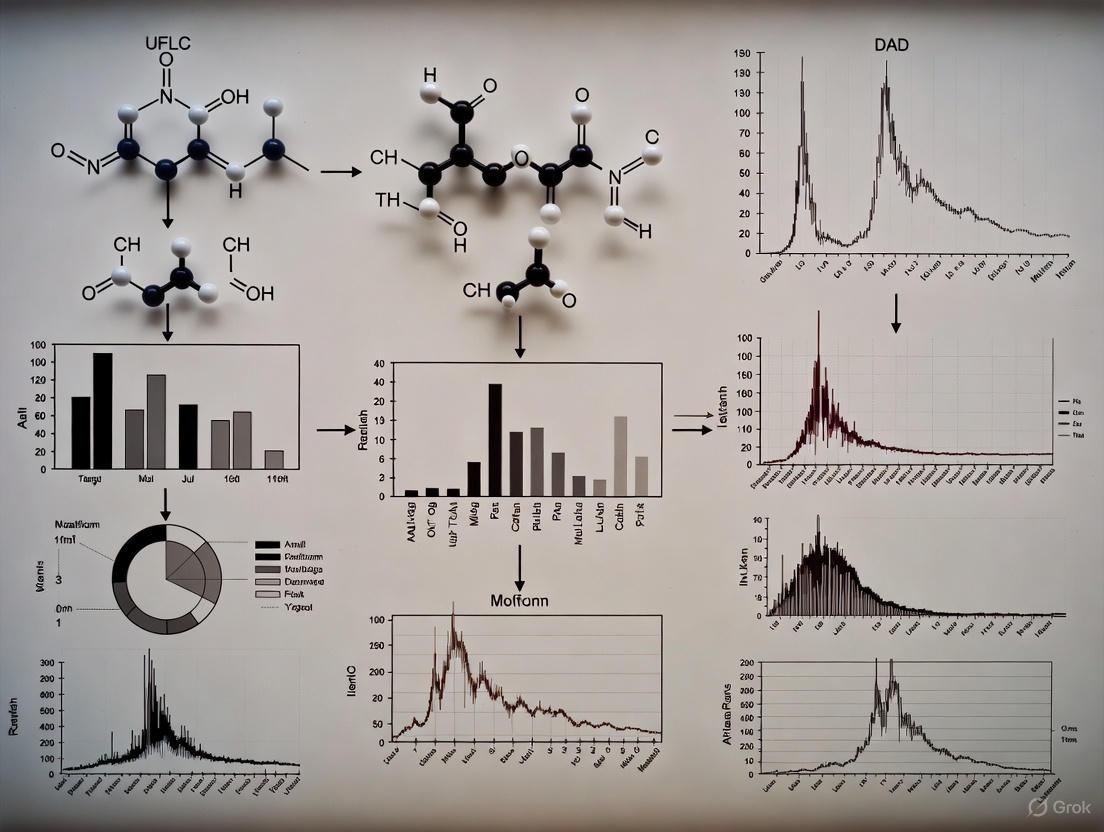

Advanced Strategies to Improve Peak Resolution and Shape in UFLC-DAD: A Comprehensive Guide for Bioanalytical Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (UFLC-DAD) methods.

Advanced Strategies to Improve Peak Resolution and Shape in UFLC-DAD: A Comprehensive Guide for Bioanalytical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (UFLC-DAD) methods. It covers foundational principles of chromatographic resolution and peak shape, advanced methodological approaches for complex samples, systematic troubleshooting for common issues like peak tailing and co-elution, and rigorous validation techniques to ensure method robustness. By integrating the latest chromatographic theories, practical optimization strategies, and validation protocols, this guide serves as an essential resource for enhancing data quality, accuracy, and reliability in pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis.

Understanding Peak Resolution and Shape Fundamentals in UFLC-DAD

Chromatographic resolution (Rs) quantitatively describes the separation between two analyte peaks. The fundamental resolution equation is:

Rs = (√N/4) * [(α - 1)/α] * [k/(1 + k)]

This equation consists of three distinct terms representing the primary factors a chromatographer can control to improve a separation [1] [2]:

- Efficiency (N): The first term (√N/4) describes the peak sharpness or "theoretical plates" of the column.

- Selectivity (α): The second term [(α - 1)/α] describes the ability of the system to chemically distinguish between two components.

- Retention (k): The third term [k/(1 + k)] describes how long a compound is retained on the column relative to an unretained compound.

Understanding and optimizing these three parameters is essential for improving peak resolution and shape in Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (UFLC-DAD) research, directly impacting the quality and reliability of data in drug development.

The Efficiency Factor (N)

Definition and Role in Resolution

Column efficiency, expressed as the number of theoretical plates (N), is a measure of peak broadening. A higher N value produces narrower peaks, which reduces the chance of two peaks co-eluting. The efficiency is calculated from the chromatogram using the equation N = 16 * (tR / wb)^2, where tR is the retention time and wb is the peak width at the base [2]. In the resolution equation, efficiency is the least efficient factor to improve; doubling the column length (and thus N) only increases resolution by a factor of 1.41 [2].

Troubleshooting Guide for Poor Efficiency

A drop in efficiency manifests as broader than expected peaks.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| All peaks are broader than expected | Extra-column volume too large [3] | Use shorter, narrower internal diameter (i.d.) connection capillaries. For UHPLC, use 0.13 mm i.d.; for HPLC, use 0.18 mm i.d. [3]. |

| Detector settings sub-optimal [3] | Ensure detector response time is < 1/4 of the narrowest peak's width. Use a high data acquisition rate (≥ 10 points across a peak) [3] [4]. | |

| Column degradation or voiding [3] | Replace the column. Flush the column with a strong solvent. For prevention, avoid pressure shocks and operate within pH specifications. | |

| Longitudinal diffusion [1] | In isocratic methods, reduce excessive retention time by using a stronger mobile phase or switching to gradient elution. | |

| Early peaks are broader than later ones | Detector flow cell volume too large [3] | Use a smaller volume flow cell appropriate for the column dimension (e.g., micro or semi-micro flow cells). |

| Peak broadening with shouldering or splitting | Poor capillary connections or void at column head [4] | Check and re-make all connections. Ensure tubing is properly cut to a planar surface. Replace damaged fittings. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring and Maximizing Efficiency

To experimentally determine the efficiency of your system, inject a single, well-retained analyte and use the data system's software to calculate N. To maximize efficiency in UFLC methods:

- Select Appropriate Particle Size: Smaller, fully porous particles (e.g., 2-3 µm) or superficially porous particles (core-shell, ~2.7 µm dp) provide higher efficiency [5] [2].

- Optimize Flow Rate: Generate a van Deemter plot (H vs. linear velocity) to identify the optimal flow rate for your specific column and analyte, minimizing the plate height (H) [2].

- Minimize Extra-column Volume: Use the shortest and narrowest i.d. tubing possible between the injector and detector. For a 4.6 mm ID column, 0.18 mm i.d. tubing is recommended [3].

- Set Data Acquisition Correctly: Configure the DAD detector to acquire at least 20-30 data points per peak for accurate peak representation and integration. A low data rate results in jagged, poorly defined peaks [4].

The Retention Factor (k)

Definition and Role in Resolution

The retention (or capacity) factor, k, measures how long a compound is retained on the column relative to an unretained compound. It is calculated as k = (tR - t0) / t0, where t0 is the column void time [1]. The retention term in the resolution equation, k/(1+k), has a diminishing return on resolution. The most significant gains in resolution occur when k is between 1 and 5. For values of k > 10, further increases in retention provide negligible improvement in resolution while wasting analysis time and reducing peak height [1].

Troubleshooting Guide for Retention Time Issues

Shifts in retention time (tR) are a common problem that directly affects the k value and method reproducibility.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Retention time decreasing over consecutive runs | Faulty aqueous pump (Pump A) [4] | Purge and clean the check valves of the aqueous pump. Replace consumables if necessary. |

| Retention time increasing over consecutive runs | Faulty organic pump (Pump B) [4] | Purge and clean the check valves of the organic pump. Replace consumables if necessary. |

| Retention time shifts after method transfer or parameter change | Inconsistent mobile phase composition [6] | Prepare mobile phases consistently and accurately. Ensure solvents are thoroughly mixed. |

| Temperature mismatch [3] | Use a column oven for stable temperature control. Pre-heat the mobile phase if using high temperatures with larger i.d. columns. | |

| Pressure and frictional heating effects [7] | Be aware that high pressure alone can increase retention, while frictional heating can decrease it. This is critical when transferring methods to UHPLC. | |

| Poor peak shape (fronting) coinciding with retention changes | Sample solvent too strong [3] [4] | Dissolve the sample in the starting mobile phase composition or a solvent weaker than the mobile phase. |

| Column overload [3] | Reduce the sample injection volume or concentration. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Retention

To achieve optimal retention (k between 1 and 5) in reversed-phase UFLC:

- Scout the Gradient: Perform an initial scouting gradient from 5% to 100% organic solvent over 20-30 minutes. Analyze the chromatogram to see where peaks elute.

