LC-MS vs. GC-MS for Metabolite Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Life Science Researchers

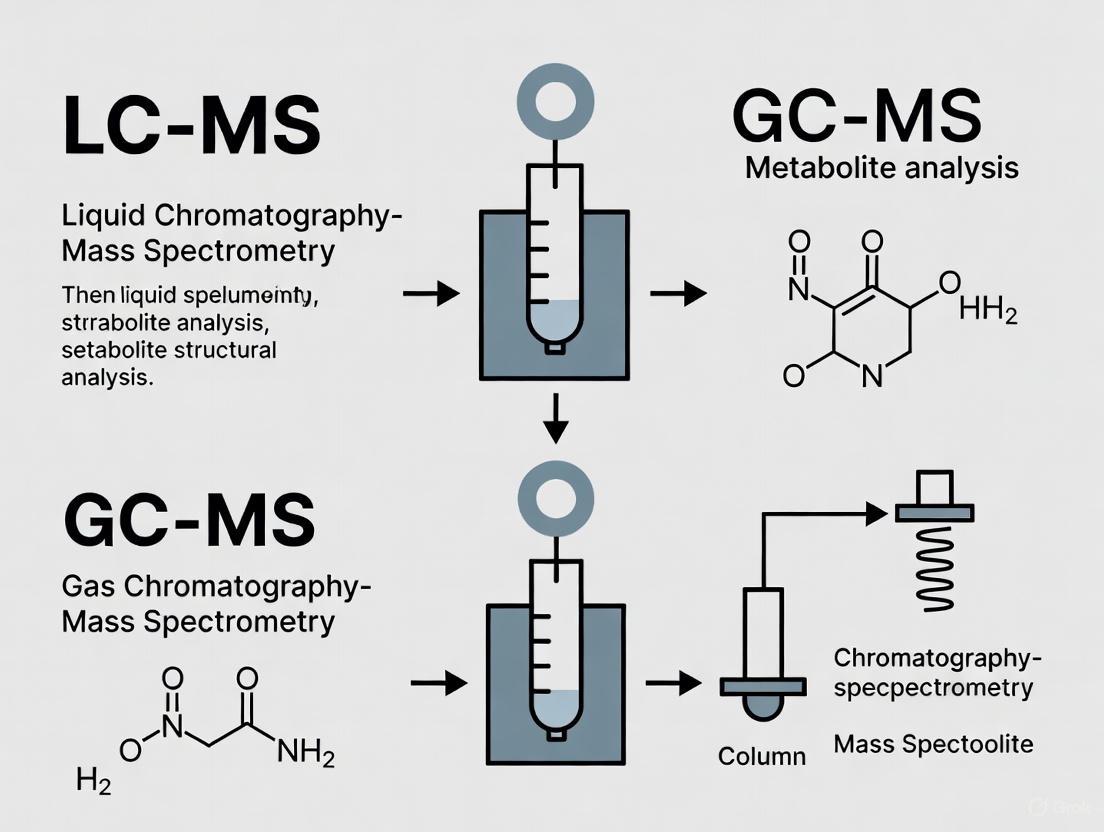

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) for metabolite analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

LC-MS vs. GC-MS for Metabolite Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Life Science Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) for metabolite analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of both platforms, including their distinct ionization sources and separation mechanisms. The scope extends to methodological considerations for diverse applications, best practices for troubleshooting and optimization, and a direct comparative analysis to guide platform selection. By synthesizing current methodologies and applications, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the optimal analytical strategy to enhance coverage, data quality, and biological insight in metabolomics studies.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamentals of LC-MS and GC-MS

Metabolomics, the comprehensive study of small molecule metabolites, relies heavily on advanced analytical technologies to separate, identify, and quantify compounds within complex biological mixtures. The core components of metabolomics analysis technology are separation and detection, primarily utilizing various chromatographic methods coupled with mass spectrometry [1]. Two principal platforms have emerged as cornerstone technologies in this field: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Each platform offers distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal application ranges, making the choice between them critical for research outcomes.

This guide provides an objective comparison of LC-MS versus GC-MS performance for metabolite analysis, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies. Within the broader thesis of comparing these analytical platforms, we examine specific workflows from sample preparation to data analysis, enabling researchers to make informed decisions based on their specific analytical needs. The sophisticated interplay between separation science and detection technology forms the foundation of modern metabolomics, allowing scientists to probe biochemical pathways with unprecedented depth and precision [1] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Technical Differences

The fundamental distinction between LC-MS and GC-MS lies in their separation mechanisms and the physical states of their mobile phases. LC-MS uses a liquid mobile phase to move the sample between columns, exploiting the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties of substances to adsorb onto the solid phase [3] [1]. Different substances separate out in the changing mobile phase, facilitating detection by mass spectrometry. In contrast, GC-MS employs an inert gas mobile phase (typically helium) to transport the sample through a chromatographic column that is typically much longer than those used in liquid chromatography, allowing for superior substance separation [1].

The ionization techniques employed by these platforms differ significantly, profoundly impacting the type of data generated. LC-MS typically uses softer ionization techniques such as Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which cause the substance to become positively or negatively charged without immediately breaking into fragments [1]. Conversely, GC-MS utilizes Electron Impact (EI) ionization, a hard ionization method that breaks molecules into fragment ions before they enter the mass analyzer [1]. This results in rich fragmentation patterns that can be exploited for increased specificity in mass spectral matching.

