Hard vs Soft Ionization in Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a thorough exploration of hard and soft ionization techniques in mass spectrometry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Hard vs Soft Ionization in Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of hard and soft ionization techniques in mass spectrometry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the fundamental principles governing ionization energy and molecular fragmentation, details the mechanisms and specific applications of major techniques including EI, CI, ESI, MALDI, APCI, and APPI, offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing methods for complex biological samples, and delivers a comparative framework for informed technique selection to enhance analytical accuracy and efficiency in biomedical research.

Core Principles of Ionization: Understanding Energy, Fragmentation, and Molecular Integrity

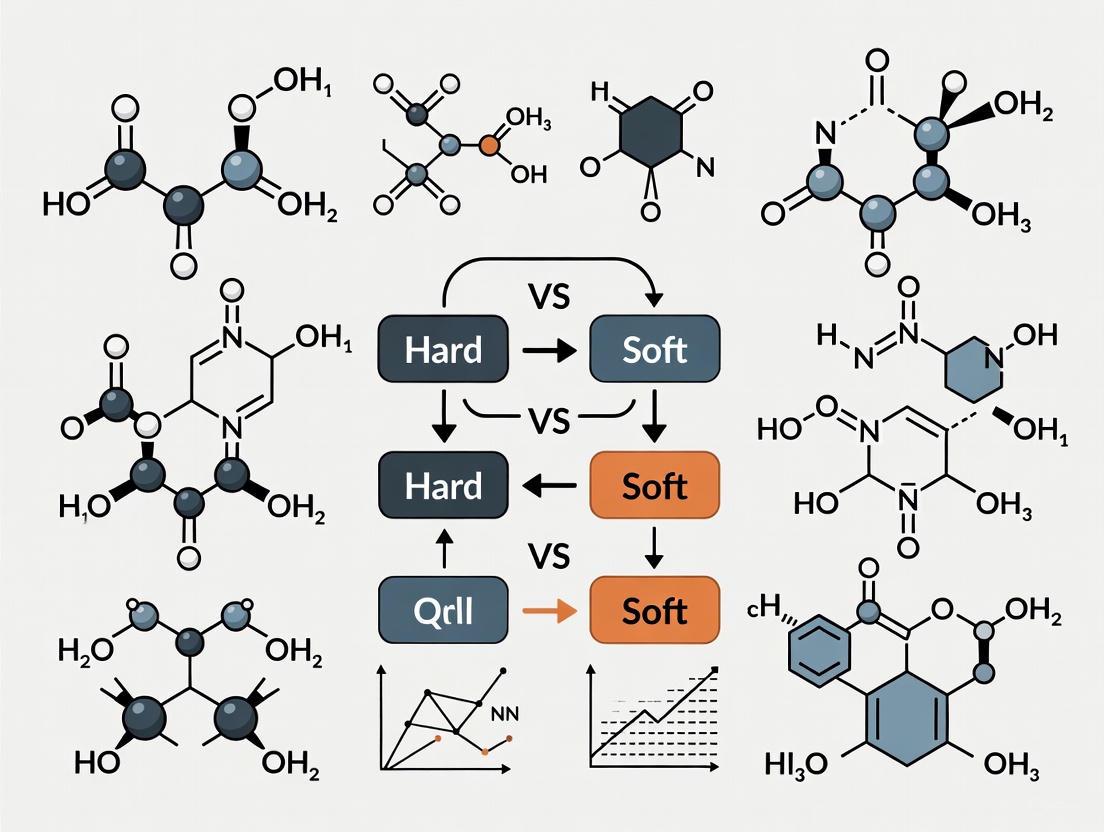

In mass spectrometry, ionization is the foundational process that converts neutral molecules into gas-phase ions, enabling their analysis based on mass-to-charge ratios. The energy imparted during this process creates a fundamental dichotomy in analytical outcomes, classifying ionization methods as either "hard" or "soft" [1] [2]. This division represents more than a technical distinction—it defines the very nature of the mass spectral data obtained, influencing fragmentation patterns, analytical applications, and informational content [3].

Hard ionization techniques impart substantial internal energy to analyte molecules, resulting in significant fragmentation that produces numerous fragment ions. Conversely, soft ionization methods transfer minimal energy, preferentially generating intact molecular ions with little to no fragmentation [1] [4]. This energy dichotomy directly dictates the choice of ionization technique for specific analytical challenges, from small molecule structural elucidation to macromolecular weight determination [5].

Theoretical Framework: Energetics and Ion Formation

Fundamental Energy Transfer Mechanisms

The distinction between hard and soft ionization originates from the physical mechanisms of energy transfer at the molecular level. In electron ionization (EI), a classic hard technique, high-energy electrons (typically 70 eV) bombard gaseous molecules, causing electron ejection and creating radical cations (M⁺•) with substantial excess energy [3] [6]. This energy redistributes throughout the molecular structure, exceeding bond dissociation energies and resulting in extensive fragmentation [7].

In contrast, soft ionization techniques employ gentler energy transfer mechanisms. Electrospray ionization (ESI) uses field-assisted nebulization to produce charged droplets that undergo solvent evaporation and Coulombic fission, ultimately yielding gas-phase ions through desolvation [1] [3]. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) employs a light-absorbing matrix to mediate energy transfer from laser pulses, enabling desorption and ionization with minimal thermal degradation [1] [4]. Both processes deposit significantly less internal energy into the analyte molecules, thereby preserving molecular integrity.

The Fragmentation Continuum

The degree of fragmentation exists along a continuum directly correlated with internal energy deposition. As illustrated in Table 1, this fragmentation behavior systematically differentiates hard and soft ionization techniques across multiple parameters.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Hard versus Soft Ionization

| Parameter | Hard Ionization | Soft Ionization |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Transfer | High-energy direct electron bombardment | Low-energy processes (proton transfer, laser desorption) |

| Typical Internal Energy | >10 eV (significantly above dissociation thresholds) | <5 eV (below most dissociation thresholds) |

| Primary Ions Formed | Fragment ions, radical cations | Molecular ions ([M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻) |

| Molecular Ion Visibility | Often absent or low abundance | Predominant spectral feature |

| Structural Information | Extensive from fragmentation patterns | Limited without tandem MS |

| Mass Range Effectiveness | Low to medium (<600 Da) [1] | Very broad (to >100,000 Da) |

Hard Ionization Techniques: Mechanisms and Applications

Electron Ionization (EI)

Experimental Protocol for EI

Principle: Gas-phase analyte molecules interact with high-energy electrons, resulting in electron ejection and molecular ion formation followed by fragmentation [3] [6].

Procedure:

- Sample Introduction: Introduce volatile, thermally stable sample into ionization chamber via gas chromatography inlet or direct insertion probe [5] [6].

- Vaporization: Heat sample to convert to gaseous state (typically 150-300°C depending on analyte volatility).

- Electron Generation: Heat filament (typically tungsten or rhenium) to thermoemissive temperature (~2000°C) [7].

- Electron Acceleration: Apply 70 eV potential between filament and anode to accelerate electrons [6] [7].

- Ionization: Bombard gaseous analyte molecules with electron beam, resulting in electron ejection:

- Fragmentation: Allow excited molecular ions to undergo unimolecular decomposition into fragment ions.

- Ion Extraction: Apply extraction potential to direct ions into mass analyzer.

Critical Parameters:

- Electron Energy: Standardized at 70 eV for reproducible fragmentation patterns and library matching [7] [8].

- Source Temperature: Optimized for sample vaporization without thermal decomposition.

- Trap Current: Typically 100-350 μA, controlling electron flux [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for EI

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Electron Ionization

| Reagent/Component | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Tungsten Filament | Electron source via thermionic emission | 0.1-0.2 mm diameter, heated to ~2000°C [7] |

| Calibration Standard | Mass and intensity calibration | Perfluorotributylamine (PFTBA) or similar fluorinated compound |

| GC Stationary Phases | Sample separation prior to EI | Non-polar to mid-polar phases (5% phenyl polysiloxane) |

| Reference Libraries | Compound identification | NIST, Wiley mass spectral libraries [6] [8] |

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Ionization

Principle: Argon plasma at ~10,000 K thermally ionizes elements, producing primarily singly-charged atomic ions [1] [5].

Applications: Trace element analysis in biological fluids, environmental samples, and geological materials [1].

Soft Ionization Techniques: Mechanisms and Applications

Electrospray Ionization (ESI)

Experimental Protocol for ESI

Principle: Application of high voltage to liquid sample produces charged droplets that undergo desolvation to yield gas-phase ions [1] [3].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve analyte in polar solvent mixture (typically water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) [3].

