolate and pre-concentrate analytes into a small volume of a surfactant-rich phase [9].

Materials:

- Non-ionic surfactant (e.g., Triton X-114)

- Water bath or thermostat

- Centrifuge

- Sample solution containing target analytes

Procedure:

- Surfactant Addition: To an aqueous sample (e.g., 10 mL), add a calculated volume of a concentrated surfactant stock solution to achieve a final concentration of 0.5-2% (w/v) [9].

- Equilibration: Incubate the sample in a water bath at a temperature 10-20°C above the cloud point of the surfactant (e.g., 4°C for Triton X-114 is ~23°C, so incubate at ~40°C) for 10-15 minutes [9].

- Phase Separation: The solution will become turbid and separate into two distinct phases: a small, dense surfactant-rich phase and a larger aqueous phase. To accelerate separation, centrifuge the sample for 5-10 minutes [9].

- Phase Recovery: Carefully remove the bulk aqueous phase by pipette. The surfactant-rich phase (typically 50-500 μL), now containing the preconcentrated analytes, can be dissolved in a compatible solvent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile) for direct analysis via HPLC or other techniques [9].

Protocol: Green Extraction of Flavonoids using a Biosurfactant

Principle: This protocol uses tea saponin, a natural and biodegradable biosurfactant, for the ultrasonic-assisted micellar extraction of medium- and low-polarity compounds like flavonoids, combining high efficiency with environmental friendliness [3].

Materials:

- Tea saponin (purity ≥98%)

- Ultrasonic bath

- Polyethylene Glycol 6000 (PEG-6000) and (NH₄)₂SO₄ for in-situ ATPE

- Centrifuge

- Ginkgo nut powder or other plant material

Procedure:

- Micellar Extraction: Weigh 0.5 g of Ginkgo nut powder into a tube. Add 10 mL of a 2-3% (w/v) aqueous tea saponin solution. Subject the mixture to ultrasonic extraction for 20 minutes [3].

- In-situ Aqueous Two-Phase Enrichment: To the extraction mixture, add 0.6 g of PEG-6000 and 1.4 g of (NH₄)₂SO₄. Shake vigorously until the salts and polymer are completely dissolved. A two-phase system will form spontaneously [3].

- Phase Separation & Analysis: Centrifuge the mixture to complete phase separation. The target flavonoids (e.g., kaempferol) and lactones (e.g., ginkgolides) will partition into the upper PEG-rich phase. This phase can be collected directly for analysis by HPLC [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Micellar Extraction Research

| Reagent / Material | Type/Function | Key Characteristics & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic Surfactant | Common in CPE and MLC. Krafft point ~15-18°C; avoid use in cold labs and with potassium salts to prevent precipitation [11]. |

| Triton X-114 | Non-ionic Surfactant | The benchmark surfactant for Cloud Point Extraction. Low cloud point (~23°C), forms a surfactant-rich phase of small volume [9]. |

| Pluronic F127 | Polymeric Surfactant (Triblock Copolymer) | Forms stable micelles with a large core for solubilizing highly hydrophobic drugs (e.g., Cannabidiol). Biocompatible for drug delivery applications [12]. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Cationic Surfactant | Used for extracting anionic analytes via electrostatic attraction. Krafft point 20-25°C; requires warm lab environment [11]. |

| Tea Saponin | Biosurfactant | Natural, biodegradable, low-toxicity non-ionic surfactant. Ideal for green extraction of active ingredients from functional foods and herbs [3]. |

| Brij-35 | Non-ionic Surfactant | Often used in Micellar Liquid Chromatography (MLC). High cloud point (~100°C), suitable for separations at room temperature [11]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts of Micellar Systems

Q1: What are the fundamental structural differences between normal, reverse, and polymeric micelles?

A1: The core structural difference lies in the organization of the amphiphilic molecules in response to the solvent environment.

- Normal Micelles: These form in polar solvents like water. The hydrophilic "head" regions face outward into the solvent, while the hydrophobic single-tail regions are sequestered in the micelle centre, creating an oil-in-water structure [13].

- Reverse Micelles: These form in non-polar solvents. Here, the hydrophilic head groups are sequestered in the micelle core, and the hydrophobic tails extend out into the solvent, creating a water-in-oil system [13].

- Polymeric Micelles: These are formed from amphiphilic block copolymers and possess a core-shell structure, often with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic corona, similar to normal micelles but with much higher molecular weight building blocks [14] [13]. They are known for their remarkably low critical micellar concentration (CMC) and high kinetic stability, which can make them "kinetically frozen," meaning they do not readily disassemble upon dilution [13].

Q2: How does the concept of Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) apply to these different systems, and why is it critical for extraction efficiency?

A2: The CMC is the minimum concentration of surfactant required for micelle formation. It is pivotal because micelles are the active agents responsible for solubilizing and extracting target compounds.

- For Normal & Reverse Micelles: Extraction efficiency is highly dependent on operating above the CMC to ensure a sufficient population of micelles is present to host the analytes [13]. Factors like temperature, pH, and ionic strength can affect the CMC.

- For Polymeric Micelles: They have a much lower CMC (typically 0.0001 to 0.001 mol/L) compared to surfactant micelles [13]. This low CMC is a significant advantage for extractions and drug delivery, as the micellar structures remain stable even under high dilution, preventing premature disassembly and loss of encapsulated cargo [14] [13].

Q3: What are "stimuli-responsive" or "intelligent" polymeric micelles, and how can they improve targeted extraction or drug delivery?

A3: Stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles are designed to rupture their structure and release encapsulated drugs or compounds in response to specific "environmental" triggers [14]. This enhances target-specific delivery and controls the release rate. Key triggers include:

- pH: Micelles can be engineered to destabilize in the acidic microenvironment of tumors (e.g., using poly(l-histidine)) or within cellular endosomes, leading to rapid drug release at the target site [14] [15].

- Redox Potential: Gemini polymeric micelles containing disulfide bonds can be cleaved by intracellular glutathione, a reducing agent, leading to controlled drug release [15].

- Enzymes: Micelles can be broken apart by enzymes that are overexpressed in diseased tissues. For instance, amphiphilic block copolymers have been designed where an enzyme-responsive dendron triggers disassembly and cargo release [15].

