Chemometric Algorithms for Data Analysis: A Comparative Study of Classical and AI Methods in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of chemometric algorithms, from classical multivariate methods to modern artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, for spectroscopic and chromatographic data analysis.

Chemometric Algorithms for Data Analysis: A Comparative Study of Classical and AI Methods in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of chemometric algorithms, from classical multivariate methods to modern artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, for spectroscopic and chromatographic data analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it establishes foundational concepts, explores methodological applications across biomedical case studies, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a rigorous framework for validation and performance comparison. The study synthesizes findings to guide algorithm selection, enhance analytical precision in pharmaceutical applications, and outline future directions for intelligent, explainable chemometric systems in clinical research.

From Classical Chemometrics to AI: Foundational Principles and Definitions

Chemometrics, defined as the mathematical extraction of relevant chemical information from measured analytical data, is undergoing a revolutionary transformation. For decades, classical multivariate methods have formed the bedrock of spectroscopic analysis, enabling researchers to transform complex datasets into actionable insights. Traditional chemometric techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression have served as fundamental tools for calibration and quantitative modeling in spectroscopy for decades [1]. These linear methods have proven particularly effective for handling multivariate data in areas like spectroscopy, chromatography, and chemical engineering, where they excel at managing correlated variables and extracting meaningful patterns from chemical data [2].

The contemporary analytical landscape is now characterized by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which dramatically expand capabilities for data-driven pattern recognition, nonlinear modeling, and automated feature discovery. Modern AI encompasses several subfields crucial for chemometrics: Machine Learning (ML) develops models that learn from data without explicit programming, while Deep Learning (DL) employs multi-layered neural networks for hierarchical feature extraction. Generative AI extends these capabilities further by creating new data, spectra, or molecular structures based on learned distributions [1]. This paradigm shift enables analysis of increasingly complex datasets from hyperspectral imaging, high-throughput sensor arrays, and other advanced analytical platforms that generate massive, unstructured data sources [1] [3].

This comparative guide examines the performance, applications, and appropriate use cases for classical multivariate analysis, machine learning, and AI-driven approaches in chemometric data analysis. By providing objective performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and practical implementation guidelines, we aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge needed to select optimal strategies for their specific analytical challenges.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Domains

Table 1: Performance comparison of chemometric approaches across application domains

| Application Domain | Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | Key Performance Metrics | Superior Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Analysis (Quaternary Mixture) [4] | Classical Multivariate | PLS-1 | RMSEP: CAF=0.141, COD=0.269, PAR=0.492, PAP=0.219 | GA-ANN |

| Variable Selection + Multivariate | GA-PLS | RMSEP: CAF=0.099, COD=0.198, PAR=0.364, PAP=0.164 | ||

| Machine Learning | GA-ANN | RMSEP: CAF=0.075, COD=0.119, PAR=0.289, PAP=0.103 | ||

| Food Science (Cheese Macronutrients) [2] | Classical Chemometrics | PLS | R²: Fat=0.92, Protein=0.89 | ML (Extra Trees) |

| Machine Learning | Extra Trees | R²: Fat=0.96, Protein=0.94 | ||

| Spectroscopic Data (General Modeling) [5] | Linear Methods | iPLS with Wavelet | Varies by dataset; competitive in low-data regimes | Context-dependent |

| Deep Learning | CNN with Pre-processing | Improved with sufficient data; benefits from pre-processing |

Characteristic Profiles of Chemometric Approaches

Table 2: Characteristic profiles of chemometric approaches

| Attribute | Classical Multivariate | Machine Learning | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Algorithms | PCA, PLS, MCR-ALS [6] [1] | Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost [2] [1] | CNN, DNN, Transformers [5] [1] |

| Data Efficiency | High performance with small datasets [5] | Requires moderate data volume | Requires large datasets [1] |

| Nonlinear Handling | Limited | Strong capabilities [1] | Excellent for complex nonlinearities [1] |

| Interpretability | High (chemically intuitive) [3] | Moderate (feature importance) [1] | Low (requires XAI techniques) [1] |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Feature Engineering | Manual pre-processing crucial | Manual pre-processing beneficial | Automated feature extraction [1] |

| Computational Demand | Low | Moderate to High | High |

The performance data reveals several key patterns. In pharmaceutical applications for analyzing complex mixtures, machine learning approaches consistently outperform classical methods. The GA-ANN model demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for quantifying caffeine, codeine, paracetamol, and p-aminophenol in quaternary mixtures, with reductions in RMSEP of up to 46% compared to classical PLS [4]. Similarly, in food science applications, ensemble ML methods like Extra Trees achieved higher coefficients of determination (R² = 0.96 for fat, 0.94 for protein) compared to PLS models (R² = 0.92 for fat, 0.89 for protein) for predicting macronutrients in cheese using imaging spectroscopy [2].

However, classical methods maintain advantages in low-data regimes and offer greater interpretability. Studies comparing linear and deep learning models for spectroscopic data found that after exhaustive pre-processing selection, interval PLS (iPLS) variants showed better performance for smaller datasets (e.g., 40 training samples) and remained competitive with more data [5]. The intrinsic linearity of many spectroscopic measurements, governed by principles similar to the Beer-Lambert law, means that linear methods often provide simpler, robust data pipelines that are less computationally intensive [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pharmaceutical Mixture Analysis Protocol

The superior performance of GA-ANN for pharmaceutical analysis emerged from a rigorously designed experimental protocol [4]:

Sample Preparation: Researchers prepared a calibration set of 25 mixtures using a 4-factor, 5-level experimental design containing caffeine, codeine, paracetamol, and p-aminophenol (PAP) impurity. Concentration levels were strategically coded from -2 to +2 with center points at 3.6, 8, 12, and 4.5 μg/mL for CAF, COD, PAR, and PAP, respectively.

Spectral Acquisition: UV-Vis spectra were collected from 200-400 nm at 0.2 nm intervals using 1.00 cm quartz cells. The specific analytical range of 210-300 nm was selected for CAF, COD, and PAR, while 210-340 nm was used for PAP.

Variable Selection: Genetic Algorithms (GA) applied a "survival of the fittest" strategy among wavelengths to identify the most meaningful variables for model construction, enhancing prediction power and reducing data dimensionality.

Model Development & Validation: PLS-1, GA-PLS, and GA-ANN models were constructed using the calibration set, with prediction ability tested against an independent validation set of six mixtures covering concentrations within the calibration ranges.

Hyperspectral Imaging for Food Analysis Protocol

The comparison of chemometrics and ML for cheese macronutrient prediction employed hyperspectral imaging with specific methodological considerations [2]:

Sample Diversity: Researchers adopted a "broad-based approach" using 32 different cheese types from Dutch supermarkets to calibrate and validate NIR models, intentionally integrating diverse cheese varieties into a single model to enhance generalizability.

Spectral Processing: Reflectance values obtained from hyperspectral images were converted to absorbance values for improved interpretation. Average spectra were visually inspected for preliminary quality assessment.

Feature Selection: Multiple feature selection methods were applied to identify the most important wavelengths for predicting macronutrients, with common variables across algorithms including 941 nm, 948 nm, 977 nm, and other key wavelengths associated with cheese characteristics.

Algorithm Comparison: Models were evaluated based on prediction accuracy for fat and protein percentages, with Extra Trees (an ensemble ML algorithm) demonstrating superior performance for this application.

