Analytical Method Validation: A Complete Guide to Principles, Parameters, and Regulatory Compliance

This comprehensive guide explores analytical method validation, a critical process ensuring reliability and compliance in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical development.

Analytical Method Validation: A Complete Guide to Principles, Parameters, and Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores analytical method validation, a critical process ensuring reliability and compliance in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical development. It covers foundational principles, key validation parameters (accuracy, precision, specificity), regulatory guidelines (ICH Q2(R2), Q14), and practical strategies for troubleshooting and lifecycle management. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides actionable insights for developing robust, compliant analytical methods that guarantee data integrity and patient safety.

Understanding Analytical Method Validation: Building Your Regulatory Foundation

Analytical Method Validation (AMV) is a critical scientific and regulatory process within pharmaceutical quality control, defined as the process of providing documented evidence that an analytical method does what it is intended to do [1] [2]. In a regulated environment, it establishes through laboratory studies that the performance characteristics of the method meet the requirements for the intended analytical application, providing assurance of reliability during normal use [2]. For any medical laboratory or pharmaceutical manufacturer seeking accreditation, demonstrating that quality standards have been implemented to generate correct results is a cornerstone of the accreditation process [3]. The process is fundamentally concerned with error assessment—determining the scope of possible errors within laboratory assay results and the extent to which this degree of error could affect clinical interpretations and, consequently, patient care [3]. Within the broader context of analytical method validation research, AMV provides the objective, quantifiable framework that bridges drug development, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance, ensuring that every measured value used to make a decision about drug quality, safety, or efficacy is itself trustworthy.

The Critical Importance of Analytical Method Validation

The importance of Analytical Method Validation extends far beyond a mere regulatory checkbox; it is a fundamental pillar of pharmaceutical quality control that directly impacts patient safety, product quality, and regulatory compliance.

Ensuring Patient Safety and Product Efficacy: Well-developed and validated methods are essential for ensuring product quality and safety [4]. They accurately detect contaminants, degradation products, and variations in active ingredient concentrations, ensuring that pharmaceuticals meet stringent quality specifications. Failure to detect a harmful impurity due to an inadequate method could pose a significant public health risk [4]. Validation provides the assurance that a method can reliably measure critical quality attributes (CQAs), such as the identity, strength, and purity of a drug product, which are vital for its therapeutic performance [5].

Regulatory Compliance and Commercial Distribution: Analytical Method Validation is not optional but a mandatory requirement for regulatory submissions and commercial distribution of pharmaceuticals [4] [5]. Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) require comprehensive validation data to support drug approval applications like New Drug Applications (NDAs) [4]. The FDA considers successful Process Performance Qualification (PPQ) batches, which rely on validated methods, as the final step before commercial distribution is permitted [5]. Compliance with guidelines like ICH Q2(R1) is therefore legally enforceable, and pharmaceuticals can be deemed "adulterated" if not manufactured according to these validation guidelines [5].

Foundation for Manufacturing Process Control: In pharmaceutical manufacturing, the quality of every unit cannot always be directly verified. Instead, the industry relies on a thorough understanding, documentation, and control of the manufacturing process to ensure consistent quality [5]. Validated analytical methods are the tools that generate the data to establish this understanding. They are used to map the design space of manufacturing equipment, define process control strategies, and verify that the process is running within established parameters, thereby protecting the product revenue stream by maximizing yield and reducing troubleshooting shutdowns [5].

Core Performance Characteristics and Validation Protocols

The validation of an analytical method involves the systematic evaluation of several key performance characteristics. These parameters are investigated based on the type of method and its intended use, as defined by international guidelines [1] [4]. The following section details these characteristics, their definitions, and the standard experimental protocols used to assess them.

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics for Analytical Method Validation

| Characteristic | Definition | Standard Experimental Protocol & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between an accepted reference value and the value found [2]. It reflects the degree to which a measurement conforms to the actual amount of analyte [4]. | - Protocol: Comparison of results to a standard reference material or by analysis of synthetic mixtures (placebos) spiked with known quantities of analyte (spike recovery) [1] [2]. - Data: Minimum of 9 determinations over at least 3 concentration levels covering the specified range [1] [2]. - Reporting: Percent recovery (e.g., 98–102%) or the difference between the mean and true value with confidence intervals [1] [4]. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement among individual test results from repeated analyses of a homogeneous sample [2]. It is commonly expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) [1]. | - Repeatability (Intra-assay): Same analyst, equipment, short time interval; minimum of 9 determinations or 6 at 100% test concentration [1] [2]. - Intermediate Precision: Different analysts, equipment, days; experimental design to monitor effects of variables [1] [4]. - Acceptance: % RSD; often <2% is recommended, but <5% can be acceptable for minor components [1]. |

| Specificity | The ability to measure the analyte of interest accurately and specifically in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present [2]. | - Protocol: Demonstrate that the analyte peak is well-resolved from interfering peaks (e.g., impurities, excipients, degradants) [4]. - Techniques: Chromatographic resolution, peak purity assessment using photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) [1] [2]. |

| Linearity & Range | Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results directly proportional to analyte concentration [2]. Range: The interval between upper and lower concentrations demonstrated to be determined with precision, accuracy, and linearity [2]. | - Protocol: A minimum of 5 concentration levels across the specified range [1] [2]. - Reporting: Equation for the calibration curve, coefficient of determination (R²), and residuals [1] [2]. - Acceptance: R² typically ≥ 0.999 [4]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) & Quantitation (LOQ) | LOD: The lowest concentration that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified [2]. LOQ: The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [2]. | - Protocol: Based on signal-to-noise ratio (S/N): 3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ [1] [2]. Alternatively, LOD=3.3σ/Slope and LOQ=10σ/Slope, where σ is the standard deviation of the response [3]. - Validation: Analyze an appropriate number of samples at the calculated limit to validate performance [2]. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters [1]. | - Protocol: Intentional variation of parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, flow rate, column temperature) [1]. - Measurement: Monitor effects on critical performance criteria (e.g., resolution, tailing factor) [1]. - Purpose: Indicates the method's reliability during normal use and its suitability for transfer between labs [1]. |

