Boosting MS Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Ionization Efficiency with Emitter Array Technology

This article provides a detailed exploration of electrospray ionization (ESI) emitter arrays, a transformative technology for enhancing sensitivity in mass spectrometry.

Boosting MS Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Ionization Efficiency with Emitter Array Technology

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of electrospray ionization (ESI) emitter arrays, a transformative technology for enhancing sensitivity in mass spectrometry. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of ionization and transmission efficiency that underpin the technology's success. The content delves into practical methodologies for fabricating and implementing emitter arrays, including advanced configurations like the subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface. A dedicated section addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as managing inter-emitter electric field interference. Finally, we present a rigorous validation and comparative analysis, demonstrating how emitter arrays can yield over an order of magnitude sensitivity improvement compared to conventional single-emitter sources, providing a clear path to more powerful bioanalytical assays.

The Fundamentals of Ionization Efficiency: Why Emitter Arrays Are a Game Changer for MS Sensitivity

Defining Ionization and Ion Transmission Efficiency in ESI-MS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are ionization efficiency and ion transmission efficiency, and why are they critical for ESI-MS sensitivity? Ionization efficiency refers to the effectiveness of producing gas-phase ions from analyte molecules in solution within the electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Ion transmission efficiency is the ability to transfer the generated ions from the atmospheric or subambient pressure region into the high vacuum of the mass analyzer [1]. Collectively, they determine the overall sensitivity of an LC-MS method; improvements in these parameters directly enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and lower detection limits [1] [2].

How do multi-emitter arrays fundamentally improve ESI-MS performance? Emitter arrays improve performance by addressing flow rate mismatches and increasing total current. They split a single, higher liquid flow (e.g., from LC) into multiple nano-flow electrosprays, where ionization is most efficient [2]. Furthermore, the total electrospray current generated at a given flow rate is proportional to the square root of the number of emitters, creating a "brighter" ion source [2]. When coupled with specialized inlets, this approach can sample a larger portion of the ion plume, significantly boosting sensitivity [3].

What are the common signs of poor ion transmission in my spectra? Common indicators include:

- A consistently low signal-to-noise ratio across all analytes despite sample concentration.

- Unstable or fluctuating total ion current (TIC).

- Inefficient transmission can also contribute to adduct formation (e.g., [M+Na]+) and spectral noise if declustering parameters are not optimally set [4] [5] [1].

What is the role of emitter geometry in ionization efficiency? The geometry of the emitter tip directly influences the stability of the Taylor cone and the size of the initial charged droplets. Emitters with smaller outer diameters produce smaller droplets, which desolvate more efficiently and require fewer fission events to liberate gas-phase ions, thereby enhancing ionization efficiency [3] [6]. Novel geometries, like circular arrays, are designed to ensure all emitters experience a uniform electric field, preventing the outer emitters from dominating the spray [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Low Ionization Efficiency

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Investigation | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low signal for all analytes | Suboptimal source parameters: Incorrect capillary voltage, gas flows, or temperature. | Systematically optimize voltage, nebulizer, and desolvation gas settings. | [4] [5] [1] |

| Inappropriate solvent composition: High aqueous content or high surface tension solvents. | Add 1-2% organic solvent (e.g., methanol) to aqueous eluents; use volatile buffers. | [4] [5] | |

| Non-volatile salts or buffers in the mobile phase or sample. | Use MS-compatible buffers (e.g., ammonium acetate); employ desalting protocols. | [1] [7] [6] | |

| Unstable spray current, fluctuating signal | Electrical interference in multi-emitter arrays. | Use circular emitter array geometry to ensure uniform electric field across all emitters. | [3] |

| Clogged or contaminated emitter. | Inspect and clean the emitter; improve sample cleanup. | [7] | |

| Excessive adduct formation ([M+Na]+, [M+K]+) | Metal ion contamination from glass vials, solvents, or samples. | Use plastic vials, high-purity solvents, and rigorous sample preparation (SPE, LLE). | [4] [5] |

Diagnosing Poor Ion Transmission

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Investigation | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low signal despite strong spray | Ion plume sampling issue: Sprayer position is too far from or too close to the MS inlet. | Adjust the sprayer position relative to the sampling cone. | [4] [5] [1] |

| Conductance limitation at the MS inlet. | Consider interfaces with multi-capillary inlets or a Subambient Pressure Ionization (SPIN) source. | [3] [2] | |

| Signal loss for labile compounds | Excessive declustering/cone voltage causing fragmentation. | Reduce the cone (orifice) voltage. | [4] [5] |

| Desolvation temperature too high, degrading the analyte. | Lower the desolvation gas temperature. | [1] |

Key Experiments & Methodologies

Experiment: Sensitivity Comparison of Single vs. Multi-Emitter Arrays

Objective: To quantitatively demonstrate the sensitivity gain achieved by using a multi-emitter array coupled with a specialized ion inlet compared to a standard single emitter configuration [2].

Protocol:

- Emitter Fabrication: Create a circular multi-emitter array [3]. Fabricate arrays with a different number of emitters (e.g., 4, 6, 10) using fused silica capillaries. Use a PEEK disk spacer to arrange the emitters in a circular pattern and seal them with epoxy. Chemically etch the capillary ends in hydrofluoric acid (HF) while pumping water through them to create externally tapered emitters of uniform length [2].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare an equimolar mixture (e.g., 1 µM each) of standard peptides (e.g., angiotensin I, bradykinin, neurotensin) in a standard ESI solvent (e.g., 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile) [2].

- MS Analysis: Interface the emitter arrays with a mass spectrometer (e.g., Time-of-Flight). Compare the following configurations:

- Configuration A: Standard single ESI emitter with a heated capillary inlet at atmospheric pressure.

- Configuration B: Single emitter with a Subambient Pressure Ionization (SPIN) source.

- Configuration C: Multi-emitter array (e.g., 4, 6, 10 emitters) with the SPIN source [2].

- Data Analysis: Measure and compare the signal intensity (peak height) or the total ion current for a specific peptide across all configurations.

Expected Outcome: The sensitivity (signal intensity) will increase with the number of emitters in the array. The multi-emitter/SPIN configuration (C) is expected to show over an order of magnitude improvement compared to the standard single emitter configuration (A) [2].

Experiment: Mitigating Salt Suppression with Theta Emitters

Objective: To enable mass analysis of proteins and protein complexes directly from solutions containing biological buffers and non-volatile salts at physiologically relevant concentrations [6].

Protocol:

- Emitter Preparation: Pull borosilicate glass capillaries (1.5 mm o.d.) using a micropipette puller to create theta emitters with an internal diameter of ~1.4 µm. These emitters have a septum dividing the capillary into two channels [6].

- Sample Loading:

- Channel 1: Load the protein sample dissolved in a biological buffer (e.g., PBS) with non-volatile salts.

- Channel 2: Load a solution of 200 mM ammonium acetate (AmAc) supplemented with an additive like sodium bromide (NaBr) or sodium iodide (NaI) [6].

- Mass Spectrometry:

- Insert dual platinum wires into the open ends of the theta emitter, each making contact with one channel.

- Apply a high voltage (0.8–2.0 kV) to initiate electrospray.

- Place the emitter orthogonal to the MS orifice, 1–2 mm from the curtain plate.

- Use gas-phase collisional activation methods (e.g., beam-type collision-induced dissociation and dipolar direct current) in the mass spectrometer to remove salt adducts after ionization [6].

- Data Analysis: Compare the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) and spectral quality (e.g., reduced adduction) to experiments performed with AmAc alone or with desalted samples.

Expected Outcome: The addition of anions with low proton affinity (Br-, I-) in the second channel significantly reduces ionization suppression and chemical noise, leading to higher S/N ratios and reproducible mass spectra for proteins in high-salt solutions [6].