- Adjust Organic Strength: If peaks are too retained (k >> 5, late elution), increase the percentage of organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) in the mobile phase at the time they elute. If they are unretained (k < 1, early elution), decrease the organic strength.

- Fine-tune with Isocratic Elution: For simple mixtures, switch to an isocratic method. Use the scouting gradient to estimate the correct organic percentage for a k between 2 and 5.

- Control Temperature: Use a column oven. As a rule of thumb, retention time changes by 1-2% per °C in reversed-phase isocratic separations [4]. Consistent temperature is key for reproducible k values.

The Selectivity Factor (α)

Definition and Role in Resolution

Selectivity (α), or relative retention, is the ratio of the retention factors of two peaks: α = k2 / k1 [1]. It indicates the chemical distinction between analytes by the system. When α = 1, the peaks co-elute. The term (α-1)/α in the resolution equation has the most powerful impact. A small increase in α leads to a dramatic improvement in resolution, making it the most effective tool for solving challenging separations [2].

Troubleshooting Guide for Poor Selectivity (Co-elution)

When two or more peaks are not fully separated, altering selectivity is the most effective solution.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Co-elution of peaks (α ≈ 1) | Inappropriate stationary phase chemistry [2] | Change the column to one with a different mechanism (e.g., from C18 to Phenyl, PFP, or a polar-embedded phase) to exploit different secondary interactions (π-π, H-bonding). |

| Non-optimal mobile phase pH for ionizable compounds [2] | Adjust the pH of the aqueous buffer to manipulate the ionization state of acids and bases. A pH ± 2 units from the analyte's pKa can induce large retention shifts. | |

| Wrong organic modifier [2] | Switch from acetonitrile to methanol or vice-versa. Methanol is protic and can promote H-bonding and π-π interactions, while acetonitrile can suppress them. | |

| Peak tailing causing poor resolution between basic compounds | Secondary interaction with silanol groups on silica [3] | Use a high-purity silica (Type B) column, a polar-embedded phase, or a competing base like triethylamine in the mobile phase. |

| Selectivity changes after method transfer | Insufficient buffer capacity [3] | Increase the concentration of the buffer to better control the pH throughout the separation. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematically Improving Selectivity

To leverage selectivity for method development in UFLC-DAD:

- Change the Stationary Phase: This is the most powerful approach. If a C18 column does not provide separation, try a phenyl column for aromatic compounds, a pentafluorophenyl (PFP) phase for shape selectivity, or a cyanopropyl phase for mixed-mode interactions [2].

- Change the Organic Modifier: Substitute acetonitrile for methanol (or vice-versa). For example, when separating structural isomers on a phenyl column, methanol will promote π-π interactions, while acetonitrile will compete and disrupt them [2].

- Adjust the Mobile Phase pH: This is critical for ionizable analytes. If the pKa of your compounds is known, set the mobile phase pH at least 2 units above or below the pKa to ensure the analyte is fully ionized or non-ionized, creating a large shift in selectivity relative to neutral compounds [2].

- Optimize Temperature: Temperature can significantly affect selectivity, especially for chiral separations or molecules where conformation changes with temperature. Systematically vary the column temperature (e.g., from 25°C to 45°C) and observe its effect on α [2].

Advanced Topics: Integrating N, k, and α in UFLC-DAD Research

Visualizing the Relationship Between Resolution Factors

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting resolution by targeting efficiency (N), retention (k), and selectivity (α).

Diagram: A systematic troubleshooting workflow for chromatographic resolution, targeting the three key factors of the resolution equation.

Key Research Reagent Solutions for UFLC-DAD

The following table details essential materials and their functions for optimizing resolution in UFLC methods, based on protocols from recent research [8].

| Reagent / Material | Function in UFLC-DAD Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Type B Silica C18 Column (e.g., 100 mm x 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm) | Standard reversed-phase column providing a balance of efficiency, retention, and reproducibility for small molecules and biomolecules [8]. |

| Core-Shell (Superficially Porous) Particles | Provides higher efficiency than fully porous particles of the same size, leading to sharper peaks and improved resolution without the high backpressure of sub-2µm particles [5] [2]. |

| MS-grade Acetonitrile and Methanol | High-purity organic modifiers for the mobile phase to minimize baseline noise and detect impurities. Choice between them is a primary tool for manipulating selectivity (α) [8] [2]. |

| Volatile Buffers (e.g., Formic Acid, Ammonium Formate/Acetate) | Used to control mobile phase pH for manipulating selectivity of ionizable compounds. Essential for compatibility with mass spectrometry (MS) if used with DAD [8]. |

| Guard Column (matching stationary phase) | Protects the expensive analytical column from particulate matter and strongly adsorbed sample components, extending column life and maintaining efficiency (N) [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My peaks are tailing badly, which factor in the resolution equation is most affected and how can I fix it? A1: Peak tailing primarily degrades efficiency (N) by increasing peak width (wb). For a tailing peak, N calculated by the 16(tR/wb)^2 formula will be artificially low [5]. Common fixes include: using a high-purity silica column for basic compounds, ensuring proper capillary connections to avoid voids, and checking for column degradation or overloading [3].

Q2: I've transferred a method from HPLC to UHPLC, and my selectivity (α) has changed. Why? A2: This can be due to the combined effects of pressure and frictional heating in UHPLC. High pressure alone can increase retention, particularly for larger molecules. Simultaneously, frictional heating can create radial temperature gradients within the column, which may alter selectivity. Using a well-thermostatted column oven is crucial in UHPLC to minimize these effects [7].

Q3: How does temperature affect the three factors in the resolution equation? A3: Temperature primarily influences retention (k) and selectivity (α). Increased temperature typically reduces retention (k) and can sharpen peaks, slightly improving efficiency (N) by enhancing mass transfer [4]. Its effect on selectivity (α) can be significant, as it alters the thermodynamic equilibrium of partitioning between phases, making it a useful parameter for optimization, especially for complex or chiral separations [2].

Q4: What is a "real-world" example of using the resolution equation to fix a poor separation? A4: Imagine two closely eluting peaks with Rs = 1.0.

- To get Rs = 1.41, you could double the efficiency (N) by using a longer column or smaller particles, but this doubles the analysis time and pressure [2].

- Alternatively, you could adjust the selectivity (α). If you can change conditions so that α increases from 1.05 to 1.10, you would achieve the same resolution gain without increasing analysis time. This is done by changing the column chemistry, pH, or organic modifier [2]. This demonstrates why optimizing selectivity is often the most efficient path to better resolution.

The Impact of Stationary Phase Chemistry and Particle Technology on Peak Performance

For researchers in drug development, achieving optimal peak performance—characterized by high resolution, excellent symmetry, and consistent shape—is a critical yet frequently challenging aspect of Ultra-Fast Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (UFLC DAD) analysis. The root causes of peak performance issues often lie in the intricate relationship between the sample's chemical properties and the chromatography hardware, specifically the stationary phase chemistry and the particle technology of the column. A profound understanding of this relationship is essential for effective troubleshooting and robust method development. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to resolve common peak problems, enhance data quality, and accelerate your research.

Fundamental Concepts: Stationary Phase and Particles

The separation power of a liquid chromatography system is fundamentally governed by the column's stationary phase. This section outlines the core materials and their functions.

