Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) and Simplex Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) and Sequential Simplex methods for process optimization in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research.

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) and Simplex Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) and Sequential Simplex methods for process optimization in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of these statistical optimization techniques, detailed methodological implementations, troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and comparative validation against traditional experimental designs. By synthesizing historical context with current applications and emerging trends, this guide serves as both an educational resource and practical manual for implementing continuous improvement methodologies that maintain process control while systematically enhancing critical quality attributes, yield, and efficiency in manufacturing and research settings.

Evolutionary Operation Fundamentals: History, Principles and Pharmaceutical Relevance

The concept of Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) was formally introduced by George E.P. Box in 1957 as a systematic method for continuous process improvement during routine production [1] [2]. Box, a renowned statistician whose career spanned development at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) to academia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, envisioned EVOP as a practical methodology that could be implemented by process operatives themselves to reap enormous rewards through daily use of simple statistical design and analysis [2] [3]. His foundational work established EVOP as a catalyst for knowledge gathering, embodying his famous philosophy that "all models are wrong but some are useful" [3].

This whitepaper examines the historical trajectory of EVOP from its original formulation to its modern implementations, particularly within pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. The core thesis underpinning this analysis is that EVOP and related simplex methods represent an evolutionary approach to process optimization that stands in contrast to traditional one-shot experimentation, instead emphasizing iterative learning, adaptation to process drift, and integration of subject matter knowledge through sequential investigation [4] [5]. This philosophical framework has proven particularly valuable in contexts where processes are subject to biological variability, material changes, and environmental fluctuations that cause optimal conditions to drift over time [4] [2].

Foundational Principles and Methodologies

Core Philosophy of Evolutionary Operation

EVOP operates on the principle of making small, systematic perturbations to a process during normal production operations, collecting sufficient data to detect meaningful effects despite natural variation, and then using this information to gradually steer the process toward more optimal conditions [4] [2]. This approach differs fundamentally from traditional Response Surface Methodology (RSM) in several key aspects:

- Minimal Disruption: EVOP employs small perturbations that keep the process within acceptable specification limits, whereas RSM typically requires larger perturbations that might produce unacceptable output [4].

- Online Implementation: EVOP is designed to be applied directly to full-scale production processes, unlike RSM which often requires pilot-scale experimentation [4].

- Adaptive Capability: EVOP can track drifting process optima caused by batch-to-batch variation, environmental conditions, and machine wear [4].

The methodology aligns with what Box described as the essential iterative nature of scientific progress - a continuous cycle of developing tentative models, collecting data to explore them, and then revising the models based on findings [5]. This mirrors the Shewhart-Deming Cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act) that drives continuous improvement in quality systems [5].

The Original EVOP Methodology

The original EVOP procedure developed by Box utilizes simple factorial designs as building blocks for sequential experimentation [5] [2]. A typical EVOP implementation involves:

- Phase Development: Experiments are conducted through a series of phases and cycles [1].

- Systematic Changes: Small, planned changes are made to process variables during routine production [1].

- Statistical Testing: Effects are tested for statistical significance against experimental error [1].

- Condition Resetting: When a factor proves significant, operating conditions are reset and the experiment continues [1].

This process continues iteratively until no further improvement is achieved, establishing the "evolutionary" concept through variation and selection of favorable variants [1]. Box emphasized that this approach enables "never-ending improvement" because unlike fixed-model optimization that hits diminishing returns, the evolving model in EVOP allows for expanding returns as new knowledge emerges [5].

Simplex Method as an Alternative Approach

Shortly after Box introduced EVOP, Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth introduced the Simplex method in the early 1960s as an alternative optimization technique [4]. Unlike EVOP's factorial design foundation, the basic Simplex method is a geometric approach that operates by constructing a simplex (a generalized triangle) in the factor space and iteratively moving this simplex toward the optimum by reflecting it away from the point with the worst response [4] [1].

The key characteristics of the basic Simplex method include:

- Minimal Experiments: Only a single new measurement is added in each iteration [4].

- Geometric Progression: The simplex moves through the experimental domain by reflecting the worst-performing point through the centroid of the remaining points [1].

- Computational Simplicity: Calculations are straightforward enough to be performed manually [4].

It is crucial to distinguish this basic Simplex method for process optimization from Dantzig's simplex algorithm for linear programming, though they share a name [6]. The latter was developed by George Dantzig in 1947 for solving linear programming problems and operates on different mathematical principles [7] [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Original EVOP and Basic Simplex Method Characteristics

| Characteristic | Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) | Basic Simplex Method |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design | Factorial designs (full or fractional) | Sequential simplex movements |

| Measurements per Step | Multiple measurements in each phase | Single new measurement per iteration |

| Computational Complexity | Simplified calculations for manual use | Simple geometric calculations |

| Noise Resistance | Better signal detection through repeated measurements | Prone to noise due to single measurements |

| Implementation Pace | Slower progression due to comprehensive phases | Rapid movement through experimental domain |

| Typical Applications | Full-scale production processes | Lab-scale studies, chromatography optimization |

Evolution and Refinements in Methodology

The Nelder-Mead Adaptive Simplex

In 1965, Nelder and Mead published a significant refinement to the basic Simplex method that allowed the simplex to adapt in size and shape, not just position [4]. This "variable Simplex" procedure could expand in promising directions and contract in unfavorable ones, dramatically improving convergence speed for numerical optimization problems [4]. However, this adaptability came with limitations for real-life process optimization:

- Risk of Large Perturbations: The variable step size could lead to unacceptably large changes in process settings [4].

- Signal-to-Noise Issues: Excessively small steps might not provide sufficient signal relative to process noise [4].

- Nonconforming Product Risk: The method's exploratory nature could push the process outside acceptable operating boundaries [4].

Due to these limitations, the Nelder-Mead simplex found its primary application in numerical optimization and research settings rather than full-scale production environments [4].

Modern Computational Advances

Recent decades have seen significant theoretical advances in understanding optimization algorithms, particularly for the linear programming simplex method. In 2001, Spielman and Teng demonstrated that introducing randomness could prevent the worst-case exponential time complexity that had long been a theoretical concern for the simplex method [7]. Their work showed that with tiny random perturbations, the running time could be bounded by a polynomial function of the number of constraints [7].

More recently, in 2025, Huiberts and Bach built upon this foundation to establish even tighter bounds on simplex method performance, providing stronger mathematical justification for its observed efficiency in practice [7]. This ongoing theoretical work has helped solidify the foundation for optimization methods used in various computational applications, though its direct impact on EVOP implementations in industry remains limited.

Implementation in Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Sectors

Historical Applications and Barriers

EVOP was initially met with limited adoption in regulated industries like pharmaceuticals due to several factors:

- Management Resistance: Companies hesitant to allow experimentation on validated processes [2].

- Regulatory Concerns: Perception that changes might jeopardize validated status or require extensive documentation [2].

- Operator Training: Need for statistical training at the operator level for proper implementation [2].

Despite these barriers, successful applications emerged in biotechnology and biological processes where inherent variability made adaptive optimization particularly valuable [4]. The dominance of biological applications is unsurprising given that "biological variability is inevitable and is often substantial" due to different origins of raw materials and climate impacts [4].

Modern Revival and Current Applications

Recent years have witnessed renewed interest in EVOP and simplex methodologies driven by several industry developments:

- Quality by Design (QbD) Initiatives: Regulatory encouragement for enhanced process understanding [2].

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Enhanced sensor technologies enabling real-time data collection [2].

- Continuous Manufacturing: Shift from batch to continuous processing requiring adaptive control [2].

