Advanced Strategies to Overcome Spectral Interference in UV-Vis Spectrophotometry for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of spectral interference in UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

Advanced Strategies to Overcome Spectral Interference in UV-Vis Spectrophotometry for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the critical challenge of spectral interference in UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores how interfering contaminants, scattering, and environmental factors compromise accuracy in biomedical analysis—from protein quantification to drug formulation. The content details innovative methodological approaches, including chemometric modeling, refractive index assistance, and data fusion techniques, validated through comparative studies. Practical troubleshooting protocols and optimization strategies are presented to enhance reliability, ensuring precise quantification of analytes like hemoglobin, antibiotics, and proteins in complex biological matrices, ultimately supporting robust analytical outcomes in pharmaceutical and clinical settings.

Understanding Spectral Interference: Sources and Impact on Biomedical Analysis

Defining Spectral Interference and Its Consequences in Quantitative Analysis

Technical Support Center: FAQs on Spectral Interference

FAQ 1: What is spectral interference and why is it a problem in UV-Vis spectrophotometry?

Spectral interference is a prevalent issue in UV-Vis spectrophotometry that occurs when substances other than the analyte of interest absorb light at the same wavelength being used for measurement [1]. This compromises the accuracy of quantitative analysis because the measured absorbance no longer originates solely from the target compound. The consequences are significant: even minuscule amounts of a contaminant with high molar absorptivity can cause substantial errors. For instance, a mere 1% DNA contamination can result in a 26.3% error in bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein concentration analysis [1]. These errors are particularly problematic in complex samples from pharmaceuticals, environmental chemistry, and biotechnology where multiple absorbing species coexist [1] [2].

FAQ 2: How can I identify if my UV-Vis measurements are affected by spectral interference?

Several indicators suggest spectral interference might be affecting your results [3]:

- Non-linear calibration curves despite using appropriate standards and dilution schemes

- Unexpected peaks or shoulders in the absorption spectrum

- Absorbance values that exceed the instrument's linear range even with significant sample dilution

- Poor reproducibility between replicates

- Disagreement between concentration values obtained via UV-Vis and other techniques like refractometry [1]

A practical method to detect interference is to compare results from UV-Vis spectrophotometry with those from constrained refractometry. Significant disagreements often indicate the presence of unaccounted impurities [1].

FAQ 3: What are the most effective methods to overcome spectral interference?

Multiple technical approaches can minimize or correct for spectral interference [2]:

- Derivative Spectroscopy: This method helps resolve overlapping absorption peaks by converting normal spectra into first or second derivatives, which can differentiate between closely spaced or overlapping absorbance bands. It also corrects for baseline shifts and scattering effects from unidentified interfering compounds [2].

- Mathematical Correction Techniques: These include isoabsorbance measurements (for single known interferents), multicomponent analysis (for multiple interferents with spectral overlap), and three-point correction (for non-linear background absorbances) [2].

- Refractive Index-Assisted UV/Vis Spectrophotometry: This innovative approach combines UV-Vis with constrained refractometry to detect and reduce errors from unknown contaminants. The method leverages the fact that refractive indices of most liquids fall in a narrow range (1.3-1.6), making refractometry less susceptible to large errors from impurities [1] [4].

- Sample Purification: Implementing optimized sample isolation protocols and ensuring samples are purified prior to measurement remains a fundamental approach [5].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for sample preparation to minimize interference?

Proper sample preparation is crucial for reliable UV-Vis results [3] [5]:

- Use high-purity solvents and ensure they don't absorb at your measurement wavelengths

- Employ appropriate cuvettes: Quartz cuvettes are essential for UV measurements as glass and plastic absorb UV light [6] [3]

- Clean sample holders thoroughly with deionized water and handle only with gloved hands to avoid contamination [3] [5]

- Ensure sample homogeneity by mixing solutions thoroughly before measurement [5]

- Maintain appropriate concentration ranges (typically absorbance values between 0.1-1.0 AU) to stay within the instrument's linear dynamic range [6] [7]

- Control environmental factors like temperature and pH that can affect absorption spectra [3] [8]

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Spectral Interference

Protocol: Refractive Index-Assisted UV/Vis Spectrophotometry

This protocol demonstrates how constrained refractometry can aid UV-Vis spectroscopy to overcome spectral interference from unknown impurities, based on the research by Antony and Mitra [1].

Principle: The method utilizes the differing fundamental principles of spectrophotometry (governed by Beer-Lambert law) and refractometry (governed by Lorentz-Lorenz equation). While molar absorptivities vary significantly across compounds, refractive indices of most liquids fall within a narrow range (1.3-1.6), making refractometry less susceptible to dramatic errors from minor impurities [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-2600)

- Refractometer with high precision (e.g., ATAGO RX-7000i, least count ~1×10⁻⁵ units)

- Quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length)

- Temperature-controlled environment (20±0.01°C)

- High-purity solvents and analytes

Procedure:

- Prepare standard solutions of the analyte in appropriate solvent systems.

- Measure UV-Vis absorption spectra of both pure analyte solutions and potentially contaminated samples.

- Simultaneously measure refractive indices of all samples using the refractometer.

- For contaminated samples, use the modified Lorentz-Lorenz equation to calculate the maximum possible error in refractometry:

max errorRI% = [0.15511/(μa - μsol)] × (VI/va) × 100%where μ represents (n²-1)/(n²+2), n is refractive index, VI is total impurity volume, and va is analyte volume [1]. - Compare concentration values obtained from both techniques. Significant discrepancies indicate spectral interference.

- When interference is detected, use the refractometry data as a constrained reference to obtain more accurate concentration values.

Application Example: In a solution of benzene in cyclohexane contaminated with N,N-Dimethylaniline (NND) in ratio 100:1, this method reduced estimation error from 53.4% (with regular UV spectrophotometry) to just 2% [1].

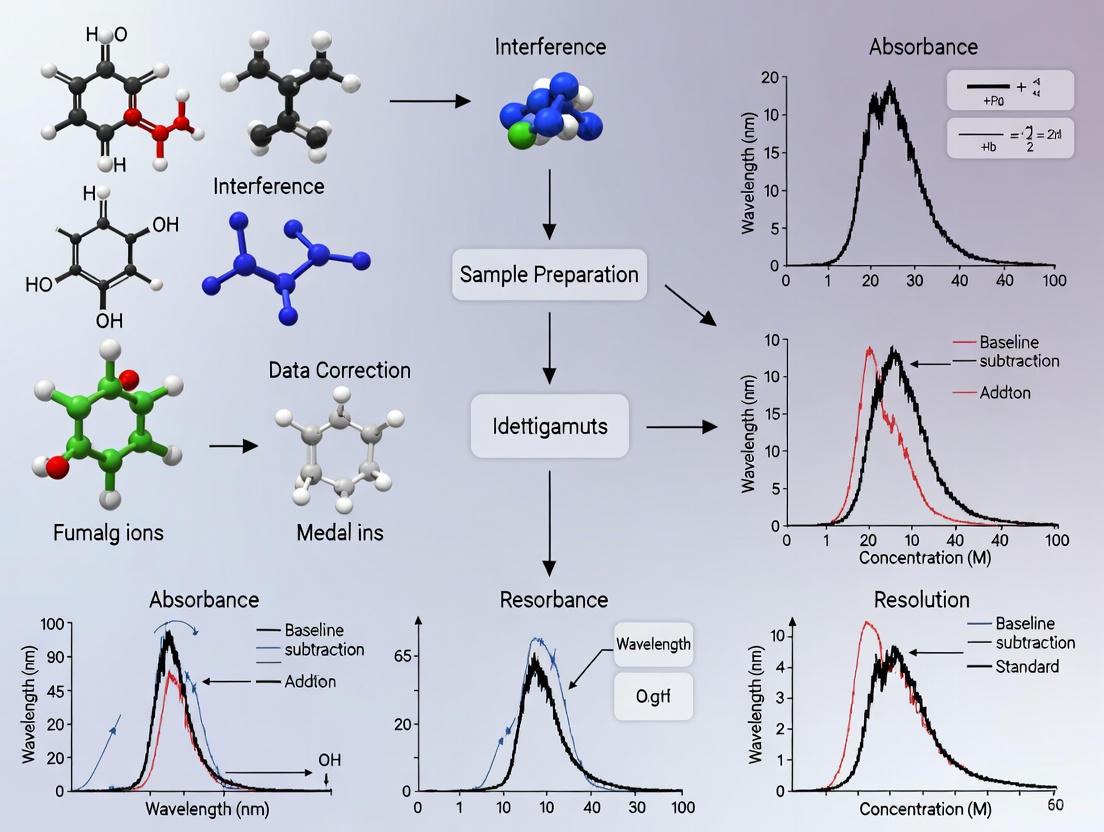

Workflow: Comprehensive Approach to Address Spectral Interference

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for identifying and addressing spectral interference in UV-Vis spectrophotometry:

