Combating Chemical Interference in UV-Vis Analysis: Strategies for Accurate Quantification in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and overcoming chemical interference in Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy.

Combating Chemical Interference in UV-Vis Analysis: Strategies for Accurate Quantification in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, troubleshooting, and overcoming chemical interference in Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details the origins of interference from both chemical and physical sources, including reactive compound classes and environmental factors. The content explores robust methodological corrections, from simple spectral techniques to advanced chemometric models and data fusion. A strong emphasis is placed on validation protocols and comparative method analysis, offering a clear framework for selecting the optimal quantification strategy to ensure data integrity in pharmaceutical analysis and biomolecular characterization.

Understanding the Enemy: A Deep Dive into the Sources and Mechanisms of Chemical Interference

Core Definitions and Mechanisms

What is the fundamental difference between chemical and physical interference?

The fundamental difference lies in whether the interference involves a change in the sample's chemical composition.

Chemical Interference occurs when interfering species interact with the analyte through chemical reactions or processes that alter the chemical environment or the nature of the analyte itself. This includes the formation of stable compounds, changes in ionization equilibrium, or molecular interactions that modify absorption characteristics [1] [2]. For example, in spectroscopy, chemical interference can happen when an analyte is not completely atomized due to the formation of thermally stable compounds [2].

Physical Interference affects the measurement through changes in the physical properties of the sample matrix without altering the chemical composition of the analyte. These include variations in viscosity, surface tension, dissolved solids content, or temperature, which influence transport processes like nebulization efficiency or light scattering [1] [3] [2]. A common example is the scattering of light caused by suspended solid impurities in a sample [3].

Table: Comparison of Interference Types in Analytical Chemistry

| Feature | Chemical Interference | Physical Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Alteration of chemical state or environment [2] | Change in physical sample properties [1] [2] |

| Effect on Analyte | Prevents atomization/excitation via compound formation; shifts ionization equilibrium [1] [2] | Alters transport to instrument (e.g., nebulization) or causes light scattering [1] [3] |

| Common Examples | Formation of stable phosphate/ sulfate compounds with Ca/Mg; EIE effects [1] [2] | Differences in viscosity, surface tension, dissolved solids; scattering from particulates [1] [3] [2] |

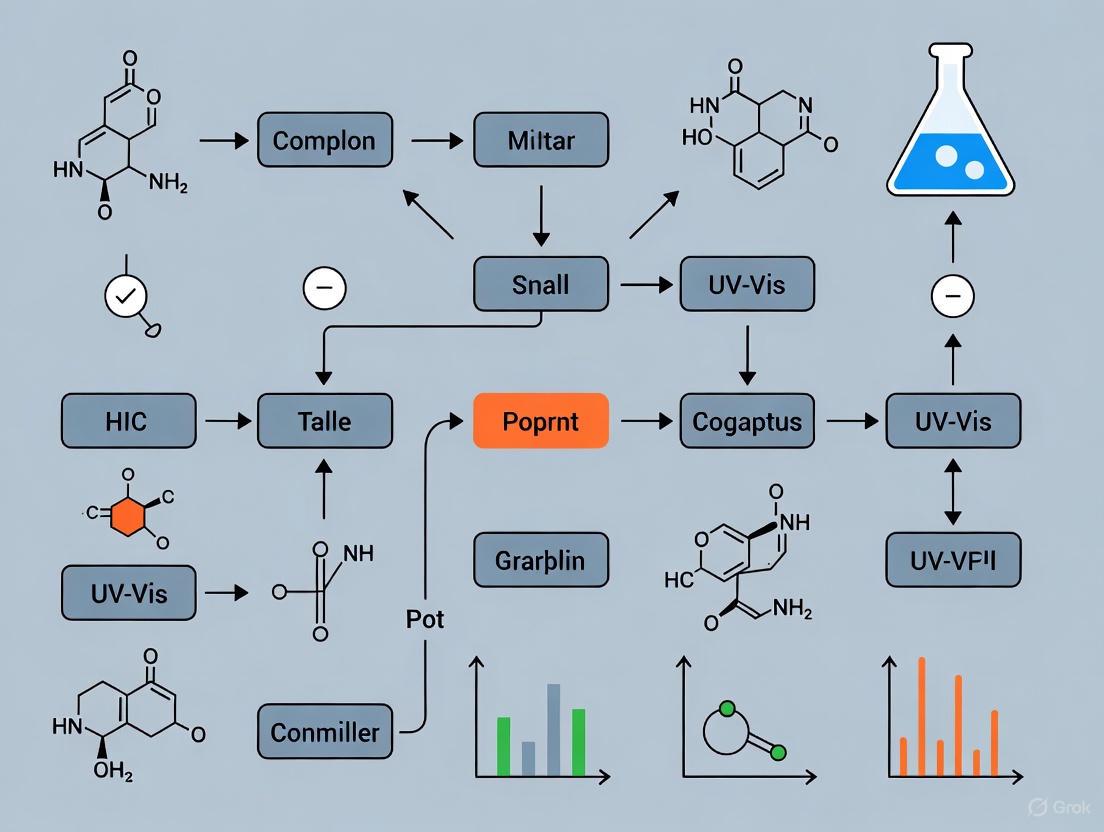

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for diagnosing the primary type of interference in an analytical measurement.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can the method of standard addition correct for all types of interference? A: No. Standard addition is primarily effective for compensating for physical interference (matrix effects) where the sample and standard behave differently due to physical properties [2]. It generally cannot correct for spectral interference, background absorption, or specific chemical interferences like ionization or compound formation. For these, specific chemical modifiers or instrumental corrections are required [2].

Q2: Why are my UV-Vis absorbance readings unstable or non-linear at high values? A: Absorbance readings above 1.0 to 1.5 AU often become non-linear and unstable due to instrumental limitations, primarily stray light [4] [5]. As absorbance increases, the amount of light reaching the detector diminishes, and any stray light (light of unintended wavelengths) becomes a significant portion of the signal, causing deviations from the Beer-Lambert law [4]. The solution is to ensure measurements are taken within the instrument's linear range, typically by diluting the sample or using a shorter path length cuvette [6] [4].

Q3: How can I identify if an interference is spectral or chemical in nature? A: Performing a background correction test is a key diagnostic step. If the apparent concentration of the analyte changes significantly after applying background correction (e.g., using a deuterium lamp), it indicates significant spectral interference or background absorption [2]. If the problem persists, it is likely a non-spectral, chemical, or physical interference. Observing the signal response to the addition of a releasing or protective agent can confirm chemical interference [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common UV-Vis Issues and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common UV-Vis Spectroscopy Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Type of Interference | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected peaks or high background | Spectral / Physical (Scattering) | Centrifuge or filter sample to remove particulates [3]; Use a blank with matching matrix [2]. |

| Non-linear calibration curve at high absorbance | Instrumental (Stray Light) | Dilute sample to bring absorbance below 1.0 AU [6]; Use a cuvette with shorter path length [7]. |

| Analyte signal is depressed in complex matrix | Chemical (Compound Formation) | Use a hotter flame or furnace; Add a releasing agent (e.g., La, Sr) or protective agent (e.g., EDTA) [2]. |

| Signal fluctuation; imprecise readings | Physical (Matrix Differences) | Match viscosity and solvent between standards and samples [2]; Allow all solutions to reach room temperature before measurement [2]. |

| Depressed signal for group I/II elements in hot flame | Chemical (Ionization) | Add an ionization suppressant (e.g., 0.1% KCl solution) to all standards and samples [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Verification and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Investigating and Correcting for Chemical Interference

This protocol is designed to diagnose and mitigate chemical interferences caused by compound formation.

1. Principle: Chemical interferences, such as the depression of calcium absorbance in the presence of phosphate or sulfate, occur due to the formation of thermally stable compounds that resist dissociation in the instrument source. This protocol uses a releasing agent (Lanthanum) to preferentially bind the interferent, freeing the analyte [2].

2. Materials:

- Analyte Stock Solution (e.g., 1000 ppm Calcium)

- Interferent Stock Solution (e.g., 1000 ppm Phosphate)

- Releasing Agent (e.g., 5% w/v Lanthanum solution, as LaCl~3~)

- Diluent (Deionized water)

- Volumetric flasks, pipettes, and standard laboratory glassware.

