Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) for Analytical Chemists: A Practical Guide to Compliance, Methods, and Data Integrity

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) specifically for analytical and bioanalytical chemists involved in drug development.

Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) for Analytical Chemists: A Practical Guide to Compliance, Methods, and Data Integrity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) specifically for analytical and bioanalytical chemists involved in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of GLP as a quality system for nonclinical safety studies, detailing the roles of chemists in method development, sample analysis, and data management. The content explores practical applications, including techniques like HPLC and LC-MS, addresses common troubleshooting challenges in peptide analysis and data silos, and outlines the rigorous requirements for method validation and compliance with FDA (21 CFR Part 58) and OECD standards. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes regulatory expectations with practical laboratory strategies to ensure data quality, integrity, and regulatory acceptance.

Understanding GLP: The Quality Framework for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies

Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) is a quality system framework governing the organizational processes and conditions under which nonclinical laboratory studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, reported, and archived [1]. Established to ensure the quality and integrity of safety test data, GLP provides regulatory agencies with reliable, reproducible, and auditable evidence to support the approval of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and other products [2] [3].

For analytical chemists, GLP is distinct from, yet complementary to, other quality systems. While Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) ensures quality in production and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) governs human clinical trials, GLP specifically focuses on preclinical safety testing [4] [1]. Its fundamental purpose is not to assess the scientific merit of a study hypothesis but to verify that the process of data collection and handling is rigorous, consistent, and fully traceable [2]. In essence, GLP is “less about what you found and more about proving how you found it – cleanly, consistently, and under independent QA oversight” [2].

Historical Context and Regulatory Genesis

The formalization of GLP regulations was a direct response to widespread data integrity failures discovered in commercial testing laboratories during the 1970s [2] [5]. Prior to GLP, nonclinical safety studies were often plagued by insufficient quality control, leading to questions about the validity of data used to evaluate product safety.

The pivotal event that catalyzed regulatory action was the Industrial Bio-Test (IBT) Laboratories scandal [2] [3] [5]. IBT, a major contract research organization, was found to have fabricated and falsified safety data for numerous chemical manufacturers and the U.S. government. Investigations revealed that thousands of toxicology studies were scientifically unreliable, compromising the safety assessments of hundreds of products, from drugs to household items [5]. This breach of public trust prompted U.S. Congressional hearings and led the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to draft the first GLP regulations [5].

The FDA issued the final rule for 21 CFR Part 58 (Good Laboratory Practice for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies) in 1978, with the regulations becoming effective in 1979 [2] [3]. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) followed with its own GLP rules under FIFRA and TSCA in 1983 [2] [5]. This U.S. regulatory framework has since become part of a global standard, harmonized through the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which adopted GLP principles in 1992 to enable mutual acceptance of data among member countries [2] [3].

Scope and Applicability of GLP

Understanding the boundaries of GLP is critical for effective implementation. GLP applies specifically to nonclinical laboratory studies that support applications for research or marketing permits for products regulated by the FDA and other agencies [2] [6].

Table: Studies Requiring and Exempt from GLP Compliance

| GLP Compliance REQUIRED | GLP Compliance NOT REQUIRED |

|---|---|

| Standard repeated-dose toxicity studies [3] | Basic exploratory research [2] |

| Genotoxicity and carcinogenicity studies [4] [3] | Chemical method development [2] [1] |

| Safety pharmacology studies [3] | Analytical method validation trials [2] [1] |

| Reproductive and developmental toxicity studies [4] | Clinical trials on humans (governed by GCP) [2] [4] |

| Toxicokinetic (TK) and pharmacokinetic (PK) studies [4] | Organoleptic evaluations of food [1] |

| Studies to support IND, NDA, or marketing applications [2] [3] | Early-stage exploratory studies (e.g., preliminary ADME) [3] |

For analytical chemists, key applicable activities include characterizing the test article (drug substance), determining the stability of the test article and its mixtures, and analyzing specimens (e.g., blood, plasma, tissues) from test systems [4] [1].

Core Principles and Regulatory Framework

The 10 Principles of GLP

The OECD and FDA GLP regulations are built upon a set of foundational principles that create a managerial quality control system [4] [1].

Table: The 10 Principles of Good Laboratory Practice

| Principle Number | Principle Area | Core Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Test Facility Organization & Personnel | Defined structure, sufficient staff, clear responsibilities [1] |

| 2 | Quality Assurance Programme | Independent QAU monitoring study conduct [1] |

| 3 | Facilities | Adequate size, construction, and separation to prevent interference [1] |

| 4 | Apparatus, Material & Reagents | Appropriately designed, calibrated, and maintained [1] |

| 5 | Test Systems | Proper characterization, housing, and care [1] |

| 6 | Test & Reference Items | Proper characterization, handling, and storage [2] [1] |

| 7 | Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Written procedures for all study aspects [1] |

| 8 | Performance of the Study | Written protocol, raw data generated per GLP [1] |

| 9 | Reporting of Study Results | Comprehensive final report reconstructing study [1] |

| 10 | Storage & Retention of Records | Secure archiving of raw data, reports, and specimens [1] |

Key Requirements of 21 CFR Part 58

The U.S. FDA's 21 CFR Part 58 provides the detailed regulatory framework for GLP compliance, structured into multiple subparts [2] [7].

Table: Key Requirements of 21 CFR Part 58 Subparts

| Subpart | Focus Area | Specific Mandates |

|---|---|---|

| Subpart A | General Provisions | Defines scope, applicability, and definitions [2] |

| Subpart B | Organization & Personnel | Study Director responsibility; independent QAU [2] [7] |

| Subpart C | Facilities | Adequate lab, animal care, and article handling areas [2] [7] |

| Subpart D | Equipment | Appropriate design, maintenance, and calibration [2] [7] |

| Subpart E | Testing Facility Operations | Requires SOPs for all operations [2] |

| Subpart F | Test & Control Articles | Characterization, handling, and storage of test items [2] [7] |

| Subpart G | Protocol & Conduct | Written protocol; adherence to protocol during conduct [2] [7] |

| Subpart J | Records & Reports | Final report; raw data storage and retention [2] [7] |

GLP Organizational Structure and Data Flow

Critical Roles and Responsibilities

A clearly defined organizational structure with assigned responsibilities is a cornerstone of GLP.

The Study Director

The Study Director serves as the single point of control for the entire study and bears ultimate responsibility for its technical and GLP compliance [2] [7]. Key responsibilities include approving the study protocol, ensuring adherence to the protocol and SOPs, confirming accurate data collection, and preparing and approving the final study report, which includes a GLP compliance statement [2] [1].

The Quality Assurance Unit (QAU)

The QAU functions as the independent internal monitor, entirely separate from the personnel conducting the study [2] [3]. Its mandate is to "assure management that all facilities, equipment, personnel, methods, practices, records, and controls are in conformance with the regulations" [3]. The QAU achieves this through activities such as auditing final reports against raw data, conducting facility inspections, and reporting findings directly to management [2] [3].

Analytical Chemist Roles

Analytical chemists play two vital roles in GLP studies [4]:

Analytical Chemist (Test Article Characterization): Responsible for developing and using validated methods to determine the identity, strength, purity, composition, and stability of the test article (drug substance) and its formulations [4]. This ensures the test item is properly defined for the entire study duration.

Bioanalytical Chemist (Specimen Analysis): Analyzes biological samples (blood, plasma, urine, tissues) collected from test systems after administration of the test article [4]. These analyses, conducted according to validated methods (e.g., ICH M10), generate toxicokinetic and pharmacokinetic data critical for safety assessment [4].

