Greenness Assessment of Analytical Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide for Sustainable Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, tools, and applications for assessing the environmental impact of analytical techniques.

Greenness Assessment of Analytical Techniques: A Comprehensive Guide for Sustainable Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, tools, and applications for assessing the environmental impact of analytical techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), compares established and emerging assessment metrics, and presents practical strategies for method optimization and troubleshooting. Through case studies from pharmaceuticals and biomedicine, it demonstrates how to validate and compare the greenness of analytical workflows, offering a clear pathway for integrating sustainability into laboratory practices without compromising analytical performance.

The Principles and Evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry

The substantial energy consumption, waste generation, and use of hazardous solvents associated with traditional analytical methods have prompted a critical shift toward sustainability in laboratories worldwide [1] [2]. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a specialized branch of green chemistry, aiming to minimize the environmental impact of analytical practices while maintaining their efficacy and accuracy [3] [4]. The core philosophy of GAC revolves around reducing or eliminating hazardous substances throughout all stages of chemical analysis, from sample preparation to final determination [2] [3]. This approach has gained significant momentum in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development, where analytical procedures are routinely performed and have substantial cumulative environmental consequences [1] [5].

The Foundation and Principles of GAC

Green Chemistry gained prominence after Paul Anastas and John Warner formulated its twelve principles in 1998, providing a systematic framework for designing safer chemical processes and products [6] [3]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, atom economy, less hazardous synthesis, safer solvent use, and energy efficiency [6]. As these concepts evolved, it became apparent that analytical chemistry required specialized guidelines due to its unique processes and challenges.

Jacek Namieśnik and colleagues subsequently adapted these principles specifically for analytical chemistry, creating the twelve principles of GAC [3] [7]. These principles can be remembered using the acronym SIGNIFICANCE [1] and provide a comprehensive roadmap for developing environmentally benign analytical methods.

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Objective | Example Applications in GAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select direct methods | Avoid sample treatment | Direct chromatographic methods, in-line analysis [1] [2] |

| 2 | Integrate processes | Combine operations | Automated sample preparation and analysis [7] |

| 3 | Normalize samples | Minimize sample size | Micro-extraction techniques, miniaturized devices [1] |

| 4 | Nullify waste | Eliminate waste generation | Solvent-free techniques, recycling [2] |

| 5 | Inherent safety | Choose safer solvents | Use of water, ethanol, or ionic liquids [1] [5] |

| 6 | Generate minimal waste | Reduce waste volumes | Miniaturization, scaled-down processes [2] |

| 7 | Energy efficiency | Minimize energy consumption | Room temperature procedures, microwave-assisted extraction [2] |

| 8 | Automate methods | Reduce manual operations | Automated solid-phase extraction, flow injection analysis [7] |

| 9 | Combine methods | Streamline workflows | Coupled techniques like LC-MS, GC-MS [1] |

| 10 | Choose eco-friendly reagents | Select benign chemicals | Replacement of toxic derivatization agents [5] |

| 11 | Eliminate derivatization | Avoid additional steps | Direct analysis without chemical modification [2] |

| 12 | Natural reagent safety | Prioritize biodegradable materials | Use of biosensors, renewable materials [2] |

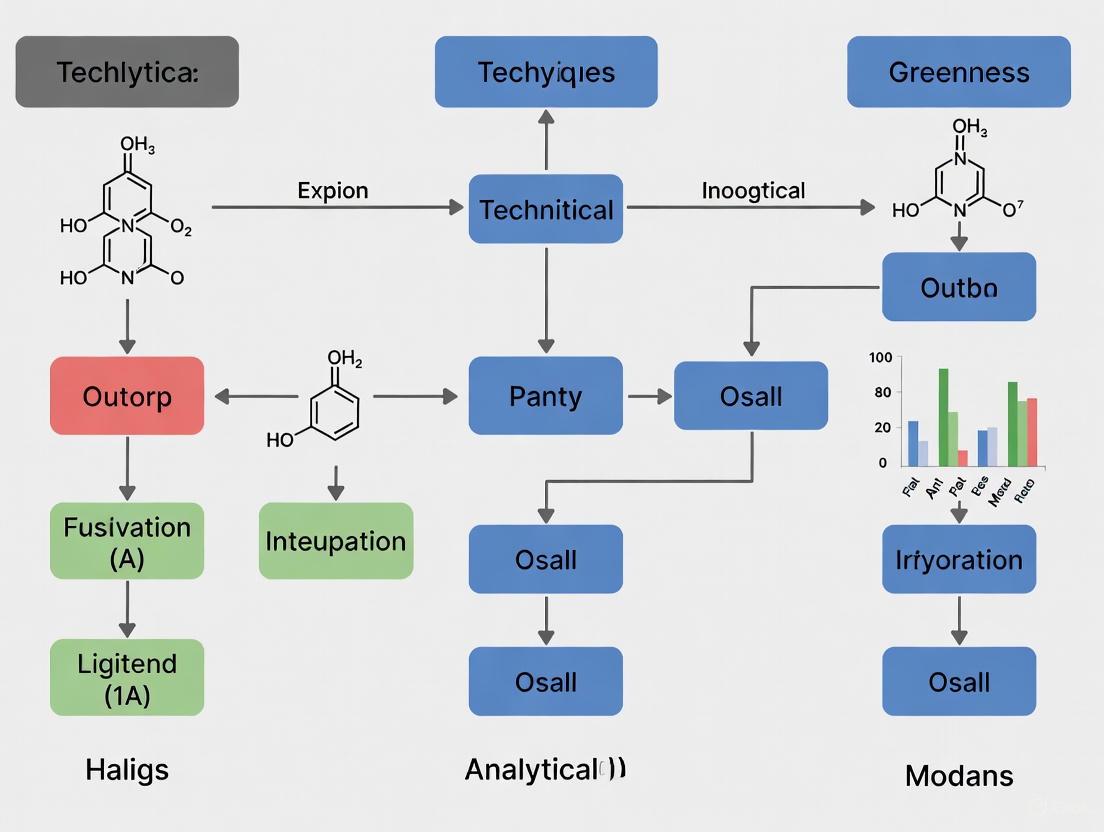

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the core objectives of GAC and their implementation strategies:

Green Analytical Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The pharmaceutical industry represents one of the most active fields for GAC implementation due to its extensive reliance on analytical methodologies for quality control, drug development, and regulatory compliance [1] [2]. Traditional analytical methods in pharmaceutical settings, particularly chromatography, often consume large volumes of organic solvents and generate significant waste—sometimes 1-1.5 liters per day per instrument [1].

Green Sample Preparation Techniques

Sample preparation is often the most polluting step in analytical protocols [1]. Several green sample preparation approaches have been developed to address this challenge:

3.1.1 Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) SPME, developed by Arthur and Pawliszyn in 1990, combines extraction and enrichment into a single solvent-free process [1]. This technique uses a silica fiber coated with an appropriate adsorbent phase to extract analytes directly from samples. SPME offers significant advantages including minimal cost, elimination of solvent disposal expenses, rapid preparation times, and high reliability [1].

3.1.2 QuEChERS Extraction Methodology The QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) approach, established by Anastassiades et al. in 2002, represents a green extraction method that uses minimal organic solvents compared to traditional techniques [1]. The method involves two key steps: solvent extraction using buffer salts and sample clean-up using dispersive solid-phase extraction. This approach has been successfully applied for extracting various pharmaceuticals from blood specimens, including amphetamines, opiates, cocaine, and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [1].

3.1.3 Direct Chromatographic Methods From a GAC perspective, direct analytical techniques that require no sample preparation are particularly desirable [1] [2]. Direct injection of liquid and solid samples can be effectively performed using gas chromatography (GC) or liquid chromatography (LC) analysis [1]. While traditionally discouraged due to potential column damage, advancements in column stationary phase quality and cross-linking strategies have improved resistance to degradation [1]. These direct approaches align with GAC principles by eliminating solvent consumption and reducing analysis time.

