Ion Suppression in ESI-MS: Fundamentals, Modern Correction Strategies, and Impact on Biomarker Research

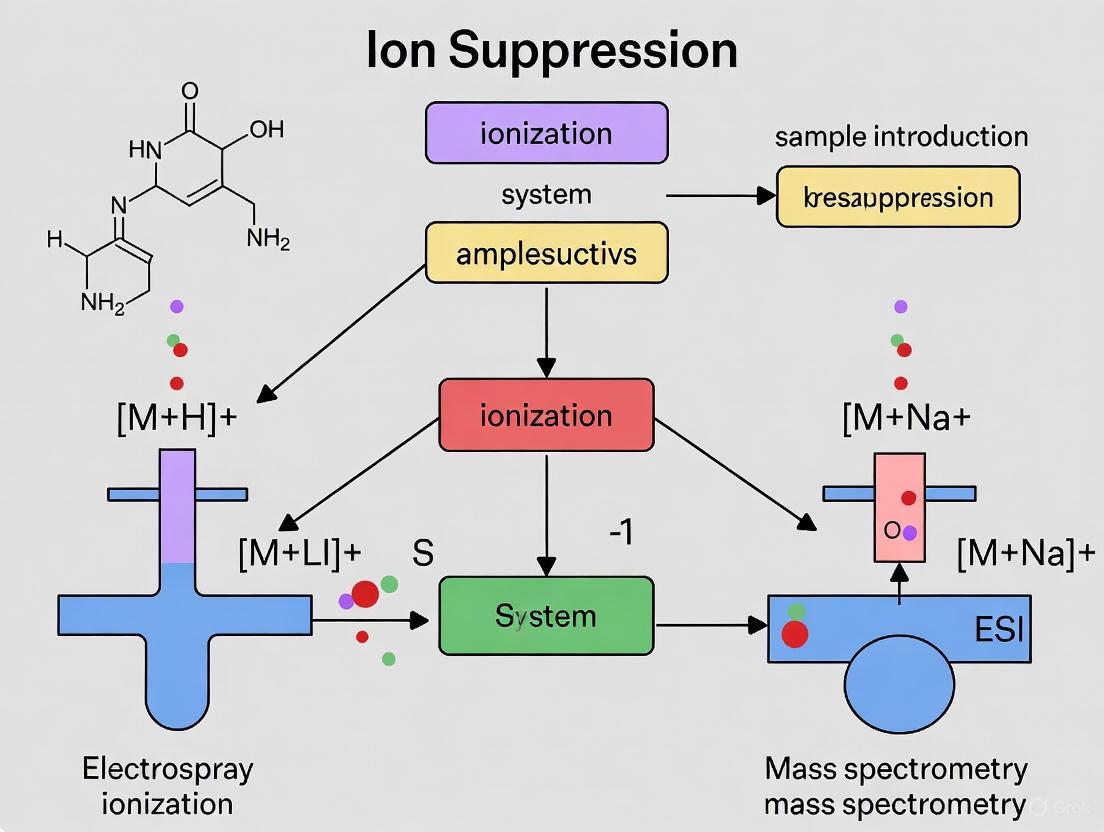

Ion suppression remains a critical challenge in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), dramatically impacting the accuracy, precision, and sensitivity of analyses in drug development and clinical research.

Ion Suppression in ESI-MS: Fundamentals, Modern Correction Strategies, and Impact on Biomarker Research

Abstract

Ion suppression remains a critical challenge in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), dramatically impacting the accuracy, precision, and sensitivity of analyses in drug development and clinical research. This article provides a comprehensive overview for scientists and researchers, covering the foundational mechanisms of ion suppression, from competition for charge to the effects of non-volatile solutes. It explores innovative methodological solutions like the IROA TruQuant workflow and stable isotope-assisted strategies for correction and normalization. The content also details practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques for the LC-MS system and sample preparation, and concludes with robust validation protocols to ensure data reliability. By synthesizing the latest 2025 research, this guide aims to empower professionals to overcome ion suppression and produce more reproducible and quantitatively accurate metabolomic data.

What is Ion Suppression? Unraveling the Core Mechanisms in ESI-MS

Ion suppression represents a significant challenge in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), particularly for electrospray ionization (ESI), where it manifests as a reduction in analyte signal due to the presence of co-eluting matrix components [1] [2]. This phenomenon adversely affects key analytical figures of merit including detection capability, precision, and accuracy, making it a critical concern for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with complex matrices [1] [3]. Despite the high selectivity of LC-MS and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS), these techniques remain susceptible to ion suppression effects, which can lead to false negatives, inaccurate quantification, and compromised data integrity [1] [2]. This technical guide explores the fundamental mechanisms, detection methodologies, and advanced strategies for mitigating ion suppression within the broader context of ESI research fundamentals.

Mechanisms and Origins of Ion Suppression

Ion suppression occurs in the early stages of the ionization process in the LC-MS interface when co-eluting compounds influence the ionization efficiency of target analytes [1]. The term was formally introduced by Buhrman and colleagues, who quantitatively defined it as (100 - B)/(A × 100), where A and B represent unsuppressed and suppressed signals, respectively [1]. The complexity of ion suppression stems from its diverse origins and mechanisms, which vary depending on the ionization technique employed.

Ion Suppression in Electrospray Ionization (ESI)

ESI exhibits particular susceptibility to ion suppression through multiple proposed mechanisms. The competitive ionization theory suggests that in multicomponent samples at high concentrations, compounds compete for limited charge or space on the surface of electrospray droplets [1]. Surface activity and basicity determine a compound's ability to outcompete others for these limited resources [1]. Biological matrices contain abundant endogenous compounds with high basicities and surface activities, quickly reaching concentration thresholds (approximately >10⁻⁵ M) where ion suppression becomes significant [1].

Alternative mechanisms propose that physical droplet properties contribute to suppression. High concentrations of interfering components can increase droplet viscosity and surface tension, reducing solvent evaporation rates and the efficiency of analyte transfer to the gas phase [1] [2]. Additionally, the presence of nonvolatile materials may cause co-precipitation of analyte or prevent droplets from reaching the critical radius required for gas-phase ion emission [1] [2] [4]. Gas-phase neutralization reactions, where analyte ions are deprotonated by compounds with high gas-phase basicity, provide another suppression pathway [1].

Ion Suppression in Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI)

APCI generally demonstrates less pronounced ion suppression compared to ESI, attributed to fundamental differences in their ionization mechanisms [1] [2]. Unlike ESI, APCI does not involve competition between analytes to enter the gas phase, as neutral analytes are vaporized in a heated gas stream [1]. Ion suppression in APCI has been linked to changes in colligative properties during evaporation and the effect of sample composition on charge transfer efficiency from the corona discharge needle [2]. Solid formation, either as pure analyte or coprecipitate with other nonvolatile components, represents another suppression mechanism in APCI [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Ion Suppression Mechanisms in ESI and APCI

| Factor | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Competition for charge & droplet space [1] | Change in colligative properties [2] |

| Phase of Suppression | Solution & droplet processes [1] [4] | Primarily solution phase [1] |

| Susceptibility | High [1] [2] | Moderate [1] [2] |

| Key Influencing Factors | Surface activity, basicity, concentration [1] | Volatility, gas-phase basicity [1] |

Detection and Evaluation Methods

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Guidance for Industry on Bioanalytical Method Validation explicitly requires assessment of matrix effects to ensure analytical quality [1] [3]. Two established experimental protocols enable researchers to validate the presence and characterize the impact of ion suppression.

Post-Column Infusion Assay

This comprehensive method enables visualization of ion suppression regions throughout the chromatographic run [1] [2]. The experimental workflow involves continuous infusion of a standard analyte solution post-column via a syringe pump while injecting a blank matrix extract [1]. The chromatographic profile reveals ion suppression as decreases in the constant baseline signal corresponding to the elution of matrix interferents [1]. Figure 1 illustrates this experimental setup and the resulting output, which maps suppression zones by retention time.

