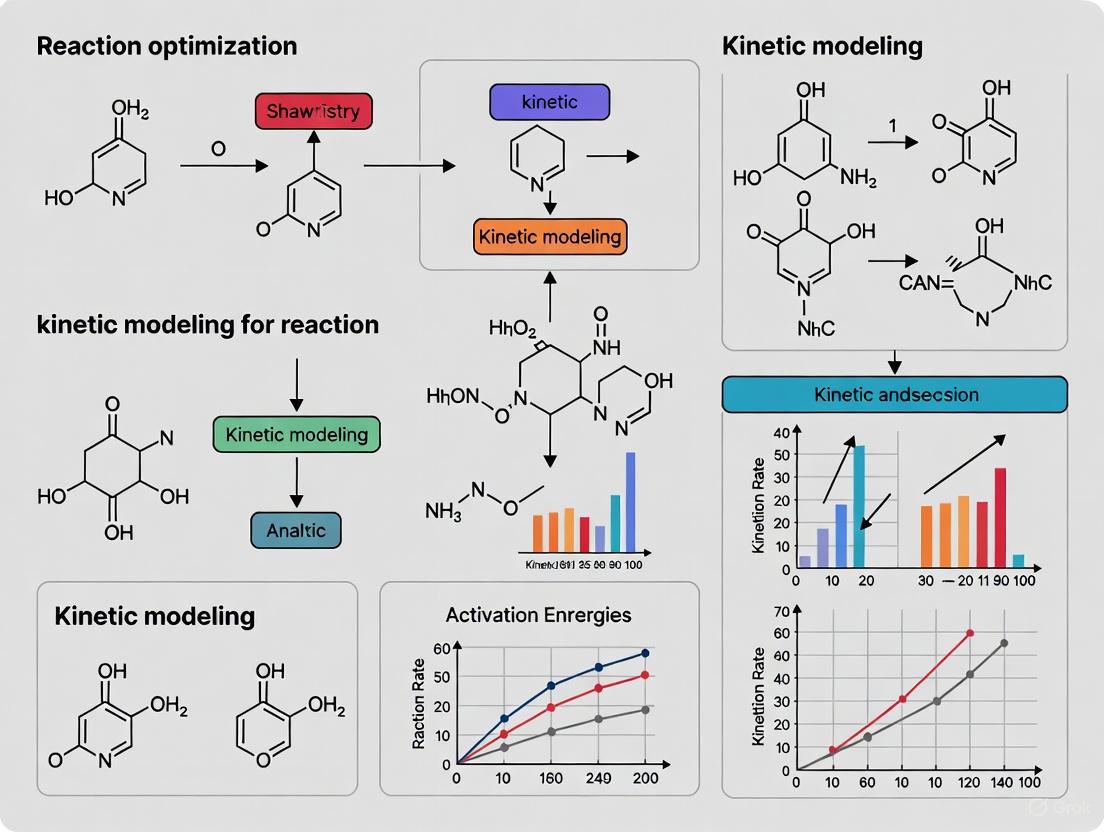

Kinetic Modeling for Reaction Optimization: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to kinetic modeling for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Kinetic Modeling for Reaction Optimization: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to kinetic modeling for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of chemical kinetics and their pivotal role in the molecule-based management of modern processes. The content delves into a variety of methodological approaches, from first-order models to complex machine learning applications, for optimizing reactions and predicting stability. It further offers practical strategies for troubleshooting common parameter estimation challenges and compares the performance of different optimization algorithms. Finally, the article outlines robust frameworks for model validation and discusses the integration of these approaches into regulatory and clinical decision-making, highlighting their impact on accelerating biomedical research.

The Core Principles of Kinetic Modeling: A Foundation for Molecule-Based Management

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is molecule-based management in chemical processes? Molecule-based management is an advanced paradigm in chemical engineering that aims to track and predict the behavior of each individual molecule from raw feedstock to final product. This approach leverages growing computational capabilities and large datasets to build detailed kinetic models, often involving hundreds of species and thousands of reactions, for fundamental understanding and optimization of industrial processes [1].

Why is detailed feedstock composition crucial for accurate kinetic modeling? Knowledge of detailed molecular feedstock composition is essential because feedstocks like crude oil or biomass can consist of thousands of different compounds. Accurate molecular reconstruction enables smart estimation of feed composition based on easily measurable global properties, which is a key enabling technology for molecule-based management. Without this, predicting how a particular feed will react is impossible [1].

What are the main challenges with traditional kinetic models? Traditional kinetic models often suffer from limitations in accuracy, narrow applicability ranges, and difficulty handling complex reaction conditions. They can be tedious and error-prone to handle manually when they expand to contain thousands of reactions, and their validity is often limited to the specific conditions under which they were developed [1] [2].

How can unstable molecular structures affect high-throughput computational screening? In automated chemical compound space explorations, a significant challenge is ensuring that minimum energy geometries preserve intended bonding connectivities. Unstable molecules can undergo unintended structural rearrangements during quantum mechanical geometry optimization, leading to results that don't correspond to the intended Lewis structures. This necessitates robust, iterative workflows for connectivity-preserving geometry optimizations [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inaccurate Kinetic Models for Complex Reactions

Symptoms: Poor prediction of reaction outcomes, narrow applicability range, inability to handle varying conditions.

Solution: Implement a data-driven recursive kinetic modeling approach with multiple estimation strategy.

Experimental Protocol:

- Establish recursive relationships between concentrations of reactants or products at different time points

- Apply multiple estimation strategies to predict chemical reaction kinetics

- Validate model on simulated datasets including 18 chemical reaction types

- Test applicability on real-world reactions with complex kinetics

- Compare performance against traditional concentration-time equation models [2]

Expected Outcome: Superior accuracy, broader application scope, improved robustness, and few-shot learning capability compared to traditional models.

Problem 2: Unintended Molecular Rearrangements in Computational Studies

Symptoms: DFT-level geometries not aligning with intended Lewis structures, molecular connectivity changes during optimization.

Solution: Implement the ConnGO (Connectivity Preserving Geometry Optimizations) workflow.

Experimental Protocol:

- Tier 1: Generate initial 3D coordinates from SMILES and relax with MMFF94 force field using steepest descent minimizer (energy convergence threshold: 10⁻⁸ kcal mol⁻¹)

- Tier 2: Further relax geometries using Hartree-Fock method with minimal basis set

- Evaluation: Check for connectivity conservation using Maximum Absolute Deviation (MaxAD) and Mean Percentage Absolute Deviation (MPAD) of bond lengths

- Tier 3: For failures, use B3LYP/3-21G starting with tier-1 geometries

- Tier 4: Final optimization with target DFT-level (B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p))

- Verification: Confirm local minima through vibrational analysis at each tier [3]

Troubleshooting Metrics:

| Metric | Calculation | Pass Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| MaxAD | Maximum absolute deviation of bond lengths | <0.2 Å |

| MPAD | Mean percentage absolute deviation of bond lengths | <5% |

Problem 3: Identifying Relevant Reaction Pathways in Complex Systems

Symptoms: Difficulty detecting short-lived intermediate species, challenges deciphering networks of chemical reactions.

Solution: Apply Deep Learning Reaction Network (DLRN) framework for kinetic modeling of time-resolved data.