Research Reagent Solutions: Core Column Components

| Component | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| C18 Stationary Phase | A reversed-phase workhorse for general separations; provides hydrophobic interactions. Select for method development and analyzing small molecules [9]. |

| Phenyl-Hexyl Phase | Offers π-π interactions with aromatic analytes in addition to hydrophobicity. Use for separating structural isomers or compounds with aromatic rings for enhanced selectivity [9]. |

| Biphenyl Phase | Similar to phenyl-hexyl, employs multiple interaction mechanisms (hydrophobic, π-π, dipole). Ideal for metabolomics and polar aromatic compound separation [9]. |

| HILIC Phase | For hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Retains and separates polar compounds that elute too quickly in reversed-phase modes [10]. |

| Superficially Porous Particles (SPP) | Particles with a solid core and porous outer shell (e.g., Fused-Core). Provide high efficiency with lower backpressure than fully porous sub-2µm particles. Ideal for high-resolution, fast analyses [9] [11]. |

| Fully Porous Particles (<2 µm) | The standard for UHPLC. Enable high peak capacity and fast separations but require instrumentation capable of withstanding high pressures (up to 15,000 psi) [12] [11]. |

| Inert Column Hardware | Hardware with passivated surfaces (e.g., "biocompatible"). Crucial for analyzing metal-sensitive compounds like phosphorylated molecules, chelating PFAS, and pesticides, preventing adsorption and peak tailing [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Symptom: Peak Tailing

Peak tailing is a common distortion where the back half of the peak is broader than the front. The cause can be either thermodynamic (related to binding strength) or kinetic (related to binding speed) [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocols:

- Test for Kinetic Tailing: Prepare a standard solution of the tailing compound. Inject it using the current method, then repeat the injection at a significantly lower flow rate (e.g., 0.2 mL/min vs. 0.5 mL/min). If the peak asymmetry factor improves at the lower flow rate, the tailing has a kinetic origin [13].

- Test for Thermodynamic Tailing: Prepare a series of dilutions of the analyte (e.g., 10x, 50x, 100x). Inject these while keeping all other method parameters constant. If the peak shape improves dramatically at lower concentrations, the issue is likely thermodynamic overload of strong adsorption sites [13].

- Address Silanol Interactions: For basic compounds interacting with acidic silanols on the silica surface, the protocol is to switch to a stationary phase made with high-purity type B silica or one that is polar-embedded. Alternatively, add a competing base like triethylamine (TEA, 5-25 mM) to the mobile phase. Note that non-volatile additives like TEA are not suitable for LC-MS [3].

Symptom: Peak Fronting

Peak fronting occurs when the front of the peak is less steep than the back and is often related to column overload or specific column damage.

Detailed Experimental Protocols:

- Test for Column Overload: Dissolve the sample at a concentration 5-10 times lower than the current one, or reduce the injection volume. If the peak shape becomes symmetrical, the original method was overloading the column. To resolve, use a column with a larger internal diameter or a stationary phase with higher capacity, and continue to use the lower loading [3].

- Inspect for Column Damage (Voiding): Monitor system pressure. A sudden, permanent drop in pressure can indicate a void has formed at the column inlet. To confirm, compare the efficiency (plate count) of the column to its performance when new. A significant loss of efficiency indicates a void. While flushing the column in reverse direction can sometimes help, replacement is often necessary [3].

Symptom: Broader Than Expected Peaks

Broad peaks reduce resolution and sensitivity. The cause can often be traced to excessive extra-column volume or a detector cell that is too large for the column format.

Detailed Experimental Protocols:

- Minimize Extra-Column Volume: This volume includes all tubing, connectors, and the detector cell between the injector and the detector. For UHPLC, use short capillaries with a narrow internal diameter (e.g., 0.12-0.13 mm). A general rule is that the extra-column volume should not exceed 1/10 of the volume of the narrowest peak. Check all connections and replace any unnecessary unions or adapters [3] [14].

- Match Detector Cell to Column: The detector flow cell volume must be appropriate for the peak volumes generated by the column. For a typical UHPLC column (e.g., 50 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 µm particles), peak volumes can be around 7 µL. The cell volume should be < 1 µL to prevent significant peak broadening. Consult your instrument manual to select the correct cell [14].

Advanced Applications & Method Development

Quantitative Comparison of Stationary Phase Properties

The choice of stationary phase is a primary determinant of peak performance. The following table summarizes key properties of modern phases to guide selection.

| Stationary Phase Type | Key Mechanism(s) Beyond C18 | Ideal Application | Impact on Peak Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenyl-Hexyl | π-π interactions | Analysis of aromatics, isomers [9]. | Provides alternative selectivity, improving resolution of co-eluting peaks with aromatic rings. |

| Biphenyl | Hydrophobic, π-π, dipole, steric | Metabolomics, polar aromatics, isomer separation [9]. | Enhanced retention and shape for hydrophilic aromatics; 100% aqueous compatible. |

| Chiral | Enantioselective interactions | Separation of enantiomers [13]. | Can exhibit peak tailing due to heterogeneous sites (bi-Langmuir model); requires careful modeling for prep-scale. |

| HILIC | Partitioning, hydrogen bonding | Separation of polar, hydrophilic compounds [10]. | Retains compounds that show no retention in RPLC, preventing them from eluting as a broad solvent peak. |

| Inert C18 | Reduced metal interaction | Phosphorylated compounds, chelating agents (PFAS, pesticides) [9]. | Dramatically improves peak shape and analyte recovery for metal-sensitive molecules. |

Leveraging Particle Technology for Performance Gains

The physical structure of the packing particles is as important as their chemical coating.

- Superficially Porous Particles (SPP): Also known as fused-core or core-shell particles, SPPs consist of a solid, non-porous core surrounded by a thin, porous shell. This design creates a shorter path for mass transfer, reducing the C-term in the Van Deemter equation and leading to higher efficiency, especially at higher flow rates. They can achieve efficiencies close to those of sub-2 µm fully porous particles but with lower backpressure, making them suitable for a wider range of LC systems [9].

- Fully Porous Sub-2 µm Particles: These are the standard for UHPLC, designed to operate at pressures up to 15,000 psi (1000 bar). The smaller particles significantly increase the number of theoretical plates per column, leading to higher peak capacity and resolution. The primary trade-off is the requirement for instruments capable of handling very high pressures and the need for more stringent filtration of samples and mobile phases to prevent clogging [12] [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My peaks for a basic compound are tailing even on a high-purity C18 column. What are my next steps? First, verify that the column hardware is inert. If you are using a standard stainless-steel column, switch to one with inert or bio-inert hardware to rule out interactions with metal surfaces. Second, optimize the mobile phase pH to ensure the analyte is fully protonated and ion-suppressed if possible. Finally, consider using a competing base additive like triethylamine (for non-MS applications) or ammonium bicarbonate (for MS applications) to block residual silanol sites [9] [3].

Q2: When should I choose a superficially porous particle (SPP) column over a fully porous sub-2 µm column? SPP columns are an excellent choice when you need high efficiency on a conventional HPLC system that cannot reach UHPLC pressures, or when you want to maximize the performance of a UHPLC system without generating extreme backpressure. They are also known for providing excellent loading capacity. Sub-2 µm fully porous particles are the default for dedicated UHPLC systems where maximum peak capacity and resolution are required for extremely complex samples, and the system can handle the associated pressure [9] [11].

Q3: What is the single most important action to protect my column and maintain peak performance? Always use a guard column or pre-column filter. A guard column with the same stationary phase as your analytical column will trap particulate matter and strongly retained compounds that would otherwise foul the analytical column inlet, causing peak broadening, fronting, and loss of retention. Replacing a guard cartridge is far more cost-effective than replacing the analytical column [9] [3].

Q4: How does the mobile phase affect my peaks when I'm troubleshooting? The sample solvent strength relative to the mobile phase is a critical but often overlooked factor. If your sample is dissolved in a solvent stronger than the mobile phase (e.g., injected in 100% acetonitrile for a 90% water initial gradient), you will get peak splitting or fronting. Always try to dissolve your sample in the starting mobile phase composition or a weaker solvent. Additionally, ensure your mobile phases are freshly prepared and properly degassed to prevent baseline noise and ghost peaks [3].

Q5: We are developing methods for complex biotherapeutic samples. How can we improve peak capacity? For highly complex samples like those in proteomics or biopharmaceutical analysis, one-dimensional chromatography may be insufficient. Investigate comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography (LC×LC). This technique couples two separate columns with different separation mechanisms (e.g., reversed-phase and HILIC), dramatically increasing peak capacity and resolution. While method development is complex, new optimization approaches like multi-task Bayesian optimization are making it more accessible [10].

FAQs: Fundamental Principles of DAD Peak Purity

Q1: What is spectral peak purity, and why is it critical in pharmaceutical analysis?

Spectral peak purity assessment determines whether a chromatographic peak is composed of a single chemical compound or contains co-eluted impurities. This is vital in pharmaceutical analysis because inaccurate purity assessments can lead to incorrect quantitative results, potentially masking impurities that impact drug safety and efficacy. Structurally similar impurities often have similar UV spectra, making peak purity assessment a challenging but essential step in method development and validation to ensure the reliability of stability-indicating methods [15] [16].

