From Plant Extracts to Pharmaceuticals: The Historical Development and Modern Optimization of Extraction Freezing Methods

This article traces the historical development of extraction freezing methods from early food preservation applications to sophisticated pharmaceutical and biomedical extraction techniques.

From Plant Extracts to Pharmaceuticals: The Historical Development and Modern Optimization of Extraction Freezing Methods

Abstract

This article traces the historical development of extraction freezing methods from early food preservation applications to sophisticated pharmaceutical and biomedical extraction techniques. It explores the fundamental principles of freezing-induced cell disruption, examines methodological advancements across industries, provides troubleshooting and optimization guidelines for researchers, and presents comparative validation against alternative extraction technologies. For drug development professionals and scientists, this comprehensive review synthesizes decades of technological evolution to inform more efficient bioactive compound extraction processes while preserving thermolabile components critical to pharmaceutical efficacy.

The Origins and Fundamental Principles of Extraction Freezing Technology

The development of the extractive freezing-out method over the past two decades represents a significant advancement in sample preparation technology. This review details the method's evolution from a simple concentration technique to a sophisticated extraction principle based on the low-temperature redistribution of analytes between the liquid phase of a pre-added non-freezing hydrophilic solvent and the forming solid ice phase [1] [2]. The introduction of extractive freezing-out under centrifugal force conditions (EFC) has particularly enhanced its efficiency and broadened its application across chemical toxicological analysis, food quality control, environmental monitoring, and hydrochemical studies [1]. This whitepaper examines the historical context, fundamental principles, methodological developments, and comparative advantages of EFC over traditional sample preparation techniques, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide framed within the broader thesis of this method's historical development.

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles

Origins in Basic Freezing Techniques

The foundational concept of concentrating solutions through freezing predates modern scientific extraction methods. Early applications were primarily simple concentration by freezing, employed initially in food preservation and later adapted for basic analytical chemistry purposes [1]. These primitive methods leveraged the fundamental physical phenomenon that occurs when aqueous solutions freeze – dissolved substances are typically excluded from the growing ice crystals, leading to their concentration in the remaining liquid phase. Baker's 1967 work on trace organic contaminant concentration through freezing represents an early scientific formalization of this principle [1], establishing a crucial foundation for the development of more sophisticated extractive freezing techniques.

The transition from simple concentration to targeted extraction began with the recognition that adding specific hydrophilic solvents to aqueous systems before freezing could create a biphasic system at low temperatures. This development marked the birth of true extractive freezing-out as a distinct sample preparation methodology [2]. The seminal patents and research by Bekhterev between 2005-2015 established the theoretical and practical framework for this novel extraction principle, which is based on the low-temperature separation of target analytes through their redistribution between the liquid phase of a pre-added non-freezing hydrophilic solvent and the solid phase of ice formed during the freezing process [1].

Theoretical Basis of Extractive Freezing-Out

The extractive freezing-out method operates on several interconnected physical principles that govern the redistribution of solutes during freezing:

Phase Distribution Dynamics: As an aqueous solution containing a hydrophilic solvent freezes, target analytes partition between the solid ice phase and the remaining liquid phase based on their physicochemical properties [1]. The pre-added hydrophilic solvent remains liquid at temperatures where water freezes, creating an extraction environment for the target compounds.

Exclusion and Concentration: The formation of pure ice crystals excludes dissolved substances, effectively concentrating them in the diminishing liquid phase [1]. This phenomenon significantly enhances the extraction efficiency compared to conventional methods.

Centrifugal Enhancement: The application of centrifugal force during freezing (EFC) improves phase separation, facilitates more complete isolation of the concentrated analyte fraction, and increases the overall efficiency and reproducibility of the method [1].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Extractive Freezing Development

| Time Period | Development Stage | Key Innovations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2000 | Basic Freeze Concentration | Simple freezing for solute concentration | Food preservation, preliminary water analysis |

| 2005-2006 | Method Formalization | RF Patent #2303476: Principle of extractive freezing combined with freezing [1] | Basic extraction of organic compounds from water |

| 2014-2015 | Centrifugal Enhancement | RF Patent #2564999: EFC method under centrifugal force [1] | Improved recovery of hydrophilic organics |

| 2015-2019 | International Recognition | European Patent EP3357873, International PCT applications [1] | Standardized protocols for environmental analysis |

| 2020-Present | Advanced Applications | Implementation in regulatory methods [1] | Toxicological analysis, food quality control, environmental monitoring |

Technical Development and Methodological Advancements

Progression to Extractive Freezing-Out Under Centrifugal Force (EFC)

The most significant advancement in extractive freezing-out methodology came with the introduction of centrifugal force applications, creating the EFC technique. This development addressed key limitations of earlier freeze concentration methods, particularly regarding reproducibility and recovery efficiency [1]. The centrifugal force serves multiple functions in the enhanced protocol: it ensures constant contact between the freezing front and the concentrated solution, facilitates more complete separation of the ice phase from the extractant phase, and enables higher recovery rates of target analytes [1].

The fundamental EFC workflow involves several coordinated steps. First, a carefully selected hydrophilic solvent is added to the aqueous sample containing the target analytes. The mixture is then subjected to controlled freezing while undergoing centrifugation. During this phase, pure ice crystals form, excluding the dissolved substances, which become concentrated in the remaining liquid phase containing the hydrophilic solvent. Finally, the concentrated extract is separated from the ice matrix for subsequent analysis [1]. This process represents a significant departure from earlier freeze concentration methods that lacked the selective extraction capabilities afforded by the hydrophilic solvent system.

Comparative Methodological Advantages

Research over the past two decades has demonstrated clear advantages of EFC over traditional sample preparation techniques. In comparison to liquid-liquid extraction, EFC eliminates the need for large volumes of organic solvents, reduces emulsion formation, and provides more efficient extraction of hydrophilic compounds [1] [2]. When compared to solid-phase extraction, the method offers superior performance for difficult-to-extract polar compounds without the issues of column clogging or sorbent degradation [1]. Against headspace analysis, EFC provides broader applicability to less volatile compounds and eliminates the need for complex equilibrium calibration [1].

The environmental and practical benefits of the method are particularly noteworthy. EFC significantly reduces the consumption of hazardous organic solvents, aligning with green chemistry principles [1]. The technique also simplifies sample preparation workflows by eliminating multiple transfer steps and complex apparatus, while simultaneously providing inherent sample cleanup through the freezing process, which excludes many interfering matrix components into the ice phase [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Methods

| Parameter | Extractive Freezing-Out (EFC) | Liquid-Liquid Extraction | Solid-Phase Extraction | Headspace Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Solvent Volume | Minimal (1-5 mL) [1] | Large (50-500 mL) [1] | Moderate (10-50 mL) [1] | None |

| Extraction Time | 30-60 minutes [1] | 20-30 minutes + phase separation [1] | 30-45 minutes + conditioning [1] | 15-60 minutes equilibrium |

| Applicable Compound Polarity | Wide range, including hydrophilic [1] | Limited for hydrophilic compounds [1] | Moderate to hydrophobic preferred [1] | Volatile compounds only |

| Relative Cost per Sample | Low | High | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Matrix Effect Resistance | High (inherent cleanup) [1] | Low to Moderate | Variable | High |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Detailed EFC Methodology

The standard EFC protocol has been optimized through numerous applications across different analytical domains. For the determination of phenols in water – a benchmark application for the method – the procedure involves adding a specified volume of acetonitrile (typically 1-2 mL per 10 mL sample) to the aqueous sample [1]. The mixture is transferred to centrifuge tubes and placed in a freezing chamber at -20°C to -25°C while undergoing centrifugation at 2000-4000 × g for 20-30 minutes [1]. During this process, a clear separation occurs: the ice phase forms, excluding the phenolic compounds, which concentrate in the acetonitrile-rich liquid phase. This concentrated extract is then decanted or pipetted for direct analysis or further concentration.