- Solution Introduction: Pump sample solution through metal capillary (stainless steel or fused silica with metal coating) at flow rates of 1-500 μL/min.

- Voltage Application: Apply high voltage (3-5 kV) to capillary relative to counter electrode [3].

- Taylor Cone Formation: Establish stable cone-jet mode at capillary tip.

- Droplet Formation: Generate fine aerosol of charged droplets.

- Desolvation: Evaporate solvent using heated capillary or countercurrent gas (150-400°C) [3].

- Coulombic Fission: Achieve droplet subdivision via Coulomb explosions as charge density increases.

- Gas-Phase Ion Formation: Liberate desolvated analyte ions (commonly [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻ for singly-charged ions; multiply-charged for macromolecules).

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent Composition: Affects surface tension and conductivity; typically 30-70% organic modifier.

- Flow Rate: Nano-ESI (<1 μL/min) provides enhanced sensitivity.

- Source Temperature: Optimized for complete desolvation without thermal degradation.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)

Experimental Protocol for MALDI

Principle: UV-absorbing matrix mediates energy transfer from laser pulses to facilitate soft desorption and ionization of analyte molecules [1] [4].

Procedure:

- Matrix Selection: Choose appropriate matrix based on laser wavelength and analyte properties (e.g., α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid for peptides, sinapinic acid for proteins).

- Sample Preparation: Mix analyte solution with saturated matrix solution (typically 1000:1 to 5000:1 molar ratio matrix:analyte).

- Co-crystallization: Apply 0.5-2 μL mixture to MALDI target plate and allow to dry, forming homogeneous crystals.

- Plate Loading: Insert target plate into vacuum chamber of mass spectrometer.

- Laser Irradiation: Direct pulsed UV laser (typically N₂ laser at 337 nm) onto sample spot with appropriate intensity (just above ionization threshold).

- Energy Transfer: Matrix absorbs UV energy, undergoes rapid heating/vaporization, and transfers proton to analyte.

- Desorption/Ionization: Analyte molecules eject into gas phase as protonated ([M+H]⁺) or deprotonated ([M-H]⁻) ions.

- Mass Analysis: Typically coupled with time-of-flight (TOF) analyzer for mass measurement.

Critical Parameters:

- Matrix-to-Analyte Ratio: Critical for optimal signal intensity; typically >1000:1.

- Laser Intensity: Adjusted to just above threshold for ion production ("sweet spot").

- Crystal Homogeneity: Affects shot-to-shot reproducibility.

Research Reagent Solutions for MALDI

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MALDI Mass Spectrometry

| Reagent/Component | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CHCA Matrix (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) | Energy absorption for peptides | Saturated in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA, λₘₐₓ ~330-370 nm |

| Sinapinic Acid Matrix | Energy absorption for proteins | Saturated in 30% ACN/0.1% TFA, for higher MW proteins |

| DHB Matrix (2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid) | Energy absorption for carbohydrates, glycoproteins | Saturated in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA, reduced crystallization |

| Stainless Steel Target Plate | Sample substrate | Polished 96-spot or 384-spot formats |

| Calibration Standards | Mass accuracy calibration | Peptide mixtures for low mass, protein mixtures for high mass |

Complementary Soft Ionization Techniques

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI): Similar to ESI but utilizes corona discharge needle to ionize solvent and analyte vapor through gas-phase reactions at atmospheric pressure. Particularly effective for semi-volatile and non-polar small molecules (e.g., steroids, lipids) [1] [5].

Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI): Employs UV light source (krypton or xenon lamp) to ionize molecules via photoionization. Especially useful for non-polar compounds that ionize poorly by ESI or APCI (e.g., polyaromatic hydrocarbons, steroids) [1] [5].

Comparative Analysis: Technical Specifications and Applications

Operational Characteristics Across Techniques

Table 4: Comprehensive Comparison of Ionization Techniques

| Parameter | EI | CI | ESI | MALDI | APCI | APPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Mechanism | Electron bombardment | Chemical reaction | Electrospray, charge residue | Laser desorption | Corona discharge | Photoionization |

| Typely Ions Produced | M⁺• (radical cations) | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ | [M+nH]ⁿ⁺, [M-nH]ⁿ⁻ | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ | M⁺•, [M+H]⁺ |

| Mass Range | <600 Da [1] | <1000 Da | >100,000 Da [1] | >100,000 Da [1] | <1500 Da [1] | <1500 Da |

| Sample State | Gas phase | Gas phase | Liquid solution | Solid matrix | Liquid solution | Liquid solution |

| Fragmentation Level | High (hard) | Low-medium (soft) | Very low (soft) | Very low (soft) | Low (soft) | Low (soft) |

| Multi-charging | No | Rare | Extensive | Minimal | Rare | Rare |

| Coupling | GC-MS | GC-MS | LC-MS | Direct | LC-MS | LC-MS |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent [6] | Good | Good [9] | Moderate [9] | Good | Good |

| Key Applications | Small molecule ID, library searching [6] | Molecular weight determination | Proteins, peptides, biomacromolecules [1] | Intact proteins, polymers, imaging [1] | Small molecules, lipids, steroids [1] | Non-polar compounds, PAHs [1] |

Ionization Energy and Fragmentation Behavior

The relationship between ionization energy and fragmentation patterns represents the core practical manifestation of the hard-soft dichotomy. As illustrated in Figure 1, reducing electron energy in EI from the standard 70 eV to lower values (14-16 eV) demonstrates a clear transition from hard to softer ionization characteristics, with reduced fragmentation and enhanced molecular ion signals [8].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Hybrid and Tandem Approaches

Modern mass spectrometry increasingly leverages the complementary strengths of both hard and soft ionization through hybrid approaches. A common strategy employs soft ionization (e.g., ESI, MALDI) to preserve molecular ions, followed by tandem MS (MS/MS) where selected ions undergo controlled fragmentation through collision-induced dissociation (CID) or other activation methods [1]. This provides both molecular weight information and structural data in a coordinated analytical workflow.

Variable Energy Electron Ionization

Recent technological advances enable variable-energy electron ionization, which allows adjustment of electron energy from conventional 70 eV down to softer ionization conditions (10-20 eV) without significant sensitivity loss [8]. This innovation provides a continuum between hard and soft ionization within a single source, enabling:

- Molecular ion enhancement for compounds that fragment excessively at 70 eV

- Retention of diagnostically useful fragments even at low energies

- Improved signal-to-noise ratios through reduced background fragmentation

- Streamlined method development with software-controlled energy adjustment

This approach is particularly valuable for confirming compound identity, differentiating isomeric compounds, and enhancing detection limits for target analytes [8].

Quantitative Considerations in Ionization Choice

While soft ionization techniques have transformed biomolecular analysis, quantitative applications present specific challenges. Signal suppression/enhancement from matrix effects, ionization efficiency variability, and reduced reproducibility compared to hard ionization techniques require careful methodological consideration [9]. Effective strategies include:

- Stable isotope-labeled internal standards to correct for ionization variability [9]

- Matrix-matched calibration standards to account for suppression effects

- Chromatographic separation prior to ionization to reduce interference [9]

The fundamental energy dichotomy between hard and soft ionization techniques represents a cornerstone principle in mass spectrometry that directly dictates analytical capabilities and outcomes. Hard ionization methods, exemplified by electron ionization, provide extensive structural information through reproducible fragmentation patterns ideal for small molecule identification and library matching. Conversely, soft ionization techniques, including electrospray ionization and MALDI, preserve molecular integrity for accurate molecular weight determination of thermally labile compounds and macromolecules.

The strategic selection between these approaches depends fundamentally on the analytical question: the need for structural detail versus molecular weight information, the size and stability of the analyte, and the required sensitivity and quantitative precision. Emerging technologies like variable-energy electron ionization demonstrate that this dichotomy is not absolute but rather represents a continuum that can be strategically exploited for enhanced analytical capability.

As mass spectrometry continues to evolve, the fundamental principles of energy transfer during ionization remain essential for method development across diverse applications from pharmaceutical analysis to clinical diagnostics and omics research. Understanding this core dichotomy enables researchers to maximize informational yield from mass spectrometric analysis through appropriate ionization technique selection.

