From Prescriptive Checklists to Lifecycle Management: The Evolution of Analytical Method Validation Protocols

This article traces the transformative journey of analytical method validation from its origins in prescriptive checklists to the modern, science- and risk-based lifecycle approach.

From Prescriptive Checklists to Lifecycle Management: The Evolution of Analytical Method Validation Protocols

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of analytical method validation from its origins in prescriptive checklists to the modern, science- and risk-based lifecycle approach. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational regulatory principles, details contemporary methodological applications, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and examines rigorous validation and comparative strategies. By synthesizing historical context with current trends like AQbD, AI, and real-time monitoring, the article provides a comprehensive resource for navigating the past, present, and future of ensuring data quality and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical analysis.

The Roots of Reliability: Tracing the Origins and Regulatory Foundations of Method Validation

Before the establishment of global standards, analytical method validation existed as a fragmented landscape of in-house practices and company-specific standards. Pharmaceutical manufacturers operated with individualized approaches to demonstrating method suitability, creating a patchwork of technical requirements that complicated collaboration, technology transfer, and regulatory oversight. The absence of harmonized guidelines meant that methods developed in one organization often required significant rework when transferred to another facility, impeding efficiency and potentially compromising product quality consistency across regions. This case study explores the historical journey from these disparate internal standards to the coordinated global harmonization efforts that define modern pharmaceutical analysis, tracing the critical events, technological advancements, and regulatory developments that propelled this transformation.

The Early Drivers: Tragedy and Regulatory Response

The transition from in-house standards to formalized validation requirements was catalyzed by tragic events and subsequent regulatory interventions. A pivotal case was the 1971 Devonport incident, where contaminated intravenous solutions led to patient fatalities, highlighting critical gaps in sterilization process controls [1]. This tragedy refocused the entire pharmaceutical industry on the fundamental importance of manufacturing process safety and reliability, creating the imperative for more rigorous validation approaches [1].

The regulatory response emerged through key publications and requirements:

- The first UK "Orange Guide" (1971) established early Good Manufacturing Practice standards [1]

- US GMPs (21 CFR Parts 210 and 211) formalized validation requirements in 1978, with validation becoming a central term in 1983 [1]

- The 1983 FDA guide to inspection of computerized systems marked early recognition of automated system validation needs [1]

A landmark legal case, United States v. Barr Laboratories, Inc. (1993), definitively established that process validation was not merely guidance but a requirement under GMP regulations, settling industry disputes and reinforcing regulatory authority [1].

Evolution of Key Validation Parameters and Protocols

Foundational Analytical Performance Characteristics

Early validation practices focused on establishing core parameters that guaranteed method reliability, many of which remain fundamental to modern protocols. These parameters evolved from internal company requirements to standardized characteristics recognized across the industry [2].

Table 1: Core Analytical Performance Characteristics in Early Validation Practices

| Parameter | Technical Definition | Early Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between accepted reference value and value found | Drug substance: comparison to standard reference material; Drug product: analysis of synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities; Minimum 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels [2] |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between individual test results from repeated analyses | Repeatability: Same conditions, short time interval, 9 determinations over specified range; Intermediate precision: Different days, analysts, equipment; Reproducibility: Between laboratories [2] |

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte accurately in presence of expected components | Resolution of closely eluted compounds; Peak purity tests via photodiode-array or mass spectrometry; Spiking with impurities/excipients [2] |

| Linearity & Range | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration | Minimum of 5 concentration levels covering specified range; Documentation of calibration curve equation, coefficient of determination (r²), and residuals [2] |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration detectable (LOD) and quantifiable (LOQ) | Signal-to-noise ratios (3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ); Calculation via LOD/LOQ = K(SD/S) where K=3 for LOD, 10 for LOQ [2] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations | Deliberate variations in method parameters (pH, mobile phase composition, columns); Typically evaluated during method development [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Early validation practices relied on fundamental analytical tools and reagents that formed the backbone of method development and verification protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Early Analytical Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Establish accuracy and calibration curves | USP reference materials; Qualified impurity standards; System suitability verification [2] |

| Chromatographic Materials | Separation mechanism for specificity assessment | HPLC/UHPLC columns; Various stationary phases; Mobile phase buffers and modifiers [4] [2] |

| Detection Systems | Specificity and peak purity verification | Photodiode-array detectors; Mass spectrometry systems; Orthogonal detection confirmation [2] |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Extraction, dilution, and derivative formation | Protein precipitation agents; Derivatization reagents; Extraction solvents and solid-phase materials [5] |

The Path to Global Harmonization

International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Initiatives

The formation of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) marked a turning point in creating unified global validation standards. Between 2005 and 2009, ICH produced a series of quality guidelines that fundamentally reshaped pharmaceutical validation [1]:

- ICH Q8 Pharmaceutical Development (2005) introduced Quality by Design (QbD) principles [1]

- ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management (2005) formalized risk-based approaches [1]

- ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System (2008) established comprehensive quality systems [1]

These guidelines emphasized science-based approaches and risk management, moving beyond prescriptive requirements to more flexible, knowledge-driven methodologies [1]. The harmonization of terminology and requirements through ICH Q2 (Validation of Analytical Procedures) created a common language and technical framework that transcended regional regulatory differences [5] [3].

Industry Collaboration and Standards Development

Parallel to regulatory developments, industry professionals established collaborative frameworks to address emerging challenges:

- GAMP (Good Automated Manufacturing Practice) Community of Practice formed in response to FDA concerns about computer system validation [1]

- ASTM E2500 (2007) introduced risk-based approaches to qualification of manufacturing systems [1]

- USP general chapters (<1224>, <1225>, <1226>) provided standardized approaches for method transfer, validation, and verification [3]

These initiatives represented a shift from isolated company standards to collaborative knowledge sharing and consensus-based best practices across the industry [1].

