From Green to White: The Evolution of Sustainable Analytical Chemistry Principles in Pharmaceutical Research

This article explores the transformative evolution of sustainable practices in analytical chemistry, tracing the journey from foundational Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles to the holistic framework of White Analytical Chemistry...

From Green to White: The Evolution of Sustainable Analytical Chemistry Principles in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative evolution of sustainable practices in analytical chemistry, tracing the journey from foundational Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles to the holistic framework of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of sustainable methodologies, practical optimization strategies, and cutting-edge validation tools. The content synthesizes the latest 2025 research to offer actionable insights for integrating environmental stewardship with uncompromised analytical performance and economic feasibility in biomedical and clinical research settings, addressing both current applications and future directions for the field.

The Roots of Change: Tracing Green Analytical Chemistry from Principles to Practice

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a specialized subdiscipline in the year 2000, born from the broader green chemistry movement that gained significant momentum throughout the 1990s [1] [2] [3]. While green chemistry principles, as formulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner in 1998, provided a revolutionary framework for sustainable chemical synthesis, they proved only partially applicable to the unique challenges of analytical chemistry [1] [2]. The pioneering work of Anastas and Warner established the foundational 12 principles of green chemistry, which primarily targeted industrial-scale processes and product design, emphasizing waste prevention, atom economy, and reduced hazard [2] [4]. However, analytical chemists soon recognized that key concepts like atom economy—which focuses on maximizing the incorporation of starting materials into final products—held little relevance for analytical methodologies where the goal is measurement rather than synthesis [1].

This recognition sparked a critical evolution in green thinking specific to analytical practice. Galuszka, Migaszewski, and Namieśniki addressed this gap in 2013 by systematically adapting the original principles to create the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [1] [2]. This transformation marked a significant milestone, shifting the focus from chemical synthesis to the specific environmental concerns of analytical laboratories, including sample consumption, energy requirements of instrumentation, and waste generation from analytical procedures [1]. The genesis of GAC represents more than a simple translation of principles; it constitutes a fundamental rethinking of how environmental sustainability can be integrated into the practice of chemical analysis while maintaining the high-quality data required for scientific and regulatory purposes.

Foundational Frameworks: From Green Chemistry to GAC

The Original 12 Principles of Green Chemistry

The bedrock of the entire green chemistry movement was established by Paul Anastas and John Warner in their seminal 1998 book "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice" [2] [4]. These principles were formulated to address the environmental impact of chemical processes at an industrial scale, focusing on pollution prevention through fundamental design changes. The twelve principles encompass a comprehensive approach to sustainable chemical design, process management, and hazard reduction [5] [4]:

- Prevention: It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created.

- Atom Economy: Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product.

- Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses: Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment.

- Designing Safer Chemicals: Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity.

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used.

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Energy requirements should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized.

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable.

- Reduce Derivatives: Unnecessary derivatization (use of blocking groups, protection/deprotection, temporary modification of physical/chemical processes) should be minimized or avoided if possible.

- Catalysis: Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents.

- Design for Degradation: Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products.

- Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention: Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances.

- Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention: Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents.

The Adapted 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The transformation of these principles for analytical chemistry resulted in a dedicated framework that addresses the specific concerns of analytical laboratories. The table below systematically compares the original principles with their analytical adaptations, highlighting the conceptual shift from synthesis to analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Original Green Chemistry Principles and Adapted Green Analytical Chemistry Principles

| Original Green Chemistry Principle | Green Analytical Chemistry Principle | Key Shifts in Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention of waste | Direct analytical techniques should be applied to avoid sample treatment | From minimizing synthesis waste to eliminating sample preparation steps |

| Atom economy | Minimal sample size and minimal number of samples are goals | From maximizing atom incorporation to reducing material consumption for analysis |

| Less hazardous chemical syntheses | In situ measurements should be performed | From safer synthesis pathways to enabling direct analysis in the field |

| Designing safer chemicals | Integration of analytical processes & operations saves energy/reagents | From molecular design to process streamlining and automation |

| Safer solvents & auxiliaries | Automated & miniaturized methods should be selected | From solvent substitution to fundamental method redesign |

| Design for energy efficiency | Derivatization should be avoided | From process energy efficiency to eliminating unnecessary chemical modification |

| Use of renewable feedstocks | Generation of large volume of analytical waste should be avoided | From sustainable sourcing to direct waste reduction |

| Reduce derivatives | Multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods are preferred | From reducing chemical derivatives to maximizing analytical information |

| Catalysis | Consumption of energy should be minimized | From catalytic efficiency to instrumental energy management |

| Design for degradation | Reagents obtained from renewable source should be preferred | From product degradability to sustainable reagent sourcing |

| Real-time analysis for pollution prevention | Toxic reagents should be eliminated or replaced | From process monitoring to direct hazard reduction in analytical methods |

| Inherently safer chemistry for accident prevention | Operator safety should be increased | From process safety to analyst protection |

This adapted framework [1] prioritizes the unique environmental challenges in analytical laboratories, with particular emphasis on:

- Direct measurement techniques that eliminate extensive sample preparation [1]

- Miniaturization and automation to reduce solvent consumption and waste generation [1] [6]

- Instrumental energy efficiency alongside reduced reagent toxicity [1]

- Operator safety through reduced exposure to hazardous materials [1] [7]

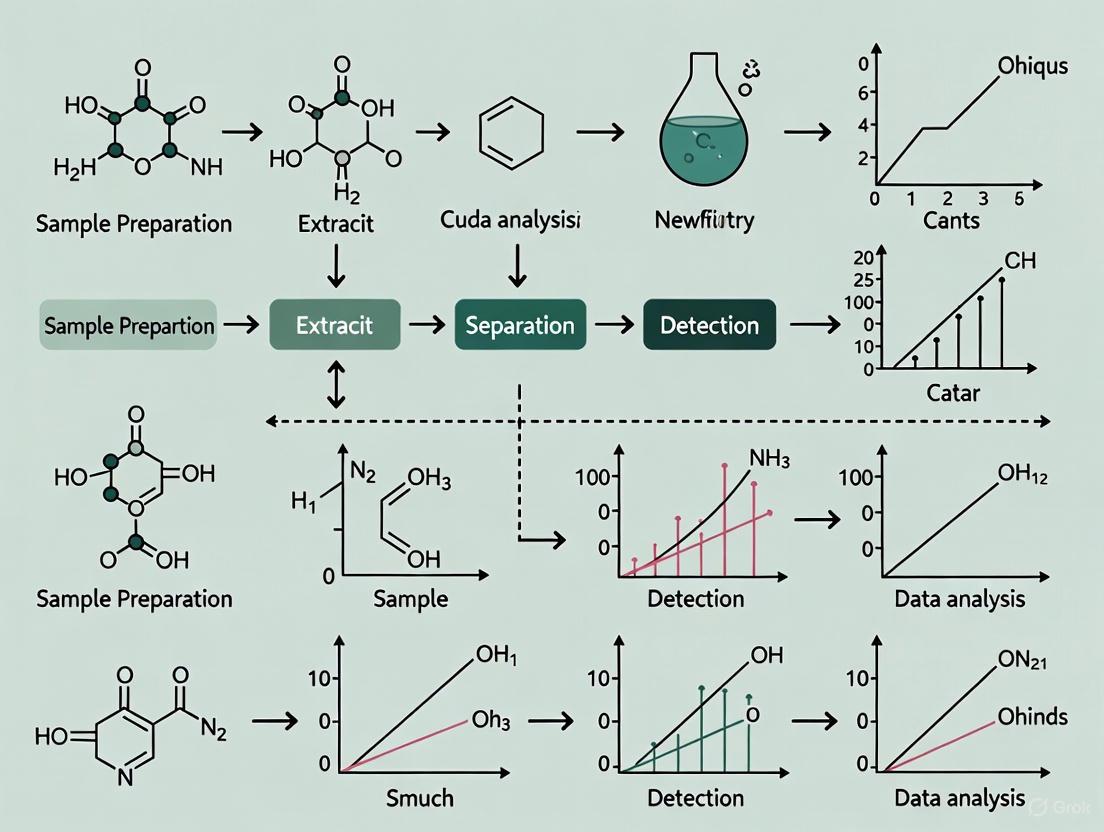

The visual below maps the evolutionary pathway from the original green chemistry principles to the specialized domain of Green Analytical Chemistry.