Figure 1: Workflow for Post-Column Infusion Ion Suppression Assay - This diagram illustrates the experimental setup where analyte is infused post-column while blank matrix is injected, enabling detection of ion suppression zones in the chromatogram.

Post-Extraction Spike Method

This alternative approach compares the detector response of analytes spiked into blank matrix extracts after preparation versus the response in pure solvent [1] [2] [3]. A significant reduction in signal from the matrix sample indicates ion suppression [1]. While this method effectively quantifies the extent of suppression, it does not provide chromatographic profiling of interfering regions [1]. This approach can be extended to compare signals from matrix extracts spiked before and after sample preparation to differentiate signal loss from recovery issues versus true ion suppression [2].

Quantitative Assessment of Ion Suppression

Recent advances in metabolomics research have provided comprehensive quantitative data on ion suppression across various analytical conditions. A 2025 study systematically evaluated ion suppression using the IROA TruQuant workflow across different chromatographic systems, ionization modes, and source conditions [5]. The results demonstrated that ion suppression affects virtually all analytes to varying degrees, with significant implications for method development and validation.

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Ion Suppression Across LC-MS Conditions

| Chromatographic System | Ionization Mode | Source Condition | Ion Suppression Range | Affected Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Chromatography (IC) | Negative | Clean | 1% to >90% [5] | 539 different metabolites detected [5] |

| Reversed-Phase (RPLC) | Positive | Clean | 8.3% (e.g., Phenylalanine) [5] | 422 metabolites/sample (average) [5] |

| HILIC | Positive | Unclean | Significantly greater [5] | 216 common across all samples [5] |

| All Systems | Both | Unclean | Up to nearly 100% [5] | Extensive suppression [5] |

The data reveal several critical patterns: negative ionization mode typically detects fewer ions but still experiences extensive suppression, unclean ionization sources demonstrate significantly greater suppression than cleaned sources, and ion suppression affects virtually all metabolites to varying degrees [5]. Specific examples include phenylalanine (M+H) exhibiting 8.3% suppression in RPLC positive mode with a cleaned source, while pyroglutamylglycine (M-H) showed up to 97% suppression in ICMS negative mode [5].

Advanced Strategies for Mitigation and Correction

Chromatographic and Sample Preparation Approaches

Effective management of ion suppression requires multifaceted strategies beginning with chromatographic optimization and sample clean-up. Modified chromatographic separation to prevent co-elution of suppressing species with target analytes represents the most straightforward approach [2]. When separation alone proves insufficient, comprehensive sample preparation techniques including solid-phase extraction (SPE), liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), and protein precipitation can remove interfering matrix components [2] [3] [6]. Research demonstrates that SPE provides superior selectivity for removing ion-suppressing compounds compared to less selective techniques like LLE or protein precipitation [6].

Innovative Chemical and Computational Workflows

Recent methodological advances offer promising approaches for correcting ion suppression effects, particularly in non-targeted analyses. The IROA TruQuant Workflow utilizes a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (IROA-IS) library with companion algorithms to measure and correct for ion suppression while performing Dual MSTUS normalization of MS metabolomic data [5]. This method identifies molecules based on unique, formula-specific isotopolog ladders, enabling precise suppression correction across diverse analytical conditions [5].

Chemical Isotope Labeling (CIL) LC-MS provides another innovative approach, where metabolites are chemically labeled with optimized reagents before LC-MS analysis to enhance detection sensitivity and improve quantification accuracy [7]. The recent development of a two-channel mixing strategy combines amine/phenol and hydroxyl submetabolomes after labeling but prior to LC-MS analysis, significantly improving throughput while maintaining metabolite coverage [7].

Anion-Exchange Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (AEC-MS) with electrolytic ion-suppression addresses long-standing challenges in analyzing highly polar and ionic metabolites that drive primary metabolic pathways [8]. This innovation links high-performance ion-exchange chromatography directly with mass spectrometry, improving molecular specificity and selectivity for metabolomic applications [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ion Suppression Management

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | Measures and corrects for ion suppression; enables normalization [5] | Contains clearly identifiable isotopolog patterns [5] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalizes response; compensates for variability [2] | Should be chemically matched to analyte [2] |

| Chemical Isotope Labeling Kits (e.g., DnsCl) | Enhances detection sensitivity & quantification accuracy [7] | Targets specific submetabolomes (amine/phenol, hydroxyl) [7] |

| Formic Acid (0.1%) | Common mobile phase additive for positive ion mode [9] [7] | Higher concentrations can cause ion pairing [6] |

| Triethylamine (TEA) | Mobile phase additive for negative ion mode | Use <0.1% v/v; high gas-phase proton affinity [6] |

Ion suppression remains a complex yet manageable phenomenon in LC-MS analysis that significantly impacts analytical performance in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Understanding its mechanisms through both ESI and APCI ionization pathways provides the foundation for effective mitigation. Comprehensive assessment using post-column infusion or post-extraction spike methods enables researchers to identify and characterize suppression effects during method validation. The quantitative data presented in this guide demonstrates the pervasive nature of ion suppression across analytical conditions while highlighting advanced correction methodologies including the IROA TruQuant workflow, chemical isotope labeling techniques, and novel chromatographic approaches such as AEC-MS. By implementing these sophisticated strategies and reagent solutions, researchers can effectively nullify suppression effects, thereby ensuring the precision, accuracy, and sensitivity essential for rigorous bioanalytical applications.

The Electrospray Ionization Process and Where Suppression Occurs

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that has become a cornerstone of modern mass spectrometry, particularly for the analysis of biologically relevant macromolecules and thermally labile compounds [10] [11]. Its capacity to transfer ions directly from a liquid solution into the gas phase without significant fragmentation has revolutionized fields such as proteomics, metabolomics, and pharmaceutical analysis [11]. The electrospray process generates multiply charged ions, effectively extending the mass range of mass analyzers to accommodate the kiloDalton to MegaDalton molecular weights typical of proteins and their associated polypeptide fragments [12]. Understanding the fundamental principles of the ESI process is crucial for comprehending how and where ion suppression occurs, a phenomenon that significantly impacts the sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses [3].

The Step-by-Step Electrospray Ionization Process

The transformation of analyte molecules from solution into gas-phase ions in ESI is a multi-stage process involving electrical energy, solvent evaporation, and droplet fission [10].

Nebulization and Charged Droplet Formation

The ESI process begins when a sample solution containing the analytes of interest is introduced through a fine metal capillary or needle (maintained at a high voltage typically between 2.5–6 kV) relative to a surrounding counter electrode [10] [11]. This strong electric field (typically 2-6 kV) charges the surface of the liquid emerging from the capillary tip, dispersing it into a fine aerosol of highly charged droplets with the same polarity as the capillary voltage [10] [13]. The application of a coaxial nebulizing gas (such as nitrogen) shears the eluted sample solution, enabling higher flow rates and stabilizing the spray formation [10] [14]. The physical properties of the solvent, particularly surface tension, play a critical role in this initial step, as lower surface tension solvents require lower onset voltages for stable electrospray formation [14].

Solvent Evaporation and Droplet Shrinking

The cloud of charged droplets travels toward the mass spectrometer inlet under atmospheric pressure, guided by potential and pressure gradients [10]. With the aid of an elevated ESI-source temperature and a concurrent stream of nitrogen drying gas, the charged droplets continuously decrease in size through solvent evaporation [10] [11]. As the solvent evaporates, the droplet radius decreases while the charge density on its surface increases significantly. This continuous reduction in droplet size without a corresponding loss of charge leads to a steady increase in the electrostatic repulsion forces between like charges within the droplet [13].

Ion Ejection via Coulombic Fission and Desolvation

When the charged droplet reaches its Rayleigh limit, the point at which electrostatic repulsion forces equal the surface tension holding the droplet together, it becomes unstable and undergoes Coulombic fission [13] [12]. At this critical point, the droplet deforms and "explodes," ejecting smaller, progeny droplets while typically losing 1.0–2.3% of its mass and 10–18% of its charge [12]. These smaller droplets continue the process of solvent evaporation and repeated Coulombic fissions until ultimately leading to the formation of completely desolvated gas-phase ions [10].