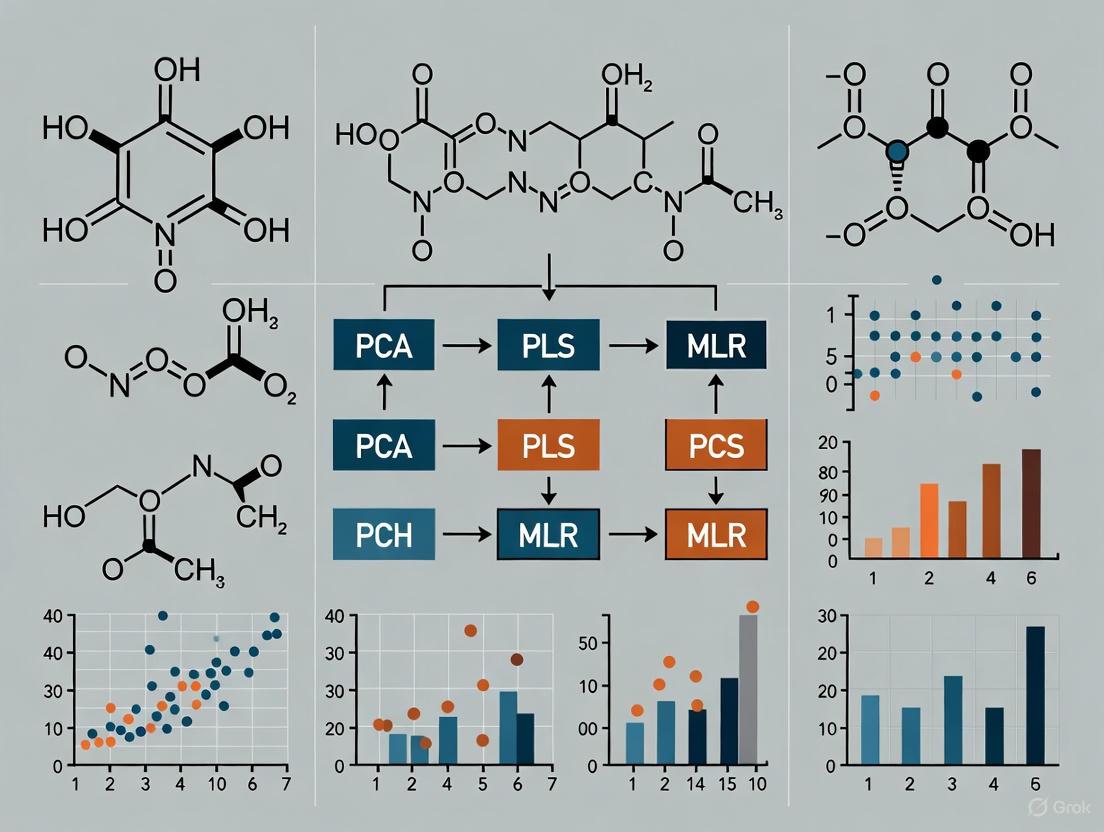

Strategic Workflow for Algorithm Selection

This workflow guides researchers through the critical decision points when selecting chemometric approaches, emphasizing the importance of data volume, relationship linearity, and interpretability requirements in determining the optimal analytical strategy.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for chemometric analysis

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Acquisition | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer [4] | Acquisition of absorption spectra (200-400 nm) | Pharmaceutical mixture analysis |

| NIR Hyperspectral Imaging System [2] [3] | Simultaneous spatial and chemical characterization | Food quality, pharmaceutical heterogeneity | |

| Fiber-optic SPR, Raman, Fluorescence Sensors [7] | In-situ chemical sensing | Environmental, biomedical, industrial monitoring | |

| Computational Frameworks | MATLAB with PLS_Toolbox [8] [4] | Implementation of multivariate calibration models | General chemometric analysis |

| Python with Scikit-learn, TensorFlow | Machine learning and deep learning implementation | Nonlinear modeling, complex pattern recognition | |

| SOLO or PLS_Toolbox [8] | Commercial chemometrics software | Educational purposes, industrial applications | |

| Data Processing | Genetic Algorithms (GA) [4] | Wavelength selection for model optimization | Feature selection for PLS and ANN |

| Wavelet Transforms [5] | Spectral data compression and denoising | Pre-processing for both linear and DL models | |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [6] [3] | Exploratory data analysis, dimensionality reduction | Initial data exploration, multivariate statistical process control |

Integrated Analytical Workflow

The integrated workflow illustrates how classical and AI-driven methods complement each other in a comprehensive analytical pipeline. Beginning with proper sample preparation and spectral acquisition, the process advances through essential pre-processing steps before exploratory analysis. The critical model selection phase determines whether classical, ML, or deep learning approaches are most appropriate based on data characteristics and research objectives, culminating in validation and deployment in Process Analytical Technology (PAT) contexts [3].

The chemometric landscape is evolving toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both classical and AI-driven methodologies. Future directions emphasize Explainable AI (XAI) techniques to maintain interpretability in complex models, with innovations in generative modeling, multimodal deep learning, and physics-informed neural networks poised to advance spectroscopic analyses further [9] [1]. Platforms like SpectrumLab and SpectraML are emerging as crucial tools for standardization and reproducibility in AI-driven chemometrics [9].

The integration of large language models and the development of more sophisticated generative AI applications promise to automate spectral interpretation while preserving chemical insight [9] [1]. As these technologies mature, researchers can expect increasingly powerful tools for handling complex analytical challenges across pharmaceutical development, food science, and environmental monitoring.

In conclusion, no single chemometric approach universally dominates all applications. Classical multivariate methods remain indispensable for linear systems, limited data environments, and when interpretability is paramount. Machine learning excels at handling nonlinear relationships and complex pattern recognition tasks with moderate data requirements. Deep learning offers powerful automated feature extraction for large-scale, complex datasets but demands substantial computational resources and data volumes. The optimal strategy involves selecting the right tool for the specific analytical challenge, often through systematic experimentation and validation, while emerging hybrid approaches promise to further blur the boundaries between these methodologies, creating more powerful and adaptable chemometric solutions for future scientific challenges.

In the field of chemometrics and spectral data analysis, the ability to extract meaningful chemical information from complex, high-dimensional datasets is paramount. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression represent two pillars of classical multivariate statistical methods for dimensionality reduction, pattern recognition, and quantitative calibration [10] [1]. These techniques are particularly valuable in spectroscopy, where datasets often contain thousands of correlated wavelength measurements, presenting challenges of multicollinearity and high dimensionality that render traditional univariate analyses ineffective [11] [12].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of PCA, PLS, and their key variants, focusing on their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in spectral data analysis. We present structured experimental data and protocols to empower researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate algorithm for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles and Algorithmic Relationships

Core Conceptual Differences

PCA is an unsupervised technique that identifies new orthogonal variables (principal components) that capture the maximum variance in the predictor dataset (X) without using information from the response variable (Y) [10] [13]. In contrast, PLS is a supervised method that identifies components that maximize the covariance between X and Y, making it particularly suited for prediction problems [10] [11] [13].

The fundamental distinction manifests in their objectives: PCA seeks to describe data structure through variance maximization, while PLS aims to predict responses through covariance maximization [10] [14]. This difference fundamentally impacts their application, performance, and interpretation in spectral analysis.

Workflow and Decomposition Logic

The analytical workflows for PCA and PLS regression in spectral data analysis differ significantly in their treatment of the relationship between spectral inputs and target outputs, as illustrated below:

Mathematical Formulations

PCA decomposes the data matrix X into principal components through either eigenvector decomposition or the Nonlinear Iterative Partial Least Squares (NIPALS) algorithm, which is particularly efficient for high-dimensional data [15] [12]. The NIPALS algorithm iteratively extracts components by maximizing the variance captured in each step, making it suitable for datasets with missing values [15] [12].

