Defining Validation Parameters for Comparative Method Selection: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing validation parameters to guide the selection of comparative methods.

Defining Validation Parameters for Comparative Method Selection: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing validation parameters to guide the selection of comparative methods. It covers foundational principles of method comparison, detailed experimental methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting common issues, and the final validation process against regulatory standards. The guidance synthesizes current best practices to ensure that selected methods yield accurate, precise, and legally defensible data, thereby supporting robust scientific decision-making and regulatory compliance.

Core Principles and Definitions for Robust Method Comparison

In the context of analytical method validation and comparative method selection, understanding and quantifying error is fundamental to ensuring data reliability and scientific integrity. Systematic error, also known as bias, refers to a consistent, repeatable error that leads to measurements deviating from the true value in a predictable direction [1] [2]. Unlike random errors which cause scatter around the true value, systematic errors displace all measurements in the same direction, thus affecting the accuracy of a method—defined as the closeness of agreement between a measured value and its true value [3] [4]. The distinction between these concepts is crucial for researchers, particularly in drug development where methodological biases can significantly impact trial outcomes and regulatory decisions.

Systematic errors arise from identifiable factors such as faulty instrument calibration, improper analytical technique, or imperfect method specificity [3] [4]. These errors cannot be reduced by simply repeating measurements, unlike random errors which average out with sufficient replication. When comparing analytical methods, researchers must therefore prioritize the identification, quantification, and control of systematic errors to make valid comparisons about relative performance. The presence of unaddressed systematic error compromises method validation and can lead to incorrect conclusions about a method's suitability for its intended purpose.

Foundational Concepts: Accuracy, Precision, and Error Classification

Differentiating Accuracy and Precision

In analytical sciences, accuracy and precision represent distinct methodological attributes. Accuracy, as defined, refers to closeness to the true value, while precision describes the closeness of agreement between independent measurements obtained under specified conditions—essentially the reproducibility of the measurement [1] [2]. A method can be precise (yielding consistent, repeatable results) yet inaccurate due to systematic error, or accurate on average but imprecise due to substantial random error [3].

This relationship is visually represented in the diagram below, which illustrates the four possible combinations of these properties:

Classification of Measurement Errors

Measurement errors are broadly classified into three categories:

Systematic Errors: Consistent, reproducible inaccuracies due to factors that bias results in one direction. These include:

Random Errors: Unpredictable fluctuations caused by uncontrollable environmental or instrumental variables. These affect precision but not necessarily accuracy, as they may average out with sufficient replication [1] [3].

Gross Errors: Human mistakes such as incorrect recording, calculation errors, or procedural oversights [4].

Comparative Assessment of Systematic Error Evaluation Methods

The assessment of systematic error employs distinct methodological approaches, each with specific applications, advantages, and limitations. The selection of an appropriate assessment strategy depends on factors including the analytical context, availability of reference materials, and required rigor.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodologies for Assessing Systematic Error and Inaccuracy

| Methodology | Principle | Application Context | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Error Calculation [1] | Calculates the absolute difference between experimental and theoretical values as a percentage of the theoretical value. | Method verification against known standards. | Simple to calculate and interpret; provides immediate measure of deviation. | Requires knowledge of the true value; single measurement may not represent overall method bias. |

| Reference Material/Standard Method Comparison [1] [2] | Compares results from the test method to those from an established reference method or certified reference material. | Method validation and calibration. | Directly assesses accuracy against an accepted reference; foundational to method validation. | Availability and cost of appropriate reference materials; assumes reference method is truly accurate. |

| Statistical Error Quantification (e.g., M-TDC) [5] | Employs specialized algorithms and circuitry (e.g., Magnitude-to-Time-to-Digital Converters) to quantify specific systematic error components like offset and gain. | High-precision instrumentation and engineering applications. | Quantifies individual error sources (offset, gain, phase imbalance); enables targeted compensation. | Requires technical expertise and specialized data processing; can be equipment-intensive. |

| Method of Known Additions (Spike Recovery) | Measures the method's ability to recover a known quantity of analyte added to a sample. | Evaluating method accuracy in complex matrices. | Assesses accuracy in the presence of the sample matrix; helps identify matrix effects. | Does not assess extraction efficiency from native sample; preparation intensive. |

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Error Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessment via Percent Error and Standard Method Comparison

This fundamental protocol is widely used in analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical sciences for initial method validation [1].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Certified Reference Material (CRM) or analyte standard of known purity

- Appropriate solvents and reagents for sample preparation

- Test instrument/methodology under evaluation

- Reference instrument/methodology (if performing comparison)

Procedural Steps:

Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions containing the analyte at concentrations spanning the method's dynamic range, using the Certified Reference Material.

Analysis: Analyze each solution using both the test method and the reference method (if applicable). For a simple percent error calculation, only the test method is used, and results are compared to the known, prepared concentration [1].

Calculation: For each measurement, calculate the percent error using the formula:

Data Analysis: For a method comparison, use statistical tests (e.g., paired t-test, Bland-Altman analysis) to determine if a statistically significant systematic bias exists between the test method and the reference method.

Protocol 2: Quantification of Specific Systematic Error Components in Instrumentation

This advanced protocol, derived from engineering research, demonstrates the precise quantification of specific systematic error components (offset, gain, phase imbalance) in sinusoidal encoders using Magnitude-to-Time-to-Digital Converters (M-TDCs) [5].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Device Under Test (e.g., sinusoidal encoder)

- M-TDC circuit (comprising comparators, integrators, and a microcontroller unit)

- Precision signal generator

- Data acquisition system

Procedural Steps:

Signal Application: Apply a known, controlled input (e.g., a precise angular displacement to an encoder) [5].

Signal Acquisition: Acquire the corresponding output signals. For a sinusoidal encoder, this would be the voltage pairs (Vsin, Vcos) [5].

Digitization: Process the analog output signals through the M-TDC circuit, which converts signal magnitudes into time intervals for high-resolution digitization without requiring a conventional analog-to-digital converter (ADC) [5].

Error Parameter Calculation: Apply the quantification algorithm (e.g., Method I or II from the cited research) to the digitized data to solve for the specific systematic error parameters [5]:

- α, β: DC offset errors in the sine and cosine channels, respectively.

- τ: Amplitude mismatch between channels.

- ψ: Phase imbalance between channels.

Compensation: Use the calculated error parameters in a compensation function within the measurement algorithm to correct subsequent readings, thereby enhancing accuracy [5].

Case Studies in Research and Development

Case Study: Systematic Error Considerations in Alzheimer's Drug Development

The Alzheimer's disease (AD) drug development pipeline for 2025 includes 138 drugs across 182 clinical trials [6]. The high-profile failure of many past AD trials has been partly attributed to methodological systematic errors, including:

- Measurement Errors in Patient Stratification: Inaccurate diagnosis or imperfect biomarker-based patient selection led to enrolling heterogeneous populations, obscuring true treatment effects [6].

- Bias in Clinical Endpoints: The use of cognitive and functional scales susceptible to rater bias and placebo effects introduced systematic measurement error [6].

The contemporary response, as seen in the 2025 pipeline, is a concerted effort to mitigate these errors. This includes the incorporation of biomarkers as primary outcomes in 27% of active trials, which provides more objective, quantitative, and less biased measures of biological effect compared to purely clinical scales [6]. This shift exemplifies how recognizing and controlling for systematic error directly influences trial design and the likelihood of success in drug development.