Figure 1: The Historical Evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry from Broader Green Chemistry Principles

Quantitative Metrics and Assessment Methodologies

The development of principle-based frameworks necessitated the creation of standardized metrics to quantify and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods. These tools transform theoretical principles into actionable, measurable parameters.

Core Metrics for Greenness Assessment

Multiple assessment tools have been developed, each with distinct approaches and foci, from simple pictograms to comprehensive scoring systems [8] [7] [3].

Table 2: Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Tools and Metrics

| Assessment Tool | Type | Scoring System | Key Parameters Assessed | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Pictogram | Binary (Pass/Fail) for 4 criteria | PBT (Persistent, Bioaccumulative, Toxic), Hazardous, Waste Volume, Corrosivity | Initial screening of methods [3] |

| Analytic Eco-Scale | Quantitative | Penalty points subtracted from ideal 100 | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste generation, operator hazard | Comparative method assessment [8] [3] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Pictogram | Color-coded (green-yellow-red) for 15 parameters | Sample collection, preparation, transportation, reagent use, instrumentation, waste | Comprehensive method evaluation [7] [3] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Pictogram & Numerical | 0-1 scale based on 12 GAC principles | All 12 GAC principles with weighted importance | Holistic assessment and communication [7] [3] |

| AGREEprep | Pictogram & Numerical | 0-1 scale focusing on sample prep | Sample, reagent, and energy consumption in preparation steps | Specialized sample preparation evaluation [3] |

| AGSA (Analytical Green Star Analysis) | Star Diagram & Numerical | 0-100 scale with star area | Toxicity, waste, energy, miniaturization, operator safety | Visual comparison of multiple methods [3] |

Experimental Application of Assessment Tools

The practical application of these metrics is exemplified in a case study evaluating a Sugaring-Out Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (SULLME) method for determining antiviral compounds [3]. The methodology and assessment results demonstrate how these tools provide complementary insights:

Experimental Protocol: SULLME Method

- Sample Preparation: A 1 mL sample volume is mixed with a sugaring-out agent to induce phase separation.

- Extraction: Target analytes partition into the organic phase in a miniaturized setup (<10 mL total solvent).

- Analysis: Semiautomated instrumental analysis with moderate throughput (2 samples/hour).

- Waste Management: No specific treatment for generated waste (>10 mL/sample).

Assessment Results and Interpretation:

- MoGAPI Score: 60/100 - Highlights strengths in green solvents and microextraction, but notes concerns about waste volume and moderate reagent toxicity [3].

- AGREE Score: 56/100 - Confirms benefits of miniaturization and avoided derivatization, but identifies issues with solvent flammability and low throughput [3].

- AGSA Score: 58.33/100 - Visual star diagram reveals strengths in miniaturization but weaknesses in manual handling and hazard pictograms [3].

- CaFRI Score: 60/100 - Indicates moderate energy consumption (0.1-1.5 kWh/sample) but notes non-renewable energy sources and significant organic solvent use [3].

The workflow for applying these assessment tools follows a systematic process, as visualized below:

Figure 2: Workflow for Comprehensive Greenness Assessment of Analytical Methods

Practical Implementation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Miniaturization and Alternative Techniques

The implementation of GAC principles has led to significant methodological shifts in pharmaceutical analysis, particularly through the adoption of miniaturized techniques that dramatically reduce solvent consumption and waste generation [6]. These approaches represent practical applications of the prevention and waste reduction principles core to GAC.

Capillary Liquid Chromatography (cLC) and Nano-LC: These techniques typically reduce solvent consumption by 90-99% compared to conventional HPLC methods while maintaining high separation efficiency, directly addressing Principles 1 (waste prevention) and 7 (reducing derivatives) [6].

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) and Electrokinetic Chromatography (EKC): Various CE modes (CZE, MEKC, CITP) provide versatile separation mechanisms with minimal solvent requirements. EKC has proven particularly valuable for chiral separations of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), eliminating the need for derivatization and reducing toxic solvent use in accordance with Principles 3 (less hazardous synthesis) and 6 (avoiding derivatization) [6].

Microextraction Techniques: Methods such as SULLME (Sugaring-Out Liquid-Liquid Microextraction) enable sample preparation and pre-concentration with total solvent volumes below 10 mL, directly implementing Principle 2 (minimal sample size) and Principle 5 (miniaturization) [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The transition to greener analytical methodologies requires specific reagents and materials that enable miniaturization, reduce toxicity, and maintain analytical performance.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC | GAC Principle Addressed | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., Ethyl Lactate, Cyrene) | Replacement for toxic traditional solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) | Principle 5: Safer solvents & auxiliaries | Extraction medium in microextraction techniques [3] |

| Water-based Systems | Green alternative to organic solvents for separations | Principle 5: Safer solvents & auxiliaries | Mobile phase in reversed-phase chromatography [5] |

| Chiral Selectors (e.g., Cyclodextrins, Macrocyclic Antibiotics) | Enable direct chiral separations without derivatization | Principle 6: Avoidance of derivatization | Chiral EKC for API enantiomer separation [6] |

| Switchable Solvents | Solvents that change properties with stimuli for easy recovery/reuse | Principle 11: Toxic reagent replacement | Sample preparation with solvent recovery [7] |

| Miniaturized Columns (cLC, nano-LC) | Enable dramatic reduction in mobile phase consumption | Principle 5: Automated & miniaturized methods | High-resolution separations with µL/min flow rates [6] |

| Renewable Sorbents | Biodegradable materials for sample preparation | Principle 10: Reagents from renewable sources | Solid-phase extraction using natural materials [1] |

The genesis and evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry from Anastas and Warner's original principles to modern adaptations represents a fundamental transformation in how the analytical chemistry community approaches method development and implementation. This journey has progressed from simply applying general green chemistry concepts to creating a specialized framework with dedicated principles, metrics, and practical methodologies tailored to the unique challenges of analytical science [1] [2].

The future trajectory of GAC points toward several key developments. First, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for method optimization and greenness prediction promises to accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices [3]. Second, the ongoing refinement of assessment tools will likely address current limitations, particularly regarding the entire lifecycle of reagents and equipment, moving beyond just operational impacts [3]. Third, the growing emphasis on carbon footprint assessment through tools like CaFRI aligns analytical chemistry with broader climate goals [3]. Finally, the educational integration of GAC principles into analytical chemistry curricula ensures that future generations of scientists will be equipped with sustainability as a core competency [7].

The multidimensional impacts of GAC extend beyond environmental benefits to encompass economic advantages through reduced reagent consumption and waste disposal costs, improved operator safety, and maintained—and often enhanced—analytical performance [7] [2]. As pharmaceutical researchers and analytical scientists continue to face increasing pressure to implement sustainable practices, the principles and tools of GAC provide a structured pathway to reconcile analytical excellence with environmental responsibility. The genesis of GAC represents not merely an academic exercise but a practical imperative for the future of analytical science in an increasingly sustainability-conscious world.