Quantitative Data on Spectral Interference Effects

Table 1: Error Magnitude Caused by Specific Interfering Substances

| Analyte | Interfering Substance | Interferent:Aanalyte Ratio | Error in UV-Vis Analysis | Error with Refractive Index Assistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene in cyclohexane | N,N-Dimethylaniline | 1:100 | 53.4% | 2% | [1] |

| BSA protein | DNA | 1:100 | 26.3% | Not specified | [1] |

| Various analytes | Multiple unknown impurities | Laboratory comparison | Up to 22% coefficient of variation | Not specified | [9] |

Table 2: Effectiveness of Different Interference Correction Methods

| Correction Method | Applicable Scenario | Advantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivative Spectroscopy | Overlapping peaks, baseline shifts | Differentiates closely spaced peaks; corrects for scattering | Requires specific instrument capabilities; may reduce signal-to-noise ratio | [2] |

| Mathematical Corrections (Isoabsorbance, Multicomponent) | Single or multiple known interferents | Can be implemented with standard instruments | Requires prior knowledge of interferent spectra | [2] |

| Refractive Index-Assisted UV/Vis | Unknown interfering contaminants | Works without prior knowledge of impurities; identifies major interferent | Less effective when analyte isn't major component; lower sensitivity than UV-Vis | [1] [4] |

| Sample Purification | All interference types | Eliminates source of interference | Time-consuming; may result in analyte loss | [5] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Spectral Interference Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Spectral Interference Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample containment for UV measurements | Essential for UV range due to transparency; must be meticulously cleaned | [6] [3] |

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., cyclohexane, water) | Dissolving analytes | Must not absorb at measurement wavelengths; check absorbance before use | [3] [8] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation | Provides accurate baseline measurements for interference detection | [10] [9] |

| Protein Standards (e.g., BSA) | Model system for interference studies | Useful for demonstrating interference effects in biological contexts | [1] |

| Holmium Oxide Filters | Wavelength accuracy verification | Validates instrument performance during interference studies | [9] |

| Absorption Filters | Stray light reduction | Improves measurement accuracy by eliminating unwanted wavelengths | [6] |

Mechanism of Refractive Index-Assisted Interference Detection

The following diagram illustrates how refractive index-assisted detection works to identify and correct spectral interference:

Technical support center for UV-Vis spectrophotometry

This guide helps you identify and overcome common spectral interferents in biological samples to ensure the accuracy of your UV-Vis spectrophotometric analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Correcting Common Interferences

| Interferent Type | Primary Effect on UV-Vis Analysis | Recommended Correction Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Absorbance at 220 nm & 280 nm due to tyrosine, tryptophan, phenylalanine [11] | Colorimetric assays (e.g., Folin-Ciocalteu) for wavelength shift [11]; Sample dilution; Background subtraction [2] | Direct UV measurement is prone to interference from other matrix components [11]. |

| Nucleic Acids | Strong absorbance at 260 nm [12] | Specific dye-binding assays; Baseline correction methods [13] | Check for contamination in protein samples and vice versa. |

| Particulates & Aggregates | Light scattering (Rayleigh & Mie), leading to inflated/ inaccurate absorbance readings [13] | Centrifugation or filtration; Derivative spectroscopy [2]; Curve-fitting baseline subtraction [13] | Sonication can induce leaching from plastic tubes, creating particulates [14]. |

| Leached Chemicals | Absorption at 220 & 260 nm from plasticizers in microtubes [14] | Use high-quality plastics; Avoid high-temp exposure & sonication in plastic; Use glass/quartz where possible [14] | Leaching is ubiquitous across commercial brands and worsened by heat and sonication [14]. |

| General Background | Broad, non-specific absorbance across wavelengths [2] | Isoabsorbance (2-point) correction; Three-point correction for non-linear background; Derivative spectroscopy [2] | Method choice depends on the number of interferents and nature of the background signal [2]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Eliminating Protein Interference with a Colorimetric Method

This method is adapted from a study quantifying Rivastigmine Tartrate (RT) in biological matrices like rat skin, brain, and plasma. The Folin-Ciocalteu reagent reacts with amine groups, creating a bluish-green chromogen that shifts the measurement to the visible range, away from protein's UV absorbance [11].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent: Creates the colored complex with the target analyte [11].

- Sodium Carbonate: Provides the basic medium required for the reaction [11].

- Acetonitrile or Methanol: Used as organic solvents for efficient protein precipitation and drug extraction from tissues [11].

- Microvolume UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: Allows measurement of small sample volumes [11].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize biological tissue (e.g., skin, brain) in a suitable buffer. Pre-treat samples with a protein precipitating agent. The study found a ZnSO:ACN (1 M:ACN, 10:90 v/v) mixture at a 0.5:1 ratio (precipitant/plasma) effective for plasma samples [11].

- Drug Extraction: Add a volume of acetonitrile or methanol to the homogenate, vortex mix, and centrifuge to precipitate proteins and extract the drug into the organic solvent layer. The recovery improves with larger solvent volumes [11].

- Reaction: Mix the processed sample supernatant with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and sodium carbonate in a predetermined ratio [11].

- Measurement: Incubate the mixture and measure the absorbance in the visible range (e.g., 500-750 nm, depending on the chromogen). The wavelength shift avoids interference from proteins that absorb in the UV region [11].

- Validation: The method should be validated for parameters like specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, LOD, and LLOQ as per ICH guidelines [11].

Protocol 2: Correcting for Light Scattering from Particulates

This method uses a curve-fitting approach to subtract the baseline artifact caused by light scattering from particulates or large aggregates, providing a more accurate concentration measurement [13].

Materials & Reagents:

- High-Quality Quartz Cuvettes: Minimize intrinsic light scattering.

- Ultracentrifuge or 0.02 μm Filter: For physical removal of particulates (if sample volume and stability permit).

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Obtain a full UV-Vis absorbance spectrum of your sample, ensuring the absorbance values are within the instrument's linear dynamic range.

- Baseline Modeling: Fit a baseline to the scattering contribution in your sample spectrum using fundamental Rayleigh and Mie scattering equations. Rayleigh scattering intensity is proportional to λ^(-4), while Mie scattering has a more complex wavelength dependence [13].

- Subtraction: Subtract the modeled scattering baseline from the measured sample spectrum.

- Quantification: Use the corrected absorbance spectrum for concentration determination via Beer-Lambert's law. This method has been validated against protein aggregates and polystyrene nanospheres [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My blank buffer reads fine, but my biological sample has a very high, sloping baseline. What is the cause? This is a classic sign of light scattering caused by particulates or large, insoluble aggregates (e.g., protein aggregates) in your sample. The scattering effect is more pronounced at shorter wavelengths, creating a baseline that slopes downward as wavelength increases [13]. Solutions include centrifuging or filtering your sample, or applying a scattering correction algorithm if your instrument software supports it [13] [2].

Q2: I am getting inconsistent nucleic acid concentrations from my samples, even when using the same stock. What could be wrong? A common but often overlooked source of interference is the leaching of chemicals from plastic microtubes. Normal handling, especially techniques involving heat (≥37°C) or sonication, can cause light-absorbing chemicals (200-1400 Da) to leach into your sample, contributing to the absorbance at 260 nm [14]. To mitigate this, try using high-quality, low-binding tubes, avoid exposing tubes to high temperatures, and where possible, use glass or quartz vessels for critical measurements.

Q3: How can I specifically quantify a small molecule drug in a protein-rich matrix like plasma without using HPLC? You can employ a colorimetric method that shifts the analyte's absorption wavelength. For instance, a method using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent can be developed for compounds with amine groups. This reaction produces a colored complex measured in the visible spectrum, effectively avoiding the strong UV absorption interference from proteins in the matrix [11]. This approach is cost-effective and suitable for routine analysis.