Two primary models explain the final production of gas-phase ions:

- Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): This model suggests that as the droplet radius becomes sufficiently small (typically < 10 nm), the electric field strength at the droplet surface becomes intense enough to directly field-desorb solvated ions into the gas phase [12]. The IEM is generally considered the dominant mechanism for smaller ions.

- Charge Residue Model (CRM): This model proposes that electrospray droplets undergo successive evaporation and fission cycles until they form progeny droplets containing on average one analyte ion or less. Gas-phase ions form after the remaining solvent molecules evaporate, leaving the analyte with the charges that the droplet carried [12]. The CRM is thought to be the predominant mechanism for large macromolecules such as folded proteins.

The entire ESI process is visualized in the following workflow:

The Phenomenon of Ion Suppression in ESI

Definition and Fundamental Causes

Ion suppression refers to the reduction in ionization efficiency of a target analyte due to the presence of co-eluting substances in the mass spectrometer ion source [3] [1]. This matrix effect occurs when interfering components affect the ability of the analyte to become effectively ionized, subsequently leading to diminished signal intensity and potentially compromising quantitative accuracy [3]. The term was quantitatively defined by Buhrman and colleagues as (100 - B)/(A × 100), where A and B represent the unsuppressed and suppressed signals, respectively [1].

The origins of ion suppression are multifaceted, primarily occurring during the early stages of the ionization process within the LC-MS interface [1]. Both endogenous compounds from the sample matrix and exogenous substances introduced during sample preparation can contribute to this phenomenon [3]. The fundamental causes include:

- Competition for Charge: In ESI, the number of excess charges available on droplets is limited. At high concentrations (>10⁻⁵ M), the approximate linearity of the ESI response is often lost as analytes compete for limited charge. Compounds with higher surface activity or gas-phase basicity can out-compete the target analyte for this limited charge, leading to suppressed ionization of less competitive species [1].

- Altered Solution Properties: Co-eluting matrix components can increase the viscosity and surface tension of the ESI droplets, thereby reducing the efficiency of solvent evaporation and the subsequent release of gas-phase analyte ions [1].

- Nonvolatile Material Interference: The presence of nonvolatile materials (e.g., salts, phospholipids, proteins) can coprecipitate with the analyte or prevent droplets from reaching the critical radius required for gas-phase ion emission [1].

- Gas-Phase Proton Transfer: Even after ions are formed in the gas phase, analyte ions can be neutralized via deprotonation reactions with substances possessing higher gas-phase basicity [1].

Location of Ion Suppression in the ESI Process

Ion suppression predominantly occurs at specific stages of the electrospray process, primarily within the ion source before mass analysis begins. The following diagram illustrates the critical points where suppression manifests:

The three primary suppression zones are:

- Suppression Zone 1 (Competition for Limited Surface Charges): During initial droplet formation and subsequent Coulomb fissions, analytes compete for limited surface charges. More surface-active compounds will preferentially occupy droplet surfaces, excluding less competitive analytes and preventing their efficient release as gas-phase ions [1].

- Suppression Zone 2 (Altered Droplet Properties): Matrix components can increase the viscosity and surface tension of ESI droplets, hindering solvent evaporation and delaying the achievement of the critical droplet radius necessary for ion release [1].

- Suppression Zone 3 (Gas-Phase Proton Transfer): After ion formation, gas-phase reactions can occur where protonated analyte ions transfer their protons to matrix components with higher gas-phase basicity, effectively neutralizing the analyte ions before detection [1].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Ion Suppression

Post-Extraction Spike-In Method

This quantitative approach evaluates the extent of ion suppression by comparing analyte response in a clean matrix to response in the presence of matrix components [3] [1].

Protocol:

- Prepare a calibration standard in pure mobile phase or solvent (Solution A).

- Process a blank biological matrix (e.g., plasma, urine) through the entire sample preparation procedure.

- Spike the analyte of interest into the prepared blank matrix extract at a concentration identical to Solution A (Solution B).

- Inject and analyze both solutions using the developed LC-MS method.

- Calculate the matrix effect (ME) using the formula: ME (%) = (Peak Area of Solution B / Peak Area of Solution A) × 100 A value of 100% indicates no matrix effects, values <100% indicate suppression, and values >100% indicate ionization enhancement [3].

Continuous Post-Column Infusion Method

This qualitative method identifies the chromatographic regions affected by ion suppression, providing a temporal profile of matrix effects [3] [1].

Protocol:

- Prepare a solution of the analyte of interest at a suitable concentration.

- Connect a syringe pump or secondary LC pump to introduce this solution via a T-connector into the column effluent flowing to the MS, establishing a constant baseline signal.

- Inject a blank matrix extract processed through the sample preparation protocol.

- Monitor the analyte signal throughout the chromatographic run.

- Observe and record regions where the constant baseline signal decreases, indicating the elution of matrix components that cause ion suppression [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Ion Suppression Evaluation Methods

| Method Characteristic | Post-Extraction Spike-In | Continuous Post-Column Infusion |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Quantitative extent of suppression | Chromatographic location of suppression |

| Throughput | Medium (multiple preparations needed) | Low (single injection per matrix) |

| Sample Consumption | Higher | Lower |

| Ease of Interpretation | Straightforward numerical result | Requires interpretation of signal dips |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Widely accepted in validated methods | Used primarily in method development |

Critical Factors and Solutions for Ion Suppression

Factors Contributing to Ion Suppression

Several analytical and matrix-related factors influence the degree of ion suppression observed in ESI-MS analyses:

- Sample Matrix Complexity: Biological fluids such as plasma, urine, and tissue homogenates contain numerous endogenous compounds (e.g., phospholipids, bile salts, organic acids) that are prime candidates for causing ion suppression, particularly when they elute in the same retention window as the analyte [3] [1].

- Sample Preparation Minimalism: Approaches that use minimal sample clean-up (e.g., protein precipitation only) retain more matrix components, increasing the potential for ion suppression compared to more selective techniques like solid-phase extraction or liquid-liquid extraction [3].

- Chromatographic Separation: Short, non-resolving chromatographic methods that fail to separate analytes from matrix components significantly increase the risk of co-elution and subsequent ion suppression [3].

- Mobile Phase Composition: The use of ion-pairing agents and non-volatile buffers can exacerbate ion suppression effects [3].

Strategies for Overcoming Ion Suppression

Multiple strategies exist to mitigate the effects of ion suppression, which can be implemented individually or in combination:

- Enhanced Sample Cleanup: Implement more selective sample preparation techniques such as solid-phase extraction (SPE), liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), or phospholipid removal plates to specifically remove classes of compounds known to cause suppression [3].

- Chromatographic Optimization: Extend chromatographic run times, modify gradient profiles, or employ alternative stationary phases to achieve better separation of analytes from suppressing matrix components [3].

- Modified Ionization Techniques: Switch from ESI to atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) or atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI), which are generally less susceptible to ion suppression because the ionization mechanism occurs predominantly in the gas phase rather than in the liquid droplet [1].

- Effective Internal Standardization: Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) that co-elute with the analyte and experience identical suppression effects, thereby compensating for these effects during quantification [3].