PLS regression finds weight vectors that simultaneously maximize the covariance between X and Y [11]. The algorithm computes components through a series of decompositions and deflations, with the objective function:

This optimization ensures that PLS components have both high variance and high correlation with the response, unlike PCA which considers only variance [11].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Key Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between PCA and PLS

| Feature | PCA | PLS/PLS-DA |

|---|---|---|

| Supervision | Unsupervised | Supervised [10] |

| Use of group information | No | Yes [10] |

| Primary objective | Capture overall variance | Maximize class separation/prediction [10] |

| Model interpretability | Moderate | High (via VIP scores) [10] |

| Risk of overfitting | Low | Moderate to high [10] |

| Best suited for | Exploratory analysis, outlier detection | Classification, biomarker discovery [10] |

| Dimensionality reduction focus | Maximum variance directions | Maximum covariance directions [11] |

| Output | Principal components | PLS components + prediction model [13] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimental performance comparison across application domains

| Application Domain | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurochemical prediction (FSCV) | PCR | Mean Absolute Error: Significantly higher | [16] |

| PLSR | Mean Absolute Error: Significantly smaller | [16] | |

| Spectral classification (Raman) | Machine Learning without PCA | Lower accuracy, risk of overfitting | [12] |

| Machine Learning with PCA | Improved accuracy, reduced overfitting | [12] | |

| Soil metal prediction (NIR) | Full-spectrum PLS | Variable performance depending on metal | [17] |

| FFiPLS (variable selection) | Superior for Al, Be, Gd, Y prediction | [17] | |

| Data imputation (Meteorological) | NIPALS-PCA (10% missing) | MAPE: 15.4% | [15] |

| EM-PCA (10% missing) | MAPE: 17.0% | [15] | |

| NIPALS-PCA (50% missing) | MAPE: 19.9% | [15] | |

| EM-PCA (50% missing) | MAPE: 19.1% | [15] |

Case Study: PCR vs. PLS on Synthetic Data

A comparative study using synthetic data clearly demonstrates how PLS can outperform Principal Component Regression (PCR) in specific scenarios [14]. When the target variable is strongly correlated with directions in the data that have low variance, the unsupervised nature of PCA becomes a limitation, as it greedily retains high-variance directions regardless of their predictive power [14].

In this experiment, the data was constructed so that the target y was strongly correlated with the second principal component, which explained less variance than the first component [14]. When both PCR and PLS were constrained to use only one component, the results were striking:

- PCR r-squared: -0.026 (performs worse than predicting the mean)

- PLS r-squared: 0.658 (good predictive power)

This performance gap occurs because PLS's supervised transformation preserves the data directions most predictive of the response, even when those directions have low variance [14]. The study confirmed that when PCR uses all components (2 in this case), it performs equivalently to PLS, but in practical applications where dimensionality reduction is desired, PLS often provides superior performance with fewer components [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Analytical Workflow

For consistent and reproducible results when applying PCA or PLS to spectral data, the following methodological framework is recommended:

Critical Validation Procedures for PLS Models

Given PLS's susceptibility to overfitting, rigorous validation is essential:

Cross-validation: Calculate R²Y (goodness of fit) and Q² (predictive ability) metrics. A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered a valid model, while Q² > 0.9 indicates outstanding predictive performance [10]. Monitor the gap between R²Y and Q² – large differences suggest potential overfitting [10].

Permutation testing: Perform 200 or more permutation tests by randomly shuffling the Y-variable to establish the statistical significance of the model. The original model's R²Y and Q² should be significantly higher than those from permuted datasets [10].

Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores: Identify features (wavelengths) that contribute most to group separation or prediction accuracy. Features with VIP scores > 1.0 are generally considered particularly influential [10].

Best Practices for PCA Implementation

Data standardization: For spectral data, standardize variables (wavelengths) to unit variance when the absolute scale of measurements varies significantly across wavelengths [12] [14].

Component selection: Use scree plots and cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components that capture meaningful variance without overfitting to noise [12].

Missing data handling: For datasets with missing values, implement iterative PCA algorithms like NIPALS-PCA or EM-PCA, which can effectively handle missing data [15]. Research shows NIPALS-PCA performs better with lower percentages (10-30%) of missing data, while EM-PCA excels with higher percentages (40-50%) [15].

Advanced Variants and Hybrid Approaches

PLS-DA for Classification Tasks

Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) extends PLS regression for classification problems by creating a dummy matrix of class memberships as the Y-block [10]. This supervised approach maximizes separation between predefined groups, making it particularly valuable for biomarker discovery and sample classification in spectral analysis [10].

Variable Selection Algorithms in PLS

Standard PLS regression uses the full spectral range, but performance can often be improved through intelligent variable selection:

- Deterministic methods: Interval PLS (iPLS) and Successive Projections Algorithm for interval selection in PLS (iSPA-PLS) systematically test specific spectral regions [17].

- Stochastic methods: Bio-inspired algorithms like the Firefly algorithm by intervals in PLS (FFiPLS) explore the variable space more extensively and have demonstrated superior performance for predicting specific metals in soil samples [17].

Integration with Machine Learning Frameworks

PCA is frequently employed as a preprocessing step for machine learning algorithms to address the curse of dimensionality with high-dimensional spectral data [12] [1]. Research demonstrates that PCA significantly improves the performance of support vector machines, k-nearest neighbours, and other classifiers when applied to Raman spectral data [12]. The NIPALS algorithm is particularly efficient for this purpose, enabling dimensionality reduction from thousands of spectral dimensions to a manageable number of principal components while retaining most of the relevant information [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key resources for implementing PCA and PLS in spectral research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectroscopic Techniques | NIR Spectroscopy | Non-destructive spectral data acquisition | Soil analysis, pharmaceutical QA [17] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Molecular fingerprinting | Illicit material identification, mixture analysis [12] | |

| FSCV (Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry) | Neurochemical measurement | Dopamine, serotonin detection [16] | |

| Preprocessing Methods | Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Scatter correction | Spectral normalization [17] |

| Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) | Path length effect correction | Spectral standardization [17] | |

| Savitzky-Golay Smoothing | Noise reduction | Signal-to-noise improvement [17] | |

| Variable Selection Algorithms | iPLS, iSPA-PLS | Deterministic interval selection | Wavelength range optimization [17] |

| FFiPLS | Stochastic variable selection | Enhanced prediction accuracy [17] | |

| Validation Techniques | Cross-validation (R²Y, Q²) | Model performance assessment | Overfitting prevention [10] |

| Permutation Testing | Statistical significance | Model validation [10] | |

| VIP Scores | Feature importance ranking | Biomarker identification [10] [17] | |

| Computational Implementations | NIPALS Algorithm | Efficient PCA computation | Handles high-dimensional, missing data [15] [12] |

| EM-PCA Algorithm | Missing data imputation | Incomplete dataset handling [15] |

PCA and PLS represent complementary approaches in the chemometrician's toolkit, each with distinct strengths and optimal application domains. PCA remains the gold standard for unsupervised exploratory analysis, data quality assessment, and outlier detection, while PLS and its variants excel in supervised prediction, classification, and biomarker discovery tasks.

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that PLS generally outperforms PCR when the predictive target is correlated with low-variance directions in the data, and that proper validation is crucial to avoid overfitting in supervised models. For contemporary spectral data analysis, researchers can further enhance these classical approaches through intelligent variable selection algorithms and integration with machine learning frameworks, leveraging the strengths of both traditional chemometrics and modern artificial intelligence.

Choosing between PCA and PLS fundamentally depends on the analytical objective: for unbiased data exploration and structural understanding, PCA is recommended; for prediction, classification, or when specific group separation is desired, PLS or PLS-DA is typically more appropriate. In many research workflows, these techniques are most powerful when used sequentially—employing PCA for initial data exploration and quality control, followed by PLS for targeted analysis and prediction.