Green Chromatographic Techniques

Chromatographic separations constitute a major focus area in GAC due to their prevalent use in pharmaceutical analysis [1] [2]. Several strategies have been developed to green chromatographic methods:

3.2.1 Solvent Consumption Reduction Solvent consumption can be minimized by reducing the mobile phase flow rate through columns with smaller internal diameters [2]. This approach not only decreases solvent use but also improves analytical sensitivity due to reduced solute dilution. Ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) represents another advancement, utilizing reduced particle sizes and shorter column lengths to decrease analysis time and solvent consumption [1] [2].

3.2.2 Temperature Optimization Temperature optimization presents a simpler approach to improving chromatographic efficiency than changing mobile or stationary phase composition [2]. Elevated temperatures can enhance selectivity, efficiency, and detectability, though limitations exist for thermally unstable analytes or silica-based columns above 60°C [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Green Analytical Techniques in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Technique Parameter | Traditional Approach | Green Alternative | Environmental & Efficiency Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Liquid-liquid extraction with organic solvents | Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Solvent-free, reduced waste, faster analysis [1] |

| Extraction Method | Conventional solid-phase extraction | QuEChERS methodology | Minimal solvent use, faster, cheaper [1] |

| Chromatography Type | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Ultra-HPLC (UHPLC) | Reduced solvent consumption, shorter run times, higher resolution [1] [2] |

| Column Dimensions | Conventional columns (e.g., 4.6 × 150 mm) | Narrow-bore columns | Lower mobile phase flow rates, reduced solvent consumption [2] |

| Detection Method | Single technique detection | Multi-analyte determination | Reduced energy consumption per analyte, higher throughput [7] |

| Solvent Type | Acetonitrile, methanol | Water, ethanol, superheated water | Reduced toxicity, better biodegradability [1] [2] |

| Sample Introduction | Extensive sample preparation | Direct analysis | No solvent consumption in sample prep, faster analysis [1] [2] |

Metrics for Assessing Greenness in Analytical Methods

Evaluating the environmental impact of analytical procedures is essential for meaningful progress in GAC. Several metrics have been developed to quantify and compare the greenness of analytical methods [8] [9] [7].

Established Green Metrics

4.1.1 Analytical Eco-Scale The Analytical Eco-Scale is a semi-quantitative assessment tool that assigns penalty points to each element of an analytical procedure that differs from ideal green conditions [9]. The final score is calculated by subtracting penalty points from 100, with higher scores indicating greener methods [9].

4.1.2 Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) GAPI is a pictogram-based metric that evaluates the greenness of analytical methods across five stages: sample collection, preservation, preparation, transportation, and analysis [9] [7]. It uses a color-coded system (green, yellow, red) to visually represent environmental impact at each stage [7].

4.1.3 Analytical Greenness Metric (AGREE) AGREE incorporates the 12 principles of GAC into its assessment framework, providing a comprehensive scoring system from 0 to 1 [9] [7]. This metric generates a circular pictogram with twelve sections, each representing one GAC principle, offering an at-a-glance evaluation of method greenness [7].

Emerging Assessment Tools

4.2.1 GEMAM (Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods) Recently developed in 2025, GEMAM represents a comprehensive, flexible metric based on both the 12 principles of GAC and 10 factors of green sample preparation [7]. This tool evaluates six key aspects: sample, reagent, instrumentation, method, waste generated, and operator safety. GEMAM provides both qualitative (color-coded) and quantitative (0-10 scale) results through a pictogram with seven hexagons [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these green assessment metrics are applied in pharmaceutical method development:

Table 3: Comparison of Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric | Assessment Basis | Scoring System | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale [9] | Penalty points for non-green practices | 0-100 scale (higher = greener) | Simple calculation, quantitative result | No pictogram, does not cover all GAC principles [7] |

| NEMI [7] | Four criteria: persistent, toxic, corrosive, hazardous waste | Pass/Fail for each criterion | Simple pictogram, easy interpretation | Qualitative only, limited scope [7] |

| GAPI [9] [7] | Five stages of analytical process | Color-coded pictogram (green/yellow/red) | Comprehensive lifecycle assessment, visual output | Qualitative only, complex assignment [7] |

| AGREE [9] [7] | 12 principles of GAC | 0-1 scale (higher = greener) | Comprehensive, incorporates all GAC principles | Complex calculation [7] |

| GEMAM [7] | 12 GAC principles + 10 GSP factors | 0-10 scale with pictogram | Comprehensive, flexible weights, qualitative & quantitative | Newer metric, less established track record [7] |

Green Analytical Chemistry in Practice: A Case Study

A recent study demonstrates the practical application of GAC principles in pharmaceutical analysis through the development of green spectrophotometric techniques for analyzing pain relievers containing aceclofenac, paracetamol, and tramadol [5]. This research employed two innovative UV spectrophotometric methods—the double divisor ratio spectra method (DDRSM) and area under the curve (AUC)—to accurately determine drug concentrations in bulk and tablet forms while minimizing environmental impact [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The study successfully replaced traditional chromatography with mathematical solutions for component separation, significantly reducing solvent consumption [5]. Method validation followed International Council for Harmonisation Q2(R1) guidelines, demonstrating linearity across therapeutic ranges for all three compounds [5]. Green metric tool assessment confirmed the environmental sustainability of the proposed methodologies, offering accurate and reliable results for drug determination while aligning with GAC principles [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in green analytical chemistry with their functions and environmental considerations:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Green Alternatives & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) | Mobile phase in chromatography, extraction | Replace with water, ethanol, or superheated water; minimize volumes [1] [2] |

| Derivatization Agents | Analyte modification for detection | Avoid entirely when possible; use milder reagents if necessary [2] |

| Extraction Sorbents (PSA, C18) | Matrix clean-up, analyte isolation | Select biodegradable or reusable sorbents; minimize amounts [1] |

| Buffer Salts (anhydrous MgSO4, NaCl) | QuEChERS methodology | Optimize quantities; consider environmental impact of disposal [1] |

| SPME Fibers | Solvent-free extraction | Reusable fibers; appropriate coating selection [1] |

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry principles represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development. By implementing direct analytical methods, minimizing solvent consumption, utilizing green sample preparation techniques, and applying comprehensive assessment metrics, researchers can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of analytical activities while maintaining methodological rigor and data quality. The continued development of green assessment tools like GEMAM [7] and innovative techniques such as direct chromatographic methods [1] and green spectrophotometry [5] will further advance the field. As GAC continues to evolve, its multidimensional impacts—spanning environmental protection, operator safety, economic benefits, and social responsibility—will increasingly make it an indispensable approach for responsible scientific practice in the pharmaceutical industry and beyond.

Scientific research, particularly in laboratories, is a significant contributor to environmental degradation, creating a paradox where the pursuit of knowledge and solutions inadvertently exacerbates ecological challenges. Traditional laboratory practices come with substantial unintended environmental consequences, including excessive energy consumption, hazardous waste generation, and resource depletion [10]. Analytical laboratories, essential for advancements in pharmaceuticals, environmental monitoring, and materials science, operate with energy intensities that dwarf other sectors; they consume five to ten times more energy than an office building of equivalent size, with this figure rising to 100 times more for facilities with clean rooms and high-process operations [10]. This energy use, coupled with the estimated 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste generated annually from lab activities, positions the scientific enterprise as a substantial contributor to the global carbon footprint and pollution crisis [10]. This document provides a comparative guide to the greenness assessment of analytical techniques, framing this evaluation within the broader thesis that integrating sustainability metrics is no longer optional but essential for the future of responsible scientific research and drug development.

Quantifying the Problem: The Environmental Impact of Laboratories

The environmental impact of laboratories can be systematically categorized using the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which delineates direct and indirect emissions into three scopes [10].