- Lower Sample Injection Volumes: Reduce the absolute amount of matrix introduced into the system, thereby decreasing the concentration of suppressing components [3].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for ESI-MS and Ion Suppression Management

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Suppression Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Buffers | Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate, acetic acid, formic acid | Provide pH control and protons for ionization without residue accumulation | Non-volatile phosphate buffers cause severe suppression |

| SPE Sorbents | C18, mixed-mode, hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), phospholipid removal | Selective extraction of analytes and removal of matrix components | Proper sorbent selection critical for removing specific suppressors |

| Organic Solvents | LC-MS grade methanol, acetonitrile, isopropanol | Mobile phase components with low surface tension for stable spray formation | Low-grade solvents may contain impurities that cause suppression |

| Ion-Pairing Agents | Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) | Improve chromatographic separation of ionic compounds | Can cause significant ion suppression; use at minimal concentrations |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Deuterated, ¹³C, ¹⁵N-labeled versions of analytes | Internal standards that compensate for suppression via identical behavior | Must be chromatographically inseparable from analyte for effective compensation |

The electrospray ionization process represents a sophisticated yet vulnerable interface between liquid separation techniques and mass spectrometric detection. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying both ESI and the ion suppression that can occur at multiple points within this process is fundamental to developing robust, sensitive, and accurate LC-MS methods. The physical processes of charged droplet formation, solvent evaporation, Coulombic fission, and final ion release each present opportunities for competitive processes that may suppress analyte ionization. Through systematic evaluation using established experimental protocols and implementation of appropriate mitigation strategies—including enhanced sample preparation, chromatographic optimization, and effective internal standardization—the detrimental effects of ion suppression can be significantly reduced or eliminated. As ESI-MS continues to be a pivotal technology in drug development, proteomics, and metabolomics, mastery of ion suppression fundamentals remains an essential competency for researchers and scientists seeking to generate reliable analytical data.

Ion suppression represents a fundamental challenge in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), directly impacting the accuracy and sensitivity of analyses across pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and basic research. This phenomenon occurs when the ionization efficiency of an analyte is reduced by the presence of competing species in the ESI process. Within the context of a broader thesis on ESI fundamentals, this whitepaper examines the core mechanistic theories underpinning ion suppression, focusing specifically on the competition for limited charge and droplet surface area. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing effective strategies to mitigate suppression effects, thereby improving data quality and analytical reliability in drug development workflows.

Theoretical Foundations of Ion Suppression

The observed reduction in analyte signal during ESI-MS analysis stems from physical and chemical competitions occurring within the evolving electrospray droplet. Two primary, interconnected mechanistic theories explain this phenomenon: competition for limited available charge and competition for limited droplet surface area.

Competition for Charge

This theory posits that the number of excess charges (ions) available in a droplet is finite. During the droplet fission and solvent evaporation processes that characterize ESI, these charges are ultimately transferred to gas-phase ions. Co-present chemical species, including the analyte of interest, matrix components, and solvents, compete for this limited charge pool.

- Gas-Phase Ion-Molecule Reactions: In Secondary Electrospray Ionization (SESI), ion suppression is dominated by gas-phase processes. Studies have demonstrated that compounds with high gas-phase basicity, such as pyridine, can exert a significant suppressive effect on the ionization of other analytes. This occurs through mechanisms like proton transfer, where the suppressing agent effectively "scavenges" available protons, thereby reducing the protonation of target analytes [9].

- Charge Depletion by Non-Volatile Salts: The presence of non-volatile salts (e.g., NaCl) at physiologically relevant concentrations can severely suppress the signal of biological ions. This is attributed to the removal of excess droplet charge via the ion evaporation mechanism, where salt ions compete with and surpass analyte molecules for the limited charges available during droplet fission [15].

Competition for Droplet Surface Area

The electrospray process generates microdroplets with a high surface-to-volume ratio. A strong intrinsic electric field exists at the air/water interface of these droplets, making the surface a critical region for ionization and chemical reactions [16]. The surface area available for analyte presentation is finite, leading to competitive effects.

- Interfacial Phenomenon: Reaction acceleration and ionization in microdroplets are established as interfacial phenomena. The strong interfacial electric field facilitates unique chemistry, but the limited spatial area means that analytes and matrix components must compete for a position at this reactive interface [16].

- Surface Activity and Partitioning: The propensity of a molecule to occupy the droplet surface depends on its surface activity. More surface-active species will preferentially partition to the droplet interface, gaining preferential access to the strong electric field and charge carriers, thereby excluding less surface-active analytes and suppressing their ionization.

Quantitative Evidence and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes key experimental findings that quantify the impacts of these competitive processes.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Ion Suppression Mechanisms

| Suppressing Agent / Condition | Experimental System | Observed Effect | Postulated Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyridine [9] | Secondary Electrospray Ionization (SESI) | Significant suppressive effect on other analytes | Competition for Charge (High gas-phase basicity) |

| Acetone (at 1 ppm) [9] | SESI with Humid Conditions | ~30% intensity decrease for several breath analytes | Competition for Charge (Gas-phase processes) |

| Non-volatile Salts (e.g., NaCl) [15] | Native ESI-MS of Proteins | Signal suppression up to ~1950x; peak broadening & mass shift | Competition for Charge & Charged-Residue Mechanism |

| Concentrated Sample Matrix [5] | Non-targeted Metabolomics (various LC-MS systems) | Ion suppression ranging from 1% to >90% for detected metabolites | Competition for Charge and Droplet Surface Area |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To provide context for the data, key methodologies from cited studies are outlined below.

Protocol for Investigating Gas-Phase Ion Suppression in SESI

This protocol is adapted from studies characterizing ion suppression in Secondary Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (SESI-MS) [9].

- Objective: To assess the susceptibility and suppression potential of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like acetone and pyridine in a gas-phase ionization system.

- Gas Standard Generation: Gaseous analytes are generated using an evaporation-based system. A dilution gas (flow rate of 8 L min⁻¹) is passed through a bubbler to achieve either dry (0%) or humid (95%) conditions. The system is maintained at 60°C to prevent condensation.

- SESI-MS Analysis: A SESI ion source is coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap). The electrolyte (e.g., 0.1% formic acid) is electrosprayed using a nanoelectrospray capillary. The ionization chamber is typically held at 90°C, and the sampling inlet at 130°C.

- Crossover Experiment: To isolate suppression effects, the concentration of one compound (e.g., acetone) is systematically increased in half-logarithmic steps (covering a 1000x concentration range), while the concentration of a competing compound (e.g., deuterated acetone, D6-acetone) is held constant. The signals of both compounds are monitored via selected ion monitoring.

- Data Analysis: Ion suppression is quantified by the reduction in signal intensity of the constant-concentration analyte as the concentration of the competing analyte is increased.

Protocol for Analyzing Proteins from High-Salt Solutions using Theta Emitters

This protocol describes a method to mitigate ion suppression for proteins in physiologically relevant buffers [15].

- Objective: To enable mass analysis of proteins and protein complexes directly from solutions containing biological buffers and non-volatile salts.

- Emitter Preparation: Theta emitters are produced from borosilicate glass capillaries using a micropipette puller to create a tip with an inner diameter of ~1.4 μm. The emitter features a septum dividing the capillary into two independent channels.

- Sample Loading: The protein sample, dissolved in a biological buffer (e.g., PBS), is loaded into one channel of the theta emitter. A solution of 200 mM ammonium acetate, potentially supplemented with an additive like sodium iodide or bromide, is loaded into the second channel.

- nESI-MS Operation: Dual platinum wires are inserted into the open ends of the theta emitter, with each wire contacting one solution. A voltage of 0.8–2.0 kV is applied to generate the electrospray. The emitter is positioned 1–2 mm from the MS orifice.

- Gas-Phase Activation: Two sequential collisional heating methods are employed to remove salt adducts:

- Beam-type Collision-Induced Dissociation (BTCID): Ions are accelerated into a collision cell filled with N₂ bath gas (6–10 mTorr).

- Dipolar Direct Current (DDC) Offset: An offset potential is applied in a linear ion trap to displace ions into regions of higher RF field strength, increasing collisional heating.

- Data Acquisition: Mass spectra are acquired and processed using appropriate software. Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios and spectral quality are compared against controls without biological buffers.

Visualizing the Ion Suppression Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and mechanistic pathways governing ion suppression in ESI.

Diagram 1: Core Ion Suppression Pathways. This diagram outlines the two primary competitive mechanisms leading to ion suppression in ESI.