Case Study: Technological Mitigation of Systematic Errors in Medication Safety

In pharmacy practice, technological advancements are increasingly deployed to control systematic human errors. For example:

- Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Systems reduce systematic errors related to information gaps and flawed clinical reasoning by providing centralized patient data and evidence-based alerts [7].

- Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) systematically prevents errors in patient identification and drug selection, a known source of consistent bias in the medication administration process [7].

These technologies function as systemic checks against historically persistent systematic errors, thereby enhancing overall accuracy in patient care and contributing to a estimated annual global cost savings by reducing medication errors [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Error Assessment

The following table details key materials and tools essential for experiments designed to assess systematic error and inaccuracy.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Systematic Error Assessment

| Item | Specification/Example | Primary Function in Error Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | NIST-traceable standards of known purity and concentration. | Serves as the benchmark "true value" for calculating percent error and assessing method accuracy [1]. |

| Signal Acquisition Hardware | Data acquisition cards (e.g., National Instruments USB-6211), high-resolution ADCs [5]. | Precisely captures analog output from devices under test for subsequent digital analysis of error. |

| Direct Interface Circuits | Custom Magnitude-to-Time-to-Digital Converters (M-TDCs) built with comparators and integrators [5]. | Enables high-resolution quantification of specific systematic error parameters (offset, gain) in instrumentation. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R, Python (SciPy), MATLAB, GraphPad Prism. | Performs statistical comparisons (t-tests, regression) between methods to identify and quantify systematic bias. |

| Reference Methodologies | Pharmacopeial methods (e.g., USP), published standard analytical procedures. | Provides an accepted reference point against which the accuracy of a new or comparative method is evaluated [1] [2]. |

The rigorous assessment of systematic error and inaccuracy is a non-negotiable component of robust analytical and clinical research. As demonstrated, a variety of established and emerging methodologies—from fundamental percent error calculations to sophisticated computational quantification—are available to researchers for this purpose. The selection of an appropriate assessment strategy must be guided by the specific context of the method being validated and the consequences of inaccuracy. The ongoing integration of advanced technologies, including AI and automated error-compensation circuits, promises further enhancements in our ability to identify and control for systematic biases. For the drug development professional, a deep understanding of these principles is critical for designing valid clinical trials, interpreting complex biomarker data, and ultimately bringing effective, safe therapies to market. A method's precision is meaningless without demonstrable accuracy, and accuracy cannot be confirmed without a deliberate and thorough assessment of systematic error.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

- Experimental Protocols for Quantification

- Quantitative Assessment and Data Analysis

- Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

- Conclusion

In scientific research and drug development, reliable data is the foundation upon which all conclusions and decisions are built. The trustworthiness of this data hinges on the quality of the measurement systems used to generate it. Understanding and distinguishing between key validation parameters—accuracy, precision, bias, and repeatability—is therefore not merely academic; it is a critical prerequisite for robust comparative method selection and meaningful research outcomes [8]. A measurement system with poor accuracy can lead to incorrect conclusions about a drug's efficacy, while one with poor precision can obscure real biological signals with excessive noise [9]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these fundamental performance characteristics, complete with experimental protocols and quantitative assessment criteria, to empower researchers in validating their analytical methods.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

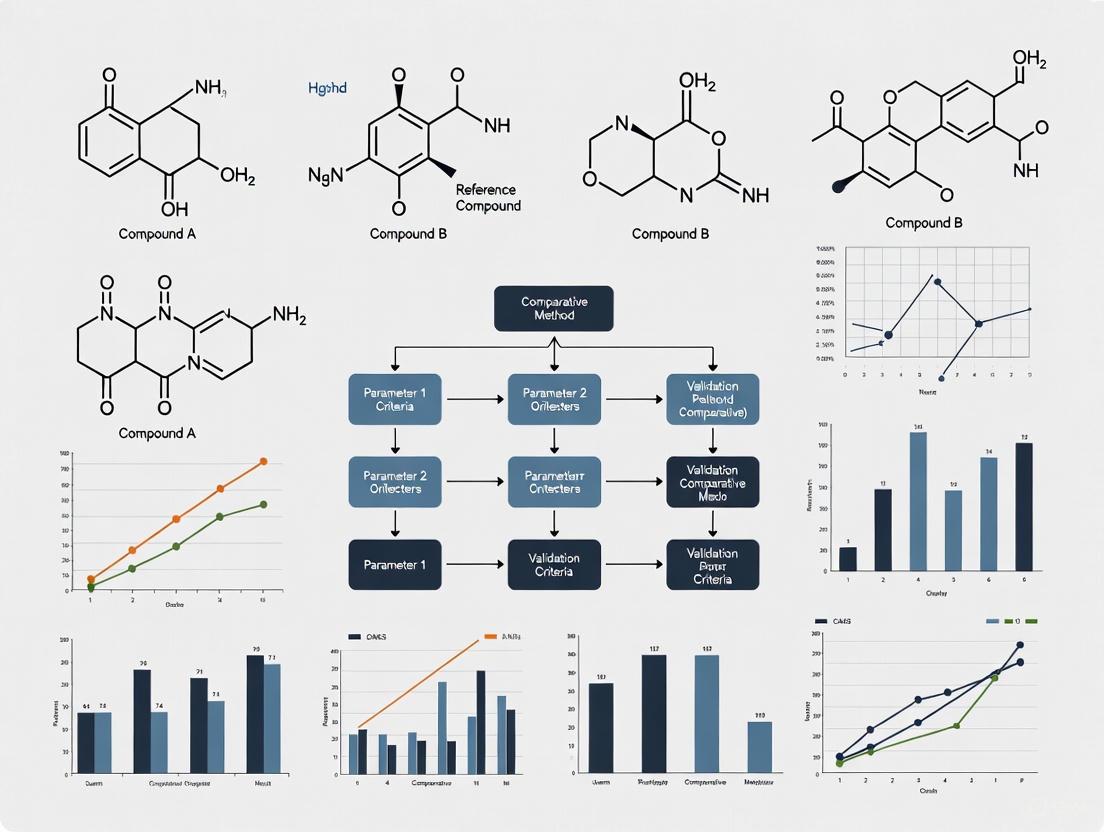

At its core, the quality of a measurement system is evaluated through two principal aspects: its accuracy (closeness to the true value) and its precision (the scatter of repeated measurements) [10]. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these key terms and their components.

Diagram 1: Relationship of key measurement system concepts.

The definitions in the table below provide a clear, standardized foundation for understanding these distinct concepts, which are often conflated.

Table 1: Core Definitions of Key Measurement System Parameters

| Term | Definition | Synonyms / Related Terms | Answers the Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a measured value and the true or accepted reference value [10]. | Trueness (ISO) [10] | Is my measurement, on average, correct? |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between independent measurements of the same quantity under specified conditions [10]. | Reliability, Variability [11] | How much scatter is in my measurements? |

| Bias | The systematic, directed difference between the average of measured values and the reference value [12] [9]. | Systematic Error, Accuracy (in part) | Does my method consistently over- or under-estimate the true value? |

| Repeatability | Precision under a set of conditions that includes the same measurement procedure, same operators, same measuring system, same operating conditions, and same location over a short period of time [12] [11]. | Intra-assay Precision, Test-Retest Reliability | When I measure the same sample multiple times in the same session, how consistent are the results? |

| Reproducibility | Precision under conditions where different operators, measuring systems, laboratories, or time periods are involved [12] [11]. | Inter-lab Precision | Can someone else, or a different instrument, replicate my results? |

It is crucial to recognize that accuracy and precision are independent. A method can be precise but inaccurate (biased), or accurate on average but imprecise [13]. The ideal system is both accurate and precise. The following conceptual diagram illustrates the four possible combinations of these properties.