Table 1: Fundamental Technical Differences Between LC-MS and GC-MS

| Parameter | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Liquid (often mixtures of water with organic solvents like methanol or acetonitrile) | Inert gas (typically helium or hydrogen) |

| Separation Mechanism | Hydrophilic/hydrophobic interactions with stationary phase | Volatility and polarity interacting with stationary phase |

| Typical Ionization Sources | ESI, APCI | EI |

| Ionization Character | Soft ionization (often produces molecular ions) | Hard ionization (produces characteristic fragments) |

| Sample State | Dissolved in liquid solvent | Volatile or derivatized to become volatile |

| Chromatographic Column | Shorter columns (typically 50-150 mm) | Longer columns (typically 15-60 m) |

The choice between these platforms significantly influences the metabolomic workflow, from sample preparation requirements to data interpretation strategies. LC-MS has a broader application field for detecting substances such as lipids, amino acids, flavonoids, and anthocyanins, while GC-MS is particularly suitable for analyzing low polarity, low boiling point metabolites, or substances with volatility after derivatization [1].

Experimental Workflows: From Sample to Data

Sample Collection, Quenching, and Metabolite Extraction

Sample collection and preparation are critical steps in the metabolomics workflow that directly impact the quality and reliability of the resulting data. The choice of sample (cell, tissue, blood, urine, etc.) depends on the research question and metabolites of interest [2]. To minimize variability, it is preferred to collect samples at the same time of day, under similar conditions, and in a consistent manner. Samples should be processed as soon as possible to minimize changes in metabolite levels.

The first vital step in sample processing is the rapid quenching (enzymatic inhibition) of total metabolism, followed by the extraction of metabolites in such a way that the extract obtained should quantitatively reflect the endogenous metabolite levels originally present in the sample [2]. For living cells and tissue, which are metabolically active systems, quenching becomes particularly important (less so with biological fluids like blood, plasma, or urine). Several quenching methods exist, including flash freezing in liquid N₂, pouring liquid N₂ directly onto samples, using chilled methanol (-20°C or -80°C), and ice-cold PBS [2]. Quick quenching should be performed immediately after sample collection, as delays may result in deviation of the metabolic scenario from the one desired to be investigated.

Following quenching, organic solvent-based precipitation of proteins and extraction of metabolites occurs. Efficient sample processing is crucial to prevent degradation of labile metabolites and to achieve high-quality data. For non-targeted metabolomics, extraction methods must capture a broad range of metabolites, though the physicochemical diversity of metabolites makes this challenging [2]. A commonly used extraction method is liquid-liquid extraction, which relies on differential immiscibility of solvents. Polar, aqueous solutions are often paired with non-polar organic solvents such as chloroform to form a two-phase system, allowing the separation of polar and non-polar metabolites for subsequent analytical analysis [2].

Diagram 1: Sample Preparation Workflow for Metabolomics Analysis. This diagram illustrates the critical steps from sample collection through metabolic quenching to metabolite extraction, highlighting common methods and solvents used at each stage.

Platform-Specific Sample Preparation

LC-MS Sample Preparation: For LC-MS analysis, the extraction protocol often uses a ternary combination of hydrophilic (water) and lipophilic (isopropanol) solvents with acetonitrile as a medium polarity solvent [4]. To remove very lipophilic lipids that could accumulate in the injection interface and cause carry-over effects, a clean-up step after initial extraction and desiccation is recommended. Without this lipid clean-up step, derivatization reactions may be hampered for certain compound classes like amino acids and polyamines, particularly in postprandial blood plasma samples after lipid-rich meals [4].

GC-MS Sample Preparation: GC-MS requires an additional derivatization step to render compounds volatile enough for analysis. The most common derivatization protocol uses trimethylsilylation or variants like tert-butyldimethylsilylation, both of which remove acidic protons from hydroxyl-, carboxyl-, amino-, or thiol-groups [4]. These derivatization reactions are performed under mild conditions, work rapidly with high yields, break molecular proton bridge bonding, and consequently decrease boiling points while increasing compound stability for GC-MS analysis. While silylation reactions are more universal and easier to perform, some reports suggest complementary strategies such as using ethyl chloroformates [4].

Instrumental Analysis and Data Acquisition

LC-MS Instrumentation and Analysis: LC-MS systems have evolved from basic manual pumps and columns to sophisticated automated systems that provide precise control over chromatographic separations [5]. The development of ionization sources such as ESI, APCI, and Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI) has profoundly impacted LC-MS performance, facilitating the analysis of pharmaceutical compounds, including nonvolatile and polar or less polar molecules with lower molecular weights [5]. Mass analyzers commonly used in LC-MS include ion traps (ITs), quadrupoles (Q), Orbitrap, and time-of-flight (TOF) instruments, as well as hybrid systems offering high resolution, enhanced sensitivity, and superior mass accuracy across a wide dynamic range [5].

GC-MS Instrumentation and Analysis: GC-MS represents the most standardized method in metabolomics, with almost 50 years of established protocols for metabolite analyses [4]. The technology is considered a "gold standard" in metabolomics against which newer approaches should be compared with respect to breadth, sensitivity, and specificity of metabolite detections [4]. The electron ionization used in GC-MS leads to complex and rich fragmentation patterns which can be exploited to increase specificity in mass spectral matching, especially when using large user libraries with standardized protocols for data acquisition. Automated mass spectral deconvolution software (AMDIS) has been freely available for GC-MS since 1998 and has been successfully used for metabolomics since that time [4].

