Beyond Trial and Error: A Strategic Guide to Design of Experiments (DoE) for Robust Analytical Method Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to implement Design of Experiments (DoE) in analytical method development.

Beyond Trial and Error: A Strategic Guide to Design of Experiments (DoE) for Robust Analytical Method Development

Abstract

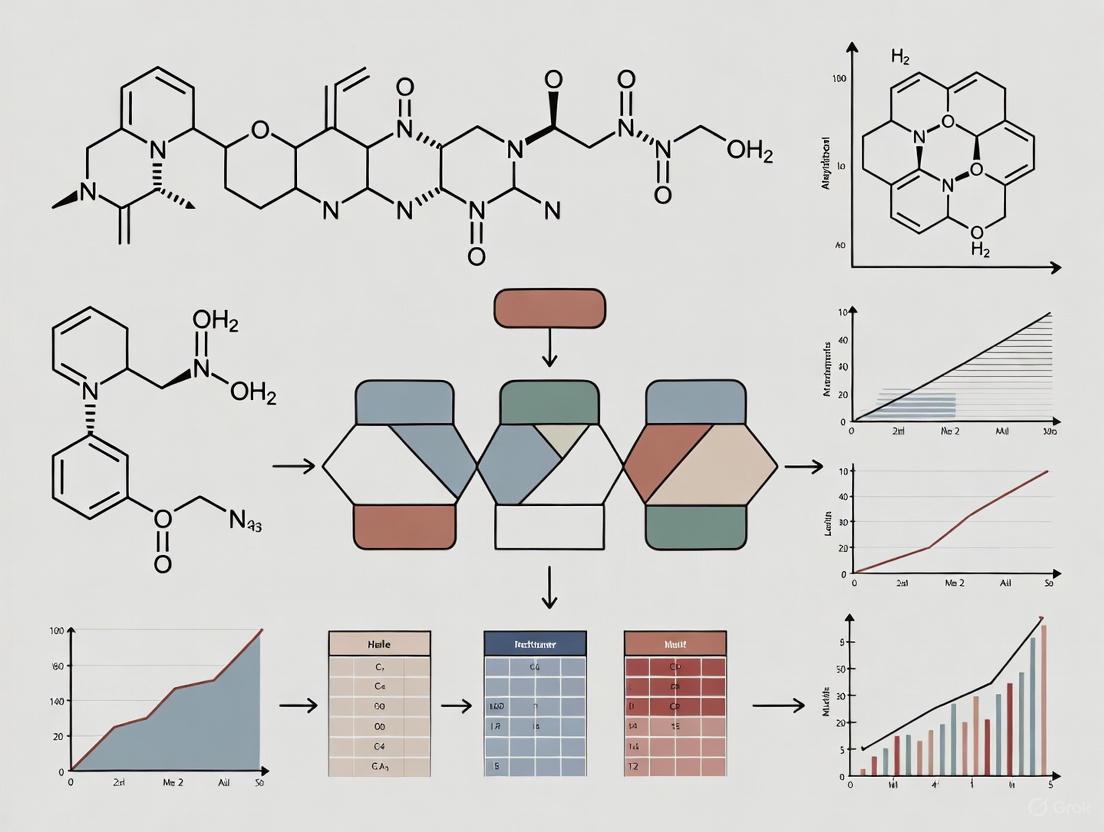

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to implement Design of Experiments (DoE) in analytical method development. Moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches, we explore the foundational principles of DoE, detail a step-by-step methodological workflow from risk assessment to execution, and offer strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. The content further guides readers on integrating DoE with regulatory guidelines for method validation and demonstrates its comparative advantages through case studies, ultimately aiming to enhance precision, reduce bias, and accelerate the development of robust, reliable analytical methods.

Shifting from OFAT to DoE: Building a Foundation for Smarter Experimentation

Why One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Fails in Complex Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Common OFAT Pitfalls and DOE Solutions

This guide helps researchers identify and resolve common problems encountered when using the One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach in complex development environments, such as pharmaceutical method development.

| Problem Scenario | Why It Happens with OFAT | Recommended Solution using DOE |

|---|---|---|

| Failed method transfer or irreproducible results in a new lab. | OFAT fails to identify interactions between factors (e.g., how room temperature affects a reagent's efficacy). The method is only optimized for one specific, unchanging background [1]. | Use a factorial design to actively study and model factor interactions. This builds robustness into the method from the start, making it less sensitive to environmental changes [1] [2]. |

| Sub-optimal performance; unable to hit peak efficiency, yield, or purity targets. | OFAT explores a very limited experimental space. The "optimum" found is often just a local peak, while a much better global optimum remains undiscovered [3] [2]. | Employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with designs like Central Composite or Box-Behnken. This creates a model to navigate the factor space and locate the true optimal conditions [1] [4]. |

| Lengthy, costly development cycles with too many experiments. | OFAT is inherently inefficient. Studying 5 factors at 3 levels each requires 121+ experiments, with each providing information on only a single factor [1] [5]. | Use screening designs (e.g., fractional factorials). These studies multiple factors simultaneously in a minimal number of runs, quickly identifying the most influential factors [3] [4]. |

| Unexpected results when scaling up a process from lab to production. | The effect of a factor can change at different scales. OFAT, which assumes factor effects are constant and independent, cannot detect or predict this [1]. | Use DOE principles (blocking) to explicitly account for scale as an experimental factor. This allows you to model and understand how factor effects change with batch size or equipment [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Our team has always used OFAT successfully. Why should we switch to DOE now?

While OFAT can work for simple problems with isolated factors, it is fundamentally unsuited for complex systems. In drug development, factors like pH, temperature, and buffer concentration rarely act independently; they interact. DOE is a structured, statistically sound framework that systematically accounts for these interactions. It transforms development from a slow, sequential process into an efficient, parallel one, saving significant time and resources while leading to more robust and optimized outcomes [1] [3] [5].

2. We tried a DOE screening design and found that nothing was statistically significant. Was this a waste of resources?

Not at all. This is valuable information. A well-executed DOE that rules out several potential factors is highly efficient. It prevents you from wasting further resources investigating dead ends. With OFAT, you might have spent weeks or months testing each of those factors individually to reach the same conclusion. The DOE gave you a definitive, data-driven answer in a fraction of the time, allowing you to pivot your research strategy more quickly [3].

3. How does DOE specifically help with analytical method validation, as per ICH guidelines?

The FDA's draft guidance on analytical procedures encourages a systematic approach to method robustness testing [6]. DOE is the ideal tool for this. Instead of varying one parameter at a time in a robustness test, a well-designed experimental matrix can efficiently vary all critical method parameters (e.g., flow rate, column temperature, mobile phase pH) simultaneously. This not only confirms that the method is robust within a predefined operating range but also quantifies the effect of each parameter and their interactions, providing a much higher level of assurance than OFAT [6] [4].

4. The math behind DOE seems daunting. Do we need expert statisticians to use it?

While having statistical support is beneficial, it is not always a barrier to entry. Modern, user-friendly DOE software has made the design and analysis of experiments more accessible to scientists and engineers without deep statistical training [3] [5]. Furthermore, the cost of not using DOE—in terms of failed experiments, prolonged development timelines, and sub-optimal products—is often far greater than the cost of acquiring training or software [1] [3].

5. Can you give a real-world example of how DOE outperforms OFAT?

A classic example is optimizing a chemical reaction for yield. An OFAT approach might hold pH constant while testing temperature, then hold the "best" temperature constant while testing pH. However, if there is an interaction (e.g., the ideal temperature is different for acidic vs. basic conditions), OFAT will completely miss the true optimal combination. A factorial DOE would vary temperature and pH together in a structured pattern, immediately revealing this interaction and leading to a higher yield than what OFAT could ever find [2].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Screening Design with Fractional Factorial

Objective: To efficiently identify the most influential factors affecting a critical quality attribute (e.g., assay purity) from a large set of potential variables.