For pesticide residue analysis in food matrices, such as the determination of pyrethroids in milk, the EFC method incorporates an additional low-temperature clean-up step [1]. After initial extraction, the extract undergoes a second freezing step at modified temperatures to precipitate interfering lipids and proteins, which are removed prior to the main EFC process [1]. This adaptation demonstrates the method's versatility and capability for integrated sample cleanup and concentration. The critical parameters controlling EFC efficiency include the type and volume of hydrophilic solvent, freezing rate and temperature, centrifugal force and duration, sample composition, and initial analyte concentration [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of EFC requires specific materials and reagents optimized for the technique:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Extractive Freezing-Out Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in EFC Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Solvents | Acetonitrile, DMSO, methanol of HPLC/GC grade [1] | Forms non-freezing liquid phase for analyte extraction and concentration |

| Centrifugation System | Refrigerated centrifuge capable of maintaining -20°C to -25°C [1] | Provides controlled temperature and centrifugal force for phase separation |

| Cryogenic Containers | Centrifuge tubes rated for low-temperature use [1] | Withstands thermal stress during freezing while accommodating sample volumes |

| Reference Standards | Certified analyte standards in appropriate solvents [1] | Enables method validation, calibration, and quantification of results |

| Quality Control Materials | Fortified samples, blank matrices, reference materials [1] | Ensures method accuracy, precision, and ongoing performance verification |

Diverse Field Applications

The EFC method has found successful application across multiple scientific disciplines, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness. In environmental monitoring, the technique has been implemented in standardized protocols for determining volatile phenols in drinking, surface, and waste waters, showing superior performance compared to traditional gas chromatographic methods [1]. For food quality control, EFC has been validated for pesticide determination in tomatoes and pyrethroids in milk, providing efficient extraction with minimal matrix interference [1]. The method's incorporation into chemical toxicological analysis has enabled improved detection and quantification of pharmaceutical compounds and toxins in biological matrices [1].

Regulatory acceptance of EFC is evidenced by its inclusion in methodological guidelines such as PND F 14.1:2:3:4.244-2007 for water analysis and GOST standards for pesticide determination [1]. The technique's reliability for demanding applications is further demonstrated in hydrochemical studies, where it enables precise determination of organic micropollutants at trace levels in complex aqueous matrices [1]. Recent advances have expanded EFC applications to emerging contaminant classes, including pharmaceutical residues, personal care products, and polar transformation products that challenge traditional extraction methods [1].

Development Trajectory and Emerging Trends

The future development of extractive freezing-out methodology is likely to focus on several key areas. Automation and integration with analytical instrumentation represents a natural progression, potentially through the development of dedicated EFC modules that can be directly coupled with chromatographic systems [1]. Method optimization for emerging contaminant classes, including highly polar and ionizable compounds, will expand the technique's applicability domain [1]. The exploration of alternative hydrophilic solvents with improved environmental profiles and extraction efficiencies represents another promising research direction [1].

The integration of EFC with miniaturized analytical systems and lab-on-a-chip technologies could further reduce reagent consumption and analysis time while increasing throughput [1]. Additionally, the development of predictive models for optimizing EFC parameters based on analyte physicochemical properties would enhance method development efficiency and facilitate wider adoption across different application domains [1]. The ongoing refinement of EFC protocols for complex biological matrices in pharmaceutical and clinical research represents a significant growth area, particularly for therapeutic drug monitoring and metabolomic studies [1].

Concluding Assessment

The twenty-year development of extractive freezing-out, particularly in its EFC implementation, represents a significant advancement in sample preparation technology. From its origins in basic food preservation techniques, the method has evolved into a sophisticated extraction principle with demonstrated advantages over traditional approaches. The technique's foundation in the low-temperature redistribution of analytes between liquid and solid phases provides a unique mechanism for selective concentration that has proven applicable across diverse scientific disciplines.

The historical development of extractive freezing-out reflects a broader trend in analytical chemistry toward greener, more efficient, and more selective sample preparation methods. The continued refinement and application of EFC will likely further establish its position as a valuable tool for researchers and drug development professionals facing increasingly challenging analytical requirements. As the method matures, its integration into standardized protocols across various sectors testifies to its robustness, reproducibility, and analytical performance, ensuring its place in the ongoing evolution of extraction technologies.

The study of freezing-induced cell disruption and dehydration represents a critical intersection of biophysics, cell biology, and materials science. For decades, researchers have sought to unravel the fundamental mechanisms through which freezing damages living systems, driven by both theoretical interest and pressing practical applications in cryopreservation, food science, and pharmaceutical development. The historical development of extraction freezing method research reveals an evolving understanding that has progressively shifted from macroscopic observations to molecular-level explanations. Early investigations primarily attributed freezing damage to the volumetric expansion of water upon ice formation, but contemporary research has revealed far more complex and nuanced mechanisms centered on dehydration-driven phenomena [3]. This paradigm shift has redefined our approach to preserving biological materials, leading to more effective cryopreservation strategies and refined extraction methodologies.

The extraction freezing method itself has undergone significant development over the past twenty years, emerging as a valuable technique for isolating target components via low-temperature redistribution of dissolved substances between liquid phases and forming ice crystals [4]. This technique, particularly when enhanced by centrifugal forces (extractive freezing-out under centrifugal forces, or EFC), has found applications across chemical-toxicological analysis, food quality control, and environmental monitoring [4]. Understanding the core mechanisms of freezing-induced damage is thus essential not only for mitigating injury in biological systems but also for harnessing freezing processes for analytical and industrial purposes. This review synthesizes current knowledge of these mechanisms, places them within their historical context, and provides researchers with the methodological tools to investigate these phenomena further.

The Core Mechanisms of Freezing Injury

From Volumetric Expansion to Cryosuction: A Paradigm Shift

Traditional explanations of freezing damage often emphasized the ≈9% volumetric expansion of water upon freezing as the primary disruptive force [3]. However, experimental evidence has demonstrated that most soft materials can readily accommodate this degree of expansion without significant damage [3]. The paradigm has now shifted to recognize cryosuction—the process whereby undercooled ice draws water toward itself from surrounding materials—as the principal driver of freezing damage [3]. This phenomenon occurs because ice growth in one area creates a chemical potential gradient that pulls unfrozen water from adjacent regions, leading to progressive dehydration of the surrounding matrix.

In biological systems, this process begins when extracellular ice forms first, rejecting solutes and thereby increasing the solute concentration in the remaining unfrozen extracellular fluid [5]. This creates an osmotic imbalance that draws water out of cells, leading to cell shrinkage, dehydration, and potential membrane rupture [5]. The mechanical and osmotic stresses generated during this process can disrupt cellular structures and compromise membrane integrity. The rate of cooling significantly influences the nature of this damage; slow cooling permits more extensive cellular dehydration, while rapid cooling increases the likelihood of intracellular ice formation, both of which can be lethal to cells [6] [5].

Membrane Destabilization and Phase Transitions

The plasma membrane represents a primary site of freezing injury, with dehydration-induced destabilization being a central mechanism [7]. As cells lose water during freezing, membrane lipids undergo lyotropic phase transitions, shifting from lamellar to non-lamellar arrangements such as the hexagonal-II phase [7] [8]. These structural alterations compromise the membrane's barrier function and can lead to complete membrane failure upon thawing. The propensity for these deleterious phase transitions is strongly influenced by membrane lipid composition, which explains why cold acclimation—which alters this composition—confers increased freezing tolerance [7].

Research on plant systems has demonstrated that freeze-induced dehydration can cause lamellar-to-hexagonal-II phase transitions in plasma membrane lipids [8]. This transition represents a fundamental structural reorganization that disrupts normal membrane function. Cold acclimation dramatically alters the behavior of the plasma membrane during freeze-thaw cycles, increasing tolerance to osmotic excursions and decreasing the tendency for dehydration-induced phase transitions [7]. The evidence supporting a causal relationship between increased cryostability and specific alterations in membrane lipid composition continues to grow, offering insights into natural adaptive mechanisms and potential strategies for cryopreservation.