Diagram 2: Pathways from poor to ideal measurement performance.

Experimental Protocols for Quantification

Moving from concept to practice requires standardized experiments to quantify these parameters. The following protocols are widely adopted across industries, including pharmaceutical development.

Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility (Gage R&R) Study

This experimental design is the gold standard for quantifying the precision of a measurement system by partitioning variation into its repeatability and reproducibility components [12] [9].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for a Gage R&R Study

| Protocol Step | Detailed Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Study Design | Select 2-3 appraisers (operators), 5-20 parts that represent the entire expected process or biological range, and plan for 2-3 repeated measurements per part by each appraiser [9]. | Using too few parts or operators will overestimate the measurement system's capability. Parts must encompass the full range to avoid underestimating error. |

| 2. Blinding & Randomization | Assign a random number to each part to conceal its identity. A third party should record data. Appraisers measure parts in a random order for all trials [9]. | Prevents operator bias from knowing previous results or part identity, ensuring that measured variation is genuine. |

| 3. Measurement Execution | Each appraiser measures all parts once in the randomized order. This process is repeated for the required number of trials, with parts being re-presented in a new random order each time [9]. | Replication under controlled but blinded conditions allows for the isolation of random measurement error (repeatability). |

| 4. Data Analysis | Data is analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to decompose the total variation into components: part-to-part variation, repeatability, and reproducibility [9]. | ANOVA provides a statistically rigorous method to quantify the different sources of variation within the measurement system. |

Bias and Linearity Study

This protocol assesses the accuracy of a measurement system across its operating range.

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for a Bias and Linearity Study

| Protocol Step | Detailed Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Master Sample Selection | Select 5-10 parts or standards that cover the operating range of the measurement device (e.g., low, mid, and high values). The "true" reference value for each part must be known through a more accurate, traceable method [12] [9]. | Assessing bias at multiple points is necessary to determine if the bias is consistent (acceptable) or changes with the magnitude of measurement (linearity issue). |

| 2. Repeated Measurement | Measure each master part multiple times (e.g., 10-20 repetitions) in a randomized order [12]. | Averaging multiple measurements provides a stable estimate of the observed value for each part, reducing the influence of random noise on the bias calculation. |

| 3. Data Analysis | For each part, calculate bias as (Observed Average - Reference Value). Perform a linear regression analysis with bias as the response (Y) and the reference value as the predictor (X) [12]. | The regression analysis quantifies the linearity of the bias. A significant slope indicates that the bias changes as a function of the size of the measurand, which must be corrected for. |

Quantitative Assessment and Data Analysis

Once data is collected from the aforementioned experiments, it is analyzed against established criteria to determine the acceptability of the measurement system.

Assessing Precision: Gage R&R Acceptance Criteria

The results of a Gage R&R study are typically expressed as a percentage of contribution to the total observed variation. The automotive industry action group (AIAG) guidelines are commonly referenced for decision-making [9].

Table 4: Gage R&R Acceptance Criteria (AIAG Guidelines)

| % Gage R&R of Total Variation | Decision | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 10% | Acceptable | The measurement system is considered capable. Variation is dominated by actual part-to-part differences. |

| > 10% to ≤ 30% | Marginal | The system may be acceptable for some applications based on cost, nature of the measurement, etc. Requires expert review. |

| > 30% | Unacceptable | The measurement system has excessive variation and is not suitable for data-based decision-making. Improvement is required [9]. |

Assessing Accuracy: Bias and Linearity Metrics

The output from a bias and linearity study provides specific metrics to quantify accuracy, as demonstrated in a recent study validating quantitative MRCP-derived metrics [14].

Table 5: Quantitative Metrics for Accuracy and Bias Assessment

| Metric | Calculation / Result | Interpretation and Context | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Bias | 0.1253 | The overall average difference between measured values and the reference across all samples. A one-sample t-test can determine if this bias is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) [12]. | ||

| % Linearity | (% Linearity = | Slope | × 100%) | The percentage by which the observed process variation is inflated due to the gage's linearity issue. A smaller value indicates better performance [12]. |

| Absolute Bias (Phantom Study) | 0.0 - 0.2 mm | In a phantom study simulating strictures and dilatations, the absolute bias was sub-millimeter, demonstrating high accuracy. The 95% limits of agreement were within ± 1.0 mm [14]. | ||

| Reproducibility Coefficient (RC) | Ranged from 3.3 to 51.7 for various duct metrics | The RC represents the smallest difference that can be detected with 95% confidence. Lower RCs indicate better reproducibility and greater sensitivity to detecting true change [14]. |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions required for executing the validation experiments described in this guide, with examples from both general metrology and specific biomedical research.

Table 6: Essential Materials for Measurement System Validation Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in Validation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Traceable Reference Standards | Serves as the "ground truth" with a known value for bias assessment and calibration. Crucial for establishing accuracy. | Calibration weights, standard reference materials (SRMs) from national institutes [9]. |

| Stable Master Samples | A representative sample from the process, used for stability assessment over time via control charts. | A part measured to determine its reference value, used for ongoing stability monitoring [9]. |

| 3D-Printed Anatomical Phantoms | Provides a known ground-truth model with realistic geometry to assess measurement accuracy in imaging studies. | A phantom with tubes of sinusoidally-varying diameters used to validate MRCP+ software for biliary tree imaging [14]. |

| Gage R&R Study Kits | A prepared set of parts that represent the entire process spread, used for conducting the Gage R&R study. | 10-20 parts selected from production to cover the full range of process variation [9]. |

| Statistical Software with ANOVA | Performs the complex variance component analysis required for Gage R&R and linear regression for bias studies. | Software tools that automate Gage R&R calculations and produce associated control charts and graphs [9]. |

| Validated Biomarker Assays | A measurement tool with established performance characteristics used as a comparator in method selection research. | IceCube, Nedap Smart Tag, and CowManager sensors were identified as meeting validity criteria (≥85% precision, no bias) in a review of wearable sensors for dairy cattle [15]. |

A rigorous approach to method selection and validation is indispensable for generating reliable scientific data. As demonstrated, the parameters of accuracy, precision, bias, and repeatability are distinct yet interconnected concepts that must be evaluated through structured experimental protocols like Gage R&R and bias studies. The quantitative criteria derived from these studies provide an objective basis for accepting or rejecting a measurement system for its intended use. In the context of drug development and biomarker research, where decisions have significant clinical and financial implications, overlooking this foundational step can lead to failed trials and irreproducible results [8] [9]. Therefore, integrating these validation practices is not a mere technicality but a cornerstone of responsible and effective research.

In the discipline of laboratory medicine, there is consensus that routine measurement procedures claiming the same measurand should give equivalent results within clinically meaningful limits [16]. The comparison of methods experiment is a critical procedure performed to estimate this inaccuracy or systematic error [17]. The fundamental question in such studies is one of substitution: Can one measure a given analyte with either the test method or the comparative method and obtain equivalent results? [18] The selection of an appropriate comparative method—either a reference method or a routine method—forms the foundational decision that impacts all subsequent validation data and conclusions. This guide objectively compares these two approaches to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the evidence needed to make informed decisions within method validation frameworks.