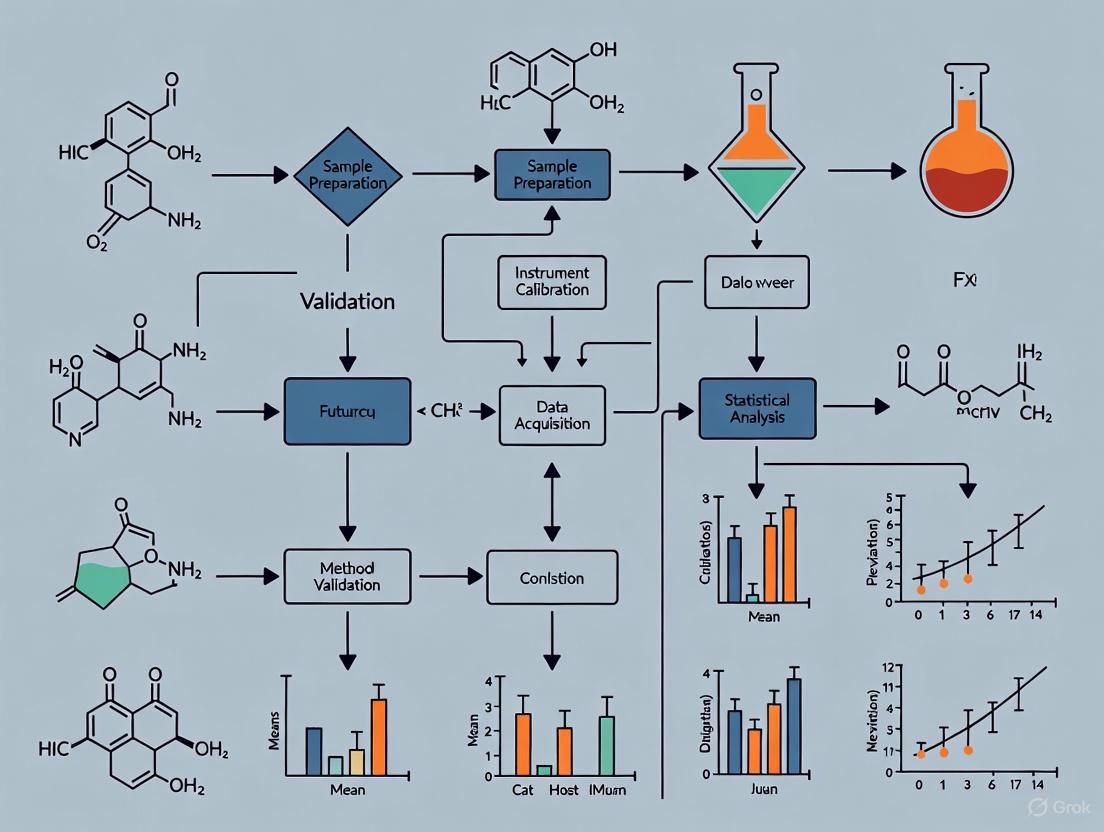

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence and relationships between the key stages of the analytical method validation lifecycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The execution of a robust analytical method validation relies on a suite of high-quality, well-characterized reagents and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their critical functions in the validation process.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Analytical Method Validation

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Material | A substance with one or more properties that are sufficiently homogeneous and well-established to be used for the assessment of method accuracy [1] [2]. Serves as an accepted reference value. |

| High-Purity Analytes | The authentic target substance (e.g., Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient - API) of known high purity, used for preparing calibration standards and spike solutions for accuracy and linearity studies [4]. |

| Placebo/Blank Matrix | A mixture containing all excipient materials in the correct proportions but without the active analyte [1]. Used to assess specificity and to prepare spiked samples for accuracy and LOQ/LOD studies. |

| Known Impurities and Degradants | Authentic samples of potential process-related impurities and forced-degradation products [2]. Critical for experimentally demonstrating the specificity of the method. |

| Qualified Chromatographic Columns | Columns with demonstrated performance (e.g., efficiency, selectivity) for the specific method. Robustness testing often involves evaluating columns from different lots or manufacturers [1] [4]. |

| Calibrated Instrumentation | Analytical instruments (e.g., HPLC, GC) that have undergone Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ) to ensure they are fit for purpose and generate reliable data [2] [5]. |

Analytical Method Validation stands as a non-negotiable discipline within pharmaceutical quality control and the broader research landscape. It is the definitive process that transforms a developed analytical procedure into a scientifically sound and legally defensible tool. By rigorously characterizing the method's performance against predefined criteria such as accuracy, precision, and specificity, validation provides the documented evidence required to trust the data generated. This trust is the foundation for ensuring that every pharmaceutical product released to the market possesses the required identity, strength, quality, and purity, thereby safeguarding patient health and upholding the integrity of the global drug supply. As analytical technologies advance and regulatory frameworks evolve, the principles of AMV will continue to serve as the critical link between innovative drug development and consistent, reliable manufacturing.

Analytical method validation serves as a fundamental pillar in the pharmaceutical industry, providing documented evidence that a specific analytical procedure is fit for its intended purpose. This process guarantees the reliability, accuracy, and consistency of test results used to assess the identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency of drug substances and products. The precision of these methods directly influences the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products reaching patients [6]. A harmonized regulatory framework for this validation is crucial for streamlining global drug development and approval processes.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) plays a pivotal role in establishing these technical guidelines. The recently adopted ICH Q2(R2) guideline, effective from 14 June 2024, represents the most current and comprehensive standard [7] [6]. This revision, developed in parallel with ICH Q14 on Analytical Procedure Development, introduces a modernized, science-based approach to analytical validation, aligning it with the entire lifecycle of a pharmaceutical product [6] [8]. Regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have endorsed and implemented these harmonized guidelines, facilitating a unified standard for industry professionals and regulators alike [7] [9].

Objective and Scope

The primary objective of ICH Q2(R2) is to provide a general framework for the principles of analytical procedure validation and to offer guidance on the selection and evaluation of various validation tests [7] [9]. It aims to bridge differences in terminology and requirements that often exist between various international compendia and regulatory documents [9]. The guideline is designed to improve regulatory communication and facilitate more efficient, science-based, and risk-based approval, as well as post-approval change management of analytical procedures [6].

The scope of ICH Q2(R2) is extensive. It applies to new or revised analytical procedures used for the release and stability testing of commercial drug substances and products, covering both chemical and biological/biotechnological entities [9] [6]. Furthermore, it can be applied to other analytical procedures used as part of a control strategy following a risk-based approach [9]. A significant expansion in this revision is the inclusion of validation principles for the analytical use of spectroscopic or spectrometry data (e.g., NIR, Raman, NMR, MS), which often require multivariate statistical analyses [7] [6].

Historical Context and Evolution

The ICH Q2 guideline has evolved over three decades to keep pace with scientific and technological advancements. The following timeline illustrates its key developmental milestones:

Figure 1: The ICH Q2 guideline evolution timeline

The most notable change in Q2(R2) is its development in conjunction with ICH Q14, creating a seamless framework that connects analytical procedure development with validation [6]. This lifecycle approach acknowledges that validation is not a one-time event but an ongoing process.

Core Validation Principles in ICH Q2(R2)

Key Terminology and Definitions

ICH Q2(R2) provides a collection of terms and definitions crucial for ensuring a common understanding across the industry and regulatory bodies. Some of the key terms include:

- Reportable Range: This is the interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity. It replaces the previous concept of "Linearity" to better accommodate biological and non-linear analytical procedures [6].

- Working Range: This consists of the "Suitability of calibration model" and "Lower Range Limit verification." It is the actual interval of analyte concentrations over which the analytical procedure operates effectively, derived from the reportable range based on sample preparation and analytical technique [6].

- Specificity/Selectivity: The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [9].

- Accuracy and Precision: Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value, while precision expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [9].