The Impact of Ionization Energy on Molecular Fragmentation Patterns

The energy transferred during the ionization process fundamentally dictates the degree of molecular fragmentation observed in mass spectrometry, creating a central dichotomy between "hard" and "soft" ionization techniques. Hard ionization methods, such as Electron Ionization (EI), impart substantial internal energy, causing extensive fragmentation that provides detailed structural fingerprints for small molecules. In contrast, soft ionization methods, including Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), minimize fragmentation, thereby preserving molecular ions for accurate mass determination of large, labile biomolecules. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic basis of this energy-fragmentation relationship, summarizes its quantitative experimental evidence, and details the methodologies that enable researchers to select the optimal technique for specific analytical challenges in drug development and basic research.

In mass spectrometry (MS), ionization is the process of converting neutral analyte molecules into gas-phase ions. The central thesis is that the amount of energy deposited during this process directly controls the resulting fragmentation pattern. Hard ionization techniques impart high internal energy, leading to significant fragmentation of the molecular ion as it relaxes, producing numerous fragment ions. Soft ionization techniques impart minimal energy, resulting in spectra dominated by the intact molecular ion with little to no fragmentation [1] [10].

This distinction is not merely academic; it dictates the very type of information that can be gleaned from an experiment. Hard ionization, exemplified by Electron Ionization (EI), is invaluable for determining the structure of unknown compounds, as the fragment ions reveal the molecular skeleton. Soft ionization, exemplified by Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), is indispensable for measuring the exact molecular weight of large, non-volatile, and thermally unstable biomolecules such as proteins, peptides, and oligonucleotides [11]. The choice of ionization method is therefore the primary determinant in the experimental design of MS-based analyses in drug development and scientific research.

Mechanistic Insights into Ionization and Fragmentation

Hard Ionization: Electron Ionization (EI)

The EI process involves bombarding vaporized sample molecules with a beam of high-energy electrons (typically 70 eV) emitted from a heated filament. This interaction causes the ejection of an electron from the analyte molecule, forming a positively charged radical cation (M⁺•). The key to its "hard" nature is the significant excess energy transferred beyond the molecule's ionization energy. This energy is distributed as internal vibrational energy, rendering the molecular ion highly unstable [1] [11]. As the excited ion relaxes, this excess energy causes cleavage of covalent bonds, leading to extensive and characteristic fragmentation. The resulting fragments provide a wealth of structural information, and the spectra are highly reproducible, enabling library-based identification [11] [12].

Soft Ionization: ESI and MALDI

Soft ionization techniques employ gentler mechanisms to produce ions without excessive fragmentation.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) operates at atmospheric pressure by applying a high voltage to a liquid sample, creating a fine aerosol of charged droplets. As the solvent evaporates, the charge density on the droplet surface increases until Coulombic fission occurs, eventually leading to the liberation of gas-phase analyte ions. Critically, ionization often occurs via proton transfer ([M+H]⁺) in solution, and the process imparts very little internal energy. A key feature of ESI is the propensity to generate multiply charged ions, which allows the analysis of high-mass biomolecules on mass analyzers with limited m/z range [1] [11].

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) incorporates the analyte into a solid, UV-absorbing matrix. A pulsed laser strikes the matrix, which absorbs the energy and is rapidly vaporized, carrying and ionizing the analyte molecules with it. The matrix acts as an energy mediator, protecting the analyte from direct laser damage and decomposing the energy deposition. This process typically produces singly charged ions and is ideal for analyzing fragile macromolecules with minimal fragmentation [1] [10].

Quantitative Analysis of Fragmentation Patterns

The following tables summarize experimental data that quantitatively illustrates the impact of ionization energy on fragmentation outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Hard vs. Soft Ionization Techniques

| Feature | Hard Ionization (e.g., EI) | Soft Ionization (e.g., ESI, MALDI) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Transfer | High (e.g., 70 eV electrons) | Low (e.g., proton transfer, matrix mediation) |

| Typical Molecular Ion | Unstable, often weak or absent | Stable and dominant ([M+H]⁺, M⁺•) |

| Fragmentation | Extensive | Minimal |

| Primary Information | Structural fingerprint | Molecular mass |

| Ion Charge State | Typically singly charged | Singly (MALDI) or multiply charged (ESI) |

| Ideal Analytes | Small, volatile, thermally stable molecules (<600 Da) [1] | Large, non-volatile, thermally labile biomolecules (proteins, peptides) [11] |

Table 2: Experimental Electron Impact Ionization Cross Sections for CF₄ and CHF₃ Data obtained from recoil-ion momentum spectroscopy, demonstrating measurable fragmentation outcomes from electron impact [13].

| Molecule | Total Single Ionization Cross Section (Maximum) | Double Ionization Cross Section | Key Dissociation Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| CF₄ (Tetrafluoromethane) | ~3.8 × 10⁻¹⁶ cm² (at ~80 eV) | Measured from 20 eV to 1 keV | CF₃⁺, CF₂⁺, CF⁺, F⁺, C⁺ |

| CHF₃ (Fluoroform) | ~3.5 × 10⁻¹⁶ cm² (at ~70 eV) | Measured from 20 eV to 1 keV | CF₃⁺, CHF₂⁺, CF₂⁺, CF⁺, F⁺ |

Analytical Workflow for Fragmentation Pattern Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an ionization technique and interpreting the resulting fragmentation data.

Ionization Technique Selection Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Key Ionization Methods

Protocol for Electron Ionization (EI)

Principle: Gas-phase molecules are ionized via bombardment with high-energy electrons, leading to fragmentation [1] [11].

- Sample Preparation: The sample must be volatile and thermally stable. It is introduced into the ion source in the gas phase, often via a gas chromatograph (GC) or by direct vaporization for solids and liquids.

- Ionization: The vaporized sample is introduced into the ionization chamber, which is under high vacuum (~10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁶ torr) to minimize ion-molecule collisions.

- Electron Bombardment: A heated filament (usually tungsten or rhenium) emits electrons. These electrons are accelerated by a potential of 70 eV into the sample vapor.

- Ion Formation & Fragmentation: Interaction with the electron beam ejects an electron from the analyte molecule, creating a radical cation (M⁺•). The excessive energy causes extensive fragmentation via breakage of covalent bonds.

- Ion Acceleration: The resulting positive ions are repelled out of the ionization chamber by a positively charged plate and focused into the mass analyzer.

Protocol for Electrospray Ionization (ESI)

Principle: Ions are formed from a liquid solution by creating a fine spray of charged droplets at atmospheric pressure, followed by solvent evaporation to yield gas-phase ions [1] [14].

- Sample Preparation: The analyte is dissolved in a volatile solvent (e.g., methanol, water with volatile buffers). It is often introduced via a liquid chromatography (LC) system.

- Nebulization: The liquid sample is pumped through a metal capillary (needle) held at a high voltage (2-5 kV). This creates a fine aerosol of charged droplets.

- Droplet Desolvation: The droplets are directed into a heated desolvation region where a counter-current flow of dry gas (e.g., nitrogen) evaporates the solvent. As the droplets shrink, the charge density increases.

- Ion Evaporation/Coulomb Fission: When the Rayleigh limit is reached, Coulombic repulsion overcomes surface tension, and the droplet undergoes fission into smaller droplets. This process repeats until gas-phase analyte ions are emitted.

- Ion Transfer: The ions are guided through a series of differentially pumped skimmers and/or ion funnels into the high-vacuum region of the mass spectrometer.

Protocol for Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)

Principle: A UV-absorbing matrix is used to desorb and ionize the analyte from a solid sample with a pulsed laser, minimizing fragmentation [1] [11].

- Sample and Matrix Preparation: The analyte is mixed in large excess (e.g., 1:1000 to 1:50000) with a suitable matrix compound (e.g., α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid for peptides). The matrix must strongly absorb at the laser wavelength.

- Co-crystallization: A small volume (e.g., 0.5-2 µL) of the analyte-matrix mixture is spotted onto a metal target plate and allowed to dry, forming a heterogeneous crystal lattice.

- Laser Desorption/Ionization: The target is placed in the high-vacuum ion source. A pulsed UV laser (e.g., N₂ laser at 337 nm) is fired at the crystals. The matrix absorbs the laser energy, leading to rapid heating and vaporization of the matrix and analyte.

- Proton Transfer: In the hot, expanding plume, the matrix donates a proton to the analyte molecules (e.g., [M+H]⁺), creating ions with minimal fragmentation.