Comparative Analysis: Reference Methods vs. Routine Methods

The analytical method used for comparison must be carefully selected because the interpretation of the experimental results depends on the assumptions that can be made about the correctness of the comparative method's results [17]. The core distinction lies in the documented evidence of accuracy and the resulting attribution of measurement differences.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Reference and Routine Comparative Methods

| Characteristic | Reference Method | Routine Method |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Definition | A high-quality method whose results are known to be correct through comparison with definitive methods and/or traceable standards [17]. | An established method in routine clinical use, whose correctness may not be fully documented [17]. |

| Metrological Traceability | Sits high in the traceability chain; key to establishing metrological traceability of routine methods to higher standards (e.g., SI units) [16]. | Typically lower in the traceability chain; often calibrated using reference methods or materials. |

| Attribution of Error | Any observed differences are assigned to the test (candidate) method [17]. | Observed differences must be carefully interpreted; it may not be clear which method is the source of error [17]. |

| Quality Specifications | Must fulfill "genuine" requirements (e.g., direct calibration with primary reference materials, high specificity) and defined analytical performance specifications [19] [16]. | Performance specifications are typically based on clinical requirements (e.g., biological variation) or manufacturer's claims. |

| Operational Laboratories | Must be performed by laboratories complying with ISO 17025 and ISO 15195, often requiring accreditation and participation in specific round-robin trials [16]. | Operated in routine clinical laboratories following standard good laboratory practices. |

| Ideal Use Case | For unequivocally establishing the trueness (systematic error) of a new candidate method [17]. | For verifying that a new method provides equivalent results to the method currently in use in the laboratory [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison Studies

Regardless of the chosen comparative method, the experimental design must be rigorous to yield reliable estimates of systematic error. The following protocol outlines the key steps, highlighting considerations specific to the choice of comparative method.

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for designing and executing a method-comparison study.

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Specimen Selection and Number: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens should be tested by the two methods [17]. These specimens should be carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the spectrum of diseases expected in its routine application. Twenty well-selected specimens covering a wide concentration range often provide better information than one hundred randomly selected specimens [17]. For a more robust assessment, especially when investigating method specificity, 100 to 200 specimens are recommended [17].

Measurement Protocol: The experiment should include several different analytical runs over a minimum of 5 days to minimize systematic errors that might occur in a single run [17]. A common practice is to analyze each specimen singly by the test and comparative methods. However, performing duplicate measurements—ideally on different samples analyzed in different runs or at least in different order—provides a valuable check for sample mix-ups, transposition errors, and other mistakes [17]. Specimens should generally be analyzed within two hours of each other by the two methods to avoid differences due to specimen instability [17].

Data Analysis Procedures: The analysis involves both graphical and statistical techniques. The data should be graphed as soon as possible during collection to identify discrepant results that need re-analysis while specimens are still available [17].

- Graphical Analysis: For methods expected to show one-to-one agreement, a difference plot (test result minus comparative result versus the comparative result) is ideal for visualizing constant and proportional errors [17]. For methods not expected to agree one-to-one, a comparison plot (test result versus comparative result) is more appropriate [17].

- Statistical Analysis: For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression statistics (slope, y-intercept, standard error of the estimate, sy/x) are preferred. These allow for the estimation of systematic error (SE) at critical medical decision concentrations (Xc) using the formula: Yc = a + bXc, and then SE = Yc - Xc [17]. The correlation coefficient (r) is more useful for assessing whether the data range is wide enough for reliable regression (r ≥ 0.99) than for judging method acceptability [17]. For a narrower analytical range, calculating the average difference (bias) via a paired t-test is usually best [17]. The Bland-Altman plot (difference between methods vs. average of the two methods) is a highly recommended technique for assessing agreement, as it visually presents the bias (mean difference) and the limits of agreement (bias ± 1.96 standard deviation of the differences) [18].

Essential Reagents and Materials for Method Validation Studies

The table below details key reagents and materials required for conducting a robust method-comparison study.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Method Comparison

| Item | Function / Purpose | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Specimens | To provide a matrix-matched, real-world sample for comparing the test and comparative methods. | Should cover the entire analytical range and include pathological states [17]. Stability must be ensured [17]. |

| Primary Reference Material | Used with a reference method for direct calibration, establishing metrological traceability [16]. | For reference methods, this is a genuine requirement; purity and commutability are critical [19] [16]. |

| Processed Calibrators | To calibrate both the test and routine comparative methods before the experiment. | Values should be traceable to a higher-order reference. Lot-to-lot variation should be monitored [20]. |

| Quality Control Materials | To monitor the stability and performance of both methods during the data collection period. | Should include at least two levels (normal and pathological); used to verify precision [17]. |

| Reagent Lots | The specific chemical reactants required for the analytical measurement. | New reagent lots for the test method should be documented; comparison of reagent lots is a common study goal [20]. |

The choice between a reference method and a routine method as the comparator hinges on the fundamental goal of the validation study. Selecting a reference method is the definitive approach for establishing the trueness of a new candidate method and anchoring its results within an internationally recognized traceability chain [17] [16]. This is the ideal choice for the initial validation of a novel method or when claiming metrological traceability. In contrast, comparing a new method to an established routine method answers a more practical clinical question: will the new method yield results that are equivalent to the one currently in use, thereby avoiding disruptive changes to clinical decision thresholds? [18] This pragmatic approach is common when replacing an old analyzer or verifying a new reagent lot. By understanding the distinct applications, strengths, and limitations of each approach—and by implementing a rigorous experimental protocol—researchers can generate defensible data to support confident decisions in the drug development and clinical testing pipeline.

In the highly regulated world of pharmaceutical development, the selection and validation of an analytical method are not merely procedural steps; they are critical strategic decisions that directly impact a product's safety, efficacy, and time-to-market. The principle that the method's performance must be rigorously linked to its intended use is foundational to this process. A method designed for stability-indicating purposes, for instance, demands a different scope of validation than one used for in-process testing. This guide provides a structured, comparative framework for selecting and validating analytical methods, underpinned by experimental protocols and data presentation tailored for drug development professionals. By objectively comparing validation approaches, this article aims to equip scientists with the tools to define a method's scope with precision and scientific rigor, ensuring compliance with evolving regulatory standards like the forthcoming ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 [21].

### The Foundation: Validation Parameters & Their Intended Use

The validation parameters required for an analytical method are directly dictated by its application. A one-size-fits-all approach is neither efficient nor compliant. The following table summarizes how the intended use of a method determines the necessary validation experiments, framing them within the broader validation lifecycle [21].

Table 1: Linking Method Performance to Intended Use: A Validation Parameter Guide

| Validation Parameter | Stability-Indicating Method | Potency Assay (Release Testing) | Impurity Identification | In-Process Control (IPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | Mandatory (Must demonstrate separation from degradation products) | Mandatory (Must demonstrate separation from known impurities) | Mandatory (Primary parameter; e.g., via HRMS) | Conditionally Required (Depends on process stream complexity) |

| Accuracy | Mandatory (Across the range, including degraded samples) | Mandatory (For the active ingredient) | Not Typically Applicable | Recommended (For the measured attribute) |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory (System suitability) | Sufficient for process decision |

| Intermediate Precision/Ruggedness | Mandatory | Mandatory | Recommended | Often not required |

| Linearity & Range | Mandatory (Wide range to cover degradation) | Mandatory (Established around specification) | Mandatory (For semi-quantitative estimation) | Sufficient range for process variation |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | Conditionally Required (For low-level impurities) | Not Typically Required | Mandatory | Not Typically Required |

| Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | Mandatory (For specified impurities) | Not Typically Required | Mandatory (For reporting thresholds) | Not Typically Required |

| Robustness | Highly Recommended | Mandatory | Highly Recommended | Conditionally Required |

This risk-based approach to validation, as outlined in ICH Q14, ensures that resources are allocated efficiently while fully supporting the method's claim. For example, a stability-indicating method requires rigorous demonstration of specificity towards degradation products, while an IPC method may prioritize speed and robustness over the ability to detect trace impurities [21].