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from refrigerants, on-site electricity generation, heating, and vehicles.

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from purchased electricity for heating or cooling buildings.

- Scope 3: All other indirect emissions across the value chain, including the production of purchased chemicals and materials, travel, and waste disposal.

Within this framework, two pieces of equipment stand out for their disproportionate energy consumption: fume hoods and ultra-low temperature (ULT) freezers. A single fume hood can consume 3.5 times more energy than an average household, while one ULT freezer consumes 2.7 times more energy than an average household (20–25 kWh per day) [10] [11]. The financial and environmental savings from addressing these energy sinks are substantial. For instance, simply raising ULT freezer setpoints from -80°C to -70°C can reduce their energy consumption by 30-40% while maintaining sample integrity for most applications [11]. Furthermore, a case study from the University of Groningen demonstrated that sustainable lab practices could lead to annual savings of €398,763 and 477.1 tons of CO₂ equivalent [10]. A survey by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) revealed a strong appetite among researchers for change, with 84% agreeing they would like to do more to reduce their environmental impact, though significant barriers related to training, data, and time persist [12].

Table 1: Environmental Impact and Savings Potential of Common Laboratory Equipment

| Equipment/Area | Comparative Energy Use | Potential Saving Action | Estimated Saving |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Building | 5-10x more than office space [10] | Holistic efficiency (HVAC, equipment) | 60-65% of a university's total energy [10] |

| Fume Hood | 3.5x an average household [10] | Close sash when not in use | Thousands in annual energy costs per hood [11] |

| ULT Freezer (-80°C) | 2.7x an average household [10] | Increase temp to -70°C | 30-40% energy reduction [11] |

| Laboratory Lighting | N/A | Switch to LED, motion sensors | Up to 75% reduction [11] |

Frameworks for Greenness Assessment: A Comparative Guide

To objectively compare the environmental performance of analytical methods, several metric tools have been developed. These provide a standardized, quantitative basis for evaluating and selecting greener alternatives.

Key Assessment Tools and Metrics

The following tools are central to a rigorous greenness assessment:

- AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric): This comprehensive calculator evaluates methods based on the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (SIGNIFICANCE). It transforms these criteria into a unified score from 0-1 and presents the result in an easily interpretable pictogram, highlighting performance across each criterion [13] [14] [15].

- GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index): Another widely used metric for profiling the environmental impact of an entire analytical procedure, from sample collection to final determination [15].

- White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) / RGB 12 Model: An evolution beyond pure greenness, WAC uses a 12-principle model to evaluate three pillars: Analytical efficiency (Red), Ecological impact (Green), and Practical & economic effectiveness (Blue). Integrating these RGB values produces a "whiteness" score, representing a balanced and sustainable method [14] [15].

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Tools

Table 2: Comparison of Key Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Core Philosophy | Output Format | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE | Green Analytical Chemistry (12 principles) [13] | Pictogram with a 0-1 score [13] | Comprehensive, open-source, flexible user-defined weights [13] |

| GAPI | Holistic procedural impact assessment [15] | Pictogram with qualitative fields | Evaluates all stages of the analytical process [15] |

| White Analytical Chemistry (RGB) | Balances analytical, ecological, and practical merits [14] [15] | RGB values and overall "whiteness" score [14] | Prevents trade-offs where a green method is analytically or practically weak [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Evaluation

Implementing a greenness assessment requires a structured approach. The following protocol outlines the steps for evaluating an analytical method, from data collection to final decision-making.

Protocol for Comprehensive Method Assessment

1. Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the greenness and whiteness of analytical methods to guide the selection of sustainable, efficient, and practical protocols. 2. Materials and Data Requirements: * Detailed method procedure (sample preparation, analysis, disposal). * Quantities of all solvents, reagents, and materials. * Energy consumption data for equipment (e.g., run time, standby power). * Waste streams generated (type and volume).

3. Methodology: * Step 1: Data Collection. Compile all required data for the method under evaluation. For a comparative study, ensure data for all methods being compared is collected consistently. * Step 2: AGREE Analysis. Input the collected data into the AGREE software (available at https://mostwiedzy.pl/AGREE). Assign weights to the principles based on relevance. Record the final score (0-1) and the pictogram [13]. * Step 3: GAPI Analysis. Using the same method data, complete the GAPI assessment, filling out the pictogram for each stage of the analytical process [15]. * Step 4: WAC Analysis. Evaluate the method against the 12 principles of White Analytical Chemistry, scoring its performance in the Red (analytical), Green (ecological), and Blue (practical) domains. Calculate the overall whiteness [14] [15]. * Step 5: Synthesis and Comparison. Compare the outputs of all tools. A method with a high AGREE score (>0.7) and balanced RGB values in WAC represents an ideal sustainable choice. Use the results to identify specific aspects of the method that can be improved (e.g., solvent substitution, energy reduction).

Case Study: HPLC Method with Greenness Integration

A practical example is the development of a green HPLC method for simultaneous determination of four cardiovascular drugs: Nebivolol hydrochloride, Telmisartan, Valsartan, and Amlodipine besylate [14].

- Experimental: The method was developed using a combination of Quality-by-Design (QbD) and Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). The mobile phase was a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water and ethanol, a safer and more sustainable alternative to traditional acetonitrile. A regular ODS column with UV detection was employed [14].

- Greenness Integration: The use of ethanol was evaluated with a Green Solvents Selecting Tool (GSST), confirming its superior sustainability profile [14].

- Assessment Results: The developed method was evaluated with AGREE, an analytical eco-scale, and WAC. The AGREE metric confirmed its alignment with sustainable practices, and the WAC RGB tool demonstrated a favorable balance between analytical quality, ecological impact, and practical efficiency, showcasing a successful implementation of a white method [14].

The Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit for Green Assessment

Transitioning to greener labs requires both conceptual frameworks and practical tools. The following table details key resources for implementing greenness assessments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Greenness Assessment

| Tool / Resource | Function in Greenness Assessment | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE Software | Calculates a standardized greenness score for analytical methods. | Open-source, based on 12 GAC principles, generates interpretable pictogram [13]. |

| Green Solvent Selection Tool (GSST) | Recommends environmentally benign solvents to replace hazardous ones. | Provides a composite sustainability score (G) for solvents, guiding greener choices [14]. |

| My Green Lab Certification | Provides a framework for labs to assess and improve overall sustainability. | Covers energy, water, waste, and procurement; offers a recognized eco-label [11]. |

| White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB Model | Evaluates the whiteness of a method by balancing analytical, ecological, and practical factors. | 12-principle model prevents sub-optimization; ensures method is green, high-quality, and practical [14] [15]. |

The scientific community, particularly in drug development and analytical research, can no longer overlook its own environmental footprint. The imperative for greenness assessment is clear: it provides the quantitative data and standardized frameworks necessary to make informed, responsible decisions about laboratory practices. As demonstrated, tools like AGREE, GAPI, and the WAC RGB model enable researchers to objectively compare techniques, identify improvements, and develop methods that are not only analytically sound but also environmentally benign and practically viable. By embedding these assessments into routine research and development, scientists can lead by example, reducing the ecological impact of their work while continuing to drive innovation. The future of analytical chemistry lies in its ability to be not just precise and accurate, but also sustainable.

The field of analytical chemistry has witnessed a significant transformation with the emergence of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to minimize the environmental impact of analytical activities. The development and adoption of greenness assessment tools have been crucial in this evolution, enabling researchers to evaluate and improve the environmental footprint of their methods. This guide traces the historical progression of these metrics from early simplistic tools to modern comprehensive frameworks, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear comparison of their capabilities, applications, and limitations in the context of analytical techniques research.

The Evolution of Greenness Assessment Tools

Early Foundations: NEMI and Analytical Eco-Scale

The journey toward standardized greenness assessment began with pioneering tools that introduced fundamental concepts for evaluating analytical methods.