Q2: What is the fundamental principle behind spectral similarity measurement?

The principle is to view a spectrum as a vector in n-dimensional space, where 'n' is the number of wavelength data points. The similarity between two spectra is then quantified by the angle between their corresponding vectors. A zero angle indicates identical spectral shapes. This is calculated as the cosine of the angle (θ) between the vectors, which is equivalent to the correlation coefficient (r) between the mean-centered spectral data arrays [15].

Q3: What are the common limitations of DAD-based peak purity assessment?

DAD peak purity assessment has several key limitations:

- It cannot detect impurities that lack characteristic UV-Vis chromophores.

- It struggles when the main analyte and impurity have highly similar spectra.

- It can be ineffective in "perfect co-elution" scenarios where the impurity profile is constant across the peak.

- Large concentration differences between the target compound and an impurity can mask the impurity's spectral contribution.

- A peak flagged as "pure" by DAD software cannot be assumed to be chemically pure; confirmation with a technique like Mass Spectrometry (MS) is often necessary [17] [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DAD Peak Purity Issues

This guide helps diagnose and resolve frequent problems encountered during peak purity analysis.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| False "Pure" Result | Impurity has no chromophore or a nearly identical spectrum to the main compound [17] [15]. | Confirm results with an orthogonal technique like MS. Use spectral processing (e.g., derivatives) to enhance spectral differences [17]. |

| False "Impure" Result | High analyte concentration causing detector saturation (>1.0 AU) [16]. | Dilute the sample to ensure absorbance remains within the linear range of the detector. |

| Incorrect baseline placement for peak purity calculation [15]. | Manually adjust the baseline start and stop points in the software to ensure accurate background subtraction. | |

| Poor Peak Shape | Column degradation or inappropriate stationary phase [3] [6]. | Replace or clean the column. Use a guard column. Ensure the sample solvent is compatible with the mobile phase. |

| Large system extra-column volume [3]. | Use short, narrow-bore capillary connections. Ensure the detector flow cell volume is appropriate for the column used. | |

| Irreproducible Purity Results | Unstable DAD lamp or insufficient mobile phase degassing [3] [6]. | Check and replace the DAD lamp if needed. Thoroughly degas all mobile phases. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Peak Purity in OpenLab CDS

The following workflow details the steps for configuring and performing a peak purity analysis using Agilent's OpenLab CDS software, a common platform in analytical laboratories [16].

Workflow Diagram: Peak Purity Analysis in OpenLab CDS

Step-by-Step Methodology

Create and Configure the Processing Method:

- In OpenLab CDS Data Analysis, load your injection and link it with a processing method that supports the 3D-UV feature (e.g., "3D UV Quantitative") [16].

- Integrate all peaks in the chromatogram.

- Identify the standard peaks: Select the integrated peaks in the chromatogram, right-click, and choose "Add multiple peaks as compounds to method." In the Processing Method window under

Compounds > Identification > Compound Table, assign a name to each compound [16].

Set Up UV Impurity Check Parameters:

- Navigate to

Compounds > Spectraand select the "UV Impurity Check" tab [16]. - Calculate UV Purity: Select to calculate for "All integrated peaks" or "Identified peaks only."

- Wavelength Range: Define the lower and upper wavelength (nm) to be used for the comparison. This range should be based on the solvent cutoff and the compound's spectral absorptions.

- Sensitivity: The default sensitivity is 50%. This value influences the threshold calculation for determining if a peak is pure (green) or impure (red). A higher sensitivity makes the purity check more stringent [16].

- Navigate to

Optimize and Calculate Sensitivity:

- In the

Compound Tabletab, you can adjust the "Impurity sensitivity" for each identified compound individually. - For a more automated approach (OpenLab CDS Rev 2.4+), right-click the "Impurity sensitivity" column and select "Calculate Sensitivity for All Compound(s)." The software will determine an appropriate sensitivity value for each peak, which is then recorded in the method [16].

- In the

Reprocess and Review:

- Select "Reprocess All" and "Save All Result" to apply the new method [16].

- Review the purity results in multiple windows:

- Injection Results window: Shows a purity flag for each peak.

- Chromatograms window: Provides a visual overview.

- Peak Details window: Offers a detailed view, including the purity ratio curve and threshold, allowing for in-depth inspection [16].

Advanced Protocol: Alternative Peak Homogeneity Assessment

This protocol describes an advanced, alternative method for evaluating peak spectral homogeneity using linear regression comparisons between all spectra in a peak, as explored in recent literature [17].

Workflow Diagram: Ellipsoid Volume Method for Spectral Homogeneity

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Spectral Acquisition and Digitization: Acquire UV spectra across the entire elution profile of the chromatographic peak. Export the spectra in a standard format (e.g., CSV) for external processing [17].

- Spectra Normalization: Normalize all acquired spectra to eliminate the influence of concentration differences and focus on spectral shape [17].

- Pairwise Linear Regression: Perform linear regression between each unique pair of normalized spectra. For each comparison, this will generate a set of three parameters: the slope, intercept, and correlation coefficient (r) [17].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean and standard deviation for the entire population of slopes, intercepts, and correlation coefficients derived from the pairwise comparisons [17].

- Ellipsoid Volume Calculation: Model the data as a three-dimensional ellipsoid where:

- The center is defined by the mean values of the slope, intercept, and correlation coefficient.

- The axes are defined by 2 times the standard deviation of each respective parameter.

- Calculate the volume (EV) of this ellipsoid. A smaller volume indicates higher spectral similarity across the peak [17].

- Purity Value Transformation: Convert the ellipsoid volume into a Peak Ellipsoid Volume (PEV) value using the formula: PEV = -log₁₀(EV). A higher PEV value corresponds to a higher degree of spectral homogeneity (purer peak) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials used in the experiments cited within this guide, which are typical for developing and validating DAD-based chromatographic methods.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Kinetex EVO C18 Column | A reversed-phase chromatographic column used for the separation of analytes like carbamazepine, demonstrating the application of peak purity assessment [17]. |

| Carbamazepine USP Standard | An active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) used as a model compound to study the influence of analyte amount on spectral homogeneity calculations [17]. |

| Acetylcysteine & Enalapril Maleate | Model compounds used to evaluate peak purity assessment in scenarios with overlapping peaks and spectral similarity [17]. |

| Nitrazepam & Diazepam | Compounds used to test peak purity algorithms under challenging conditions, such as perfect co-elution [17]. |

| HPLC-Grade Water & Acetonitrile | High-purity solvents used to prepare the mobile phase, critical for achieving a stable baseline and avoiding ghost peaks [17] [6]. |

In liquid chromatography, the shape of a chromatographic peak is a direct reflection of the underlying thermodynamic and kinetic processes occurring within the column. Adsorption thermodynamics governs the equilibrium distribution of analytes between the mobile and stationary phases, determining retention and selectivity. Meanwhile, adsorption-desorption kinetics controls the rate at which molecules adsorb to and desorb from the stationary phase, significantly influencing band broadening and peak shape. Under ideal conditions, these processes yield symmetrical, Gaussian-shaped peaks. However, peak tailing and other distortions commonly arise from slow desorption kinetics, secondary interactions, and system-related factors, presenting significant challenges for accurate quantification in UFLC DAD research. Understanding these fundamental drivers is essential for developing robust analytical methods in drug development.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Peak Shape Issues and Solutions

Comprehensive Peak Tailing Troubleshooting

Peak tailing is one of the most frequent challenges in chromatographic analysis. The table below summarizes common causes and their respective solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Peak Tailing in Reversed-Phase LC