Table 1: Primary Mechanisms of Freezing-Induced Cellular Damage

| Mechanism | Process | Consequence | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryosuction & Dehydration | Undercooled ice draws water from surrounding material/cells | Cellular dehydration, shrinkage, and osmotic stress | [3] [5] |

| Membrane Phase Transitions | Lamellar to hexagonal-II phase transitions in membrane lipids | Loss of membrane integrity and barrier function | [7] [8] |

| Intracellular Ice Formation | Ice nucleation inside cells at rapid cooling rates | Direct mechanical damage to organelles and structures | [6] [5] |

| Solute Concentration Effects | Increased electrolyte concentration in unfrozen fractions | Protein denaturation and enzyme inhibition | [6] [5] |

| Mechanical Ice Crystal Damage | Physical interaction between growing ice crystals and cells | Structural tearing and membrane rupture | [3] [5] |

Cryoinjury Pathways and the Inverse U-Shaped Survival Curve

The complex interplay between cooling rate and cell survival is captured by the "inverse U-shaped survival curve" [5]. This phenomenon reflects how different cooling rates produce different injury mechanisms. At slow cooling rates, prolonged exposure to hypertonic extracellular solutions causes extensive cellular dehydration. At rapid cooling rates, intracellular ice formation occurs, with equally lethal consequences. The optimal cooling rate represents a balance between these competing injury mechanisms and varies significantly between cell types [5].

Additional modes of cryoinjury include the "unfrozen fraction" effect, where cell survival during slow freezing correlates with extracellular solute concentration in the unfrozen fraction [5]. Mechanical interactions between ice crystals and cells entrapped between them can cause direct physical destruction, while membrane lipids may undergo topological changes and lateral phase separation at low temperatures, further compromising membrane function [5]. The recognition that dehydration drives damage through the same mechanism underlying mud cracking has provided a powerful analogy for understanding freezing injury in both biological and synthetic hydrogels [3].

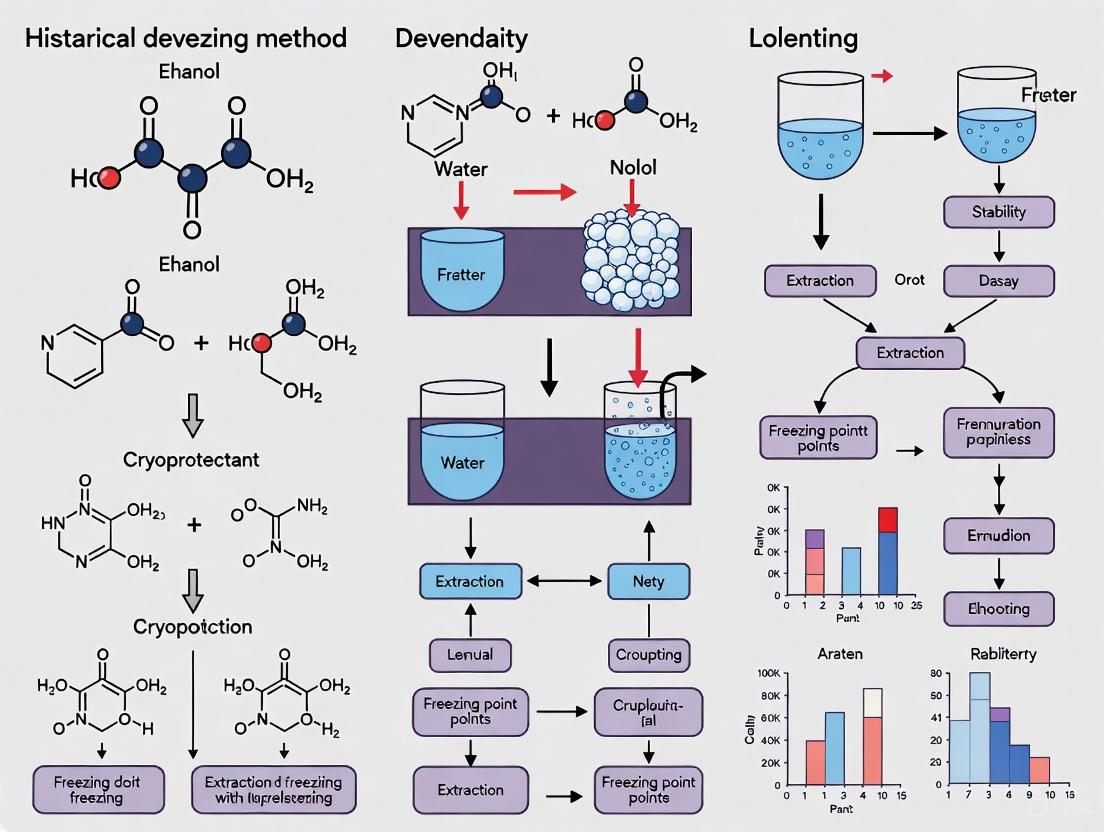

Diagram 1: Pathways of Freezing-Induced Cellular Injury. This diagram illustrates the sequential mechanisms of freezing damage, from initial ice formation to final cell death.

Experimental Methods and Protocols

Model System Preparation and Freezing Setup

Investigating freezing-induced damage requires carefully controlled model systems and precise temperature management. Hydrogels have emerged as valuable experimental models because their transparency enables direct visualization of ice crystal growth and damage propagation [3]. For experimental analysis, hydrogel-filled cells are placed on a controlled freezing stage, typically mounted on a confocal microscope to allow three-dimensional observation of the freezing process [3]. Researchers can impose either isothermal conditions or fixed temperature gradients along a defined axis, with ice growth generally initiated from the cold side of the experimental chamber.

The preparation of brittle, transparent hydrogels like poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) enables detailed observation of fracture formation during freezing [3]. These model systems have been instrumental in demonstrating that damage patterns are consistent with drying-induced fracture rather than mechanical pressure from expanding ice [3]. For biological specimens, cell cultures should be harvested during their maximum growth phase (log phase) with high viability (>90%) and at as low a passage number as possible to ensure optimal freezing outcomes [9] [10]. Adherent cells require gentle detachment using appropriate dissociation reagents before initiating freezing protocols [9].

Freezing Methodologies and Protocol Optimization

Two primary freezing methodologies dominate cryopreservation research: slow freezing and vitrification [6]. Slow freezing involves a controlled cooling rate, typically around -1°C per minute, achieved using specialized equipment like controlled-rate freezers or isopropanol-containing chambers such as "Mr. Frosty" [9] [10]. This gradual cooling permits sufficient time for cellular dehydration, reducing intracellular ice formation. In contrast, vitrification employs high concentrations of cryoprotectants and ultra-rapid cooling to transform cellular solutions into glassy, non-crystalline states, thereby avoiding ice formation entirely [6].

Protocol optimization requires careful consideration of multiple variables, including cooling rate, cryoprotectant concentration, sample volume, and cell type-specific requirements [6]. The optimal concentration of cells in cryogenic vials typically falls within a range of 1×10³ to 1×10⁶ cells/mL, as excessively low concentrations can lead to poor post-thaw viability while high concentrations may promote undesirable clumping [10]. For methodical investigation, researchers should test multiple freezing conditions to determine optimal parameters for their specific cell type or biological material.

Table 2: Standard Cell Freezing Protocol Components and Parameters

| Protocol Step | Key Parameters | Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-freeze Preparation | Harvest at log phase >80% confluency >90% viability | Ensure healthy, contamination-free cells | Perform mycoplasma testing; use gentle detachment for adherent cells [9] [10] |

| Cryoprotectant Addition | 10% DMSO or glycerol Serum-free or serum-containing formulations | Prevent ice crystal formation and stabilize membranes | DMSO facilitates entry of organic molecules; proper handling required [9] [6] |

| Packaging | Cryogenic vials Cell concentration: 1×10³-1×10⁶ cells/mL | Contain cells for storage and future use | Use internal-threaded vials to prevent contamination [10] |

| Controlled-Rate Freezing | Cooling rate: ~-1°C/minute Isopropanol chambers or controlled-rate freezers | Allow controlled dehydration and minimize intracellular ice | Slow freezing with rapid thawing is the general rule [9] [10] |

| Long-Term Storage | Liquid nitrogen vapor phase (-135°C to -196°C) | Suspend cellular metabolism indefinitely | -80°C storage leads to gradual viability loss [9] [10] |

Visualization and Analysis Techniques

Advanced visualization methods have been crucial for elucidating the mechanisms of freezing injury. Confocal microscopy combined with freezing stages allows direct observation of ice crystal growth and fracture propagation in transparent hydrogels [3]. This approach has revealed how interfacial cracks develop and propagate during freezing, providing insights into the dehydration and strain patterns that lead to structural failure.