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare 2D time-resolved datasets (e.g., wavelength vs. time)

- Process through DLRN's Inception-ResNet architecture

- Model block analyzes 2D signal to identify most probable kinetic model from 102 possibilities

- Time and amplitude blocks extrapolate time constants and species-associated amplitudes

- Validate predictions against ground truth data [4]

Performance Metrics:

| Analysis Type | Accuracy | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Model Prediction | 83.1% | Top 1 match |

| Model Prediction | 98.0% | Top 3 match |

| Time Constants | 80.8% | Area metric >0.9 |

| Time Constants | 95.2% | Area metric >0.8 |

| Amplitude Prediction | 81.4% | Area metric >0.8 |

Key Challenges in Molecule-Based Management

| Challenge | Impact | Current Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Complexity | Thousands of compounds in crude oil/biomass | Molecular reconstruction from global properties [1] |

| Reaction Network Size | Up to 10,000+ reactions; manual handling impossible | Automated reaction mechanism generation [1] |

| Parameter Accuracy | Model performance sensitivity | Global optimization algorithms for calibration [5] |

| Model Applicability | Limited to calibration conditions | Data-driven recursive modeling with few-shot learning [2] |

| Molecular Stability | Unintended structural rearrangements | Iterative connectivity-preserving workflows [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive 2D GC Analytical Techniques | Detailed molecular composition analysis | Feedstock characterization for molecular reconstruction [1] |

| Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (STA) | Kinetic characterization under varying conditions | Thermochemical Energy Storage material evaluation [5] |

| Global Optimization Algorithms (e.g., SCE) | Direct calibration of reaction models | Parameter estimation from time-series data [5] |

| Smart Molecular Positioners | Precise final control element adjustment | Addressing valve stiction in process control loops [6] |

| Inception-ResNet Architecture | Deep learning-based kinetic analysis | Automated kinetic model extraction from time-resolved data [4] |

Workflow Visualization

Molecule-Based Management Workflow

Connectivity-Preserving Geometry Optimization

DLRN Kinetic Analysis Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the kinetic triplet and why is it important for reaction optimization? The kinetic triplet consists of the activation energy (E~a~), the pre-exponential factor (A), and the reaction model (f(α)). It provides a complete mathematical description of reaction kinetics, allowing researchers to predict reaction rates and optimize conditions for industrial processes and drug development. The triplets are typically determined by analyzing data from multiple heating rates using model-free or model-fitting approaches. [7]

2. My isoconversional analysis shows the activation energy changes with conversion. What does this mean? A significant variation of E~a~ with conversion (α) indicates a multi-step process. If the difference between maximum and minimum E~a~ values across α = 0.1–0.9 is more than 10–20% of the average E~a~, the reaction cannot be accurately represented by a single reaction model. In such cases, you should use computational techniques specifically designed for multi-step processes rather than forcing a single model fit. [7]

3. How can I determine the pre-exponential factor for a multi-step reaction? For multi-step reactions where E~a~ varies significantly with conversion, you can use the compensation effect method. This approach establishes a linear relationship between logA~i~ and E~i~ (logA~i~ = aE~i~ + b) determined using different reaction models. The compensation plot allows evaluation of the pre-exponential factor without assuming a specific reaction model. [7]

4. What does the pre-exponential factor tell me about my reaction mechanism? The pre-exponential factor (A) represents the frequency of collisions between reactant molecules with proper orientation. It relates to the activation entropy, and changes in this parameter can provide insights into molecular configuration and reaction feasibility. Lower than expected values may indicate complex orientation requirements or steric effects. [7] [8]

5. How do I handle parallel-consecutive bimolecular reactions kinetically? For parallel-consecutive bimolecular reactions (A + B → C, C + B → D), you can use solutions based on the Lambert-W function. This approach allows direct solution of the inverse kinetic problem by establishing characteristic equations that relate concentration ratios to rate constant quotients (κ = k~2~/k~1~), independent of initial mixing ratios. [9]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent activation energies | • Single-step assumption for multi-step process• Insufficient heating rate data | • Check E~a~ dependence on conversion• Use model-free methods (e.g., Friedman)• Collect data at 4-5 different heating rates [7] |

| Unphysical pre-exponential values | • Incorrect reaction model assumption• Compensation effect not accounted for | • Use model-free determination of A• Apply compensation plot (logA~i~ vs E~i~) for multi-step kinetics [7] |

| Poor fit at extreme conversions | • Change in rate-limiting step• Mass/heat transfer limitations | • Analyze E~a~ across full conversion range• Verify kinetic control by testing different sample masses [7] |

| Difficulty modeling complex reactions | • Inadequate mathematical solution• Limited traditional approaches | • Implement Lambert-W function solutions• Consider data-driven recursive kinetic modeling [2] [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Triplet Determination

Protocol 1: Model-Free Kinetic Analysis Using Isoconversional Methods

Principle: This method determines activation energy without assuming a specific reaction model by analyzing data at constant conversion points across multiple temperature programs. [7]

Procedure:

- Experimental Data Collection:

- Perform thermal analysis (TGA/DSC) at 4-5 different heating rates (e.g., 2, 5, 10, 15, 20°C/min)

- Record conversion (α) and temperature (T) data for each heating rate

Activation Energy Determination:

- Apply Friedman's isoconversional method: ln(dα/dt)~α~ = ln[A~α~f(α)] - E~α~/(RT~α~)

- For each conversion value (α = 0.1, 0.2, ..., 0.9), plot ln(dα/dt)~α~ against 1/T~α~

- Calculate E~α~ from the slope (-E~α~/R) of the linear regression

Preexponential Factor Evaluation:

- For single-step processes (constant E~α~): Use model-based approach with assumed f(α)

- For multi-step processes (varying E~α~): Apply compensation effect using multiple reaction models

Reaction Model Selection:

- Use master plots or nonlinear regression to identify appropriate f(α)

- Validate with experimental data

Materials Required:

- Thermal analysis instrument (TGA or DSC)

- Samples in controlled atmosphere

- Temperature calibration standards

- Data analysis software with kinetic capabilities

Protocol 2: Solving Parallel-Consecutive Bimolecular Reactions

Principle: This protocol uses mathematical transformations and the Lambert-W function to determine rate constants for competitive-consecutive reactions where traditional integration fails. [9]

Procedure:

- Reaction Monitoring:

- Track concentrations of reactants (A, B) and intermediate (C) over time

- Use analytical techniques appropriate for your system (HPLC, NMR, spectroscopy)

Data Transformation:

- Convert concentrations to fractional values: β = B/B~0~, γ = C/B~0~

- Calculate the ratio β/γ throughout the reaction progression

Rate Constant Determination:

- Apply the characteristic equation: (β/γ - lnβ) / (-lnβ) = κ (where κ = k~2~/k~1~)

- Use approximation: κ ≈ [β/γ + √(2/(1 + β/γ)) × (1/β - 1)] / (-lnβ)

- Plot characteristic function to obtain κ from slope

Validation:

- Compare experimental data with simulated profiles using determined κ

- Verify stationary point conditions where dC/dt = 0

Kinetic Relationships and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Kinetic Analysis Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: Kinetic Triplet Interrelationships

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Research Tool | Function in Kinetic Studies | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Measures mass change vs temperature/time for solid-state kinetics | Use with controlled atmosphere; multiple heating rates required for model-free analysis [7] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Monitors heat flow during thermal transitions for curing, decomposition | Ideal for condensed phase kinetics; requires calibration for quantitative work [7] |

| Lambert-W Function Implementation | Solves inverse kinetic problem for parallel-consecutive reactions | Implement as macro in spreadsheet software using series expansion [9] |

| Kinetic Analysis Software | Fits complex mechanisms and performs nonlinear regression | Enables global fitting of multiple experiments to unified model [10] |

| Temperature Jump Apparatus | Studies rapid reactions via rapid T increase and relaxation monitoring | Shock tube version can increase gas temperature by >1000 degrees rapidly [11] |

The Role of Automation and Big Data in Handling Complex Reaction Networks

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Challenges

Q: My automated reaction network generator is missing known reaction pathways. How can I improve its coverage?

- Problem: The generated network is incomplete because the algorithm's reaction rules are too restrictive.

- Solution: Implement a knowledge-driven approach to rule generation. Manually curate reaction rules from literature and experimental data, expressing them as a Reaction Rules Topological Matrix Representation (RTMR). This matrix efficiently captures reaction mechanisms, allowing the algorithm to recognize a wider array of possible elementary steps [12].

- Protocol:

- Literature Curation: Collect known elementary reactions and transition state changes for your specific reaction system (e.g., methanol-to-olefins) from published studies.

- Define Species Matrix: Represent each species with a matrix that includes an element vector (listing atoms/groups) and an adjacency matrix (defining connectivity) [12].

- Build RTMR: For each reaction rule, create an RTMR. This matrix describes the transformation by defining the change in the species matrix from reactants to products [12].