Diagram 2: Instrumental Analysis Pathways for LC-MS and GC-MS. This diagram illustrates the distinct analytical pathways for both platforms, highlighting the critical differences in separation mechanisms, ionization techniques, and the additional derivatization step required for GC-MS analysis of non-volatile compounds.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Direct comparisons of LC-MS and GC-MS performance reveal platform-specific advantages depending on the analyte characteristics. In a study comparing pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in surface water, HPLC-TOF-MS yielded lower detection limits than GC-MS for most compounds [6]. The detection limits ranged from 0.4 to 6 ng L⁻¹ for target compounds using the developed LC-MS/MS method, with recoveries for most compounds above 70% with relative standard deviation below 20% [7].

When comparing the analysis of hormones and pesticides in surface waters, both GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS demonstrated comparable performance for most compounds, with exceptions for specific analyte classes. GC-MS/MS outperformed LC-MS/MS for legacy organochlorine pesticides, such as DDT and its metabolites [7]. However, because of the very low water solubility of these compounds, they are less likely to be found in surface water samples. Conversely, LC-MS/MS enabled simultaneous analysis of highly water-soluble endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) such as estrogens and their conjugates with currently registered pesticides without the need for derivatization [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of LC-MS and GC-MS for Metabolite Analysis

| Performance Metric | LC-MS | GC-MS | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 10⁻¹⁵ mol [1] | 10⁻¹² mol [1] | General metabolomics applications |

| Detection Limits | 0.4-6 ng L⁻¹ for PPCPs [7] | Higher than LC-MS for most PPCPs [6] | Analysis of pharmaceuticals in water |

| Recovery Rates | >70% for most compounds [7] | Variable depending on compound volatility | Environmental sample analysis |

| Compound Coverage | Broad range including non-volatile, thermally labile, and high molecular weight compounds [1] | Volatile and semi-volatile compounds, or those renderable volatile via derivatization [1] | Untargeted metabolomics |

| Reproducibility | RSD <20% achievable [7] | High reproducibility with standardized libraries [4] | Inter-laboratory comparisons |

| Analysis Speed | 2-5 minutes per sample with UHPLC-MS [5] | Generally longer run times due to temperature programming | High-throughput applications |

Application-Specific Performance

The optimal platform choice heavily depends on the specific analytical application and compound classes of interest. GC-MS is ideal for identifying and quantitating small molecular metabolites (<650 daltons), including small acids, alcohols, hydroxyl acids, amino acids, sugars, fatty acids, sterols, catecholamines, drugs, and toxins, often using chemical derivatization to make these compounds volatile enough for gas chromatography [4]. The mature nature of GC-MS technology is evidenced by comprehensive spectral libraries such as the NIST14 library, which comprises GC-MS mass spectra for 242,477 unique compounds, roughly one-third with recorded standardized retention times [4].

LC-MS offers distinct advantages for different compound classes. It has a broader application field, especially due to its wide range of detectable substances such as lipids, amino acids, flavonoids, and anthocyanins, with significantly higher sensitivity compared to other detection techniques [1]. The capacity of LC-MS to multiplex several analytes within a single analytical run with minimal incremental cost represents another significant advantage for targeted analyses [1].

Data Processing, Analysis, and Visualization

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics generates extensive datasets that require specific data exploration skills to identify and visualize statistically significant trends and biologically relevant differences [8]. Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC) are critical components in metabolomics, ensuring the reliability, reproducibility, and integrity of data [2]. The Metabolomics Quality Assurance and Quality Control Consortium (mQACC) is a collaborative effort dedicated to defining and advancing best practices in QA and QC within metabolomics [2].

A common approach involves using quality control samples obtained by pooling small aliquots of all biological samples or purchased reference materials [8]. These QCs are instrumental for evaluating data quality, providing insight into technical variability, and normalizing data to remove batch effects [8]. Missing value management represents another critical step in data preprocessing, with strategies including imputation by constant value (e.g., percentage of the lowest concentration), k-nearest neighbors (kNN) algorithm, or random forest methods [8].

Statistical Analysis and Visualization Strategies

Effective data visualization is crucial at every stage of the metabolomics workflow, providing core components of data inspection, evaluation, and sharing capabilities [9] [10]. For untargeted LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics, visualization strategies include scatter plots, boxplots, cluster heatmaps, and network visualizations that help researchers navigate complex datasets and gain specific insights [9].

Volcano plots provide a snapshot view of treatment impacts and affected metabolites, while dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) help visualize sample clustering and outliers [8]. For lipidomics data, specialized visualizations including lipid maps and fatty acyl chain plots effectively represent the complex relationships within lipid classes [8]. The field has seen the development of numerous computational tools and platforms, including MetaboAnalyst, LipidSig, and LipidMaps Statistical Analysis Tool, which facilitate data exploration through user-friendly interfaces [8].