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| All peaks are tailing | Basic compounds interacting with residual silanols on silica-based stationary phases [3] [18] | Use high-purity Type B silica columns, polar-embedded phases, or polymeric columns [3]. |

| Add a competing base (e.g., triethylamine) to the mobile phase [3]. | ||

| Use mobile phases with pH < 2.5 to suppress silanol ionization [18]. | ||

| Extra-column volume in system [3] [18] | Use short capillary connections with appropriate internal diameter (e.g., 0.13 mm for UHPLC) [3]. | |

| Ensure all fittings are properly made to avoid voids [18]. | ||

| Only some peaks are tailing | Specific analytes are basic while others are not [18] | Apply solutions for basic tailing, which will only affect the problematic basic compounds. |

| Strong sample solvent effect [18] | Ensure sample is dissolved in a solvent that is weaker than or matches the starting mobile phase composition [3] [18]. | |

| Peak fronting | Column overload [3] | Reduce the amount of sample injected [3]. |

| Channels in the column [3] | Replace the column [3]. |

Addressing Strong Adsorption of Specific Analytes

Some analytes, particularly those with specific functional groups, can exhibit strong, undesirable adsorption to system components or the stationary phase, leading to severe tailing, poor recovery, or even complete loss of the analyte.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Strongly Adsorbing Analytes

| Analyte Type | Chemistry of Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate- or Phosphate-containing compounds (e.g., metabolites, oligonucleotides) [19] | Strong Lewis base functional groups interact with metal ions (e.g., iron, aluminum) in the LC system (frits, tubing) or with metal oxides in certain stationary phases (e.g., zirconia) [19]. | Eliminate the surface: Use metal-free or biocompatible flow paths with plastic-lined components [19]. |

| Manage the interaction: Add a strong Lewis base (e.g., phosphate) or a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) to the mobile phase to compete for adsorption sites [19]. | ||

| Lewis Bases (e.g., carboxylic acids) on Zirconia-, Titania-, or Alumina-based columns [19] | Empty d-orbitals of the transition metal surface act as Lewis acids, strongly interacting with electron-rich Lewis bases [19]. | Mobile Phase Additive: Add a stronger Lewis base (e.g., phosphate for a carboxylate analyte) to the mobile phase to occupy all surface sites [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My peaks were symmetrical initially but have started tailing over time. What is the most likely cause? A1: Gradual deterioration of peak shape is often linked to column degradation. This can manifest as a void at the column inlet, contamination buildup on the frit or stationary phase, or chemical damage to the bonded phase. Flushing the column with a strong solvent according to the manufacturer's instructions can remove contamination. If the problem persists, the column may need to be replaced [3].

Q2: Why do smaller particle sizes in the column often improve peak resolution and shape? A2: Columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., sub-2µm fully porous or superficially porous particles) provide a higher theoretical plate number (N), which represents column efficiency. This results in sharper peaks, reducing their volume and improving the separation between closely eluting compounds [20] [21].

Q3: Can the instrument itself cause peak broadening or tailing? A3: Yes, several instrumental factors can contribute. An excessive extra-column volume (from tubing, connectors, detector cell) is a common cause, especially for early-eluting peaks on columns with small internal diameters. A detector with a slow response time or a too-large flow cell volume can also broaden peaks. Ensuring the system is plumbed correctly for the column dimensions and that detector settings are optimized is crucial [3].

Q4: What is "basic tailing" and how can I mitigate it? A4: Basic tailing occurs when protonated basic analytes (positively charged) undergo ionic interactions with negatively charged, ionized silanol groups (Si-O⁻) on the surface of the silica substrate. This is most pronounced at mobile phase pH values above ~2.5. Mitigation strategies include using low-pH mobile phases, specially purified silica (Type B) with fewer metal impurities and silanols, sterically shielded phases, or adding a competing base to the mobile phase [3] [18].

Quantitative Data and Measurement of Peak Shape

Accurate measurement of peak shape is vital for troubleshooting and method validation. The following table summarizes key metrics.

Table 3: Common Metrics for Quantifying Peak Shape Asymmetry

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Ideal Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP Tailing Factor (T) | ( T = \frac{W{0.05}}{2f} ) Where ( W{0.05} ) is the peak width at 5% height and ( f ) is the front half of the peak at 5% height [5]. | 1.0 | The most commonly used metric, often required by regulatory bodies like the FDA, which recommends a value of ≤2 for methods [5]. |

| Asymmetry Factor (As) | ( As = \frac{b}{a} ) Where ( b ) and (a) are the rear and front halves of the peak at 10% height [5]. | 1.0 | Similar to the tailing factor but measured at 10% peak height. |

| Theoretical Plates (N) | ( N = 5.54 \times (tR / W{0.5})^2 ) Where ( tR ) is retention time and ( W{0.5} ) is width at half height [5]. | Higher is better | A measure of column efficiency. Assumes a Gaussian peak and can be overestimated for tailing peaks [5]. |

For a more fundamental assessment that does not assume a Gaussian shape, the method of moments can be used. This method calculates the peak's statistical moments (mean, variance, skewness) and is highly sensitive to the exact start and end points of the peak and requires a high signal-to-noise ratio (S/N >200) for reliable results [5].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Adsorption Kinetics

Protocol: Inverse Method for Adsorption Isotherm Determination

This protocol allows for the determination of thermodynamic parameters (adsorption isotherm) which are intrinsically linked to kinetic behavior [20].

- Principle: The inverse method involves fitting simulated chromatograms, generated using a defined adsorption isotherm model and mass transfer kinetics, to experimental chromatograms obtained under overloaded conditions. The model parameters are adjusted until the simulation matches the experiment.

- Procedure: a. Column Characterization: Precisely measure the column's physical parameters: length, internal diameter, and total porosity. b. Experimental Data Acquisition: Acquire a set of chromatographic profiles by injecting the analyte of interest at a series of increasing concentrations, moving into the nonlinear range of the adsorption isotherm. c. Model Selection: Choose an appropriate adsorption isotherm model (e.g., Langmuir, Bi-Langmuir) to describe the equilibrium. d. Numerical Simulation & Fitting: Use chromatography simulation software to solve the mass balance equation (Equilibrium-Dispersive model or Transport-Dispersive model) and iteratively adjust the isotherm parameters to minimize the difference between the simulated and experimental band profiles.

- Outcome: Obtains the adsorption isotherm, which describes the equilibrium distribution of the analyte between the phases. A higher binding constant (( K )) from the isotherm is directly related to slower adsorption-desorption kinetics [20].

Protocol: Combined Stop-Flow and Dynamic Measurements for Kinetics

This advanced protocol is used to directly access the kinetic parameter of adsorption-desorption (( k_{ads} )) [20].

- Principle: This approach combines two types of measurements. Stop-flow (e.g., Peak Parking) experiments are used to measure effective diffusion coefficients (( D{eff} )), which inform on mass transfer resistances. Dynamic measurements under flowing conditions provide the plate height (H) of the column. The adsorption-desorption kinetics term (( c{ads} )) is then determined by subtracting all other calculated band-broadening contributions (eddy dispersion, longitudinal diffusion, solid-liquid mass transfer) from the total plate height [20].

- Procedure: a. Peak Parking (PP) Experiment: - Inject a small amount of analyte and allow the peak to migrate partway through the column. - Stop the flow for a predetermined parking time (( t{park} )). - Restart the flow and elute the peak. The band broadening during the parking time is related to the molecular and effective diffusion coefficients. - Repeat for different parking times to calculate ( D{eff} ) and ( Dm ) (molecular diffusion coefficient) [20]. b. Van Deemter Analysis: - Perform chromatographic runs at a series of different flow rates. - For each flow rate, calculate the height equivalent to a theoretical plate (H). - Plot H versus linear velocity to obtain the Van Deemter curve. c. Data Analysis: - Use the ( D{eff} ) from PP to calculate the longitudinal diffusion (b) and solid-liquid mass transfer (( cs )) terms in the Van Deemter equation. - Estimate the eddy dispersion term (( a(u) )). - The adsorption-desorption term (( c{ads} )) is then found as the residual contribution. The kinetic constant ( k{ads} ) can be derived from ( c{ads} ) [20].

- Application: This method has been used to demonstrate that adsorption-desorption kinetics is strongly dependent on particle geometry and the loading of the chiral selector, which is fundamental for optimizing CSPs [20].

Visualizing the Fundamentals of Peak Shape

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of how thermodynamic and kinetic factors influence peak shape.

The troubleshooting process for peak shape issues should be systematic, as outlined in the workflow below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Peak Shape Optimization

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Type B Silica Columns | Minimizes undesirable interactions between basic analytes and acidic silanol groups, reducing peak tailing [3] [18]. |

| Superficially Porous Particles (SPPs) | Core-shell particles can provide enhanced efficiency compared to fully porous particles (FPPs) of the same size, leading to sharper peaks [20] [21]. |

| Mobile Phase Buffers | Controls pH to ensure consistent ionization states of analytes and the stationary phase, critical for reproducibility and managing secondary interactions [21] [22]. |

| Competing Bases (e.g., Triethylamine - TEA) | Added to the mobile phase to sativate residual silanol sites on silica-based stationary phases, thereby reducing tailing of basic compounds [3]. |

| Lewis Base Additives (e.g., Phosphate) | Used to manage strong adsorption of Lewis basic analytes (e.g., carboxylates) on metal oxide-based columns (e.g., zirconia) by competing for adsorption sites [19]. |

| Chelating Agents (e.g., EDTA) | Added to the mobile phase to sequester metal ions in the system or stationary phase that can strongly interact with phosphate- or carboxylate-containing analytes [19]. |

Method Development and Optimization Strategies for Superior UFLC Separations

FAQs: Core Principles of Mobile Phase Optimization

Q1: How does mobile phase pH fundamentally affect the retention of my analytes?

