FTIR Spectroscopy: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine and Pharma

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, a versatile analytical technique renowned for its molecular fingerprinting capabilities.

FTIR Spectroscopy: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine and Pharma

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, a versatile analytical technique renowned for its molecular fingerprinting capabilities. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches across pharmaceuticals, clinical diagnostics, and environmental science, and practical troubleshooting guidance. The review also critically assesses validation protocols and comparative performance against other techniques, highlighting the transformative impact of portable FTIR and AI-driven chemometrics for real-time, non-destructive analysis in both R&D and quality control settings.

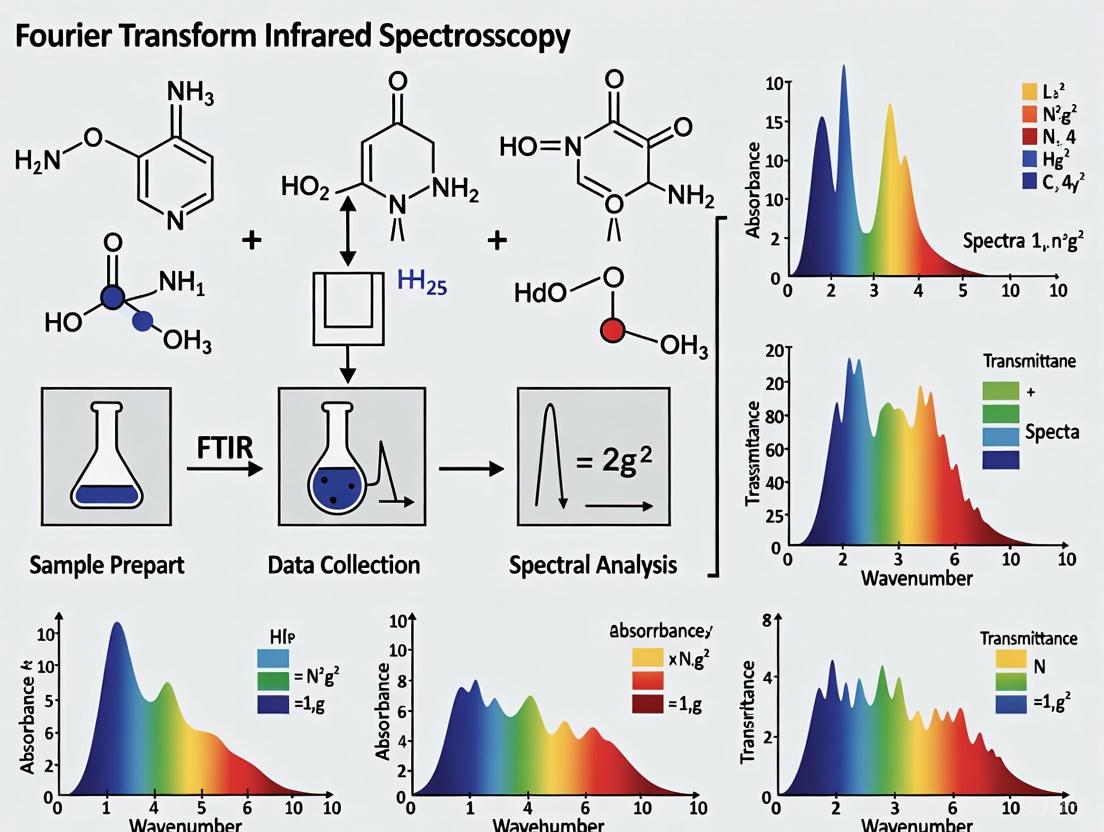

FTIR Fundamentals: Decoding the Molecular Fingerprint

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique that identifies organic, polymeric, and inorganic materials by measuring their absorption of infrared light [1]. The technique is grounded in the interaction between infrared light and matter, specifically the excitation of molecular vibrations when the energy of the incident light matches the vibrational energy level difference within a molecule [2]. The resulting spectrum serves as a unique "chemical fingerprint" for material identification and quantification [3]. FTIR has largely superseded older dispersive infrared methods due to its significant advantages, including higher signal-to-noise ratios, faster data collection, and better spectral resolution [3] [4]. These benefits, known as the Fellgett's (multiplex), Jacquinot's (throughput), and Connes' (precision) advantages, originate from the use of an interferometer and a Fourier Transform mathematical process to decode spectral information [5] [6].

Fundamental Principles of Light-Matter Interaction

Molecular Vibrations and Infrared Absorption

The core of FTIR spectroscopy lies in the study of molecular vibrations. The atoms in chemical compounds are in constant motion, vibrating in different ways such as stretching, bending, rocking, twisting, and wagging [3]. Each of these vibrations occurs at a specific frequency that is characteristic of the chemical bond and the overall molecular structure [3]. For a vibration to be active in the infrared spectrum, it must result in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule [2]. When the energy of the incoming infrared light matches the vibrational energy level difference of a molecular bond (ΔE_vib = hν_light), the radiation is absorbed, promoting the bond to a higher vibrational energy state [2]. This principle enables the identification of specific functional groups within a molecule, as they absorb IR light at characteristic and predictable wavenumbers [5].

The FTIR Spectrometer and the Interferometer

In an FTIR spectrometer, the fundamental design differs significantly from older dispersive instruments. The key component is an interferometer, most commonly of the Michelson design [4]. A broadband IR source is directed into the interferometer, where a beam splitter divides the light into two paths—one reflecting off a fixed mirror and the other off a moving mirror [6]. The two beams recombine at the beam splitter, and their interference, constructive or destructive, creates a complex signal called an interferogram [4] [6]. This interferogram, which encodes intensity information for all infrared frequencies simultaneously, is then passed through the sample and onto a detector. The final step involves the application of a Fourier Transform, a mathematical algorithm that deconvolutes the interferogram from the time domain into a familiar spectrum in the frequency domain: a plot of intensity (as absorbance or transmittance) versus wavenumber (cm⁻¹) [3] [6]. This process is illustrated in the workflow below.

Key Methodologies and Sampling Techniques

Selecting the appropriate sampling technique is critical for obtaining high-quality FTIR data. The choice depends on the sample's physical state (solid, liquid, gas), its properties (e.g., transparency, hardness), and the information required. The most common techniques are compared in the table below.

Table 1: Key FTIR Sampling Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique | Principle | Sample Preparation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission [3] [4] | IR light passes directly through a thin sample. | Extensive; requires dilution in IR-transparent matrices like KBr or slicing into thin films (<15 µm). | Polymer films, proteins, microplastics, gas cells [3] [4]. |

| Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) [3] [4] | IR light interacts with a sample in contact with a crystal via an evanescent wave. | Minimal to none; sample is simply placed in firm contact with the crystal. | Primary technique for solids, liquids, gels, powders; ideal for quality control and identification [3] [1]. |

| Diffuse Reflectance (DRIFTS) [3] [4] | IR light is scattered off the surface of a powdered sample. | Moderate; often requires grinding and mixing with KBr powder. | Powders, soils, catalysts, rough solid surfaces [3] [4]. |

| Specular Reflection [3] [4] | IR light is reflected directly off a smooth, reflective sample surface. | Low; requires a smooth, shiny surface. | Analysis of surface coatings, thin films on reflective substrates, and polymer layers [3]. |

| FTIR Microscopy (μ-FT-IR) [4] [5] | Combines microscopy with FTIR for high spatial resolution. | Varies; can use transmission, reflectance, or micro-ATR on a microscopic scale. | Microanalysis of contaminants, single fibers, multilayer films, and tissue samples [7] [4]. |

The relationships and selection criteria for these techniques are visualized in the following decision diagram.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Solid Sample Analysis via ATR

Principle: The ATR technique relies on the generation of an evanescent wave that penetrates a short distance (typically 0.5–5 µm) into a sample placed in intimate contact with a high-refractive-index crystal [3] [1].

Materials:

- FTIR spectrometer equipped with an ATR accessory (e.g., diamond, ZnSe, or Ge crystal).

- Solid sample (e.g., polymer piece, powder).

- Forceps and cleaning supplies (e.g., lint-free wipes, isopropanol).

- ATR clamp or pressure arm.