- Ion Extraction: A voltage applied to the target plate accelerates the ions into the mass analyzer, typically a Time-of-Flight (TOF) instrument.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mass Spectrometry Ionization Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| EI Filament | Heated metal wire (e.g., Tungsten, Rhenium) that emits electrons. | Source of electron beam in EI sources [11]. |

| ESI Capillary | Metal needle (e.g., stainless steel) held at high voltage. | Creates the charged aerosol spray in ESI [1]. |

| MALDI Matrix | UV-absorbing organic acid (e.g., CHCA, DHB, Sinapinic Acid). | Protects analyte, facilitates desorption/ionization [1] [11]. |

| MALDI Target Plate | Conductive plate (often stainless steel) for sample spotting. | Holds the sample-matrix co-crystals for laser irradiation [1]. |

| Reagent Gas (for CI) | Small molecule gas (e.g., Methane, Ammonia, Isobutane). | Ionized to create plasma for proton transfer to analyte in Chemical Ionization [11]. |

| Nebulizer Gas | Inert, dry gas (e.g., Nitrogen). | Aids in droplet formation and solvent evaporation in ESI and APCI [1]. |

The direct correlation between ionization energy and molecular fragmentation patterns is a cornerstone of modern mass spectrometry. The strategic selection of a hard or soft ionization technique allows scientists to tailor the analytical output to their specific needs—whether that is deriving detailed structural information from fragment ions or obtaining an accurate molecular weight for an intact macromolecule. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms and their associated experimental protocols is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to effectively leverage mass spectrometry for compound identification, structural elucidation, and the characterization of complex biologics.

Why Ionization Choice is Crucial for Mass Spectrometer Detection

Mass spectrometry (MS) plays a vital role in diverse fields, from diagnosing illnesses and detecting food contaminants to drug development and forensic science [15] [14]. The technique fundamentally relies on measuring the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of gas-phase ions. Since mass spectrometers can only detect and manipulate charged species, the process of converting neutral sample molecules into ions—ionization—is the critical first step that enables all subsequent analysis [3] [1]. The choice of ionization method directly determines the types of molecules that can be studied, the quality of information obtained, and ultimately, the success or failure of an analytical experiment.

This technical guide examines ionization techniques through the fundamental framework of hard versus soft ionization, a classification based on the amount of internal energy transferred to the analyte during the ionization process [3] [14]. This energy transfer dictates the degree of molecular fragmentation, which in turn shapes the analytical strategy. Researchers and drug development professionals must understand these principles to select the optimal ionization source for their specific application, whether it involves characterizing small organic molecules, quantifying trace metals, or identifying large, labile biomolecules.

Fundamental Principles: Hard vs. Soft Ionization

The primary classification of ionization techniques in mass spectrometry hinges on the internal energy imparted to the analyte molecule, categorizing them as either "hard" or "soft" [3].

Hard Ionization

Hard ionization techniques impart a relatively large amount of energy to the analyte molecule, typically causing extensive fragmentation by breaking covalent bonds [3] [1]. This process generates a mass spectrum containing not only the molecular ion (M⁺•) but also numerous fragment ions. While the molecular ion provides the molecular weight, the fragment ions provide a "fingerprint" that can be highly informative for determining the chemical structure of an unknown compound [15] [1]. A classic example of a hard ionization method is Electron Ionization (EI).

Soft Ionization

In contrast, soft ionization techniques impart minimal energy, resulting in little to no fragmentation of the analyte [3] [14]. The resulting mass spectrum is often much simpler, dominated by a peak representing the intact, protonated ([M+H]⁺) or deprotonated ([M-H]⁻) molecule. This allows for straightforward determination of molecular weight, which is crucial for analyzing large, complex molecules like proteins and peptides that might otherwise decompose under harsher conditions [15] [16]. Common soft ionization methods include Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI).

The following conceptual workflow illustrates how an analyst's goal dictates the choice between hard and soft ionization, leading to different spectral outcomes and information content.

A wide array of ionization techniques has been developed to handle different sample types and analytical requirements. These methods can be broadly grouped into gas-phase, desorption, and spray-based techniques.

Gas-Phase Ionization Methods

These methods require the analyte to be in the vapor phase prior to ionization.

3.1.1 Electron Ionization (EI) EI is a classic hard ionization method. The sample is vaporized and introduced into a vacuum, where it is bombarded by a high-energy (typically 70 eV) beam of electrons emitted from a heated filament [15] [3] [1]. This interaction ejects an electron from the analyte molecule (M), producing a positively charged radical cation (M⁺•). The process can be summarized as: M + e⁻ → M⁺• + 2e⁻ [3] The high internal energy often leads to significant fragmentation, generating a complex spectrum rich in structural information [15]. EI is robust and reproducible but is generally limited to relatively volatile, thermally stable, low-to-medium molecular weight compounds (< 600 Da) [1]. It is most commonly coupled with Gas Chromatography (GC) [15] [17].

3.1.2 Chemical Ionization (CI) CI is a softer alternative to EI. In CI, a reagent gas (e.g., methane, ammonia, or isobutane) is introduced into the ionization chamber at a high pressure and ionized by an electron beam [15] [18]. The resulting reagent gas ions (e.g., CH₅⁺ from methane) then undergo ion-molecule reactions with the neutral analyte vapor, typically transferring a proton to form a [M+H]⁺ ion [16] [14]. This proton transfer is a lower-energy process than electron ejection, resulting in minimal fragmentation and a much simpler spectrum that readily reveals the molecular mass [15] [18]. CI is particularly useful for molecules that fragment excessively under EI conditions [1].

3.1.3 Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Ionization ICP is a hard ionization technique used almost exclusively for elemental analysis and trace metal detection [15] [1]. A liquid sample is nebulized into an aerosol and injected into an argon plasma, which operates at extremely high temperatures (5500–6500 K) [15]. This environment efficiently decomposes the sample into its constituent atoms and then ionizes them, typically producing singly charged positive ions (M⁺) [15]. ICP-MS is renowned for its ability to ionize almost all elements in the periodic table and is widely applied in environmental, clinical, and geochemical analysis [1].

Desorption Ionization Methods

These techniques are designed to directly ionize molecules from solid or liquid surfaces.

3.2.1 Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) MALDI is a soft ionization technique ideal for large, non-volatile, and thermally labile biomolecules such as proteins, peptides, and polymers [15] [16] [1]. The analyte is first mixed with a large excess of a small, UV-absorbing organic compound (the matrix, e.g., 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid) and allowed to co-crystallize on a metal plate [15] [1]. A pulsed laser (usually a nitrogen laser) is then fired at the sample. The matrix absorbs the laser energy, leading to rapid heating and vaporization of both the matrix and the analyte molecules embedded within it. Ionization occurs in the resulting plume, often via proton transfer from the matrix to the analyte, generating primarily singly charged [M+H]⁺ ions [3] [1]. MALDI is frequently coupled with a Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass analyzer and is a cornerstone of modern proteomics and imaging mass spectrometry [1] [17].

3.2.2 Fast Atom Bombardment (FAB) FAB, another soft ionization technique, was historically important for ionizing non-volatile compounds [15] [17]. The sample is dissolved in a viscous, non-volatile liquid matrix (such as glycerol) and is bombarded with a beam of fast atoms (e.g., Xe or Ar) [15] [14]. This bombardment causes desorption and ionization of the analyte, producing ions like [M+H]⁺ and [M-H]⁻ [15]. While largely superseded by ESI and MALDI due to their higher sensitivity, FAB played a key role in the analysis of polar and thermally unstable molecules [17].

Spray-Based Ionization Methods

These methods ionize molecules directly from a liquid stream at atmospheric pressure.

3.3.1 Electrospray Ionization (ESI) ESI is a tremendously popular soft ionization technique, especially in biological and pharmaceutical research [15] [17]. A solution of the analyte is pumped through a fine metal needle held at a high voltage (3-5 kV), generating a fine mist of charged droplets at atmospheric pressure [3] [1]. As these droplets are directed towards the mass spectrometer inlet, a drying gas and heat cause the solvent to evaporate. The droplets shrink, increasing their charge density until Coulombic explosions occur, eventually releasing gas-phase analyte ions [1]. A key feature of ESI is its ability to produce multiply charged ions ([M+nH]ⁿ⁺), which effectively lowers the m/z ratio of large molecules, making them analyzable by instruments with limited m/z ranges [17]. ESI is easily coupled with Liquid Chromatography (LC) and is ideal for peptides, proteins, and nucleotides [1] [17].