The mobile phase pH primarily influences retention by controlling the ionization state of ionizable analytes. For acidic compounds, a lower pH (acidic environment) suppresses ionization, making the molecule more hydrophobic and increasing its retention time in reversed-phase chromatography. For basic compounds, the opposite occurs: a low pH promotes ionization, making the molecule more hydrophilic and decreasing its retention time [23] [24]. The most significant changes in retention occur within approximately ±1.5 pH units of the analyte's pKa. To ensure robust method robustness, it is best to operate at a pH where the analyte is either fully ionized or fully non-ionized, typically more than 1.5 pH units from its pKa [23].

Q2: Why is my peak shape poor, and how can the mobile phase fix it?

Poor peak shape, such as tailing or broadening, can often be traced to mobile phase composition. For basic analytes, tailing can result from ionic interactions with acidic silanol groups on the silica-based stationary phase. Using low-pH mobile phases (e.g., pH 2-4) suppresses silanol ionization and reduces this interaction [25]. Furthermore, mobile phases with low ionic strength (e.g., pure formic acid) can result in broader peaks and poorer resolution for peptides and proteins because they lack sufficient ion-pairing strength [26] [27]. Adding stronger ion-pairing agents like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or increasing buffer concentration can dramatically improve peak shape by masking silanol effects and increasing the stationary phase's capacity for the analyte [26] [27].

Q3: What is the trade-off between MS compatibility and chromatographic performance when choosing an acid modifier?

This is a central challenge in LC-MS method development.

- Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA): Considered the gold standard for chromatographic performance, providing excellent peak shape and retention for proteins and peptides due to its strong ion-pairing ability. However, it is a strong ion suppressor in mass spectrometry, severely reducing sensitivity [26] [28].

- Formic Acid (FA): The common choice for MS detection due to its good ionization efficiency and low ion suppression. However, it is a poor ion-pairing agent and a weaker acid, often leading to inferior peak shape and separation efficiency compared to TFA [26].

- Compromise Modifiers (e.g., Difluoroacetic Acid, DFA): Modifiers like DFA offer a middle ground. DFA provides better chromatographic performance than FA and causes less ion suppression than TFA, making it a promising alternative for combined LC-UV/MS analysis of intact proteins and monoclonal antibodies [26] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor or Inconsistent Peak Shape (Tailing or Broadening)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Tailing peaks for basic compounds | Ionic interaction with residual silanols on the column stationary phase [3]. | - Use a low-pH mobile phase (pH 2-4) to suppress silanol ionization [25].- Use a high-purity silica (Type B) or a polar-embedded column [3].- Add a competing base (e.g., triethylamine) or a strong ion-pairing agent (e.g., TFA) [3]. |

| Broad peaks for all analytes | Insufficient buffer capacity or ionic strength [27] [3]. | - Increase the buffer concentration (e.g., from 10 mM to 25 mM) [3].- Switch to a buffer with a higher buffering capacity at your operating pH [23]. |

| Broad peaks, especially in LC-MS | Use of mobile phase with low ion-pairing strength (e.g., formic acid) [26] [27]. | - For proteins/peptides, consider a compromise modifier like difluoroacetic acid (DFA) [26] [28].- For small molecules, test ammonium formate to increase ionic strength [27]. |

| Fronting peaks | Column overload or blocked frit [3]. | - Reduce the injection volume or sample concentration.- Check for a blocked inlet frit; replace the guard column or reverse and flush the analytical column [3]. |

Problem 2: Inadequate or Unstable Separation Selectivity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Drastic change in retention when pH shifts | Mobile phase pH is too close to the analyte's pKa [23]. | - Adjust the mobile phase pH to be >1.5 pH units away from the pKa of key analytes for more robust and stable retention [23]. |

| Co-elution of critical pairs | Insufficient selectivity under current conditions. | - Fine-tune the mobile phase pH within the allowable range; small changes (0.1-0.2 units) can significantly alter selectivity for ionizable compounds with similar pKa values [23].- Change the organic solvent type (e.g., from acetonitrile to methanol) to exploit different selectivity [25]. |

| Poor resolution that degrades over time | Poor buffering capacity leading to uncontrolled pH shifts during the run [23]. | - Prepare the buffer accurately and ensure the mobile phase pH is within ±1 unit of the buffer's pKa for effective buffering [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key mobile phase additives and their functions for optimizing separations in UFLC DAD research.

| Reagent Name | Function / Rationale for Use | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Strong ion-pairing agent; provides excellent peak shape and retention for proteins/peptides in LC-UV [26] [27]. | Strong ion suppressor; not recommended for LC-MS unless sensitivity is not a priority [26]. |

| Difluoroacetic Acid (DFA) | Stronger ion-pairing agent than formic acid; provides a balance of good chromatographic performance and acceptable MS sensitivity for proteins [26] [28]. | A recommended alternative to TFA for combined LC-UV/MS workflows [26]. |

| Formic Acid (FA) | Volatile acid; modifier of choice for LC-MS due to good ionization efficiency and low suppression [26] [25]. | Can result in poor peak shape and less efficient separations for proteins and peptides compared to TFA or DFA [26]. |

| Ammonium Acetate / Formate | Volatile buffers; used to control pH and ionic strength in LC-MS compatible methods. | Ensure the selected pH is within the effective buffering range (pKa ±1) [25]. |

| Phosphoric Acid / Phosphate Buffers | Provide high buffering capacity and ionic strength at low pH; excellent for LC-UV methods to control peak shape and retention [25] [27]. | Not volatile and generally incompatible with MS detection. Ideal for stability-indicating methods where MS is not used [25]. |

| Methane sulfonic acid (MSA) | Strong acid and ion-pairing agent; identified as a potential alternative to TFA for the analysis of protein biopharmaceuticals in RPLC mode [28]. | Requires evaluation for specific applications, as the impact on MS signal can vary. |

Mobile Phase Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for optimizing the mobile phase to improve peak resolution and shape.

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Systematic Evaluation of Acid Modifiers for Protein Analysis

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing TFA, FA, and DFA for the LC-UV/MS analysis of proteins [26] [28].

1. Materials:

- Standards: A mixture of standard proteins (e.g., Ribonuclease, Ubiquitin, Lysozyme, Myoglobin).

- Mobile Phase A (Aqueous): Water containing 0.1% (v/v) of the acid modifier under evaluation (TFA, FA, or DFA).

- Mobile Phase B (Organic): Acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) of the same acid modifier.

- Column: Reversed-phase C4 or C8 column (e.g., 300 Å pore size, 1.0 mm or 2.1 mm i.d.).

- Instrumentation: UFLC system coupled to both a DAD and a Mass Spectrometer.

2. Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column Temperature: 50 °C

- Flow Rate: 0.2 mL/min (for 2.1 mm i.d. column)

- Injection Volume: 5 µL

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 30 minutes.

- UV Detection: 214 nm

- MS Detection: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) in positive mode.

3. Procedure: 1. Equilibrate the column with starting conditions (5% B) for at least 10 column volumes. 2. Inject the protein standard mixture. 3. Run the gradient method, acquiring data from both UV and MS detectors simultaneously (using a flow splitter if necessary). 4. Repeat the experiment for each acid modifier (TFA, FA, DFA) using a freshly prepared mobile phase.

4. Data Analysis:

- Chromatographic Performance: For the UV chromatogram, calculate and compare the peak width at half height (W~1/2~) for each protein. Narrower peaks indicate higher efficiency [26].

- MS Performance: Compare the total ion current (TIC) and the signal intensity (peak height) for each protein across the different modifiers.

Protocol 2: Investigating pH and Ionic Strength Effects on Small Molecules

This protocol outlines a robust approach to optimize pH and buffer concentration for small molecule separations [23] [25].

1. Materials:

- Standards: A mixture of your ionizable analytes with known pKa values.

- Buffers: Prepare a series of buffers (e.g., 25 mM phosphate or ammonium formate) at different pH values (e.g., pH 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5). For ionic strength tests, prepare buffers at a fixed pH but varying concentrations (e.g., 10 mM, 25 mM, 50 mM).

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile or methanol.

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column.