3. Procedure: 1. Prepare a series of five 50 mL volumetric flasks. 2. To all flasks, add a fixed, moderate amount of the analyte (e.g., 5 mL of 100 ppm Ca standard). 3. To flasks 2-5, add increasing amounts of the interferent (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8 mL of 100 ppm PO~4~3-~). 4. Add a sufficient quantity of the releasing agent (e.g., 5 mL of 5% La solution) to flasks 1, 3, and 5. 5. Dilute all solutions to the mark with deionized water. 6. Measure the absorbance signal for the analyte in each solution.

4. Data Interpretation:

- Compare the signal of solutions with and without the interferent (e.g., Flask 1 vs. Flask 2) to confirm signal depression.

- Compare the signal of solutions with the interferent but with and without the releasing agent (e.g., Flask 2 vs. Flask 3) to confirm the interference is chemical and that the releasing agent is effective.

- The expected results are visualized below.

Protocol 2: Verifying and Correcting for Stray Light Effects in UV-Vis

This protocol verifies if high absorbance non-linearity is due to instrumental stray light.

1. Principle: Stray light causes deviations from the Beer-Lambert law at high absorbances, limiting the useful dynamic range of an instrument. This test determines the maximum absorbance value for which the instrument provides linear response [4].

2. Materials:

- A stable, pure absorbing substance with a broad peak in the UV or Vis region (e.g., potassium dichromate in perchloric acid is a known standard).

- Appropriate volumetric glassware.

- Matched quartz cuvettes.

3. Procedure: 1. Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the standard. Precisely prepare a series of 5-6 dilutions covering a wide concentration range, aiming to have the most concentrated solution produce an absorbance >2 AU. 2. Using the appropriate solvent as a blank, calibrate the spectrophotometer. 3. Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the wavelength of maximum absorption. 4. Plot the measured Absorbance (y-axis) against the known Concentration (x-axis).

4. Data Interpretation:

- The plot should be a straight line. Observe the point where the data consistently deviates negatively from linearity.

- The absorbance value where a >2% deviation from linearity occurs is often considered the practical upper limit for quantitative work for that instrument and method [4].

- For all quantitative analyses, sample concentrations should be adjusted (via dilution) to ensure absorbance readings fall within this verified linear range.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents used to prevent or mitigate chemical interferences in spectroscopic analysis.

Table: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Chemical Interferences

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Common Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lanthanum Salts (LaCl~3~) | Releasing Agent: Preferentially reacts with interfering anions (e.g., PO~4~3-~, SO~4~2-~) to form stable compounds, preventing them from reacting with the analyte [2]. | Prevents phosphate interference in the determination of Calcium or Magnesium [2]. |

| Cesium Salts (CsCl) | Ionization Suppressant: Provides a high concentration of easily ionized atoms, flooding the plasma or flame with electrons. This suppresses the ionization of the analyte, shifting equilibrium back to the neutral ground state atoms [1] [2]. | Added (e.g., 0.1-0.2%) to samples and standards to determine Potassium or Barium in a hot flame or plasma [2]. |

| EDTA / 8-Hydroxyquinoline | Protective Agent: Forms stable, but volatile chelates with the analyte, shielding it from reactions with the interferent in the matrix until it reaches the hot region of the source [2]. | Protects Calcium from phosphate or aluminum interference by forming a volatile Ca-EDTA complex [2]. |

| Potassium Dichromate | Reference Material / Stray Light Test: A stable, well-characterized substance used to verify photometric accuracy and test for stray light limitations in UV-Vis spectrophotometers [8] [4]. | Preparing calibration standards for verifying adherence to the Beer-Lambert law and instrumental linearity [8]. |

This technical support center resource addresses the critical challenge of chemical interference in UV-Vis sample analysis research. Assay artifacts caused by problematic compounds can lead to false positives, wasted resources, and incorrect conclusions in drug discovery and analytical chemistry. The following guides and FAQs provide practical solutions for identifying, troubleshooting, and mitigating these issues in experimental workflows.

FAQs: Understanding Chemical Interference

What are PAINS and why are they problematic in screening assays?

Pan-Assay INterference compounds (PAINS) are chemical structures that frequently produce false-positive results in high-throughput screening (HTS) assays due to their non-specific reactivity rather than targeted biological activity [9]. Originally developed to identify compounds with "pan-assay" activity across multiple screening platforms, PAINS filters contain 480 substructural alerts associated with various interference mechanisms [9]. However, recent research indicates these filters are oversensitive and disproportionately flag compounds as interferents while failing to identify many truly interfering compounds [9]. More reliable quantitative structure-interference relationship (QSIR) models have now been developed that show 58-78% external balanced accuracy compared to traditional PAINS filters [9].

What are the main mechanisms by which compounds interfere with UV-Vis assays?

Chemical interference in UV-Vis analysis occurs through several distinct mechanisms:

- Chemical Reactivity: Compounds with electrophilic functional groups can chemically modify assay reagents or target biomolecules [10]. Common reactions include Michael additions, nucleophilic aromatic substitution, and disulfide formation [10].

- Spectroscopic Interference: Colored compounds absorb light in the UV-Vis range, while fluorescent compounds emit light, both interfering with detection [11]. Turbidity from compound aggregation causes light scattering, leading to inaccurate absorbance measurements [12].

- Luciferase Interference: Certain compounds inhibit luciferase reporter enzymes, producing false results in reporter gene assays [9].

- Aggregation: Compounds forming colloidal aggregates nonspecifically perturb biomolecules in biochemical and cell-based assays [9].

How can I distinguish true biological activity from assay interference?

Use orthogonal assay approaches with different detection technologies to confirm activity [10]. Compounds showing activity only under specific assay conditions (e.g., luciferase-based systems) but not in alternative formats likely represent interference artifacts [9] [11]. Additionally, structure-activity relationships (SAR) that don't follow expected trends may indicate interference, as true bioactive compounds typically show rational SAR [10].

Are there computational tools to predict assay interference before experimentation?

Yes, several computational resources are available:

- Liability Predictor: A free webtool that predicts HTS artifacts using QSIR models for thiol reactivity, redox activity, and luciferase interference [9].

- InterPred: A web-based tool that predicts the likelihood of luciferase inhibition and autofluorescence interference with ~80% accuracy [11].

- SCAM Detective: Predicts colloidal aggregators, the most common source of false positives in HTS campaigns [9].

Table 1: Prevalence of Different Interference Types in Screening Libraries

| Interference Type | Prevalence in Screening Libraries | Common Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Inhibition | 9.9% of Tox21 library compounds [11] | Variable, identified by machine learning models [11] |

| Autofluorescence (Blue) | 7.7% of Tox21 library compounds [11] | Conjugated systems, specific fluorophores |

| Autofluorescence (Green) | 5.0% of Tox21 library compounds [11] | Conjugated systems, specific fluorophores |

| Autofluorescence (Red) | 0.5% of Tox21 library compounds [11] | Extended conjugated systems |

| Thiol Reactivity | Variable across libraries | Michael acceptors, alkyl halides, epoxides [10] |

| Redox Activity | Variable across libraries | Quinones, polyphenolics [9] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent absorbance readings in UV-Vis measurements

Solution: This may indicate compound aggregation or precipitation. First, check compound solubility in assay buffer using dynamic light scattering or nephelometry [10]. Reduce compound concentration if possible, as aggregation is concentration-dependent [9]. Add mild detergents like Triton X-100 (0.01%) to disrupt aggregates, but verify detergent doesn't interfere with your biological system [10]. For colored compounds, measure absorbance at longer wavelengths where the compound may not absorb significantly [9].

Problem: Unexpected activity in primary screening that disappears in confirmation assays

Solution: This classic signature of assay interference requires systematic triage:

- Run interference counter-screens specific to your detection technology (e.g., luciferase inhibition assay for reporter gene systems) [9] [11].

- Test for redox activity using assays like horseradish peroxidase-phenol red (HRP-PR) [10].

- Evaluate thiol reactivity using glutathione (GSH) or other thiol-based probes [10].

- Examine SAR; true bioactive compounds typically show rational structure-activity relationships, while interference often lacks coherent SAR [10].