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative discipline that integrates the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, aiming to reduce the environmental and human health impacts traditionally associated with chemical analysis [9]. This framework represents a fundamental shift in how chemical analysis is conducted, emphasizing environmental stewardship, sustainability, and efficiency while maintaining the high standards of accuracy and precision required in research and industrial applications [9]. The core principles of GAC provide a comprehensive strategy for reimagining analytical chemistry to meet the demands of sustainability, safety, and environmental responsibility, particularly in fields such as pharmaceutical development where analytical processes are ubiquitous [1].

The foundation of GAC lies in the 12 principles of green chemistry, which provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [9]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, the use of renewable feedstocks, energy efficiency, and the avoidance of hazardous substances, all of which are central to reimagining the role of analytical chemistry in today's environmental and industrial landscape [9]. While traditional green chemistry principles were initially designed for synthetic chemistry, they have been adapted and refined specifically for analytical applications, addressing the unique challenges and requirements of chemical analysis [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing GAC principles is becoming increasingly crucial not only for environmental reasons but also for economic efficiency and regulatory compliance [7]. By minimizing the use of toxic reagents, reducing energy consumption, and preventing the generation of hazardous waste, GAC seeks to align analytical processes with the overarching goals of sustainability while maintaining the rigorous analytical standards required in pharmaceutical development [9] [7].

The Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Waste Prevention

Waste prevention stands as the first and most fundamental principle of Green Analytical Chemistry, emphasizing the design of analytical processes that avoid generating waste rather than managing it after formation [9] [1]. In traditional analytical methodologies, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis, hazardous waste generation represents a significant environmental concern, with many methods producing substantial volumes of solvent waste and contaminated materials [9]. The principle of waste prevention encourages a paradigm shift from end-of-pipe waste management to inherent waste avoidance through strategic methodological design.

Methodologies for Waste Reduction:

Miniaturization of Analytical Systems: The implementation of miniaturized methods and micro-extraction techniques dramatically reduces solvent consumption and waste generation while maintaining analytical performance [1] [10]. Techniques such as fabric phase sorptive extraction (FPSE), magnetic solid-phase extraction, capsule phase microextraction (CPME), and ultrasound-assisted microextraction enable effective analyte extraction and pre-concentration with minimal solvent volumes [10].

Direct Analytical Techniques: Applying direct analytical techniques that avoid extensive sample treatment significantly reduces the consumption of reagents and generation of waste [1]. These approaches minimize or eliminate the need for sample preparation steps that typically involve solvents and generate waste.

Analytical Method Volume Intensity (AMVI) Optimization: For HPLC methods, calculating and minimizing the AMVI provides a straightforward measure of material usage, focusing specifically on the total volume of solvents and reagents consumed per analytical run [3]. This metric helps researchers identify opportunities for waste reduction in separative methods.

Table 1: Waste Prevention Strategies in Analytical Chemistry

| Strategy | Traditional Approach | Green Alternative | Waste Reduction Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Liquid-liquid extraction with large solvent volumes | Microextraction techniques (e.g., SPME, FPSE) | Up to 90% solvent reduction |

| Sample Size | Large sample volumes (mL scale) | Minimal sample size (μL scale) | Reduced chemical consumption |

| Analysis Method | Multiple sample processing steps | Direct analysis techniques | Elimination of intermediate waste |

| Separation Techniques | Conventional HPLC columns | Short stationary phases or capillary systems | Reduced solvent consumption and waste generation |

Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

The principle of safer solvents and auxiliaries focuses on minimizing toxicity in reagents and solvents used during analysis, protecting both analysts and the environment [9]. This principle encourages the use of non-toxic, biodegradable, or less harmful solvents, reducing reliance on hazardous organic solvents that have traditionally dominated analytical chemistry [9] [1]. The transition to greener solvents represents one of the most significant shifts in modern analytical practice, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis where solvent consumption is substantial.

Green Solvent Alternatives:

Water and Aqueous Systems: Utilizing water-based analytical systems as a replacement for organic solvents provides the safest alternative, with no toxicity concerns and minimal environmental impact [9]. Methods such as sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) demonstrate the potential of aqueous systems for efficient analyte extraction [3].

Supercritical Fluids: Supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO₂) offers an excellent alternative to organic solvents, particularly in extraction and separation techniques like supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) [9]. scCO₂ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and easily removed from the analysis system without residual contamination.

Ionic Liquids: These low-melting point salts provide unique solvation properties with negligible vapor pressure, reducing inhalation hazards and environmental release [9]. Their tunable properties allow for customization to specific analytical applications.

Bio-based Solvents: Derived from renewable feedstocks, bio-based solvents such as those produced from agricultural waste or biomass offer biodegradable alternatives to petroleum-derived solvents [9]. These align with the principles of circular economy and sustainability.

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional and Green Solvents in Analytical Chemistry

| Solvent Type | Examples | Environmental & Health Concerns | Green Alternatives | Advantages of Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorinated Solvents | Dichloromethane, Chloroform | Ozone depletion, toxicity, carcinogenicity | Supercritical CO₂, Ionic liquids | Non-toxic, non-flammable, recyclable |

| Volatile Organic Compounds | Hexane, Acetone, Methanol | Air pollution, neurotoxicity, flammability | Bio-based solvents, Water | Biodegradable, renewable, safe |

| Aromatic Hydrocarbons | Benzene, Toluene, Xylene | Carcinogenicity, environmental persistence | Switchable solvents, Deep eutectic solvents | Low toxicity, biodegradable, tunable properties |

Energy Efficiency

Energy efficiency addresses the significant energy demands of analytical instrumentation and processes, urging the development of techniques that operate under milder conditions to lower energy consumption [9]. This principle is exemplified in the use of alternative energy sources and process optimization to accelerate analytical procedures without excessive energy inputs [9]. With growing concerns about climate change and carbon emissions, energy-efficient analytical methods are becoming increasingly important for reducing the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical analysis and other chemical measurements.

Energy-Efficient Analytical Techniques:

Microwave-Assisted Processes: Microwave-assisted extraction and digestion techniques significantly reduce processing time and energy consumption compared to conventional heating methods [9]. The direct energy transfer to the sample material improves efficiency while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance.

Ultrasound-Assisted Methods: Utilizing ultrasound energy for extraction, digestion, and other sample preparation steps enhances mass transfer and reaction rates, enabling processes to proceed more quickly and at lower temperatures [9]. This approach reduces overall energy demand while improving efficiency.

Room Temperature Operations: Designing analytical methods that function effectively at ambient temperature eliminates the energy requirements for heating or cooling, significantly reducing the carbon footprint of analytical procedures [9]. Techniques such as room-temperature phosphorescence and certain extraction methods exemplify this approach.

Miniaturized and Portable Devices: The development of miniaturized analytical systems and portable devices reduces energy requirements while enabling in-situ measurements that eliminate the need for sample transport [9] [1]. These systems often operate on battery power with minimal energy consumption compared to traditional benchtop instruments.

Table 3: Energy Consumption in Traditional vs. Green Analytical Techniques

| Analytical Technique | Traditional Energy Demand | Energy-Efficient Alternative | Energy Reduction | Additional Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Extraction | Soxhlet extraction (hours, continuous heating) | Microwave-assisted extraction (minutes) | 50-90% reduction | Faster processing, better yields |

| Chromatographic Separation | Conventional HPLC | Ultra-HPLC or capillary LC | 30-70% reduction | Higher throughput, reduced solvent use |

| Sample Digestion | Conventional heated digestion | Ultrasound-assisted digestion | 40-80% reduction | Faster digestion, lower temperatures |

| On-site Analysis | Laboratory analysis with transport | Portable devices with in-situ measurement | 60-95% reduction | Real-time data, no transport needed |

Implementation and Assessment of GAC Principles

Integrated Methodologies and Workflows

The successful implementation of GAC principles requires a holistic approach that integrates multiple green strategies throughout the entire analytical workflow. Modern analytical chemistry offers opportunities to combine waste prevention, safer solvents, and energy efficiency in complementary ways that enhance overall sustainability without compromising analytical performance [1]. For pharmaceutical researchers, this integrated approach is essential for developing methods that align with both scientific and corporate sustainability goals.