2. Chromatographic Conditions:

- Use an isocratic or shallow gradient method that provides baseline separation of all components.

- Keep the organic modifier percentage constant when testing pH, and vice versa.

3. Procedure: 1. Starting with the lowest buffer concentration (e.g., 10 mM), run the analysis at each pH value. 2. Record retention time, peak asymmetry, and plate number for each analyte. 3. Select the optimal pH, then repeat the experiment at different buffer concentrations to assess the impact on peak shape and retention time stability.

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot retention time vs. pH for each analyte to visualize the ionization profile and identify a robust pH window.

- Plot peak asymmetry vs. buffer concentration to determine the minimum concentration required for symmetrical peaks.

Leveraging Column Chemistry and Advanced Stationary Phases for Challenging Separations

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Poor Peak Shape

Problem: Peaks in your chromatogram are tailing, fronting, or splitting, which reduces resolution and compromises accurate quantification [29].

| Problem | Common Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Tailing Peaks | - Secondary interactions with residual silanol groups on stationary phase [30]- Inappropriate mobile phase pH [29]- Column contamination [29] | - Use a column designed to minimize silanol activity (e.g., with steric protection) [31]- Optimize mobile phase pH to suppress analyte ionization [30]- Flush column with strong solvent or use a guard column [29] |

| Fronting Peaks | - Column overloading (injecting too much sample) [29]- Improper mobile phase composition [29] | - Reduce injection volume or sample concentration [22]- Ensure mobile phase solvent strength is appropriate [29] |

| Split Peaks | - Column void or obstruction at inlet frit [30]- Chemical or mechanical issues [32] | - Perform a brief, careful reverse-flow rinse (if manufacturer allows) [30]- Replace the column if the inlet frit is blocked or a void has formed [33] |

| Broad Peaks | - Column inefficiency due to aging [29]- Excessive flow rate [22]- Mobile phase viscosity [29] | - Replace aged column [33]- Optimize flow rate for efficiency [22]- Consider a column with solid-core particles for higher efficiency [31] |

| Ghost Peaks | - Contamination in mobile phase or system [29]- Sample carryover [29] | - Use high-purity reagents and clean solvents [22]- Employ a column designed to suppress ghost peak formation [29] |

Guide 2: Addressing Low Peak Resolution

Problem: Inadequate separation between analyte peaks, leading to co-elution and difficulty in identification and quantification [22].

| Problem | Common Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Co-elution of Peaks | - Lack of selectivity for your specific analytes [34]- Mobile phase strength too high [22] | - Switch to a stationary phase with different selectivity (e.g., Biphenyl, polar-embedded C18) [35] [34]- Weaken the mobile phase (e.g., decrease organic solvent %) [22] |

| Changes in Selectivity | - Uncontrolled mobile phase pH [22]- Batch-to-batch column variability [35] | - Use a buffered mobile phase to control pH [22]- Select a column manufacturer with high batch-to-batch reproducibility [35] |

| Poor Efficiency | - Column degraded or failing [33]- Suboptimal flow rate [22]- Extra-column volume in system [35] | - Replace old column [33]- Use Van Deemter plot to find optimal flow rate [31]- Ensure system connections are optimal, especially for UHPLC [35] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does stationary phase chemistry influence selectivity and resolution?

The stationary phase's chemistry governs the primary interactions with your analytes, making it the most powerful tool for controlling selectivity and resolution [34]. While a C18 phase separates primarily based on hydrophobicity, phases with additional functionalities, such as biphenyl or polar-embedded groups, introduce different interaction mechanisms (e.g., π-π, hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole) [31] [34]. This expanded interaction capability can resolve co-eluting compounds that a simple C18 phase cannot distinguish, directly improving resolution [34].

2. When should I consider using a column with superficially porous particles (SPP)?

Columns with superficially porous particles (SPP or core-shell) are an excellent choice when you need higher efficiency and resolution without switching to a UHPLC system that can handle very high backpressures [31]. The solid core and thin porous shell of SPP particles reduce band broadening, resulting in sharper peaks and better resolution. A key advantage is that they can often be operated on a standard HPLC system while providing performance approaching that of sub-2µm fully porous particles used in UHPLC [31].

3. What practical steps can I take to ensure my column performs reproducibly over time?

- Use a Guard Column: A guard column is a cost-effective way to protect your analytical column from contaminants and particulates that can degrade performance and shorten its lifespan [34].

- Filter Samples: Always filter your samples through a membrane compatible with your solvents (e.g., 0.45 µm or 0.2 µm) to remove particulates that can clog the column frit [34].

- Follow Recommended pH Limits: Operate your column within the manufacturer's specified pH range. Using a "ruggedized" phase like ARC-18 can be beneficial for low pH applications [31].

- Proper Equilibration: Allow sufficient time for the column to equilibrate with the mobile phase, typically the equivalent of 7-10 column volumes, especially when starting a gradient method [31].

4. How can I systematically compare different columns to find the best one for my separation?

Multidimensional modeling is a powerful approach for systematic column comparison [35]. By running a limited set of calibration experiments (e.g., 12 runs per column) that vary key parameters like gradient time (tG), temperature (T), and pH, you can build a model that predicts the Method Operable Design Region (MODR) for each column. Comparing these MODRs helps identify a shared set of robust method conditions where columns can be used interchangeably, or it can highlight a column with uniquely orthogonal selectivity for your specific application [35].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Column Selectivity Comparison Using MODR

This methodology uses a multidimensional modeling approach to objectively compare the separation performance and robustness of different stationary phases [35].

1. Define the Separation Challenge

- Prepare a solution containing all analytes and expected impurities in a solvent compatible with the mobile phase.

- Define your critical resolution requirement (e.g., Rs ≥ 1.5 for baseline separation).

2. Select Columns and Parameter Ranges

- Choose at least two stationary phases with potentially orthogonal selectivity (e.g., a standard C18 and a Biphenyl phase) [35] [31].

- Define practical ranges for key parameters. A typical 3D model might use:

- Gradient Time (

tG): e.g., 5 - 25 minutes - Temperature (

T): e.g., 30 - 50 °C - pH: e.g., 2.5 - 6.5 (ensure column compatibility)

- Gradient Time (

3. Execute the Calibration Experiments

- For a

tG-T-pHmodel, perform 12 calibration runs according to the experimental design [35]. - Use a consistent mobile phase buffer system and organic modifier (e.g., acetonitrile).

- Maintain consistent flow rate and detection parameters (e.g., DAD full spectrum or specific wavelengths).

4. Model Building and MODR Identification

- Input the retention data for all peaks from the 12 runs into modeling software.

- The software will calibrate a model to predict retention and resolution across the entire 3D parameter space.

- Identify the Method Operable Design Region (MODR), which is the region where all critical peak pairs meet your resolution requirement (e.g., Rs ≥ 1.5) [35].

5. Column Comparison and Selection

- Overlay the MODRs from different columns to find shared robust method conditions.

- Select the column that provides the largest MODR for maximum method robustness, or the one with the most orthogonal selectivity if it better resolves a critical pair [35].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting with a Quality Control Reference Material

Using a well-characterized standard mixture to diagnose system and column problems quickly [33].

1. Acquire or Prepare a QC Standard

- Use a commercial QC reference material (e.g., Waters Neutrals QCRM) or prepare a simple mixture of 3-4 stable, neutral compounds like uracil, acetone, naphthalene, and acenaphthene [33].

2. Establish a Benchmark Chromatogram

- Under optimal, known-good system conditions, run the QC standard 5-10 times.

- Record the average retention times, peak areas, USP tailing factor, and USP plate count. This is your system performance benchmark [33].

3. Regular Monitoring and Problem Diagnosis

- Run the QC standard regularly (e.g., at the start of each sequence) or whenever a problem is suspected.

- Compare the new chromatogram to your benchmark.

- Shift in Retention Time: May indicate pump problems (leak, bad check valve), mobile phase composition error, or temperature fluctuation [33].

- Increased Peak Tailing: Suggests column degradation, a void at the column inlet, or secondary chemical interactions [33].

- Decreased Plate Count: Often a sign of a failing column or a blockage [33].