These developments, coupled with the ICH guidelines (Q8, Q9, Q10), have created a more favorable environment for EVOP implementation in pharmaceutical manufacturing [2]. The method is particularly suited for situations where a process has 2-3 key variables, performance changes over time, and calculations need to be minimized [1].

Table 2: Evolution of EVOP and Simplex Applications Across Industries

| Time Period | Dominant Applications | Key Developments |

|---|---|---|

| 1957-1970s | Chemical industry, early biotechnology | Box's original EVOP, Basic Simplex |

| 1980s-1990s | Chromatography, sensory testing, paper industry | Spread of basic Simplex, Early pharmaceutical applications |

| 2000-2010 | Biotechnology, lab-scale studies | Renewed research interest, Comparison studies |

| 2010-Present | Pharmaceutical manufacturing, continuous processes | Integration with QbD, PAT, and regulatory initiatives |

Practical Implementation Protocols

EVOP Experimental Workflow

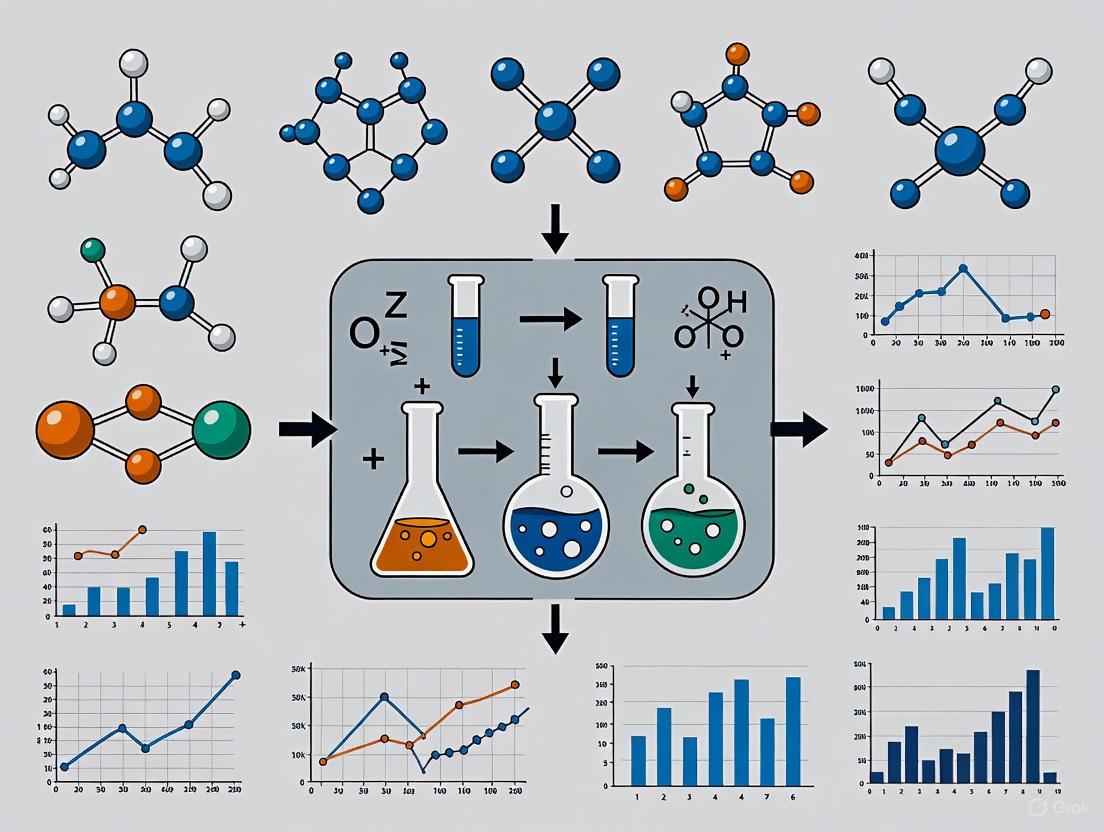

The following diagram illustrates the standard EVOP implementation workflow based on Box's original methodology:

EVOP Workflow

Basic Simplex Optimization Procedure

For comparison, the following diagram illustrates the basic Simplex method workflow for process optimization:

Simplex Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol: EVOP for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

A typical EVOP implementation for a pharmaceutical process involves the following detailed methodology:

Pre-Experimental Phase

- Process Characterization: Identify critical quality attributes (CQAs) and key process parameters (KPPs) [1] [2].

- Baseline Establishment: Document current operating conditions and performance metrics [1].

- Incremental Change Planning: Define small, non-disruptive changes to process variables (typically 2-3 variables) [1].

Experimental Design Phase

Execution Phase

- Normal Production: Conduct experiments during routine manufacturing operations [2].

- Data Collection: Measure all relevant quality attributes and performance metrics [1].

- Multiple Cycles: Repeat the experimental pattern through several production cycles to accumulate sufficient data for statistical significance [4].

Analysis and Decision Phase

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate main effects and interactions using simplified analysis methods [1].

- Significance Testing: Compare effects to experimental error using basic statistical tests [1].

- Process Adjustment: Implement meaningful changes to operating conditions based on significant effects [1].

Iteration Phase

Example: EVOP Implementation for Tablet Coating Process

A practical example from the pharmaceutical industry involves optimizing a tablet coating process to reduce defects:

- Initial Conditions: Coating solution concentration: 15%, Spray rate: 200 mL/min, Inlet air temperature: 45°C [1].

- Performance Characteristic: Reduce tablet defects from 8% to below 3% [1].

- Incremental Changes: ±1% concentration, ±10 mL/min spray rate, ±2°C temperature [1].

- Experimental Design: 2³ factorial design with center point (9 experimental conditions) [8].

- Implementation: Each condition run for one production batch with 10,000 tablets per batch [1].

- Analysis: After three complete cycles, analysis revealed spray rate and interaction between concentration and temperature as statistically significant [1].

- Optimized Conditions: Coating solution concentration: 16%, Spray rate: 190 mL/min, Inlet air temperature: 47°C [1].

- Result: Defect rate reduced to 2.5% while maintaining all quality specifications [1].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EVOP Studies

| Material/Resource | Function in EVOP Study | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Design Matrix | Defines experimental pattern and ensures balanced comparisons | Pre-printed forms for operators to follow during routine production |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Analyzes effects and determines significance | Simplified interfaces for plant personnel; automated calculations |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Enables real-time data collection on critical quality attributes | Must be validated and integrated with production control systems |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Ensures consistent implementation of experimental conditions | Include specific instructions for experimental modifications |

| Data Collection Forms | Records process parameters and quality measurements | Designed for ease of use by production operators |

| Control Charts | Monitors process stability during experimentation | Enables detection of special causes versus experimental effects |

Comparative Analysis and Method Selection

Performance Under Different Conditions

Research comparing EVOP and Simplex methods has identified specific strengths and limitations for each approach under different experimental conditions [4]:

- Dimensionality: EVOP becomes progressively less efficient as the number of factors increases beyond 3-4, while basic Simplex maintains reasonable performance in higher dimensions [4].

- Noise Sensitivity: EVOP's use of multiple measurements provides better noise resistance, whereas Simplex can struggle with noisy responses due to its reliance on single measurements [4].

- Convergence Speed: Simplex typically moves more rapidly toward the optimum in early stages, while EVOP provides more reliable direction with sufficient replication [4].

Guidelines for Method Selection

Based on comparative studies and application reports, the following guidelines emerge for method selection:

Choose EVOP when:

Choose Basic Simplex when:

Avoid Variable Simplex (Nelder-Mead) when:

The historical development from George Box's 1957 foundation to modern implementations reveals an ongoing evolution of EVOP and simplex methodologies. Current trends suggest several future directions:

- Integration with Machine Learning: Combining EVOP's sequential approach with adaptive machine learning algorithms for more intelligent optimization [7].