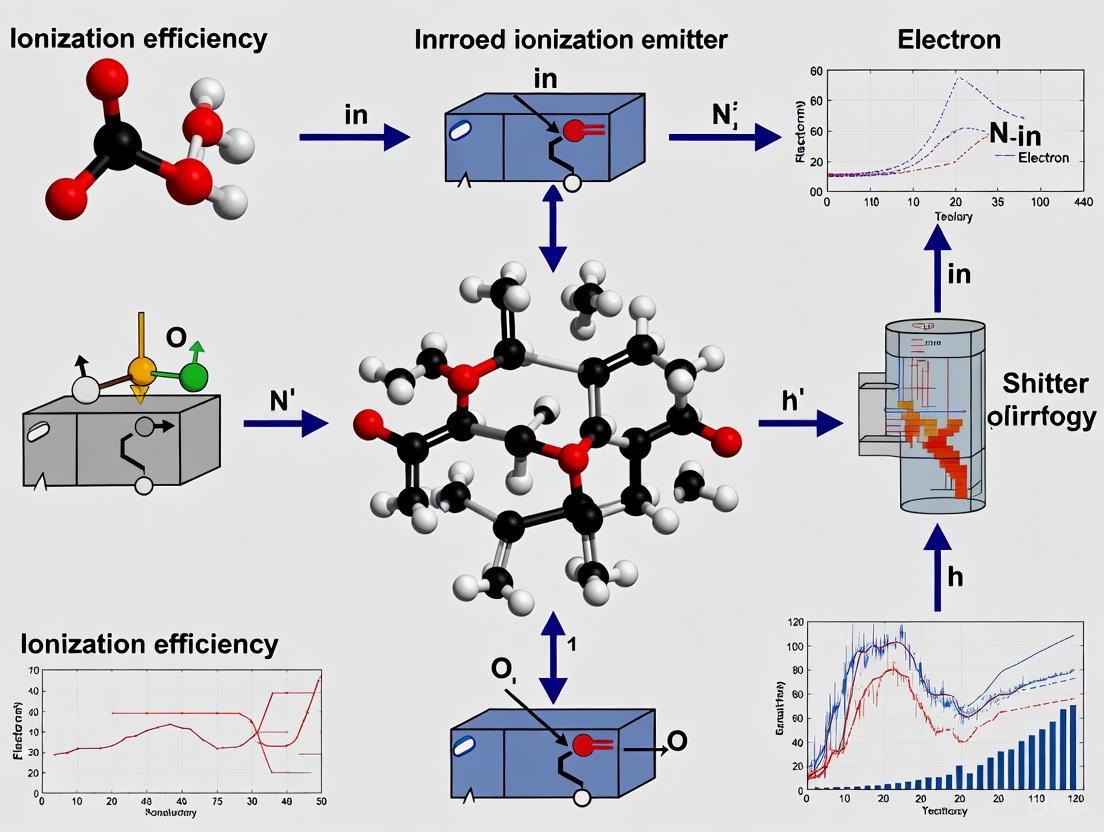

Diagrams

Multi-Emitter Array Fabrication

Ionization & Transmission Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries (e.g., 150 µm o.d., 10 µm i.d.) | The core material for fabricating chemically etched nano-ESI emitters and emitter arrays. | Used to create emitters with uniform geometry and taper for stable electrospray [3] [2]. |

| Borosilicate Theta Capillaries (1.5 mm o.d.) | Used to pull dual-channel theta emitters for analyzing samples in non-volatile salts. | Enables mixing of sample with additive solutions (e.g., AmAc + NaBr) immediately prior to electrospray [6]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF), 49% | For chemical etching of fused silica capillaries to create sharp, tapered emitters. | Extreme hazard. Must be used in a fume hood with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Water is pumped through the capillary during etching to protect the inner wall [3] [2]. |

| Nanostrip 2X | A chemical solution used to remove the polyimide coating from fused silica capillaries prior to etching. | Handle with care in a ventilated hood as it is corrosive [3] [2]. |

| Ammonium Acetate (AmAc) | A volatile salt used as an MS-compatible buffer to replace non-volatile biological buffers. | Can be supplemented with sodium bromide or iodide to mitigate ion suppression in high-salt samples [6]. |

| Sodium Bromide (NaBr) / Sodium Iodide (NaI) | Additives with anions of low proton affinity. Help reduce sodium adduction and chemical noise. | Used in one channel of a theta emitter to improve S/N for proteins in biological buffers [6]. |

In conventional Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS), a significant fraction of analyte ions never reaches the mass spectrometer detector. This ion loss occurs at the critical interface where ions transition from atmospheric pressure to the instrument's first vacuum stage. The fundamental issue is a mismatch between the size of the electrospray plume and the limited sampling capacity of the inlet orifice; the ESI plume covers a larger geometric area than the inlet capillary can effectively sample, resulting in only a fraction of the generated current being transmitted into the mass spectrometer [2]. This technical brief from our support center explores the mechanisms behind this bottleneck and presents advanced emitter array technology as the primary solution, providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers seeking to maximize their instrument sensitivity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ESI-MS Interface Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spray Stability | Unstable signal, rapid fluctuations in intensity. | Electrical discharge (corona), non-optimal sprayer position, or rim emission [5]. | Optimize sprayer voltage and capillary position relative to the sampling cone. Use lower, more aqueous content solvents [5]. |

| Ion Transmission | Lower-than-expected sensitivity for all analytes. | Major ion losses at the atmospheric pressure interface; spray plume larger than the inlet orifice [2]. | Consider a source upgrade to a multi-emitter or SPIN (Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray) source to drastically improve transmission [2]. |

| Ion Suppression | Reduced analyte signal in complex matrices (e.g., plasma, tissue); inaccurate quantification. | Competition for charge and space on ESI droplets by co-eluting matrix components with high concentration, mass, or basicity [8]. | Improve chromatographic separation, enhance sample cleanup, or switch to APCI if applicable. Using emitter arrays can also reduce suppression [8] [3]. |

| Adduct Formation | High abundance of [M+Na]+ or [M+K]+ ions instead of [M+H]+. | Presence of metal ion contaminants from glass vials, solvents, or sample matrix [5]. | Use plastic vials instead of glass, use high-purity solvents and additives, and ensure thorough flushing of the system between runs [5]. |

| Spray Needle Clogging | Loss of spray and signal. | Buildup of non-volatile components from the sample or the use of non-volatile buffers in the mobile phase [7]. | Improve sample preparation to remove non-volatiles. Avoid non-volatile buffers. For systems with a divert valve, a make-up flow of clean solvent can prevent deposits [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of ion losses in a standard atmospheric pressure ESI source?

The primary cause is a geometric and conductance mismatch. The electrospray plume is generated over an area that is larger than the mass spectrometer's inlet capillary can effectively sample. Consequently, a significant portion of the generated ions is lost in the atmospheric pressure region before ever entering the vacuum system. Research indicates that these are the major ion losses of conventional ESI-MS interfaces [2].

Q2: How do multi-emitter arrays specifically address the issue of ion losses?

Emitter arrays tackle the problem from two angles:

- Flow Rate Splitting: They split a higher liquid flow rate (e.g., from an LC system) into multiple nano-flow-rate electrosprays. ESI is inherently more efficient at lower flow rates, producing smaller initial charged droplets that lead to more efficient ion production [2] [3].

- Increased Total Current: The total electrospray current generated at a given flow rate is proportional to the square root of the number of emitters, creating a "brighter" ion source [2]. When coupled with an interface designed to handle this larger current, such as a multi-capillary inlet or a SPIN source, the overall ion transmission into the mass spectrometer is dramatically increased.

Q3: We observe significant ion suppression in our biological samples. Can emitter arrays help?

Yes. Ion suppression occurs when co-eluting matrix components compete with the analyte for charge or for a position on the surface of the electrospray droplet [8]. By splitting the flow into multiple nano-electrosprays, emitter arrays reduce the number of molecules per droplet, which can mitigate this competition effect. Studies have demonstrated that multi-emitters can reduce ion suppression effects and improve quantitation [3].

Q4: What is the SPIN source and how does it differ from conventional interfaces?

The SPIN (Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray) source is a revolutionary design that eliminates the atmospheric pressure interface altogether. It places the ESI emitter directly inside the first reduced-pressure region (10-30 Torr) of the mass spectrometer, adjacent to a low-capacitance ion funnel [2] [9]. This configuration allows the entirety of the spray plume to be sampled, essentially eliminating losses associated with transfer from ambient pressure. When combined with multi-emitter arrays, the SPIN source has been shown to improve MS sensitivity by over an order of magnitude [2].

Experimental Protocols & Technical Data

Quantitative Comparison of ESI Source Configurations

The following table summarizes experimental data comparing the sensitivity of different source configurations, obtained from the analysis of an equimolar solution of 9 peptides [2].

| ESI Source Configuration | Operating Pressure | Relative MS Sensitivity | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Single Emitter / Heated Capillary | Atmospheric Pressure | 1.0 (Baseline) | Limited sampling of the ES plume by a single inlet. |

| Single Emitter / SPIN | ~10-30 Torr | Significantly Higher | Eliminates inlet capillary losses; entire plume sampled by ion funnel. |

| Multi-Emitter / SPIN | ~10-30 Torr | >10x Higher than baseline | Combines efficient nano-ESI from multiple jets with complete plume sampling. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Key materials and reagents essential for fabricating and operating high-sensitivity emitter arrays based on published methodologies [2] [3].