Essential GLP Methodologies and Documentation

The Study Protocol

Every GLP study must be conducted according to a pre-approved, written protocol that acts as the study's master blueprint [2] [1]. The protocol must detail objectives, test system, study design, methods, materials, and schedules, ensuring all personnel understand the plan before initiation [1].

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

SOPs are documented procedures for routine operations, from instrument use and animal care to data handling [2] [8]. They are the foundation for consistency and quality control, minimizing variability and errors. Any deviation from an SOP must be authorized by the Study Director and documented [1].

Data Integrity and Good Documentation Practice (GDocP)

Data integrity under GLP is often described by the ALCOA+ principles [4]:

- Attributable (who created the data)

- Legible (readable)

- Contemporaneous (recorded at the time of the activity)

- Original (the first recording)

- Accurate (error-free)

- Plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [4]

All raw data, including chromatograms, notebook entries, and instrument printouts, must be preserved to allow for full reconstruction of the study [9].

The Final Report and Archiving

The Final Report, prepared and signed by the Study Director, provides a complete account of the study [2] [1]. It must describe any deviations from the protocol, present and interpret results, and include the QAU's audit statement. Upon completion, all raw data, documentation, and specimens are archived. Retention periods are mandated by regulation; for example, data supporting an FDA application must be kept for at least five years after submission [2] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for GLP-Compliant Analysis

| Item | GLP-Specific Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Test Article (Drug Substance) | The item under investigation; requires full characterization (identity, purity, stability) per §58.105 to define what is being tested [2] [4]. |

| Control Article (Reference Item) | Provides a baseline for comparison; must be appropriately characterized and handled to ensure validity of the study results [1]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | For instrument calibration and method validation; their traceability and purity are critical for data accuracy [9]. |

| Reagents & Solutions | Must be labeled with identity, titer, expiration date, and storage conditions per §58.83 to ensure reliability of analytical procedures [2]. |

| Biological Matrices | Blood, plasma, urine from test systems; stability of the analyte in these matrices must be established to assure result integrity [4]. |

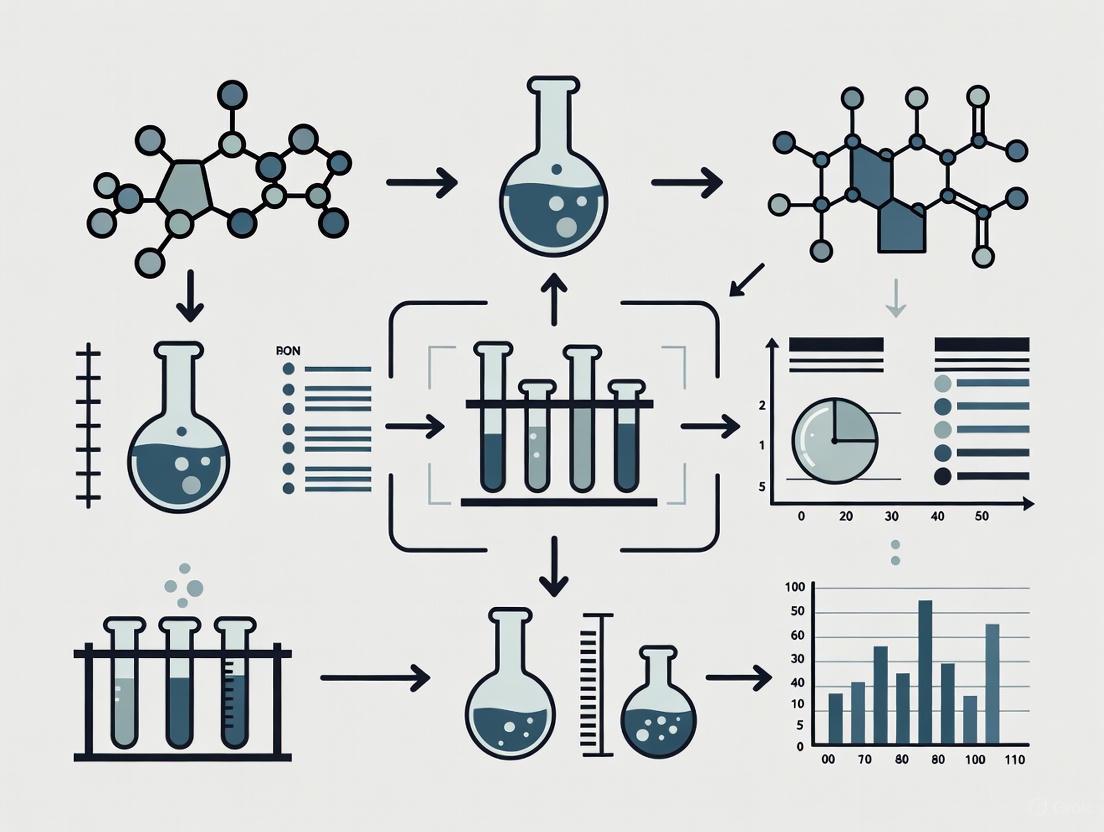

GLP-Compliant Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a GLP study, from initiation to archiving, highlighting the critical review points by the Study Director and QAU.

GLP Study Workflow Overview

Good Laboratory Practice provides an indispensable framework for generating reliable, defensible nonclinical safety data. For analytical chemists and drug development professionals, a thorough understanding of GLP's history, regulatory scope, and core principles—from the pivotal role of the Study Director and independent QAU to the rigorous demands of data integrity—is not merely a regulatory obligation. It is a fundamental component of scientific excellence, ensuring that the safety data underpinning new medicines can be trusted by regulators, the scientific community, and ultimately, the patients who will use them.

Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) is a quality system covering the organizational processes and conditions under which non-clinical health and environmental safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, reported, and archived [10]. Originally developed in response to cases of laboratory fraud and misconduct in the 1970s, GLP regulations were enacted to ensure the quality, reliability, and integrity of safety test data submitted to regulatory authorities [4] [2]. Unlike methods that assess scientific validity, GLP focuses on process quality control, ensuring that data from nonclinical studies are accurate, reproducible, and auditable. For analytical chemists and drug development professionals, understanding GLP is essential for generating regulatory-submission-ready data that protects public health by providing trustworthy evidence of product safety [2].

Scope and Application of GLP Regulations

Types of Studies and Products Covered

GLP principles apply to non-clinical safety testing of various regulated products. The core requirement is that these principles govern "non-clinical" testing of items examined under laboratory conditions or in the environment, excluding studies using human subjects [10].

Table 1: Product Categories and Study Types Under GLP Regulations

| Product Categories Covered | Examples of GLP Study Types |

|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical products [10] | Physical-chemical testing [10] |

| Pesticide products [10] | Toxicity studies (acute, chronic) [10] [4] |

| Cosmetic products [10] | Mutagenicity studies [10] |

| Veterinary drugs [10] | Environmental toxicity studies [10] |

| Food and feed additives [10] | Studies on behavior in water, soil, and air [10] |

| Industrial chemicals [10] | Bioaccumulation studies [10] |

| Medical devices (in some jurisdictions) [10] | Analytical and clinical chemistry testing [10] |

For drug development, GLP compliance is mandatory for pivotal nonclinical safety studies conducted before first-in-human clinical trials. These typically include pharmacology/drug disposition and toxicology (safety) evaluations, which investigate the pharmacological effects, mechanisms of action, and toxicological profiles of investigational products [4]. Specifically, toxicokinetic (TK) studies determine drug concentration at exaggerated levels to understand toxicity, while pharmacokinetic (PK) studies determine bioavailability and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics [4].

Key Regulatory Frameworks and Their Jurisdictions

Three major GLP frameworks form the cornerstone of global regulatory compliance, with significant alignment between them.