- Integrate Rules: Feed these RTMR-based rules into your network generation algorithm to ensure known pathways are systematically included.

Q: The kinetic model trained on my lab-scale data fails to predict product distribution at the pilot scale. How can I make the model work across different scales?

- Problem: Apparent reaction rates change with reactor size and operation mode, but intrinsic mechanisms remain the same.

- Solution: Use a hybrid model that combines a mechanistic model with deep transfer learning. The mechanistic model captures the intrinsic reaction chemistry, while transfer learning adjusts for scale-specific transport phenomena [13].

- Protocol:

- Develop Base Model: Create a high-precision, molecular-level kinetic model using detailed lab-scale data [13].

- Generate Training Data: Use the mechanistic model to create a large dataset of molecular conversions under various conditions [13].

- Train Initial Network: Train a deep neural network (e.g., using a ResMLP architecture) on this data to create a lab-scale data-driven model [13].

- Fine-Tune with Pilot Data: Employ a property-informed transfer learning strategy. Incorporate bulk property equations into the network and fine-tune specific parts of the neural network using a limited set of pilot-scale data to adapt it to the new scale [13].

Q: Analyzing time-resolved experimental data to extract a kinetic model is slow and model-dependent. Is there a more automated and objective method?

- Problem: Traditional global target analysis requires manual testing of many kinetic models and assumptions, which is time-consuming and requires expert knowledge [4].

- Solution: Implement a deep learning framework, such as the Deep Learning Reaction Network (DLRN), to automatically determine the most probable kinetic model, its time constants, and species amplitudes from 2D time-resolved data [4].

- Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Format your 2D time-resolved data (e.g., wavelength vs. time).

- Model Inference: Input the data into the DLRN. Its model block will analyze the signal and output a one-hot encoding representing the most probable kinetic model from a library of possibilities [4].

- Parameter Extraction: The DLRN's time and amplitude blocks then process this to output the specific time constants (τ) and species-associated amplitudes (SAS) for the identified model [4].

- Validation: The framework provides high accuracy, with Top 1 model prediction accuracy of 83.1% and time constant predictions with less than 20% error in 95.2% of cases on test data [4].

Q: The full reaction network generated by my software is too large and complex to interpret. How can I identify the most critical pathways?

- Problem: Visualizing and analyzing a massive network with hundreds of intermediates is impractical.

- Solution: Use network theory and graph analysis tools to simplify and interrogate the network. Calculate centrality metrics to find key intermediates and perform shortest-path analyses [14].

- Protocol:

- Data Export: Export your reaction network as a CSV file with two columns: "source" (reactant/intermediate) and "target" (product/intermediate) [14].

- Centrality Analysis: Use a platform like the Catalyst Acquisition by Data Science (CADS) GUI to calculate centrality measures (e.g., betweenness, closeness). This identifies nodes (species) that control the flow of the network [14].

- Path Finding: Use the shortest-path search function to find the most efficient routes (in terms of steps or energy) between your defined reactants and products [14].

- Visualization: Highlight these critical nodes and paths to simplify the visual representation and focus mechanistic studies on the most relevant species [15] [14].

Performance Metrics of Automated Kinetic Modeling Tools

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Data-Driven Frameworks for Kinetic Modeling

| Framework | Primary Function | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDCD-NN (Machine Learning Potential) [16] | Reaction pathway prediction & network exploration | Achieves QM accuracy; 10,000x speedup vs. DFT calculations; validated on 181 elementary reaction types. | Data-efficient; excellent transferability for reactive systems. |

| DLRN (Deep Learning Reaction Network) [4] | Model, time constant, and amplitude extraction from time-resolved data | Top 1 model accuracy: 83.1%; Time constant prediction accuracy (error <20%): 95.2%. | Automates model selection in global target analysis (GTA). |

| Hybrid Mechanistic/Transfer Learning Model [13] | Cross-scale computation (lab to pilot plant) | Enabled accurate pilot-scale prediction using limited data after training on lab-scale model. | Addresses data discrepancy between scales (molecular vs. bulk properties). |

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Reaction Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Reaction Rule Topological Matrix (RTMR) [12] | A knowledge-driven representation of reaction mechanisms that enables computers to automatically generate comprehensive reaction networks. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) [16] | Provides quantum-mechanical accuracy for molecular dynamics simulations at a fraction of the computational cost of DFT, enabling rapid exploration of reaction paths. |

| Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS) - ACE Reaction [15] | A software tool that quickly generates initial reaction networks by proposing intermediates and elementary steps based on molecular graphs and user-defined active atoms. |

| CADS Network GUI [14] | A web-based graphical interface that allows researchers to visualize complex reaction networks and perform centrality and shortest-path analyses without programming. |

| Property-Informed Transfer Learning [13] | A strategy that integrates bulk property equations into a neural network, allowing it to bridge the data gap between molecular lab data and bulk pilot-scale data. |

Workflow Visualization

Hybrid Model for Cross-Scale Prediction

Automated Kinetic Analysis with DLRN

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the biggest advantage of using a machine learning potential (MLP) like MDCD-NN over traditional computational methods? The primary advantage is the combination of quantum-mechanical (QM) accuracy with a massive computational speedup—achieving up to a 10,000-fold acceleration compared to standard density functional theory (DFT) calculations [16]. This allows researchers to explore reaction pathways and conduct molecular dynamics simulations on a nanosecond scale, which would be prohibitively expensive with conventional QM methods.

Q2: My experimental data from the pilot plant is limited. Can I still use machine learning for scale-up? Yes. Strategies like deep transfer learning are specifically designed for this scenario. You can first train a model on a large, computationally generated dataset from a validated lab-scale mechanistic model. Then, with only a small amount of pilot-scale data, you can fine-tune the model to adapt it to the new reactor environment, effectively transferring the knowledge from the lab scale [13].

Q3: How do I choose between different automated network generators like ACE Reaction, RMG, or a knowledge-driven RTMR approach? The choice depends on your system's knowledge and goal. Use ACE Reaction for a quick, initial guess of a network when you have defined reactants, products, and a set of active atoms [15]. Use RMG or similar generators for systems with well-established, predefined reaction rules [12]. For complex catalytic systems with rich mechanistic literature (like methanol-to-olefins), a knowledge-driven RTMR approach is powerful, as it systematically encodes known elementary steps from published data to build a comprehensive network [12].

Q4: The concept of "centrality" in network analysis keeps coming up. What does it mean for a chemical intermediate to have high centrality? In chemical reaction networks, centrality is a measure of a species' importance based on its position within the web of reactions. An intermediate with high betweenness centrality, for example, acts as a critical hub or gateway through which many reaction paths must pass. Identifying such species is crucial because they often represent the most influential intermediates, controlling overall reaction rates, selectivity, and efficiency [14].

Kinetic Modeling Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when developing and applying kinetic models across chemical and biological domains.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My kinetic model fits the calibration data well but fails to predict outcomes under new conditions. What is the cause?

A: This common issue often stems from model overfitting or incorrect equilibrium assumptions. Research on sodium sulfide kinetics found predictive accuracy reduced by a factor of 16.1 outside the calibration temperature range [5]. To resolve this:

- Ensure your training data spans the full range of expected operational conditions

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters - studies show model performance is most dependent on activation energy and equilibrium conditions with average absolute sensitivity indices of 38.6 and 12.4, respectively [5]

- Use cross-validation with separate calibration and validation datasets

- Consider implementing a framework for rapid, application-specific model generation [5]

Q: When modeling biological systems, should I use deterministic or stochastic methods?

A: The choice depends on molecular copy numbers and system homogeneity [17]:

- Use ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for systems with high molecular concentrations where stochastic fluctuations are negligible

- Employ stochastic simulation algorithms (SSA) when copy numbers are very low, giving rise to significant relative fluctuations [17]

- For mixed-scale problems, hybrid approaches that separate deterministic and stochastic parts can increase computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy [17]

Typical microbial cell volumes are ~10 femtoliters, where the concentration of 1 molecule equals roughly 160 picomolar, often necessitating stochastic methods [17].

Q: How do I approach kinetic modeling for complex biologics with multiple degradation pathways?

