Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: Principles, Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Electrospray Ionization (ESI) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: Principles, Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Electrospray Ionization (ESI) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational mechanism of ESI, from charged droplet formation to gas-phase ion release. The article details its pivotal methodological applications in clinical diagnostics, drug discovery, and metabolomics, and offers systematic strategies for parameter optimization and troubleshooting. A comparative analysis with complementary ionization techniques like APPI is included to guide method selection. The review concludes by examining emerging trends and the future impact of ESI and related techniques on biomedical research and clinical applications.

The Core Mechanism of Electrospray Ionization: From Liquid Solution to Gas-Phase Ions

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that has revolutionized the analysis of biomacromolecules by enabling their transfer from a liquid solution to the gas phase as intact ions, making them amenable to mass spectrometric analysis [1]. This process is pivotal in modern research for studying proteins, peptides, and other complex biological molecules, as it overcomes their propensity to fragment and allows for the determination of very high molecular weights by producing multiply charged ions [1]. The mechanism can be fundamentally broken down into three essential steps: the dispersal of a charged aerosol, the evaporation of the solvent, and the final ejection of gas-phase ions.

The Electrospray Ionization Mechanism

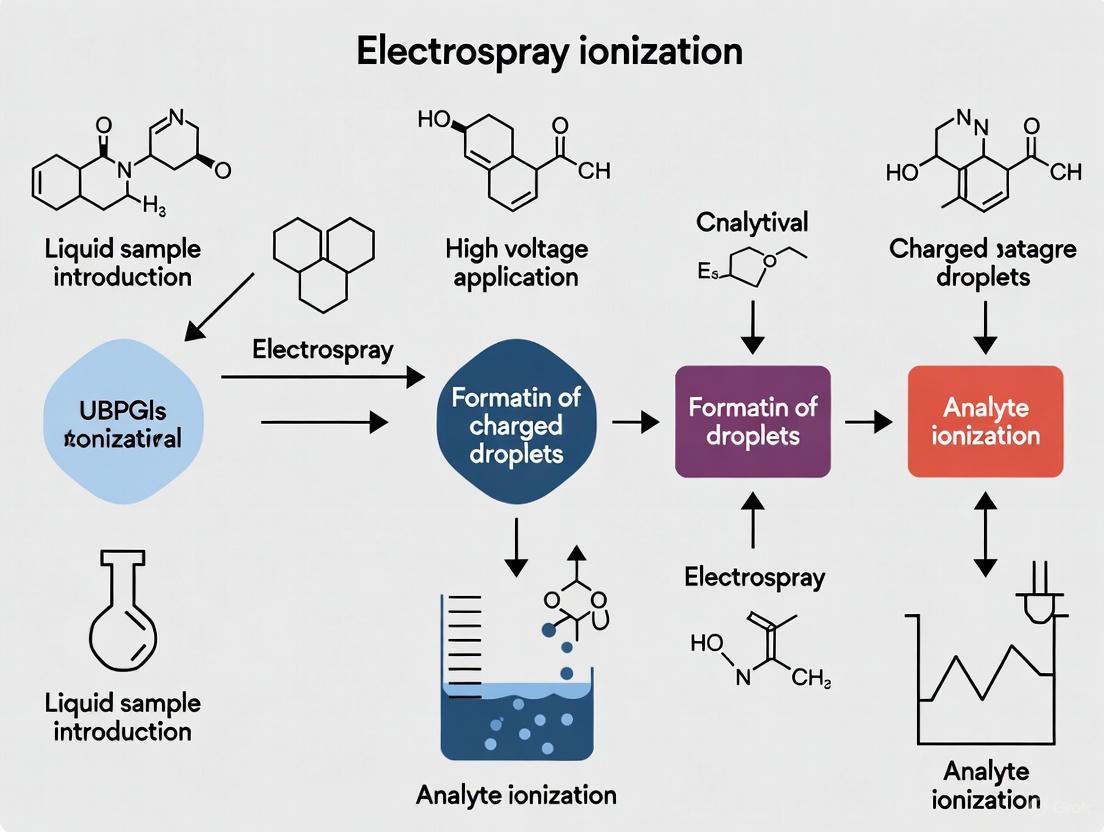

The following diagram illustrates the complete ESI process, from the application of high voltage to the generation of gas-phase ions, encompassing the three core stages.

Diagram 1: The three-step ESI process, from charged droplet formation to gas-phase ion generation.

Stage 1: Droplet Formation and Dispersal

The process initiates when a sample solution is pushed through a fine metal capillary (electrospray needle) held at a high voltage, typically between 2.5 to 6.0 kV [2] [3]. This high electric field charges the surface of the liquid emerging from the tip. The mutual electrostatic repulsion between the like charges counteracts the liquid's surface tension, deforming the meniscus into what is known as a Taylor cone [1]. When the electrostatic forces overcome the surface tension, the cone's tip elongates and disperses the liquid into a fine mist or aerosol of highly charged droplets [2] [4]. The application of a nebulizing gas (such as nitrogen) shearing around the liquid stream can enhance this process, allowing for higher sample flow rates [2].

Stage 2: Solvent Evaporation and Droplet Shrinking

The cloud of charged droplets is directed towards the mass spectrometer's inlet, which is at a lower pressure. As the droplets travel, the solvent begins to evaporate, a process often assisted by a counter-current flow of a heated drying gas (like nitrogen) and the application of heat within the ESI source [1] [2]. This continuous solvent loss reduces the droplet's size while its charge remains constant. Consequently, the charge density on the droplet's surface increases significantly. This leads to an inevitable point where the electrostatic repulsion between the charges rivals the surface tension holding the droplet together—a threshold known as the Rayleigh limit [1].

Stage 3: Ion Ejection via Coulomb Fission and Desorption

Upon reaching the Rayleigh limit, the droplet becomes unstable and undergoes Coulomb fission, disintegrating into smaller, progeny droplets [1]. This "explosive" event relieves a portion of the charge (typically 10-18%) and mass (1.0-2.3%) [1]. These smaller droplets continue the cycle of solvent evaporation and Coulomb fission until the conditions are right for the final release of gas-phase ions. The mechanism for this final step is explained by two primary models [1] [3]:

- Charged Residue Model (CRM): Progeny droplets become so small that they contain, on average, one analyte molecule. The remaining solvent evaporates completely, leaving the analyte with the droplet's charges [1]. This model is generally accepted for large, folded proteins [1].

- Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): For small droplets at a critical radius, the electric field strength at the surface becomes intense enough to directly desorb (field-evaporate) solvated ions into the gas phase before the solvent fully evaporates [1]. This is thought to be the dominant mechanism for smaller ions [1].

The resulting gas-phase ions are typically protonated molecules [M+H]⁺, deprotonated molecules [M-H]⁻, or adducts with other cations like sodium [M+Na]⁺ [1]. For large macromolecules, ESI famously produces a spectrum of multiply charged ions [M+nH]ⁿ⁺, which effectively extends the mass range of the mass spectrometer and allows for the accurate mass determination of kDa-MDa molecules [1] [3].

Key Experimental Parameters and Reagent Solutions

Successful ESI analysis requires careful optimization of several parameters. The table below summarizes the core components and their functions in a typical ESI-MS setup.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and ESI-MS Components

| Component | Function & Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Sample Solvent | Typically a mixture of water with volatile organic compounds (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) to facilitate droplet formation and solvent evaporation [1]. |

| Acid Additives | Compounds like acetic or formic acid are added to increase solution conductivity and provide a source of protons to facilitate the ionization of analytes [1]. |

| Nebulizing Gas | An inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) that shears the liquid stream to enhance aerosol formation and stabilize the electrospray, especially at higher flow rates [2]. |

| Drying Gas | A stream of heated, inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) directed at the spray to accelerate solvent evaporation from the charged droplets [2]. |

| Metal Capillary | The emitter tip where the high voltage is applied to create the Taylor cone and generate the charged aerosol [2]. |

| High-Voltage Power Supply | Applies a high potential (2.5–6.0 kV) to the capillary relative to the spectrometer inlet, providing the electric field necessary for electrospray [2] [3]. |

Quantitative Data in ESI-MS Analysis

The unique ability of ESI to generate multiply charged ions transforms the data output, making it essential to understand the quantitative relationships for accurate mass determination.