- Digital Twin Technology: Implementing EVOP on digital process representations before physical implementation [2].

- Automated Experimental Systems: Leveraging robotics and automation to accelerate EVOP cycles in laboratory settings [4].

- Regulatory Harmonization: Developing standardized approaches for implementing EVOP in regulated environments [2].

The core thesis of evolutionary operation remains valid: processes can be systematically and gradually improved through small, planned perturbations during normal operation. As Box envisioned, this approach represents a practical implementation of the scientific method in industrial settings, enabling continuous improvement through iterative learning and adaptation [5].

The future of EVOP and simplex methodologies appears promising, particularly as industries face increasing pressure for efficiency, flexibility, and quality in increasingly variable and complex manufacturing environments. The fundamental principles established by Box in 1957 continue to provide a robust foundation for these evolving applications, demonstrating the enduring value of his original insight that processes can "evolve" toward optimal operation through systematic, statistically-guided experimentation.

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) is a practical methodology for the continuous improvement of production processes, conceived by statistician George Box in the 1950s [9]. Its core philosophy is to replace the static operation of a process with a continuous, systematic scheme of slight, planned deviations in the control variables [9]. Unlike traditional, disruptive Design of Experiment (DOE) approaches that require significant resources and often halt production, EVOP is integrated directly into full-scale operations [9]. It allows process operators to generate actionable data and ideas for improvement while the process continues to produce satisfactory products, making the investigative routine a fundamental mode of plant operation [9] [1].

This methodology is particularly suited for environments like drug development and manufacturing, where process performance may change over time due to factors such as batch-to-batch variation in raw materials, environmental conditions, and equipment wear [4]. EVOP provides a structured framework to gently steer a process toward its optimum or to track a drifting optimum over time, all while minimizing the risk of generating non-conforming products [4].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

The Fundamental Tenets of EVOP

The EVOP philosophy is built upon several key principles that differentiate it from other optimization techniques:

- Small Perturbations: EVOP relies on introducing small, incremental changes to process variables. These changes are kept within a range that ensures the final product remains within specification limits, thereby preventing the generation of scrap or off-specification material during the experimentation itself [9] [1].

- Systematic Experimentation: Changes are not made randomly. Instead, they follow a simple experimental design (e.g., factorial designs), allowing for the structured collection of data and the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships [9] [4].

- Continuous and Integrated: EVOP is not a one-off project. It is designed as a continuous investigative routine that becomes embedded in the normal operation of a plant, fostering a culture of sustained, incremental improvement [9].

- Operator-Led Improvement: The methodology is intentionally kept simple enough for process operators to understand and implement, empowering those closest to the process to contribute directly to its optimization [9].

EVOP vs. Traditional Methods

EVOP addresses several limitations inherent in classical Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and offline DOE [4].

Table: Comparison of EVOP and Traditional RSM

| Feature | Traditional RSM/DOE | Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) |

|---|---|---|

| Scale of Changes | Large perturbations | Small, incremental changes |

| Production Impact | Often requires pilot-scale or halted production | Integrated into full-scale, running processes |

| Primary Application | Offline, lab-scale experimentation | Online, full-scale production processes |

| Risk of Non-conforming Output | Higher, due to large changes | Lower, as changes stay within acceptable limits |

| Cost & Resource Demand | High (time, money, special training) | Low, considered to come "for free" [9] |

| Optimum Tracking | Static snapshot; must be repeated for drift | Capable of tracking a drifting optimum over time [4] |

As outlined in the table, EVOP is uniquely positioned for application in full-scale manufacturing, including pharmaceutical production, where the cost of failure is high and the process is subject to temporal drift [4].

EVOP Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The implementation of EVOP can be structured around different design types, depending on the number of process variables being studied.

Single and Multi-Factor EVOP Designs

For a process with one key factor, the protocol is straightforward [9]:

- The current production level (X) is established as the center point.

- Two acceptable levels, (X-D) and (X+D), are defined within the specification limits.

- The process quality is evaluated at each level (X, X-D, X+D) to identify which produces the highest quality output.

- The center point is then moved to this new, optimal level, and the cycle repeats.

For more complex processes, a two-factor EVOP design is used. The current production level for two factors (X, Y) serves as the center point, and the quality of the output is evaluated at all different combinations of X and Y (e.g., (X-D, Y-D), (X+D, Y-D), (X-D, Y+D), (X+D, Y+D)) [9]. The combination that yields the highest quality becomes the new center point for the subsequent cycle of improvement [9]. This logic extends to three factors, following the same systematic pattern.

The Simplex-Based EVOP Method

An alternative to the factorial design is the Simplex-based EVOP method. This is a sequential heuristic that uses a geometric figure (a triangle for two factors, a tetrahedron for three) to navigate the experimental space [1]. The following diagram and protocol outline this workflow.

Diagram 1: Simplex EVOP Workflow

The detailed protocol for the Simplex method is as follows [1]:

- Define the Objective: Identify the process performance characteristic that needs improvement (e.g., reduction of scrap, increased yield).

- Identify Variables: Select the process variables (e.g., temperature, pressure) whose small changes are likely to lead to improvement. Record their current conditions.

- Plan Changes: Plan the small, incremental change steps for each variable (e.g., +5°C, +2 psi).

- Establish Initial Simplex: For 'n' variables, define an initial simplex with n+1 corners. For two variables, this is a triangle.

- Perform Runs: Execute one production run at each corner of the simplex and record the results for the performance characteristic.

- Identify Worst Result: Determine the corner with the least favorable outcome.

- Calculate and Run Reflection: Generate a new corner by reflecting the worst corner through the centroid of the opposite face. The formula for a new run value (reflection) for two variables is:

New Value = (Sum of coordinates from good corners) - (Coordinate of least favorable corner)Perform a run at this new condition. - Iterate: Form a new simplex by replacing the worst corner with the newly generated one. Repeat the process from step 6 until no further improvement is achieved or the target is met.

Example: Optimization in a Production Context

A study titled "A comparison of Evolutionary Operation and Simplex for process improvement" provides a modern simulation-based analysis of these methods [4]. The research compared EVOP and Simplex under varying conditions of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), perturbation size (factorstep dx), and dimensionality (number of factors, k).

Table: Key Experimental Settings from Comparative Study [4]

| Experimental Setting | Description | Impact on Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Controls the amount of random noise in the process response. | A lower SNR (e.g., <250) makes it harder for both methods to pinpoint the improvement direction due to noise overpowering the signal. |

| Perturbation Size (dx) | The size of the small changes made to each factor. | An appropriately chosen dx is critical. If too small, the signal is lost in the noise; if too large, it risks producing non-conforming products. |

| Dimensionality (k) | The number of factors being optimized. | Classical EVOP, with its factorial design, becomes prohibitively expensive in high dimensions (>3). Simplex is more efficient for low-dimensional problems. |

The study concluded that the Simplex method requires a lower number of measurements to reach the optimum region, making it efficient for low-dimensional problems. In contrast, EVOP, with its designed experiments, is more robust in noisy environments (low SNR) but becomes computationally heavy as the number of factors increases [4]. This foundational knowledge is critical for researchers selecting an appropriate optimization strategy for a given process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Elements for EVOP Implementation

Successfully deploying an EVOP program requires more than just a statistical plan. It involves a combination of statistical designs, process knowledge, and operational discipline. The following table details the key "research reagents" or essential components needed for a successful EVOP initiative.