Problem: High background signal in UV-Vis detection

Solution: Several approaches can reduce background interference:

- For fluorescent assays, shift to red-shifted fluorophores where compound autofluorescence is less prevalent [9].

- Implement mathematical correction methods like direct orthogonal signal correction (DOSC) when turbidity or other interfering substances are present [12].

- For binding assays, include control wells with excess unlabeled competitor to establish specific signal range [10].

- Optimize instrument settings - reduce detector gain or increase bandwidth to minimize noise [6].

Problem: Colored compounds interfering with spectrophotometric readings

Solution: Colored compounds can directly absorb light at detection wavelengths. Use alternative detection methods not based on absorbance, such as mass spectrometry or radiometric detection, if available [10]. Alternatively, employ background subtraction techniques with reference wavelengths where the colored compound still absorbs but the assay signal does not occur [12]. For fixed-wavelength detection systems, consider implementing dual-wavelength measurements to correct for compound absorption [6].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Detecting Common Interference Types

| Interference Type | Detection Method | Key Reagents | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiol Reactivity | Fluorescence-based thiol-reactive assay [9] | (E)-2-(4-mercaptostyryl)-1,3,3-trimethyl-3H-indol-1-ium (MSTI) | Concentration-dependent fluorescence increase indicates thiol reactivity |

| Redox Activity | Redox activity assay [9] | DTT, reducing agents | Production of hydrogen peroxide detected via coupled assay |

| Luciferase Interference | Luciferase inhibition assay [9] [11] | D-Luciferin, firefly-Luciferase | Decreased luminescence in compound-treated wells indicates inhibition |

| Autofluorescence | Multi-wavelength fluorescence measurement [11] | Cell-based or cell-free systems | Signal detected without assay activation indicates autofluorescence |

| Aggregation | Dynamic light scattering [10] | Assay buffer | Particles >50 nm indicate aggregation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Luciferase Inhibition Counter-Screen

Purpose: Identify compounds that inhibit luciferase enzyme activity, which is crucial for interpreting results from luciferase-based reporter assays [11].

Reagents:

- D-Luciferin substrate (Sigma-Aldrich)

- Firefly-Luciferase enzyme (Sigma-Aldrich)

- Assay buffer: 50 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.6, 13.3 mM magnesium acetate, 0.01 mM D-luciferin, 0.01 mM ATP, 0.01% Tween, 0.05% BSA

- Test compounds dissolved in DMSO

- Positive control: PTC-124 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) [11]

Procedure:

- Dispense 3 μL substrate mixture into 1,536-well white plates.

- Transfer 23 nL test compounds or controls using Pintool station.

- Add 1 μL of 10 nM firefly-Luciferase solution to all wells except control columnts receiving buffer only.

- Incubate 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Measure luminescence intensity using plate reader (e.g., Viewlux).

- Analyze data by fitting concentration-response curves to Hill equation [11].

Interpretation: Compounds showing concentration-dependent decrease in luminescence are luciferase inhibitors and may cause false positives in luciferase-based assays.

Protocol 2: Turbidity Correction in UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

Purpose: Correct for turbidity interference in UV-Vis measurements using direct orthogonal signal correction (DOSC) with partial least squares (PLS) [12].

Reagents:

- Standard turbidity solutions (formazine-based, 0-400 NTU)

- Target analyte solutions of known concentration

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., AGILENT Cary 100)

Procedure:

- Prepare calibration set with varying turbidity and analyte concentrations.

- Measure full UV-Vis spectra (220-600 nm) of all samples.

- Apply DOSC algorithm to filter out turbidity-related spectral components.

- Select feature wavelengths from corrected spectra.

- Establish PLS regression model using corrected absorbance values.

- Validate model with independent test samples [12].

Interpretation: Effective correction demonstrates improved correlation (R² >0.99) between predicted and actual values compared to uncorrected data (R² ~0.55) [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Identifying and Mitigating Chemical Interference

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glutathione (GSH) | Thiol reactivity probe [10] | Detects compounds that react with biological thiols |

| DTT | Reducing agent for redox cycling detection [10] | Identifies redox-active compounds that generate H₂O₂ |

| D-Luciferin | Luciferase substrate [11] | Essential for luciferase inhibition counter-screens |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent [10] | Disrupts compound aggregates at 0.01% concentration |

| Formazine standard | Turbidity standard [12] | Quantifies and corrects for turbidity interference |

| Liability Predictor | Web-based prediction tool [9] | Predicts thiol reactivity, redox activity, luciferase interference |

| InterPred | Web-based prediction tool [11] | Predicts luciferase inhibition and autofluorescence |

Workflow Visualization

Hit Triage Workflow for Identification of Assay Artifacts

Chemical Interference Mechanisms in Bioassays

The sample matrix—the environment in which your analyte resides—is a critical but often overlooked variable in UV-Vis spectroscopy. Factors such as pH, temperature, and conductivity can significantly alter the interaction between light and matter, leading to shifts in absorbance maxima, changes in peak shape, and overall inaccuracies in quantitative results [13] [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing and controlling for these matrix effects is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental requirement for generating reliable, reproducible data. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support to address these specific challenges directly.

Quantitative Impact of Environmental Factors

The following table summarizes the specific effects of pH, temperature, and conductivity on UV-Vis spectral data, which are crucial for diagnosing issues during analysis.

Table 1: Impact of Sample Matrix Factors on UV-Vis Spectral Accuracy

| Matrix Factor | Primary Effect on Spectrum | Underlying Mechanism | Quantitative Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Shift in absorption peak position and absorption coefficient [13] | Alters the electronic state and structure of molecules, particularly those with acidic/basic functional groups [13] | Can cause bathochromic (red) or hypsochromic (blue) shifts, leading to incorrect analyte identification or quantification. |

| Temperature | Change in spectral waveform and bandwidth [13] [14] | Alters the energy emission of electrons and molecular collision rates; can narrow bands at lower temperatures [13] [14] | A parameter study showed the Gaussian broadening parameter (σ₀) increased from 437 to 500 as temperature rose from 5°C to 90°C [14]. |

| Conductivity | Increased background absorbance, especially in the UV range [13] | Soluble inorganic salt ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) have strong absorption in the ultraviolet band [13] | Elevates baseline absorbance, which can obscure analyte peaks and lead to overestimation of concentration. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

My baseline is unstable and drifts. Could my sample matrix be the cause?

Yes, a drifting baseline is a common symptom of matrix-related issues. Temperature fluctuations within the sample compartment or laboratory can cause ongoing intensity fluctuations [15]. Similarly, if your sample contains suspended particles that slowly settle, or if the sample temperature is not consistent, the scattering and absorption properties can change, leading to a drifting baseline [7] [15]. First, record a fresh blank spectrum under identical conditions. If the blank is stable, the issue is likely with your sample preparation or homogeneity [15].

Why are my expected peaks suppressed or missing entirely?

Peak suppression can occur for several matrix-related reasons. If the pH of the solution causes the analyte to exist in a non-absorbing form, the expected peak may disappear [13]. Additionally, a sample matrix with high ionic strength (conductivity) can cause phenomena like peak broadening or shifting, potentially moving a small peak into the noise floor of the instrument [13] [15]. Verify your sample pH and ensure the analyte is in its absorbing form. Diluting the sample with solvent can also help reduce ionic strength interference.

How does pH specifically lead to incorrect concentration calculations?

The Lambert-Beer Law (A = ε·c·l) assumes a constant molar absorptivity (ε). However, the pH of a solution can directly affect the absorption coefficient (ε) of a molecule [13]. If you calculate concentration using a molar absorptivity value determined at one pH, but your sample is at a different pH, the calculated concentration will be inaccurate because the actual absorptivity has changed.

I am analyzing a conjugated organic molecule. Why is the spectrum so sensitive to temperature?

Conjugated molecules often have electronic properties and dipole moments that are highly temperature-dependent [14]. Even at absolute zero, molecules possess vibrational energy that causes deviations from ideal, planar geometries. At room temperature, rapid internal rotation can further broaden spectral bands [14]. Fitting studies have shown that the parameter defining the broadness of Gaussian curves (σ₀) increases linearly with temperature, directly leading to broader, less resolved peaks [14].