### Comparative Experimental Design: A Case Study on HPLC Method Development

To illustrate the practical application of these principles, consider the development of a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method for a new small molecule drug substance. The method must serve two distinct purposes: as a potency assay for release and a related substances method for stability studies. The experimental protocols below are designed to compare different methodological approaches objectively.

### Experimental Protocol 1: Specificity Forced Degradation Study

Objective: To demonstrate the method's ability to accurately measure the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, forced degradation products, and excipients [21].

Sample Preparation:

- Acid Degradation: Treat the drug substance with 0.1M HCl at 60°C for 1 hour. Neutralize.

- Base Degradation: Treat the drug substance with 0.1M NaOH at 60°C for 1 hour. Neutralize.

- Oxidative Degradation: Treat the drug substance with 3% H₂O₂ at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Thermal Degradation: Expose the solid drug substance to 70°C for 1 week.

- Photolytic Degradation: Expose the solid drug substance to UV and visible light as per ICH Q1B.

- Control: Prepare a untreated standard solution.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18, 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Formic acid in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 25 minutes

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV Diode Array Detector (DAD), 210-400 nm

- Injection Volume: 10 µL

Data Analysis: Chromatograms of stressed samples are compared to the control. The method is deemed specific if the analyte peak is pure (as confirmed by DAD peak purity assessment) and baseline separated from all degradation peaks.

### Experimental Protocol 2: Precision & Accuracy Study for Potency

Objective: To determine the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements and the true value (accuracy) and the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions (precision) [21].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of the drug substance reference standard.

- Prepare nine sample preparations at three concentration levels (80%, 100%, and 120% of the target assay concentration) in triplicate, spiked into a placebo mixture.

Chromatographic Conditions: Use the isocratic mode derived from the specificity study for the main peak assay.

Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the percent recovery for each prepared concentration. The mean recovery should be between 98.0% and 102.0%.

- Precision (Repeatability): Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the nine measurements. The RSD should be ≤ 2.0%.

### Comparative Data Presentation: Objective Performance Evaluation

The quantitative data generated from the experimental protocols should be summarized into clearly structured tables for objective comparison. This practice is crucial for communicating complex datasets efficiently [22] [23].

Table 2: Specificity Profile of Candidate HPLC Methods Under Forced Degradation

| Degradation Condition | Method A (Proposed Gradient) | Method B (Legacy Isocratic) |

|---|---|---|

| Acid Degradation | Peak Purity Pass; Resolution from main peak: 4.5 | Peak Purity Fail; Co-elution observed |

| Base Degradation | Peak Purity Pass; Resolution from main peak: 3.8 | Peak Purity Pass; Resolution from main peak: 1.2 |

| Oxidative Degradation | Two degradation products resolved (Rs > 2.0) | Three degradation products, one co-elutes with main peak |

| Main Peak Purity (All conditions) | Pass | Fail (Acid & Oxidative) |

Table 3: Precision and Accuracy Data for Potency Assay (n=9)

| Spiked Level (%) | Method A (Proposed) | Method B (Legacy) |

|---|---|---|

| 80% - Mean Recovery (%) | 99.5 | 101.2 |

| 100% - Mean Recovery (%) | 100.1 | 102.5 |

| 120% - Mean Recovery (%) | 99.8 | 103.1 |

| Repeatability (%RSD) | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Conclusion | Meets acceptance criteria | Fails accuracy at upper levels |

The data clearly demonstrates that Method A is superior for its intended use as a stability-indicating potency assay, while Method B lacks the necessary specificity and accuracy.

### Visualizing the Method Selection Workflow

A logical, structured workflow is essential for robust method selection. The following diagram outlines the critical decision points, from defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) to the final method validation, ensuring the scope is always linked to the intended use [21].

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of robust analytical methods relies on high-quality materials and instrumentation. The following table details key resources essential for the development and validation of chromatographic methods as discussed in this guide [21].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Development & Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for identifying the analyte peak and for quantifying accuracy, linearity, and potency. |

| Chromatography Columns (C18, C8, etc.) | The stationary phase responsible for the separation of the analyte from impurities and degradation products; critical for specificity. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Solvents | Ensure low UV background and minimal ion suppression for sensitive and reproducible detection, especially in LC-MS/MS. |

| Forced Degradation Reagents (e.g., HCl, NaOH, H₂O₂) | Used in stress studies to intentionally generate degradation products and prove the stability-indicating power of the method. |

| Validated Spreadsheet Software / CDS | For statistical calculation of validation parameters (mean, RSD, regression analysis) with built-in data integrity controls (ALCOA+). |

| Diode Array Detector (DAD) | Enables the collection of spectral data across a wavelength range, which is crucial for confirming peak purity in specificity studies. |

| pH Buffers & Mobile Phase Additives | Modify the mobile phase to control ionization, retention, and peak shape, directly impacting method robustness and selectivity. |

Defining the scope of an analytical method is a deliberate, science-driven process that inextricably links performance characteristics to the method's intended use. As demonstrated through comparative experimental data and structured workflows, a one-size-fits-all validation strategy is untenable. A stability-indicating method demands a broader, more rigorous scope—particularly in specificity—than an in-process control method. The trends outlined in ICH Q14 and the adoption of a formal Analytical Procedure Lifecycle approach reinforce this paradigm, moving the industry toward more robust and flexible methods. By adhering to these principles and utilizing a structured toolkit, scientists and drug development professionals can make objective, defensible decisions in comparative method selection, ultimately ensuring product quality and accelerating the delivery of safe and effective therapies to patients.

Designing and Executing a Method-Comparison Experiment

Within the rigorous framework of comparative method selection research, the validation of a new analytical method hinges on the demonstration of its accuracy and reliability against a established comparative method. The cornerstone of this validation process is a well-designed comparison of methods experiment, where the inherent properties of the patient specimens used--their selection, number, and stability--directly influence the credibility of the systematic error estimates obtained. Proper experimental design in this phase is critical for generating data that can robustly support claims about a method's performance, ensuring that subsequent decisions in drug development or clinical practice are based on solid evidence [17] [8]. This guide outlines the core principles and detailed protocols for designing this critical experiment, providing researchers with a structured approach to specimen management.

Specimen Selection and Number: Protocols and Data

The foundation of a successful comparison study lies in the strategic selection and adequate number of patient specimens. These factors determine how well the experiment captures the method's performance across its intended operating range and in the presence of real-world sample variations.

Experimental Protocol for Specimen Selection and Procurement

Objective: To acquire a set of patient specimens that accurately represent the entire working range of the method and the spectrum of diseases and conditions the method will encounter in routine use [17].

Methodology:

- Define the Analytical Range: Establish the low, high, and medically relevant decision levels for the analyte. Specimens should be selected to cover this entire range uniformly, rather than relying on randomly received samples.

- Identify Sample Sources: Procure leftover patient specimens from routine laboratory testing that fall within the desired concentration intervals.

- Ensure Sample Diversity: Deliberately include specimens from a diverse patient population, representing various pathophysiological conditions (e.g., different diseases, renal or hepatic impairment) that might be encountered in clinical practice. This helps test the method's specificity.

- Avoid Interference: If the new method uses a different chemical principle, be aware that individual sample matrices may cause interference. Specimens showing large discrepancies in initial testing should be investigated for potential interferences [17].