Table 2: Comparison of Major GLP Regulatory Frameworks

| Framework | Jurisdiction & Authority | Key Document References | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 CFR Part 58 | United States (FDA) [11] | 21 CFR Part 58 [11] | Legally binding US regulation; applies to products under FDA purview [4] |

| OECD Principles of GLP | OECD Member Countries (38+) [10] [4] | OECD Series on Principles of GLP [10] | Facilitates international data acceptance via Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system [2] |

| EPA GLP Regulations | United States (Environmental Protection Agency) [4] | 40 CFR 160 (FIFRA), 40 CFR 792 (TSCA) [4] | Regulates chemicals, pesticides, and other environmental agents [4] |

The OECD Principles of GLP serve as a global benchmark, with member countries establishing national GLP Compliance Monitoring Programmes (CMPs) responsible for monitoring GLP compliance through test facility inspections and study audits [10]. A facility found compliant is recognized as a GLP compliant test facility, and its data is accepted across OECD member countries [10]. The FDA similarly conducts careful inspections of facilities performing nonclinical laboratory studies to determine compliance with 21 CFR Part 58 [6].

Core Principles and Regulatory Requirements

Organizational Structure and Personnel Responsibilities

Effective implementation of GLP requires a clear organizational structure with defined roles and responsibilities. The following diagram illustrates the key personnel and their relationships in a GLP-compliant facility.

Key responsibilities for each role include:

- Test Facility Management: Provides adequate resources, appoints the Study Director, and establishes a Quality Assurance Unit (QAU) independent of study conduct [10] [2].

- Study Director: Serves as the single point of control with ultimate responsibility for the overall conduct of the study and final report [10]. This includes ensuring compliance with the protocol and GLP principles.

- Quality Assurance Unit (QAU): Monitors GLP compliance through audits of processes, raw data, and reports, maintaining independent oversight without being directly involved in study conduct [4] [2].

- Study Personnel: Must possess the education, training, and experience required to perform their assigned functions and comply with all GLP regulations relevant to their activities [2].

Facilities, Equipment, and Testing Operations

GLP regulations specify requirements for the physical environment and equipment to ensure study integrity:

- Facility Design: Laboratories must have adequate size, construction, and separation to prevent cross-contamination and mix-ups [11] [2]. This includes designated areas for test system handling, test article storage, and laboratory operations.

- Equipment Standards: All equipment used in generation, measurement, or assessment of data must be of appropriate design and adequate capacity, properly maintained and calibrated according to written Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) [11] [2].

- Animal Care: Facilities housing animal test systems must have proper environmental controls (lighting, temperature, humidity) and sanitation processes to ensure animal well-being and prevent disease that could confound study results [11].

- Reagents and Solutions: All laboratory reagents and solutions must be properly labeled with identity, concentration, storage requirements, and expiration date to ensure their compositional integrity throughout the study [11].

Test and Control Articles Characterization

GLP mandates rigorous characterization and handling of test and control articles:

- Characterization Requirements: Each test and control article must be appropriately characterized to determine its identity, strength, purity, composition, and stability [11] [2]. Analytical chemists develop methods to establish these characteristics.

- Stability Determination: The stability of the test and control articles must be determined to assign appropriate storage conditions and ensure the concentration does not change significantly during the study [4].

- Handling Procedures: Procedures must ensure proper receipt, identification, labeling, storage, sampling, and distribution of test and control articles to prevent mix-ups, contamination, or degradation [11].

- Mixtures with Carriers: For articles mixed with carriers (e.g., vehicle solutions, feed), studies must determine the homogeneity, concentration, and stability of the mixture to ensure consistent dosing throughout the administration period [11].

Protocols and Study Conduct

Each nonclinical laboratory study requires a written, approved protocol that clearly defines the study's objectives and all methods for its conduct [11]. The protocol must include:

- Identification Information: Descriptive title, statement of purpose, test and control article identification, and sponsor/facility information.

- Experimental Design: Detailed study design including methods for controlling bias, number of test system units, and application of test articles including dosage levels and frequency.

- Data Collection: Type and frequency of tests, measurements, and observations to be made, along with statistical methods for data analysis.

- Study Amendments: Any changes to the protocol must be documented as formal amendments signed by the Study Director, maintaining the study's audit trail [11].

Records, Reports, and Archiving

Documentation and data integrity form the foundation of GLP compliance:

- Final Study Report: For each study, a comprehensive final report must include all protocol information, statistical methods, test article characterization, raw data storage information, and study results and conclusions signed by the Study Director [11].

- Data Integrity (ALCOA+): Good Documentation Practice (GDocP) follows the ALCOA+ principles: Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [4]. All data must be recorded directly, promptly, and legibly in ink.

- Record Retention: All raw data, documentation, protocols, final reports, and specimens (except those subject to degradation) must be retained in archives for specified periods, typically several years after study completion [11] [2].

- Electronic Records: Computerized systems used in GLP studies must be validated, maintained, and controlled to ensure data integrity and compliance with electronic records requirements [10].

GLP Implementation for Analytical Chemists

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Analytical chemists play crucial roles in GLP-compliant studies through two primary functions: test article characterization and bioanalytical testing of samples from test systems.

Table 3: Analytical Chemistry Functions in GLP Studies

| Analytical Function | Key Responsibilities | Common Techniques & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Test Article Characterization | Determine identity, strength, purity, composition, stability of test substances and formulations [4] | HPLC-UV, GC, MS, dissolution testing, physicochemical characterization [4] |

| Bioanalytical Testing | Analyze drug/metabolite concentrations in biological matrices from test systems; support TK/PK studies [4] | LC-MS/MS, ELISA, immunogenicity assays [4] |

| Dose Formulation Analysis | Confirm homogeneity and stability of test article in carrier vehicles; verify concentration during administration [4] | HPLC, UV-Vis spectroscopy [4] |

Test Article Characterization Protocol

Objective: To determine the identity, strength, purity, composition, and stability of test and control articles under GLP compliance [4] [2].

Methodology:

- Reference Standard Qualification: Establish qualified reference standards for comparison using orthogonal analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, NMR, MS) to confirm identity and purity.

- Test Article Analysis: Perform phase-appropriate method validation for GLP studies, recognizing limited degradation data in early development [4].

- Stability Monitoring: Establish stability-indicating methods to assign appropriate storage conditions and ensure concentration remains within established ranges throughout the study [4].

- Documentation: Record all procedures, results, and instrument calibration data contemporaneously following ALCOA+ principles in electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs) [4].

Bioanalytical Method Validation Protocol

Objective: To validate bioanalytical methods for quantitative measurement of drugs and their metabolites in biological matrices per ICH M10 guidelines [4].

Methodology:

- Precision and Accuracy: Determine intra-day and inter-day variability using quality control samples at multiple concentrations across multiple runs.

- Selectivity and Specificity: Verify ability to measure analyte unequivocally in presence of other components, evaluating potential interference from matrix components, metabolites, or co-administered medications [4].

- Stability Assessments: Evaluate analyte stability under various conditions: bench-top, frozen, freeze-thaw cycles, and processed sample stability [4].