Experimental Protocols for Matrix Compensation

Data Fusion Method for Multi-Factor Compensation

Considering the complexity of environmental factors, a data fusion method has been proposed to compensate for the influence of pH, temperature, and conductivity simultaneously [13]. This method is based on the weighted superposition of the spectral data and the three environmental factors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrometer (e.g., Agilent Cary 60) | To collect high-resolution absorption spectra of samples [13]. |

| Multi-factor Portable Meter (e.g., Hach SensION+MM156) | To simultaneously and accurately measure the pH, temperature, and conductivity of each sample [13]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes (10 mm path length) | To hold liquid samples, ensuring transparency across the UV and visible light range [13] [7]. |

| Potassium Hydrogen Phthalate (KHP) | A standard substance for preparing COD stock solutions (e.g., 500-1000 mg/L) for method validation [13] [16]. |

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., water, methanol) | For diluting samples and standards; their UV "cutoff" wavelength must be considered to avoid background interference [17]. |

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & Measurement: Collect your sample set (e.g., 240 water samples over a year). For each sample, immediately measure its UV-Vis spectrum and record its pH, temperature, and conductivity using a multi-parameter meter [13].

- Spectral Feature Extraction: Use algorithms like the Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA) to identify the feature wavelengths most relevant to your analyte, reducing data dimensionality [16].

- Model Establishment: Establish a prediction model (e.g., for Chemical Oxygen Demand) by fusing the spectral feature wavelengths and the measured environmental factors. The fusion creates a weighted input matrix that the model uses to learn the relationship between the "true" signal and the interfering factors [13].

- Validation: The data fusion approach has been shown to significantly improve accuracy, with one study achieving a determination coefficient of prediction (R²Pred) of 0.9602, compared to lower values from models ignoring environmental factors [13].

Workflow for Diagnosing Matrix Interference

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for troubleshooting sample matrix effects, helping to pinpoint the specific factor causing spectral inaccuracies.

Diagnosing Matrix Interference

Advanced Topic: Spectral Deconvolution with the Pekarian Function

For in-depth analysis of conjugated molecules in solution, the Pekarian Function (PF) offers a powerful fitting approach that accounts for vibronic effects [14]. This is especially useful for quantifying the effect of temperature on band shape.

Methodology:

- The PF fit is applied to experimental absorption or fluorescence spectra via optimization of five parameters (S, ν₀, Ω, σ₀, δ) that define the band shape [14].

- The parameter σ₀, which represents the Gaussian broadening, has been shown to have a strong temperature dependence. By fitting spectra collected at different temperatures, you can quantitatively describe how temperature affects the vibrational broadening of your specific molecule [14].

- This method can be implemented using commercial software like PeakFit or Origin, or via custom Python scripts [14].

FAQs: Understanding Interferences in UV-Vis Analysis

Q1: What are the most common endogenous interferents in clinical serum and plasma samples? The most frequent endogenous interferents are hemolysis, lipemia (high lipid content), and icterus (high bilirubin), which can significantly alter UV-Vis spectrophotometric measurements [18] [19]. One study on polytraumatized patients found that within 10 days of admission, 31.8% of samples showed hemolysis, 15.9% showed lipemia, and 12.5% showed increased bilirubin [18]. These interferents affect results through mechanisms such as spectral overlap, chemical interactions, and light scattering.

Q2: How does hemolysis interfere with UV-Vis spectroscopic measurements? Hemolysis causes spectral interference primarily because hemoglobin is a strong chromophore. Oxyhemoglobin has strong absorbance peaks at 415 nm (the Soret band), and between 540-589 nm [20] [21]. This can lead to two main problems:

- Spectrophotometric Interference: The absorbance bands of hemoglobin can overlap with the detection wavelength of the target analyte, causing false elevations or suppressions of the measured signal [20] [22].

- Chemical Interference: The release of intracellular components, such as enzymes like lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), or ions like potassium, can chemically interfere with assay reactions [20] [21]. For example, hemoglobin can cause overestimation in formazan-based assays by participating in non-specific redox reactions [22].

Q3: What is the practical impact of lipemia on sample analysis? Lipemia, characterized by turbidity from high concentrations of triglycerides or lipoproteins, causes physical interference via light scattering [3] [19]. This results in an increased background absorbance, which can lead to inaccurate, often elevated, readings for the target analyte [18] [19]. In research settings, lipemia has been shown to interfere with the analysis of extracellular vesicles (EVs), affecting particle size distribution and concentration measurements [18].

Q4: What are some strategies to overcome interferences in UV-Vis spectroscopy? Several methodological approaches can mitigate interference:

- Sample Preparation: Ultracentrifugation can remove lipid micelles in lipemic samples [19]. For hemolyzed samples, filtration or centrifugation is recommended, though it may not be feasible for very small volumes [3].

- Spectroscopic Techniques: Derivative spectroscopy helps resolve overlapping peaks and corrects for baseline shifts caused by scattering [3]. Isoabsorbance measurements and three-point correction methods can also be used to subtract background interference from a known interferent [3].

- Method Selection: Using more specific quantification methods, such as the SLS-Hemoglobin method instead of general protein assays, can reduce interference from other sample components [23].

Q5: How can I differentiate between in vivo and in vitro hemolysis? Differentiating the origin of hemolysis is crucial for correct clinical interpretation.

- In vivo hemolysis occurs due to pathological conditions within the body. Key indicators include low plasma haptoglobin, elevated indirect bilirubin, and increased reticulocyte count [24].

- In vitro hemolysis is caused by improper sample collection or handling (e.g., use of too thin a needle, vigorous mixing). If multiple samples from the same patient are available, and only one is hemolyzed, in vitro hemolysis is the likely cause [24]. Automated analyzers quantify this through a Hemolysis Index (HI) [20] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Quantifying Hemolysis

Problem: Suspected hemolysis in serum/plasma samples is causing erratic or unreliable absorbance readings.

Background: Hemolysis is the most common pre-analytical interference. Visual inspection is unreliable for concentrations below 2 g/L and is subjective [25] [24]. Objective spectrophotometric methods are preferred.

Solution: Direct UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Measurement This protocol allows for the detection and semi-quantification of free hemoglobin in serum or plasma.

Materials:

- Microplate reader or standard UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Transparent 96-well plate or quartz cuvette

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or equivalent diluent

Procedure:

- If using a microplate reader, transfer 50 µL of serum/plasma into a well. For a cuvette, dilute the sample 1:1 with PBS [18] [25].

- Measure the absorption spectrum from 350 nm to 660 nm.

- Examine the spectrum for characteristic hemoglobin peaks. A sharp peak at ~415 nm (Soret band) and smaller peaks at 540 nm and 575 nm are indicative of hemolysis [25] [21] [23].

Interpretation: The height of the absorbance peak at 415 nm is proportional to the concentration of free hemoglobin. While visual inspection of the spectrum is diagnostic, for quantification, a standard curve should be prepared using a known hemoglobin standard.

Guide 2: Managing Lipemic and Icteric Samples

Problem: Sample turbidity (lipemia) or yellow discoloration (icterus) is interfering with absorbance measurements.

Background: Lipemia causes light scattering, elevating the baseline absorbance. Icterus (bilirubin) absorbs light broadly between ~400-470 nm, which can overlap with many assays [18] [19].

Solution: Background Correction and Sample Treatment

Procedure for Background Subtraction:

- Three-Point Correction: If the background interference is roughly linear, measure the absorbance at the analytical wavelength (λanalytical) and at two nearby wavelengths on either side (λ₁ and λ₂). The corrected absorbance is: *Acorrected = Aλanalytical - [(Aλ₁ + Aλ₂)/2]* [3].

- Derivative Spectroscopy: This is a more robust method for non-linear backgrounds. Most modern spectrometer software can calculate the first or second derivative of the absorption spectrum. This technique eliminates constant or linearly sloping background signals, revealing the analyte's peak as an inflection point (first derivative) or a negative peak (second derivative) [3].

Procedure for Sample Treatment (Lipemia):

- High-Speed Ultracentrifugation: This is the most effective method. Centrifuge the sample at >100,000 × g for 15-60 minutes to pellet the lipid particles [19].

- Carefully extract the clarified infranatant for analysis, avoiding the lipid layer.

Data Presentation: Effects of Hemolysis on Common Biochemical Analytes

The table below summarizes the direction and clinical significance of interference caused by in vitro hemolysis on various common biochemical tests, based on experimental data.