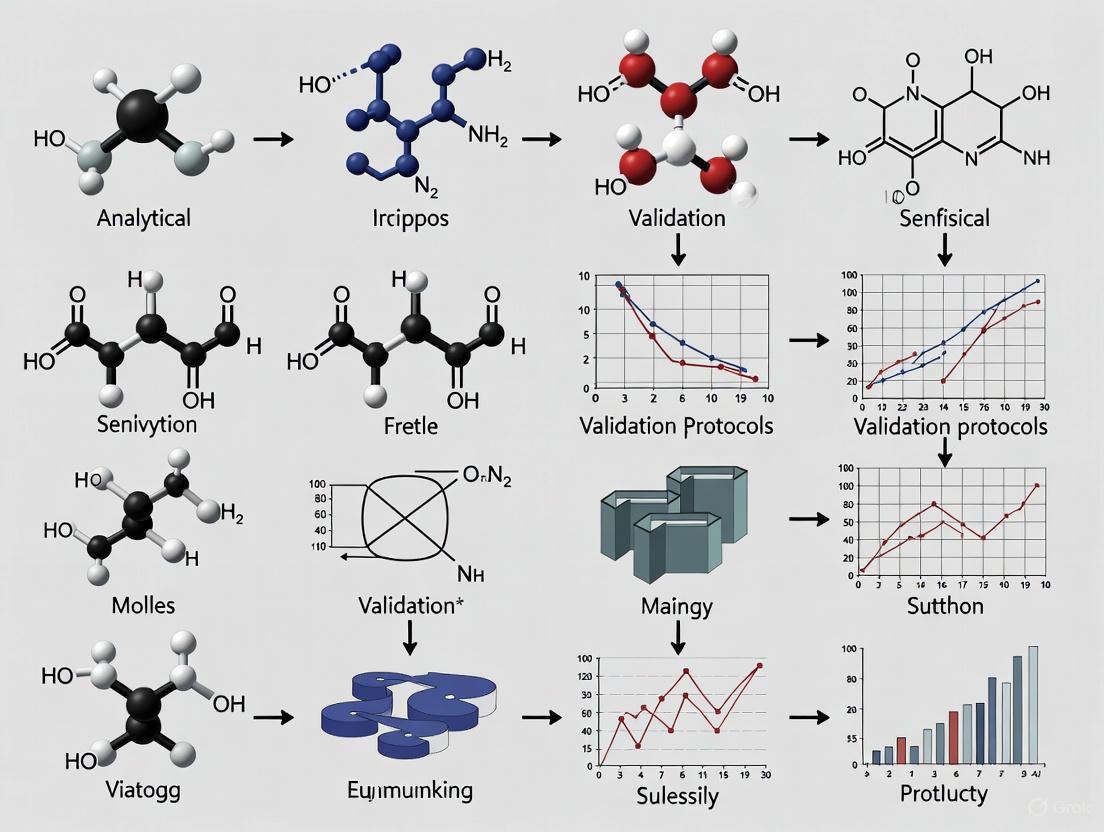

Method Validation Evolution Pathway

The transition from early practices to harmonized approaches follows a clear evolutionary pathway, visualized below:

Comparative Analysis: Early Practices vs. Harmonized Approaches

The transformation from in-house standards to globally harmonized approaches represents fundamental shifts in philosophy, methodology, and technical requirements.

Table 3: Evolution from Early Practices to Harmonized Approaches

| Aspect | Early Practices (Pre-Harmonization) | Harmonized Framework (Post-ICH) |

|---|---|---|

| Standardization | Company-specific protocols; In-house standards | Globally harmonized guidelines (ICH Q2); Unified terminology |

| Regulatory Alignment | Variable interpretations; Regional differences | Consistent expectations across FDA, EMA, and other agencies |

| Methodology | Fixed validation batches; Limited statistical basis | Risk-based approaches; Lifecycle management; Design of Experiments |

| Documentation | Varied formats and rigor | Standardized validation protocols and summary reports |

| Technology Transfer | Difficult, requiring significant revalidation | Streamlined via formal transfer protocols (USP <1224>) |

| Focus | Primarily on compliance and documentation | Science-based, patient-focused, with quality risk management |

The journey from fragmented in-house standards to global harmonization has fundamentally transformed pharmaceutical analytical method validation. While early practices were characterized by inconsistency and variable rigor, they established the foundational technical parameters that remain relevant today. The harmonization movement, driven by tragic quality failures, regulatory response, and industry collaboration, has created a more robust, science-based framework that prioritizes patient safety and product quality.

The legacy of early validation practices endures in the continued emphasis on method reliability, analytical accuracy, and technical rigor, even as the framework has evolved toward lifecycle management, risk-based approaches, and global standardization. This historical progression demonstrates how quality systems mature through the integration of technical knowledge, regulatory experience, and collaborative improvement—a process that continues today with emerging trends in real-time release testing, advanced analytics, and continuous process verification [4]. Understanding this evolution provides valuable context for contemporary validation challenges and opportunities for further advancement in pharmaceutical quality assurance.

Prior to the establishment of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the global pharmaceutical industry faced a complex and fragmented regulatory environment. Requirements for drug development and registration diverged significantly across regions, leading to redundant testing, unnecessary animal studies, and substantial delays in making new medicines available to patients [6]. This lack of harmonization resulted in inefficient use of resources and complicated international trade in pharmaceuticals. The European Union had begun its own harmonization efforts in the 1980s, but a broader international initiative was clearly needed [7]. It was against this backdrop that regulatory authorities and industry representatives from Europe, Japan, and the United States came together to create ICH in April 1990, with the inaugural meeting held in Brussels [7] [6]. The fundamental mission of this new council was to promote public health through the development of harmonized technical guidelines and requirements for pharmaceutical product registration, thereby achieving greater efficiency while maintaining rigorous safeguards for quality, safety, and efficacy [7].

The ICH framework organized its work into four primary categories: Quality (Q series), Safety (S series), Efficacy (E series), and Multidisciplinary (M series) guidelines [7]. The Quality guidelines, particularly those addressing analytical procedure validation, would become some of the most impactful and enduring standards developed by the organization. The inception of ICH marked the beginning of a new era of international cooperation in pharmaceutical regulation, creating a structured process for building consensus among regulators and industry experts that would ultimately produce the gold standard for analytical method validation: the ICH Q2(R1) guideline.

The Genesis of ICH Q2(R1): Forging a Unified Standard

The development of ICH Q2(R1), titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," represented a significant achievement in international regulatory harmonization. This guideline did not emerge in a vacuum; it was the culmination of a deliberate, multi-step consensus-building process characteristic of ICH's approach [7]. The journey to a harmonized guideline began with the identification of a need for consistent standards in analytical method validation, followed by the creation of a concept paper and business plan outlining the objectives for harmonization. An Expert Working Group (EWG) comprising regulatory and industry scientists from the founding ICH regions was then formed to develop the technical content [7].

The initial version of the quality guideline on analytical validation, ICH Q2A, was approved in 1993 (ICH Q2A, 1994). It defined key validation parameters such as specificity, accuracy, precision, detection limit, quantitation limit, linearity, and range [8]. This was subsequently complemented by ICH Q2B, which provided further guidance on methodology. In a pivotal move to streamline and consolidate these standards, the ICH unified Q2A and Q2B into a single comprehensive guideline—Q2(R1)—in November 2005 [8]. This revision provided a more cohesive and detailed framework, establishing consistent definitions and validation methodologies that could be applied across the pharmaceutical industry for both chemical and biological products [9]. The guideline was specifically designed for analytical procedures used in the release and stability testing of commercial drug substances and products, providing a common language and set of expectations for regulators and manufacturers alike [10].

Table 1: The Stepwise Development of ICH Q2(R1)

| Step | Document | Approval Date | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ICH Q2A | 1993 | Defined core validation parameters for analytical procedures. |

| Step 2 | ICH Q2B | 1996 | Provided further methodological details on validation. |

| Unification | ICH Q2(R1) | November 2005 | Consolidated Q2A and Q2B into a single, definitive guideline. |

Core Principles and Validation Parameters of ICH Q2(R1)

ICH Q2(R1) established a foundational framework for validating analytical procedures by defining a set of core performance characteristics that must be demonstrated to prove a method is suitable for its intended purpose [8]. The guideline provides clear definitions and methodological approaches for each parameter, ensuring that the term "validation" carries a consistent meaning across international borders. These parameters are not applied uniformly to all methods; rather, the specific validation requirements depend on the type of analytical procedure (e.g., identification, testing for impurities, assay). The following core principles form the bedrock of the Q2(R1) standard [2]:

- Specificity: The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components. This is typically demonstrated by resolving the analyte from closely eluting compounds in chromatographic methods, often supported by peak purity assessment using techniques like photodiode-array (PDA) or mass spectrometry (MS) detection [2].

- Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between a test result and the true value or an accepted reference value. For drug substances, accuracy is established by application of the analytical procedure to an analyte of known purity or by comparison to a well-characterized method. For drug products, it is demonstrated by spiking known amounts of the analyte into the sample matrix (placebo) and determining recovery [2].

- Precision: Expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions. Precision is investigated at three levels: repeatability (intra-assay precision under the same operating conditions), intermediate precision (variation within a laboratory on different days, with different analysts, or different equipment), and reproducibility (precision between different laboratories) [2].

- Detection Limit (LOD) and Quantitation Limit (LOQ): The LOD is the lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated, under the stated experimental conditions. The LOQ is the lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy. ICH Q2(R1) acknowledges that these can be determined based on visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio (typically 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ), or a calculation based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [2].

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a given range. It is typically established by evaluating a minimum of five concentrations and is reported along with the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line [2].

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the analytical procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity. The guideline specifies minimum ranges relative to the intended application of the method (e.g., for assay of a drug substance, the range is typically 80-120% of the test concentration) [2].

- Robustness: A measure of the analytical procedure's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters (such as pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, or flow rate in HPLC) and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage. While ICH Q2(R1) does not mandate a specific methodology for robustness, it is expected to be studied during method development [2].

Table 2: ICH Q2(R1) Validation Parameters and Methodological Requirements

| Validation Parameter | Key Definition | Typical Experimental Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents. | Chromatographic resolution; Peak purity via PDA or MS. |

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between test result and true value. | Spike/recovery experiments; Comparison to a reference method. |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. | Minimum 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels (repeatability). |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration. | Minimum of 5 concentration levels. |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity. | Defined based on the intended application of the method (e.g., 80-120% for assay). |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration that can be detected/quantitated. | Signal-to-noise (3:1 & 10:1) or statistical calculation (e.g., LOD=3.3σ/S). |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate procedural variations. | Experimental design testing variations in key method parameters. |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing the Q2(R1) Framework

The successful implementation of ICH Q2(R1) requires carefully designed experimental protocols to generate the necessary data to demonstrate each validation characteristic. The following sections detail the standard methodologies employed by scientists to validate an analytical procedure, such as a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method for a drug substance or product.

Protocol for Accuracy and Precision

Objective: To demonstrate that the method yields results that are both correct (accurate) and reproducible (precise). Materials: Drug substance standard, placebo matrix (for drug product), appropriate solvents and reagents, volumetric glassware, and HPLC system. Procedure:

- For a drug product, prepare a placebo mixture excluding the active ingredient.

- Prepare a minimum of nine samples over a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration), with three replicates at each level. For repeatability, six replicates at 100% of the test concentration may also be acceptable [2].

- Analyze each sample according to the proposed method.

- For Accuracy: Calculate the percent recovery of the known, added amount for each sample. The mean recovery should be within predefined acceptance criteria (e.g., 98-102%).

- For Precision (Repeatability): Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD%) of the results for the replicates at each concentration level. The RSD should meet predefined criteria, which are often tighter for the 100% level.

- For Intermediate Precision: Have a second analyst repeat the entire procedure on a different day, using a different HPLC system and freshly prepared standards and reagents. Compare the results from both analysts statistically (e.g., using a Student's t-test) to ensure no significant difference exists [2].

Protocol for Specificity

Objective: To prove the method can distinguish and quantify the analyte in the presence of other components. Materials: Drug substance standard, known impurities/degradation products (if available), placebo matrix, forced degradation samples (e.g., exposed to heat, light, acid, base, oxidation). Procedure:

- Inject a blank (solvent) and the placebo preparation to demonstrate no interference at the retention time of the analyte.

- Inject the analyte standard to document its retention time and peak characteristics.

- Inject samples containing the analyte spiked with all available impurities and degradation products.

- Demonstrate that the analyte peak is baseline-resolved from all other peaks, with a resolution factor (Rs) typically greater than 1.5 [2].

- Use peak purity assessment tools (e.g., PDA or MS) to confirm that the analyte peak is homogeneous and not co-eluting with any interferent.

Protocol for Linearity and Range

Objective: To establish that the method provides a proportional response to analyte concentration and to define the working range. Materials: Drug substance standard, volumetric glassware. Procedure:

- Prepare a minimum of five standard solutions spanning the claimed range of the procedure (e.g., 50%, 80%, 100%, 120%, 150% for an impurity method).

- Analyze each standard solution in triplicate.

- Plot the mean response against the concentration.

- Perform linear regression analysis on the data. Report the correlation coefficient (r), coefficient of determination (r²), y-intercept, and slope of the regression line.

- The range is validated by demonstrating that the method meets the acceptance criteria for accuracy, precision, and linearity across the entire interval.

Diagram: ICH Q2(R1) Analytical Method Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the typical sequence for validating an analytical procedure, beginning with specificity assessment and progressing through the core validation parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The experimental protocols mandated by ICH Q2(R1) rely on a set of essential research reagents and materials to ensure the validity and reliability of the data generated. The following table details these key items and their critical functions within the validation framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for ICH Q2(R1) Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Characterized Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for identity, purity, and potency; essential for preparing calibration standards for linearity, accuracy, and precision studies. |

| Placebo Matrix | For drug product methods, this mixture of excipients without the active ingredient is crucial for demonstrating specificity and for conducting spike/recovery experiments to prove accuracy. |

| Known Impurities and Degradation Products | Used in specificity experiments to demonstrate resolution from the main analyte and to validate impurity methods. When unavailable, forced degradation studies become more critical. |

| High-Purity Solvents and Reagents | Essential for preparing mobile phases, standard and sample solutions; ensures no interference, maintains system performance, and guarantees the reliability of the validation data. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the drug substance or product stressed under various conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) are used to demonstrate the stability-inducing capability and specificity of the method. |

| Volumetric Glassware/Calibrated Balances | Foundational for ensuring the accuracy of all solution preparations, dilutions, and weighings, which directly impacts the reliability of all validation parameters. |

The introduction of ICH Q2(R1) marked a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical analysis, establishing a unified, science-based standard for demonstrating the reliability of analytical methods. By harmonizing the definitions and methodologies for key validation parameters, it provided a common technical language that facilitated global drug development and registration [6]. This guideline became the undisputed international gold standard, ensuring that data generated in one part of the world could be trusted by regulators in another, thereby eliminating unnecessary repetition of studies and accelerating the availability of medicines to patients. The robustness and clarity of the Q2(R1) framework have ensured its longevity, remaining the cornerstone of analytical quality control for nearly two decades after its unification in 2005.

The legacy of ICH Q2(R1) extends beyond its direct application. It laid the essential foundation upon which subsequent guidelines, such as the recently adopted ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 on Analytical Procedure Development, are built [9]. These new guidelines introduce a more modern, lifecycle approach to method development and validation, incorporating Quality by Design (QbD) principles and enhanced risk management. However, they do not replace the core parameters established by Q2(R1); rather, they augment and contextualize them within a more comprehensive framework [9]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of ICH Q2(R1) remains indispensable for any scientist or regulator involved in pharmaceutical development. It represents a critical chapter in the history of analytical method validation, one that instilled global harmony and continues to underpin the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicines worldwide.

In the history of analytical science, the establishment of formal validation protocols marks the transition from art to science, providing a standardized framework for ensuring that analytical methods consistently produce reliable, trustworthy data. Analytical method validation is the process of providing documented evidence that a test procedure does what it is intended to do, establishing through laboratory studies that the method's performance characteristics meet the requirements for its intended analytical application [2]. In regulated environments, this process is not merely good science—it is a fundamental regulatory requirement for all drug substance and drug product analytical procedures [11].

The evolution of validation guidelines, driven by agencies like the FDA and the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) since the late 1980s, has created a harmonized understanding of the core pillars that underpin method validity [2] [12]. These pillars—including accuracy, precision, specificity, and others—form an interlocking system of checks that collectively demonstrate a method's suitability. This guide explores these fundamental parameters in detail, providing researchers and drug development professionals with both the theoretical foundation and practical methodologies needed for rigorous method validation.

Historical Context of Validation Guidelines

The formalization of analytical method validation began in earnest in the late 1980s when regulatory bodies started issuing comprehensive guidelines. A pivotal moment came in 1987, when the FDA designated the specifications in the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) as legally recognized for determining compliance with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [2]. This established a benchmark for method quality and consistency.

Subsequent decades saw significant efforts to harmonize requirements internationally. The landmark 1990 publication by Shah et al., "Analytical methods validation: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies," laid important groundwork for bioanalytical method validation [13]. The FDA's 1999 draft guidance and its final 2001 "Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation" further refined these concepts, solidifying the core parameters discussed in this document [13]. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline, harmonizing requirements across the United States, Europe, and Japan, has become the contemporary international standard, defining the essential performance characteristics that constitute a validated analytical method [2].

The Fundamental Validation Parameters

Specificity

Definition and Importance: Specificity is the ability of a method to measure accurately and specifically the analyte of interest in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix [2]. It ensures that a peak's response is due to a single component, accounting for potential interference from excipients, impurities, or degradation products [14] [2]. This parameter is typically tested first, as it confirms the method is detecting the correct target.

Experimental Protocol: For chromatographic methods, specificity is demonstrated by the resolution of the two most closely eluted compounds, usually the major component and a closely-eluting impurity [2]. If impurities are available, specificity is shown by spiking the sample with these materials and demonstrating that the assay is unaffected. When impurities are unavailable, results are compared to a second well-characterized procedure [2]. Modern practice recommends using peak-purity tests based on photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) to demonstrate specificity by comparing results to a known reference material [2].

Accuracy

Definition and Importance: Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and either a conventional true value or an accepted reference value [14] [2]. It is a measure of an analytical method's exactness, sometimes termed "trueness," and is established across the method's specified range.

Experimental Protocol: Accuracy is measured as the percent of analyte recovered by the assay [2]. For drug substances, accuracy is determined by comparing results to the analysis of a standard reference material or a second, well-characterized method. For drug products, accuracy is evaluated by analyzing synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities of components [2]. Guidelines recommend collecting data from a minimum of nine determinations over at least three concentration levels covering the specified range (three concentrations, three replicates each) [2]. Data should be reported as percent recovery of the known, added amount, or as the difference between the mean and true value with confidence intervals.

Precision

Definition and Importance: Precision expresses the closeness of agreement among individual test results from repeated analyses of a homogeneous sample [2]. It is commonly evaluated at three levels: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility.

Experimental Protocol:

- Repeatability (intra-assay precision): Assesses results over a short time interval under identical conditions. Guidelines suggest a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (three levels/concentrations, three repetitions each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [2]. Results are typically reported as % RSD (Relative Standard Deviation).

- Intermediate precision: Evaluates within-laboratory variations from random events such as different days, analysts, or equipment. An experimental design should be used to monitor effects of individual variables, typically involving two analysts preparing and analyzing replicate sample preparations using different HPLC systems [2]. The %-difference in mean values is statistically tested (e.g., Student's t-test).

- Reproducibility: Represents collaborative studies between different laboratories, requiring comparison of standard deviation, relative standard deviation, and confidence intervals [2].

Table 1: Precision Measurements and Their Specifications

| Precision Type | Conditions | Minimum Testing Requirements | Reporting Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | Same analyst, same day, identical conditions | 9 determinations across 3 concentration levels or 6 determinations at 100% test concentration | % RSD |

| Intermediate Precision | Different days, different analysts, different equipment | Two analysts preparing and analyzing replicates independently | %-difference in means, statistical testing |

| Reproducibility | Different laboratories | Collaborative studies between laboratories | Standard deviation, % RSD, confidence intervals |

Sensitivity (Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantitation)

Definition and Importance: Sensitivity encompasses both the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ). The LOD is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected but not necessarily quantitated, while the LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantitated with acceptable precision and accuracy [2].

Experimental Protocol: The most common approach uses signal-to-noise ratios (S/N)—typically 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ [2]. An alternative calculation-based method uses the formula: LOD/LOQ = K(SD/S), where K is a constant (3 for LOD, 10 for LOQ), SD is the standard deviation of response, and S is the slope of the calibration curve [2]. Regardless of the determination method, an appropriate number of samples must be analyzed at the calculated limit to fully validate method performance at that level.

Linearity and Range

Definition and Importance: Linearity is the ability of a method to provide test results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a given range [14]. The range is the interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations that have been demonstrated to be determined with acceptable precision, accuracy, and linearity using the method as written [2].

Experimental Protocol: Guidelines specify a minimum of five concentration levels to determine range and linearity [2]. The range should be expressed in the same units as test results. Data reporting should include the equation for the calibration curve line, the coefficient of determination (r²), residuals, and the curve itself.

Table 2: Minimum Recommended Ranges for Analytical Methods

| Method Type | Minimum Recommended Range |

|---|---|

| Assay | 80-120% of target concentration |

| Impurity Testing | From reporting level to 120% of specification |

| Content Uniformity | 70-130% of target concentration |

| Dissolution Testing | ±20% over specified range |

Robustness

Definition and Importance: Robustness measures a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, providing an indication of reliability during normal usage [14] [2]. This parameter evaluates how resistant the method is to typical operational fluctuations.

Experimental Protocol: Robustness is tested by deliberately varying method parameters around specified values and assessing the impact on method performance [14] [2]. For chromatographic methods, this might include variations in pH, mobile phase composition, columns, temperature, or flow rate. In a Quality by Design (QbD) approach, key parameters are varied during method development to identify and address potential issues early.

The Validation Workflow Relationship

The fundamental validation parameters are interconnected through a logical workflow. The following diagram illustrates their relationships and the typical sequence of evaluation:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful method validation requires specific high-quality materials and reagents. The following table outlines key solutions and their functions in validation experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Provides accepted reference values for accuracy determination and method calibration [2] |

| Chromatographic Columns | Stationary phases for separation; critical for testing specificity and robustness [2] |

| Mobile Phase Components | Liquid phase for chromatographic separation; composition affects specificity and robustness [2] |

| Matrix Blanks | Sample matrix without target analyte; essential for specificity testing to confirm no interference [14] |

| Impurity Standards | Isolated impurities for specificity testing; demonstrate method can distinguish analyte from impurities [2] |

| System Suitability Standards | Reference mixtures to verify chromatographic system performance before validation testing [12] |

The fundamental validation parameters—specificity, accuracy, precision, sensitivity, linearity, range, and robustness—represent the essential pillars supporting reliable analytical methods. These parameters form an interconnected framework that collectively demonstrates a method's suitability for its intended purpose. As the pharmaceutical industry evolves, with emerging trends like continuous process verification and digital transformation gaining prominence, these core principles remain the foundation of quality and compliance [15].