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries (e.g., 150 μm o.d., 10 μm i.d.) | Fabrication of the nano-electrospray emitters. |

| Polyimide Removal Solution (e.g., Nanostrip 2X) | To remove the polyimide coating from capillary ends before etching. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF), 49% | Chemical etching of capillaries to create tapered emitter tips. |

| Epoxy (e.g., HP 250) | To seal and fix capillaries in the array assembly. |

| PEEK Sleeves, Ferrules, and Tubing | For creating the fluidic and structural body of the emitter array. |

| ESI Solvent (0.1% Formic Acid in 10% Acetonitrile) | A common volatile solvent with additive to promote ionization. |

Protocol: Fabrication of a Multi-Emitter Array with Individualized Sheath Gas

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a circular multi-emitter array, which provides uniform electric field distribution for stable spray [2] [3].

- Assembly of Sheath Gas Capillary Preform: Insert larger fused silica capillaries (~360 μm o.d., ~10 cm long) through a PEEK sleeve. Arrange their distal ends into a circular pattern using a drilled PEEK disk spacer and fix them in place with epoxy.

- Integration with Fluidic Line: Insert the preform into a T-junction and secure it. Connect a piece of PEEK tubing to the opposite end for sample introduction.

- Threading and Sealing Emitter Capillaries: Thread smaller emitter capillaries (150 μm o.d., 10 μm i.d.) through the preform so they protrude 1-2 cm. Seal them with epoxy at the second seal to restrict liquid flow to the emitter capillaries only.

- Polyimide Removal and Etching: Remove the polyimide coating from the emitter tips using a heated Nanostrip solution. Subsequently, chemically etch the exposed fused silica in a hydrofluoric acid bath to create externally tapered emitters of uniform length. Note: Pumping water through the emitters during etching prevents inner wall etching. HF is extremely hazardous and must be handled in a ventilated hood with appropriate personal protective equipment.

Technical Schematics & Workflows

Conventional ESI vs. SPIN Source Ion Transmission

Decision Workflow for Improving Ion Transmission

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean for an ion source to be "brighter"?

A "brighter" ion source is one that can produce a greater total ion current [10]. In the context of emitter arrays, this is achieved by operating multiple nanoelectrospray (nanoESI) emitters in parallel. This parallel operation generates a significantly higher number of charged droplets and, subsequently, a larger population of gas phase analyte ions compared to a single emitter source, thereby increasing the overall signal available to the mass spectrometer [10].

2. What is the primary advantage of using an emitter array with a SPIN-MS interface?

The primary advantage is the synergistic improvement in both ionization efficiency and ion transmission efficiency [10]. While the emitter array acts as a brighter ion source by producing more ions, the Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface is designed to more effectively capture and transmit these ions into the mass spectrometer's vacuum. Research indicates that the SPIN-MS interface configuration with an emitter array exhibits greater overall ion utilization efficiency than conventional inlet capillary-based interfaces [10].

3. Why are improvements in ion source brightness alone not sufficient for maximum sensitivity gains?

Gains from brighter ion sources are minimal if the increased ion current cannot be effectively transmitted through the ESI-MS interface [10]. Significant ion loss can occur at the sampling inlet, within the interface capillary, or on other surfaces. Therefore, a bright source must be paired with an efficient interface design, like the SPIN interface, to realize the full sensitivity potential [10].

4. How is the performance of an ESI-MS interface configuration quantitatively evaluated?

Performance is evaluated by measuring the ion utilization efficiency. This is determined by correlating the total transmitted gas phase ion current (measured with a charge collector like an ion funnel) with the observed analyte ion intensity in the mass spectrum [10]. This method provides a more effective metric than measuring electrical current alone, as it specifically reflects the efficiency of transmitting actual analyte ions to the detector [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Transmitted Ion Current Despite Using an Emitter Array

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Emitter Positioning | Verify the emitter's protrusion distance and alignment relative to the counter-electrode or ion funnel inlet. | For the SPIN interface, position the emitter ~2 mm from the cylindrical outlet and ~1 mm from the first ion funnel electrode, ensuring it is on the central axis [10]. |

| Insufficient Desolvation | Check for broad, unresolved peaks in the mass spectrum indicating residual solvent clusters. | For SPIN-MS, ensure the heated CO₂ desolvation gas is active and its temperature is adequately set (e.g., ~160 °C) [10]. |

| Electrical Breakdown or Unstable Spray | Inspect for electrical arcing, especially in subambient pressure conditions. | Utilize the coaxial sheath gas provision around each emitter in the array to stabilize the electrospray and prevent electrical breakdown [10]. |

Issue: High Background Noise or Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Contaminated Emitter or Sample | Run a blank solvent to see if the noise persists. | Ensure thorough flushing of the emitter array with clean solvent between samples. Filter all samples and solvents. |

| Ion Funnel RF Settings | Systematically adjust the RF voltage on the high-pressure ion funnel while monitoring total signal. | Optimize the RF voltage. Studies show signal is maximized at sufficiently high RF amplitudes (e.g., ~300 Vpp) to focus desolvated ions effectively [10]. |

| Source of Charged Residuals | The transmitted current may contain charged solvent clusters. | The ion funnel RF helps separate fully desolvated ions from clusters. Ensuring proper desolvation is key to converting clusters into clean analyte ions [10]. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Interface Performance Comparison

The following data summarizes key findings from a systematic study comparing different ESI-MS interface configurations [10].

Table 1: Transmitted Electric Current and Ion Utilization Efficiency for Different Configurations

| Interface Configuration | Ion Source | Approx. Transmitted Electric Current | Ion Utilization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Capillary Inlet | Single Emitter | Lower | Lower |

| Multi-Capillary Inlet | Single Emitter | Moderate | Moderate |

| SPIN Interface | Single Emitter | Higher | Higher |

| SPIN Interface | Emitter Array | Highest | Highest |

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Evaluations

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|

| Peptides (e.g., Angiotensin I, Bradykinin) | Model analytes for testing interface performance with biologically relevant molecules [10]. |

| 0.1% Formic Acid (FA) in 10% Acetonitrile/Water | Standard ESI solvent for promoting positive ion mode ionization [10]. |

| Etched Fused Silica Emitters (O.D. 150 µm, I.D. 10 µm) | NanoESI emitters for stable, low-flow-rate electrospray [10]. |

| Emitter Array with Coaxial Sheath Gas | A multi-emitter device for producing higher total ion current ("brighter" source) [10]. |

| Tandem Ion Funnel Interface | Device for efficiently focusing and transmitting ions through pressure gradients with high efficiency [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Interface Efficiency Evaluation

This protocol is adapted from methods used to generate the comparative data in the associated research [10].

Objective: To evaluate the ion utilization efficiency of an ESI-MS interface configuration by correlating transmitted gas phase ion current with observed mass spectral intensity.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a 1 µM solution of each model peptide (e.g., angiotensin I) in 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile/water.

- Interface Setup: Configure the mass spectrometer with the interface to be tested (e.g., single capillary inlet or SPIN interface).

- Emitter Installation & Positioning: Connect a chemically etched fused silica emitter to a syringe pump via a stainless steel union. Apply the ESI voltage to the union. Precisely position the emitter:

- Infuse Sample: Infuse the peptide solution at a constant nanoflow rate (e.g., 50-200 nL/min).

- Measure Transmitted Electric Current: Use the low-pressure ion funnel as a charge collector. Connect its DC voltage lines to a picoammeter. Record the average electric current from at least 100 consecutive measurements [10].

- Acquire Mass Spectrum: In parallel, acquire a mass spectrum in positive ion mode over a relevant m/z range (e.g., 200-1000). Sum the spectra over 1 minute.

- Data Correlation: Calculate the total ion current (TIC) or extracted ion current (EIC) for a specific analyte from the mass spectrum. Correlate this value with the transmitted electric current measured in Step 5 to determine the ion utilization efficiency for the configuration.

- Comparison: Repeat Steps 2-7 for all interface configurations (e.g., single capillary, multi-capillary, SPIN) and ion sources (single emitter, emitter array).