Validation Characteristics and Experimental Protocols

The validation of an analytical procedure requires testing for several performance characteristics based on the procedure's intended purpose. The table below summarizes these characteristics and their experimental considerations:

Table 1: Analytical Procedure Validation Characteristics & Protocols

| Validation Characteristic | Experimental Protocol & Methodology | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | - Compare chromatographic or spectral profiles of analyte alone vs. in presence of interfering compounds.- For stability-indicating methods, subject samples to stress conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation). | - Demonstrate separation of analyte from known and potential impurities.- For biological assays, demonstrate interference from matrix components. |

| Working Range | - Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentration levels across the specified range.- Evaluate suitability of the calibration model (linear vs. non-linear).- Verify Lower Range Limit. | - Range is derived from the reportable range based on sample preparation and analytical technique.- Replaces the traditional "Linearity" characteristic. |

| Accuracy | - Spike placebo with known amounts of analyte (3 levels, 3 replicates each).- Compare measured results to theoretical values.- Use a minimum of 9 determinations across the specified range. | - For drug substance, compare against a reference standard of known purity.- For drug product, perform recovery studies. |

| Precision | Repeatability:- Multiple measurements by same analyst under identical conditions.Intermediate Precision:- Different days, analysts, or equipment within the same laboratory.Reproducibility:- Collaborative studies across different laboratories. | - Express as standard deviation or relative standard deviation.- Intermediate precision studies the within-laboratory variations. |

| Detection Limit (DL) & Quantitation Limit (QL) | Visual Evaluation:- Based on signal-to-noise ratio.Standard Deviation Method:- Based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve. | - DL: Lowest amount detectable but not necessarily quantifiable.- QL: Lowest amount quantifiable with acceptable precision and accuracy. |

| Robustness | - Deliberate variations in method parameters (pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, flow rate).- Use experimental design (DOE) for multivariate procedures. | - Identify critical procedural parameters that affect analytical results.- Establish a system suitability test to control these parameters. |

The experimental workflow for validating an analytical procedure follows a systematic approach, as illustrated below:

Figure 2: Analytical procedure validation workflow

The Regulatory Landscape: FDA, EMA, and USP

FDA Guidance on Analytical Procedures

The U.S. FDA has fully adopted the ICH Q2(R2) guideline, announcing its availability as a final guidance document in March 2024 [7]. This guidance provides a general framework for the principles of analytical procedure validation, including validation principles that cover the analytical use of spectroscopic data [7]. The FDA emphasizes that the guidance is intended to "facilitate regulatory evaluations and potential flexibility in postapproval change management of analytical procedures when scientifically justified" [7].

Prior to the adoption of ICH Q2(R2), the FDA maintained its own guidance document "Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation for Drugs and Biologics" from July 2015, which provided recommendations on submitting analytical procedures and methods validation data to support drug applications [10]. With the issuance of the new ICH-based guidance, the 2015 document and the 2000 draft guidance on the same topic have been effectively superseded [7] [10].

EMA's Approach to Analytical Validation

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has similarly adopted the ICH Q2(R2) guideline as a scientific guideline for the industry [9]. The EMA states that the guideline "applies to new or revised analytical procedures used for release and stability testing of commercial drug substances and products (chemical and biological/biotechnological)" and that it "can also be applied to other analytical procedures used as part of the control strategy following a risk-based approach" [9].

The EMA's scientific guidelines on specifications, analytical procedures, and analytical validation help medicine developers prepare marketing authorization applications for human medicines [11]. The agency recognizes the importance of method transfer between laboratories and has published concept papers on transferring quality control methods validated in collaborative trials to a product/laboratory specific context [12].

Relationship with USP Guidelines

While the search results do not explicitly mention USP (United States Pharmacopeia) guidelines, it is important to note that USP general chapters on validation of compendial procedures have historically been aligned with ICH guidelines. With the adoption of ICH Q2(R2), it is expected that USP will update its relevant chapters to maintain alignment with these international standards.

The harmonized approach between ICH, FDA, EMA, and USP reduces the regulatory burden on pharmaceutical companies operating in multiple regions, allowing them to develop a single validation package that meets the requirements of all these regulatory bodies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful analytical method validation requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their functions in validation experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | - Certified materials with known purity and identity used to calibrate instruments and prepare known concentration samples for accuracy, precision, and linearity studies. | - Drug substance and drug product reference standards from USP, EP, or certified suppliers. |

| Placebo Formulation | - A mixture of all inactive components of the drug product used to demonstrate specificity and assess potential interference in accuracy and LOD/LOQ studies. | - Prepared according to the drug product composition without the active ingredient. |

| Forced Degradation Materials | - Chemicals and conditions used to intentionally degrade the drug substance or product to demonstrate the stability-indicating capability of the method. | - Acid (e.g., HCl), Base (e.g., NaOH), Oxidizing agents (e.g., H₂O₂), Thermal chambers, UV light chambers. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | - Used for preparation of mobile phases, sample solutions, and standard solutions to minimize background interference and ensure reproducibility. | - HPLC-grade solvents, ultrapure water, analytical-grade salts and buffers. |

| System Suitability Test Materials | - Reference preparations used to verify that the analytical system is operating properly before and during the analysis of validation samples. | - Typically a reference standard solution at a specific concentration that provides key parameters (e.g., retention time, peak area, resolution). |

Advanced Topics: Q2(R2) and Multivariate Methods

Integration with ICH Q14: A Lifecycle Approach

A fundamental advancement in the revised guideline is its intrinsic connection with ICH Q14 "Analytical Procedure Development." These two documents were developed in parallel and are intended to be implemented together, creating a comprehensive framework for the entire analytical procedure lifecycle [6] [8]. This integrated approach offers several significant benefits:

- Knowledge-Driven Validation: Suitable data derived from development studies (per ICH Q14) can be used as part of the validation data package, reducing redundant testing and leveraging existing knowledge [6].

- Risk-Based Approaches: The enhanced understanding gained during method development facilitates a more scientific, risk-based validation strategy, focusing resources on critical method aspects [8].

- Efficient Change Management: Knowledge gained from applying an enhanced approach to analytical procedure development provides better assurance of procedure performance and enables more efficient regulatory approaches to postapproval changes [8].

Validation of Multivariate and Non-Linear Methods

ICH Q2(R2) explicitly addresses the validation of modern analytical techniques, including multivariate methods such as Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman spectroscopy, which often employ complex statistical models like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression [6]. The guideline recognizes that these methods may not follow traditional linear relationships and provides adapted validation principles.

For these advanced techniques, the concept of "Reportable Range" replaces the traditional "Linearity" characteristic, acknowledging that some analytical procedures, particularly biological assays, may exhibit non-linear response functions [6]. The validation focuses on the "Working Range," which consists of verifying the suitability of the calibration model and the lower range limit [6]. This approach ensures that these powerful analytical tools can be appropriately validated and gain regulatory acceptance.

The regulatory framework for analytical method validation, centered on ICH Q2(R2) with adoption by FDA and EMA, represents a significant evolution in pharmaceutical quality systems. This modernized approach embraces scientific understanding, risk-based principles, and lifecycle management of analytical procedures. The integration of Q2(R2) with ICH Q14 creates a cohesive system that connects development with validation, facilitating more robust analytical procedures and efficient post-approval changes.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and implementing this harmonized framework is crucial for successful regulatory submissions across international markets. The guidelines provide the flexibility to incorporate advanced analytical technologies while maintaining rigorous standards for demonstrating that analytical procedures remain fit for their intended purpose throughout their lifecycle. As analytical technologies continue to evolve, this science- and risk-based framework will continue to support innovation while ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy.

Analytical method validation provides documented evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility of data in pharmaceutical research and drug development. This in-depth technical guide examines the three core scenarios mandating validation activities: prior to routine use, following method changes, and when introducing new biological matrices. Framed within broader analytical method validation research, this whitepaper details specific experimental protocols and provides structured tables of validation parameters, serving as a critical resource for researchers and development professionals in maintaining data integrity and regulatory compliance.