Diagram 3: Metabolomics Data Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in processing and interpreting metabolomics data, from raw data preprocessing through statistical analysis to biological interpretation and visualization.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolomics Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Metabolite extraction, protein precipitation, quenching agent | Often used in combination with chloroform or water for biphasic extraction [2] |

| Chloroform | Lipid extraction, non-polar metabolite separation | Component of Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods for lipid extraction [2] |

| MTBE (Methyl tert-butyl ether) | Lipid extraction, particularly for lipophilic metabolites | Non-polar solvent with high affinity for lipids [2] |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA, BSTFA) | Render metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis | Trimethylsilylation reagents remove acidic protons from functional groups [4] |

| Internal Standards (isotope-labeled) | Quantification reference, compensation for technical variability | Should have similar chemical properties to target metabolites [2] |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase modifier for LC-MS | Improves ionization efficiency in positive ion mode [6] |

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate | Mobile phase buffers for LC-MS | Provides consistent ionization conditions, especially in negative ion mode |

| Quality Control Materials (e.g., NIST SRM 1950) | Method validation, inter-laboratory comparison | Standard reference material for plasma metabolomics [8] |

The choice between LC-MS and GC-MS for metabolomics research depends primarily on the specific research questions, target metabolite classes, and available resources. GC-MS remains the gold standard for analyzing volatile compounds and those that can be rendered volatile through derivatization, leveraging extensive spectral libraries and standardized protocols [4]. Its rich fragmentation patterns provide structural information that facilitates compound identification. LC-MS offers broader coverage of metabolite classes, particularly non-volatile, thermally labile, and high molecular weight compounds, with superior sensitivity and without the need for derivatization [1].

For comprehensive metabolomic coverage, many laboratories implement both platforms in complementary approaches. The continuous advancement of both technologies, including improvements in mass analyzer design, ionization efficiency, and chromatographic resolution, ensures that both LC-MS and GC-MS will remain indispensable tools in the metabolomics workflow. By understanding their respective strengths and limitations, researchers can optimize their analytical strategies to extract maximum biological insight from complex metabolic systems.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) has become a cornerstone technique for metabolite analysis, particularly valued for its ability to characterize a wide range of biologically relevant molecules. Its core technological strength lies in the synergistic combination of liquid chromatography separation and soft ionization techniques, which together enable the sensitive analysis of non-volatile, thermally labile, and high-molecular-weight compounds that are prevalent in biological systems [11] [12]. This technical profile examines these foundational technologies and positions LC-MS within the broader analytical context by comparing it with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), another premier analytical technique.

While both LC-MS and GC-MS integrate chromatography with mass spectrometry to separate, identify, and quantify chemicals in complex mixtures, they differ fundamentally in their operational principles and application domains [11]. GC-MS employs a gas mobile phase and requires sample vaporization, making it ideal for volatile and semi-volatile compounds. In contrast, LC-MS uses a liquid mobile phase and softer ionization methods, making it uniquely suitable for analyzing pharmaceuticals, proteins, metabolites, and other compounds that cannot withstand the high temperatures required for vaporization in GC-MS [11] [12]. Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to select the optimal technology for their specific analytical challenges in drug development and metabolic research.

Core Technology Breakdown: Liquid Chromatography Separation

The liquid chromatography component of LC-MS serves as the critical front-end separation system that resolves complex biological samples into individual components before mass analysis. This separation occurs through differential partitioning of analytes between a stationary phase (typically hydrophobic C18 particles packed into a column) and a liquid mobile phase that is pumped through the system at high pressure [12].

The separation mechanism leverages the varying degrees of interaction between different metabolites and the stationary phase. Retention time - the time taken for a compound to elute from the column - serves as a key identifying characteristic that is influenced by multiple factors including compound polarity, molecular structure, and mobile phase composition [13]. In modern metabolomics, retention time has proven particularly valuable for distinguishing between isomeric candidate structures when combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry data, providing an orthogonal dimension for compound identification [13].

Recent advances have focused on improving the predictability and reproducibility of chromatographic separations. Approaches include experimental projection methods that translate retention times between different chromatographic systems, and machine learning models that predict retention behavior from molecular structure [13]. The similarity between chromatographic systems - particularly regarding column chemistry and mobile phase pH - has been identified as a crucial factor affecting the accuracy of these predictive approaches [13].

Core Technology Breakdown: Soft Ionization Techniques

Soft ionization represents the second critical technological pillar of LC-MS, enabling the transformation of liquid-phase separated compounds into gas-phase ions suitable for mass analysis without extensive fragmentation. The predominant soft ionization techniques in LC-MS are Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), with ESI being particularly widely adopted in metabolomics applications [12].

ESI operates by applying a high voltage to a liquid stream as it exits a capillary, creating a fine aerosol of charged droplets. As the solvent evaporates, the charge concentration increases until the Rayleigh limit is reached, leading to Coulombic fission and ultimately producing gas-phase ions [2]. This process gently transfers pre-existing ions from solution to the gas phase and can also promote ionization through adduct formation (e.g., with sodium, ammonium, or protons). The "soft" nature of this technique preserves molecular integrity, allowing the detection of intact molecular ions with minimal fragmentation, which is crucial for accurate molecular weight determination and structural characterization [12].

The flexibility in ionization techniques allows researchers to tailor LC-MS methods to specific compound classes. ESI is particularly effective for polar compounds and molecules that already exist as ions in solution, while APCI can handle less polar compounds and offers enhanced compatibility with higher flow rates and a broader range of mobile phase compositions [12]. This adaptability makes LC-MS suitable for analyzing diverse metabolite classes with varying chemical properties.

LC-MS versus GC-MS: Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies reveal distinct performance characteristics and application boundaries for LC-MS and GC-MS technologies. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical platform for specific research questions in metabolite analysis.