Table: Essential Components for EVOP Implementation

| Component | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Factorial or Simplex Design | The statistical backbone. Provides a structured plan for making changes, ensuring data collected is meaningful and can reveal cause-and-effect relationships [9] [1]. |

| Pre-defined Operating Ranges | Safety parameters. Establish the maximum and minimum deviations for each variable to ensure all experimental runs stay within product specification limits [9]. |

| Process Operators | The human engine of EVOP. Operators run the experiments, record data, and are integral to building a culture of continuous improvement. The methodology must be simple enough for them to use [9]. |

| Data Recording System | A simple, robust system for tracking the input variable settings (e.g., temperature, pressure) and the corresponding output responses (e.g., yield, purity) for every run. |

| EVOP Committee/Team | A cross-functional group (e.g., process chemists, engineers, quality assurance) that reviews results, decides on the next set of conditions, and champions the program [4]. |

| Patience and Management Support | A non-technical but critical resource. Because improvements are small and incremental, long-term commitment is necessary to realize significant gains [4]. |

The core philosophy of EVOP—continuous process improvement through small, systematic changes—remains a powerful and relevant paradigm for industries demanding high quality and operational excellence, such as pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. By integrating a structured, investigative routine directly into production, EVOP enables a dynamic and responsive optimization strategy. It stands in contrast to static operation and disruptive large-scale experiments, offering a low-risk, low-cost pathway to peak performance.

Modern research continues to validate and refine these principles, comparing EVOP with methods like Simplex to provide clear guidance on their application in contemporary settings with multiple factors and varying noise levels [4]. As manufacturing becomes increasingly data-driven, the core EVOP philosophy of using operational data for continuous, incremental improvement is more valuable than ever.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing stands at a crossroads, facing unprecedented pressure to enhance efficiency while maintaining rigorous quality control. Against a backdrop of increasing pricing pressure, supply chain vulnerabilities, and the rise of complex biologics, the industry can no longer rely on traditional, static production models [10] [11]. The convergence of advanced technologies with established operational principles creates new opportunities for optimization. Within this context, Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) and related systematic methodologies provide a foundational framework for achieving controlled, continuous improvement without compromising product quality or regulatory compliance [12] [13]. This whitepaper explores how modern pharmaceutical manufacturers can harness these approaches, integrating them with Industry 4.0 technologies to build more agile, efficient, and resilient production systems.

The core challenge lies in balancing the drive for optimization with the non-negotiable requirement for control. Process optimization in pharmaceutical manufacturing refers to the systematic effort to improve production efficiency, yield, and consistency, while control ensures that every batch meets stringent predefined standards of quality, safety, and efficacy [11]. These two objectives are not antagonistic but synergistic; a well-controlled process provides the stable baseline necessary for meaningful optimization, and optimization efforts, in turn, can lead to more robust and better-understood processes [12]. The industry is shifting from a paradigm of "quality by testing" to "quality by design" (QbD), where quality is built into the process through understanding and control, making it inherently optimizable [11].

Foundational Principles: EVOP and Simplex Methods

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) is a structured methodology for process optimization that was developed to allow experimentation and improvement during full-scale production [13]. Its core principle is the introduction of small, deliberate variations in process variables during normal production runs. These changes are not large enough to produce non-conforming product, but are sufficiently significant to reveal the process's sensitivity to each variable and identify directions for improvement [12] [13]. Unlike traditional large-scale experiments that require interrupting production, EVOP is a continuous, embedded activity. It treats every production batch as an opportunity to learn more about the process, thereby gradually and safely guiding it toward a more optimal state [13].

The sequential simplex method is a specific EVOP technique particularly well-suited for optimizing systems with multiple, continuously variable factors [12]. It is an efficient, algorithm-driven strategy that does not require an initial detailed model of the process. Instead, it uses a logical algorithm to dictate a series of experimental runs. Based on the measured response (e.g., yield, purity) of each run, the algorithm determines the next set of factor levels to test, systematically moving the process towards an optimum. A key strength of this method is its ability to provide improved response after only a few experimental cycles, making it highly efficient for refining complex manufacturing processes [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Approaches in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

| Feature | Classical Approach | EVOP/Simplex Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Model the system, then optimize | Find the optimum, then model the region |

| Experiment Scale | Large, dedicated experiments | Small, iterative changes during production |

| Impact on Production | Often requires interruption | Minimal disruption; integrated into runs |

| Number of Experiments | Can be very large (e.g., 80+ for 6 factors) | Highly efficient; improved response in few cycles |

| Statistical Analysis | Complex, requires detailed analysis | Logically-driven; minimal analysis needed |

| Best Application | New process development | Continuous improvement of existing processes |

The relationship between EVOP and modern control strategies is logically sequential, as shown in the workflow below. Optimization initiatives are grounded in a foundation of process understanding and control, with improvements systematically evaluated and permanently integrated into the controlled state.

Core Advantages of a Controlled Optimization Strategy

Enhanced Product Quality and Consistency

A systematic approach to optimization, grounded in EVOP principles, directly enhances product quality and batch-to-batch consistency. By making small, deliberate changes and meticulously monitoring their effects on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), manufacturers develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between process parameters and product quality [11]. This aligns perfectly with the Quality by Design (QbD) framework advocated by regulatory bodies, where quality is built into the product through rigorous process understanding and control [11]. Technologies such as Process Analytical Technology (PAT) enable real-time in-process monitoring of parameters like temperature, pressure, and pH, allowing for immediate adjustments that maintain product within its quality specifications [14] [11]. This moves quality assurance from a reactive (testing after production) to a proactive (controlling during production) model, significantly reducing the risk of batch failure and product variability.

Increased Manufacturing Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness

Optimization directly targets and improves manufacturing efficiency, which is crucial in an era of mounting cost pressures. The adoption of continuous manufacturing is a prime example, which replaces traditional batch processing with a seamless flow from raw materials to finished product. This method has been shown to reduce production timelines and improve yield consistency, as demonstrated by Vertex Pharmaceuticals' implementation for a cystic fibrosis therapy [11]. Furthermore, EVOP's small-step methodology prevents costly over-corrections and minimizes the production of sub-standard material [12] [13]. Digital tools amplify these gains; AI and machine learning predict equipment maintenance needs and optimize yields, while digital twin technology allows for simulation-based optimization without disrupting live production [14] [15] [11]. These technologies collectively drive down the cost of goods while increasing throughput.

Regulatory Compliance and Risk Mitigation

A controlled optimization strategy inherently strengthens regulatory compliance. A well-documented EVOP program demonstrates to regulators a deep and proactive commitment to process understanding and control [12]. The data generated provides objective evidence for justifying process parameter ranges in regulatory submissions, facilitating smoother approvals [11]. From a risk perspective, this approach is superior. It systematically mitigates risks associated with process variability, supply chain disruptions, and quality deviations. By building resilience through a better-understood process and a more transparent supply chain, companies can better navigate the "next era of volatility," including geopolitical unrest and logistical challenges [10] [11]. A controlled, data-driven optimization process is the antithesis of unpredictable and potentially non-compliant ad-hoc changes.