Procedure:

- Background Collection: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with a suitable solvent and a lint-free wipe. Initiate the spectrometer software and collect a background spectrum (also called a reference scan) with no sample present [4].

- Sample Placement: Place a representative portion of the solid sample directly onto the crystal surface. For powders, ensure full coverage of the crystal area.

- Apply Pressure: Engage the clamp or pressure arm to press the sample firmly and evenly against the crystal. This ensures good optical contact, which is crucial for a high-quality spectrum [1].

- Data Acquisition: Collect the sample spectrum. A typical measurement requires 16-32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ [4].

- Post-Measurement: Remove the sample and clean the crystal thoroughly before analyzing the next sample.

Protocol: Liquid Sample Analysis via Transmission

Principle: This method measures the attenuation of IR light as it passes through a thin layer of liquid sample, requiring the sample to be held in a cell with IR-transparent windows [3].

Materials:

- FTIR spectrometer.

- Liquid transmission cell (e.g., with KBr or NaCl windows and a fixed or adjustable pathlength spacer).

- Syringe or pipette.

- Appropriate solvent for dilution and cleaning.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Disassemble the liquid cell if necessary. Clean the windows carefully and reassemble the cell according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Background Collection: Place the empty, clean cell in the spectrometer beam path and collect a background spectrum.

- Sample Loading: Using a syringe or pipette, introduce the liquid sample into the cell port, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped in the beam path.

- Data Acquisition: Collect the sample spectrum. For very strong absorbers, a cell with a shorter pathlength (e.g., 0.1 mm) may be necessary to avoid total absorbance [3].

- Post-Measurement: Empty the cell and rinse thoroughly with a clean solvent. Disassemble and dry the parts if required for storage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful FTIR analysis requires not only the instrument but also the correct selection of accessories and consumables. The following table details key components of the FTIR toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FTIR Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Common Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals [3] [1] | Internal Reflection Element (IRE) that contacts the sample. | Diamond: Hard, durable, chemically inert; general purpose. ZnSe: Good balance of performance and cost; avoid strong acids. Ge: High refractive index; ideal for high-energy absorbers like rubber [1]. |

| IR-Transparent Salts [3] | Windows for liquid/gas transmission cells and matrix for solid pellets. | Potassium Bromide (KBr): For pellet preparation and windows. Sodium Chloride (NaCl): Common for liquid cells. Note: These materials are hygroscopic and require careful handling and storage [3]. |

| Liquid Cells [3] | Holds liquid samples for transmission analysis with a defined pathlength. | Sealed cells for volatile solvents, or demountable cells with Teflon spacers. Pathlength is selected based on sample absorptivity (e.g., 0.1 mm for neat solvents). |

| Pellet Die [3] | Device used to press powdered mixtures into solid, transparent pellets for transmission analysis. | Typically used with a hydraulic press to create KBr pellets containing ~1% of the sample of interest. |

| Cleaning Solvents [4] | High-purity solvents for cleaning ATR crystals and sample windows without leaving residue. | Reagent-grade isopropanol, hexane, or acetone. Compatibility with the crystal material must be verified (e.g., acetone can damage ZnSe). |

Spectral Interpretation and Data Analysis

Characteristic Group Frequencies

Interpreting an FTIR spectrum involves correlating the observed absorption bands, specifically their position (wavenumber), intensity, and shape, to specific molecular vibrations and functional groups. The mid-IR region (4000–400 cm⁻¹) is the most informative for this purpose [8]. The table below summarizes the characteristic absorption regions for major biomolecules and functional groups, which is particularly relevant for biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Table 3: Characteristic FTIR Absorption Bands for Biomolecules and Common Functional Groups

| Wavenumber Range (cm⁻¹) | Associated Vibration | Functional Group / Biomolecule Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| ~3600-3200 | O-H stretching, N-H stretching | Water, alcohols, carbohydrates, proteins (amide A) [8] [2]. |

| ~3050-2800 | C-H stretching | Lipids, fatty acyl chains in biomolecules [8]. |

| ~1745-1725 | C=O stretching | Esters in lipids [8]. |

| ~1700-1600 | C=O stretching, C-N stretching | Proteins (amide I band, mainly C=O stretch) [8]. |

| ~1600-1500 | N-H bending, C-N stretching | Proteins (amide II band) [8]. |

| ~1500-1350 | C-H bending | Lipids, proteins [8]. |

| ~1270-1000 | C-O-C stretching, P=O stretching | Phospholipids, nucleic acids, carbohydrates [8]. |

Advanced Data Processing

Modern FTIR analysis heavily relies on software and advanced chemometric methods for complex data interpretation [4] [9].

- Spectral Manipulation: Basic operations include baseline correction, atmospheric subtraction (to remove CO₂ and water vapor interference), normalization, and smoothing [4].

- Chemometric Analysis: For complex mixtures or to identify subtle spectral changes, multivariate statistical techniques are employed. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to reduce dimensionality and identify patterns or groupings in spectral data. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to develop quantitative calibration models that relate spectral data to reference concentrations of an analyte [9].

- Spectral Libraries: Computerized search algorithms can compare an unknown sample's spectrum against vast commercial and custom spectral libraries to propose potential identities [3]. However, this should be combined with expert interpretation, especially for mixtures [1].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy has revolutionized analytical chemistry, providing researchers with a powerful tool for molecular characterization across diverse fields, including pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics. The technique's core strength lies in its ability to transform a raw, complex interferogram into a detailed, interpretable spectrum that serves as a molecular "fingerprint" for the sample being analyzed [10] [11]. This transformation from raw data to actionable information is mediated by the mathematical power of the Fourier transform, which decodes the interferogram to reveal the sample's unique absorption characteristics at different infrared wavelengths [12] [6]. For drug development professionals, this process enables the precise identification of chemical compounds, assessment of biomolecular changes in cells, and monitoring of therapeutic responses, making it an indispensable technique in modern analytical research [9] [13].

The fundamental principle underlying FTIR spectroscopy is that chemical bonds within molecules vibrate at specific frequencies when exposed to infrared light, and these vibrations are uniquely characteristic of different functional groups and molecular structures [10]. Unlike older dispersive infrared spectrometers that measured one wavelength at a time, FTIR spectrometers simultaneously collect data across all wavelengths through the use of an interferometer, significantly accelerating data acquisition while improving sensitivity and wavelength accuracy [6] [11]. This technical advancement, coupled with sophisticated computational processing, allows researchers to obtain high-quality spectral data that can be leveraged for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of complex biological and chemical samples [9] [11].

Theoretical Foundation: The FTIR Process

From Infrared Radiation to Interferogram

The journey from sample to spectrum begins when a broadband infrared light source emits radiation encompassing the entire mid-infrared range, typically from 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ [10]. This polychromatic beam is directed into a Michelson interferometer, the core component of an FTIR spectrometer. The interferometer contains a beam splitter that divides the incoming light into two separate paths: one directed toward a fixed mirror and the other toward a moving mirror [6]. After reflection, these beams recombine at the beam splitter, where they interfere with each other constructively or destructively depending on the optical path difference (OPD) created by the moving mirror [10] [6].

This recombined light, now containing an interference pattern, then passes through or reflects off the sample, where specific wavelengths are absorbed by the molecules based on their vibrational characteristics [10]. The modified light finally reaches the detector, which records the intensity of the signal as a function of the moving mirror's position, producing a complex pattern known as an interferogram [6] [11]. Although the interferogram appears as a complex pattern of signals centered around zero path difference (the "centerburst"), it actually contains encoded information about all infrared wavelengths absorbed by the sample across the entire spectral range [12].

Figure 1: FTIR Instrumentation and Interferogram Generation. This workflow illustrates the path of IR light through the Michelson interferometer, sample interaction, and detection of the raw interferogram.

The Fourier Transform: Mathematical Conversion to Spectrum

The transformation of the interferogram into an interpretable spectrum represents the computational core of FTIR spectroscopy. The Fourier transform, a powerful mathematical algorithm, serves to deconvolute the complex interferogram by identifying all the constituent frequencies and their respective intensities [12] [6]. Conceptually, this process works by multiplying the interferogram with a vast series of cosine waves of different frequencies—when a cosine wave matches one of the frequencies present in the interferogram, their product generates a strong positive signal, while non-matching frequencies cancel out through positive and negative interference [12].