A: Complex biologics like viral vectors and RNA therapies require specialized modeling approaches beyond standard Arrhenius kinetics [18]:

- Use data from multiple analytical methods to build advanced kinetic models explaining different degradation routes

- Implement Accelerated Stability Assessment Programs (ASAP) using short-term studies at various temperature and humidity conditions

- For early development with limited material, kinetic modeling can provide reliable shelf-life predictions in weeks rather than years [18]

Q: What computational tools are available for analyzing complex kinetic models?

A: Specialized software toolkits like TChem provide comprehensive support for complex kinetic analysis [19]:

- Computes thermodynamic properties, source terms, and Jacobian matrices

- Supports both gas-phase and surface chemistry with mechanisms from Chemkin/Cantera input files

- Includes canonical reactor models (constant pressure/volume ignition, plug-flow reactor, transient CSTR)

- Designed for parallel evaluation of samples to enable large-scale parametric studies [19]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent kinetic results from biological replicates

- Cause: Intrinsic stochasticity in cellular systems with low copy numbers [17]

- Solution: Increase simulation runs using tau-leaping algorithms for significant speedups, or use probability-weighted dynamic Monte Carlo methods [17]

Problem: Model fails to capture spatial heterogeneity in biological systems

- Cause: Assuming well-stirred conditions when local environmental factors affect kinetics [17]

- Solution: Implement locally homogeneous approach subdividing system volume into K subvolumes considered spatially homogeneous, then linking compartments at higher system scale [17]

Problem: Difficulty determining rate constants for multi-step reactions

- Cause: Complex reaction pathways with competing mechanisms [5]

- Solution: Use global optimization algorithms like Shuffled Complex Evolution (SCE) to directly calibrate reaction models from standard thermal analysis data [5]

Quantitative Data for Kinetic Modeling

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting Kinetic Model Performance

| Parameter | Impact on Model Performance | Typical Sensitivity Index | Remediation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy | Highest sensitivity parameter | 38.6 [5] | Precise experimental determination using temperature-dependent studies |

| Equilibrium Conditions | Critical for prediction accuracy | 12.4 [5] | Quantify hysteresis through Simultaneous Thermal Analysis [5] |

| Physical State of Reactants | Affects reaction interface and rate [11] | System-dependent | Increase surface area through crushing solids; vigorous shaking for liquid-gas systems [11] |

| Temperature | Major effect through Arrhenius equation | Varies by system | Use temperature jump method for rapid reactions; control within narrow ranges [11] |

Table 2: Comparison of Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Approach | Best For | Limitations | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic (ODE/PDE) | Systems with high molecular concentrations; Well-stirred conditions [17] | Fails for low copy numbers; Continuous concentration assumption invalid [17] | Moderate; Handles stiffness with appropriate solvers |

| Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) | Biological systems with low copy numbers; Molecular fluctuations matter [17] | Computationally expensive for large systems [17] | High; Exact but slow for many reactions |

| Tau-Leaping | Approximate stochastic simulation; Larger systems [17] | Introduces tolerable inexactness [17] | Moderate; Significant speedups possible |

| Hybrid Methods | Multiscale problems; Mixed deterministic/stochastic systems [17] | Implementation complexity; Boundary handling [17] | Variable; More efficient than pure SSA |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Step Kinetic Characterization Using Global Optimization

This protocol enables robust kinetic model calibration for materials with complex, multi-step reaction behavior, adapted from thermochemical energy storage research [5].

Materials:

- Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA)

- Temperature control system (±0.1°C precision)

- Data acquisition software

- Global optimization algorithm implementation (e.g., Shuffled Complex Evolution)

Procedure:

- Equilibrium Quantification: Perform STA analysis across expected temperature range to quantify hysteresis in equilibrium properties [5]

- Model Formulation: Formulate multiple variations of reaction kinetic models (recommended: 8 variations) accounting for reaction hysteresis [5]

- Algorithm Calibration: Use Shuffled Complex Evolution algorithm to calibrate models against time-series STA data [5]

- Model Validation: Validate resulting models with separate dataset; select best-performing model based on prediction accuracy under varying operating conditions [5]

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform comprehensive sensitivity analysis focusing on activation energy and equilibrium conditions [5]

Expected Outcomes:

- Predictive models accurate within calibration range

- Understanding of model limitations outside calibration conditions

- Identification of most sensitive parameters for targeted experimental refinement

Protocol 2: Stochastic Kinetic Simulation for Biological Systems

This protocol provides methodology for implementing stochastic simulation of biological networks with low copy numbers [17].

Materials:

- Reaction network specification (species, reactions, rates)

- Initial molecular counts

- Stochastic simulation algorithm implementation

- Computing resources appropriate for system size

Procedure:

- System Assessment: Determine if system requires stochastic approach based on molecular concentrations and cellular volume [17]

- Algorithm Selection:

- Spatial Considerations: For spatially heterogeneous systems, implement locally homogeneous approach by subdividing volume into K subvolumes [17]

- Simulation Execution: Run sufficient replicates to account for inherent stochasticity

- Data Analysis: Analyze both average behaviors and fluctuations around means

Expected Outcomes:

- Realistic simulation capturing intrinsic biological fluctuations

- Understanding of variability in system responses

- Identification of conditions where deterministic approximations fail

Workflow Visualization

Kinetic Modeling Approach Selection

Biologics Stability Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Modeling

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA) | Quantifies equilibrium hysteresis and provides time-series data for model calibration [5] | Multi-step reaction characterization in materials science |

| TChem Software Toolkit | Computes thermodynamic properties, source terms, and Jacobian matrices for complex kinetic models [19] | Analysis of gas-phase and surface reactions across multiple reactor types |

| Shuffled Complex Evolution (SCE) Algorithm | Global optimization for direct calibration of reaction models from experimental data [5] | Parameter estimation in complex multi-step reaction systems |

| Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) | Exact stochastic simulation of chemical reaction networks accounting for molecular fluctuations [17] | Biological systems with low copy numbers where deterministic models fail |

| Temperature Jump Apparatus | Rapid temperature increase to study relaxation kinetics of fast reactions [11] | Determination of reaction kinetics on millisecond timescales |

| NASA Polynomial Databases | Provide thermodynamic properties for species in kinetic models [19] | Calculation of enthalpy, entropy, and heat capacities in reaction systems |

| Accelerated Stability Assessment Program (ASAP) Tools | Short-term studies at multiple conditions for predictive shelf-life modeling [18] | Biologics formulation development with limited material |

Understanding White-Box and Black-Box Models

In kinetic modeling for reaction optimization, the choice between white-box and black-box models is fundamental. These approaches offer different trade-offs between interpretability and predictive power for researchers and drug development professionals.

White-Box Models, also known as mechanistic or interpretable models, are characterized by their full transparency. Their internal logic, parameters, and decision-making processes are fully accessible and understandable to researchers [20] [21]. In the context of kinetic modeling, this includes methodologies like SKiMpy and MASSpy which use a stoichiometric network as a scaffold and allow for the assignment of kinetic rate laws from a built-in library [22]. Their operations are based on established scientific principles, such as enzyme kinetics and thermodynamic constraints, making them fully interpretable.

Black-Box Models, in contrast, are defined by their opacity. While users can provide inputs and observe outputs, the internal computational processes that connect them are hidden or too complex for human interpretation [20] [23]. These are typically sophisticated, data-driven models like Deep-learning models and LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks that can model extremely complex, non-linear scenarios [20] [24]. They develop their own parameters through deep learning algorithms, often resulting in a complex network of hundreds or thousands of layers that even their creators may not fully understand [23].

The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | White-Box Models | Black-Box Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Based on established scientific principles and mechanisms [22]. | Relies on discovering complex patterns from data [20]. |

| Interpretability | High; every parameter (e.g., kinetic constants) has a biochemical interpretation [22]. | Low; internal workings are a mystery [23]. |

| Typical Predictive Accuracy | Can be lower for highly complex systems, as they rely on pre-defined knowledge [20]. | High; can model complex, non-linear relationships often missed by simpler models [20] [23]. |

| Data Requirements | Can be built with less data, guided by domain knowledge. | Requires massive, high-quality datasets for training [23] [22]. |

| Best Suited For | Scientific discovery, hypothesis testing, risk assessment, and systems where understanding is critical [20] [22]. | Tasks like image/speech recognition, and modeling systems where mechanistic knowledge is limited [20] [23]. |

| Examples in Kinetic Modeling | Models built with SKiMpy, MASSpy, Tellurium using canonical rate laws [22]. | LSTM networks and other deep-learning models for building energy or complex metabolic predictions [24] [22]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Model Selection and Implementation

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when working with white-box and black-box models in kinetic modeling.

FAQ 1: How do I choose between a white-box and black-box model for my kinetic modeling project?

| Consideration | Guidance | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Project Goal | Is the goal fundamental understanding or high-accuracy prediction? | For insight into mechanisms (e.g., identifying a rate-limiting enzyme), choose a White-Box model. For predicting a complex system's output (e.g., final product titer), a Black-Box model may be better [20] [22]. |

| Available Data | How much high-quality experimental data is available? | With limited data, a White-Box model guided by domain knowledge is more robust. Black-Box models require large datasets to learn effectively without overfitting [22]. |

| Regulatory & Reporting Needs | Is model interpretability a requirement for regulatory approval or scientific publication? | In drug development or for building credible scientific narratives, White-Box models or hybrid approaches are often necessary to explain the model's reasoning [20] [23]. |

| System Complexity | How well-understood are the underlying mechanisms of the system? | For well-characterized pathways, use White-Box. For systems with unknown or highly complex interactions, a Black-Box can be a starting point [20]. |

FAQ 2: My white-box kinetic model's predictions deviate significantly from experimental data. How can I improve it?

This often indicates an incomplete or inaccurate mechanistic description. Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Identify which kinetic parameters (e.g., ( Km ), ( V{max} )) your model's output is most sensitive to. Focus experimental efforts on re-measuring these high-sensitivity parameters with greater precision [22].

- Validate Thermodynamic Consistency: Ensure your model complies with the second law of thermodynamics. Use computational techniques like the group contribution method to estimate Gibbs free energy and validate reaction directionality [22].

- Check for Missing Regulation: The discrepancy may be due to unmodeled regulatory mechanisms (e.g., allosteric inhibition, feedback loops). Review recent literature on the pathway and incorporate missing regulatory interactions using appropriate rate laws [22].

- Refine with Machine Learning: Leverage generative machine learning methodologies to rapidly sample and prune kinetic parameter sets that are consistent with your new experimental data, ensuring physiologically relevant time scales [22].

FAQ 3: My black-box model is accurate but I cannot interpret its predictions. How can I build trust and extract insight?

This is the core challenge of using black-box models in research. Several techniques can help:

- Employ Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Use tools like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations). LIME creates a simpler, interpretable model (like a linear model) that approximates the black-box model's predictions for a specific input, highlighting which features were most influential for that particular prediction [20] [23].

- Perform a Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically vary the input features of your black-box model and observe the changes in output. This can reveal which inputs the model is most sensitive to, providing clues about what it has "learned" is important [20].

- Use as a Discovery Engine: If the black-box model is highly accurate, use its predictions to form new hypotheses. For example, if it predicts high yield under unexpected conditions, test these conditions in the lab and use the results to refine a white-box model [22].

FAQ 4: How can I integrate the strengths of both white-box and black-box approaches?

A hybrid, "gray-box" approach is often the most powerful strategy for kinetic modeling:

- White-Box Core: Start with a mechanistic white-box model based on established biochemistry (e.g., using a framework like SKiMpy) [22].

- Black-Box Enhancement: Use a machine learning model (e.g., an LSTM) not to replace the mechanistic model, but to learn the discrepancy or error between the white-box model's predictions and the experimental data.

- Combined Prediction: The final prediction is the sum of the white-box model output and the ML-predicted discrepancy. This allows the model to capture complex, unmodeled dynamics while remaining grounded in mechanistic theory [22].

The workflow for this diagnostic and integration process is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Frameworks

The following table details essential computational tools and their functions for developing kinetic models in systems and synthetic biology.

| Tool/Framework | Primary Function | Model Class | Key Application in Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| SKiMpy [22] | Semiautomated construction and parametrization of large kinetic models. | White-Box | Uses stoichiometric models as a scaffold, assigns rate laws, samples parameters, and ensures thermodynamic consistency. |

| MASSpy [22] | Simulation and analysis of kinetic models. | White-Box | Built on COBRApy; uses mass-action or custom rate laws for dynamic simulation, integrated with constraint-based modeling. |

| Tellurium [22] | Integrated environment for systems and synthetic biology models. | White-Box | Supports standardized model formulations (e.g., ODEs) for simulation, parameter estimation, and visualization. |

| LSTM Networks [24] | Deep learning models for sequence and time-series data. | Black-Box | Empirical modeling of complex, dynamic systems like building energy use or metabolic responses without mechanistic details. |

| LIME [20] [23] | Explainable AI (XAI) technique for model interpretation. | Agnostic | Creates local, interpretable approximations of black-box model predictions to identify influential input features. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Developing a Hybrid Kinetic Model

This protocol outlines a methodology for constructing a robust kinetic model by combining white-box and black-box approaches, suitable for genome-scale metabolic studies [22].

Objective: To build a kinetic model that is both mechanistically grounded and capable of capturing complex, unmodeled dynamics for reliable prediction of metabolic responses.

Materials/Software:

- Stoichiometric Model: A genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for your organism of interest.

- Experimental Data: Time-course metabolomics data and steady-state flux data.

- Computational Tools: A white-box framework like SKiMpy or MASSpy, and a machine learning library (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) for building the discrepancy model.

Procedure:

Construct the Base White-Box Model:

- Use the network structure of your stoichiometric GEM as a scaffold.

- Assign appropriate kinetic rate laws (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, convenience kinetics) to each reaction from a built-in library or define your own.

- Use the ORACLE framework or similar within SKiMpy to sample kinetic parameter sets that are consistent with thermodynamic constraints and available steady-state experimental data [22].

Generate Initial Predictions and Calculate Discrepancy:

- Run simulations with your parametrized white-box model using initial conditions from your experimental data.

- Collect the model's predictions for metabolite concentrations over time.

- Calculate the discrepancy vector at each time point: ( \epsilon(t) = Y{exp}(t) - Y{wb}(t) ), where ( Y{exp} ) is the experimental measurement and ( Y{wb} ) is the white-box model prediction.

Train the Black-Box Discrepancy Model:

- Use a machine learning model (e.g., LSTM) to learn the mapping between the system's state (e.g., current metabolite concentrations, environmental conditions) and the discrepancy ( \epsilon ).

- The input features for the ML model are the state variables from the white-box model, and the target output is the calculated discrepancy.

Integrate into a Hybrid Model:

- The final hybrid model's prediction is given by: ( Y{hybrid}(t) = Y{wb}(t) + ML(State(t)) ).

- Here, ( ML(State(t)) ) is the discrepancy predicted by the machine learning model.

Validate and Refine:

- Test the hybrid model on a separate validation dataset not used during training.

- Compare its predictive accuracy against the standalone white-box model and the raw ML model.

- Use sensitivity analysis on the hybrid model to identify potential weaknesses in the white-box core and guide further experimental design.

The workflow for this hybrid modeling approach is illustrated below:

Methodologies in Action: Selecting and Applying Kinetic Models for Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a model-free and a model-fit approach in kinetic modeling? Model-free methods, often called "non-compartmental analysis," do not assume a specific underlying structural model for the process. They are used to directly estimate fundamental parameters like initial rates from experimental data. In contrast, model-fit approaches involve proposing a specific kinetic mechanism (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Langmuir-Hinshelwood) and then using regression analysis to fit the model's parameters to the experimental data, allowing for a deeper mechanistic interpretation [25].

Q2: My model fitting consistently fails to converge. What are the most common causes? Non-convergence typically stems from three main issues:

- Poor Initial Parameter Estimates: The starting values for your parameters (e.g.,

k_cat,K_M) are too far from their true values, preventing the algorithm from finding a solution. - Model Misspecification: The chosen kinetic model does not accurately represent the true underlying reaction mechanism.