Table 1: Technical and Performance Comparison Between LC-MS and GC-MS

| Parameter | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Liquid (solvents/buffers) | Gas (helium, hydrogen) [11] |

| Sample State | Liquid, minimal preparation | Must be volatile and thermally stable [11] |

| Typical Analytes | Non-volatile, thermally labile, polar, high molecular weight compounds [12] | Volatile, semi-volatile, thermally stable compounds [11] |

| Derivatization Requirement | Generally not required | Often required for non-volatile compounds [12] |

| Ionization Techniques | ESI, APCI (soft ionization) [12] | EI (hard ionization), CI |

| Typical Detection Limits | Lower for many pharmaceuticals and PPCPs [6] | Varies by compound; can be higher for some analytes [6] |

| Operational Costs | Higher initial investment and maintenance [12] | More affordable operation and maintenance [11] |

A comparative study analyzing pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in water samples demonstrated that HPLC-TOF-MS (a form of LC-MS) generally yielded lower detection limits than GC-MS for the compounds studied [6]. This enhanced sensitivity for certain compound classes makes LC-MS particularly valuable in applications requiring trace-level detection.

For metabolomic studies, each technique offers complementary coverage of the metabolome. GC-MS is limited to volatile compounds or those that can be made volatile through derivatization, while LC-MS can analyze a much broader range of metabolites without chemical modification [14]. This distinction was evident in a study of lupus nephritis patients, where the combined application of both GC/MS and LC/MS enabled the identification of 41 potential metabolic biomarkers, providing a more comprehensive metabolic profile than either technique could achieve alone [14].

Table 2: Application-Based Technique Selection Guide

| Research Application | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Metabolism Studies | LC-MS | Ideal for polar metabolites, conjugates, and thermally labile compounds [12] |

| Volatile Compound Profiling | GC-MS | Excellent for essential oils, fuels, solvents [11] |

| Lipidomics | LC-MS | Superior for intact lipids, phospholipids [2] |

| Environmental Pollutant Analysis | Both (compound-dependent) | GC-MS for VOCs/PAHs; LC-MS for pesticides/PPCPs [6] |

| Forensic Toxicology | Both (complementary) | GC-MS for traditional drugs; LC-MS for polar metabolites [11] |

| Protein/Peptide Analysis | LC-MS | Handles high molecular weight biomolecules [12] |

| Metabolomics Discovery | Both (complementary) | Combined approach maximizes metabolome coverage [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LC-MS Metabolomic Workflow Protocol

A standardized workflow is essential for generating reliable and reproducible LC-MS metabolomic data. The following protocol, adapted from current metabolomic research, outlines the key steps from sample preparation to data analysis [2]:

Sample Collection and Quenching: Collect biological samples (cells, tissue, blood, urine) using sterile techniques. Immediately quench metabolism through flash freezing in liquid N₂ or using chilled methanol (-20°C to -80°C) to preserve the metabolic profile at the time of collection [2].

Metabolite Extraction: Employ liquid-liquid extraction with appropriate solvent systems. For comprehensive metabolite coverage, use biphasic systems like methanol/chloroform/water (typical ratios 1:1:0.5) to simultaneously extract polar (methanol/water phase) and non-polar metabolites (chloroform phase) [2]. Add internal standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds) at known concentrations prior to extraction to correct for technical variability [2].

Chromatographic Separation: Inject extracts onto a reversed-phase UHPLC system. Use a C18 column (e.g., 150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 µm) maintained at 35-45°C. Employ a binary gradient with mobile phase A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). A typical gradient runs from 5% B to 95% B over 10-20 minutes, followed by column re-equilibration [6] [14].

Mass Spectrometric Analysis: Operate the mass spectrometer in either positive or negative electrospray ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3-4 kV. Use high-resolution mass analyzers (Orbitrap or TOF) for accurate mass measurement. Data-dependent MS/MS acquisition can be implemented for compound identification [14].

Data Processing: Extract features using specialized software (e.g., MassCube, XCMS, MS-DIAL) that perform peak detection, alignment, and normalization [15]. Apply quality control measures including pooled quality control samples and internal standards to monitor and correct for instrumental drift [16].

Combined LC-MS/GC-MS Metabolomic Analysis

For comprehensive metabolomic coverage, a combined approach using both LC-MS and GC-MS can be implemented as demonstrated in clinical research [14]:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolite Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol/Chloroform (2:1) | Biphasic extraction of polar and non-polar metabolites [2] | Comprehensive metabolite extraction from tissues, cells |

| L-2-chlorophenylalanine | Internal standard for data normalization [14] | Correcting technical variability in LC-MS and GC-MS |

| Methoxyamine hydrochloride | Derivatization agent for GC-MS analysis | Protecting carbonyl groups before silylation |

| BSTFA (with 1% TMCS) | Silylation derivatization agent | Increasing volatility for GC-MS analysis |

| Formic acid | Mobile phase additive | Improving ionization efficiency in LC-MS |

| C18 SPE disks | Solid-phase extraction | Concentrating analytes from liquid samples |

Sample Preparation for Combined Analysis:

- LC-MS Analysis: Add internal standard to serum, then precipitate proteins with cold methanol-acetonitrile (2:1). After centrifugation, filter supernatant through 0.22 µm membrane prior to LC-MS analysis [14].

- GC-MS Analysis: Add internal standard to serum, extract with methanol, then derivatize using methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine (37°C, 90 min) followed by BSTFA with 1% TMCS (70°C, 60 min) [14].

Instrumental Analysis:

- LC-MS: Utilize reversed-phase chromatography with gradient elution and positive/negative ESI switching coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry.