Freeze-etch electron microscopy represents another powerful tool for examining freezing effects at the ultrastructural level [11]. This technique involves rapidly freezing samples, fracturing them under vacuum conditions, and generating platinum replicas of the fractured surfaces for examination by transmission electron microscopy [11]. The development of this methodology, particularly when combined with deep-etching and rotary replication, has enabled detailed visualization of membrane structures and intracellular components, revealing how freezing affects molecular organization.

To analyze strain fields and fracture mechanics, researchers can embed fluorescent nanoparticles in hydrogels and track their displacement during freezing [3]. This approach allows quantification of deformation patterns and identification of the specific loading modes (tensile vs. shear) that drive crack propagation. The resulting strain maps have demonstrated that shear forces, rather than simple tensile opening, predominantly drive freeze-fracture development [3].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Freezing-Induced Damage. This diagram outlines the methodological approach for studying freezing injury, from sample preparation through analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Freezing Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs) | Reduce freezing point, slow cooling rate, prevent ice crystal formation | DMSO, glycerol, ethylene glycol, proline, trehalose | [9] [6] |

| Commercial Freezing Media | Ready-to-use formulations providing optimized cryoprotectant combinations | CryoStor series, CELLBANKER series, Synth-a-Freeze | [9] [6] [10] |

| Hydrogel Model Systems | Transparent materials for visualizing ice growth and fracture dynamics | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | [3] [5] |

| Controlled-Rate Freezing Apparatus | Achieve precise cooling rates for standardized freezing protocols | "Mr. Frosty" isopropanol chambers, programmable freezing systems | [9] [10] |

| Cryogenic Storage Vials | Contain cells/media for long-term low-temperature storage | Sterile, internal-threaded vials to prevent contamination | [9] [10] |

| Detection and Visualization Tools | Assess viability, visualize ice formation, and analyze damage | Trypan Blue, fluorescent nanoparticles, confocal microscopy | [3] [9] |

Implications and Applications

Cryopreservation and Biomedical Applications

Understanding freezing-induced dehydration and membrane destabilization has profound implications for cryopreservation strategies across multiple biomedical fields. In cell therapy and regenerative medicine, effective cryopreservation enables the creation of cell banks—essential for ensuring the long-term availability of cell lines with reproducible results [10]. The principles of controlled-rate freezing and cryoprotectant optimization have directly improved the preservation of sensitive cell types including stem cells, gametes, and engineered tissues [6] [10].

The recognition that dehydration rather than volumetric expansion drives freezing damage has prompted a reevaluation of traditional cryopreservation approaches. This has led to improved cryoprotectant formulations that specifically target membrane stabilization during dehydration, such as trehalose-containing solutions that protect membrane structure at low hydrations [8]. Similarly, the development of serum-free, defined-composition freezing media addresses concerns about lot-to-lot variability and potential infectious agents associated with serum-containing formulations [10]. These advances support the translation of cell-based therapies to clinical applications where standardization and safety are paramount.

Extraction Freezing Method and Analytical Applications

The extractive freezing-out method represents a practical application of freezing principles for analytical chemistry purposes. This technique utilizes low-temperature isolation of target components via redistribution of dissolved substances between the liquid phase of a pre-added non-freezing hydrophilic solvent and the forming solid phase of ice during freezing [4]. The enhancement of this method through centrifugal forces (EFC) has enabled its successful integration into chemical-toxicological analysis, food quality control, and environmental monitoring [4].

The historical development of this methodology over the past twenty years demonstrates how fundamental research on freezing processes can yield valuable practical techniques. By understanding and exploiting the redistribution of solutes during ice formation, researchers have developed efficient extraction methods that complement or surpass traditional techniques like liquid-liquid extraction and solid-phase extraction [4]. This application exemplifies how mechanistic understanding of freezing processes can be harnessed for technological innovation beyond cryopreservation.

Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances, important challenges remain in understanding and mitigating freezing-induced damage. The scaling of cryopreservation protocols from cells to tissues and organs presents particular difficulties, as larger systems introduce complex issues of mass and heat transfer that affect cryoprotectant penetration and temperature uniformity [6]. Research continues to develop improved cryoprotectant cocktails that offer effective protection with reduced toxicity, particularly for sensitive cell types like pluripotent stem cells.

The emerging technique of lyophilization (freeze-drying) for preserving extracellular vesicles and other biological nanoparticles represents another promising application [12]. However, this process introduces additional stresses, including dehydration and ice crystal formation, that can damage vesicle integrity [12]. Research into protective excipients such as trehalose and sucrose aims to maintain the stability and functionality of these biologically important structures during preservation. Similarly, the development of ice-binding proteins and synthetic analogs offers potential for precisely controlling ice crystal growth and morphology, potentially revolutionizing cryopreservation methodologies.

As our understanding of freezing-induced dehydration and membrane destabilization continues to deepen, new opportunities will emerge for preserving biological materials, extracting valuable compounds, and managing water-solid transitions across scientific and industrial applications. The integration of mechanistic insights with practical methodologies ensures that fundamental research will continue to drive innovation in this critically important field.

For researchers and scientists in drug development, obtaining a pure and clarified plant extract is a critical first step in isolating bioactive natural products. Historically, this process was fraught with challenges, as traditional methods often failed to effectively separate delicate phytochemicals from contaminating particulates and water-soluble impurities, leading to reduced yields and compromised bioactivity [13] [14]. The development of the extractive freezing-out method in the mid-20th century represented a significant paradigm shift, offering a novel approach to this persistent problem. This technique leverages the physical phenomena of phase separation during freezing to isolate target compounds, providing a cleaner, more efficient alternative to conventional liquid-liquid extraction or solid-phase methods [4]. The period around 1974 stands as a pivotal moment in the refinement and application of this technology, embedding it within the broader context of innovation in sample preparation for chemical and biological analysis. This whitepaper details the core principles, methodologies, and quantitative benefits of this breakthrough, providing a technical guide for its application in modern research.

The Core Principle: Extractive Freezing-Out

The fundamental innovation of the extractive freezing-out method is its use of low-temperature phase changes as a separation mechanism. The process is based on the low-temperature isolation of target components via the redistribution of dissolved substances between the liquid phase of a pre-added, non-freezing hydrophilic solvent and the forming solid phase of ice during freezing [4]. When an aqueous plant extract mixture containing a water-miscible organic solvent is slowly frozen, the water component begins to crystallize into pure ice. This crystallization process simultaneously concentrates the dissolved solutes—including the desired phytochemicals and the extraction solvent—into a progressively smaller, non-frozen liquid phase. With careful control of temperature and solvent composition, this unfrozen fraction can form a distinct layer, physically separated from the solid ice matrix, which contains a highly enriched concentration of the target compounds [4]. This principle bypasses the need for harsh chemical treatments or high-temperature evaporations, which can degrade thermolabile plant metabolites.

Historical Development and the 1974 Context

The origins of freeze-based concentration trace back further, with early studies noted in the 1960s [4]. However, the conceptualization of this physical phenomenon as a reliable extraction technique for organic substances from aqueous mediums saw critical development in the decades that followed. A major advancement was the introduction of extractive freezing-out under the influence of centrifugal forces (EFC) [4]. While a precise patent from 1974 was not identified in the provided sources, the methodological framework was firmly established during this era. This period was characterized by intensive research into alternative sample preparation techniques, driven by the needs of chemical-toxicological analysis, food quality control, and environmental monitoring [4]. The pioneering work in this field laid the groundwork for later patents, such as the Russian Patent No. 2303476, which explicitly protects the "method of recovery of organic substances from aqueous media by extraction in combination with freezing" [4]. The 1970s thus represent a key inflection point where a simple physical observation was transformed into a validated analytical tool.