Methodology:

Define the Scope:

- Response: Clearly define the measured outcome (e.g.,

% Purity). - Factors: List all potential factors to investigate (e.g.,

Reaction Time,Catalyst Amount,Temperature,Stirring Speed,Solvent Ratio). Typically, choose 5-7 factors. - Levels: For a screening design, select two levels for each factor (e.g.,

LowandHigh), representing a reasonable operating range.

- Response: Clearly define the measured outcome (e.g.,

Design the Experiment:

- Use statistical software to generate a Fractional Factorial Design. This design carefully selects a subset of all possible factor-level combinations, allowing you to estimate main effects efficiently while "confounding" interactions with each other (which is acceptable for screening).

- The software will output a randomized run order. Randomization is critical to avoid bias from lurking variables [1].

Execution:

- Conduct the experiments strictly in the randomized order provided by the design.

- Precisely control all factor levels and meticulously record the response for each run.

Analysis:

- Input the results into the DOE software.

- Generate a Half-Normal Plot or a Pareto Chart of the standardized effects. These plots visually help distinguish significant factors from random noise.

- Factors that stand out from the "line of noise" are deemed significant. A simplified example of the output is shown in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and concepts crucial for moving from OFAT to effective DOE practices.

| Item/Concept | Function & Relevance in DOE |

|---|---|

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | A response surface design used for building a quadratic model to locate optimal conditions. It efficiently explores curvature in the response [1] [4]. |

| Factorial Design | The foundational building block of most DOEs. It studies the effects of several factors simultaneously by testing all possible combinations of their levels, enabling the detection of interactions [1] [2]. |

| Fractional Factorial Design | A derivative of the full factorial used for screening. It sacrifices the ability to estimate some higher-order interactions to dramatically reduce the number of required runs when many factors are involved [3] [4]. |

| Randomization | A core principle of DOE. Conducting experimental runs in a random order helps to neutralize the effects of unknown or uncontrollable "lurking" variables, ensuring the validity of the statistical analysis [1]. |

| Replication | Repeating experimental runs under identical conditions. This allows for the estimation of pure experimental error, which is necessary for determining the statistical significance of effects [1]. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) | A collection of statistical and mathematical techniques used to model and analyze problems where a response of interest is influenced by several variables, with the goal of optimizing this response [1] [2]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, Design-Expert) | Essential tools for generating efficient experimental designs, randomizing run orders, analyzing complex datasets, and visualizing interaction effects and response surfaces [5] [2]. |

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering the Design of Experiments (DoE) is critical for efficient and robust analytical method development and validation. DoE provides a structured framework for planning, conducting, and analyzing controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [7]. This technical support center guide outlines the core principles of DoE, provides troubleshooting advice, and details experimental protocols to help you implement this powerful methodology in your research.

Understanding the Core Principles of DoE

The design of experiments is built upon three fundamental principles: randomization, replication, and blocking. These form the bedrock of a statistically sound experiment [8].

- Randomization: This refers to running your experimental trials in a random order. Its primary purpose is to prevent systematic biases by averaging out the effects of uncontrolled (or "lurking") variables that could otherwise confound your results. For example, if you run all tests for one factor level in the morning and another in the afternoon, time-dependent variables like ambient temperature could falsely be attributed to your factor. Randomization helps avoid this confusion [8].

- Replication: This involves repeating the same experimental conditions one or more times. It is crucial because it allows you to obtain an estimate of the experimental error—the unexplained variation in your response when factor settings are identical. This estimate of error is necessary for testing the statistical significance of your effects. Note that true replication means applying the same treatment to more than one experimental unit; repeated measurements on the same unit constitute pseudo-replication [8].

- Blocking: This is a technique used to reduce or control variability from known but irrelevant nuisance factors. If an experiment must be conducted across different batches, days, or machines, these can introduce unwanted variation. By dividing the experiment into blocks (e.g., performing a subset of runs each day), you can account for this block-to-block variation in your analysis, thereby increasing the precision with which you can detect your important effects [8] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and purpose of these three core principles:

Key Terminology and Concepts

Before designing an experiment, it is essential to understand the key terminology [10]:

- Factors: These are the independent variables that you can control and change during the experiment (e.g., column temperature, pH, flow rate). Each factor is tested at different "levels" (e.g., a high and a low setting).

- Responses: These are the dependent variables—the outcomes or results you are measuring (e.g., peak area, retention time, yield, purity).

- Interactions: This occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor. Capturing interactions is a key advantage of DoE over the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach.

- Main Effect: The average change in the response caused by changing a single factor's level, averaged over the levels of other factors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why should I use DoE instead of the traditional "One-Factor-at-a-Time" (OFAT) approach?

A: The OFAT approach involves changing one variable while holding all others constant. While seemingly straightforward, it is inefficient and, critically, fails to identify interactions between different factors [10]. This can lead to methods that are fragile and perform poorly when minor variations occur. DoE, by contrast, simultaneously investigates multiple factors, revealing these critical interactions and leading to more robust and reliable methods in less time [10].

Q2: How do I choose which factors to include in my DoE?

A: You should include any variable you believe could influence the method's performance, based on prior knowledge, experience, or preliminary experiments [10]. A risk assessment of the analytical method is a recommended practice to identify and risk-rank factors (e.g., 3 to 8 factors) that may influence key responses like precision and accuracy [11].

Q3: My factor is very hard or costly to change (e.g., oven temperature). Can I still use DoE?

A: Yes. While full randomization is ideal, practical constraints sometimes make it impossible. In such cases, you can use designs like split-plot or strip-plot experiments, which use a form of restricted randomization specifically for hard-to-change factors [8].

Q4: What is the minimum number of experimental runs required?

A: For a screening design with n factors, a full factorial design requires 2^n runs. For example, with 3 factors, you need 8 runs [7]. However, if you have many factors, you can use more efficient fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs to screen for the most important factors with fewer runs [10].

Q5: I have limited experimental units. Can I take multiple measurements from the same unit to increase replication?

A: No. Applying different treatments to an individual experimental unit and taking multiple measurements constitutes pseudo-replication. True replication requires applying the same treatment to more than one independent experimental unit [8].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: A Basic 2-Factor Full Factorial Design

This is a fundamental protocol for investigating two factors and their potential interaction [7].

- Define the Problem: Clearly state the objective. Example: "Optimize the glue bond strength by understanding the effects of Temperature and Pressure."

- Select Factors and Levels: Choose realistic high and low levels for each factor.

- Factor A (Temperature): -1 Level = 100°C, +1 Level = 200°C

- Factor B (Pressure): -1 Level = 50 psi, +1 Level = 100 psi

- Create the Design Matrix: This matrix shows all possible combinations of the factor levels.

| Experiment # | Temperature | Pressure | Coded A | Coded B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100°C | 50 psi | -1 | -1 |

| 2 | 100°C | 100 psi | -1 | +1 |

| 3 | 200°C | 50 psi | +1 | -1 |

| 4 | 200°C | 100 psi | +1 | +1 |

- Run Experiments: Conduct the trials in a randomized order to prevent bias.

- Measure Response: Record the response (e.g., bond strength in lbs) for each run.

- Analyze Data: Calculate the main effects and interaction effect.

