Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: From Nobel Prize Discovery to Modern Drug Development

This article explores the transformative journey of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), a Nobel Prize-winning technology that revolutionized the analysis of biological macromolecules.

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: From Nobel Prize Discovery to Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative journey of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), a Nobel Prize-winning technology that revolutionized the analysis of biological macromolecules. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we cover foundational principles from its historical origins to the ionization mechanisms that enable the study of proteins and noncovalent complexes. The scope extends to methodological applications in clinical diagnostics and drug discovery, addresses troubleshooting for sensitivity and quantification, and provides a comparative analysis with other ionization techniques. By synthesizing current trends and future directions, this article serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging ESI-MS in biomedical research.

The Genesis of a Revolution: Uncovering the History and Core Principles of ESI-MS

The invention of electrospray ionization (ESI) for mass spectrometry represents a pivotal breakthrough in analytical chemistry, fundamentally reshaping the study of biological macromolecules. This technical guide traces the historical trajectory of ESI, from its theoretical underpinnings in electrostatic theory to its maturation as an indispensable tool in modern laboratories. The development of ESI was not a singular event but an evolutionary process spanning more than a century, culminating in John B. Fenn's 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This innovation successfully addressed the long-standing challenge of transferring large, nonvolatile, and thermally labile biomolecules intact into the gas phase for mass spectrometric analysis, thereby enabling the precise molecular weight determination of proteins and other biological complexes that were previously intractable to mass analysis. The technique's core breakthrough lies in its ability to produce multiply charged ions from macromolecules, effectively extending the mass range of conventional mass spectrometers and creating a gateway to the field of proteomics.

Theoretical Foundations: The Electrospray Phenomenon

The electrospray process is governed by the fundamental principles of electrostatics and fluid dynamics. The theoretical foundation was established in 1882 when Lord Rayleigh first calculated the maximum amount of charge a liquid droplet could carry before becoming unstable and ejecting fine jets of liquid—a threshold now known as the Rayleigh limit [1].

The phenomenon was further advanced through the work of Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, who described the formation of the Taylor cone in 1964 [2]. Taylor demonstrated that when an electrical potential is applied to a liquid, it forms a cone with a specific angle of 49.3° at equilibrium, where electrostatic forces precisely counterbalance surface tension [2]. This theoretical framework provided the critical understanding necessary for controlled electrospray operation.

The electrospray mechanism involves applying a high voltage (typically 2-6 kV) to a liquid passing through a metal capillary [3]. This creates a strong electric field that disperses the liquid into a fine aerosol of charged droplets [3]. As these droplets travel toward the mass spectrometer inlet, the solvent evaporates, increasing the charge density on the droplet surface. When droplets reach the Rayleigh limit, Coulomb fission occurs, breaking them into smaller droplets [1]. This process repeats until gaseous ions are liberated for mass analysis [1].

Historical Development and Key Milestones

The evolution of electrospray ionization spans more than a century of theoretical and experimental advancements, culminating in its modern application for biomolecular analysis. The following timeline captures the pivotal milestones in this journey:

Table: Historical Timeline of Electrospray Ionization Development

| Year | Scientist/Group | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1882 | Lord Rayleigh | Theoretical description of the charge limit of droplets [1] | Established fundamental electrostatic principles |

| 1914 | John Zeleny | Documented behavior of fluid droplets under electric fields [1] | Early experimental characterization |

| 1964 | Geoffrey Ingram Taylor | Description of the Taylor cone [2] | Provided theoretical foundation for electrospray process |

| 1968 | Malcolm Dole | First attempt to interface electrospray with mass spectrometry [1] | Conceptual pioneer of ESI-MS |

| 1984 | Masamichi Yamashita & John Fenn; Lidia Gall (independent) | Modern ESI ion source development [1] | Created functional ESI-MS prototypes |

| 1988 | John Fenn's Group | Demonstration of ESI-MS for large proteins [3] | Revolutionized biomolecular analysis |

| 2002 | John B. Fenn | Nobel Prize in Chemistry [4] [5] | Recognition for enabling MS analysis of biological macromolecules |

| 2004 | Zoltan Takats et al. | Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) [6] | Extended ESI to ambient ionization for direct sample analysis |

The modern implementation of ESI began with Malcolm Dole in 1968, who first attempted to interface electrospray with mass spectrometry for analyzing synthetic polymers [1]. However, the transformative breakthrough came in the 1980s when John B. Fenn and colleagues developed a robust ESI source capable of ionizing intact proteins [3]. Their seminal 1988 publication demonstrated that ESI could produce multiple charged ions from proteins, effectively lowering the mass-to-charge ratios to within the detectable range of common mass analyzers [3].

This development coincided with the emergence of proteomics, which created an urgent need for precisely the analytical capabilities that ESI could provide [3]. The technique's impact was so profound that Fenn shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Koichi Tanaka (for MALDI) "for their development of soft desorption ionisation methods for mass spectrometric analyses of biological macromolecules" [5].

The ESI Mechanism: From Liquid Solution to Gas-Phase Ions

The transformation of analytes from liquid solution to gas-phase ions in ESI involves a sophisticated mechanism with several critical stages. Two primary models explain the final stage of ion formation: the Charge Residue Model (CRM) and the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM) [2].

The Charge Residue Model, proposed by Dole, suggests that repeated droplet fission and solvent evaporation eventually produce droplets containing only a single analyte molecule [2]. After the remaining solvent evaporates, the analyte retains the droplet's charge as a gas-phase ion [2]. This mechanism is believed to dominate for large biomolecules such as folded proteins.

In contrast, the Ion Evaporation Model, developed by Iribarne and Thomson, proposes that when droplets reach a sufficiently small size (approximately 20 nm in diameter), the electric field strength at the droplet surface becomes intense enough to field-desorb solvated ions directly into the gas phase [2]. This mechanism is thought to be predominant for smaller ions.

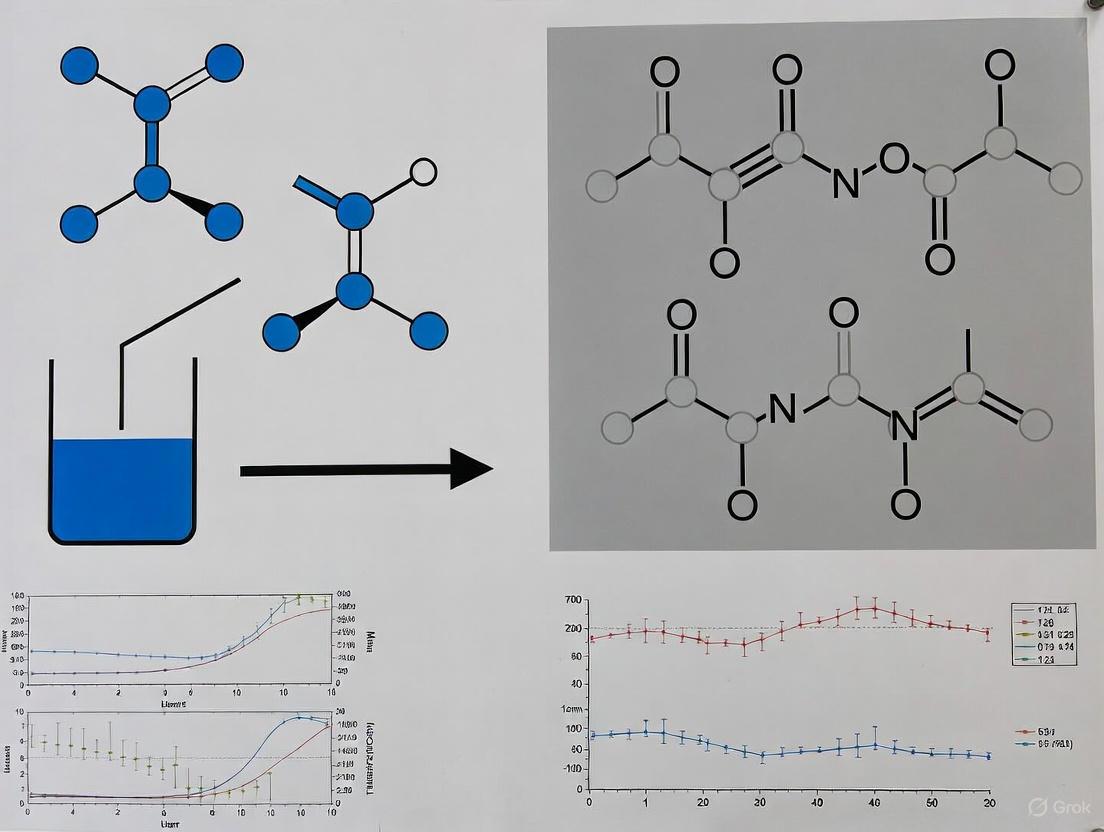

The following diagram illustrates the complete ESI process from sample introduction to gas-phase ion formation:

Diagram: ESI Process from Sample Introduction to Gas-Phase Ion Formation

Experimental Methodology and Protocols

Standard ESI-MS Protocol for Protein Analysis

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein solution in volatile solvent (typically water mixed with methanol or acetonitrile) [1]

- Add volatile additives such as 0.1% formic acid or acetic acid to enhance conductivity and proton availability [1]

- Optimal concentration range: 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁴ M (1-100 pmol/μL) [1] [2]

- Purify samples when necessary using HPLC, capillary electrophoresis, or liquid-solid column chromatography [7]

Instrumental Parameters:

- Flow rate: 1-20 μL/min (conventional ESI); 25-800 nL/min (nano-ESI) [3] [1]

- Capillary voltage: 2-6 kV applied to metal needle relative to counter electrode [3]

- Nebulizing gas: Nitrogen sheath gas flow around capillary for improved aerosolization [3]

- Desolvation temperature: Heating capillary maintained at 100-300°C [8]

- Source-sampling cone distance: 1-3 cm from spray needle tip [3]

Critical Considerations:

- ESI efficiency varies significantly (>10⁶-fold) based on compound structure and solvent composition [1]

- Multiple charging reduces m/z values, bringing large proteins within range of common mass analyzers [3]

- Nano-ESI provides enhanced sensitivity due to smaller initial droplet size [1]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful ESI-MS analysis requires specific reagents and materials optimized for the electrospray process:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ESI-MS

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Volatile Solvents | Sample dissolution and transport | Water-methanol or water-acetonitrile mixtures [1] |

| Acidic Additives | Enhance conductivity and protonation | 0.1-1% Formic or acetic acid [1] |

| Metal ESI Capillary | Sample introduction and charge application | Stainless steel, ~0.1 mm i.d., ~0.2 mm o.d. [3] |

| Syringe Pump | Controlled sample delivery | Flow rate: 1-20 μL/min (conventional ESI) [3] |

| Nebulizing Gas | Aerosol stabilization and direction | Dry nitrogen (N₂) sheath gas [3] |

| Heated Capillary | Solvent evaporation | Temperature: 100-300°C [8] |

Technical Advancements and Variants

The fundamental ESI technique has spawned several specialized variants designed to address specific analytical challenges:

Nano-Electrospray Ionization (Nano-ESI): Developed by Wilm and Mann in 1994, nano-ESI operates at very low flow rates (25-800 nL/min) using emitters with openings of a few micrometers [1]. This approach generates smaller initial droplets, resulting in improved ionization efficiency, reduced sample consumption, and enhanced sensitivity [1].

Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI): Introduced in 2004, DESI is an ambient ionization technique where an electrospray is directed at a sample surface, desorbing and ionizing analytes for direct analysis without sample preparation [6].

Cold Spray Ionization: This variant forces samples through a cold capillary (10-80°C) into an electric field, preserving non-covalent interactions and molecular complexes that might be disrupted by standard ESI conditions [1].

Extractive Electrospray Ionization: An ambient ionization method that merges two sprays, one generated by electrospray, to extract and ionize analytes from surfaces or matrices [1].

Impact on Biological Sciences and Drug Development

ESI-MS has fundamentally transformed biological research and pharmaceutical development through several critical applications:

Proteomics and Protein Characterization: ESI-MS enables precise molecular weight determination of intact proteins, identification of post-translational modifications, and sequencing of peptides through tandem MS [3]. The multiple charging phenomenon allows measurement of proteins with molecular weights exceeding 100 kDa using conventional mass analyzers [3].

Non-Covalent Interactions: As a soft ionization technique, ESI can preserve weak non-covalent interactions in the gas phase, allowing study of protein-ligand complexes, protein-DNA interactions, and other macromolecular assemblies [3].

Quantitative Analysis: When coupled with liquid chromatography (LC-ESI-MS), the technique provides robust quantitative capabilities for drug metabolism studies, pharmacokinetic analyses, and biomarker validation [9].

High-Throughput Screening: ESI-MS compatibility with liquid-based separation techniques and automation has made it indispensable in modern drug discovery pipelines for compound screening and validation [8].

The invention of ESI-MS represents a paradigm shift in analytical chemistry, successfully bridging the gap between condensed-phase biological samples and gas-phase mass analysis. From its theoretical origins in Rayleigh's electrostatic calculations to Fenn's practical implementation and Nobel Prize-winning application to biomolecules, the development of electrospray ionization demonstrates how fundamental scientific principles can be translated into transformative analytical technologies. Today, ESI-MS continues to evolve, enabling increasingly sophisticated analyses of biological systems and maintaining its position as an indispensable tool in scientific research and drug development.

The invention of electrospray ionization (ESI) profoundly transformed mass spectrometry by removing the long-standing limitation on the molecular weight of analyzable substances. Prior to the late 1980s, mass spectrometers were restricted in the molecular weight of analytes they could process. With the discovery of ESI and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), molecules with masses beyond 1000 Da could be efficiently transferred into the gas phase without fragmentation, opening new research areas in chemistry, biochemistry, and biology [2]. Unlike earlier ionization techniques, ESI generates ions directly from liquid solutions at atmospheric pressure, making it uniquely compatible with liquid-phase separation techniques like liquid chromatography. This compatibility, combined with its ability to ionize an extraordinarily wide range of chemical substances—from small metabolites to large noncovalent protein complexes exceeding 100 MDa—has established ESI as the most widely used ionization technique in chemical and biochemical analysis today [2] [10]. This technical guide deconstructs the fundamental physical mechanisms underlying ESI, focusing on the formation of Taylor cones, the evolution of charged droplets, and the contested mechanisms of final ion emission.

The Taylor Cone: Foundation of Electrospray

The electrospray process begins with the formation of the Taylor cone, a phenomenon first described by Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor in 1964 through his theoretical work on water droplets in strong electric fields, similar to those found in thunderstorms [11]. When an electrical potential is applied to a liquid emerging from a nozzle, the liquid meniscus deforms into a conical shape due to the equilibrium between two opposing forces: surface tension, which strives to minimize the liquid surface area, and electrostatic Coulomb forces, which pull the liquid toward a counter electrode [2] [12].

Taylor theoretically demonstrated that a perfect cone under these conditions must have a specific semi-vertical angle of 49.3°, resulting in a total cone angle of 98.6° [11]. This specific angle, known as the Taylor angle, arises from the requirement that the cone's surface must be an equipotential surface in a steady-state equilibrium [11]. The electric field must have azimuthal symmetry and scale with R^(1/2), leading to a voltage distribution described by V = V₀ + AR^(1/2)P₁/₂(cosθ₀), where P₁/₂ is a Legendre polynomial of order 1/2, and the solution requires P₁/₂(cosθ₀) = 0, yielding θ₀ = 130.7° for the complementary angle [11].

When the applied voltage reaches a critical threshold (the Taylor cone voltage), the force balance becomes independent of the curvature radius at the apex. The liquid surface suddenly transforms from an elliptical shape to a sharply pointed cone, and a fine spray of charged droplets is emitted from the tip [2]. This transition marks the beginning of the electrospray process. The droplets generated are charged close to their theoretical maximum, known as the Rayleigh limit [2]. Recent numerical simulations have revealed complex electrohydrodynamic behaviors within the Taylor cone, including the formation of toroidal recirculation cells (RCs) driven by surface charge convection [12]. These recirculation patterns, which develop within 1 millisecond of voltage application, significantly influence electrospray quality and efficiency by affecting the transport of charge and liquid to the cone tip [12].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Taylor Cone Formation and Stability

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Electrospray |

|---|---|---|

| Applied Voltage | Electric potential between nozzle and electrode | Must exceed threshold for cone-jet formation; affects droplet size and charge |

| Surface Tension | Liquid property resisting surface area increase | Higher values require higher voltages; affects cone stability |

| Liquid Conductivity | Ability of liquid to conduct electrical current | Influences charge transport to cone surface and jet stability |

| Flow Rate | Volumetric rate of liquid supply | Affects cone stability and transition between spraying modes |

| Viscosity | Liquid resistance to flow | Higher values dampen instabilities but may inhibit jet formation |

Charged Droplet Evolution and Coulomb Fission

Once the Taylor cone is established and primary droplets are emitted, these droplets undergo a predictable evolution driven by solvent evaporation and Coulombic forces. The initial droplets produced at the tip of the Taylor cone are highly charged, near the Rayleigh stability limit—the maximum charge a droplet can carry before electrostatic repulsion overcomes surface tension [2]. As these droplets travel toward the mass spectrometer inlet, they lose solvent molecules to evaporation. This process reduces the droplet size while maintaining its initial charge, leading to a continuous increase in surface charge density [13].

When the charge density reaches a critical threshold, the droplet becomes unstable and undergoes a process known as Coulomb fission or disintegration by Coulombic explosion [11]. In this process, the electrostatic repulsion between like charges surpasses the cohesive force of surface tension, causing the droplet to eject smaller, highly charged offspring droplets. This fission process does not necessarily occur when the entire droplet reaches the Rayleigh limit; rather, it can be triggered locally at points on the droplet surface with the smallest curvature radius, where the electric field density is highest [2]. The process repeats iteratively, with each generation of droplets undergoing further evaporation and fission events, progressively producing smaller and smaller droplets until they reach diameters on the order of 10-20 nanometers [2].

Table 2: Stages of Charged Droplet Evolution in Electrospray Ionization

| Stage | Droplet Diameter | Key Processes | Timescale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Droplet Formation | ~200 nm - several μm | Taylor cone formation, jet breakup | Microseconds |

| Solvent Evaporation | Decreasing size | Neutral solvent molecule loss, charge concentration | Microseconds |

| Coulomb Fission | Variable | Droplet disintegration, offspring droplet emission | <1 microsecond |

| Secondary Droplet Evolution | <100 nm | Repeated evaporation/fission cycles | Microseconds |

| Final Ion Formation | Molecular scale | Ion evaporation or charge residue desolvation | Final stage |

The following diagram illustrates the complete electrospray process from Taylor cone formation to final ion generation:

Ion Emission Mechanisms: Competing Theories

The final step in electrospray ionization—the transition of analyte ions from the condensed phase (within charged droplets) to the gas phase—remains an area of active research and debate. Two primary models have been proposed to explain this critical process: the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM) and the Charge Residue Model (CRM). Both models seek to explain how ions ultimately detected by the mass spectrometer are liberated from the highly charged nanodroplets.

Ion Evaporation Model (IEM)

The Ion Evaporation Model, originally developed by Iribarne and Thomson to explain the generation of atomic ions, proposes that as droplets shrink to very small sizes (approximately 20 nm in diameter), the electric field strength at their surface becomes sufficiently intense to directly desolvate and eject solvated ions into the gas phase [2]. In this mechanism, the energy gain from the strong electric field at the droplet surface compensates for the energy required to rapidly enlarge the surface as the solvated ion is expelled [2]. The IEM is characterized by several key features: First, it becomes significant only when droplets reach nanoscale dimensions. Second, the kinetics of ion evaporation depend exponentially on the activation free enthalpy (ΔG) required for ion expulsion, making the process highly sensitive to the physicochemical properties of the ion itself [2]. Finally, ion evaporation begins when the surface charge density is below the maximum possible density at the Rayleigh limit [2]. Early work by Fenn and colleagues favored this model to explain the generation of large molecular ions [2].

Charge Residue Model (CRM)

The Charge Residue Model, initially proposed by Malcolm Dole, offers an alternative explanation. It posits that the electrospray process generates droplets so small that they contain only one analyte molecule or ion [2]. As the solvent completely evaporates from these nanodroplets, the charge originally distributed across the droplet surface remains on the analyte, which is subsequently released as a gas-phase ion [2]. This model implies that the ionization rate is largely independent of the specific ion's properties; instead, it is governed by the efficiency of droplet formation and solvent evaporation [2]. The CRM naturally explains the ability of ESI to generate ions from very large molecules and noncovalent complexes, as the process does not require the analyte to overcome a significant energy barrier or undergo acceleration in a strong electric field that could disrupt weak molecular interactions [2]. The available charge on the final ion is determined by the Rayleigh stability limit of the ultimate droplet from which it originated [2].

Current Understanding and Reconciliation

Modern research suggests that both mechanisms likely operate simultaneously or competitively, depending on the experimental conditions and the nature of the analyte. Small ions may favor the IEM, while very large biomolecules and complexes may follow the CRM pathway. The extremely high ionization efficiency of nano-electrospray sources (approaching 100%), which generate primary droplets as small as 200 nm in diameter, supports the notion that small droplets are the primary source of ions detected by mass spectrometers [2].

Table 3: Comparison of Ion Emission Mechanisms in Electrospray Ionization

| Characteristic | Ion Evaporation Model (IEM) | Charge Residue Model (CRM) |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet Size at Ion Emission | ~20 nm diameter | Ultimately single molecule-containing droplet |

| Key Driving Force | High surface field strength | Complete solvent evaporation |

| Dependence on Ion Properties | Strong exponential dependence | Weak dependence |

| Mass Limitations | Potentially limited for very large masses | No practical mass limitation |

| Suitability for Noncovalent Complexes | May disrupt weak interactions | Preserves noncovalent complexes |

| Historical Proponents | Iribarne & Thomson; Fenn et al. | Dole et al. |

Experimental Methodologies for Mechanism Study

Numerical Simulation of Taylor Cone Dynamics

Advanced computational models provide insights into the electrohydrodynamic (EHD) behaviors within the Taylor cone that are challenging to observe experimentally.

Protocol:

- Model Setup: Implement a 2D axisymmetric computational domain using Finite-Element Method (FEM) based EHD solver [12].

- Governing Equations: Solve Navier-Stokes equations for fluid flow, Gauss's law for electric field, and charge conservation equation for surface charge distribution [12].

- Interface Tracking: Employ Volume of Fluid (VOF) method to track liquid-air interface dynamics [12].

- Boundary Conditions: Apply high voltage at the emitter (e.g., 4 kV) and ground at the extraction electrode [12].

- Parameter Variation: Systematically study effects of liquid properties (viscosity, surface tension, conductivity) and operating parameters (flow rate, voltage) [12].

- Validation: Compare simulation results with experimental data on cone-jet morphology and spraying current [12].

Key Findings:

- Surface Charge Convection (SCC) introduces a high-pressure region at the cone tip, driving liquid recirculation within 1 ms of voltage application [12].

- Recirculation cells (RCs) enhance mixing and charge transport, significantly impacting electrospray quality and efficiency [12].

- The position and stability of RCs are strongly influenced by liquid viscosity and electrical conductivity [12].

High-Throughput DESI-MS for Reaction Monitoring

Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) integrates desorption and ionization, using charged electrospray droplets to both desorb and ionize analytes from surfaces [10].

Protocol:

- Spray Source Setup: Generate primary electrospray droplets using typical ESI conditions (capillary voltage: 2.5-6.0 kV, nebulizing gas flow) [13].

- Surface Impact: Direct charged droplets onto sample surface at optimal incident angle (typically 50-70 degrees) [10].

- Desorption/Ionization: Allow impacting droplets to dissolve and ionize analytes from the surface, forming secondary droplets [10].

- Sample Transfer: Transport secondary droplets containing dissolved analytes into the mass spectrometer inlet [10].

- High-Throughput Screening: Implement automated sampling platform for rapid analysis (>1 reaction per second) [14].

- Data Acquisition: Utilize tandem MS (MS/MS) for structural elucidation or Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for quantification [13].

Key Findings:

- DESI enables label-free bioassays and reaction monitoring of functionalized drugs directly from crude reaction mixtures [14].

- Minimal sample preparation is required, and analysis can be performed under ambient conditions [10].

- DESI is particularly effective for metabolites and lipids, achieving high sensitivity imaging of biological tissue sections [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrospray Ionization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in ESI Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Model electrolytes for studying cone-jet dynamics | Investigating meniscus formation and charge transport [12] |

| Sheath Flow Solutions | Interface for analyzing difficult-to-ionize samples | Coupling separation techniques with ESI-MS [13] |

| Volatile Buffers (Ammonium Acetate/Formate) | Provide conductivity while enabling evaporation | Maintaining noncovalent complexes in native MS [2] |

| Nebulizing Gas (Nitrogen) | Shears eluted solution to enhance droplet formation | Enabling higher sample flow rates in ESI [13] |

| Collision Gas (Argon) | Fragments precursor ions in tandem MS | Structural elucidation via collision-induced dissociation [13] |

| DESI Spray Solvents | Desorption and ionization of surface analytes | Tissue imaging, reaction monitoring [10] [14] |

The electrospray ionization mechanism represents a sophisticated interplay between electrohydrodynamics, surface science, and ion chemistry. From the precisely defined geometry of the Taylor cone to the iterative Coulomb fission of charged droplets and the contested pathways of final ion emission, each stage of the process contributes to ESI's remarkable capability to transfer diverse molecules from solution to the gas phase for mass spectrometric analysis. While significant progress has been made in understanding these mechanisms through numerical simulations, experimental investigations, and practical applications, the continued refinement of these models promises to further enhance the sensitivity, selectivity, and applications of this transformative ionization technique in chemical and biological research.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) represents a pivotal advancement in mass spectrometry, enabling the analysis of large, non-volatile, and thermally labile biomolecules without inducing significant fragmentation. This "soft" ionization technique achieves this by transferring pre-existing ions directly from solution into the gas phase, preserving the structural integrity of macromolecules. Its invention has fundamentally transformed fields such as proteomics, drug discovery, and metabolomics by allowing for the accurate mass measurement of proteins, the study of noncovalent complexes, and the high-throughput screening of metabolites. This technical guide delves into the core mechanisms of ESI, outlines detailed experimental protocols, and contextualizes its profound impact within modern scientific research.

The invention of electrospray ionization (ESI) for mass spectrometry by Masamichi Yamashita, John Fenn, and Lidia Gall (independently) in 1984 addressed a fundamental limitation in analytical chemistry: the inability to efficiently vaporize and ionize large, thermally unstable biomolecules [1]. Traditional "hard" ionization methods, like electron impact (EI), rely on bombarding gaseous sample molecules with high-energy electrons, which causes extensive fragmentation and makes it impossible to observe the intact molecular ion of a large protein [15].

ESI circumvented this problem entirely. As a soft ionization technique, it is characterized by minimal fragmentation, allowing the molecular ion to be observed [1]. Furthermore, ESI is unique in its ability to generate multiply charged ions [1]. For macromolecules like proteins, this means that a single molecule will acquire many protons, resulting in a series of ions with different mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios. This effectively extends the mass range of mass analyzers, making it possible to analyze species with molecular weights in the kDa to MDa range [1]. The capability to study noncovalent complexes in their native state has provided unprecedented insights into biomolecular interactions, driving innovation in drug discovery and structural biology [16]. The significance of this invention was recognized with the award of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry to John B. Fenn in 2002.

The Core Mechanism: How ESI Works

The ESI process transforms ions in solution into ions in the gas phase through a series of carefully controlled steps. The preservation of macromolecular structure is a direct consequence of this gentle process.

The Step-by-Step Process

The transfer of ionic species from solution into the gas phase by ESI involves three critical steps [13]:

Dispersal of a Fine Spray of Charged Droplets: A sample solution is pumped through a narrow capillary or emitter tip (e.g., a fused silica or metal needle) maintained at a high voltage (typically 2.5 – 6.0 kV) relative to a surrounding counter-electrode [13] [17]. This high voltage induces a high charge density on the liquid emerging from the tip. A nebulizing gas (e.g., nitrogen) is often used to shear the liquid stream, enhancing the formation of a fine mist or aerosol of highly charged droplets with the same polarity as the capillary voltage [13].

Solvent Evaporation and Droplet Shrinking: The charged droplets are directed towards the mass spectrometer's inlet. With the aid of a heated source temperature and a stream of dry nitrogen (drying gas), the solvent in the droplets begins to evaporate [13] [1]. As the droplet size decreases, its charge density increases significantly, but the total charge remains relatively constant.

Ion Ejection from Highly Charged Droplets: The continuous solvent evaporation increases the electrostatic repulsion between the like charges within the droplet. When the droplet reaches the Rayleigh limit, the point at which electrostatic repulsion overcomes surface tension, it becomes unstable and undergoes Coulombic fission, disintegrating into smaller, progeny droplets [1]. This process of evaporation and fission repeats until the electric field strength at the droplet's surface is high enough to energetically favor the direct emission of solvated ions into the gas phase, a process described by the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM) [1]. For larger molecules like folded proteins, it is believed that the final ion is formed after the last solvent molecule evaporates from a droplet containing a single analyte molecule, as described by the Charge Residue Model (CRM) [1].

Diagram illustrating the step-by-step ESI mechanism:

What Makes ESI "Soft"?

The "soft" nature of ESI is attributed to the minimal internal energy deposited into the analyte molecules during the ionization process. Unlike EI, which uses high-energy electrons that can break chemical bonds, ESI relies on field-assisted desorption at ambient temperatures and the gradual removal of solvent molecules. This process does not impart enough energy to cause significant fragmentation of the analyte's covalent backbone. The structural information of the macromolecule, including its primary sequence and, crucially, noncovalent interactions that maintain its tertiary and quaternary structure, is thereby preserved upon transfer into the gas phase [16] [15].

ESI in the Laboratory: Experimental Protocols and Setups

Successfully implementing ESI-MS requires careful attention to sample preparation, instrument configuration, and method selection.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for a typical ESI-MS experiment.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ESI-MS

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| ESI Solvent | A mixture of water and volatile organic solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile), often with modifiers (e.g., 0.1% formic acid). Facilitates droplet formation/evaporation and provides a proton source. [1] | Standard solvent for LC-ESI-MS of peptides and metabolites. |

| Volatile Buffers | Provides pH control to manipulate analyte charge (protonation/deprotonation) without leaving non-volatile residues that clog the instrument. (e.g., ammonium acetate, ammonium bicarbonate). | Studying noncovalent complexes at near-physiological pH. [16] |

| Calibration Solution | A solution of ions with known m/z ratios. Used to calibrate the mass scale of the instrument for accurate mass measurement. | Daily instrument calibration and performance verification. |

| Nebulizing Gas | An inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen) that shears the liquid eluent to enhance the formation of a fine aerosol at the ESI tip. [13] | Used in most flow-assisted ESI setups to stabilize the spray. |

| Drying Gas | A stream of heated, inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen) that accelerates the evaporation of solvent from the charged droplets. [13] [1] | Critical for desolvation in conventional ESI sources. |

| ESI Emitter Tip | The capillary through which the sample solution is introduced. Can be metallic or pulled fused silica coated with a conductor (e.g., gold). Tip geometry affects ionization efficiency. [17] | Nano-ESI tips for low flow rate applications (< 1 µL/min) for enhanced sensitivity. [1] |

Detailed Methodology: Interrogating a Noncovalent Protein-Ligand Complex

One of the most powerful applications of ESI-MS is the study of noncovalent complexes, such as a protein bound to a small-molecule drug candidate [16]. The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for such an analysis.

Objective: To confirm the formation of a noncovalent complex between a target protein and a ligand and to determine its binding stoichiometry.

Sample Preparation:

- Buffer Exchange: The protein and ligand must be in a volatile buffer compatible with ESI-MS, such as 10-100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8-7.5). This is typically achieved using size-exclusion chromatography or centrifugal filtration devices.

- Complex Formation: The protein and ligand are mixed at a concentration suitable for MS detection (typically 1-10 µM for the protein) in a molar ratio that promotes complex formation (e.g., 1:1, 1:2 protein:ligand). The mixture is incubated to reach binding equilibrium.

Instrumental Parameters (Q-TOF Mass Spectrometer):

- Ionization Mode: Nano-electrospray Ionization (nano-ESI) is often preferred for its high sensitivity and lower sample consumption [16] [1].

- Source Temperature: 20-50 °C. Lower temperatures help preserve noncovalent interactions.

- Capillary Voltage: 1.0-1.5 kV.

- Cone Voltage: 20-50 V. A low voltage is critical; a high voltage can induce collision-induced dissociation (CID) and disrupt the noncovalent complex.

- Mass Analyzer Mode: The instrument is operated in a sensitive, full-scan mode (e.g., m/z 500-4000) with adequate resolution to observe the charge state envelope of the protein and its complex.

Workflow Overview: Diagram of the experimental workflow for analyzing a noncovalent complex:

Data Analysis:

- The raw mass spectrum will show a series of peaks corresponding to different charge states of the free protein.

- Upon formation of the complex, a new series of peaks will appear at a higher m/z for each charge state, corresponding to the protein with the ligand bound.

- The mass difference between the free protein and the complex is used to calculate the mass of the bound ligand.

- The relative intensity of the peaks for the free protein versus the complex can provide information on binding affinity, and the number of ligand masses added reveals the binding stoichiometry (e.g., 1:1 or 2:1 ligand:protein) [16].

Comparative Analysis: ESI vs. Other Ionization Techniques

Understanding the position of ESI within the broader landscape of ionization methods highlights its unique advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Technique | Ionization Principle | "Softness" & Fragmentation | Typical Analytes | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Electrical energy to create charged droplets; ion evaporation or charge residue mechanism. [13] [1] | Very Soft; preserves noncovalent complexes; little fragmentation. [16] [1] | Proteins, peptides, oligonucleotides, natural products, drug metabolites. | Can analyze non-volatile and thermally labile molecules; produces multiply charged ions; compatible with liquid introduction (LC). [13] | Susceptible to ion suppression in mixtures; requires polar, soluble analytes. [15] |

| Electron Impact (EI) | Bombardment of gaseous molecules with high-energy (70 eV) electrons. [15] | Hard; extensive fragmentation; molecular ion may be absent. [15] | Small, volatile, and thermally stable molecules (e.g., environmental contaminants, drugs). | Reproducible, library-searchable spectra; provides structural information via fragments. | Not suitable for large or thermally labile molecules; sample must be volatile. |

| Chemical Ionization (CI) | Ion-molecule reactions between analyte and reagent gas ions (e.g., CH₅⁺). [15] | Softer than EI; less fragmentation; pseudomolecular ion [M+H]⁺ is common. [15] | Similar to EI, but for less stable molecules. | Softer than EI, providing molecular weight information. | Sample must still be volatile; less fragmentation means less structural info than EI. |

| Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) | Laser desorption/ablation of a sample co-crystallized with a UV-absorbing matrix. [15] | Soft; primarily produces singly charged ions; little fragmentation. [15] | Proteins, peptides, polymers, carbohydrates. | High sensitivity for large MW molecules; robust and high-throughput. | Can be hampered by matrix interference peaks at low m/z; requires solid sample preparation. |

Advanced Applications and Current Frontiers

The invention of ESI has enabled sophisticated experimental paradigms across biomedical research.

- Drug Discovery: ESI-MS is used for Multitarget Affinity/Specificity Screening (MASS), where small-molecule libraries are screened against protein or RNA targets to identify binders, determine dissociation constants (KD), and define binding stoichiometry—all without labelling the ligand or target [16].

- Untargeted Metabolomics: To increase metabolite coverage, advanced workflows now involve running samples in both positive and negative ESI modes and using data-independent acquisition (DIA). Computational approaches like Regions of Interest Multivariate Curve Resolution (ROIMCR) are then used to link MS1 and MS2 signals from both modes, providing a more comprehensive view of the metabolome [18].

- Structural Biology and Native MS: By using volatile buffers that maintain near-native conditions, ESI-MS can be used to measure the intact mass of protein complexes, study protein-ligand interactions, and even determine the stoichiometry of subunits within large macromolecular assemblies [16].

- Natural Organic Matter (NOM) Characterization: Coupling ESI with ultra-high resolution mass spectrometers like Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) MS allows for the detailed structural characterization of incredibly complex mixtures, such as humic and fulvic acids from soil and water, by assigning exact molecular formulas to thousands of components simultaneously [19].

Electrospray Ionization stands as a cornerstone technology of modern analytical science. Its ingenious mechanism of using electrical energy to gently transfer ions from solution to the gas phase has overcome the fundamental barriers that once made mass spectrometry of macromolecules impossible. By preserving the intrinsic structure of biomolecules, ESI provides a unique window into the world of proteins, their complexes, and their interactions. As the technique continues to be refined and integrated with novel separation strategies and advanced mass analyzers, its role in driving discovery in proteomics, drug development, and beyond remains not only secure but also poised for future growth. The invention of ESI truly unlocked a new dimension for mass spectrometry, transforming it from a tool for small molecules into an indispensable technology for the life sciences.

The evolution of electrospray ionization (ESI) from macro- to nano-flow regimes represents a pivotal technological advancement in mass spectrometry. This transition has fundamentally enhanced analytical sensitivity, reduced sample consumption, and expanded applications across biological research and drug development. By tracing key historical milestones and technical innovations, this review examines how flow rate reduction has enabled the precise analysis of minute sample volumes, from traditional protein characterization to cutting-edge single-cell proteomics. The methodological principles and experimental parameters that underpin successful nano-ESI implementation are detailed herein, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical framework for leveraging this transformative technology in biomedical research.

Electrospray ionization (ESI) has revolutionized mass spectrometry by enabling the analysis of large, non-volatile biomolecules. The fundamental principles of electrospray were first investigated by John Zeleny in 1914, followed by Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor's characterization of the "Taylor cone" in 1964 [1]. However, the pivotal development occurred in 1968 when Malcolm Dole first demonstrated the application of electrospray for producing gas-phase molecular ions from synthetic polymers [1] [3]. Despite this breakthrough, the technique remained largely undeveloped for biological applications until the late 1980s.

The pioneering work of John B. Fenn and colleagues in 1988 ultimately established ESI as a cornerstone of modern mass spectrometry, earning Fenn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002 [1] [20] [3]. Early ESI systems operated at conventional flow rates (typically 1-20 μL/min) and employed metal capillaries with internal diameters of approximately 0.1 mm [3]. These macro-ESI systems applied high voltages (2-6 kV) to disperse analyte solutions into charged droplets at atmospheric pressure. Through solvent evaporation and Coulomb fission processes, these droplets eventually yielded gas-phase ions suitable for mass analysis [1] [3].

A critical insight from Fenn's research was the phenomenon of multiple charging, wherein large biomolecules acquire numerous charges during ionization. This produces ions with lower mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios, effectively extending the mass range of conventional mass analyzers and enabling the study of high molecular weight proteins [3]. Despite this breakthrough, conventional ESI faced limitations in sensitivity and efficiency, particularly with scarce biological samples, prompting investigations into reduced flow rate operation.

Technical Evolution: Key Milestones in Flow Rate Reduction

Historical Progression and Theoretical Foundations

The systematic reduction of ESI flow rates represents a cornerstone achievement in analytical methodology. This evolution was driven by the recognition that smaller initial droplets improve ionization efficiency and enhance analytical sensitivity.

Table 1: Key Milestones in ESI Flow Rate Evolution

| Year | Development | Flow Rate Range | Key Innovators/Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | First ESI for mass spectrometry | Not optimized | Malcolm Dole [1] | Demonstrated principle of electrospray for polymer analysis |

| 1988 | Conventional ESI for biomolecules | 1-20 μL/min | John B. Fenn [20] [3] | Enabled ionization of intact proteins; multiple charging |

| 1993 | Micro-ESI | 200-800 nL/min | Gale and Smith [1] | Reported significant sensitivity increases at lower flow rates |

| 1994 | Nano-ESI introduced | ~25 nL/min | Wilm and Mann [1] | Used pulled glass capillaries (1-4 μm) for self-fed electrospray |

| 2000s | Advanced nano-ESI applications | < 100 nL/min | Various groups [21] [22] | Extended to single-cell analysis and cryo-EM sample preparation |

The theoretical foundation for flow rate reduction centers on droplet physics. As flow rates decrease, the initial droplet size diminishes according to the relationship: [ d \propto Q^{1/3} ] where (d) represents droplet diameter and (Q) represents flow rate. Smaller initial droplets require less solvent evaporation and undergo fewer fission cycles to yield gas-phase ions, thereby improving ion production efficiency [1]. The Rayleigh limit defines the maximum charge a droplet can carry before fission occurs, a fundamental principle governing the electrospray process [1].

The transition from stainless steel capillaries to pulled glass emitters with tip diameters of 1-4 μm was a crucial innovation enabling stable operation at nano-flow rates [1]. These nano-ESI sources produce initial droplets less than 100 nm in diameter—100–1,000 times smaller than conventional ESI—significantly enhancing ionization efficiency and reducing sample requirements [21].

Comparative Analysis of ESI Flow Rate Regimes

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Across ESI Flow Rate Regimes

| Parameter | Conventional ESI | Micro-ESI | Nano-ESI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | 1-20 μL/min [3] | 200-800 nL/min [1] | 25-100 nL/min [21] [1] |

| Initial Droplet Size | ~200 μm [21] | Reduced size | <100 nm [21] |

| Sample Consumption | High (microliters) | Moderate | Minimal (nanoliters) [22] |

| Ionization Efficiency | Lower | Improved | Highest [23] |

| Typical Emitter | Metal capillary (~0.1-0.2 mm i.d.) [3] | Fused silica capillary | Pulled glass capillary (1-5 μm i.d.) [22] |

| Application Scope | Standard protein analysis | LC-MS coupling | Single-cell analysis, complex mixtures [22] [23] |

The sensitivity enhancement in nano-ESI stems from improved ionization efficiency and more efficient sample utilization. At flow rates of ~25 nL/min, ionization efficiencies can exceed 50% for transfer of ions from liquid to gas phase, compared to typically <1% in conventional ESI [1]. This dramatic improvement enables analysis of limited samples, such as single cells or biopsy material, where sample amounts are severely constrained.

Experimental Methodologies: Protocols for Nano-ESI Implementation

Critical Parameters for Nano-ESI Operation

Successful implementation of nano-ESI requires careful optimization of multiple parameters to maintain stability while preserving biomolecular integrity. Based on cryo-EM and single-cell MS studies, the following protocols provide guidance for method development:

Emitter Preparation and Positioning: Nano-ESI emitters are typically fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries pulled to tip inner diameters of 1-5 μm [22]. For enhanced stability and electrochemical compatibility, tips may be sputter-coated with conductive materials such as gold or employ inserted platinum electrodes [21]. The optimal emitter-to-inlet distance ranges from 1-1.5 cm, balancing ionization progression with minimal sample loss [21].

Flow Rate Optimization: While nano-ESI can operate with self-fed capillaries through capillary action, precise flow control via syringe pumps or pressure-assisted systems is often employed. The optimal flow rate range is 100-300 nL/min for preserving protein integrity while maintaining appropriate ice thickness in cryo-EM applications [21]. Flow rates below 100 nL/min may induce protein denaturation as evidenced by charge state shifts in mass spectra [21].

Voltage and Gas Configuration: Spray voltage should be optimized to maintain a stable Taylor cone while minimizing the risk of electrical discharge and protein damage. A voltage of 3 kV has been demonstrated as optimal for preserving intact proteins while maintaining steady spray conditions [21]. Nebulizing gas should be used cautiously, as increased gas flow rates correlate with protein damage, indicated by collapsed structures in micrographs and broader charge state distributions [21].

Solution Conditions: Sample solutions should utilize volatile buffers such as ammonium acetate to replace non-volatile salts like NaCl, preventing crystallization during desolvation [21]. Sample concentration significantly impacts results, with lower concentrations increasing denaturation risk at higher spray voltages [21].

Analytical Verification Techniques

Native MS Analysis: Native mass spectrometry provides critical verification of biomolecular integrity following nano-ESI. Charge state distribution serves as a key indicator—compact, folded states exhibit lower charge states, while unfolded proteins display higher charge states [21] [3]. Shift to higher charge states indicates unfolding and potential disruption of native structure.

Negative Staining EM: For cryo-EM applications, negative staining electron microscopy offers rapid assessment of particle integrity and distribution. Well-preserved proteins appear as distinct particles with characteristic morphology, while damaged proteins exhibit collapsed or irregular structures [21].

Single-Cell MS Sampling: Advanced nano-ESI methodologies for single-cell analysis include:

- Droplet Microextraction: A nano-tip dispenses extraction solvent onto cell surfaces, extracting metabolites into droplets which are then aspirated back for analysis [22].

- Localized Electroosmotic Extraction: Uses nanopipettes (<1 μm diameter) with hydrophobic electrolytes for controlled extraction of sub-picoliter volumes (2-5 pL) from individual cells [22].

- T-Probe Sampling: A miniaturized device integrating sampling and ionization capillaries in a "T" configuration enables online, in situ single-cell MS analysis under environmental conditions [22].

Figure 1: Nano-ESI Experimental Workflow from Sample Preparation to Data Interpretation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nano-ESI

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Emitter Capillaries | Borosilicate glass, 1-5 μm tip diameter [22] | Ion source for nano-ESI |

| Conductive Coatings | Gold or platinum sputtering [21] [1] | Enhanced conductivity and electrochemical stability |

| Volatile Buffers | Ammonium acetate replacement for NaCl [21] | Prevents crystallization during desolvation |

| Syringe Pumps | Precise flow control (25-300 nL/min) [21] | Delivery of sample solutions |

| Nebulizing Gas | Nitrogen or carbon dioxide [1] | Assisted droplet formation (use cautiously) |

| Mass Analyzers | Quadrupole-Orbitrap, TOF, FT-ICR [23] | High-resolution mass analysis |

| Separation Systems | Nano-LC, Capillary Electrophoresis [22] | Pre-separation of complex mixtures |

Advanced Applications: From Single-Cell Analysis to Integrated Structural Biology

The implementation of nano-flow ESI has enabled groundbreaking applications across multiple biomedical research domains:

Single-Cell Omics: Nano-ESI has become foundational for single-cell proteomics and metabolomics, enabling characterization of cellular heterogeneity previously obscured by bulk measurements. The extremely low flow rates (as low as 25 nL/min) provide longer analysis times, facilitating multistage MS for structural elucidation of unknown compounds [22]. When coupled with separation techniques like capillary electrophoresis or nano-liquid chromatography, nano-ESI enables comprehensive profiling of hundreds of metabolites from individual cells [22].

Structural Biology Integration: Recent innovations demonstrate the application of ESI-cryoPrep for cryo-electron microscopy sample preparation. This method uses electrospray to deposit charged macromolecule-containing droplets on EM grids, effectively confining molecules within amorphous ice and preventing adsorption at air-water interfaces that causes denaturation or preferred orientation [21]. The technique eliminates blotting requirements and enhances controllability and reproducibility in cryo-specimen preparation.

High-Throughput Drug Discovery: Desorption electrospray ionization (DESI), an ambient ionization technique derived from ESI principles, enables high-throughput reaction screening and synthesis. This approach leverages reaction acceleration in microdroplets, achieving throughput of one reaction per second for rapid chemical space exploration, particularly in late-stage diversification of drug molecules [24].

Native Mass Spectrometry: Nano-ESI preserves weak noncovalent interactions in the gas phase, facilitating the study of protein complexes, protein-ligand interactions, and higher-order structures [3]. This "soft" ionization characteristic allows researchers to investigate stoichiometry, dynamics, and interactions of macromolecular assemblies under near-physiological conditions.

The evolution from macro- to nano-flow ESI represents a paradigm shift in mass spectrometry, transforming capabilities for biological analysis. This transition has enabled unprecedented sensitivity, minimized sample requirements, and opened new frontiers in single-cell analysis and structural biology. The continued refinement of nano-ESI methodologies promises to further advance biomedical research, particularly in mapping cellular heterogeneity, elucidating molecular structures, and accelerating therapeutic development. As instrumentation and methodologies evolve, nano-ESI will undoubtedly maintain its pivotal role at the forefront of analytical science, enabling researchers to address increasingly complex biological questions with enhanced precision and depth.

ESI-MS in Action: Pioneering Applications from Clinical Labs to Drug Discovery

The invention of electrospray ionization (ESI) for mass spectrometry fundamentally reshaped the landscape of biological research by enabling the analysis of large, noncovalent biomolecular complexes directly from solution. This technical guide explores how this foundational technology, particularly in its native mass spectrometry (nMS) mode, has become an indispensable tool for fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD). nMS provides a powerful platform for interrogating the weak, noncovalent interactions between low-molecular-weight fragments and therapeutic targets, guiding the efficient development of novel therapeutics. We detail the experimental protocols, data interpretation, and practical integration of nMS within the FBDD workflow, framing its impact within the broader context of the ESI-MS revolution.

The development of electrospray ionization (ESI) marked a pivotal invention in analytical science, as it allowed for the gentle transfer of large, intact biomolecules and their noncovalent complexes from solution into the gas phase of a mass spectrometer [25]. This breakthrough opened a new frontier in structural biology, often termed "gas-phase structural biology," by providing a means to study proteins, nucleic acids, and their assemblies in their near-native states [26].

Within drug discovery, this capability is critically leveraged in fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD), a strategy that addresses the challenges of traditional high-throughput screening. FBDD utilizes small, low-molecular-weight chemical fragments (typically <300 Da) that bind weakly to a target protein [27] [28]. While these fragments exhibit lower affinity, they possess high ligand efficiency, meaning each atom contributes significantly to binding, making them ideal starting points for developing potent and selective drug candidates [29]. The primary challenge in FBDD is reliably detecting these weak, noncovalent interactions, a task for which native MS is exquisitely suited [29].

Core Principles of Native Mass Spectrometry in FBDD

Interrogating Noncovalent Interactions

The foundation of nMS in FBDD is its ability to preserve and detect noncovalent interactions during the ionization and mass analysis process. These interactions—which include conventional hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, as well as more unconventional ones like halogen and chalcogen bonds—are essential for biomolecular structure, stability, and function [30] [31]. nMS directly detects the intact protein-ligand complex, providing unambiguous evidence of binding.

The Native MS Experiment Workflow

A typical nMS experiment for fragment screening involves several key stages, designed to maintain the native state of the biomolecule:

- Sample Preparation: The target protein or nucleic acid is buffer-exchanged into a volatile ammonium acetate solution (typically 100–200 mM, neutral pH) to ensure compatibility with the ESI process. This step removes nonvolatile salts that could interfere with ionization [26].

- Gentle Ionization: The sample is introduced into the mass spectrometer using nanoelectrospray ionization (nanoESI). This technique uses smaller-diameter emitters, resulting in lower flow rates, gentler desolvation, and reduced experimental charge states, which collectively improve the preservation of weak noncovalent interactions [26] [16].

- Mass Analysis and Detection: The ions are analyzed by the mass spectrometer, producing a spectrum where the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of the intact protein and any bound complexes is measured. The process of deconvolution is then used to convert the m/z data into molecular weight, confirming the identity and stoichiometry of the complexes present [26].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and the key information obtained at each stage.

The FBDD Workflow: Integration of Native MS

Fragment-based drug discovery follows a structured, iterative workflow where nMS can be integrated at multiple points to guide decision-making. The table below outlines the key stages and the role of nMS in each.

Table 1: Stages of the FBDD Workflow and the Role of Native MS

| Stage | Primary Objective | Role of Native MS |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Library Design | Curate a diverse library of small fragments (<300 Da). | Not directly involved, but the library is designed for noncovalent interactions. |

| 2. Fragment Screening | Identify initial "hit" fragments that bind to the target. | Primary Screening: Detect fragment binding directly from the mixture. Hit Validation: Orthogonally validate hits from other techniques [29]. |

| 3. Structural Elucidation | Determine the atomic-level binding mode of the fragment. | Provides complementary data on stoichiometry and can be coupled with other structural techniques [28]. |

| 4. Fragment-to-Lead Optimisation | Grow, link, or merge hits into higher-affinity lead compounds. | Affinity Measurement: Quantify dissociation constants (Kd) during optimisation [32]. Specificity Screening: Check for off-target binding [16]. |

The following diagram provides a visual overview of this integrated workflow.

Experimental Protocols for Native MS in FBDD

Direct Screening for Hit Identification

Objective: To rapidly identify fragments that bind to a target protein from a library screen. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate the target protein (typically at ~5 µM concentration) with individual fragments or a mixture of fragments (at high micromolar to low millimolar concentration) in volatile ammonium acetate buffer [29].

- nMS Analysis: Infuse the sample using nanoESI into a mass spectrometer tuned to preserve noncovalent interactions (e.g., reduced source voltages and pressures).

- Data Interpretation: The mass spectrum is inspected for the appearance of new ion signals corresponding to the mass of the protein-fragment complex. A successful binding event is confirmed by an observed mass increase equal to the mass of the bound fragment and a shift in the charge state distribution to lower charges [26] [16].

Determining Dissociation Constants (Kd)

Objective: To quantify the binding affinity between a confirmed hit fragment and the target protein. Protocol:

- Titration Experiment: Prepare a series of samples with a constant concentration of protein and varying concentrations of the fragment ligand [26] [32].

- nMS Analysis: Acquire native mass spectra for each sample in the titration series.

- Quantification: For each spectrum, measure the relative intensity (or peak area) of the signal for the unbound protein ([P]) and the protein-ligand complex ([PL]).

- Kd Calculation: The fraction bound (θ) is calculated as [PL]/([P] + [PL]). This data is then fit to a binding model (e.g., a 1:1 binding isotherm) using non-linear regression to determine the Kd* value [32]. A more rapid single-concentration approach can be used for initial triaging, provided the concentrations are carefully chosen relative to the expected Kd* and validated with controls [26].

Advantages of Native MS in the Biophysical Toolkit

Native MS offers a unique combination of advantages that make it a powerful complement to other biophysical techniques in FBDD. The following table provides a comparative overview.

Table 2: Comparison of Biophysical Techniques Used in Fragment Screening

| Technique | Throughput | Affinity (Kd) Data | Stoichiometry | Target Consumption | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native MS | Medium-High [29] | Yes [29] [32] | Yes [26] | Low [29] | Direct observation of complex; label-free |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Medium [29] | Yes (with kinetics) [29] | Indirect | Low [29] | Provides real-time kinetics |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Medium [29] | Limited [29] | No [29] | High [29] | Provides structural and dynamic info |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Low [29] | Yes (with thermodynamics) [29] | Yes [29] | Very High [29] | Gold standard for thermodynamics |

| Thermal Shift Assay (TSA) | Medium-High [29] | Estimate only [29] | No [29] | Low [29] | Low cost, high throughput |

| X-ray Crystallography | Low-Medium [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | High [29] | Atomic-level structural detail |

The specific advantages of nMS include:

- Direct Observation: nMS provides direct evidence of binding by detecting the mass of the intact complex, eliminating ambiguity about the formation of the complex [16].

- Label-Free: Neither the target nor the fragment requires labeling, immobilization, or other modification that could perturb the native interaction [26] [16].

- Low Sample Consumption: The use of nanoESI allows for meaningful data to be obtained from picomoles of protein, a critical advantage for targets that are difficult to express or purify [26].

- Sensitivity to Heterogeneity: nMS can resolve and characterize multiple binding events or heterogeneous populations within a single sample, providing information on binding stoichiometry and specificity simultaneously [26] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of nMS for FBDD requires specific reagents and instrumentation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native MS in FBDD

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Volatile Buffer (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) | Maintains biomolecule in a native-like state while being compatible with the ESI process. Replaces nonvolatile biological buffers [26]. |

| NanoESI Capillaries / Emitters | Small-diameter tips for sample introduction that enable gentler ionization, reduced sample consumption, and better salt tolerance [26]. |

| Online Buffer Exchange (OBE) System | An automated, chromatographic system coupled directly to the mass spectrometer. Rapidly (<5 min) desalts samples, improving throughput and stability for low-stability targets [26]. |

| Quadrupole-Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) Mass Spectrometer | A common instrument configuration for nMS, providing high mass accuracy and resolution suitable for analyzing protein-ligand complexes [13]. |

| Fragment Library | A curated collection of 500-2000 small molecules (<300 Da) adhering to the "Rule of Three," designed for high ligand efficiency and synthetic tractability [27] [29] [28]. |

The invention of electrospray ionization was a catalyst for a new era in analytical biochemistry, fundamentally enabling the direct interrogation of noncovalent complexes by mass spectrometry. As detailed in this guide, native MS has matured into a powerful, information-rich technique within the FBDD pipeline. Its ability to directly detect fragment binding, quantify affinities, and determine stoichiometries in a label-free, low-consumption manner makes it an invaluable component of the modern drug hunter's toolkit. By integrating nMS with other structural and biophysical methods, researchers can more efficiently navigate the path from weak fragment hits to potent, novel therapeutics, particularly for challenging targets once considered "undruggable."

The invention of electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry has fundamentally transformed the landscape of clinical diagnostics, creating a bridge between the solution-phase chemistry of biological molecules and the gas-phase analysis capabilities of mass spectrometers. This technique, for which John B. Fenn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002, enables the gentle ionization of non-volatile, thermally labile biomolecules directly from liquid solutions, allowing them to be transferred intact into the mass spectrometer for analysis [1] [33]. Within clinical diagnostics, this capability has opened new frontiers in the detection and characterization of metabolic disorders and hemoglobinopathies—two major categories of inherited conditions with significant global health impacts.

The core innovation of ESI lies in its ability to produce ions from macromolecules without causing extensive fragmentation. When a high voltage is applied to a liquid containing the analytes, it creates an aerosol of charged droplets that undergo solvent evaporation and Coulomb fission, eventually yielding gas-phase ions [1]. The process enables the analysis of complex biological mixtures and has proven particularly valuable for detecting subtle molecular alterations characteristic of inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) and hemoglobin variants. ESI's "soft ionization" characteristics make it ideal for preserving non-covalent interactions and detecting labile metabolites that would be destroyed by harsher ionization methods, providing clinicians with a powerful tool for precise diagnostic characterization [34].

This technical guide examines the application of ESI-MS and complementary mass spectrometry techniques within two critical areas of clinical diagnostics: neonatal screening for IEM and identification of hemoglobin variants. We will explore established methodologies, experimental protocols, and emerging innovations that are enhancing diagnostic accuracy, throughput, and accessibility in modern laboratory medicine.

Technical Foundation: ESI-MS Mechanisms and Diagnostic Advantages

Fundamental Principles of Electrospray Ionization

The ESI process transforms analytes in solution to gas-phase ions through several precisely orchestrated stages. A liquid sample containing the analytes is pumped through a capillary to which a high voltage (typically 2-5 kV) is applied, creating a Taylor cone and emitting a fine aerosol of charged droplets at atmospheric pressure [1]. These charged droplets, stabilized by the surface tension of the solvent, shrink through solvent evaporation while maintaining their charge. As the droplet radius decreases, the charge density increases until reaching the Rayleigh limit, at which point Coulomb fission occurs—the droplet divides into smaller, stable progeny droplets [1]. This process repeats until completely desolvated gas-phase ions are produced, which are then sampled into the mass spectrometer through a capillary carrying a potential difference of approximately 3000 V.

Two primary models explain the final production of gas-phase ions: the Charge Residue Model (CRM) for larger biomolecules like proteins, where the analyte incorporates the charge as the solvent evaporates completely; and the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM) for smaller ions, where field desorption of solvated ions occurs from the droplet surface before complete solvent evaporation [1]. The efficiency of generating gas-phase ions varies significantly depending on compound structure, solvent composition, and instrumental parameters, with differences in ionization efficiency exceeding one million times for different small molecules [1].

Comparative Advantages for Clinical Applications

ESI-MS offers several distinctive advantages that make it particularly suitable for clinical diagnostic applications:

- Direct Analysis of Complex Biological Mixtures: ESI-MS enables direct probing of reacting species within liquids, allowing for efficient characterization and investigation of reaction intermediates directly from "real-world" solutions without extensive sample preparation [34].

- Preservation of Solution-Phase Information: The gentle ionization process retains non-covalent interactions and enables the study of protein folding, protein-ligand complexes, and other biologically relevant structures that would be disrupted by harsher ionization methods [1].

- High Sensitivity and Selectivity: ESI-MS provides outstanding sensitivity, selectivity, and speed for providing structural information including mass-to-charge ratio, isotopic distribution, fragmentation pattern, and ion signal intensity for multiple analytes simultaneously [34].

- Compatibility with Separation Techniques: The atmospheric pressure ionization process makes ESI ideally suited as an interface for liquid chromatography (LC) and capillary electrophoresis (CE), enabling powerful multidimensional separation and analysis of complex biological samples [34] [35].

Table 1: ESI-MS Technical Characteristics Relevant to Clinical Diagnostics

| Characteristic | Technical Specification | Diagnostic Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Ionization Type | Soft ionization | Preserves labile metabolites and protein structures |

| Mass Accuracy | <5 ppm with modern HR-MS | Confidently distinguishes hemoglobin variants with mass differences <1 Da |

| Sample Consumption | Low volume (µL to nL range) | Suitable for neonatal samples with limited volume |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to minutes per sample | Enables high-throughput screening programs |

| Dynamic Range | 2-5 orders of magnitude | Simultaneously detects abundant and trace metabolites |

Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism

Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Significance

Inborn errors of metabolism represent a group of more than 500 inherited disorders caused by defects in specific enzymes or transport proteins that mediate metabolic pathways. These conditions collectively affect approximately 1 in 2,500 live births and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality if not identified and managed early [36]. Traditional screening methods for IEM relied primarily on bacterial inhibition assays (the "Guthrie tests"), which, while effective for specific disorders, lack the comprehensiveness needed to detect the full spectrum of metabolic diseases.

The application of mass spectrometry, particularly through ESI and GC-MS methodologies, has revolutionized IEM screening by enabling simultaneous analysis of multiple metabolite classes. This approach allows accurate chemical diagnosis through urinary or blood spot analyses with simple, practical procedures that can be automated for high-throughput applications [36]. The comprehensive nature of MS-based screening means that a large number of metabolic disorders can be tested simultaneously, significantly expanding the capabilities of neonatal screening programs beyond what was possible with previous technologies.

Experimental Protocol: Urinary Metabolite Profiling for IEM Screening

Sample Preparation:

- Collection: Obtain urine samples absorbed into filter paper (neonates) or 1-2 mL fresh urine (older patients).

- Urease Treatment: Incubate 100 μL urine eluate with urease to reduce high urea concentration that can interfere with analysis.

- Deproteinization: Add 300 μL alcohol to precipitate proteins, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Derivatization: Transfer supernatant to a new vial, evaporate to dryness under nitrogen stream, and add 50 μL of MSTFA (N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide) for trimethylsilylation at 60°C for 30 minutes.

Instrumental Analysis:

- GC-ESI-MS Conditions:

- Column: DB-5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness)

- Oven Program: 60°C (1 min hold) to 300°C at 10°C/min

- Injector Temperature: 250°C

- Ion Source Temperature: 230°C

- Transfer Line Temperature: 280°C

- Ionization Mode: Electron impact (70 eV) or ESI in negative/positive mode

- Mass Range: m/z 50-650

Data Analysis:

- Metabolite Identification: Compare retention times and mass spectra to authentic standards in reference libraries.

- Quantification: Use internal standards (deuterated analogs) for precise quantification of key metabolites.

- Pattern Recognition: Implement multivariate statistical analysis to identify abnormal metabolite patterns suggestive of specific IEM.

The entire sample preparation process takes approximately one hour for individual samples or three hours for batches of 30 samples, with GC/MS measurement completed within 15 minutes per sample [36]. This efficiency makes the method suitable for large-scale neonatal screening programs.

Table 2: Key Metabolic Disorders Detectable by ESI-MS and GC-MS Screening

| Disorder Category | Representative Conditions | Characteristic Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Acidemias | Methylmalonic acidemia, Propionic acidemia, Isovaleric acidemia | Elevated C3, C3-DC, C4, C5 acylcarnitines; specific organic acids |

| Amino Acidopathies | Phenylketonuria, Maple Syrup Urine Disease, Homocystinuria | Elevated phenylalanine, branched-chain amino acids, homocysteine |

| Fatty Oxidation Disorders | MCAD deficiency, VLCAD deficiency | Specific acylcarnitine profiles (e.g., elevated C8 for MCAD) |

| Urea Cycle Disorders | Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, Citrullinemia | Elevated glutamine, alanine, citrulline, arginine |

| Carbohydrate Disorders | Galactosemia | Elevated galactose, galactitol, galactonate |

Data Interpretation and Clinical Correlation

Effective interpretation of IEM screening results requires integration of quantitative data with clinical information. The following workflow diagram illustrates the stepwise process from sample analysis to diagnostic confirmation:

Diagram 1: IEM Screening Diagnostic Workflow

Positive screening results must be confirmed through secondary testing, which may include quantitative amino acid analysis, acylcarnitine profiling, enzyme activity assays, or molecular genetic testing. The comprehensive nature of MS-based screening allows detection of over 20 different metabolic disorders in a single analytical run, significantly expanding the capabilities of neonatal screening programs compared to traditional methodologies [36].

Analysis of Hemoglobin Variants

Clinical Significance of Hemoglobinopathies

Hemoglobinopathies represent the most common inherited disorders worldwide, with over 1000 hemoglobin variants characterized to date. While most are clinically silent, approximately 150 variant hemoglobins cause significant disease manifestations including hemolytic anemia, cyanosis, erythrocytosis, and other serious complications [37]. The most clinically significant variants include Hb S (sickle cell, β6 Glu→Val), Hb C (β6 Glu→Lys), Hb E (β26 Glu→Lys), and Hb D-Punjab (β121 Glu→Gln), which collectively affect millions of people globally [37].