Understanding these parameters, their experimental determination, and their interrelationships enables researchers to develop robust methods that generate reliable data, support regulatory submissions, and ultimately ensure product quality and patient safety. While validation approaches may be phased appropriately across drug development stages, the fundamental pillars remain constant, providing the scientific rigor necessary for confident decision-making throughout the product lifecycle [11].

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the European Union establish and enforce the regulatory frameworks that guarantee the safety, efficacy, and quality of pharmaceutical products [16]. While sharing this common mission, their distinct approaches have profoundly influenced global industry practices, particularly in the realm of analytical method validation and quality assurance. The foundational FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations stipulate minimum requirements for the methods, facilities, and controls used in manufacturing, processing, and packing of a drug product, ensuring it is safe for use and possesses the ingredients and strength it claims to have [17]. The historical trajectory of analytical method validation protocols reveals a significant evolution: a shift from a compliance-driven, quality-by-testing paradigm to a modern, proactive framework centered on Quality by Design (QbD) and risk-based approaches across the entire product life cycle [18]. This whitepaper examines how the adoption and implementation of FDA and EMA guidelines have shaped and continue to transform industry standards and experimental protocols.

Historical Evolution of Validation Guidelines

The concept of validation within the pharmaceutical industry has undergone a fundamental transformation over the past several decades, driven largely by regulatory initiatives.

The Paradigm Shift to Quality by Design

The initial validation principles, as outlined in the FDA's 1987 guidance on general principles of process validation, focused on a traditional "fixed-point" approach where validation activities were typically concentrated in the late stages of product development, just before commercial filing [18]. A significant quality paradigm shift began in the early 2000s, moving toward building quality into the product and process design. As defined by the FDA, Quality by Design (QbD) is "a systematic approach to development that begins with predefined objectives and emphasizes product and process understanding and process control, based on sound science and quality risk management" [18]. Regulatory agencies actively encouraged this shift through various initiatives, including the FDA's 2004 report "Pharmaceutical cGMPs for the 21st Century – A Risk Based Approach" and the subsequent development of the ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 guidelines, which outlined the scientific and risk-based foundations for pharmaceutical development and quality systems [18].

The Analytical Procedure Life Cycle

The validation of analytical procedures has mirrored this broader evolution. The traditional, checklist approach to method validation is being superseded by the Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (APLC) model, an enhanced approach driven by Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles [18]. This holistic model, reflected in modern guidelines like USP General Chapter <1220> and the new ICH Q14 and Q2(R2) guidelines, provides connectivity between all stages of an analytical procedure's life—from initial design and development to continuous performance monitoring [18]. The major driver for this life cycle approach is to ensure the "fitness for use" of the reportable value, which forms the basis for critical decisions regarding a product's quality and compliance [18]. This represents a fundamental change in philosophy, from merely satisfying regulatory requirements to achieving a deep scientific understanding of the analytical procedure itself.

The following timeline illustrates the key milestones in this regulatory and conceptual evolution:

Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Regulatory Frameworks

Understanding the distinct organizational structures and philosophical approaches of the FDA and EMA is crucial for navigating their respective guidelines and their impact on industry practices.

Organizational Structure and Governance

The FDA operates as a centralized federal authority within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) possesses direct decision-making power to approve, reject, or request additional information for new drug applications (NDAs) and Biologics License Applications (BLAs) [16]. This centralized model enables relatively swift decision-making, with review teams composed of full-time FDA employees, and results in immediate nationwide market access upon approval [16].

In contrast, the EMA functions as a coordinating body within a network of national competent authorities across EU Member States. For the centralized procedure, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) conducts the scientific evaluation, but the legal authority to grant marketing authorization resides with the European Commission [16]. This network model incorporates broader scientific perspectives from across Europe but requires more complex coordination, reflecting diverse healthcare systems and medical traditions [16].

Key Differences in Regulatory Approaches

The structural differences between the two agencies lead to variations in their regulatory approaches, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Differences Between FDA and EMA

| Aspect | U.S. FDA | European Medicines Agency (EMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Structure | Centralized federal authority [16] | Coordinating network of national agencies [16] |

| Primary Application Types | New Drug Application (NDA), Biologics License Application (BLA) [16] | Centralized, Decentralized, and National Procedures [16] |

| Expedited Programs | Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review [16] | Accelerated Assessment, Conditional Approval [16] |

| Pediatric Requirements | Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) - studies often post-approval [16] | Pediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) - agreed before pivotal adult studies [16] |

| Risk Management | Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) when necessary [16] | Risk Management Plan (RMP) required for all new applications [16] |

| Clinical Trial Comparator | More accepting of placebo-controlled trials [16] | Generally expects comparison against relevant existing treatments [16] |

These differences necessitate strategic planning by drug developers aiming for both the U.S. and EU markets. For instance, a clinical trial designed to meet EMA's expectations for an active comparator may be more complex and costly than a placebo-controlled trial that might be acceptable to the FDA [16].

Impact on Industry Practices and Standards

The divergent and convergent paths of FDA and EMA guidelines have directly shaped how pharmaceutical companies operate, from clinical development to quality control.

Clinical Trial Design and Conduct

The recent finalization of ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice in 2025 marks a significant evolution, introducing flexible, risk-based approaches and embracing innovations in trial design, conduct, and technology [19] [20]. This update, adopted by both the FDA and EU member states, encourages the use of a broader range of modern trial designs and data sources while maintaining a focus on participant protection and data reliability [19]. Furthermore, disease-specific guidelines continue to evolve. A 2025 comparative analysis of FDA and EMA guidelines for ulcerative colitis (UC) trials highlighted the FDA's 2022 emphasis on balanced participant representation and the use of full colonoscopy for endoscopic assessment, posing new implementation challenges for sponsors [21].

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC)

The area of CMC has seen both significant regulatory convergence and notable ongoing differences. The EMA's 2025 guideline on clinical-stage Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) serves as a primary reference, consolidating over 40 previous documents [22]. From a CMC perspective, the guideline's structure aligns well with the Common Technical Document (CTD) format, indicating substantial convergence between FDA and EMA expectations for organizing CMC information [22]. However, critical differences remain, particularly for cell-based therapies. These include divergent requirements for allogeneic donor eligibility determination, where the FDA is more prescriptive, and varying expectations for GMP compliance, with the EU mandating self-inspections and the FDA employing a phased, attestation-based approach verified later via pre-license inspection [22].

The Modern Analytical Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of modern, QbD-driven validation protocols requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components of the researcher's toolkit for robust analytical method development and validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation Protocols |

|---|---|

| System Suitability Standards | Verifies chromatographic system performance prior to and during analysis to ensure data validity [18]. |

| Reference Standards (Primary & Secondary) | Serves as the definitive benchmark for quantifying the analyte of interest and establishing method accuracy [13]. |

| Stability-Indicating Metrics | Used in forced degradation studies to demonstrate the method's specificity in detecting analyte degradation [18]. |

| Critical Reagent Kits (e.g., for ELISA) | Provides key components for ligand-binding assays; requires rigorous characterization and stability testing [13]. |

| Matrix Components (e.g., serum, plasma) | Essential for validating bioanalytical methods to assess and control for matrix effects and ensure selectivity [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Adherence to regulatory guidelines requires the execution of standardized, well-documented experimental protocols. The following sections outline core methodologies for validating analytical procedures under the modern life cycle framework.

Protocol for Bioanalytical Method Validation

This protocol is based on FDA and consensus guidelines for validating ligand-binding assays (e.g., ELISA) used in pharmacokinetic studies [13].

- Objective: To establish and document that the bioanalytical method is suitable for the reliable quantification of the analyte in a specific biological matrix.

- Materials:

- Reference Standard: Analyte of known purity and identity.

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Prepared in the same biological matrix as study samples at low, medium, and high concentrations.

- Critical Reagents: Including antibodies, conjugates, and substrates. Full characterization data (source, lot, concentration) must be documented.

- Methodology:

- Selectivity and Specificity: Assess interference from at least 6 individual sources of the matrix. Cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds should be evaluated.

- Accuracy and Precision: Perform a minimum of 5 runs per concentration level (LLOQ, Low, Mid, High QC) with 5 replicates per run. Accuracy should be within ±20% (±25% for LLOQ) of the nominal value, and precision should not exceed 20% CV (25% for LLOQ).

- Calibration Curve: Generate using a minimum of 6 non-zero concentrations. The curve model (e.g., 4- or 5-parameter logistic) must be justified and consistently used.

- Stability: Conduct experiments to evaluate analyte stability in the matrix under conditions of storage, freeze-thaw cycles, and benchtop temperatures.

Protocol for Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (APLC) Implementation

This protocol describes the enhanced approach for pharmaceutical analysis as per ICH Q2(R2) and USP <1220> [18].

- Stage 1: Procedure Design

- Define an Analytical Target Profile (ATP): A prospective description of the required quality of the reportable value and the level of uncertainty that is fit for purpose.

- Example ATP: "The procedure must be able to quantify impurity X in the drug substance with a target uncertainty of ±0.05% at a specification level of 0.5%."

- Risk Assessment: Use tools (e.g., Fishbone diagram, FMEA) to identify and rank potential method variables (instrument, analyst, reagent) that could impact the ATP.

- Stage 2: Procedure Performance Qualification

- This stage aligns with the traditional validation study but is guided by the ATP.

- Experiments are designed to confirm that the procedure performs as intended, testing parameters such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and range.

- The establishment of an Analytical Control Strategy is critical, defining the level of control for each critical method parameter.

- Stage 3: Ongoing Procedure Performance Verification

- System Suitability Tests (SST): Defined based on the ATP to ensure the procedure is functioning correctly at the time of use.

- Continuous Monitoring: Reportable values and associated QC data are tracked over time to verify the procedure remains in a state of control.

- Knowledge Management: All data and decisions from the procedure's life cycle are documented, facilitating any future changes or improvements.

The workflow for this life cycle approach is systematic and iterative, as shown below:

Case Studies in Regulatory Adoption

Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs)

The regulation of ATMPs (cell and gene therapies) provides a clear case study of both convergence and divergence. The EMA's 2025 clinical-stage ATMP guideline is a multidisciplinary document that consolidates quality, non-clinical, and clinical requirements [22]. An analysis of its CMC section reveals significant convergence with FDA expectations, as it is structured around the CTD format, providing a common roadmap for sponsors [22]. However, practical differences persist. For example, the FDA maintains more prescriptive requirements for allogeneic donor eligibility determination, including specific tests and laboratory qualifications, whereas the EMA guideline references broader EU and member state legal requirements [22]. This divergence can create additional complexity and cost for developers pursuing global markets.

Expedited Review Pathways

Both agencies have established programs to accelerate the development and review of drugs for serious conditions, but their structures differ, shaping sponsor strategy. The FDA offers multiple, overlapping expedited programs (Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review) that can be used in combination to provide intensive FDA guidance and faster approval based on surrogate endpoints [16]. The EMA's main expedited mechanism is Accelerated Assessment, which shortens the review timeline but has more stringent eligibility criteria [16]. A 2025 development is the FDA's pilot of a Commissioner's National Priority Voucher (CNPV) program, which suggests that drug pricing, an area traditionally outside the FDA's remit, could informally influence regulatory prioritization, representing a significant potential shift in regulatory policy [23].

The landscape of pharmaceutical regulation and analytical validation is dynamic. The guidelines issued by the FDA and EMA have been instrumental in shaping industry practices, driving a global shift toward more scientific, risk-based, and life cycle-oriented approaches. The ongoing adoption of ICH E6(R3) for clinical trials and the finalization of ICH Q14 and Q2(R2) for analytical procedures will further embed these principles, promoting greater international harmonization [19] [20] [18]. Future developments will likely focus on the integration of advanced technologies and data analytics, continued efforts toward global regulatory convergence for complex products like ATMPs [22], and adapting regulatory frameworks to accommodate innovations such as continuous manufacturing [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep and nuanced understanding of both the similarities and differences between FDA and EMA guidelines remains not just a regulatory necessity, but a strategic imperative for efficient global drug development.

The evolution of analytical method validation is characterized by a significant "Prescriptive Era," a period dominated by standardized, checklist-based protocols. These early approaches provided the foundational framework for ensuring data quality, safety, and efficacy in drug development and other scientific fields by offering a structured means of compliance with growing regulatory requirements. Framed within the history of analytical method validation protocols, this era represents a critical transition from informal, idiosyncratic practices to a more systematic and defensible approach to quality assurance. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the strengths and limitations of these early checklist methodologies is not merely an academic exercise; it provides essential context for contemporary validation practices and informs the development of next-generation protocols [24] [25]. This whitepaper delves into the core principles of these prescriptive approaches, evaluates their enduring strengths and inherent limitations, and details the experimental protocols that characterized this formative period in pharmaceutical sciences.

Historical Context and Defining the "Prescriptive Era"

The "Prescriptive Era" in analytical method validation emerged as a direct response to the increasing complexity of pharmaceutical analysis and the need for international regulatory harmonization. Prior to this period, method validation was often an informal process, varying significantly between laboratories and lacking standardized criteria. The impetus for change was the necessity to prove that an analytical method was acceptable for its intended use, ensuring that measurements of a drug's potency, bioavailability, and stability were accurate, specific, and reliable [24] [25].

The formalization of this era was largely driven by the establishment of guidelines from international regulatory bodies. The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) played a pivotal role with the issuance of two landmark guidelines: Q2A, "Text on Validation of Analytical Procedures" (1994) and Q2B, "Validation of Analytical Procedure: Methodology" (1996). These documents, alongside standards from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), codified a specific set of performance parameters that required validation [24] [25]. This created a paradigm where compliance was demonstrated by systematically "checking off" a pre-defined list of validation characteristics, hence the term "checklist approach." The primary objective was to ensure that methods for analyzing drug substances and products were thoroughly characterized, providing a unified standard for industry and regulators across the United States, the European Union, and Japan [25].

Core Principles of Early Checklist Approaches

The checklist approach was fundamentally rooted in a series of core principles that emphasized standardization, comprehensiveness, and demonstrable compliance.

- Standardization and Harmonization: The primary principle was the replacement of variable, lab-specific practices with a uniform set of criteria. The ICH Q2 guidelines provided a common language and a unified set of requirements for validation, which was crucial for multinational drug development and registration [25].

- Parameter-Centric Validation: The approach decomposed the abstract concept of "method quality" into a list of discrete, measurable performance characteristics. The validation process became an exercise in empirically testing each of these parameters against pre-defined acceptance criteria [26].

- Documentation and Audit Trail: A key principle was the creation of a documented evidence trail. Validation activities were conducted according to a pre-approved validation protocol, and results were meticulously documented in a validation report, providing objective evidence for regulatory scrutiny [25].

- Fitness for Purpose: Despite its prescriptive nature, the underlying principle was to demonstrate that the method was suitable for its intended use. The specific validation parameters required varied depending on the type of analytical procedure (e.g., identification tests, impurity tests, assays) [25].

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters as Defined by ICH Q2 and Other Regulatory Guidelines

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Primary Regulatory Source |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true value. | ICH, USP, FDA [25] |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. Includes repeatability and intermediate precision. | ICH, USP, FDA [25] |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | ICH, USP [25] |

| Linearity | The ability to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte. | ICH, USP, FDA [25] |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which suitability has been demonstrated. | ICH, USP, FDA [25] |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified. | ICH, USP [25] |

| Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitatively determined. | ICH, USP [25] |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | ICH, USP [25] |

Strengths of the Checklist Paradigm

The prescriptive, checklist-based approach brought about transformative strengths that addressed critical needs in pharmaceutical analysis and regulation.

Foundation for Regulatory Compliance and Harmonization

The ICH Q2 guidelines provided a clear, internationally accepted roadmap for meeting regulatory expectations. This harmonization simplified the drug approval process across different regions, reduced redundant testing, and provided a definitive standard for audits and inspections. For scientists, it eliminated guesswork regarding what was required for method validation, ensuring that development efforts were aligned with global regulatory requirements from the outset [24] [25].

Enhanced Consistency and Data Quality

By mandating a standard set of experiments, the checklist approach ensured a consistent and comprehensive evaluation of analytical methods. This systematic process significantly reduced the risk of overlooking critical performance characteristics, thereby improving the overall quality and reliability of analytical data. It provided a structured framework that was particularly valuable for less experienced analysts, ensuring thoroughness regardless of an individual's level of expertise [27] [28].

Improved Communication and Efficiency

The establishment of standardized terminology and parameters fostered clear and unambiguous communication between laboratories, sponsors, and regulatory agencies. Furthermore, the use of a predefined checklist streamlined the validation process itself, making audit preparation more efficient and facilitating the delegation of specific tasks within a team [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Strengths of Checklist-Based Validation Approaches

| Strength | Quantitative or Qualitative Impact | Evidence from Broader Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency & Completeness | Ensures common and known risks/parameters are not overlooked [27]. | In risk management, checklist analysis provides a "comprehensive starting point" and ensures completeness [27]. |

| Efficiency & Speed | Accelerates audit preparation and the questioning process [28]. | Checklists are noted for their ability to speed up processes and are an "efficient use of time and resources" [27] [28]. |

| Structured Guidance | Supports less experienced team members by providing a clear roadmap [27]. | Checklist analysis "helps less experienced team members identify risks" and "support auditor knowledge" [27] [28]. |

| Facilitation of Delegation | Allows a lead auditor to unambiguously delegate sections of an audit [28]. | Checklists provide clear accountability, enabling effective delegation within a team [28]. |

Limitations and Critical Weaknesses

Despite its foundational strengths, the rigid application of the checklist paradigm revealed several significant limitations that prompted the evolution of validation science.

The "Tick-Box" Mentality and Suppression of Scientific Judgment

A primary criticism was the tendency for the process to devolve into a mechanical "tick-box" exercise. This mentality could lead to a superficial review where the mere completion of a test was prioritized over a deep, scientific understanding of the method's behavior and limitations. Auditors and analysts relying solely on checklists could miss subtle but critical issues not explicitly listed, as the rigid structure discouraged professional curiosity and critical thinking beyond the set questions [29] [28].

Inherent Lack of Flexibility

Checklists, by their nature, are often generic to allow for wide application. This can render them unsuitable for novel or highly complex methodologies that do not fit the standard mold. They lack the flexibility to adapt to unique project-specific risks, emerging technologies, or non-routine scenarios, potentially stifling innovation and failing to address the most relevant questions for a given method's specific context [27] [28].

Failure to Address Broader Implications

The early checklist approach was predominantly focused on the technical performance of the method itself. It often failed to adequately consider the broader consequences of the assessment, a key source of validity evidence in modern frameworks [30]. This includes the impact of the method's results on downstream decisions, patient safety, and the potential for unintended negative effects, such as unnecessary re-testing or incorrect batch release decisions based on a technically "valid" but practically flawed method [30].

Risk of Becoming Outdated

Checklists require continuous maintenance to remain relevant. As new scientific knowledge, technologies, and types of therapeutics (e.g., biologics, cell therapies) emerge, a static checklist can quickly become obsolete. Without regular updating based on lessons learned, they may perpetuate the evaluation of irrelevant parameters while missing new, important risks [27].

Diagram: Checklist Approach Strengths and Limitations - This workflow illustrates the parallel paths of strengths (red) and limitations (blue) that result from applying a prescriptive checklist to analytical method validation, leading to a mixed outcome.

Detailed Experimental Protocols of the Prescriptive Era

The validation process during the Prescriptive Era was characterized by a series of standardized, well-defined experimental protocols designed to measure each parameter on the checklist.

Protocol for Accuracy

- Objective: To demonstrate the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the value accepted as a true value.

- Methodology: This was typically determined by analyzing samples spiked with known quantities of the analyte (drug substance) into a placebo or a synthetic mixture of excipients. The study was performed at a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration), with multiple replicates (e.g., n=3) at each level.

- Data Analysis: The recovery of the analyte at each level was calculated as:

(Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) * 100%. The mean recovery across all levels, along with the relative standard deviation, was then reported and evaluated against pre-defined acceptance criteria (e.g., mean recovery of 98-102% with RSD ≤ 2%) [25].

Protocol for Precision

- Objective: To evaluate the degree of scatter in a series of measurements under prescribed conditions.

- Methodology: Precision was investigated at multiple levels:

- Repeatability: Multiple injections (n=6) of a homogeneous sample at 100% of the test concentration by a single analyst using the same equipment on the same day.

- Intermediate Precision: The same repeatability experiment performed by different analysts, on different days, or using different instruments within the same laboratory.

- Data Analysis: The standard deviation or relative standard deviation (RSD) of the results was calculated. Acceptance criteria were set, for example, as RSD ≤ 1.0% for an assay [25].

Protocol for Linearity and Range

- Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical procedure produces results directly proportional to analyte concentration.

- Methodology: A series of standard solutions were prepared across a specified range (e.g., 50-150% of the target concentration). A minimum of five concentration levels were analyzed.