Experimental Protocols for Green Analysis:

Green Sample Preparation Protocol: Implement microextraction techniques such as solid-phase microextraction (SPME) or liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) using bio-based solvents or ionic liquids. Utilize ultrasound or microwave assistance to reduce extraction time and energy consumption. This integrated approach addresses multiple GAC principles simultaneously [1] [10].

Green Separation Protocol: Employ supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) or water-based chromatography using miniaturized column systems. Optimize methods for high throughput to reduce analysis time and energy consumption per sample. Implement post-analysis solvent回收 systems to minimize waste [9] [3].

Direct Analysis Protocol: Develop methods using non-invasive techniques such as near-infrared spectroscopy or Raman spectroscopy that require minimal or no sample preparation. These approaches eliminate solvent use and reduce waste generation while providing rapid results [1].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of core GAC principles into analytical method development:

Assessment Tools for GAC Principles

The evaluation of how well analytical methods adhere to GAC principles has been formalized through the development of specialized assessment tools. These tools provide standardized metrics for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical procedures, enabling researchers to quantify and compare the greenness of different methods [11] [3]. For drug development professionals, these assessment tools are invaluable for demonstrating regulatory compliance and corporate sustainability commitments.

Key Green Assessment Tools:

AGREE (Analytical GREEnness): This comprehensive tool evaluates analytical methods based on all 12 principles of GAC, providing both a pictogram representation and a numerical score between 0 and 1 [7] [3]. The tool offers a user-friendly interface and facilitates direct comparison between methods, though it may involve some subjective weighting of criteria [3].

GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index): GAPI assesses the entire analytical process from sample collection through preparation to final detection using a five-part, color-coded pictogram [7] [3]. This allows users to visually identify high-impact stages within a method, though it lacks an overall greenness score [3].

NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index): As one of the earliest assessment tools, NEMI provides a simple pictogram indicating whether a method complies with four basic environmental criteria [3]. While user-friendly, its binary structure limits its utility for distinguishing degrees of greenness [3].

Analytical Eco-Scale: This metric applies penalty points to non-green attributes, which are subtracted from a base score of 100 [3]. The resulting score facilitates direct comparison between methods but relies on expert judgment in assigning penalty points [3].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different GAC assessment tools and their evaluation criteria:

The Research Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Green Analysis

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Traditional Approach | Green Alternative | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Extraction solvents, Mobile phase additives | Volatile organic solvents (VOCs) | Tunable ionic liquids with negligible vapor pressure | Non-flammable, recyclable, low toxicity |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction solvent, Chromatographic mobile phase | Organic solvents (hexane, methanol) | Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) and chromatography (SFC) | Non-toxic, easily removed, tunable solvation |

| Bio-based Solvents | Sample preparation, Extraction media | Petroleum-derived solvents | Solvents from renewable resources (e.g., limonene, ethanol) | Biodegradable, sustainable, reduced carbon footprint |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Sample preparation, Extraction | Liquid-liquid extraction with solvent volumes | Solventless extraction using coated fibers | Minimal waste, reusable, easy automation |

| Switchable Solvents | Extraction media, Reaction solvents | Conventional solvents with fixed properties | Solvents with tunable hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity | Recyclable, reduced consumption, versatile |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Extraction media, Green solvents | Ionic liquids or organic solvents | Natural compound-based eutectic mixtures | Biodegradable, low cost, low toxicity |

The core principles of Green Analytical Chemistry—waste prevention, safer solvents, and energy efficiency—represent fundamental pillars in the transformation of analytical methodologies toward greater sustainability and environmental responsibility [9] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles provide a framework for developing analytical methods that not only meet scientific and regulatory requirements but also align with broader environmental goals and corporate social responsibility initiatives [7].

The implementation of these principles is increasingly supported by advanced assessment tools that provide quantitative metrics for evaluating environmental impact [11] [3]. The evolution from Green Analytical Chemistry to the more comprehensive framework of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances environmental impact with analytical performance and practical considerations, demonstrates the continuing maturation of sustainable approaches in analytical science [10]. This holistic perspective ensures that green methods maintain the high standards of accuracy, precision, and reliability required in pharmaceutical research and other analytical applications.

As analytical chemistry continues to evolve, the integration of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, advanced automation, and novel materials will further enhance the implementation of GAC principles [9]. By embracing these innovations and maintaining commitment to continuous improvement, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of analytical processes while driving scientific progress and innovation [9] [7]. The ongoing development and refinement of GAC principles will undoubtedly play a pivotal role in shaping a more sustainable future for analytical chemistry and its diverse applications across scientific disciplines.

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative discipline that aligns analytical practices with the global sustainability imperative. While originating from the foundational 12 principles of green chemistry established by Anastas and Warner in 1998, analytical chemists recognized that these guidelines required significant adaptation to address the unique challenges and workflows of analytical laboratories [1] [12]. The original principles, though groundbreaking, were primarily designed for synthetic chemistry and industrial processes, leaving critical gaps in their direct application to analytical methodologies [1].

This recognition led to the development of a specialized framework specifically for analytical chemistry. In 2013, Gałuszka and colleagues proposed the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, providing a targeted roadmap for reducing the environmental impact of chemical analysis [1] [12]. To enhance practical implementation and recall, these principles were subsequently organized into the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic—a structured approach that encapsulates the core objectives of GAC into a memorable framework [13]. This evolution from broad green chemistry principles to a specialized, user-friendly mnemonic represents a significant advancement in making sustainable practices accessible to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The diagram below illustrates the evolutionary pathway from traditional chemistry to the structured SIGNIFICANCE framework:

Deconstructing the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic: Principles and Applications

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides a systematic approach to implementing Green Analytical Chemistry by transforming abstract principles into actionable laboratory practices. Each letter represents a specific strategic direction for minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance [13] [1].

Comprehensive Principle Breakdown

S - Sample Management and Direct Analysis The first principle emphasizes direct analytical techniques that avoid or minimize sample treatment. This approach significantly reduces the consumption of solvents, reagents, and energy associated with extensive sample preparation [1]. Modern instrumentation enables direct analysis through techniques such as:

- Non-invasive spectroscopy (NIR, Raman) for solid samples without extraction

- In-situ sensors for real-time monitoring of environmental parameters

- Direct sample introduction systems that eliminate extraction and purification steps

I - In-situ Measurements Performing measurements in-situ at the sample source eliminates the need for transportation, preservation, and extensive laboratory processing [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in environmental monitoring, process analytical technology (PAT) in pharmaceutical manufacturing, and field-based analysis. Implementation strategies include:

- Portable and handheld analytical devices for on-site determination

- Flow-through analysis systems for continuous monitoring

- Embedded sensors in industrial processes to enable real-time quality control

G - Green Sample Preparation and Automation This principle advocates for automated and miniaturized methods that enhance precision while reducing resource consumption [1] [12]. Automation improves reproducibility and enables the implementation of micro-scale techniques that dramatically reduce solvent usage. Key applications include:

- Automated solid-phase microextraction (SPME) for high-throughput sample preparation

- Microfluidic devices that operate with nanoliter to microliter volumes

- Lab-on-a-chip technologies that integrate multiple analytical steps

N - Non-Destructive Methodologies The preference for non-destructive techniques preserves sample integrity and eliminates waste generation from sample destruction [1]. This approach aligns with the circular economy model by enabling sample reuse or return to its original state. Implementation examples include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and spectroscopy for material characterization

- X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for elemental analysis without digestion

- Multivariate analysis of spectral data to extract multiple parameters from a single measurement

I - Integration of Analytical Processes and Operations Integration of analytical steps into continuous workflows saves energy, reduces reagent consumption, and minimizes potential contamination [1]. This principle focuses on connecting previously discrete operations to create streamlined processes:

- Online sample preparation coupled directly with separation systems

- Hyphenated techniques like LC-MS-MS that combine separation with detection

- Automated multi-step workflows that reduce manual intervention

F - Fast Methodologies and High-Throughput Implementing fast methodologies enhances laboratory efficiency and reduces energy consumption per analysis [1]. This principle emphasizes the importance of analysis time as a critical sustainability factor:

- Rapid separation techniques (UPLC, core-shell chromatography) that reduce run times

- High-throughput screening platforms for pharmaceutical development

- Parallel processing of multiple samples to increase efficiency

I - Intelligent Data Collection and Minimal Samples Applying intelligent data collection strategies through chemometrics minimizes the number of samples required without compromising data quality [1]. This approach includes:

- Design of Experiments (DoE) to maximize information from minimal experiments

- Strategic sampling protocols that reduce redundant analyses

- Multivariate calibration that extracts multiple parameters from single measurements

C - Clean Energy and Waste Reduction This principle focuses on minimizing energy consumption and preventing waste generation through method design [1]. Key implementations include:

- Energy-efficient instrumentation with standby modes and low power requirements

- Alternative energy sources (microwave, ultrasound) for extraction processes

- Waste segregation and recycling programs for laboratory materials

A - Alternative Solvents and Reagents Selecting alternative solvents with improved environmental, health, and safety profiles is fundamental to GAC [9] [1]. This includes:

- Bio-based solvents derived from renewable resources

- Water-based systems as replacements for organic solvents

- Ionic liquids and supercritical fluids with recyclability potential

N - Non-Use of Toxic Reagents The principle of eliminating or replacing toxic reagents protects both analysts and the environment [1]. Implementation strategies include:

- Alternative derivatization agents with lower toxicity

- Enzyme-based reagents for specific detection reactions

- Catalytic systems that replace stoichiometric reagents

C - Capacity for Multi-Analyte Determination Developing multi-analyte methods increases information density per analysis, reducing overall resource consumption [1]. This approach includes:

- Comprehensive chromatography with high peak capacity

- Mass spectrometric detection with selective monitoring of multiple analytes

- Array-based sensors for simultaneous determination of multiple parameters

E - End-of-Pipe Waste Management Proper management of analytical waste ensures responsible handling of materials that cannot be eliminated [1]. This includes:

- Solvent recycling systems for distillation and reuse

- Neutralization protocols for acidic or basic wastes

- Professional disposal services for hazardous materials

Table 1: SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic - Principle Implementation and Environmental Benefits

| Mnemonic Letter | Core Principle | Key Implementation Strategies | Primary Environmental Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | Direct Analysis | Non-invasive spectroscopy, in-situ sensors | Reduces solvent use, eliminates extraction waste |

| I | In-situ Measurements | Portable devices, field analysis kits | Eliminates transport, reduces sample containers |

| G | Automation & Miniaturization | Micro-extraction, lab-on-a-chip | Reduces reagent volumes by 10-1000x |

| N | Non-Destructive Methods | XRF, NMR, NIR spectroscopy | Enables sample reuse, eliminates digestion waste |

| I | Process Integration | Online SPE-LC-MS, coupled techniques | Reduces intermediate handling, saves energy |

| F | Fast Methodologies | UPLC, FIA, high-throughput screening | Reduces energy consumption per analysis |

| I | Minimal Samples | DoE, strategic sampling, chemometrics | Reduces overall material consumption |

| C | Clean Energy | Microwave, ultrasound, LED detection | Lowers energy demand by 30-90% |

| A | Alternative Solvents | Water, CO₂, ionic liquids, bio-solvents | Reduces VOC emissions, improves safety |

| N | Non-Toxic Reagents | Enzyme-based, catalytic, biodegradable | Reduces hazardous waste generation |

| C | Multi-Analyte Methods | LC-MS-MS, GC×GC, sensor arrays | Increases information per unit resource |

| E | Waste Management | Recycling, neutralization, treatment | Prevents environmental contamination |

Quantitative Greenness Assessment: Metrics for SIGNIFICANCE Evaluation

While the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic provides qualitative guidance, quantitative assessment tools are essential for objectively evaluating and comparing the environmental performance of analytical methods. Multiple metrics have been developed to score method greenness, enabling researchers to make data-driven decisions regarding sustainability improvements [13].

Green Assessment Metrics and Their Applications

The Analytical Eco-Scale employs a penalty-point system where an ideal green analysis scores 100 points, and deductions are applied for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste generation [13]. The AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric provides a comprehensive 0-1 scoring system based on all 12 GAC principles, generating a circular pictogram for visual comparison [13] [12]. For specialized evaluation of sample preparation, AGREEprep focuses specifically on extraction and pretreatment steps, while the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) offers a multi-categorical assessment with a color-coded pictogram [13].

More recently, ComplexGAPI has emerged as an advanced tool that provides a holistic evaluation of analytical procedures, and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) assesses method practicality alongside environmental considerations [13] [14]. These tools collectively enable researchers to quantify the environmental benefits achieved through implementing SIGNIFICANCE principles and identify areas for further improvement.

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Metrics for SIGNIFICANCE-Based Method Evaluation

| Assessment Tool | Scoring System | Key Evaluation Parameters | Strengths for SIGNIFICANCE Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 100-point scale (ideal=100) | Reagent hazards, energy use, waste | Simple calculation, direct numerical score |

| AGREE | 0-1 scale (1=ideal) | All 12 GAC principles | Comprehensive, visual output, incorporates SIGNIFICANCE |

| AGREEprep | 0-1 scale (1=ideal) | Sample preparation-specific parameters | Specialized for S, G, I principles evaluation |

| GAPI | Pictogram (5 categories) | Sample prep, instrumentation, waste | Visual comparison, identifies weak areas |

| NEMI | Pass/Fail pictogram | PBT, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste volume | Simple binary assessment, regulatory focus |

| ComplexGAPI | Extended pictogram | Full method lifecycle, throughput | Holistic evaluation of integrated processes |

| BAGI | Applicability score | Practical performance metrics | Balances greenness with analytical utility |

The diagram below illustrates the workflow for integrating SIGNIFICANCE principles with greenness assessment metrics in method development and optimization:

Experimental Implementation: SIGNIFICANCE in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Case Study: Green HPLC Method Development for Antihypertensive Combinations

The implementation of SIGNIFICANCE principles can be demonstrated through the development of a green reversed-phase HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of azilsartan, medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and cilnidipine in human plasma [14]. This case study exemplifies how multiple SIGNIFICANCE principles can be integrated to achieve both analytical excellence and environmental sustainability.