National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), developed in 2002, was one of the first greenness assessment tools [16]. Its pictogram is a circle divided into four quarters, with each section colored green only if specific criteria are met: (1) no chemicals used are on the Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic (PBT) list; (2) no solvents are on hazardous waste lists (D, F, P, or U); (3) the pH is between 2 and 12; and (4) waste generated is ≤50 g [16] [17]. While NEMI provides a simple, at-a-glance assessment, it offers only qualitative information and lacks consideration for energy consumption [18] [16].

Analytical Eco-Scale, introduced in 2012, introduced a semi-quantitative scoring approach [16]. It assigns penalty points to various parameters (reagents, waste, energy consumption, occupational hazards) which are subtracted from a base score of 100. The final score categorizes methods as: "excellent green analysis" (score >75), "acceptable green analysis" (score 50-75), or "inadequate green analysis" (score <50) [19] [16]. This tool was a significant advancement as it provided a more nuanced evaluation compared to NEMI's pass/fail system.

Modern Comprehensive Tools: AGREE and GAPI

As GAC principles evolved, more sophisticated assessment tools emerged to address the limitations of earlier metrics.

Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) was introduced in 2018 to evaluate the green character of entire analytical methodologies, from sample collection to final determination [18]. GAPI uses a pentagram design with five colored sections representing different stages of analysis. Each section is colored green, yellow, or red based on the environmental impact of that step. This tool provides a more comprehensive visual assessment than earlier metrics but originally lacked a quantitative scoring system for easy comparison between methods [18] [20].

Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric represents one of the most recent advancements in greenness assessment. This tool incorporates all 12 principles of GAC, assigning scores from 0 to 1 for each principle [14]. The final result is a circular pictogram with an overall score at the center, providing both a comprehensive evaluation and straightforward comparability. AGREE is available as a free software, enhancing its accessibility and ease of use [14].

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary relationships and key characteristics of these assessment tools:

Figure 1: The historical evolution of green assessment tools, showing progression from simple qualitative to comprehensive quantitative approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Tools

Tool Characteristics and Methodologies

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Greenness Assessment Tools

| Tool | Year Introduced | Assessment Approach | Scoring System | Scope of Assessment | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | 2002 [16] | Qualitative | Pass/Fail (4 criteria) | Reagents, pH, waste | No energy consideration; qualitative only [16] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 2012 [16] | Semi-quantitative | Penalty points (0-100) | Reagents, waste, energy, hazards | No severity differentiation for hazards [20] |

| GAPI | 2018 [18] | Semi-quantitative visual | Color coding (green/yellow/red) | Entire analytical procedure | Originally no overall score [20] |

| AGREE | 2020 [14] | Quantitative | 0-1 for each GAC principle | All 12 GAC principles | Requires software input |

| MoGAPI | 2024 [20] | Quantitative visual | Percentage score (0-100%) | Enhanced GAPI with scoring | Less established track record |

Practical Applications and Performance Comparison

Recent research applications demonstrate how these tools perform in evaluating real-world analytical methods:

In a 2024 study comparing methods for cannabinoid analysis in oils, eight HPLC/UHPLC methods were evaluated using multiple metrics. The Analytical Eco-Scale categorized 7 methods as "acceptable" (score 50-73) and one method as "excellent" (score 80), while AGREE and GAPI provided complementary assessments of environmental impact [19].

A green voltammetric method for difluprednate estimation developed in 2024 demonstrated the advantage of modern comprehensive assessment. The method achieved high greenness scores with both GAPI and AGREE, while also excelling in the RGB-12 whiteness assessment, which evaluates analytical and practical factors alongside environmental impact [15].

The integration of green assessment with Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) represents a significant advancement. A 2025 study on Ensifentrine analysis developed an RP-UPLC method using AQbD principles and evaluated its greenness using ComplexMoGAPI, AGREE, and other modern tools, demonstrating how green assessment can be embedded throughout method development rather than merely as a final check [21].

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Method Comparison

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Results for Different Analytical Methods from Literature

| Analytical Method | Target Analytes | NEMI | Eco-Scale Score | GAPI Profile | AGREE Score | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-UV | Sulfadiazine, Trimethoprim | 1/4 green sections | 73 (Acceptable) | 8 green sections | Not reported | [17] |

| Micellar LC | Sulfadiazine, Trimethoprim | 3/4 green sections | 82 (Excellent) | 10 green sections | Not reported | [17] |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Sulfadiazine, Trimethoprim | 2/4 green sections | 68 (Acceptable) | 7 green sections | Not reported | [17] |

| HPLC-DAD | Cannabinoids in oils | Not reported | 80 (Excellent) | Green profile | Favorable | [19] |

| Voltammetry | Difluprednate | Not reported | Not reported | Green profile | 0.81 | [15] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Assessment

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Implementing Greenness Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE Calculator | Software | Evaluates all 12 GAC principles with scoring | Free online available [14] |

| MoGAPI Tool | Software | Enhanced GAPI with quantitative scoring | Free open source [20] |

| Green Solvent Selection Tool | Database | Evaluates solvent sustainability | Free online [14] |

| NEMI Database | Database | Provides chemical hazard information | Publicly accessible [16] |

| ACS AMGS Calculator | Software | Calculates Analytical Method Greenness Score | Online tool [14] |

The historical progression from NEMI and Eco-Scale to AGREE and GAPI demonstrates significant advancements in greenness assessment capabilities. While early tools provided foundational concepts, modern metrics offer more comprehensive, quantitative evaluations that align with all 12 principles of GAC. Current trends indicate a movement toward integrated assessment approaches that combine greenness with other methodological qualities, as seen in White Analytical Chemistry, and the development of specialized software tools to simplify and standardize evaluations. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate assessment tools requires consideration of their specific needs: simpler tools like Eco-Scale for rapid screening, and comprehensive tools like AGREE and GAPI for full methodological evaluation. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of green assessment throughout method development processes represents the most promising approach for advancing sustainable analytical practices.

The scientific community's approach to sustainability has evolved significantly from a singular focus on reducing environmental impact to a more comprehensive vision that balances ecological responsibility with analytical practicality and performance. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a specialized field applying the 12 principles of green chemistry to analytical methods, primarily focusing on minimizing environmental impact through reduced solvent use, waste prevention, and hazard reduction [22]. While groundbreaking, GAC presented limitations by prioritizing environmental aspects over analytical functionality, sometimes leading to trade-offs where greener methods offered reduced sensitivity, precision, or practical applicability [23].

This recognition led to the development of more holistic frameworks. White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) expands beyond GAC's environmental focus to integrate analytical performance and practical/economic considerations into a unified assessment system [24] [23]. Concurrently, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a standardized, quantitative methodology for evaluating environmental impacts across a product or method's entire life cycle—from raw material extraction to disposal [22]. These frameworks represent a paradigm shift toward comprehensive sustainability assessment in chemical research and development, particularly relevant for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex landscape of modern analytical technique selection.

Framework Fundamentals: Principles and Components

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) and the RGB Model

White Analytical Chemistry introduces a tripartite evaluation system known as the RGB model, where each color represents a fundamental aspect of methodological quality [24] [25]:

- Green Component: Encompasses environmental impact and safety parameters, directly inheriting principles from GAC. This includes solvent toxicity, waste generation, energy consumption, and operator safety [24] [26].

- Red Component: Represents analytical performance criteria essential for method validity, including accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity, and robustness [24] [23].

- Blue Component: Addresses practical and economic considerations such as analysis time, cost-effectiveness, instrumental requirements, simplicity of operation, and potential for automation [24] [26].

When these three components are optimally balanced, the method achieves high "whiteness," indicating an ideal combination of environmental responsibility, analytical excellence, and practical feasibility [25].