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships in an ESI Mass Spectrum of a Protein

| Multiply Charged Ion | m/z Ratio Calculation (for Mr = 15,000 Da) | Resulting m/z |

|---|---|---|

| [M + 6H]⁶⁺ | (15000 + 6) / 6 | 2501 |

| [M + 5H]⁵⁺ | (15000 + 5) / 5 | 3001 |

| [M + 4H]⁴⁺ | (15000 + 4) / 4 | 3751 |

| [M + 3H]³⁺ | (15000 + 3) / 3 | 5001 |

| [M + 2H]²⁺ | (15000 + 2) / 2 | 7501 |

| [M + H]⁺ | (15000 + 1) / 1 | 15001 |

The molecular mass (Mr) of an unknown analyte can be calculated from two adjacent charge states in the mass spectrum, p₁ and p₂, where p₁ has the lower m/z value and a charge of z₁, and p₂ has a charge of z₁ - 1 [4]. The relevant formulas are:

- p₁ = (Mᵣ + z₁) / z₁

- p₂ = [Mᵣ + (z₁ - 1)] / (z₁ - 1)

Advanced ESI Methodologies and Protocols

Coupling with Liquid Chromatography (LC-ESI-MS)

For complex mixtures like protein digests or biological fluids, ESI is almost universally coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [2]. The HPLC system acts as a front-end separation tool, fractionating the sample and introducing purified analytes directly into the ESI source. This prevents signal suppression and simplifies the mass spectrum, making it a fundamental protocol for proteomics and metabolomics [2].

Tandem Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) for Structural Elucidation

To gain structural information, ESI is frequently paired with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). A typical protocol using a triple quadrupole instrument involves [2]:

- Mass Selection: The first quadrupole (Q1) is set to isolate the precursor ion of interest.

- Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID): The selected ions are passed into a second quadrupole (Q2), which acts as a collision cell filled with an inert gas like argon. The kinetic energy of the ions is converted into vibrational energy upon collision, causing the precursor ions to fragment.

- Mass Analysis of Fragments: The resulting product (daughter) ions are mass-analyzed by the third quadrupole (Q3). This fragmentation pattern provides critical information for sequencing peptides or confirming molecular structures [2].

Common MS/MS acquisition modes include the Product Ion Scan for structural elucidation and Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for highly sensitive and specific quantitative analysis [2].

The elegant, three-step process of dispersal, evaporation, and ion ejection makes electrospray ionization a cornerstone technique in modern analytical science. Its capacity to gently bring fragile biomacromolecules into the gas phase for mass analysis has been instrumental in advancing fields from structural biology to drug discovery. By enabling the analysis of highly complex mixtures through coupling with liquid chromatography and providing deep structural insights via tandem mass spectrometry, ESI continues to be an indispensable tool in the researcher's arsenal, driving forward our understanding of biological systems at a molecular level.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) has revolutionized the analysis of biomolecules, enabling the study of proteins, peptides, and other large, non-volatile compounds by mass spectrometry (MS) [2]. The technique transforms analytes in solution into gas-phase ions, making them amenable to mass analysis. The efficiency of this process hinges on two fundamental and interconnected electrohydrodynamic phenomena: Taylor cone formation and Coulomb fission [5]. A deep understanding of these principles is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to optimize ESI-MS methods, particularly for applications in proteomics, metabolomics, and therapeutic drug monitoring[cite:3]. This guide provides a detailed examination of the theory, experimental observations, and practical methodologies surrounding these critical events.

Fundamental Theory and Definitions

The Taylor Cone

A Taylor cone is a conical deformation that forms at the surface of a conductive liquid when it is subjected to a sufficiently strong electric field [6]. This occurs at the tip of the ESI emitter, where the applied voltage creates an electric field strong enough to overcome the surface tension of the liquid.

- Formation Mechanism: When a voltage (typically 2–6 kV) is applied to a capillary tube containing the liquid sample, free charges (e.g., ions) within the liquid migrate to the liquid-air interface [6] [2]. The electric stress exerted on the surface pulls the liquid toward the counter-electrode, elongating the initially hemispherical meniscus. A stable, conical shape is achieved when the electric stress precisely balances the restoring force of the liquid's surface tension [7]. British physicist Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor theoretically predicted and experimentally verified this equilibrium shape in 1964, demonstrating that it is characterized by a specific semi-vertical angle of 49.3° (a whole angle of 98.6°) [6] [7].

- The Cone-Jet and Ion Emission: The stable Taylor cone represents an equilibrium state. However, when the electric field intensity at the cone's apex exceeds a critical threshold, this equilibrium is disrupted, and the cone's tip elongates into a fine liquid jet [6] [8]. It is from the apex of this jet that charged droplets are emitted into the gas phase. This "cone-jet" mode is the desired operational state for a stable electrospray [7].

Coulomb Fission (Droplet Fission)

The charged droplets produced by the Taylor cone jet undergo a process of solvent evaporation while traveling through the mass spectrometer's atmosphere-vacuum interface. As a droplet shrinks in size, its charge density increases. Coulomb fission is the process wherein a charged droplet becomes unstable and disintegrates into smaller progeny droplets.

The Rayleigh Limit: The stability limit for a charged droplet is described by Lord Rayleigh's equation [9] [5]:

z_R = 8π(ε₀γR³)¹ᐟ²Here,

z_Ris the maximum, or Rayleigh charge limit;Ris the droplet radius;γis the surface tension; andε₀is the permittivity of free space. When the charge on the droplet (z) reaches or exceeds this limit (z ≥ z_R), the Coulombic repulsion between the charges overcomes the cohesive surface tension, and the droplet undergoes fission [9].- Fission Pathways: Experimental studies, particularly using Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CDMS), have revealed that fission in submicrometer aqueous nanodrops is highly heterogeneous. Four distinct pathways have been identified [9]:

- Continuous Pathway: Many small progeny droplets are sequentially emitted over tens to hundreds of milliseconds.

- Prompt Pathway: A single, larger fission event ejects one or a limited number of progeny droplets carrying a significant fraction of the precursor's charge. This is the most common pathway.

- Sequential Prompt Pathway: Multiple prompt fission events occurring in sequence.

- Prefission Pathway: The emission of a few charges precedes a larger prompt fission event, analogous to "foreshocks" before an earthquake.

The continuous cycle of solvent evaporation and Coulombic fission repeatedly divides the initial droplets until the analyte ions are liberated into the gas phase, ready for mass analysis [2] [5].

Table 1: Core Principles of Taylor Cone and Coulomb Fission

| Feature | Taylor Cone | Coulomb Fission |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Physics | Balance between electric stress and surface tension | Balance between Coulombic repulsion and surface tension |

| Governing Equation | N/A (Equilibrium of forces) | Rayleigh Limit: z_R = 8π(ε₀γR³)¹ᐟ² [9] |

| Key Parameter | Semi-vertical angle of 49.3° [6] [7] | Charge-to-radius ratio (z / R) |

| Primary Outcome | Formation of a charged liquid jet and droplets [6] | Breakup of parent droplet into smaller progeny droplets [9] |

| Role in ESI | Initial droplet formation and charging | Droplet downsizing and eventual gas-phase ion release [5] |

Experimental Observations and Quantitative Data

Direct measurement of nanodrop fission became possible with techniques like Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CDMS). This method allows for simultaneously tracking the mass, charge, and energy per charge of individual trapped droplets over time, providing unprecedented insight into fission dynamics [9].

Key Findings from CDMS Experiments

A 2025 study using CDMS analyzed 846 trapped aqueous nanodrops, of which 154 (18.2%) underwent spontaneous fission. The charges of these droplets ranged from 44% to 158% of the Rayleigh limit, confirming that fission can occur both below and significantly above the theoretical limit [9]. The study quantified the mass and charge losses during these events, revealing the diversity of fission pathways.

Table 2: Experimental Fission Data from CDMS Studies [9]

| Fission Parameter | Observed Range | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Fission | 18.2% of trapped nanodrops | Charges ranged from 44-158% of the Rayleigh limit. |

| Charge Loss per Fission Event | 4% - 40% of parent charge | Varies significantly by pathway; prompt events involve larger losses. |

| Mass Loss per Fission Event | < 5% of parent mass | Generally low mass loss is a characteristic of Coulomb fission. |

| Fission Time Scale | < 1 ms to 100s of ms | Ranges from near-instantaneous (prompt) to prolonged (continuous). |

| Number of Progeny Droplets | A few to hundreds | Highly heterogeneous, dependent on the fission pathway. |

Historical and Supporting Data

Earlier theoretical and experimental work aligns with these modern observations. A 1999 model assumed an average mass loss of 2% and a charge loss of 15% per fission event based on prior optical resonance measurements [5]. This model further calculated that the size ratio of progeny droplets to the initial parent droplet is a function of the number of progeny droplets generated, highlighting the inherent variability of the process [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To investigate Taylor cone formation and Coulomb fission, robust experimental setups are required. Below are detailed methodologies for key approaches.

Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CDMS) for Fission Analysis

This protocol is adapted from recent studies on spontaneous fission of aqueous nanodrops [9].

- Objective: To track the mass, charge, and energy per charge of individual nanodrops in real-time to observe and characterize fission events.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Nanodrop Source: Deionized water (resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm).

- Emitter: Borosilicate emitters (e.g., 1.0 mm outer diameter, 0.78 mm inner diameter) pulled to an inner tip diameter of ~18–20 μm.

- High Voltage Source: Capable of delivering 2.4–2.7 kV to a platinum wire inserted into the emitter.

- Instrumentation: A custom-built electrostatic ion trap charge detection mass spectrometer, equipped with:

- Heated inlet capillary (e.g., 80 °C).

- Ion funnel and sequential quadrupole ion guides.

- An electrostatic cone trap with a cylindrical detector electrode.

- A vacuum chamber housing the trap at ~1 × 10⁻⁸ Torr.

- Methodology:

- NanoESI Generation: Position the nanoESI emitter ~3 mm from the instrument inlet. Apply a voltage of 2.4–2.7 kV to the platinum wire in contact with the water to initiate electrospray and generate positively charged nanodrops [9].

- Ion Trapping: The nanodrops enter through the heated capillary, are focused by the ion funnel and quadrupoles, and are subsequently pulsed into the electrostatic cone trap. The trap is operated with a low ion current to ensure single-ion analysis and avoid ion-ion interactions.

- Data Acquisition: Trap individual nanodrops for up to 4 seconds. The current induced by the charged nanodrop on the cylindrical detector is recorded continuously. This signal is used to determine the ion's mass (

m), charge (z), and mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) throughout the trapping period. - Signal Processing: Perform Short-time Fourier Transform (STFT) analysis on the time-domain data (e.g., using a 25 ms window length and 5 ms step size) to trace oscillation frequencies, which are sensitive to changes in mass and charge.

- Data Analysis:

- Manually inspect all STFT frequency traces for sudden drops indicative of fission events.

- Classify events into fission pathways (continuous, prompt, sequential prompt, prefission).

- Calculate mass and charge losses by averaging measurements from 50 ms before and after a fission event.

- Determine the droplet diameter from the measured mass using a spherical water model.

- Compute the fraction of the Rayleigh limit from the measured charge and diameter using Equation 1.

Visualizing Taylor Cone Formation

This protocol describes a classic setup for observing the Taylor cone, based on historical and contemporary practices [6] [7].

- Objective: To generate and optically observe a stable Taylor cone in a laboratory setting.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Capillary: A metallic (e.g., stainless steel) capillary or needle with an inner diameter of 0.1 to 1 mm.

- Syringe Pump: For precise control of liquid flow rates (nL/min to μL/min).

- High Voltage DC Power Supply: Capable of delivering 2 to 20 kV.

- Counter-Electrode: A grounded metallic plate.

- Conducting Liquid: Water or an aqueous solution.

- Safety Equipment: Proper insulation, grounding, and shielding.

- Imaging System: A high-speed camera with a macro lens.

- Methodology:

- Setup: Connect the capillary to the syringe pump filled with the conducting liquid. Position the counter-electrode 5 to 50 mm away from the capillary tip, ensuring alignment.

- Initialization: Start the syringe pump at a low flow rate (e.g., 1 μL/min). Gradually increase the voltage from the power supply applied to the capillary.

- Observation: As the voltage approaches a critical threshold (e.g., 1–5 kV, depending on geometry and liquid), the meniscus will deform from hemispherical to a convex cone and finally to a stable Taylor cone with a jet emitting from its apex.

- Optimization: Adjust the flow rate and voltage to achieve a stable "cone-jet" mode. Ambient conditions like humidity should be monitored as they can affect stability.

- Validation: Capture images of the cone. Measure the semi-vertical angle to confirm it approximates the theoretical value of 49.3°.

Visualization of Processes and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical sequence of electrospray ionization and the specific experimental workflow for CDMS, as discussed in this guide.

Electrospray Ionization Process

Diagram 1: The ESI process, showing the cyclical nature of evaporation and fission leading to gas-phase ions.

CDMS Fission Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: The workflow for analyzing droplet fission using Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key items for studying Taylor cone formation and Coulomb fission.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Role | Specifications / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Liquid | Forms the Taylor cone and charged droplets; the medium for analyte transport. | High-purity deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity) [9]. Solvents like methanol or acetonitrile for LC-ESI-MS. |

| ESI Emitter | The physical tip from which the Taylor cone and jet are formed. | Borosilicate glass capillaries pulled to fine tips (e.g., 18-20 μm inner diameter) [9]. Metal capillaries for some applications. |

| Supercharging Reagents | Increase the charge state of analyte ions, influencing fission dynamics and ion yield. | Sulfolane, m-nitrobenzyl alcohol (mNBA), glycerol. Typically added at <0.5% v/v [10]. |

| High-Voltage Power Supply | Provides the electric field necessary for Taylor cone formation. | Capable of delivering 2-20 kV DC [6]. |

| Syringe Pump | Precisely controls the flow rate of the liquid to the emitter for stable cone-jet operation. | Capable of delivering flow rates from nL/min to μL/min [6]. |

| Charge Detection Mass Spectrometer | The primary instrument for directly measuring mass and charge of individual droplets to study fission. | Custom-built or commercial instruments with single-ion trapping capabilities [9]. |

Generation of Multiply Charged Ions and its Impact on Analyzing Macromolecules

The analysis of macromolecules, such as proteins and protein complexes, has been revolutionized by the ability to generate multiply charged ions in the gas phase. This phenomenon effectively extends the mass range of mass spectrometers by reducing the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of large biomolecules, making them compatible with conventional mass analyzers [1]. Electrospray ionization (ESI) has emerged as a pivotal technique in this field, enabling the transfer of ions from solution into the gaseous phase through the application of electrical energy [2]. The multiple charging phenomenon is particularly crucial for the analysis of high-mass biological complexes, as it produces ions of relatively low m/z, making ESI amenable with mass analyzers where high m/z performance is otherwise limited [11]. The generation of multiply charged ions underpins various mass spectrometric applications, from structural characterization to quantitative measurements in clinical and pharmaceutical contexts.

The formation of multiply charged ions is not limited to ESI. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), traditionally known for producing singly charged ions, has also been adapted under specific conditions to generate multiply charged ions. Recent research has demonstrated that homogeneous MALDI microcrystals, when prepared using methods like forced dried droplet (FDD), can produce multiply charged protein ions with charge states as high as +6 for proteins like myoglobin [12]. The control over experimental parameters such as laser fluence and matrix proton affinity (PA) plays a critical role in optimizing the charge state distributions in MALDI, with lower PA matrices (e.g., CHCA at 841 kJ/mol and Cl-CCA at 838.5 kJ/mol) generally resulting in higher charge states compared to higher PA matrices (e.g., CHCA-C3 at 879.5 kJ/mol) [12].

Mechanisms of Multiply Charged Ion Formation

Electrospray Ionization Mechanisms

The electrospray ionization process involves three fundamental steps that facilitate the transfer of ionic species from solution into the gas phase. First, a fine spray of charged droplets is dispersed from a capillary maintained at a high voltage (typically 2.5-6.0 kV). Second, solvent evaporation occurs from these charged droplets, aided by a drying gas and elevated ESI-source temperature. Third, ion ejection takes place from the highly charged droplets as they reach a critical field strength due to continuous solvent evaporation [2]. Two primary models explain the final production of gas-phase ions: the Charge Residue Model (CRM) and the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM). The CRM proposes that electrospray droplets undergo successive evaporation and fission cycles, eventually resulting in progeny droplets containing approximately one analyte ion, with gas-phase ions forming after remaining solvent molecules evaporate [1]. In contrast, the IEM suggests that when droplets reach a critical radius, the field strength at the droplet surface becomes sufficient to assist the field desorption of solvated ions [1].

For large macromolecules such as folded proteins, evidence indicates that ions form predominantly through the charged residue mechanism, while smaller ions (from small molecules) are liberated into the gas phase through the ion evaporation mechanism [1]. A third model, the Chain Ejection Model (CEM), has been proposed specifically for disordered polymers and unfolded proteins [1]. The efficiency of generating gas-phase ions varies significantly depending on compound structure, solvent composition, and instrumental parameters, with differences in ionization efficiency exceeding one million times for different small molecules [1].