The field of chemometrics, defined as the mathematical extraction of relevant chemical information from measured analytical data, is undergoing a paradigm shift through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) [1]. Modern analytical instruments, from chromatography–mass spectrometry to various spectroscopic methods, generate vast, complex datasets that are too large and intricate for traditional statistical methods to handle effectively [18]. In this context, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) have emerged as particularly powerful algorithms for analyzing chemical data. These methods are transforming chemical analysis across diverse domains including drug discovery, food authentication, biomedical diagnostics, and chemical safety prediction [1] [19] [20]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three algorithms, focusing on their applications, performance characteristics, and implementation considerations for chemical data analysis, framed within a broader thesis on comparative study of chemometric algorithms.

Algorithm Fundamentals and Chemometric Applications

Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Support Vector Machines are supervised learning algorithms that find the optimal decision boundary (hyperplane) separating classes or predicting quantitative values in high-dimensional spectral space [1]. For classification, SVM seeks the hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the nearest data points of different classes (called support vectors), providing robust discrimination even with noisy, overlapping, or nonlinear spectral data [1]. Through the use of kernel functions (linear, polynomial, or radial basis function), SVM can transform spectral data into higher-dimensional feature spaces, enabling nonlinear classification or regression [1].

In spectroscopic applications, SVMs perform well with limited training samples but many correlated wavelengths, making them highly suited for spectroscopic datasets [1]. They have been successfully applied to food authenticity, pharmaceutical quality control, process monitoring, and disease diagnosis based on vibrational spectral patterns [1]. Parameter tuning (regularization C, kernel width γ) and preprocessing (scatter correction, normalization) are key to achieving optimal performance [1].

Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that constructs a large number of decision trees using bootstrap-resampled spectral subsets and randomly selected wavelength features [1]. Each tree votes on the outcome, and the ensemble majority defines the final prediction [1]. In spectroscopy, RF offers strong generalization capability, reduced overfitting, and robustness against spectral noise, baseline shifts, and collinearity [1].

RF models are widely applied in spectral classification, authentication, and process monitoring, and can output feature importance rankings, helping spectroscopists identify diagnostic wavelengths or informative regions in the spectra useful for selective and accurate predictive modeling [1]. The Gini importance, a by-product of RF training, provides a relative ranking of spectral features by calculating how much each feature decreases the weighted impurity in the trees [21]. This feature importance measure has been found to provide superior means for measuring feature relevance on spectral data compared to univariate approaches [21].

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

Extreme Gradient Boosting is an advanced boosting algorithm that builds an ensemble of decision trees in a sequential, gradient-based manner [1] [19]. Each new tree focuses on correcting the residual errors of prior trees [1]. XGBoost includes regularization, parallel computation, and optimized gradient descent, offering high computational efficiency and predictive accuracy [1] [19]. In spectroscopy, XGBoost excels in complex, nonlinear relationships typical of food quality, pharmaceutical composition, and environmental analysis [1].

XGBoost often achieves state-of-the-art performance in both regression and classification tasks, outperforming traditional chemometric models when sufficient labeled spectral data are available [1]. The algorithm has demonstrated remarkable performance on both high and low diversity datasets in chemical applications, along with an ability to detect minority activity classes in highly imbalanced datasets [19]. Despite its power, XGBoost's models are less transparent, motivating the use of explainable AI techniques to interpret wavelength contributions [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance comparisons across chemical data applications:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms on Chemical Data Tasks

| Application Domain | Dataset Characteristics | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactive Molecule Prediction [19] | 7 chemical datasets; Active/Inactive compounds | XGBoost | Predictive accuracy | Outperformed RF, SVM, RBFN, and Naïve Bayes |

| Random Forest | Predictive accuracy | Reliable performance, but outperformed by XGBoost | ||

| SVM | Predictive accuracy | Competitive but outperformed by ensemble methods | ||

| Food Moisture Analysis [18] | NIR spectra of Porphyra yezoensis | XGBoost | Determination accuracy | Recommended as most reliable for industrial application |

| CNN/ResNet | Determination accuracy | Evaluated but outperformed by XGBoost | ||

| Chemical Safety Prediction [20] | 2562 chemical incidents; 17 variables | Stacking (SVM-RF-XGBoost) | Accuracy: 0.945, F1: 0.792 | Superior to individual models |

| XGBoost Only | Accuracy: 0.922, F1: 0.727 | Strong individual performance | ||

| Random Forest Only | Accuracy: 0.914, F1: 0.694 | Solid individual performance | ||

| SVM Only | Accuracy: 0.898, F1: 0.625 | Lower performance than ensemble methods | ||

| Imbalanced Data [22] | Telecom churn (15% to 1% imbalance) | XGBoost + SMOTE | F1 score, ROC AUC | Consistently highest F1 score across imbalance levels |

| Random Forest + SMOTE | F1 score, ROC AUC | Poor performance under severe imbalance |

Technical Comparative Analysis

Table 2: Technical Characteristics of ML Algorithms for Chemical Data

| Characteristic | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Random Forest (RF) | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Maximum margin hyperplane with kernel tricks | Bootstrap aggregation of decorrelated trees | Gradient boosting with sequential error correction |

| Handling Spectral Non-linearity | Excellent via kernels (RBF, polynomial) | Good with multiple splits | Excellent with sequential learning |

| Feature Selection | Embedded in kernel | Native Gini importance | Built-in feature importance |

| Data Efficiency | Works well with small samples | Requires moderate samples | Best with larger datasets |

| Imbalanced Data | Sensitive without weighting | Moderate handling | Excellent with proper sampling |

| Training Speed | Slow for large datasets | Fast (parallelizable) | Fast (optimized implementation) |

| Interpretability | Moderate (support vectors) | High (feature importance) | Moderate (requires SHAP/XAI) |

| Hyperparameter Sensitivity | High (C, γ, kernel choice) | Low to moderate | Moderate (learning rate, depth) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for comparing ML algorithms on chemical data:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Bioactive Molecule Prediction Protocol

Following the experimental design in [19], the typical protocol for bioactive molecule prediction involves:

- Dataset Preparation: Seven carefully selected datasets known in literature for validating fingerprint-based molecule classification. Compounds are classified as active or inactive, with Tanimoto similarity calculated based on ECFC_4 across all pairs of molecules.

- Data Splitting: Division into training (70%) and validation (30%) sets while maintaining class distribution.

- Descriptor Calculation: Quantitative description of the compound's molecular structure using appropriate molecular descriptors.

- Model Training: Implementation of XGBoost using Classification and Regression Trees (CART) with regularization parameters (γ and λ) to control complexity and prevent overfitting. The training involves:

- For each descriptor, sort the numbers and scan for the best splitting point (lowest gain)

- Choose the descriptor with the best splitting point that optimizes the training objective

- Continue splitting until specified maximum tree depth is reached

- Assign prediction score to leaves and prune negative nodes

- Repeat steps in additive manner until specified number of rounds is reached

- Performance Comparison: Comparison against RF, SVM, Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFN), and Naïve Bayes using appropriate statistical measures.

Spectral Data Analysis with Feature Selection

Based on [21], the recursive feature elimination protocol for spectral data includes:

- Feature Importance Calculation: Compute Gini importance from Random Forest training on spectral data.

- Feature Ranking: Rank features according to importance measures.

- Feature Elimination: Remove the p% least important features.

- Classifier Training: Train classifiers (RF, D-PLS, D-PCR) on reduced feature set.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-4 until no features remain.

- Optimal Subset Identification: Identify the best feature subset according to test error.

This approach combines the best of both worlds: the superior feature relevance measurement of RF's Gini importance with the optimal classification performance of regularized methods on the identified feature subset [21].

Handling Imbalanced Chemical Data

For imbalanced scenarios common in chemical data (e.g., active vs. inactive compounds), [22] recommends:

- Imbalance Assessment: Calculate class distribution and imbalance ratio.

- Resampling Technique Selection: Apply SMOTE, ADASYN, or Gaussian Noise Upsampling (GNUS) to training data only.

- Model Training with Hyperparameter Tuning: Use Grid Search for hyperparameter optimization in imbalanced scenarios.