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Framework

Life Cycle Assessment provides a standardized, quantitative approach for evaluating environmental impacts across all stages of a method or product's life cycle. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) outlines four distinct phases in LCA [22]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Establishing objectives, system boundaries, and functional unit.

- Life Cycle Inventory Analysis: Quantifying energy, material inputs, and environmental releases.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment: Converting inventory data into environmental impact categories.

- Interpretation: Analyzing results, identifying hotspots, and providing recommendations.

LCA moves beyond simple solvent selection to consider cumulative impacts from instrument manufacturing, reagent production, energy consumption during operation, and waste management [27] [22]. This comprehensive scope helps researchers identify improvement opportunities that might be overlooked in simpler greenness assessments.

Complementary Nature of WAC and LCA

WAC and LCA serve complementary roles in sustainability assessment. WAC provides a holistic but primarily qualitative framework balancing environmental, performance, and practical aspects, while LCA offers a rigorous, quantitative assessment of environmental impacts across the entire method lifecycle [22] [23]. Recent advances propose embedding LCA within WAC's green dimension, enriching environmental evaluations with solid quantitative data while maintaining WAC's balanced perspective on performance and practicality [23].

Comparative Analysis: WAC versus LCA in Analytical Chemistry

Framework Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of WAC and LCA

| Feature | White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Balanced integration of environmental, performance, and practical aspects [24] [23] | Comprehensive environmental impact assessment across full life cycle [22] |

| Assessment Scope | Method-level evaluation (focused on analytical procedure) [28] [26] | System-level evaluation (cradle-to-grave) [27] [22] |

| Output Metrics | "Whiteness" score, RGB pictograms, qualitative comparison [25] | Quantitative impact scores (e.g., kg CO₂-eq, human toxicity potential) [27] |

| Time Requirements | Relatively rapid assessment [25] | Data-intensive, time-consuming process [22] |

| Key Strengths | Balances multiple competing method priorities; practical for method selection [24] | Avoids burden shifting; identifies hidden environmental hotspots [27] [22] |

| Limitations | Less quantitative for environmental impacts; limited upstream/downstream scope [23] | Limited consideration of analytical performance; complex implementation [22] |

Experimental Evidence: Framework Applications

Pharmaceutical Analysis Case Study

A 2025 study developed a reversed-phase HPLC method for lidocaine hydrochloride analysis in injectable formulations using WAC principles [28]. The method replaced traditional toxic solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) with ethanol as a greener alternative while maintaining analytical performance [28].

Experimental Protocol:

- Apparatus: HPLC system with diode array detector

- Column: C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Phosphate buffer (pH 4.0):ethanol (75:25 v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.3 mL/min

- Optimization: Experimental design (DoE) with three independent variables: pH, flow rate, and ethanol content

- Validation: ICH guidelines for accuracy, precision, specificity [28]

Results: The WAC-based method achieved comparable analytical performance to conventional methods while significantly improving greenness metrics. Assessment using RGB12, Analytical Eco-Scale, GAPI, and AGREE metrics confirmed superior environmental profile with reduced analysis time, reagent consumption, and cost [28].

Sample Preparation Techniques Case Study

A 2022 LCA study compared two sample preparation techniques: stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) and solid-phase extraction (SPE) [27]. The research quantified environmental impacts using the ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint method, considering consumables, chemicals, and energy requirements for preparing one sample [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Functional Unit: Preparation of one analytical sample

- System Boundaries: Includes consumables, chemicals, energy for sample preparation

- Data Sources: Literature data and laboratory measurements

- Impact Assessment: ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint (H) methodology

- Database: ecoinvent 3.7.1 [27]

Results: SBSE demonstrated lower overall environmental impacts primarily due to reduced chemical consumption. The study identified vial and vial caps as major contributors to impacts and highlighted that spatial location (electricity mix) significantly affected SBSE impacts due to higher electricity consumption [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Sample Preparation Techniques

| Impact Category | SBSE | SPE | Reduction with SBSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | 12.3 g CO₂-eq/sample | 18.7 g CO₂-eq/sample | 34% |

| Human Toxicity | 2.4 × 10⁻⁶ CTUh/sample | 4.1 × 10⁻⁶ CTUh/sample | 41% |

| Fossil Resource Scarcity | 3.7 g oil-eq/sample | 6.2 g oil-eq/sample | 40% |

| Water Consumption | 8.5 L/sample | 14.3 L/sample | 41% |

Synthesis Application: RGBsynt Model for Chemical Reactions

The RGB model has expanded beyond analytical chemistry with the 2025 introduction of RGBsynt for evaluating chemical synthesis methods [25]. This model assesses six key parameters across the three color dimensions:

Red Criteria: Reaction yield and product purity Green-Blue Criteria: E-factor (waste production) Green Criteria: ChlorTox Scale (chemical risk assessment) Blue Criteria: Time-efficiency Green-Blue Criteria: Energy demand [25]

A comparative study applied RGBsynt to 17 solution-based procedures and their mechanochemical alternatives for O- and N-alkylation, nucleophilic aromatic substitution, and N-sulfonylation of amines. Results demonstrated clear superiority of mechanochemistry in both environmental impact (greenness) and overall potential (whiteness), validating the framework's utility for synthetic route selection [25].

Implementation Guide: Applying WAC and LCA in Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Sustainable Analytical Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternatives | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Organic modifier in mobile phases [28] [26] | Replaces acetonitrile and methanol | Lower toxicity, biodegradable [28] |

| Phosphate Buffers | Aqueous mobile phase component [26] | Standard buffer systems | Proper disposal required [26] |

| Mechanochemical Reactors | Solvent-free synthesis [25] | Alternative to solution-based synthesis | Reduced solvent waste, different kinetics [25] |

| Microextraction Phases | Sample preparation [24] | FPSE, magnetic SPE, CPME | Reduced solvent consumption [24] |

| Zobrax Eclipse Plus C18 | HPLC stationary phase [26] | Standard reversed-phase column | Enables ethanol-based mobile phases [26] |

Method Selection and Optimization Workflow

The integration of White Analytical Chemistry and Life Cycle Assessment represents a significant advancement in sustainability evaluation for chemical research and drug development. WAC provides a practical framework for balancing the competing priorities of analytical methods, while LCA offers the rigorous environmental quantification needed to avoid unintended ecological consequences.

Future developments in this field point toward several promising directions. The Green Financing for Analytical Chemistry (GFAC) model has been proposed to address resource-intensive early-stage method development, creating dedicated funds for sustainable analytical innovation [23]. Automated assessment tools like RGBfast (for analytical methods) and RGBsynt (for chemical synthesis) are making comprehensive evaluations more accessible [25]. There is also growing emphasis on integrating social dimensions with economic and environmental assessments to create truly holistic sustainability frameworks [29].

For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these holistic frameworks enables more informed method selection that aligns with both scientific and sustainability goals. The experimental evidence demonstrates that approaches optimizing for "whiteness" frequently achieve superior overall performance while reducing environmental impacts—proving that sustainability and scientific excellence need not be competing priorities but can be mutually reinforcing objectives in modern analytical science.

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the global imperative for environmental responsibility. The foundational concept of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which emerged in 2000, extends the principles of green chemistry to analytical practices, aiming to minimize the environmental impact of analytical procedures [30]. This involves reducing or eliminating hazardous solvents and reagents, decreasing energy consumption, and minimizing waste generation while maintaining robust analytical performance [7] [30]. The drive toward GAC represents a fundamental shift in how scientists approach methodological development, placing environmental impact assessment on par with traditional validation parameters like accuracy, precision, and sensitivity.

Within this context, precisely defining terminology becomes crucial for meaningful scientific discourse and method evaluation. While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, "greenness," "sustainability," and "eco-friendliness" possess distinct meanings and implications for analytical practice. Understanding these nuances enables researchers to select appropriate metrics, implement genuinely improved methodologies, and accurately communicate environmental benefits. This article establishes clear definitions for these key terms within the analytical chemistry domain and provides a practical framework for assessing environmental performance across different analytical techniques.