3.3.2 Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) APCI is a soft ionization technique that shares similarities with ESI in its source design. However, the ionization mechanism is different. In APCI, the sample solution is vaporized by a heated nebulizer gas [1] [17]. The resulting gas-phase molecules are then exposed to a corona discharge needle, which ionizes the solvent vapor to create reagent ions (like H₃O⁺) [3] [17]. These reagent ions subsequently ionize the analyte molecules through gas-phase chemical reactions, typically proton transfer, yielding [M+H]⁺ ions [16]. APCI is less "soft" than ESI and can produce some fragment ions. It is well-suited for the analysis of relatively non-polar, thermally stable small molecules with molecular weights generally below 1500 Da, such as lipids and drug metabolites [1].

The table below provides a consolidated comparison of the key ionization techniques discussed.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Common Mass Spectrometry Ionization Techniques

| Ionization Technique | Type (Hard/Soft) | Typical Analyte Classes | Key Mechanism | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) [15] [3] | Hard | Small, volatile, thermally stable organics (<600 Da) [1] | High-energy electron bombardment [3] | GC-MS; structural elucidation of unknowns [15] |

| Chemical Ionization (CI) [15] [18] | Soft | Volatile, polar molecules prone to fragmentation in EI [15] | Ion-molecule reactions with reagent gas plasma [14] | Molecular weight determination [1] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) [15] [1] | Hard | Metals and non-metals (elemental analysis) [1] | Ionization in high-temperature argon plasma [15] | Trace element analysis in clinical, environmental, and geochemical samples [1] |

| Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) [15] [1] | Soft | Large biomolecules (proteins, peptides, polymers), non-volatiles [1] | UV laser desorption/ionization via a light-absorbing matrix [3] | Proteomics, polymer analysis, imaging MS [3] [17] |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [3] [1] | Soft | Peptides, proteins, nucleotides; polar & non-volatile compounds [1] | Coulombic explosion of charged droplets from a liquid jet [1] | LC-MS/MS of biomolecules; analysis of large, non-volatile species [17] |

| Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [1] [17] | Soft | Small, relatively non-polar molecules (<1500 Da) [1] | Corona discharge-induced ion-molecule reactions in gas phase [17] | LC-MS of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and lipids [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Method Selection

Detailed Methodologies

Selecting and implementing an ionization method requires a clear understanding of the experimental workflow. Below are detailed protocols for two of the most pivotal soft ionization techniques in modern bioscience.

4.1.1 Protocol for Electrospray Ionization (ESI) ESI is a multi-stage process that transforms solution-phase ions into gas-phase ions [3] [1].

- Sample Preparation: The analyte is dissolved in a compatible solvent, typically a mixture of water, a volatile organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol), and a small amount of acid (e.g., 0.1% formic acid) to promote protonation [3].

- Droplet Formation: The sample solution is pumped through a metal capillary (needle) held at a high voltage (3–5 kV). The strong electric field pulls the liquid into a fine spray of charged droplets (a "Taylor cone") [3] [1].

- Desolvation: The charged droplets travel through a region against a countercurrent of heated inert gas (desolvation gas). This evaporates the solvent, causing the droplets to shrink and their charge density to increase significantly [3] [1].

- Ion Evaporation / Coulombic Fission: When the Rayleigh limit is reached—the point where Coulombic repulsion overcomes the surface tension of the droplet—the droplet undergoes a "Coulomb explosion," breaking into smaller, daughter droplets. This process repeats until completely desolvated, gas-phase analyte ions are released [1].

- Ion Transfer: The gas-phase ions are guided by electric fields through an orifice or capillary into the high-vacuum region of the mass spectrometer for mass analysis [1].

4.1.2 Protocol for Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) MALDI preparation is a solid-phase technique critical for its success [3] [1].

- Sample and Matrix Preparation: A suitable UV-absorbing matrix (e.g., α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid for peptides) is dissolved in a volatile solvent. The analyte is dissolved in a compatible solvent.

- Co-crystallization: The analyte and matrix solutions are mixed in a specific molar ratio (e.g., 1:1000 analyte-to-matrix) and a small volume (e.g., 0.5-1 µL) is spotted onto a metal target plate. The solvent is allowed to evaporate, forming a homogeneous co-crystal of analyte embedded within the solid matrix [3] [1].

- Laser Irradiation: The target plate is inserted into the vacuum source of the mass spectrometer. A pulsed UV laser (e.g., a 337 nm nitrogen laser) is fired at the crystalline sample. The matrix efficiently absorbs the laser energy [3] [1].

- Desorption and Ionization: The rapid heating caused by the matrix leads to its instantaneous sublimation, carrying intact analyte molecules into the gas phase. The matrix also serves as a proton donor/acceptor, facilitating the ionization of the analyte to form primarily [M+H]⁺ ions with minimal fragmentation [3] [1].

- Mass Analysis: The pulsed nature of the laser makes MALDI ideally coupled with Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass analyzers. The ions are accelerated into the flight tube and separated based on their m/z [1].

A Strategic Framework for Ionization Source Selection

The choice of ionization method is dictated by the physicochemical properties of the analyte and the analytical question. The following decision tree provides a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate technique.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful ionization, particularly in soft and matrix-assisted techniques, relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components for experimental work in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Mass Spectrometry Ionization

| Item | Function / Explanation | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CI Reagent Gases [15] [16] | Ionized to form a plasma of reagent ions (e.g., CH₅⁺) that gently protonate the analyte via ion-molecule reactions, enabling molecular weight determination with minimal fragmentation. | Methane, Ammonia, Isobutane [15] |

| MALDI Matrices [15] [1] | A small, UV-absorbing organic compound that co-crystallizes with the analyte. It absorbs laser energy, facilitating desorption, and donates/accepts a proton to ionize the analyte. | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), Sinapinic acid (SA), α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) [15] [1] |

| ESI Solvents & Additives [3] | The liquid medium for the analyte. Volatile organic solvents aid droplet formation and desolvation. Acids (e.g., formic) promote protonation in positive ion mode. | Water/Acetonitrile or Water/Methanol mixtures with 0.1% Formic Acid or Acetic Acid [3] |

| FAB Matrix [15] | A viscous, non-volatile liquid that dissolves the analyte and helps to dissipate the energy from the atom beam, reducing analyte damage and allowing for continuous refreshment of the sample surface. | Glycerol, 3-Nitrobenzyl alcohol (3-NBA) [15] |

| ICP Plasma Gas [15] | An inert gas that, when energized by a radio-frequency (RF) coil, forms a high-temperature plasma (~5500-6500 K) capable of atomizing and then ionizing virtually any element. | Argon [15] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The evolution of ionization techniques continues to expand the frontiers of mass spectrometry. Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) and Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART), for example, allow for ambient ionization—the analysis of samples in their native state in the open environment with little to no preparation [15]. DART, for instance, uses a metastable helium or nitrogen plasma to excite and ionize analytes from surfaces directly in front of the MS inlet, finding applications in forensics and food analysis [15].

Furthermore, the integration of machine learning (ML) is beginning to refine ionization and compound identification processes. In Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry (CIMS), ML models are being trained to predict whether a compound will be detected and its expected signal intensity based on its molecular structure, helping to decode complex ion-molecule interactions and optimize experimental setups [19]. Public data repositories and visualization tools like vMS-Share and QUIMBI are also becoming crucial for sharing, visualizing, and mining raw MS data, fostering collaboration and accelerating discovery in proteomics and metabolomics [20] [21].

The initial choice of an ionization source is a decisive factor that predetermines the scope and quality of a mass spectrometric analysis. The fundamental dichotomy between hard ionization, which provides detailed structural information through fragmentation, and soft ionization, which preserves the molecular ion for accurate weight determination, forms the cornerstone of this decision. Techniques such as EI, ESI, MALDI, and APCI each possess distinct strengths, mechanisms, and optimal application areas. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these principles is not merely academic—it is an essential prerequisite for designing robust analytical methods, correctly interpreting complex data, and ultimately leveraging the full power of mass spectrometry to solve challenging problems in chemical and biological analysis.

The Historical Evolution of Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) stands as a cornerstone of modern analytical science, providing unparalleled capabilities for determining the molecular weight, structure, and composition of chemical substances. The transformative process that enables this analysis is ionization, the conversion of neutral molecules into charged ions capable of being manipulated by electric and magnetic fields within the mass spectrometer. The evolution of ionization techniques has fundamentally shaped the capabilities and applications of mass spectrometry over more than a century. This progression has been characterized by a pivotal distinction between hard ionization methods, which cause extensive molecular fragmentation and provide detailed structural information, and soft ionization techniques, which preserve molecular integrity and enable the analysis of large, complex biomolecules. The historical journey from early gas discharge experiments to sophisticated contemporary ionization platforms reflects a continuous pursuit of greater analytical precision, sensitivity, and applicability across diverse scientific disciplines from physics to proteomics.