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation (Principles S, G):

- Minimal sample volume: 200 μL human plasma per analysis

- Micro-extraction technique: Employed 500 μL of green solvent (ethyl acetate-cyclopentyl methyl ether 1:1 v/v) for protein precipitation and extraction

- Parallel processing: 48-sample batch extraction using automated vortex mixer (5 minutes)

- Centrifugation: 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes at ambient temperature

- Evaporation: 200 μL aliquot evaporated under nitrogen stream at 40°C

- Reconstitution: 100 μL of mobile phase, vortexed for 30 seconds

Chromatographic Conditions (Principles F, I, C, A):

- Column: Monolithic C18 (100 × 4.6 mm) enabling high flow rates without backpressure issues

- Mobile phase: Green solvent mixture - ethanol:phosphate buffer (pH 3.5) (65:35, v/v)

- Flow rate: 2.0 mL/min with reduced run time of 6 minutes

- Detection: UV at 230 nm

- Temperature: 30°C

- Injection volume: 10 μL

- Autosampler temperature: 15°C

Method Validation (Principle I):

- Specificity: No interference from plasma components at retention times of analytes

- Linearity: 5-500 ng/mL for all analytes (r² > 0.999)

- Precision: Intra-day and inter-day RSD < 2%

- Accuracy: 98.5-101.2% recovery for all quality control levels

- Greenness assessment: AGREE score of 0.82, demonstrating excellent environmental performance

SIGNIFICANCE-Aligned Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Green Alternative Reagents for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Traditional Reagent | Green Alternative | SIGNIFICANCE Principle | Functional Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (HPLC) | Ethanol | Alternative solvents | Renewable source, lower toxicity, biodegradable |

| Hexane (extraction) | Cyclopentyl methyl ether | Non-use of toxic reagents | Higher boiling point, less hazardous, better safety profile |

| Trifluoroacetic acid | Phosphate buffer | Non-use of toxic reagents | Reduced environmental persistence, safer handling |

| Chlorinated solvents | Ethyl lactate | Alternative solvents | Bio-derived, biodegradable, excellent solvation power |

| Traditional C18 columns | Monolithic columns | Fast methodologies | Higher flow rates possible, shorter analysis times |

| Liquid-liquid extraction | Solid-phase microextraction | Automation & miniaturization | Minimal solvent use (often solvent-free), automation compatible |

| Conventional heaters | Microwave/ultrasound | Clean energy | Faster extraction, reduced energy consumption |

Future Perspectives: Advancing GAC Beyond SIGNIFICANCE

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic represents a current best practice framework for implementing Green Analytical Chemistry, but the field continues to evolve toward more comprehensive sustainability models. White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has emerged as an integrated approach that balances environmental criteria with analytical performance and practical utility [14]. This model employs the RGB color model where green represents environmental factors, red symbolizes analytical effectiveness, and blue denotes practical and economic considerations [14].

Future developments in GAC will likely focus on circular analytical chemistry principles that emphasize resource recovery, reagent recycling, and closed-loop systems [15]. The integration of artificial intelligence for method optimization and the development of self-optimizing analytical systems will further enhance the implementation of SIGNIFICANCE principles by identifying optimal conditions for minimal environmental impact [9]. Additionally, the adoption of green financing models specifically for analytical chemistry innovations may accelerate the transition to sustainable practices by providing dedicated resources for research, development, and implementation of green analytical methods [14].

As regulatory agencies increasingly prioritize environmental considerations in method validation and approval processes, the SIGNIFICANCE framework provides a structured pathway for laboratories to align with emerging sustainability requirements while maintaining analytical excellence [15]. This alignment ensures that the pharmaceutical and chemical industries can meet their analytical needs while contributing to broader environmental stewardship goals.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, science-based methodology that quantifies the environmental impacts of a product, process, or service across its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [16] [17]. Recognized internationally through the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, LCA provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating environmental footprints, moving beyond singular metrics to a multi-criteria perspective that includes global warming potential, water consumption, resource depletion, and eutrophication [16] [18]. In the context of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), LCA serves as a critical tool for quantifying the environmental burdens of analytical methodologies, thereby transitioning sustainability assessments from qualitative principles to data-driven decisions [9] [11].

The evolution of green chemistry principles has established a foundation for reducing the environmental impact of chemical processes. LCA operationalizes these principles by providing a robust, quantitative framework for identifying environmental "hotspots" and comparing the full life cycle impacts of alternative materials, processes, or products [17] [18]. The pharmaceutical industry, for instance, is increasingly adopting LCA to minimize the environmental footprint of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing and drug delivery systems, aligning with broader corporate sustainability goals and regulatory requirements [19] [20]. As a systems approach, LCA prevents problem-shifting, ensuring that improvements in one life cycle stage do not inadvertently create greater burdens elsewhere [21].

The Four Phases of Life Cycle Assessment

The LCA framework is structured into four interdependent phases, as defined by ISO standards 14040 and 14044: Goal and Scope Definition, Life Cycle Inventory (LCI), Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA), and Interpretation [16] [18] [21]. The following workflow illustrates the relationships between these phases and their key components:

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

This initial phase establishes the study's purpose, intended audience, and methodological boundaries [18]. It defines the functional unit, which provides a quantified reference for all input and output flows, enabling fair comparisons between alternative systems [16]. For example, an LCA of an insulating panel might use "one square meter of insulation with a defined thermal resistance" as its functional unit [16]. The scope delineates the system boundaries, determining which life cycle stages and processes are included in the assessment [18]. Common models include cradle-to-grave (full life cycle), cradle-to-gate (raw material to factory gate), and cradle-to-cradle (including recycling and reuse) [18].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The LCI phase involves the meticulous collection and calculation of input and output data for all processes within the defined system boundaries [16]. This constitutes the primary data-gathering stage, quantifying energy and raw material consumption, emissions to air, water, and soil, and waste generation for each unit process [17]. Data sources can be primary (collected directly from operations or suppliers) or secondary (from commercial, industry-average, or literature databases) [18]. The inventory results in an extensive list of all exchanges between the product system and the environment, which serves as the input for the subsequent impact assessment phase.

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The LCIA phase translates the inventory data into potential environmental impacts [16]. This involves assigning LCI results to specific impact categories and modeling these inputs into category indicator results using characterization factors [17]. The following table summarizes common impact categories assessed in an LCA:

Table 1: Key Life Cycle Impact Assessment Categories

| Impact Category | Description | Example Indicator | Common Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | Contribution to greenhouse effect from GHG emissions [16] | CO₂-equivalent [16] | kg CO₂-eq |

| Water Consumption | Total volume of water used or depleted [16] | Water use | liters or m³ |

| Resource Depletion | Consumption of non-renewable abiotic resources [16] | Antimony-equivalent | kg Sb-eq |

| Eutrophication | Excessive nutrient enrichment in water bodies [16] | Phosphate-equivalent | kg PO₄-eq |

| Human Toxicity | Potential harm to human health from toxic substances [21] | Comparative Toxic Unit | CTUh |

| Ecotoxicity | Potential harm to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [21] | Comparative Toxic Unit | CTUe |

Phase 4: Interpretation

The final phase involves evaluating the results from the LCI and LCIA to formulate conclusions, explain limitations, and provide actionable recommendations [16]. This includes hotspot analysis to identify significant issues across the life cycle, uncertainty analysis to check the reliability of the data and results, and sensitivity analysis to determine how variations in input data affect the overall outcome [18]. The findings are synthesized into a transparent report that informs strategic decision-making for improving environmental performance, such as material substitution, process optimization, or supply chain restructuring [17].

LCA in Pharmaceutical Development and Green Analytical Chemistry

The application of LCA within pharmaceutical development and Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a critical step towards achieving sustainable science. The industry is leveraging LCA to measure and reduce the environmental footprint of medicines, focusing on API synthesis, packaging, and drug delivery devices [20]. A prominent example is Process Mass Intensity (PMI), a key metric developed by the pharmaceutical sector to assess the sustainability of manufacturing processes, which is often integrated with LCA for a more comprehensive evaluation [19] [20].

Experimental Protocol: Conducting an LCA for an API Manufacturing Process

Goal and Scope Definition

- Functional Unit: Define the reference unit for the assessment, typically "per kilogram of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) with specified purity" [19].

- System Boundaries: Apply a cradle-to-gate model, encompassing raw material extraction, synthesis of precursors, all chemical transformation steps, purification, and formation of the final API up to the factory gate [18]. The use and disposal phases are excluded.