Table 2: Quantitative Benefits of Optimization Technologies in Pharma Manufacturing

| Technology/Method | Key Efficiency Gain | Impact on Control & Quality |

|---|---|---|

| AI in R&D & Manufacturing | Saves ~$1B in development costs over 5 years (Top-10 Pharma) [15] | Improves prediction of maintenance and process anomalies [11] |

| Continuous Manufacturing | Reduces production timelines; improves yield consistency [11] | Integrates real-time quality monitoring (PAT) for consistent output [11] |

| Sequential Simplex EVOP | Improved response after only a few experiments [12] | Small changes prevent non-conforming product; builds process knowledge [12] |

| Real-Time In-Process Monitoring | Reduces batch failures and product variability [14] | Enables immediate adjustments to maintain quality specifications [14] |

| Digital Twin Simulation | Faster troubleshooting and refined process parameters [11] | Allows for virtual optimization without disrupting validated processes [11] |

Flexibility and Scalability for Advanced Therapies

The pharmaceutical landscape is increasingly dominated by personalized medicine and complex biologics, such as cell and gene therapies [16] [14] [11]. These treatments require a fundamental shift from large-scale batch production to small-batch, high-complexity manufacturing. Optimizing for this new paradigm requires flexible manufacturing models. Modular facilities, single-use technologies, and automated systems allow for rapid product changeovers and the production of smaller, customized batches without compromising quality [11]. This flexibility is a form of control, enabling manufacturers to scale production up or down efficiently and respond quickly to specific patient needs. The ability to optimize processes within this flexible framework is a critical competitive advantage for handling the growing pipeline of advanced therapies.

Implementation: Methodologies and Enabling Technologies

An Experimental Protocol for Sequential Simplex Optimization

Implementing a sequential simplex optimization requires a structured protocol. The following methodology provides a detailed roadmap for researchers and process scientists to systematically improve a manufacturing process.

Phase 1: Pre-Experimental Planning

- Define the Optimization Objective and Constraints: Clearly state the primary response variable to be optimized (e.g., percent yield, purity level, reaction rate). Simultaneously, define all constraints, including Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) that must be maintained and hard boundaries for Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) such as temperature or pressure [11].

- Select Factors and Ranges: Choose the

knumber of continuous factors to be optimized (e.g., reaction temperature, catalyst concentration, flow rate). Define the experimental range for each factor based on prior knowledge, ensuring the range is wide enough to induce a measurable response but narrow enough to avoid producing unacceptable material [12].

Phase 2: Sequential Experimentation

- Construct the Initial Simplex: The initial simplex is a geometric figure defined by

k+1experimental runs. For two factors, this is a triangle; for three, a tetrahedron, etc. The first run is often the current standard operating conditions, with subsequent runs adjusting the factors according to a predefined algorithm [12]. - Execute Experiments and Measure Response: Run the initial set of

k+1experiments in a randomized order to avoid bias. Measure the response variable for each run. All experiments should be conducted under the same level of control and monitoring as standard production. - Apply the Simplex Algorithm: The algorithm proceeds by comparing the responses and generating a new experimental condition. The core rules are:

- Reflect: Identify the worst-performing vertex (lowest yield) and reflect it through the centroid of the opposite face.

- Expand: If the reflection point yields a better response than the current best, further expand in that direction.

- Contract: If the reflection point is worse than the second-worst point, contract back toward the centroid.

- Shrink: If no improvement is found, shrink the entire simplex towards the best vertex [12].

- Iterate Until Convergence: Continue the cycle of running experiments and applying the simplex rules. The simplex will adaptively move towards the optimum and will eventually contract around it, signaling convergence when no further significant improvement is found [12].

Phase 3: Post-Optimization Analysis

- Model the Region of the Optimum: Once the optimum region is located, use a classical experimental design (e.g., a central composite design) to model the response surface in that specific area. This provides a detailed understanding of how the factors interact and affect the response, finalizing the process understanding and solidifying the new, optimized control strategy [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of advanced optimization protocols relies on a suite of specific reagents and technological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Process Optimization

| Item/Category | Primary Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Defined Cell Culture Media | Provides consistent, reproducible growth conditions for biopharmaceutical processes; variations can be a key factor in simplex optimization. |

| High-Purity Process Reagents & Solvents | Ensures that changes in process response are due to CPP variations, not impurities in reactants; critical for green chemistry initiatives. |

| Stable Reference Standards | Allows for precise calibration of analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC, MS) to accurately measure CQAs as response variables. |

| Specialized Catalysts & Ligands | Factors in reaction optimization for APIs; their concentration and type can be variables in a simplex designed to maximize yield. |

| Functionalized Chromatography Resins | Key for purification process optimization; factors like ligand density and buffer pH can be optimized for purity and recovery. |

| In-Line Sensor Probes (pH, DO, etc.) | Enables real-time monitoring of CPPs and provides data for PAT, forming the data backbone of the control strategy. |

Enabling Digital Infrastructure

Modern optimization is inseparable from digitalization. Key technologies include:

- Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) and Process Analytical Technology (PAT): MES digitizes batch record management and enables real-time data capture, while PAT uses in-line sensors for immediate quality assessment, creating a closed-loop system where data from one batch informs the optimization of the next [11].

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: These technologies move beyond simple monitoring. AI/ML can predict equipment failures, optimize yields by identifying complex patterns in historical data, and even suggest new experimental points in an optimization routine, accelerating the entire cycle [16] [14] [15].

- Cloud-Based Data Platforms: These platforms provide the essential foundation for data integration, offering secure, centralized storage and enabling real-time data sharing across R&D, manufacturing, and quality control units. This ensures all stakeholders work from a "single source of truth" [14].

- Digital Twin Technology: A digital twin is a virtual replica of a manufacturing process or entire facility. It allows for "what-if" scenarios to be simulated and optimized virtually at no risk to actual production, before implementing changes in the real world. This drastically reduces the time and cost of process optimization and scale-up [11].

The integration of controlled optimization strategies, rooted in EVOP and supercharged by modern digital technologies, is no longer a theoretical advantage but a strategic imperative for the pharmaceutical industry. The key takeaway is that control and optimization are not opposing forces. A well-controlled process, understood through the lenses of QbD and monitored with advanced PAT, provides the stable and predictable foundation upon which effective, safe, and compliant optimization can be built. Methodologies like the sequential simplex offer a structured path to efficiency gains, while AI, continuous manufacturing, and digital twins provide the technological muscle to achieve them at scale.

Companies that master this balance will be uniquely positioned to thrive amid the sector's headwinds—including pricing pressures, patent expirations, and the complexity of new modalities [10] [15]. They will achieve not only superior cost-effectiveness and operational resilience but also the agility to lead in the new era of personalized medicine. The future of pharmaceutical manufacturing belongs to those who can deliberately and systematically evolve their processes without ever losing control.

In the realm of multi-factor optimization, the Simplex method stands as a cornerstone mathematical procedure for systematic improvement. While numerous optimization techniques exist, Simplex distinguishes itself through its elegant geometric foundation and practical implementation efficiency. This whitepaper explores the geometric principles underpinning Simplex methodologies and their application in process optimization, with particular emphasis on evolutionary operation (EVOP) contexts relevant to research scientists and drug development professionals.

The fundamental premise of Simplex optimization rests on navigating a geometric structure called a simplex—a generalization of a triangle or tetrahedron to n dimensions—to locate optimal process conditions. Unlike traditional response surface methodology that requires large, potentially disruptive perturbations, Simplex-based approaches enable gradual process improvement through small, controlled changes, making them particularly valuable for full-scale production environments where maintaining product specifications is critical [4].

Geometric Foundations of the Simplex Method

Mathematical and Geometric Principles

The Simplex algorithm operates on linear programs in canonical form, seeking to maximize an objective function subject to inequality constraints. Geometrically, these constraints define a feasible region forming a convex polytope in n-dimensional space, with the optimal solution located at one of the vertices of this polytope [6].

The algorithm begins at a vertex of this polytope (often the origin) and iteratively moves to adjacent vertices along edges that improve the objective function value. This movement continues until no adjacent vertex offers improvement, indicating an optimal solution has been found. For a problem with k factors, the simplex is defined by k+1 points in the k-dimensional space [4] [17].

The geometric intuition can be visualized in two dimensions, where the feasible region is a polygon and the simplex forms a triangle moving along its edges. In three dimensions, the feasible region becomes a polyhedron, and the simplex is a tetrahedron. This geometric progression extends to higher dimensions, though visualization becomes increasingly difficult [17].

Computational Implementation

The computational implementation of the Simplex method uses a tabular approach known as the simplex tableau:

Where c represents the objective function coefficients, A contains the constraint coefficients, and b represents the right-hand side constraints. Through pivot operations that correspond to moving between vertices, the algorithm systematically improves the objective function until optimality is reached [6].

The efficiency of this method derives from its strategic navigation of the solution space—it evaluates only a subset of all possible vertices while guaranteeing finding the global optimum for linear problems. This makes it substantially more efficient than exhaustive search methods, particularly for problems with numerous variables [18].

Simplex versus Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) Methods

Comparative Analysis in Modern Context

While both Simplex and EVOP represent sequential improvement methods applicable to online process optimization, they differ significantly in approach and performance characteristics. A systematic comparison reveals their respective strengths under different experimental conditions [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Simplex and EVOP Methods Under Varied Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Simplex Method Performance | EVOP Method Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR < 250) | Prone to noise due to single measurements; slower convergence | More robust due to replicated measurements; maintains direction |

| High Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR > 1000) | Efficient movement toward optimum; minimal experimentation | Conservative progression; requires more measurements |

| Small Perturbation Size (dx) | May stagnate with insufficient SNR | Better maintains improvement direction |

| Large Perturbation Size (dx) | Faster progression but risk of overshooting | More controlled progression |

| Higher Dimensions (k > 4) | Requires fewer measurements per step | Becomes prohibitive due to measurement requirements |

| Computational Complexity | Simple calculations; minimal resources | More complex modeling required |

Practical Considerations for Research Applications

The choice between Simplex and EVOP methodologies depends critically on specific research constraints and objectives. EVOP operates by imposing small, designed perturbations to gain information about the optimum's direction, making it suitable for processes with substantial biological variability or batch-to-batch variation [4]. Its distinct advantage lies in handling either quantitative or qualitative factors, though it becomes prohibitively measurement-intensive with many factors.

Simplex offers superior simplicity in calculations and requires minimal experiments to traverse the experimental domain. However, its susceptibility to noise (due to single measurements per step) can limit effectiveness in highly variable systems. Modern implementations have adapted both methods for contemporary processes with higher dimensions and enhanced computational capabilities [4].

Simplex Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

Drug Formulation Optimization Protocol

The Simplex method has demonstrated particular utility in pharmaceutical formulation development, where multiple factors interact to determine drug release characteristics. The following experimental protocol outlines its application in developing prolonged-release felodipine formulations [19]:

Objective: Develop reservoir-type prolonged-release system with felodipine over 12 hours using Simplex optimization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient: Felodipine (Nivedita Chemicals PVT Ltd, India)

- Diluents: Lactose monohydrate (Pharmatose 80M, Pharmatose 200M), Microcrystalline cellulose (Vivapur 101, Vivapur 102)

- Binder: Polyvinylpyrrolidone (Kollidon K30, BASF)

- Film-forming polymers: Eudragit NE 40D, Eudragit RS 30D, Surelease E719040

- Pore-forming agent: HPMC (Methocel E5LV)

- Equipment: Aeromatic Strea 1 fluid bed coating system

Experimental Workflow:

Granule Preparation:

- Dissolve felodipine and PVP in alcohol to create 10% binder solution

- Spray drug-binder solution onto lactose-MC mixture using top-spray method

- Process parameters: Inlet air temperature 32-40°C, outlet air temperature 26-28°C, fan air 4-6 m³/min, atomizing pressure 0.5 atm

- Dry granules for 5 minutes at 32°C

Initial Coating Screening:

- Coat 100-150μm granules using bottom-spray (Würster) method

- Test three polymer types (Surelease, Eudragit RS 30D, Eudragit NE 40D)

- Evaluate polymer loading (10-25%) and pore former ratios (0-25%)

- Perform in vitro dissolution in phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) with 1% sodium lauryl sulfate

Optimization Phase:

- Use 315-500μm granules for final optimization

- Apply Surelease at 15-45% loading with HPMC pore former (5-15%)

- Quantify drug release using HPLC method

- Assess release kinetics using Higuchi and Peppas models

Results: Successful 12-hour release achieved using granules (315-500μm) coated with 45% Surelease containing varied pore former ratios, with drug release following Higuchi and Peppas kinetic models [19].

Experimental Design and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the pharmaceutical optimization protocol using the Simplex method:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Simplex Optimization in Pharmaceutical Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Polymer Dispersions (Surelease E719040, Eudragit NE 40D, Eudragit RS 30D) | Film-forming polymers for controlled drug release | Insoluble but permeable polymers create diffusion barriers; polymer type and loading percentage critically influence release kinetics |

| Pore-Forming Agents (HPMC - Methocel E5LV) | Create channels in polymer coating for drug release | Water-soluble component that dissolves upon contact with dissolution medium, creating diffusion pathways |

| Plasticizers (Triethyl Citrate) | Enhance polymer flexibility and film formation | Improves mechanical properties of polymeric coatings, preventing cracking during processing and dissolution |

| Diluents (Lactose Monohydrate, Microcrystalline Cellulose) | Provide bulk and determine granule structural characteristics | Particle size and porosity influence drug release profiles; different grades (Pharmatose 80M/200M, Vivapur 101/102) offer varying properties |

| Fluid Bed Coating System (Aeromatic Strea 1) | Apply uniform polymeric coatings to granules | Enables precise control of coating parameters; top-spray for granulation, bottom-spray (Würster) for coating applications |

Implementation Framework and Technical Considerations

Modern Adaptations and Green Chemistry Principles

Contemporary applications of Simplex optimization increasingly incorporate principles of green chemistry, particularly in pharmaceutical development. This includes the use of immobilized enzyme catalysts on novel supports such as magnetic nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and agricultural waste materials to improve sustainability and efficiency [20].

These advanced catalytic systems align with Simplex optimization by providing highly selective, efficient, and recyclable alternatives to traditional synthetic approaches. The immobilization of enzymes on magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide Fe₃O₄) enables easy separation from reaction mixtures using external magnetic fields, facilitating the iterative experimentation central to Simplex methodologies [20].

Computer-Aided Drug Design Integration

In early-phase drug discovery, Simplex methods integrate with computer-aided drug design (CADD) approaches to optimize compound structures for improved affinity, selectivity, metabolic stability, and oral bioavailability. The method facilitates systematic exploration of structure-activity relationships (SAR), structure-pharmacokinetics relationships, and structure-toxicity relationships [20].

This integration is particularly valuable for converting "hit" molecules with desired activity into "lead" compounds with optimized therapeutic properties—a process requiring careful balancing of multiple molecular parameters that naturally aligns with multi-factor Simplex optimization [20].

The geometric foundations of the Simplex concept provide a powerful framework for multi-factor optimization in research and industrial applications. Its systematic approach to navigating complex experimental spaces offers distinct advantages for pharmaceutical development, particularly when integrated with modern quality-by-design principles and green chemistry initiatives. For drug development professionals, understanding these foundational principles enables more effective implementation of Simplex methodologies in process optimization, formulation development, and drug discovery campaigns.

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical process optimization, employing structured, iterative experimentation during routine manufacturing to achieve continuous improvement. This whitepaper examines the strategic alignment of EVOP with modern regulatory frameworks including Quality by Design (QbD), Process Analytical Technology (PAT), and ICH guidelines Q8, Q9, and Q10. By integrating EVOP within these structured quality systems, pharmaceutical manufacturers can transform process optimization from a discrete development activity into an ongoing, science-based practice that maintains regulatory compliance while driving operational excellence. We present detailed experimental protocols, analytical frameworks, and implementation roadmaps to facilitate the adoption of EVOP within contemporary pharmaceutical development and manufacturing paradigms.

