Ionization Efficiency in Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Ionization efficiency—the effectiveness of converting neutral analyte molecules into gas-phase ions—is a cornerstone parameter that directly dictates the sensitivity, quantitative accuracy, and overall success of mass spectrometric analyses.

Ionization Efficiency in Mass Spectrometry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Ionization efficiency—the effectiveness of converting neutral analyte molecules into gas-phase ions—is a cornerstone parameter that directly dictates the sensitivity, quantitative accuracy, and overall success of mass spectrometric analyses. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of ionization efficiency, from its fundamental physical principles and governing equations to its critical role in modern methodologies like LC-MS and TIMS. It offers researchers and drug development professionals a systematic framework for troubleshooting and optimizing ionization, utilizing advanced approaches such as Design of Experiments (DoE). Furthermore, it addresses the pivotal challenge of validation, covering the use of internal standards and comparative techniques to ensure reliable data across diverse biomedical applications, from metabolomics to proteomics.

The Fundamentals of Ionization Efficiency: Principles and Governing Equations

In mass spectrometry, ionization efficiency is the critical process that determines the success of all subsequent analysis. It fundamentally represents the effectiveness with which neutral analyte molecules in a sample are converted into gas-phase ions that can be manipulated and detected by the mass spectrometer [1]. This efficiency serves as the essential bridge between the sample introduction system and the mass analyzer, dictating the sensitivity, dynamic range, and ultimately the quality of the analytical data obtained. For researchers in pharmaceuticals and biomarker discovery, where samples are often complex and analytes present at trace concentrations, understanding and optimizing ionization efficiency is not merely beneficial—it is imperative for obtaining meaningful biological results [2] [3].

The importance of ionization efficiency extends beyond simple signal intensity. In electrospray ionization (ESI) studies of non-covalent protein-ligand complexes, for instance, the ionization process must be gentle enough to preserve solution-phase equilibrium concentrations while simultaneously providing sufficient ion yield for detection [4]. The efficiency of this transformation from neutral molecule to gas-phase ion is governed by a complex interplay of physicochemical properties of the analyte, the ionization technique employed, and numerous instrumental parameters that can be optimized [3]. This whitepaper explores the fundamental principles, measurement approaches, and optimization strategies for ionization efficiency, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for maximizing this critical link between sample and signal.

Theoretical Foundations and Defining Principles

Quantitative Definition and Key Parameters

Ionization efficiency can be quantitatively defined by several interrelated parameters that provide a framework for its evaluation. In the context of electron ionization (EI), the sample ion current (I+) provides a measurable quantity representing the ionization rate, described by the equation:

I+ = βQiL[N]Ie

where:

- β represents the ion extraction efficiency

- Qi is the total ionizing cross-section

- L is the effective ionizing path length

- [N] is the concentration of sample molecules

- Ie is the ionizing current [5]

This relationship highlights that ionization efficiency depends not only on the inherent properties of the analyte (Qi) but also on instrumental factors that can be optimized. The ionization cross-section of an atom or molecule is a critical property that determines its probability of ionization under specific conditions and can be measured across different electron energies [1]. For molecular systems, the additivity rule postulated by Otvos and Stevenson allows approximation of molecular ionization cross-sections from atomic constituents, though this provides only a rough estimate accurate within a factor of two [1].

A more generalized definition applicable across ionization techniques conceptualizes ion utilization efficiency as the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to gas-phase ions and transmitted through the mass spectrometer interface [6]. This holistic view encompasses not only the initial ionization event but also the subsequent transmission losses, providing a more complete picture of overall system performance for sensitive applications like biomarker detection [2].

Comparative Efficiencies Across Ionization Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Ionization Efficiencies Across Common Mass Spectrometry Techniques

| Ionization Technique | Typical Efficiency Range | Optimal Application Domain | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) | ~0.1% (1 in 1000 molecules ionized at 70 eV) [5] | Low MW organic compounds (<600 amu), volatile samples [5] | Electron energy (optimized at 70 eV), ionization cross-section, ionizing current [5] |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Highly compound-dependent; can be significantly enhanced with nanoESI [3] [6] | Polar molecules, proteins, non-covalent complexes, LC-MS coupling [7] [4] | Solvent composition, surface activity, gas flows, voltages, in-source fragmentation [7] [3] |

| Multi-Collector ICP-MS | Near 100% for most elements [1] | Elemental analysis, isotope ratio studies [1] | Element-specific, ionization potential |

| Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization | Compound-dependent; often lower than ESI for polar compounds | Less polar small molecules, pharmaceutical compounds | Proton affinity, gas-phase reactions |

The wide variation in reported efficiency ranges underscores the technique- and application-dependent nature of ionization efficiency. The near 100% efficiency reported for Multi-Collector ICP-MS reflects the extremely high temperature plasma source that efficiently atomizes and ionizes most elements in the periodic table [1]. In contrast, the relatively low efficiency of EI (approximately 0.1%) is offset by its excellent reproducibility and extensive fragmentation libraries that facilitate compound identification [5]. For ESI, efficiency is highly compound-specific and heavily influenced by experimental conditions, with nanoelectrospray (nanoESI) demonstrating significantly improved ionization efficiency compared to conventional ESI due to smaller droplet formation and more efficient desolvation [6].

Measurement and Evaluation Methodologies

Experimental Approaches for Efficiency Quantification

Evaluating ionization efficiency requires carefully designed experimental strategies that correlate solution-phase analyte concentration with detected ion signal. The fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing between actual ionization efficiency and subsequent transmission losses through the instrument interface [6]. Two primary approaches have emerged for this assessment:

Targeted Standard Evaluation: This conventional approach uses large panels of metabolite or analyte standards to systematically measure response factors across different compound classes [3]. While comprehensive, this method is time-consuming and costly, requiring careful preparation and analysis of numerous standard solutions.

Non-Targeted Feature-Based Evaluation: This innovative approach uses dilution series of test samples (e.g., biofluids) and statistical analysis of all detected mass spectral features to compare instrumental setups without chemical identification [3]. This method offers practical advantages of speed and cost-effectiveness while still providing robust assessment of overall system performance.

For ESI-MS interfaces specifically, researchers have developed methods to measure the total gas-phase ion current transmitted through the interface and correlate it with the observed ion abundance in mass spectra [6]. This allows calculation of the ion utilization efficiency which encompasses both the initial ionization and subsequent transmission. Experimental results using this methodology have demonstrated that subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) MS interface configurations exhibit superior ion utilization efficiency compared to conventional inlet capillary-based ESI-MS interfaces [6].

Statistical Design for Systematic Optimization

Beyond simple evaluation, Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches provide powerful statistical frameworks for systematically optimizing multiple ionization parameters simultaneously [7] [4]. Unlike traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, DoE efficiently explores complex parameter spaces and identifies interactions between factors that significantly influence ionization efficiency [7].

A representative DoE workflow for ESI optimization typically involves:

- Factor Screening: Identifying which of many potential parameters (e.g., gas temperatures, flow rates, voltages) significantly influence ionization efficiency

- Response Surface Methodology: Modeling the relationship between significant factors and ionization response to identify optimal regions

- Robustness Testing: Verifying that the identified optimal conditions perform consistently with minor expected variations [7]

This approach was successfully applied to optimize ESI conditions for supercritical fluid chromatography-mass spectrometry (SFC-MS) coupling, where eight different ESI factors were systematically evaluated using a geometric experimental design [7]. Similarly, DoE with inscribed central composite designs (CCI) has been employed to establish optimal ESI conditions for accurate determination of protein-ligand binding constants [4].