The result of this computational process is a frequency-domain spectrum that plots absorbance or transmittance against wavenumber (cm⁻¹), providing the characteristic molecular fingerprint used for analysis [10] [11]. Each peak in this spectrum corresponds to specific molecular vibrations, such as stretching or bending motions of chemical bonds, enabling researchers to identify functional groups and molecular structures present in the sample [10]. The entire transformation process occurs rapidly through modern computing systems, allowing researchers to obtain actionable spectral data in near real-time, a critical advantage for high-throughput applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics [9] [13].

Figure 2: Computational Transformation Process. This diagram outlines the mathematical conversion of the raw interferogram into an interpretable spectrum through Fourier transform processing.

Key FTIR Sampling Techniques and Methodologies

Sampling Techniques Comparison

FTIR spectroscopy offers several sampling techniques, each with distinct advantages for different sample types and analytical requirements in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. The selection of an appropriate sampling method is critical for obtaining high-quality spectral data that accurately represents the sample's molecular composition.

Table 1: Comparison of Major FTIR Sampling Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Sample Types | Preparation Needs | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission [11] | IR light passes directly through sample | Liquids, gases, solid pellets | Extensive (KBr pellets, precise thickness) | Historical reference method, gas analysis |

| ATR [11] | Evanescent wave penetrates sample in contact with crystal | Solids, liquids, semi-solids | Minimal to none | Polymers, biological tissues, routine analysis |

| Specular Reflectance [11] | IR light reflects from smooth surface | Smooth surfaces, thin films on reflective substrates | Minimal (clean, flat surface) | Coatings, thin polymer films |

| DRIFTS [11] | IR light diffusely scattered from rough surface | Powders, rough surfaces | Moderate (uniform packing) | Powdered pharmaceuticals, catalysts |

Among these techniques, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) has emerged as the predominant method for most pharmaceutical and biological applications due to its minimal sample preparation requirements and versatility [9] [11]. ATR operates by directing the IR beam through a crystal with a high refractive index (such as diamond or zinc selenide) in contact with the sample. The beam undergoes total internal reflection within the crystal, generating an evanescent wave that extends into the sample and interacts with its molecular components, thereby producing the characteristic absorption spectrum [11]. This method has revolutionized FTIR analysis in drug development by enabling rapid screening of raw materials, monitoring of chemical reactions, and characterization of biological samples with minimal manipulation.

Quantitative Analysis Using FTIR

Beyond qualitative identification, FTIR spectroscopy serves as a powerful quantitative technique based on the Beer-Lambert Law, which establishes a linear relationship between absorbance and analyte concentration [11]. According to this fundamental principle, absorbance (A) is equal to the molar absorptivity (ε) multiplied by the path length (l) and concentration (c): A = εlc [11]. This relationship enables researchers to construct calibration curves using standards of known concentration, which can then be applied to determine unknown concentrations in test samples.

The quantitative capabilities of FTIR are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications for verifying API concentration, assessing drug purity, monitoring reaction kinetics, and ensuring product consistency [9]. When combined with advanced chemometric methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, FTIR can extract meaningful quantitative information from complex biological spectra, enabling researchers to detect subtle biochemical changes in cells and tissues in response to therapeutic interventions [9] [13]. These multivariate analysis techniques are essential for interpreting the complex spectral patterns obtained from biological systems, allowing for the identification of specific biomarkers and the classification of samples based on their spectral signatures.

Application Protocols in Drug Development Research

Protocol 1: Predicting Immunotherapy Response in NSCLC Patients

The application of FTIR spectroscopy in predicting treatment response represents a cutting-edge protocol in personalized oncology. Recent research has demonstrated the utility of FTIR analysis of liquid biopsies for predicting response to first-line immunotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Plasma samples from NSCLC patients before treatment initiation

- Calcium fluoride (CaF₂) or barium fluoride (BaF₂) IR-transmissible windows

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for sample dilution if necessary

- FTIR spectrometer with liquid sample holder

- Software for multivariate analysis (PCA, ROC, decision tree algorithms)

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect plasma samples from NSCLC patients before initiation of immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy treatment

- Sample Preparation: Apply approximately 5-10 µL of plasma to IR-transmissible windows and allow to air dry under controlled conditions

- Spectral Acquisition: Acquire FTIR spectra in the range of 800-1800 cm⁻¹ using transmission mode with the following parameters:

- Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹

- Scans: 128-256 per sample

- Background scans: 64-128

- Data Processing:

- Apply vector normalization to all spectra

- Perform baseline correction

- Conduct second derivative processing to enhance spectral resolution

- Multivariate Analysis:

- Utilize Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify patterns in spectral data

- Apply Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis to evaluate diagnostic performance

- Implement decision tree algorithms to identify key wavenumbers for differentiation

- Validation: Compare spectral findings with clinical response data to establish correlation between spectral markers and treatment outcomes

Key Findings: This protocol successfully identified specific wavenumbers that distinguish long-term from short-term responders to immunotherapy. Notably, absorption bands around 1750 cm⁻¹ and 1539 cm⁻¹ were particularly discriminative before treatment, while bands at 1750 cm⁻¹ and 1080 cm⁻¹ showed differentiation after initial treatment response evaluation [13]. The Area Under Curve ROC (AUC-ROC) analysis confirmed a high probability of accurately differentiating patient response groups, highlighting the potential of FTIR spectroscopy as a predictive tool in clinical oncology.

Protocol 2: Cellular Response to Chemotherapeutic Agents

FTIR spectroscopy provides a powerful label-free approach for monitoring cellular responses to drug treatments, offering insights into biochemical changes at the molecular level. The following protocol outlines the methodology for assessing drug efficacy and cellular response using FTIR spectroscopy [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Renal carcinoma cell lines (e.g., CAKI-2, A-498)

- Chemotherapeutic agents (5-fluorouracil, novel gold-based compounds)

- Cell culture media and supplements

- IR-reflective slides or ATR crystal

- Fixation reagents (e.g., methanol, formalin) if required

- FTIR spectrometer with microscope capability

- RMieS-EMSC correction algorithm software

Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Culture:

- Maintain renal carcinoma cell lines under standard culture conditions

- Plate cells at appropriate density and allow to adhere for 24 hours

- Drug Treatment:

- Treat cells with chemotherapeutic agents at various concentrations

- Include vehicle controls for comparison

- Incubate for predetermined time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours)

- Sample Preparation:

- Harvest cells using gentle enzymatic or mechanical dissociation

- Wash cells with phosphate-buffered saline to remove media contaminants

- For ATR-FTIR: Deposit cell suspension directly onto ATR crystal and air dry

- For transmission FTIR: Spot cells onto IR-transparent windows and fix if necessary

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire spectra in mid-infrared range (4000-800 cm⁻¹)

- Use high resolution (2-4 cm⁻¹) for detailed spectral features

- Collect multiple spectra from different areas for statistical robustness

- Spectral Processing:

- Apply RMieS-EMSC algorithm to correct for resonant Mie scattering effects

- Perform baseline correction and normalization

- Conduct second derivative analysis to resolve overlapping bands

- Multivariate Analysis:

- Utilize Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify spectral patterns associated with drug response

- Employ Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to classify response groups

- Identify specific biochemical changes (lipids, proteins, nucleic acids) associated with treatment

Key Applications: This protocol has demonstrated the ability to detect discrete chemical differences within cell populations in response to chemotherapeutic agents, including novel gold-based compounds [14]. The technique can identify specific biochemical changes associated with drug efficacy, including alterations in protein structure, lipid composition, and nucleic acid content. Furthermore, the combination of FTIR with multivariate analysis has shown concordance with conventional biological assays while providing additional molecular insights into drug mechanisms of action.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of FTIR protocols in drug development research requires specific reagents and materials optimized for spectroscopic applications. The following table details essential components of the FTIR research toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FTIR Spectroscopy in Drug Development