- GC-MS: Employ capillary GC with optimized temperature programming and electron ionization (70 eV) mass spectrometry [14].

Data Integration: Process data from both platforms separately, then combine annotated features for multivariate statistical analysis and pathway mapping.

Diagram 1: LC-MS Metabolomic Analysis Workflow. The process begins with sample collection and proceeds through critical preparation and analysis stages.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

LC-MS technology continues to evolve, with emerging applications leveraging its core strengths in liquid-phase separation and soft ionization. In pharmaceutical analysis, LC-MS is indispensable throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial candidate screening and metabolite identification to pharmacokinetic studies and quality control [12]. The technology's ability to detect and quantify trace levels of drugs and their metabolites in complex biological matrices with high specificity makes it particularly valuable for therapeutic drug monitoring and toxicity studies.

In clinical metabolomics, LC-MS enables the discovery of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for various diseases. The lupus nephritis study exemplifies this application, where LC-MS analysis revealed metabolic perturbations associated with disease pathogenesis, including alterations in energy metabolism, oxidative stress responses, and gut microbiome-derived metabolites [14]. Such findings provide insights into disease mechanisms and identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Future developments in LC-MS technology focus on enhancing separation efficiency through ultra-high performance systems, improving detection sensitivity with advanced mass analyzers, and increasing analytical throughput for large-scale epidemiological studies. Computational approaches for data processing, such as the MassCube platform, are addressing challenges in feature detection, annotation, and quantification, particularly for large datasets [15]. These advancements will further establish LC-MS as a cornerstone technology for metabolite analysis across diverse research fields including systems biology, personalized medicine, and environmental science.

LC-MS provides researchers with a powerful analytical platform characterized by exceptional versatility in analyzing diverse metabolite classes, high sensitivity for trace-level detection, and minimal requirement for sample derivatization. While GC-MS remains superior for volatile compound analysis and offers more economical operation, LC-MS extends analytical capabilities to encompass the vast chemical space of non-volatile and thermally labile metabolites that are inaccessible to GC-MS. The complementary nature of these techniques means that strategic selection or combined implementation based on specific research objectives delivers the most comprehensive insights into metabolic systems, ultimately advancing drug development and biomedical research.

In the field of metabolomics research, the selection of an appropriate analytical platform is fundamental to the success of any study. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) represent two of the most prominent technologies, each with distinct operational principles and application domains [1]. GC-MS is characterized by its use of a gas mobile phase for high-resolution separation and its reliance on hard ionization to generate highly reproducible, fragment-rich spectra. In contrast, LC-MS employs a liquid mobile phase and soft ionization, which preferentially preserves the molecular ion [17] [18]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these platforms, focusing on the core technology of GC-MS to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles and Instrumental Configuration

The fundamental differences between GC-MS and LC-MS begin with their separation mechanisms and extend to their ionization techniques, defining the scope of metabolites they can detect.

Gas Chromatography (GC) Separation: In GC-MS, the mobile phase is an inert gas, such as helium or nitrogen. Separation occurs within a long, heated capillary column as analytes are vaporized and transported by the gas stream [1] [17]. The separation is based on the compound's volatility and its interaction with the stationary phase of the column. Temperature programming is critical, as gradually increasing the oven temperature allows for the effective elution and separation of compounds with different boiling points [1].

Liquid Chromatography (LC) Separation: LC-MS uses a liquid mobile phase (e.g., a mixture of water and organic solvents like acetonitrile or methanol) that is pumped at high pressure through a shorter column packed with fine particles [1] [19]. Separation primarily depends on the polarity and affinity of the analytes for the stationary phase compared to the mobile phase. The most common mode, reversed-phase chromatography, retains non-polar compounds longer, while a technique called Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) is used to separate polar metabolites [17] [19].

Ionization: Hard vs. Soft: The ionization techniques used are a defining differentiator. GC-MS typically uses Electron Ionization (EI), a "hard" ionization method. In the EI source, analytes are bombarded with high-energy electrons (usually 70 eV), which causes them to fragment into a characteristic pattern of ions [1] [18]. LC-MS, on the other hand, uses "soft" ionization techniques like Electrospray Ionization (ESI) or Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI). These methods impart less energy, primarily generating intact molecular ions (e.g., [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻) with little fragmentation [1] [20] [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Operational Principles of GC-MS and LC-MS

| Feature | GC-MS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Inert gas (e.g., Helium) [1] [3] | Liquid solvents (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol) [1] [3] |

| Separation Principle | Volatility & boiling point [17] [18] | Polarity & chemical affinity [17] [18] |

| Typical Ionization | Electron Impact (EI) [1] [18] | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [1] [18] |

| Ionization Character | Hard (extensive fragmentation) [1] [18] | Soft (minimal fragmentation; intact molecular ion) [1] [20] |

Diagram 1: Simplified GC-MS analytical workflow.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The technical differences between the platforms translate directly into distinct performance characteristics, which can be evaluated through sensitivity, compound coverage, and identification capabilities.

Analytical Sensitivity and Dynamic Range

Sensitivity is a key metric for any analytical platform. LC-MS generally offers exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting compounds at concentrations as low as 10⁻¹⁵ mol (femtogram level) [1]. This makes it particularly powerful for targeted bioanalysis where trace levels of compounds must be measured [18]. GC-MS is also highly sensitive, typically operating in the 10⁻¹² mol (picogram) range [1]. A comparative study of benzodiazepine analysis in urine found that both LC-MS/MS and GC-MS produced highly accurate and precise results at concentrations around 100 ng/mL, demonstrating their comparable reliability for quantitative analysis at this level [20].