Q4: My sample is turbid, and I cannot clarify it by centrifugation or filtration without losing my analyte. How can I get an accurate concentration? In situations where physical clarification is not an option, derivative spectroscopy is a powerful tool. By taking the second derivative of your absorbance spectrum, the sharp peaks of your analyte can be distinguished from the broad, sloping background caused by scattering. The amplitude of the derivative peak is then proportional to concentration and is largely unaffected by the scattering background [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Spectral Interference from Impurities

Problem: Inaccurate concentration measurements due to unknown impurities in the sample that absorb light in the same spectral region as your analyte.

Explanation: The Beer-Lambert Law assumes that only the analyte of interest contributes to absorbance. However, the presence of absorbing impurities causes deviation from the ideal behavior, as the measured total absorbance ((A{total})) is the sum of the analyte's absorbance ((A{analyte})) and the impurities' absorbance ((A_{impurities})) [1]. Even minute quantities of an impurity with a high molar absorptivity can cause large errors [1].

Symptoms:

- The calculated concentration of your analyte is consistently and inexplicably higher than expected.

- The absorption spectrum of your sample has an unusual shape or unexpected peaks.

- Measurements lack reproducibility when sample composition varies slightly.

Solution Steps:

- Verify the Issue: Compare the UV-Vis spectrum of your test sample with a spectrum of a pure standard of your analyte. Look for shoulders on peaks, broadening of peaks, or changes in the wavelength of maximum absorption ((\lambda_{max})).

- Perform a Baseline Correction: Always run a blank that contains the solvent and all expected matrix components except the analyte [15]. This helps correct for baseline noise and drift.

- Use Standard Addition: If impurity interference is suspected, use the method of standard addition. This involves adding known quantities of the pure analyte to the sample and measuring the change in absorbance. This method can compensate for matrix effects [16].

- Employ Mathematical Corrections: For advanced users, techniques like derivative spectroscopy can help resolve overlapping peaks from multiple absorbing species [15].

- Validate with a Second Technique: As proposed in recent research, combine UV-Vis spectrophotometry with constrained refractometry. A significant disagreement in concentration determined by the two techniques indicates the presence of unaccounted impurities [1].

Prevention:

- Ensure rigorous sample purification before analysis.

- Use high-purity solvents and reagents.

- Characterize your sample matrix thoroughly to identify potential interferents.

Guide 2: Addressing Non-Ideal Physical Effects: Scattering and Stray Light

Problem: Reduced accuracy due to light scattering (from particulates or aggregates) or stray light within the instrument, which leads to a loss of transmitted light that is misinterpreted as analyte absorption.

Explanation: The Beer-Lambert Law holds for true absorption. Light scattering from particulates or large molecules (like protein aggregates) causes a similar attenuation of the transmitted beam but does not follow the same concentration relationship [13]. Stray light, caused by reflections or imperfections in the instrument, reaches the detector without passing through the sample, violating a core assumption of the law [15].

Symptoms:

- Apparent absorbance is higher at lower wavelengths due to Rayleigh scattering.

- Negative absorbance values or a non-linear calibration curve, especially at high absorbance values.

- Poor linearity at high sample concentrations.

Solution Steps:

- Clarify Your Sample: For solutions, filter or centrifuge to remove particulates. Use a 0.2 µm or 0.45 µm syringe filter compatible with your solvent [15].

- Check Instrument Optics: Regularly clean the exterior of cuvettes and ensure the instrument's optical compartments are free of dust and contaminants [15].

- Test for Stray Light: Use certified cutoff filters. The measured transmittance should be less than 0.001% (absorbance >5) at wavelengths below the cutoff. Higher than expected transmittance indicates stray light [15].

- Apply Scattering Corrections: For known scatterers like protein aggregates, use a curve-fitting baseline subtraction approach based on Rayleigh and Mie scattering equations to correct the spectrum [13].

Prevention:

- Always use clean, high-quality cuvettes.

- Follow a regular instrument maintenance and calibration schedule.

- Ensure samples are fully dissolved and homogeneous.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My calibration curve is no longer linear. Has the Beer-Lambert Law failed? A: The Beer-Lambert Law is a limiting law that holds for a specific concentration range. Non-linearity at higher concentrations is a common limitation [17]. Ensure your sample concentrations fall within the linear dynamic range of your instrument and method. Other causes include chemical associations, refractive index changes, or the instrumental issues described in the troubleshooting guides above.

Q2: How much can a small impurity actually affect my concentration measurement? A: The error can be substantial. Research has shown that an impurity constituting just 1% of the sample by volume can lead to an error of over 50% in the calculated concentration of the primary analyte if the impurity has a much higher molar absorptivity [1]. The error is a function of the ratio of the molar absorptivities ((\epsilon)) and the ratio of the concentrations [1].

Q3: What is the difference between Absorbance (A) and Optical Density (OD)? Should I be using AU on my graphs? A: Absorbance (A) is the preferred, dimensionless term defined by the negative log of transmittance. Optical Density (OD) is a historical term that is synonymous with absorbance but its use is now discouraged [18]. While many instruments output "AU" (Absorbance Units), this is redundant because absorbance is inherently unitless. Best practice is to simply label the axis "Absorbance" [19] [18].

Q4: My sample is very concentrated, and the absorbance is off the scale. What can I do? A: For accurate quantitation, absorbance values should be kept below 1.0 [6]. You have two main options:

- Dilute the sample: This is the most common approach. Ensure the solvent is consistent and the dilution is accurate.

- Use a shorter pathlength cuvette: Switch from a standard 1 cm cuvette to one with a 1 mm or even 0.1 mm pathlength [6]. This reduces the effective distance light travels through the sample, lowering the measured absorbance.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Refractive Index-Assisted Analysis for Detecting Impurity Interference

This protocol is based on a published methodology for combining UV-Vis spectrophotometry and refractometry to detect and mitigate errors from spectral interference [1].

Objective: To determine the concentration of an analyte (e.g., Benzene) in a non-aqueous solution (e.g., Cyclohexane) and detect/quantify the error caused by a spectrally interfering impurity (e.g., N,N-Dimethylaniline, NND).

Key Materials:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-2600) with quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length).

- Refractometer (e.g., ATAGO RX-7000i).

- High-purity solvents and analytes.

Procedure:

- UV-Vis Calibration:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of pure Benzene in Cyclohexane across a suitable concentration range.

- Record the UV absorption spectrum for each standard, noting the absorbance at a specific wavelength (e.g., 255 nm).

- Construct a calibration curve of absorbance versus concentration.

- Refractometry Calibration:

- Using the same standard solutions, measure the refractive index of each.

- Construct a separate calibration curve of refractive index versus Benzene concentration.

- Analysis of "Impure" Sample:

- Prepare a test sample containing Benzene in Cyclohexane with a small, known amount (e.g., 1% by volume) of NND.

- Measure the UV absorbance and refractive index of this test sample.

- Concentration Calculation & Comparison:

- Calculate the Benzene concentration using the UV-Vis calibration curve ((C{UV})).

- Calculate the Benzene concentration using the refractometry calibration curve ((C{RI})).

- A significant discrepancy between (C{UV}) and (C{RI}) indicates spectral interference. The value from refractometry is often closer to the true value when the analyte is the major component [1].

Quantitative Error Data

The table below summarizes the type and magnitude of errors that can be introduced by common experimental challenges.

Table 1: Common Quantification Errors and Their Impact

| Error Source | Example Scenario | Reported Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Interference | 1% (v/v) NND impurity in a Benzene/Cyclohexane solution. | ~53% overestimation of Benzene concentration via UV-Vis. | [1] |

| Spectral Interference | 1% DNA contamination in a BSA protein solution (A280). | 26.3% error in BSA concentration determination. | [1] |

| High Absorbance | Taking measurements where A > 1. | Reduced detector sensitivity and reliability; non-linear response. | [6] |

| Light Scattering | Rayleigh/Mie scattering from protein aggregates or particulates. | Inaccurate concentration measurements requiring specialized correction equations. | [13] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Reliable UV-Vis Analysis

| Material / Reagent | Function / Rationale | Critical Specifications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis analysis. | Transparent down to ~200 nm; standard 1 cm pathlength. | [6] |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolving analyte for measurement. | Low UV-Vis absorbance in the spectral region of interest (e.g., HPLC grade). | [15] |

| Certified Reference Materials | For instrument wavelength and absorbance calibration. | Known spectral properties (e.g., Holmium Oxide filter for wavelength calibration). | [15] |

| Syringe Filters | Clarification of samples prior to analysis. | 0.2 µm or 0.45 µm pore size; solvent-compatible material (e.g., Nylon, PTFE). | [15] |

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Diagram: Diagnosing Impurity Interference

The following workflow provides a logical path for diagnosing and addressing quantification errors.