Technical Visualizations

Diagram 1: Ion Source and Interface Workflow

Diagram 2: SPIN vs. Capillary Interface Mechanism

Flow splitting using multi-emitter arrays is a technique that decouples the flow rate requirements of Liquid Chromatography (LC) from the optimal flow rates for nanoElectrospray Ionization (nanoESI). By dividing a single LC effluent post-column into multiple parallel nanoESI emitters, this approach extends the enhanced ionization efficiency and sensitivity characteristic of low-flow nanoESI to higher-flow-rate LC separations [11] [3]. The key challenge addressed is that while ESI becomes increasingly efficient at low nL/min flow rates, LC separations often use much higher flow rates to maintain sample loading capacity and system robustness. Multi-emitter arrays resolve this compromise [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Capillary-Based Multi-NanoESI Emitters

This protocol details the construction of a 19-emitter array from fused silica capillaries [11].

Materials Required:

- Fused silica capillaries (20 µm i.d. / 150 µm o.d.)

- Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) disks (0.5-mm-thick, 5-mm-diameter)

- Devcon HP250 epoxy

- Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) - Note: Extremely hazardous; use ventilated hood and protective equipment.

- Nanostrip 2X (for polyimide coating removal)

- Tubing sleeve (750-µm-i.d.)

- PEEK nut and ferrule (e.g., Upchurch Scientific F-195)

Methodology:

- Disk Machining: Machine two identical PEEK disks with a pattern of 19 holes (200-µm-diameter) arranged in a circular or linear pattern with 500 µm center-to-center spacing [3].

- Capillary Assembly: Thread 4-6 cm long fused silica capillaries through the aligned holes in both disks. The disks should be separated by 3-4 mm to ensure the capillaries run parallel.

- Fluidic Connection: Insert the proximal ends of the capillaries into a tubing sleeve, seal with epoxy, and cure at 80°C for 2 hours. Attach a PEEK nut and ferrule for fluidic connection to the LC system.

- Polyimide Removal: Pump water through the capillaries at 100 nL/min per capillary and immerse the distal ends in a warm (90°C) Nanostrip 2X bath for approximately 20 minutes to remove the polyimide coating.

- Chemical Etching: Etch the capillary ends in 49% HF to form externally tapered emitters of uniform length, enabling stable nanoelectrospray [3].

Protocol 2: Coupling Multi-Emitter Arrays with LC-MS for Complex Peptide Analysis

This protocol describes the application of a 19-emitter array for the LC-MS analysis of a tryptic digest of human plasma [11].

Materials Required:

- Capillary LC system (operating at ~2 µL/min)

- Tandem ion funnel mass spectrometer interface

- Multi-capillary heated inlet (e.g., 9-capillary inlet, 4.4 cm long, 490 µm i.d.)

- Mobile Phase A: H₂O/Acetic Acid/Trifluoroacetic Acid (100:0.2:0.5; v/v/v)

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile/H₂O/Trifluoroacetic Acid (90:10:0.1; v/v/v)

- Tryptic digest sample (e.g., spiked human plasma)

Methodology:

- LC Separation: Connect the LC column to the multi-emitter array using a standard stainless steel union. Apply a gradient elution from Mobile Phase A to B at a total flow rate of 2 µL/min.

- Post-Column Flow Splitting: The LC effluent is passively divided post-column among the 19 emitters of the array, reducing the flow to approximately 105 nL/min per emitter, which is within the optimal nanoESI regime.

- MS Interface Configuration: Position the multi-emitter array 1-1.5 mm from the custom multi-capillary inlet of the mass spectrometer. The multi-capillary inlet is heated to 125°C and is coupled to a tandem ion funnel interface to efficiently handle the increased gas and ion load.

- Electrospray Initiation: Apply a 2 kV potential to the solution via the stainless steel union connecting the LC column to the emitter array.

- Data Acquisition: Perform MS analysis. The system demonstrated an average 11-fold signal increase for peptides from spiked proteins and a ~7-fold increase in LC peak signal-to-noise ratio compared to a single emitter configuration [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My multi-emitter array shows inconsistent spray or failed ignition across different emitters. What could be wrong?

This is typically caused by electric field inhomogeneity (shielding) within the array [3].

- Problem: In linear arrays, outer emitters experience a higher electric field than interior emitters for the same applied voltage, leading to inconsistent spray initiation and performance.

- Solution:

- Utilize a Circular Array Geometry: Transition from a linear to a circular emitter arrangement. This ensures all emitters are equidistant from the MS inlet, creating a uniform electric field so all emitters operate optimally with the same applied voltage [3].

- Minimize Emitter-Inlet Spacing: Reduce the distance between the emitter array and the MS inlet to 1-1.5 mm to mitigate shielding effects. Caution: This may limit droplet desolvation for higher flow rates [3].

- Visual Inspection: Use a stereomicroscope to visually confirm stable electrospray plume formation from each emitter during operation [3].

FAQ 2: I am observing peak broadening and a loss of chromatographic resolution after installing the multi-emitter array.

This indicates the introduction of excessive dead volume or band broadening in the fluidic path [11].

- Problem: Post-column dead volume can cause mixing of separated analytes, degrading peak shape and resolution.

- Solution:

- Verify Low Dead Volume Design: Ensure the multi-emitter array is constructed with minimal internal volume. The capillary-based design inherently has low dead volume [11].

- Check All Fluidic Connections: Inspect and ensure all fittings (e.g., the union connecting the LC column to the emitter array) are tight and use zero-dead-volume fittings where possible to prevent volume addition [12].

- Confirm Flow Path Integrity: Use narrow internal diameter tubing and keep the connection between the column and the emitter array as short as possible [12].

This often points to ion transmission inefficiencies at the MS interface [11].

- Problem: Standard MS inlets are designed for a single point source of ions and cannot efficiently capture and transmit the larger ion clouds produced by a multi-emitter array.

- Solution:

- Use a Matched Multi-Capillary Inlet: Interface the emitter array with a custom heated inlet that contains a matching pattern of capillaries. This allows each emitter to spray into its own dedicated inlet, dramatically improving ion sampling efficiency [11].

- Employ Tandem Ion Funnels: The increased gas load from a multi-capillary inlet requires enhanced vacuum stage ion transmission. A tandem ion funnel interface (e.g., a high-pressure funnel at 18 Torr followed by a conventional funnel at 1.3 Torr) is highly effective at transmitting the increased ion current [11].

- Optimize Inlet Temperature: Ensure the multi-capillary inlet is heated sufficiently (e.g., 120-125°C) to aid in droplet desolvation [11] [3].

FAQ 4: My emitters are clogging frequently. How can I improve robustness?

Clogging is a common issue with narrow-orifice emitters [11].

- Problem: Particulates in the sample or mobile phase can block the emitter orifices.

- Solution:

- Use Chemically Etched Emitters: Emitters fabricated by chemical etching do not have an internal taper and can be made with relatively large orifices (e.g., 20-µm-i.d.), which are far less prone to clogging compared to pulled tips [11].

- Filter Samples and Mobile Phases: Always use filtered buffers and centrifuge or filter protein and peptide samples prior to loading.

- Use Guard Columns: Install a guard column before the analytical column to capture particulates and contaminants that could otherwise travel downstream and clog the emitters [12].

The following table summarizes key quantitative improvements observed when using multi-emitter arrays for LC-MS analyses.

Table 1: Performance Enhancement of Multi-Emitter Arrays in LC-MS Applications

| Performance Metric | Single Emitter / Inlet | 19-Emitter Array / Multi-Inlet | Improvement Factor | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Signal Intensity | Baseline | Increased | 11-fold (average) | Tryptic digest of spiked human plasma [11] |

| LC Peak Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Baseline | Increased | ~7-fold | Trace peptide analysis [11] |

| Electrospray Current | Lower | Higher | - | Improved ionization efficiency with circular arrays [3] |

| System Robustness | Prone to clogging | High | - | Use of 20-µm-i.d. etched emitters [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Flow-Splitting Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries | Fabrication of individual and multi-emitters | 20 µm i.d. / 150 µm o.d. [11] |

| Devcon HP250 Epoxy | Sealing capillaries in array housing; provides fluidic seal and mechanical stability [11] | High-performance, heat-cured epoxy |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Chemical etching of capillary ends to create tapered nanoESI emitters [11] | 49% solution; requires extreme caution |

| Multi-Capillary Heated Inlet | MS interface for efficient ion sampling from multi-emitter arrays [11] | e.g., 9 capillaries, 490 µm i.d., 4.4 cm long |

| Tandem Ion Funnel Interface | High-efficiency ion transmission under increased gas loads from multi-inlets [11] | Two ion funnels at different pressures (e.g., 18 Torr and 1.3 Torr) |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Modifying eluent for efficient ionization and separation in LC-MS [11] | Acetic Acid (HAc), Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Flow Splitting LC-MS Workflow

Electric Field Uniformity in Emitter Geometries

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Emitter Array Performance

FAQ 1: Why do my emitter arrays show inconsistent spray currents and unstable ionization? This is a classic symptom of electrical interference or "shielding effects" between closely spaced emitters in an array [3]. In a linear or two-dimensional array, the outer emitters experience a stronger electric field than the inner emitters for the same applied voltage [3]. This prevents all emitters from operating optimally simultaneously [3].