Defining the Terminology Spectrum

The terms "eco-friendly," "green," and "sustainable" represent a spectrum of environmental consideration, from specific, immediate actions to broad, long-term systems thinking. Their precise definitions are foundational to accurate assessment.

Eco-Friendly: This term describes products, processes, or practices that are not environmentally harmful [31] [32] [33]. In analytical chemistry, an eco-friendly practice directly reduces negative environmental impacts, such as replacing a chlorinated solvent with a less toxic alternative or reducing solvent consumption. The focus is primarily on immediate, direct environmental effects, often at a specific stage of the analytical process [34].

Green: "Green" is a broader, more general term that implies environmental awareness and consciousness [35]. It serves as an umbrella term for the environmental movement but lacks precise, certifiable standards. In a scientific context, stating a method is "green" requires immediate qualification with specific, substantiated claims to have meaningful value and avoid "greenwashing" [32].

Sustainable: Sustainability is the most comprehensive concept, defined as "meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" [32]. It expands beyond immediate environmental impact to encompass a holistic, long-term perspective that balances three interdependent pillars, often called the "Triple Bottom Line" [31] [32]:

- Planet (Environmental): Minimizing harm to natural resources, ecosystems, and biodiversity [31].

- People (Social): Promoting equity, justice, fair labor practices, and community well-being [31] [32].

- Prosperity (Economic): Fostering economic viability without depleting resources or harming the environment, which includes factors like method durability, cost-effectiveness, and energy efficiency [31] [32].

For analytical methods, a sustainable approach would consider the entire lifecycle, from the energy and resources required to synthesize reagents to the end-of-life disposal of waste, while also considering the health and safety of operators and long-term economic feasibility [34] [32].

Logical Relationship of Key Terms

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between "sustainability" and the more specific concepts of "green" and "eco-friendly" in the context of analytical science:

Quantitative Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

The theoretical principles of GAC are operationalized through specific assessment metrics. These tools enable the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of a method's environmental impact, allowing for objective comparison between analytical techniques.

Comprehensive Greenness Assessment Tools

The following table summarizes the most widely used and recently developed comprehensive metrics for evaluating the greenness of entire analytical methods.

Table 1: Comprehensive Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Name | Key Principle | Output Format | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [30] | Four basic criteria (toxicity, waste, corrosivity). | Binary pictogram (pass/fail). | Simple, user-friendly. | Lacks granularity; doesn't assess full workflow. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [30] | Penalty points for non-green attributes. | Numerical score (100 = ideal). | Facilitates direct method comparison. | Subjective penalty assignment; no visual output. |

| GAPI [30] | Entire analytical process from sampling to detection. | Color-coded pictogram (5 parts). | Comprehensive; visually intuitive for impact stages. | No overall score; some subjectivity in color assignment. |

| AGREE [30] | 12 Principles of GAC. | Pictogram & numerical score (0-1). | Comprehensive; user-friendly; enables direct comparison. | Does not fully cover pre-analytical processes. |

| GEMAM [7] | 12 GAC principles & 10 GSP factors. | Pictogram & numerical score (0-10). | Simple, flexible, and comprehensive across 6 sections. | Relatively new metric; requires further validation. |

Specialized and Next-Generation Assessment Tools

To address specific gaps, several specialized metrics have been developed, as summarized below.

Table 2: Specialized and Next-Generation Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric Name | Scope & Focus | Output Format | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep [30] | Sample preparation stage only. | Pictogram & numerical score. | First dedicated tool for sample prep impact. |

| ComplexGAPI/ MoGAPI [30] | Includes pre-analytical processes (e.g., reagent synthesis). | Extended pictogram (with/without score). | Broadens assessment scope to material life cycle. |

| AGSA [30] | Multiple green criteria (toxicity, waste, energy). | Star-shaped diagram & integrated score. | Intuitive visual comparison; combined scoring system. |

| CaFRI [30] | Carbon emissions and climate impact. | Numerical score. | Aligns analytical chemistry with climate goals. |

Experimental Protocol for a Multi-Metric Greenness Assessment

A robust evaluation of an analytical method's greenness involves using complementary metrics to gain a multidimensional understanding. The following workflow formalizes this process, based on a case study evaluating a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method [30].

Detailed Methodology:

Metric Selection: Choose a suite of metrics that provide complementary insights. For a holistic view, a recommended combination includes:

- AGREE or GEMAM: For a comprehensive overview based on the 12 GAC principles [7] [30].

- AGREEprep: If sample preparation is a complex or impactful step, use this for a detailed evaluation of that specific stage [30].

- CaFRI: To specifically assess the method's alignment with climate goals and its carbon footprint [30].

Data Collection: Meticulously compile all quantitative and qualitative data for the analytical method, including:

- Reagents: Type, exact volumes (mL) per sample, hazard classifications (e.g., GHS pictograms), and origin (bio-based vs. synthetic).

- Energy: Power requirements of equipment (kW) and total analysis time to calculate energy consumption per sample (kWh).

- Waste: Total volume of waste generated per sample (mL) and its composition, including any post-analysis treatment or recycling protocols.

- Instrumentation: Degree of automation, scale of operation (e.g., micro-extraction), and sample throughput per hour.

- Operator Safety: Details on hermetic sealing of processes, exposure to vapors, and noise generation.

Score Calculation & Visualization:

- Use the collected data as input for each selected metric. Many metrics, like AGREE and GEMAM, now offer freely available software or calculation sheets [7].

- Generate the respective output for each tool (e.g., the AGREE pictogram, the GEMAM hexagons, the CaFRI score).

Synthesis and Interpretation:

- Cross-Compare Outputs: Analyze the results from the different metrics to identify consistent strengths and weaknesses. For example, a method might score well on AGREE due to miniaturization but poorly on CaFRI due to high energy consumption from a non-renewable grid.

- Identify Improvement Levers: The synthesis pinpoints specific stages or aspects of the method that can be optimized for greater greenness, such as replacing a toxic solvent, implementing waste treatment, or switching to a more energy-efficient detector.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Analysis

Transitioning to greener analytical methods often involves using alternative reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions that can reduce environmental impact.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Greener Analytical Chemistry

| Item / Solution | Function in Analysis | Green Rationale & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-Based Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Cyrene, ethyl lactate) [30] | Extraction, chromatography, cleaning. | Derived from renewable biomass; typically less toxic and biodegradable compared to petrochemical solvents like acetonitrile or dichloromethane. |

| Water as a Solvent | Liquid-liquid extraction, mobile phase. | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and cheap. Techniques like sugaring-out (SULLME) make it viable for extracting a wider range of analytes [30]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Extraction solvents, electrolytes. | Low vapor pressure reduces inhalation hazards and atmospheric pollution. Tunable properties allow for designer solvents with low toxicity. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Sample preparation and concentration. | Solventless technique; eliminates hazardous solvent waste associated with traditional liquid-liquid extraction. Enables miniaturization and automation. |

| Micro-Scale Equipment (e.g., microfluidic chips, µ-SPE devices) | Sample preparation, separation, reaction. | Drastically reduces consumption of samples, reagents, and solvents (often to µL or mg levels), thereby minimizing waste generation [7] [30]. |

The precise distinction between "eco-friendly," "green," and "sustainable" is not merely semantic but fundamental to advancing Green Analytical Chemistry. While "eco-friendly" actions are essential steps, the ultimate goal for researchers and the industry must be true sustainability—developing and implementing analytical methods that are not only environmentally benign but also economically viable and socially responsible throughout their entire lifecycle [31] [32].