Diagram 2: Theta Emitter Workflow for Salt Mitigation. This workflow shows how specialized emitters and gas-phase activation enable analysis of samples in high-salt buffers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments to study and mitigate ion suppression.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ion Suppression Studies

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Theta Emitters [15] | Glass emitters with a septum dividing the capillary into two channels; enable analysis of samples in high-salt buffers via incomplete mixing at the tip. | Loading sample in one channel and ammonium acetate/additive in the other to create salt-depleted droplets for native protein MS. |

| Anions with Low Proton Affinity (I⁻, Br⁻) [15] | Added to the ESI solution to compete with sodium adduction; facilitates the removal of Na⁺ from protein ions, reducing chemical noise and adduct formation. | Supplementing ammonium acetate in the theta emitter to improve S/N ratios for proteins in biological buffers. |

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) [5] | A stable isotope-labeled standard library used to directly measure and computationally correct for ion suppression in non-targeted metabolomics. | Spiked into samples at a constant concentration to quantify and correct for metabolite-specific ion suppression across different LC-MS systems. |

| Formic Acid (0.1% v/v) [9] | A common volatile electrolyte added to the ESI solvent to promote protonation and stable electrospray formation in positive ion mode. | Used as the sprayed electrolyte solution in SESI experiments to ionize gas-phase analytes. |

| Deuterated Volatiles (e.g., D6-Acetone) [9] | Used as internal tracers in crossover experiments; their identical chemistry but distinct mass allows precise tracking of suppression effects. | Holding D6-acetone concentration constant while increasing non-deuterated acetone to study gas-phase suppression without thermodynamic variables. |

The Impact of Non-Volatile Solutes on Droplet Formation and Evaporation

In electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry, the presence of non-volatile solutes represents a significant challenge, directly influencing the fundamental processes of droplet formation and evaporation, and leading to the pervasive issue of ion suppression. This phenomenon adversely affects key analytical figures of merit, including detection capability, precision, and accuracy [3] [1]. Non-volatile salts, such as sodium chloride, and biological buffer components are ubiquitous in the analysis of real-world samples, especially in pharmaceutical and biological applications. Their interference stems from their ability to modify the physical properties of the electrospray solution and compete for available charge during the ionization process [15] [17]. Understanding the impact of these solutes is not merely an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for developing robust and sensitive analytical methods in ESI-based research and drug development. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core mechanisms, experimental strategies, and practical methodologies for mitigating the detrimental effects of non-volatile solutes, framed within the critical context of ion suppression.

Core Mechanisms: How Non-Volatile Solutes Interface with the ESI Process

The journey of an analyte from a solution to a gas-phase ion in ESI is a multi-stage process, and non-volatile solutes can disrupt it at several points. The primary mechanism of ion formation for large biomolecules, the Charged-Residue Mechanism (CRM), is particularly susceptible [15]. In CRM, solvent evaporation from a charged droplet continues until the droplet's surface charge density is sufficient to overcome its surface tension, leading to Coulombic fission or complete solvent evaporation and leaving behind a gas-phase analyte ion. The presence of non-volatile solutes complicates this process through several interconnected pathways.

Physical and Chemical Interference Pathways

- Altered Solution Properties: Non-volatile solutes can increase the viscosity and surface tension of the solution. This reduces the efficiency of droplet formation and subsequent solvent evaporation, thereby inhibiting the liberation of gas-phase analyte ions [1].

- Salt Adduction and Condensation: Via the CRM, non-volatile salts can condense onto analyte molecules during the final stages of droplet evaporation. This leads to peak broadening, shifting of signals to higher mass-to-charge ratios, and complicating mass spectral interpretation [15].

- Competition for Charge: In the electrospray plume, there is a finite amount of excess charge available. Highly concentrated non-volatile species and matrix components compete with the analyte for this charge, often suppressing the ionization of the target analyte [1]. This competition can occur both in the condensed phase within the droplet and in the gas phase.

- Elevated Boiling Point: The presence of high concentrations of non-volatile material can raise the boiling point of the solution, leading to lower efficiency in solvent evaporation and the formation of fewer gas-phase ions [17].

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of how non-volatile solutes impact droplet formation and evaporation, ultimately leading to ion suppression.

Quantitative Data: Experimental Findings on Solute-Induced Effects

The theoretical mechanisms are supported by concrete experimental data quantifying the impact of non-volatile solutes. The following table summarizes key findings from recent investigations, highlighting the effects on signal quality and the efficacy of various mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Non-Volatile Solutes and Mitigation Efficacy

| Analyte / System | Non-Volatile Solute Conditions | Observed Impact | Mitigation Strategy | Result after Mitigation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins & Protein Complexes | Biological buffers, physiologically relevant salts | Signal suppression up to ~1950x lower than control; peak broadening | Theta emitters with anions of low proton affinity (Br⁻, I⁻) | Significant increase in S/N ratio; improved reproducibility & robustness | [15] |

| General ESI Mechanism | Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Loss of linearity in total ion current above ~10⁻⁵ M concentration | Not specified in study | (Fundamental mechanistic observation) | [1] |

| Metabolites (Phenylalanine) | Complex biological matrix (plasma) | 8.3% ion suppression (in RPLC-positive mode, clean source) | IROA TruQuant Workflow (isotope standards) | Restoration of linear signal increase with sample input | [5] |

| Metabolites (Pyroglutamylglycine) | Complex biological matrix (plasma) | Up to >97% ion suppression (in ICMS-negative mode) | IROA TruQuant Workflow (isotope standards) | Effective correction of extreme suppression | [5] |

| Biogenic Amines in Cheese | Complex food matrix | Severe signal suppression for all analytes | Switch from ESI to APCI source; HILIC chromatography | Signal enhancement observed (100–1000 fold) | [17] |

The data confirms that ion suppression can range from mild to nearly complete, severely compromising detection. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the degree of suppression is highly context-dependent, varying with the analyte, matrix, and chromatographic-MS conditions [17] [5].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

To overcome the challenges posed by non-volatile solutes, several advanced experimental strategies have been developed. These methodologies focus on either modifying the electrospray process itself or applying post-ionization techniques to remove adducts.

Theta Emitters with Anion Additives

This approach uses specialized theta emitters—glass capillaries with an internal septum dividing them into two channels [15].

- Protocol:

- Sample Loading: The protein or protein complex sample, dissolved in a biological buffer containing non-volatile salts (e.g., PBS), is loaded into one channel of the theta emitter.

- Additive Loading: The other channel is loaded with a solution of 200 mM ammonium acetate supplemented with an additive salt containing an anion of low proton affinity, such as sodium bromide (NaBr) or sodium iodide (NaI) [15].

- ESI-MS Analysis: A voltage is applied via dual platinum wires. The solutions mix at the emitter tip, promoting the formation of a population of droplets relatively depleted of non-volatile salts. The low-proton-affinity anions (Br⁻, I⁻) facilitate the removal of sodium ions over protons, reducing chemical noise and ionization suppression.

- Gas-Phase Activation: Transmitted ions are subjected to two stages of collisional activation: beam-type collision-induced dissociation (BTCID) and dipolar direct current (DDC) excitation in a linear ion trap. This removes residual solvent and salt adducts without causing significant dissociation of the biomolecular complex [15].

Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN)

The SPIN interface addresses ion transmission losses, a major bottleneck in sensitivity.

- Protocol:

- Emitter Placement: The nanoelectrospray emitter is placed inside the first vacuum stage of the mass spectrometer (~20 Torr), eliminating the conventional atmospheric-pressure inlet capillary [18].

- Desolvation: A flow of heated CO₂ gas (~160°C) is directed at the electrospray plume to achieve efficient droplet desolvation.

- Ion Funneling: The resulting gas-phase ions are immediately captured and focused by an electrodynamic ion funnel, which operates at high efficiency in this pressure regime.

- Efficiency Measurement: The ion utilization efficiency is evaluated by measuring the total transmitted gas phase ion current through the interface and correlating it with the observed analyte ion intensity in the mass spectrum [18]. This configuration has been shown to exhibit greater overall ion utilization efficiency than conventional ESI-MS interfaces.