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP), first introduced by George Box in the 1950s, is experiencing a renaissance in pharmaceutical manufacturing driven by increased regulatory acceptance of science-based approaches [2]. EVOP is an optimization technique involving "experimentation done in real time on the manufacturing process itself" where "small changes are made to the current process, and a large amount of data is taken and analyzed" [2]. These changes are sufficiently minor to maintain product quality within specifications while accumulating sufficient data over multiple production batches to guide process improvements systematically.

The methodology aligns perfectly with the fundamental shift in pharmaceutical quality regulation from quality-by-testing (QbT) to Quality by Design (QbD) [21]. Traditional QbT systems relied on fixed manufacturing processes and end-product testing, often leading to inefficiencies, batch failures, and limited process understanding [21]. The QbD approach, codified in ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 guidelines, emphasizes building quality into products through thorough product and process understanding based on sound science and quality risk management [22] [23].

This whitepaper establishes the technical and regulatory framework for implementing EVOP within contemporary pharmaceutical quality systems, providing researchers and development professionals with practical methodologies to harness evolutionary optimization while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Theoretical Foundations: Integrating EVOP with QbD, PAT, and ICH Guidelines

Quality by Design (QbD) and ICH Q8 Framework

Quality by Design is "a systematic approach to development that begins with predefined objectives and emphasizes product and process understanding and process control, based on sound science and quality risk management" [21]. The ICH Q8 guideline establishes a science- and risk-based framework for designing and understanding pharmaceutical products and their manufacturing processes [23].

The core elements of QbD include:

- Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP): "A prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product that ideally will be achieved to ensure the desired quality, taking into account safety and efficacy" [23]

- Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): "Physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties or characteristics that should be within an appropriate limit, range, or distribution to ensure the desired product quality" [23]

- Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): Input material properties and process parameters that significantly impact CQAs [21]

- Design Space: "The multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality" [23]

- Control Strategy: "A planned set of controls, derived from current product and process understanding, that assures process performance and product quality" [23]

Table 1: QbD Elements and Their Corresponding EVOP Components

| QbD Element | EVOP Counterpart | Integration Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| QTPP | Optimization objectives | Provides clear optimization targets |

| CQAs | Response variables | Focuses optimization on critical quality metrics |

| Design Space | Operating region for experimentation | Defines safe boundaries for process adjustments |

| Control Strategy | Ongoing monitoring system | Ensures optimized parameters remain in control |

| Knowledge Management | Iterative learning process | Captures continuous improvement insights |

EVOP directly supports the QbD philosophy by providing a structured mechanism for continuous process improvement within the established design space, using the defined CQAs as optimization targets while respecting the control strategy.

Process Analytical Technology (PAT) and Real-Time Monitoring

PAT is defined as "a system of controlling manufacturing through timely measurements of critical quality attributes of raw and in-process materials" [22]. It serves as a crucial enabler for EVOP implementation by providing the high-frequency, real-time data necessary to detect subtle process improvements amid normal variation.

The PAT framework allows for:

- Continuous monitoring of CQAs during manufacturing

- Rapid detection of process trends and deviations

- Collection of sufficient data to support statistical significance despite small process adjustments

- Real-time release testing capabilities that reduce reliance on end-product testing

Within EVOP, PAT tools provide the data density required to distinguish signal from noise when making small, evolutionary process changes, making optimization feasible without compromising product quality or regulatory compliance.

ICH Quality Guidelines: Q8, Q9, Q10 Integration

The ICH quality guidelines form an interconnected framework that supports EVOP implementation:

- ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development): Provides the foundation for establishing design spaces within which EVOP can operate [23]

- ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management): Offers tools for identifying appropriate parameters for evolutionary optimization and assessing potential risks [23]

- ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System): Establishes the management framework for continuous improvement that EVOP operationalizes [22]

Together, these guidelines create a regulatory environment where "the demonstration of greater understanding of pharmaceutical and manufacturing sciences can create a basis for flexible regulatory approaches" [23] – precisely the flexibility that EVOP requires to be implemented effectively.

EVOP Methodologies: Simplex Methods and Experimental Protocols

Evolutionary Operation Fundamentals

EVOP operates through carefully designed, iterative process modifications during routine manufacturing. As Box and Draper stated, the original motivation was "the widespread and daily use of simple statistical design and analysis during routine production by process operatives themselves could reap enormous additional rewards" [2]. The fundamental EVOP process involves:

- Establishing a baseline operating condition

- Implementing small, statistically designed variations around this baseline

- Measuring process outcomes with sufficient precision to detect small improvements

- Analyzing results to determine the direction of optimization

- Systematically moving the operating point toward improved conditions

- Repeating the cycle until no further improvement is possible

This approach is particularly valuable for "processes that vary with input materials and environment" as it enables "tracking and maintaining optimality over time" [2].

Simplex-Based Optimization Methods

Simplex methods represent a specialized category of EVOP particularly suited to pharmaceutical applications. The simplex approach uses "a triangle in two variables, a tetrahedron in three variables, or a simplex (i.e., a multidimensional triangle) in four or more variables" as the basis for experimental patterns [2].

The Self-Directed Optimization (SDO) simplex method operates as follows:

- Begin with a patterned set of experiments across all interesting variables

- Identify the experiment that produced the worst result

- Discard this worst result and replace it with a new experiment according to a definite rule

- Continue this process of replacement until no further improvement is observed [2]

This method works "like a game of leapfrog," systematically exploring the parameter space while consistently moving away from poor performance regions [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Evolutionary Optimization Methods

| Method | Key Mechanism | Pharmaceutical Applications | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EVOP | Factorial designs around operating point | Established processes with multiple variables | Requires predefined design space |

| Simplex/SDO | Sequential replacement of worst point | Low-dimensional optimization problems | Easy to document and justify |

| Knowledge-Informed Simplex | Historical gradient estimation | Processes with high operational costs | Leverages existing knowledge management systems |

| Modified SPSA | Gradient approximation with perturbation | High-dimensional parameter spaces | Needs robust change control procedures |

Knowledge-Informed Simplex Search Methods

Recent advances in EVOP methodology include the development of knowledge-informed approaches that enhance optimization efficiency. The Knowledge-Informed Simplex Search based on Historical Quasi-Gradient Estimations (GK-SS) represents one such innovation [24].

This method:

- Generates quasi-gradient estimations from historical optimization data

- Reconstructs simplex search to incorporate gradient-like properties

- Utilizes "historical quasi-gradient estimations for each simplex generated during the optimization process to improve the method's search directions' accuracy in a statistical sense" [24]

- Is particularly valuable for processes with high operational costs where "the number of batches on quality control has a significant impact on the economy of the quality control process" [24]

For pharmaceutical applications, this approach enables more efficient optimization while maintaining the structured, documented approach required for regulatory compliance.