Novel Charge Inversion and Ion Attachment Mechanisms

Beyond conventional ESI and MALDI, recent advances have revealed additional mechanisms for manipulating charge states. Charge inversion ion/ion reactions represent a novel approach that converts multiply charged protein cations to multiply charged protein anions via single ion/ion collisions using highly charged anions derived from nano-electrospray ionization of hyaluronic acids [11]. This process has been demonstrated with cations derived from cytochrome c, apo-myoglobin, and carbonic anhydrase, converting, for example, the [CA+22H]²²⁺ cation to a distribution of anions as high in absolute charge as [CA−19H]¹⁹⁻ [11]. This phenomenon is particularly surprising because previous studies involving reactions of multiply-charged ions of opposite polarity have shown ion/ion attachment to dominate, sometimes competing with partial proton transfer [11].

Another significant development is the multiply-charged ion attachment approach, which facilitates the mass measurement of high-mass complexes in native mass spectrometry. This method involves attaching high-mass ions of known mass and charge to populations of ions of interest, leading to well-separated signals that enable confident charge state and mass assignments from otherwise poorly resolved signals [13]. This strategy is particularly valuable for analyzing heterogeneous samples such as ribosome particles, where extensive salt adduction and inherent heterogeneity complicate mass determination [13]. The attachment of multiply-charged reagent ions to analyte complexes generates known Δm and Δz values that are much greater than those achieved through single proton or electron transfer, resulting in large m/z separations that are more readily resolved [13] [14].

Experimental Techniques and Methodologies

Electrospray Ionization Protocols

For standard ESI-MS analysis of proteins, sample preparation involves dissolving the analyte in an appropriate solvent system. A typical protocol involves preparing protein stock solutions at concentrations around 1 mg/mL in LC-MS grade water, then diluting working solutions to 5-20 μM with either pure water for near-neutral pH conditions or water with 0.5-2% acetic acid for denaturing conditions [11]. The addition of acid facilitates analyte protonation, while low surface tension solvents such as methanol promote droplet fission [15]. For nano-ESI, which operates at lower flow rates (nL/min to μL/min) and generates smaller initial droplets, improved ionization efficiency can be achieved [1]. The emitter voltage typically ranges from +1500 V for positive mode analysis of large complexes to -1400 V for negative mode analysis [13] [14].

Liquid chromatography coupling with ESI-MS requires additional optimization. When interfacing size exclusion chromatography with MS, isocratic conditions with MS-friendly mobile phases of low ionic strength are employed. For example, a protocol for separating transferrin and β-galactosidase used 50 mM ammonium acetate in LC-MS grade water as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.05 mL/min [16]. The column temperature is maintained at 25°C, and UV detection at 280 nm enables monitoring of the separation prior to MS analysis [16].

Ion/Ion Reaction Methodology

The experimental setup for ion/ion reactions typically employs a modified QTOF mass spectrometer capable of mutual storage of cations and anions [11] [13] [14]. The general procedure involves:

- Generating analyte ions via nano-ESI under native conditions

- Isolating targeted protein ions in the first quadrupole (Q1)

- Transferring isolated ions to the linear ion trap reaction cell (q2)

- Generating reagent ions via nano-ESI under denaturing conditions

- Isolating reagent ions in Q1 and transferring them to q2

- Mutually storing both ion populations in q2 for reaction times of 5-100 ms

- Mass-analyzing the products using time-of-flight detection [11] [13]

For ion attachment experiments, the reagent ion number density is varied by altering the voltage and injection time to optimize reactions [14]. Nitrogen gas is used in q2 at pressures ranging from 6-8 mtorr to facilitate collisions [13]. When analyzing large complexes like ribosome particles, the DC offsets between different regions are increased (e.g., 50-70 V between Q0 and q2) to collisionally activate the ions upon injection and drive off weakly-bound adduct species [13].

Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CDMS) Protocols

Charge detection mass spectrometry represents an alternative approach for analyzing macromolecules and heterogeneous complexes. CDMS enables direct measurement of both the m/z ratio and the charge of individual ions, circumventing the need for charge state resolution or deconvolution [17] [16]. Sample preparation for CDMS typically involves buffer exchange into volatile ammonium acetate solutions (e.g., 100 mM) using centrifugal filters or size exclusion chromatography columns [16]. For static nano-ESI direct infusion, proteins are diluted in 100 mM aqueous ammonium acetate to final concentrations of approximately 2 μM [16].

CDMS experiments are performed using specialized instrumentation, such as Q Exactive UHMR hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometers equipped with an ExD cell, which is autotuned for transmission of the specific proteins being analyzed [16]. Data acquisition times for CDMS typically range from several tens of minutes to hours to collect sufficient individual ion measurements for statistical significance [16]. Recent advances include the implementation of automatic ion control (AIC), which regulates ion flux based on signal density along the m/z axis rather than predefined injection times, facilitating the coupling of CDMS with liquid chromatography separation [16].

Analytical Applications in Macromolecular Analysis

Protein and Protein Complex Characterization

The generation of multiply charged ions has dramatically advanced the characterization of proteins and protein complexes. In native mass spectrometry, ESI under non-denaturing conditions preserves non-covalent interactions, enabling the study of protein-ligand, protein-protein, and protein-nucleic acid complexes [13]. The multiple charging phenomenon produces ions with relatively low m/z values despite their high molecular weights, making them amenable to analysis by conventional mass spectrometers. However, native conditions typically yield narrow charge state distributions, which can complicate mass measurement [13] [14].

Table 1: Multiply-Charged Ion Applications in Protein Analysis

| Application | Key Information | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Native MS | Preserves non-covalent complexes; narrow charge state distributions | Pyruvate kinase tetramer; Ferritin; GroEL [13] |

| Charge Inversion | Converts cations to anions via ion/ion reactions | Cytochrome c; Apo-myoglobin; Carbonic anhydrase [11] |

| Ion Attachment | Attaches ions of known mass/charge to determine unknown mass | E. coli ribosome particles; β-galactosidase [13] [14] |

| Charge Detection MS | Direct measurement of mass and charge for individual ions | Transferrin; β-galactosidase; AAVs; IgM oligomers [17] [16] |

The analysis of ribosomal particles exemplifies the challenges and solutions in macromolecular mass spectrometry. The E. coli 70S ribosome solution is typically prepared in buffers containing magnesium acetate to maintain structural integrity, followed by extensive buffer exchange (8 times) with 150 mM ammonium acetate and 10 mM magnesium acetate [14]. The inherent heterogeneity and extensive salt adduction result in significantly broadened peaks that are difficult to resolve using conventional approaches. The attachment of multiply-charged cations (e.g., the 10+ charge state of bovine ubiquitin or the 30+ charge state of bovine carbonic anhydrase) to these ribosomal anions has been shown to resolve multiple components, revealing particles with different combinations of missing components rather than intact 50S particles [14].

Analysis of Heterogeneous Biopharmaceuticals

Multiply charged ions have proven particularly valuable for characterizing heterogeneous biopharmaceuticals. Charge detection MS has been applied to complex molecules such as bispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), gene therapies, and highly glycosylated proteins [17]. These analyses are challenging because traditional native MS requires either isotopic resolution or separation of charge states for mass determination, which becomes difficult with increasing sample heterogeneity [17] [16].

A prominent example is the analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, a trimeric glycosylated protein with potentially 8.2 × 10⁷⁵ possible glycoforms [17]. Traditional glycan analysis cannot provide information about how glycans at particular sites correlate with glycans at other sites on individual molecules. CDMS has demonstrated the capability to characterize this extreme heterogeneity and provide site-specific correlation information for glycans [17]. Similarly, CDMS has been used to characterize a complex mixture of IgM oligomers and co-occurring empty and genome-packed adeno-associated virus (AAV8) particles, where conventional native MS fails due to inability to resolve charge states in these heterogeneous mixtures [17].

Table 2: Mass Spectrometry Techniques for Macromolecular Analysis

| Technique | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional ESI-MS | Multiple charging reduces m/z; Soft ionization | Broad mass range; Minimal fragmentation | Requires charge state resolution for mass determination |

| Ion/Ion Reactions | Charge manipulation via proton transfer or attachment | Charge inversion; Charge state simplification | Requires specialized instrumentation |

| Native MS | Preservation of non-covalent interactions | Study of intact complexes | Narrow charge state distributions; Salt adduction |

| Charge Detection MS | Simultaneous measurement of m/z and charge | No need for charge state resolution; Handles heterogeneity | Lower throughput; Complex data analysis |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful analysis of macromolecules using multiply charged ions requires specific reagents and materials optimized for different applications. The following table summarizes key research reagents and their functions in experimental workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multiply-Charged Ion Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acids | Charge inversion reagents | HA with MW=1155 Da, 8-15k, 50k; HA-dp18 (MW=3412 Da) [11] |

| Protein Standards | Calibration and reagent ions | Cytochrome c; apo-myoglobin; carbonic anhydrase; ubiquitin [11] [14] |

| Ion/Ion Reagents | Multiply-charged ion attachment | Oxidized insulin chain A; holo-myoglobin with piperidine [13] [14] |

| MS Matrices | MALDI matrix compounds | CHCA; Cl-CCA; CHCA-C3; SA (sinapic acid) [12] |

| Buffers/Solvents | Sample preparation and LC mobile phases | Ammonium acetate; ammonium hydroxide; methanol; acetic acid [11] [16] |

| Nano-ESI Emitters | Ion source components | Borosilicate glass emitters [13] |

The choice of specific reagents depends on the experimental goals. For charge inversion experiments, hyaluronic acids of varying molecular weights serve as effective reagents for converting multiply charged protein cations to anions [11]. The relatively high charge densities of HA anions facilitate the extraction of multiple protons from proteins, leading to multiply charged protein anions [11]. For ion attachment applications, proteins such as oxidized insulin chain A (generating [IcA-5H]⁵⁻ and [IcA-6H]⁶⁻ ions) and holo-myoglobin prepared with piperidine serve as effective reagent anions [13]. The preparation of these reagents typically involves reconstituting lyophilized solids in appropriate solvents, with denaturing conditions (e.g., 50:50 H₂O:methanol with 1-5% glacial acetic acid) used to ensure higher charge state formation [14].

For MALDI applications, matrices with specific proton affinities are crucial for generating multiply charged ions. CHCA (PA = 841 kJ/mol) and Cl-CCA (PA = 838.5 kJ/mol) have been shown to produce higher charge states (up to +6 for myoglobin) compared to higher PA matrices like CHCA-C3 (PA = 879.5 kJ/mol) [12]. Homogeneous sample preparation using methods like forced dried droplet (FDD) is essential for reproducible multiply charged ion signals, with average RSD values of ~10-20% achieved for myoglobin samples with different matrices [12].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The analysis of macromolecules via multiply charged ions involves sophisticated instrumental setups and workflows. The following diagram illustrates a typical ion/ion reaction workflow for charge state manipulation and mass analysis.

The generation of multiply charged ions has fundamentally transformed the analysis of macromolecules, enabling mass spectrometric characterization of proteins, protein complexes, and other large biomolecules that were previously intractable. Electrospray ionization serves as the cornerstone technique for producing multiply charged ions, with ongoing advancements in ionization mechanisms, including novel charge inversion and ion attachment approaches. The experimental methodologies continue to evolve, providing researchers with powerful tools for investigating macromolecular structure and function. As mass spectrometry technology advances, the ability to generate and manipulate multiply charged ions will undoubtedly continue to expand the frontiers of macromolecular analysis, particularly for heterogeneous samples that challenge conventional analytical approaches. The integration of these techniques with separation methods and the development of specialized reagents and protocols will further enhance their application in both basic research and biopharmaceutical development.

Electrospray ionization (ESI), once primarily an analytical tool for mass spectrometry, has emerged as a platform for accelerated chemical synthesis. This transformation is driven by the recognition that microdroplets generated during ESI exhibit extraordinary reaction acceleration—up to a million-fold faster than conventional bulk-phase chemistry. This whitepaper explores the mechanistic basis for this phenomenon, focusing on the role of field ionization and chemical ionization in creating a unique reactive environment at microdroplet interfaces. The implications of these processes extend from fundamental understanding of ESI mechanisms to practical applications in pharmaceutical research, green chemistry, and prebiotic synthesis [18] [19].

From Analytical Tool to Synthetic Platform

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) has traditionally served as a technique for transferring analytes from solution to the gas phase for mass analysis. Over the past decade, this role has expanded dramatically with the observation that microdroplets themselves function as microscopic reactors where chemical transformations occur at dramatically enhanced rates. This discovery has bridged the domains of chemical analysis and synthesis, enabling reactions that proceed rapidly without catalysts or pH adjustment under ambient conditions [18].

The significance of microdroplet chemistry lies in its dual utility: it provides a mechanism for ionization in ESI-MS while simultaneously facilitating rapid chemical synthesis. This dual function has prompted reevaluation of fundamental ESI mechanisms and opened new avenues for synthetic chemistry, particularly in contexts requiring rapid reaction screening or minimal reagent consumption [19].

Distinctive Features of Microdroplet Reactions

Several characteristic features distinguish microdroplet chemistry from conventional solution-phase reactions:

- Reaction acceleration up to 10⁶ times compared to bulk-phase analogs

- Interfacial phenomenon with demonstrated size-dependent effects

- Water dependency with minimal acceleration observed in completely dry solvents

- Strong electric fields at the air/water interface measuring ~10⁹ V/m

- Incomplete solvation of reagents reducing activation barriers

- Broad reaction scope including redox, condensation, hydrolysis, and substitution reactions

- Green chemistry attributes with reactions typically occurring without catalysts under ambient conditions [19]

These distinctive characteristics have been established through empirical investigation, but a coherent mechanistic explanation accounting for both the enhanced rates and diverse reaction types has remained elusive until recently.

Proposed Mechanism: Field Ionization and Chemical Ionization

Core Conceptual Framework

The proposed mechanism unifying diverse observations in microdroplet chemistry centers on two sequential processes: field ionization (FI) followed by chemical ionization (CI). This mechanism explains both molecular ionization for mass spectrometric detection and the dramatically accelerated reaction kinetics observed in microdroplets [19].

The model incorporates three key concepts:

Partial Solvation: Interfacial species experience incomplete solvation, destabilizing reagents more than transition states and thereby increasing reaction rate constants [19].

Strong Electric Fields: Microdroplet interfaces containing water maintain intrinsic electric fields of ~10⁹ V/m, as established through computational and experimental measurements [19].

Reactive Species Generation: Field ionization of water creates primary reactive species (H₂O⁺˙) that initiate cascades of chemical transformations [19].

Field Ionization Step

The strong electric field at microdroplet interfaces enables field ionization of water molecules through electron tunneling, analogous to Beckey's field ionization technique. This process generates water radical cations (H₂O⁺˙) as the primary oxidizing agents and solvated electrons (e⁻(aq)) as the primary reducing agents [19].

Field ionization occurs with effectively zero activation energy due to the quantum mechanical nature of electron tunneling. The probability of tunneling depends on both molecular orientation and electric field strength across the interfacial water layer. Notably, electron tunneling exhibits lower effective energy barriers in aqueous environments compared to vacuum, enhancing its probability at microdroplet interfaces [19].

Chemical Ionization Step

Following field ionization, the initially generated reactive species undergo secondary reactions in a chemical ionization process. The water radical cation reacts with neutral water molecules to form a dimeric complex that dissociates into hydronium ion and hydroxyl radical:

Equation 1: Self-Chemical Ionization H₂O⁺˙ + H₂O → H₂O⁺˙(H₂O) → H₃O⁺ + HO˙ [19]

This "self-chemical ionization" represents a crucial step in generating the reactive intermediates responsible for diverse microdroplet transformations. The hydroxyl radical and hydronium ion subsequently participate in acid-base and redox chemistry, while the solvated electron serves as a potent reducing agent [19].

Table 1: Reactive Species in Microdroplet Chemistry

| Species | Formation Process | Chemical Role | Representative Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| H₂O⁺˙ | Primary field ionization | Strong oxidizing agent | Electron transfer reactions |

| e⁻(aq) | Electron from FI | Strong reducing agent | Reduction of organic compounds |

| HO˙ | Secondary CI from H₂O⁺˙ | Oxidizing agent | Hydrogen abstraction, addition |

| H₃O⁺ | Secondary CI from H₂O⁺˙ | Brønsted acid | Acid-catalyzed reactions |

Mechanistic Integration in ESI Process

The integration of FI and CI mechanisms provides a comprehensive explanation for microdroplet phenomena. This unified model accounts for:

- Ionization for MS detection through protonation and redox processes

- Reaction acceleration via highly reactive radical and ionic intermediates

- Simultaneous acid-base and redox chemistry within single droplet populations

- Generation of observed products including hydrogen peroxide through secondary reactions [19]

The mechanism operates specifically at the air-water interface of microdroplets where both strong electric fields and partial solvation conditions prevail, explaining the interfacial nature of reaction acceleration.

Experimental Evidence and Validation

Key Experimental Findings

Multiple lines of evidence support the proposed FI/CI mechanism in microdroplets:

Electric field measurements: Experimental determinations confirm field strengths sufficient for field ionization (~10⁹ V/m) at nebulized microdroplet interfaces [19].

Water radical cation detection: Mass spectrometric identification of H₂O⁺˙ and its oligomers (m/z 36) provides direct evidence for the primary FI step [19].

Size-dependent effects: Correlation between droplet size (and thus surface-to-volume ratio) and reaction acceleration confirms the interfacial nature of the process [19].

Product analysis: Reaction products consistent with radical and acid-base mechanisms support the proposed reactive intermediates [19].

Experimental Approaches for Microdroplet Analysis

Researchers have employed diverse methodological approaches to investigate microdroplet chemistry:

Table 2: Experimental Methods in Microdroplet Research

| Method | Key Features | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESI-MS | Online reaction monitoring | Real-time analysis of reaction kinetics and products | [18] |

| Levitated Droplets | Single droplet manipulation | Controlled study of interfacial phenomena | [19] |

| Spray Collection | Product isolation | Milligram-scale synthesis for NMR characterization | [19] |

| Computational Modeling | Theoretical simulation | Electric field calculation and reaction pathway analysis | [19] |

| Imprint DESI-MSI | Spatial visualization | Herbicide penetration in plant tissues | [20] |

Quantitative Data on Reaction Acceleration

Microdroplet environments enhance reaction rates by several orders of magnitude compared to bulk phase conditions. The following table summarizes documented acceleration factors for various reaction types:

Table 3: Quantitative Acceleration Factors in Microdroplet Reactions

| Reaction Type | Acceleration Factor | Key Characteristics | Required Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claisen-Schmidt | Up to 10⁶ | Catalyst-free condensation | Aqueous microdroplets, ambient temperature | [19] |

| Pomeranz-Fritsch | Up to 10⁶ | Cyclization reaction | Interfacial environment, strong electric field | [19] |

| Redox Reactions | 10³-10⁵ | Diverse substrates | Water-containing droplets, partial solvation | [19] |

| Acid-Base Catalyzed | 10⁴-10⁶ | No external acid/base | H₃O⁺/HO˙ generation at interface | [19] |

| Hydrolysis | 10³-10⁵ | Spontaneous cleavage | Interfacial water activation | [19] |

Methodologies for Microdroplet Experiments

Standard ESI-MS Protocol for Reaction Monitoring

Principle: Electrospray ionization generates microdroplets while simultaneously serving as an inlet for mass spectrometric analysis [19].

Procedure:

- Prepare reagent solution in water-containing solvent (typically 1-100 µM concentration)

- Load solution into ESI source with flow rates of 0.5-5 µL/min

- Apply high voltage (3-6 kV) to create charged microdroplets

- Monitor reaction products in real-time using mass analyzer

- Optimize desolvation temperature and gas flows to control droplet lifetime

Key Parameters:

- Voltage: 3-6 kV

- Flow rate: 0.5-5 µL/min

- Solvent: Water-containing (often 1:1 to 4:1 organic:water)

- Capillary temperature: 150-300°C

Applications: Rapid reaction screening, mechanistic studies, catalyst-free synthesis [19].

Spray Collection for Product Isolation

Principle: Microdroplets are generated through spraying and collected for offline analysis, enabling product isolation in milligram quantities [19].

Procedure:

- Prepare reagent solution (mM concentration)

- Nebulize or electrospray solution toward collector surface

- Control droplet flight distance to manipulate reaction time

- Collect products in solvent or on solid surface

- Characterize using NMR, LC-MS, or other analytical techniques

Key Parameters:

- Nozzle-to-collector distance: 1-10 cm

- Solution concentration: 1-100 mM

- Collection solvent: Compatible with product solubility

- Gas pressure: 20-120 psi (for nebulization)

Applications: Small-scale synthesis, product characterization, reference standard preparation [19].

Imprint DESI-MSI for Spatial Analysis

Principle: Imprint desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging enables visualization of spatial distributions in complex samples [20].

Procedure:

- Treat biological sample (plant/animal tissue) with analyte of interest

- Section sample and press against oil-absorbing film for 10 seconds

- Analyze imprint using DESI-MSI with raster scanning

- Acquire mass spectra at each pixel (150 µm resolution)

- Reconstruct spatial distribution using custom software

Key Parameters:

- Spray voltage: -6 kV (negative mode)

- Solvent: 8:2 acetonitrile:water

- Flow rate: 1.5 µL/min

- Pixel size: 150 µm

- Gas pressure: 120 psi

Applications: Herbicide penetration studies, metabolite localization, drug distribution analysis [20].

Visualizing Microdroplet Mechanisms and Workflows

FI/CI Mechanism in Microdroplets

Microdroplet FI/CI Mechanism Diagram: This diagram illustrates the sequential process of field ionization followed by chemical ionization that generates reactive species in charged microdroplets.

Microdroplet Experiment Workflow

Microdroplet Experiment Workflow: This workflow outlines the typical steps in microdroplet experiments, from sample preparation to final applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Microdroplet Experiments

| Item | Specifications | Function | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Voltage Power Supply | 3-6 kV capability | Electrospray droplet generation | Standard ESI instrumentation [19] |

| Microsyringe Pump | 0.5-5 µL/min flow range | Precise solution delivery | Commercial HPLC systems [19] |

| Water-Soluble Reagents | High purity (>95%) | Reaction substrates | Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific [19] |

| Mass Spectrometer | High resolution (>30,000) | Reaction monitoring and product identification | Orbitrap platforms [20] |

| Oil-Absorbing Film | Clean & Clear or equivalent | Imprint substrate for DESI-MSI | Johnson & Johnson [20] |

| Nebulization Gas | High-purity N₂ (99.999%) | Droplet generation without ESI | Standard laboratory gas supply [19] |

| Alkali Metal Salts | CsI for polymer stability | Adduct formation for MS analysis | Chemical suppliers [21] |

Implications and Applications

Implications for ESI Mechanism Understanding

The FI/CI model revolutionizes understanding of fundamental ESI processes by:

- Providing a unified mechanism for both ionization and reaction acceleration

- Explaining the essential role of water in ESI processes

- Accounting for the generation of protonated molecules without external acid sources

- Revealing the connection between electric fields and reactive intermediate generation [19]

This enhanced understanding enables more intentional application of ESI not just as an analytical tool but as a synthetic platform.

Practical Applications Across Industries

Drug Discovery: Microdroplet acceleration enables rapid screening of reaction pathways and metabolite identification, significantly reducing development timelines. The ability to perform catalyst-free reactions under ambient conditions provides sustainable synthetic routes for pharmaceutical intermediates [18] [19].

Green Synthesis: The elimination of requirement for toxic catalysts and harsh conditions aligns with green chemistry principles. Microdroplet approaches reduce solvent consumption and energy requirements while maintaining high reaction efficiency [18].

Prebiotic Chemistry: The demonstration that complex organic transformations can occur spontaneously in aqueous microdroplets under ambient conditions has implications for understanding chemical evolution and the origin of life [18] [19].

Analytical Sciences: Improved understanding of ESI mechanisms enhances interpretation of mass spectrometric data, particularly for labile compounds and reaction intermediates. The application of imprint DESI-MSI extends to food safety monitoring and environmental toxicology [20].

The integration of field ionization and chemical ionization mechanisms provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the unique chemistry occurring in charged microdroplets. This model explains both the remarkable acceleration of diverse reactions and the ionization processes fundamental to ESI-MS. As research in this field advances, the deliberate exploitation of microdroplet environments promises to transform approaches to chemical synthesis, analysis, and understanding of fundamental chemical processes. The implications span from practical applications in pharmaceutical research to fundamental questions about chemical reactivity at interfaces.

ESI-MS in Action: Transformative Applications in Clinical and Pharmaceutical Laboratories

Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry (ESI-Tandem-MS or ESI-MS/MS) represents a cornerstone technological advancement in clinical chemistry, revolutionizing the screening and diagnosis of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (IEM). IEM constitute a group of phenotypically and genotypically heterogeneous metabolic disorders caused by gene mutations encoding metabolic pathway enzymes or receptors. Deficiency or changes in the activity of essential enzymes in intermediate metabolic pathways lead to the accumulation or deficiency of corresponding metabolites, manifesting in a wide range of diseases with clinical heterogeneity that complicates their diagnosis [22].