Metabolite Coverage and Compound Suitability

The scope of metabolites each platform can analyze is largely determined by the physical and chemical properties of the compounds.

GC-MS Domain: GC-MS is ideally suited for volatile and semi-volatile, thermally stable compounds with molecular weights typically under 500 Da [18]. This includes metabolites such as fatty acids, organic acids, alcohols, essential oils, and environmental pollutants [1] [18]. Many non-volatile metabolites (e.g., sugars, amino acids) can be analyzed by GC-MS only after chemical derivatization to increase their volatility and thermal stability [1] [17] [19].

LC-MS Domain: LC-MS has a much broader application range, capable of analyzing non-volatile, polar, ionic, and thermally labile compounds without derivatization [1] [3]. It can handle a wide range of molecular weights, from small polar metabolites to large biomolecules like peptides and proteins [18]. This makes it the platform of choice for lipids, amino acids, flavonoids, anthocyanins, pharmaceuticals, and most biomolecules found in biological fluids [1] [21].

Table 2: Analytical Performance and Application Scope

| Performance Metric | GC-MS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | ~10⁻¹² mol [1] | ~10⁻¹⁵ mol [1] |

| Ideal Compound Types | Volatile, thermally stable, low-MW [18] | Non-volatile, polar, thermally labile, wide MW range [3] [18] |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires derivatization [17] [19] | Typically minimal; dilution or simple extraction [20] |

| Key Strength | Excellent for structural isomers; robust libraries [18] | Broad metabolite coverage; ideal for biofluids [1] [18] |

Compound Identification and Database Support

Confident identification of unknown metabolites is a critical step. GC-MS benefits from decades of development, resulting in highly standardized and reproducible EI mass spectra [18]. These spectra are largely independent of the instrument brand, allowing them to be matched against extensive, universal libraries like the NIST and Wiley databases, which contain hundreds of thousands of spectra [17] [18]. This provides a high level of confidence in identifications.

In LC-MS, the soft ionization spectra are highly dependent on the instrument and specific settings (e.g., collision energy) [22]. Identification relies on a combination of accurate mass, retention time, and MS/MS fragmentation patterns, which are compared to smaller, often instrument-specific, spectral libraries (e.g., METLIN, MassBank) [17]. While powerful, the process can be more complex and less standardized than with GC-MS.

Experimental Protocols and Comparative Data

To illustrate the practical differences, the following section details specific experimental methodologies and results from comparative studies.

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Benzodiazepines

A 2016 study directly compared LC-MS/MS and GC-MS for the urinalysis of five benzodiazepines [20].

- Sample Preparation:

- Instrumental Analysis:

- GC-MS: An Agilent 7890 GC/5975 MS with an HP-ULTRA 1 column was used. Helium was the carrier gas [20].

- LC-MS/MS: Not specified in the excerpt, but typically uses a C18 column with a gradient of water and acetonitrile, often with formic acid as an additive.

- Results: Both methods showed excellent and comparable accuracy (99.7-107.3%) and precision (<9% coefficient of variation) for quality control samples. The study concluded that the simpler and faster sample preparation of LC-MS/MS made it a suitable alternative, though it noted issues like ion suppression that required careful management with deuterated internal standards [20].

Experimental Protocol: Analysis of Propofol Metabolites

A comprehensive study on propofol metabolites in urine highlighted the complementary nature of both techniques [23].

- GC-MS Sample Prep: Required acid hydrolysis, liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), and trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatization [23].

- LC-MS Sample Prep: Used simpler dilution or solid-phase extraction [23].

- Key Findings: The LC-MS method provided a shorter total analysis time and was highly sensitive for phase II metabolites (e.g., glucuronides). Conversely, the GC-MS method provided better separation and easier identification of the parent propofol and its phase I metabolites, as the EI spectra produced structurally characteristic fragment ions [23]. This demonstrates how the techniques can be used in tandem for a more complete metabolic picture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful metabolomics analysis requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MTBSTFA, TMS) | Increases volatility and thermal stability of non-volatile metabolites for GC-MS analysis [20] [23]. | GC-MS sample preparation [20]. |

| Deuterated Internal Standards (e.g., Drug-d5) | Accounts for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency; enables accurate quantification [20] [2]. | LC-MS/MS and GC-MS quantitation [20]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Selectively purifies and concentrates analytes from complex biological matrices like urine or plasma [20]. | Sample clean-up in both GC-MS and LC-MS [20]. |

| β-Glucuronidase Enzyme | Hydrolyzes glucuronide-conjugated metabolites to release the aglycone for analysis [20]. | Sample hydrolysis in GC-MS protocols [20]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | High-purity solvents used as mobile phase components to minimize background noise and ion suppression. | LC-MS mobile phase preparation [19]. |

Diagram 2: A decision guide for selecting between GC-MS and LC-MS.

GC-MS and LC-MS are not competing technologies but rather complementary pillars of modern metabolomics. The core strength of GC-MS lies in its high-resolution gas chromatography separation and hard EI ionization, which provides superior and reproducible fragmentation for confident identification of volatile and derivatized compounds. LC-MS excels with its unparalleled breadth in analyzing diverse, non-volatile metabolites with high sensitivity and minimal sample preparation. The choice between them is not about which is superior, but which is the right tool for the specific analytical challenge. For a comprehensive metabolic profile, the most powerful approach is often to leverage both platforms in tandem [18] [23].