- Impact Categories: Select categories relevant to pharmaceutical manufacturing, such as Global Warming Potential, Water Consumption, and Resource Depletion [16].

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Compilation

- Process Topology: Map the synthesis route, including all reaction steps, workup, and purification stages. Account for convergent syntheses and recycle streams [19].

- Material and Energy Inputs: Quantify all input masses, including reactants, catalysts, solvents, and utilities (e.g., steam, electricity) for each step. The ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable's PMI-LCA tool can structure this data collection [19].

- Outputs and Waste: Quantify the mass of the API, co-products, and all waste streams directed to treatment (e.g., solvent recovery, incineration) [19].

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Calculation: Use an LCA software database (e.g., incorporating factors from ecoinvent or specialized pharmaceutical databases) to convert LCI data into impact category results [19].

- Hotspot Identification: Analyze the results to determine which process steps or materials contribute most significantly to the overall environmental impact.

Interpretation and Improvement Strategy

- Scenario Analysis: Model alternative scenarios to evaluate potential improvements, such as solvent substitution, catalyst recycling, or implementing a different synthetic route with a lower PMI [20].

- Decision Support: Use the results to inform R&D and process design, prioritizing changes that offer the greatest reduction in environmental impact without compromising product quality or safety [20].

Case Study: Respiratory Inhaler Propellant Transition

AstraZeneca's transition of pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) to a next-generation propellant (NGP) demonstrates LCA-driven sustainable design. The LCA would have quantified the global warming potential of the existing propellants against the new HFO-1234ze(E) propellant, which has a 99.9% lower global warming potential. This data-supported transition directly reduces the carbon footprint of respiratory care while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [20].

Advanced Integration: LCA and White Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has traditionally focused on reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods by minimizing hazardous waste, using safer solvents, and improving energy efficiency [9] [10]. LCA provides a quantitative, systemic methodology to support GAC, moving beyond simplistic solvent substitution to a holistic view of the analytical method's footprint, including instrument manufacturing, energy consumption during operation, and waste treatment [9] [11].

The emergence of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents a further evolution, advocating for a balanced approach that does not sacrifice analytical performance or practical usability for the sake of environmental benefits alone [14] [10]. WAC employs an RGB model to evaluate methods:

- Red: Analytical performance (accuracy, sensitivity, selectivity).

- Green: Environmental impact (aligned with GAC principles).

- Blue: Practical/economic aspects (cost, time, simplicity).

An ideal "white" method achieves a harmonious balance across all three dimensions [10]. The relationship between these concepts and the role of LCA is illustrated below:

LCA directly feeds into the Green component of the WAC assessment by providing robust, data-driven insights into the environmental impacts of analytical methods, such as the carbon footprint of a chromatography setup or the water consumption of a sample preparation technique [9] [11]. This integrated, quantitative approach is crucial for developing analytical methods that are not only environmentally preferable but also scientifically sound and practically viable for routine use in drug development [14] [10].

Successfully implementing LCA in research and development requires familiarity with key tools, metrics, and databases. The following table catalogs essential resources for conducting LCA studies, particularly in a chemical or pharmaceutical context.

Table 2: Key Resources for LCA Implementation in Research

| Tool / Metric Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMI-LCA Tool [19] | Software Calculator | Calculates Process Mass Intensity and LCA impacts for API synthesis. | Industry-standard for quantifying green chemistry efficiency in pharmaceutical processes. |

| Ecoinvent Database | Life Cycle Inventory Database | Provides background data on energy, materials, and chemicals. | Common source of emission factors; may lack pharmaceutical-grade material data [19]. |

| AGREE Metric [10] | Greenness Assessment Tool | Evaluates analytical methods against the 12 principles of GAC. | Complements LCA for assessing the greenness of analytical chemistry methods. |

| NEMI Label [10] | Greenness Assessment Tool | Simple pictogram indicating method greenness based on 4 criteria. | Quick visual assessment for analytical procedures. |

| BAGI Metric [10] | Practicality Assessment Tool | Assesses the practicality and applicability of analytical methods (Blue component in WAC). | Balances environmental and performance metrics with practical usability. |

| Functional Unit [16] | LCA Concept | Defines the quantified performance of the system being studied. | Critical for fair comparisons (e.g., environmental impact per kg of API, per diagnostic test). |

Life Cycle Assessment provides an indispensable, systems-based framework for rigorously evaluating and mitigating environmental impacts, making it a cornerstone of modern Green Analytical Chemistry and sustainable pharmaceutical development. By quantifying impacts across the entire value chain—from raw material extraction to end-of-life—LCA empowers researchers and drug development professionals to make informed, data-driven decisions that genuinely advance sustainability goals [16] [17]. Its integration into emerging frameworks like White Analytical Chemistry ensures that environmental progress is achieved without compromising the analytical performance or practical utility that scientific discovery and medicine development require [14] [10]. As regulatory pressures intensify and the demand for corporate transparency grows, the adoption of robust LCA methodologies will be crucial for fostering innovation, maintaining competitive advantage, and contributing to a more sustainable future for the chemical and pharmaceutical industries [16] [20].

The analytical chemistry landscape has undergone a significant paradigm shift over recent decades, moving from a singular focus on performance to embracing environmental responsibility. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a transformative approach, integrating sustainability principles directly into analytical practice by minimizing toxic solvent use, reducing energy consumption, and curtailing waste generation [22] [9]. Founded on the twelve principles of green chemistry established by Anastas and Warner, GAC provided the foundational framework for mitigating the environmental impact of analytical processes [22] [9]. However, its primary focus on ecological concerns sometimes created tensions with analytical performance and practical feasibility, revealing critical limitations in real-world laboratory applications [22].

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has subsequently emerged as a holistic, integrated framework designed to transcend these limitations. First conceptualized in 2021, WAC represents the next evolutionary stage in sustainable analytical science by simultaneously balancing environmental sustainability, analytical performance, and practical/economic considerations [10] [14]. This triadic approach ensures that methodologies are not only environmentally sound but also analytically robust and practically feasible, making WAC particularly relevant for modern laboratories where efficiency, cost, and sustainability must coexist with uncompromising data quality [22] [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, WAC provides a comprehensive toolkit for developing methods that excel across all critical dimensions rather than optimizing one at the expense of others.

The Limitations of Green Analytical Chemistry

Despite its noble intentions and significant contributions to sustainability, GAC faces several challenges in practical implementation. Understanding these limitations is crucial for appreciating the value proposition of White Analytical Chemistry.

Performance-Environment Trade-offs

A fundamental challenge in GAC implementation involves the inherent trade-offs between environmental benefits and analytical capabilities. The pursuit of greener methods can sometimes result in compromised sensitivity, precision, or accuracy—parameters essential for reliable analytical results, particularly in regulated environments like pharmaceutical quality control [22]. For instance, reducing solvent consumption through miniaturization might adversely affect detection limits, while eliminating certain toxic but highly effective reagents could diminish selectivity in complex matrices [22] [10].

Practical Feasibility Gaps

GAC principles often overlook critical practical considerations essential for routine laboratory implementation. Factors such as method cost, analysis time, operational simplicity, and equipment requirements frequently receive insufficient attention within the GAC framework [10]. A method might demonstrate excellent environmental credentials yet prove economically prohibitive or technically impractical for high-throughput environments. This limitation becomes particularly evident in resource-constrained settings or when transitioning methods from research to industrial scale [22].

Incomplete Assessment Frameworks

While GAC has developed valuable greenness assessment tools, these metrics primarily focus on environmental impact without integrating performance or practicality evaluations. Tools such as the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) and Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) provide valuable environmental assessments but offer limited insight into how greenness correlates with analytical reliability or implementation feasibility [3] [23]. This fragmented assessment approach can lead to suboptimal method selection when environmental considerations disproportionately influence decision-making [24].