The application of ESI-MS/MS to newborn screening offers the potential of substantially altering the natural history of these diseases by reducing morbidity and mortality. This technology has transitioned screening from the outdated classical methods of "one test, one metabolite, and one disease" to a "single test, many metabolites, and many diseases" approach [22]. The ability to detect numerous metabolic disorders simultaneously with high sensitivity and specificity has established ESI-MS/MS as an ethical, safe, simple, and reliable screening test that is now a mandatory public health strategy in most developed countries [22].

Fundamental Principles of Electrospray Ionization

ESI Mechanism and Process

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that operates at atmospheric pressure and is particularly suitable for thermally labile and at least moderately polar organic analytes. The ESI process involves three fundamental stages:

Droplet Formation: A liquid sample is pumped through a narrow capillary needle maintained at high voltage (typically 3-5 kV), creating a fine aerosol of charged droplets.

Droplet Desolvation: The charged droplets shrink through solvent evaporation, increasing charge density until Coulombic repulsion overcomes surface tension.

Ion Emission: Gaseous ions are released via two possible mechanisms - the charged residue model (CRM) for larger molecules or the ion evaporation model (IEM) for smaller ions [23].

ESI typically yields ions with no unpaired electrons (even-electron ions), with the resulting [M + H]+ species referred to as protonated molecules. These ions possess low internal energy, resulting in minimal fragmentation in single-stage MS experiments, making ESI ideal for preserving intact molecular information for sensitive and fragile compounds [23].

ESI in Positive and Negative Ion Modes

The versatility of ESI allows operation in both positive (ES+) and negative (ES-) ion modes, with mode selection dependent on the proton affinity of the target analytes:

ES+ Mode: Optimal for compounds with basic characteristics, easily ionized via adduct formation with proton(s). Common adducts include [M + H]+, [M + Na]+, and [M + NH4]+.

ES- Mode: Suitable for molecules possessing acidic functional groups and lacking basic ones, typically forming [M - H]- ions [23].

The selection of ionization mode significantly impacts detection sensitivity and should be optimized based on the chemical properties of target metabolites. For IEM screening, positive ion mode is typically employed for amino acids and acylcarnitines, though some applications may benefit from negative mode detection.

ESI-MS/MS Methodology for IEM Screening

Analytical Workflow

The ESI-MS/MS screening process for IEM follows a standardized workflow that ensures comprehensive metabolite profiling with high reproducibility:

Sample Preparation: Heel blood from newborns (3 days after birth) is collected and dripped onto filter paper (S&S 903), dried naturally at room temperature, and extracted for analysis [24].

Chromatographic Separation: While Flow Injection Analysis (FIA) can be used for high-throughput screening, Liquid Chromatography (LC) provides superior separation of isomeric and isobaric compounds. Typical LC conditions utilize C18 columns with mobile phases consisting of methanol/water mixtures, often with 0.01% formic acid to enhance protonation [25].

Mass Spectrometric Analysis: The instrument setup for IEM screening typically includes:

- Ion Source: ESI with interface voltage of 4.5 kV

- Nebulizer Gas Flow: 3 L/min

- Drying Gas Flow: 15 L/min

- Desolvation Line Temperature: 250°C

- Heat Block Temperature: 400°C [25]

Data Analysis: Quantitative analysis of amino acids and acylcarnitines using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions specific to each metabolite.

Key Metabolites and Disease Associations

ESI-MS/MS enables simultaneous monitoring of numerous metabolites that serve as biomarkers for various IEM categories. The table below summarizes the primary metabolite classes and their associated disorder groups:

Table 1: Key Metabolite Classes and Associated IEM Categories

| Metabolite Class | Representative Analytes | Associated Disorder Categories | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Leucine, Methionine | Aminoacidemias (e.g., PKU, MSUD, HCY) | Accumulation of toxic amino acids causes neurological damage |

| Acylcarnitines | C0, C2, C3, C4, C5, C8, C16 | Organic Acidemias, Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders | Indicators of blocked metabolic pathways and energy deficiency |

| Succinylacetone | - | Tyrosinemia Type I | Liver and kidney dysfunction |

The sensitivity and specificity of this method can reach 99% and 99.995%, respectively, for most amino acid disorders, organic acidemias, and fatty acid oxidation defects [22].

Experimental Protocols for IEM Screening

Standardized Newborn Screening Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Filter paper cards (S&S 903)

- Internal standards for amino acids and acylcarnitines

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Formic acid (analytical grade)

- Butanol/HCl derivatization reagent (for some methods)

Procedure:

- Collect heel-prick blood spots on filter paper 24-48 hours after birth

- Dry blood spots at ambient temperature for a minimum of 3 hours

- Punch 3.2 mm discs from dried blood spots into microtiter plates

- Add internal standard solution containing deuterated amino acids and acylcarnitines

- Extract analytes with 100 μL methanol with shaking for 30 minutes

- Derivatize butyl esters (for some methods) or analyze underivatized

- Analyze using LC-ESI-MS/MS with a run time of approximately 2 minutes per sample

- Quantify metabolites against calibration curves using stable isotope internal standards

Quality Control:

- Include quality control samples with each batch (low, medium, high concentrations)

- Monitor internal standard responses for signal suppression/enhancement

- Participate in external proficiency testing programs

Two-Tier Screening Approach

To minimize false positives and improve specificity, a two-tier screening system is often implemented:

- First-Tier Screening: Initial FIA-MS/MS analysis for high-throughput screening

- Second-Tier Testing: Confirmatory LC-MS/MS analysis for presumptive positive samples, increasing test specificity and dramatically reducing false positives [22]

This approach is particularly valuable for disorders with low specificity biomarkers, where second-tier tests can utilize different chromatographic separations or additional analyte markers to improve positive predictive value.

Table 2: Incidence Rates of Common IEM Detected by ESI-MS/MS in Southern China (n=111,986 newborns)

| Disorder | Incidence Rate | Primary Metabolic Markers | Confirmatory Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Carnitine Deficiency | 1:9,332 | Decreased free carnitine (C0) | SLC22A5 gene sequencing |

| Phenylketonuria (PKU) | 1:18,664 | Elevated phenylalanine | PAH gene analysis |

| Isovaleric Acidemia | 1:37,329 | Elevated C5 acylcarnitine | IVD gene sequencing |

| Citrullinemia Type II | 1:111,986 | Elevated citrulline | SLC25A13 mutation analysis |

| Methylmalonic Acidemia | 1:37,329 | Elevated C3 acylcarnitine | MMUT, MMAA, MMAB genes |

| Overall IEM Incidence | 1:3,733 | Multiple markers | Gene sequencing |

Data adapted from a screening study of 111,986 newborns in Southern China [24].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Ionization Techniques

ESI versus APCI for IEM Applications

While ESI is the predominant ionization source for IEM screening, Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) represents an alternative approach with distinct characteristics:

Table 3: Comparison of ESI and APCI Characteristics for Clinical Applications

| Parameter | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) |

|---|---|---|

| Ionization Mechanism | Charge transfer in liquid phase | Gas-phase chemical ionization |

| Analyte Polarity | Moderate to high polarity | Low to moderate polarity |

| Molecular Mass Range | Up to 100,000+ Da | < 1,500 Da |

| Matrix Effects | More susceptible to suppression | Less susceptible to matrix effects |

| Flow Rate Compatibility | Optimal at low flow rates (<0.2 mL/min) | Compatible with higher flow rates (1.0 mL/min) |

| Adduct Formation | Pronounced ([M+H]+, [M+Na]+, etc.) | Primarily [M+H]+ or [M-H]- |

| Fragmentation Pattern | Even-electron ions, heterolytic cleavage | Can generate odd-electron ions |

APCI appears to be slightly less liable to matrix effects than ESI, as demonstrated in studies comparing the ionization sources for pharmaceutical compounds [25]. However, ESI generally provides superior sensitivity for polar metabolites central to IEM screening.