Diagram: Refractive Index-Assisted Verification Workflow

This diagram outlines the experimental protocol for using refractometry to verify UV-Vis results.

The development of Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers (HBOCs) as red blood cell substitutes is a pressing need in biomedicine, aimed at addressing limitations of donor blood such as short shelf life, compatibility screening, and infection risks [20]. The accurate characterization of HBOCs—including precise measurement of hemoglobin (Hb) content, encapsulation efficiency, and yield—is crucial for confirming their ability to deliver adequate oxygen once administered and for ensuring economic viability [20]. Underestimation of free hemoglobin could lead to oversight of severe adverse effects like renal toxicity and vasoconstriction, while overestimation might raise unfounded concerns or unnecessarily terminate development programs [20].

UV-Vis spectrophotometry represents a cornerstone technique for hemoglobin quantification due to its widespread use, rapidity, and accessibility [20]. However, researchers face significant challenges with spectral interference when analyzing complex HBOC formulations, particularly those involving encapsulation systems or carrier components that may scatter light or absorb at similar wavelengths as hemoglobin [20]. This technical support document addresses these challenges through targeted troubleshooting guides and methodological recommendations to ensure accurate, reliable hemoglobin quantification in HBOC development.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common UV-Vis Spectroscopy Issues in HBOC Analysis

Sample Preparation and Measurement Problems

Q: What are the most common sample-related issues affecting hemoglobin quantification accuracy?

A: Sample problems represent the most frequent source of error in hemoglobin quantification. The following table summarizes key issues and their solutions:

Table 1: Troubleshooting Sample Preparation and Measurement Issues

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected peaks in spectrum | Contaminated cuvettes or samples | Thoroughly wash cuvettes with appropriate solvents; prepare fresh samples | Handle cuvettes with gloved hands; use clean labware [3] |

| Absorbance values too high (outside linear range) | Sample concentration too high | Dilute sample or use shorter path length cuvette | Keep absorbance values below 1 for reliable quantification [6] |

| Low signal intensity | Sample volume insufficient or beam misalignment | Ensure adequate volume so excitation beam passes through sample | Use appropriate cuvette size; verify beam alignment [3] |

| Inconsistent replicate measurements | Sample evaporation or degradation | Seal samples; work in temperature-controlled environment | Perform measurements quickly; use fresh preparations [3] |

| Light scattering interference | Particulate matter or HBOC carrier components | Filter samples; use reference correction methods | Centrifuge samples before measurement; use integratiοn spheres [21] |

Q: How does the choice of cuvette material impact hemoglobin measurements in the UV range?

A: Cuvette material selection is critical for accurate hemoglobin measurements:

- Plastic cuvettes: Generally inappropriate for UV measurements as plastic absorbs UV light [6]

- Glass cuvettes: Absorb most UVC (100-280 nm) and UVB (280-315 nm) light, allowing only some UVA (315-400 nm) transmission [6]

- Quartz cuvettes: Required for full UV range analysis as quartz is transparent to most UV light [6]

- Specialized setups: Necessary for wavelengths shorter than 200 nm, typically requiring argon-purged systems to eliminate oxygen absorption [6]

Methodological and Interference Challenges

Q: What methodological factors can lead to inaccurate hemoglobin quantification in HBOC systems?

A: Beyond sample issues, methodological approaches and instrumental factors significantly impact result accuracy:

Table 2: Methodological and Interference Challenges in Hemoglobin Quantification

| Challenge | Impact on Quantification | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Carrier component interference | Excipients or encapsulation materials absorb at measurement wavelengths | Analyze absorbance spectrum before method selection; use background subtraction [20] |

| Light scattering by particles | HBOC suspensions scatter light, causing artificially high absorbance readings | Use collimated transmission measurements; apply Mie scattering corrections [21] |

| Methemoglobin formation | Altered absorption spectrum affects quantification accuracy | Use spectral deconvolution methods to determine metHb content [22] [21] |

| Protein contaminants | Non-specific methods measure all proteins, not just hemoglobin | Employ hemoglobin-specific methods (SLS-Hb, CN-Hb) rather than general protein assays [20] |

| Oxygen interference | Atmospheric oxygen absorbs in UV range, particularly below 250 nm | Use argon-purged systems for deep UV work; apply oxygen correction algorithms [23] [6] |

Q: How can researchers address the hematocrit effect in dried blood spot analysis for hemoglobin normalization?

A: The hematocrit effect represents a significant challenge for dried blood spot (DBS) analysis, affecting metabolite quantification through several mechanisms: blood viscosity variations, extraction efficiency differences, and matrix effects [24]. Recent comparative studies demonstrate that:

- Hemoglobin normalization outperforms other methods (potassium concentration, spot weight, total protein) for standardizing DBS metabolomics data [24]

- Hemoglobin-based correction effectively reduces intragroup variability and improves classification accuracy in metabolic studies [24]

- Alternative approaches including spot weight and potassium measurement show inconsistent performance across different metabolite classes [24]

Method Selection Guide: Comparative Evaluation of Hemoglobin Quantification Methods

UV-Vis Spectroscopy-Based Methods

Q: Which hemoglobin quantification method is most appropriate for HBOC characterization?

A: A recent comprehensive evaluation of UV-Vis spectroscopy-based methods provides clear guidance for method selection:

Table 3: Comparative Evaluation of UV-Vis Spectroscopy-Based Hemoglobin Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Specificity for Hb | Key Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLS-Hb | Forms complex with sodium lauryl sulfate | High | Specific, cost-effective, safe, high accuracy/precision, easy to use [20] | Potential interference from detergents | Preferred method for most HBOC applications [20] |

| Cyanmethemoglobin (CN-Hb) | Converts Hb to cyanmethemoglobin | High | Well-established, standardized | Uses toxic cyanide reagents, safety concerns [20] | Use with strict safety protocols when required |

| BCA Assay | Copper reduction in alkaline medium | Low (measures total protein) | Sensitive, compatible with additives | Not Hb-specific, susceptible to interference [20] | Only if absence of other proteins confirmed |

| Bradford (Coomassie Blue) | Dye binding to proteins | Low (measures total protein) | Rapid, simple procedure | Not Hb-specific, nonlinear response [20] | Only if absence of other proteins confirmed |

| Absorbance at Soret peak (~414 nm) | Direct Soret band measurement | Medium | Direct measurement, no reagents needed | Affected by Hb oxidation state, light scattering [20] | Qualitative assessment, not quantification |

| Absorbance at 280 nm | Aromatic amino acid absorption | Very low (measures all proteins) | Simple, no additional reagents | Not Hb-specific, strong interference from other components [20] | Not recommended for HBOC characterization |

Q: Why is the SLS-Hb method recommended as the preferred approach for HBOC characterization?

A: The sodium lauryl sulfate hemoglobin (SLS-Hb) method emerges as the preferred choice due to its optimal balance of specificity, safety, and practicality [20]:

- Specificity: Effectively quantifies hemoglobin without significant interference from common HBOC components

- Safety: Eliminates the need for toxic cyanide reagents required in traditional cyanmethemoglobin methods [20]

- Practicality: Demonstrates high accuracy and precision across different hemoglobin concentration levels [20]

- Cost-effectiveness: Utilizes inexpensive, readily available reagents compared to specialized kits

Advanced and Specialized Methods

Q: What advanced techniques are available for challenging HBOC characterization scenarios?