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Substrates [11] | Potassium bromide (KBr) crystals, Calcium fluoride (CaF₂) windows, Diamond ATR crystals | Provide IR-transparent media for sample presentation; diamond ATR offers durability for diverse samples |

| Cell Culture & Treatment [14] | Cell lines (CAKI-2, A-498), Chemotherapeutic agents (5-fluorouracil), Cell culture media | Enable investigation of cellular response to therapeutics; provide model systems for drug screening |

| Clinical Samples [13] | Plasma/serum samples, Liquid biopsy collections | Serve as non-invasive source for biomarker detection and treatment response monitoring |

| Spectral Correction Tools [14] | RMieS-EMSC algorithm software, Baseline correction algorithms | Correct for light scattering artifacts in biological samples; improve spectral quality and interpretation |

| Data Analysis Software [9] [13] | PCA, OPLS-DA, ROC analysis tools, Decision tree algorithms | Enable multivariate analysis of complex spectral data; facilitate sample classification and biomarker identification |

| Reference Standards | Polystyrene films, Cyclohexane vapor, Rare earth oxide glasses | Provide wavelength calibration and instrument performance verification; ensure data quality and reproducibility |

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research

Clinical Diagnostics and Biomarker Discovery

FTIR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for clinical diagnostics, offering rapid, non-invasive approaches for disease detection and monitoring. Recent advances have demonstrated its utility in distinguishing pathological conditions based on spectral signatures derived from biofluids such as blood, saliva, and urine [9]. For example, researchers have successfully employed portable FTIR systems combined with pattern recognition analysis to diagnose fibromyalgia syndrome (FM) and differentiate it from other rheumatologic disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), osteoarthritis (OA), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with high sensitivity and specificity (Rcv > 0.93) [9]. The identified biomarkers primarily involved peptide backbones and aromatic amino acids, highlighting the ability of FTIR to detect specific molecular alterations associated with disease states.

The application of FTIR in oncology has expanded significantly, with researchers utilizing the technique to analyze lipid components in human cells, including various phospholipids and sphingolipids that play crucial roles in cellular processes such as membrane formation, cell adhesion, and response to DNA damage [9]. By establishing reference spectra for lipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and sphingomyelin (SM), researchers have created foundational databases that enable the investigation of lipid alterations in diseased cells or those exposed to various environmental factors, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [9].

Pharmaceutical Analysis and Drug Screening

FTIR spectroscopy plays multiple roles in pharmaceutical development, from initial drug discovery to final product quality control. The technique's ability to provide molecular structural information quickly and with minimal sample preparation makes it ideal for high-throughput screening applications. Portable FTIR systems have been successfully deployed as part of analytical toolkits for screening pharmaceutical products and dietary supplements, enabling the identification of over 650 active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) including more than 200 unique compounds [9]. These portable systems have demonstrated performance comparable to full-service laboratories when multiple devices are used for confirmation, highlighting their potential for field-based pharmaceutical analysis.

In drug development, FTIR spectroscopy has been utilized to investigate protein dynamics through amide hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange studies, providing insights into protein structural changes in response to mutations, interactions with metal ions, or ligand binding [9]. While this approach is most effective for monitoring dynamics occurring over minutes to hours and is considered semi-quantitative due to potential interference from experimental conditions, it nevertheless offers a valuable method for probing protein behavior under various physiological and pharmaceutical conditions [9]. Additionally, the combination of FTIR with molecular docking analyses has enabled researchers to study drug-receptor interactions, as demonstrated in studies of 2-Hydroxy-5-nitrobenzaldehyde (2H5NB), which showed strong binding affinity and significant hydrogen bond formation with receptor proteins, suggesting its potential as an analeptic agent [9].

FTIR spectroscopy represents a versatile and powerful analytical technique that seamlessly bridges the gap between raw interferogram data and actionable spectral information critical for drug development and clinical research. The Fourier transform algorithm serves as the mathematical engine that converts complex interference patterns into detailed molecular fingerprints, enabling researchers to extract meaningful biochemical information from diverse sample types. The continued refinement of sampling techniques, particularly ATR-FTIR, has simplified sample preparation while expanding application possibilities across pharmaceutical and clinical domains.

The integration of FTIR spectroscopy with advanced multivariate analysis methods and machine learning algorithms has further enhanced its utility in modern drug development, enabling the identification of subtle spectral patterns associated with disease states, treatment responses, and cellular alterations. As evidenced by the protocols presented herein, FTIR has established itself as a valuable tool for predicting patient responses to immunotherapy, screening chemotherapeutic agents, diagnosing complex medical conditions, and ensuring pharmaceutical quality. Ongoing advancements in portable instrumentation, computational algorithms, and spectral databases promise to further expand the applications of FTIR spectroscopy in personalized medicine and drug development, solidifying its position as an indispensable technique in the researcher's analytical arsenal.

Within the framework of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy research, interpreting an infrared (IR) spectrum is a fundamental skill for determining the molecular structure of an unknown compound. FTIR spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb specific frequencies of infrared light that correspond to the natural vibrational frequencies of their chemical bonds [4] [15]. The resulting spectrum is a plot of absorbance (or transmittance) against wavenumber (cm⁻¹), providing a unique molecular "fingerprint" [16]. This application note provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured protocol for the efficient identification of common organic functional groups, leveraging the speed, sensitivity, and non-destructive nature of FTIR analysis [7] [4].

Core Principles of IR Spectral Interpretation

When IR radiation interacts with a sample, energy is absorbed to excite vibrational modes, such as stretching and bending, provided there is a net change in the dipole moment of the molecule [4] [15]. The mid-IR region (4000 - 400 cm⁻¹) is most useful for organic structure determination because the absorption bands in this region can be correlated to specific functional groups [15] [16]. A key to successful interpretation is understanding that while the presence of a band can suggest a functional group, its exact position is influenced by the molecular environment [17] [18].

A critical concept is the division of the IR spectrum into two primary areas: the functional group region (approximately 4000 - 1500 cm⁻¹) and the fingerprint region (1500 - 500 cm⁻¹) [16]. The functional group region contains absorptions from key stretching vibrations (e.g., O-H, C=O, N-H) and provides the most direct evidence for the presence of major functional groups. The fingerprint region, in contrast, arises from complex combinations of bending and single-bond stretching vibrations; it is unique to each molecule and is best used for direct comparison with reference spectra [16].

Characteristic Wavenumbers of Common Functional Groups

The following tables summarize the characteristic IR absorption bands for major classes of organic functional groups, serving as a primary reference for spectral analysis [17] [16].

Table 1: Characteristic IR Stretching Frequencies for Common Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Bond | Wavenumber Range (cm⁻¹) | Peak Shape & Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | O-H | 3230 - 3550 | Broad, Strong [16] |

| Carboxylic Acid | O-H | 2500 - 3300 | Very Broad, Strong [16] |

| Amine | N-H | 3200 - 3500 | Sharp to Broad, Medium [17] |

| Alkyne | ≡C-H | 3270 - 3330 | Sharp, Medium [17] |

| Alkane/Aromatic | C-H | 2850 - 3300 | Sharp, Medium to Strong [17] [16] |

| Nitrile | C≡N | 2200 - 2300 | Sharp, Medium [16] |

| Alkyne | C≡C | 2100 - 2260 | Sharp, Variable [17] |

| Carbonyl (General) | C=O | 1630 - 1815 | Sharp, Very Strong [16] |

| Aldehyde | C=O | 1720 - 1740 | Sharp, Very Strong [17] |

| Ketone | C=O | 1705 - 1720 | Sharp, Very Strong [17] |

| Carboxylic Acid | C=O | 1710 - 1760 | Sharp, Very Strong [16] |

| Ester | C=O | 1735 - 1750 | Sharp, Very Strong [16] |

| Amide | C=O | 1620 - 1670 | Sharp, Very Strong [16] |

| Alkene | C=C | 1620 - 1680 | Sharp, Variable [17] |

| Aromatic | C=C | 1550 - 1700 | Sharp, Variable [16] |

Table 2: Characteristic IR Bending Frequencies and Other Key Bands

| Functional Group | Vibration Mode | Wavenumber Range (cm⁻¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkane | C-H Bend | 1370-1470 | [17] |

| Alkene | =C-H Bend | 650 - 1000 | [17] |

| Aromatic | C-H "OOP" | 675 - 900 | Strong evidence for substitution pattern [17] [16] |

| Alcohol, Ether, Ester | C-O Stretch | 1000 - 1300 | Strong, often complex bands [16] |

| Amine | N-H Bend | 660 - 900 | [16] |

| Primary Amine | N-H Bend | 1500 - 1650 | [16] |

Strategic Interpretation of IR Spectra

Confronted with a complex IR spectrum, a systematic approach prevents overwhelm. The "hunt and peck" method of assigning every single peak is inefficient and unnecessary [19]. Instead, a prioritized strategy focusing on the most telling features is recommended.