White Analytical Chemistry: Fundamental Principles and Framework

White Analytical Chemistry addresses GAC's limitations through a balanced, integrated framework that reconciles environmental responsibility with analytical excellence and practical implementation.

The RGB Model

The foundational concept of WAC is the RGB model, which adapts the additive color mixing principle to analytical method evaluation [10] [14]. In this model, the three primary components—Red, Green, and Blue—are assessed independently, with "whiteness" representing the ideal balance among them.

Red Component (Analytical Performance): This dimension focuses on the fundamental analytical parameters that ensure method reliability and suitability for its intended purpose. Key criteria include accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity, robustness, linearity, and reproducibility [22] [10]. The red component answers the critical question: "Does the method produce scientifically valid and reliable data?"

Green Component (Environmental Impact): Incorporating the core principles of GAC, this dimension addresses environmental sustainability throughout the analytical workflow. It evaluates factors including energy consumption, waste generation, reagent toxicity, operator safety, and use of renewable resources [22] [10] [3]. The green component addresses: "What is the method's environmental footprint?"

Blue Component (Practical and Economic Factors): This dimension encompasses the practical considerations governing method implementation in real-world settings. It includes analysis time, cost per sample, equipment requirements, operational simplicity, scalability, and ease of automation [22] [10]. The blue component evaluates: "Can this method be practically and economically implemented in my laboratory?"

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these three components and how they combine to form "white" methods when perfectly balanced:

The Concept of "Method Whiteness"

In WAC, "whiteness" represents the optimal harmonization of the red, green, and blue dimensions rather than maximal achievement in any single dimension [22] [10]. A perfectly white method demonstrates excellent analytical performance, minimal environmental impact, and strong practical feasibility in balanced proportion. The resulting color when the three RGB components mix visually indicates how well a method satisfies these combined criteria, providing an intuitive assessment tool for researchers [10]. This integrated perspective acknowledges that a method strong in only one dimension (e.g., exceptionally green but analytically weak) may be less valuable than a method demonstrating good performance across all three domains.

Comparative Analysis: GAC vs. WAC in Analytical Practice

The transition from GAC to WAC represents more than a theoretical advancement—it fundamentally changes how analytical methods are developed, evaluated, and selected.

Table 1: Comparative Framework of GAC versus WAC

| Aspect | Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) | White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Environmental impact reduction | Balanced integration of environmental, performance, and practical factors |

| Core Philosophy | Eco-centric | Holistic and balanced |

| Key Metrics | Solvent consumption, energy use, waste generation, toxicity | RGB criteria with equal weighting to analytical performance, environmental impact, and practical feasibility |

| Assessment Approach | Standalone greenness evaluation | Integrated "whiteness" assessment |

| Method Development Priority | Minimizing environmental footprint | Optimizing the balance among sustainability, functionality, and practicality |

| Typical Trade-offs | May sacrifice analytical performance or practicality for green benefits | Explicitly addresses and balances trade-offs between competing priorities |

| Decision-Making | Environmentally-driven | Multi-criteria driven based on application context |

Practical Application: An HPLC Case Study

The practical implications of this philosophical difference become evident when comparing approaches to method improvement. Consider a traditional HPLC method consuming high volumes of acetonitrile:

A GAC approach would prioritize replacing acetonitrile with a less toxic alternative like ethanol or water, potentially compromising chromatographic resolution and increasing analysis time [22].

A WAC approach would evaluate alternative solvents not only for environmental impact but also for their effect on separation efficiency, detection sensitivity, and operational considerations like cost and system compatibility [22] [10]. The optimal solution would balance all three dimensions rather than maximizing environmental benefits alone.

This case study illustrates how WAC's balanced framework leads to more practically viable sustainable methods, particularly important in pharmaceutical quality control where regulatory compliance demands uncompromising analytical performance [22].

Assessment Tools and Metrics for WAC Implementation

The successful implementation of WAC relies on robust assessment tools that quantify performance across the three RGB dimensions. The analytical chemistry community has developed specialized metrics for each component, alongside frameworks for integrated assessment.

Table 2: Essential Assessment Tools for White Analytical Chemistry

| Tool Name | Focus Dimension | Key Metrics Assessed | Output Format | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE/AGREEprep [3] [23] | Green | All 12 GAC principles, including waste, toxicity, and energy | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | Comprehensive environmental assessment |

| NEMI [3] | Green | Persistence, toxicity, corrosiveness, waste volume | Binary pictogram | Basic environmental screening |

| RAPI [24] [23] | Red | Sensitivity, precision, accuracy, robustness, selectivity | Numerical score | Analytical performance quantification |

| BAGI [10] [23] | Blue | Cost, time, operational simplicity, equipment needs | Pictogram with blue shading | Practical feasibility assessment |

| RGB 12 [24] | Integrated (WAC) | All RGB criteria with 4 principles per dimension | RGB-colored hexagon | Holistic whiteness evaluation |

| VIGI [23] | Innovation | Sample prep, instrumentation, automation, interdisciplinary | 10-point star with violet intensity | Method innovation assessment |

The Role of Lifecycle Assessment and Greenhouse Gas Inventories

Beyond these specialized tools, WAC benefits from incorporating Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) and Greenhouse Gas Inventories (GHGI) into method development [22]. These approaches provide comprehensive environmental evaluations across the entire method lifecycle—from reagent production and instrument manufacturing to waste disposal [22] [9]. For instance, an LCA might reveal that a method using minimal solvents but requiring energy-intensive instrumentation has a larger carbon footprint than initially apparent, enabling more informed environmental decisions within the WAC framework [22].

Implementing Analytical Quality by Design

The integration of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Design of Experiments (DoE) represents a powerful approach for achieving the balanced optimization that WAC demands [22] [14]. These systematic methodologies enable researchers to understand method parameters and their interactions, facilitating the development of robust methods that simultaneously fulfill analytical, environmental, and practical requirements [22]. The data-driven nature of AQbD and DoE provides objective foundations for the trade-off decisions inherent in WAC implementation, particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis where regulatory scrutiny is high [22] [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies in WAC

Implementing WAC principles requires specific methodological approaches that balance the RGB dimensions. The following experimental workflow illustrates how WAC can be applied to analytical method development:

Case Study: Developing a Stability-Indicating HPTLC Method

A practical implementation of WAC principles can be illustrated through the development of a stability-indicating HPTLC method for simultaneous estimation of thiocolchicoside and aceclofenac [22] [14].

Experimental Protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Materials: Pharmaceutical formulations containing thiocolchicoside and aceclofenac, methanol (green solvent), HPTLC silica gel plates

- Procedure: Extract active ingredients using methanol via vortex-assisted extraction (2 minutes). Employ dilute-and-shoot methodology to minimize solvent consumption and waste generation [10].

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Stationary Phase: HPTLC silica gel 60 F254 plates

- Mobile Phase: Optimized using AQbD/DoE to achieve adequate separation while maximizing greenness through solvent selection and minimal consumption

- Development: Ascending development in twin-trough chamber (development distance: 80 mm)

- Detection: Densitometric scanning at 270 nm

Method Validation:

- Red Parameters: Assess specificity (peak purity >0.999), accuracy (recovery 98-102%), precision (RSD <2%), linearity (r² >0.998), and robustness [22] [14]

- Green Parameters: Calculate solvent consumption (<50 mL per run), waste generation (<10 mL), energy usage, and reagent toxicity

- Blue Parameters: Document analysis time (<20 minutes per sample), cost per analysis, operational simplicity, and equipment requirements