- Comprehensive Evaluation: Employ multiple metrics including F1 score, ROC AUC, PR AUC, Matthews Correlation Coefficient, and Cohen's Kappa.

- Statistical Validation: Perform Friedman test and Nemenyi post hoc comparisons to confirm statistical significance.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML in Chemical Data Analysis

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Data Sources | Spectral Databases (NIR, IR, Raman) | Provide raw spectral data for model training | Food authentication, pharmaceutical QC [1] |

| Chemical Structure Databases | Source of molecular structures and properties | Drug discovery, bioactivity prediction [19] | |

| Chemical Incident Databases | Historical safety data for predictive modeling | Accident prediction, risk assessment [20] | |

| Data Preprocessing | Scatter Correction Methods | Remove light scattering effects from spectra | Spectral calibration [1] |

| Normalization Algorithms | Standardize spectral intensities | Instrument variation compensation [1] | |

| Feature Selection Methods | Identify relevant variables | Gini importance, recursive elimination [21] | |

| ML Algorithms | SVM Implementations | Create maximum-margin classifiers | Nonlinear classification tasks [1] |

| Random Forest | Ensemble classification with feature importance | Robust spectral analysis [1] [21] | |

| XGBoost | High-accuracy gradient boosting | State-of-the-art predictive performance [1] [19] | |

| Evaluation Metrics | F1 Score | Balance precision and recall | Imbalanced data assessment [22] [20] |

| ROC AUC | Overall classification performance | Algorithm comparison [22] | |

| SHAP Analysis | Model interpretation and explanation | Feature contribution quantification [20] |

The comparative analysis of SVM, Random Forest, and XGBoost for chemical data reveals a complex performance landscape where each algorithm excels in specific scenarios. SVM provides strong performance with limited samples and nonlinear relationships via kernel tricks. Random Forest offers robust performance with built-in feature importance and resistance to overfitting. XGBoost frequently achieves state-of-the-art predictive accuracy, particularly with sufficient data and complex relationships.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, the development of explainable AI (XAI) techniques is crucial for interpreting complex models like XGBoost and building trust with researchers and regulatory bodies [18]. Second, multi-omics integration using AI to fuse data from genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics with conventional analytical data will enable more holistic chemical understanding [18]. Finally, standardization and validation frameworks for AI-based methods are needed for widespread adoption in industry and regulatory applications [18].

For practitioners, the choice among these algorithms should consider dataset size, dimensionality, noise characteristics, imbalance ratio, and interpretability requirements. Ensemble approaches combining these methods often provide superior performance, as demonstrated in chemical safety prediction [20]. As the field evolves, the integration of these machine learning foundations with emerging AI technologies will continue to transform chemical data analysis across research and industrial applications.

Spectral data, encompassing hyperspectral imagery, molecular spectra, and audio signals, provides a rich source of information across scientific disciplines. Traditional chemometric methods have long served as the foundation for analyzing this data. However, the emergence of deep learning architectures—Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Transformers—has revolutionized the field, enabling the automatic learning of complex, hierarchical features directly from raw spectral inputs. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these architectures, evaluating their performance, applicability, and implementation to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal methodologies for spectral analysis tasks.

The effectiveness of each deep learning architecture stems from its innate mechanism for processing sequential or spatial information.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) utilize layers of filters that convolve across input data, such as a spectrogram, to detect local patterns. This hierarchical structure allows CNNs to identify salient features like spectral peaks or absorption bands, making them exceptionally powerful for extracting spatially local features from spectral-spatial data cubes. Their architecture is inherently translation-invariant, meaning a feature learned at one spectral position can be recognized at another.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) variants, process sequential data step-by-step while maintaining an internal hidden state that acts as a memory of previous inputs. This makes them naturally suited for modeling spectral sequences where the order of wavelengths or frequencies carries meaningful information. LSTMs address the vanishing gradient problem in traditional RNNs through gating mechanisms, allowing them to capture long-range dependencies across the spectral range.

Transformer architectures rely on a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of all parts of the input sequence when processing each element. This global receptive field from the first layer enables the model to capture complex, long-range dependencies and interactions across the entire spectrum simultaneously. For example, it can directly model the relationship between distant spectral features that might be correlated.

Hybrid architectures that combine these paradigms are increasingly prevalent. For instance, CNNs can first extract local spectral-spatial features, the sequence of which is then processed by a Transformer encoder to model global contexts. Similarly, a novel Time-Frequency Recurrent (TFR) network integrates wavelet transformations directly into a recurrent architecture, allowing it to mine potential time-frequency properties naturally [23]. Its advanced version, CNN-TFR, further fuses convolutional layers to discover nearby correlations in time series in addition to time-frequency characteristics [23].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following tables summarize the performance of various architectures across distinct spectral analysis tasks, providing a basis for objective comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Phoneme Recognition Tasks (Audio Spectral Features)

| Model Architecture | Key Strengths | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer & Conformer | Superior with long-range accessibility through input frames [24] | Phoneme recognition on TIMIT dataset; analysis of receptive field length impact [24] |

| CNN (ContextNet) | Strong local feature extraction | Comparison under constrained parameter size and layer depth [24] |

| RNN | Effective for sequential temporal modeling | Performance analyzed when observable sequence length varies [24] |

Table 2: Performance on Hyperspectral Image (HSI) Classification

| Model Architecture | Overall Accuracy (OA) | Dataset | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral-Spatial Wave & Frequency Interactive Transformer | 98.49%, 98.60%, 99.07%, 98.29%, 97.97% [25] | Five benchmark HSI datasets [25] | Integrates frequency-aware and phase-aware token representations [25] |

| Standard Vision Transformer (ViT) | Lower than specialized model above | General HSI benchmarks | Relies on spatial and spectral attention alone |

Table 3: Performance on Molecular Property Prediction

| Model Architecture | Key Strengths | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| BT-MBO (Bidirectional Transformer + MBO) | High accuracy with scarcely labeled data (as low as 1% labeled) [26] | Ames mutagenicity, Tox21, etc.; Uses SMILES strings and self-supervised learning [26] |

| AE-MBO (Autoencoder + MBO) | Effective using unsupervised latent vectors as features [26] | Same molecular classification benchmarks [26] |

| ECFP-MBO (Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints + MBO) | Robust performance with traditional cheminformatics fingerprints [26] | Same molecular classification benchmarks [26] |

Table 4: Performance on Short-Term Wind Speed Prediction (Time-Series Spectral Data)

| Model Architecture | Key Strengths | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| CNN-TFR (Proposed) | Superior prediction performance and robustness [23] | Multi-step prediction using real wind speed data [23] |

| TFR (Time-Frequency Recurrent) | Better than LSTM/GRU at mining time-frequency properties [23] | Comparison against LSTM, GRU, and SFM [23] |

| LSTM/GRU | Standard for sequential data, but limited in mining frequency info [23] | Used as baseline models [23] |

Critical Analysis of Comparative Data

The data reveals a consistent trend: while CNNs and RNNs remain powerful, Transformer-based models or hybrids often achieve state-of-the-art results by leveraging self-attention for global context. The superior performance of the Spectral-Spatial Wave and Frequency Interactive Transformer in HSI classification [25] and the BT-MBO model in molecular prediction [26] underscores this. Furthermore, architectures specifically designed to exploit the frequency-domain characteristics of the data, such as TFR [23] and the frequency-domain Transformer encoder [25], demonstrate significant gains over models that operate solely in the original input space.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementation, this section outlines key experimental methodologies cited in the comparison.

Protocol 1: Hyperspectral Image Classification with a Frequency Interactive Transformer

This protocol is based on the model proposed by Scientific Reports [25].

1. Research Objective: To achieve state-of-the-art classification of Hyperspectral Images (HSI) by explicitly integrating frequency-domain and phase-aware features into a Transformer framework.