A: For particularly complex scenarios, several advanced methods offer specialized capabilities:

Spectral Extinction Measurements with Multivariate Analysis This robust optical method enables simultaneous determination of oxyhemoglobin, deoxygenated hemoglobin, and methemoglobin content in particle-based HBOC systems without requiring dissolution [22] [21]. The approach measures collimated transmission spectra between 300-800 nm and applies numerical methods to determine composition based on wavelength-dependent refractive indices, which represent superpositions of different hemoglobin states [21].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods provide exceptional specificity for hemoglobin analysis, particularly for detecting specific modifications or variants [25] [26]. The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) has established a mass spectrometry-based reference method for HbA1c measurement, highlighting the technique's precision [26]. While less accessible for routine analysis due to complexity and cost, MS methods offer unparalleled specificity for challenging interference scenarios [26].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Hemoglobin Quantification

Q: What key reagents and materials are essential for reliable hemoglobin quantification in HBOC research?

A: The following research reagents and materials form the foundation of accurate hemoglobin quantification:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Hemoglobin Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) | Forms stable complex with hemoglobin for SLS-Hb method [20] | Preferred over toxic cyanide-based reagents; ensures researcher safety |

| Quartz cuvettes | Sample containment for UV-Vis measurements | Essential for UV range analysis; standard 1 cm path length most common [6] |

| Phosphate buffer (neutral pH) | Sample dissolution and dilution | Maintains hemoglobin stability; prevents methemoglobin formation |

| Enzymatic digestion reagents | Protein digestion for mass spectrometry analysis | Trypsin or endoproteinase Glu-C for specific peptide generation [26] |

| Hemoglobin standards | Calibration curve preparation | Purified human or bovine hemoglobin for quantitative accuracy |

| BCA or Bradford reagents | Total protein quantification (when appropriate) | Use only when absence of other proteins confirmed [20] |

| Gas exchange systems | Oxygenation/deoxygenation studies | For functional analysis of oxygen binding capacity |

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Methodologies

SLS-Hb Method Protocol

Q: What is the detailed experimental protocol for the recommended SLS-Hb quantification method?

A: The following protocol provides reliable hemoglobin quantification using the SLS-Hb method:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare SLS reagent solution in appropriate buffer (concentration typically 0.1-0.5%)

- Standard Curve Preparation:

- Prepare serial dilutions of hemoglobin standard in the concentration range of 0-2 mg/mL

- Use the same buffer as employed for sample preparation

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute HBOC samples to fall within the standard curve range

- For encapsulated systems, may require preliminary disruption to release hemoglobin

- Measurement:

- Mix equal volumes of sample/standard with SLS reagent

- Incubate for specified time (typically 5-15 minutes)

- Measure absorbance at appropriate wavelength (typically 540-560 nm)

- Calculation:

- Generate standard curve from absorbance values of standards

- Calculate sample concentrations from linear regression equation

Spectral Extinction Method for HBOC Particles

Q: How is the spectral extinction method implemented for particle-based HBOC systems?

A: For characterizing hemoglobin microparticles (HbMPs), the spectral extinction measurement follows this workflow:

Spectral Extinction Workflow for HbMP Analysis

This method enables simultaneous determination of multiple hemoglobin states in particulate systems where conventional approaches fail due to light scattering [21].

FAQs: Advanced Topics in Hemoglobin Quantification

Q: How can researchers distinguish between actual hemoglobin content and interference from light scattering in particle-based HBOCs?

A: Distinguishing true hemoglobin content from scattering artifacts requires specialized approaches:

- Implement collimated transmission measurements to minimize scattering contributions [21]

- Apply Mie scattering theory or T-matrix methods to model and correct for scattering effects [21]

- Use spectral deconvolution algorithms that leverage the entire absorbance spectrum rather than single wavelengths [22]

- Validate with reference methods such as X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for iron content or enzymatic digestion followed by spectrophotometry [21]

Q: What strategies exist for dealing with methemoglobin interference in functional HBOC characterization?

A: Methemoglobin interference can be addressed through:

- Spectral decomposition methods that mathematically separate contributions from different hemoglobin species based on their distinct absorption profiles [22] [21]

- Chemical reduction techniques that convert methemoglobin back to functional hemoglobin before measurement

- Multivariate calibration models that incorporate methemoglobin as a distinct component in quantification algorithms

- Functional testing including oxygen binding curves to confirm biological activity beyond mere concentration measurements

Q: How does hemoglobin quantification for HBOC development differ from clinical hemoglobin testing?

A: HBOC development presents unique challenges not encountered in clinical testing:

- Matrix complexity: HBOC formulations include encapsulation materials, cross-linkers, and excipients that interfere with standard assays [20]

- Concentration range: HBOC processing involves extreme concentrations not encountered in clinical samples

- Speciation requirements: Must distinguish between oxygenated, deoxygenated, and methemoglobin states for functional assessment [21]

- Regulatory considerations: Method validation must meet pharmaceutical development standards rather than clinical diagnostic requirements

- Stability assessment: Requires monitoring hemoglobin integrity throughout manufacturing and storage under various conditions

In UV-Vis spectrophotometry, the accuracy of quantitative and qualitative analysis depends on the stability and reproducibility of spectral data. Environmental factors—specifically pH, temperature, and conductivity—constitute significant sources of spectral interference that can compromise data integrity. These parameters influence molecular electronic transitions, alter solvent-solute interactions, and introduce light scattering effects, leading to deviations from the Beer-Lambert law. Within a thesis focused on overcoming spectral interference, understanding these influences is paramount for developing robust analytical methods, particularly in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development where method validation requires demonstration of robustness against such variables. This guide provides researchers with a systematic framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and compensating for these interferents to ensure spectral accuracy.

Quantitative Effects of Environmental Factors

The individual and combined effects of pH, temperature, and conductivity on UV-Vis spectra are quantifiable. The following table summarizes the primary influences of each factor, based on experimental observations from water quality analysis and fundamental spectroscopic studies [27] [28] [29].

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Environmental Factors on UV-Vis Spectra

| Environmental Factor | Primary Spectral Effects | Underlying Mechanism | Typical Magnitude of Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Alteration of absorption peak position (λmax) and absorption coefficient (ε) [27]. | Changes in protonation state of chromophores, affecting electronic energy levels and π→π* / n→π* transitions [28]. | Significant; can cause bathochromic or hypsochromic shifts of several nanometers. |

| Temperature | Change in absorbance intensity and waveform of the spectrum [27] [29]. | Alters molecular energy distribution, collision frequency, and solvent density, affecting equilibrium positions and reaction rates [29]. | Increased temperature can decrease absorbance; temperature fluctuations cause non-reproducible results [29]. |

| Conductivity | Introduction of baseline shifts and increased spectral noise [27]. | Soluble inorganic ions (e.g., Na+, K+, Cl-) cause light scattering and absorption, particularly in the UV region [27]. | High conductivity can lead to significant baseline drift and signal instability. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigation and Compensation

Protocol 1: Systematic Investigation of Individual Factor Effects

This methodology outlines the procedure for characterizing the individual effect of each environmental factor on a sample's UV-Vis spectrum.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the analyte at a concentration that yields an absorbance within the linear range of the Beer-Lambert law (ideally 0.2–1.0 AU) [28].

- Baseline Measurement: Acquire the UV-Vis spectrum of the pure solvent (blank) under controlled reference conditions (e.g., pH 7.0, 25°C, low conductivity).

- Factor Variation:

- For pH: Aliquot the stock solution and adjust each aliquot to a different pH value using small volumes of acid (e.g., HCl) or base (e.g., NaOH). Measure the UV-Vis spectrum at each pH [27].

- For Temperature: Place the sample cuvette in a thermostatted holder. Acquire spectra at a series of temperatures (e.g., 10°C, 20°C, 30°C, 40°C), allowing sufficient time for temperature equilibration at each step [27] [29].

- For Conductivity: Add progressively higher concentrations of a non-absorbing salt (e.g., KCl) to aliquots of the stock solution. Measure the spectrum after each addition [27].

- Data Analysis: Plot the changes in key spectral features (e.g., absorbance at λmax, shift in λmax, baseline slope) against the varied parameter (pH, temperature, conductivity) to establish a quantitative relationship.

Protocol 2: Data Fusion for Multi-Factor Compensation

For complex samples where multiple factors vary simultaneously, a data fusion approach can simultaneously compensate for their combined interference. This method integrates spectral data with sensor measurements of environmental parameters into a single predictive model [27].