- Matrix Effect Evaluation: For LC-MS methods, assess ion suppression/enhancement using samples from multiple sources, especially for rare disease populations with potentially different matrix compositions [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for GLP-Compliant Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application in GLP Studies | Quality & Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Quantification and identity confirmation of test articles; method calibration [4] | Certificate of Analysis (CoA) documenting source, purity, and characterization data [4] |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation for HPLC and LC-MS analyses to minimize background interference | Must be properly labeled with receipt date, expiration date, and storage conditions [11] |

| Biological Matrix Samples | Method development and validation using appropriate matrices (plasma, serum, tissue) [4] | Documented source, collection method, and storage conditions; screening for inherent abnormalities [4] |

| Quality Control Materials | Intra-study monitoring of method performance accuracy, precision [4] | Prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations from independent weighings; stability documentation [4] |

Global Harmonization and Compliance Monitoring

International Convergence and Mutual Acceptance

The OECD Principles of GLP represent the cornerstone of international harmonization, enabling the Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system where studies conducted in accordance with OECD GLP Principles in one member country must be accepted by other member countries [10] [2]. This framework eliminates redundant testing, reduces administrative burdens, and conserves resources while maintaining high-quality safety standards. The OECD Working Party on GLP maintains and updates guidance through Consensus and Advisory Documents that address specific technical aspects of GLP implementation, such as application to field studies, multi-site studies, in vitro studies, and computerised systems [10].

Compliance Monitoring and Inspection Procedures

National GLP Compliance Monitoring Programmes (CMPs) verify GLP compliance through regular inspections of test facilities and audits of GLP studies [10]. The inspection process typically involves:

- Facility Inspections: Comprehensive evaluation of organizational structure, facilities, equipment, procedures, and personnel qualifications to assess overall GLP compliance [10] [6].

- Study Audits: Examination of ongoing or completed studies to verify adherence to protocols, SOPs, and proper documentation practices [10].

- Corrective Actions: Facilities must address any deficiencies identified during inspections to maintain their GLP compliant status [10].

- Data Integrity Verification: Specific focus on computerized system validation, electronic records management, and data traceability in accordance with OECD GLP Advisory Document No. 17 on Computerised Systems [10].

The framework established by 21 CFR Part 58, OECD Principles of GLP, and related regulations provides a comprehensive quality system for ensuring the reliability and integrity of nonclinical safety data. For analytical chemists and drug development professionals, understanding these regulations is not merely a compliance exercise but a fundamental aspect of generating scientifically sound, regulatory-ready data. The continued global harmonization of GLP standards through organizations like OECD facilitates international acceptance of safety data, ultimately contributing to more efficient development of safe products worldwide. As regulatory science evolves, GLP principles continue to adapt to new technologies and testing paradigms while maintaining their core mission: ensuring that safety decisions are based on trustworthy, verifiable, and high-quality laboratory data.

Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) constitutes a pivotal quality system governing the organizational processes and conditions under which nonclinical laboratory studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, reported, and archived [4]. Enacted in 1978 and codified in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 58 (21 CFR Part 58), GLP regulations were established primarily to ensure the quality, reliability, and integrity of safety test data submitted to regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) [4] [2]. These regulations apply specifically to nonclinical safety studies that support research or marketing permits for products including human and animal drugs, biologics, medical devices, and food additives [4] [2]. For analytical chemists, understanding GLP is fundamental, as their work in characterizing test articles and analyzing biological specimens forms the bedrock of credible nonclinical safety assessment.

The principal objective of GLP is to assure regulatory authorities that the safety data presented are a truthful and accurate representation of the study findings, thereby enabling valid risk assessments [2]. This is achieved through a framework emphasizing process standardization, meticulous documentation, and independent quality oversight. It is crucial to recognize that GLP is a quality system concerned with the process of data collection and documentation; it does not judge the scientific validity of a study's hypothesis but ensures that whatever was done can be accurately reconstructed and verified [2]. This distinction is paramount for analytical chemists, for whom data integrity is non-negotiable.

Within the drug development lifecycle, GLP governs the pivotal nonclinical safety studies conducted before first-in-human clinical trials [4]. These typically include pharmacology/drug disposition studies, which investigate a drug's pharmacological effects and its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), and toxicology studies, which monitor toxic effects in vitro and in vivo [4]. Pharmacokinetic (PK) and toxicokinetic (TK) studies are central to this phase, determining the concentration of a drug candidate in animals over time to establish safety margins and human equivalent doses [4]. The principles of GLP, while mandated for these nonclinical studies, are often adopted and combined with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for clinical bioanalytical testing, a hybrid standard known as Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP) [4].

Regulatory Framework and Key Principles

The GLP regulatory landscape is multifaceted, involving both national and international authorities. In the United States, the FDA's GLP regulations are detailed in 21 CFR Part 58, while the EPA promulgates its own GLP standards under 40 CFR 160 (FIFRA) and 40 CFR 792 (TSCA) for pesticides and industrial chemicals, respectively [4] [12]. Internationally, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has established harmonized GLP principles that have been adopted by its 38 member countries, facilitating the mutual acceptance of data (MAD) across national borders [4] [2]. The European Union operates under Directives 2004/9/EC and 2004/10/EC, which align with OECD principles and require member states to designate GLP inspection authorities [7].

A foundational element of this framework is the definition of key roles and responsibilities within a testing facility, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Key Personnel Roles and Responsibilities under GLP

| Role | Primary Responsibility | Key Duties |

|---|---|---|

| Study Director | Single point of control and ultimate responsibility for the overall conduct of the study and its final report [1] [7]. | Approves the study protocol and any amendments; ensures GLP compliance; interprets, analyzes, and documents results; approves the final report [1]. |

| Quality Assurance Unit (QAU) | An independent entity that monitors GLP compliance [2] [7]. | Conducts in-study inspections; audits final reports for accuracy and compliance; reports findings directly to management and the Study Director [1] [2]. |

| Testing Facility Management | Provides overall organization and resources [1]. | Appoints the Study Director and QAU; ensures adequate personnel, facilities, and equipment are available [1]. |

| Analytical Chemist | Executes laboratory analyses related to test article characterization and bioanalysis [4]. | Develops and validates analytical methods; performs analysis; documents all activities in compliance with GDocP principles [4]. |

The core principles of GLP can be distilled into ten key areas, as defined by the OECD and other regulatory bodies. These principles provide the structural backbone for any GLP-compliant study [4] [1]:

- Test Facility Organization and Personnel: A clear organizational structure with defined responsibilities and appropriately qualified personnel.

- Quality Assurance Programme: An independent QAU responsible for monitoring GLP compliance.

- Facilities: Adequate, well-separated facilities to prevent cross-contamination and interference.

- Apparatus, Material, and Reagents: Properly designed, calibrated, and maintained equipment.

- Test Systems: Proper characterization, housing, and care of test systems (e.g., animals, cells).

- Test and Reference Items: Thorough characterization, handling, and storage to ensure stability and prevent mix-ups.

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Documented procedures for all routine operations.

- Performance of the Study: A written, approved study protocol and adherence to it during conduct.

- Reporting of Study Results: A final report that accurately and completely describes the study and its results.

- Storage and Retention of Records and Materials: Secure archiving of all raw data, documentation, specimens, and reports for defined retention periods [1].

For the analytical chemist, Good Documentation Practice (GDocP) is a pervasive and critical requirement. Often described by the acronym ALCOA+, data and records must be Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [4]. This means all laboratory activities, from weighing materials to integrating chromatographic peaks, must be recorded in real-time, using electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs) and other systems that ensure full traceability and data integrity.

The Analytical Chemist in Test Article Characterization

A primary responsibility of the analytical chemist in a GLP environment is the comprehensive characterization of the test and control articles. As mandated by 21 CFR 58.105, this involves determining the identity, strength, purity, composition, and stability of the articles to appropriately define them for the study [4] [2]. The data generated is essential for confirming that the test system is exposed to the correct, consistent material throughout the study, which is fundamental to interpreting toxicological outcomes.

Core Responsibilities and Methodologies

The analytical chemist's role in test article characterization encompasses several critical activities:

- Method Development and Validation: Developing phase-appropriate analytical methods, typically using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV) for small molecules, to assess key characteristics of the test article [4]. These methods must be validated to demonstrate they are suitable for their intended purpose, even at this early stage of development.

- Stability Assessment: Establishing the stability of the test article and its formulations (dosing solutions) under storage and use conditions is mandatory. This ensures the concentration and integrity of the article do not change significantly from the start to the end of the study, thereby validating the doses administered to the test system [4].

- Characterization of Formulations: For toxicology studies, the test article is often administered in a simple carrier or formulation. The chemist must analyze these mixtures to confirm homogeneity and concentration, ensuring uniform exposure across all test subjects [4].

The workflow for test article characterization is a meticulous, multi-stage process that ensures data integrity from sample receipt to final reporting, as illustrated below.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The work of characterization relies on a suite of specific reagents and materials, each serving a critical function in ensuring accurate and reliable results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Test Article Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function | GLP Compliance Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for determining identity, purity, and strength of the test article via comparison. | Must be fully characterized, with certificates of analysis (CoA) and stored according to specified conditions [4]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Used for mobile phases, sample dilution, and dissolution to ensure minimal interference and high signal-to-noise ratios. | Must be tracked for lot number and expiry; prepared and labeled in accordance with SOPs (§58.83) [2]. |

| Characterized Test & Control Articles | The substances being studied (test article) and compared against (control article). | Requirement for complete characterization (§58.105) including stability; chain of custody must be maintained [4] [1]. |

The Bioanalytical Chemist in Nonclinical Study Support

While the analytical chemist focuses on the test article itself, the bioanalytical chemist is responsible for measuring the concentration of the drug and its metabolites in biological matrices collected from the test system. This data is the cornerstone of PK and TK studies, which aim to demonstrate the drug's bioavailability, its fate in a living organism, and its relationship to observed toxicity [4]. This role is governed by 21 CFR 58.120 and 58.130, and the methods employed must be validated in accordance with international guidelines like the ICH M10 guideline on bioanalytical method validation [4].

Analytical Techniques and Method Validation

Bioanalytical chemists employ a range of sophisticated techniques tailored to the type of drug molecule being analyzed.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): This is the workhorse for the quantitative analysis of small molecule drugs and some peptides in biological fluids [4] [13]. It offers high selectivity, specificity, and a wide linear dynamic range (typically 3-4 orders of magnitude) [13].

- Ligand Binding Assays (LBA): Techniques like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and electrochemiluminescence (e.g., on MSD platforms) are typically used for large molecule drugs, such as therapeutic proteins and antibodies [4] [13]. LBAs can offer very high sensitivity (down to pg/mL) but may have a narrower quantitative range and be more susceptible to matrix effects [13].

For a method to be deemed GLP-compliant, it must undergo a rigorous validation process. Core validation parameters include precision, accuracy, selectivity, and specificity [4]. Additional experiments characterize the assay's performance, including the stability of the analyte in the biological matrix (e.g., at room temperature, frozen, and through freeze-thaw cycles) and the potential for interference from co-administered medications or the biological matrix itself [4].

A particularly complex area for the bioanalytical chemist is the analysis of modern biologic drugs, such as GLP-1 analogs (e.g., semaglutide, liraglutide). These molecules present unique challenges, including complex sample preparation to isolate the analyte from the biological matrix and their tendency to adsorb to surfaces within the LC-MS/MS system due to structural modifications like added lipid chains [13].

Specialized Area: Immunogenicity Testing

For biologic drugs, bioanalytical support extends beyond PK analysis to include immunogenicity testing [4] [13]. Immunogenicity is the tendency of a biologic drug to elicit an unwanted immune response, which can impact the drug's efficacy and safety [4]. Testing is a multi-tiered process typically involving:

- Screening Assays: To identify samples that contain anti-drug antibodies (ADAs).

- Confirmatory Assays: To verify that the immune response is specific to the drug.

- Neutralizing Antibody (NAb) Assays: To determine if the ADAs can block the biological activity of the drug.

These assays often use sophisticated LBA platforms like electrochemiluminescence or cell-based assays for NAb detection [4] [13]. The complexity of these analyses demands careful method development, particularly for smaller biologic drugs where labeling efficiency for assays can be low [13].

The following diagram outlines the integrated workflow for supporting a nonclinical study, from sample collection to data reporting.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of GLP-compliant analysis is not static; it is being reshaped by technological advancements that promise to enhance efficiency, data quality, and analytical capabilities.

- Laboratory Automation: Automated systems, particularly for sample preparation (e.g., pipetting robots), are becoming integral to handling large sample volumes from nonclinical studies [14]. These systems improve reproducibility, reduce human error, and free up skilled chemists for more complex tasks [14]. The trend is moving towards end-to-end automated workflows that integrate sample registration, preparation, analysis, and data evaluation.

- Digitalization and Data Integrity: The increasing digitalization of the laboratory, through Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) and ELNs, ensures consistent data capture and facilitates compliance with GDocP and 21 CFR Part 11 (electronic records) [14]. The Internet of Things (IoT) allows for real-time monitoring of instrument conditions and sample storage environments, further safeguarding data integrity [14].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI and machine learning are beginning to be applied to optimize laboratory processes, adjust method parameters in real-time, and assist in data review, potentially leading to faster and more precise analyses [14].

- Advanced Analytical Platforms: The ongoing evolution of LC-MS/MS and LBA platforms continues to push the boundaries of sensitivity and throughput. For complex molecules like GLP-1 analogs, the use of multiple analytical platforms (LC-MS/MS and LBA) is often necessary to overcome specific challenges like adsorption and to provide complementary data sets for regulatory submissions [13].

The role of the analytical and bioanalytical chemist is indispensable within the GLP framework. From the initial characterization of the test article to the complex quantification of drug levels in biological matrices, their work generates the foundational data upon which critical safety decisions are made. Adherence to the rigorous principles of GLP—through qualified personnel, validated methods, calibrated equipment, meticulous documentation, and independent quality assurance—is what transforms routine laboratory analysis into reliable, auditable, and defensible evidence for regulatory review. As drug modalities become more complex and technologies continue to advance, the chemist's expertise in adapting and applying these principles will remain a cornerstone of ethical and successful drug development.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) constitutes a foundational quality system that ensures the integrity and reliability of nonclinical safety data. GLP is not merely a set of technical procedures but a comprehensive managerial quality control system covering the organizational processes and conditions under which non-clinical health and environmental safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, reported, and archived [10]. For analytical chemists, particularly those supporting drug development, adherence to GLP principles is mandatory for pivotal nonclinical studies submitted to regulatory authorities like the FDA and EPA to support applications for research or marketing permits [15] [16]. This whitepaper delves into the four core pillars of GLP—Organization, Personnel, the Study Director, and the Quality Assurance Unit (QAU)—framing them within the specific context of the analytical laboratory's critical role in the drug development pipeline.

The Five Fundamental Points of GLP

The GLP framework rests on five interdependent fundamental points that together guarantee data quality and regulatory acceptance. These principles are:

- Organization and Personnel: The foundation of GLP, requiring a clear organizational structure with qualified, trained staff who understand their responsibilities [17] [18].

- Facilities and Equipment: Laboratories must maintain controlled, fit-for-purpose environments and properly calibrated, validated, and maintained instruments [17].

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Every critical task must be governed by written, approved procedures to ensure consistency and reproducibility of all operations [17] [16].

- Study Documentation and Reporting (Raw Data & Final Report): All raw data must be recorded promptly, accurately, and traceably, with final reports accurately reflecting the raw data [17].

- Quality Assurance (QA) Unit: An independent monitoring system must be in place to verify that all aspects of the study comply with GLP principles [17] [16].

These components form a cohesive system designed to produce studies that are scientifically sound, auditable, and defensible, providing regulatory agencies with confidence in the submitted data.

Detailed Analysis of Core GLP Pillars

Organization and Personnel

The GLP principles mandate a well-defined organizational structure with clear lines of authority and responsibility. Sufficient personnel with appropriate qualifications are essential for the timely and proper conduct of a study [19] [18].

Key Responsibilities: Test Facility Management holds the ultimate responsibility for the entire organization's compliance with GLP. Their extensive duties, as outlined by OECD, FDA, and EPA, are summarized in the table below [19] [18].

Table 1: Key Responsibilities of Test Facility Management

| Responsibility Area | Specific Requirement |

|---|---|

| Resources & Personnel | Ensure sufficient qualified personnel, facilities, equipment, and materials are available [18]. Maintain records of qualifications, training, and job descriptions [19]. |

| Study Oversight | Designate and replace (if necessary) a Study Director before a study is initiated [18]. For multi-site studies, designate a Principal Investigator as needed [19]. |

| Quality System | Ensure the establishment of a Quality Assurance Programme and approve all original and revised SOPs [19] [18]. |

| Facility Operations | Ensure test and reference items are appropriately characterized and that facility supplies meet requirements [18]. Maintain a master schedule of all studies [19]. |

Personnel Requirements: All individuals engaged in a study must possess the education, training, and experience necessary to perform their assigned functions [18]. Key requirements for study personnel include:

- Access and Compliance: Personnel must have access to the study plan and relevant SOPs and are responsible for complying with their instructions [18].

- Data Integrity: All personnel are responsible for recording raw data promptly, accurately, and in compliance with GLP principles, bearing direct responsibility for the quality of the data they generate [19] [18].

- Health Precautions: Personnel must take necessary personal sanitation and health precautions to avoid contaminating test systems and articles. They must report any medical condition that could adversely affect the study's integrity [18].

The Study Director: The Single Point of Control

The Study Director is the central pillar of any GLP study, serving as the "single point of study control" [20]. According to 21 CFR Part 58, this individual must be "a scientist or other professional of appropriate education, training, and experience" who assumes overall responsibility for the technical conduct of the study, as well as for the interpretation, analysis, documentation, and reporting of results [20].

Table 2: Core Responsibilities of the Study Director

| Responsibility | Description |

|---|---|

| Protocol Approval & Adherence | Approve the study protocol and any amendments, and ensure they are followed [20]. |

| Data Integrity | Ensure all experimental data, including observations of unanticipated responses, are accurately recorded and verified [20]. |

| Issue Management | Document unforeseen circumstances affecting the study, and implement and document corrective action [20]. |

| GLP Compliance | Assure that all applicable GLP regulations are followed throughout the study [20]. |

| Archiving | Ensure all raw data, documentation, protocols, specimens, and final reports are transferred to the archives upon study completion [20]. |

The Study Director acts as the primary communicator, liaising between management, the QAU, and study personnel. In multi-site studies, the Study Director may delegate specific supervisory duties for a defined phase of the study to a Principal Investigator, who then acts on the Study Director's behalf while ensuring their phase is conducted per the protocol, SOPs, and GLP [19].

The Quality Assurance Unit: The Independent Guarantor of Quality

The Quality Assurance Unit (QAU) is an independent entity within the test facility that provides assurance to management that the facilities, equipment, personnel, methods, practices, records, and controls are in compliance with GLP regulations [16]. The QAU is critical for maintaining objective oversight as its personnel must not be involved in the conduct of the study they are assuring [19].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between the core personnel in a GLP-compliant study, highlighting the QAU's independent oversight role.

Diagram 1: GLP Personnel Relationships & Workflow (Width: 760px)

QAU Activities and Audits: The QAU's mandate is fulfilled through a systematic process of audits and inspections, which include [21]:

- Facility Audits: Assessing if the facility is fit for purpose and has the necessary supporting documentation.

- Process and Study-Based Inspections: Observing personnel in the laboratory to ensure they follow procedures and work in compliance with GLP.

- Study Plan and Final Report Audits: Reviewing the protocol and the final report to ensure the report accurately reflects the raw data and contains all required elements.

- Audit of Computerized Systems: Reviewing validation documentation and ongoing maintenance of systems used to generate or manipulate study data.

After each inspection, the QAU must promptly report findings in writing to management and the Study Director. Ultimately, the QAU prepares and signs a statement included in the final report, specifying the inspection dates and types and confirming that the report accurately reflects the raw data [19] [16].

GLP in Practice: An Analytical Chemist's Perspective

For analytical and bioanalytical chemists, GLP implementation translates into specific, rigorous practices tailored to their functions.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

1. Test Article Characterization and Stability Monitoring: The analytical chemist is responsible for developing and validating methods to characterize the test article (drug substance or formulation) to determine its identity, strength, purity, composition, and other defining characteristics [15].

- Detailed Methodology:

- Method Development & Validation: Develop phase-appropriate analytical methods, often using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Ultraviolet detection (HPLC-UV) for small molecules. The equipment must have proper qualification documentation [15].

- Stability Assessment: Conduct stability studies on the test and control articles (e.g., drug substance and dosing solution) under specified storage conditions. This involves testing samples over time to establish that the concentration and properties of the test article do not change significantly from manufacture through the study's end [15].

- Homogeneity Testing: For formulations, ensure the test article is homogeneously mixed or suspended.

2. Bioanalytical Method Validation and Sample Analysis: The bioanalytical chemist is responsible for analyzing biological specimens (blood, plasma, urine, tissues) collected from test systems after administration of the test article, supporting pharmacokinetic (PK) and toxicokinetic (TK) studies [15].

- Detailed Methodology:

- Method Validation per ICH M10: Validate bioanalytical methods in accordance with international guidelines. Core validation parameters include [15]:

- Precision and Accuracy: Evaluate across multiple validation runs.

- Selectivity and Specificity: Demonstrate the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components like metabolites or endogenous substances. Selectivity must be evaluated in relevant populations.

- Stability: Determine analyte stability in the biological matrix under various conditions (room temperature, frozen, freeze-thaw cycles).

- Sample Analysis: Use techniques like LC-MS/MS for small molecules or ELISA for large molecules to measure drug and metabolite concentrations. The process must adhere to a strict chain of custody for all specimens [15].

- Method Validation per ICH M10: Validate bioanalytical methods in accordance with international guidelines. Core validation parameters include [15]:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for an analytical chemist conducting GLP-compliant studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GLP-Compliant Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function in GLP Studies |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | To calibrate instruments and verify method accuracy for test article characterization. Essential for generating definitive data on identity, strength, and purity [15]. |

| Chromatography Columns & Supplies | For HPLC and LC-MS systems to separate and resolve the analyte of interest from complex matrices (e.g., formulated drug product or biological samples) [15]. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Solvents & Reagents | To ensure minimal interference and background noise during highly sensitive bioanalytical assays (e.g., PK/TK analysis), preventing inaccurate concentration measurements [15]. |

| Characterized Biological Matrices | (e.g., control plasma, serum). Used as the blank matrix for preparing calibration standards and quality control samples during bioanalytical method validation and sample analysis [15]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Used in LC-MS/MS bioanalysis to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency, significantly improving data accuracy and precision [15]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Prepared at low, mid, and high concentrations from a separate weighing of the reference standard. Their analysis throughout a sample run validates the assay's performance and the integrity of the reported unknown sample concentrations [15]. |

Data Integrity and Documentation: The ALCOA+ Principle

Adherence to Good Documentation Practice (GDocP) is non-negotiable. For the analytical chemist, this means all data must be recorded in accordance with the ALCOA+ principle, which dictates that data must be [15]:

- Attributable (who recorded it and when),

- Legible,

- Contemporaneous (recorded at the time of the activity),

- Original (or a certified copy),

- Accurate. Furthermore, data should be Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [15]. This is typically achieved using controlled laboratory notebooks, either electronic or paper-based, and a robust Chromatography Data System (CDS). All raw data, including electronic data and notebooks, must be archived at the study's close [20] [15].