2. Materials and Data Preparation:

- Datasets: Standard HSI benchmarks (e.g., Indian Pines, Pavia University).

- Preprocessing: Normalize spectral bands. Partition image into small, overlapping 3D patches (e.g., 9x9 pixels x all spectral bands) centered on each pixel.

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1 - Shallow Feature Extraction: A backbone CNN with 3D and 2D convolutional layers extracts initial spectral-spatial features from the HSI patches.

- Step 2 - Frequency Domain Transformer Encoder: The shallow features are passed to a novel encoder with two parallel branches:

- Spectral-Spatial Frequency Generator: Applies multiscale frequency transformations (e.g., Discrete Wavelet Transform or Fast Fourier Transform) to generate frequency-domain tokens.

- Spectral-Spatial Wave Generator: Encodes phase and amplitude information as complex-valued wave tokens.

- Step 3 - Spectral-Spatial Interaction Module: Features from the frequency and wave branches are interactively fused using cross-attention mechanisms.

- Step 4 - Classification Head: The fused, refined features are passed through a fully connected layer and a softmax activation to generate the final class prediction.

4. Outcome Measurement: The primary metric is Overall Accuracy (OA), which is the percentage of correctly classified test pixels. Average Accuracy (AA) and Cohen's Kappa coefficient are standard secondary metrics.

Protocol 2: Molecular Property Prediction with Scarce Labels

This protocol is derived from the work on integrating Transformer and Autoencoder techniques with spectral graph algorithms [26].

1. Research Objective: To accurately predict molecular properties (e.g., toxicity, solubility) using very low amounts of labeled data (as little as 1%).

2. Materials and Data Preparation:

- Datasets: Molecular datasets such as Ames (mutagenicity), Tox21, etc., with Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) string representation.

- Preprocessing: For the BT-MBO model, SMILES strings are tokenized. For the ECFP-MBO model, Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) of a specified radius are generated using the RDKit library.

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1 - Fingerprint Generation:

- BT-MBO Path: A Bidirectional Encoder Transformer, pre-trained via self-supervised learning on a large corpus of unlabeled molecules, converts SMILES strings into latent vectors (BT-FPs).

- AE-MBO Path: An Autoencoder (encoder-decoder) is trained to reconstruct SMILES strings, and the encoder is used to generate latent vectors (AE-FPs).

- ECFP-MBO Path: Traditional ECFPs are generated directly.

- Step 2 - Graph-Based Semi-Supervised Learning: The generated fingerprints (features) and the small set of available labels are input into the Merriman-Bence-Osher (MBO) scheme. The MBO algorithm propagates label information on a graph built from the molecular feature vectors to predict the labels of all unlabeled molecules.

- Step 3 - Consensus Model: Predictions from the AE-MBO, BT-MBO, and ECFP-MBO models can be aggregated into a final consensus prediction for improved robustness.

4. Outcome Measurement: For classification tasks, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) and Accuracy are reported. Performance is evaluated across multiple random splits with varying low label rates (1%, 5%, 10%).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key computational tools and data resources essential for conducting advanced spectral analysis with deep learning.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Benchmark Datasets | Public datasets (e.g., Indian Pines, Pavia Univ.) for training and fair model comparison. | Validating HSI classification models [25]. |

| Molecular Datasets (Ames, Tox21) | Curated data linking molecular structure to properties for predictive model training. | Benchmarking molecular property prediction [26]. |

| RDKit Library | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for generating molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP). | Creating input features for models like ECFP-MBO [26]. |

| Wavelet Transform Toolbox | Software library (e.g., PyWavelets) for decomposing signals into time-frequency components. | Implementing TFR networks for frequency feature mining [23]. |

| Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) | A feature extraction method to convert audio signals into spectrogram-like representations. | Preprocessing audio for CNN-based sound classification [27]. |

| The Unscrambler X | Commercial software for multivariate statistical analysis of spectral data (PCA, PLSR, MCR). | Traditional chemometric analysis and spectral pretreatment [28]. |

| Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) | Fundamental algorithm for converting signals from time/space to frequency domain. | Generating spectrograms from raw audio signals [29]. |

In the fields of analytical chemistry and drug development, spectral data serves as a fundamental source of information for understanding the chemical and physical properties of substances. Spectroscopy, which studies the absorption, emission, and scattering of electromagnetic radiation by electrons or molecules, generates data in the form of spectra—graphs showing the intensity of radiation or response to radiation at different wavelengths [30]. This data forms the critical foundation for chemometric analysis, where mathematical and statistical methods are applied to extract meaningful chemical information [1]. The structural nature of this spectral data—whether structured, unstructured, or semi-structured—profoundly influences the selection of analytical algorithms, processing methodologies, and ultimately, the reliability of research conclusions in pharmaceutical development and other scientific domains.

The classification of spectral data into structured and unstructured forms represents a crucial paradigm for researchers selecting appropriate analytical pathways. As modern spectroscopic techniques generate increasingly complex datasets, understanding this data taxonomy enables scientists to harness the full potential of both classical chemometric methods and emerging artificial intelligence (AI) approaches [1]. This comparative guide examines the fundamental characteristics, analytical treatments, and practical applications of structured versus unstructured spectral data within the context of chemometric algorithm research, providing scientists with a framework for optimizing their analytical strategies.

Defining Structured and Unstructured Spectral Data

Structured Spectral Data

Structured spectral data is highly organized information that fits into predefined models or templates, typically represented in tabular formats with rows and columns [31] [32]. This data type follows a consistent schema or blueprint, making it systematically addressable and easily processable by traditional computational methods [31]. In spectroscopic applications, structured data emerges from standardized experimental protocols where measurement parameters, wavelength intervals, and intensity values are systematically recorded according to predetermined formats.

Common examples of structured spectral data include:

- Spectral intensity matrices with fixed wavelength columns and sample rows

- Chemical databases containing curated spectral libraries with standardized metadata

- Multivariate calibration sets with precisely defined X (spectral) and Y (concentration) variables

- Process analytical technology (PAT) data from in-line sensors with regular time intervals

The primary advantage of structured spectral data lies in its computational efficiency. The organized nature allows for rapid access, retrieval, and analysis using standard statistical packages and relational database management systems (RDBMS) [31] [32]. For spectroscopic calibration and quantification, this structured format enables direct application of classical chemometric techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression without extensive data preprocessing [1].

Unstructured Spectral Data

Unstructured spectral data lacks a predefined organizational model or schema, presenting in formats that do not conform to traditional row-column databases [33] [34]. This data type encompasses diverse forms of information that may vary in format, scale, and organization, requiring advanced processing techniques to extract meaningful patterns. In modern spectroscopy, unstructured data frequently originates from emerging analytical technologies and complex measurement scenarios.

Examples of unstructured spectral data in scientific research include:

- Hyperspectral imaging data cubes with spatial and spectral dimensions

- Raw instrument outputs with variable resolution and metadata formats

- Spectral-temporal datasets from dynamic processes with irregular sampling

- Fused multi-technique analytical results (e.g., Raman-IR combined data)

- Spectral data embedded in scientific publications and technical reports

The primary challenge with unstructured spectral data stems from its inherent complexity and lack of standardization [33]. However, this data type often contains rich, nuanced information that may be lost when forcing data into structured formats [31]. The proliferation of advanced spectroscopic techniques has significantly increased the proportion and importance of unstructured data in chemometric research, necessitating specialized analytical approaches [1].

Semi-Structured Spectral Data

Semi-structured spectral data represents an intermediate category incorporating elements of both structured and unstructured data [31] [32]. While not conforming to the rigid schema of traditional databases, it contains organizational markers such as tags, metadata, or hierarchical structures that facilitate processing and analysis. This data type offers greater flexibility than structured formats while maintaining more organization than completely unstructured data.