Quantitative Analysis: Comparing Clarification Techniques

The efficacy of the extractive freezing-out method is best demonstrated through quantitative comparison with traditional techniques. The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Extraction and Clarification Techniques

| Technique | Clarification Efficiency | Recovery Yield for Phenolics | Solvent Consumption | Processing Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extractive Freezing-Out | High [4] | High (e.g., >90% for select phenols) [4] | Low | Medium |

| Maceration | Low to Medium [14] | Variable, often medium | High [14] | Long (hours to days) [14] |

| Soxhlet Extraction | N/A (requires filtration) | High | High [14] | Long (several hours) [14] |

| Liquid-Liquid Extraction | High | High | Very High [4] | Medium |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | High | High | Medium | Short to Medium |

Table 2: Analysis of Characteristic Solvents in Extractive Freezing

| Solvent / Solution | Function in the Process | Key Property |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Hydrophilic extraction solvent | High boiling point, low freezing point, miscible with water. |

| Ethanol-Water Mixture | Extraction medium and anti-freeze | Adjustable polarity for different compound classes; prevents complete freezing. |

| Aqueous Salt Solutions | Salting-out agent | Reduces solubility of organic targets, enhancing their partitioning into the solvent phase. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Extractive Freezing-Out

The following is a detailed methodology for clarifying a plant extract, adapted from the core principles of the extractive freezing-out technique.

The diagram below illustrates the complete experimental workflow for plant extract clarification using the extractive freezing-out method.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Plant Extraction:

- Action: Begin with 100 g of dried, powdered plant material.

- Extraction: Perform a standard solvent extraction using a suitable solvent (e.g., 70% ethanol) via maceration, percolation, or reflux. A typical ratio is 1:10 plant material to solvent [14].

- Filtration: Filter the crude extract through filter paper or a Büchner funnel to remove coarse particulate matter. The resulting liquid is a turbid mixture containing the target phytochemicals, water, solvent, and fine colloidal impurities.

Solvent Addition and Mixing:

- Action: To a 100 mL aliquot of the crude filtered extract, add 20 mL of a hydrophilic solvent like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Function: This solvent acts as the non-freezing phase that will encapsulate the target compounds. It must be miscible with water but have a low freezing point.

- Mixing: Agitate the mixture thoroughly on a vortex mixer or magnetic stirrer for 2-5 minutes to ensure homogeneity.

Controlled Freezing:

- Action: Transfer the mixture to a sealed container and place it in a low-temperature freezer or bath set between -20°C and -30°C.

- Time: Allow the sample to freeze completely and remain undisturbed for 8-12 hours (overnight). The slow freezing rate is critical for efficient exclusion of solutes from the forming ice lattice.

Phase Separation and Collection:

- Action: Remove the container from the freezer. Observe the distinct separation into a solid ice phase and a concentrated, unfrozen liquid fraction.

- Collection: Decant or use a pipette to carefully collect the unfrozen liquid fraction. For enhanced separation, the EFC method performs this step under centrifugal force, which forces the denser, unfrozen fraction to collect at the bottom of the tube for easy removal [4].

- Output: This collected fraction is the clarified plant extract, highly enriched with the target bioactive compounds and significantly free from water and impurities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Extractive Freezing

| Item | Function | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Solvents (DMSO, DMF) | Non-freezing extraction phase | Serves as the receiving phase for hydrophobic plant compounds (e.g., phenols, terpenoids) during freezing. |

| Ethanol (Various Grades) | Primary extraction solvent | Used in initial maceration or percolation to dissolve bioactive compounds from plant biomass [14]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., NaCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄) | Salting-out agents | Added to the aqueous mixture to decrease the solubility of organic targets, driving them into the solvent phase. |

| Buffer Solutions (e.g., Phosphate) | pH Control | Maintains a stable pH during extraction to preserve the stability of pH-sensitive compounds like flavonoids and alkaloids. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds) | Quantitative Analytical Control | Added prior to analysis via GC-MS or LC-MS to enable precise quantification of target metabolites. |

The pioneering work on the extractive freezing-out method in the 1970s provided a robust and elegant solution to the complex problem of plant extract clarification. By harnessing the fundamental physics of phase change, it offered researchers a pathway to obtain purer, more concentrated samples of natural products with minimal thermal degradation. The principles established during this period of innovation continue to underpin modern green chemistry approaches, which seek to minimize solvent use and energy consumption [14] [4]. For today's drug development professionals, understanding these historical techniques is not merely an academic exercise. It provides a foundational perspective that can inspire novel solutions for contemporary challenges in downstream processing, the handling of complex biological mixtures, and the sustainable extraction of high-value compounds from natural sources. The 1974 breakthrough remains a testament to the power of applying simple physical principles to achieve sophisticated chemical separations.

The study of ice crystal formation within biological systems represents a critical frontier in bioscience and pharmaceutical development. The historical development of extraction and freezing methodologies reveals a consistent scientific pursuit: to control the physical phase transitions of water to preserve cellular integrity and bioactive compound functionality. Traditional freezing methods, long recognized for their detrimental effects on cellular structures, have evolved significantly. Initially, conventional freezing techniques provided basic preservation but often at the cost of significant cellular damage, leading to loss of functionality in sensitive biological materials [15] [16]. This foundational understanding spurred innovation, driving the development of advanced thermal processing methods designed to mitigate ice crystal damage through precise control of pressure and temperature parameters [17] [18].

The core challenge lies in the inherent behavior of water during phase transition. When biological materials freeze, intracellular and extracellular water forms ice crystals whose size, morphology, and distribution are dictated by freezing kinetics. The resulting mechanical forces and osmotic imbalances can compromise cell membranes and subcellular compartments, leading to irreversible damage [16]. The evolution from conventional freezing to sophisticated approaches like freeze-pressure regulated extraction and high-pressure low-temperature processing reflects a paradigm shift from mere preservation to precision engineering of biological materials at the cellular level [17] [18]. This whitepaper examines these technological progressions within the context of a broader historical framework, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for navigating the complex interplay between ice formation and cellular integrity.

Historical Development of Freezing Method Research

The scientific understanding of freezing processes in biological systems has evolved through distinct eras, each marked by technological innovations that addressed limitations of preceding methods. This historical progression demonstrates how empirical observations gradually gave way to mechanistically-driven, precision-controlled approaches.

Table: Historical Evolution of Biological Freezing Methodologies

| Era | Dominant Technology | Key Limitations | Fundamental Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Conventional Freezing (CE) [15] | Slow freezing rates producing large, damaging ice crystals; significant cellular damage; low yield of bioactive compounds [15] [16] | Basic preservation capability; established the critical link between ice crystals and cellular damage |

| Transitional | Improved Conventional Extraction (ICE) [15] | Limited control over ice crystal nucleation; required optimization of multiple parameters (thawing temperature/time) [15] | Introduction of freeze-thaw cycles to enhance extraction efficiency and compound yield from biological tissues [15] |

| Modern | Freeze-Pressure Regulated Extraction (FE) [17] | Technical complexity; requirement for specialized equipment | Combination of freezing with pressure puffing and vacuum extraction to preserve volatile compounds [17] |

| Advanced | High-Pressure Low-Temperature (HPLT) [18] | High equipment costs; complex process parameter optimization | Utilization of pressure to control ice phase transitions (e.g., Ice I to Ice III), minimizing structural damage [18] |

The initial era relied on Conventional Extraction (CE), which often involved simple steeping or soaking of homogenized biological material in water followed by physical separation. This approach was plagued by low yield and poor extract quality, primarily due to the formation of large, irregular ice crystals during associated freezing steps that severely compromised cellular structures [15]. The recognition of these limitations catalyzed the transition to Improved Conventional Extraction (ICE), which incorporated systematic freeze-thaw cycles as a preliminary step. Research demonstrated that optimizing thawing temperature and time could significantly enhance the yield of water-soluble non-starch polysaccharides from taro corm, indicating reduced damage to the cellular matrices housing these valuable compounds [15].