Advancing Ionization Technologies

Beyond conventional ESI, several advanced ionization techniques have emerged with potential applications in specialized IEM testing:

Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI):

- Ambient ionization technique requiring minimal sample preparation

- Utilizes charged solvent spray to desorb and ionize analytes directly from surfaces

- Enables spatial mapping of metabolites in tissue samples [26]

Nanospray Desorption Electrospray Ionization (nanoDESI):

- Improved version achieving spatial resolution of ~10 μm

- Enhanced sensitivity through better ion transfer efficiency

- Suitable for gentle surface lipidomic mapping [26]

These ambient ionization methods expand the application of MS-based metabolic profiling beyond dried blood spots to tissue sections and other complex samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of ESI-MS/MS for IEM screening requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for metabolic profiling:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ESI-MS/MS IEM Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Paper Cards | Blood sample collection and storage | S&S 903 specification | Ensure uniform blood saturation and drying |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Quantitative calibration | Isotope-labeled amino acids and acylcarnitines | Correct for matrix effects and ionization efficiency |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Protein precipitation and extraction | LC-MS grade, low UV absorbance | Minimize background interference in MS analysis |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase additive | ≥99% purity, LC-MS compatible | Enhances protonation in positive ion mode (0.01-0.1%) |

| Acylcarnitine Standards | Calibration and quality control | Certified reference materials | Multi-point calibration for quantitative accuracy |

| Amino Acid Standards | Calibration and quality control | Certified reference materials | Cover essential amino acids relevant to IEM |

Data Interpretation and Clinical Correlation

Diagnostic Algorithms

Interpretation of ESI-MS/MS data for IEM screening follows established algorithms that integrate multiple metabolite ratios and absolute concentrations:

Primary Marker Elevation: Identify significantly elevated primary biomarkers (e.g., phenylalanine for PKU)

Ratio Analysis: Calculate diagnostically relevant ratios (e.g., phenylalanine/tyrosine for PKU confirmation)

Pattern Recognition: Identify characteristic acylcarnitine profiles (e.g., elevated C0 for carnitine uptake defect)

Dynamic Monitoring: Track changes in metabolite levels in response to treatment

The integration of computational tools and bioinformatics pipelines has significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of data interpretation in large-scale screening programs.

Integration with Genetic Confirmation

ESI-MS/MS serves as a biochemical screening tool that is increasingly integrated with genetic confirmation:

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is now included in confirmatory testing in many countries. Genomic DNA isolated from dried blood spots can be used for NGS, providing reliable sequencing results as a secondary diagnostic test for NBS [22].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of ESI-MS/MS applications in IEM screening continues to evolve with several emerging trends:

Expanded Disorder Panels: Continuous addition of new disorders to screening panels as biomarkers are validated

Second-Tier Molecular Testing: Integration of genetic testing directly into the screening algorithm

Computational Advancements: Improved bioinformatics tools for data interpretation and variant prioritization

International Standardization: Harmonization of cutoff values and analytical protocols across screening programs

Novel Biomarker Discovery: Application of untargeted metabolomics to identify new IEM biomarkers

According to bibliometric analysis of the field, the most relevant current research directions include "selective screening for IEM," "new treatments for IEM," "new disorders considered for MS/MS testing," "ethical issues associated with newborn screening," "new technologies that may be used for newborn screening," and "use of a combination of MS/MS and gene sequencing" [22].

The reproducibility and automation of metabolome annotation are being enhanced through workflows like MAW (Metabolome Annotation Workflow), which combines MS2 data pre-processing, spectral and compound database matching with computational classification, and in silico annotation [27]. Such computational advances are crucial for handling the increasing complexity of metabolomics data in IEM screening.

ESI-Tandem-MS has fundamentally transformed the landscape of IEM screening, enabling early detection of metabolic disorders before symptom onset and significantly improving clinical outcomes through timely intervention. The technology's unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capacity have established it as the gold standard in newborn screening programs worldwide.

Ongoing advancements in ionization techniques, computational analytics, and integration with genomic technologies promise to further enhance the scope and accuracy of IEM detection. As the field progresses, ESI-MS/MS will continue to play a pivotal role in advancing preventive medicine and reducing the global burden of inherited metabolic disorders through early intervention and personalized treatment approaches.

The structural elucidation of hemoglobin variants represents a critical endeavor in clinical proteomics, essential for diagnosing hemoglobinopathies—among the most common inherited human disorders globally [28]. Over 1,000 hemoglobin variants have been characterized, with approximately 150 causing clinically significant conditions such as sickle cell anemia, hemolytic anemia, and thalassemias [28]. The precision of variant identification directly impacts medical care, prognosis, and genetic counseling outcomes. Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Mass Spectrometry has revolutionized this field by enabling rapid, accurate analysis of hemoglobin proteins with minimal sample requirements. This technical guide explores ESI-based methodologies within the broader context of ionization mechanism research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with advanced protocols for characterizing variant hemoglobins. The exceptional capability of ESI to generate multiply-charged ions from large biomolecules like hemoglobin (approximately 64.5 kDa) has transformed mass spectrometry from merely an analytical tool into a comprehensive platform for both structural analysis and accelerated chemical synthesis [18].

Electrospray Ionization Fundamentals and Mechanisms

Electrospray Ionization operates through a sophisticated mechanism that converts solution-phase proteins into gas-phase ions amenable to mass analysis. When applied to hemoglobin analysis, the ESI process begins with introducing a hemoglobin solution through a capillary maintained at high voltage (typically 3-4 kV). This creates a Taylor cone that emits a fine mist of charged droplets toward the mass spectrometer inlet [29]. As these droplets travel through the ESI source, solvent evaporation occurs while droplet charge density increases. Through processes termed field ionization and chemical ionization, the droplets eventually release protonated hemoglobin molecules into the gas phase [18].

Recent research on charged microdroplets has revealed that ESI facilitates remarkably accelerated chemical reactions—up to 10^6 times faster than analogous bulk reactions—which has profound implications for both analytical applications and synthetic chemistry [18]. This phenomenon stems from unique ionization mechanisms within microdroplets, including extremely high electric fields at the droplet surface that promote efficient ionization. For hemoglobin analysis, this translates to enhanced sensitivity and the ability to detect low-abundance variants that might escape conventional methodologies.

A key advantage of ESI for hemoglobin analysis is the generation of multiply-charged ions [M+nH]ⁿ⁺, which effectively reduces the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of large proteins like hemoglobin, making them compatible with most mass analyzers. The number of charges acquired depends on solvent composition, source parameters, and the number of accessible basic sites on the protein surface. This multi-charging phenomenon enables precise molecular weight determination of intact globin chains and facilitates top-down sequencing approaches through tandem mass spectrometry.

Analytical Approaches for Hemoglobin Variant Characterization

Mass Spectrometry Platforms and Methodologies

Multiple mass spectrometry platforms have been successfully employed for hemoglobin variant analysis, each offering distinct advantages:

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) provides excellent capabilities for molecular weight determination of intact globin chains. The methodology requires minimal sample preparation (as little as 2-10 μL of whole blood) with no need for pre-separation of red cells or globin chains [30]. Aged and hemolyzed blood samples can also be analyzed effectively. ESI-MS typically achieves positive identification of 95% of variants, with a sample preparation and analysis time of approximately one hour [30]. This approach has successfully identified 99 different abnormalities comprising 36 alpha-chain variants, 59 beta-chain variants, and 4 hybrid hemoglobins, including novel variants [30].

Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HR-MS) combines separation power with mass accuracy to resolve challenging variants. Using a C4 reversed-phase column, this method can separate pairs of normal and variant Hb subunits with mass differences smaller than 1 Da [31]. The high resolution enables explicit observation of analytes in deconvoluted MS1 mass spectra and facilitates top-down analysis for matching amino acid sequences to correct Hb variant subunits [31].

MALDI-ISD Mass Spectrometry utilizes matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization with in-source decay for top-down sequencing. With appropriate matrix selection (super DHB or 1,5-diaminonaphthalene), this technique provides extensive fragmentation generating c-, (z+2)-, and y-ion series [28]. On the first 70 amino acids from the N- and C-termini of alpha and beta chains can be covered in a single experiment, enabling characterization of variants like Hb Westmead (α122 His→Gln) [28].

Electrospray Ionization-Electron Transfer Dissociation Mass Spectrometry (ESI-ETD-MS) excels at fragmenting multiply-charged ions (3+ or higher) to generate sequence information. This approach is particularly valuable when variant peptide ions experience interference from other ions at the same m/z value [29]. ETD spectra are often less complex and easier to interpret than collision-induced dissociation spectra of the same charge state [29].

Comparative Performance of Analytical Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Methods for Hemoglobin Variant Analysis

| Method | Key Features | Analysis Time | Mass Accuracy | Sequence Coverage | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESI-MS | Minimal sample prep; intact mass measurement | ~1-2 hours [30] | Moderate | N/A | Rapid screening; molecular weight profiling [30] |

| LC-HR-MS | High resolution; separation of similar mass variants | Moderate-long | High (<1 Da difference) [31] | Limited without fragmentation | Distinguishing variants with mass differences <1 Da [31] |