The Early Era: Fundamental Discoveries and Hard Ionization

The foundation of mass spectrometry was laid in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through fundamental investigations into the behavior of charged particles in gaseous phases. In 1886, Eugen Goldstein discovered anode rays (canal rays) in a gas discharge tube, marking the first observation of positive ions that would become the basis for mass analysis [22] [23]. By 1898, Wilhelm Wien demonstrated that these canal rays could be deflected by strong electric and magnetic fields, establishing the principle that the mass-to-charge ratio of particles determined their path [23]. These pioneering experiments set the stage for J.J. Thomson's groundbreaking work in 1912-1913, where he used positive ray analysis to separate neon isotopes (20Ne and 22Ne), providing the first conclusive evidence for the existence of stable isotopes in non-radioactive elements [23].

The period from 1918 to 1940 witnessed the development and refinement of electron ionization (EI, originally known as electron impact ionization) as the first practical ionization method for analytical mass spectrometry. Arthur Jeffrey Dempster constructed a magnetic sector instrument in 1918 that established the basic design principles still relevant to modern mass spectrometers [23]. Simultaneously, Francis W. Aston built the first velocity-focusing mass spectrograph in 1919, enabling him to identify numerous isotopes and formulate the Whole Number Rule, which states that atomic masses are close to integer values [23]. This work earned Aston the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1922 and solidified MS as a powerful tool for isotopic analysis.

Electron Ionization: The Prototypical Hard Ionization Method

Electron Ionization emerged as the dominant ionization technique during the first half of the 20th century and remains important today for specific applications. In the EI process:

- Sample molecules are vaporized and introduced into the ionization chamber under vacuum conditions

- A heated filament (cathode) emits electrons that are accelerated to typically 70 eV energy

- These high-energy electrons bombard gaseous analyte molecules, ejecting electrons and generating positively charged radical cations (M⁺•)

- The excessive energy imparted during this process causes extensive fragmentation of the molecular ion, producing a characteristic fingerprint of fragment ions [3]

Table 1: Characteristics of Electron Ionization

| Parameter | Specification | Analytical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Ionization Energy | 70 eV (typical) | High internal energy transfer causing significant fragmentation |

| Ion Type Produced | Radical cations (M⁺•) | Odd-electron ions prone to fragmentation |

| Sample Requirements | Volatile, thermally stable | Limited to small molecules (<600 Da) |

| Primary Applications | GC-MS of small organic molecules, hydrocarbon analysis, structural elucidation | Provides reproducible spectral libraries |

| Key Limitations | Excessive fragmentation for molecular weight determination; not suitable for non-volatile or thermally labile compounds | Molecular ion often absent or weak in spectra |

The historical significance of EI is profound, as it enabled the first practical applications of MS in petroleum analysis [24] and played a crucial role in the Manhattan Project for uranium isotope separation using calutrons [23]. The reproducible fragmentation patterns generated by EI led to the creation of extensive spectral libraries (e.g., NIST, Wiley), which remain invaluable for compound identification today [8]. However, the limitations of EI for analyzing larger, thermally labile molecules drove the scientific community to develop softer ionization approaches in subsequent decades.

The Soft Ionization Revolution: Enabling Biomolecular Analysis

The 1960s through the 1990s witnessed a paradigm shift in mass spectrometry with the development of soft ionization techniques that generated ions with minimal fragmentation. This revolution was driven by the growing need to analyze large, non-volatile, and thermally labile biomolecules that were intractable to EI. The fundamental distinction between hard and soft ionization lies in the amount of internal energy deposited during the ionization process. While hard ionization techniques like EI typically impart 5-20 eV of energy, causing extensive bond cleavage, soft ionization methods deposit <2 eV, preserving the molecular ion [3] [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Hard versus Soft Ionization Techniques

| Characteristic | Hard Ionization | Soft Ionization |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Transfer | High (5-20 eV) | Low (<2 eV) |

| Fragmentation | Extensive | Minimal |

| Molecular Ion | Often weak or absent | Dominant in spectrum |

| Primary Information | Structural via fragments | Molecular weight |

| Typical Techniques | Electron Ionization (EI) | ESI, MALDI, CI, APCI |

| Ideal Applications | Small molecules, structural elucidation | Large biomolecules, molecular weight determination |

Pioneering Soft Ionization Methods

Chemical Ionization (CI), developed in the 1960s, represented the first significant soft ionization technique. Instead of direct electron bombardment, CI uses reagent gases (e.g., methane, ammonia) that are initially ionized by electrons. These reagent ions then transfer charge to analyte molecules through ion-molecule reactions, producing protonated molecules ([M+H]⁺) with minimal fragmentation [23] [4]. This gentler approach preserved the molecular ion, enabling accurate molecular weight determination for compounds that would extensively fragment under EI conditions.

Field Desorption (FD), introduced by Beckey in 1969, provided another early soft ionization approach, particularly for non-volatile compounds. In FD, a high-potential electric field is applied to an emitter with sharp micro-needles, causing electron tunneling that ionizes analyte molecules deposited on the emitter surface [23]. This technique was especially valuable for hydrocarbons and organometallic compounds that resisted other ionization methods.

Electrospray Ionization: The Electrospray Revolution

The development of Electrospray Ionization (ESI) marked a transformative advancement that earned John B. Fenn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002. Although the electrospray process was investigated by Malcolm Dole in 1968 [25], Fenn's work in the late 1980s demonstrated that ESI could produce intact molecular ions from large proteins by generating multiply charged species [25].

The ESI mechanism involves several stages:

- Sample Introduction: The analyte dissolved in a solvent is pumped through a metal capillary maintained at high voltage (3-5 kV)

- Taylor Cone Formation: The electric field causes the liquid to form a conical shape (Taylor cone) that emits a fine spray of charged droplets

- Droplet Shrinking: Solvent evaporation reduces droplet size while increasing charge density

- Coulombic Fission: Droplets undergo repeated explosions until individual, desolvated analyte ions are released into the gas phase [3]

A critical feature of ESI is the generation of multiply charged ions for macromolecules, which reduces the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) to values within the range of conventional mass analyzers. This innovation enabled the analysis of proteins with molecular weights exceeding 100,000 Da using instruments designed for much smaller m/z ranges [3] [4]. ESI's compatibility with liquid chromatography and its effectiveness for polar compounds made it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications and proteomics research.

Diagram 1: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Workflow

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization: Solid-State Soft Ionization

The nearly simultaneous development of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) provided a complementary soft ionization approach particularly suited to solid samples. While the fundamental principles were described by Karas and Hillenkamp in 1985 [23], the critical breakthrough came in 1987 when Koichi Tanaka of Shimadzu Corp. demonstrated that a mixture of ultrafine cobalt powder in glycerol could serve as a matrix to ionize proteins as large as carboxypeptidase-A (34,472 Da) using a 337 nm nitrogen laser [23] [25]. This achievement earned Tanaka a share of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The MALDI process involves:

- Sample Preparation: The analyte is mixed with a large excess of UV-absorbing matrix compound (e.g., sinapinic acid, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) and co-crystallized on a metal plate

- Laser Irradiation: A pulsed laser (typically 337 nm) irradiates the sample, causing rapid heating and vaporization of the matrix

- Energy Transfer: The excited matrix molecules transfer protons to the analyte molecules, generating predominantly singly charged ions

- Acceleration and Analysis: The ions are accelerated into the mass analyzer, typically a time-of-flight (TOF) instrument [3]

MALDI's unique strength lies in its production of primarily singly charged ions, simplifying spectral interpretation for complex mixtures. This characteristic, combined with its tolerance to buffers and salts, made MALDI particularly valuable for proteomics, polymer analysis, and mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) [4]. The first commercial MALDI-TOF instrument was introduced by Shimadzu in 1988, making the technique widely accessible to researchers [25].

Diagram 2: MALDI Ionization Workflow

Atmospheric Pressure Ionization: Enhancing Practical Utility

The 1980s witnessed another significant advancement with the development of ionization techniques operating at atmospheric pressure, which simplified sample introduction and improved instrument versatility. Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) emerged as a technique particularly suitable for semi-volatile and thermally stable compounds that were less amenable to ESI [3] [4].