The modern era is characterized by the integration of pressure as a controlled variable. Freeze-Pressure Regulated Extraction (FE) combines rapid freezing to low temperatures with controlled pressure release to induce structural puffing in biological materials, followed by vacuum extraction at lower temperatures. This method, applied to aromatic herbs like Gui Zhi, proved superior in preserving thermolabile compounds and cellular structures, yielding extracts with higher content of active components like cinnamaldehyde [17]. The most advanced High-Pressure Low-Temperature (HPLT) technologies, including Pressure Shift Freezing (PSF) and Pressure-Assisted Freezing (PAF), represent the current frontier. These methods exploit phase diagrams to maintain water in a supercooled state under high pressure before initiating rapid, uniform nucleation upon pressure release. The resulting ice crystals are exceptionally small and uniform, causing minimal mechanical damage to delicate structures such as myofibrillar protein gels and effectively preserving their functional properties [18].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Ice Formation and Cellular Damage

Ice Crystallization Pathways

Ice formation within biological systems follows distinct physical pathways that fundamentally influence the resulting crystal morphology and its cellular impact. The two primary pathways are liquid-origin formation and in-situ formation [19]. Liquid-origin ice stems from the freezing of supercooled water droplets near water saturation, a process dominant in mixed-phase biological systems. This pathway often generates a high number concentration of ice particles, as the freezing process utilizes the abundant population of pre-existing water droplets [19]. In contrast, in-situ-formed ice crystallizes directly from vapor-phase water below ice saturation, typically resulting in smaller, simply-shaped crystals due to limited water vapor availability [19]. In biological tissues, which are predominantly aqueous, the liquid-origin pathway is most prevalent and damaging.

The physical process involves distinct stages: nucleation, where water molecules form initial stable crystalline embryos; crystal growth, where additional water molecules accrete onto these nuclei; and potentially recrystallization, where ice crystals undergo thermally-driven structural reorganization [16]. The specific phase of ice formed has profound implications. Under standard atmospheric pressure, ice I (with hexagonal Ih being the most common form) is the predominant crystal structure [20]. However, under high pressures (e.g., ~300 MPa), water can freeze into denser polymorphs like ice III, which occupies a smaller volume and thus causes less mechanical stress to confined biological architectures [18].

Impact on Cellular Structures

The damage inflicted by ice crystals on cellular integrity is multifaceted, arising from both mechanical and biochemical mechanisms.

Mechanical Damage: During slow freezing, ice nucleation typically begins in extracellular spaces. As these crystals grow, they sequester pure water, concentrating solutes in the remaining unfrozen fluid and creating an osmotic gradient that draws water out of cells. This causes cellular dehydration and shrinkage. Simultaneously, the expanding extracellular ice crystals physically compress and mechanically shear adjacent cells, membranes, and subcellular organelles [16]. The damage is exacerbated during temperature fluctuations, which drive recrystallization—a process where smaller ice crystals dissolve and re-deposit onto larger ones, increasing their overall size and destructive potential [16].

Biochemical Damage: The concentration of solutes in the unfrozen fraction can denature proteins, disrupt lipid membranes, and alter pH, leading to enzyme inactivation [16]. Furthermore, the compression and deformation of cellular structures can inactivate key antioxidant enzymes, promoting oxidative reactions that damage crucial cellular components like proteins and lipids [16]. Research on spermatogonial stem cells has shown that freezing stress can induce DNA damage, including double-strand breaks, compromising genetic integrity and cell function [21].

Diagram: Cascade of Cellular Damage from Ice Crystallization. This pathway illustrates how the initial physical event of ice formation triggers a sequence of mechanical and biochemical insults culminating in loss of cellular integrity.

Advanced Analytical Methods for Characterizing Ice and Cellular Integrity

Ice Crystal Characterization

Modern research employs sophisticated techniques to visualize and quantify ice crystal morphology and its relationship to cellular damage.

Cryogenic Liquid-Cell Transmission Electron Microscopy (CRYOLIC-TEM): This groundbreaking technique enables molecular-resolution imaging of ice crystallized from liquid water. By encapsulating water between amorphous carbon membranes and controlled freezing, researchers can stabilize large-area single-crystalline ice Ih films suitable for high-resolution TEM imaging, achieving a remarkable line resolution of 1.3 Å. This allows direct observation of nanoscale defects, misoriented subdomains, and gas bubble dynamics within the ice lattice [20].

Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR): LF-NMR is used to analyze water status and distribution in biological tissues during freezing and thawing. By measuring T2 relaxation times, researchers can distinguish between free water, immobilized water, and bound water, providing insights into how ice formation alters the physiological water environment within a cellular matrix [16].

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP): These techniques are employed to visualize the microstructural consequences of ice formation. SEM provides high-resolution images of the pores and fissures created by ice crystals in biological tissues, while MIP quantifies the porosity and pore size distribution, confirming how freeze-based treatments create larger pores and expanded surface areas that facilitate compound release [17].

Cellular Integrity Assessment

DNA Integrity Biosensors: A novel TdT enzyme-Endo IV-fluorescent probe biosensor has been developed for sensitive, non-invasive assessment of DNA integrity in stem cells subjected to freezing stress. This method detects 3'-hydroxyl ends at DNA breakpoints, extends them to form a polyadenine sequence, and uses a fluorescent probe with endonuclease cleavage for signal amplification. It quantifies damage through a parameter called the Mean number of DNA breakpoints (MDB), offering greater sensitivity and accuracy than traditional comet or TUNEL assays [21].

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays: Standard biological assays like trypan blue exclusion (for cell survival rate) and CCK-8 (for cell proliferation) are used to quantify the functional consequences of freezing-induced cellular damage [21].

Table: Analytical Techniques for Ice and Cellular Damage Characterization

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Metrics | Technical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRYOLIC-TEM [20] | Ice crystal structure imaging | Lattice resolution, defect identification | Molecular-resolution (1.3 Å) imaging of ice from liquid water; reveals nanoscale defects and bubbles |

| LF-NMR [16] | Water status in tissues | T2 relaxation time | Distinguishes between free, immobilized, and bound water states non-destructively |

| SEM/MIP [17] | Tissue microstructure | Pore size, surface area, porosity | Visualizes and quantifies structural damage and changes in permeability |

| TdT-Endo IV Biosensor [21] | DNA strand break detection | Mean DNA Breakpoints (MDB) | High-sensitivity, non-invasive DNA integrity assessment; more accurate than comet assay |

| CCK-8 Assay [21] | Cell viability/proliferation | Absorbance at 450nm | Simple, sensitive colorimetric method for assessing metabolic activity post-thaw |

Experimental Protocols for Freezing Method Evaluation

Freeze-Pressure Regulated Extraction (FE)

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing FE, a modern technique that enhances extraction efficiency while preserving cellular integrity and thermolabile compounds [17].

- Material Preparation: Acquire plant material (e.g., Gui Zhi young twigs). Ensure proper botanical identification and standardization.

- Freeze-Drying Pretreatment: Place the biological material in freeze-drying equipment. Process at -50°C for 10 hours to achieve complete freezing and initiate sublimation.

- Freeze-Pressure Puffing: Transfer the freeze-dried material to a pressure-regulated chamber. Maintain at -25°C and 0 MPa (atmospheric pressure) for 18 hours. This step induces structural "puffing" by creating internal voids and expanding the surface area.

- Vacuum-Assisted Extraction: Soak 100 g of the processed material in 700 mL of ultra-pure water for 30 minutes. Perform extraction by boiling at 80°C under reduced pressure (0.05 MPa) for 40 minutes. The lowered boiling point protects heat-sensitive compounds.

- Sample Recovery: Filter the extract to separate solid residues. The extract can be analyzed for active compound content, pH, zeta potential, and particle size, and assessed for pharmacological activity.

High-Pressure Low-Temperature (HPLT) Treatment for Protein Gels

This protocol details the application of HPLT technology to myofibrillar protein (MP) gels, minimizing structural damage through controlled phase transitions [18].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare myofibrillar protein gels according to standardized protocols. Cut into uniform, manageable dimensions.

- System Equilibration: Place the MP gel samples in the high-pressure vessel. Immerse in an appropriate pressure-transmitting fluid.

- Pressure Shift Freezing (PSF):

- Cooling Under Pressure: Cool the sample under high pressure (e.g., 200 MPa) to a temperature below its atmospheric freezing point but above its pressure-depressed freezing point. This achieves significant supercooling without ice nucleation.