Table 1: Effect of In Vitro Hemolysis on Routine Biochemistry Tests [21]

| Analyte | Direction of Interference | Clinical Significance (at Hb ~4.5 g/L) | Primary Interference Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LD) | ↑ Increase | >4.5-fold increase | Intracellular release from RBCs |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) | ↑ Increase | ~2.5-fold increase | Intracellular release from RBCs |

| Potassium (K⁺) | ↑ Increase | ~1.4-fold increase | Intracellular release from RBCs |

| Inorganic Phosphate | ↑ Increase | Significant increase | Intracellular release from RBCs |

| Total Bilirubin | ↓ Decrease | ~100% decrease | Chemical inhibition of diazo reaction |

| Gamma Glutamyltransferase (GGT) | ↑ Increase | ~1.2-fold increase | Spectral/Chemical interference |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) | ↑ Increase | ~1.2-fold increase | Spectral/Chemical interference |

| Sodium (Na⁺) | ↓ Decrease | Not clinically significant | Dilutional effect |

| Glucose | ↓ Decrease | Not clinically significant | Chemical degradation |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Interference Detection and Mitigation in UV-Vis Analysis

This diagram outlines a systematic workflow for identifying the type of interference in a sample and selecting an appropriate mitigation strategy.

Mechanism of Hemoglobin Interference in Formazan-Based Assays

This diagram illustrates the specific mechanism by which hemoglobin interferes with a common type of colorimetric assay, leading to overestimation of results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Interference Management

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Isolate and purify analytes like Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) from interfering proteins and lipids in complex biofluids [18]. | EV isolation from hemolytic or lipidemic serum for downstream miRNA analysis [18]. |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | A detergent that lyses red blood cells and forms a complex with hemoglobin, providing a stable and specific chromogen for quantification with minimal interference [23]. | Preferred method for specific and safe hemoglobin quantification in the development of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) [23]. |

| Potassium Cyanide (KCN) | Component of the reference cyanmethemoglobin (CN-Hb) method. Converts hemoglobin to stable cyanmethemoglobin for measurement [25]. | Classic method for accurate hemoglobin determination; requires careful handling due to toxicity [25] [23]. |

| Derivative Spectroscopy Software | A mathematical processing technique applied to absorption spectra to resolve overlapping peaks and eliminate baseline drift from scattering [3]. | Correcting for the sloping baseline in lipemic samples or the broad absorbance from bilirubin to reveal the true analyte peak. |

| Parenteral Nutrition Emulsion (e.g., SmofKabiven) | A standardized lipid emulsion used to spike control serum samples in experiments to simulate lipemia and study its effects [18]. | Creating consistent in vitro models of lipemia to test and validate interference mitigation protocols [18]. |

In high-throughput screening (HTS) for drug discovery, chemical interference is a major cause of false positives and false negatives, leading to wasted resources and erroneous conclusions. These interference compounds directly affect assay detection technology rather than the biological target of interest. This case study explores how interference derailed an HTS campaign and outlines the systematic troubleshooting approaches that can identify and mitigate such issues.

A prominent example comes from the Tox21 consortium, which screened 8,305 unique chemicals and found that 9.9% actively inhibited luciferase enzyme activity, a common source of false positives in reporter gene assays [11]. This highlights the scale of the problem in real-world screening efforts.

Case Study: The Luciferase Reporter Assay That Failed

An HTS campaign was launched to identify novel agonists for a therapeutically relevant G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) using a luciferase-based reporter assay in HEK-293 cells.

The Initial Problem

The primary screen yielded a high hit rate of ~12%, far exceeding expected biological activity. Initial excitement was tempered when dose-response characterization showed that many "hits" exhibited steep, non-saturable curves, a classic signature of non-specific interference rather than genuine receptor agonism [11].

The Investigation

Researchers employed a multi-faceted approach to diagnose the issue:

- Counter-Screening: All active compounds were run in a cell-free luciferase biochemical inhibition assay. This orthogonal assay revealed that the majority of hits were directly inhibiting the luciferase enzyme itself [11] [26].

- Cytotoxicity Analysis: Examination of nuclear count and cell morphology data from the original HCS images flagged a subset of hits that caused significant cell death or detachment, leading to signal loss misinterpreted as biological activity [26].

- Structural Analysis: Using self-organizing maps and hierarchical clustering, researchers found that the interfering compounds often shared common chemical substructures, such as thiol or quinone groups, known to be problematic [11].

The Root Cause and Resolution

The investigation concluded that the campaign was compromised by two main types of interferents:

- Luciferase Inhibitors: These chemicals blocked the enzymatic reaction, directly reducing the luminescence signal and mimicking the effect of an inhibitor in an agonist assay.

- Cytotoxic Compounds: These caused cell death or loss of adhesion, reducing the total signal and being misinterpreted as activity.

By applying these diagnostic steps, the research team could "flag" and remove the interfering compounds, salvaging the screening investment and focusing resources on a smaller set of mechanistically validated hits for further development.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Overcoming Interference

This guide provides a structured approach to diagnose interference in your HTS campaigns.

Problem: High Hit Rate with Atypical Pharmacology

- Description: An unexpectedly large number of actives are identified, and their concentration-response curves (CRCs) are often class 4 (non-sigmoidal, incomplete curve) or class 3 (sigmoidal but with low efficacy) [11].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Run compounds in an orthogonal assay with a different detection technology (e.g., switch from luminescence to fluorescence or AlphaScreen) [26].

- Perform a cell viability counter-screen (e.g., ATP content, resazurin reduction) in parallel to the main assay.

- Analyze the chemical structures of the hits for known problematic substructures (e.g., PAINS) [11].

- Solution: Implement a tiered testing paradigm where primary screen actives must be confirmed in a orthogonal secondary assay before being declared validated hits.

Problem: Compound Autofluorescence

- Description: Compounds emit light in the same wavelength range as the fluorophore used for detection, leading to elevated background or false positive signals, particularly in fluorescence-based HCS assays [26].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Visually inspect wells for fluorescence in the absence of the fluorescent probe.

- Perform a control experiment by measuring the compound's fluorescence spectrum alone at the assay's excitation/emission wavelengths [26].

- Statistically, fluorescent compounds will appear as outliers in the fluorescence intensity distribution of the entire compound library [26].

- Solution:

- For HCS, switch to a fluorescent probe with longer wavelength spectra (e.g., red-shifted) to move away from the common autofluorescence range of many compounds [26].

- Use ratiometric probes or FRET-based assays which are less susceptible to autofluorescence effects.

- Employ image analysis algorithms that can identify and mask autofluorescent objects [26].

Problem: Signal Quenching or Light Scattering

- Description: Compounds absorb the excitation or emission light, or cause light scattering (e.g., by forming colloids or precipitates), leading to a reduction in signal that can be misinterpreted as biological inhibition [26] [27].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Solution:

- Centrifuge compound plates to re-dissolve precipitates before assay initiation.

- For UV-Vis, use derivative spectroscopy to eliminate baseline shifts and overcome scattering effects from unidentified interferents [3].

- Dilute the sample to reduce absorbance into the optimal range (0.2-1.0 AU) and minimize inner-filter effects [27].

Problem: Cytotoxicity Masquerading as Bioactivity

- Description: Compounds that kill cells or cause them to detach from the plate can produce a global reduction in all signals, which may be falsely interpreted as a specific inhibitory effect [26].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Always include a parallel cell viability assay.

- In HCS, analyze the number of cells per well (nuclear count). A substantial reduction is a clear red flag [26].

- Manually review images from active wells for signs of cell rounding, membrane blebbing, or debris.

- Solution: Normalize the primary assay readout to a cell number metric (e.g., total DNA stain) or viability marker to distinguish specific activity from general toxicity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common types of chemical interference in HTS? The most prevalent types are assay technology-based interference, including luciferase inhibition, compound autofluorescence, and signal quenching. Biological interference, such as cytotoxicity leading to non-specific cell death, is also very common [11] [26].

Q2: How can I predict if a new chemical compound is likely to cause interference? Machine learning models trained on chemical descriptors can predict interference. For example, the InterPred web-based tool was developed using Tox21 data and can predict the likelihood of luciferase inhibition or autofluorescence with ~80% accuracy based on a compound's structure [11].