The GLP principles are enforced by various regulatory bodies worldwide, each with its own specific regulations. The following table provides a comparative overview of key personnel requirements across major authorities.

Table 4: Regulatory Comparison of Key GLP Personnel Requirements

| Topic | FDA (21 CFR 58) | EPA (40 CFR 160/792) | OECD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel Training & Experience | Education, training, experience to perform assigned functions [18]. | Education, training, experience to perform assigned functions [18]. | Personnel must be knowledgeable in applicable GLP principles [18]. |

| Summary of Training & Job Descriptions | Facility must maintain current summary for each individual [18]. | Facility must maintain current summary for each individual [18]. | Management must maintain a record of qualifications and job description [18]. |

| Designate a Study Director | Management must designate a study director before study initiation [18]. | Management must designate a study director before study initiation [18]. | Management must designate a Study Director with appropriate qualifications [18]. |

| Establish a QAU | Management must assure there is a QAU [18]. | Management must assure there is a QAU [18]. | Management must ensure a Quality Assurance Programme with designated personnel [18]. |

For analytical chemists and drug development professionals, the core GLP principles of Organization, Personnel, Study Director, and the QAU are not abstract regulations but practical necessities. They form an integrated framework that ensures the generation of high-quality, reliable, and defensible nonclinical safety data. The Study Director's role as the single point of control is paramount, providing unified scientific and managerial leadership. Simultaneously, the QAU's independent oversight and the foundational support of a well-structured organization with qualified personnel create a system of checks and balances. Mastering these principles is essential for successfully navigating the regulatory landscape and ultimately contributing to the development of safe and effective pharmaceuticals and other regulated products.

This whitepaper examines the ALCOA+ framework as a cornerstone of Data Integrity and Good Documentation Practice (GDocP) within Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) environments. Aimed at analytical chemists and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive technical guide for implementing these principles in analytical research, method validation, and data management. The guidelines detailed herein ensure regulatory compliance, data reliability, and scientific integrity throughout the research lifecycle.

In analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical research, data integrity forms the foundation of credible scientific results and regulatory submissions. Good Documentation Practice (GDocP) comprises the systematic approaches for creating, maintaining, and archiving records to ensure this integrity. For analytical chemists working under GLP standards, the primary objective is to generate data that is complete, consistent, and accurate from the point of acquisition through to final reporting and long-term retention [22] [23].

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other international regulatory bodies mandate that all GxP data adhere to a robust framework to ensure its trustworthiness [24] [25]. The ALCOA+ principles provide this structured framework, offering a clear set of criteria that are equally applicable to paper, electronic, and hybrid records [26]. Adherence to these principles is not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental component of a successful quality culture, ultimately protecting patient safety and product efficacy [22] [27].

The ALCOA+ Framework: Core Principles and Definitions

The ALCOA framework was first articulated by the FDA in the 1990s and has since evolved into ALCOA+ to address the complexities of modern data systems [28] [24]. The following table summarizes the core and expanded principles.

Table 1: The Core and Expanded Principles of the ALCOA+ Framework

| Principle | Acronym | Definition & Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Attributable | A | Data must be linked to the person or system that created it. Requires recording who performed an action, what system was used, and when it occurred [22] [26] [29]. |

| Legible | L | Data must be readable and permanent, both immediately and for the entire retention period. This applies to handwriting and electronic formats, ensuring understanding over time [22] [26] [27]. |

| Contemporaneous | C | Data must be recorded at the time the activity is performed. Real-time documentation is critical to prevent errors of memory or retrospective recording [22] [29] [30]. |

| Original | O | The first or source record of data must be preserved. This includes the first capture in a notebook, electronic record, or a certified copy thereof [22] [26] [28]. |

| Accurate | A | Data must be error-free, truthful, and reflect actual observations. Any amendments must be documented without obscuring the original entry [22] [26] [29]. |

| Complete | + | All data must be present, including original entries, repeat analyses, and metadata. No data should be omitted or deleted from the dataset [22] [26] [25]. |

| Consistent | + | The data sequence should be chronologically logical. Timestamps must be consistent and follow the expected sequence of workflows [22] [26] [27]. |

| Enduring | + | Data must be recorded on durable, authorized media designed for long-term retention, surviving the required retention period (often decades) [22] [26] [25]. |

| Available | + | Data must be readily accessible for review, audit, or inspection over its entire lifetime, with proper indexing and searchability [22] [26] [27]. |

The "+" in ALCOA+: Traceability

Many modern interpretations, including ALCOA++, add a tenth principle: Traceable [28]. This emphasizes the need for a clear, documented journey for each datum, from its origin through all transformations, analyses, and reporting. A robust audit trail that captures the "who, what, when, and why" of all data changes is essential for meeting this principle and reconstructing the research process during an audit [28].

ALCOA+ in the Analytical Laboratory Workflow

For the analytical chemist, ALCOA+ principles are applied throughout the entire data lifecycle. The following diagram illustrates how these principles integrate into a typical analytical workflow.

Diagram 1: Application of ALCOA+ principles in an analytical workflow.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The following detailed methodologies for common analytical procedures demonstrate the practical application of GDocP.

Protocol for HPLC Method Validation with ALCOA+

- Objective: To validate a new High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method for assay of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in accordance with ALCOA+.

- Materials: HPLC system with validated software, reference standard, samples, and appropriate solvents.

- Procedure:

- System Suitability: Prior to analysis, perform system suitability tests (e.g., injection repeatability, theoretical plate count). The original chromatograms and accurate results must be saved directly to the network drive, not a local computer.

- Sample Analysis: Inject calibration standards and samples in sequence defined by the protocol. The contemporaneous timestamp for each injection is automatically recorded by the HPLC software's audit trail.

- Data Integration: Process chromatographic data using predefined, validated methods. Any manual integration must be attributable (logged with user ID) and accurate (justified with a reason documented in the audit trail, without obscuring the original integration).

- Calculation & Reporting: Generate the final report. The process must be complete, including all raw data, processed data, audit trail entries, and metadata. The final report must be an original record or a certified copy.

Protocol for Sample Weighting and Preparation

- Objective: To accurately weigh a sample for standard solution preparation.

- Materials: Certified analytical balance (calibrated), weighing vessels, and sample.

- Procedure:

- Tare: Place the weighing vessel on the balance and tare. Ensure the balance is connected to a printer or data capture system.

- Weighing: Add the sample to the vessel. Record the weight directly onto the controlled worksheet or via the balance's direct data output. The record must be legible and original.

- Documentation: The analyst must sign and date the entry immediately (contemporaneous). If an error is made, a single line is drawn through the mistake, the correction is written alongside, and the correction is initialed and dated (accurate, with original data preserved).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details critical reagents and materials for GDocP-compliant analytical work, along with their functions and links to ALCOA+.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for GDocP

| Item | Function & Relevance to ALCOA+ |

|---|---|

| Controlled Laboratory Notebooks | Bound, pre-paginated notebooks with tamper-evident features provide an original, enduring medium for recording attributable data [31]. |

| Permanent Ink Pens | Use of indelible black ink ensures records are legible and permanent, preventing degradation or alteration over time [31]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Materials with certified purity and traceability are essential for generating accurate and reliable calibration data [29]. |

| Calibrated Volumetric Glassware & Balances | Equipment regularly calibrated against traceable standards is fundamental for accurate measurement and data integrity [29] [25]. |

| Validated Chromatography Data System (CDS) | A validated CDS enforces contemporaneous data capture, maintains complete audit trails, and ensures data is consistent and available [22] [25]. |

| Secure Electronic Archives | Validated long-term storage systems ensure data remains enduring, available, and complete throughout its required retention period [26] [25]. |

Regulatory Foundation and Consequences

The ALCOA+ principles are embedded within the regulations of major international regulatory bodies, including the FDA (21 CFR Parts 11, 210, 211), EMA (Annex 11), and WHO (TRS 996) [22] [24]. Regulatory agencies conduct inspections with a focus on data integrity, and failures can lead to severe consequences, including warning letters, rejection of regulatory submissions, and consent decrees [28] [27]. Analysis indicates that a significant majority of FDA warning letters cite data integrity violations, highlighting its status as a top enforcement priority [28].