The "First-Look" Protocol: Identifying Tongues and Swords

The most efficient initial analysis involves inspecting two high-yield spectral regions, often described as looking for "tongues" (broad O-H/N-H peaks) and "swords" (sharp C=O peaks) [19].

- The "Tongue" (3300 - 3500 cm⁻¹): Look for a broad, rounded absorption in this region, which is characteristic of the O-H stretch in alcohols and the N-H stretch in amines. Carboxylic acids (O-H) display an even broader absorption that often extends from 3500 down to 2500 cm⁻¹, described as a "hairy beard" [19] [16].

- The "Sword" (1630 - 1800 cm⁻¹): Look for a sharp, strong peak in this region, which is the unmistakable signature of the carbonyl (C=O) stretch. This is often the strongest peak in the entire spectrum [19].

The workflow below outlines this strategic approach to interpreting a spectrum.

Supplementary Spectral Regions

After checking for "tongues" and "swords," the following regions provide supporting evidence [19]:

- The 3000 cm⁻¹ Divide: The C-H stretching region around 3000 cm⁻¹ acts as a useful boundary. Absorptions just above 3000 cm⁻¹ indicate unsaturated (=C-H or aromatic C-H) sp² carbon, while those below 3000 cm⁻¹ are typical of saturated (-C-H) sp³ carbon [19].

- The Triple-Bond Region (2050 - 2260 cm⁻¹): Sharp, often weak peaks in this region indicate the presence of triple bonds, such as nitriles (C≡N) or alkynes (C≡C) [17] [19].

Experimental Protocol for FTIR Sample Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for FTIR Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Core instrument for spectral acquisition. Modern systems are typically FT-based for superior speed and sensitivity [7] [15]. |

| ATR Accessory (Diamond/ZnSe) | Enables direct analysis of solids, liquids, and gels with minimal sample prep via attenuated total reflectance [4]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | For preparing transparent pellets for transmission analysis of solid samples [4]. |

| Solvent Reagents (e.g., CHCl₃, ACN) | High-purity, anhydrous solvents for preparing liquid solution samples [4]. |

| Calibration Standards | Compounds like polystyrene for verifying instrument wavenumber accuracy [4]. |

| Nitrogen Purge Gas | Dry, CO₂-free gas to purge the optical path and minimize atmospheric water vapor and CO₂ interference [4]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow for Solid Sample Analysis via ATR

The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for analyzing a solid sample using a Diamond ATR accessory, one of the most common and convenient methods.

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Turn on the FTIR spectrometer and allow it to initialize. Initiate a purge with dry nitrogen for at least 10-15 minutes to reduce spectral interference from atmospheric water vapor and CO₂ [4].

- ATR Crystal Cleaning: Clean the diamond ATR crystal thoroughly. Apply a few drops of a volatile, pure solvent (e.g., methanol or isopropanol) to the crystal and wipe dry with a lint-free tissue. Repeat if necessary.

- Background Acquisition: With the clean crystal exposed and the pressure tip raised, collect a background (or reference) single-beam spectrum. This step records the instrument and environmental response, which will be subtracted from the sample spectrum [4].

- Sample Loading: Place a small amount of the solid sample (typically 1-5 mg) directly onto the center of the ATR crystal. For hard powders, creating a fine powder can improve contact.

- Sample Clamping: Lower the pressure clamp onto the sample until it clicks or a defined torque is reached. This ensures intimate contact between the sample and the crystal, which is critical for a strong, reproducible signal.

- Spectral Collection: Collect the sample spectrum. Standard parameters are 4 cm⁻¹ resolution and 16-32 scans, which provide a good signal-to-noise ratio for most applications [4].

- Data Inspection and Pre-processing:

- Quality Check: Visually inspect the spectrum for a flat baseline and sufficient absorbance (e.g., strongest peak between 0.5 and 1.0 Absorbance Units).

- Baseline Correction: Apply a baseline correction algorithm (e.g., linear, concave rubber band) to correct for any scattering effects and ensure the baseline returns to zero [15].

- Atmospheric Subtraction: If residual CO₂ or water vapor peaks are present, use the software's atmospheric correction function.

- Smoothing: If the spectrum is noisy, apply mild smoothing (e.g., Savitzky-Golay filter) [15].

- Analysis and Interpretation: Follow the strategic interpretation protocol outlined in Section 4 to identify the functional groups present in the sample.

Proficiency in IR spectral interpretation is achieved not by memorizing every peak but by mastering a systematic strategy that prioritizes high-information regions. The combination of the "tongues and swords" first-look protocol with a rigorous experimental methodology using modern FTIR spectrometers provides researchers in drug development and material science with a powerful, non-destructive tool for rapid molecular characterization. This structured approach to understanding wavenumbers, absorbance, and functional groups forms an essential component of a comprehensive analytical research thesis.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful analytical tool in medical and pharmaceutical research, offering non-invasive and precise examination of the molecular composition of biological samples. This technique operates on the fundamental principle that molecules continuously undergo vibrational motions and can absorb infrared radiation at frequencies matching their natural vibrational frequencies. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, chemical bonds within the molecules absorb specific wavelengths, resulting in vibrational transitions that include stretching (rhythmic changes in bond lengths) and bending (alterations in bond angles). The resulting absorption spectrum provides a unique "molecular fingerprint" that enables researchers to identify biochemical structures, functional groups, and compositional changes critical to drug development and diagnostic applications.

The primary objective of this application note is to delineate the relationship between molecular vibrations and FTIR spectral characteristics within the broader context of FTIR analysis research. We emphasize the technique's capability to elucidate cellular and molecular processes, facilitate disease diagnostics, and enable treatment monitoring—functions particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals. By providing detailed protocols and comprehensive data analysis frameworks, this document serves as an essential resource for leveraging FTIR spectroscopy in pharmaceutical development and clinical research settings, where understanding molecular-level interactions is paramount for innovation.

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Vibrations

Theoretical Framework of Stretching and Bending Vibrations

Molecular vibrations in FTIR spectroscopy are primarily categorized into stretching and bending motions, each with distinct energy requirements and spectral signatures. Stretching vibrations involve rhythmic changes in the interatomic distance between two bonded atoms along the bond axis, while bending vibrations encompass changes in bond angles between multiple bonds connected to a central atom. These vibrational modes occur at specific resonance frequencies that depend on the bond strength and atomic masses, following Hooke's Law for molecular vibrations.

The absorption of infrared radiation is governed by specific selection rules, primarily requiring a net change in the dipole moment of the molecule during vibration. This fundamental requirement means that heteronuclear functional groups (with intrinsically polar bonds) typically produce strong IR signals, while homonuclear diatomic molecules like N₂ or O₂ are IR-inactive. The frequency of absorption (measured in wavenumbers, cm⁻¹) directly correlates with bond strength and atomic masses, with stronger bonds and lighter atoms absorbing at higher wavenumbers. This relationship forms the theoretical basis for interpreting FTIR spectra and assigning observed peaks to specific molecular vibrations within complex biological and pharmaceutical compounds.

Characteristic Vibrational Frequencies of Functional Groups

The following table summarizes characteristic FTIR absorption frequencies for common functional groups relevant to pharmaceutical compounds and biological samples, compiled from comprehensive databases and research findings [20] [21]:

Table 1: Characteristic FTIR Absorption Frequencies for Common Functional Groups

| Peak Position (cm⁻¹) | Vibration Type | Functional Group | Compound Class | Peak Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3584-3700 | O-H stretching (free) | O-H | Alcohol, phenol | Strong, sharp |

| 3200-3550 | O-H stretching (H-bonded) | O-H | Alcohol | Strong, broad |

| 2500-3300 | O-H stretching | O-H | Carboxylic acid | Very strong, very broad |

| 3300-3400 | N-H stretching | N-H | Aliphatic primary amine | Medium, sharp |

| 3000-3100 | C-H stretching | C-H | Aromatic hydrocarbon | Medium to weak |

| 2840-3000 | C-H stretching | C-H | Alkane | Medium |

| 2222-2260 | C≡N stretching | C≡N | Nitrile | Weak to medium, sharp |

| 1720-1740 | C=O stretching | C=O | Aldehyde | Strong, sharp |

| 1705-1725 | C=O stretching | C=O | Aliphatic ketone | Strong, sharp |

| 1735-1750 | C=O stretching | C=O | Esters | Strong, sharp |

| 1680-1690 | C=O stretching | C=O | Primary amide | Strong, sharp |

| 1668-1678 | C=C stretching | C=C | Alkene | Weak |

| 1610-1620 | C=C stretching | C=C | α,β-unsaturated ketone | Strong |

| 1580-1650 | N-H bending | N-H | Amine | Medium |

| 1500-1550 | N-O stretching | N-O | Nitro compound | Strong |

| 1330-1420 | O-H bending | O-H | Alcohol | Medium |

| 1000-1400 | C-F stretching | C-F | Fluoro compound | Strong |

| 1163-1210 | C-O stretching | C-O | Ester | Strong, sharp |

| 1050-1085 | C-O stretching | C-O | Primary alcohol | Strong, sharp |

| 960-980 | C=C bending | C=C | Alkene | Strong, sharp |

| 650-900 | C-H out-of-plane bending | C-H | Aromatic substitution | Medium to strong |

The "fingerprint region" (approximately 1800-800 cm⁻¹) is particularly significant for identifying specific compounds, as it contains complex absorption patterns resulting from coupled vibrations that are unique to each molecule [20]. This region enables discrimination between similar compounds and identification of subtle molecular changes in pharmaceutical formulations. Additionally, the position and shape of characteristic bands, such as the amide I (approximately 1590-1690 cm⁻¹) and amide II bands, provide insights into secondary protein structure, which is critical for understanding biopharmaceutical stability and conformation [20].

Experimental Protocols for FTIR Analysis

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality, reproducible FTIR spectra. The following protocols outline standardized methodologies for handling various sample types relevant to pharmaceutical and biomedical research:

Table 2: Sample Preparation Protocols for Different Biological Matrices

| Sample Type | Preparation Protocol | Critical Steps | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Samples (Fresh/Frozen) | 1. Cryosection tissue to 5-10μm thickness2. Mount on low-e slides or ATR crystal3. Air-dry or use N₂ flux for desiccation4. Verify complete drying via spectral preview | Dewaxing for FFPE samples using xylol | Check for residual water absorption (~1640 cm⁻¹) |

| Cell Cultures | 1. Wash cells with isotonic buffer2. Centrifuge and resuspend in saline3. Spot onto ATR crystal or IR-transparent window4. Air-dry to form homogeneous film | Minimum 3 washes to remove culture medium | Monitor protein-to-lipid ratio for consistency |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | 1. Grind solid samples to fine powder2. Mix with KBr (1:100 ratio) for transmission3. Compress into pellet under vacuum4. For ATR, apply powder directly to crystal | Uniform particle size distribution | Check for moisture-related artifacts |

| Biofluids (Serum, Plasma) | 1. Deposit 5-10μL aliquot on ATR crystal2. Employ gentle N₂ stream for controlled drying3. Form uniform protein film | Standardized deposition volume | Consistent film thickness via absorbance normalization |

A critical consideration across all biological samples is the complete removal of water, as water absorbs strongly in the mid-infrared region and can obscure important spectral features [20]. Previewing spectra during the drying process using ATR with the sample in contact with the crystal allows researchers to monitor for residual water and confirm when samples are adequately dried. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, samples must be dewaxed using xylol or xylene before spectral acquisition to remove paraffin contributions that would interfere with the biological signature [20].

FTIR Instrumentation and Measurement Techniques

FTIR spectroscopy offers multiple measurement modes, each with specific advantages for different sample types and analytical requirements. The selection of appropriate measurement technique is crucial for obtaining optimal results:

Table 3: Comparison of FTIR Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Principles | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) | Total internal reflection with evanescent wave penetration | Liquids, pastes, soft tissues, powders | Minimal sample preparation; small sample area; high resolution | Limited penetration depth (~0.5-2μm); crystal contact required |

| Transmission | IR beam passes directly through sample | Homogeneous solutions, KBr pellets, thin tissue sections | Quantitative accuracy; well-established protocols | Sample thickness critical; requires IR-transparent substrates |

| Transflection | IR radiation transmits through sample, reflects off substrate, transmits back through sample | Tissue sections on reflective surfaces | Higher absorbance (double path); less substrate required | Potential for electric field standing wave artifacts |

The ATR technique has gained significant popularity in pharmaceutical and biological applications due to its minimal sample preparation requirements and ability to handle a wide variety of sample types without extensive processing [20]. The technique operates on the principles of total internal reflection, where an IR beam entering a high-refractive-index crystal (typically germanium or zinc selenide) at an angle exceeding the critical angle experiences total internal reflection, generating an evanescent wave that penetrates the sample typically 0.5-2 micrometers [20]. The reflected attenuated radiation is detected and transformed into a conventional IR spectrum via Fourier transformation.

For all measurement techniques, proper instrument calibration and background collection are essential steps. Background spectra should be collected using the same parameters as sample measurement and under identical environmental conditions (particularly humidity) to minimize atmospheric contributions (especially CO₂ at 2349 cm⁻¹ and water vapor) in sample spectra [22].

Data Processing and Analysis Workflow

Spectral Pre-processing Protocols

Raw FTIR spectra require careful pre-processing to remove instrumental and environmental artifacts before biological interpretation. The following standardized protocol ensures data quality and analytical robustness:

Quality Assessment: Examine spectra for acceptable absorbance values (typically <1.2 AU for linear response), signal-to-noise ratio (>1000:1 for high-quality spectra), and minimal water vapor contributions [20].

Atmospheric Compensation: Subtract water vapor and CO₂ contributions using reference spectra or library functions within analysis software.

Baseline Correction: Apply polynomial or spline functions to correct for scattering effects, particularly important for heterogeneous biological samples.

Smoothing: Implement Savitzky-Golay or similar algorithms to reduce high-frequency noise while preserving spectral features.

Normalization: Utilize vector normalization or standard normal variate (SNV) to compensate for variations in sample thickness or concentration.

Derivative Processing: Apply second derivatives (typically Savitzky-Golay with 5-13 point window) to resolve overlapping bands and enhance spectral features.

The workflow for FTIR spectral analysis involves multiple steps from sample preparation to final interpretation, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Spectral Interpretation and Multivariate Analysis

The interpretation of FTIR spectra involves correlating observed absorption bands with specific molecular vibrations and functional groups. For biological samples, particular attention should be paid to key spectral regions:

Lipid Region (3050-2800 cm⁻¹): C-H stretching vibrations from methyl and methylene groups provide information on lipid content and acyl chain ordering [20].

Protein Region (1720-1480 cm⁻¹): Amide I (primarily C=O stretching, ~1650 cm⁻¹) and Amide II (C-N stretching and N-H bending, ~1550 cm⁻¹) bands reveal protein secondary structure and content [20].

Nucleic Acid Region (1270-1000 cm⁻¹): Asymmetric phosphate stretching (~1230-1240 cm⁻¹) and sugar-phosphate backbone vibrations indicate DNA/RNA content [20].

Carbohydrate Region (1200-950 cm⁻¹): Complex C-O-C and C-O-P vibrations provide information on glycogen and other carbohydrate content.

For complex biological mixtures, multivariate analysis techniques are essential for extracting meaningful information. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identifies major sources of variance in datasets, while Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) or Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) can develop classification models for disease diagnosis or treatment monitoring. Cluster analysis methods such as hierarchical clustering or k-means clustering enable identification of spectral patterns associated with different sample types or pathological states.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research

Disease Diagnosis and Biomarker Discovery

FTIR spectroscopy has demonstrated significant utility in disease diagnosis through detection of molecular alterations in biological samples. Research applications include:

Cancer Diagnostics: FTIR can discriminate between normal and malignant tissues based on characteristic changes in nucleic acid, protein, and lipid profiles [20]. Specific spectral patterns associated with increased DNA content (elevated phosphate vibrations), altered protein secondary structure, and changes in lipid composition serve as biomarkers for various cancers.

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Analysis of biological fluids and tissues reveals spectral signatures associated with protein aggregation and lipid peroxidation in conditions like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases.

Metabolic Disorders: FTIR analysis of biofluids detects molecular changes associated with diabetes, renal dysfunction, and other metabolic conditions through quantification of metabolites and proteins.

The technique's sensitivity to molecular-level alterations enables early disease detection, often before morphological changes become apparent through conventional histopathology. Furthermore, ATR-FTIR's capability for intraoperative assessment during surgery provides real-time diagnostic information to guide surgical interventions [20].

Pharmaceutical Quality Control and Drug Development

In pharmaceutical research and development, FTIR spectroscopy serves multiple critical functions:

Raw Material Verification: Rapid identification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients through spectral fingerprint matching.

Formulation Analysis: Assessment of drug-polymer interactions in solid dispersions, polymorph characterization, and monitoring of stability studies.

Counterfeit Drug Detection: Identification of substandard or falsified pharmaceutical products through spectral comparison with authentic references [20].

Drug Permeation Studies: Monitoring of drug transport across biological membranes using ATR-FTIR with flow-through cells.

The minimal sample preparation, rapid analysis time, and non-destructive nature of FTIR analysis make it particularly valuable for quality control applications in pharmaceutical manufacturing and regulatory compliance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful FTIR analysis requires specific reagents and materials optimized for infrared spectroscopy. The following table details essential components of the FTIR toolkit for biological and pharmaceutical applications:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FTIR Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes | Quality Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe, Ge) | Provides internal reflection element for sample contact | Diamond: most durable; ZnSe: general purpose; Ge: high refractive index | High refractive index (>2.0); chemical inertness |

| IR-Transparent Windows (CaF₂, BaF₂, KBr) | Sample substrate for transmission measurements | CaF₂: durable to aqueous solutions; BaF₂: broader range; KBr: low-cost disposable | High transmission across IR range; appropriate solubility resistance |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for powder pellet preparation | FTIR grade, purified to minimize moisture and spectral artifacts | >99% purity; desiccated storage required |

| NIST Traceable Standards | Instrument performance validation | Polystyrene films for wavelength accuracy; blackbody sources for intensity | Certified reference materials with uncertainty quantification [22] |

| Desiccating Materials | Moisture control during sample prep | N₂ purge systems, desiccators with Drierite | Low water vapor background; minimal CO₂ interference |

| Bio-Sample Collection Kits | Standardized biological sampling | Low-e slides, IR-compatible fixatives | Certified nucleic acid-, protein-, and lipid-free |

| Spectral Libraries | Compound identification reference | Commercial and custom databases of pure compounds | Annotated with peak assignments and experimental conditions [21] |

Proper maintenance of this toolkit is essential for reproducible FTIR results. ATR crystals require regular cleaning with appropriate solvents and verification of optical integrity. Hygroscopic materials like KBr must be stored in controlled environments with minimal humidity, and certification documents should be maintained for all reference standards.

FTIR spectroscopy provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful analytical platform for investigating molecular vibrations through stretching and bending modes that create unique spectral signatures. The detailed protocols and application guidelines presented in this document enable comprehensive molecular analysis of biological and pharmaceutical samples, from initial sample preparation through advanced multivariate data analysis. The technique's sensitivity to biochemical composition, molecular structure, and intermolecular interactions makes it invaluable for pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and biomedical research.

As FTIR technology continues to evolve with advancements in focal plane array detectors, synchrotron radiation sources, and computational analysis methods, its applications in drug development and clinical research are expected to expand significantly. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches with FTIR spectral analysis promises to further enhance its capabilities for high-throughput screening, precision medicine, and personalized therapeutic development. By mastering the fundamental principles and experimental protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can leverage the full potential of FTIR spectroscopy to advance pharmaceutical innovation and improve patient care through molecular-level understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique that characterizes molecules based on their absorption of infrared light. The technique's versatility stems from its ability to operate across different spectral ranges, primarily the Near-IR, Mid-IR, and Far-IR, each providing unique insights into molecular structure and composition. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate spectral range is a critical decision that directly impacts the quality and applicability of analytical data. This selection depends on multiple factors, including the sample type, the molecular information required, and the specific analytical question being addressed. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these spectral ranges, supported by experimental protocols and decision frameworks, to guide scientists in optimizing their FTIR analysis within the context of modern pharmaceutical and materials research.

Technical Comparison of IR Spectral Ranges

The infrared spectrum is divided into three primary regions based on wavelength and the type of molecular vibrations they probe. Each range offers distinct advantages and is suited to specific applications, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and applications of each spectral range.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Near-IR, Mid-IR, and Far-IR Spectral Ranges

| Parameter | Near-IR (NIR) | Mid-IR (MIR) | Far-IR (FIR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 12,800 - 4,000 cm⁻¹ [23] [24] | 4,000 - 400 cm⁻¹ [23] [24] | 500 - 10 cm⁻¹ [25] [26] |

| Primary Transitions | Overtone and combination bands of fundamental vibrations (C-H, N-H, O-H) [27] | Fundamental molecular vibrations (functional groups) [9] [28] | Skeletal vibrations, lattice modes, hydrogen bonding, inorganic bonds [28] [25] |

| Information Obtained | Chemical and physical properties (e.g., moisture, protein, fat) [28] [27] | Molecular "fingerprint" for identification and structure [9] [23] | Low-frequency molecular interactions, crystalline structure [28] [25] |

| Penetration Depth | High (suitable for bulk analysis) [27] | Low (surface-sensitive with ATR) [26] | Variable, depends on technique [25] |

| Sample Throughput | High (rapid, non-destructive) [28] [27] | Moderate to High [9] | Lower (often requires synchrotron for high-quality data) [25] |

| Key Pharmaceutical Applications | Raw material ID, blend uniformity, moisture content, content uniformity [23] [24] [27] | API polymorphism, drug-excipient compatibility, identity testing, degradation studies [9] [23] [24] | Polymorph characterization, crystalline structure analysis [28] |

Guide to Spectral Range Selection

The following decision diagram outlines the logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate IR spectral range based on analytical goals and sample properties.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Drug-Excipient Compatibility Screening Using Mid-IR ATR-FTIR

Objective: To identify potential incompatible interactions between an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and excipients using Mid-IR spectroscopy, a critical step in formulation design [23] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Drug-Excipient Compatibility Screening

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Must be equipped with a Mid-IR source and ATR accessory. | e.g., Bruker, Thermo Fisher, PerkinElmer [27] |

| Diamond ATR Crystal | Durable, chemically resistant crystal for analyzing solid and semi-solid samples. | e.g., Specac Golden Gate [23] [26] |

| High-Temperature ATR Accessory | Allows for temperature ramping to study polymorphic conversions. | e.g., Golden Gate High-Temperature ATR [23] [24] |

| API & Excipients | High-purity materials for reliable compatibility assessment. | Pharmaceutical Grade |

| Hydraulic Press | Used to ensure good contact between powder samples and the ATR crystal. | Lab-scale press |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Individually prepare pure samples of the API and each excipient.

- Prepare physical mixtures (e.g., 1:1 ratio) of the API with each excipient.

- For stress testing, place individual and mixture samples in stability chambers at elevated temperature and humidity (e.g., 40°C/75% RH) for defined periods [24].

Instrument Setup:

- Configure the FTIR spectrometer for Mid-IR range collection (4000-400 cm⁻¹).

- Ensure the diamond ATR crystal is clean. Perform a background scan with a clean crystal.

- Set parameters: resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, 32 scans per spectrum to ensure a good signal-to-noise ratio [23].

Data Acquisition:

- Place a small amount of each pure and mixture sample (stressed and unstressed) onto the ATR crystal.

- Use a hydraulic press to apply consistent pressure to the sample, ensuring good crystal contact.

- Collect the absorbance spectrum for each sample.

Data Analysis:

- Overlay the spectrum of the physical mixture with the summed spectra of the pure API and pure excipient.