- Data Quality Issues: High levels of noise, insufficient data points, or significant experimental outliers can derail the fitting algorithm. A step-by-step troubleshooting guide is provided in the next section.

Q3: How do I know if my chosen model is a good fit for the data? A good fit is validated using multiple criteria, not just a single metric. Key indicators include:

- Visual Inspection: The fitted model curve should pass through the data points without systematic deviations.

- Residual Analysis: The residuals (difference between data and fit) should be randomly distributed around zero.

- Quantitative Metrics: Statistical parameters like R², Adjusted R², and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) should be evaluated. AIC is particularly useful for comparing the quality of different models while penalizing for complexity.

Q4: When should I use a sequential experimental design versus a parallel one? This decision depends on your optimization goals and resources.

- Use a Sequential Design when each experiment can be informed by the results of the previous one. This is highly efficient for focused parameter optimization and requires fewer total experiments.

- Use a Parallel Design when you need to screen a broad range of conditions simultaneously, such as different catalysts or solvents at the outset of a project. This is faster for initial screening but may require more resources upfront [26] [27].

Q5: What is the purpose of a "compensation task" or error handling in an automated workflow? In automated reaction optimization, a "compensation task" is a predefined action to handle failures. If a reaction in a high-throughput screener fails or yields an error, the system can trigger a compensation event, such as re-running the reaction with modified conditions, flagging it for manual review, or cleaning the reactor vessel to prepare for the next experiment. This ensures robustness and minimizes downtime [26] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fitting Fails to Converge

Convergence errors indicate that the fitting algorithm cannot find a set of parameters that minimizes the difference between the model and the data.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Initial Parameter Guesses | Algorithm converges or proceeds to the next step. |

| 2 | Check for Model Misspecification | A new, more appropriate model is selected for testing. |

| 3 | Audit Data Quality | Noisy data is smoothed or outliers are justifiably removed. |

| 4 | Adjust Algorithmic Settings | The fitting process completes with a lower error. |

1. Verify Initial Parameter Guesses

- Methodology: Manually calculate rough estimates of your parameters from the raw data before fitting. For example, estimate the maximum reaction rate (

V_max) from the plateau of your progress curve and the Michaelis constant (K_M) from the substrate concentration at halfV_max. - Protocol: Use plotting software to visually overlay the model prediction using your initial guesses onto the raw data. If the curve is not even remotely close to the data cloud, refine your guesses manually until it is.

- Solution: Provide these improved estimates as the new starting points for the automated fitting routine.

2. Check for Model Misspecification

- Methodology: Compare the fit of several plausible rival models. For instance, if a Michaelis-Menten model fits poorly, test a model that accounts for substrate inhibition.

- Protocol: Fit all candidate models to your dataset. Calculate and compare the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for each. The model with the lowest AIC is generally preferred.

- Solution: Select the model with the best statistical and mechanistic support.

3. Audit Data Quality

- Methodology: Perform a residual analysis. Plot the residuals (observed - predicted) against the independent variable (e.g., time or concentration).

- Protocol: If the residuals show a non-random pattern (e.g., a curve), it suggests a systematic error and model misspecification. If residuals are random but large, it indicates high noise.

- Solution: For high noise, consider whether you can repeat experiments to reduce uncertainty. Identify and investigate potential outliers; remove them only if there is a solid experimental justification (e.g., a known pipetting error).

4. Adjust Algorithmic Settings

- Methodology: Change the configuration of the non-linear regression algorithm itself.

- Protocol: Increase the maximum number of iterations allowed. If possible, switch the optimization algorithm (e.g., from Levenberg-Marquardt to Gauss-Newton) or adjust convergence tolerance thresholds.

- Solution: The algorithm completes its iterations and successfully returns a set of best-fit parameters.

Problem: High Uncertainty in Fitted Parameters

Even if a model converges, the fitted parameters may have very wide confidence intervals, making them unreliable.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increase Data Density | Confidence intervals for parameters are reduced. |

| 2 | Improve Experimental Design | Data is collected in the most informative regions of the experimental space. |

1. Increase Data Density

- Methodology: Collect more experimental data points, particularly in regions where the model is most sensitive to parameter changes.

- Protocol: For a saturation kinetic model, this means ensuring you have multiple data points in the low-concentration region (where the curve is rising steeply, highly sensitive to

K_M) and in the high-concentration plateau (sensitive toV_max). - Solution: Parameter estimates become more precise, evidenced by narrower confidence intervals.

2. Improve Experimental Design

- Methodology: Use optimal experimental design principles to maximize the information content of each experiment.

- Protocol: Instead of spacing concentrations evenly, place them strategically. For a

K_Mestimate, a concentration near the suspectedK_Mvalue is highly informative. Using a D-optimal design can help identify the best set of conditions to run. - Solution: The same number of experiments yields more robust parameter estimates.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sequential Model-Based Optimization for Reaction Condition Optimization

This protocol uses an iterative loop where a statistical model guides the selection of the most informative experiment to run next.

1. Objective: To find the optimal combination of temperature, catalyst concentration, and reactant stoichiometry to maximize reaction yield with a minimal number of experiments.

2. Workflow Diagram: Sequential Optimization

3. Methodology:

- Initial Design: Start with a space-filling design (e.g., Plackett-Burman or a small D-optimal design) of 8-12 initial experiments to probe the entire factor space.

- Execution & Analysis: Run the designed reactions and analyze the yields.

- Model Building: Fit the results to a statistical model, typically a quadratic response surface model (e.g.,

Yield = β₀ + β₁*Temp + β₂*Cat + β₁₁*Temp² + ...). - Prediction & Selection: Use the model to predict the combination of factors that will yield the highest result. This point is often located where the gradient of the response surface is zero.

- Iteration: Run the proposed experiment. Based on the new result, update the model and repeat the prediction-selection-run cycle until convergence (e.g., when the predicted improvement falls below a pre-defined threshold).

4. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Substrate | The molecule whose conversion is being optimized. |

| Catalyst | The species that lowers the activation energy of the reaction; its concentration is a key variable. |

| Solvent | The reaction medium; its identity can be a categorical variable in the design. |

| Internal Standard | For accurate quantitative analysis (e.g., via GC/MS or HPLC). |

| Quenching Agent | To stop the reaction at precise time points for analysis. |

Protocol 2: Model Discrimination via Multi-Model Fitting

This protocol is used when multiple mechanistic models are plausible, and the correct one must be identified.

1. Objective: To determine whether enzymatic inhibition is competitive, uncompetitive, or non-competitive.

2. Workflow Diagram: Model Discrimination

3. Methodology:

- Data Collection: Measure initial reaction rates (

v₀) across a range of substrate concentrations[S]and at several fixed concentrations of the inhibitor[I]. - Parallel Fitting: Simultaneously fit the entire dataset to each of the three candidate models:

- Model A (Competitive):

v₀ = (V_max * [S]) / (K_M * (1 + [I]/K_ic) + [S]) - Model B (Uncompetitive):

v₀ = (V_max * [S]) / (K_M + [S] * (1 + [I]/K_iu)) - Model C (Non-competitive):

v₀ = (V_max * [S]) / ((K_M + [S]) * (1 + [I]/K_i))

- Model A (Competitive):

- Model Comparison: For each fit, extract the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the R² values.

- Selection: The model with the lowest AIC value is statistically the most likely, given the data. This model is selected for all subsequent interpretation and prediction. Visual inspection of the fitted curves against the data is crucial for final confirmation.

5. Essential Materials for Kinetic Profiling

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme / Catalyst | The active agent whose kinetics are being characterized. |

| Varied Substrate | The reactant whose concentration is systematically changed. |

| Inhibitor/Effector | The molecule used to probe the mechanism of inhibition or activation. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺) | Essential components for the catalytic cycle. |

| Buffer System | To maintain a constant pH throughout the experiment. |

Leveraging the Arrhenius Equation and First-Order Kinetics for Shelf-Life Predictions

Core Concepts: Arrhenius Equation and Reaction Kinetics

The Arrhenius Equation is a fundamental principle in chemical kinetics that describes the temperature dependence of reaction rates. It is vital for predicting how environmental changes, like storage temperature, affect the degradation speed of pharmaceuticals and other products [29]. The basic form of the equation is:

k = A × e^(-Ea/RT)

Where:

- k is the rate constant of the reaction.

- A is the pre-exponential factor, which represents the frequency of collisions with the correct orientation.

- Ea is the activation energy (kJ/mol), the minimum energy required for a reaction to occur.

- R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K).

- T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin (K) [29].

For first-order reactions, the rate of the reaction is directly proportional to the concentration of a single reactant [30] [31]. This is common in degradation processes like decomposition. The differential and integrated rate laws are:

- Differential Rate Law: Rate = -d[A]/dt = k[A]

- Integrated Rate Law: [A] = [A]₀ × e^(-kt) or ln([A]) = ln([A]₀) - kt

Where [A] is the concentration of the reactant at time t, and [A]₀ is the initial concentration [30] [31]. A key parameter derived from the rate constant is the half-life (t₁/₂), the time required for the concentration of the reactant to reduce to half its original value. For a first-order reaction, it is calculated as:

t₁/₂ = ln(2) / k ≈ 0.693 / k [31]

Experimental Protocols for Shelf-Life Prediction

This section outlines a standard methodology for determining the shelf life of a drug substance using accelerated stability studies.

Protocol: Accelerated Stability Testing for Shelf-Life Prediction

1. Objective: To predict the long-term shelf life of a pharmaceutical product by determining the degradation rate constant (k) at elevated temperatures and extrapolating to recommended storage conditions.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Thermostated stability chambers (e.g., 40°C, 50°C, 60°C).

- Analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC) for quantifying drug concentration or degradation products.

- Sealed vials containing the drug product.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Place identical samples of the drug product in stability chambers set at a minimum of three different elevated temperatures.

- Step 2: Sampling. At predetermined time intervals, remove samples from each chamber and analyze them using a stability-indicating method (e.g., HPLC) to determine the percentage of the drug remaining.

- Step 3: Data Collection. Record the concentration of the active ingredient [A] versus time at each temperature.

4. Data Analysis:

- Determine Reaction Order: Plot [A] vs. time, ln[A] vs. time, and 1/[A] vs. time for data at each temperature. The most linear plot indicates the reaction order. The following workflow outlines the data analysis pathway:

- Calculate Rate Constants (k): From the linear plot, obtain the slope, which equals the rate constant (k) for that temperature. For a first-order reaction, use the plot of ln[A] vs. time [31].

- Apply the Arrhenius Equation:

- Plot ln(k) vs. 1/T for all temperatures studied. This should yield a straight line [32].

- The slope of this line is equal to -Ea/R, from which you can calculate the activation energy (Ea).

- The y-intercept is ln(A).

- Predict Shelf Life: Use the calculated Ea and A to compute the rate constant (k₅°C) at the recommended storage temperature (e.g., 5°C). Then, calculate the half-life at this temperature: t₁/₂ = 0.693 / k₅°C. This half-life provides a scientific basis for the proposed shelf life [33].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My Arrhenius plot (ln k vs. 1/T) is not linear. What could be the cause? A: Non-linearity often indicates a change in the reaction mechanism or degradation pathway with temperature [34]. This is common for complex biologics like monoclonal antibodies or viral vectors. Other factors include:

- Solvent Effects: Near a solvent's critical point, properties like dielectric constant change dramatically, affecting the reaction rate in ways the simple Arrhenius model doesn't capture [35].

- Phase Changes: Excipients or the API itself may undergo phase separation, melting, or crystallization at higher temperatures, invalidating the accelerated model [33].

Q2: For a first-order reaction, does the half-life depend on the initial drug concentration? A: No. A key characteristic of a first-order reaction is that its half-life is constant and independent of the initial concentration [31]. It depends only on the rate constant (t₁/₂ = 0.693 / k). If your experimental half-life changes with different starting concentrations, the reaction is likely not first-order.

Q3: How can I accurately model the shelf life of a complex biologic with multiple degradation pathways? A: The traditional Arrhenius approach, which assumes a single activation energy, often fails for complex molecules [34]. A modern approach involves:

- Forcing Degradation Studies: Stressing the product under various conditions (heat, light, oxidation) to identify all major degradation pathways early in development.

- Advanced Modeling: Using AI/ML models that can analyze large, complex datasets to identify patterns and model multiple, non-linear degradation pathways simultaneously, providing a more accurate and reliable prediction [34].

Q4: What are the limitations of using accelerated stability studies for shelf-life prediction? A: Key limitations include [34] [33]:

- Non-Arrhenius Behavior: As above, reactions may not follow the model.

- Confounding Factors: Increased temperature can accelerate physical processes (e.g., evaporation, denaturation) not seen at storage conditions.

- Humidity: Accelerated studies often control temperature but may not perfectly control relative humidity, which can affect moisture-sensitive products.

- Time Bottleneck: While faster than real-time studies, generating sufficient data for a reliable model still requires significant time and a large amount of valuable drug material [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High scatter in concentration vs. time data | Inconsistent sampling or analytical error; reaction too fast for manual sampling. | Standardize analytical methods; use automated equipment like a stopped-flow spectrometer for fast reactions [36]. |

| Degradation rate at accelerated conditions does not predict long-term stability | Change in degradation mechanism at higher temperatures; invalid kinetic model. | Conduct forced degradation studies; employ multi-parameter AI/ML models instead of simple Arrhenius fit [34]. |

| Inconsistent rate constants (k) between replicates | Inadequate temperature control in stability chambers; sample contamination. | Calibrate and monitor stability chambers; use aseptic techniques and sealed containers. |

| Low activation energy (Ea) calculated | Physical loss (e.g., adsorption, volatilization) masquerading as chemical degradation. | Review mass balance; use alternative analytical techniques to account for all species. |

Advanced Kinetic Modeling: Beyond Traditional Arrhenius

For reactions in solution, especially near a solvent's critical point, a modified Arrhenius equation that accounts for solvation effects is more accurate [35]:

kliq = A × exp( (-Ea + ΔΔGsolv‡) / (RT) )

Here, ΔΔG_solv‡ represents the difference in solvation free energy between the transition state and the reactants [35]. Advanced statistical methods like Bayesian Uncertainty Quantification are also being used to provide robust uncertainty bounds on kinetic parameters like Ea, increasing the reliability of shelf-life predictions [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions in stability and kinetics studies.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Thermostated Stability Chambers | Provide a controlled temperature and humidity environment for long-term and accelerated stability studies. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Rapidly mixes reagents and monitors reaction progress on a millisecond timescale, essential for measuring fast degradation kinetics [36]. |

| HPLC with UV/Vis or MS Detector | A stability-indicating analytical method used to separate and quantify the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from its degradation products. |

| Buffer Solutions (e.g., Phosphate, Acetate) | Control the pH of the solution, a critical factor that can significantly influence the degradation rate of many pharmaceuticals. |

| Forced Degradation Reagents (e.g., H₂O₂, HCl, NaOH) | Used in stress testing to intentionally degrade a drug substance to identify potential degradation products and elucidate degradation pathways. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Design of Experiments (DoE)

Q: My DoE models fail to predict reaction outcomes accurately. What could be wrong? A: This often stems from incorrect model structure or unaccounted factor interactions.

- Check Factor Ranges: Ensure your experimental design explores a sufficiently broad and relevant range for each factor. Initial screening designs can help identify critical variables [38].

- Verify Model Assumptions: Use analysis of variance (ANOVA) to check the statistical significance of your model and lack-of-fit tests. Nonsignificant terms should be considered for removal [38].

- Investigate Interactions: If using a fractional factorial design, critical interactions between factors might be confounded (i.e., their effects cannot be distinguished). If interactions are suspected, a full factorial or a different resolution design may be necessary [38].

Q: How can I optimize a process with multiple, competing objectives (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost)? A: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM).