The workflow for the theta emitter method, which integrates both sample introduction and gas-phase processing, is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field requires a specific set of tools and reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions in managing non-volatile solute effects.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Theta Emitters | Sample introduction for problematic matrices | Dual-channel glass capillary (~1.4 µm i.d.) enabling rapid mixing of sample and additive streams at the ESI tip [15]. |

| Ammonium Acetate (AmAc) | A volatile MS-compatible salt | Used to replace or supplement non-volatile biological buffers (e.g., PBS) during electrospray [15]. |

| Anions of Low Proton Affinity (Br⁻, I⁻) | Solution additive to reduce ionization suppression | Competes effectively with Na⁺, mitigating condensation and chemical noise; proton affinity: I⁻ < Br⁻ < Acetate [15]. |

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | Isotopic standard for ion suppression correction in metabolomics | A stable isotope-labeled (¹³C) library of metabolites used to measure and computationally correct for ion suppression in each sample [5]. |

| Ion Funnels | ESI-MS interface component | Electrodynamic device that focuses and transmits ions with high efficiency through regions of elevated pressure, increasing sensitivity [18]. |

| Collision Gas (N₂) | Gas-phase activation | Inert bath gas used in collision cells (q2) and traps for collisional excitation to remove solvent and salt adducts from ions [15]. |

The interference of non-volatile solutes with droplet formation and evaporation is a central pillar of the ion suppression problem in ESI research. The consequences—ranging from total signal loss to degraded data quality—are too significant to ignore in quantitative and trace analysis. As demonstrated, the underlying mechanisms are multifaceted, involving physical chemistry of solutions, competition phenomena, and ion transmission physics. Fortunately, the field has moved beyond simple desalting and now offers sophisticated strategies. The use of specialized emitter geometries like theta tips, strategic solution additives, advanced interface designs such as SPIN, and innovative data correction workflows like IROA provide researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful arsenal to combat these effects. Embracing these methodologies is essential for achieving the high levels of sensitivity, robustness, and reproducibility required in modern mass spectrometry.

How Physicochemical Properties of Analytes Influence Suppression Susceptibility

Ion suppression represents a major challenge in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), particularly when using electrospray ionization (ESI). This phenomenon manifests as a reduction in detector response for target analytes due to the presence of co-eluting compounds that interfere with the ionization process [2] [1]. In complex biological matrices, numerous endogenous and exogenous compounds compete for available charge and access to the droplet surface, ultimately affecting analytical accuracy, precision, and sensitivity [19] [20]. The susceptibility of an analyte to ion suppression is not random; rather, it is profoundly influenced by specific physicochemical properties that determine how the molecule behaves during the critical ionization process. Understanding these property-suppression relationships is fundamental for developing robust analytical methods, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug development where quantitative accuracy is paramount.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Ion Suppression

The ionization process in ESI involves multiple stages where competition between analytes can occur. The prevailing mechanisms point to both solution-phase and gas-phase processes that contribute to signal suppression.

Solution-Phase Competition

In the electrospray process, charged droplets are formed at the capillary tip. As solvent evaporation occurs, the droplet shrinks until it reaches the Rayleigh limit, leading to Coulomb fission and the production of smaller droplets [21]. During these processes, analytes compete for limited charge and for access to the droplet surface, which is crucial for transfer into the gas phase [1]. Compounds with higher surface activity or basicity can dominate this competition, effectively suppressing the ionization of less competitive analytes [2] [1]. The presence of nonvolatile compounds can further exacerbate suppression by increasing droplet viscosity and surface tension, or by causing co-precipitation of analytes, thereby preventing efficient ion formation [1] [4].

Gas-Phase Processes

While early research suggested solution-phase processes were dominant [4], recent studies indicate gas-phase reactions also contribute significantly to ion suppression, particularly in secondary electrospray ionization (SESI) [9]. In the gas phase, charge can be transferred between species based on their relative gas-phase basicities or acidities. A compound with higher gas-phase basicity can effectively protonate from another ion, leading to suppression of the less basic compound's signal [9]. This mechanism is particularly relevant for online analysis techniques where chromatographic separation is absent.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential processes in electrospray ionization where competition between analytes leads to ion suppression:

Physicochemical Properties Governing Suppression Susceptibility

Extensive research has identified several key physicochemical properties that significantly influence an analyte's susceptibility to ion suppression. These properties determine how efficiently a compound competes for charge and accesses the droplet surface during the ionization process.

Molecular Size and Surface Activity

Molecular volume and surface activity are among the most critical factors affecting ionization efficiency. Larger molecules with greater molecular volumes generally exhibit higher ESI responses, as demonstrated in a systematic study of acylated amino acids [21]. The correlation between molecular volume and ESI response was found to be stronger than with hydrophobicity (log P) or pKa [21]. Surface-active compounds preferentially migrate to the droplet surface, where they have better access to charge transfer and evaporation processes. These compounds will typically suppress less surface-active analytes by monopolizing the limited droplet surface area [1].

Polarity and Hydrophobicity

Hydrophobicity, commonly measured as log P, influences an analyte's positioning within the electrospray droplet and its ability to reach the gas phase. More hydrophobic compounds often demonstrate greater surface activity, allowing them to concentrate at the droplet-air interface and more efficiently undergo desolvation and ion emission [21]. However, extremely hydrophobic compounds may face challenges in the initial charging process. The relationship between hydrophobicity and ionization efficiency is complex and not always linear, with other factors like functional groups playing significant roles [21].

Basicity and Gas-Phase Proton Affinity

Solution basicity (pKa) and gas-phase proton affinity are crucial determinants in ionization competition. Compounds with higher gas-phase basicity can effectively strip protons from other ions in gas-phase charge transfer reactions, leading to suppression of less basic compounds [9]. For example, pyridine exhibits a significant suppressive effect on other analytes, which researchers have linked to its high gas-phase basicity [9]. In the solution phase, compounds with favorable pKa values for protonation (in positive ion mode) or deprotonation (in negative ion mode) under the LC-MS conditions will ionize more efficiently.

Concentration Effects

The relative concentration of an analyte compared to potential suppressors dramatically impacts the degree of suppression experienced. An analyte present at high concentration relative to matrix components is less susceptible to suppression, as it can effectively compete for available charge [2] [1]. However, at high concentrations (>10⁻⁵ M), ESI response linearity is often lost due to saturation effects at the droplet surface [1]. This creates a complex relationship where both absolute concentration and relative abundance compared to matrix components influence suppression susceptibility.

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties Affecting Ion Suppression Susceptibility

| Property | Mechanism of Influence | Impact on Suppression Susceptibility | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size/Volume | Affects mobility to droplet surface and evaporation efficiency | Larger molecules generally less susceptible | Strong correlation between molecular volume and ESI response [21] |

| Surface Activity | Determines positioning at droplet-air interface | High surface activity decreases susceptibility | Surface-active compounds dominate droplet surface [1] |

| Hydrophobicity (log P) | Influences partitioning to droplet surface | Moderate to high log P decreases susceptibility | Systematic study of acylated amino acids [21] |

| Basicity (pKa) | Affects protonation/deprotonation efficiency | Optimal pKa for ionization conditions decreases susceptibility | More basic compounds suppress others in gas phase [9] |

| Gas-Phase Basicity | Determines success in gas-phase charge transfer | High gas-phase basicity decreases susceptibility | Pyridine shows strong suppressive effect [9] |

| Relative Concentration | Impacts competition for limited charge | High concentration relative to matrix decreases susceptibility | Analytic/matrix ratio affects suppression degree [2] |

Quantitative Assessment of Property-Suppression Relationships

Rigorous experimental studies have quantified the relationship between specific physicochemical properties and ionization suppression, enabling more predictive approaches to method development.