- Data Collection: For a large set of calibration samples (n > 100 is recommended), collect both the UV-Vis spectrum and the concurrent values of pH, temperature, and conductivity [27].

- Feature Extraction: From the full spectrum, identify the feature wavelengths most relevant to the analyte of interest (e.g., using genetic algorithms or successive projections algorithm).

- Model Development: Fuse the spectral data (absorbance at feature wavelengths) with the measured environmental factors (pH, temperature, conductivity) into a single data matrix.

- Multivariate Modeling: Use a chemometric method such as Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build a calibration model that predicts the target parameter (e.g., Chemical Oxygen Demand) from the fused data matrix [27].

- Validation: Validate the model with an independent prediction set. Research has demonstrated that this approach can achieve a high coefficient of determination (R²Pred) of 0.96, significantly outperforming models using spectral data alone [27].

The following workflow diagrams the process of investigating environmental interference and implementing the data fusion compensation strategy.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Environmental Interference

Q1: My sample's absorbance readings are drifting over time. What could be the cause? A: Drifting absorbance is a classic symptom of temperature instability [29]. Ensure the spectrometer lamp has warmed up for the recommended time (20+ minutes for halogen/tungsten lamps) and that your sample is thermally equilibrated. Use a thermostatted cuvette holder for critical measurements. Drift can also be caused by evaporation of solvent, which increases analyte concentration; always seal cuvettes for long measurements [3].

Q2: Why do I see unexpected peaks or a shifting baseline in my spectrum? A: This is often related to pH sensitivity or high conductivity [27] [28]. First, verify that your sample and blank are at the same, buffered pH. Unexpected peaks can indicate a change in the protonation state of your analyte. A noisy or shifting baseline can be caused by light scattering from particulate matter or high ion concentration (conductivity). Filtering your sample can resolve scattering issues [28].

Q3: My calibration curve is non-linear even at what should be acceptable absorbance levels. How can I fix this? A: While high concentration is a common cause, environmental factors can also induce non-linearity. A pH difference between standards and samples can cause deviations if the analyte's absorptivity is pH-dependent. Ensure all standards and samples are in an identical buffer matrix. For ionic analytes, match the conductivity of the background electrolyte to minimize electrostatic effects [27] [28].

Q4: How can I compensate for environmental interference without physically controlling each factor? A: When strict control is impractical, the data fusion method is a powerful software-based compensation technique. By building a calibration model that includes environmental factors (pH, T, conductivity) as variables alongside spectral data, the model can mathematically correct for their influence, significantly improving prediction accuracy [27].

Q5: My sample is cloudy. How does this affect the measurement, and what can I do? A: Cloudy samples scatter light, violating a core assumption of the Beer-Lambert law and leading to erroneously high absorbance readings. This is a matrix effect related to the sample's physical state. The best solution is to clarify the sample by filtration or centrifugation before measurement. If that is not possible, using a shorter pathlength cuvette can reduce the scattering effect [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and instruments required for conducting rigorous studies on environmental interference in UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| pH Buffer Solutions | To calibrate pH meters and maintain stable pH during spectral acquisition. | Use buffers with low UV absorbance in your wavelength range (e.g., phosphate, borate). |

| Thermostatted Cuvette Holder | To control and maintain a constant sample temperature, eliminating drift. | Essential for studying temperature effects and for obtaining reproducible kinetics data. |

| High-Purity Solvents | For preparing sample and blank solutions. | Ensure solvents are spectrophotometric grade and transparent in the spectral region of interest. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | To hold liquid samples in the light path. | Quartz is transparent down to ~190 nm. Ensure they are clean and free of scratches [3]. |

| Non-Absorbing Salts (e.g., KCl) | To systematically study the effect of conductivity on spectra. | Allows for the creation of calibration samples with varying ionic strength without introducing new chromophores [27]. |

| Multi-Factor Portable Meter | To simultaneously measure pH, temperature, and conductivity of samples immediately before or after spectral acquisition. | Critical for collecting the environmental data required for the data fusion compensation model [27]. |

Advanced Techniques and Chemometric Solutions for Complex Samples

Refractive Index-Assisted UV-Vis for Error Reduction in Contaminated Samples

Spectral interference from contaminants is a fundamental challenge that limits the reliability of UV-Vis spectrophotometry in complex samples. When impurities absorb light in the same spectral region as your target analyte, they cause significant concentration determination errors. Research demonstrates that refractive index (RI)-assisted UV-Vis spectrophotometry provides a robust solution to this problem, detecting and reducing errors from unknown contaminants where traditional mathematical corrections fall short [1].

This technique operates on a powerful principle: while molar absorptivities vary dramatically across compounds (leading to large errors from minor contaminants in UV-Vis), the refractive indices of most liquids occupy a narrow range (1.3-1.6) [1]. By combining both measurements, researchers can identify discrepant results that indicate contamination and obtain more reliable concentration values even without knowing the exact nature of the impurities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles

How does refractive index assistance actually reduce errors in UV-Vis measurements? The method uses constrained refractometry (refractometry in solvents with refractive indices within predefined limits) to provide an independent concentration measurement. Large disagreements between UV-Vis and RI results signal significant spectral interference. The RI measurement itself remains relatively unaffected by minor impurities because most liquids have refractive indices within a narrow 1.3-1.6 range, unlike the highly variable molar absorptivities that cause major UV-Vis errors [1].

When should I consider using this combined technique? Implement refractive index-assisted UV-Vis when:

- Working with complex samples where complete impurity profiling is impractical

- Unknown contaminants may be present in your samples

- Traditional UV-Vis shows inconsistent or unexpectedly high concentration values

- Minimizing sample preparation time is critical for high-throughput applications [1] [4]

What are the limitations of this approach? Constrained refractometry has lower resolution and sensitivity compared to UV-Vis spectrophotometry. The technique is not applicable when your analyte of interest isn't the major component in the sample, and it requires careful solvent selection to ensure adequate refractive index difference between solvent and analyte [1].

Technical Implementation

What solvent properties are critical for successful implementation? The refractive index difference between solvent and analyte significantly influences error reduction. Research indicates that error in refractometry reduces when |μₐ - μₛ| is higher (where μ is defined in terms of refractive index as μ = (n²-1)/(n²+2)). For errors below 2% with impurity-to-analyte volume ratios below 1:100, the solvent's refractive index should differ from the analyte's by at least 0.15 units [1].

How do I handle samples with multiple potential interferents? The constrained refractometry approach provides a maximum error estimate even for multiple unknown impurities, as the collective impurity contribution remains bounded due to the narrow refractive index range of most liquids. The correlation between UV-Vis and RI measurements can help identify the major interferent through Pearson's correlation analysis [1] [30].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Suspected Spectral Interference from Unknown Contaminants

Symptoms:

- Unexplained peaks or shoulder peaks in UV-Vis spectra [3]

- Absorbance values that are higher than expected at specific wavelengths

- Inconsistent concentration readings between different analytical methods

- Poor reproducibility in standard curve generation

Solutions:

- Perform comparative analysis: Measure your sample using both UV-Vis spectrophotometry and constrained refractometry [1]

- Calculate discrepancy: Determine the percentage difference between the concentration values obtained from both techniques

- Interpret results: Discrepancies >5% typically indicate significant spectral interference requiring corrective action [1]

- Apply correction: Use the refractometry-derived concentration for greater accuracy, or employ the correlation method to identify major interferents

Problem: Excessive Noise or Fluctuation in Measurements

Symptoms:

- Unstable baseline during UV-Vis measurements

- Fluctuating refractive index readings

- Poor signal-to-noise ratio in spectra

Solutions:

- Ensure adequate warm-up time (20 minutes for tungsten halogen or arc lamps) [3]

- Verify all connections and cables in modular systems [3]

- Check for evaporation effects that may concentrate your sample during extended measurements [3]

- Confirm proper alignment of all optical components [3]

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

Symptoms:

- High variability in technical replicates

- Poor standard curve linearity

- Unexplained concentration variations

Solutions:

- Maintain consistent sample temperature throughout measurements [3]

- Ensure uniform sample positioning in the beam path [3]

- Verify cuvette cleanliness and integrity [3] [31]

- Confirm solvent compatibility with measurement cells (some solvents dissolve plastic cuvettes) [3]

Experimental Protocols

Core Methodology: Refractive Index-Assisted UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

Principle This protocol detects and corrects spectral interference by comparing concentration determinations from UV-Vis spectroscopy and constrained refractometry. The significant variance in molar absorptivity across compounds means minor contaminants can cause substantial UV-Vis errors, while the narrow refractive index range of most liquids makes RI measurements more robust to minor impurities [1].

Materials Required

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-2600) with quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length)

- Refractometer with high precision (least count ~1×10⁻⁵ units), such as RX-7000i (ATAGO)

- Appropriate solvent with known refractive index differing from analyte by ≥0.15 units

- Temperature control system (measurements at 20±0.01°C recommended) [1]

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Preparation

- Turn on instruments and allow lamps to warm up for recommended time (20 minutes for tungsten sources) [3]

- Set refractometer to controlled temperature (20±0.01°C)

- Prepare standard solutions of pure analyte in selected solvent

Standard Curve Generation

- Measure UV-Vis absorbance of standard solutions at analytical wavelength

- Measure refractive indices of standard solutions

- Create standard curves for both techniques (concentration vs. absorbance and concentration vs. refractive index)

Sample Analysis

- Measure UV-Vis spectrum of unknown sample

- Record absorbance at analytical wavelength

- Measure refractive index of the same sample solution

- Determine concentration from both standard curves

Interference Assessment

- Calculate percentage difference between concentrations from both methods:

- % Difference = |c(UV) - c(RI)| / [(c(UV) + c(RI))/2] × 100

- Differences >5% indicate significant spectral interference [1]

- Calculate percentage difference between concentrations from both methods:

Data Interpretation

Validation Experiment: Benzene in Cyclohexane with N,N-Dimethylaniline Interference

Objective Demonstrate error reduction in a controlled system with known interferent [1].

Experimental Design

- Prepare benzene solutions in cyclohexane (0.4 mL/L)

- Introduce N,N-Dimethylaniline (NND) impurity at 1% volume ratio (8 μL/L)

- NND has molar absorptivity ~70× higher than benzene at 255 nm [1]

Results and Performance

Table 1: Error Reduction in Benzene Analysis with NND Interference

| Method | Reported Concentration | Actual Concentration | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry at 255 nm | 0.614 mL/L | 0.4 mL/L | 53.4% |

| Constrained Refractometry | 0.408 mL/L | 0.4 mL/L | 2.0% |

Table 2: Application to Real-World Analytical Problems

| Application | Interferent | Interferent Concentration | UV-Vis Error | RI-Assisted Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (BSA) Concentration | DNA | 1% (w/w) | 26.3% | <2% |

| Salinity Measurement | Nitrates/Nitrites | <1 mg/L | Significant | <2% |

Conclusion The RI-assisted method reduced analytical error from 53.4% to 2% in this model system, demonstrating its powerful capability to overcome spectral interference even with high molar absorptivity contaminants [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Refractive Index-Assisted UV-Vis

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm path length, high UV transmission | Sample holder for UV-Vis measurements |

| Refractometer | High precision (∼1×10⁻⁵), temperature control | Accurate refractive index measurement |

| Deuterium Lamp | For UV region (190-400 nm) | UV light source for spectrophotometer |

| Tungsten Lamp | For visible region (400-800 nm) | Visible light source for spectrophotometer |

| Temperature Controller | ±0.01°C precision | Maintain constant temperature for RI measurements |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Low UV absorbance, known RI | Sample preparation with minimal interference |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for RI-Assisted UV-Vis Analysis

Conceptual Framework for Error Reduction

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Guide 1: Resolving Poor Model Predictive Performance

Problem: The Partial Least Squares (PLS) model shows high prediction errors during validation when quantifying multiple analytes with overlapping UV-Vis spectra.

Explanation: High prediction errors often occur due to uninformative wavelengths or overfitting. The Firefly Algorithm (FA) optimizes wavelength selection to build simpler, more robust models.

Solution:

- Implement Wavelength Selection with Firefly Algorithm: Integrate the FA to identify the most significant wavelengths for each analyte, reducing model complexity and improving prediction accuracy.

- Optimize FA Parameters: Systematically adjust the key parameters controlling the FA's behavior to ensure it finds a global optimum.

- Absorption coefficient (γ): Regulates light intensity and attractiveness. Optimize to control convergence speed.

- Randomization parameter (α): Provides random movement to help the search escape local optima. Tune to balance exploration and exploitation [32].

- Re-build PLS Model: Construct a new PLS model using only the wavelengths selected by the FA. Re-validate with an independent test set [32] [33].

Verification: Check for a lower Relative Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RRMSEP) and a reduced number of latent variables in the FA-optimized model compared to the full-spectrum PLS model [33].

### Guide 2: Handling Significant Spectral Overlap in Multi-Component Mixtures

Problem: The UV-Vis spectra of the target analytes heavily overlap, making it difficult for the PLS model to distinguish between them and leading to inaccurate quantification.

Explanation: PLS regression is specifically designed to handle collinearity and extract relevant information from complex, overlapping spectral data by projecting it into latent variables [32].

Solution:

- Ensure Proper Experimental Design: Construct your calibration set using a factorial design (e.g., fractional factorial or central composite design) that adequately captures the variation in mixture compositions. This typically requires 25-30 synthetic mixtures with varying concentration ratios [32] [34].

- Pre-process Spectral Data: Remove spectral regions with weak signals (e.g., above 370 nm) or potential interference (e.g., below 220 nm) before model development [32].

- Determine Optimal Latent Variables: Use cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out) to select the correct number of latent variables, preventing underfitting or overfitting [32].

- Apply Variable Selection: Use the Firefly Algorithm to further refine the model by selecting wavelengths that carry the most chemically relevant information, thereby resolving spectral interferences [32] [33].

### Guide 3: Addressing Suspected Spectral Interference from Unknown Impurities

Problem: The model's concentration predictions are inaccurate, and you suspect interference from unknown contaminants in the sample matrix.

Explanation: Even minute amounts of contaminants with high molar absorptivity can cause significant errors in UV-Vis spectrophotometry [1] [4].

Solution:

- Detect Interference with Refractometry: Use constrained refractometry as a complementary technique. Measure the refractive index of your sample and solvent.

- Compare and Analyze: A large discrepancy between the concentration determined by UV-Vis and the concentration estimated by refractometry indicates the presence of unaccounted spectral interferents.

- Reduce Error: If interference is confirmed, the refractometry data can provide a better quantitative estimate with a known maximum error, which is often comparable to the total impurity concentration [1] [4].

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the Firefly Algorithm used specifically for wavelength selection in PLS modeling?

The Firefly Algorithm (FA) is a nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimization technique. It improves PLS models by intelligently selecting a subset of wavelengths that are most relevant for predicting analyte concentrations. This process simplifies the model, reduces the risk of overfitting to noise, and enhances predictive performance by focusing on chemically significant spectral regions [32] [33] [34].

FAQ 2: What are the typical figures of merit used to validate a PLS-FA model?

The model should be validated using an independent test set in addition to cross-validation. Common figures of merit include [32]:

- Relative Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RRMSEP): Measures prediction accuracy.

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): Indicates the model's goodness of fit.

- Bias-Corrected RRMSEP (BCRRMSEP): Accounts for systematic error.

- Recovery and Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD): Assess accuracy and precision (intra-day and inter-day) as per ICH guidelines, with %RSD ideally below 2% [32] [34].

FAQ 3: My sample matrix is complex (e.g., pharmaceutical tablets or environmental water). Can the PLS-FA method still be applied?

Yes. The robustness of the PLS-FA method has been demonstrated in real-world applications, including the analysis of active ingredients in pharmaceutical tablets and antibiotics in tap water samples. Standard addition techniques can be used to assess and correct for matrix effects, ensuring selectivity and accuracy [32] [34].

FAQ 4: How does the greenness of this method compare to traditional chromatographic techniques?

UV-Vis spectrophotometry coupled with chemometric models is inherently greener than techniques like HPLC. It minimizes organic solvent consumption, reduces energy requirements, and generates less waste. This superior sustainability is quantitatively confirmed by high scores on dedicated assessment tools such as the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) [32] [33].

## Experimental Protocols

### Protocol 1: Standard Procedure for Developing a PLS Model with Firefly Algorithm Wavelength Selection

Application: Simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes with overlapping UV-Vis spectra.