Implementation Framework: Protocols and Analytical Tools

EVOP Experimental Protocol for Pharmaceutical Processes

A robust EVOP implementation requires careful experimental design and execution:

Phase 1: Preparation and Risk Assessment

- Define specific optimization objectives aligned with QTPP

- Identify critical process parameters and quality attributes using risk assessment methods (ICH Q9)

- Establish operating boundaries based on existing design space

- Develop data collection protocols with appropriate PAT tools

Phase 2: Initial Experimental Cycle

- Implement a 2^k factorial or simplex design around the current operating point

- Maintain changes within established normal operating ranges

- Collect sufficient data to achieve statistical power despite small effect sizes

- Document all process parameters and material attributes

Phase 3: Analysis and Iteration

- Analyze results using statistical methods to identify improvement direction

- Calculate confidence intervals for effect estimates

- Implement process adjustments in the direction of improvement

- Repeat cycles until convergence or diminishing returns

Phase 4: Documentation and Control Strategy Update

- Document all experimental cycles and results

- Update control strategy and standard operating procedures as needed

- Submit significant changes through established regulatory pathways

- Implement ongoing monitoring to ensure improvements are maintained

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

The successful implementation of EVOP relies on appropriate statistical analysis to distinguish meaningful signals from process noise:

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

- Partition variability into assignable causes and random error

- Identify statistically significant factor effects

- Calculate confidence intervals for effect sizes

Evolutionary Operation Analysis

- Calculate effect estimates for each factor

- Determine standard errors considering within-batch and between-batch variation

- Construct confidence intervals to guide process adjustments

- Use sequential testing procedures to control Type I error rates

Table 3: Statistical Parameters for EVOP Implementation

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on EVOP Design | Regulatory Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence Level | 90-95% | Balances risk of false signals vs. missed improvements | Must be justified in protocol |

| Effect Size Detection | 0.5-1.0 sigma | Determines number of cycles required | Based on quality impact assessment |

| Number of Cycles | 5-20 | Dependent on process variability and effect size | Full documentation of all cycles |

| Batch Size | Normal production batches | Maintains representativeness of results | Consistent with validation batches |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for EVOP Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in EVOP | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAT Analytical Tools | NIR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy | Real-time monitoring of CQAs | Method validation required |

| Process Modeling Software | Design Expert, JMP, SIMCA | DoE design and analysis | Algorithm transparency |

| Data Management Systems | LIMS, CDS, Historians | Data integrity and traceability | 21 CFR Part 11 compliance |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | R, Python, SAS | Statistical analysis and visualization | Validation of custom algorithms |

| Process Control Systems | SCADA, DCS | Implementing process adjustments | Change control documentation |

Regulatory Strategy: Compliance and Documentation

Submission Framework for EVOP Activities

Successful regulatory alignment requires careful planning of how EVOP activities are presented in submissions:

Initial Marketing Authorization Applications

- Include EVOP strategy in Pharmaceutical Development section (ICH Q8)

- Describe how EVOP will be used for continuous improvement

- Define protocols for within-design-space adjustments

- Specify reporting thresholds for changes

Post-Approval Changes

- Document EVOP cycles within pharmaceutical quality system

- Implement changes according to predefined protocols

- Submit annual reports for minor changes within design space

- Submit prior approval supplements for changes outside design space

Quality System Documentation

- Standard Operating Procedures for EVOP implementation

- Training programs for operational staff

- Change control procedures for implemented optimizations

- Knowledge management systems for captured learning

ICH Guideline Integration and Harmonization

The recent consolidation of ICH stability testing guidelines into a single unified document (ICH Q1 Step 2 Draft, 2025) reflects a broader trend toward harmonization and science-based approaches [25]. This consolidation "combines the core concepts of Q1A-F and Q5C into a single, unified guideline" and "introduces a more modern structure and expands the scope to include emerging therapeutic modalities" [25].

Similarly, EVOP implementation benefits from this harmonized approach by:

- Providing consistent expectations across regulatory jurisdictions

- Supporting science- and risk-based decisions

- Enabling more efficient regulatory reviews

- Facilitating global manufacturing optimization

Case Studies and Experimental Data

Medium Voltage Insulator Manufacturing (Analogous Process)

While not a pharmaceutical application, quality optimization in medium voltage insulator manufacturing demonstrates EVOP principles applicable to pharmaceutical processes. A knowledge-informed simplex search method applied to epoxy resin automatic pressure gelation (APG) achieved quality specifications by optimizing process conditions "with the least costs" [24].

Key findings:

- Traditional quality control methods were "suboptimal, time-consuming, and experience-dependent" [24]

- The GK-SS method "utilized the historical quasi-gradient estimations for each simplex generated during the optimization process to improve the method's search directions' accuracy in a statistical sense" [24]

- Experimental results "showed that the method is effective and efficient in the quality control" [24]

Pharmaceutical Application Framework

For pharmaceutical applications, EVOP has been applied to unit operations including:

Fluid Bed Granulation

- Critical process parameters: inlet air temperature, binder spray rate, air flow rate

- Critical quality attributes: particle size distribution, bulk density, flowability

- EVOP approach: sequential optimization of multiple parameters

Roller Compaction

- Critical process parameters: API flow rate, lubricant flow rate, pre-compression pressure

- Critical quality attributes: tablet weight, dissolution, hardness

- EVOP strategy: simplex optimization of critical parameters

Hot Melt Extrusion

- Critical material attributes: lipid concentration, surfactant concentration

- Critical process parameters: screw speed, temperature profile

- EVOP implementation: knowledge-informed sequential optimization

Evolutionary Operation methods, particularly simplex-based approaches, represent a powerful methodology for continuous process improvement in pharmaceutical manufacturing. When properly aligned with QbD principles, PAT tools, and ICH guidelines, EVOP transforms from a theoretical optimization technique to a practical, compliant approach for achieving manufacturing excellence.

The integration of EVOP within modern pharmaceutical quality systems enables:

- Science-based continuous improvement within approved design spaces

- Systematic accumulation of process knowledge throughout product lifecycle

- More efficient and robust manufacturing processes

- Regulatory flexibility through demonstrated process understanding

As pharmaceutical manufacturing evolves toward continuous processes and advanced technologies, EVOP methodologies will play an increasingly important role in maintaining quality while driving operational efficiency. Future developments in AI-driven modeling, real-time analytics, and regulatory science will further enhance the application of evolutionary optimization in pharmaceutical contexts.

Evolutionary Operation (EVOP), introduced by George Box in 1957, is a statistical process optimization methodology designed for the systematic improvement of full-scale production processes through small, deliberate perturbations [1]. Framed within broader research on EVOP and Simplex methods, this guide delineates the ideal application scenarios and critical boundaries for EVOP, with a specific focus on its relevance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. While the classic Simplex method offers a heuristic alternative for numerical optimization and low-dimensional factor spaces, EVOP's structured, designed-experiment approach provides distinct advantages in contexts requiring high operational safety and reliability, such as pharmaceutical manufacturing and bioprocess development [4] [1].

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis with Simplex

EVOP operates on the principle of introducing small, planned variations to process inputs (factors) during normal production runs. The effects on key output characteristics (responses) are measured and analyzed for statistical significance against experimental error. This cyclical process of variation and selection of favorable variants enables continuous, evolutionary improvement without disrupting production or generating non-conforming product [1].

A critical understanding of EVOP is illuminated by contrasting it with the Simplex method. The table below summarizes key distinctions.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of EVOP and Simplex Methods

| Feature | Evolutionary Operation (EVOP) | (Basic) Simplex Method |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Planned, factorial designed experiments with small perturbations [1]. | Heuristic, geometric progression through factor space via reflection of the least favorable point [4] [1]. |

| Experimental Design | Typically uses full or fractional factorial designs (e.g., 2^𝑘) often with center points [1]. | A simplex geometric figure (e.g., a triangle for 2 factors) with k+1 initial points [1]. |

| Perturbation Size | Small, fixed increments to maintain product quality [4] [1]. | Step size is fixed in the basic version; can be variable in adaptations like Nelder-Mead [4]. |

| Information Usage | Uses data from all points in a designed cycle to build a statistical model and determine significant effects [1]. | Uses only the worst-performing point to determine the next step, making it prone to noise [4]. |

| Primary Strength | Statistical rigor, safety for full-scale processes, suitability for tracking drifting processes [4] [1]. | Computational simplicity and minimal number of experiments per step [4]. |