Common manifestations of semi-structured spectral data include:

- JSON or XML-formatted spectral data with embedded metadata

- Instrument-specific data formats with header information and measurement parameters

- Spectral databases with tagged features but variable structures

- Research data repositories with flexible schema requirements

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Spectral Data Types

| Characteristic | Structured Spectral Data | Unstructured Spectral Data | Semi-Structured Spectral Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schema | Fixed, predefined schema [32] | No predefined schema [33] | Flexible schema with tags [31] |

| Storage Format | RDBMS, SQL databases [31] | Data lakes, file systems [31] | NoSQL databases, JSON, XML [31] [32] |

| Scalability | Requires schema modifications [31] | Highly scalable without restructuring [31] | Moderately scalable with some organization [32] |

| Analysis Complexity | Low - Direct analysis with SQL, PLS, PCA [31] [1] | High - Requires specialized AI/ML tools [31] [1] | Medium - Can use some traditional tools with adaptations [31] |

| Data Integrity | High consistency and accuracy [31] | Variable quality, requires validation [33] | Moderate consistency with proper tagging [31] |

| Common Spectral Examples | Spectral intensity matrices, calibration sets | Hyperspectral images, raw instrument outputs | JSON spectral data, instrument formats with metadata |

Comparative Analysis: Structural Implications for Spectral Analysis

The structural nature of spectral data directly influences the selection and performance of chemometric algorithms. Understanding these implications enables researchers to match their analytical approaches to their data characteristics, optimizing research outcomes and resource allocation.

Analytical Workflow Implications

Structured spectral data typically follows straightforward analytical workflows characterized by standardized preprocessing, feature extraction, and model building sequences. The predictable organization allows for direct application of classical chemometric methods including PCA, PLS, and multiple linear regression (MLR) [1]. These methods leverage the tabular nature of structured data to establish quantitative relationships between spectral features and chemical properties through well-defined mathematical operations.

In contrast, unstructured spectral data requires more complex preprocessing pipelines involving data transformation, feature engineering, and dimensionality reduction before core analysis can commence. The analytical workflow must accommodate variable formats, scales, and resolutions through techniques such as wavelet transforms, convolutional autoencoders, or customized data parsing algorithms [5] [1]. These additional steps increase computational demands but may reveal patterns inaccessible through structured data approaches.

Semi-structured data occupies an intermediate position, where metadata and tags can guide preprocessing decisions, potentially automating aspects of data organization while preserving flexibility. Tools capable of parsing JSON, XML, or specific instrument formats can extract structured components while handling variable elements through adaptable algorithms [31].

Algorithm Performance and Suitability

The performance of chemometric algorithms varies significantly between structured and unstructured spectral data contexts. Traditional linear models excel with structured data where assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and predictor independence are more likely to be satisfied [1]. Methods like PLS regression demonstrate high performance for quantitative analysis when applied to structured spectral matrices, particularly for well-characterized chemical systems with limited nonlinearities [5].

With unstructured data, machine learning and deep learning approaches typically outperform traditional chemometric methods. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can automatically extract relevant features from raw spectral data without manual feature engineering [5] [1]. Studies comparing modeling approaches have found that while interval PLS (iPLS) variants perform well for structured regression problems with limited data, CNNs show superior performance for complex classification tasks with larger datasets [5]. This performance advantage comes at the cost of interpretability, as deep learning models function as "black boxes" compared to transparent linear models.

Table 2: Algorithm Performance Across Spectral Data Types

| Algorithm Type | Structured Data Performance | Unstructured Data Performance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLS Regression | Excellent - Primary choice for quantitative analysis [1] | Poor - Requires structured input | Limited by linearity assumptions; ideal for calibration models |

| PCA | Excellent - Effective dimensionality reduction [1] | Moderate - Requires data flattening | Loss of spatial relationships in unstructured data |

| Decision Trees/Random Forest | Good - Interpretable results [1] | Good - Handles complex relationships | Feature importance rankings; robust to noise [1] |

| CNN | Moderate - Overkill for simple structured data | Excellent - Automated feature extraction [5] [1] | Requires large datasets; computationally intensive |

| SVM | Good - Effective for classification [1] | Good - Kernel tricks handle complexity | Parameter tuning critical; performs well with limited samples [1] |

Data Management and Storage Considerations

Structured spectral data management leverages mature database technologies with efficient compression, indexing, and query capabilities. The predictable organization enables optimized storage schemes and rapid retrieval of specific spectral regions or samples [31] [32]. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of flexibility, as schema modifications require significant effort and potential data migration [31].

Unstructured spectral data demands storage solutions capable of accommodating diverse formats and volumes without predefined schema. Data lakes, cloud object storage, and specialized file systems provide the necessary flexibility but may sacrifice query performance and storage efficiency [31] [34]. The resource-intensive nature of unstructured data management contributes to significantly higher total cost of ownership, including storage, processing, and specialized personnel requirements [33] [34].

Semi-structured approaches offer a compromise, providing some organizational benefits through metadata indexing while maintaining flexibility. Technologies such as NoSQL databases efficiently handle semi-structured spectral data, enabling query capabilities based on tags or metadata without rigid schema constraints [31] [32].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

Protocol 1: Structured Data Analysis with PLS Regression

Objective: To develop a quantitative calibration model for analyte concentration prediction using structured spectral data.

Materials and Methods:

- Spectral Data: Beer dataset (40 training samples) with defined wavelength intensities and reference values [5]

- Pre-processing: Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) transformation to reduce scattering effects

- Model Development: Implement Partial Least Squares Regression with leave-one-out cross-validation

- Validation: Assess model performance using root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSECV) and coefficient of determination (R²)

Key Steps:

- Organize spectral data into a matrix format (samples × wavelengths)

- Apply pre-processing to address baseline offset and multiplicative effects

- Split data into calibration and validation sets using Kennard-Stone algorithm

- Determine optimal number of latent variables through cross-validation

- Build PLS model and evaluate prediction performance on validation set

Expected Outcomes: A linear calibration model with defined regression coefficients, enabling concentration prediction from new spectral measurements.

Protocol 2: Unstructured Data Analysis with Convolutional Neural Networks

Objective: To classify waste lubricant oils based on unstructured spectral data using deep learning.

Materials and Methods:

- Spectral Data: Waste lubricant oil dataset (273 training samples) with complex spectral features [5]

- Pre-processing: Apply wavelet transforms for feature enhancement while maintaining interpretability [5]

- Model Architecture: Implement 1D convolutional neural network with three convolutional layers

- Training: Use Adam optimizer with categorical cross-entropy loss function

Key Steps:

- Preprocess raw spectra using continuous wavelet transform (CWT)

- Structure data into appropriate tensor format for CNN input

- Design network architecture with convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers

- Implement regularization techniques (dropout, batch normalization) to prevent overfitting

- Train model with validation monitoring and early stopping

Expected Outcomes: A trained CNN model capable of classifying oil types with accuracy exceeding traditional methods, particularly with larger datasets.

Protocol 3: Hybrid Approach with iPLS and Wavelet Transforms

Objective: To compare the performance of interval PLS (iPLS) with classical and wavelet-based pre-processing.

Materials and Methods:

- Spectral Data: Both beer and waste lubricant oil datasets for direct comparison [5]

- Pre-processing: Compare classical methods (SNV, derivatives) with wavelet transforms [5]

- Model Development: Implement iPLS with 20 intervals and variable selection

- Evaluation: Compare root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) across approaches

Key Steps:

- Apply multiple pre-processing techniques to identical datasets

- Implement iPLS with systematic interval selection

- Compare wavelet-based feature extraction with traditional pre-processing

- Evaluate model interpretability through regression coefficient analysis

Expected Outcomes: Demonstration that wavelet transforms improve performance for both linear and CNN models while maintaining interpretability, with no single combination universally optimal [5].