Implementing a Culture of Data Integrity

Technical controls are insufficient without a strong organizational culture of quality. The diagram below outlines the feedback loop for maintaining data integrity.

Diagram 2: The organizational lifecycle for sustaining data integrity.

Effective implementation requires:

- Management Responsibility: Leadership must allocate sufficient resources and establish a zero-tolerance policy for data manipulation [22].

- Procedures and Systems: Implement validated electronic systems with audit trails and controlled procedures for paper-based records [22] [31].

- Training: Conduct regular, role-specific training on GDocP and ALCOA+ principles to ensure all personnel are competent [22] [30].

- Audits and Monitoring: Perform routine data integrity audits and reviews of audit trails as part of a risk-based monitoring strategy [22] [28].

- Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA): Address any identified gaps or deviations with robust CAPA processes to drive continuous improvement [22] [31].

For the analytical chemist, the ALCOA+ principles are not abstract regulatory concepts but practical, daily requirements for ensuring the integrity of every data point generated. By rigorously applying these principles through Good Documentation Practices, researchers and drug development professionals build a foundation of trust in their data. This commitment to data integrity is fundamental to meeting regulatory obligations, making sound scientific decisions, and, ultimately, ensuring the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products for patients.

Implementing GLP in the Laboratory: Analytical Techniques and Standard Procedures

Within the framework of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), the rigorous characterization of a test article is a foundational prerequisite for any nonclinical laboratory study intended to support regulatory submissions for products such as human and animal drugs, biologics, and medical devices [4] [32]. GLP is a quality system that governs the organizational processes and conditions under which these pivotal nonclinical safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, reported, and archived [4]. The primary goal is to assure the quality and integrity of the safety data filed with regulatory agencies like the U.S. FDA and the EPA, thereby protecting public health [2] [32].

Test article characterization provides the critical baseline data that defines the material being evaluated in safety and toxicology studies. According to 21 CFR Part 58, characterization must include, at a minimum, the determination of the test article's identity, strength, purity, and composition, along with any other characteristics that appropriately define the substance [33] [32]. Failure to adequately characterize the test and control articles according to GLP standards will result in a compliance exception in the final study report, potentially jeopardizing the regulatory acceptance of the entire study [33]. For the analytical chemist, this process involves developing and validating phase-appropriate methods to generate reliable, auditable data that forms the cornerstone of credible safety assessment [4].

Regulatory Framework and Core Principles

Key Regulations and Standards

Test article characterization is mandated under specific sections of GLP regulations. In the United States, the FDA's 21 CFR Part 58 is the central regulation, which applies to nonclinical laboratory studies supporting applications for research or marketing permits for FDA-regulated products [2] [32]. Similarly, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established GLP standards under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) for products under its purview [4] [34]. Internationally, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Principles of GLP have been adopted by member countries, creating a system of Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) that allows studies conducted in accordance with OECD guidelines to be accepted across international borders [2] [35].

While these regulations are broadly similar, key operational differences exist that laboratories must consider. For instance, the EPA typically requires a longer minimum record retention period and a specific Statement of Compliance in the final study report compared to FDA requirements [34].

The Role of the Analytical Chemist in GLP Compliance

Analytical chemists serve as the technical backbone of GLP-compliant test article characterization [34]. Their primary responsibilities encompass two main domains:

- Characterizing the Test Article: The analytical chemist develops methods to determine the identity, strength, purity, composition, and stability of the test article (drug substance) and its formulation (dosing solution) to ensure the material is suitable for the duration of the study [4]. This often involves techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for small molecules [4].

- Bioanalytical Support: For studies requiring it, bioanalytical chemists develop and validate methods to measure the concentration of the drug and its metabolites in biological matrices (e.g., blood, plasma, tissues) collected from test systems, in accordance with guidelines like ICH M10 [4].

A cornerstone of the chemist's role is adherence to Good Documentation Practice. The "ALCOA+" principle—ensuring data is Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available—is rigorously applied [4]. This means all activities, from sample weighing to data analysis, are contemporaneously recorded in an electronic laboratory notebook, with all raw data and documentation retained and archived as per standard operating procedures [4].

The Five Essential Parameters of Characterization

GLP characterization of a test article is built upon five essential points, which collectively ensure the material is fully defined and its quality is maintained throughout a nonclinical study [33].

Table 1: The Five Essential Parameters of GLP Test Article Characterization

| Parameter | Definition | Purpose in GLP Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | Confirmation of the test article's fundamental chemical or biological structure. | Verifies that the correct substance is being studied. |

| Strength | The concentration of the active moiety, or the potency of a biological substance. | Ensures the test system is exposed to the correct and consistent dose. |

| Purity | The quantity of the desired substance relative to impurities, including related substances, residual solvents, and contaminants. | Assesses potential safety impacts from impurities. |

| Composition | For mixtures, the quantitative profile of all major components; for pure substances, confirmation of the stated composition. | Ensures batch-to-batch consistency and defines the material administered. |

| Stability | The capacity of a test article to remain within specified limits of identity, strength, and purity over time under defined storage conditions. | Assigns appropriate storage conditions and validates that article quality persists through study end. |

Identity and Composition

Establishing the identity of a test article is the first and most fundamental step. It confirms that the substance being administered in the study is indeed the intended compound. For chemical entities, this involves using techniques that provide structural information, such as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), which identifies functional groups and molecular structure, and Mass Spectrometry (MS), which provides precise molecular weight and fragmentation patterns [33]. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy (UV-Vis) can also be used to confirm identity based on characteristic absorption spectra [33].

For test articles that are mixtures or formulations, determining composition is critical. This involves quantifying the active ingredient(s) and all major excipients or carriers to ensure the formulation is consistent and accurately represents the material intended for toxicological assessment.

Strength, Purity, and Stability

The strength (or potency) of a test article is typically determined using quantitative analytical techniques. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography is a workhorse method for this purpose, often coupled with various detectors like UV (HPLC-UV) for quantification [4] [33]. For more complex analyses or trace-level quantification, Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry is employed [33].

Purity analysis is closely linked to strength and is designed to detect and quantify impurities that could confound safety results. This involves using separation techniques capable of resolving the main active component from its impurities. HPLC with various detection methods and Gas Chromatography with detectors are commonly used [33]. The purity profile must be established for each batch of the test article used in the study.

Stability assessment is an ongoing process that monitors the test article under its storage conditions and in the dosing formulation (if applicable) throughout the study. This ensures that the concentration of the test article does not change outside established acceptance criteria from the time of manufacture until the last administration to the test system [4]. Stability-indicating methods, which can accurately measure the active ingredient in the presence of its degradation products, are essential for this purpose.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Test Article Characterization

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Application in Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography | HPLC | Quantification of strength, purity, and impurity profiling. |

| Gas Chromatography | GC | Analysis of volatile substances and residual solvents. |