The current arsenal of greenness assessment metrics, from comprehensive tools like AGREE and GEMAM to specialized ones like AGREEprep and CaFRI, provides a powerful, multi-faceted framework for this evaluation [7] [30]. By adopting a multi-metric assessment protocol and integrating greener materials and miniaturized technologies, scientists can make informed decisions that significantly reduce the environmental footprint of chemical analysis. This rigorous, data-driven approach is indispensable for aligning the critical field of analytical chemistry with the global pursuit of a sustainable future.

A Practical Guide to Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

The growing emphasis on environmental sustainability has fundamentally transformed analytical chemistry, leading to the establishment of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles. These principles aim to minimize the environmental impact of analytical procedures by reducing toxic reagent use, energy consumption, and waste generation [36]. The assessment and comparison of analytical methods' environmental impact necessitates robust, standardized metrics. This guide provides an objective comparison of five established greenness assessment tools: the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Analytical Eco-Scale, Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE), and AGREEprep [37] [38].

The evolution of these tools reflects a shift from simplistic checklists to comprehensive, quantitative evaluations. While early tools like NEMI offered a basic pictogram, newer metrics like AGREE and AGREEprep provide nuanced scores and detailed visual outputs, enabling researchers to make more informed decisions [36]. These tools are crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who are tasked with developing methods that are not only analytically sound but also environmentally responsible [39].

Metric Comparison Tables

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Year Introduced | Assessment Scope | Scoring System | Visual Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [36] [38] | Early 2000s | Full analytical method | Qualitative (Yes/No for 4 criteria) | Pictogram (4 quadrants) |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [36] [38] | 2012 | Full analytical method | Semi-quantitative (Penalty points from ideal 100) | Total Score (Numerical) |

| GAPI [36] [38] | 2018 | Full analytical method | Qualitative (5 pentagrams, color-coded) | Pictogram (5 sections) |

| AGREE [40] [36] | 2020 | Full analytical method | Quantitative (0-1 scale, 10 criteria) | Circular pictogram (0-1 score) |

| AGREEprep [41] [36] | 2022 | Sample preparation step | Quantitative (0-1 scale, 10 weighted criteria) | Circular pictogram (0-1 score) |

Assessment Criteria and Applicability

Table 2: Detailed Criteria and Practical Application of the Metrics

| Metric | Key Assessment Criteria | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, corrosivity [36] | Simple, quick visual | Overly simplistic, limited criteria [36] | Initial, rough screening |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Reagents, energy, waste [38] | Semi-quantitative, easy calculation | Broad penalty categories can be subjective [36] | Comparing methods with clear operational differences |

| GAPI | Entire method lifecycle from sampling to waste [38] | Comprehensive, detailed pictogram | Complex pictogram, non-quantitative output [36] | In-depth assessment of a full analytical method |

| AGREE | 12 GAC Principles (e.g., waste, energy, toxicity) [40] | Quantitative score, open-access software | Does not weight criteria by importance | Holistic evaluation with a single, comparable score |

| AGREEprep | 10 Green Sample Prep Principles (e.g., solvent choice, waste, energy, throughput) [41] [36] | Quantitative, criteria weighting, specific to sample prep | Focused only on sample preparation | Optimizing the often most polluting step of analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Application

The reliable application of these greenness assessment tools requires a systematic approach. The following methodology outlines the general procedure for applying these metrics, with specific considerations for AGREEprep.

General Assessment Workflow

- Method Deconstruction: Break down the analytical method into its fundamental steps: sample collection, transportation, storage, preparation, instrumentation, and data analysis [36].

- Data Collection: For each step, gather quantitative and qualitative data. This includes, but is not limited to:

- Solvents and Reagents: Types, volumes, and concentrations.

- Energy Consumption: Power requirements of equipment (e.g., heaters, centrifuges) and analysis time.

- Waste Generated: Mass and composition of all waste streams.

- Sample Throughput: Number of samples processed per unit time.

- Hazard Profiles: Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for all chemicals used.

- Tool Selection: Choose the appropriate metric(s) based on the goal of the assessment. AGREEprep is specifically selected when a deep dive into the sample preparation step is required [41] [36].

- Input and Calculation: Enter the collected data into the respective metric's framework, whether it is a manual checklist, a formula, or dedicated software.

- Interpretation and Comparison: Analyze the resulting scores or pictograms to identify environmental hotspots and compare against alternative methods.

AGREEprep Assessment Methodology

AGREEprep is the first tool specifically designed for the sample preparation step, based on the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [36]. Its application involves a detailed protocol:

- Objective: To evaluate the greenness of an analytical sample preparation procedure.

- Principles Assessed: The tool evaluates 10 criteria derived from the GSP principles, including the use of safer solvents, waste minimization, energy consumption, sample size, throughput, and operator safety [36].

- Procedure:

- For each of the 10 criteria, a sub-score between 0 and 1 is calculated based on the method's performance.

- The assessor can assign a weight to each criterion (from 0.5 to 2) to reflect its relative importance, with default weights suggested by the tool's developers [36].

- The software calculates the overall score by combining the weighted sub-scores. This final score ranges from 0 (worst performance) to 1 (best performance or no sample preparation required) [41] [36].

- The output is a circular pictogram with ten colored segments, each representing one criterion, and the overall score displayed in the center. The color of each segment and the center provides an immediate visual cue of performance, from red (poor) to green (excellent) [36].

- Experimental Demonstration: In a case study comparing methods for determining phthalate esters in water, AGREEprep successfully differentiated the greenness of procedures. A traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) using dichloromethane scored significantly lower than a modern, low-solvent method, correctly identifying the LLE method's high environmental impact due to hazardous solvent use [36].

Green Metric Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of green chemistry principles relies on specific materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions used in developing sustainable analytical methods, particularly in chromatography.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Green Analytical Chemistry | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-Water Mobile Phases | Replaces toxic acetonitrile or methanol in Reverse-Phase HPLC [39]. | AQbD-driven HPLC method for Irbesartan using ethanol-sodium acetate mobile phase [39]. |

| Core-Shell or Sub-2µm Columns | Allows for faster separations with lower solvent consumption at reduced backpressures [39]. | Enabling rapid, high-throughput analysis while minimizing mobile phase waste [39]. |

| Biodegradable Sorbents | Used in sample preparation for solid-phase extraction, targeting sustainable and renewable materials [36]. | Micro-extraction techniques that minimize waste and use safer materials [36]. |

| Safer Derivatization Agents | Replaces highly reactive and toxic reagents used to make analytes detectable [36]. | Improving operator safety and reducing the toxicity of chemical waste [36]. |

| Software for AQbD & GAC | Integrates tools for method optimization (DoE) with greenness assessment (AGREE, GAPI) [39]. | Simultaneously achieving robustness and sustainability in method development [39]. |

The landscape of greenness assessment metrics has evolved significantly, offering tools of varying complexity and focus. NEMI and Eco-Scale provide straightforward entry points, while GAPI, AGREE, and AGREEprep deliver increasingly sophisticated, detailed evaluations. For a holistic view, the trend is moving beyond a single metric. The future of analytical method development lies in integrating these greenness tools with other frameworks, such as White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances environmental impact (green) with analytical performance (red) and practicality (blue) [40] [38]. Tools like the Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) are emerging as complements to green metrics, enabling scientists to make fully informed decisions that do not sacrifice functionality for sustainability [40].

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles has become a pivotal aspect of modern method development, driven by the need to minimize the environmental impact and health hazards associated with analytical procedures [7]. Greenness assessment metrics provide a structured framework for evaluating the environmental footprint of analytical methods, enabling researchers to make informed decisions that align with sustainability goals [42]. These tools have evolved significantly from basic checklists to sophisticated scoring systems that quantify greenness across multiple dimensions of the analytical process [38].