- Solution: Consider using a circular emitter array geometry. This arrangement ensures all constituent emitters experience a uniform electric field, minimizing inter-emitter inhomogeneities [3]. If a linear array must be used, minimize the emitter-to-counter-electrode spacing to mitigate shielding effects, though this may limit droplet desolvation at higher flow rates [3].

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally verify if my emitter array is functioning uniformly? You can characterize performance by measuring electrospray current versus voltage (I-V) curves for the entire array and comparing it to a single emitter [3].

- Protocol:

- Install the multi-emitter array in a benchtop ESI interface that simulates the MS vacuum stage.

- Infuse a standard solution at a fixed flow rate per capillary (e.g., 100 nL/min/capillary).

- Use a picoammeter to measure the total electrospray current while gradually increasing the applied ESI voltage.

- Compare the I-V curve of the array with that of a single emitter. A well-functioning, uniform array will show a characteristic curve shift indicating coordinated operation [3]. Simultaneously, use a stereomicroscope to visually confirm stable Taylor cones form at all emitter tips simultaneously [3].

FAQ 3: I have increased total spray current with an emitter array, but my MS signal hasn't improved proportionally. Why? This indicates a bottleneck in ion transmission efficiency through your ESI-MS interface [10]. The increased current cannot be effectively transmitted to the mass analyzer.

- Solution: Evaluate your interface configuration. Conventional inlet capillary interfaces often have limited transmission. The Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN)-MS interface, which places the emitter inside the first vacuum stage, has demonstrated superior ion utilization efficiency compared to standard capillary inlets [10]. Ensure your instrument's ion optics (e.g., ion funnels) are tuned to handle the greater ion currents produced by the array [3] [10].

FAQ 4: What is the difference between "total spray current" and "analyte ion utilization efficiency," and which is more important?

- Total Spray Current: The raw electrical current measured from the electrospray plume, comprising all charged species—including analyte ions, solvent clusters, and other charged particles [10].

- Analyte Ion Utilization Efficiency: The proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted into gas-phase ions and transmitted through the interface to the detector [10]. This is a more meaningful metric for sensitivity.

A high total spray current does not guarantee a high abundance of usable analyte ions at the detector. Focus on optimizing for analyte ion utilization efficiency for the best MS sensitivity [10].

Key Quantitative Metrics for Emitter Array Performance

The following table summarizes critical metrics for evaluating and troubleshooting emitter array setups.

| Metric | Definition | Measurement Technique | Significance & Target Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Spray Current | The total electric current generated by the electrospray, from all charged particles [10]. | Measured directly with a picoammeter connected to a charge collector in the vacuum interface [3] [10]. | Indicates overall ESI stability. Should be stable over time for a given voltage/flow rate. |

| Transmitted Ion Current | The portion of the total spray current that is successfully transmitted through the MS interface [10]. | Measured by using downstream ion optics (e.g., a low-pressure ion funnel) as a charge collector [10]. | Directly measures the interface's ion transmission capability. Higher is better. |

| Ion Utilization Efficiency | The proportion of analyte molecules converted into detected gas-phase ions [10]. | Correlate transmitted ion current with the observed abundance of a specific analyte in the mass spectrum (Extracted Ion Chromatogram, EIC) [10]. | The ultimate measure of source and interface performance. The goal is to maximize this value [10]. |

| Inter-Emitter Current Variance | The degree of variation in current output between individual emitters in an array. | Compare I-V curves of individual emitters or measure current from each emitter tip separately (complex). | Low variance indicates uniform electric field and emitter fabrication. Circular arrays improve uniformity [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Circular NanoESI Emitter Arrays [3]

This protocol details the creation of a uniform circular nanoelectrospray emitter array.

- Machining the Support Structure: Machine two identical polyetheretherketone (PEEK) disks (e.g., 5 mm diameter, 0.5 mm thick) with holes drilled in concentric circles (e.g., an outer ring of 19 holes spaced 500 μm apart).

- Capillary Assembly: Thread fused silica capillaries (e.g., 20 μm i.d./150 μm o.d.) through the aligned holes in the two disks. The disks should be separated by 3-4 mm to keep capillaries parallel.

- Fluidic Connection: Insert the distal ends of the capillaries into a tubing sleeve, seal with epoxy, and attach a standard nut and ferrule for fluidic connection.

- Polyimide Removal: Pump water through the capillaries at ~100 nL/min per capillary and immerse the ends in a hot Nanostrip bath to remove the polyimide coating.

- Chemical Etching: Etch the capillary ends in hydrofluoric acid (e.g., 49% HF) to form uniformly tapered emitters.

- Safety Note: HF is extremely hazardous and must be handled in a ventilated hood with appropriate personal protective equipment [3].

Protocol 2: Measuring Ion Utilization Efficiency [10]

This method evaluates the overall performance of your ESI source and interface.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a standard solution of a known analyte (e.g., a peptide like angiotensin I at 1 μM concentration in 0.1% formic acid).

- Current Measurement: Infuse the solution at a fixed nanoflow rate. Use the ion funnel in the vacuum interface as a charge collector to measure the transmitted ion current with a picoammeter.

- MS Detection: Acquire a mass spectrum of the standard solution and obtain the extracted ion current (EIC) or peak intensity for the specific analyte.

- Correlation and Calculation: The ion utilization efficiency is determined by correlating the transmitted electric current with the observed analyte ion intensity. A system with higher efficiency will produce a stronger MS signal for the same level of transmitted current [10].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for experiments involving emitter arrays and ionization efficiency.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries (e.g., 20 μm i.d./150 μm o.d.) | The base material for fabricating nanoESI emitters. The small inner diameter is ideal for low-flow nanoelectrospray operations [3] [10]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Used for chemical etching of fused silica capillaries to create sharp, tapered emitters with uniform geometry [3]. |

| Standard Peptide Mix (e.g., Angiotensin I, Fibrinopeptide A) | Well-characterized model analytes used for system calibration, performance testing, and measuring ion utilization efficiency [10]. |

| Ion Funnel Interface | An electrodynamic ion optic that improves the transmission of ions from the ESI source into the mass analyzer, crucial for handling increased currents from emitter arrays [3] [10]. |

| PEEK Disks & Fittings | Used to construct the rigid support structure that holds multiple emitters in a precise geometric arrangement (linear or circular) [3]. |

From Design to Data: A Practical Guide to Implementing Emitter Arrays in Your MS Workflow

Within research aimed at improving ionization efficiency with emitter arrays, the fabrication of uniform, high-performance emitters is a foundational challenge. Chemically etched fused silica capillaries have emerged as a superior alternative to mechanically pulled emitters for creating nanoelectrospray ionization (nESI) sources. These etched emitters are critical components for applications ranging from high-sensitivity mass spectrometry in proteomics to drug development [13] [2].

The primary advantage of chemical etching is its ability to produce emitters with no internal taper, which significantly reduces the risk of clogging compared to pulled emitters [13]. Furthermore, the process can be controlled to create emitters with extremely thin walls at the orifice and high aspect ratios, which facilitate stable electrospray at ultra-low flow rates (e.g., 5 nL/min), leading to enhanced ionization efficiency and reduced ion suppression effects [13]. This technical note provides a detailed guide and troubleshooting resource for implementing this critical fabrication technique.

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Etching of Fused Silica Emitters

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for the chemical etching of fused silica capillaries, based on established procedures [13] [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Fused Silica Capillary Tubing: Standard polyimide-coated capillaries (e.g., 150 µm o.d./20 µm i.d. or 150 µm o.d./10 µm i.d.) [13] [2].

- Aqueous Hydrofluoric Acid (HF): 49% concentration. Warning: HF is extremely hazardous and corrosive. It must be used in a ventilated fume hood with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including acid-resistant gloves and a face shield. [3] [13].

- Water Purification System: Deionized water (e.g., from a Barnstead Nanopure system) [3] [13].

- Syringe Pump: Capable of delivering low flow rates (e.g., 0.1 µL/min) [13].

- Gas-Tight Syringe: (e.g., 250 µL) [13].

- Polyimide Stripping Solution: Such as Nanostrip 2X (heated to ~90-100°C) [3] [2].