Protocol 2: Sequential DoE for Method Development

A recommended workflow for analytical method development is a sequential approach [11] [10] [7], as shown in the following workflow:

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Define Purpose and Goals: Align the experiment structure with its purpose (e.g., improving repeatability, intermediate precision, or accuracy) [11]. Determine the responses and the range of concentrations to be evaluated.

- Perform a Risk Assessment: Identify all materials, equipment, method steps, and analyst techniques that may influence the key responses. The outcome is a shortlist of risk-ranked factors for experimental investigation [11].

- Screening Design: When many factors (e.g., 5-8) are initially considered, use a highly efficient design like a Fractional Factorial or Plackett-Burman design. The goal is to identify the "vital few" factors that have significant effects on the response [10].

- Characterization and Optimization: Once the key factors (typically 2-4) are identified, use a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design, such as Central Composite or Box-Behnken, to model the response in more detail and find the optimal factor settings [10].

- Validation: Finally, run confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model. Document the final method parameters and the established "design space" [11] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and concepts essential for planning and executing a DoE in an analytical method development context.

| Item/Concept | Category | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Reagent | Well-characterized standards are crucial for determining method bias and accuracy. Their stability is a key consideration [11]. |

| Mobile Phase Components | Reagent | In chromatography, the composition of the mobile phase (e.g., pH, buffer concentration, organic modifier ratio) is a common factor in a DoE [10]. |

| Chromatographic Column | Equipment | The column type (e.g., C18, phenyl), temperature, and flow rate are frequent factors investigated for their effect on resolution and retention time [10]. |

| Design Matrix | Concept | A table representing the set of design points (unique combinations of factor levels) to be used in the experiment. It is the blueprint for your DoE [9] [7]. |

| Random Number Generator | Tool | Used to determine the random order of experimental runs, which is critical for implementing the randomization principle and reducing bias [8]. |

| Blocking Variable | Concept | A known source of nuisance variation (e.g., different reagent batches, analysis days, instruments) that is systematically accounted for in the experimental design to improve precision [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between a factor and a response? In Design of Experiments (DoE), a factor (also called an independent or input variable) is a process parameter that the investigator deliberately manipulates to observe its effect on the output [9] [12]. Common examples include temperature, pressure, or material concentration. The response (or dependent variable) is the measurable output that is presumably influenced by changing the factor levels [13] [12]. In pharmaceutical development, a critical quality attribute (CQA), such as tablet potency or dissolution rate, is a typical response [14] [15].

2. Why is it important to use continuous responses when possible? Continuous data (e.g., weight, concentration, yield) contain much more information than categorical data (e.g., pass/fail). Because experiments are often performed with a limited number of runs, continuous responses allow you to learn more about the process and build more predictive models with the same amount of data [13].

3. What is a "Design Space"? The Design Space is a key concept in Quality by Design (QbD). It is defined as the "multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables (e.g., material attributes) and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality" [14] [16]. Working within the approved Design Space is not considered a regulatory change, providing operational flexibility [14].

4. Is Design of Experiments (DoE) the same as a Design Space? No, this is a common misconception. DoE is a statistical method used to generate data on how factors affect responses. A Design Space is the knowledge-based region of successful operation, which is often defined using the models and understanding developed from a DoE [16].

5. How do I handle multiple, potentially conflicting, responses? It is common and often desirable to measure multiple responses in a single experiment. The goals for each response (e.g., maximize, minimize, target) are defined first. Statistical software then uses optimization techniques to find the best compromise factor settings. You can assign importance weights to the responses to guide the optimization; for example, stating that minimizing impurities is five times more important than maximizing yield [13] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unclear or Unmeasurable Responses

Problem: Your experimental results are inconsistent or cannot be reliably interpreted.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poorly defined response.

- Solution: Ensure each response is a specific, measurable outcome directly related to your experimental objective. Instead of "good quality," use a quantifiable measure like "percentage purity" [13].

- Cause: Incapable measurement system.

- Solution: Before running the experiment, conduct a measurement system analysis (e.g., a Gage R&R study) to ensure your measurement tool is both accurate and precise. Excessive variation in the measurement itself can obscure real process effects [13].

Issue 2: Failure to Detect Important Factor Interactions

Problem: The conclusions from your experiment do not hold up in practice, or you fail to find an optimal setting.

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: Using a "One Factor at a Time" (OFAT) approach.

- Solution: Use a designed experiment that varies multiple factors simultaneously. OFAT approaches are inefficient and cannot detect interactions between factors, which is when the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor [14] [2]. A factorial design is the standard solution for detecting interactions.

Issue 3: Defining and Working with a Design Space

Problem: Uncertainty about how to establish or operate within a Design Space.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unclear boundaries.

- Cause: Confusing safe operating region with characterized space.

- Solution: Understand that the entire area within the Design Space is a mean response model. To ensure low failure rates during routine production, use simulation to account for normal variation in your factors and identify the most robust set points within the Design Space [16].

Key Experiment Protocols

Protocol 1: Screening Design to Identify Critical Factors

Objective: To efficiently identify the few critical factors from a long list of potential variables that significantly affect your responses. Methodology: Use a Fractional Factorial design (e.g., a Resolution IV design). This type of design requires a relatively small number of experimental runs and can clearly identify main effects, although some interactions may be confounded [14] [12]. Typical Workflow:

- Define all potential factors and their high/low levels.

- Select an appropriate fractional factorial design.

- Randomize the run order to prevent bias.

- Execute the experiments and measure the responses.

- Analyze the data to identify which factors have statistically significant effects.

Protocol 2: Response Surface Methodology for Optimization

Objective: To model the relationship between your critical factors and responses and find the factor settings that optimize the responses. Methodology: Use a Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design. These designs are ideal for fitting quadratic models, which can capture curvature in the response surface and identify maximum, minimum, or saddle points [14] [2]. Typical Workflow:

- Select the 2-4 most critical factors identified from your screening design.

- Choose a response surface design (e.g., CCD).

- Run the experiments in random order.

- Fit a quadratic model to the data.

- Use contour plots and optimization algorithms to find the optimal factor settings.

Table 1: Common Design Types and Their Characteristics

| Design Type | Primary Purpose | Key Features | Typical Number of Runs (for k factors) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | Studying all main effects and interactions | Estimates all possible combinations; can become large | 2k |

| Fractional Factorial | Screening many factors efficiently | Studies only a fraction of the combinations; aliasing is present | 2k-1, 2k-2, etc. |

| Response Surface | Modeling curvature and finding optimum | Includes center and axial points for quadratic modeling | Varies (e.g., CCD: 2k + 2k + Cp) |

Table 2: Common Goals for Response Optimization

| Response Goal | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Maximize | Seek the highest possible value. | Maximize product yield in a chemical reaction [13]. |

| Minimize | Seek the lowest possible value. | Minimize the cost of a final product [13]. |

| Target | Achieve a specific value. | Match a specific potency for a pharmaceutical tablet (e.g., 200 mg ± 2 mg) [13]. |

Conceptual Workflows

DoE to Design Space Workflow

OFAT vs. DoE Approach

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioprocess DoE

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Provides the essential nutrients for cell growth. Its composition (e.g., types and concentrations of nutrients) is often a critical factor in bioprocess optimization studies [14]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintain a stable pH environment in a bioreactor. The pH level is a common Critical Process Parameter (CPP) that can significantly impact cell density and product quality [14]. |

| Critical Process Parameter (CPP) Standards | Used to calibrate equipment and ensure factors like temperature, dissolved oxygen, and agitation rate are accurately controlled and measured throughout the experiment [14] [16]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and scientists align Design of Experiments (DoE) with ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 guidelines for robust pharmaceutical development.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

DoE Methodology and Implementation

Q: What are the primary future applications of DoE in pharmaceutical development? A survey of industry professionals reveals the key planned uses for DoE. Process understanding and characterization is the foremost application [18].

| Future Purpose of DoE | Survey Response Rate |

|---|---|

| Process Understanding/Characterization | 71% |

| Process/Product/Business Optimization | 53% |

| Robustness Testing | 46% |

| Method Validation | 42% |

| Use in Regulatory Submissions | 12% |

Q: What common problems hinder effective DoE implementation in a GMP environment? While 68% of survey participants reported no specific problems, 32% cited several key issues [18]:

- Lack of experience or support

- Management does not support it

- Handling a large number of experiments

- Resistance to using DoE in a GMP environment

- DoE software is too expensive

- DoE is time-consuming

Q: How does a Quality by Design (QbD) approach integrate with analytical method development? The ICH Q14 guideline, which aligns with Q8, Q9, and Q10, introduces a paradigm shift. It establishes a structured, risk-based, and lifecycle-oriented approach for analytical procedures, moving away from static, one-time validation. A core principle is defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)—a set of required performance characteristics for the method—and using DoE to systematically develop a robust Method Operable Design Region (MODR) [19].