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric represents a significant advancement in this field by offering a comprehensive, quantitative assessment tool based directly on the 12 principles of GAC [43]. Unlike earlier metrics that provided primarily qualitative or binary results, AGREE translates complex methodological details into an easily interpretable unified score, facilitating straightforward comparison between different analytical techniques and approaches [43] [42]. This capability is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development and other research fields where method selection requires balancing analytical performance with environmental responsibility.

The AGREE Metric: Core Concepts and Methodology

Theoretical Foundation and the 12 GAC Principles

The AGREE metric is firmly grounded in the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, collectively known by the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic [44]. These principles provide a comprehensive framework that addresses the multifaceted nature of environmental impact in analytical practices. The foundation of AGREE lies in its direct correspondence to these twelve principles, which cover critical aspects including direct analysis techniques, minimal sample size, in-situ measurements, process integration, automation, derivatization avoidance, waste management, multi-analyte determination, energy efficiency, reagent toxicity, operator safety, and accident prevention [43] [44].

AGREE was developed to overcome limitations observed in earlier assessment tools, such as the treatment of criteria as non-continuous functions and the inclusion of only a limited number of assessment criteria [43]. By incorporating all twelve GAC principles and allowing for flexible weighting based on their relative importance in specific analytical scenarios, AGREE provides a more nuanced and adaptable assessment approach. This flexibility is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis, where different analytical techniques and methodologies may prioritize different greenness aspects based on their specific applications and constraints.

Calculation Algorithm and Scoring System

The AGREE calculation algorithm transforms each of the 12 GAC principles into a normalized score on a 0-1 scale, where higher values indicate better environmental performance [43]. The specific criteria for these transformations are detailed in the developer's original publication, with examples provided for principles such as sample treatment and sample size minimization. For instance, Principle 1 (direct analytical techniques) assigns scores ranging from 1.00 for remote sensing without sample damage to 0.00 for external sample pre-treatment with a large number of steps [43].

The final unified score is calculated based on the weighted performance across all twelve principles, resulting in a single value between 0 and 1 [43]. This comprehensive scoring approach is represented mathematically as an aggregation of the individual principle scores, with the algorithm accounting for user-defined weightings to reflect the relative importance of each principle in specific analytical contexts. The software provided for AGREE automates these calculations, making the assessment process straightforward and accessible to researchers without specialized expertise in green metrics [43].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (SIGNIFICANCE) Incorporated in AGREE

| Principle Number | Core Focus | Transformation Basis in AGREE |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Direct analytical techniques | Type of sample treatment required [43] |

| 2 | Minimal sample size and number | Sample volume/number and representativeness [43] |

| 3 | In-situ measurements | Location of analysis relative to sample source [43] |

| 4 | Integration of processes | Degree of operational integration [43] |

| 5 | Automated & miniaturized methods | Level of automation and miniaturization [43] |

| 6 | Derivatization avoidance | Need for and type of derivatization [43] |

| 7 | Waste generation avoidance | Volume and hazard of waste produced [43] |

| 8 | Multi-analyte determination | Number of analytes determined per run [43] |

| 9 | Energy consumption minimization | Energy requirements of instrumentation [43] |

| 10 | Reagent toxicity | Toxicity and environmental impact of reagents [43] |

| 11 | Operator safety | Occupational hazards and exposure risks [43] |

| 12 | Accident prevention | Potential for and consequences of accidents [43] |

Output Interpretation and Pictogram Features

AGREE presents assessment results through an intuitive clock-like pictogram that provides both a unified overall score and detailed performance information across all principles [43]. The center of the pictogram displays the final score (0-1) with a color code ranging from dark green (excellent greenness) to red (poor greenness), enabling immediate interpretation of the method's overall environmental performance [43]. This visual representation allows researchers to quickly gauge whether an analytical procedure aligns with green chemistry objectives without delving into technical details.

The twelve segments surrounding the central score correspond to each GAC principle, with color-coded performance indicators (green-yellow-red) showing the method's performance for each individual criterion [43]. Additionally, the width of each segment visually represents the weight assigned to that principle by the user, communicating the relative importance of different greenness aspects in the specific assessment context. This multi-layered output format enables researchers to identify not only overall greenness but also specific strengths and weaknesses in their analytical methods, guiding targeted improvements for enhanced environmental performance [43].

Comparative Analysis of AGREE Against Other GAC Metrics

The landscape of greenness assessment metrics has expanded significantly, with multiple tools available for evaluating analytical methods [42]. The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) uses a simple pictogram with four binary criteria but lacks granularity and quantitative scoring [43] [42]. The Analytical Eco-Scale provides a quantitative approach by subtracting penalty points from a base of 100, but it does not offer the visual impact of pictogram-based tools [20] [42]. The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) employs a colored pentagram to visualize impacts across five methodological areas but originally lacked a unified numerical score for direct comparison, though modifications like MoGAPI have addressed this limitation [20].

More recent developments include GEMAM (Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods), which incorporates both the 12 GAC principles and 10 green sample preparation factors, presenting results on a 0-10 scale through a hexagonal pictogram [7]. The RGB model expands beyond environmental considerations alone by incorporating analytical performance (red) and productivity (blue) alongside greenness (green) in an additive color model [43]. Each tool offers distinct advantages depending on the assessment priorities, with selection influenced by factors such as desired output type, assessment comprehensiveness, and application specificity.

Direct Comparison of Metric Characteristics

AGREE distinguishes itself through its direct alignment with all 12 GAC principles and its balanced combination of comprehensive assessment with user-friendly output [43]. The table below provides a systematic comparison of AGREE against other major greenness assessment metrics, highlighting key differences in approach, output, and application.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Assessment Basis | Output Type | Scoring System | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [43] | 12 GAC principles | Pictogram + unified score (0-1) | Quantitative | Comprehensive criteria; Flexible weighting; Intuitive visual output | - |

| NEMI [43] [42] | 4 binary criteria | Pictogram (filled/unfilled quarters) | Qualitative | Extreme simplicity | Limited criteria; Binary assessment; No quantitative score |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [20] [42] | Penalty points | Numerical score (0-100) | Quantitative | Simple calculation; Clear acceptability thresholds | No pictogram; Less visual impact |

| GAPI [20] | 5 methodological areas | 5 colored pentagrams | Semi-quantitative | Detailed visual assessment | Originally no unified score (addressed in MoGAPI) |

| GEMAM [7] | 12 GAC principles + 10 GSP factors | Hexagonal pictogram + score (0-10) | Quantitative | Incorporates sample preparation specifically | Less established track record |

| RGB [43] | GAC principles + performance + productivity | Color combination | Semi-quantitative | Balances greenness with practical performance | Less focus on pure environmental impact |

Performance Evaluation in Method Assessment

Comparative studies applying multiple metrics to the same analytical methods reveal how different tools highlight various aspects of greenness while generally converging in their overall assessments [42]. In one evaluation of five different analytical methods using sixteen greenness metrics, all tools showed nearly identical conclusions regarding method greenness, demonstrating consensus despite different assessment approaches [42]. This consistency validates the fundamental principles shared across metrics while highlighting how tool selection might emphasize different greenness dimensions.

AGREE particularly excels in pharmaceutical analysis contexts where the comprehensive nature of its assessment aligns well with regulatory requirements and quality-by-design principles [38]. The ability to weight different principles according to specific analytical needs makes it adaptable to various scenarios within drug development, from active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) quantification to impurity profiling and bioanalysis [38]. The quantitative output further supports objective comparison of method alternatives during development and optimization phases.

Practical Implementation and Case Studies

AGREE Software and Assessment Procedure

The AGREE metric is supported by freely available, open-source software that streamlines the assessment process [43]. The software guides users through inputting relevant methodological details corresponding to each of the 12 GAC principles, with built-in algorithms automatically calculating scores and generating the characteristic pictogram [43]. This accessibility has contributed significantly to AGREE's adoption across various analytical chemistry domains, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis where objective greenness assessment is increasingly valued.