Systematic Studies on Molecular Properties

A comprehensive investigation employing amino acids and their derivatives revealed clear trends in ionization efficiency relative to molecular properties [21]. Researchers acylated 14 amino acids with organic acid anhydrides of increasing chain length and with poly(ethylene glycol), systematically altering physicochemical properties. When comparing the ESI response of 70 derivatives, they found the strongest correlation between calculated molecular volume and ESI response (R² > 0.9 for a test set of 43 compounds) [21]. Correlation with hydrophobicity (log P values) was significant but lower, while pKa showed variable influence depending on the specific compound series.

Gas-Phase Suppression Studies

Recent research on secondary electrospray ionization (SESI) has quantified gas-phase suppression effects, demonstrating that acetone at concentrations of 1 ppm can cause approximately 30% signal reduction for numerous features in humid conditions [9]. Crossover experiments with deuterated compounds revealed that suppression intensity depends strongly on the gas-phase basicity of the interfering compound, with pyridine exhibiting the most significant suppressive effect among tested compounds [9].

Chromaticgraphic Influences on Property-Effects Relationships

The chromatographic system employed significantly modulates how physicochemical properties affect suppression susceptibility. Studies comparing reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), and ion chromatography (IC) systems demonstrate that the same analyte may experience different degrees of suppression depending on the separation mechanism [22]. For example, phospholipids—known suppressors in RPLC—elute differently in supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC), changing their suppressive impact on co-eluting analytes [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Physicochemical Properties on Ion Suppression

| Property Modification | Experimental System | Impact on ESI Response | Suppression Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acylation of amino acids | RPLC-MS, positive mode | Up to 10-fold increase with PEGylation | Significant reduction in susceptibility [21] |

| Increasing chain length | Amino acid derivatives | Progressive improvement with molecular volume | Gradual reduction in susceptibility [21] |

| Gas-phase basicity increase | SESI-MS with pyridine | 30% suppression of other features at 1 ppm | High suppressive effect on others [9] |

| Phospholipid removal | TAG analysis in krill oil | 5-10 fold improvement in TAG signals | Near elimination of phospholipid suppression [23] |

| IROA normalization | Multi-chromatography system | Correction of 1% to >90% ion suppression | Effective nullification of suppression [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Property-Suppression Relationships

Post-Column Infusion for Suppression Profiling

The post-column infusion method is a widely used technique for identifying chromatographic regions affected by ion suppression [1] [20].

Protocol:

- Prepare a standard solution containing the analyte of interest at a concentration that produces a consistent signal.

- Use a syringe pump and a 'tee union' to continuously infuse this standard post-column into the mobile phase flow.

- Inject a blank matrix extract onto the LC system under analytical conditions.

- Monitor the detector response throughout the chromatographic run.

- Observe decreases in the otherwise constant signal; these dips indicate retention times where matrix components cause ion suppression [1].

- Repeat with different chromatographic conditions to identify separation approaches that minimize co-elution of suppressors with target analytes.

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Modeling

Advanced modeling approaches can predict ionization efficiency based on molecular structure [21].

Protocol:

- Select a diverse set of compounds representing structural variability.

- Derivatize compounds systematically to alter specific physicochemical properties (e.g., acylation to increase hydrophobicity).

- Measure ESI response for all compounds under identical instrumental conditions.

- Calculate molecular descriptors (volume, log P, pKa, surface tension) using computational chemistry software.

- Develop a multivariate model correlating descriptors with observed ESI response.

- Validate the model with a test set of compounds not included in model development.

- Apply the validated model to predict ionization efficiency and suppression susceptibility for new compounds [21].

Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard Methods

The IROA TruQuant workflow uses isotopic labeling to directly measure and correct for ion suppression [22].

Protocol:

- Spike samples with a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (IROA-IS) library at constant concentration.

- Prepare a long-term reference standard (IROA-LTRS) as a 1:1 mixture of chemically equivalent standards at 95% ¹³C and 5% ¹³C.

- Analyze samples using LC-MS under standardized conditions.

- Identify true metabolites based on their characteristic IROA isotopolog ladder pattern.

- Calculate ion suppression for each metabolite using the formula comparing ¹²C and ¹³C channels.

- Apply suppression correction algorithms to generate accurate quantitative data [22].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental approach for systematic investigation of property-suppression relationships:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ion Suppression Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Suppression Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| IROA Internal Standard Library | Stable isotope-labeled standards for suppression measurement and correction | Quantifying ion suppression across 1% to >90% range in diverse matrices [22] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) derivatives | Systematically increasing molecular volume and altering properties | Demonstrating correlation between molecular size and ESI response [21] |

| Organic acid anhydrides | Acylation reagents for modifying hydrophobicity and surface activity | Creating amino acid derivatives with progressively increasing chain length [21] |

| Stable isotope-labeled analogs | Internal standards for compensation of suppression effects | Correcting for variable ionization efficiency across samples [2] [20] |

| Phospholipid removal cartridges | Selective removal of major suppression-causing matrix components | Overcoming suppression of triacylglycerols by phospholipids [23] |

| Post-column infusion kit | Experimental setup for suppression mapping | Identifying chromatographic regions affected by ion suppression [1] |

The susceptibility of an analyte to ion suppression in ESI-MS is not a random occurrence but a predictable consequence of its physicochemical properties. Molecular volume, surface activity, hydrophobicity, basicity, and gas-phase proton affinity collectively determine how effectively a compound competes throughout the ionization process. Understanding these relationships enables researchers to develop more robust analytical methods through strategic property modification, appropriate internal standard selection, and optimized chromatographic separation. For drug development professionals, this knowledge is crucial for achieving reliable quantification in complex biological matrices, ultimately supporting critical decisions in pharmacokinetic studies and therapeutic monitoring. Future research will likely focus on developing more comprehensive predictive models that integrate multiple physicochemical parameters to forecast suppression susceptibility prior to method development.

Ion suppression in Electrospray Ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry represents a fundamental challenge that directly compromises data quality across pharmaceutical development and bioanalytical research. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic origins of ion suppression in ESI interfaces and details its profound consequences on analytical outcomes, including false negatives, compromised accuracy, and degraded precision. Furthermore, we present validated experimental protocols for detecting and quantifying these effects, alongside emerging strategies for their mitigation. Within the broader context of ion suppression fundamentals, understanding these data quality impacts is essential for developing robust, reliable LC-MS methods.

Ion suppression describes the phenomenon where the presence of co-eluting compounds in the LC-MS interface reduces the ionization efficiency of an analyte of interest [2] [1]. This matrix effect occurs prior to mass analysis and results from competition for limited charge or space within ESI droplets, fundamentally altering detector response [1]. Unlike isobaric interference, ion suppression affects ionization efficiency itself, making its effects particularly insidious because they can escape detection in seemingly clean chromatograms [2]. In drug development, where accurate quantification is paramount, uncontrolled ion suppression can invalidate method validity, leading to incorrect decisions based on flawed data.

Core Mechanisms Leading to Data Quality Impacts

The primary mechanisms of ion suppression in ESI revolve around competition in the condensed phase before ions enter the gas phase.

- Charge Competition: ESI droplets have a limited excess charge available. In multicomponent samples, compounds with superior surface activity or basicity can dominate the droplet surface, effectively "out-competing" analytes of interest for this charge, thereby suppressing their ionization [1].

- Physical Interference: High concentrations of non-volatile or matrix components can increase droplet viscosity and surface tension, thereby reducing the efficiency of solvent evaporation and droplet fission. This physically impedes the transfer of analyte ions into the gas phase [2] [1].

- Saturation Effects: At high analyte concentrations (>10⁻⁵ M), the linearity of the ESI response is often lost. This saturation, caused by limited charge or droplet surface area, inhibits the ejection of ions from within the droplets [1].

Quantitative Impact on Data Quality

The mechanisms of ion suppression directly manifest in three critical, quantifiable impairments of data quality.