- Basic Tools: Rotary tubing cutter, microscope, translation stages, and a stereomicroscope for inspection.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Capillary Preparation Begin by removing a ~1 cm length of the polyimide coating from the end of the fused silica capillary. This can be achieved by burning the coating away carefully or, for better reproducibility, by immersing the capillary end in a heated bath of Nanostrip 2X for approximately 20-25 minutes [3] [2]. After stripping, thoroughly rinse the capillary with deionized water.

Step 2: Etching Setup Mount the capillary vertically on a translation stage. Connect the unetched end of the capillary to a water-filled syringe via a metal union, and secure the syringe in the syringe pump. Set the pump to deliver water at a constant flow rate of 0.1 µL/min [13]. This internal flow is critical, as it prevents the HF etchant from entering and enlarging the capillary's inner diameter [13].

Step 3: The Etching Process Slowly immerse the stripped end of the capillary ~1 mm into the reservoir of 49% HF acid. Due to surface tension, a meniscus of etchant will climb the hydrophilic silica exterior above the bulk solution level [13]. The etch rate is highest at the solution line and decreases with distance up the capillary, creating a natural taper. The process continues autonomously until the silica at the point of immersion in the bulk solution is completely severed, at which point etching effectively stops, ensuring high inter-emitter reproducibility [13].

Step 4: Post-Etching Cleaning Once the capillary separates (or after the desired etch time), immediately remove the emitter and rinse the etched tip extensively with deionized water to neutralize and remove any residual acid.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and mechanism of the chemical etching process.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common problems encountered during the emitter etching process and provides evidence-based solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Etching Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irregular or Non-Reproducible Taper Geometry | Inconsistent internal water flow rate; Variable meniscus formation due to surface contamination. | Calibrate the syringe pump before use. Ensure the polyimide coating is completely removed and the silica surface is clean [13]. |

| Emitter Orifice is Clogged | Particulate matter in the water or capillary; Inadequate internal water flow allowing etchant ingress. | Filter all solvents (water) before use. Verify the pump is functioning and the capillary is not kinked [13]. |

| Etching Process is Too Slow/Fast | HF acid concentration or temperature is sub-optimal. | The process is typically self-limiting. For consistency, maintain a standard lab temperature. Do not increase HF concentration due to safety risks [13]. |

| Weak or Fragile Emitter Tips | Over-etching after the capillary separates. | The self-limiting nature of the process typically prevents this. Ensure the capillary is removed promptly after separation [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does chemical etching improve performance in emitter arrays compared to single emitters? Emitter arrays split the total liquid flow from a separation (like LC) into multiple nano-flow electrosprays, enhancing ionization efficiency. For arrays, emitter uniformity is paramount to ensure each sprayer operates optimally under the same applied voltage. Chemical etching provides the high inter-emitter reproducibility required for this, minimizing electric field inhomogeneities that plague linear arrays [3] [2].

Q2: Why are etched emitters less prone to clogging than pulled emitters? Pulled emitters have a long, internal taper that narrows gradually, which can easily trap particulate matter. In contrast, the chemical etching method produces emitters with no internal taper—the inner diameter remains constant along the capillary length. The material is only removed from the outside, resulting in a thin-walled orifice that is far less likely to clog [13].

Q3: Can this etching process be scaled for parallel fabrication? Yes, the methodology can be adapted for higher throughput. One approach involves using a multi-port manifold to split the water flow from a single syringe pump to multiple capillaries simultaneously, allowing a bundle of emitters to be etched in parallel under identical conditions [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists the essential materials and their specific functions in the emitter fabrication process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillary | The base material to be etched; chosen for its excellent thermal conductivity, UV transparency, and well-defined surface chemistry [14]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | The primary etchant; reacts with silica (SiO₂) to form gaseous SiF₄, thereby removing material isotropically [13]. |

| Buffered Oxide Etch (BOE) | An alternative etchant comprising HF and NH₄F. The buffering agent can provide a more controlled etch rate and surface morphology in some applications [15]. |

| Deionized Water | Used to fill the capillary interior during etching to protect the inner diameter from enlargement [13]. |

| Nanostrip 2X | A chemical solution used to cleanly and completely remove the polyimide coating from the capillary exterior without mechanical damage, ensuring uniform etching [3] [2]. |

Quantitative Data & Performance Metrics

The success of the etching process is validated by key performance metrics compared to traditional pulled emitters.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Etched vs. Pulled Emitters

| Parameter | Chemically Etched Emitters | Traditional Pulled Emitters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Taper | None (constant i.d.) | Present (narrowing i.d.) | [13] |

| Clogging Tendency | Low | High | [13] |

| Wall Thickness at Orifice | Extremely thin | Thick | [13] |

| Inter-Emitter Reproducibility | High | Varying | [13] |

| Stable ESI Flow Rate | As low as 5 nL/min | Typically > 20 nL/min | [13] |

| Longevity in LC-MS Analysis | ~4x more analyses before failure | Standard | [13] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SPIN-MS Issues & Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable Spray / Current Fluctuations | Inconsistent ion current; visible sputtering at emitter tip. | Electrical breakdown in the subambient pressure environment. | Ensure counter electrode is biased ~50 V higher than the front ion funnel plate and utilize a CO2 sheath gas around the emitter for stability. [10] | |

| Insufficient droplet desolvation. | Utilize the heated CO2 gas (~160 °C) around the emitter; confirm flow rate with a flow meter. [10] | |||

| Low Sensitivity / Ion Signal | Signal intensity lower than expected compared to standard ESI. | Ion loss in the interface; inefficient transmission. | Verify positioning: SPIN emitter should protrude ~2 mm and be placed ~1 mm from the first ion funnel electrode. [10] | |

| Inadequate focusing by the ion funnel. | Optimize the RF voltage amplitude on the high-pressure ion funnel (e.g., ~250 Vp-p at 1.3 MHz). [16] | |||

| Emitter clogging or degradation. | Fabricate new emitters via chemical etching of fused silica capillaries. [3] [16] | |||

| Poor Desolvation | High chemical noise; increased solvent cluster ions. | Vaporization energy load is too low. | Confirm the temperature and flow rate of the heated desolvation gas (CO2). [10] [16] | |

| Ion funnel RF voltage is sub-optimal. | Systemically increase the ion funnel RF voltage to enhance focusing and collisional heating, which aids desolvation. [16] | |||

| Interfacing with LC Separations | Preservation of chromatographic fidelity when using multi-emitter arrays. | Post-column band broadening. | Use multi-emitter arrays to divide LC eluent post-column; ensures separation efficiency is maintained. [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of the SPIN source over a conventional atmospheric pressure ESI source? The primary advantage is the removal of the restrictive inlet capillary, which is a major site for ion loss. By placing the emitter within the first vacuum stage (at ~30 Torr) adjacent to the ion funnel, the SPIN source allows for more efficient ion capture and transmission. This design has demonstrated a ~5-fold improvement in MS sensitivity compared to a standard ESI source with a heated capillary inlet [16].

Q2: How does the SPIN interface improve ionization efficiency, especially concerning emitter arrays? The SPIN interface enhances the overall ion utilization efficiency—the proportion of analyte molecules converted into gas-phase ions and transmitted to the mass analyzer. When coupled with multi-emitter arrays, which provide a "brighter" ion source, the SPIN interface's efficient transmission mechanism prevents the increased current from being lost at a limiting inlet. This combination results in a greater proportion of generated ions reaching the detector [10].

Q3: Can SPIN-MS be used with typical reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) solvents? Yes. A key development of the SPIN source is its effective operation with solvents like methanol and water mixtures, which are standard for RPLC, at flow rates compatible with nanoESI (e.g., 300 nL/min) [16].

Q4: Why would I use an emitter array with a SPIN source, and what design is optimal? Emitter arrays increase the total ion current produced by providing multiple simultaneous electrospray plumes. When interfaced with a SPIN source and a matching multi-capillary inlet, this can lead to a >10-fold increase in sensitivity [3]. A circular emitter array is optimal because it ensures all emitters experience a uniform electric field, overcoming the issue of electrical interference and shielding that plagues linear arrays. This uniformity allows all emitters to operate optimally under the same applied voltage [3].

Q5: What is the role of the ion funnel in the SPIN interface, and how should it be operated? The electrodynamic ion funnel is critical for capturing, focusing, and transmitting ions while also providing an effective region for droplet desolvation via collisional heating. Typical operating parameters for the high-pressure ion funnel in a SPIN configuration include an RF amplitude of ~250 Vp-p at 1.3 MHz and a DC gradient of ~18.5 V/cm [16]. The RF voltage is particularly important for efficient ion focusing.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Fabrication of Etched Fused Silica NanoESI Emitters

This protocol is essential for creating robust, low-flow-rate emitters for both standard and SPIN-MS applications [3] [16].