Method validation is a required process in any regulated environment, providing objective evidence that a method consistently fulfills the requirements for its specific intended use [13] [2]. In pharmaceutical development and bioanalysis, the "fit-for-purpose" paradigm governs validation activities, with the extent of validation directly determined by the application of the data generated [14]. Validation establishes performance characteristics such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness through structured laboratory studies, offering assurance of reliability during normal use [2]. The fundamental requirement stems from the need to ensure the scientific validity of results produced during routine sample analysis, which forms the basis for critical decisions in drug exploration, development, and manufacture [14].

Within a comprehensive validation framework, three primary triggers necessitate validation activities: initial validation before routine application (full validation), re-validation following method modifications (partial validation), and validation when applying existing methods to new matrices (cross-validation or partial validation) [13] [15] [14]. Understanding these requirements is essential for maintaining quality standards throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Core Scenarios Requiring Validation

Pre-Routine Use (Full Validation)

Full validation is comprehensively required for newly developed methods before their implementation in routine testing [13] [14]. This extensive validation provides the foundational documentation of all relevant performance characteristics when no prior validation data exists. According to international guidelines, full validation applies to methods used to produce data supporting regulatory filings or pharmaceutical manufacture for human use [14]. This includes bioanalytical methods for bioavailability (BA), bioequivalence (BE), pharmacokinetic (PK), toxicokinetic (TK), and clinical studies, alongside analytical testing of manufactured drug substances and products [14].

The International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) specifies four primary method types requiring validation, each with distinct requirements [14]:

- Identification tests ensuring analyte identity through comparison to reference standards

- Quantitative tests for impurities content accurately reflecting purity characteristics

- Limit tests controlling impurities

- Quantitative assays measuring the analyte present in drug substance or product

For full validation, all relevant performance parameters must be established, typically including specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, detection limit, quantitation limit, robustness, and system suitability [2] [16]. The standard operating procedures (SOPs) with step-by-step instructions should be developed specifically for immunochemical methods and multicenter evaluations, though most remain generic enough for other technologies [13].

Method Changes (Partial Validation or Re-validation)

Partial validation is performed when a previously-validated method undergoes modifications that do not constitute fundamental changes to the method's core principles but may still impact performance [13] [14]. This limited validation scope confirms that the method remains suitable for its intended use following specific, defined changes.

Common triggers for partial validation include [14] [2]:

- Transfer of a validated method to another laboratory to be run on different instrumentation by different personnel

- Changes in equipment or instrumentation platforms

- Modifications to solution composition or reagent suppliers

- Adjustments to quantitation range to accommodate different sample concentrations

- Revisions to sample preparation procedures that do not alter the fundamental extraction principle

- Updates to software controlling analytical instrumentation

The extent of partial validation depends directly on the nature and significance of the changes implemented. As stated in validation guidelines, "if a validated in vitro diagnostic (IVD) method is transferred to another laboratory to be run on a different instrument by a different technician it might be sufficient to revalidate the precision and the limits of quantification since these variables are most sensitive to the changes, while more intrinsic properties for a method, e.g., dilution linearity and recovery, are not likely to be affected" [13]. The specific parameters requiring re-validation should be determined through risk assessment evaluating the potential impact of each change on method performance [14].

New Matrices (Partial Validation)

Introducing a new biological matrix from the same species into a previously validated method necessitates partial validation to address matrix-specific effects [15]. This requirement recognizes that biological matrices differ significantly in composition, potentially affecting analytical method performance through matrix effects, interference, or differential analyte recovery.

International guidance specifically recommends partial validation when introducing new matrices, with particular attention to matrix protein content as a critical variable [15]. Transitioning a method validated for serum or plasma to analysis of low-protein matrices such as urine, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), or oral fluid frequently results in inconsistent analyte recovery due to several factors:

- Increased non-specific binding in low-protein matrices leading to reduced recovery

- Exacerbated adsorption and absorption interactions with container materials

- Differences in endogenous compounds that may cause interference

- Variations in pH and ionic strength affecting analyte stability and detection

The matrix protein content significantly influences method performance, as higher protein levels typically facilitate better analyte stability and reduce surface interactions [15]. When validating methods for low-protein matrices, mitigation strategies may include adding surfactants, bovine serum albumin (BSA), or β-cyclodextrin to minimize non-specific binding and improve recovery rates [15].

Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

Key Validation Parameters

Analytical method validation systematically evaluates multiple performance characteristics to ensure method suitability. The specific parameters assessed depend on the method type and its intended application, with full validation requiring comprehensive evaluation.

Table 1: Essential Validation Parameters and Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between accepted reference value and value found | Analysis of samples spiked with known quantities of analyte; comparison to reference material [2] |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent test results under stipulated conditions | Repeated analyses of homogeneous samples; measured as repeatability, intermediate precision, reproducibility [13] [2] |

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte accurately in presence of components that may be expected to be present | Resolution of analyte from closely eluting compounds; peak purity tests using PDA or MS detection [2] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain test results proportional to analyte concentration within given range | Minimum of 5 concentration levels across specified range; statistical analysis of calibration curve [2] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower concentrations with demonstrated precision, accuracy, linearity | Established from linearity studies; confirms acceptable performance across specified concentration levels [2] |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be detected (LOD) or quantitated (LOQ) with acceptable precision | Signal-to-noise ratios (3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ) or based on standard deviation of response and slope [2] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters | Systematic changes to critical parameters (e.g., incubation times, temperatures) while analyzing same samples [13] |

| Recovery | Detector response from analyte added to and extracted from matrix compared to true concentration | Comparison of extracted samples to non-extracted standards; demonstrates extraction efficiency [13] |

Experimental Design and Protocols

Precision Evaluation

Precision validation encompasses three distinct measurements requiring specific experimental designs [13] [2]:

Repeatability (intra-assay precision): Assessed by analyzing a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (three concentrations, three repetitions each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration under identical conditions over a short time interval. Results reported as %RSD.

Intermediate precision: Evaluates within-laboratory variations due to random events using experimental design where factors are deliberately varied (different days, analysts, equipment). Typically generated by two analysts preparing and analyzing replicate sample preparations independently, using different HPLC systems. Results subjected to statistical testing (e.g., Student's t-test) to examine differences in mean values.

Reproducibility: Assesses collaborative studies between different laboratories, requiring a minimum of eight sets of acceptable results after outlier removal. Documentation includes standard deviation, relative standard deviation, and confidence intervals.

Robustness Testing

Robustness validation follows a structured protocol [13]:

- Identify critical parameters in the procedure (e.g., incubation times, temperatures, pH, mobile phase composition)

- Perform assays with systematic variations in these parameters, one at a time, using identical test samples

- If measured concentrations remain unaffected by variations, adjust protocol to incorporate appropriate tolerances (e.g., 30 ± 3 minutes)

- If changes systematically alter results, reduce magnitude of variations until no dependence is observed

- Incorporate established tolerances into the final method protocol

For methods with multiple critical parameters, specialized software (e.g., MODDE) or published experimental design methods can reduce the number of required experiments [13].

Matrix-Related Partial Validation

When introducing a new matrix, a targeted partial validation protocol should include [15]:

- Comparison of matrix properties: Evaluate analyte chemistry, sample container materials, and biological matrix characteristics between original and new matrices

- Assessment of matrix effects: Analyze multiple lots of the new matrix (at least 6) to account for natural variability, comparing precision and accuracy to original validation

- Recovery experiments: Determine analyte recovery in the new matrix across the validated concentration range, identifying potential non-specific binding issues

- Stability assessment: Evaluate analyte stability in the new matrix under various storage conditions

- Selectivity verification: Confirm absence of interfering substances specific to the new matrix

Decision Framework for Validation Requirements

The flowchart below outlines the decision process for determining the appropriate validation level based on specific scenarios and changes to the analytical method:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method validation requires specific, high-quality materials and reagents to ensure accurate and reproducible results. The following table details essential components for validation experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Material/Reagent | Function in Validation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides accepted reference value for accuracy determination; establishes calibration curve | Purity certification; proper storage conditions; stability documentation [2] |

| Matrix Blank Samples | Evaluates specificity and selectivity; establishes baseline interference | Multiple lots required to account for natural variability; appropriate storage [15] [17] |

| Quality Control Samples | Assesses precision and accuracy across validation range | Prepared at low, medium, high concentrations; should mimic actual study samples [17] |

| Internal Standards | Compensates for variability in sample preparation and analysis | Stable isotope-labeled analogs preferred; should not interfere with analyte [2] |

| System Suitability Solutions | Verifies chromatographic system performance before validation experiments | Evaluates resolution, tailing factor, plate count, repeatability [2] |

| Protein Additives (BSA) | Mitigates non-specific binding in low-protein matrices | Critical for urine, CSF, oral fluid validations; concentration optimization required [15] |

| Surfactants & Stabilizers | Improves recovery in challenging matrices; enhances solubility | Compatibility with detection method; minimal background interference [15] |

Method validation represents a fundamental requirement in pharmaceutical research and drug development, providing documented evidence of analytical procedure suitability for its intended use. The three primary scenarios demanding validation activities—pre-routine implementation, method modifications, and new matrix introduction—form the cornerstone of quality assurance in analytical data generation. Understanding the distinction between full, partial, and cross-validation approaches enables scientists to allocate resources efficiently while maintaining regulatory compliance. As analytical technologies advance and regulatory expectations evolve, the principles of method validation remain essential for ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility of data supporting critical decisions in the drug development lifecycle. Through systematic application of the protocols and decision frameworks outlined in this technical guide, researchers and development professionals can effectively establish method suitability while advancing the broader objectives of analytical method validation research.

Analytical method validation is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical development, providing the foundation for data integrity and regulatory compliance. This in-depth technical guide examines the three essential prerequisites for successful method validation: robust instrument qualification, well-characterized reference standards, and comprehensive analyst training. Framed within the broader context of analytical method validation research, this whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with detailed methodologies, technical specifications, and practical frameworks for establishing these foundational elements. The objective of validation is to demonstrate that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, requiring meticulous attention to these prerequisites before validation activities can commence [18].

Within the pharmaceutical development lifecycle, analytical method validation research generates evidence that test methods are capable of producing reliable results that support product quality assessments. According to regulatory guidelines, "Methods validation is the process of demonstrating that analytical procedures are suitable for their intended use" [18]. This process depends entirely on three fundamental pillars: properly qualified instruments that generate accurate data, characterized reference standards that provide points of comparison, and competent analysts who execute procedures correctly. Without establishing these prerequisites, any subsequent validation data remains questionable.

The requirement for validated methods extends throughout the drug development continuum. While early-phase studies may employ "qualified" methods with limited validation data, late-stage trials and commercial products require fully validated methods per current regulations [18]. The US Food and Drug Administration states that "the suitability of all testing methods used shall be verified under actual conditions of use" [18], making these prerequisites non-negotiable for laboratories operating under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) regulations.

Instrument Qualification

Definition and Regulatory Framework

Instrument qualification is the process of documenting that equipment is properly installed, functions correctly, and performs according to predefined specifications, thus ensuring it is fit for its intended analytical purpose. Qualification establishes evidence that instruments produce reliable and consistent results, forming the foundational layer for all subsequent analytical measurements. The International Organization for Standardization outlines competency and operational requirements for testing laboratories in ISO/IEC 17025, which emphasizes the need for properly maintained equipment to ensure valid results [19].

The Four-Phase Qualification Framework

Instrument qualification follows a structured approach across four distinct phases:

- Design Qualification (DQ): The documented verification that the proposed instrument design and specifications meet the analytical requirements and intended application. This phase establishes the foundation for all subsequent qualification activities.

- Installation Qualification (IQ): The documented verification that the instrument has been delivered, installed, and configured according to the manufacturer's specifications and the laboratory's requirements. This includes verification of components, documentation, and installation environment.

- Operational Qualification (OQ): The documented verification that the installed instrument operates according to predefined specifications throughout its anticipated operating ranges. This phase tests instrument functionality and performance under standardized conditions.

- Performance Qualification (PQ): The documented verification that the instrument consistently performs according to predefined specifications for the specific analytical methods and applications under actual conditions of use. This ongoing verification occurs during routine analysis.

Performance Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

The table below summarizes key performance parameters and typical acceptance criteria for liquid chromatography instrumentation, though specific requirements vary by instrument type and application.

Table 1: Performance Parameters for Liquid Chromatography Instrument Qualification

| Parameter | Test Method | Acceptance Criteria | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pump Flow Accuracy | Measure volumetric flow at multiple set points | ± 1-2% of set flow rate | OQ / Periodic PQ |

| Pump Composition Accuracy | Measure ratio of mobile phases | ± 0.5-1.0% absolute | OQ / Periodic PQ |

| Injector Precision | Multiple injections of standard | RSD ≤ 0.5-1.0% | OQ / Periodic PQ |

| Injector Carryover | Inject blank after high concentration | ≤ 0.1-0.5% of target concentration | OQ / Periodic PQ |

| Detector Wavelength Accuracy | Scan holmium oxide filter | ± 1-2 nm from certified values | OQ / Annual PQ |

| Detector Noise and Drift | Monitor baseline signal | Specification per manufacturer | OQ / Periodic PQ |

| Column Oven Temperature | Measure with independent probe | ± 1-3°C of set temperature | OQ / Annual PQ |

Experimental Protocol for Pump Flow Accuracy

Purpose: To verify that the delivered flow rate matches the set flow rate across the instrument's operational range.

Materials: Calibrated digital thermometer, calibrated analytical balance (0.1 mg sensitivity), weighing vessel, HPLC-grade water, stopwatch, and graduated cylinder.

Procedure:

- Allow the HPLC system to equilibrate at ambient temperature.

- Set the pump to deliver 100% mobile phase (water) at 1.0 mL/min.

- Prime the system thoroughly to remove air bubbles.

- Place an empty weighing vessel on the balance and tare.

- Direct the column outlet to the weighing vessel and simultaneously start the stopwatch.

- Collect eluent for exactly 10 minutes.

- Weigh the collected eluent and record the mass.

- Calculate the actual flow rate using the density of water at the recorded temperature.

- Repeat the procedure at different flow rates (e.g., 0.5 mL/min, 1.5 mL/min, 2.0 mL/min).

- Calculate the percentage difference between set and actual flow rates.

Acceptance Criteria: The actual flow rate must be within ± 2% of the set flow rate at each tested value.

Reference Standards

Characterization and Classification

Reference standards are highly characterized substances used as comparison benchmarks in analytical procedures. They provide the critical link between measured values and true values, enabling quantification and method qualification. According to regulatory guidelines, method specificity must demonstrate the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents, which requires well-characterized reference standards [18].

Table 2: Classification and Characterization of Reference Standards

| Standard Type | Source | Characterization Requirements | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Reference Standard | Pharmacopeial (USP, EP) or certified reference material | Fully characterized with Certificate of Analysis (CoA); highest purity available | Method validation and qualification |

| Secondary Reference Standard | Qualified against primary standard; internally or commercially sourced | CoA with purity and qualification data | Routine testing where primary standard is unavailable or costly |

| Working Reference Standard | Qualified against primary or secondary standard; internally prepared | Documented testing for identity, purity, and strength | Daily system suitability and calibration |

| Impurity Reference Standard | Pharmacopeial, commercial, or isolated from process | Characterized with identity and purity assessment | Identification and quantification of impurities |

Experimental Protocol for Purity Determination by HPLC

Purpose: To determine the purity of a reference standard using HPLC with area normalization for use in method validation.

Materials: Reference standard sample, HPLC system with UV detector, qualified balance, appropriate solvents, and calibrated volumetric glassware.

Procedure:

- Prepare the sample solution at an appropriate concentration (typically 0.1-1.0 mg/mL) in the designated diluent.

- Inject the sample solution into the HPLC system using the validated method.

- Record the chromatogram with adequate run time to ensure all impurities are eluted and detected.

- Integrate all peaks in the chromatogram, excluding the solvent front.

- Calculate the percentage of each impurity using the area normalization method: % Impurity = (Peak Area of Impurity / Total Area of All Peaks) × 100%

- Calculate the purity of the main component: % Purity = 100% - Total % of All Impurities

- Perform minimum triplicate determinations to ensure result consistency.

Acceptance Criteria: The primary reference standard should have a purity of ≥ 99.0% unless otherwise justified. The relative standard deviation (RSD) for replicate determinations should be ≤ 2.0%.

Storage and Handling Requirements

Proper storage and handling are critical for maintaining reference standard integrity. Standards should be stored in conditions that maintain stability, typically in sealed containers protected from light, moisture, and excessive temperature. The storage conditions should be based on stability data and clearly documented. Access should be controlled to prevent contamination or mix-ups, and usage logs should track quantities and dates of use.

Trained Analysts

Competency Requirements

Analyst competency forms the human foundation of reliable analytical data. ISO/IEC 17025 emphasizes that "the laboratory shall document the competence requirements for each function influencing the results of laboratory activities" [20]. This includes specific requirements for education, qualification, training, technical knowledge, skills, and experience appropriate to each role. Competency requirements must be formally documented for all positions, including technicians, internal auditors, quality managers, and support staff involved in laboratory activities [20].

Comprehensive Training Framework

ISO/IEC 17025 requires laboratories to maintain procedures for determining competency requirements, personnel selection, training, supervision, authorization, and ongoing monitoring of competence [20]. The training process should include:

- Initial Assessment: Evaluation of education, qualifications, and experience against documented competency requirements.

- Structured Training Program: Combination of theoretical instruction and practical exercises on specific techniques, instruments, and standard operating procedures.

- Supervised Practice: Hands-on application of methods under supervision until proficiency is demonstrated.

- Authorization: Formal approval to perform specific tasks independently based on demonstrated competency.

- Continuous Monitoring: Ongoing assessment through performance reviews, proficiency testing, and periodic recertification.

Experimental Protocol for Analyst Competency Assessment

Purpose: To objectively demonstrate an analyst's competency in executing a specific analytical method.

Materials: Approved test method procedure, qualified instrument, reference standards, test samples, and data recording system.

Procedure:

- Select a validated analytical method relevant to the analyst's responsibilities.

- Provide the analyst with the method procedure, applicable SOPs, and necessary materials.

- The analyst prepares all required solutions and standards independently.

- The analyst performs the analysis according to the method, including system suitability tests.

- A qualified supervisor observes the technique and records any deviations.

- The analyst processes the data and reports the results.

- Evaluate the results against predefined criteria including:

- System suitability requirements met

- Accuracy of standard preparation (compared to theoretical values)

- Precision of replicate injections (RSD within specified limits)

- Accuracy of sample results (compared to known values or reference analyst)

- Adherence to documentation and data integrity practices

Acceptance Criteria: The analyst must meet all method validation parameters (accuracy, precision, etc.) within specified limits and demonstrate proper technique without critical errors.

Integrated Workflow for Establishing Prerequisites

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and sequential dependencies between the three essential prerequisites in the analytical method validation framework:

Analytical Method Validation Prerequisites Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for establishing the prerequisites for analytical method validation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation Prerequisites

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Quality Requirements | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Suitability Standards | Verify instrument performance and method suitability prior to analysis | Certified reference materials or highly characterized compounds | Daily instrument qualification and method performance verification |

| Primary Reference Standards | Provide ultimate traceability for quantitative measurements | Pharmacopeial standards or CRM with full characterization | Method validation, qualification of secondary standards, critical testing |

| HPLC/MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation to minimize background interference and enhance detection | Low UV absorbance, high purity, minimal particulate matter | All chromatographic methods, especially for sensitive detection techniques |

| Volumetric Glassware | Precise measurement and preparation of standard and sample solutions | Class A certification, calibration certificates | Standard preparation, sample dilution, mobile phase preparation |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Standards | Internal standards for mass spectrometric methods to correct for variability | High isotopic purity, chemical purity matching analyte | Bioanalytical method validation, complex matrix analysis |

| Filter Membranes | Sample clarification and removal of particulate matter | Low extractables, compatible with solvent systems, appropriate pore size | Sample preparation for chromatographic analysis, especially UHPLC systems |

Instrument qualification, reference standards, and trained analysts represent the fundamental triad that must be established before undertaking analytical method validation research. These prerequisites ensure the generation of reliable, accurate, and reproducible data that meets regulatory expectations. By systematically addressing these foundational elements through documented protocols, objective evidence, and continuous monitoring, laboratories establish a culture of quality and scientific rigor. This foundation supports the broader objective of analytical method validation research: to demonstrate unequivocally that analytical procedures are fit for their intended purpose throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Analytical method validation represents a critical investment in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing, serving as the primary defense against product failure, regulatory non-compliance, and patient harm. This technical guide examines the structured framework of method validation through a risk-based lens, demonstrating how rigorous experimental protocols and lifecycle management directly reduce business risks while safeguarding patient safety. By implementing modern validation approaches aligned with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines, organizations can achieve significant cost reductions through streamlined operations while ensuring the reliability of analytical data that forms the foundation of therapeutic decision-making.

Analytical method validation is the documented process of proving that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability, reproducibility, and compliance of data throughout the drug development lifecycle [21]. Beyond technical necessity, validation represents a strategic business function that systematically mitigates risks across multiple domains—regulatory, operational, financial, and most critically, patient safety. The fundamental business case for validation rests on its capacity to prevent costly failures, streamline product development, and maintain product quality that protects consumers.

The contemporary validation landscape has evolved from a prescriptive "check-the-box" exercise to a science- and risk-based framework emphasized in modern ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines [22]. This paradigm shift enables organizations to focus resources more efficiently, with implementations typically reducing unnecessary testing by 30-45% while maintaining or improving quality outcomes [23]. The validation process thus transforms from a compliance cost center to a value-generating activity that directly supports business objectives through enhanced efficiency and risk mitigation.

Regulatory Foundation and the Risk-Based Approach

The ICH and FDA Regulatory Framework

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides the harmonized framework that becomes the global gold standard for analytical method guidelines, with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adopting these guidelines for use in the United States [22]. The simultaneous release of ICH Q2(R2) on validation and ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development represents a significant modernization, shifting validation from a one-time event to a continuous lifecycle management process [22].

This regulatory evolution emphasizes a risk-based approach to validation, where resources are allocated according to the potential impact on product quality and patient safety. Method validation risk assessment provides a structured framework to evaluate potential failure points before they impact results, systematically examining critical parameters that might affect method performance from sample preparation to instrument variability and data interpretation [23].

Core Validation Parameters and Requirements

ICH Q2(R2) outlines fundamental performance characteristics that must be evaluated to demonstrate a method is fit for purpose. The selection and extent of validation testing depend on the method's intended use and the associated risks to product quality [9].

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Their Risk Mitigation Functions

| Validation Parameter | Technical Definition | Risk Mitigation Function | Business Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value [22] | Prevents incorrect potency assessments | Avoids product recall, overdose, or underdose |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among repeated measurements [22] | Controls variability in manufacturing quality control | Reduces batch rejection rates |

| Specificity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally [22] | Ensures detection of impurities and degradation | Prevents toxic side effects from impurities |

| Linearity and Range | Interval where suitable accuracy, precision, and linearity exist [22] | Guarantees method performance across all concentrations | Prevents measurement errors at critical decision points |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small variations [22] | Ensures method reliability during transfer and long-term use | Reduces investigation costs and method troubleshooting |

Risk Assessment Methodologies in Validation

Structured Risk Assessment Framework

Method validation risk assessment is a structured approach to identifying potential failures in analytical methods before testing begins [23]. This proactive framework enables organizations to allocate validation resources efficiently by focusing efforts on critical aspects with the highest risk potential, typically reducing unnecessary testing by 30-45% while maintaining or improving quality outcomes [23].

An effective risk assessment framework includes three key components:

- Risk Identification Process: Systematic examination of each aspect of the analytical method to uncover vulnerabilities using assessment techniques like FMEA (Failure Mode Effects Analysis) or fishbone diagrams [23].

- Mitigation Strategy Development: Establishment of specific mitigation techniques designed to address each identified risk, focusing on prevention rather than reaction through redundant verification steps and quantitative acceptance criteria [23].

- Documentation and Communication: Comprehensive documentation standards that capture all risk assessment activities, providing evidence of due diligence and creating an audit trail for regulatory inspections [23].

Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and Lifecycle Management

ICH Q14 introduces the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) as a prospective summary of a method's intended purpose and desired performance characteristics [22]. By defining the ATP at the beginning of development, organizations can use a risk-based approach to design a fit-for-purpose method and a validation plan that directly addresses its specific needs. The ATP serves as the foundation for the entire method lifecycle, facilitating science-based change management without extensive regulatory filings when supported by proper risk assessment [22].

Diagram 1: Method Validation Lifecycle with Risk Assessment

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Comparison of Methods Experiment

The comparison of methods experiment is critical for assessing the systematic errors that occur with real patient specimens, estimating inaccuracy or systematic error between a new method and a comparative method [24]. This experimental protocol directly addresses the risk of method inaccuracy impacting patient safety.

Experimental Design:

- Specimen Requirements: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens should be tested by the two methods, selected to cover the entire working range and represent the spectrum of diseases expected in routine application [24]. Specimen quality and range coverage are more critical than quantity alone.

- Time Period: The experiment should include several different analytical runs on different days (minimum of 5 days recommended) to minimize systematic errors that might occur in a single run [24].

- Measurement Approach: Common practice is to analyze each specimen singly by both methods, though duplicate measurements provide advantages for identifying sample mix-ups, transposition errors, and other mistakes [24].

- Comparative Method Selection: When possible, a reference method should be chosen whose correctness is well-documented. With routine methods, large differences may require additional experiments to identify which method is inaccurate [24].

Data Analysis Protocol:

- Graphical Analysis: Create difference plots (test minus comparative results versus comparative result) or comparison plots (test result versus comparative result) to visually inspect data patterns and identify discrepant results [24].

- Statistical Calculations: For data covering a wide analytical range, use linear regression statistics (slope, y-intercept, standard deviation of points about the line) to estimate systematic error at medical decision concentrations [24].

- Bias Calculation: For narrow analytical ranges, calculate the average difference between results (bias) using paired t-test calculations [24].

Validation of Screening Methods

For qualitative screening methods, validation focuses on different performance metrics related to classification accuracy, with specific experimental protocols to address risks of false positives and false negatives [25].

Experimental Design:

- Sample Set: A validation set of reference samples with a minimum of 20 samples for each class recommended to ensure representativeness [25].

- Contingency Analysis: Results are displayed in a contingency table comparing method results against reference values, calculating sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values [25].

- Applicability Indicators: Proposed indicators including error index, saving index, penalty index, and loss index to evaluate real-world performance in specific scenarios [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Reagent/ Material | Technical Function | Validation Application | Risk Mitigation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provides known concentration for accuracy determination [26] | Calibration curve construction, accuracy assessment | Ensures traceability and prevents systematic bias |

| Placebo Formulations | Blank matrix without active ingredient | Specificity testing, interference checking [22] | Confirms method selectively measures analyte |

| System Suitability Solutions | Verifies instrument performance before analysis | Precision validation, system verification [22] | Prevents instrument-related failures during validation |

| Stability Samples | Evaluates analyte durability under various conditions | Forced degradation studies, robustness assessment [22] | Identifies method vulnerabilities to environmental factors |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitors ongoing method performance | Precision studies, intermediate precision validation [22] | Detects method drift and analyst-to-analyst variability |

Quantitative Impact: Validation as Risk Reduction

The business case for method validation is substantiated by quantitative outcomes demonstrating risk reduction across multiple dimensions. Organizations implementing risk-based validation typically reduce unnecessary testing by 30-45% while maintaining or improving quality outcomes [23]. Case studies document specific financial impacts, with one medical center reporting savings of $2.3 million after implementing risk-based protocols that prioritized critical parameters while eliminating redundant tests [23].

Diagram 2: Validation Investment and Return Relationship

Analytical method validation represents far more than a regulatory requirement—it is a fundamental business strategy that systematically reduces risk while ensuring patient safety. By implementing modern, risk-based validation approaches aligned with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines, organizations achieve dual objectives: substantial operational efficiencies quantified at 30-45% reduction in unnecessary testing, and robust patient protection through reliable analytical data. The validation lifecycle model, anchored by the Analytical Target Profile and continuous monitoring, provides a framework for maintaining method reliability throughout a product's commercial life. As pharmaceutical manufacturing evolves toward more complex modalities and global supply chains, the business case for rigorous method validation grows increasingly compelling, ultimately delivering value through protected patient health and sustainable business operations.

Core Validation Parameters and Practical Implementation Strategies

Within the framework of analytical method validation research, establishing the accuracy of an assay is paramount. Accuracy, defined as the closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true reference value, is quantitatively assessed through spike-and-recovery experiments [27]. This guide details the role of these experiments in validating immunoassays such as ELISA, providing in-depth technical protocols, data interpretation guidelines, and troubleshooting strategies essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The core postulate is that a well-validated method must demonstrate that the sample matrix does not interfere with the accurate detection and quantification of the analyte, thereby ensuring the reliability of data used in critical decision-making processes [28] [29].

Core Principles and Definitions

The Purpose of Spike-and-Recovery Assessment

The fundamental purpose of a spike-and-recovery experiment is to determine whether the detection of an analyte is affected by differences between the matrix used for the standard curve and the biological sample matrix [27]. In an ideal assay, the response for a given amount of analyte would be identical whether it is in the standard diluent or the sample matrix. However, components within a complex biological sample (e.g., serum, plasma, urine, or cell culture supernatant) can alter the assay response, leading to either an overestimation or underestimation of the true analyte concentration [29]. This experiment involves adding ("spiking") a known quantity of the pure analyte into the natural sample matrix and then measuring the amount recovered by the assay [27] [28].

Relationship with Other Validation Parameters

Spike-and-recovery is intrinsically linked to other parameters in method validation:

- Dilutional Linearity: Determines if a sample spiked with analyte above the upper limit of detection can be reliably quantified after serial dilution within the assay's standard curve range [28]. It confirms assay flexibility and accuracy across dilutions.

- Parallelism: Assesses whether samples with high endogenous levels of the analyte provide the same degree of detection as the standard curve analyte after dilution, indicating comparable immunoreactivity [28].

Poor performance in any of these areas indicates potential matrix interference, which can stem from factors like pH, salt concentrations, detergents, or background proteins that affect antibody-binding affinity [28].

Experimental Methodology

Detailed Experimental Protocol

A robust spike-and-recovery experiment follows a structured protocol. The workflow below outlines the key stages from sample preparation to final calculation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For each type of sample matrix to be validated, prepare a "neat" (undiluted) sample and/or a sample diluted in the chosen sample diluent to its Minimum Required Dilution (MRD) [29].

- Spiking: Spike a known amount of the pure standard analyte into the sample matrix. It is recommended to use 3-4 concentration levels covering the analytical range of the assay, ensuring the lowest is at least 2 times the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) [29].

- Example: Spike 100 µL of a 100 ng/mL standard into 400 µL of the neat sample. This results in a 1:5 dilution and a final theoretical spike concentration of 20 ng/mL [29].

- Control Preparation: In parallel, prepare a control by spiking the same known amount of analyte into the standard diluent used for the standard curve. Also, prepare a "zero-spike" control for the sample matrix (sample + diluent without analyte) to account for any endogenous levels of the analyte [27] [29].

- Assay Execution: Run the complete ELISA procedure for all spiked samples, controls, and the standard curve.

- Calculation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials required for performing a spike-and-recovery experiment.

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Purified Analyte Standard | A known quantity of the pure protein or analyte is used to spike the sample. This serves as the reference "true value" for calculating recovery [27] [29]. |

| Appropriate Sample Matrix | The actual biological sample (e.g., serum, urine, cell culture supernatant) being validated. Its unique composition is the source of potential interference [27]. |

| Standard Diluent | The buffer used to prepare the standard curve. Optimizing its composition to match the sample matrix (e.g., by adding a carrier protein like BSA) can mitigate recovery issues [27]. |

| Sample Diluent | The buffer used to dilute the sample. It may differ from the standard diluent and is optimized to reduce matrix effects while maintaining analyte detectability [27]. |

| Validated ELISA Kit/Reagents | Includes the pre-coated plate, detection antibodies, and enzyme conjugate. The assay must be robust and characterized (LOD, LOQ, dynamic range) before spike-recovery assessment [29]. |

Data Interpretation and Acceptance Criteria

Interpreting Spike-and-Recovery Results

The calculated percentage recovery indicates the degree of matrix interference. According to ICH, FDA, and EMA guidelines on analytical procedure validation, recovery values within 75% to 125% of the spiked concentration are generally considered acceptable [29]. Recovery outside this range indicates significant interference.

- Under-Recovery (<75%): Suggests components in the sample matrix are inhibiting antibody binding or the analyte is being sequestered, leading to an underestimation of the true concentration [29].

- Over-Recovery (>125%): May indicate non-specific binding of matrix components to assay reagents or interaction of the drug substance with antibodies, causing an overestimation [29].

Representative Data Tables

The following tables illustrate how spike-and-recovery and linearity-of-dilution data are typically structured and analyzed.

Table 1: Example ELISA Spike-and-Recovery Data for Recombinant Human IL-1 beta in Human Urine Samples (n=9)

| Sample | No Spike (0 pg/mL) | Low Spike (15 pg/mL) | Medium Spike (40 pg/mL) | High Spike (80 pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Control | 0.0 | 17.0 | 44.1 | 81.6 |

| Donor 1 | 0.7 | 14.6 | 39.6 | 69.6 |

| Donor 2 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 41.6 | 74.8 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Mean Recovery (± S.D.) | NA | 86.3% ± 9.9% | 85.8% ± 6.7% | 84.6% ± 3.5% |

Data adapted from a representative experiment [27].

Table 2: Summary of Linearity-of-Dilution Results for a Human IL-1 beta Sample

| Sample | Dilution Factor (DF) | Observed (pg/mL) × DF | Expected (Neat Value) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConA-stimulated Cell Culture Supernatant | Neat | 131.5 | 131.5 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 149.9 | 114 | ||

| 1:4 | 162.2 | 123 | ||

| 1:8 | 165.4 | 126 |

Data adapted from a representative experiment. Note that recoveries outside the 80-120% range indicate poor linearity at higher dilutions [27].

Troubleshooting and Assay Optimization

Correcting Poor Spike-and-Recovery Results

When recovery falls outside the acceptable range, the following optimization strategies can be employed, as visualized in the troubleshooting pathway below.

Specific corrective actions include:

- Alter the Sample Matrix: If a neat biological sample produces poor recovery, diluting it (e.g., 1:1) in the standard diluent or a logical sample diluent often corrects the issue [27]. Other adjustments include modifying the pH to match the standard diluent or adding a carrier protein like BSA to stabilize the analyte [27].

- Alter the Standard Diluent: The composition of the standard diluent can be modified to more closely resemble the sample matrix. For instance, if analyzing culture supernatants, using culture medium as the standard diluent may improve recovery. However, this may compromise the assay's signal-to-noise ratio, requiring a balance to be struck [27].

Spike-and-recovery analysis is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical component of qualifying an immunoassay for use in regulated environments. It provides essential validation of assay accuracy, confirming that the method reliably measures the true analyte concentration in the presence of a complex sample matrix. As per regulatory guidelines, this experiment must be performed for each unique sample type evaluated and repeated if the manufacturing process changes [29]. When integrated with other validation parameters such as precision, sensitivity, and dilutional linearity, spike-and-recovery studies form the bedrock of a fit-for-purpose analytical method, ensuring the generation of reliable and defensible data for research and drug development.