Reagents and Materials:

- Reference Standards: High-purity analytes (e.g., Ciprofloxacin, Lomefloxacin, Enrofloxacin).

- Solvent: A suitable solvent such as distilled water, 10% aqueous acetic acid, or a green binary mixture (e.g., water:ethanol 1:1 v/v) [32] [35].

- Instrumentation: Double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-1800) with 1 cm quartz cells [32].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare individual stock solutions (e.g., 100 µg/mL) of each analyte in the chosen solvent.

- Dilute to working concentrations as needed.

- Experimental Design:

- Use a factorial design (e.g., a 3-factor, 5-level partial factorial design) to create a calibration set of 25-30 synthetic mixtures covering the expected concentration ranges [32] [34].

- Use a separate design (e.g., central composite design) to prepare an independent validation set of 15-20 mixtures [32].

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Record the UV-Vis spectra of all mixtures across a defined range (e.g., 200-400 nm) with a 1 nm interval.

- Export the spectral data and corresponding concentration data for chemometric processing (e.g., to MATLAB) [32].

- Initial PLS Model Development:

- Pre-process spectra by removing non-informative wavelength regions.

- Develop a full-spectrum PLS-1 model for each analyte.

- Use cross-validation to determine the optimal number of latent variables [32].

- Firefly Algorithm Optimization:

- Set the FA parameters (number of fireflies, generations, absorption coefficient γ, randomization parameter α) [32].

- Define the fitness function to minimize the root-mean-square error of the PLS model.

- Run the FA to identify the most informative wavelengths for each analyte.

- Final Model Building and Validation:

### Protocol 2: Procedure for Detecting and Quantifying Spectral Interference using Refractometry

Application: Detecting and correcting for errors caused by unknown absorbing impurities.

Reagents and Materials:

- Sample solution and pure solvent.

- Refractometer (e.g., ATAGO RX-7000i).

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer.

Procedure:

- UV-Vis Analysis:

- Record the UV-Vis spectrum of the sample.

- Calculate the analyte concentration (

c'_UV) using the pre-established calibration curve.

- Refractometry Analysis:

- Measure the refractive index of the pure solvent (

n_sol) and the sample solution (n_solution). - Ensure the solvent's refractive index differs from the analyte's by at least 0.15 units (constrained refractometry) [1].

- Use the Lorentz-Lorenz equation to calculate the analyte concentration (

c'_RI) based on refractive index change [1] [4].

- Measure the refractive index of the pure solvent (

- Interference Detection and Correction:

- Compare

c'_UVandc'_RI. A significant discrepancy indicates spectral interference. - The concentration from refractometry (

c'_RI) will have a maximum error that is predictable and often lower than the UV-Vis estimate in the presence of interferents. This value should be reported with the understood error margin [1].

- Compare

## Data Presentation

### Table 1: Performance Comparison of Full-Spectrum PLS and FA-PLS Models

Table comparing the performance of full-spectrum PLS and FA-PLS models for the simultaneous determination of various drugs, showing improvements in RRMSEP and model complexity with the Firefly Algorithm.

| Analyte Combination | Model Type | Number of Latent Variables | RRMSEP (%) | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosuvastatin, Pravastatin, Atorvastatin | Full-Spectrum PLS | 4, 3, 4 | 2.85, 2.77, 3.20 | [33] |

| FA-PLS | 2, 2, 3 | 1.68, 1.04, 1.63 | [33] | |

| Ciprofloxacin, Lomefloxacin, Enrofloxacin | FA-PLS | Not Specified | Low, validated by ICH | [32] |

| Propranolol, Rosuvastatin, Valsartan | FA-ANN | Not Specified | Low, validated by ICH | [34] |

### Table 2: Greenness and Practicality Assessment of UV/Vis-Chemometric vs. HPLC Methods

Table evaluating the environmental impact and practicality of the developed UV/Vis-Chemometric method compared to a traditional HPLC method using AGREE and BAGI metrics.

| Assessment Tool | UV/Vis-Chemometric Method (FA-PLS) | Traditional HPLC Method | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE Score | 0.78 - 0.79 [32] [33] | ~0.64 [33] | Higher score = superior environmental friendliness |

| BAGI Score | 77.5 [32] | Not Specified | Higher score = better practical applicability |

## Workflow and Algorithm Visualization

### PLS-FA Experimental Workflow

### Firefly Algorithm Logic

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table listing essential materials, reagents, and software used in the development of PLS-FA methods for UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provide pure analyte for calibration. | Certified purity >98% (e.g., from Drug Authorities) [32] [34]. |

| Green Solvent Systems | Dissolve analytes while minimizing environmental impact. | Water, 10% acetic acid, or water:ethanol (1:1 v/v) [32] [35]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Acquire spectral fingerprints of mixtures. | Double-beam with 1 cm quartz cells; e.g., Shimadzu UV-1800 [32] [35]. |

| Chemometric Software | Develop and validate PLS and FA models. | MATLAB environment is commonly used [32] [34]. |

| Refractometer | Detect and correct for spectral interference from unknown impurities. | Used for constrained refractometry; e.g., ATAGO RX-7000i [1]. |

Difference Spectrum Analysis and Turbidity Compensation Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is turbidity interference, and why is it a problem in UV-Vis spectroscopy? Turbidity, caused by suspended particles in a sample, is a significant physical interference in UV-Vis spectroscopy. These particles scatter light, reducing the amount of light that reaches the detector. This scattering effect adds a background signal to the true absorbance of your analyte, changing the magnitude and shape of the absorption spectrum. Consequently, this leads to inaccurate concentration calculations, particularly for analytes like nitrate or when measuring Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) in water samples [36] [37] [38].

2. How does Difference Spectrum Analysis help compensate for turbidity? Difference Spectrum Analysis works by isolating the spectral change caused specifically by turbidity. The method involves subtracting the absorption spectrum of a pure analyte solution from the spectrum of a mixed solution containing both the analyte and turbidity. This "difference spectrum" reveals how turbidity alters the absorbance at different wavelengths. Research shows that for nitrate, this change is consistent at wavelengths above 230 nm for the same level of turbidity, regardless of the nitrate concentration. This characteristic allows for the creation of a robust turbidity compensation model [36] [39].

3. What are the main strategies for turbidity compensation? There are two primary strategies for turbidity compensation [36] [37] [39]:

- Model-Based Subtraction: This involves calculating the absorbance contribution from turbidity and subtracting it from the original sample spectrum. Methods include Difference Spectrum analysis [39], exponential modeling of turbidity's absorbance [38], and physically-based models like Mie scattering theory [37].

- Algorithmic Correction: These methods use statistical or machine learning models to map the turbidity-interfered spectrum to a corrected one. Examples include Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC), Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC), and deep learning models like 1D U-Net [37].

4. Which wavelength range is optimal for building a turbidity-compensation model for nitrate? For nitrate analysis, studies have identified the wavelength range of 230–240 nm as optimal for building a turbidity-compensation model using difference spectra. In this region, the difference spectra for different nitrate concentrations overlap, meaning the effect of turbidity is constant and proportional to the turbidity level itself, making it ideal for linear modeling [36] [39].

5. When should I use deep learning for turbidity compensation? Deep learning methods, such as a 1D U-Net, are particularly suitable for complex, real-world environmental samples like river water. They are powerful when dealing with variable water matrices where traditional models may fail, as they can learn complex relationships between the interfered spectrum and the pure analyte spectrum without requiring prior knowledge of the sample's physical properties [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Nitrate Concentration Readings in Turbid Water

Symptoms: Consistently over-estimated or unstable concentration values; poor fit when validating with standard methods. Solution: Implement a Difference Spectrum turbidity-compensation method.

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare Calibration Set: Create a series of standard solutions with varying, known concentrations of nitrate. Also, prepare a set of turbidity standards (e.g., using formazine suspension) across the expected range [38].

- Generate Difference Spectra: For each combination of nitrate and turbidity, collect the UV absorption spectrum of the mixed solution. Then, subtract the spectrum of the pure nitrate solution (at the same concentration) to obtain the difference spectrum [39].

- Identify Modeling Wavelength: Analyze the difference spectra to find the wavelength interval where the change in absorbance is constant for a given turbidity, independent of nitrate concentration (e.g., 230-240 nm for nitrate) [36] [39].