Q3: Our UV-Vis analysis is giving inconsistent results. What are the first things to check? First, check your sample and sample holder. Ensure cuvettes are clean and free of scratches, and that your sample is clear and not cloudy. Second, verify the instrument's calibration and that the sample concentration is within the linear range of the Beer-Lambert law (absorbance ideally between 0.2 and 1.0 AU) [7] [27].

Q4: What is a Z'-factor, and what value is considered acceptable for an HTS assay? The Z'-factor is a statistical metric used to assess the robustness and quality of an HTS assay. It incorporates both the assay signal dynamic range and the data variation of the sample and control measurements. A Z'-factor value of 0.5 or higher is considered acceptable for HTS, with higher values (e.g., >0.7) indicating an excellent assay [28].

Q5: Can interference ever be useful? While typically a nuisance, understanding interference can be used creatively. In photography, chromatic aberration (color fringing from lens interference) is corrected, but can also be applied subtly for stylistic, dreamlike effects [29]. This is a rare case where an artifact can be repurposed.

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from one of the largest interference screening studies conducted by the Tox21 consortium, which tested 8,305 chemicals [11].

| Interference Type | Assay System | Active Chemicals | Key Characteristics of Interferents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Inhibition | Cell-free biochemical | 9.9% | Often contain thiol-reactive or redox-active groups [11] |

| Autofluorescence (Blue) | Cell-based (HEK-293) | 5.2% | Emit light in the blue wavelength range [11] |

| Autofluorescence (Green) | Cell-based (HEK-293) | 4.5% | Emit light in the green wavelength range [11] |

| Autofluorescence (Red) | Cell-based (HEK-293) | 0.5% | Fewer compounds emit in the far-red spectrum [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To identify compounds that directly inhibit firefly luciferase activity, a common source of false positives in reporter gene assays.

Reagents:

- D-Luciferin (substrate)

- Firefly Luciferase (enzyme)

- ATP

- Tris-acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.6)

- Magnesium acetate (13.3 mM)

- Test compounds and controls (e.g., PTC-124 as a positive control inhibitor)

Methodology:

- Dispense a luciferin/substrate mixture into a 1536-well plate.

- Transfer test compounds and controls to the assay plate via pintool.

- Add the firefly luciferase enzyme to all wells except background control wells, which receive buffer only.

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Measure luminescence intensity using a plate reader.

- Fit the concentration-response data to the Hill equation to calculate IC₅₀ and efficacy values.

Data Interpretation: Compounds showing concentration-dependent inhibition of luminescence in this cell-free system are flagged as luciferase interferents and deprioritized for the cell-based primary assay.

Purpose: To identify compounds that are intrinsically fluorescent at wavelengths used in the primary HCS assay.

Reagents:

- Assay medium (with and without cells)

- Cell lines relevant to the primary screen (e.g., HepG2, HEK-293)

- Test compounds

Methodology:

- Seed cells into microplates (or leave some wells with medium only for cell-free measurements).

- Add test compounds in a concentration series.

- Incubate under standard culture conditions.

- Using an HCS imager or plate reader, measure fluorescence intensity at the specific wavelengths used in the primary assay (e.g., blue, green, red channels).

- No fluorescent probes or dyes are added in this assay.

Data Interpretation: Compounds that produce a fluorescence signal significantly above the background (DMSO control) are identified as autofluorescent. Their activity in the primary HCS assay must be carefully scrutinized, as the signal may be artifactual.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Essential for UV-Vis measurements due to high transmission of UV and visible light; reusable and chemically resistant [7] [30]. |

| D-Luciferin | The standard substrate for firefly luciferase, used in both cell-based reporter assays and cell-free inhibition counter-screens [11]. |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | A certified reference material used for validating the wavelength accuracy of UV-Vis spectrophotometers during calibration [27]. |

| Extra-Low Dispersion (ED) Glass Lenses | A key component in high-quality microscope objectives and HCS imagers that minimizes chromatic aberration, improving image clarity and quantification accuracy [29]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | A microplate coating used to enhance cell adhesion, which helps mitigate artifacts caused by compound-induced cell detachment in cell-based assays [26]. |

Visual Workflows: From Screening to Validation

HTS Hit Triage Workflow

UV-Vis Interference Diagnosis

Practical Solutions: Spectral Correction Techniques and Advanced Chemometric Models

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: When should I use the isoabsorbance method instead of three-point correction? Use the isoabsorbance method when dealing with a single, known interferent whose absorbance characteristics are well-defined and distinct from your analyte [3]. Use three-point correction for complex sample matrices with unknown or multiple interferents that cause a non-linear, sloping background [3].

Q2: Can derivative spectroscopy be used for quantitative analysis? Yes, derivative spectroscopy is excellent for quantitative analysis. It not only resolves overlapping peaks but also eliminates baseline shifts, thereby improving the accuracy of quantitative measurements [3]. The inflection points in the original spectrum become zero-crossings in the first derivative, which can be precisely measured.

Q3: Why is my three-point correction not effectively reducing background noise? This typically occurs if the selected wavelengths do not accurately model the background. Ensure the two reference wavelengths are chosen in regions where the analyte has minimal or no absorbance, and that they are on either side of the analytical wavelength. The background absorbance should be linear between them. Re-evaluating your wavelength selection using pure analyte and interferent spectra often resolves this [3].

Q4: What are the limitations of these classical correction methods? The primary limitation is their effectiveness in overly complex mixtures. Isoabsorbance is practical only with a single interferent [3]. Three-point correction assumes a linear background between reference wavelengths, which may not hold for all samples [3]. Derivative spectroscopy can amplify high-frequency noise if not applied carefully [3]. For highly complex samples, advanced chemometric techniques like DOSC-PLS may be required [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Results Due to Known Chemical Interferent

- Problem: A known contaminant in your samples absorbs light at or near your analyte's wavelength, leading to overestimation of concentration.

- Solution: Apply the Isoabsorbance Method.

- Protocol:

- Identify the analytical wavelength (λana) for your target analyte.

- Identify a second wavelength, the isoabsorbance point (λiso), where the interfering substance has the same absorbance value (Aiso) as it does at λana.

- Measure the total absorbance of your sample mixture at both wavelengths: Amix(λana) and Amix(λiso).

- Calculate the corrected absorbance for your analyte: Acorrected = Amix(λana) - Amix(λ_iso).

- Why it works: By subtracting Amix(λiso), you are removing the specific contribution of the interferent at the analytical wavelength, leaving only the signal from your target analyte [3].

Issue 2: High or Non-Linear Background from Complex Matrices

- Problem: Samples with multiple interferents or a complex matrix produce a significant, non-linear background that obscures the analyte's peak.

- Solution: Implement Three-Point Correction.

- Protocol:

- Select your analytical wavelength (λana) at the peak of your analyte.

- Choose two reference wavelengths (λ1 and λ2), one on either side of λana. These should be in regions where the analyte has minimal absorbance but the background is present.

- Measure the absorbance of your sample at all three wavelengths.

- Calculate the corrected absorbance: Acorrected = A(λana) - [A(λ1) + ( (λana - λ1) / (λ2 - λ1) ) * (A(λ2) - A(λ_1)) ].

- Why it works: This method estimates the background absorbance under the analyte's peak by linearly interpolating between the two reference wavelengths and then subtracts this estimated background [3].

Issue 3: Severe Overlap of Analyte and Interferent Peaks

- Problem: The absorption spectrum of an interferent overlaps significantly with your target analyte, making it impossible to find clear wavelengths for measurement.

- Solution: Utilize Derivative Spectroscopy.

- Protocol:

- Collect the full absorbance spectrum of your sample.

- Using your spectrometer's software, generate the first or second derivative of the absorbance spectrum.

- In the derivative spectrum, the overlapping peaks in the original zero-order spectrum are transformed. The inflection points of the original spectrum become zero-crossings in the first derivative, and the peaks become negative peaks in the second derivative, allowing for better differentiation [3].

- Perform quantitative analysis using the peak-to-trough measurements in the derivative spectrum instead of the absorbance in the original spectrum.

- Why it works: Derivative spectroscopy enhances the resolution of overlapping bands and suppresses slow-varying background signals like baseline shifts and scattering [3].