False Negatives

Ion suppression can depress an analyte's signal below the method's limit of detection, leading to a false negative reporting outcome [1]. The severity of this effect is concentration-dependent; a higher analyte/matrix ratio can yield a reduced suppression effect [2]. In practice, an analyte present at a clinically or pharmacologically relevant concentration may go unreported if severe ion suppression from co-eluting matrix components diminishes its signal to an undetectable level.

Reduced Accuracy

Analytical accuracy—the closeness of a measured value to a true value—is severely compromised by ion suppression. The extent of inaccuracy can be quantitatively described as (100 - B)/(A × 100), where A and B are the unsuppressed and suppressed signals, respectively [1]. Recent research in non-targeted metabolomics has documented that ion suppression can reduce signal accuracy for individual metabolites by anywhere from 1% to over 90%, depending on the chromatographic system, ionization mode, and sample cleanliness [5]. This introduces significant and variable bias into quantitative results.

Poor Precision

The natural variation of endogenous compounds in biological samples causes varying levels of ion suppression between sample runs [1]. This variation introduces both systematic and random error, adversely affecting the precision of the signal response and intensity ratios [1]. Coefficients of variation (CV) for suppressed analytes can range from 1% to 20% due to these fluctuating matrix effects [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Ion Suppression on Data Quality

| Data Quality Parameter | Manifestation | Quantitative Range | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| False Negatives | Signal falls below LOD | Concentration-dependent [2] | Severe signal suppression from co-eluting interferents [1] |

| Reduced Accuracy | Biased quantification | 1% to >90% signal loss [5] | Variable ionization efficiency across samples [1] |

| Poor Precision | High run-to-run variability | CVs of 1% to 20% [5] | Fluctuating matrix component concentrations [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Assessment

Robust method validation requires specific experimental protocols to characterize the presence and extent of ion suppression.

Post-Column Infusion Assay

This method provides a chromatographic profile of ion suppression [1] [5].

Detailed Protocol:

- Setup: Connect a syringe pump containing a solution of the analyte at an appropriate concentration to the LC effluent post-column via a tee union.

- Infusion: Initiate a constant infusion of the analyte, creating a stable background signal in the mass spectrometer.

- Injection: Inject a blank, prepared sample matrix (e.g., plasma extract) into the LC system and run the chromatographic method.

- Detection: Monitor the detector response. A drop in the otherwise constant baseline indicates the retention time windows where co-eluting matrix components are causing ion suppression of the infused analyte (see Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1: Workflow for the post-column infusion assay to identify ion suppression zones.

Post-Extraction Spiking Assay

This method quantifies the absolute extent of ion suppression for a given analyte [1].

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Samples:

- Sample A: Pure analyte in neat mobile phase.

- Sample B: Blank sample matrix extract, spiked with the same amount of analyte post-extraction.

- Sample C: Blank sample matrix put through the entire sample preparation protocol and then spiked with the analyte.

- Analysis: Analyze all three samples using the developed LC-MS method.

- Calculation: Compare the peak responses (area or height).

- The comparison between A and B reveals the total ion suppression effect.

- The comparison between B and C helps differentiate ion suppression from signal loss caused by inefficient recovery during sample preparation [2].

Strategies for Mitigating Data Quality Impacts

A multi-pronged approach is necessary to counteract the effects of ion suppression on data quality.

Chromatographic and Sample Preparation Solutions

- Improved Chromatographic Separation: Modifying the LC method to shift the retention time of the analyte away from the major region of ion-suppressing components is a primary defense [2].

- Advanced Sample Cleanup: Replacing simple protein precipitation with techniques like Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) or Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) can effectively remove ion-suppressing species from the sample matrix prior to analysis [2] [1].

- Source Selection: Switching from ESI to Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which is generally less prone to ion suppression, can be a viable strategy for some analytes [1].

Internal Standardization and Normalization

The use of internal standards (IS) is critical for compensating for variability in ionization efficiency.

- Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS): These are the gold standard. The SIL-IS is chemically identical to the analyte and behaves identically during sample preparation and ionization, but is distinguished by mass. Any ion suppression affecting the analyte will equally affect the IS, allowing the analyte/IS response ratio to correct for the suppression [2] [5].

- IROA Workflow: For non-targeted metabolomics, the Isotopic Ratio Outlier Analysis (IROA) workflow uses a ¹³C-labeled internal standard library. It measures the ion suppression of each metabolite in the library using a defined algorithm and corrects for it, thereby restoring quantitative accuracy and precision [5].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions for Ion Suppression Mitigation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-IS) | Normalizes for analyte loss during prep and ion suppression during analysis; enables accurate quantification [2]. | Targeted analysis of specific drugs or metabolites. |

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | A library of ¹³C-labeled metabolites used to measure and correct for ion suppression across many analytes simultaneously in a non-targeted workflow [5]. | Non-targeted metabolomics, biomarker discovery. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration Standards | Calibrators prepared in the same biological matrix as samples to mimic suppression effects and compensate for accuracy loss [2]. | Targeted bioanalysis when analyte-free matrix is available. |

| High-Purity Mobile Phase Additives | Reduce background noise and unintended chemical interactions that can exacerbate ionization instability and suppression. | General LC-MS method development. |

Figure 2: A multi-faceted strategy is required to effectively mitigate the impacts of ion suppression on data quality.

Ion suppression in ESI-MS is not a mere theoretical concern but a pervasive phenomenon with severe, quantifiable consequences for data quality. It directly generates false negatives, reduces analytical accuracy, and degrades measurement precision, thereby threatening the validity of decisions in drug development and clinical research. The post-column infusion and post-extraction spiking assays provide robust experimental means to characterize this threat during method validation. Ultimately, a comprehensive strategy combining superior chromatography, effective sample cleanup, and—most crucially—the application of stable isotope-labeled internal standards or advanced workflows like IROA, is essential to nullify the effects of ion suppression and ensure the generation of reliable, high-quality data.

Advanced Strategies to Measure and Correct for Ion Suppression

Ion suppression represents a fundamental challenge in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), particularly when analyzing complex biological samples. This phenomenon occurs when matrix components co-eluting with analytes of interest interfere with the ionization process, leading to reduced detector response and compromising data accuracy [1] [2]. In liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), ion suppression manifests as reduced ionization efficiency for target analytes due to competition for charge between the analyte and co-eluting species present in the sample matrix [17] [2].

The mechanisms of ion suppression vary depending on ionization technique. In ESI, proposed mechanisms include competition for limited charge available on ESI droplets, increased solution viscosity and surface tension reducing solvent evaporation efficiency, and the presence of non-volatile materials that prevent droplets from reaching the critical radius required for gas phase ion emission [1] [2]. The extent of suppression is influenced by multiple factors including the physicochemical properties of interfering compounds, their concentration relative to the analyte, chromatographic conditions, and ionization source parameters [17] [1].

The consequences of unchecked ion suppression are severe across analytical applications, leading to reduced detection capability (potentially yielding false negatives), impaired precision and accuracy, and nonlinear response curves [1] [2]. Until recently, strategies to mitigate ion suppression have included extensive sample cleanup, chromatographic method optimization, sample dilution, and the use of internal standards [17] [1]. However, these approaches have proven insufficient for non-targeted metabolomics, where the diverse chemical properties of hundreds to thousands of metabolites preclude finding a universal solution [22] [22].

The IROA Approach: Fundamental Principles

The IROA TruQuant Workflow introduces a paradigm shift in addressing ion suppression through the innovative application of stable isotope-labeled standards [22] [24]. This approach leverages the unique properties of isotopic patterning to both identify and computationally correct for ion suppression effects across the entire metabolome.

At the core of the IROA methodology are two specialized standards: the IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) and the IROA Long-Term Reference Standard (IROA-LTRS) [22]. The IROA-IS is spiked into all experimental samples at constant concentration, while the IROA-LTRS serves as a consistent reference across multiple experiments. The power of this system lies in the distinctive isotopic labeling pattern: the IROA-IS incorporates 95% ^13C, creating a recognizable mass spectrometric signature that differentiates it from natural abundance compounds (approximately 99% ^12C) [22] [24].