Quantitative Guidelines for Specimen Number

The appropriate number of specimens is a balance between statistical reliability and practical feasibility. The following table summarizes key recommendations:

Table 1: Recommendations for Number of Specimens in Comparison of Methods Experiment

| Factor | Minimum Recommendation | Enhanced Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Specimens | 40 specimens [17] | 100 to 200 specimens [17] | A minimum of 40 provides a baseline for estimating systematic error. A larger number (100-200) is superior for assessing method specificity and identifying matrix-related interferences. |

| Data Distribution | Cover the entire working range [17] | Evenly distributed across the analytical measurement range | A wide range of concentrations is more critical than a large number of specimens clustered in a narrow range. It enables reliable linear regression analysis. |

| Analysis Schedule | Analyze specimens over a minimum of 5 days [17] | Extend over 20 days (2-5 specimens/day) [17] | Analysis across multiple days and analytical runs helps minimize systematic biases that could occur in a single run and provides more realistic precision estimates. |

Specimen Stability and Handling: Protocols and Data

Specimen stability is a critical variable that, if not controlled, can introduce pre-analytical error that is misattributed to the analytical method itself. A detailed protocol is essential to ensure observed differences are due to the methods being compared, and not specimen degradation.

Experimental Protocol for Specimen Stability and Handling

Objective: To ensure that all patient specimens remain stable throughout the testing process, thereby guaranteeing that results from both the test and comparative method reflect the true analyte concentration at the time of sampling.

Methodology:

- Define Stability Limits: Prior to the study, consult literature or perform preliminary tests to establish the stability of the analyte in the sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma) under various storage conditions (room temperature, refrigerated, frozen).

- Synchronize Analysis: Analyze each patient specimen by the test method and the comparative method within two hours of each other [17]. This minimizes time-dependent degradation as a source of error.

- Standardize Handling: Define and systematize specimen handling procedures prior to study initiation. This includes:

- Centrifugation: Time and speed for serum/plasma separation.

- Aliquoting: Use of preservatives if necessary.

- Storage: Conditions (e.g., refrigeration at 4°C, freezing at -20°C or -70°C) for specimens not analyzed immediately.

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Limit the number of freeze-thaw cycles, as this can degrade many analytes.

- Document Procedures: Document all handling and storage steps meticulously to ensure consistency and for future reference.

Stability Considerations for Common Analytes

Table 2: Specimen Stability and Handling Considerations for Common Analytes

| Analyte Category | Stability Considerations | Recommended Handling Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| General Chemistry | Many stable for hours at room temp, days refrigerated. | Analyze within 2 hours or separate serum/plasma and refrigerate if analysis is delayed. |

| Labile Analytes (e.g., Ammonia, Lactate) | Highly unstable at room temperature. | Place samples on ice immediately after collection and analyze within 30 minutes. |

| Proteins & Enzymes | Generally stable for longer periods. | Refrigerate for short-term storage; freeze at -20°C or lower for long-term preservation. |

Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow for the comparison of methods experiment, integrating the principles of specimen selection, stability, and subsequent data analysis.

Comparison of Methods Experimental Workflow

Data Analysis Protocol

Objective: To graphically and statistically analyze the paired data to identify outliers, understand the relationship between methods, and estimate the systematic error of the test method [17].

Methodology:

- Graphical Inspection:

- Difference Plot: Plot the difference between the test and comparative method results (test - comparative) on the y-axis against the comparative method result on the x-axis. This helps visualize constant and proportional errors and identify outliers [17].

- Comparison Plot: Plot the test method result (y-axis) against the comparative method result (x-axis). Draw a visual line of best fit. This is useful for methods not expected to show 1:1 agreement.

- Action: Identify and reanalyze any discrepant results while specimens are still available.

- Statistical Calculations:

- For Wide Analytical Ranges: Use linear regression (least squares) to calculate the slope (b) and y-intercept (a) of the regression line (Y = a + bX). The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated as: SE = Yc - Xc, where Yc = a + bXc [17].

- For Narrow Analytical Ranges: Calculate the average difference (bias) between the two methods using a paired t-test. The standard deviation of the differences describes the distribution of these differences [17].

- Correlation Coefficient (r): Use primarily to assess if the data range is wide enough for reliable regression analysis (r ≥ 0.99 is desirable) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and solutions essential for conducting a robust comparison of methods experiment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Comparison Studies

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Well-Characterized Patient Pool | Leftover, de-identified patient specimens covering the analytical measurement range. Serves as the primary resource for assessing method performance with real-world matrices. |

| Reference Method or Material | A high-quality method with documented correctness or Standard Reference Material (SRM) traceable to a definitive method. Used as the comparator to assign error to the test method [17]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Stable control materials at multiple levels (e.g., normal, abnormal). Used to monitor the precision and stability of both the test and comparative methods throughout the study period. |

| Calibrators | Materials of known concentration used to calibrate both analytical instruments. Ensures both methods are standardized against the same traceable basis before specimen analysis. |

| Specialized Collection Tubes | Tubes containing appropriate preservatives (e.g., fluoride/oxalate for glucose) or stabilizers (e.g., protease inhibitors) for labile analytes. Maintains analyte integrity from collection to analysis [17]. |

In the scientific method, the integrity of experimental data is paramount. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, decisions regarding data collection strategies are foundational to robust comparative method selection and validation. A critical aspect of this planning involves determining the appropriate number of technical replicates—single, duplicate, or triplicate measurements—and constructing a realistic timeframe for the data collection process. This guide objectively compares these measurement approaches, providing supporting experimental data and contextualizing them within the broader framework of validation parameters for research. The choice between these strategies represents a fundamental trade-off between statistical power, resource efficiency, and error management, all of which directly impact the validity and reliability of research outcomes.

Understanding Replicates: Biological vs. Technical

Experimental science vitally relies on replicate measurements and their statistical analysis. However, not all replicates are created equal, and understanding their distinction is crucial for proper experimental design [24].

- Biological Replicates are distinct samples from different biological specimens (e.g., blood samples from various individual patients, or multiple mice in a study). They are essential for controlling for natural biological variability and form the bedrock of sound statistical analysis that allows for generalization to a population [25] [24].

- Technical Replicates are repetitions of the technical, experimental procedure using the same biological sample (e.g., running the same test multiple times with the same sample). They primarily serve to determine and control for the variability introduced by the method itself, such as pipetting inaccuracies or instrument noise [25].

A common and critical error in scientific research is misusing technical replicates to draw biological inferences. As demonstrated in a bone marrow colony experiment, using ten replicate plates from a single mouse pair (technical replicates) to calculate statistical significance (P < 0.0001) creates a false impression of robustness. In reality, since all replicates came from the same biological source, the experiment only represents a single biological comparison (n=1) and cannot support generalized conclusions about the mouse genotypes [24]. Technical replicates monitor experimental performance, but cannot provide evidence for the reproducibility of the main biological result [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Replicate Types

| Feature | Biological Replicates | Technical Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measurements from distinct biological sources | Repeated measurements from the same biological sample |

| Primary Purpose | Account for natural biological variability; allow generalization | Assess and control methodological variability |

| What they test | The hypothesis across a population | The precision of the assay itself |

| Statistical Power | Increase n for statistical inference |

Do not increase n for biological inference |

| Example | Using cells from 10 different human donors | Measuring the same sample solution 3 times in the same assay |

Comparative Analysis: Single, Duplicate, and Triplicate Measurements

The number of technical replicates per sample is a key decision point, balancing data quality with practical constraints like cost, time, and sample availability.

Single Measurements

Single measurements, using one well or test per sample, maximize throughput and resource efficiency [25].

- Pros: Allows for the maximum number of samples to be measured with a given assay. Ideal for high-throughput applications where testing a large sample volume is the priority, such as in quality control of biological manufacturing [25].

- Cons: The most significant drawback is the inability to identify outliers or erroneous data points. Faulty measurements will go unnoticed, potentially compromising the entire dataset [25].

- Ideal Use Cases:

- Qualitative or semi-quantitative analyses where results are positive/negative [25].

- Time-course experiments where samples from the same source are measured at intervals, allowing outliers to be identified relative to other time points [25].

- Studies where cohorts are large enough that individual errors do not compromise group mean analysis [25].

Duplicate Measurements

Duplicate measurements are widely considered the "sweet spot" for many applications, including ELISA, offering a practical compromise between error management and throughput [25].

- Pros: Enables a level of error compensation by calculating a mean of two values. Crucially, it allows for the detection of measurement deviations by calculating variability (%CV or standard deviation) between the two replicates [25].

- Cons: While duplicates can identify high variability, they cannot reliably correct for it. If the %CV exceeds a predefined threshold (commonly 15-20%), the sample should be disregarded and remeasured, as there is no systematic way to identify which of the two measurements is faulty [25].

- Ideal Use Cases: The recommended approach for the vast majority of quantitative assays where a balance of accuracy and efficiency is required [25].

Triplicate Measurements

Triplicate measurements provide the highest level of precision and error control at the cost of significantly reduced throughput and higher reagent use [25].

- Pros: The mean from triplicates is significantly more likely to represent the true value. Most importantly, triplicates allow for both error identification and correction. Outliers can be identified against the mean and excluded, allowing the sample to be quantified based on the remaining two measurements [25].

- Cons: Reduces throughput capacity by a third and uses more resources per sample [25].

- Ideal Use Cases: Indicated when data precision is paramount, or when working with rare or valuable samples where remeasurement may not be an option [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Single, Duplicate, and Triplicate Measurement Strategies

| Feature | Single Measurement | Duplicate Measurements | Triplicate Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Highest | Moderate | Lowest |

| Resource Efficiency | Highest | Moderate | Lowest |

| Error Detection | No | Yes | Yes |

| Error Correction | No | No | Yes (via outlier exclusion) |

| Best For | Qualitative screening, high-throughput | Most quantitative assays, ideal balance | Maximum precision, critical quantification |

| Data Analysis | Group means (large cohorts only) | Mean of two; exclude sample if %CV high | Mean of two or three; exclude outliers systematically |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Example Protocol: Bone Marrow Colony Assay

The following methodology, adapted from a study on the protein Biddelonin (BDL), illustrates the proper use of replicates [24].

- Objective: To test the hypothesis that BDL is required for a full response of bone marrow colony-forming cells to the cytokine HH-CSF.

- Materials:

- Wild-type (WT) and homozygous Bdl gene-deleted mice.

- Recombinant HH-CSF cytokine.

- Soft agar growth medium, 35 x 10 mm Petri dishes.

- Hemocytometer or flow cytometer for cell counting.

- Dissecting microscope.

- Method:

- Prepare bone marrow cell suspensions from a WT mouse and a Bdl−/− mouse (littermates).

- Adjust cell suspensions to a concentration of 1 × 10^5 cells per milliliter.

- Add 1 ml aliquots of the cell suspension to ten Petri dishes per condition.

- Add 10 µl of either saline (control) or HH-CSF to the respective plates, creating four sets:

- Set 1: WT cells + saline

- Set 2: Bdl−/− cells + saline

- Set 3: WT cells + HH-CSF

- Set 4: Bdl−/− cells + HH-CSF

- Incubate plates for one week.

- Count the number of colonies (>50 cells) per plate using a dissecting microscope.

- Data Analysis: The ten plates per condition are technical replicates. They provide a robust mean value for the response of that single biological replicate (one mouse of each genotype). To draw a biologically valid conclusion, the entire experiment must be repeated multiple times using different mice (biological replicates) [24].

Table 3: Sample Data from Bone Marrow Colony Assay (Colonies per Plate) [24]

| Plate Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT + Saline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.42 |

| Bdl−/− + Saline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.67 |

| WT + HH-CSF | 61 | 59 | 55 | 64 | 57 | 69 | 63 | 51 | 61 | 61 | 60.1 | 4.73 |

| Bdl−/− + HH-CSF | 48 | 34 | 50 | 59 | 37 | 46 | 44 | 39 | 51 | 47 | 45.5 | 7.47 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Materials and Their Functions in Cell-Based Assays

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Biological Model (e.g., Mice) | Provides the biological system to test the hypothesis; using multiple animals is the source of biological replicates. |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors (e.g., HH-CSF) | The active molecule being tested to elicit a specific cellular response. |

| Cell Culture Medium (e.g., Soft Agar) | Provides the necessary nutrients and environment for cells to grow and proliferate. |

| Cell Counting Device (e.g., Hemocytometer) | Ensures accurate and consistent cell numbers are plated across all experiments, a key step in technical precision. |

| Imaging/Analysis Instrument (e.g., Microscope) | Used to quantify the experimental endpoint (e.g., colony count) in an objective and measurable way. |

Crafting a Realistic Data Collection Timeline

A well-planned timeline is a roadmap to successful research execution, ensuring feasibility and maintaining the quality and integrity of the study [26]. Key factors to consider include:

- Assessing the Study's Scope: Evaluate the extent of data collection. Consider the methods used (surveys, interviews, experimental methods), availability of resources (equipment, lab space), and the number of biological and technical replicates required. Always factor in time for unforeseen delays [26].

- Preparation is Key: This phase involves fine-tuning methods, conducting pilot tests to refine questions and approaches, and ensuring proficiency with equipment. Data storage and management plans should also be established during this time [26].

- Flexibility and Adaptation: Research is inherently unpredictable. A successful timeline is well-planned yet adaptable, allowing for adjustments in response to challenges while maintaining open communication with supervisors or team members [26].

To create an effective timeline, researchers should:

- Create a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) by breaking the project into smaller, manageable tasks.

- Identify dependencies between tasks to sequence them correctly.

- Establish clear milestones to track progress.

- Use project management tools to visualize and enforce the timeline [26].

Visual Workflows and Decision Diagrams

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting a measurement strategy, incorporating both technical and biological replicate considerations.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting measurement approaches and ensuring robust design.

In comparative method selection research, graphical data analysis serves as the critical first step for assessing method agreement and identifying potential biases. Difference plots and scatter diagrams provide visual means to evaluate whether two analytical methods could be used interchangeably without affecting patient results or scientific conclusions [27]. These tools are indispensable in method validation, allowing researchers to detect patterns, trends, and outliers that might not be apparent through statistical analysis alone [28] [27].

The quality of method comparison studies determines the validity of conclusions, making proper experimental design and graphical presentation essential components of analytical research [27]. This guide examines the complementary roles of scatter diagrams and difference plots within a comprehensive method validation framework, providing researchers with practical protocols for implementation and interpretation.