Comparison of Classical Correction Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, applications, and limitations of the three classical correction methods.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoabsorbance [3] | Subtract interferent signal using its equal absorbance at two wavelengths. | A single known interferent with a stable, known spectrum. | Simple calculation; highly effective for its specific use case. | Impractical for complex mixtures with multiple interferents. |

| Three-Point Correction [3] | Model and subtract a linear background absorbance under the analyte peak. | Complex samples with a non-linear, sloping background. | Effective for unknown interferents causing a drifting baseline. | Assumes background is linear between the two reference wavelengths. |

| Derivative Spectroscopy [3] | Resolve overlapping peaks by converting absorbance to its 1st or 2nd derivative. | Severe spectral overlap between analyte and interferent(s). | Eliminates baseline shifts and resolves closely overlapping peaks. | Can amplify high-frequency signal noise; requires good data quality. |

Experimental Workflows

Isoabsorbance Method Workflow

Three-Point Correction Workflow

Derivative Spectroscopy Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Hydrogen Phthalate (KHP) | A primary standard for preparing COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) standard solutions to validate correction methods [12]. | Dissolved in deionized water; used to create calibration curves for UV-Vis analysis of organic pollution [12]. |

| Formazine Suspension | A standard solution for calibrating and validating methods against turbidity (physical interference) [12]. | Follows NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Unit) standard (ISO 7027-1984); provides stable, homogeneous particles for scattering studies [12]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | The optimal sample holder for UV-Vis spectroscopy across both ultraviolet and visible light regions [7]. | Preferred over plastic due to high transmission and chemical resistance; ensure proper path length and cleanliness to avoid errors [7]. |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | A certified reference material for wavelength accuracy verification during instrument calibration [27]. | Critical for ensuring the precision of wavelength selection in all methods, especially derivative and isoabsorbance. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used for sample dilution, as a blank, and to ensure the sample matrix does not introduce unexpected absorption [27]. | Ensure the solvent has no significant absorption in your analytical wavelength range (e.g., ethanol absorbs strongly below 210 nm) [27]. |

FAQs: Choosing a Hemoglobin Quantification Method

Q1: Why is the choice of quantification method so critical in hemoglobin (Hb) research?

Accurate characterization of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs)—including Hb content, encapsulation efficiency, and yield—is crucial for ensuring effective oxygen delivery, economic viability, and the prevention of adverse effects caused by free Hb [31]. Using a non-specific method when other proteins are present can lead to inaccurate concentration values, potentially resulting in the oversight of toxic effects or the unnecessary termination of a promising product's development [31] [23].

Q2: What is the primary advantage of using an Hb-specific assay like SLS-Hb over a general protein assay?

Hb-specific assays, such as the SLS-Hb or cyanmethemoglobin (CN-Hb) methods, are designed to react with the heme group in hemoglobin, making them highly selective. In contrast, general protein assays (e.g., BCA, Bradford) respond to the protein component (amino acids) and will also detect any contaminating proteins present in your sample [31]. If the absence of other proteins is not confirmed, non-specific methods can produce overestimated and inaccurate Hb concentration values.

Q3: My SLS-Hb assay shows high background. What could be the cause?

Physical interferences, such as light scattering from suspended solid impurities or air bubbles in the sample, can cause high background absorbance [3]. Ensure your Hb sample is properly clarified through centrifugation or filtration prior to measurement. Furthermore, always use an appropriate blank (e.g., the buffer used to prepare the sample) to subtract any background signal.

Q4: Are there any safety concerns with the SLS-Hb method compared to other methods?

A major advantage of the SLS-Hb method is its safety profile. It serves as a non-hazardous substitute for the traditional cyanmethemoglobin (CN-Hb) method, which uses toxic potassium cyanide (KCN) [31] [32]. The SLS-Hb method eliminates the safety risks and associated disposal regulations of cyanide-based reagents.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SLS-Hb Assay Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear standard curve | Incorrect pipetting; inaccurate standard preparation. | Check pipette calibration; prepare fresh standard dilutions; ensure thorough mixing. |

| Low precision (high variability) | Inconsistent sample mixing; air bubbles in cuvette; detector issues. | Mix samples and reagents uniformly; tap cuvette to dislodge bubbles; ensure detector is functioning. |

| Absorbance outside ideal range (0.1-1.0) | Sample concentration too high or too low. | Dilute concentrated samples; use a cuvette with a shorter path length for very concentrated samples. |

| Unexpectedly low Hb value | Incomplete lysis of red blood cells. | Confirm that the SLS reagent is adequately lysing the cells; check reagent freshness. |

Comparison of Hb Quantification Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of common UV-Vis spectroscopy-based methods for hemoglobin quantification, based on a recent comparative study [31].

| Quantification Method | Specificity for Hb | Principle of Detection | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLS-Hb | Yes | Binds to heme group, forming SLS-methemoglobin. | Specific, cost-effective, easy to use, non-hazardous, high accuracy/precision. | Limited information on specific chemical interferences. |

| Cyanmethemoglobin (CN-Hb) | Yes | Converts Hb to cyanmethemoglobin. | High specificity, international reference standard. | Use of toxic potassium cyanide, requires hazardous waste disposal. |

| Absorbance at Soret Peak (~414 nm) | Yes | Direct absorbance of the heme group. | Rapid, no reagents required. | Can overestimate if other heme proteins are present; susceptible to light scattering. |

| BCA Assay | No | Reduces Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ in alkaline conditions (protein backbone). | High sensitivity, compatible with detergents. | Not specific to Hb; overestimates if other proteins are present. |

| Bradford (Coomassie) Assay | No | Dye binding to basic and aromatic amino acid residues. | Very rapid, simple protocol. | Not specific to Hb; variable response to different proteins; dye can stain cuvettes. |

| Absorbance at 280 nm | No | Absorbance by aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine). | Simple and direct, no reagents required. | Not specific to Hb; highly susceptible to interference from nucleic acids. |

Experimental Protocol: Hb Quantification via SLS-Hb Method

Principle: Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) readily lyses red blood cells and reacts with hemoglobin to form a stable, colored SLS-methemoglobin complex, which can be quantified by its absorbance in the visible range [31] [32].

Materials:

- SLS reagent (commercially available or prepared)

- Hemoglobin standard stock solution

- Test samples

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer or plate reader

- Cuvettes or a transparent 96-well microplate

- Pipettes and appropriate tips

Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Curve: Prepare a series of dilutions from your Hb standard stock solution to cover a concentration range of 0-2 mg mL⁻¹.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute your unknown samples as needed to fall within the linear range of the standard curve.

- Reaction: Mix a fixed volume of each standard and unknown sample (e.g., 20 µL) with the SLS working reagent (e.g., 1 mL for cuvettes or 200 µL for microplates). For microplates, ensure proper mixing on a plate shaker.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at room temperature for a few minutes to allow for complete color development.

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the solutions at the recommended wavelength (e.g., 539 nm or as per reagent manufacturer's instructions) [32]. Use a blank containing SLS reagent in buffer for background subtraction.

- Calculation: Plot the absorbance values of the standards against their known concentrations to generate a standard curve. Use the linear equation from this curve to calculate the Hb concentration in your unknown samples.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Hb Quantification |

|---|---|

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | Lyse red blood cells and form a stable complex with hemoglobin for specific spectrophotometric detection. |

| Potassium Cyanide (KCN) | Forms cyanmethemoglobin in the traditional reference method; highly toxic, requiring careful handling and disposal. |

| Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) | Chelates Cu⁺ ions reduced by proteins in an alkaline medium, forming a purple-colored complex (general protein assay). |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Binds to basic and aromatic amino acid residues in proteins, causing a shift in its absorbance maximum (general protein assay). |

Workflow for Selecting a Hemoglobin Quantification Method

This diagram outlines a logical decision process for choosing the most appropriate Hb quantification method based on your sample composition and requirements.

Experimental Workflow for SLS-Hb Quantification

The following chart details the step-by-step procedure for accurately determining hemoglobin concentration using the SLS-Hb method.

Core Concepts and FAQs

This section addresses frequently asked questions about Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC) and Direct Orthogonal Signal Correction (DOSC), powerful preprocessing algorithms used to enhance multivariate calibration models in spectral analysis.

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between OSC and DOSC?