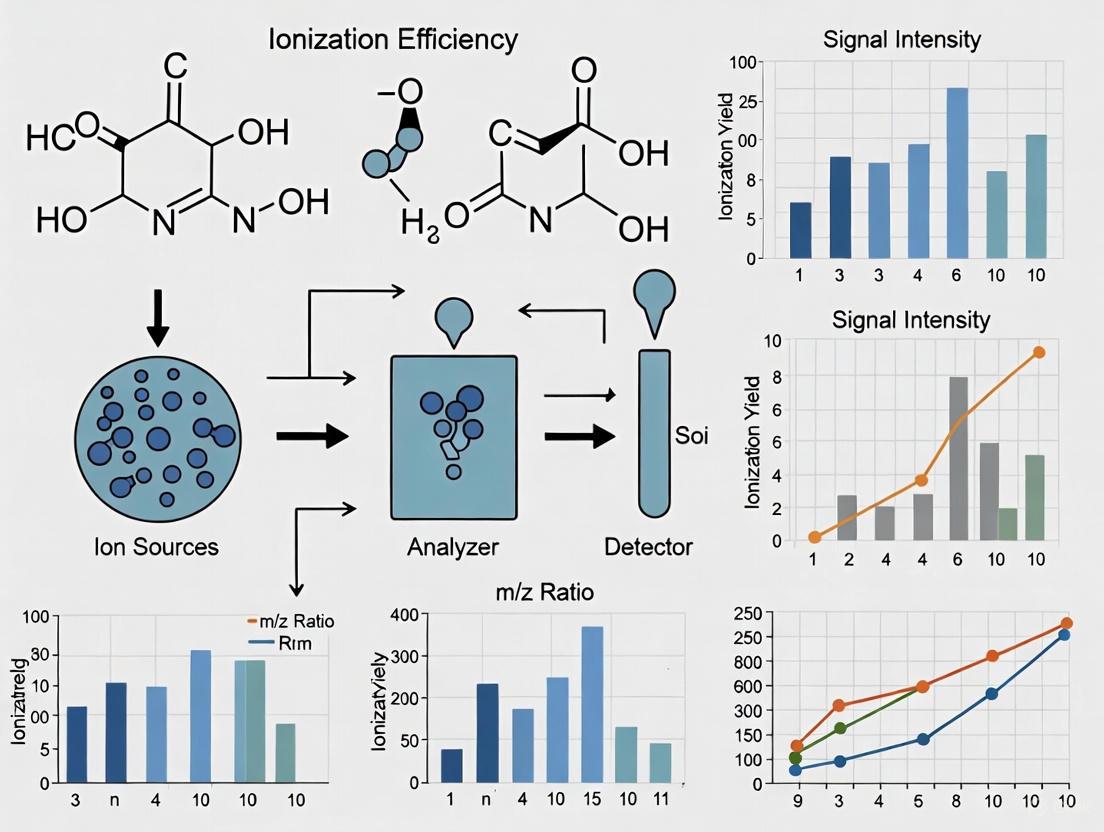

Diagram 1: DoE Optimization Workflow for ESI Parameters

Practical Optimization Strategies

Technique-Specific Optimization Parameters

Each ionization technique presents unique optimization parameters that directly impact ionization efficiency:

For Electron Ionization (EI):

- Filament current controls electron production through thermionic emission [5]

- Electron energy is typically optimized at 70 eV where the de Broglie wavelength of electrons matches typical organic bond lengths, maximizing energy transfer [5]

- Ionizing path length can be increased using weak magnetic fields to force electrons into helical paths [5]

- Ion extraction efficiency is optimized by adjusting repeller and acceleration voltages [5]

For Electrospray Ionization (ESI):

- Source gas parameters (drying gas temperature and flow, sheath gas settings) significantly influence droplet desolvation [7] [3]

- Voltage settings (capillary, nozzle, fragmentor) control ion formation, declustering, and transmission [7]

- Solvent composition and flow rate directly impact droplet formation and charge concentration [6] [4]

- Source geometry and emitter position relative to the inlet affect ion sampling efficiency [6]

In ESI-MS studies of non-covalent protein-ligand complexes, optimization must balance multiple competing objectives: maximizing ionization efficiency while minimizing complex dissociation during the ESI process and maintaining native solution-phase equilibrium concentrations [4]. This requires careful tuning of "soft" ionization conditions that gently transfer the complex into the gas phase without disrupting non-covalent interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ionization Efficiency Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Ionization Studies | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Standard Libraries | Provides known compounds for systematic evaluation of ionization response across chemical space [3] | Targeted evaluation of ESI efficiency for different compound classes [3] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Corrects for variance in ionization efficiency due to matrix effects [2] | Quantitative proteomics and metabolomics [2] |

| Model Protein-Ligand Systems | Enable optimization of "soft" ionization conditions for non-covalent complexes [4] | ESI-MS studies of protein-ligand interactions (e.g., PvGK with GMP/GDP) [4] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Modify solution chemistry to enhance ionization (e.g., ammonium acetate, formic acid) [7] [4] | LC-ESI-MS method development for small molecules and proteins [7] |

| Custom Etched ESI Emitters | Produce stable electrospray with improved ionization efficiency, particularly at low flow rates [6] | Nanoelectrospray MS applications requiring high sensitivity [6] |

Advanced Considerations in Ionization Efficiency

Technological Innovations and Emerging Trends

Recent technological developments continue to push the boundaries of ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry. Nanoelectrospray ionization (nanoESI) operates at nL/min flow rates, significantly improving ionization efficiency compared to conventional ESI through the production of smaller initial droplets with higher charge-to-volume ratios [6]. The Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface removes the conventional inlet capillary, placing the ESI emitter directly in the first vacuum stage of the mass spectrometer, thereby reducing transmission losses and improving overall ion utilization efficiency [6].

ESI emitter arrays represent another innovation, functioning as "brighter" ion sources that increase total available ion current [6]. When coupled with advanced interface designs like the SPIN-MS, these emitter arrays demonstrate significantly improved ionization and transmission characteristics compared to single-emitter configurations [6]. For high-throughput screening applications, multi-capillary inlets arranged in hexagonal patterns have shown promise in increasing sampling efficiency from multiple ESI sources [6].

Beyond hardware innovations, data analysis approaches continue to evolve. Advanced feature evaluation strategies that combine intensity-based statistics with chemical interpretation provide more comprehensive assessment of ionization performance across diverse compound classes [3]. These approaches are particularly valuable in nontargeted analysis where chemical standards are unavailable for many detected features.

Addressing In-Source Processes and Artifacts

Ionization efficiency cannot be considered in isolation from in-source processes that may compromise data quality. In-source fragmentation represents a significant challenge, where excessive internal energy deposited during ionization leads to dissociation of labile compounds before mass analysis [3]. This not reduces the intensity of molecular ions but generates fragment ions that can be misinterpreted as separate compounds. The degree of in-source fragmentation varies significantly between analytes and must be carefully controlled through parameter optimization [3].

Ion suppression effects present another critical consideration, particularly in ESI analysis of complex mixtures [7]. When multiple analytes co-elute, competition for available charge and droplet surface area can significantly reduce ionization efficiency for less competitive compounds [7]. This matrix-dependent phenomenon underscores the importance of effective chromatographic separation and appropriate internal standards for quantitative work [2].

Diagram 2: Ionization Challenges in the ESI Process

Ionization efficiency represents far more than a simple conversion metric—it is the fundamental bridge between sample composition and detectable signal that dictates the success of mass spectrometric analysis. As mass spectrometry continues to expand into new application areas including clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, and regulatory analysis, the demand for robust, efficient, and reproducible ionization methods will only intensify [2] [3]. The systematic approaches to evaluation and optimization outlined in this whitepaper provide researchers with a framework for maximizing this critical link in their analytical workflows. Through continued innovation in ionization sources, interface designs, and optimization methodologies, the field moves steadily toward the ultimate goal of comprehensive, unbiased detection of all analytes in complex samples—a goal that rests squarely on the foundation of ionization efficiency.

Ionization efficiency is a critical performance parameter in mass spectrometry (MS), defined as the ability of a technique to effectively convert analyte molecules in a sample into gaseous ions that can be detected and analyzed [8]. This parameter directly determines the sensitivity and detection limits of a mass spectrometry method, as it governs the number of ions available for detection and measurement [8]. Higher ionization efficiency yields a greater number of analyte ions, resulting in improved signal-to-noise ratios and enhanced capability for detecting trace-level compounds [8]. In the broader context of mass spectrometry research, understanding and optimizing ionization efficiency is fundamental across diverse applications, from drug development and proteomics to environmental analysis and clinical diagnostics.

The ionization process represents the foundational step in mass spectrometry, where neutral molecules are transformed into charged ions capable of being manipulated by electric and magnetic fields within the mass spectrometer [9] [10]. This process occurs in the ion source, where samples—whether solid, liquid, or gas—are converted into gaseous ions before being introduced to the mass analyzer [9]. The efficiency of this conversion process is influenced by multiple physical principles, primarily governed by the work function of ionization surfaces, the ionization potential of elements and molecules, and the theoretical framework described by the Saha-Langmuir equation.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Ionization Efficiency

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Role in Ionization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Function | φ | Minimum energy needed to remove an electron from a solid surface | Determines surface's ability to donate/accept electrons during ionization |

| Ionization Potential/Energy | IE | Energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom/molecule | Indicates how easily an atom/molecule forms positive ions |

| Electron Affinity | EA | Energy change when an electron is added to a neutral atom/molecule | Indicates how easily an atom/molecule forms negative ions |

| Ionization Efficiency | α | Ratio of ionized particles to neutral particles | Direct measure of ionization effectiveness |

Theoretical Foundations

Work Function (φ)

The work function (φ) represents a fundamental surface property defined as the minimum energy required to remove an electron from the solid surface of a material to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the surface [11]. This parameter plays a crucial role in surface ionization techniques, where the ionization process occurs on hot metal surfaces such as rhenium, tantalum, or platinum filaments [12]. The work function value determines the surface's ability to either donate or accept electrons during the ionization process, thereby directly influencing the efficiency of ion formation.

In practical mass spectrometry applications, the work function of the ionization surface material must be carefully selected based on the specific analytes being investigated. For efficient positive ion formation, surfaces with high work functions are preferred as they more readily donate electrons to analyte molecules. Conversely, for negative ion formation, surfaces with lower work functions facilitate more efficient electron transfer from the surface to the analyte molecules [11]. Research has demonstrated that the composition of the ionization chamber itself can influence ionization efficiency, as different materials possess characteristic work function values that either enhance or diminish ion yields for specific applications [11].

Ionization Potential (IP) and Electron Affinity (EA)

Ionization potential (IP), also referred to as ionization energy, represents the minimum energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom or molecule, thereby converting it into a positive ion [12]. This fundamental atomic property varies significantly across different elements, with elements such as rubidium and strontium possessing low ionization potentials that facilitate ionization at lower temperatures, while elements like thorium and uranium with high ionization potentials require significantly higher temperatures for effective ionization [12].

Electron affinity (EA) represents the complementary parameter, defined as the energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a neutral atom or molecule in the gaseous state to form a negative ion [11]. The electron affinity values for common oxygen-containing molecules illustrate the range of this parameter, from -0.60 eV for CO₂ to 2.27 eV for NO₂ [11]. The relationship between the work function of the ionization surface and the electron affinity of the analyte molecule determines the efficiency of negative ion formation, with optimal conditions occurring when the work function is comparable to or lower than the electron affinity [11].

Table 2: Electron Affinity Values for Oxygen-Containing Molecules

| Molecule/Atom | Electron Affinity (eV) | Filament Temperature for O⁻ Formation (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| O₂ | 0.45 | 1548-1721 (depending on molecule) |

| CO₂ | -0.60 | 1548-1721 (depending on molecule) |

| CO | 1.33 | 1548-1721 (depending on molecule) |

| NO | 0.026 | 1548-1721 (depending on molecule) |

| NO₂ | 2.27 | 1548-1721 (depending on molecule) |

| O | 1.46 | Not Applicable |

The Saha-Langmuir Equation

The Saha-Langmuir equation provides the fundamental theoretical framework describing thermal surface ionization processes, establishing the quantitative relationship between temperature, surface properties, and analyte characteristics in determining ionization efficiency [12] [11]. This equation mathematically expresses the degree of ionization (α) for both positive and negative ion formation under thermal equilibrium conditions.

For positive ionization, the Saha-Langmuir equation is expressed as:

[ \alpha{+} = \frac{N{+}}{N{0}} = \frac{g{+}}{g_{0}} \exp\left(\frac{\phi - IP}{kT}\right) ]

For negative ionization, the equation takes the form:

[ \alpha{-} = \frac{N{-}}{N{0}} = \frac{g{-}}{g_{0}} \exp\left(\frac{EA - \phi}{kT}\right) ]

Where:

- (N{+}), (N{-}), and (N_{0}) represent the numbers of positive ions, negative ions, and neutral molecules, respectively

- (g{+}/g{0}) and (g{-}/g{0}) are the ratios of statistical weights of the ions and neutral molecules

- (\phi) is the work function of the surface material

- (IP) is the ionization potential of the analyte

- (EA) is the electron affinity of the analyte

- (k) is the Boltzmann constant

- (T) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin [11]

The exponential dependence of ionization efficiency on the difference between work function and ionization potential (or electron affinity for negative ions) explains the high sensitivity of thermal ionization processes to temperature optimization and surface selection. This theoretical framework guides experimental design in thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS), enabling researchers to maximize ionization efficiency for specific target analytes through appropriate choice of filament materials and temperature profiles [12] [11].

Ionization Techniques and Their Efficiencies

Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS)

Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry employs heated metal filaments to vaporize and ionize samples based on the principles described by the Saha-Langmuir equation [12]. The instrumental configuration consists of four main systems: an ion source with one or more metal filaments (typically rhenium, tantalum, or platinum), a beam collimator, a magnet for mass separation, and a detector, along with supporting vacuum systems, power supplies, and computer controls [12].

In TIMS operation, the sample is loaded as a solid compound directly onto the filament, sometimes with the addition of an activator to enhance ionization efficiency [12]. As the filament temperature increases, the sample evaporates and ionizes simultaneously, or alternatively, vapor molecules are ionized by contact with a separate ionization filament maintained at a significantly higher temperature [12]. The temperature dependence follows the Saha-Langmuir equation, with elements possessing low ionization potentials (such as Rb and Sr) ionizing at lower temperatures than those with high ionization potentials (such as Th and U) [12]. For some challenging elements like lead, the use of an activator is essential to achieve practical ionization efficiency, while for elements like osmium, the ionization potential favors the formation of negative ions (OsO₃⁻) [12].

Electron Ionization (EI) and Other Techniques

Electron Ionization represents a "hard" ionization technique that employs high-energy electrons (typically 70 eV) to bombard vaporized sample molecules, resulting in the ejection of electrons and formation of positive ions [9] [10]. This method typically produces significant fragmentation, generating numerous fragment ions that provide valuable structural information but may reduce the abundance of the molecular ion [9] [10]. EI operates with high ionization efficiency and sensitivity for organic compounds with molecular weights below 600 Da, finding applications in environmental, forensic, archaeological, and pharmaceutical analysis [9].

Alternative ionization techniques have been developed to address different analytical needs and sample types. Soft ionization techniques, including Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), impart less energy to analyte molecules during the ionization process, resulting in minimal fragmentation and predominant molecular ion peaks [9]. These techniques are particularly valuable for analyzing large, thermally labile biomolecules such as proteins, peptides, and nucleotides [9]. Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) and Atmospheric Pressure Photo Ionization (APPI) represent additional soft ionization methods suitable for different compound classes, with APCI effective for polar and thermally stable non-polar compounds, and APPI particularly useful for weakly polar and non-polar compounds such as pesticides, steroids, and drug metabolites [9].

Table 3: Comparison of Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Ionization Technique | Ionization Type | Typical Analytes | Efficiency Characteristics | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Ionization (TIMS) | Surface | Elements, Isotopes | Highly efficient for elements with low IP | Isotope ratio analysis, geochronology |

| Electron Ionization (EI) | Gas Phase (Hard) | Small organics (<600 Da) | High ionization efficiency, extensive fragmentation | Unknown identification, forensic analysis |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Soft | Peptides, proteins, nucleotides | High efficiency for large biomolecules, multiple charging | Proteomics, pharmaceutical analysis |

| MALDI | Soft | Large biomolecules, polymers | High efficiency for fragile molecules | Pathology, protein identification |

| ICP | Hard | Trace metals, non-metals | Highly efficient element ionization | Trace element analysis, clinical labs |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Thermal Ionization Experimental Protocol

The investigation of negative ion formation from oxygen-containing molecules provides a detailed experimental framework for studying ionization efficiency [11]. This protocol examines O⁻ formation from simple gases (O₂, CO₂, CO, NO, and NO₂) by analyzing the dependence of O⁻ ion current intensity on filament temperature, identifying optimal temperatures ranging from 1548 to 1721°C for different gases [11].

Instrument Configuration:

- Ion source with spiral cathode (filament) made of MoRe alloy

- Ionization chamber constructed of tantalum positioned proximate to filament

- Vacuum system maintaining appropriate pressure for ion transmission

- Temperature measurement and control system for precise filament heating

- Electrical current detection system (picoammeter) for ion current measurement [11]

Experimental Procedure:

- The filament temperature is gradually increased while introducing the target gas

- The O⁻ ion current is monitored continuously as a function of temperature

- Temperature is calibrated using optical pyrometry or resistance measurements

- Ion current measurements are averaged from multiple consecutive readings (typically 100 measurements) to ensure statistical significance

- The optimal temperature for maximum O⁻ yield is identified for each gas compound

- The relationship between ion current intensity and temperature is analyzed according to the Saha-Langmuir equation [11]

Data Interpretation: The experimental data revealed distinct formation pathways for different gases. For NO₂, the process likely involves a two-step dissociation mechanism where molecular oxygen (O₂) forms in the initial step, subsequently dissociating into O⁻ and O atoms. In contrast, for CO, O⁻ formation occurs predominantly through electron capture followed by molecular dissociation [11]. These pathway differences manifest as variations in the temperature dependence of ion current intensity, with each gas exhibiting a characteristic temperature profile for optimal O⁻ formation [11].

Electrospray Ionization Efficiency Protocol

The evaluation of Electrospray Ionization efficiency presents distinct methodological considerations, focusing on the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to gas phase ions and transmitted through the MS interface [6]. This protocol employs a systematic approach to quantify ionization and transmission efficiencies across different ESI-MS interface configurations.

Experimental Design:

- Preparation of standard peptide solutions (angiotensin I, angiotensin II, bradykinin, etc.) at defined concentrations

- Comparison of different interface configurations: single capillary inlet, multi-capillary inlet, and SPIN (Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray) interface

- Use of tandem ion funnel interface with variable RF voltages and DC gradients

- Correlation of transmitted electric current with observed ion abundance in mass spectra [6]

Measurement Approach:

- The total gas phase ion current transmitted through the interface is measured using the low pressure ion funnel as a charge collector connected to a picoammeter

- The corresponding ion abundance is simultaneously measured in the mass spectrum as total ion current (TIC) or extracted ion current (EIC) for specific analytes

- Measurements are performed across different interface configurations and operating parameters

- The ion utilization efficiency is calculated as the proportion of analyte molecules converted to detectable gas phase ions [6]

Key Findings: Experimental results demonstrated that the overall ion utilization efficiency of SPIN-MS interface configurations exceeded that of conventional inlet capillary-based ESI-MS interfaces [6]. The highest transmitted ion current was achieved using the SPIN interface with an ESI emitter array combination, highlighting the importance of both ionization source brightness and interface transmission characteristics in determining overall MS sensitivity [6].

Visualization of Ionization Processes

Thermal Ionization Experimental Workflow

Saha-Langmuir Principle Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions for Ionization Efficiency Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ionization Efficiency Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Ionization Research |

|---|---|---|

| MoRe Alloy Filament | High-temperature resistant | Electron emission source for thermal ionization studies |

| Tantalum Ionization Chamber | Work function: 4.25 eV | Alternative ionization surface for negative ion studies |

| Rhenium/Tantalum/Platinum Filaments | Various work functions | Sample vaporization and ionization surfaces for TIMS |

| Standard Peptide Mixtures | Angiotensin I/II, Bradykinin, Neurotensin | ESI ionization efficiency calibration standards |

| High-Purity Gases | O₂, CO₂, CO, NO, NO₂ (research grade) | Negative ion formation pathway studies |

| Matrix Materials | Organic acids (for MALDI) | Energy absorption and transfer in soft ionization |

| Reagent Gases | Methane, isobutane, ammonia (for CI) | Chemical ionization reaction mediators |

| Solvent Systems | 0.1% Formic acid in 10% acetonitrile/water | ESI mobile phase optimization studies |

| Fused Silica Emitters | OD: 150μm, ID: 10μm (etched tips) | Nanoelectrospray ionization source fabrication |

The fundamental physical principles of work function, ionization potential, and the Saha-Langmuir equation provide the theoretical foundation for understanding and optimizing ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry. The work function of ionization surfaces and the ionization potential or electron affinity of analytes collectively determine the thermodynamic feasibility of ion formation, while the Saha-Langmuir equation quantitatively describes the exponential dependence of ionization efficiency on the relationship between these parameters under specific temperature conditions.

Experimental methodologies for evaluating ionization efficiency encompass diverse approaches, from thermal ionization studies measuring ion current as a function of filament temperature to electrospray ionization investigations correlating transmitted ion current with mass spectral abundance. These protocols enable rigorous comparison of ionization techniques and interface configurations, guiding instrument selection and method development for specific analytical challenges.

In the broader context of mass spectrometry research, ionization efficiency remains a central consideration influencing instrument sensitivity, detection limits, and analytical applicability across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, clinical analysis, environmental monitoring, and fundamental chemical research. The continuing refinement of ionization sources and the optimization of ionization conditions based on these fundamental principles promise enhanced analytical capabilities for addressing increasingly complex scientific questions in the future.

Ionization, the process of converting neutral atoms or molecules into charged ions, serves as the critical first step in mass spectrometric analysis, enabling the detection and characterization of chemical compounds by manipulating them with electric and magnetic fields [13]. The choice of ionization technique directly dictates the type of chemical information that can be obtained, influencing everything from molecular weight determination to structural elucidation. Ionization methods are broadly classified into two categories: hard ionization and soft ionization [13]. Hard ionization techniques, such as Electron Ionization (EI), impart high internal energy to analyte molecules, resulting in significant fragmentation that provides valuable structural fingerprints. In contrast, soft ionization methods, including Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), and various plasma-based techniques, transfer minimal internal energy, preferentially producing intact molecular ions with little fragmentation—a crucial capability for analyzing large, labile biomolecules [14] [15] [13].

Within the context of ionization efficiency research, the fundamental challenge lies in understanding and optimizing how effectively a given ionization method can convert neutral molecules of interest into detectable ions across the vast diversity of chemical space. This efficiency directly impacts key analytical figures of merit including sensitivity, limit of detection, and quantitative accuracy, particularly for analytes lacking reference standards [16]. Recent research focuses on expanding ionization capabilities to cover broader chemical spaces, reducing matrix effects that suppress ionization, and developing predictive models that can estimate ionization efficiency based on molecular characteristics [17] [16].

Core Ionization Techniques: Mechanisms and Characteristics

Electron Ionization (EI)

Mechanism: Electron Ionization operates by bombarding vaporized sample molecules with a high-energy beam of electrons (typically 70 eV) generated from a heated filament [13]. When these high-energy electrons collide with analyte molecules (M), they can eject an electron, generating a positively charged molecular ion radical (M⁺•) according to the equation: M + e⁻ → M⁺• + 2e⁻ [13]. The substantial energy transferred during this process typically exceeds chemical bond strengths, causing the molecular ions to undergo extensive fragmentation into smaller daughter ions, which provide characteristic patterns useful for structural identification [13] [18].

Applications and Limitations: EI is extensively used in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for analyzing small organic molecules, hydrocarbons, alcohols, and aromatic compounds [13]. Its major advantages include well-established, reproducible spectral libraries that facilitate compound identification, and the rich structural information provided by fragmentation patterns [14]. However, EI is unsuitable for large or thermally labile compounds like proteins, as the extensive fragmentation can completely destroy the molecular ion, eliminating molecular weight information [13]. A specific pitfall in certain applications is the potential for chemical ionization to inadvertently occur in the electron ionization chamber when analyzing high-concentration gases from electrochemical reactions, potentially scrambling mass-to-charge ratio distributions and misleading analysis [19].

Soft Ionization Techniques

Electrospray Ionization (ESI)

Mechanism: ESI generates ions directly from solution at atmospheric pressure by applying a high voltage (3-5 kV) to a liquid sample flowing through a metal capillary [13]. This creates a fine spray of charged droplets that shrink through solvent evaporation in a heated desolvation zone [13]. As droplet charge density increases, Coulombic explosions occur until gas-phase analyte ions are released, typically as protonated [M+H]⁺ or deprotonated [M-H]⁻ molecules, or as multiply charged species for large biomolecules [13].

Applications and Limitations: ESI excels for polar, non-volatile compounds including peptides, proteins, nucleic acids, and most pharmaceuticals, making it the dominant ionization source for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [17] [15] [13]. Its soft nature preserves molecular integrity but produces limited structural fragmentation unless coupled with tandem MS [18]. Key limitations include pronounced sensitivity to sample contaminants (e.g., salts) and significant matrix effects where co-eluting compounds can suppress or enhance ionization, complicating quantification [17] [15].

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI)

Mechanism: APCI also operates at atmospheric pressure but vaporizes the LC effluent in a heated nebulizer before ionization [13]. The resulting gas-phase solvent and analyte molecules are then exposed to a corona discharge needle that generates primary reagent ions (e.g., H₃O⁺, N₂⁺, O₂⁺) from the solvent vapor [15] [13]. These reagent ions subsequently undergo ion-molecule reactions with analyte molecules through proton transfer, adduct formation, or charge exchange to produce analyte ions like [M+H]⁺ [15] [13].

Applications and Limitations: APCI is particularly effective for medium-to-low polarity compounds that are less amenable to ESI, including sterols, lipids, certain pharmaceuticals, and pesticides [17] [15]. It typically exhibits reduced matrix effects compared to ESI and is less susceptible to adduct formation [17]. However, its applicability is limited for thermally labile compounds that may decompose during the vaporization step [15].

Plasma-Based Ionization Techniques

Mechanism: Dielectric barrier discharge ionization (DBDI) and Flexible Microtube Plasma (FμTP) techniques create non-equilibrium plasma at room temperature using high-voltage alternating current between electrodes separated by a dielectric barrier, typically with noble gases like helium or argon [17]. The plasma contains energetic species (metastable atoms, electrons, ions) that ionize analyte molecules through mechanisms including Penning ionization, charge transfer, or proton transfer, producing [M]⁺• or [M+H]⁺ ions [17].

Applications and Limitations: These emerging techniques demonstrate remarkable versatility across polarity ranges, efficiently ionizing both polar and nonpolar compounds while exhibiting minimal matrix effects compared to ESI [17]. Recent studies show FμTP outperforming ESI for approximately 70% of pesticides tested and demonstrating negligible matrix effects for 76-86% of pesticides across different food matrices [17]. Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI), a related technique, has shown comparable performance to APCI for sterol analysis with superior sensitivity to ESI and robust performance in complex biological matrices [15]. Limitations include the ongoing need to understand fundamental ionization mechanisms, especially when using alternative discharge gases like argon [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Technique | Ionization Mechanism | Analyte Compatibility | Fragmentation Level | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) | High-energy electron bombardment | Volatile, thermally stable small molecules | High (extensive fragmentation) | GC-MS of small organics, structural elucidation |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Charged droplet formation and Coulombic explosion | Polar and non-volatile compounds | Low (intact molecular ions) | LC-MS of biomolecules, pharmaceuticals, metabolites |

| Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) | Corona discharge and gas-phase ion-molecule reactions | Medium-to-low polarity compounds | Low to moderate | LC-MS of sterols, lipids, less polar pharmaceuticals |

| Plasma-Based (FμTP/TPI) | Plasma-induced ionization with discharge gases | Wide polarity range (polar to nonpolar) | Low (intact molecular ions) | Multiclass pesticide screening, sterol analysis |

Current Research Perspectives on Ionization Efficiency

Expanding the Accessible Chemical Space

A primary research focus involves developing ionization techniques capable of addressing the fundamental limitation that "no single method can detect or identify chemicals across the complete scope of the so-called chemical space" [17]. The accessible chemical space refers to the range of compounds that can be effectively ionized and detected by a given analytical method [17]. Plasma-based ionization sources like FμTP represent significant advancements here, demonstrating particularly broad coverage by efficiently ionizing diverse compound classes including ESI-amenable pesticides, traditionally challenging organochlorine contaminants, and sterols in complex biological matrices [17] [15]. This expanded coverage reduces reliance on multiple analytical techniques and enables more comprehensive nontargeted screening from single analyses [17].

Mitigating Matrix Effects and Improving Quantification

Matrix effects—where co-eluting compounds interfere with analyte ionization—represent a major challenge for quantitative analysis, particularly in ESI [17]. Research comparing ionization sources demonstrates that plasma-based techniques like FμTP exhibit significantly reduced matrix effects, with 76-86% of tested pesticides showing negligible matrix effects across different food matrices compared to only 35-67% for ESI [17]. Similarly, Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI) provided stable signals with minimal ion suppression compared to ESI when analyzing sterols in complex samples like human plasma, HepG2 cells, and liver tissue [15]. These characteristics make alternative ionization sources particularly valuable for applications requiring robust quantification in complex matrices.

Predictive Modeling of Ionization Efficiency

Recent research explores computational approaches to predict ionization efficiency (IE) based on molecular characteristics, addressing a fundamental challenge in non-targeted analysis where analytical standards are unavailable [16]. Two promising modeling approaches have emerged: structure-based models using molecular fingerprints, and fragmentation-based models using cumulative neutral losses from MS² spectra [16]. The molecular fingerprint model achieved a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 0.72 logIE units, while the cumulative neutral losses approach, applicable to compounds with unknown structures, achieved a promising RMSE of 0.79 logIE units [16]. These predictive models facilitate more accurate concentration estimations for both identified and unidentified compounds in non-targeted analysis workflows.

Table 2: Recent Technical Advances in Ionization Techniques and Their Impact on Efficiency

| Advancement | Technical Principle | Impact on Ionization Efficiency | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Microtube Plasma (FμTP) | Dielectric guided discharge with singular electrode architecture | Higher sensitivity for 70% of pesticides vs. ESI; negligible matrix effects for 76-86% of pesticides | Multiclass pesticide screening in food matrices; expansion of analyzable chemical space |

| Variable-Energy Electron Ionization | Electrostatic element between e-gun and ion chamber enables tunable electron energy | Avoids sensitivity loss at low energies; improved signal-to-noise ratios; lower detection limits | Enhanced molecular ion detection for compound confirmation; isomer differentiation |

| Liquid Electron Ionization (LEI) Interface | Nebulization and vaporization of LC effluent for EI compatibility | Provides EI structural information for LC-amenable compounds; low matrix effects | Analysis of medium-low-MW environmental pollutants and toxicological substances |

| Ionization Efficiency Prediction Models | Machine learning using molecular fingerprints or MS² neutral losses | Enables concentration estimation without analytical standards (RMSE: 0.72-0.79 logIE units) | Non-targeted analysis quantification for identified and unidentified compounds |

Experimental Methodologies for Ionization Technique Evaluation

Objective: Systematically evaluate and compare the analytical performance of different ionization sources for specific application areas.

Protocol for Sterol Analysis [15]:

- Instrumentation: Utilize an LC system (e.g., Agilent 1290 Infinity II) coupled to a mass spectrometer (e.g., Agilent 6470 LC/TQ) with interchangeable ion sources.

- Chromatography: Employ a heart-cutting 2D-LC system with a PFP column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 30 mm) in the first dimension and a C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) in the second dimension. Use a binary gradient of water and methanol/water (99/1, v/v) both with 5 mmol/L ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid.

- Ion Sources: Compare commercial ESI and APCI sources against a lab-made Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI) source.

- Performance Metrics:

- Determine limits of quantification (LOQs) using serial dilutions of sterol standards.

- Assess signal stability through extended measurement series.

- Quantify ion suppression by comparing standards in pure solvent versus spiked matrix extracts.

- Application: Analyze complex biological matrices including human plasma, HepG2 cells, and liver tissue to demonstrate real-world applicability.

Key Findings: In sterol analysis, both TPI and APCI provided comparable LOQs and clearly outperformed ESI in sensitivity. ESI suffered from pronounced ion suppression, while TPI and APCI offered stable signals during extended measurements, highlighting their robustness for complex matrix applications [15].

Optimization of Interface Design

Objective: Improve the instrumental detectability of Liquid Electron Ionization (LEI) interfaces through hardware optimization.

Protocol for LEI Interface Optimization [18]:

- Interface Setup: Test different configurations of the vaporization micro-channel (VMC) using various capillary dimensions and materials (standard silica vs. deactivated silica).

- Analysis Conditions:

- Use nanoflow rates (400-600 nL/min) compatible with UHPLC/HPLC (with flow splitting).

- Set VMC temperature to 350°C after preliminary optimization.

- Employ helium makeup gas at 1.2 mL/min.

- Analytical Measurements:

- Perform Flow Injection Analysis (FIA) with a triple-quadrupole MS operating in selected ion monitoring (SIM) or multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes.

- Conduct LC-MS analyses with a Q-TOF instrument in full-scan mode (83-600 m/z).

- Evaluation Metrics: Determine instrumental limits of detection (LODs) in triplicate for each setup configuration using representative analytes (PAHs and pesticides).

Key Findings: Optimizing the VMC setup with a deactivated silica capillary and appropriate dimensions significantly improved instrumental detectability, achieving LOD values almost five times lower than previous configurations for analytes like chlorpyrifos, atrazine, and PAHs [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Ionization Research

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Ionization Research |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge Gases | Helium (99.9999%), Argon (99.999%), Argon-Propane mixtures | Create plasma in DBDI and FμTP sources; influence ionization mechanisms and efficiency |

| LC-MS Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water (all LC-MS grade) | Dissolve and separate analytes; impact ionization efficiency in ESI, APCI, and plasma techniques |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Formic Acid, Ammonium Formate (LC-MS grade) | Enhance protonation/deprotonation in ESI and APCI; improve chromatographic separation |

| Analytical Standards | Pesticide mixes, Sterol standards (purity ≥ 98%) | Benchmark ionization performance across compound classes and determine detection limits |

| Capillary Materials | Deactivated silica, Ceramic, Stainless steel | Construct vaporization interfaces; material inertness affects analyte transport and peak shape |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Alternative Discharge Gases and Mechanism Elucidation

With declining helium reserves and operational concerns in mass spectrometer vacuum systems, research increasingly focuses on alternative discharge gases like argon and argon-propane mixtures for plasma-based ionization [17]. Early results show similar limits of quantification for nearly 90% of pesticides in positive mode when using argon-based gases compared to helium [17]. However, the fundamental ionization mechanisms with these alternative gases remain "not yet fully elucidated," particularly for argon where metastable atoms lack sufficient energy to directly ionize nitrogen [17]. Future research needs to clarify these mechanisms, especially the roles of Ar⁺ and Ar₂⁺ ions and the influence of trace gas impurities on ionization processes.

Advanced Interface Design and Miniaturization

Continued innovation in interface design aims to improve ionization efficiency and operational practicality. Research on Liquid Electron Ionization interfaces demonstrates how optimized vaporization micro-channel configurations using deactivated silica capillaries can significantly enhance detectability [18]. Simultaneously, the development of miniaturized, field-deployable ionization systems like the transverse Ion-Molecule Reaction Region (t-IMR) for chemical ionization mass spectrometry shows promise for reducing wall effects and artificial background signals while maintaining sensitivity for ambient atmospheric measurements [20]. These advancements point toward future ionization systems that offer both improved performance and greater flexibility for diverse analytical scenarios.

The evolution of ionization techniques from conventional Electron Impact to sophisticated soft ionization methods represents a continuous pursuit to expand analytical capabilities in mass spectrometry. Current research emphasizes maximizing ionization efficiency across expanding chemical spaces while minimizing matrix effects that compromise quantitative accuracy. Techniques like plasma-based ionization and advanced interface designs demonstrate significant progress toward these goals, offering broader compound coverage and more robust performance in complex matrices. Future advancements will likely emerge from deeper mechanistic understanding, refined predictive models, and innovative engineering solutions that further enhance our ability to efficiently convert diverse analyte molecules into detectable ions across the entire spectrum of mass spectrometry applications.

Ionization Techniques Classification

Ionization Efficiency Research Focus

Ionization efficiency (IE) is a cornerstone concept in mass spectrometry (MS), fundamentally governing the sensitivity, accuracy, and quantitative capabilities of the technique. It is defined as the efficiency of generating gas-phase ions from neutral analyte molecules or pre-existing ions in the ion source [21]. Within the context of a broader thesis on its role in mass spectrometry research, understanding ionization efficiency is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for developing robust methods, especially in complex fields like pharmaceutical development. The signal intensity for a given analyte is directly proportional to its ionization efficiency, which in turn is governed by a complex interplay of three core factors: the intrinsic elemental properties of the analyte, surface interactions and matrix effects during the ionization process, and the temperature of the system [1] [22] [23]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these governing factors, equipping researchers with the knowledge to optimize experimental protocols and interpret data accurately.

The Role of Elemental Properties

The innate chemical and physical characteristics of an element or molecule are the primary determinants of its ionization efficiency. These properties directly influence how readily a species can undergo ionization under a given set of conditions.

Ionization Potential and Cross-Section

A fundamental property is the ionization potential (IP), the minimum energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom or molecule. Elements with a low first ionization potential, such as the alkali metals, ionize with high efficiency, whereas elements with high ionization potentials (like noble gases) are more challenging [1]. In electron ionization (EI), the ionization cross-section is a key parameter, representing the probability that an incident electron will ionize a target atom or molecule. The maximum ionization cross-section for atoms typically occurs at electron energies between 40–60 eV [1]. For molecules, the total ionization cross-section can be roughly approximated using the additivity rule, which sums the cross-sections of constituent atoms, though this can deviate from experimental values by a factor of two or more [1].

The "W-value" in Dense Media

In condensed phases and dense gases, a crucial measure of ionization efficiency is the W-value, which is the average energy expended per electron-ion pair formed [1]. This value balances the energy used for ionization, excitation, and kinetic energy of sub-excitation electrons. The W-value is material-specific and generally decreases with increasing atomic number for noble gases, as shown in Table 1. A lower W-value indicates higher ionization efficiency, as less energy is "wasted" on non-ionizing processes [1].

Table 1: Average Energy per Electron-Ion Pair (W-value) and Ionization Potential for Noble Gases [1]

| Element | W-value (gas) [eV] | Ionization Potential (gas) [eV] | W-value (liquid) [eV] | Ionization Potential (liquid) [eV] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helium (He) | 41.3 | 24.59 | - | - |

| Neon (Ne) | 29.2 | 21.56 | - | - |

| Argon (Ar) | 26.4 | 15.76 | 23.6 | 13.4 |

| Krypton (Kr) | 24.2 | 14.00 | 18.4 | 11.55 |

| Xenon (Xe) | 22.0 | 12.13 | 9.76 | 9.22 |

Molecular Properties in Soft Ionization

For soft ionization techniques like Electrospray Ionization (ESI), molecular properties such as gas-phase basicity (for positive mode), gas-phase acidity (for negative mode), and surface activity become critically important. In ESI, ions are formed via charged droplets, and molecules with high surface activity and basicity will more effectively compete for the limited charge available at the droplet surface, leading to higher ionization efficiency [23]. The ability of a molecule to stabilize charge, for instance through protonation sites or polar functional groups, is therefore a key determinant of its response in ESI-MS.

Surface Interactions and Matrix Effects

Ionization does not occur in isolation. The local environment of the analyte, including other chemical species and surfaces, can profoundly suppress or enhance ionization efficiency, a phenomenon collectively known as the matrix effect.

The Ion Suppression Phenomenon

Ion suppression is a major form of matrix effect in techniques like LC-ESI-MS, where co-eluting matrix components interfere with the ionization of the target analyte [23]. This can lead to reduced signal intensity, poor precision, and inaccurate quantification, potentially resulting in false negatives or false positives. The mechanism is technique-dependent. In ESI, which is particularly susceptible, proposed mechanisms include:

- Competition for Charge: Co-eluting compounds compete for the limited charge available on the ESI droplet surface [23].

- Altered Droplet Properties: Matrix components can increase the viscosity or surface tension of the droplets, hindering solvent evaporation and the release of gas-phase ions [23].

- Precipitation: Non-volatile materials can coprecipitate with the analyte or prevent droplets from reaching the critical radius required for ion emission [23].

In Atmospheric-Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), ion suppression is generally less severe because the analyte is vaporized before ionization. However, it can still occur through competition for charge from the corona discharge needle or via solid formation [23].

Experimental Protocol for Detecting Ion Suppression

Two common experimental protocols are used to validate the presence and extent of ion suppression [23]:

Post-Extraction Addition Method:

- Procedure: Prepare two sets of samples. The first is a blank matrix (e.g., plasma) extracted using the intended sample preparation protocol, which is then spiked with the analyte post-extraction. The second is the analyte in pure mobile phase at the same concentration.

- Analysis: Compare the MS response (peak area or height) of the post-spiked blank matrix to the response in pure mobile phase. A significantly lower response in the matrix indicates ion suppression.

Continuous Infusion Method:

- Procedure: Continuously infuse a standard solution of the analyte into the MS via a syringe pump connected to the LC column effluent.

- Analysis: Inject a blank matrix extract into the LC system. A drop in the constant baseline signal in the chromatogram indicates the retention time windows where ion suppression is occurring, providing a spatial profile of the interference.

The Influence of Temperature

Temperature is a critical and versatile parameter that affects ionization efficiency through both fundamental thermodynamic processes and practical instrumental control.

In high-temperature ionization sources like Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) and Knudsen cell mass spectrometry, temperature directly controls the population of ions. Higher temperatures provide the thermal energy required to overcome the ionization potential of elements, particularly those with high IPs that are difficult to analyze by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) [1]. Furthermore, temperature influences the fragmentation pattern of molecules; partial ionization cross-sections depend on vibrational states, and the mass spectrum of an individual molecule can change with temperature [1].

Temperature-Controlled Electrospray Ionization (TC-ESI)

Temperature control in ESI is a powerful tool for investigating the thermodynamics and folding landscapes of biomolecules. By controlling the temperature of the spray solution, researchers can obtain a "snapshot" of a biomolecule's solution-phase structure [24]. Several specialized TC-ESI source designs exist, including:

- Cold-Spray Ionization (CSI): Operates at sub-ambient temperatures (as low as -50 °C) to stabilize non-covalent complexes and transient intermediate structures that would be disrupted at room temperature [24].

- Dual Heated-Blocks Source: Uses two temperature-controlled blocks to precisely heat the capillary and the nebulizing gas, allowing for stable operation across a wide temperature range (e.g., 20-80 °C) [24].

Heating the ESI source is also commonly used to assist droplet desolvation, which can improve ionization efficiency and signal stability, particularly for high-flow-rate applications.

Experimental Protocol for TC-ESI-MS of Biomolecular Folding

Objective: To determine the melting temperature (T~m~) and thermodynamics of a protein or oligonucleotide.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of the target biomolecule in a volatile buffer compatible with native MS (e.g., ammonium acetate).

- Temperature Ramp: Introduce the sample via the TC-ESI source and acquire mass spectra across a controlled temperature gradient (e.g., from 25 °C to 80 °C).

- Data Acquisition: For each temperature, record the mass spectrum, focusing on the charge state distribution (CSD). A compact, low-charge-state distribution is indicative of a folded structure, while an expanded, high-charge-state distribution indicates an unfolded structure.

- Data Analysis: Plot the relative abundance of a specific charge state (or the sum of folded-state charge states) versus temperature. The resulting sigmoidal curve can be fit to a thermodynamic model (e.g., a two-state unfolding model) to extract the T~m~, enthalpy (ΔH°), and free energy (ΔG°) of unfolding [24].

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

The field of ionization efficiency is being transformed by computational and instrumental advancements.

Machine Learning for IE Prediction

Predicting ionization efficiency based on molecular structure is a major goal. Machine learning (ML) models, particularly with active learning (AL) frameworks, are now being employed to predict ESI/IE with increasing accuracy [22]. These models use molecular descriptors to forecast IE, enabling the prioritization of chemicals in non-targeted screening and improving quantification accuracy when analytical standards are unavailable. A recent study showed that active learning could reduce the root mean square error (RMSE) in IE predictions by up to 0.3 log units and improve quantification fold error from 4.13× to 2.94× for natural products [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Ionization Efficiency Research

| Item | Function in IE Studies |

|---|---|

| Volatile Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) | Maintain biomolecule structure for native MS and TC-ESI without causing source contamination [24]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Minimize chemical noise and background interference, ensuring accurate IE measurement. |

| ESI Ionization Efficiency Scale Compounds | A set of reference compounds (e.g., esters, aromatic amines) with pre-defined logRIE values for instrument performance verification and cross-laboratory comparison [21]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Correct for variability in sample preparation and matrix-induced ion suppression, crucial for accurate quantification [25] [23]. |

| Appropriate Matrices for MALDI (e.g., CHCA, SA) | Absorb laser energy and facilitate soft ionization of the analyte; choice of matrix is critical for IE in MALDI [9]. |

Ionization efficiency is a multidimensional parameter central to the power and limitations of mass spectrometry. As this technical guide has detailed, IE is governed by a triad of factors: the immutable elemental properties of the analyte, the variable surface interactions and matrix effects from the sample environment, and the controllable parameter of temperature. A deep understanding of these factors allows researchers to select the appropriate ionization technique, optimize experimental conditions, develop robust quantitative methods, and correctly interpret complex data. Emerging technologies, particularly machine learning models for IE prediction and advanced temperature-controlled sources, are poised to further deepen our fundamental understanding and provide powerful new tools to tackle the next wave of analytical challenges in drug development and beyond.

Visual Summaries

Ionization Efficiency Governing Factors

Experimental Workflow for Ion Suppression Assessment

Ionization Sources in Action: Techniques and Their Efficiencies in Biomedical Analysis

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) has fundamentally redefined the capabilities of mass spectrometry (MS) by enabling the analysis of large, thermally labile biomolecules directly from liquid solutions. As a soft ionization technique, ESI efficiently produces gas-phase ions with minimal fragmentation, preserving non-covalent interactions and molecular integrity. Its unique capacity to generate multiply charged ions has extended the effective mass range of analyzers, facilitating the study of proteins, DNA, and other macromolecules. This whitepaper delves into the core mechanism of ESI, the factors governing its ionization efficiency, and its seamless compatibility with Liquid Chromatography (LC-MS), providing a technical guide framed within the broader context of ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry research. The discussion is supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualizations tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is an ionization technique that uses an electrical field to convert a liquid solution into a fine aerosol of charged droplets, ultimately leading to the formation of gas-phase ions for mass spectrometric analysis [26]. Its development, for which John B. Fenn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002, has been pivotal for the field of biomolecular analysis [27]. ESI is characterized as a "soft ionization" method because it imparts relatively little internal energy to the analyte, thereby overcoming the propensity of macromolecules like proteins to fragment upon ionization [26].

A key differentiator of ESI from other ionization processes (e.g., MALDI) is its ability to produce ions with multiple charges [26]. This multiple charging phenomenon effectively reduces the mass-to-charge ratio ((m/z)) of large biomolecules, bringing them within the detectable range of conventional mass analyzers. This has enabled the study of proteins and their associated polypeptide fragments in the kDa to MDa range [26] [28]. Furthermore, ESI allows for the retention of solution-phase information into the gas phase, making it invaluable for studying protein folding, non-covalent complexes, and other solution-state phenomena [28].

The ESI Mechanism: From Liquid Solution to Gas-Phase Ions

The mechanism of electrospray ionization is a multi-stage physical process that culminates in the release of analyte ions from a liquid phase into a gaseous phase. The process can be broken down into three distinct stages, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Stage 1: Dispersal and Droplet Formation

The process begins when a sample solution is pumped through a fine capillary or emitter needle to which a high voltage (typically 2.5–6.0 kV) is applied relative to a surrounding counter electrode [29] [27]. This strong electric field induces a charge accumulation at the liquid tip. When the electrostatic repulsion overcomes the surface tension of the liquid, it deforms into what is known as a Taylor cone, from which a fine jet of liquid erupts and disintegrates into a mist of highly charged droplets [26] [27]. The application of a nebulizing gas (e.g., nitrogen) can assist this process, enabling the use of higher sample flow rates [29].

Stage 2: Droplet Shrinking and Coulomb Fission

The charged droplets, propelled towards the mass spectrometer inlet, are exposed to a stream of heated drying gas (e.g., nitrogen) and a warm temperature in the ESI source [29] [27]. This environment promotes the rapid evaporation of the solvent. As the droplet size decreases, its charge density increases. This continues until the droplet reaches the Rayleigh limit, the point at which the electrostatic repulsion of the like charges equals the surface tension holding the droplet together [26]. At this critical point, the droplet becomes unstable and undergoes Coulomb fission, explosively discharging a portion of its mass and charge to form smaller, more stable progeny droplets [26]. This cycle of solvent evaporation and Coulomb fission repeats itself, progressively producing smaller and more highly charged droplets.

Stage 3: Production of Gas-Phase Ions

The final step is the actual release of gas-phase ions from the vastly shrunken, highly charged nanodroplets. Two primary models explain this final step, with the applicable model depending on the size and nature of the analyte:

- Charge Residue Model (CRM): This model, advocated by Dole, posits that the solvent evaporation and fission cycles continue until the droplet contains only a single analyte molecule. The charge the droplet carried is then transferred to the analyte upon final solvent evaporation [26] [28]. The CRM is generally considered the dominant mechanism for large, folded proteins [26].

- Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): Proposed by Thomson and Iribarne, this model suggests that for smaller ions, the electric field strength at the surface of a sufficiently small droplet becomes intense enough to directly desorb or "evaporate" solvated ions into the gas phase [26] [28]. The IEM is widely accepted as the mechanism for the liberation of small ions [26].

The ions observed are typically even-electron species, such as protonated [M+H]⁺ or deprotonated [M-H]⁻ molecules. For larger biomolecules, a distribution of multiply charged ions (e.g., [M+nH]ⁿ⁺) is common, creating a characteristic charge state envelope [26].

Ionization Efficiency in ESI: Factors and Quantitative Trends

Ionization efficiency is a central concept in mass spectrometry research, referring to the efficiency with which analyte molecules in solution are converted into detectable gas-phase ions. In ESI, this efficiency can vary by over a million-fold for different small molecules, profoundly impacting method sensitivity and quantitative accuracy [26]. The factors affecting ionization efficiency are multifaceted and can be categorized as relating to the analyte, the solvent, and the instrumental parameters.

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting ESI Ionization Efficiency

| Factor Category | Specific Parameter | Impact on Ionization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Properties | Surface Activity | Compounds with higher surface activity are enriched in droplet surfaces, leading to significantly higher efficiency (can be >10³ times) [30]. |

| Basicity/Acidity (in solution) | Higher gas-phase basicity (for positive mode) or acidity (for negative mode) generally favors protonation/deprotonation, increasing efficiency [30]. | |

| Molecular Size & Structure | Large biomolecules (e.g., proteins) are efficiently ionized via CRM, while efficiency for small molecules is highly structure-dependent [26] [30]. | |

| Solvent & Solution | Solvent Composition | Volatile solvents (MeOH, ACN) mixed with water enhance droplet desolvation. Protic solvents are essential for ion formation [26] [31]. |

| pH Modifiers & Buffers | Volatile additives (e.g., formic acid, acetic acid, ammonium acetate) enhance conductivity and provide a proton source. Involatile salts (e.g., phosphate) cause precipitation and severe sensitivity loss [26] [31]. | |

| Conductivity & Additives | High conductivity can influence the initial droplet formation and charge capacity. Ion-pair reagents can be used but may suppress ionization and require careful flushing [31]. | |

| Instrumental Parameters | Flow Rate | Lower flow rates (nL/min) generate smaller initial droplets, leading to vastly improved ionization efficiency and reduced sample consumption [26] [32]. |

| Applied Voltage & Electric Field | Optimizing voltage is critical for stabilizing the Taylor cone and spray mode. Excessive voltage can cause electrical discharge [33] [27]. | |

| Source Temperature & Drying Gas | Elevated temperature and drying gas flow aid solvent evaporation, improving desolvation and ion yield. Excessive heat can degrade thermally labile analytes [29] [27]. |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating Spray Modes and Efficiency

Recent research has systematically investigated how spray modes, governed by electric field and solvent supply, affect ionization efficiency. The following protocol, adapted from a 2022 study, outlines a methodology for such an investigation [33].

Aim: To characterize the different spray modes in Paper Spray Ionization (a variant of ESI) and evaluate their impact on ionization efficiency and signal stability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Mass Spectrometer: LTQ Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) or equivalent.

- Spray Substrate: Triangular papers (Whatman grade 40, 3 MM, 17) cut to isosceles triangles (30° apex, 10 mm height).

- Analytes: Test compounds such as Trimethoprim (10 μg/L) and Erythromycin (50 μg/L) in spray solvent.

- Spray Solvent: 1% formic acid in ethyl acetate (or other suitable volatile solvent).

- Equipment: Syringe pump for solvent delivery, high-voltage power supply, digital microscope (e.g., Dino-lite) for plume visualization.

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Cut the paper into specified triangles. Clean by ultrasonication in methanol and allow to dry at room temperature.

- Sample Application: Apply the sample solution containing the analytes to the paper substrate.

- Instrument Setup: Hold the paper triangle with a copper clip connected to the high-voltage supply. Position the substrate in front of the MS inlet. Connect the solvent capillary from the syringe pump to continuously deliver solvent (if applicable).

- Data Acquisition: Use the Xcalibur software (or equivalent) to acquire data in full scan or Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) mode.

- Variable Manipulation and Imaging:

- Systematically increase the applied voltage (e.g., from 1,500 to 6,250 V in 250 V increments) while keeping other parameters constant.

- Use the digital microscope to record the spray plume from a side or top view for each voltage condition.

- Simultaneously, record the mass spectrometric signal intensity and stability for the target analytes.

- Data Analysis: Correlate the observed spray mode (see Section 3.2) with the corresponding signal intensity and relative standard deviation (RSD) to determine the most efficient and stable mode.

Correlation Between Spray Modes and Efficiency

The experimental protocol above allows for the direct observation of distinct electrospray modes, which are a key determinant of efficiency. The relationship between these modes and operational parameters is complex, as shown in the following dependency graph.

The study classified the spray plume into three primary modes [33]:

- Single Cone-Jet Mode: Appears at lower applied voltages, characterized by a single jet of charged droplets.

- Multi-Jet Mode: Occurs as voltage increases, featuring multiple emission jets and a broader droplet size distribution.

- Rim-Jet Mode: Achieved at high voltages, or with low solvent flow rates and thicker substrates, this mode exhibits a spray from the rim of the tip. It demonstrated the highest ionization efficiency and the lowest signal deviation (RSD) among the three modes [33].

The main parameter determining the transition between these modes is the charge density of the generated droplets, which is a function of the electric field and the solvent supply rate [33].

LC-MS Compatibility and Method Optimization

The direct coupling of Liquid Chromatography (LC) with ESI-MS is a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry. However, achieving optimal performance requires careful consideration of mobile phase composition and LC parameters to ensure compatibility with the ESI process.

Mobile Phase Selection for ESI-MS

The core principle is to use only volatile components that can be easily evaporated and will not form precipitates that can clog the ion source or interfere with ionization [31].

Table 2: Compatible and Incompatible Mobile Phase Components for ESI-MS

| Component Type | Recommended (Volatile) | To Avoid (Involatile/Non-Compatible) | Function & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Solvents | Water, Methanol, Ethanol, Propanol, Acetonitrile* | Non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphate), Ion-pair reagents (e.g., SDS) | Acetonitrile is not recommended for APCI in negative mode [31]. |