- Identify any significant spectral changes, such as peak shifts, appearance of new peaks, or disappearance of existing peaks in the mixture, which indicate molecular interactions [23] [24].

- For example, a study using ATR-FTIR identified that levodopa is incompatible with many common excipients by observing such spectral shifts [23] [24].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Blend Uniformity Using Near-IR Spectroscopy

Objective: To perform non-destructive, rapid quantification of API concentration and homogeneity in a powder blend, a critical quality attribute in solid dosage manufacturing [23] [24] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for NIR Blend Uniformity Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Portable/Held NIR Spectrometer | Enables at-line or in-line analysis in the manufacturing area. | e.g., Foss, Thermo Fisher [27] |

| DRIFTS Accessory | Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy accessory for analyzing powders. | Optional, depending on instrument design [23] [24] |

| Reference Standards | Calibration blends with known, precise API concentrations. | Prepared in-house with certified API and excipients |

| Chemometric Software | For building quantitative models (PLS) and spectral analysis. | e.g., Bruker OPUS, Thermo Fisher TQ Analyst |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Calibration Model Development:

- Prepare a set of calibration samples spanning the expected API concentration range (e.g., 70% to 130% of target).

- Using the NIR spectrometer, collect spectra from multiple locations for each calibration blend.

- Using chemometric software, develop a Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression model that correlates the spectral data to the known API concentrations [9] [27].

Validation:

- Validate the PLS model using a separate set of validation samples not used in calibration.

- Assess model performance using parameters like Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and R² to ensure accuracy and robustness [9].

At-Line Blend Testing:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean API concentration, standard deviation, and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) across all sampling points.

- Blend uniformity is typically considered acceptable if the RSD is below a pre-defined limit (e.g., 5%), and all individual results are within a specified range of the target concentration [23].

Protocol 3: Differentiating Plant Exudates Using Combined Mid- and Far-IR Spectroscopy

Objective: To leverage the complementary nature of Mid- and Far-IR spectroscopy for the precise discrimination of complex natural materials, such as plant exudates used as pigment binders in cultural heritage analysis [25].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Apply minimal preparation to preserve sample integrity. For solid exudates (gums, resins), a small flake can be placed directly on the ATR crystal.

Instrument Setup and Data Acquisition:

- Mid-IR Analysis: Collect spectra in the 4000-400 cm⁻¹ range using a standard diamond ATR accessory. This provides data on functional groups (e.g., O-H, C=O) [25].

- Far-IR Analysis: Collect spectra in the far-IR region (e.g., below 500 cm⁻¹). This may require a synchrotron light source for high-quality data on lattice vibrations and skeletal motions [25]. Use an extended range diamond ATR crystal, which is suitable for far-IR measurements down to 10 cm⁻¹ [26].

Data Analysis:

- Integrate the spectral datasets from both ranges.

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), on the combined dataset.

- The Mid-IR data will differentiate samples based on functional group chemistry, while the Far-IR data provides additional discrimination based on low-energy molecular interactions. The combination allows for classification at both the genus and species level, which is not easily achievable using Mid-IR alone [25].

Selecting the correct spectral range in FTIR spectroscopy is not a one-size-fits-all decision but a strategic choice that directly influences the success of an analytical method. The Mid-IR range is the unequivocal choice for detailed molecular fingerprinting and structural elucidation, making it indispensable for identity testing, polymorphism studies, and compatibility screening in pharmaceutical development. The Near-IR range excels in rapid, non-destructive quantitative analysis of physical and chemical properties, ideal for high-throughput quality control applications like blend uniformity and moisture content. The Far-IR range, though more specialized, provides unique insights into low-frequency vibrations and is a powerful tool for characterizing crystalline structures and inorganic compounds.

The ongoing integration of FTIR with advanced data processing techniques like machine learning and the development of portable, robust instruments are making these analytical capabilities more accessible and powerful than ever [9] [28] [27]. By applying the principles and protocols outlined in this application note, researchers and scientists can make informed decisions to harness the full potential of FTIR spectroscopy, thereby accelerating drug development and ensuring product quality and safety.

Advanced FTIR Methods and Transformative Applications Across Industries

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy is a cornerstone analytical technique in modern research and industrial laboratories, providing critical insights into molecular structure through the excitation of vibrational modes. The core principle of FT-IR involves the absorption of infrared light by chemical bonds, which vibrate at characteristic frequencies, creating a unique "chemical fingerprint" for each compound [3]. The analytical value of FT-IR spectroscopy, however, is profoundly influenced by the sampling method employed. Choosing the correct technique is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental decision that affects data quality, interpretability, and analytical throughput [4].

This application note provides a detailed examination of the three primary FT-IR sampling techniques: Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR), Transmission, and Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS). Each method possesses distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal application domains. We frame this technical deep dive within the broader context of FT-IR analysis research, offering researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals structured protocols, comparative data, and practical workflows to guide method selection and implementation.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

The interaction between infrared light and the sample differs fundamentally across the three main sampling techniques. Transmission, the original method, involves passing IR light directly through a prepared sample [3]. Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) relies on an evanescent wave that penetrates a few microns into a sample in contact with a high-refractive-index crystal [4] [3]. Diffuse Reflectance (DRIFTS), in contrast, collects scattered infrared radiation from powdered or rough-surface samples [29].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, enabling direct comparison for informed method selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ATR, Transmission, and DRIFTS Techniques

| Parameter | ATR | Transmission | DRIFTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Evanescent wave absorption at crystal-sample interface [3] | Direct absorption of light passing through the sample [3] | Collection of diffusely scattered light from rough surfaces [29] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; often direct placement on crystal [3] | Extensive (grinding, pelleting with KBr, or microtomy) [30] [3] | Moderate (grinding and dilution in non-absorbing matrix like KBr) [29] |

| Typical Sample Types | Solids, liquids, gels, polymers [4] | Thin films, gases, KBr pellets, microtomed sections [4] [30] | Powders, rough solids, catalysts, soils [4] [29] |

| Destructive/Non-Destructive | Generally non-destructive [3] | Often destructive (due to preparation) [3] | Non-destructive [29] |

| Penetration Depth | Shallow (typically 0.5 - 5 µm) [4] | Variable, controlled by pathlength or thickness | Several microns, depends on particle size and packing [29] |

| Pathlength/Thickness Control | Fixed by crystal and wavelength | Critical and requires precise preparation [30] | Managed via dilution and packing density [29] |

| Ideal For | Rapid quality control, heterogeneous catalysts, biomaterials [4] [29] | Microspectroscopy (e.g., microplastics, tissues), gas analysis [4] [30] | In-situ catalytic studies, mineral analysis, pharmaceutical powders [4] [29] |

Detailed Techniques, Protocols, and Applications

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)

ATR has become the most prevalent sampling technique in many laboratories due to its minimal sample preparation and versatility. It is particularly powerful in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, such as the rapid analysis of blood lipids for metabolic syndrome screening [31].

Experimental Protocol: Liquid Sample Analysis (e.g., Blood Serum)

- Crystal Preparation: Clean the ATR crystal (commonly diamond) with a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol) and soft cloth. Ensure the crystal is completely dry before use [31].

- Background Acquisition: Collect a background spectrum with the clean crystal exposed to air. This corrects for atmospheric absorption and crystal properties.

- Sample Application: Pipette a small volume (e.g., 0.5 µL) of the blood serum sample directly onto the crystal [31].

- Drying: Allow the sample's moisture to evaporate naturally at room temperature to prevent spectral interference from water bands (e.g., ~1640 cm⁻¹ and ~3500 cm⁻¹) [31].

- Spectral Acquisition: Place the sample on the crystal, ensure good contact, and collect the spectrum. Typical parameters are 4 cm⁻¹ resolution and 16-32 scans [4].

- Data Processing: Apply an ATR correction algorithm in the instrument software to compensate for wavelength-dependent penetration depth, enabling library matching [3].

Transmission FT-IR

Transmission remains a vital technique, especially in FT-IR microscopy for analyzing small, spatially resolved particles. Success hinges on preparing a sample thin enough to avoid total absorption, typically between 10–50 µm [30].

Experimental Protocol: Transmission Microscopy of a Polymer Fiber

- Sample Isolation: Use needle probes or tweezers to isolate a single fiber from its matrix [30].