Both OSC and DOSC are preprocessing techniques designed to remove unwanted, structured noise from spectral data (X) that is orthogonal (unrelated) to the property of interest (Y, e.g., concentration). This process leads to more robust and interpretable predictive models [33] [34].

- OSC (Orthogonal Signal Correction): The original OSC method, introduced by Wold et al., uses an iterative algorithm to find components in X that are orthogonal to Y and account for large variance. A common challenge with this iterative approach is ensuring numerical stability and convergence [33] [35].

- DOSC (Direct Orthogonal Signal Correction): DOSC was developed to provide a theoretically exact solution to the same problem. It is based solely on least squares steps and directly calculates the orthogonal components without relying on iterative convergence, making it a more straightforward and stable method [33].

Q2: Why should I use DOSC/OSC before building a PLS model?

In spectroscopic calibrations, the first few latent variables in a Partial Least Squares (PLS) model often capture large, systematic variations in the spectral data (X) that are unrelated to the target property (Y). This can be caused by physical effects like light scattering or strong solvent backgrounds [33] [35].

- Model Improvement: By removing these Y-orthogonal components upfront, DOSC/OSC helps create a more parsimonious model (one with fewer latent variables) that is easier to interpret.

- Enhanced Prediction: The resulting calibration model often has lower prediction errors and improved robustness, as it focuses on the chemically relevant signal [33] [34] [35].

Q3: I'm working with UV-Vis spectra of plant extracts and have a strong solvent background. Can DOSC help?

Yes, absolutely. Excessive background, such as from water or ethanol in plant extracts, is a classic example of a large variance in X that can mask the weaker signals of active constituents. A study on correcting background in NIR spectra of plant extracts found that OSC was the only effective method for removing this type of excessive background compared to other classical methods like derivative spectroscopy or multiplicative scatter correction (MSC) [35]. DOSC, as a refined version of OSC, is perfectly suited for this task.

Q4: How do I choose the number of OSC/DOSC components to remove?

The number of components is typically determined through cross-validation. You can compare the performance (e.g., Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation, RMSECV) of the final PLS model using an increasing number of OSC components. The optimal number is the one that minimizes the prediction error. It is common practice to remove only one or two components, as these account for the largest structured noise orthogonal to Y [34] [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: PLS model performance does not improve after DOSC.

- Potential Cause 1: Over-correction. You may have removed too many OSC components, inadvertently stripping away information that is correlated with Y.

- Solution: Reduce the number of DOSC components and re-validate the model. The goal is to remove only the dominant systematic noise, not all variance [33] [35].

- Potential Cause 2: The major variance in X is correlated with Y. If the largest sources of spectral variation are genuinely related to your analyte, OSC will not remove them, as it is designed to preserve Y-correlated variance.

- Solution: OSC/DOSC is most beneficial when large, interfering variations exist. If this is not the case, other preprocessing methods (e.g., scaling, derivatives) might be more appropriate [33].

Problem: Unstable OSC components when using the original iterative algorithm.

- Solution: Switch to the DOSC method. A key advantage of DOSC is that it avoids the iterative process found in some early OSC algorithms, which can lead to non-stable solutions. DOSC provides a direct, exact calculation, improving reliability [33].

Problem: How to apply the correction to new, prediction samples.

- Solution: The model defined by the DOSC weights and loadings from your calibration set must be applied to new spectra. This involves projecting the new spectral data onto the previously determined orthogonal components and subtracting them. This ensures the same correction is applied consistently to all future samples [35].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing DOSC for UV-Vis Spectral Analysis

The following workflow provides a detailed methodology for applying DOSC to UV-Vis spectral data to mitigate chemical interferences.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection and Preparation

- Collect your UV-Vis spectral matrix (X) and the corresponding reference analyte concentrations or properties (Y).

- Column Mean Centering: Center both X and Y by subtracting the mean value of each variable (wavelength for X, property for Y). This is a standard prerequisite for DOSC and PLS [33].

DOSC Processing (Calibration Set)

- The goal is to decompose X into a part correlated with Y and a part orthogonal to Y, and then remove the latter.

- Mathematical Execution: a. Make an orthogonal decomposition of Y into the part that can be predicted from X (Ŷ) and the residual (F) [33]. b. Decompose X into two orthogonal parts: one that shares the same range as Ŷ and another that is orthogonal to it [33]. c. On the part of X that is orthogonal to Ŷ, perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to find the principal components that describe the largest variance orthogonal to Y [33]. d. Remove the principal components (typically 1-2) that account for the largest orthogonal variance from the original X matrix to create the corrected matrix, XDOSC.

PLS Modeling

- Build a standard PLS regression model using the corrected data XDOSC and the response Y.

- Use cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out) on the calibration set to determine the optimal number of latent variables (LVs) for the PLS model, preventing overfitting.

Model Application (Prediction)

- For any new sample spectrum, apply the exact same centering parameters and DOSC model (weights/loadings) derived from the calibration set to correct the new spectrum.

- Use the corrected new spectrum and the established PLS model to predict the analyte concentration or property.

Performance Comparison of Background Correction Methods

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of different background correction methods applied to a simulated dataset, as reported in a study on NIR analysis of plant extracts [35]. Performance was evaluated based on the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) of the resulting PLS model.

Table 1: Comparison of Background Correction Method Efficiencies

| Correction Method | Principle | RMSEP (Validation Set) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOSC/OSC | Removes variance in X orthogonal to Y | 5.392 | Highly effective for excessive, complex background | Requires response variable Y |

| First Derivative | Removes flat baseline | 7.521 | Simple, fast | Amplifies high-frequency noise |

| Second Derivative | Removes sloping baseline | 7.450 | Handles linear drift | Amplifies noise further |

| Wavelet Method | Filters specific frequency components | 7.569 | Multi-resolution analysis | Difficult to discriminate signal/background |

| MSC | Corrects scatter using reference | 7.714 | Good for scatter effects | Assumes ideal reference |

| SNV | Row-wise normalization | 7.711 | No reference needed | Can attenuate analyte signal |

| None (Raw Data) | - | 7.548 | - | Model suffers from interference |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Digital Tools for DOSC-PLS Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis spectroscopy; transparent down to ~200 nm. | Essential for UV range studies; plastic or glass cuvettes are not suitable [6]. |

| Spectrophotometer | Instrument to measure absorbance/transmittance of samples across UV-Vis range. | Requires a deuterium lamp (UV) and tungsten/halogen lamp (visible) [6]. |

| Centrifuge / Filter | Removes suspended solids from sample solutions to reduce physical (scattering) interference. | Mitrates light scattering, a common physical interference [3]. |

| Reference Standards | High-purity compounds used to build calibration models (the Y matrix). | Critical for accurate model development. |

| Computational Software | Platform for implementing DOSC/OSC and PLS algorithms. | MATLAB [33], R [36] (with custom scripts), or Python with SciKit-Learn. |

| Column Mean Centering | A mandatory data preprocessing step before applying DOSC or PLS. | Ensures model is built around the data mean, improving stability [33]. |

Integrating spectral data with physical parameters like pH and temperature addresses a critical challenge in spectroscopic analysis. Environmental changes during measurement can significantly affect the spectral characteristics of a sample, leading to reduced prediction accuracy for target analytes [37]. The core principle of data fusion is that a spectrum represents a snapshot of material absorption within a specific physical measurement environment. Physical parameters provide crucial contextual information about this environment [37].

Traditional variable-expansion methods that simply concatenate spectral and physical data often fail because high-dimensional spectral data (hundreds of wavelengths) can mask the contribution of low-dimensional physical data (e.g., a single pH or temperature value) [37]. This technical guide outlines robust methodologies to effectively fuse these different types of data, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of your UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis.

Core Methodology: Similarity-Based Data Fusion

This method shifts the focus from variable-based fusion to sample-based fusion, effectively overcoming the dimensionality mismatch between spectral and physical data [37].

Theoretical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the similarity-based data fusion process:

Mathematical Foundation and Protocol

The process uses Gaussian kernel functions to transform raw data into sample-to-sample similarity matrices [37].

Similarity Computation: For every pair of samples (i) and (j), calculate two separate similarity matrices:

- Spectral Similarity: (d{ij} = \exp\left(-\frac{\|xi - xj\|^2}{2\sigma1^2}\right))