Regulatory Strategy and Compliance

Q: How do ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 work together as a system? These guidelines form an integrated foundation for a modern Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) [20]. ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development) provides the systematic approach for design and development, ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management) offers the tools for risk-based decision-making, and ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System) describes the enabling system for product lifecycle management [21] [20]. Their relationship is a continuous cycle.

Q: What is the role of DoE in forming a control strategy? DoE is a central tool for building process understanding. It helps establish the relationship between Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), which are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be controlled to ensure product quality [22]. This knowledge directly enables the creation of a science-based and risk-based control strategy, as outlined in ICH Q8(R2) [20].

Analytical Development and Validation

Q: How do I identify and monitor Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) for a biological product? Identification of CQAs is an iterative process that begins early in development and is finalized during commercial process development [22].

- Start with a risk assessment following ICH Q9 principles, using a scoring system based on the attribute's impact on safety/efficacy and the level of uncertainty [22].

- Leverage literature and prior knowledge for early-stage identification.

- Use process characterization studies to assess the variability of identified CQAs.

- For monitoring, employ control charts with statistical limits, compare batch trends to historical data, and formally investigate out-of-trend results [22].

Q: What strategies can accelerate analytical timelines without compromising compliance?

- Develop methods in parallel with the manufacturing process to ensure they are ready for batch release [22].

- Implement DoE to minimize the number of assay runs while comprehensively demonstrating method robustness [22].

- Adopt a phase-appropriate approach where methods are fit-for-purpose at each stage and evolve toward validation for commercialization [22].

- Invest in modern equipment and digital infrastructure (like a Laboratory Execution System) to reduce analysis time and errors [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

While DoE is a methodological framework, successful implementation relies on specific tools and conceptual "reagents".

| Tool/Solution | Function in DoE for Regulatory Compliance |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (e.g., Minitab) | Used to design experiments, model complex data, define the design space, and analyze robustness. It is the primary tool for executing and interpreting DoE [18]. |

| Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) | A prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product. It guides development and defines the target for all DoE studies, as per ICH Q8(R2) [21] [20]. |

| Analytical Target Profile (ATP) | Defines the required performance characteristics of an analytical procedure. It is the analog of the QTPP for method development and is central to the ICH Q14 paradigm [19]. |

| Risk Assessment Matrix | A foundational tool from ICH Q9 used to prioritize factors for DoE screening and to assess the criticality of quality attributes and process parameters [21] [20]. |

| Design Space / MODR | The multidimensional combination of material and process parameters (or analytical procedure parameters) within which consistent quality is assured. DoE is the primary methodology for its establishment [21] [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Employing DoE for Robust Method Development

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for using DoE to develop an analytical method, aligning with ICH Q8, Q9, and Q14.

1. Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

- Objective: Establish the foundational quality goal for the method.

- Procedure: Based on the QTPP and product knowledge, define the ATP. The ATP specifies the method performance requirements (e.g., precision, accuracy, specificity) without dictating the technical solution [19].

- Deliverable: A finalized ATP document.

2. Risk Assessment to Identify Critical Method Parameters

- Objective: Focus development efforts on high-risk factors.

- Procedure: Conduct a risk assessment per ICH Q9. Use a tool like a Risk Matrix to score potential method parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate, gradient time) based on their potential impact on the ATP criteria [22] [20].

- Deliverable: A prioritized list of potentially critical method parameters for experimental investigation.

3. Screen Critical Parameters via Fractional Factorial DoE

- Objective: Efficiently identify the most influential parameters.

- Procedure:

- Select the high-priority parameters from the risk assessment.

- Use a fractional factorial design (e.g., Plackett-Burman) to investigate these factors with a minimal number of experimental runs.

- Execute the experiments and analyze the data using statistical software to identify which factors have a significant effect on the method performance (responses linked to the ATP).

- Deliverable: A refined list of confirmed Critical Method Parameters.

4. Optimize and Define the Method Operable Design Region (MODR)

- Objective: Establish a robust operating space for the method.

- Procedure:

- Using the critical parameters, design a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) experiment (e.g., Central Composite Design).

- Model the data to understand the relationship between parameter settings and method performance.

- Use the model to define the MODR—the combination of parameter ranges within which the method meets all ATP criteria [19].

- Deliverable: A mathematical model and a defined MODR.

5. Validate and Document the Control Strategy

- Objective: Confirm method performance and ensure lifecycle management.

- Procedure:

- Perform validation exercises at points within the MODR to confirm the model's predictions.

- Document the entire development process, including the ATP, risk assessments, DoE designs, data, and the final model.

- Establish the ongoing control strategy for the method's lifecycle, which includes routine monitoring and a plan for managing changes within the MODR per ICH Q12 [19].

- Deliverable: A validated analytical procedure and a comprehensive development report for regulatory submission.

A Step-by-Step Blueprint for DoE in Method Development and Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary goal of defining the purpose and scope in a DoE for analytical method development? The primary goal is to establish a clear and unambiguous objective for the analytical method. This foundational step ensures that the subsequent experimental design, execution, and analysis are aligned with the specific needs of the method, such as whether it is intended for quantifying an impurity, assessing potency, or evaluating dissolution. A well-defined purpose guides the selection of factors, responses, and the overall experimental strategy, saving valuable time and resources [10] [11].

2. How does a poorly defined purpose affect the method development process? A poorly defined purpose can lead to a misdirected experimental design that fails to characterize the method's critical parameters. This can result in a method that is not robust, is difficult to transfer, and may require re-development, consuming significant time and materials. A clear purpose is essential for developing a method that is fit-for-use and meets regulatory expectations [10] [11].

3. What key elements should be included in the scope of an analytical method? The scope should clearly define the range of concentrations the method will be used to measure and the solution matrix it will be measured in. Defining this range establishes the characterized design space for the method, which dictates its future applicability. According to ICH Q2(R1), it is normal to evaluate at least five concentrations across this range during development and validation [11].

4. Why is a one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach insufficient compared to a DoE? The OFAT approach involves changing one variable while holding all others constant. It is inefficient and, critically, fails to identify interactions between different factors. These interactions are often the root cause of method fragility. DoE, by contrast, systematically investigates the effects of multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously, leading to a more robust and reliable method in fewer experiments [10].

5. How does defining the purpose relate to regulatory guidelines like ICH Q8 and Q9? Defining the purpose and scope is a direct application of the Quality by Design (QbD) principles outlined in ICH Q8(R2) and is supported by the risk management framework of ICH Q9. It demonstrates a science-based and systematic approach to method development, which is increasingly expected by regulatory bodies. This documented understanding can streamline the regulatory submission and approval process [11].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unclear Objectives | The goal of the method (e.g., precision, accuracy, linearity) is not specifically defined. | Re-consult with all stakeholders to define a single, measurable objective. The purpose (e.g., "to optimize for repeatability and intermediate precision") must drive the study design and sampling plan [11]. |

| Overly Broad Scope | Attempting to characterize the method for an unrealistically wide range of concentrations or sample matrices. | Perform a risk assessment to focus on the most relevant and critical ranges based on the method's intended use. Consider developing separate methods for vastly different scenarios [11]. |

| Inadequate Risk Assessment | Failure to identify all potential factors (materials, equipment, analyst technique) that could influence the method's results. | Conduct a formal risk assessment (e.g., using a Fishbone diagram) to identify and risk-rank 3-8 potential factors. This ensures the DoE investigates the most critical variables [11]. |

| Uncertainty in Responses | The key performance indicators (responses) to be measured are not aligned with the method's purpose. | Clearly determine the responses (e.g., peak area, resolution, CV%) during the planning phase. Ensure the data collection setup can capture the raw data needed to calculate these statistics [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Defining Purpose and Scope

1. Define the Purpose of the Method Experiment:

- Clearly state the objective. Is the focus on repeatability, intermediate precision, accuracy, linearity, or resolution? The structure of the study, the sampling plan, and the factor ranges all depend on this defined purpose [11].

- Example Purpose Statement: "The purpose of this method is to quantitatively determine the concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in a tablet formulation, with optimization focused on precision and accuracy over a range of 80-120% of the label claim."

2. Define the Range of Concentrations and Solution Matrix:

- Establish the upper and lower limits of the concentration that the method will measure.

- Define the solution matrix (e.g., placebo-blended solution, biological fluid, dissolution medium) in which the measurements will be made.

- This defined range generates the characterized design space, so it should be selected carefully to ensure the method is fit for its intended use [11].

3. Identify All Steps in the Analytical Method:

- Document the complete flow or sequence of the analytical procedure.

- List all steps, including standard operating procedures (SOPs), chemistries, reagents, materials, instruments, and equipment used [11].

4. Determine the Responses:

- Identify the specific, measurable responses that are aligned with the purpose of the study.

- Examples include raw data (e.g., peak area, retention time) and statistical measures (e.g., bias, intermediate precision, signal-to-noise ratio, coefficient of variation (CV)) [11].

5. Perform a Risk Assessment:

- Systematically evaluate all materials, equipment, analysts, and method components to identify factors that may influence the key responses.

- The outcome should be a small set (3-8) of risk-ranked factors (e.g., pH of mobile phase, column temperature, flow rate) that will be investigated in the DoE [11].

Workflow Diagram: Defining Purpose & Scope

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent & Material Solutions

| Item | Function in Method Development |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized materials used to determine method bias and accuracy. Their stability and proper storage are critical [11]. |

| Solution Matrix Components | Placebo or blank solution that mimics the sample composition without the analyte. Used to define the method's scope and test for specificity and interference. |

| Chromatographic Materials | Includes columns, mobile phase solvents, and buffers. These are critical factors often investigated in a DoE for HPLC/UPLC method development [10] [11]. |

| Calibrators and Controls | Solutions of known concentration used to establish the calibration curve and to monitor the performance of the method during development and validation. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use a Risk Assessment with DoE instead of testing one factor at a time? Testing one factor at a time (OFAT) is inefficient and fails to identify how factors interact with each other. These interactions are often the hidden cause of method failure when conditions change slightly. A DoE-based risk assessment allows you to systematically study multiple factors and their interactions simultaneously, leading to a more robust and reliable method [10].

Q2: How do I decide which factors to include in the risk assessment? You should include any variable you suspect could influence your method's key performance outcomes (responses). This selection is based on prior knowledge, experience, or preliminary screening experiments. It is better to include a factor and later find it is not significant than to omit a critical one that affects method robustness [10].

Q3: What is the difference between a screening design and an optimization design? Screening designs (e.g., Fractional Factorial, Plackett-Burman) are used in the initial phase of risk assessment when you have many potential factors. They efficiently identify the few critical factors that have the most significant impact on your results. Once these key factors are identified, optimization designs (e.g., Response Surface Methodology) are used to find their ideal levels or "sweet spot" for the method [10].

Q4: My DoE analysis shows two factors have an interaction. What does this mean? An interaction occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor. For example, a change in flow rate might affect your chromatographic peak shape differently at a low temperature than at a high temperature. Identifying interactions is crucial for developing a robust method, as it allows you to define operating conditions that are resilient to such joint effects [10].

Q5: How many experimental runs are typically needed for a risk assessment? The number of runs depends on the design you choose. A Full Factorial design for 3 factors at 2 levels each requires 8 runs. However, a Fractional Factorial design can investigate 7 factors in only 8 runs, making it highly efficient for screening. The goal of DoE is to gain maximum information from a minimum number of experiments [10] [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The risk assessment did not identify any significant factors.

- Potential Cause 1: The range chosen for the factor levels (e.g., high and low values) was too narrow.

- Solution: Widen the range of the factor levels to increase the likelihood of observing a measurable effect on the response.

- Potential Cause 2: The measurement system for the response (e.g., analytical instrument) has high variability or poor precision.

- Solution: Ensure your measurement system is capable and calibrated. Investigate the source of variability before proceeding.

- Potential Cause 3: A key factor was omitted from the experimental design.

- Solution: Revisit the risk assessment brainstorming process. Use techniques like Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagrams to ensure all potential factors are considered.

Problem: The model from the DoE has a low predictive value.

- Potential Cause 1: Significant curvature exists in the response that a linear model (often used in screening) cannot capture.

- Solution: After initial screening, add center points to your experimental design to detect curvature. If found, move to an optimization design like a Central Composite Design that can model it.

- Potential Cause 2: Important factor interactions were not included in the model.

- Solution: Re-analyze the data to include interaction terms in the statistical model. Use a Full Factorial design if interactions are suspected to be widespread.

- Potential Cause 3: Excessive random noise or error in the experimental process.

- Solution: Control experimental conditions more strictly and ensure proper randomization to minimize the impact of lurking variables.

Problem: The optimal conditions predicted by the DoE do not yield the expected results in validation.

- Potential Cause 1: The model was extrapolated beyond the experimental region it was built on.

- Solution: Always perform confirmation runs within the experimental region defined by your DoE. Avoid predicting optimal conditions outside your tested factor ranges.

- Potential Cause 2: An uncontrolled factor changed between the DoE execution and the validation run.

- Solution: Document and control all known environmental and procedural variables, such as reagent supplier, analyst, or ambient temperature/humidity.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Screening for Critical Factors using a Fractional Factorial Design

Objective: To efficiently identify the few critical factors affecting method performance from a larger list of potential variables.

Methodology:

- Define the Problem: Clearly state the method being developed and the Key Performance Indicators (responses), such as resolution, yield, or peak tailing [10].

- Select Factors and Levels: Choose the factors to investigate and define a "low" and "high" level for each. For example:

- Factor A: pH (Levels: 7.0 and 7.6)

- Factor B: Temperature (Levels: 25°C and 35°C)

- Factor C: Concentration (Levels: 10 mM and 20 mM) [10]

- Choose the Experimental Design: Select a Fractional Factorial design (e.g., a 2^(4-1) design requiring 8 runs for 4 factors) [23].

- Conduct Experiments: Run the experiments in a fully randomized order to minimize the effect of uncontrolled variables [10].

- Analyze the Data: Input the results into statistical software. Analyze the main effects and interaction effects to identify which factors have a statistically significant impact on your responses [10] [23].

Table 1: Example Fractional Factorial Design Matrix (2^(3-1)) with Hypothetical Response Data This design demonstrates how 4 experimental runs can efficiently screen 3 factors.

| Run Order | Factor A: pH | Factor B: Temp (°C) | Factor C: Conc. (mM) | Response: Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low (7.0) | Low (25) | High (20) | 1.5 |

| 2 | High (7.6) | High (35) | High (20) | 2.2 |

| 3 | High (7.6) | Low (25) | Low (10) | 1.1 |

| 4 | Low (7.0) | High (35) | Low (10) | 1.8 |

Protocol 2: Quantifying Factor Effects using a Full Factorial Design

Objective: To quantify the main effects and all two-factor interactions for a small number of critical factors.

Methodology:

- Follow Steps 1-2 from Protocol 1: Focus on the critical factors identified during screening.

- Choose the Experimental Design: Select a Full Factorial design. For 3 factors at 2 levels, this requires 8 experimental runs (2^3) [10].

- Conduct and Analyze: Execute the randomized experiment and perform a full Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to obtain precise estimates for each factor's effect and the interaction effects.

Table 2: Main Effects and Interaction Effects Calculated from a Full Factorial Design This table summarizes the output of a statistical analysis, showing the magnitude and significance of each effect.

| Effect | Factor(s) | Estimate | p-value | Significance (at α=0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | A: pH | +0.45 | 0.005 | Significant |

| Main | B: Temperature | +0.30 | 0.032 | Significant |

| Main | C: Concentration | -0.05 | 0.651 | Not Significant |

| Interaction | A x B | +0.25 | 0.018 | Significant |

| Interaction | A x C | +0.08 | 0.452 | Not Significant |

| Interaction | B x C | -0.10 | 0.321 | Not Significant |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DoE-based Method Development

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, Design-Expert) | Used to generate the experimental design matrix, randomize the run order, and perform statistical analysis of the results to identify significant factors and interactions [10] [23]. |

| Quanterion Automated Reliability Toolkit (QuART) | Provides a dedicated DOE tool for easily designing tests (e.g., Fractional Factorial) and analyzing results, particularly useful for reliability and failure analysis [23]. |

| Controlled Reagents & Reference Standards | Ensures that the chemical inputs to the experiment are consistent and of known quality, reducing background noise and improving the detection of true factor effects. |

| Calibrated Instrumentation (e.g., HPLC, MS) | Provides the precise and accurate response data (e.g., retention time, peak area, mass accuracy) that is the foundation for all statistical analysis in the DoE. |

Risk Assessment Workflow Diagram

DoE Risk Assessment Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Selecting a DoE Design

Why is it important to use different types of experimental designs at different stages?

A single Design of Experiments (DoE) design type is often insufficient for an entire project. DoE is most effective when used sequentially, with each iteration moving you closer to the project goal [24]. Using the wrong design for a given stage can lead to wasted resources, failure to identify key variables, or an inability to find optimal conditions [10] [25].

Solution: Structure your DoE campaign into distinct stages, each with a specific goal and an appropriate design type [24]. The table below outlines the core stages and their purposes.

Table: Stages of a DoE Campaign and Their Purpose

| Stage | Primary Goal | Typical Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Screening | To identify the few critical factors from a large set of potential variables [25]. | Which of these 10 factors significantly affect the method's performance? |

| Mapping/Refinement | To iterate and refine the understanding of important factors and their interactions [24]. | How do the 3 key factors we identified interact with one another? |

| Optimization | To model the relationship between factors and responses to find a true optimum [10] [24]. | What are the precise settings for our 2 critical factors that will maximize yield and robustness? |

How do I choose a specific design for the screening stage?

The goal of screening is to efficiently investigate many factors to find the vital few. The main challenge is balancing comprehensiveness with experimental effort [25].

Solution: Select a screening design based on the number of factors you need to investigate and your resources. Fractional factorial and Plackett-Burman designs are the most common choices for this stage [10] [25].

Table: Comparison of Common Screening Designs

| Design Type | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | Screening a very small number of factors (e.g., <5) [10]. | Investigates all possible factor combinations and interactions [26]. | Number of runs grows exponentially with factors (2⁴=16 runs, 2⁵=32 runs, etc.) [10]. |

| Fractional Factorial | Screening a moderate number of factors (e.g., 5-8) [25]. | Drastically reduces run number by investigating a fraction of combinations [24]. | "Aliasing" occurs; some effects cannot be distinguished [24]. |

| Plackett-Burman | Screening a very large number of factors with very few runs [10]. | Highly efficient for estimating main effects only [10]. | Cannot estimate interactions between factors [10] [25]. |

Protocol: Executing a Fractional Factorial Screening Design

- Define the Problem: List all potential factors that could influence your response [26].

- Select Levels: Choose a realistic high and low level for each factor [27].

- Choose a Design: Use statistical software to select a fractional factorial design, noting its "resolution" which indicates the degree of aliasing [25].

- Randomize and Run: Conduct the experimental runs in a randomized order to minimize bias [27].

- Analyze: Use statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA, Pareto charts) to identify which factors have significant main effects on your response [27].

What should I do if my screening results are confusing or I suspect important interactions between factors?

This is a common issue when using highly fractional designs where interactions between factors are "aliased" or confounded with main effects, making it difficult to pinpoint the true cause of an effect [24].

Solution: If your initial screening design suggests several important factors or you suspect complex interactions, move to a mapping or refinement stage using a full factorial design [10] [28]. This will allow you to clearly estimate all main effects and two-factor interactions.

Protocol: Following Up with a Full Factorial Design

- Narrow Factors: Select only the significant factors from your screening study (typically 2 to 4) [24].

- Run Full Factorial: Conduct a full factorial design, testing every combination of the high and low levels for each selected factor.

- Analyze Interactions: Statistically analyze the results to quantify not only the main effect of each factor but also how factors interact (e.g., the effect of Temperature depends on the level of Pressure) [10] [27].

- Iterate: Use the insights from the interactions to refine factor levels and proceed to optimization.

How do I find the precise optimal conditions for my method?

Once you have identified and understood the critical factors, the next step is to find their optimal levels. This often involves modeling a curved (non-linear) response surface, which requires testing factors at more than two levels [10].

Solution: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) designs, which are specifically intended for building predictive models and finding optimal conditions [10] [24].

Table: Common RSM Designs for Optimization

| Design Type | Key Feature | Experimental Effort |

|---|---|---|

| Central Composite | Adds "axial points" to a factorial design to estimate curvature [10]. | Higher |

| Box-Behnken | Uses a spherical design that avoids corner points, often with fewer runs than Central Composite [24]. | Moderate |

Protocol: Optimization using a Central Composite Design

- Select Factors: Choose the 2 or 3 most critical factors from your earlier stages.

- Set Up Design: The design consists of three parts: a full factorial (or fractional factorial) points, axial points, and several center points [10].

- Conduct Experiments: Run all the experiments in the design in a randomized order.

- Model and Optimize: Fit a quadratic model to the data. Use the model's contour plots and optimization algorithms to find the factor settings that produce the best response [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials for DoE Implementation

| Item | Function in DoE |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Essential for generating design matrices, randomizing run orders, and analyzing complex results (e.g., ANOVA, interaction plots, response surfaces) [10] [26]. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Critical for validating your experimental system. A positive control gives a known expected response, while a negative control should show no response, confirming the assay is working [29] [30]. |

| Calibrated Equipment | Ensures that factor levels (like temperature, pressure, pH) are accurately applied and that response measurements are precise and reproducible [31]. |

| Standardized Reagents | Using reagents from consistent batches helps reduce unexplained variation ("noise") in your experiments, making it easier to detect the real "signal" from factor effects [31]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the single most common error in applying DoE?

One of the most common errors is failing to investigate a factor that turns out to be important, or not investigating a factor over a wide enough range to see its effect [31]. This can lead to a model that does not accurately represent the real process.

Do I always need to run all three stages (Screening, Mapping, Optimization)?

No, the progression is not always linear. You might find that a screening design with a few center points already points you to a good operating condition. Alternatively, if you have strong prior knowledge, you may start directly with a mapping or optimization design [24].

My optimal conditions from the model don't work as expected in the lab. What went wrong?

This can occur if the model is overfitted or if there is a problem with the model's lack-of-fit. Always run confirmation experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model. If the results don't match, it may be due to an important interaction or factor that was not included in the model, or the optimum may lie outside the region you investigated [31] [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Matrix and Sampling

Problem: My screening design shows no significant factors. What went wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: The range selected for your factors was too narrow and did not create a sufficiently strong signal over the background noise.

- Solution: Consult subject matter experts and historical data to set extreme but realistic high and low levels for each factor. The levels selected should be beyond what is currently in use but still operable within your system [32].

- Potential Cause 2: The measurement system for your response is not repeatable or is too noisy.

Problem: I cannot run all the required experimental runs due to material or time constraints.

- Potential Cause: A full factorial design was selected, which becomes prohibitively large as the number of factors increases.

- Solution: Use a fractional factorial design to investigate only a portion of the possible combinations. Alternatively, adopt a sequential approach. Start with a highly fractional screening design to identify the vital few factors, then perform a more detailed study on those factors in a subsequent experiment [32] [33].

Problem: My process drifts over time, and I'm concerned it will bias my results.

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled factors, such as ambient temperature or raw material batches, are changing over the course of the experiment.

- Solution: Implement "blocking" in your design. Restrict randomization by carrying out all trials with one setting of the uncontrolled factor (e.g., one material batch) before switching to the next. This isolates the variation due to the block from the variation due to your experimental factors [32].

Problem: I have a mixture experiment where the factors must sum to a constant (e.g., 100% of a formulation).

- Potential Cause: Standard factorial designs are not appropriate for mixture components.

- Solution: Use a specialized mixture design, such as a simplex, simplex lattice, or extreme vertex design. These designs are specifically created for experiments where the factors are proportions of a blend [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between a factor and a response?

- A: A factor is an input variable that you control and manipulate during the experiment (e.g., temperature, pressure, concentration of an excipient). A response is the output variable that you measure as the outcome (e.g., tensile strength, disintegration time, purity) [32] [34].

Q2: How many experimental runs do I need?

- A: The number of runs depends on the design you choose. For a full factorial design with 2 levels per factor, the number of runs is 2^n, where n is the number of factors. For example, a 3-factor full factorial requires 8 runs. Fractional factorial and other designs reduce this number. The key is to use a sequential approach rather than trying to answer all questions in one large experiment [32] [33].

Q3: Why is randomization important, and when should I not use it?

- A: Randomization refers to the random order in which experimental trials are performed. It helps eliminate the effects of unknown or uncontrolled variables, ensuring they do not bias your results. You should restrict randomization through "blocking" when a factor is impossible or too costly to randomize, such as when changing a raw material batch is a lengthy process [32].

Q4: Can I use DOE if I cannot control all the factors in my system?

- A: Yes. If you cannot control a factor but can measure it, you can treat it as a covariate in your analysis. For factors that vary unpredictably, use randomization and replication to minimize their impact. The key is to acknowledge these uncontrolled factors in your design rather than ignore them [35].

Quantitative Data and Calculations

The following table outlines the structure of a basic 2-factor, 2-level full factorial design matrix and shows how to calculate the main effect of each factor [32].

Table 1: 2-Factor Full Factorial Design Matrix and Effect Calculation

| Experiment # | Input A (Temperature) | Input B (Pressure) | Response (Bond Strength in lbs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 (100°C) | -1 (50 psi) | 21 |

| 2 | -1 (100°C) | +1 (100 psi) | 42 |

| 3 | +1 (200°C) | -1 (50 psi) | 51 |

| 4 | +1 (200°C) | +1 (100 psi) | 57 |

| Main Effect Calculation | Formula: (Average at High Level) - (Average at Low Level) | Result | |

| Effect of Temperature | (51 + 57)/2 - (21 + 42)/2 | 22.5 lbs | |

| Effect of Pressure | (42 + 57)/2 - (21 + 51)/2 | 13.5 lbs |

Experimental Protocol: Setting Up a Basic Design of Experiments

Objective: To systematically investigate the effect of two critical process parameters on a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) of a drug product.

Methodology:

- Define Inputs and Outputs: Acquire a full understanding of the inputs (factors) and outputs (responses) using a process flowchart. Consult with subject matter experts [32]. For a tablet formulation, factors could be the amount of disintegrant, diluent, and binder, while responses could be tensile strength and disintegration time [34].

- Establish a Reliable Measurement System: Determine the appropriate measure for the output. Ensure the measurement system (e.g., tensile strength tester, dissolution apparatus) is stable and repeatable. A variable measure is preferable to a pass/fail attribute [32].

- Create the Design Matrix: Generate a design matrix that shows all possible combinations of high (+1) and low (-1) levels for each input factor. For a 2-factor experiment, this will be a 2^2 full factorial design with 4 runs [32].

- Set Factor Levels: For each input, determine realistic high and low levels that you wish to investigate. These levels should be extreme enough to provoke a measurable change in the response but still within operable limits [32].

- Run Experiments Randomly: Execute the experimental runs in a randomized order to minimize the impact of uncontrolled variables [32].

- Record Data and Observations: Preserve all raw data and record everything that happens during the experiment. Do not keep only summary averages [33].

- Analyze Data and Calculate Effects: Calculate the main effect of each factor as shown in Table 1. Use statistical software to perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine the statistical significance (p-value) of each factor and their interactions [34].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Tablet Formulation DoE

| Material / Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Disintegrant (e.g., Ac-Di-Sol) | Promotes the breakup of a tablet after administration to release the active pharmaceutical ingredient [34]. | A mixture design investigating the effect of Ac-Di-Sol (1-5%) on disintegration time [34]. |

| Diluent/Filler (e.g., Pearlitol SD 200) | Adds bulk to the formulation to make the tablet a practical size for manufacturing and handling [34]. | A component in a mixture design where its proportion is varied against a binder and disintegrant [34]. |

| Binder (e.g., Avicel PH102) | Imparts cohesiveness to the powder formulation, ensuring the tablet remains intact after compression [34]. | A study showed that increasing Avicel PH102 % resulted in a gain of tensile strength and solid fraction of the tablet [34]. |

| Instrumented Tablet Press (e.g., STYL'One Nano) | Used to compress powder blends into tablets under controlled parameters (e.g., force, pressure) for each experimental run [34]. | Used to produce tablets for 18 randomized formulation experiments in a mixture design study [34]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Why is randomization a critical step in executing a DoE, and what are the consequences of skipping it? Randomization is fundamental because it minimizes the influence of uncontrolled, lurking variables (also known as "nuisance factors") that could bias your results [10]. By performing experimental runs in a random order, you help ensure that these unknown effects are distributed randomly across the entire experiment rather than systematically skewing the data for a particular factor level. Skipping randomization can lead to confounded results, where the effect of a factor you are testing is indistinguishable from the effect of an external, unrecorded variable, such as ambient temperature fluctuations or reagent degradation over time [10].

Q2: Our test results are inconsistent, even between identical experimental runs. What could be the cause? This often points to an inadequate error control plan [11]. To troubleshoot, investigate the following:

- Unrecorded Variables: Ensure you are measuring and recording uncontrolled factors during the study, such as ambient temperature, analyst name, equipment ID, reagent transfer times, or hold times [11]. These covariates can explain unexpected variation.

- Assembly and Procedure Errors: In a controlled experiment, hyper-vigilance during assembly is critical [36]. A component kitting error or a slight deviation from the sample preparation method can cause significant variation. Be present during the assembly process to prevent these errors [36].

- Insufficient Replication: Precision (repeatability and intermediate precision) requires replicates to quantify variation [11]. If you only have single runs for each combination, you cannot separate the true experimental error from the effect of the factors.

Q3: How many experimental units should we test to have confidence in our results?

The number of units is tied to the failure rate you are trying to detect and must be sufficient for a statistically significant result [36]. A practical rule of thumb is that to validate a solution for an issue with a failure rate of p, you should test at least n = 3/p units and observe zero failures. For example, to validate an improvement for a problem with a 10% failure rate, you should plan to test 30 units with zero failures [36].

Q4: What is the difference between a replicate and a duplicate, and when should I use each? This distinction is crucial for a correct error control plan [11]:

- Replicates are complete, independent repeats of the entire analytical method, including sample preparation. They are used to estimate the total method variation.

- Duplicates are multiple measurements or injections from a single sample preparation. They are used to estimate the precision of the instrument, chemistry, or plate, independent of sample preparation errors. Use replicates to understand the overall robustness of your method and duplicates to isolate sources of variation within the method workflow [11].

Q5: After running the DoE, how should we present the findings to support a decision? Clarity is key. You should be able to justify your recommended decision on a single slide, using the most critical raw data or model outputs [36]. This forces a focus on the most actionable results and builds a strong technical reputation. Avoid slides cluttered with every statistical detail; instead, present a clear, defensible conclusion from the data [36].

Experimental Workflow for DoE Execution

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points for executing a DoE with proper error control and randomization.

DoE Execution and Error Control Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions in the context of analytical method development and validation using DoE.

| Item | Function in DoE |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized standards are crucial for determining method bias and accuracy. Their stability is a key consideration [11]. |

| Chemistries & Reagents | Factors like pH of a mobile phase or buffer concentration are often critical parameters tested in a DoE to understand their effect on responses like resolution [10]. |

| Sample Matrix | The solution matrix in which the analyte is measured must be representative, as the method is characterized and validated for a specific design space of concentrations and matrices [11]. |

| Instrumentation/Equipment | Different instruments, sensors, or equipment (e.g., columns) can be factors in a DoE to assess intermediate precision and ensure method robustness across labs [11]. |

In the field of pharmaceutical method development, Fractional Factorial Designs (FFDs) serve as a powerful statistical tool within the Design of Experiments (DoE) framework, enabling researchers to efficiently screen multiple factors with a minimal number of experimental runs. A FFD is a subset, or fraction, of a full factorial design, where only a carefully selected portion of the possible factor-level combinations is tested [37] [38]. This approach is grounded in the sparsity-of-effects principle, which posits that most process and product variations are driven by a relatively small number of main effects and low-order interactions, while higher-order interactions are often negligible [37]. For researchers developing pellet dosage forms, where numerous formulation and process variables can influence critical quality attributes (CQAs), FFDs provide an economical and time-efficient strategy for initial experimentation and troubleshooting. By strategically confounding (aliasing) higher-order interactions with main effects or other lower-order interactions, FFDs allow for the identification of vital factors from a large pool of candidates without investigating the entire experimental space, which would be prohibitively resource-intensive [39] [40]. This case study explores the practical application of FFDs to optimize a pellet formulation, providing a structured troubleshooting guide for scientists and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Framework: Key FFD Concepts for Researchers

Basic Principles and Notation

FFDs are typically denoted as lk-p designs, where l represents the number of levels for each factor, k is the total number of factors being investigated, and p determines the size of the fraction used [37]. The most common in pharmaceutical screening are two-level designs (high and low values for each factor), expressed as 2k-p. For example, a 25-2 design studies five factors in just 2(5-2) = 8 runs, which is a quarter of the 32 runs required for a full factorial design [37]. The selection of which specific runs to perform is controlled by generators—relationships that determine which effects are intentionally confounded to reduce the number of experiments [37].

Understanding Aliasing and Resolution

The reduction in experimental runs comes with a trade-off: aliasing (or confounding). Aliasing occurs when the design does not allow for the separate estimation of two or more effects; their impacts on the response are intertwined [37] [38]. The Resolution of a FFD, denoted by Roman numerals (III, IV, V, etc.), characterizes the aliasing pattern and indicates what level of effects can be clearly estimated [37] [38]:

- Resolution III: Main effects are not confounded with other main effects but are confounded with two-factor interactions. Useful for initial screening of a large number of factors.

- Resolution IV: Main effects are not confounded with each other or with two-factor interactions, but two-factor interactions are confounded with one another.

- Resolution V: Main effects and two-factor interactions are not confounded with each other, though two-factor interactions may be confounded with three-factor interactions.

For most pellet formulation development projects, a Resolution IV or V design is recommended to ensure that main effects and critical two-factor interactions can be reliably identified [38].

Case Study: Developing Rapidly Dissolving Effervescent Pellets

Project Objective and Experimental Design

A study was conducted to develop novel, fast-disintegrating effervescent pellets using a direct pelletization technique in a single-step process [41]. Aligned with the Quality by Design (QbD) regulatory framework, the researchers employed a statistical experimental design to correlate significant formulation and process variables with the CQAs of the product, such as sphericity, size, and size distribution [41]. The initial phase utilized a screening fractional factorial design, which was later augmented to a full factorial design. This approach established a roadmap for the rational selection of composition and process parameters. The final optimization phase leveraged response surface methodology, which enabled the construction of mathematical models linking input variables to the CQAs under investigation [41]. The application of the desirability function led to the identification of the optimum formulation and process settings for producing pellets with a narrow size distribution and a geometric mean diameter of approximately 800 μm [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pellet Formulation

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Pellet Development |

|---|---|---|

| Pelletization Aids | Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), κ-Carrageenan [42] | Provides cohesiveness and binds the granule core; critical for achieving spherical shape during extrusion/spheronization. |

| Effervescent Agents | Not specified in detail [41] | Facilitates rapid disintegration of the pellets upon contact with aqueous media. |

| Surfactants/Emulsifiers | Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), Sorbitan mono-oleate (Span 80) [43] | Key components in self-emulsifying systems for enhancing drug dissolution of poorly soluble APIs. |

| Oils/Lipids | Soybean oil, Mono- and diglycerides (Imwitor 742) [43] | Forms the lipid core in self-emulsifying pellet formulations. |

| Solvents | Water (Purified) [43] | Critical wetting agent during the wet massing step; essential for successful extrusion and spheronization. |

| Co-surfactants | Transcutol P [44] | Improves drug solubility in the lipid phase and aids surfactant in stabilizing oil dispersions. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following workflow diagrams the general sequence of experiments in a FFD-based pellet development project, as exemplified by the case study.

Diagram 1: FFD-Based Pellet Development Workflow

Detailed Protocol for Initial FFD Screening:

- Define Objective and CQAs: Clearly state the goal (e.g., "develop rapidly dissolving pellets with a target size of 800 μm"). Define measurable CQAs, such as sphericity (aspect ratio), particle size distribution, disintegration time, and drug dissolution profile [41] [42].

- Identify Factors and Levels: Brainstorm and select