- Rapid Pressure Release: Instantly release the pressure. This triggers rapid, uniform nucleation throughout the sample, resulting in the formation of numerous small ice crystals.

- Completion of Freezing: Transfer the sample to a conventional freezer to complete the freezing process. The ice crystals will grow but remain smaller and more uniform than those from conventional freezing.

- Pressure-Assisted Freezing (PAF):

- Freezing Under Pressure: Cool and completely freeze the sample while maintaining high pressure (e.g., 300 MPa). At this pressure, ice III, a denser polymorph, will form.

- Pressure Release and Storage: After complete freezing, release the pressure and store the sample at standard frozen storage temperatures. Note that ice III will transform back to ice I upon pressure release, which must be managed carefully.

- Quality Assessment: After thawing, analyze the gels for texture, water-holding capacity, microstructure (via SEM), and protein denaturation to evaluate the efficacy of the HPLT treatment.

Diagram: Freeze-Pressure Extraction Workflow. This protocol visualizes the sequential steps for FE, from material preparation through final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Freezing Integrity Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Amorphous Carbon (a-C) Membranes [20] | Substrate for high-resolution ice imaging; provides a smooth, inert surface for forming flat ice single crystals. | Encapsulation of liquid water for CRYOLIC-TEM to stabilize ice Ih single crystals from liquid water. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) [21] | Cryoprotective agent; penetrates cells to reduce ice crystal formation and mitigate osmotic shock during freezing. | Component of cryopreservation medium for spermatogonial stem cells (e.g., culture medium:serum:DMSO = 7:2:1). |

| Lycium barbarum Polysaccharides (LBP) [21] | Natural antioxidant; mitigates oxidative DNA damage induced by freezing stress in stem cells. | Added to cryopreservation medium at varying concentrations (0.1-4 mg/mL) to assess protective effects on DNA integrity. |

| TdT Enzyme-Endo IV-Fluorescent Probe [21] | Biosensor system for detecting DNA strand breaks; enables highly sensitive quantification of DNA damage. | Non-invasive assessment of DNA integrity in stem cell culture supernatants after freezing/thawing cycles. |

| Pressure-Transmitting Fluid [18] | Hydraulic medium for high-pressure processing; transmits pressure uniformly to biological samples. | Used in HPLT systems for Pressure Shift Freezing and Pressure-Assisted Freezing of protein gels and biological tissues. |

| LF-NMR Calibration Standards [16] | Reference materials for calibrating relaxation time measurements; ensures accurate quantification of water states. | Standardization of T2 relaxation time measurements for analyzing water status and distribution in frozen/thawed meat. |

The historical trajectory of freezing method research demonstrates a clear evolution from crude preservation techniques toward sophisticated technologies that actively control ice crystal formation to safeguard cellular integrity. This progression has been driven by a deepening understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of ice crystallization and its multifaceted impact on biological structures, enabled by advances in analytical capabilities such as CRYOLIC-TEM and sensitive molecular biosensors. The current frontier, represented by pressure-regulated and combinatorial phase-transition technologies, offers unprecedented precision in managing the physical forces at play during freezing. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advancements are not merely academic; they translate directly into enhanced viability of cellular therapeutics, improved stability of biopharmaceuticals, and higher fidelity extraction of bioactive compounds. The ongoing challenge lies in scaling these advanced methodologies and further elucidating the molecular-level interactions between ice crystals and biological macromolecules, paving the way for next-generation preservation strategies across the biomedical and pharmaceutical sectors.

The historical development of extraction freezing methods reveals a fascinating divergence in terminology and application, driven by distinct scientific and engineering needs. The core of this evolution lies in the separation of two concepts: freeze-thaw, which predominantly describes a physical, cyclical process used to disrupt structures, and cryogenic extraction, which involves the application of extremely low temperatures to preserve biological function or separate components. While both leverage the phase change of water and low temperatures, their historical pathways, fundamental principles, and end goals have shaped unique technical definitions. Understanding this terminological evolution is not merely an academic exercise; it is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the appropriate methodology, accurately interpret literature, and design effective experimental protocols. This guide traces the historical context of these methods, delineates their defining characteristics through quantitative data and experimental protocols, and provides a scientific toolkit for their application.

The term "cryogenic" itself is rooted in the science of cryobiology, coined in 1964 to mean "cold life science," which studies how low temperatures affect biological activities and architecture [22]. This field's origins can be traced back to the 18th century, but its foundational modern breakthrough was the discovery of cryoprotective agents (CPAs) like glycerol in the 1940s, which prevent lethal ice crystal formation inside cells during freezing [22]. This established the primary goal of cryogenic methods: preservation of viability and function through sophisticated thermal control and chemistry. In contrast, the freeze-thaw method is often a tool for controlled mechanical disruption. Its historical inspiration is more industrial and geological, drawing from the natural process of freeze-thaw weathering, where water enters pre-existing micro-cracks in rock, expands upon freezing, and fractures the material [23]. This fundamental difference in intent—preservation versus disruption—is the cornerstone upon which the terminology and technology of these two methods have evolved.

Defining the Core Concepts and Terminological Evolution

Freeze-Thaw Method: A Cyclical Physical Process

The freeze-thaw method is defined as a technique that utilizes the cyclical repetition of freezing and thawing phases to achieve physical separation or disintegration of a material. The core mechanism is mechanical, leveraging the ~9% volumetric expansion of water when it transitions into ice [23] [24]. This expansion generates significant pressure within confined spaces, such as micro-cracks or cellular structures, leading to progressive crack propagation, fiber-resin debonding, or cell lysis.

The terminology around this method is consistently used across disparate fields, from materials science to ecology. In materials recycling, it is explicitly called a freeze–thaw-based method for fiber–resin separation, harnessing "ice-induced expansion to disrupt the glass fiber–epoxy interface" [23]. In soil science, it is described as a freeze–thaw cycle that causes the "fragmentation and aggregation of soil mineral particles" [24]. Similarly, in ecological studies, freeze-thaw events are investigated for their role in degrading the quality of perishable cached food by causing microstructural damage through ice crystal formation [25]. The consistent thread is the use of the cycle—the repeated alternation between freezing and thawing states—as the active agent for change.

Cryogenic Extraction: Ultra-Low Temperature Preservation and Separation

Cryogenic extraction refers to processes that employ extremely low temperatures, typically at the boiling point of liquid nitrogen (-196°C or -321°F), to fundamentally slow or halt biochemical and metabolic processes. The primary goal is preservation and stabilization, not mechanical destruction. The defining terminology, cryopreservation, is "a transformative technology that allows for the long-term storage of biological materials by cooling them to extremely low temperatures at which metabolic and biochemical processes are effectively slowed or halted" [22].

The evolution of this term is inextricably linked to the development of cryoprotective agents (CPAs) and advanced cooling techniques. The discovery that substances like glycerol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) could protect cells from intra-cellular ice formation during freezing and thawing marked the birth of modern cryogenic methods [22]. This led to techniques like vitrification, an ultra-rapid cooling process that solidifies water into a glass-like state without forming crystalline ice [22]. Consequently, the terminology of cryogenic extraction is dominated by concepts of viability, stability, and functional preservation post-thaw, setting it apart from the disruptive intent of freeze-thaw cycles.

Table 1: Comparative Definitions and Historical Context of Freeze-Thaw and Cryogenic Methods

| Aspect | Freeze-Thaw Method | Cryogenic Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | A cyclical process using water-ice phase change for mechanical disruption. | A preservation technique using ultra-low temperatures to halt biochemical activity. |

| Primary Mechanism | Mechanical stress from ~9% volumetric expansion of water upon freezing [23] [24]. | Kinetic suppression of molecular motion and metabolic processes [22]. |

| Historical Inspiration | Geological freeze-thaw weathering of rocks [23]. | Observations of biological material tolerance to cold (e.g., 18th-century sperm studies) [22]. |

| Key Historical Milestone | Application as a controlled physical process in materials and environmental science. | Discovery of cryoprotectants (glycerol, DMSO) in the mid-20th century [22]. |

| Primary Objective | Separation, fragmentation, or degradation of a structure. | Long-term storage with retention of viability and functionality. |

Quantitative Comparison and Methodological Parameters

The operational divergence between freeze-thaw and cryogenic methods is quantitatively evident in their typical process parameters. The following table summarizes key variables that define their respective experimental domains.