Materials:

- Fused silica capillaries (e.g., 20 μm i.d./150 μm o.d. or 10 μm i.d./150 μm o.d., Polymicro Technologies).

- Hydrofluoric Acid (HF, 49%), EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS.

- Nanostrip 2X (or similar oxidizing cleaning solution).

- Syringe pump, high-voltage power supply, ventilated fume hood, and appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Procedure:

- Capillary Preparation: Cut a suitable length of fused silica capillary.

- Polyimide Removal: Pump water through the capillary at ~100 nL/min. Submerge the end of the capillary in a bath of heated (~90 °C) Nanostrip for approximately 20 minutes to remove the polyimide coating. Rinse thoroughly.

- Chemical Etching: Transfer the capillary end to a bath of 49% HF. Continue to pump water. The HF will isotropically etch the fused silica, creating a fine, tapered tip over ~20-45 minutes.

- Rinsing and Storage: Remove the capillary from HF, flush extensively with purified water and then with methanol, and allow to dry. Store in a clean environment.

Safety: HF is extremely corrosive and toxic. All work must be performed in a ventilated fume hood using appropriate PPE, including acid-resistant gloves and face protection. Have calcium gluconate gel readily available.

Protocol: Establishing a Stable SPIN-MS Analysis

This procedure outlines the steps to set up and optimize a SPIN-MS experiment.

Materials:

- Mass spectrometer modified with a high-pressure ion funnel and SPIN source chamber.

- Fabricated nanoESI emitter (see Protocol 3.1).

- Syringe pump and HPLC-grade solvents.

- High-voltage power supply and picoammeter.

Procedure:

- Emitter Installation: Mount the etched emitter inside the vacuum chamber via a vacuum feedthrough. Position the tip so it protrudes ~2 mm from its counter electrode and is ~1 mm from the first electrode of the ion funnel [10].

- Fluidic Connection: Connect the emitter to a syringe filled with your sample or LC effluent via a stainless steel union. Use the syringe pump to infuse the solution at a nanoflow rate (e.g., 200-400 nL/min).

- Gas and Vacuum Setup: Initiate the flow of heated CO2 desolvation gas (~160 °C). Activate the vacuum system to bring the source chamber pressure to the operating range of 19-30 Torr [10] [16].

- Electrical Configuration:

- Optimization and Data Acquisition:

- Use a camera to visually confirm a stable Taylor cone.

- Use a picoammeter to monitor transmitted current.

- Systemically adjust the ion funnel RF voltage and the ESI voltage to maximize the transmitted ion current and signal intensity in the mass spectrometer.

SPIN-MS Interface Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Specification / Example | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries | 10-20 μm i.d., 150 μm o.d. (Polymicro Technologies) | The standard substrate for fabricating chemically etched, tapered nanoelectrospray emitters for low-flow-rate applications. [3] [16] |

| Chemical Etchants | Hydrofluoric Acid (49%), Nanostrip 2X | HF etches fused silica to form sharp emitter tips; Nanostrip removes the polyimide coating prior to etching. [3] |

| ESI Solvents | Methanol, Water, Acetonitrile, with 0.1-1% Acetic or Formic Acid | HPLC-grade solvents with volatile additives are used to create electrospray-compatible solutions and standard peptide mixtures. [10] [16] |

| Standard Peptide Mixture | Angiotensins, Bradykinin, Fibrinopeptide A, etc. (Sigma-Aldrich) | A well-characterized standard mixture is crucial for system performance evaluation, sensitivity testing, and comparing interface configurations. [10] |

| Ion Funnel Instrumentation | Tandem ion funnel interface capable of ~30 Torr operation. | The core component of the SPIN interface that enables efficient ion capture, focusing, and transmission from the subambient pressure region. [10] [16] |

Circular vs. Linear Array Geometries for Optimal Electric Field Uniformity

Within research focused on improving ionization efficiency with emitter arrays, a fundamental challenge is overcoming the deleterious effects caused by electrical interference among neighboring electrospray ionization (ESI) emitters. In linear or two-dimensional arrays, outer emitters experience higher electric fields than interior emitters for the same applied voltage, making it difficult to operate all emitters optimally under a single applied potential. This phenomenon, known as electric field inhomogeneity or shielding, becomes increasingly problematic as emitter density increases and can force emitters to function in different operational regimes, compromising data quality and experimental reproducibility [3]. The geometry of the emitter array itself serves as a primary factor in determining the degree of this field uniformity, directly impacting the sensitivity, quantitation, and robustness of analytical measurements.

Technical FAQs: Resolving Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Why do my linear array emitters produce inconsistent spray currents and signal intensities?

This inconsistency is a classic symptom of inter-emitter electric field inhomogeneity. In a linear array, the electrical shielding effect causes outer emitters to experience a stronger electric field than those in the interior for the same applied voltage [3]. Consequently, the outer emitters may operate in an optimal spraying regime while the interior emitters are under-performing, or vice-versa if the voltage is adjusted for the interior ones. This leads to a non-uniform spray current across the array and fluctuating signal intensities in your mass spectrometer.

Q2: How can I diagnose electric field shielding in my existing array setup?

You can diagnose shielding by characterizing the current-versus-voltage (I-V) curves for individual emitters within your array while they are all active. If the I-V curves shift depending on an emitter's position (interior vs. exterior), it confirms the presence of significant shielding effects [3]. Visual inspection of the spray plumes using a stereomicroscope during operation can also reveal differences in the initiation voltage and plume stability between edge and center emitters.

Q3: My linear array performs poorly at increased emitter densities. What is the underlying cause?

The deleterious effects of electric field inhomogeneity become more pronounced as the distance between emitters decreases [3]. When you increase emitter density in a linear array, the electrical interference between adjacent tips intensifies. This exacerbates the shielding problem, making it progressively harder to find an applied voltage that brings all emitters into a stable electrospray regime. This is a fundamental limitation of the linear geometry for high-density applications.

Q4: Are there fabrication advantages to using a circular array geometry?

Yes, the circular geometry offers a key fabrication advantage: symmetry. Because all emitters in a circular array are, by design, in equivalent positions relative to each other and the counter-electrode (e.g., the mass spectrometer inlet), they naturally experience a more uniform electric field [3]. This inherent symmetry simplifies the voltage optimization process and makes the array's performance more predictable and robust compared to a linear layout.

Troubleshooting Guides: From Problem to Solution

Problem: Inconsistent Ionization Efficiency Across the Array

- Step 1: Verify Emitter Functionality. Individually test each emitter in a single-emitter configuration to ensure they are all fabricated correctly and are free from clogs.

- Step 2: Measure Spatial I-V Curves. With the full array active, use a picoammeter to measure the total electrospray current and, if possible, the current from individual emitters at different applied potentials. Plot the I-V curves [3].

- Step 3: Identify Shielding. Compare the I-V curves. A systematic variation in the voltage required for spray initiation and current magnitude based on emitter position confirms shielding.

- Solution: Transition from a linear to a circular array geometry. Research shows that circularly arranged emitters experience a uniform electric field, eliminating the positional bias and allowing all emitters to operate optimally under a single applied voltage [3].

Problem: Signal Suppression and Poor Quantitation

- Step 1: Check for Field Inhomogeneity. Follow the diagnostic steps above to confirm electric field shielding as a potential contributor.

- Step 2: Review Emitter-Inlet Spacing. In linear arrays, a common workaround for shielding is to minimize the emitter-to-inlet distance (e.g., to ~1 mm). However, this can be insufficient for efficient droplet desolvation at higher flow rates, leading to increased chemical noise and ion suppression [3].

- Solution: Implement a circular array. The improved field uniformity allows for greater flexibility in the emitter-inlet spacing, enabling you to increase this distance for better droplet desolvation without sacrificing spray stability, thereby reducing ion suppression effects [3].

Experimental Data & Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes quantitative experimental comparisons between single, linear, and circular nanoESI emitters, demonstrating the performance advantages of the circular geometry.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of NanoESI Emitter Geometries

| Performance Metric | Single Emitter | Linear Emitter Array | Circular Emitter Array |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electric Field Uniformity | Excellent (N/A) | Poor (Position-dependent) [3] | Excellent (Uniform across emitters) [3] |

| Inter-Emitter Shielding | None | Significant [3] | Minimized [3] |

| Spray Current Stability | High | Low (Inconsistent across emitters) | High (Consistent across emitters) [3] |

| Sensitivity (vs. Single) | Baseline | >10-fold increase [3] | >10-fold increase, with improved robustness [3] |

| Optimal Emitter-Inlet Spacing | Flexible | Constrained (Must be small ~1mm) [3] | Flexible [3] |

| Scalability (Emitter Density) | N/A | Limited (Shielding worsens with density) [3] | High (Denser arrays are feasible) [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of a Circular NanoESI Emitter Array

This protocol details the methodology for creating and evaluating a circular nanoelectrospray emitter array, based on established research techniques [3].