- Light: Light-responsive moieties like spiropyran can be incorporated into polymers, allowing for extremely high spatial and temporal control over drug release [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Micellar Extraction

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Extraction Yield | Surfactant concentration below the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) [13]. | Ensure surfactant concentration is sufficiently above the CMC. Determine CMC via surface tension or conductivity measurements [16]. |

| Incorrect micelle type for the target analyte polarity. | Use normal micelles for hydrophobic compounds in aqueous samples. Use reverse micelles for hydrophilic compounds in non-polar matrices [13]. | |

| Insufficient interaction time for solubilization. | Optimize the incubation/equilibration time during the extraction step. | |

| Formation of Stable Emulsions | Sample contains high amounts of surfactant-like compounds (e.g., phospholipids, proteins) [10]. | - Gently swirl the mixture instead of vigorous shaking [10].- Use supported liquid extraction (SLE) to avoid emulsion formation [10].- Disrupt emulsions by adding brine ("salting out"), centrifugation, or filtration through glass wool [10]. |

| Poor Detection Limits in Analysis | High background interference from the surfactant itself. | Use high-purity surfactants. Employ biosurfactants (e.g., Tea saponin) which can be less interfering than synthetic ones [3]. |

| Inefficient transfer or recovery of analytes from the micellar phase. | Couple micellar extraction with an enrichment step, such as in-situ aqueous two-phase separation, to concentrate analytes before analysis [3]. | |

| Instability of Polymeric Micelles | Operation below the CMC, leading to disassembly. | Use polymeric micelles with an ultra-low CMC to ensure stability upon dilution [13]. |

| Degradation of polymer or incompatible storage conditions. | Understand the polymer's stability profile (e.g., susceptibility to hydrolysis) and store formulations under recommended conditions. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting for Kinetically Frozen vs. Dynamic Polymeric Micelles

| Aspect | Dynamic Micelles (e.g., some Poloxamers) | Kinetically Frozen Micelles (e.g., PS-PEO) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Characteristic | Surfactant-like; exist in equilibrium with unimers [13]. | No equilibrium with unimers; morphologically fixed upon formation [13]. |

| Stability upon Dilution | Can disassemble if diluted below the CMC [13]. | Highly stable against dilution due to frozen state [13]. |

| Common Issue: Drug Leakage | Cause: Constant exchange of unimers can lead to premature release during circulation [13]. | Cause: Typically not due to unimer exchange. Could be related to slow diffusion or matrix degradation. |

| Mitigation Strategy | Design systems with very low CMC or use cross-linking strategies. | The frozen state inherently prevents leakage via disassembly, making them ideal for long-circulating nanocarriers [13]. |

| Morphological Flexibility | Limited to equilibrium shapes (e.g., spheres) [13]. | Can access a vast range of non-equilibrium shapes (e.g., cylinders, vesicles) [13]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

This green and efficient method uses a biosurfactant for extraction and an in-situ formed aqueous two-phase system for enrichment.

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Plant Material: Ginkgo nut powder (or other functional food material).

- Surfactant Solution: Tea saponin solution (1-4% w/v in water).

- Phase Forming Agents: Polyethylene Glycol 6000 (PEG-6000) and Ammonium Sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄).

- Standards: Analytical standards for target compounds (e.g., protocatechuic acid, kaempferol).

2. Equipment:

- Ultrasonic bath

- Centrifuge

- HPLC system with appropriate detector (e.g., UV, MS)

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Weighing. Weigh 0.5 g of Ginkgo nut powder into a suitable tube.

- Step 2: Micellar Extraction. Add a low-concentration tea saponin solution (e.g., 3% w/v) to the powder. Subject the mixture to ultrasound-assisted extraction for a predetermined time (e.g., 20 minutes).

- Step 3: In-Situ Aqueous Two-Phase Formation. To the extract, add PEG-6000 (e.g., 0.6 g) and (NH₄)₂SO₄ (e.g., 1.4 g). Vortex or shake the mixture thoroughly. An aqueous two-phase system will form, typically with the target compounds (flavonoids, lactones) partitioning into the PEG-rich upper phase.

- Step 4: Phase Separation and Analysis. Centrifuge the mixture to facilitate complete phase separation. Collect the upper phase, which contains the enriched analytes. Dilute or reconstitute as necessary for analysis via HPLC-MS/MS.

4. Optimization Notes:

- Key factors to optimize via Response Surface Methodology (RSM) include tea saponin concentration, salt dosage, and ultrasonic extraction time [3].

This protocol outlines the general methodology for creating and testing smart micellar systems.

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Polymers: Amphiphilic block copolymers (e.g., PEG--b--PLA, or polymers with pH-sensitive blocks like poly(l-histidine) or redox-sensitive disulfide bonds in the spacer).

- Drug: A model poorly soluble drug (e.g., Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin).

- Buffers: Buffers at different pH levels (e.g., pH 7.4 to simulate physiological conditions, and pH 5.0-6.0 to simulate tumoral or endosomal environments).

2. Equipment:

- Dialysis tubing

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Micelle Preparation. The micelles are often prepared by a dialysis method. The amphiphilic copolymer and drug are dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., DMSO, acetone). This solution is then dialyzed extensively against water or a buffer. During dialysis, the organic solvent is replaced by water, driving the self-assembly of the polymers into micelles with the drug encapsulated in the hydrophobic core.

- Step 2: Characterization.

- Size and Polydispersity: Measure the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of the micelles using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS).

- Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC): Determine the CMC using a fluorescent probe like pyrene. A shift in the vibronic band intensities of pyrene's emission spectrum indicates its transfer from a aqueous to a hydrophobic environment (the micelle core), allowing for CMC calculation [16].

- Step 3: In-Vitro Drug Release Study. Place the drug-loaded micellar solution in a dialysis bag. Immerse the bag in a release medium (buffer) at the desired pH (e.g., 7.4 and 5.0) and under sink conditions. Agitate the system at a constant temperature. At predetermined time intervals, withdraw samples from the external release medium and analyze the drug concentration using HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy. Replace the medium to maintain sink conditions.

4. Optimization Notes:

- The release profile can be tuned by altering the polymer composition, the block lengths, and the specific stimuli-responsive moiety incorporated.

Visualization of Micellar Systems and Workflows

Micelle Types and Stimuli-Responsive Release

Advanced Micellar Extraction and Enrichment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Micellar System Development and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tea Saponin | A natural, non-ionic biosurfactant for green micellar extraction [3]. | Biodegradable, low toxicity. Used to extract flavonoids and lactones from plant materials. |

| Pluronic (Poloxamer) | Triblock copolymers (PEO-PPO-PEO) forming dynamic micelles [15]. | Used in drug delivery; some mixtures (e.g., L61/F127) can target cancer stem cells. |

| PEG--b--PLA | A common amphiphilic block copolymer for forming polymeric micelles [14]. | PEG is the hydrophilic shell; PLA forms the biodegradable hydrophobic core. Basis for products like Genexol-PM. |

| Poly(l-histidine) | A pH-sensitive polymer used in the core of "intelligent" micelles [15]. | Becomes membrane-destabilizing at low pH (endosomal pH), facilitating drug release. |

| Disulfide-linked Gemini Surfactants | Form redox-responsive micelles for controlled drug release [15]. | Cleaved by intracellular glutathione, triggering micelle destabilization and drug release. |

| Pyrene | A fluorescent probe for determining the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) [16]. | Its fluorescence spectrum changes upon partitioning into the hydrophobic micelle core. |

Scientific FAQs: Surfactant Selection and Mechanism

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which surfactants enhance extraction efficiency?