Table 2: Quantitative Operational Parameters for Freeze-Thaw and Cryogenic Methods

| Parameter | Freeze-Thaw Method | Cryogenic Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature Range | 0°C to -20°C (common in experiments) [25] [24]. | -80°C (mechanical freezers) to -196°C (liquid nitrogen) [22]. |

| Number of Cycles | Multiple cycles are the norm (e.g., 3 to 100+ cycles) [23] [24]. | Typically a single, controlled freeze and thaw event. |

| Cycle Duration | Relatively short (e.g., 8-hour cycles: 4h freeze / 4h thaw) [24]. | Long-term storage, ranging from days to decades. |

| Cooling Rate | Often uncontrolled, "slow freezing" in standard freezers. | Precisely controlled; can be slow (~1°C/min) or ultra-rapid (vitrification) [22]. |

| Critical Additives | Often just water (no additives) to facilitate expansion. | Essential use of Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs) like DMSO, glycerol [22]. |

| Key Outcome Metric | Separation efficiency, crack volume increase, particle size change, mass loss [23] [25]. | Post-thaw viability, survival rate, functional retention (e.g., >96% properties retained [23]). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate the practical application of these parameters, below are generalized experimental protocols derived from the search results.

Freeze-Thaw Protocol for Fiber-Resin Separation (Materials Science) This protocol is adapted from research on recycling wind turbine blades [23].

- Sample Preparation: Cut the composite material (e.g., glass fiber-reinforced epoxy, GRE) into standardized specimens.

- Water Saturation: Vacuum-saturate the specimens with water to ensure ingress into pre-existing micro-cracks and voids.

- Freezing Phase: Place samples in a programmable freezer and lower the temperature to -20°C. Maintain for 4 hours to ensure complete freezing throughout the sample.

- Thawing Phase: Raise the temperature to +20°C. Maintain for 4 hours to ensure complete thawing.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for the desired number of cycles (e.g., 100 cycles). The system is often closed, with no additional water replenishment.

- Analysis: Evaluate outcomes via:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): To visualize interface separation and crack propagation.

- Micro-CT Imaging: To quantify crack volume increase (e.g., ~65%) and connected porosity (e.g., ~32% rise).

- Weight Change Analysis: To monitor progressive mass loss due to epoxy removal.

- Mechanical Testing: To assess retention of original properties in extracted fibers (e.g., up to 96%).

Cryogenic Protocol for Cell Preservation (Biosciences) This protocol synthesizes principles from cryopreservation reviews [22].

- Harvesting and Preparation: Harvest the target biological material (e.g., cells, tissues) in the log phase of growth.

- CPA Addition and Equilibration: Gently mix the cells with a pre-cooled cryopreservation medium containing a suitable CPA (e.g., 10% DMSO). Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes to allow CPA penetration.

- Controlled-Rate Freezing:

- Transfer the cell suspension to cryogenic vials.

- Place vials in a controlled-rate freezer or a specialized freezing container ("Mr. Frosty") that provides an approximate cooling rate of -1°C per minute.

- Cool the samples to a temperature between -40°C and -80°C. This slow cooling facilitates dehydration, minimizing lethal intracellular ice formation.

- Long-Term Storage: Quickly transfer the frozen vials to a long-term storage vessel, such as a liquid nitrogen dewar, maintaining a temperature at or below -135°C.

- Thawing and CPA Removal:

- Rapidly thaw the vial in a 37°C water bath with gentle agitation.

- Immediately upon thawing, dilute the cell suspension with a culture medium to reduce the CPA concentration.

- Centrifuge to remove the CPA-containing medium and resuspend the cells in fresh growth medium for downstream application.

- Analysis: Evaluate outcomes via:

- Viability Staining: Using trypan blue exclusion or flow cytometry with propidium iodide.

- Functional Assays: Assessing metabolic activity (e.g., MTT assay), growth potential, or cell-specific functions.

Visualizing Methodological Pathways and Workflows

The fundamental principles and experimental workflows of these two methods can be visually distilled into the following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the correct materials is paramount to the success of either method. The following table details key reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Freeze-Thaw and Cryogenic Protocols

| Item Name | Function / Principle of Action | Primary Method |

|---|---|---|

| Programmable Freeze-Thaw Chamber | Precisely controls temperature cycles and duration according to a set protocol, ensuring experimental reproducibility [23] [24]. | Freeze-Thaw |

| Deionized Water | The primary agent for mechanical disruption; its phase change and expansion generate the stresses that separate materials. | Freeze-Thaw |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A penetrating cryoprotectant; reduces ice crystal formation by hydrogen bonding with water molecules and depresses the freezing point [22]. | Cryogenic |

| Glycerol | A penetrating cryoprotectant; protects cells from freezing injury by stabilizing membranes and promoting vitrification. | Cryogenic |

| Controlled-Rate Freezer | Provides a slow, linear cooling rate (e.g., -1°C/min), which is critical for cell dehydration and survival during cryopreservation [22]. | Cryogenic |

| Liquid Nitrogen Dewar | Provides long-term storage at -196°C, effectively halting all biochemical activity and ensuring sample stability for years [22]. | Cryogenic |

| Sucrose / Trehalose | Non-penetrating cryoprotectants; act as osmotic buffers and help stabilize cell membranes during freezing and thawing. | Cryogenic |

The evolution of terminology distinguishing freeze-thaw from cryogenic extraction methods is a direct result of their divergent historical applications and fundamental objectives. The freeze-thaw method emerged from physical principles of geological weathering, maturing into a controlled technique for mechanical disintegration where the cyclical application of phase-change energy is the key feature. In contrast, cryogenic extraction grew from biological observations and the critical discovery of cryoprotectants, evolving into a sophisticated science of biostasis and preservation at ultra-low temperatures. For the modern researcher, this distinction is operational. Selecting a freeze-thaw protocol implies a goal of separation, fragmentation, or controlled degradation. Opting for a cryogenic protocol demands a focus on viability, functionality, and long-term stability, necessitating a complex interplay of cooling kinetics and protective chemistry. As both fields advance—with freeze-thaw being refined for new materials recycling and cryogenics pushing the boundaries of complex tissue and organ preservation—their clearly defined identities will continue to guide scientific progress and innovation.

Methodological Evolution and Cross-Industry Applications of Freezing Extraction

The historical development of extraction and preservation technologies is marked by a significant paradigm shift: the transition from simple, uncontrolled freeze-thaw cycles to sophisticated controlled-rate systems. Initially, freezing was often an uncontrolled process, achieved by simply placing samples in ultra-low temperature environments like -80°C or -140°C mechanical freezers. While sometimes effective, these "dump" methods were characterized by unpredictable cooling rates, leading to inconsistencies in sample quality and viability [26]. The core challenge with such simple methods is their inherent variability, which can result in ice crystal formation, cryoconcentration, and cellular damage, ultimately compromising the integrity of sensitive biological materials [27].

The growing demand for reliability and reproducibility in fields like biopharmaceuticals, cell therapy, and fertility preservation drove the innovation of Controlled-Rate Freezers (CRFs). These systems precisely manage the cooling process through programmable, step-wise temperature reduction [28]. This evolution from a simple, passive technique to an active, controlled process represents a critical advancement in cryopreservation, enabling the safe, long-term storage of high-value biological substances. The development of these standardized protocols is not merely a technical improvement but a fundamental requirement for the advancement of modern biotechnology and regenerative medicine, ensuring that biological products maintain their therapeutic efficacy and functional characteristics from development through to clinical application [29] [30].

Fundamental Principles: Why Control the Freezing Rate?

The physical and chemical stresses imposed on a biological sample during freezing are profound. Without precise control, these stresses can lead to irreversible damage. The primary mechanisms of damage during freezing are cryoconcentration and intracellular ice formation (IIF), and the freezing rate is the critical determinant of which mechanism predominates.