- Employ RSM: RSM is a DoE technique that generates mathematical equations to describe how factors affect multiple responses. It allows you to visualize the compromise between different objectives [38].

- Utilize Multi-Objective Software: Software like MODDE, JMP, or Design-Expert provide tools for multi-objective optimization, helping to identify a set of conditions that balance all your targets [38].

Self-Optimization and Machine Learning

Q: My Bayesian optimization algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum and fails to find the best conditions. How can I improve its performance? A: This is a common challenge related to the exploration-exploitation balance.

- Adjust the Acquisition Function: The acquisition function guides the search. Functions like Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) have parameters that control the exploration-exploitation trade-off. Increasing the weight for exploration can help escape local optima [39].

- Incorporate Transfer Learning: Use frameworks like SeMOpt, which apply meta- or few-shot learning to transfer knowledge from historical, similar experiments. This provides the algorithm with better initial intuition, significantly accelerating the search and improving outcomes [40].

- Ensure Proper Initial Sampling: Start the optimization with a diverse set of initial experiments, such as those selected by Sobol sampling, to achieve broad coverage of the reaction space before the Bayesian algorithm takes over [39].

Q: Our self-optimization platform works well in simulation but performs poorly in the real lab. What should I check? A: The discrepancy often lies in unmodeled physical constraints or experimental noise.

- Validate Physical Constraints: Ensure the algorithm's proposed experiments are physically feasible. Implement automatic filters to exclude conditions that exceed solvent boiling points, cause precipitation, or use unsafe reagent combinations [39].

- Account for Chemical Noise: Real experiments have variability. Choose optimization algorithms like the Gaussian Process (GP) regressors used in frameworks such as Minerva, which are robust to noise and can quantify prediction uncertainty, making the search more resilient to experimental variability [39].

- Inspect Hardware: Check for consistent operation of automated fluid handling, steady temperature control, and calibration of online analyzers like GC or HPLC [41].

Kinetic Modeling

Q: The parameter estimation for my kinetic model fails to converge, or the estimated parameters are physically meaningless. What is the solution? A: This is typically due to parameter correlation, poor initial guesses, or an incorrectly specified model.

- Apply Sequential Parameter Estimation: Use a Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) approach. Instead of estimating all parameters at once, design experiments to estimate specific parameters or groups of parameters that are maximally sensitive in certain time intervals or conditions. This reduces correlation and improves estimability [41].

- Use Model Discrimination: If multiple rival mechanistic models are plausible, use MBDoE to design experiments that can best discriminate between them, thus ensuring you are working with the correct model structure [41].

- Leverage A Priori Knowledge: Use initial parameter estimates from computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) or literature data to provide the optimizer with realistic starting values [41] [42].

Q: How can I build a reliable kinetic model when my reaction network is complex with multiple steps and intermediates? A: A structured, iterative approach is key.

- Start with Model-Free Analysis: Use model-free methods (e.g., Friedman, Ozawa-Flynn-Wall) to determine the activation energy without assuming a reaction model. This provides an initial, model-independent insight into the process kinetics [43].

- Construct and Test Models Visually: Use software like Kinetics Neo to visually build different kinetic models, add or remove reaction steps, and easily compare them. The software provides statistical comparisons to help select the most appropriate model [43].

- Follow ICTAC Recommendations: Adhere to the latest guidelines from the International Confederation for Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (ICTAC) for analyzing multi-step kinetics to ensure your methodology is sound and reproducible [43].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

This protocol details the procedure for refining a kinetic model using MBDoE, based on a published C–H activation reaction study [41].

1. Pre-Experimental Setup:

- Define A Priori Knowledge: Establish the initial reaction mechanism, concentration constraints, and technical details of the experimental setup.

- Develop Initial Model: Formulate the initial model structure and obtain preliminary parameter estimates from sources like DFT calculations or literature.

- Configure Reactor System: Set up a flow reactor system (e.g., Vapourtec R2+/R4 with a 10 mL coil reactor). Use sample loops for reagent injection to ensure precise composition and minimize pump inaccuracies. Establish a method for online detection (e.g., UV) and automated sampling to GC.

2. Iterative MBDoE Cycle:

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a normalized local sensitivity analysis to identify time intervals where specific parameters (e.g.,

k3,ref,Ea,3) are most sensitive. - Design Experiment: In MBDoE software (e.g., gPROMS), design a new experiment to maximize the information for the target parameter(s). The output will specify reaction conditions (concentrations, temperature) and a sampling schedule (multiple time points per experiment).

- Execute Experiment: Run the automated experiment using the specified conditions and collect concentration data at the designed time points via GC.

- Parameter Estimation: Re-estimate the kinetic parameters using the new experimental data.

- Statistical Validation: Perform a t-test to check the statistical significance of the newly estimated parameters. A parameter is considered significant if its t-value is greater than the reference t-value (

t > tref). - Repeat: Iterate the cycle until all parameters are statistically significant and the model accurately describes the experimental data.

Table: Example MBDoE Results for Parameter Estimation [41]

| Experiment | Target Parameter(s) | Number of Samples | t-value | Reference t-value (tref) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | k0,ref |

7 | 76.19 | 2.92 |

| 2 | k2,ref |

6 | 23.36 | 2.92 |

| 3 | k3,ref |

5 | 23.36 | 2.92 |

| 4 | k0,ref, k2,ref, k3,ref |

11 | 5.34, 0.03, 6.42 | 1.94 |

| 7 | Ea,0, Ea,2 |

10 | 2.79, 17.1 | 2.02 |

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Driven Self-Optimization in a 96-Well HTE System

This protocol describes a highly parallel optimization campaign for a Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction using the Minerva framework [39].

1. Define the Reaction Condition Space:

- Enumerate Parameters: List all categorical (e.g., solvent, ligand, base) and continuous (e.g., temperature, catalyst loading) variables.

- Apply Domain Knowledge: Define plausible ranges for continuous variables and a discrete set of options for categorical ones. Apply filters to exclude unsafe or physically impossible conditions (e.g., temperature above a solvent's boiling point).

- Formalize Objectives: Define the optimization objectives, such as maximizing Area Percent (AP) yield and selectivity.

2. Initial Sampling and Automated Execution:

- Select Initial Batch: Use a space-filling algorithm like Sobol sampling to select 96 diverse initial reaction conditions from the defined space.

- Prepare and Run Reactions: Use an automated HTE platform to prepare and execute the first batch of 96 reactions in parallel according to the designed conditions.

- Analyze Outcomes: Use automated analytics (e.g., UPLC) to quantify yield and selectivity for each reaction well.

3. Machine Learning Optimization Cycle:

- Train ML Model: Train a multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm (e.g., using a Gaussian Process regressor) on all data collected so far.

- Select Next Batch: Use a scalable acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to select the next batch of 96 experiments that best balances exploration (trying new regions) and exploitation (improving known good conditions).

- Repeat Execution and Analysis: Run the new batch of experiments, analyze the results, and update the ML model.

- Terminate: Continue for a set number of iterations or until performance converges, typically requiring only 3-5 cycles to identify optimal conditions.

Research Reagent & Software Solutions

Table: Essential Software Tools for Kinetic Modeling and Reaction Optimization

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Supported Data/Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| gPROMS [41] | Process Modeling & MBDoE | Formulate mechanistic models, perform parameter estimation, and design optimal experiments. | Custom kinetic models, process simulation. |

| Kinetics Neo [43] | Kinetic Analysis | Model-free and model-based kinetic analysis; prediction and optimization of temperature programs. | DSC, TGA, DIL, DEA, Rheometry data. |

| KinTek Explorer [10] | Chemical Kinetics Simulation | Real-time simulation and data-fitting; visual parameter scrolling for intuitive understanding. | Enzyme kinetics, protein folding, pharmacodynamics. |

| Minerva [39] | Machine Learning Optimization | Bayesian optimization for large parallel batches (e.g., 96-well); handles high-dimensional spaces. | Yield, selectivity, and other reaction outcomes. |

| Atinary SeMOpt [40] | Transfer Learning for Optimization | Uses historical data to accelerate new optimization campaigns via meta-learning. | Chemical reaction data from prior experiments. |