- Data Analysis: The instrument response (e.g., peak area) was plotted against concentration. The data was subjected to linear regression analysis to calculate the correlation coefficient (r), y-intercept, slope, and residual sum of squares. Acceptance criteria typically required a correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.999 [25].

Protocol for Specificity

- Objective: To prove that the measured response is due solely to the analyte of interest.

- Methodology: For chromatographic methods, this involved challenging the method by analyzing blank samples (placebo), samples spiked with potential interferents (degradation products, synthetic impurities, excipients), and stressed samples (e.g., exposed to heat, light, acid, base, oxidation).

- Data Analysis: Chromatograms were examined for peak purity (e.g., using diode array or mass spectrometry detection) and resolution. The method was considered specific if the analyte peak was pure and baseline-separated from all other peaks, and the blank showed no interference [25].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Validation Experiments

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Drug Substance (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) | Serves as the primary analyte for which the method is being validated. Used to prepare standard and sample solutions for accuracy, linearity, and precision studies. |

| Placebo (Excipient Mixture) | The formulation matrix without the active ingredient. Used in specificity and accuracy experiments to demonstrate the absence of interference and to simulate the real sample. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Highly characterized materials with known purity and identity. Used to calibrate instruments and prepare standard solutions for generating the calibration curve in linearity studies. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the drug substance or product intentionally degraded under stress conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation). Used to demonstrate the method's stability-indicating properties and specificity. |

| Chromatographic Solvents & Reagents | High-purity mobile phase components, buffers, and diluents. Their quality and consistency are critical for achieving robust and reproducible chromatographic performance. |

The Prescriptive Era, with its steadfast reliance on checklist approaches, laid the indispensable groundwork for modern analytical method validation. It successfully instilled discipline, harmonized global standards, and provided a clear, auditable framework for proving method suitability. The strengths of this era—regulatory clarity, consistency, and improved data quality—are undeniable and continue to underpin current good manufacturing practices. However, the limitations of this paradigm, particularly its inflexibility, potential to stifle scientific judgment, and narrow focus on technical parameters over broader implications, ultimately drove the evolution toward more holistic, risk-based validation frameworks. For today's drug development professional, appreciating this historical context is crucial. It underscores that while checklists remain powerful tools for ensuring comprehensiveness, they are most effective when used to support, rather than replace, expert scientific reasoning and a deep, process-oriented understanding of the analytical method. The legacy of the Prescriptive Era is not a set of obsolete rules, but a foundation upon which more dynamic and intelligent validation practices have been built.

Modern Methodologies: Implementing Phase-Appropriate and QbD-Driven Validation

The development of analytical method validation protocols represents a significant evolution in pharmaceutical sciences, shifting from rigid, one-size-fits-all approaches to flexible, risk-based strategies. The fit-for-purpose principle has emerged as a cornerstone in this historical development, recognizing that the level of analytical validation should be commensurate with the stage of drug development and the specific decision-making needs at each phase [31]. This paradigm acknowledges that early research requires different evidence than late-stage regulatory submissions, thereby optimizing resource allocation while maintaining scientific rigor.

This approach has become particularly crucial in modern drug development, especially for complex modalities like cell and gene therapies, where well-defined platform methods may not yet exist and critical quality attributes may not be fully characterized initially [32]. The phase-appropriate validation framework allows developers to generate meaningful data throughout the drug development lifecycle while progressively building the analytical evidence package required for regulatory approvals.

Conceptual Foundation of Fit-for-Purpose Validation

Core Principles and Definitions

The International Organisation for Standardisation defines method validation as "the confirmation by examination and the provision of objective evidence that the particular requirements for a specific intended use are fulfilled" [31]. This definition inherently contains the essence of the fit-for-purpose approach—the notion that validation must be tied to "specific intended use" rather than abstract perfection.

Fundamentally, fit-for-purpose assay validation progresses through two parallel tracks that eventually converge: one experimental and one operational. The experimental track establishes the method's purpose and defines acceptance criteria, while the operational track characterizes assay performance through systematic experimentation [31]. The critical evaluation occurs when technical performance is measured against pre-defined purpose—if the assay meets these expectations, it is deemed fit for that specific purpose.

The Validation Spectrum: From Exploratory to Compliant

The position of a biomarker or analytical method along the spectrum between research tool and clinical endpoint dictates the stringency of experimental proof required for method validation [31]. This spectrum encompasses:

- Exploratory assays for early discovery and candidate screening

- Fit-for-purpose assays for preclinical and early clinical phases

- Qualified assays for mid-stage clinical development

- Fully validated assays for late-stage clinical trials and commercialization [33] [34]

This framework acknowledges that method flexibility is advantageous during early development when processes and products are still being characterized, while method standardization becomes crucial during later stages when regulatory compliance and product consistency are paramount [34].

Phase-Appropriate Implementation Framework

Preclinical to Phase 1: Fit-for-Purpose Assays

During early drug development, the primary goal is generating reliable data for internal decision-making regarding candidate selection and initial safety assessment. Fit-for-purpose assays at this stage require demonstration of accuracy, reproducibility, and biological relevance sufficient to support early safety and pharmacokinetic studies [33]. These assays function as "prototypes" – developed efficiently to generate meaningful data but not yet meeting all regulatory requirements for later development stages [34].

The experimental focus at this stage involves limited verification, typically requiring 2-6 experiments to establish that methods provide reliable results for making go/no-go decisions [33]. Common applications include early-stage drug discovery screening, exploratory biomarker studies, preclinical PK/PD investigations, and proof-of-concept research [34]. According to regulatory guidelines, validation of analytical procedures is usually not required for original investigational new drug submissions for Phase 1 studies; however, sponsors must demonstrate that test methods are appropriately controlled using scientifically sound principles [32].

Phase 2 Clinical Studies: Qualified Assays

As drug development advances to Phase 2 clinical studies, the analytical requirements intensify. The focus shifts to demonstrating repeatable and robust dose-dependent responses while ensuring acceptable intermediate precision and accuracy across multiple runs [33]. This qualification stage typically requires 3-8 experiments to evaluate and refine critical performance attributes including robustness, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, specificity, and stability [33].

Table 1: Qualification Stage Assay Performance Criteria

| Performance Parameter | Preliminary Acceptance Criteria | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Interference | Drug matrix/excipients don't interfere with assay signal | Ensures measurement specificity |

| Accuracy | EC50 values for Reference Standard and Test Sample agree within 20% | Measures closeness to true value |

| Precision (Replicates) | %CV for replicates within 20% | Evaluates repeatability |

| Precision (Curve Fit) | Goodness-of-fit to 4-parameter curve >95% | Assesses model appropriateness |

| Intermediate Precision | Relative Potency variation across experiments CV <30% | Measures run-to-run variability |

| Parallelism | 4-parameter logistical dose-response curves of Reference Standard and Test Sample are parallel | Ensures similar biological activity |

| Stability | Acceptable stability after 1 and 3 freeze/thaw cycles | Determines sample handling requirements |

At this stage, developers typically establish preliminary acceptance criteria and assay performance metrics through a minimum of three replicate experiments following the finalized assay protocol [33]. For more robust qualification, two analysts typically conduct at least three independent runs, each using three assay plates, enabling statistical analysis of relative potency and percent coefficient of variation (%CV) [33].

Phase 3 to Commercialization: Validated Assays