Comparative Analysis of Primary Graphical Methods

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Scatter Plots and Difference Plots

| Characteristic | Scatter Plot | Difference Plot |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Visualizes relationship between two methods across measurement range [29] | Displays agreement between methods by plotting differences against a reference [27] |

| Axes Configuration | Test method (y-axis) vs. reference/comparison method (x-axis) [29] | Differences between methods (y-axis) vs. average values or reference method (x-axis) [27] |

| Bias Detection | Identifies constant and proportional bias through visual pattern assessment [29] | Directly visualizes magnitude and pattern of differences across measurement range [17] |

| Ideal Relationship | Data points fall along identity line (y = x) [29] | Differences scatter randomly around zero line with no systematic pattern [27] |

| Data Variability Assessment | Shows whether variability is constant (constant SD) or value-dependent (constant CV) [29] | Reveals whether spread of differences remains consistent across measurement range [17] |

| Outlier Identification | Visual detection of points deviating from overall relationship pattern [27] | Direct visualization of differences exceeding expected agreement limits [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison Studies

Specimen Selection and Handling

A properly designed method comparison experiment requires careful specimen selection and handling protocols. Researchers should select a minimum of 40 patient specimens, though 100 specimens are preferable to identify unexpected errors due to interferences or sample matrix effects [17] [27]. Specimens must be carefully selected to cover the entire clinically meaningful measurement range rather than relying on random selection [17] [27].

Temporal factors significantly impact results validity. Specimens should be analyzed within 2 hours of each other by test and comparative methods to prevent degradation, unless specific preservatives or handling methods extend stability [17]. The experiment should span multiple days (minimum of 5) and include multiple analytical runs to mimic real-world conditions and minimize systematic errors from a single run [17] [27].

Measurement Procedures

For measurement protocols, duplicate measurements are recommended for both current and new methods to minimize random variation effects [17] [27]. If duplicates are performed, the mean of two measurements should be used for plotting; with three or more measurements, the median is preferred [27]. Sample sequence should be randomized to avoid carry-over effects, and all samples should ideally be analyzed on the day of collection [27].

When differences between methods are observed, researchers should implement a protocol for immediate graphical inspection during data collection to identify discrepant results while specimens remain available for reanalysis [17]. This proactive approach confirms whether observed differences represent true methodological variance or procedural errors.

Statistical Analysis Following Graphical Inspection

While graphical methods provide initial assessment, statistical calculations quantify systematic errors. For data spanning a wide analytical range, linear regression statistics are preferred, providing slope (b), y-intercept (a), and standard deviation of points about the line (sy/x) [17]. The systematic error (SE) at critical decision concentrations is calculated as: Yc = a + bXc, then SE = Yc - X_c [17].

For narrow analytical ranges, researchers should calculate the average difference (bias) between methods along with the standard deviation of differences [17]. Correlation analysis alone is inadequate for method comparison as it measures association rather than agreement, and similarly, t-tests often fail to detect clinically relevant differences [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for Method Comparison

Table 2: Essential Materials for Method Comparison Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference Method Materials | Provides benchmark with documented correctness through comparative studies with definitive methods or traceable reference materials [17] |

| Patient Specimens (n=40-100) | Serves as test matrix covering clinical measurement range and disease spectrum; must represent actual testing conditions [17] [27] |

| Preservation Reagents | Maintains specimen stability during 2-hour analysis window; may include serum separators, anticoagulants, or stabilizers [17] |

| Quality Control Materials | Verifies proper performance of both test and comparative methods throughout study duration [17] |

| Statistical Software | Facilitates regression analysis, difference calculations, and graphical generation; options include R, Python, SPSS, SAS, or specialized tools [30] |

Workflow Visualization for Graphical Analysis

Graphical Analysis Workflow

Advanced Applications and Interpretation Guidelines

Specialized Difference Plot Applications

Beyond basic difference visualization, specialized applications enhance methodological assessment. The Bland-Altman plot specifically graphs differences between test and comparative method against their average values, incorporating bias lines and confidence intervals to assess agreement limits [31]. When distribution normality is questionable, researchers should supplement difference plots with histograms and box plots of differences to validate statistical assumptions [31].

For methods with differing specificities, difference plots can incorporate statistical assessment of the standard deviation of differences to evaluate aberrant-sample bias potentially indicating matrix effects [28]. These advanced applications transform difference plots from simple visual tools to quantitative assessment instruments.

Visual Interpretation Criteria

Systematic interpretation protocols ensure consistent graphical analysis. For scatter plots, researchers should assess whether points form a constant-width band (indicating constant standard deviation) or a band narrowing at small values (suggesting constant coefficient of variation) [29]. Data crossing the identity line suggests concentration-dependent bias requiring further investigation [31].

Difference plot interpretation focuses on random scatter around zero without systematic patterns [27]. The presence of trends (e.g., differences increasing with concentration magnitude) indicates proportional bias, while consistent offset above or below zero suggests constant bias [17]. Outliers should be investigated for potential methodological interferences or specimen-specific issues [27].

Difference plots and scatter diagrams provide complementary visual approaches for initial method comparison assessment. When implemented according to standardized experimental protocols with appropriate specimen selection and statistical validation, these graphical tools form the foundation of rigorous method validation frameworks. Their continued relevance in pharmaceutical research and clinical science stems from their unique ability to transform complex methodological relationships into intuitively accessible visual information, guiding researchers toward appropriate statistical testing and ultimately supporting robust comparative method selection decisions.

In the field of analytical science and drug development, the selection and validation of analytical methods is a critical process that ensures the reliability, accuracy, and precision of measurement data. Statistical calculations form the backbone of this comparative method selection, providing the objective framework needed to make informed decisions about method suitability. Within the context of validation parameters for comparative method selection research, three statistical methodologies emerge as fundamental: linear regression, bias estimation, and correlation analysis. These tools collectively enable researchers to quantify the relationship between methods, estimate systematic errors, and evaluate the strength of agreement, forming a comprehensive statistical toolkit for method comparison studies [17] [18] [32].

The importance of these statistical calculations extends beyond mere analytical convenience; they represent a rigorous approach to demonstrating that a new method performs equivalently to an established one, or that parallel methods can be used interchangeably in clinical or pharmaceutical settings. As regulatory authorities increasingly emphasize data-driven decision making in drug development, the proper application and interpretation of these statistical tools becomes paramount for successful method validation and adoption [33] [34] [32]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental statistical approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to assist researchers in selecting appropriate validation strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Linear Regression Approaches

Linear regression serves as a fundamental statistical tool in method comparison studies, primarily used to model the relationship between measurements obtained from two different methods. When comparing a test method with a comparative method, regression analysis helps characterize both constant and proportional differences between the methods [17].

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression

The OLS approach estimates the regression coefficients by minimizing the sum of squared vertical distances between observed data points and the fitted regression line. For a method comparison study, the model takes the form Y = a + bX, where Y represents results from the test method, X represents results from the comparative method, a is the y-intercept (indicating constant difference), and b is the slope (indicating proportional difference) [17] [35]. The OLS estimator is calculated as β̂OLS = (X'X)⁻¹X'y, where X is the matrix of predictor variables and y is the vector of responses [35].

Despite its widespread use, OLS regression performs optimally only when specific assumptions are met: no multicollinearity among predictors, no influential outliers, constant error variance, and correct model specification [35]. Violations of these assumptions, particularly multicollinearity or the presence of outliers, can lead to unstable coefficient estimates with inflated variances, compromising the reliability of method comparison conclusions [35].

Advanced Regression Techniques for Challenging Data Conditions

Ridge Regression: To address multicollinearity issues, ridge regression introduces a bias parameter k to the diagonal elements of the X'X matrix, resulting in the estimator β̂k = (X'X + kI)⁻¹X'y [35]. This approach stabilizes coefficient estimates at the cost of introducing slight bias, often yielding superior performance in mean squared error (MSE) compared to OLS when multicollinearity is present [35].