In APCI:

- The sample solution is nebulized into a heated chamber (typically 350-500°C) where it is vaporized

- A corona discharge needle creates a plasma of reactant ions from solvent molecules

- Gas-phase ion-molecule reactions between reactant ions and analyte molecules produce protonated molecules ([M+H]⁺)

- Desolvated ions enter the mass spectrometer through a series of pressure-reducing stages [3] [4]

APCI proved particularly valuable for analyzing less polar compounds with intermediate molecular weights, including many pharmaceuticals and lipids. Its higher tolerance for buffer concentrations compared to ESI made it suitable for direct coupling with normal-phase liquid chromatography [4].

Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI) further expanded the range of analyzable compounds by using ultraviolet light instead of corona discharge to initiate ionization. APPI proved especially effective for non-polar compounds such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and steroids that ionized poorly by both ESI and APCI [4].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Ionization Techniques

Electron Ionization Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve analyte in volatile solvent (methanol, dichloromethane, or hexane) at 0.1-1 mg/mL concentration

- For solid samples, use direct insertion probe with temperature programming from ambient to 400°C

- Ensure sample is free of non-volatile salts and buffers to prevent source contamination

Instrument Parameters:

- Electron energy: 70 eV (standard) or 10-20 eV for reduced fragmentation

- Emission current: 100-500 μA

- Source temperature: 150-300°C depending on sample volatility

- Mass analyzer: Typically magnetic sector or quadrupole operated under high vacuum (<10⁻⁵ torr)

Analysis Procedure:

- Introduce 1-2 μL of sample solution via GC inlet or direct insertion probe

- Monitor total ion current to confirm sample vaporization

- Acquire spectra across appropriate mass range (typically m/z 50-800 for small molecules)

- Compare resulting spectrum against reference libraries (NIST, Wiley) for identification [3] [8]

Electrospray Ionization Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve analyte in solvent mixture of water/organic modifier (acetonitrile or methanol) containing 0.1% formic acid or acetic acid

- Ideal concentration: 1-10 pmol/μL for proteins, 0.1-1 μM for small molecules

- Remove salts and buffers via dialysis, desalting columns, or protein precipitation when possible

Instrument Parameters:

- Capillary voltage: 3-5 kV (positive mode) or 2.5-4 kV (negative mode)

- Desolvation temperature: 150-300°C depending on solvent flow rate

- Nebulizing gas: 10-50 psi (nitrogen or air)

- Drying gas: 5-15 L/min (nitrogen)

- Cone voltage: 10-100 V (optimized for each analyte)

Analysis Procedure:

- Infuse sample via syringe pump at 3-10 μL/min or introduce via LC system

- Optimize cone voltage to balance sensitivity and fragmentation

- For proteins, use deconvolution software to transform multiply charged envelope to molecular mass

- For quantification, employ selected ion monitoring (SIM) or multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [3] [4]

MALDI Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare saturated matrix solution in appropriate solvent (e.g., 10 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA)

- Mix analyte solution with matrix solution at 1:1 to 1:10 ratio (v/v)

- Spot 0.5-2 μL of mixture on MALDI target plate and allow to dry completely

- For complex samples, perform on-target washing with cold 0.1% TFA to remove salts

Instrument Parameters:

- Laser wavelength: 337 nm (nitrogen laser) or 355 nm (Nd:YAG laser)

- Laser power: Adjust to just above ionization threshold (typically 10-50% of maximum)

- Pulse rate: 1-200 Hz depending on acquisition time

- Acceleration voltage: 20-25 kV for TOF instruments

- Delayed extraction: Optimized for mass range of interest

Analysis Procedure:

- Acquire spectra from multiple positions across sample spot to account for heterogeneity

- Sum 50-200 laser shots to improve signal-to-noise ratio

- Calibrate using external or internal standards of known mass

- For complex mixtures, employ imaging mode to map spatial distribution [3] [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ionization Techniques

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Compounds | Absorb laser energy and facilitate proton transfer in MALDI | Sinapinic acid (proteins), α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (peptides), DHB (carbohydrates) |

| ESI Solvent Additives | Enhance ionization efficiency and protonation | Formic acid (positive mode), acetic acid, ammonium acetate (volatile buffer), TFA (ion-pairing) |

| CI Reagent Gases | React with analytes to produce stable ions | Methane (soft CI), isobutane (softer CI), ammonia (selective for bases) |

| Calibration Standards | Mass accuracy verification | Perfluorotributylamine (EI), sodium iodide (ESI), peptide mixtures (MALDI) |

| Desalting Materials | Remove interfering salts and buffers | C18 ZipTips, dialysis membranes, size exclusion spin columns |

Contemporary Applications and Future Perspectives

The evolution of ionization techniques has profoundly expanded the applications of mass spectrometry across scientific disciplines. In proteomics, ESI and MALDI enable the identification and quantification of thousands of proteins from complex biological samples [26]. In metabolomics, the combination of ESI, APCI, and APPI permits comprehensive analysis of diverse chemical classes with varying polarities [4]. Pharmaceutical research relies heavily on ESI and APCI for drug metabolism studies, pharmacokinetics, and impurity profiling [14] [4].

Recent innovations continue to push the boundaries of ionization technology. Ambient ionization techniques such as DESI (Desorption Electrospray Ionization) and DART (Direct Analysis in Real Time) allow direct analysis of samples in their native state without preparation [25]. Advances in mass spectrometry imaging combine the spatial resolution of microscopy with the molecular specificity of MS, creating new opportunities for biological discovery [4]. The ongoing development of miniaturized and portable MS systems promises to bring sophisticated analytical capabilities out of the core laboratory and into field applications [26] [25].

The historical evolution of ionization techniques in mass spectrometry demonstrates a remarkable trajectory from fundamental physical studies of gaseous ions to sophisticated methods capable of addressing the most complex analytical challenges in modern science. This progression has been characterized by continuous innovation aimed at expanding mass spectrometry to new classes of analytes, improving sensitivity and precision, and making the technology more accessible to diverse scientific communities. As ionization methods continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new dimensions of analytical capability and further cement mass spectrometry's role as an indispensable tool for scientific discovery.

Technique Deep Dive: Mechanisms, Workflows, and Domain-Specific Applications

In mass spectrometry, the ionization technique is the critical first step that transforms neutral molecules into gas-phase ions, enabling their detection and analysis based on mass-to-charge ratios. Ionization methods are broadly classified into two categories: hard ionization and soft ionization techniques, which differ fundamentally in the amount of internal energy transferred to the analyte molecules during the ionization process [1] [3]. Electron Ionization (EI) stands as the classical representative of hard ionization techniques, characterized by significant molecular fragmentation that provides detailed structural information [27] [1]. Developed in the early days of mass spectrometry, EI remains one of the most widely used ionization methods, particularly for the analysis of volatile, thermally stable small molecules [3] [16].

The distinction between hard and soft ionization represents a fundamental dichotomy in mass spectrometry that directly impacts analytical outcomes. Hard ionization techniques like EI use high ionization energy, which causes extensive fragmentation of the analyte molecules, producing not only the molecular ion but also numerous fragment ions [3]. In contrast, soft ionization techniques such as Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) apply less energy during ionization, resulting in minimal fragmentation and predominantly intact molecular ions [28] [1]. This preservation of molecular integrity makes soft ionization particularly valuable for studying complex biomolecules like proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids [1] [3].

EI's position as a hard ionization technique makes it uniquely suited for applications where structural elucidation is paramount, establishing it as the "gold standard" for volatile small molecule analysis across numerous scientific fields including environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and forensic analysis [1].

Fundamental Principles of Electron Ionization

Mechanism of Ion Formation

Electron Ionization operates through a direct interaction between high-energy electrons and vaporized sample molecules in the gas phase. The process occurs within a specialized ionization chamber maintained under high vacuum conditions (typically 10^-5 to 10^-6 torr) to minimize unwanted collisions between ions and background gas molecules [1] [3]. The fundamental ionization event involves bombarding sample molecules with a stream of high-energy electrons emitted from a heated filament, usually made of tungsten or rhenium. When a molecule (M) intercepts one of these high-energy electrons, the interaction causes the ejection of an electron from the molecule itself, generating a positively charged radical cation represented as M⁺• [3] [16].