Surfactants are amphiphilic molecules, meaning they consist of a hydrophobic (water-repelling) tail and a hydrophilic (water-attracting) head. In aqueous solutions, when their concentration exceeds the critical micelle concentration (CMC), they spontaneously self-assemble into colloidal-sized clusters called micelles [17] [18]. The hydrophobic cores of these micelles act as a pseudo-organic phase capable of solubilizing poorly water-soluble (hydrophobic) target compounds, effectively pulling them out of the sample matrix and into the solution [17] [19]. This process reduces surface tension, facilitates cell wall and membrane disruption in plant or microbial tissues, and enhances mass transfer rates, leading to higher extraction yields [20].

Q2: How does the choice between ionic and non-ionic surfactants impact an extraction method?

The selection is critical and depends on the target analyte, sample matrix, and the specific extraction technique employed. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Ionic vs. Non-Ionic Surfactants in Extraction

| Feature | Ionic Surfactants | Non-Ionic Surfactants |

|---|---|---|

| Head Group Charge | Anionic (e.g., SDS, SLES) or Cationic (e.g., CTAB) [20] | No charge (e.g., Tween series, Triton X-114) [20] |

| Primary Extraction Techniques | Micellar Extraction, Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography (MEKC) [20] [21] | Cloud-Point Extraction (CPE), Micellar Extraction [17] |

| Typical Mechanism | Solubilization via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions [20] | Solubilization and temperature-induced phase separation (CPE) [17] |

| Advantages | Effective solubilization; can be tailored for charged analytes [20] | Generally less denaturing; enable Cloud-Point Extraction for easy pre-concentration [20] [17] |

| Disadvantages/Limitations | Cationic surfactants can be more toxic; may interact undesirably with charged biomolecules [20] | Mostly derived from chemical synthesis, raising environmental concerns [3] |

Q3: What are the advantages of using a natural surfactant like tea saponin over synthetic ones?

Tea saponin, a natural non-ionic surfactant derived from Camellia plants, offers several distinct advantages, particularly from a green chemistry perspective [3] [22]:

- Biodegradability and Low Toxicity: It is naturally derived, biodegradable, and environmentally friendly, unlike many persistent synthetic surfactants [3].

- High Performance: Despite its natural origin, it exhibits superior surface activity, including low critical micelle concentration (CMC), good foam stability, and excellent salt and hard water resistance [22].

- Green Extraction Credentials: Its use aligns with the principles of sustainable development, reducing the environmental footprint of the analytical process [3]. Studies have successfully used it for the efficient micellar extraction of flavonoids and lactones from Ginkgo nuts [3] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Extraction Recovery

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Surfactant concentration is below the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC): Below the CMC, micelles do not form, and extraction efficiency is drastically reduced.

- Solution: Ensure the surfactant concentration is well above its documented CMC. For example, the CMC of tea saponin was found to be 0.5 g/L [22].

- Incorrect surfactant type for the target analyte: A surfactant with low affinity for your analyte will not solubilize it effectively.

- Solution: For hydrophobic compounds, select surfactants with larger hydrophobic cores. Consider the potential for electrostatic interactions if using ionic surfactants. Experiment with different surfactant classes.

- Inefficient cell lysis or mass transfer:

Issue 2: Low Pre-concentration Factor in Cloud-Point Extraction

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect cloud-point temperature: The temperature must be adequately above the Cloud-Point Temperature (CPT) to induce complete phase separation.

- Solution: Optimize the incubation temperature. Temperatures 15–20 °C greater than the CPT are often needed for quantitative recovery [17].

- Volume of the surfactant-rich coacervative phase is too large: A large phase volume dilutes the analyte.

Issue 3: Interference with Downstream Analysis

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Surfactant co-elutes or interferes with detection: High surfactant concentrations can foul chromatographic columns or create high background signals in spectroscopic detection.

- Solution:

- Dilute the extract before injection.

- Choose a compatible surfactant: For HPLC-UV, ensure the surfactant has low UV absorbance at the detection wavelength. In MEKC, this is less of an issue as the surfactant is part of the running buffer [21].

- Employ a separation technique that accommodates surfactants, such as Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography (MEKC), where the micellar phase is an integral part of the separation system [21].

- Solution:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tea Saponin-Assisted Micellar Extraction Combined with In-Situ Aqueous Two-Phase Enrichment

This protocol details a green method for extracting and pre-concentrating flavonoids and lactones from functional foods like Ginkgo nuts [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Tea Saponin (≥98% purity) | The core green, natural non-ionic surfactant that forms micelles to solubilize and extract target compounds [3]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol 6000 (PEG-6000) | A polymer used to form an aqueous two-phase system with salts, enabling the enrichment of target analytes from the micellar solution [3]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄) | A salt used to induce phase separation in the aqueous two-phase system, driving targets into one phase [3]. |

| Ultrasonication Bath | Applies ultrasonic energy to assist in disrupting the sample matrix and enhancing extraction efficiency [3]. |

Workflow Diagram: Tea Saponin Extraction & Enrichment

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind the plant material (e.g., Ginkgo nuts) into a fine powder. Accurately weigh 0.5 g of the powder into an extraction vessel [3].

- Micellar Extraction: Add 10 mL of a 2-3% (w/v) aqueous tea saponin solution to the sample. Securely close the vessel and place it in an ultrasonic bath. Extract for 20 minutes at room temperature [3].

- In-Situ Aqueous Two-Phase Formation: Transfer the extract to a centrifuge tube. Add 0.6 g of PEG-6000 and 1.4 g of ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄). Vortex the mixture vigorously until the salts and polymer are completely dissolved [3].

- Phase Separation and Enrichment: Centrifuge the mixture at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes. This will induce the formation of two immiscible aqueous phases: a PEG-rich phase and a salt-rich phase. The target flavonoids and lactones will partition into one of these phases, achieving enrichment [3].

- Collection: Carefully collect the analyte-rich phase using a pipette. The sample is now ready for analysis via techniques like UPLC-MS/MS [3] [4].

Protocol 2: Cloud-Point Extraction (CPE) for Organic Analytes

This is a general protocol for pre-concentrating organic compounds from aqueous solutions using a non-ionic surfactant [17].

Workflow Diagram: Cloud-Point Extraction

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Surfactant Addition: To an aqueous sample (e.g., 10 mL of water), add a non-ionic surfactant like Triton X-114 to a final concentration well above its CMC (e.g., 0.5-2% v/v) [17].

- Analyte Incorporation: Mix the solution thoroughly and allow it to stand for a short period to let the analytes incorporate into the micelles.

- Phase Separation: Place the sample in a water bath and heat it to a temperature 15-20°C above the surfactant's cloud-point (CPT for Triton X-114 is ~25°C, so heat to ~40-45°C) for 20-30 minutes. A cloudy solution will form, leading to the separation of two distinct phases: a small, viscous surfactant-rich phase and a larger aqueous phase [17].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the heated sample at 3000-5000 rpm for 5-15 minutes to accelerate and complete phase separation. Cool the tube in an ice bath or cold water to increase the viscosity of the surfactant-rich phase, making it easier to handle [17].

- Phase Collection: Carefully decant or remove the bulk aqueous phase by pipette. The remaining surfactant-rich phase, containing the pre-concentrated analytes, can be dissolved in a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol or the mobile phase) for subsequent chromatographic analysis [17] [19].

Quantitative Data for Surfactant Selection

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Select Surfactants

| Surfactant | Type | Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | Key Performance Metrics | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tea Saponin | Natural Non-ionic | 0.5 g/L (at 30°C) [22] | Low surface tension: 39.61 mN/m; Excellent foam stability (half-life 2350 s) [22] | Biodegradable; effective for bioactive compounds from plants [3]. |

| Triton X-114 | Synthetic Non-ionic | ~0.2 mM [17] | Cloud-Point Temperature: ~25°C [17] | Ideal for CPE due to low CPT; requires careful temperature control [17]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Synthetic Anionic | ~8.2 mM [20] | High solubilizing power for hydrophobic compounds [20]. | Common in MEKC; can interfere with MS detection; not suitable for CPE [20] [21]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Micellar Extraction Methods

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers working to improve detection limits in micellar extraction methods. The content focuses on resolving specific, experimentally-observed issues related to the core physicochemical interactions in these systems.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my micellar extraction efficiency lower than expected for my target analyte?

Observed Problem: Poor recovery of the analyte during Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) or other micellar extraction techniques.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incorrect Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC). If the surfactant concentration is not sufficiently above the CMC, micelles will not form properly, leading to poor solubilization of the analyte [23].

- Cause 2: Mismatch between Analyte Hydrophobicity and Micelle Core. Highly hydrophobic analytes require a suitably hydrophobic micellar core for effective encapsulation via hydrophobic interactions [16] [15].

- Cause 3: Unfavorable Electrostatic Interactions. Repulsive forces between the micelle surface and the analyte can prevent encapsulation.

- Solution: Manipulate the charge of the micelle and the analyte. Use cationic surfactants (e.g., CTAB) for neutral or anionic analytes, and anionic surfactants (e.g., SDS) for neutral or cationic analytes [25]. Adjusting the solution pH to neutralize the analyte's charge can also enhance incorporation [15].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the selectivity of my micellar extraction to reduce matrix interference?

Observed Problem: Co-extraction of interfering compounds from complex sample matrices, leading to high background noise.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Lack of Selective Binding Interactions. Reliance solely on hydrophobic interactions, which are non-specific.

- Solution: Engineer specific hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions. Use hydrotropes or additives with specific functional groups. For instance, the position of a hydroxyl group on a sodium benzoate derivative can dramatically alter its interaction with a cationic surfactant (e.g., R16HTAB), enabling selective viscosity changes and extraction behaviors [25].

- Cause 2: Suboptimal Cloud Point Extraction Conditions. The temperature, time, and centrifugation steps are critical for clean phase separation [23] [19].

- Solution: Systematically optimize the equilibration temperature and time. Ensure slow heating above the cloud point temperature and sufficient centrifugation time to achieve a compact, surfactant-rich phase. Adding salts (e.g., NaCl, Na₂SO₄) can promote salting-out and improve phase separation [23] [26].

FAQ 3: Why is my micellar system unstable or precipitating during the experiment?

Observed Problem: Solution becomes turbid, or a precipitate forms, leading to loss of the micellar carrier and analyte.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Instability of Wormlike Micelles (WLMs). Long, flexible WLMs, which are highly effective for solubilization, can be sensitive to counterion structure and concentration [25].

- Solution: If using cationic WLMs, carefully select the structure and concentration of aromatic counterions (e.g., salicylate vs. hydroxybenzoate). Small changes in substituent position on the counterion's benzene ring can drastically alter micellar length, flexibility, and stability [25].

- Cause 2: Compromised Micellar Integrity. Extreme pH, high ionic strength, or organic solvents can disrupt micelle structure.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) via Electrical Conductivity

This protocol is fundamental for characterizing any micellar system and ensuring surfactant concentration is optimal for extraction [16] [24].

- Principle: The mobility of ions changes upon micelle formation, causing a distinct change in the slope of a conductivity vs. concentration plot.

- Materials:

- Surfactant stock solution of known concentration.

- Deionized water (specific conductance < 1 µS·cm⁻¹).

- Thermostatted water bath.

- Calibrated digital conductivity meter with a platinized electrode cell.

- Volumetric flasks or beakers for serial dilution.

- Step-by-Step Method:

- Calibrate the conductivity meter with a standard 0.01 M KCl solution.

- Prepare a series of surfactant solutions (at least 10-15) with concentrations spanning a range below and above the suspected CMC.

- Place each solution in a thermostatted water bath to maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 298 K).

- Immerse the clean, dry electrode into each solution and record the specific conductivity once the reading stabilizes.

- Plot the specific conductivity (κ) against the surfactant concentration.

- Identify the CMC as the intersection point of the two linear regressions fitted to the data points below and above the breakpoint.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If the breakpoint is not sharp, it may indicate impurities in the surfactant or the presence of premicellar aggregates. Purify the surfactant and ensure the temperature is rigorously controlled.

Protocol 2: Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) for Analyte Pre-concentration

This protocol is a direct application for improving detection limits by concentrating analytes from a large volume of aqueous sample into a small surfactant-rich phase [23] [19].

- Principle: A non-ionic surfactant solution becomes turbid when heated above its cloud point temperature, separating into a surfactant-rich phase and an aqueous phase, thereby concentrating hydrophobic analytes.

- Materials:

- Non-ionic surfactant (e.g., Triton X-114).

- Sample solution containing the target analyte(s).

- Thermostatted water bath or heating block.

- Centrifuge.

- Micropipettes.

- Salting-out agent (e.g., NaCl, if required).

- Step-by-Step Method:

- To a known volume of the aqueous sample, add a specific amount of surfactant (e.g., 1-5% w/v Triton X-114) and a salting-out agent if needed.

- Mix the solution thoroughly and incubate in a water bath at a temperature 15-20°C above the cloud point of the surfactant for a fixed time (e.g., 10-20 min) to achieve complete phase separation.

- Centrifuge the mixture at a moderate speed (e.g., 3000 rpm for 5-10 min) to compact the viscous surfactant-rich phase.

- Carefully separate the two phases. The small volume surfactant-rich phase (often at the bottom of the tube) now contains the pre-concentrated analytes.

- Dilute the surfactant-rich phase with a compatible solvent (e.g., methanol or water) if necessary, prior to instrumental analysis (e.g., HPLC, GC).

- Troubleshooting Tip: If the volume of the surfactant-rich phase is too large, optimize the concentration of the salting-out agent, which can dehydrate the micelles and reduce the volume of the coacervate phase [26].

Table 1: Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of Surfactants in Drug Solutions at 298 K [24]

| Surface-Active Ionic Liquid (SAIL) | CMC in Water (mol·kg⁻¹) | CMC in 0.05 mol·kg⁻¹ Aspirin (mol·kg⁻¹) | Key Interaction with Drug |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2-HEA][Ole] | 0.24 | 0.16 | Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bonding |

| [BHEA][Ole] | 0.20 | 0.12 | Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bonding |

| [THEA][Ole] | 0.16 | 0.09 | Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bonding |

Table 2: Effect of Hydrotrope Isomer on Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) of Wormlike Micelles [25] (System: 40 mM R16HTAB + 40 mM Benzoate Derivative)

| Hydrotrope (Sodium Salt of) | Substituent Position | Zero-Shear Viscosity, η₀ (Pa·s) | Primary Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxybenzoate | Ortho (SoHB) | 645.16 | Hydrogen Bonding, Hydrophobic Insertion |

| Hydroxybenzoate | Meta (SmHB) | 5.99 | Moderate Hydrogen Bonding |

| Hydroxybenzoate | Para (SpHB) | 0.119 | Weak Electrostatic |

| Methylbenzoate | Para (SpMB) | 15.92 | Steric/Hydrophobic |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Micellar Extraction Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Ionic Surfactants (Triton X-114) | Forms micelles for Cloud Point Extraction; hydrophobic core enables analyte solubilization via hydrophobic interactions [23] [19]. | Primary extractant for pre-concentrating organic pollutants from water samples [19]. |

| Cationic Surfactants (CTAB, R16HTAB) | Forms positively charged micelles; structure allows growth into wormlike micelles (WLMs) with additives, enhancing viscosity and solubilization capacity [25]. | Host surfactant for constructing viscoelastic WLMs with sodium salicylate for analytical and material applications [25]. |

| Aromatic Hydrotropes (Sodium Salicylate, Benzoate Derivatives) | Binds to cationic micelle surfaces; alters the packing parameter to induce micellar growth into rods or worms via electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions [25]. | Additive to transform spherical CTAB or R16HTAB micelles into long, entangled WLMs, dramatically increasing solution viscosity [25]. |

| Surface-Active Ionic Liquids (SAILs) | Tunable surfactants with low CMC; functional groups (e.g., -OH) can engage in specific hydrogen bonding with target drug molecules, improving solubility and bioavailability [24]. | Solubilizing agent for poorly water-soluble drugs like aspirin; the CMC decreases in the drug's presence, indicating strong interactions [24]. |

| Salting-Out Agents (NaCl, Na₂SO₄) | Electrolytes that reduce the solubility of surfactants in water, promoting phase separation in CPE; can also screen headgroup repulsions, affecting micelle size and shape [25] [26]. | Used to optimize the phase separation time and volume of the surfactant-rich phase in Cloud Point Extraction protocols [26]. |

Experimental Workflow and Interaction Diagrams

Micellar Extraction Workflow

Analyte-Micelle Interaction Mechanisms

Advanced Micellar Workflows: From Cloud Point to Combined Microextraction Techniques

Cloud-point extraction (CPE) represents a green, efficient methodology for preconcentrating analytes from complex matrices prior to analysis. As a micelle-mediated separation technique, CPE leverages the unique property of non-ionic surfactants in aqueous solution to form micelles that undergo phase separation when heated above a specific temperature known as the cloud point temperature (Tc) [27] [17]. This process results in two distinct phases: a surfactant-rich coacervate phase containing the preconcentrated analytes and a diluted aqueous phase [17] [28]. The technique was first introduced in 1976 by Watanabe and colleagues for metal extraction and has since evolved to encompass diverse applications including nanoparticle enrichment, drug analysis, and environmental pollutant detection [27] [28].

Within the context of thesis research focused on improving detection limits in micellar extraction methods, CPE offers significant advantages over traditional liquid-liquid extraction. The procedure is rapid, inexpensive, precise, and minimizes consumption of toxic organic solvents, aligning with green chemistry principles [29] [28]. For researchers and drug development professionals, CPE provides a valuable tool for enhancing analytical sensitivity while simplifying sample preparation workflows across various sample types including biological fluids, environmental waters, and pharmaceutical formulations.

Technical Foundations: Mechanisms and Reagents

Mechanism of Phase Separation

The fundamental mechanism driving CPE involves temperature-induced dehydration of non-ionic surfactant micelles. Below the cloud point temperature, surfactant molecules exist as monomers or small aggregates in aqueous solution. As the temperature increases above Tc, the dielectric constant of water decreases, reducing interactions between water molecules and the hydrophilic chains of the surfactant [27]. This breakdown of hydrogen bonds causes surfactant micelles to become increasingly hydrophobic, eventually leading to visible phase separation characterized by solution clouding [27].

The phase separation process occurs through several stages. Initially, surfactant molecules self-assemble into spherical micelles with hydrophobic cores and hydrophilic exteriors when their concentration exceeds the critical micelle concentration (CMC) [17]. Upon heating above Tc, intermicellar attractions intensify, prompting micelle aggregation and growth. This leads to the formation of a surfactant-rich coacervate phase that separates from the bulk aqueous phase, either as an upper or lower layer depending on surfactant density [27] [17]. Hydrophobic analytes or appropriately complexed species partition into the surfactant-rich phase, achieving significant preconcentration factors [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CPE requires careful selection of surfactants and auxiliary reagents tailored to specific analytical targets. The table below summarizes essential reagents and their functions in CPE protocols:

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Cloud-Point Extraction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in CPE | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ionic Surfactants | Triton X-114 (Tc = 25°C), Triton X-100 (Tc = 66°C), Brij 30 (Tc = 2°C), Brij 35 (Tc > 100°C), Tween 80 (Tc = 65°C) [17] | Forms micelles that encapsulate hydrophobic analytes; undergoes temperature-induced phase separation | Selection depends on desired cloud point; Triton X-114 popular for room-temperature separation |

| Chelating Agents | Dithizone, 1-(2-Thiazolylazo)-2-naphthol (TAN), 8-Hydroxyquinoline [28] [30] | Converts hydrophilic metal ions into hydrophobic complexes for extraction | Essential for metal ion preconcentration; must form stable, hydrophobic complexes |

| Salt Additives | Sodium sulfate, ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride [28] | Salting-out effect enhances phase separation efficiency; modifies cloud point temperature | Concentration optimization required to avoid excessive viscosity |

| pH Adjusters | Acetate buffer, phosphate buffer, sulfuric acid, sodium hydroxide [27] [30] | Optimizes chelation efficiency and analyte speciation | Critical for metal complex stability and extraction yield |

| Viscosity Reducers | Ethanol, methanol, acetonitrile [30] | Reduces viscosity of surfactant-rich phase for easier handling | Facilitates subsequent analytical measurements |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Standard CPE Workflow for Metal Ion Preconcentration

The following protocol details the CPE procedure for cadmium determination using electroanalytical detection, adaptable for other metal ions with appropriate chelating agents [30]:

Sample Preparation: Transfer 25 mL of aqueous sample containing target analytes (e.g., 0.04–4.0 μM Cd2+) to a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

Complexation and Surfactant Addition:

- Add appropriate complexing agents (e.g., 1 mL of 1 M KI and 0.5 mL of 1 M H2SO4 for Cd2+ to form extractable ion pairs) [30].

- Add surfactant solution (e.g., 1 mL of 10% w/w Triton X-114, pre-warmed to 60°C to reduce viscosity) [30].

- Adjust pH if necessary using buffer solutions.

- Dilute to 25 mL with deionized water and vortex for 10-30 seconds until homogeneous.

Incubation and Phase Separation:

- Place tubes in a water bath at 55°C for 30-45 minutes until clear phase separation is visible [30].

- Centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 12 minutes to enhance phase separation.

- Cool in an ice bath for 5 minutes to increase surfactant-rich phase viscosity.

Phase Collection:

- Carefully decant or remove the aqueous phase.

- The remaining surfactant-rich phase (typically 0.5-1 mL) contains preconcentrated analytes.

Analysis Preparation:

- For electrochemical analysis: Add 2.5 mL ethanol and 3.5 mL pH 4.65 acetate buffer to the surfactant-rich phase (final volume ~6.5 mL) to reduce viscosity and provide appropriate electrolyte [30].

- For spectroscopic techniques: Dilute with appropriate solvents compatible with the detection method.

This protocol typically achieves enrichment factors of 20-100x, significantly lowering detection limits for trace analysis [30].

CPE Workflow for Nanoparticle Enrichment

For nanoparticle (NP) enrichment from environmental matrices, Hartmann and colleagues developed this optimized protocol [27]:

Sample Treatment: Mix 40 mL of NP-containing aqueous sample with:

- 1.0 mL saturated ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt solution

- 400 μL of 1 M sodium acetate

- 100 μL of 1.25 M acetic acid

- 1 mL of 10% (w/w) Triton X-114

Incubation: Heat at 40°C for 30 minutes to achieve phase separation.

Centrifugation: Centrifuge for 12 minutes at 4427 g to enhance phase separation.

Cooling: Cool samples in an ice bath for 5 minutes to increase phase separation efficiency.

Analysis: Remove aqueous supernatant by decanting. Dissolve the surfactant-rich phase containing enriched NPs in 100 μL ethanol for subsequent analysis techniques such as electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry (ET-AAS) or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [27].

This method has demonstrated extraction efficiencies ranging from 52% for 150 nm AuNPs to 101% for 2 nm AuNPs, highlighting the size-dependent nature of CPE efficiency for nanomaterials [27].

CPE Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: CPE Experimental Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 2: CPE Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| No phase separation observed | Surfactant concentration below CMC, Temperature below cloud point, Inappropriate surfactant selection | Verify surfactant concentration exceeds CMC, Increase temperature 15-20°C above stated Tc, Select surfactant with appropriate Tc for application [17] | Pre-determine CMC and Tc for specific surfactant lot, Use temperature-controlled water bath |

| Low extraction efficiency | Incomplete complexation, Incorrect pH, Surfactant-analyte incompatibility | Optimize chelating agent concentration, Adjust pH for optimal complex formation, Test different surfactant types [28] | Perform extraction yield experiments with standard solutions, Validate method with known concentrations |

| High viscosity in surfactant-rich phase | Excessive surfactant concentration, Inadequate salt content, Temperature too low during collection | Dilute surfactant concentration, Add salt modifiers to improve separation, Maintain elevated temperature during phase collection [30] | Optimize surfactant:analyte ratio, Add ethanol to reduce viscosity post-extraction [30] |

| Poor analytical reproducibility | Inconsistent temperature control, Variable centrifugation parameters, Incomplete mixing | Standardize incubation time and temperature, Control centrifugation speed and time, Implement consistent mixing protocols [27] [30] | Implement standard operating procedures, Use calibrated equipment |

| Matrix interference | Competing complexation, Surface-active matrix components, High ionic strength | Add masking agents, Implement pre-extraction clean-up, Dilute sample to reduce interference [27] | Characterize matrix effects during method development, Use standard addition for quantification |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of CPE over traditional liquid-liquid extraction?

CPE offers multiple advantages including minimal use of toxic organic solvents, lower cost, higher preconcentration factors, safety (non-flammable reagents), and simplicity (requires basic laboratory equipment) [29] [28]. The technique provides quantitative recovery for many analytes with extraction efficiencies often exceeding 90% while maintaining the chemical integrity of target species [27] [28].

Q2: How does temperature affect the cloud point extraction process?

Temperature is the critical parameter in CPE. Below the cloud point temperature (Tc), the surfactant solution remains homogeneous. Heating above Tc induces dehydration of the surfactant's hydrophilic groups, reducing solubility and causing phase separation [27] [17]. Most protocols recommend operating 15-20°C above the stated Tc to ensure complete and efficient phase separation [17].

Q3: Can CPE be applied to hydrophilic analytes?

Yes, hydrophilic analytes including metal ions can be extracted via CPE after conversion to hydrophobic complexes using appropriate chelating agents [28] [30]. For instance, cadmium can be extracted using iodide and sulfuric acid to form an extractable ion pair [30], while other metals may require specific chelating agents like dithizone or 8-hydroxyquinoline [28].

Q4: What factors influence the selection of surfactant for CPE applications?

Surfactant selection depends on several factors including cloud point temperature (should be above but close to ambient for energy efficiency), compatibility with analytical detection methods, cost, and environmental considerations [17]. Triton X-114 is widely used due to its low cloud point (22-25°C) and well-characterized extraction properties [27] [30].

Q5: How can I improve the selectivity of CPE for specific analytes?

Selectivity can be enhanced through pH adjustment, use of selective chelating agents, incorporation of masking agents to interfere with competing species, and optimization of incubation conditions [28]. For complex matrices, sequential extraction protocols or combination with other separation techniques may be necessary [27].

Q6: What are typical preconcentration factors achievable with CPE?

Preconcentration factors vary depending on the phase volume ratio but typically range from 10 to 100-fold [27] [30]. For example, CPE protocols for AuNPs and AgNPs achieve enrichment factors of approximately 80 from initial 40-mL samples concentrated to 0.5 mL [27], while methods for cadmium detection demonstrate 20-fold improvement in detection limits [30].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 3: CPE Performance Metrics for Various Analytes

| Analyte | Matrix | Surfactant | Extraction Efficiency | Enrichment Factor | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs (2 nm) | Aqueous samples | Triton X-114 | 101% | 80 | TEM/ET-AAS [27] |

| AuNPs (150 nm) | Aqueous samples | Triton X-114 | 52% | 80 | TEM/ET-AAS [27] |

| Cd2+ | Water samples | Triton X-114 | >90% | 20 | ASV [30] |

| CuO NPs | Aqueous samples | Triton X-114 | ~90% | 100 | Spectrometry [27] |

| ZnO NPs | Aqueous samples | Triton X-114 | 64-123% | 220 | Spectrometry [27] |

| Ag, Au, Fe3O4 NPs | Environmental matrices | Triton X-114 | 74-114% | Variable | Sequential analysis [27] |

| Triazine herbicides | Milk | Triton X-100 | 70.5-96.9% | Not specified | HPLC-UV [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in Reverse Micellar Extraction, along with their specific functions in the process.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Reverse Micellar Extraction |

|---|---|

| Surfactants (e.g., AOT) | Forms the structure of reverse micelles; the polar head groups create a hydrophilic core to encapsulate biomolecules. [31] |

| Organic Solvent (e.g., Isooctane) | Forms the bulk continuous phase in which the reverse micelles are dispersed. [31] |

| Counterionic Surfactants (e.g., TOMAC, DTAB) | Facilitates backward extraction by interacting with the primary surfactant, causing micelle collapse and releasing the encapsulated protein. [32] |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., KCl) | Used to adjust ionic strength, which influences the electrostatic interactions critical for extraction efficiency. [31] |

| Buffers (e.g., Phosphate Buffer) | Used to maintain specific pH levels during the forward and backward extraction steps, controlling protein charge and solubility. [31] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard RME Workflow for Protein Extraction

The diagram below illustrates the two key stages of Reverse Micellar Extraction.

Protocol: Hempseed Protein Isolation via RME [31]

This protocol is adapted from a recent study on extracting hempseed protein isolates (HPI).

1. Forward Extraction (Transfer from aqueous feed to organic micellar phase)

- Reverse Micelle Preparation: Prepare a solution of the anionic surfactant AOT (Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate sodium salt) in isooctane at a concentration of 0.09 g/mL. Add 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.54) containing 0.05 M KCl to the AOT/isooctane solution at a volume ratio of 0.106 mL/mL.

- Ultrasonication: Subject the mixture to ultrasonic treatment at 30°C for 30 minutes. Incubate overnight to form a clear, transparent reverse micelle solution.

- Extraction: Mix the defatted protein source (e.g., hempseed meal) with the reverse micelle solution at a ratio of 1:15 (w/v). Stir the mixture at 150 rpm for 80 minutes at 50°C.

- Separation: Centrifuge the mixture. The protein-loaded reverse micelles will be contained in the separated organic phase.

2. Backward Extraction (Transfer from organic phase to aqueous stripping solution)

- Counterionic Surfactant Method: Add a counterionic surfactant (e.g., the cationic TOMAC) to the protein-loaded organic phase. This disrupts the micelle structure via electrostatic interaction.

- Phase Separation: The protein is released and transfers into a fresh aqueous stripping solution. This process is very fast and yields a protein solution with near-neutral pH and low salt concentration.

- Recovery: Separate the aqueous phase containing the purified, encapsulated protein.

Advanced Backward Extraction Protocol

The following workflow details the enhanced back-extraction method using a counterionic surfactant.

Protocol: Enhanced Back-Extraction with Counterionic Surfactant [32]

This method offers significant advantages over conventional high-salt/high-pH back-extraction.

- Procedure: After forward extraction, add a counterionic surfactant (e.g., TOMAC or DTAB) directly to the organic phase containing the protein-encapsulated reverse micelles.

- Mechanism: The oppositely charged surfactant molecules interact electrostatically, forming hydrophobic complexes (e.g., a 1:1 AOT-TOMAC complex). This disrupts the micellar structure, causing it to collapse and release the encapsulated protein into a fresh aqueous stripping solution.

- Advantages:

- Speed: The process is very fast—over 100 times faster than conventional back-extraction and 3 times faster than forward extraction.

- Protein Activity: Maintains protein activity as the resulting aqueous phase has a near-neutral pH and low salt concentration.

- Solvent Reuse: The surfactant complexes can be removed by adsorption onto materials like Montmorillonite, allowing the organic solvent to be recycled.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Extraction Efficiency

This table addresses common issues related to poor recovery of the target biomolecule.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Forward Transfer | Incorrect pH, leading to weak electrostatic attraction. | Adjust the pH of the aqueous feed to ensure the protein charge is opposite to the surfactant head group. [33] |

| Ionic strength too high, shielding electrostatic interactions. | Reduce the salt concentration (e.g., KCl) in the aqueous feed. [33] | |

| Surfactant concentration too low. | Increase the surfactant concentration above the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) to ensure sufficient micelles are present. [33] | |

| Low Backward Transfer | Inefficient micelle disruption with conventional methods. | Switch to a counterionic surfactant for back-extraction. Adding TOMAC or DTAB can significantly improve yield. [32] |

| Entrapment in surfactant complex. | For counterionic methods, adsorb the formed surfactant complexes (e.g., AOT-TOMAC) onto Montmorillonite to remove them from the organic phase. [32] |

Protein Activity & Sample Quality

This table focuses on problems that affect the integrity and function of the purified biomolecule.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of Protein Activity | Harsh pH conditions during extraction. | Use the counterionic surfactant back-extraction method, which maintains a near-neutral pH in the stripping solution, preserving activity. [32] |

| Poor Color or Co-extraction of Impurities | Co-extraction of pigments, polyphenols, or lipids. | The RME method itself can improve product color. Ensure the protein source is properly defatted prior to extraction. [31] |

| Protein Denaturation | Aggregation at the isoelectric point or interface. | RME is known to help maintain native protein conformation. Optimize contact time and avoid excessive shear stress. [31] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Reverse Micellar Extraction improve detection limits in analytical research?

RME serves as a highly efficient pre-concentration step. By extracting a target analyte from a large volume of a complex matrix (like plasma) into a much smaller volume of organic solvent or a clean aqueous solution, it significantly increases the analyte concentration. This enriched sample then allows for more sensitive detection and quantification by analytical instruments like HPLC, effectively lowering the method's detection limit. [34]

Q2: Why is my protein not transferring back into the fresh aqueous solution during back-extraction?

The most common reason is insufficient disruption of the reverse micelles. The electrostatic forces holding the micelle together and encapsulating the protein are strong. Instead of relying only on high salt concentrations, introduce a counterionic surfactant. This surfactant, with a charge opposite to that of the primary one, will interact with it, destabilizing the micelle structure and forcing the release of its contents, thereby enabling a much more efficient back-transfer. [32]

Q3: What are the key advantages of RME over traditional methods like alkaline extraction-isoelectric precipitation?

RME offers several key advantages for biomolecule purification, especially when high-quality, functional products are desired. As demonstrated in a study on hempseed protein, RME can:

- Preserve Native Structure: Proteins extracted via RME can remain in their natural state, unlike those subjected to harsh alkaline conditions which can cause dissociation. [31]

- Improve Functionality: RME-extracted proteins can demonstrate higher solubility, foaming ability, and emulsification ability. [31]

- Enhance Product Quality: The process can result in a whiter protein color and a better nutritional profile (e.g., superior amino acid composition). [31]

- Environmental Benefits: It reduces or eliminates the need for strong acids and alkalis, minimizing waste and allowing for solvent recycling. [32] [31]

Q4: Can RME be applied to molecules other than proteins?

Yes, the principle of RME is versatile. While excellent for proteins, it has been successfully adapted for the extraction and pre-concentration of various small molecules, including pharmaceutical drugs like antidepressants from plasma and organic dyes from wastewater. [34] [33] The core requirement is that the target molecule can be solubilized within the micelle's core or at its interface.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Tea Saponin-Assisted Micellar Extraction (ME) Combined with In-Situ Aqueous Two-Phase Enrichment

This protocol outlines a green and efficient method for the extraction of active compounds from plant matrices, utilizing tea saponin as a natural biosurfactant to form micelles, followed by enrichment via an in-situ formed aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) [3].

Materials:

- Biosurfactant: Tea saponin (purity ≥98%)

- Phase Formers: Polyethylene Glycol 6000 (PEG-6000) and Ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄)

- Sample: Ginkgo nut powder (or other plant material of interest)

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, centrifuge, analytical balance

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 0.5 g of the target plant matrix powder (e.g., Ginkgo nut).

- Micellar Extraction: Add a low-concentration tea saponin solution (optimally 3% w/v) to the powder. The volume should be sufficient to submerge the material.

- Ultrasonic Assistance: Subject the mixture to ultrasound for a defined period (optimally 20 minutes) to enhance extraction efficiency.

- ATPS Formation: To the extracted mixture, add 0.6 g of PEG-6000 and 1.4 g of (NH₄)₂SO₄. Vortex vigorously to dissolve the salts and form the in-situ aqueous two-phase system.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture to accelerate phase separation.

- Collection: The target analytes (e.g., flavonoids and lactones) will partition into the upper PEG-rich phase. Carefully collect this phase for subsequent analysis [3].

Ionic Liquid-Based Vortex-Assisted Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME)

This protocol describes a method for the extraction of trace organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) from fruit samples using an ionic liquid as the extraction solvent and vortex mixing for dispersion [35].

Materials:

- Extraction Solvent: 1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([C₈MIM][PF₆])

- Disperser Solvent: Acetonitrile

- Sample: Homogenized apple or pear tissue

- Chemicals: Sodium chloride (NaCl)

- Equipment: Vortex mixer, centrifuge, HPLC system for analysis

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the fruit sample (apple or pear). A representative portion should be weighed or a liquid extract prepared.

- DLLME Setup: To the sample or sample extract, add a mixture containing 347 µL of chloroform (extraction solvent) and 1614 µL of acetonitrile (disperser solvent). Note: While the original method uses [C₈MIM][PF₆] as the extraction solvent, optimal volume ratios were defined using the chloroform/acetonitrile system [36].

- Vortex Mixing: Vigorously mix the solution using a vortex mixer. This creates a fine dispersion of the extraction solvent throughout the aqueous sample, creating a large surface area for analyte transfer.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture to break the emulsion and sediment the dense extraction solvent (ionic liquid or chloroform) phase at the bottom of the tube.

- Collection: The sedimented droplet, now enriched with the target OPPs, is collected with a micro-syringe.

- Analysis: The extract is diluted if necessary and injected into an HPLC or UPLC-MS/MS system for quantification. This method can achieve enrichment factors greater than 300 [35].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is the recovery of my target analytes low after the ME-ATPS step?

- Possible Cause: The concentration of the biosurfactant (e.g., tea saponin) is suboptimal for efficiently solubilizing the target compounds.

Solution: Systematically optimize the surfactant concentration. Test a range (e.g., 1-4%) to find the critical micelle concentration (CMC) that provides the best yield, as this plays a pivotal role in micelle formation and solubilization capacity [23] [3].

Possible Cause: The salt concentration in the ATPS is not optimal, leading to inefficient phase separation and partitioning of analytes.

- Solution: Re-optimize the mass of salt (e.g., (NH₄)₂SO₄) added. An insufficient amount may not induce proper phase separation, while an excess can alter the partition coefficient of your analytes [3].

FAQ 2: The sedimented droplet is difficult to locate or retrieve after Vortex-Assisted DLLME. What can I do?

- Possible Cause: The volume of the extraction solvent is too small.

Solution: Ensure the extraction solvent volume is precisely measured and appropriate for the sample volume. Using a conical-bottom centrifuge tube can help collect the droplet more easily [36].

Possible Cause: The dispersion is too stable, and the emulsion does not break completely during centrifugation.

- Solution: Increase the centrifugation time or speed. Alternatively, the addition of a small amount of salt (NaCl) can promote the breaking of the emulsion by salting out the organic phase [36] [35].

FAQ 3: Can I use any Ionic Liquid for pesticide extraction?

- Answer: No, the structure of the ionic liquid significantly impacts its extraction efficiency. The hydrophobicity of the cation (e.g., the length of the alkyl chain in imidazolium-based ILs) and the nature of the anion must be tailored to the target pesticides. For OPPs in fruit, [C₈MIM][PF₆] has been shown to be an effective extraction solvent, but others may be more suitable for different compound classes [37] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents used in the described hybrid extraction methods and their primary functions.

Table 1: Key Reagent Solutions for Hybrid Extraction Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tea Saponin [3] | Natural, non-ionic biosurfactant for micelle formation. | Amphiphilic structure, low toxicity, biodegradable, superior surface activity. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [C₈MIM][PF₆]) [37] [35] | "Designer solvent" for extraction in DLLME; can be tuned for specific analytes. | Low vapor pressure, high thermal stability, tunable solubility, and selectivity. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [3] | Polymer used to form the polymer-rich phase in an aqueous two-phase system (ATPS). | Water-soluble, non-toxic, used for partitioning and enriching compounds. |

| Ammonium Sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄) [3] | Salt used to induce phase separation in ATPS via the "salting-out" effect. | Alters the partition coefficient of analytes, driving them into the PEG phase. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Hybrid ME and IL-DLLME workflow.

What is Micellar-Enhanced Ultrafiltration (MEUF)?

Micellar-Enhanced Ultrafiltration (MEUF) is an advanced separation process that combines the use of surfactant molecules with ultrafiltration membrane technology to remove trace organic and inorganic contaminants from water and wastewater [38]. In this process, surfactant is added to the contaminated aqueous stream at a concentration higher than its Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC), forming large aggregates called micelles [38] [39]. These micelles solubilize organic pollutants and bind metal ions through electrostatic interactions, creating larger complexes that can be effectively rejected by ultrafiltration membranes with larger pore sizes than would otherwise be required [38].

How does MEUF improve detection limits in micellar extraction methods research?