- Peak Splitting: Can be caused by a column void or an improper column connection [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and tools essential for overcoming challenging separations.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Biphenyl Phase Columns | Provides orthogonal selectivity vs. C18 via π-π interactions with aromatic or conjugated compounds [31]. |

| Polar-Embedded Phase Columns | Incorporates polar groups (e.g., amide) into the alkyl chain; improves retention and peak shape for polar bases and acids [34]. |

| Ruggedized C18 Columns (e.g., ARC-18) | Features steric protection of silanol groups; stable at low pH (1-3), ideal for separating acids and charged bases [31]. |

| Superficially Porous Particle (SPP) Columns | Solid-core particles with a porous shell; offer high efficiency and resolution at lower operating pressures than sub-2µm fully porous particles [31]. |

| Guard Columns / Cartridges | Small cartridge installed before the analytical column; traps contaminants and particulates, extending column life [34]. |

| QC Reference Material (e.g., Neutrals Mix) | Standard mixture of neutral compounds; used for system suitability testing, performance benchmarking, and troubleshooting [33]. |

| In-Line Filters | Frit installed before the guard/analytical column; protects against particulate matter from samples or mobile phase [34]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

Stationary Phase Interaction Mechanisms

Optimizing Temperature and Flow Rate for Enhanced Efficiency and Analysis Speed

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

How do temperature and flow rate directly impact peak resolution and shape?

Temperature and flow rate are critical method parameters that directly control the speed and quality of your separation by influencing how analytes interact with the mobile and stationary phases.

- Temperature Impact: Increasing the temperature of the column reduces the viscosity of the mobile phase, which lowers the system backpressure. This allows for the use of higher flow rates or longer columns to increase efficiency. Furthermore, higher temperatures typically accelerate the mass transfer of analytes between the mobile and stationary phases, leading to sharper peaks and improved resolution. However, excessive heat can degrade the column stationary phase, especially outside its specified pH and temperature range, causing peak broadening and tailing [3] [36].

- Flow Rate Impact: The flow rate controls the linear velocity at which the mobile phase moves through the column. Using a flow rate that is too high can reduce the interaction time between analytes and the stationary phase, potentially worsening resolution and increasing backpressure. Conversely, a flow rate that is too low can lead to excessive peak broadening due to longitudinal diffusion, unnecessarily extending the analysis time [3] [37].

My peaks are tailing or fronting. Could temperature or flow rate be the cause?

While peak tailing and fronting are often caused by other factors, temperature and flow rate can contribute indirectly.

- Peak Tailing: This is frequently caused by secondary interactions (e.g., with residual silanol groups on the stationary phase) or column degradation [38] [3]. While adjusting temperature and flow rate might offer minor improvements, the root cause is usually chemical or physical. For tailing, ensure your method uses a sufficient buffer concentration to mask these active sites [37].

- Peak Fronting: This can be a symptom of column overload (too much sample mass) or a physical issue like a void in the column bed [38] [3]. A thermal mismatch, where the temperature of the injected sample solvent differs significantly from the column temperature, can also cause peak distortion, including fronting [3]. Using a column oven to maintain a stable temperature is the best solution.

Primary causes and solutions for peak shape issues:

| Symptom | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing | Secondary interactions with stationary phase | Use a high-purity silica column; add buffer to mobile phase [38] [37] |

| Column degradation or void | Replace column; check column specifications for pH/temperature limits [3] | |

| Peak Fronting | Column overload | Reduce injection volume or dilute the sample [38] [37] |

| Thermal mismatch / Solvent incompatibility | Use an eluent pre-heater; ensure sample solvent is compatible with mobile phase [3] |

How can I systematically optimize temperature and flow rate for my method?

A systematic approach is key to finding the optimal balance between analysis speed, resolution, and pressure. The following workflow provides a practical protocol for this optimization.

Experimental Optimization Protocol:

- Establish a Baseline: Begin with the manufacturer's recommended flow rate for your column's internal diameter (e.g., 0.2-0.6 mL/min for 2.1 mm UHPLC columns) and a moderate temperature of 30-40°C [37].

- Temperature Screening: Inject your standard mixture at a fixed flow rate across a temperature gradient (e.g., 30°C, 40°C, 50°C, 60°C). Monitor changes in retention time, resolution between critical pairs, and peak shape.

- Evaluate and Refine: Identify the temperature that provides the best compromise of analysis speed and resolution without causing peak distortion or excessive pressure.

- Flow Rate Adjustment: With the optimal temperature fixed, now adjust the flow rate. Increase the flow rate to shorten run times, but be mindful of the pressure limit and any loss in resolution. Conversely, if resolution is inadequate, a slight decrease in flow rate might help.

- Final Validation: Once a promising set of conditions is found, perform multiple injections to ensure the method is robust, precise, and produces consistent retention times and peak areas.

I've optimized these parameters, but I'm still not getting the resolution I need. What's next?

If temperature and flow rate adjustments are insufficient, the selectivity of your separation needs to be changed. This involves altering the fundamental chemistry of the interaction.

- Change the Mobile Phase Composition: The type and ratio of organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile vs. methanol) and the pH of the aqueous buffer are the most powerful tools for altering selectivity, especially for ionizable compounds [3] [37]. A small change in pH can significantly shift the retention of acids and bases.

- Select a Different Stationary Phase: If the mobile phase does not yield the desired resolution, switch to a column with different chemistry. Options include C8 vs. C18, phenyl, polar-embedded, or HILIC phases, which offer different selectivity and interaction mechanisms with your analytes [3] [37].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Use this table to quickly diagnose and address issues related to method parameters.

| Symptom | Possible Cause Related to Temp/Flow | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure is too high | Flow rate is too high for the viscosity of the mobile phase at a given temperature. | Reduce flow rate or increase column temperature to lower viscosity [6]. |

| Pressure is too low | Flow rate is set too low or a leak is present (unrelated to temperature). | Check and adjust the set flow rate; inspect system for leaks [6]. |

| Retention time shifting | Column temperature is fluctuating. | Ensure the column oven is set correctly and has stabilized; use a column oven for consistent temperature [38] [36]. |

| Poor peak resolution | Flow rate is too high, not allowing sufficient interaction time; or temperature is not optimized. | Lower the flow rate to improve resolution, or screen different temperatures to improve selectivity [3] [37]. |

| Broad peaks | Flow rate is too low, leading to longitudinal diffusion; or column temperature is too low. | Increase flow rate or increase column temperature to sharpen peaks [3] [37]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following materials are fundamental for developing and running robust UFLC-DAD methods.

| Item | Function in the Context of UFLC-DAD |

|---|---|

| C18 UHPLC Column | The workhorse stationary phase for reversed-phase chromatography. Sub-2µm particles provide high efficiency and resolution [39]. |

| Buffers (e.g., Formate, Phosphate) | Control the pH of the mobile phase, which is critical for reproducible retention of ionizable compounds and for suppressing silanol interactions that cause peak tailing [40] [41]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity water, acetonitrile, and methanol are essential for a stable baseline, low background noise, and preventing system contamination [36] [37]. |

| Guard Column | A small cartridge containing the same stationary phase as the analytical column. It protects the expensive analytical column from particulate matter and irreversibly adsorbed sample components, significantly extending its life [38] [3]. |

| In-Line Filter | Placed before the column, it traps particulates from the mobile phase or sample, preventing frit blockage and pressure spikes [3] [36]. |

| Column Oven | Provides precise and stable temperature control, which is mandatory for achieving reproducible retention times and as a variable for method optimization [3] [36]. |

Advanced Gradient Design and Transfer from Analytical to Semi-Preparative Scale

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What defines a semi-preparative HPLC method? Semi-preparative HPLC is a purification workflow defined by its goal: to isolate and purify specific compounds from a sample mixture for further use (e.g., research, characterization). The scale is determined by the available sample amount and the desired yield, and it is not exclusively defined by high flow rates or large columns. The key objective is to obtain purified samples with high yield and purity, sometimes even utilizing analytical-scale flow rates when the highest resolution is required to separate challenging impurities [42].

2. Why is my peak resolution poor after transferring a method to a semi-prep column? Poor resolution after scale-up often stems from inaccurate method transfer calculations. If the flow rate, injection volume, or gradient time are not correctly scaled to the new column dimensions, the separation efficiency will decrease. Utilize a prep scaling calculator to ensure all parameters are adjusted based on the column volume ratio. Additionally, consider the system's dwell volume, as differences between analytical and preparative systems can cause gradient delays and misalignments [43].

3. How can I effectively remove early and late eluting impurities during purification? For complex mixtures with both early and late eluting impurities, a Gradient Twin-Column Recycling Liquid Chromatography (GTCRLC) process can be highly effective. This automated method uses an initial gradient step to shave off both early and late impurities. Subsequently, the target compound and its closest impurities are subjected to an isocratic recycling process on twin columns to achieve baseline resolution, ensuring high purity by eliminating all classes of impurities [44].