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the contrasting workflows for analyzing structured versus unstructured spectral data, highlighting the critical decision points and methodological differences.

Structured Data Analysis Pathway: This linear workflow demonstrates the straightforward processing of structured spectral data, from standardized preprocessing through model validation and chemical interpretation.

Unstructured Data Analysis Pathway: This workflow illustrates the iterative, complex processing required for unstructured spectral data, emphasizing automated feature learning and pattern discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Spectral Data Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SciFinder-n | Access experimental spectral data for reference comparison [30] | Compound identification and verification across data types |

| NIST Chemistry WebBook | Reference database for IR, Mass Spec, and UV/Vis spectra [30] | Structured data benchmarking and method validation |

| Wavelet Transform Toolboxes | Mathematical transformation for feature enhancement [5] | Pre-processing for both structured and unstructured data analysis |

| PLS Toolboxes | Implementation of Partial Least Squares regression [1] | Primary analysis method for structured spectral data |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks for complex model development [34] | CNN and DNN implementation for unstructured data |

| Python/R Chemometrics Packages | Specialized libraries for spectroscopic analysis [1] | Flexible analysis across data types, from PCA to machine learning |

| NoSQL Databases | Storage solutions for semi-structured and unstructured data [31] [32] | Managing diverse spectral data formats with metadata preservation |

The comparative analysis of structured versus unstructured spectral data reveals a landscape where data structure fundamentally dictates analytical strategy. Structured data, with its predefined organization, enables efficient application of classical chemometric methods like PLS regression, delivering interpretable results with computational efficiency—particularly valuable in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development where model transparency is essential [1].

Conversely, unstructured spectral data, while demanding advanced processing and substantial computational resources, offers access to richer, more complex chemical information through AI and machine learning approaches [5] [1]. The emerging paradigm in chemometric research leverages the strengths of both approaches, often through hybrid strategies that apply appropriate algorithms to different data types or structural layers within the same dataset.

Future directions in spectral data analysis point toward increased integration of AI with traditional chemometrics, development of more interpretable deep learning models, and standardized approaches for handling semi-structured data [1]. As spectroscopic technologies continue to evolve, generating increasingly complex datasets, the fundamental understanding of data structure principles will remain essential for researchers selecting optimal analytical pathways in drug development and chemical research.

Algorithm Implementation and Biomedical Applications: From Spectroscopy to Drug Discovery

In the realm of modern analytical science, vibrational spectroscopic techniques—Near-Infrared (NIR), Infrared (IR), and Raman spectroscopy—have become indispensable tools for molecular characterization across pharmaceutical, chemical, and biological disciplines. These techniques provide non-destructive, rapid analysis of chemical composition and physical properties. However, the raw spectral data generated by these instruments requires sophisticated processing to extract meaningful chemical information. The efficacy of this data extraction hinges critically on the application of tailored chemometric workflows that account for the unique physical principles and analytical challenges inherent to each spectroscopic method. Within the broader context of comparative chemometric algorithm research, this guide systematically examines the distinct data processing pathways for NIR, IR, and Raman spectroscopy, providing researchers with experimentally-validated performance comparisons and detailed methodological protocols to inform analytical development.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

The interaction between light and matter differs fundamentally across NIR, IR, and Raman spectroscopy, directly influencing their respective data processing requirements. IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light as molecules undergo vibrational transitions, requiring direct dipole moment changes. NIR spectroscopy probes overtone and combination bands of fundamental molecular vibrations, primarily involving C-H, N-H, and O-H bonds. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy relies on inelastic scattering of light, detecting the energy shift as photons interact with molecular vibrations and rotations; this process requires a change in polarizability rather than a permanent dipole moment [35] [36].

These fundamental differences create distinct spectral profiles and analytical challenges. IR and NIR spectra typically exhibit broad absorption bands, while Raman spectra display sharp, well-resolved peaks. A critical practical consideration is water interference: Raman spectroscopy experiences minimal interference from aqueous environments, allowing direct analysis of biological samples and process streams, whereas IR and NIR spectroscopy often require specialized sampling techniques to overcome strong water absorption [36]. Furthermore, Raman spectra are frequently contaminated by fluorescence background, which can be orders of magnitude more intense than the Raman signal itself, necessitating robust baseline correction protocols [37].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques

| Characteristic | NIR Spectroscopy | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Absorption of overtone and combination vibrations | Absorption of fundamental vibrations | Inelastic scattering of light |

| Spectral Range | 4000-10000 cm⁻¹ [38] | 400-4000 cm⁻¹ | 200-3200 cm⁻¹ [38] |

| Water Interference | High | High | Low [36] |

| Dominant Spectral Features | Broad, overlapping bands | Sharp to broad absorption bands | Sharp, well-resolved peaks |

| Primary Preprocessing Needs | Scatter correction, derivative spectra | Atmospheric correction, baseline correction | Fluorescence removal, spike elimination [35] [37] |

Experimental Workflows and Data Processing Pathways

Sample Preparation and Spectral Acquisition

Experimental design begins with appropriate sample presentation. For NIR spectroscopy, reflectance measurements are common for solids and pastes, while transflection probes suit liquid monitoring [39]. Raman spectroscopy requires careful consideration of laser wavelength (commonly 785 nm for biological samples to minimize fluorescence) and power settings [37]. Sample degradation must be monitored, particularly with higher-energy lasers. IR spectroscopy typically employs transmission cells with controlled pathlengths for liquids or attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessories requiring minimal preparation.

Quality control during acquisition is especially critical for Raman measurements. Cosmic rays striking the detector create sharp, intense spikes that must be identified and removed. Effective algorithms detect these anomalies by comparing successive spectra or screening for abnormal intensity changes along the wavenumber axis [35]. Simultaneous acquisition of multiple spectra enables robust spike correction through interpolation or replacement with successive measurements.

Spectral Preprocessing Workflows

Preprocessing transforms raw instrumental data into analytically useful spectra by removing physical artifacts and enhancing chemical information.

Raman-specific processing requires specialized fluorescence baseline correction. Techniques include asymmetric least squares smoothing, polynomial fitting, and morphological algorithms like BubbleFill, which has demonstrated superior performance for complex baseline shapes compared to established methods [37]. The following workflow diagram outlines the comprehensive preprocessing steps for Raman spectral data:

NIR preprocessing typically addresses light scattering effects from particulate matter. Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) and Standard Normal Variate (SNV) transformation effectively normalize these effects. Derivative preprocessing (first or second derivative) enhances resolution of overlapping bands and removes baseline offsets [40].

IR preprocessing shares similarities with both techniques, often requiring atmospheric compensation (for CO₂ and water vapor) and advanced baseline correction, particularly for ATR measurements where contact variability affects spectra.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Used Cooking Oil Analysis

| Analytical Technique | Parameter | Performance Metric | Value | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | Acid Value | R² | >0.98 | Titration [38] |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Kinematic Viscosity | R² | >0.97 | Viscometry [38] |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Density | R² | >0.96 | Pycnometry [38] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Acid Value | R² | ~0.90 | Titration [38] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Kinematic Viscosity | R² | ~0.89 | Viscometry [38] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Density | R² | ~0.87 | Pycnometry [38] |

Chemometric Modeling and Validation

Following preprocessing, chemometric modeling correlates spectral features with chemical or physical properties. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression represents the most widely employed algorithm for quantitative analysis across all three techniques, particularly effective for modeling correlated spectral variables [38] [39].

Model validation follows strict protocols to ensure robustness. Data splitting reserves 25% of samples as an independent validation set, while cross-validation techniques assess model stability [40]. Critical performance metrics include Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) for regression models and accuracy/selectivity for classification tasks [35]. For Raman spectroscopy, particular attention must be paid to model transfer between instruments, which may require standardization protocols to address instrumental variations [35].