The ionization process follows the general equation: M + e⁻ → M⁺• + 2e⁻ [3]

Where:

- M represents the neutral analyte molecule

- e⁻ represents an electron from the high-energy electron beam

- M⁺• is the resulting positively charged radical cation (the molecular ion)

- The second e⁻ is the electron ejected during the ionization process

The energy transfer during this electron-molecule collision is substantial—typically standardized at 70 electronvolts (eV)—which significantly exceeds the energy required merely to ionize the molecule (usually 8-15 eV for organic compounds) [1] [3]. This substantial excess energy deposited into the molecular ion makes it inherently unstable, causing extensive fragmentation through cleavage of chemical bonds within the molecule. The resulting fragmentation pattern creates a distinctive "fingerprint" that provides valuable structural information about the original compound [3].

Instrumentation and Hardware Components

The implementation of Electron Ionization requires specific hardware components that work in concert to generate, direct, and focus the electron beam while maintaining optimal vacuum conditions. The key components of a standard EI source include:

- Heated Filament: Typically made of tungsten or rhenium wire, heated electrically to incandescence (approximately 2000°C) to thermionically emit electrons [3].

- Electron Beam: A stream of electrons accelerated perpendicularly to the sample beam through a potential difference of 70 eV [3].

- Ion Repeller: A positively charged electrode that pushes the newly formed ions out of the ionization chamber toward the mass analyzer [3].

- Focusing Magnets: Small magnets that generate a magnetic field perpendicular to the electron beam path, causing electrons to follow a helical trajectory through the ionization volume, thereby increasing the probability of electron-molecule collisions [3].

- Sample Introduction System: For vaporized samples, which can be introduced via direct probe for solid and liquid samples or from a gas chromatograph interface for mixture analysis [28].

The following diagram illustrates the key components and ionization mechanism of a typical EI source:

Figure 1: Electron Ionization Source Components and Mechanism

Comparative Analysis of Ionization Techniques

EI Versus Soft Ionization Methods

The fundamental distinction between Electron Ionization and soft ionization techniques lies in the amount of internal energy transferred to the analyte molecules during ionization, which directly impacts the degree of fragmentation observed in the mass spectrum. While EI generates extensive fragmentation, soft ionization methods such as Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) preserve the molecular ion with minimal fragmentation [1] [3]. This key difference dictates their respective applications in analytical chemistry.

ESI creates ions through a process of charged droplet formation, desolvation, and Coulombic explosion, typically producing multiply charged ions for large biomolecules and preserving molecular integrity [27] [3]. MALDI uses a matrix to absorb laser energy and transfer it to the analyte, causing desorption and ionization with minimal fragmentation, making it ideal for high molecular weight compounds [27] [1]. APCI employs corona discharge at atmospheric pressure to ionize molecules through gas-phase reactions, producing predominantly protonated molecules [M+H]+ with little fragmentation [27] [3].

The following table provides a detailed comparison of key ionization techniques, highlighting their characteristics and appropriate applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Common Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Ionization Technique | Ionization Type | Typical Ions Formed | Sample Requirements | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) | Hard | M⁺• (radical cation), extensive fragments | Volatile, thermally stable, low MW (<600 Da) | GC-MS, structural elucidation, unknown ID | Rich structural info, reproducible spectra | Excessive fragmentation, no molecular ion |

| Chemical Ionization (CI) | Soft | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻, few fragments | Volatile, thermally stable | GC-MS, molecular weight determination | Molecular ion preserved, less fragmentation | Limited structural information |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Very Soft | [M+nH]ⁿ⁺, [M-H]⁻ (multiply charged) | Polar, non-volatile, in solution | LC-MS, proteins, peptides, biomolecules | High MW compounds, multiple charging | Sensitive to salts and contaminants |

| MALDI | Soft | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ (singly charged) | Solid, mixed with matrix | Proteins, polymers, imaging | High MW, minimal fragmentation | Matrix interference, sample preparation |

| APCI | Soft | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ | Semi-volatile, thermally stable | LC-MS, medium polarity compounds | Handles higher flow rates than ESI | Thermal degradation possible |

Fragmentation Patterns and Information Content

The extensive fragmentation characteristic of Electron Ionization represents both its greatest strength and most significant limitation. The fragmentation pathways followed by molecular ions are governed by well-understood principles of physical organic chemistry, including the stability of resulting fragment ions and radical species, as well as the relative strengths of the chemical bonds being cleaved [3]. This predictable fragmentation allows experienced mass spectrometrists to "read" EI mass spectra and deduce structural information about the original molecule.

For example, alkanes typically fragment at branch points, producing characteristic fragment ions that reveal the carbon skeleton. Carboxylic acids often undergo Mc-Lafferty rearrangement, generating distinctive even-mass fragment ions. Aromatic compounds tend to produce stable tropylium ions and other cyclic cations [3]. This rich fragmentation pattern serves as a structural fingerprint, enabling both identification of unknown compounds through interpretation and library matching against extensive databases of reference EI spectra.

In contrast, soft ionization techniques like ESI and MALDI primarily yield information about the molecular weight of the analyte, with little or no structural information unless coupled with additional fragmentation techniques such as tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [1]. While EI provides both molecular weight (from the molecular ion, when present) and structural information in a single analysis, soft ionization typically requires multiple stages of mass analysis to obtain comparable structural data.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard EI-MS Analysis Procedure

The implementation of Electron Ionization mass spectrometry follows a systematic procedure to ensure reproducible results and optimal instrument performance. The standard protocol encompasses sample preparation, instrument calibration, data acquisition, and data interpretation steps:

Sample Preparation:

- For solid samples: Dissolve in appropriate volatile solvent (e.g., methanol, dichloromethane, hexane) to concentration of 0.1-1.0 mg/mL [29].

- For liquid samples: Dilute with volatile solvent if necessary to achieve appropriate concentration.

- For gaseous samples: Introduce directly via gas sampling valve or syringe.

- Ensure sample is free of non-volatile salts and buffers that may contaminate the ion source.

Sample Introduction:

- GC-MS Interface: For complex mixtures, connect to gas chromatograph with appropriate column and temperature program [29].

- Direct Insertion Probe: For pure compounds or simple mixtures, use direct probe with temperature ramp from ambient to 300-400°C at controlled rate.

- Reference Standard: Analyze known compound (e.g., perfluorotributylamine) for mass calibration and tuning.

Instrument Parameters:

- Electron Energy: Set to 70 eV (standard) or lower (10-20 eV) for reduced fragmentation [3].

- Emission Current: Typically 100-500 μA to ensure sufficient electron flux [3].

- Ion Source Temperature: Maintain at 200-300°C to prevent sample condensation [29].

- Mass Analyzer: Set appropriate mass range (typically m/z 40-600 for small molecules) and scan rate (e.g., 1-2 scans/second) [29].

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire mass spectra across entire chromatographic peak or probe temperature range.

- Use appropriate background subtraction to remove solvent and column bleed contributions.

- Collect multiple scans to ensure representative sampling.

Data Interpretation:

- Identify molecular ion (if present) as highest m/z value in spectrum (excluding isotope peaks).

- Analyze characteristic fragmentation patterns for functional group identification.

- Compare with library spectra (NIST, Wiley) for compound identification [3].

- Use isotope patterns for elemental composition information.

GC-EI/MS Method for Bioanalytical Applications

A specific example of EI methodology in practice is demonstrated by a recent study analyzing methylsiloxanes in human plasma using GC-EI/MS with high-resolution Orbitrap technology [29]. This application showcases the implementation of EI in a challenging bioanalytical context:

Table 2: Experimental Conditions for GC-EI/MS Analysis of Methylsiloxanes in Plasma [29]

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | 100 μL plasma + methanol protein precipitation, n-hexane extraction, vacuum concentration | Remove proteins, extract analytes, concentrate |

| GC Column | TG-5HT (5% diphenyl/95% dimethyl polysiloxane) | High-temperature stability for siloxane separation |

| Ionization Mode | Electron Ionization (EI) | Generate characteristic fragments for identification |

| Mass Analyzer | Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Accurate mass measurement for selectivity |

| Calibration | Internal Standard Method | Improve quantification accuracy |

| Linear Range | 1.56-50.00 μg/L | Cover expected physiological concentrations |

| LOD | 0.14-0.47 μg/L | Sensitive detection at trace levels |

This methodology yielded excellent performance characteristics with coefficients of determination (R²) greater than 0.995, spike recovery rates of 76.69%-122.65%, and relative standard deviations below 15%, demonstrating the robustness of EI for quantitative bioanalysis [29]. The application to 62 human plasma samples successfully detected four methylsiloxanes with concentrations ranging from

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials