Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, relies heavily on mass spectrometry, where the choice of ionization technique is critical for success.

Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

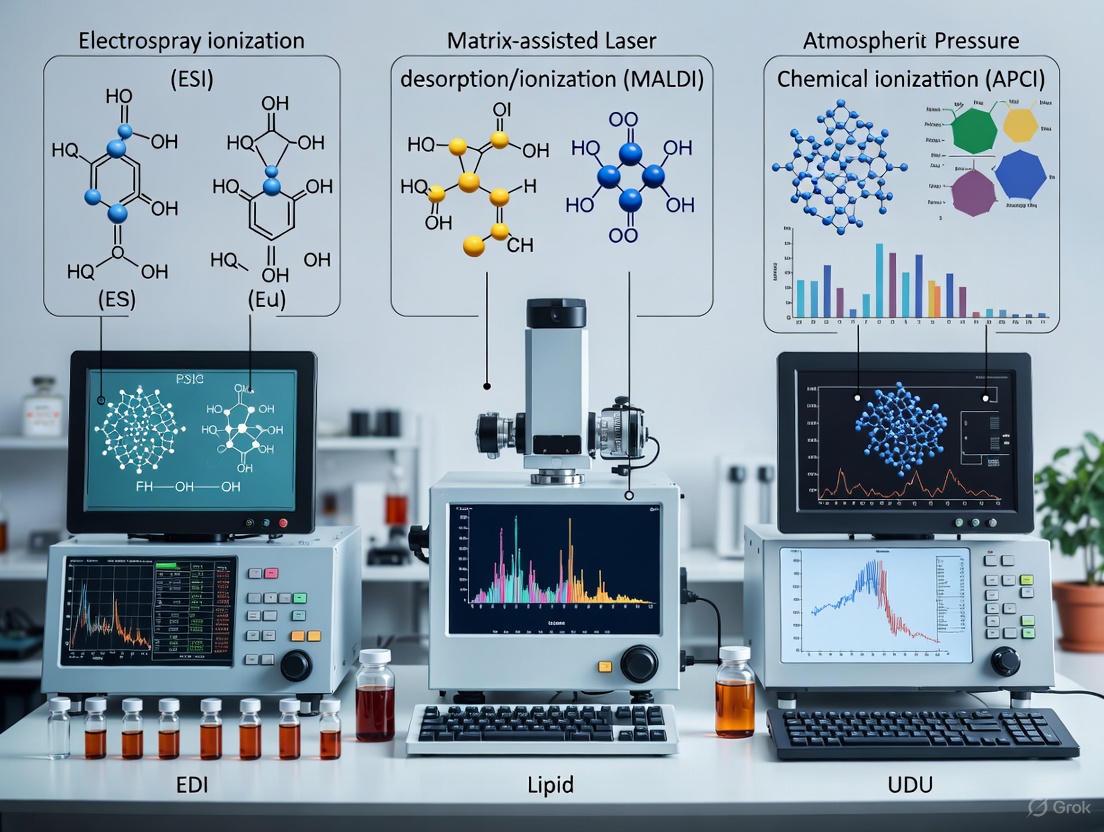

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, relies heavily on mass spectrometry, where the choice of ionization technique is critical for success. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of established and emerging ionization methods—including Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), and Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI)—for lipid analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological applications, and advanced troubleshooting. It further explores performance validation across different biological matrices, from single cells to complex tissues, offering a strategic guide to selecting the optimal ionization source for specific research goals in biomedical and clinical contexts.

Lipid Ionization Fundamentals: From Core Principles to Technique Selection

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become an indispensable tool in modern analytical chemistry, particularly in the field of lipidomics where it enables the precise identification and quantification of lipid species. The process of ionization—converting neutral analyte molecules into gas-phase ions—stands as the critical first step in any MS analysis and fundamentally dictates the type and quality of structural information obtained [1]. Ionization techniques are broadly categorized into two distinct classes based on the amount of energy transferred to the analyte molecules during the ionization process: hard ionization and soft ionization [2].

Hard ionization techniques, such as Electron Ionization (EI), impart substantial internal energy to analyte molecules during ionization. This high energy deposition typically causes extensive fragmentation of the molecular ions, generating numerous fragment ions that provide detailed structural clues for elucidating unknown compound structures [3] [1]. While this fragmentation pattern serves as a valuable fingerprint for structural determination, it often comes at the cost of significantly diminishing or completely eliminating the molecular ion signal, which is essential for determining molecular weight [2].

In contrast, soft ionization techniques, including Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), employ gentler processes that transfer minimal internal energy to the analyte molecules. These methods predominantly generate intact molecular ions with little to no fragmentation, thereby preserving information about the original molecular structure and weight—a crucial advantage when analyzing complex, fragile biomolecules like lipids [1] [2]. The fundamental differences between these approaches directly impact their applicability for lipid structural analysis, making technique selection paramount for research success.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Differentiation

Core Mechanisms and Energy Transfer

The distinction between hard and soft ionization originates from their fundamentally different mechanisms of ion formation and the consequent amount of internal energy deposited into the analyte molecules. Electron Ionization (EI), the archetypal hard ionization method, operates by bombarding vaporized analyte molecules with a high-energy beam of electrons (typically 70 eV) emitted from a heated filament [3] [1]. This interaction causes the ejection of an electron from the analyte molecule, generating a radical cation (M⁺•). The substantial energy transferred during this process—far exceeding the vibrational energy thresholds of chemical bonds—results in significant fragmentation as the excited molecular ions relax, producing a complex spectrum of fragment ions [2].

Conversely, soft ionization techniques like Electrospray Ionization (ESI) operate through a completely different mechanism. In ESI, a sample solution is sprayed through a charged capillary needle to form fine, charged droplets at atmospheric pressure. As the solvent evaporates with the assistance of heated gas, the droplets undergo Coulombic fission until they eventually release gas-phase, often multiply charged, analyte ions [1] [2]. This "desolvation" process is remarkably gentle, preserving the structural integrity of even large, non-volatile biomolecules. Similarly, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) protects analyte molecules by embedding them in a light-absorbing matrix compound. When irradiated with a pulsed laser, the matrix absorbs the energy and facilitates the gentle desorption and ionization of the intact analyte molecules into the gas phase with minimal fragmentation [1].

Comparative Analysis of Ionization Techniques

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Hard vs. Soft Ionization Techniques

| Feature | Hard Ionization (e.g., EI) | Soft Ionization (e.g., ESI, MALDI) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Input | High (e.g., 70 eV electrons) | Low (e.g., desolvation, laser with matrix) |

| Typical Fragmentation | Extensive, in the ion source | Minimal to none in the ion source |

| Molecular Ion Signal | Often weak or absent | Strong and predominant |

| Primary Information Obtained | Detailed structural fingerprints via fragments | Molecular weight & intact ion information |

| Ionization Environment | High vacuum | Atmospheric pressure (ESI) or vacuum (MALDI) |

| Typical Mass Analyzers | Often paired with quadrupole, ToF | Versatile (Orbitrap, FT-ICR, ToF, ion traps) |

Table 2: Suitability of Different Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis

| Ionization Technique | Ionization Type | Lipid Classes Effectively Analyzed | Key Advantages for Lipidomics | Major Limitations for Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Ionization (EI) | Hard | Small, volatile lipids; Fatty acid methyl esters | Reproducible spectral libraries; Rich structural data | Unsuitable for most intact lipids; extensive fragmentation |

| Chemical Ionization (CI) | Soft | Moderately stable, volatile lipids | Stronger molecular ion than EI; molecular weight info | Limited to volatile samples; less reproducible |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Soft | Polar & non-polar lipids; phospholipids, sphingolipids | Excellent for polar lipids; produces multiply charged ions; high sensitivity | Susceptible to matrix effects; requires clean samples |

| APCI | Soft | Semi-volatile lipids; cholesterol, triglycerides | Good for less polar lipids; tolerant of buffers | Requires thermal stability; not for large/fragile lipids |

| APPI | Soft | Non-polar lipids (e.g., steroids, PAHs) | Effective for non-polar compounds resistant to ESI/APCI | Low efficiency for polar compounds |

| MALDI | Soft | Broad range; phospholipids, glycolipids | Spatial mapping via MSI; singly charged ions simplify spectra | Quantitative challenges; matrix interference |

The choice between these ionization methods fundamentally shapes the analytical workflow. EI's extensive fragmentation provides a wealth of structural information valuable for identifying unknown small molecules, but this comes at the cost of the molecular ion, which is essential for determining the molecular weight of unknown compounds [2]. The reproducibility of EI spectra has allowed for the creation of extensive mass spectral libraries, enabling compound identification through database matching [3]. However, for the analysis of intact lipids and other large biomolecules, the soft ionization techniques are overwhelmingly superior. ESI and MALDI generate predominantly intact molecular ions, making them ideal for molecular weight determination and the analysis of complex mixtures, as they produce less complex spectra [1]. ESI's ability to generate multiply charged ions allows for the analysis of high molecular weight compounds using mass analyzers with limited m/z ranges [2].

Impact on Lipid Structural Integrity: Analytical Consequences

Fragmentation Patterns and Information Yield

The differential impact of hard versus soft ionization on lipid structural integrity directly dictates the type of analytical information researchers can obtain. Under the harsh conditions of Electron Ionization (EI), lipid molecules undergo extensive and often non-specific fragmentation. While this generates a multitude of fragment ions, the molecular ion—which reports the intact mass of the lipid—is frequently absent or very weak [2]. This makes it challenging or impossible to determine the molecular weight of an unknown lipid. The fragmentation pattern, while reproducible and useful for library matching, can be overly complex for analyzing intricate lipid mixtures without prior separation [3].

In contrast, soft ionization techniques are renowned for their ability to preserve lipid structural integrity. ESI typically produces ions such as [M+H]⁺, [M+Na]⁺, or [M-H]⁻, providing a direct measurement of the lipid's molecular weight with minimal in-source fragmentation [2]. This preservation of the intact molecule is paramount for lipidomics, as it allows researchers to determine the exact lipid species present before subjecting them to targeted fragmentation in tandem MS (MS/MS) experiments for detailed structural elucidation [4]. This two-step approach—first obtaining an intact mass spectrum and then selectively fragmenting specific ions of interest—has become the cornerstone of modern lipidomics.

Implications for Lipidomics Workflows

The gentle nature of soft ionization has unlocked the ability to study lipids in their native states and within their biological contexts. For instance, MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MALDI-MSI) allows for the spatial mapping of lipid distributions directly in biological tissues, such as in the model organism C. elegans, revealing how specific lipids are localized to different anatomical structures like the pharynx, intestine, and embryos [5]. This capability to correlate molecular information with anatomy is only possible because MALDI preserves the intact lipid ions during the desorption/ionization process.

Furthermore, the advent of single-cell lipidomics is heavily reliant on the sensitivity and gentleness of soft ionization techniques. Using ultra-sensitive mass spectrometers like Orbitrap and FT-ICR, researchers can now profile the lipidomes of individual cells, capturing real-time metabolic changes and revealing cellular heterogeneity that is completely obscured in bulk analyses [4] [6]. This application demands that the ionization process not only be soft but also exceptionally sensitive, as the amount of material available from a single cell is vanishingly small.

Experimental Protocols for Lipid Analysis

Protocol for Lipid Profiling Using ESI-MS/MS

This protocol is widely used for the comprehensive identification and quantification of lipids from complex biological extracts.

- Sample Preparation: Extract lipids from biological matrices (e.g., plasma, tissue, cells) using a validated method like Bligh & Dyer or Matyash. Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent mixture (e.g., chloroform:methanol, 1:2 v/v) containing a small amount of volatile ammonium salt (e.g., ammonium formate or acetate) to promote ion formation.

- LC Separation (Optional but Recommended): Utilize reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) with a C18 column for lipid separation prior to MS analysis. A typical mobile phase consists of (A) water:acetonitrile (40:60) and (B) isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10), both with 10 mM ammonium formate. Employ a gradient elution (e.g., 0-100% B over 20-30 minutes) to separate different lipid classes based on their hydrophobicity [3].

- ESI-Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Ion Source Parameters: Set the electrospray voltage to 3.5-4.5 kV (positive mode) or 2.8-3.5 kV (negative mode). Use a desolvation temperature of 200-300°C and a nebulizing gas flow (nitrogen) to optimize spray stability and desolvation.

- Data Acquisition: First, acquire a full MS scan (e.g., m/z 200-2000) using a high-resolution mass analyzer (Orbitrap or FT-ICR) to detect the intact lipid ions and determine their accurate masses. This provides the molecular formula information for the lipids present [4].

- Tandem MS (MS/MS): Select precursor ions of interest from the full MS scan and fragment them using techniques such as Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) or Higher-Energy C Collisional Dissociation (HCD). The resulting MS/MS spectra provide structural details on the lipid headgroup and fatty acyl chains, enabling definitive identification [3].

Protocol for Spatial Lipidomics Using MALDI-MSI

This protocol enables the visualization of lipid distribution within tissue sections.

- Tissue Preparation and Sectioning: Flash-freeze fresh tissue samples in liquid nitrogen to preserve lipid composition and spatial integrity. Cryosection the tissue into thin slices (5-20 µm thickness) and thaw-mount them onto conductive indium tin oxide (ITO) glass slides or standard glass slides for MALDI-MSI.

- Matrix Application: Select an appropriate matrix for lipid analysis, such as 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) or 9-aminoacridine (9-AA). Apply the matrix uniformly onto the tissue section using a automated sprayer or sublimation device to ensure a homogeneous, fine crystalline layer. This matrix is crucial for absorbing the laser energy and facilitating the soft desorption/ionization of lipids [5] [1].

- MALDI-MSI Data Acquisition:

- Load the prepared slide into the MALDI mass spectrometer.

- Define an ablation raster pattern across the tissue section with a specified spatial resolution (e.g., 10-100 µm, depending on the required detail and sensitivity).

- The instrument will automatically move the stage, firing the laser (typically a 337 nm nitrogen laser) at each pre-defined position. For each pixel, a full mass spectrum is acquired.

- Data Processing and Image Reconstruction: Using specialized software, reconstruct the spatial distribution of any ion of interest by plotting its signal intensity against its X,Y coordinate on the tissue section. This generates ion images that visually represent the localization of specific lipids, which can be overlaid with post-imaging histological stains for anatomical correlation [5].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipid MS Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform & Methanol | Primary solvents for lipid extraction from tissues/cells | Used in Bligh & Dyer and Folch extraction methods |

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate | Volatile salt additives for LC mobile phases; promotes [M+H]+/[M+NH4]+ ion formation in ESI | Improving ionization efficiency and chromatographic separation in LC-ESI-MS |

| DHB (2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid) | A common MALDI matrix for lipid analysis in positive ion mode | Detecting phospholipids like phosphatidylcholines in tissue imaging |

| 9-Aminoacridine (9-AA) | A common MALDI matrix for lipid analysis in negative ion mode | Detecting acidic phospholipids like phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylserine |

| C18 LC Columns | Stationary phase for reversed-phase chromatographic separation of lipids by hydrophobicity | Separating complex lipid mixtures prior to ESI-MS analysis |

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | Key component of Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for mRNA delivery; studied for reactivity | Model compounds for studying lipid-mRNA adduct formation and stability [7] |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | Component of embedding media for cryosectioning of small organisms | Preserving anatomical structure of C. elegans for MALDI-MSI [5] |

Visualizing Ionization Workflows and Lipid Integrity Outcomes

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows of hard and soft ionization and their dramatically different impacts on lipid structural integrity and the resulting mass spectral data.

Diagram: Workflow comparison of hard versus soft ionization and their impact on lipid analysis.

The fundamental dichotomy between hard and soft ionization techniques presents a clear strategic choice for researchers in lipid analysis. Hard ionization (EI) offers powerful structural elucidation capabilities for small, volatile molecules through extensive fragmentation, but it is fundamentally incompatible with the analysis of intact, complex lipids due to the destructive nature of its high-energy process. In contrast, soft ionization techniques (ESI, MALDI, APCI, APPI) have become the undisputed cornerstone of modern lipidomics. Their ability to gently generate intact molecular ions enables the accurate determination of molecular weights, making them indispensable for profiling the vast diversity of lipid species in biological systems.

The selection of the appropriate soft ionization method must be guided by the specific research question. ESI excels in sensitivity and compatibility with LC separation for polar lipids, MALDI enables groundbreaking spatial mapping of lipids within tissues, while APCI/APPI effectively handle less polar lipid classes. As the field advances toward single-cell analysis and spatial omics, the continued refinement of these soft ionization sources—focusing on increased sensitivity, spatial resolution, and quantitative robustness—will be crucial for uncovering new insights into the roles of lipids in health and disease.

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that has revolutionized the analysis of biomolecules, particularly in the field of lipidomics and pharmaceutical research. This technique enables the transfer of ions from solution to the gas phase through the application of a high voltage to a liquid, creating an aerosol of charged droplets [8]. ESI is fundamentally different from other ionization processes because of its unique ability to generate multiply charged ions, effectively extending the mass range of mass analyzers to accommodate the kiloDalton to megaDalton molecular weight range observed in proteins, peptides, and other macromolecules [8].

The development of ESI for the analysis of biological macromolecules was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002, awarded to John Bennett Fenn and Koichi Tanaka [8]. Since its introduction, ESI has become an indispensable tool in clinical laboratories and research settings, providing a sensitive, robust, and reliable method for studying non-volatile and thermally labile biomolecules at femtomole quantities in microliter sample volumes [9]. The capability of ESI to retain solution-phase information into the gas-phase and its compatibility with separation techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) have made it particularly valuable for analyzing complex biological samples [9] [8].

Fundamental Principles of ESI

The Electrospray Process Mechanism

The ESI process involves the application of electrical energy to assist the transfer of ions from solution into the gaseous phase before they are subjected to mass spectrometric analysis [9]. This process occurs through three distinct stages, each critical to the successful generation of gas-phase ions:

- Droplet Formation: A sample solution is dispersed through a capillary tube maintained at a high voltage (typically 2.5–6.0 kV) relative to the surrounding chamber wall, generating a fine mist of highly charged droplets with the same polarity as the capillary voltage [9]. The application of a nebulizing gas (e.g., nitrogen) shears the eluted sample solution, enabling higher sample flow rates [9].

- Desolvation: The charged droplets pass down a pressure and potential gradient toward the analyzer region of the mass spectrometer [9]. With the aid of an elevated ESI-source temperature and/or a stream of nitrogen drying gas, the charged droplets continuously decrease in size through solvent evaporation [9]. This leads to an increase in surface charge density and a decrease in droplet radius until the electric field strength within the charged droplet reaches a critical point known as the Rayleigh limit [9] [8].

- Gas Phase Ion Formation: When the Rayleigh limit is reached, the electrostatic repulsion of like charges becomes more powerful than the surface tension holding the droplet together, resulting in Coulomb fission where the original droplet explodes, creating many smaller, more stable droplets [8]. These smaller droplets undergo further desolvation and subsequent Coulomb fissions until gas-phase ions are produced [9] [8].

Two major theories explain the final production of gas-phase ions: the Charge Residue Model (CRM) and the Ion Evaporation Model (IEM). The CRM suggests that electrospray droplets undergo repeated evaporation and fission cycles until progeny droplets contain approximately one analyte ion or less, with gas-phase ions forming after remaining solvent molecules evaporate [8]. The IEM proposes that as droplets reach a critical radius, the field strength at the droplet surface becomes sufficient to assist the field desorption of solvated ions directly into the gas phase [8] [10]. Current evidence indicates that small ions from small molecules are liberated through the ion evaporation mechanism, while larger ions from folded proteins form by the charged residue mechanism [8].

Generation of Multiply Charged Ions

A defining characteristic of ESI is its ability to produce multiply charged ions, which is particularly beneficial for analyzing macromolecules [8]. The multiple charging phenomenon occurs because the ionization process in ESI involves the addition of protons (in positive ion mode) or removal of protons (in negative ion mode), rather than the removal of electrons as in some other ionization techniques [8].

In ESI, the ions observed by mass spectrometry may be quasimolecular ions created by:

- Addition of a hydrogen cation, denoted as [M + H]⁺

- Addition of another cation such as sodium ion, [M + Na]⁺

- Removal of a hydrogen nucleus, [M - H]⁻

- Multiply charged ions such as [M + nH]ⁿ⁺, where n represents the number of charges [8]

For large macromolecules, there can be many charge states, resulting in a characteristic charge state envelope where a single molecular species appears as a series of peaks in the mass spectrum, each representing the molecule with a different number of charges [8]. This multiple charging effect effectively extends the mass range of mass analyzers because the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) is reduced to a range that can be detected by most mass spectrometers [10]. For example, a 50 kDa protein with 50 charges would appear at approximately m/z 1000 in the mass spectrum, well within the range of most commercial instruments [8] [10].

The multiple charging phenomenon provides significant advantages for structural analysis through tandem mass spectrometry because multiply charged ions are more easily fragmented, increasing collision activation sensitivity and providing more structural information [10]. Additionally, the presence of multiple charge states enables more accurate molecular weight determination through deconvolution algorithms that analyze the charge state distribution [10].

ESI in Lipid Analysis: Experimental Considerations

Sample Preparation and Modification

Lipid analysis via ESI-MS requires careful consideration of sample preparation to enhance ionization efficiency and detection sensitivity. The choice of solvents and additives significantly impacts the quality of mass spectrometric data.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for ESI-MS Lipid Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Salts (Lithium chloride, lithium acetate) | Forms [M+Li]⁺ adducts; stabilizes pseudo-molecular ions; enhances sensitivity for certain lipid classes [11]. | Analysis of sterol esters (SE), triacylglycerols (TG), acylated steryl glucosides (ASG); improves detection of monoacylglycerols (MG) and lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) [11]. |

| Chloroform-Methanol Mixtures | Lipid extraction from biological samples; preparation of samples for direct infusion (shotgun lipidomics) [12]. | Global lipid analyses directly from crude extracts of biological samples [12]. |

| Acids/Bases | Promotes protonation (acids in ESI+) or deprotonation (bases in ESI-) of molecules [13]. | Enhancement of signal for specific lipid classes based on their inherent polarity and ionizability. |

| Post-column Addition Solvent | Introduces compatible solvent and cationizing agent (e.g., LiCl) in NPLC-ESI-MS to overcome mobile phase incompatibility [11]. | Comprehensive lipid analysis using normal-phase liquid chromatography; enables coupling of NPLC with ESI-MS [11]. |

A notable advancement in lipid analysis is the use of lithium adduct consolidation. Lithium cations interact with amide and ester functional groups of lipids, displacing other alkali metal adducts to form predominantly [M+Li]⁺ ions, thereby increasing sensitivity [11]. This approach has been successfully implemented in normal-phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) coupled with ESI-MS using a post-column addition of 0.10 mM lithium chloride in a methanol-chloroform mixture (90:10, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.10 mL/min, significantly improving the detection of specific lipid classes that are challenging to analyze with conventional APCI methods [11].

Experimental Protocols for Lipid Analysis

Protocol 1: NPLC-ESI-MS with Post-column Lithium Addition

This protocol enables comprehensive lipid class separation and detection, particularly beneficial for sterol esters, triacylglycerols, and acylated steryl glucosides [11].

- Sample Preparation: Extract lipids using appropriate chloroform-methanol mixtures. Prepare samples in NPLC-compatible solvents [11].

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Column: Normal-phase column (e.g., silica-based)

- Mobile Phase: Gradients of isooctane, ethyl acetate, acetone, and chloroform-methanol-water mixtures with acidic or basic modifiers as needed

- Flow Rate: Optimized for specific column dimensions (typically 0.1-0.5 mL/min) [11]

- Post-column Addition:

- Solution: 0.10 mM lithium chloride in methanol-chloroform (90:10, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 0.10 mL/min

- Mixing: Use a low-dead-volume T-connector to mix column effluent with lithium-containing solution before introduction to ESI source [11]

- ESI-MS Parameters:

- Ionization Mode: Positive ion mode

- Capillary Voltage: 3.0-4.5 kV (optimize for specific instrument)

- Drying Gas: Temperature 180-250°C, flow rate 2-4 L/min

- Nebulizer Gas Pressure: 1-2 bar

- Mass Analyzer: FT-ICR, Orbitrap, or quadrupole-based instrument for detection of [M+Li]⁺ adducts [11]

Protocol 2: Shotgun Lipidomics by Direct Infusion

This approach involves direct introduction of lipid extracts into the mass spectrometer without chromatographic separation, enabling high-throughput analysis [12].

- Lipid Extraction: Use modified Folch or Bligh-Dyer methods with chloroform-methanol (2:1, v/v) for total lipid extraction from biological samples [12].

- Sample Preparation:

- Redissolve dried lipid extracts in chloroform-methanol (1:2, v/v)

- Centrifuge to remove insoluble material

- Dilute to appropriate concentration (typically 10⁻⁶-10⁻⁴ M) for ESI-MS analysis [12]

- Direct Infusion:

- Flow Rate: 1-10 µL/min (conventional ESI); 0.1-1 µL/min (nano-ESI)

- Use syringe pump for stable flow rate [12]

- ESI-MS Parameters:

- Ionization Mode: Positive or negative ion mode, depending on lipid classes of interest

- Capillary Voltage: Optimize for specific lipid classes (typically 2.5-4.0 kV)

- Source Temperature: 100-250°C

- Collision Energy: Optimized for precursor ion scanning or neutral loss scanning in tandem MS experiments [12]

Comparison of ESI with Alternative Ionization Techniques

Technical Comparison of Ionization Methods

ESI offers distinct advantages and limitations compared to other common ionization techniques used in lipid analysis. The following table summarizes key performance characteristics based on current research applications.

Table 2: Comparison of ESI with Alternative Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis

| Ionization Technique | Mechanism | Advantages for Lipid Analysis | Limitations for Lipid Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Electrical energy transfers ions from solution to gaseous phase via charged droplet formation [9] [8]. | Soft ionization (minimal fragmentation); generates multiply charged ions; suitable for thermally labile compounds; compatible with liquid chromatography; excellent for polar lipids [9] [12] [11]. | Suppression effects in complex mixtures; sensitive to contaminants and buffer composition; lower efficiency for non-polar lipids without adduct formation [11] [10]. |

| Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) | Gas-phase chemical ionization at atmospheric pressure using corona discharge [12] [11]. | More tolerant to non-polar solvents and buffer salts; better for less polar lipids (e.g., sterol esters, triacylglycerols); provides structural information through in-source fragmentation [12] [11]. | Not as soft as ESI (more in-source fragmentation); may degrade labile compounds; less effective for large, polar lipids; poorer response for lysophospholipids [11]. |

| Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI) | Gas-phase ionization using photon energy from UV lamp [11]. | Efficient for non-polar compounds; extends analyte range beyond APCI; less susceptible to ion suppression than ESI [11]. | Requires dopants for certain compounds; may produce complex spectra with both M⁺⁺ and [M+H]⁺ ions; limited application for polar lipids [11]. |

| Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) | Laser desorption/ionization of sample embedded in light-absorbing matrix [12]. | High throughput; suitable for imaging mass spectrometry; minimal sample preparation required; excellent for spatial distribution studies [12]. | Matrix interference in low mass range; inhomogeneous crystallization affects quantitation; limited compatibility with on-line separation techniques [12]. |

Performance Data in Lipid Analysis

Experimental comparisons between ESI and APCI for lipid analysis reveal technique-specific performance characteristics. A recent study comparing NPLC-ESI-MS with post-column lithium addition to NPLC-APCI-MS demonstrated significant improvements for specific lipid classes [11]:

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of ESI vs. APCI Performance for Lipid Classes

| Lipid Class | Relative Response Factor (APCI = 1.0) | Detection Limitations with APCI | Improvement with ESI-Lithium Adduct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterol Esters (SE) | 2.5-3.5 | In-source fragmentation produces mainly [sterol nucleus+H-H₂O]⁺ ions, obscuring molecular species information [11]. | Enhanced detection of intact [M+Li]⁺ molecular ions enables identification of individual molecular species [11]. |

| Triacylglycerols (TG) | 1.8-2.5 | In-source fragmentation varies with unsaturation; saturated TGs show weak or no [M+H]⁺ ions [11]. | Consistent detection of [M+Li]⁺ adducts across saturation levels; improved quantification accuracy [11]. |

| Monoacylglycerols (MG) | 4.0-5.0 | Weak response in APCI; difficult to detect at low concentrations [11]. | Significant sensitivity enhancement; reliable detection and quantification [11]. |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) | 3.5-4.5 | Difficult to observe with increased mobile phase polarity at end of chromatographic run [11]. | Markedly improved detection with post-column lithium addition in ESI mode [11]. |

The data indicate that ESI with lithium adduct formation provides substantial advantages for analyzing lipid classes that are challenging for APCI, particularly sterol esters, triacylglycerols, monoacylglycerols, and lysophospholipids [11]. The implementation of post-column addition strategies has overcome previous limitations in coupling normal-phase chromatography with ESI-MS, enabling comprehensive lipid analysis that leverages the strengths of both separation and ionization techniques [11].

Advanced ESI Methodologies and Applications

Micro- and Nano-ESI Techniques

Significant advancements in ESI technology have led to the development of micro- and nano-electrospray ionization, which operate at substantially lower flow rates than conventional ESI [8]. Nano-ESI utilizes flow rates in the range of 20-100 nL/min, compared to conventional ESI which typically operates at 1-1000 μL/min [8]. This reduction in flow rate generates much smaller initial droplets (approximately 200 nm diameter compared to 1-2 μm for conventional ESI), resulting in improved ionization efficiency, reduced sample consumption, and lower detection limits [8] [14].

The enhanced performance of nano-ESI stems from more efficient desolvation and ion formation from smaller droplets, leading to reduced chemical background and improved signal-to-noise ratios [14]. These characteristics make nano-ESI particularly valuable for analyzing limited samples, such as in single-cell lipidomics or when working with precious clinical specimens [14]. The technique has proven especially beneficial in proteomics for low-abundance biomolecule detection and in lipidomics for comprehensive analysis of complex cellular lipidomes where sample amounts may be limited [14].

ESI in Structural Lipidomics

Beyond quantitative analysis, ESI-MS provides powerful capabilities for structural characterization of lipids through tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [9] [12]. The multiple charging phenomenon in ESI enhances structural analysis because multiply charged ions fragment more efficiently in collision-induced dissociation (CID) processes, providing more detailed structural information [12] [10].

Key applications of ESI-MS/MS in structural lipidomics include:

- Head Group Determination: Product ion scanning identifies characteristic fragment ions that define lipid classes (e.g., m/z 184 for phosphatidylcholines) [12].

- Fatty Acyl Chain Analysis: Precursor ion scanning and neutral loss scanning identify lipid species based on common fatty acyl fragments or neutral losses [9] [12].

- Double Bond Localization: Advanced tandem MS techniques, including ozone-induced dissociation and ultraviolet photodissociation, pinpoint double bond positions in unsaturated lipid chains [12].

- Spatial Isomer Differentiation: MS³ experiments in ion trap instruments distinguish sn-positional isomers of glycerophospholipids [9].

These structural analysis capabilities make ESI-MS an indispensable tool for elucidating lipid metabolic pathways, characterizing novel lipid structures, and understanding lipid function in membrane dynamics and cellular signaling [12].

Electrospray Ionization has established itself as a cornerstone technique in modern mass spectrometry, particularly for lipid analysis in biomedical research and drug development. Its unique capacity to generate multiply charged ions has extended the accessible mass range for biomolecular analysis while maintaining the structural integrity of fragile lipid species. The fundamental three-step process—droplet formation, desolvation, and gas-phase ion generation—enables efficient transfer of analytes from solution to the gas phase, making it ideally suited for coupling with liquid-phase separation techniques.

The comparison with alternative ionization methods reveals that ESI offers distinct advantages for comprehensive lipid profiling, particularly when enhanced with lithium adduction strategies that address previous limitations with non-polar lipid classes. While APCI and APPI demonstrate superior performance for certain non-polar lipids, ESI's soft ionization characteristics, compatibility with physiological buffers, and ability to provide structural information through tandem MS make it the technique of choice for most lipidomic applications. As ESI technology continues to evolve with nanoflow applications, ambient ionization techniques, and improved interface designs, its role in advancing lipid research and accelerating drug development remains unquestionably vital.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) represents a cornerstone soft ionization technique in mass spectrometry that enables the analysis of large, non-volatile molecules with minimal fragmentation. This technology has revolutionized the analysis of biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, peptides, and carbohydrates, by allowing their ionization and detection in intact form. The fundamental MALDI process involves three critical steps: first, the sample is mixed with a suitable energy-absorbing matrix material and applied to a metal plate; second, a pulsed laser irradiates the sample, triggering ablation and desorption of the sample and matrix material; finally, analyte molecules are ionized through protonation or deprotonation in the hot plume of ablated gases before being accelerated into the mass analyzer [15].

The development of MALDI imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI IMS) has further expanded its capabilities by combining the sensitivity and selectivity of mass spectrometry with spatial analysis, providing unprecedented ability to visualize the spatial arrangement of biomolecules directly in tissue sections [16]. This spatial dimension has transformed MALDI from a mere analytical tool to a powerful imaging technology that preserves molecular context, enabling researchers to investigate lipid distributions in biological systems with high molecular specificity. For lipid analysis research, MALDI offers particular advantages in detecting a wide range of lipid classes with high sensitivity while maintaining spatial information that is lost in conventional extraction-based approaches.

Comparison of Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis

The landscape of ionization techniques for lipid analysis encompasses several complementary technologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations. When evaluating MALDI against competing ionization methods, researchers must consider multiple performance parameters including sensitivity, spatial resolution, molecular coverage, and analytical throughput.

Table 1: Comparison of Ionization Techniques for Lipid Analysis

| Technique | Mechanism | Spatial Capabilities | Key Advantages for Lipid Analysis | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization using UV or IR laser | Yes (5-20 μm resolution) | Minimal fragmentation; imaging capability; broad lipid coverage; high sensitivity | Matrix interference in low mass range; requires crystallization; semi-quantitative |

| ESI | Electrospray creates charged droplets that evaporate | No (requires liquid introduction) | Excellent sensitivity; hyphenation with LC; good quantitation; produces multiply charged ions | Ion suppression effects; requires clean samples; no direct spatial information |

| Ambient Ionization MS | Direct ionization at atmospheric pressure (DESI, LAESI) | Yes (50-200 μm resolution) | Minimal sample prep; in situ analysis; true ambient operation | Lower spatial resolution; limited sensitivity for some lipid classes |

| CE-MS | Separation by electrophoretic mobility coupled to MS | No | High separation efficiency; minimal sample volume; complementary to LC methods | Limited loading capacity; specialized interfaces required |

MALDI demonstrates particular strengths for spatially resolved lipid analysis where maintaining the tissue context is essential. Unlike electrospray ionization (ESI), which requires sample extraction and liquid introduction, MALDI enables direct analysis from tissue sections, preserving crucial spatial information about lipid distributions [16] [17]. Compared to ambient ionization techniques like desorption electrospray ionization (DESI), MALDI typically provides superior spatial resolution (down to 5-10 μm with optimized protocols) and higher sensitivity for many lipid classes, though it requires more extensive sample preparation including matrix application [16].

The coupling of MALDI with time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers has proven particularly effective for lipid analysis due to the large mass range, high sensitivity, and pulsed operation mode that matches well with the MALDI ionization process [15]. Recent advancements in MALDI-FT-ICR and MALDI-TIMS platforms have further enhanced mass resolution and isomer separation capabilities, addressing previous limitations in distinguishing structurally similar lipid species [18].

Experimental Protocols for MALDI Lipid Analysis

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful MALDI-based lipid analysis, with protocols varying significantly depending on the sample type and analytical goals. For lipid analysis from biological tissues, the standard workflow begins with tissue collection and preservation, typically through snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen to maintain lipid integrity and spatial distribution. Tissue sections are then prepared using a cryostat at thicknesses ranging from 5-20 μm and thaw-mounted onto indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass slides, which enable both MS analysis and subsequent histological staining [17].

A key consideration is the avoidance of optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound as an embedding medium, as it causes significant ion suppression and interferes with lipid detection [17]. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, deparaffinization with xylene followed by rehydration through graded ethanol baths is required, though fresh frozen tissues are generally preferred for lipid analysis to avoid potential lipid loss during processing [17].

The application of an appropriate matrix is perhaps the most critical step in MALDI sample preparation. For lipid analysis, the matrix solution typically consists of crystallized molecules with strong optical absorption at the laser wavelength, such as 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) at 10 mg/mL in chloroform:methanol (9:1) for negative ion mode lipid analysis, or α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) for positive ion mode analyses [19] [15]. The matrix serves multiple functions: it absorbs the laser energy, facilitates desorption and ionization of lipid molecules, and prevents analyte fragmentation through energy dissipation.

Matrix application can be performed using several methods, each with distinct advantages. Spraying matrix solution through an automated sprayer provides good extraction efficiency and spatial resolution of 10-20 μm, though care must be taken to prevent analyte delocalization from excessive wetting. Sublimation followed by recrystallization offers excellent spatial resolution with minimal delocalization but may yield lower sensitivity for some lipid classes. For high-throughput applications, robotic spotting enables excellent analyte extraction but sacrifices spatial resolution (typically 200 μm) [16].

Lipid-Specific MALDI Protocols

Specialized MALDI protocols have been developed to address the unique challenges of lipid analysis. For direct analysis of intact mycobacteria, researchers have established a streamlined protocol that leverages the abundant lipids in the bacterial cell wall for identification. This method involves heat inactivation of cultured mycobacteria at 95°C for 30 minutes, washing with double-distilled water, and direct spotting of the bacterial suspension onto the MALDI target followed by addition of a specialized matrix consisting of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid and 2-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid (super-DHB) in chloroform:methanol (9:1) [19]. This approach detects species-specific lipid patterns including sulphoglycolipids specific to Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and glycopeptidolipids found in non-tuberculous mycobacteria, achieving 96.7% sensitivity and 91.7% specificity for identification with analysis completed in under 10 minutes [19].

For enhanced structural characterization of lipids, derivatization strategies can be incorporated into the MALDI workflow. The Paternò-Büchi (PB) reaction, ozone-induced dissociation (OzID), and epoxidation reactions have been successfully coupled with MALDI to determine carbon-carbon double bond positions and sn-position isomers in complex lipid samples [20]. These approaches significantly expand the structural information obtainable from MALDI-based lipid analysis beyond simple lipid class identification.

Research Reagent Solutions for MALDI Lipid Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MALDI Lipid Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI Matrices | DHB, CHCA, SA, super-DHB | Absorb laser energy, facilitate desorption/ionization | DHB: broad lipid coverage; CHCA: positive mode lipids; super-DHB: mycobacterial lipids |

| Solvents | Chloroform, methanol, acetonitrile, ethanol | Sample preparation, matrix dissolution, washing | Chloroform:methanol (9:1) for lipid extraction; ACN:water:TFA for matrix |

| Tissue Supports | ITO-coated glass slides, standard glass slides | Sample mounting for imaging | ITO enables optical microscopy and conductive surface for MS |

| Calibration Standards | PEG mixtures, lipid standards | Mass axis calibration | Critical for accurate mass determination in MS imaging |

| Washing Solutions | Ethanol, Carnoy's fluid, ammonium formate | Remove salts, contaminants, improve sensitivity | Carnoy's fluid (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid) for tissue |

| Derivatization Reagents | PB reagents, ozone, epoxidation catalysts | Enhance structural information | Determine C=C locations, sn-positions |

Advanced Applications in Lipid Research

Spatial Lipidomics in Biomedical Research

MALDI imaging mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful tool for spatial lipidomics, enabling the investigation of lipid distributions in diverse biomedical contexts. In neurological research, MALDI IMS has identified ganglioside accumulation in amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer's disease and revealed lipid alterations associated with schizophrenia [17]. A particularly compelling application involves the analysis of spinal cord lesions in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model of multiple sclerosis, where MALDI IMS identified upregulation of inflammation-related ceramide-1-phosphate and ceramide phosphatidylethanolamine as markers of white matter lipid remodeling [18].

In oncology, MALDI IMS has proven invaluable for characterizing lipid changes in the tumor microenvironment. Researchers have employed this technology to identify extracellular matrix collagen peptides that differentiate non-invasive ductal carcinoma in situ from invasive breast cancer, and to detect N-glycan and protein alterations in the extracellular matrix as predictors of prostate cancer progression [17]. The ability to visualize lipid distributions without prior labeling makes MALDI IMS particularly suited for discovery-phase studies where the molecular targets are not yet known.

Clinical and Pharmacological Applications

The clinical utility of MALDI-based lipid analysis continues to expand, particularly in microbiology and pharmacology. For mycobacterial identification, the lipid-focused MALDI approach has demonstrated exceptional performance, correctly identifying 96.7% of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains (204/211) and 91.7% of non-tuberculous mycobacterial species (22/24) based on species-specific lipid profiling [19]. This methodology provides significant advantages over protein-based identification methods by reducing biosafety concerns through heat inactivation and minimizing sample preparation steps.

In pharmacology, MALDI IMS has been employed to investigate drug distribution and metabolism at the tissue level. A 2024 study visualized the accumulation of the hypnotic drug zolpidem in the middle of a single hair shaft following ingestion, contrasting with the outer layer distribution observed after external contamination [17]. Similarly, researchers have tracked the permeation of berberine through epidermis and dermis layers following transdermal delivery using microneedle arrays, demonstrating the utility of MALDI IMS for evaluating drug delivery strategies [17].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The analytical performance of MALDI-based lipid analysis has been rigorously evaluated across multiple studies, providing quantitative data for comparison with alternative techniques. In mycobacterial identification, the lipid-based MALDI approach demonstrated 96.7% sensitivity (204/211 correct identifications) and 91.7% specificity (22/24 correct identifications) compared to molecular identification methods [19]. This performance was achieved with remarkable speed (<10 minutes analysis time) and high sensitivity (<1000 bacteria required), significantly outperforming conventional culture-based identification methods that typically require days to weeks.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics for MALDI Lipid Analysis

| Application Context | Sensitivity | Specificity | Analysis Time | Key Lipids Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterial Identification [19] | 96.7% (204/211) | 91.7% (22/24) | <10 minutes | Sulphoglycolipids, glycopeptidolipids, polyacyltrehaloses |

| Spatial Lipidomics (EAE Model) [18] | N/A | N/A | ~7 hours (175,000 pixels) | Ceramide-1-phosphate, ceramide phosphatidylethanolamine |

| Drug Distribution (Zolpidem) [17] | N/A | N/A | ~2-4 hours | Parent drug and metabolites (m/z 395.1495) |

| Plant Lipid Imaging [17] | N/A | N/A | Variable by size | Various bioactive compounds and metabolites |

Spatial resolution represents another critical performance parameter for MALDI imaging applications. Current commercial MALDI IMS instruments achieve spatial resolutions of approximately 20 μm in microprobe mode, with advanced approaches like oversampling and beam modification enabling resolutions down to 5 μm [16]. However, higher spatial resolution comes with trade-offs in sensitivity, analysis time, and data storage requirements, necessitating careful optimization based on the specific biological question.

The integration of MALDI with ion mobility separation has significantly enhanced lipid identification confidence by providing collision cross-section (CCS) values as an additional molecular descriptor. In a groundbreaking 2025 study, researchers combined quantum cascade laser mid-infrared imaging with MALDI-TIMS-MS to elucidate 157 sulfatides accumulating in kidneys of arylsulfatase A-deficient mice, providing unprecedented structural characterization of complex lipid mixtures in tissue [18]. This multi-dimensional approach addresses a key limitation of conventional MALDI analysis by adding a separation dimension that helps distinguish isobaric lipid species.

The evolution of MALDI technology continues to address current limitations while expanding application boundaries. Ongoing developments in instrumental design focus on improving the mutually exclusive criteria in the "4S-paradigm" of MSI performance: speed, sensitivity, spatial resolution, and molecular specificity [18]. The integration of guided acquisition approaches, such as quantum cascade laser mid-infrared imaging microscopy, enables intelligent targeting of specific tissue regions, preserving instrument time for in-depth analysis of biologically relevant areas [18].

For lipid analysis specifically, the combination of MALDI with advanced structural elucidation techniques represents a promising direction. Derivatization strategies including the Paternò-Büchi reaction and ozone-induced dissociation are being adapted to MALDI platforms to enable confident determination of double bond positions and stereochemistry directly from tissue sections [20]. Additionally, the ongoing expansion and refinement of lipid databases coupled with improved computational tools for data analysis are addressing current challenges in lipid identification and quantification.

In conclusion, MALDI mass spectrometry provides a uniquely powerful platform for lipid analysis that balances analytical performance with spatial information preservation. While the technique demonstrates clear advantages in applications requiring spatial context, researchers must consider its limitations in quantitative accuracy and the need for careful method optimization. The continuing innovation in MALDI technology, coupled with its integration with complementary analytical approaches, ensures its ongoing transformation and expanding utility in lipid research across biomedical, pharmaceutical, and clinical domains.

Lipidomics, the large-scale analysis of cellular lipids, presents significant analytical challenges due to the immense structural diversity and dynamic concentration ranges of lipid molecules. A persistent hurdle in this field has been the efficient ionization and detection of less polar lipids, which constitute crucial components of biological systems. These lipids, including triacylglycerols (TAGs), sterols, and fatty acid esters, play essential roles as cellular membrane constituents, energy storage depots, and signaling molecules. Unlike their polar counterparts, they lack easily ionizable functional groups, making them notoriously difficult to analyze using conventional ionization methods like electrospray ionization (ESI). Within this context, atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) and atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) have emerged as powerful techniques that significantly extend the range of successfully analyzable lipids.

This guide provides an objective comparison of APCI and APPI mass spectrometry for analyzing less polar lipids. We will examine their fundamental ionization mechanisms, compare their performance through published experimental data, detail standard methodologies, and discuss their respective advantages within the broader landscape of lipidomics research, providing drug development professionals and researchers with a clear framework for technique selection.

Fundamental Principles and Ionization Mechanisms

Understanding the distinct ionization mechanisms of APCI and APPI is crucial for explaining their performance differences with less polar lipids. Both are gas-phase ionization techniques but operate on fundamentally different principles.

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) relies on gas-phase ion-molecule reactions initiated by a corona discharge needle that applies a high voltage (typically 3-5 kV) to create a reactive plasma [21]. This plasma contains energetic species (e.g., hydroxyl radicals, atomic oxygen) that first ionize the solvent and gas molecules (e.g., N₂, H₂O) present in the source. These primary ions then undergo a series of proton transfer or charge exchange reactions with analyte molecules. For less polar lipids, this typically results in the formation of protonated [M+H]⁺ or deprotonated [M-H]⁻ molecules, and sometimes radical cations M⁺• [22]. The efficiency of this process depends on the relative proton affinities of the reactant ions and the analyte, making it susceptible to ion suppression when compounds with higher proton affinity compete for the available charge [23].

Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI) uses high-energy photons from a krypton lamp (emitting at 10.0 and 10.6 eV) to ionize molecules [24]. In the direct APPI mechanism, a photon is absorbed by an analyte molecule (M), leading to the ejection of an electron and formation of a radical cation (M⁺•). This radical cation can be detected directly or can react with a solvent molecule (S) to form a protonated molecule ([M+H]⁺). A key advantage is that this process is less prone to charge competition than APCI, as photons interact with any molecule in their path regardless of the presence of other compounds with lower ionization potentials [23]. In dopant-assisted APPI, a photoionizable compound like toluene or acetone is added to create a high concentration of charge carriers, which then ionize the analyte through charge or proton transfer.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and typical ions generated for less polar lipids in positive ion mode.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Applications

Direct comparative studies reveal distinct performance characteristics for APCI and APPI when applied to various classes of less polar lipids. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature, highlighting differences in sensitivity, linear dynamic range, and observed ions.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of APCI and APPI for Less Polar Lipid Analysis

| Lipid Class / Analytic | Ionization Technique | Reported Performance Metrics & Observed Ions | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triacylglycerols (TAGs), Diacylglycerols (DAGs), Free Fatty Acids [25] [26] | APPI | • Sensitivity: 2-4x higher than APCI• Linear Dynamic Range: 4-5 decades• Primary Ions: [M+H]⁺, M⁺• | Superior sensitivity and wide linear range for major nonpolar lipid classes, especially with normal-phase solvents. |

| APCI | • Linear Dynamic Range: 4-5 decades• Primary Ions: [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻ | Robust and reliable, but lower signal intensity compared to APPI for these analytes. | |

| Squalene (Triterpene) [24] | APPI | • Primary Ion: Intense [M+H]⁺ (m/z 411.4)• M⁺• not observed | Efficiently ionizes this nonpolar hydrocarbon, which is poorly ionizable by ESI. Mechanism involves proton transfer after solvent photoionization. |

| APCI | • Primary Ion: [M+H]⁺ | Successfully ionizes unsaturated hydrocarbon lipids but can cause fragmentation. | |

| Cholesterol & Steroids [27] | APPI | • Primary Ions: [M+H-H₂O]⁺, M⁺• | Provides intact molecular species information with less in-source fragmentation than APCI. |

| APCI | • Result: Extensive fragmentation• Note: Cholesterol produces no stable [M+H]⁺ | Causes extensive dehydration and fragmentation for cholesterol and many steroids, complicating analysis. | |

| Saturated Hydrocarbons (e.g., 5α-Cholestane) [27] | APPI/APCI | • APCI/ESI: Cannot ionize saturated hydrocarbon 5α-cholestane• Note: Requires specialized CI reagents (e.g., ClMn(H₂O)⁺) for analysis | Highlights a key limitation of standard APCI/APPI for very nonpolar, saturated hydrocarbons. |

Beyond the quantitative metrics, each technique has distinct application strengths. APPI demonstrates particular efficacy for a wide range of apolar compounds, from triterpenes like squalene to triacylglycerols [24]. Its major advantage is the reduced susceptibility to ion suppression effects from biological matrices, as the initial ionization event (photon absorption) is not a competitive process [23]. APCI, while sometimes less sensitive, is a robust and widely available platform. It is particularly useful for less polar lipids that are still amenable to gas-phase proton transfer, such as free fatty acids and diacylglycerols [22] [21]. However, a noted limitation of APCI is the potential for in-source oxidation reactions due to reactive oxygen species in the corona discharge plasma, which can generate [M+O]⁺ ions and complicate spectra [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, this section outlines standard experimental protocols for analyzing less polar lipids using both APCI and APPI, as derived from the cited literature.

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful lipidomic analysis. The following workflow is commonly employed for tissue or biological fluid samples:

- Extraction: Use a modified Bligh & Dyer or MTBE (methyl tert-butyl ether) method for comprehensive lipid extraction [28]. For example, the MTBE method uses a solvent ratio of MTBE/methanol/water (5:1.5:1.45, v/v/v), which separates lipids into the top MTBE layer, facilitating easy collection and reducing water-soluble contaminant carry-over.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add appropriate internal standards (e.g., deuterated or odd-chain lipid analogs) to the sample prior to extraction. This corrects for variability in recovery and ionization efficiency, enabling accurate quantification [28].

- Reconstitution: After evaporating the organic solvent under a gentle nitrogen stream, reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent. For APCI and APPI, a 50:50 mixture of dichloromethane (DCM) and methanol is often effective, or isopropanol for normal-phase LC-MS applications [22] [24]. Typical concentrations for infusion are 0.1-0.5 mg/mL.

Instrumental Configuration and Parameters

The table below compiles typical source parameters for APCI and APPI analyses, optimized for less polar lipids.

Table 2: Typical Instrument Parameters for APCI and APPI Analysis of Lipids

| Parameter | APCI Typical Setting | APPI Typical Setting | Notes and Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaporizer Temperature | 400 - 450 °C [22] | 325 - 450 °C [26] [24] | Ensures complete vaporization of the LC eluent or infused sample. |

| Discharge Current/Voltage | 3.35 kV, 5 μA [22] | N/A | APCI-specific; creates corona discharge plasma. |

| Lamp Photon Energy | N/A | 10.0 / 10.6 eV (Kr lamp) [24] | APPI-specific; photon energy must exceed analyte ionization potential. |

| Capillary Temperature | 275 °C [22] | 350 °C [24] | Temperature of the transfer capillary into the mass spectrometer. |

| Sheath/Auxiliary Gas | 35 (arb.) [22] | 50 (arb.) [24] | Nitrogen is common; assists nebulization and desolvation. |

| Dopant | Not Used | Toluene or Acetone [24] [23] | In dopant-assisted APPI, added via post-column infusion (e.g., 50 μL/min) to enhance ionization. |

| Mobile Phase | Reversed-phase or Normal-phase | Normal-phase preferred (e.g., Hexane, IPA) [26] [24] | Normal-phase solvents (low IP) enhance APPI sensitivity by acting as efficient dopants. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for APCI/APPI Lipid Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform, Methanol, MTBE | Lipid extraction from biological matrices (e.g., Folch, Bligh & Dyer, MTBE methods) [28]. | HPLC or LC-MS grade. |

| Deuterated Lipid Internal Standards | Quantification and quality control; corrects for extraction recovery and ionization variability. | e.g., d₇-Cholesterol, d₅-Triacylglycerol [28]. |

| Toluene or Acetone | Dopant for APPI; increases ionization efficiency of analytes, especially with high-IP mobile phases [24] [23]. | HPLC grade, ≥99.9% purity. |

| n-Hexane, Isooctane, Isopropyl Alcohol | Normal-phase LC solvents for APPI; low ionization potential allows them to act as proton donors [26] [23]. | HPLC grade. |

| Krypton Discharge Lamp | Photon source for APPI; emits 10.0 and 10.6 eV photons [24]. | Standard component in commercial APPI sources. |

| Nitrogen Gas | Sheath, auxiliary, and desolvation gas for the ion source. | High-purity (≥99.995%) generator or liquid nitrogen source. |

The overall workflow from sample to data acquisition is summarized in the following diagram.

Both APCI and APPI are indispensable tools in the lipid analyst's arsenal, effectively addressing the critical challenge of ionizing less polar lipids. APCI offers a robust and widely accessible platform, suitable for a range of low to moderately polar lipids like fatty acids and diacylglycerols. In contrast, APPI consistently demonstrates superior sensitivity for the most apolar lipid classes, including triacylglycerols, sterols, and hydrocarbons like squalene, while also being less susceptible to ion suppression.

The choice between these techniques is not merely a matter of sensitivity but also depends on the specific lipid classes of interest, the available instrumentation, and the chromatographic conditions. For comprehensive lipidomic profiling that includes a wide range of nonpolar species, APPI holds a distinct advantage. However, for many routine applications targeting specific, moderately nonpolar lipids, APCI remains a highly effective and reliable choice. Ultimately, the integration of either technique into LC-MS workflows has significantly broadened the observable lipidome, enabling deeper insights into the roles of lipids in health, disease, and drug action.

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipidomes, faces significant analytical challenges due to the immense structural and physicochemical diversity of lipid species, which range from highly polar oxylipins to strongly hydrophobic triglycerides [29]. The critical step of ionizing lipids for mass spectrometric analysis profoundly influences the sensitivity, coverage, and accuracy of results. For years, Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) have dominated lipid analysis. ESI is renowned for its capability to ionize a wide range of compounds, while APCI demonstrates particular efficacy for moderately polar to nonpolar lipids [30]. However, these techniques have limitations, including susceptibility to ion suppression (ESI) and lower efficiency for polar compounds (APCI) [30] [31]. Recent years have witnessed the emergence of alternative ionization techniques designed to overcome these hurdles. Among these, Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI) has surfaced as a promising plasma-based technology that promises sensitive ionization across a wide polarity range, indicating its potential utility for sterol analysis and broader lipidomics applications [30]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of TPI against established ionization techniques, providing experimental data to inform researchers and method developers in their selection process.

Technique Comparison: TPI vs. ESI vs. APCI

A direct performance comparison of these three ionization techniques was conducted using a standardized setup for the analysis of sterols, a challenging lipid class due to vast concentration differences and significant matrix interference [30]. The following table summarizes the key experimental findings.

Table 1: Performance comparison of ESI, APCI, and TPI for sterol analysis based on experimental data [30].

| Feature | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) | Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Mechanism | Ion evaporation from charged droplets | Gas-phase ion-molecule reactions via corona discharge | Dielectric barrier discharge-based non-equilibrium plasma |

| Suitable Polarity Range | Polar compounds [30] | Moderate to low polarity compounds [30] | Wide polarity range [30] |

| Sensitivity (LOQ) | Higher (underperformed) | Comparable to TPI | Comparable to APCI |

| Signal Stability | Unstable (pronounced ion suppression) | Stable | Stable |

| Ion Suppression | Pronounced | Not pronounced | Not pronounced |

| Performance in Complex Matrices | Suffered from pronounced ion suppression in plasma, HepG2 cells, and liver tissue | Robust, provided reliable quantification | Robust, results in close agreement with APCI |

| Key Advantage | Easy operation; efficient for a wide range of polar compounds | Efficient for non-polar lipids; stable signal | Wide polarity range; stable signal; low ion suppression |

The experimental data reveal that both TPI and APCI clearly outperformed ESI in terms of sensitivity for sterol analysis, with comparable Limits of Quantification (LOQs) between them [30]. A critical differentiator was signal stability during extended measurements: while both TPI and APCI provided stable signals, ESI suffered from pronounced ion suppression [30]. When applied to complex biological matrices like human plasma, HepG2 cells, and liver tissue, TPI provided results in close agreement with APCI, highlighting its robustness for accurate sterol quantification in real-world samples [30].

Experimental Protocol: A Closer Look at the Data

The comparative data presented above were generated using a rigorous and detailed methodology, which is essential for understanding the context of the results.

Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Chromatographic separation was performed using a heart-cutting 2D-LC system [30]. The first dimension utilized a Kinetex PFP column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 30 mm), while an InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) was used in the second dimension [30]. The mobile phase consisted of water (eluent A) and methanol/water with 5 mmol/L ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid (eluent B) in both dimensions [30]. The analysis was coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

Ion Source Parameters and Comparison

The lab-made TPI source was developed for LC-MS coupling and compared directly with commercial ESI and APCI sources [30]. The characterization was performed according to the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, and ion suppression as well as signal stability were thoroughly examined [30]. The study demonstrated that the plasma-based TPI source could be effectively coupled with LC-MS and achieved performance metrics on par with or superior to established techniques for specific applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured lipid analysis experiments, which are fundamental for replicating the workflow.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for lipid extraction and analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Avanti Polar Lipids Standards | Sterol and lipid internal standards for quantification | Cholest-5-en-3β-ol (cholesterol), lanosterol, desmosterol, etc. [30] |

| Chloroform | Organic solvent for biphasic lipid extraction (Folch, Bligh & Dyer) | Used in conventional Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods [32] [29] |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Less toxic alternative to chloroform for biphasic lipid extraction | Used in MTBE-based extraction protocol [33] |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Polar solvent for protein precipitation and lipid extraction | Component of Folch, Bligh & Dyer, and monophasic extractions [32] [29] |

| Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) | Greener alternative solvent for chloroform-free lipid extraction | Showed comparable/superior performance to Folch protocol [29] |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive in LC-MS to improve ionization | Used at 5 mmol/L in the mobile phase for sterol analysis [30] |

| C18 Reverse-Phase Column | Core separation tool for complex lipid mixtures | InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC-C18 [30] |

Integrated Workflow in Modern Lipidomics

A modern, sensitive lipidomics workflow integrates several advanced technologies, from sample preparation to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the key steps involved when utilizing emerging techniques like TPI or TIMS-PASEF.

Diagram 1: Comprehensive lipidomics workflow with emerging techniques.

This workflow highlights where ionization sources like TPI, ESI, and APCI operate within a broader analytical context. Furthermore, the integration of additional separation dimensions, such as Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS), is becoming increasingly important. TIMS separates ions based on their shape and size (collisional cross section, CCS), providing an opportunity to resolve otherwise unresolved isomeric lipids [33]. When coupled with parallel accumulation–serial fragmentation (PASEF), this technology can significantly increase the number of identified lipids from minimal sample amounts, achieving attomole sensitivity [33].

The expansion of the analytical toolbox in lipidomics is vital for addressing the complex challenges of comprehensive lipid analysis. While ESI and APCI remain robust and well-characterized workhorses, emerging techniques like Tube Plasma Ionization (TPI) offer compelling advantages, particularly for specific analyte classes like sterols and in situations where ion suppression hampers ESI performance. Experimental evidence demonstrates that TPI provides sensitivity comparable to APCI and superior to ESI for sterols, with excellent signal stability and minimal ion suppression in complex matrices [30]. The choice of ionization technique must be guided by the specific lipids of interest, the complexity of the sample matrix, and the required sensitivity. As the field progresses, the combination of improved ionization sources with advanced separation technologies like ion mobility will undoubtedly push the boundaries of what is possible in lipidomics.

Targeted Lipidomics in Practice: Matching Ionization Techniques to Analytical Goals

Spatial lipidomics aims to characterize the diverse landscape of lipids within their native tissue context, providing crucial insights into cellular function, organization, and disease mechanisms. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has emerged as a powerful analytical technology that enables simultaneous, label-free detection and spatial localization of hundreds of lipids directly from biological tissues. Among the various MSI techniques, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) have become the most commonly used ionization methods for spatial metabolomics and lipidomics [34] [35]. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations in spatial resolution, sensitivity, molecular coverage, and sample preparation requirements, making them suitable for different research applications in lipid analysis.

The first MSI technology, SIMS, emerged in 1967 and was initially used for imaging elements and small organic molecules. MALDI technology, developed in 1987, represented a significant breakthrough by enabling measurement of proteins with molecular weights greater than 10 kDa, paving the way for biomolecule detection. In 1997, the integration of MALDI with MSI for imaging small molecules, peptides, and proteins in biological tissues marked the beginning of a new era in spatial molecular analysis [35]. Since then, continuous technological advancements have expanded MSI applications, establishing it as one of the most powerful analytical methods available today. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these MSI techniques, with particular emphasis on MALDI-MSI applications in spatial lipidomics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Technical Comparison of MSI Ionization Techniques

MALDI-MSI (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization)

Fundamental Principles and Workflow: MALDI-MSI operates through a coordinated process where a UV-absorbing matrix is applied to tissue sections to extract and co-crystallize with lipids. When irradiated by a pulsed UV laser (typically at 337 nm or 355 nm), the matrix absorbs most of the laser energy, becoming excited or evaporating into the gas phase and carrying the analytes into the mass spectrometer for detection. The process primarily relies on gas-phase proton transfer between the analyte and matrix molecules [35]. The matrix deposition step is critical, as it governs crystal size and homogeneity, which directly impacts analytical repeatability, sensitivity, spatial resolution, and ultimately the quality of MALDI MS ion images [34].

Spatial Resolution and Performance: MALDI-MSI achieves spatial resolutions of approximately 10 μm, with the lowest reported at around 1.4 μm, providing a favorable balance between sample preparation complexity, chemical specificity, sensitivity, and spatial resolution [34]. Recent advancements in transmission geometry MALDI (t-MALDI) and laser postionization (MALDI-2) have enabled pixel sizes ≤ 1 × 1 μm², allowing subcellular investigation [36]. Commercial MALDI sources mostly use reflection geometry ion sources where the laser beam irradiates the sample surface with an angle between 1° and 90° [34].

Ionization Efficiency and Lipid Coverage: The soft ionization characteristics of MALDI make it particularly suitable for lipid analysis, generating primarily single-charged ions with minimal fragmentation, which simplifies spectral interpretation [37]. MALDI-2 postionization significantly enhances sensitivity for a wide range of lipid classes [36]. The technique can visualize hundreds of lipid species simultaneously, including glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and glycerolipids, across a mass range typically between m/z 400-1200 [38].

DESI-MSI (Desorption Electrospray Ionization)

Fundamental Principles and Workflow: DESI-MSI is an ambient ionization technique that operates at atmospheric pressure without requiring matrix application or vacuum conditions. The mechanism involves an electrospray solvent, under the influence of nebulizer gas and voltage, forming a charged spray that sweeps across the sample surface at a specific angle. When the solvent contacts the surface, it rapidly dissolves analytes and forms charged droplets that are directed into the mass spectrometer for detection. This "droplet picking" mechanism enables true in situ analysis with minimal sample preparation [35].

Spatial Resolution and Performance: DESI-MSI typically achieves spatial resolution in the range of 50-200 μm, making it suitable for imaging larger tissue areas rather than cellular-level resolution. Recent advancements using nanospray DESI MSI (nano-DESI MSI) have improved spatial resolution to approximately 11 μm, though most current applications still operate in the 50-200 μm range due to limitations in spray focus, solvent composition, capillary size, and gas flow rate [34]. Air flow-assisted DESI (AFADESI) MSI has achieved very high metabolite coverage with enhanced sensitivity but suffers from poor spatial resolution around 100 μm [34].