Emitter Fabrication

Materials:

- Two identical PEEK disks (0.5 mm thick, 5 mm diameter), machined with a pattern of 200-μm-diameter holes in concentric circles (e.g., an outer ring with 19 holes).

- Fused silica capillaries (20 μm inner diameter / 150 μm outer diameter).

- Epoxy sealant.

- Nanostrip 2X solution (Caution: Corrosive).

- Concentrated (49%) Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) (Caution: Extremely hazardous; use fume hood and personal protective equipment).

Procedure:

- Assembly: Align the two PEEK disks and thread the fused silica capillaries through the drilled holes. The disks should be separated by 3-4 mm to ensure the capillaries run parallel.

- Fluidic Connection: Insert the proximal ends of the capillaries into a 750-μm-i.d. tubing sleeve, seal with epoxy, and attach a PEEK nut and ferrule for connection to your fluidic system.

- Polyimide Removal: Pump water through the capillaries at ~100 nL/min per capillary and immerse the distal ends in a bath of heated Nanostrip 2X at 90°C for approximately 20 minutes to remove the polyimide coating.

- Chemical Etching: Transfer the capillary ends to a bath of 49% HF to etch and form externally tapered emitters of uniform length. Monitor the process to achieve the desired tip geometry.

Electrospray Characterization & MS Interfacing

Equipment:

- Mass Spectrometer (e.g., Triple Quadrupole) with a modified ion funnel interface.

- Custom multi-capillary heated inlet (e.g., 18 capillaries arranged to match the emitter pattern).

- Picoammeter.

- Stereomicroscope.

- Benchtop ESI interface simulating the first vacuum stage.

Testing Procedure:

- Current-Voltage (I-V) Profiling: Interface the array with the benchtop ESI setup. Apply a range of voltages to the emitter array with the multi-capillary inlet grounded and heated (e.g., 120°C). Use the picoammeter to measure the total emitted current and the current transmitted through the inlet. This generates I-V curves to assess performance and uniformity [3].

- Visual Inspection: Use the stereomicroscope to observe the electrospray plumes forming at each emitter tip simultaneously. Check for consistent Taylor cone formation and plume stability across all emitters.

- MS Performance: Connect the array to the mass spectrometer via the multi-capillary inlet. Perform a standard analysis (e.g., of a peptide mixture) and compare sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio, and signal stability against data acquired from a single emitter.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Emitter Array Fabrication and Testing

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries | Forms the fluidic path and etched emitter tip. | 20 μm i.d./150 μm o.d.; provides the substrate for nanoESI emitters [3]. |

| PEEK Disks & Fittings | Provides structural support and fluidic interfacing for the array. | Machined with precise hole patterns; enables stable circular geometry [3]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Chemical etching agent to sharpen capillary ends into nanoESI emitters. | Extreme hazard. Creates uniform, externally tapered emitters [3]. |

| Nanostrip 2X | Removes the polyimide coating from capillaries prior to etching. | Corrosive. Required for exposing the fused silica for HF etching [3]. |

| Multi-Capillary Inlet | Counter-electrode and vacuum interface for the mass spectrometer. | Heated capillary inlet with a pattern matching the emitter array for efficient ion transmission [3]. |

| Tandem Ion Funnel | MS interface modification to handle increased ion currents from arrays. | Replaces standard skimmer; improves ion transmission and focusing for multiplexed sources [3]. |

Visual Guide: Electric Field Dynamics in Emitter Geometries

The diagram below illustrates the core difference in electric field distribution between linear and circular array geometries, which is the fundamental concept behind this technical discussion.

The Role of Individualized Sheath Gas Capillaries for Spray Stability

A primary challenge in advancing emitter array technology for electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) is generating a stable and uniform spray from each emitter, particularly in subambient pressure environments. Individualized sheath gas capillaries are a critical innovation that addresses this challenge. By providing a localized, concentric flow of gas around each emitter in an array, this technology ensures spray stability, significantly enhances droplet desolvation, and ultimately leads to marked improvements in overall ionization efficiency and MS sensitivity. Integrating this emitter array design with a subambient pressure ionization (SPIN) source essentially eliminates the major ion losses associated with standard atmospheric pressure inlets, creating a superior platform for high-sensitivity analyses in applications from drug development to fundamental research [2].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a sheath gas necessary for each emitter in an array, rather than using a common gas chamber? A1: Individualized sheath gas capillaries provide precise, concentric gas flow to each emitter. This ensures that every tip in the array receives a uniform stabilizing force, which is crucial for generating multiple, independent, and stable electrosprays. A common gas chamber cannot guarantee this uniformity, often leading to spray instability in some emitters and degraded overall performance of the array [2].

Q2: What is the impact of spray instability on my mass spectrometry results? A2: Unstable spray, characterized by pulsating or multi-jet modes, leads to high signal variance and poor reproducibility. This instability causes fluctuating ion currents, which can result in inaccurate quantitation, reduced sensitivity, and missed detections of low-abundance analytes, ultimately compromising data reliability [17].

Q3: My emitter array is producing inconsistent signals. Could the spray mode be a factor? A3: Yes. The spray mode (e.g., single cone-jet, multi-jet, rim-jet) directly impacts signal stability. The rim-jet mode has been associated with the lowest standard deviation and highest ionization efficiency. Inconsistent signals often indicate an uncontrolled or shifting spray mode, which can be mitigated by optimizing the electric field and sheath gas flow to establish a stable rim-jet or single cone-jet mode [17].

Q4: How does the SPIN source environment influence the need for sheath gas? A4: In the subambient pressure (10-30 Torr) environment of a SPIN source, traditional electrospray is more prone to instability and inefficient droplet desolvation due to the reduced pressure. A sheath gas, particularly when heated, is essential to enhance droplet desolvation and maintain a robust electrospray plume, ensuring high ion utilization efficiency in this optimized interface [2].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions for Emitter Array Spray Stability

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable or Pulsating Spray from Array | Insufficient or non-uniform sheath gas flow; Incorrect applied voltage; Emitter tip imperfections [2] [17]. | Verify individual sheath gas capillary connections and flows; Systematically increase applied voltage to transition to a stable spray mode; Inspect and re-cut emitter tips to ensure they are smooth [2]. |

| Low MS Sensitivity & High Background | Inefficient droplet desolvation; Spray plume not optimally sampled by MS inlet [2] [18]. | Incorporate a heated desolvation gas (e.g., CO2) into the sheath gas; For SPIN sources, ensure emitter is positioned close to the ion funnel for maximum plume sampling [2]. |

| Non-Uniform Signal Across Emitters | Clogged or obstructed individual emitter or gas capillary; Variability in emitter tip geometries [2]. | Check for blockages by applying pressure to each emitter separately; Ensure emitters are etched to a uniform length and tip diameter during fabrication [2]. |

| Unexpected Spray Mode (e.g., Multi-jet) | Applied voltage too high for given flow rate and geometry; Solvent properties (e.g., surface tension, conductivity) [17]. | Lower the applied voltage to transition from multi-jet to a stable cone-jet or rim-jet mode; Adjust solvent composition (e.g., add modifier like formic acid) to alter conductivity and surface tension [17]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Fabrication of Emitter Arrays with Individualized Sheath Gas Capillaries

This protocol details the construction of a multi-emitter ESI source where each emitter is surrounded by its own concentric sheath gas capillary, as developed for use in subambient pressure ionization sources [2].

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials: Table 2: Essential Materials for Emitter Array Fabrication

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Emitter Capillaries | 150 μm o.d., 10 μm i.d. | Forms the nanoelectrospray tip for sample emission. |

| Fused Silica Sheath Gas Capillaries | 360 μm o.d., 200 μm i.d. | Provides concentric, individualized sheath gas flow to each emitter. |

| PEEK Sleeve & Disk Spacer | 0.055 in. i.d.; Disk with 400 μm holes. | Holds capillary array in a precise geometric arrangement. |

| Epoxy | HP 250 (or similar high-vacuum epoxy) | Fixes capillaries in place and seals assembly. |