In the field of analytical chemistry, the coupling of separation techniques with mass spectrometry has revolutionized our ability to identify and quantify chemical compounds in complex mixtures. The fundamental challenge in this integration lies in the efficient ionization of analyte molecules after chromatographic separation but before mass analysis. This article focuses on three predominant ionization techniques: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) for Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), and Electron Impact (EI) for Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The choice of ionization method is not merely a technical detail but a critical determinant of the success of an analytical method, influencing factors such as the range of detectable compounds, the quality of structural information obtained, and the overall sensitivity and robustness of the analysis. Within the broader context of comparing LC-MS and GC-MS for metabolite analysis research, understanding these ionization sources is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize their analytical workflows [1] [18].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Electron Impact (EI) in GC-MS

Electron Impact (EI) is a hard ionization technique conducted in a high-vacuum environment. The process begins when a tungsten or rhenium-tungsten filament is heated, emitting a beam of high-energy electrons. These electrons are accelerated to a standard energy of 70 electron volts (eV). When analyte molecules, which have been vaporized by the GC inlet, enter the path of this electron beam, they are bombarded by these high-energy electrons. This collision typically results in the ejection of an electron from the analyte molecule, creating a positively charged molecular ion (M⁺•). The key characteristic of EI is that the 70 eV energy transferred significantly exceeds the energy required for simple ionization, causing the molecular ions to become vibrationally excited and subsequently fragment into smaller, characteristic ions. This fragmentation pattern, while often leading to the diminution or complete loss of the molecular ion signal, provides a rich and reproducible "fingerprint" that is invaluable for structural elucidation and library matching [24] [25].

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) in LC-MS

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that occurs at atmospheric pressure and is ideal for polar, thermally labile, and high-molecular-weight compounds. In ESI, the LC eluent containing the analytes is pumped through a narrow capillary to which a high voltage (typically 3-5 kV) is applied. This results in the formation of a fine aerosol of charged droplets at the capillary tip. As the solvent in these droplets evaporates, assisted by a flow of warm nitrogen (drying gas), the droplets shrink and the charge density on their surface increases. Through mechanisms believed to involve either droplet fission (the Coulombic explosion) or ion evaporation, the analyte molecules are ultimately released as gas-phase ions. ESI primarily produces protonated ([M+H]⁺) or deprotonated ([M-H]⁻) molecules, or other pre-charged species, with minimal fragmentation. This makes ESI excellent for determining molecular weights but less informative for direct structural analysis without subsequent tandem MS (MS/MS) experiments [1] [12] [26].

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) in LC-MS

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) is another soft ionization technique that, like ESI, operates at atmospheric pressure but employs a different mechanism. In APCI, the LC eluent is first nebulized into a fine mist and vaporized in a heated tube (typically at 400-500°C) to create a gas-phase plume. A corona discharge needle then emits a stream of electrons, which ionizes the nebulizer gas (typically N₂) and solvent molecules in the air, initiating a cascade of ion-molecule reactions. These reagent ions subsequently collide with and transfer charge to the analyte molecules through chemical ionization processes, most commonly leading to proton transfer and the formation of [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻ ions. Because APCI relies on the analyte being in the gas phase, it is better suited for less polar, thermally stable, and low- to medium-molecular-weight compounds compared to ESI. It generally produces simpler spectra than EI but can exhibit some in-source fragmentation, such as the loss of water or carbon monoxide [27] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and ionization mechanisms for the three techniques:

Comparative Performance Data

The selection of an appropriate ionization source is guided by the physicochemical properties of the target analytes and the required analytical outcomes. The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics based on experimental data.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Ionization Source Performance in Analytical Applications

| Performance Metric | EI (GC-MS) | APCI (LC-MS) | ESI (LC-MS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity (mol) | 10⁻¹² [1] | Varies with compound | 10⁻¹⁵ [1] |

| Recovery (in nitrosamine analysis) | 108.66 ± 9.32% [28] | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified |

| Precision (RSD in nitrosamine analysis) | < 6% [28] | Data not fully specified | Data not fully specified |

| Matrix Effect (in pesticide analysis) | Not applicable (GC context) | Less susceptible to suppression [26] | More susceptible to ion suppression [26] |

| LOD for Pesticides (in cabbage) | Not applicable (GC context) | Higher LOD for most compounds [26] | Lower LOD for most compounds [26] |

Table 2: Analytical Characteristics and Applicability of Ionization Sources

| Characteristic | EI (GC-MS) | APCI (LC-MS) | ESI (LC-MS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Mechanism | High-energy electron bombardment [24] | Chemical ionization at atmospheric pressure [27] | Charge residue or ion evaporation [1] |

| Ionization Environment | High vacuum [24] | Atmospheric pressure [27] | Atmospheric pressure [1] |

| Primary Ions Formed | Fragment ions, M⁺• (can be weak) [25] | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻, M⁺• (sometimes) [27] | [M+H]⁺, [M-H]⁻, multiply charged ions [1] |

| Fragmentation Level | High ("hard" ionization) [18] | Low to moderate ("soft" ionization) [27] | Very low ("soft" ionization) [18] |

| Ideal Compound Types | Volatile, thermally stable, low polarity [18] | Low-medium polarity, semi-volatile, thermally stable [27] [26] | Polar, ionic, thermally labile, high MW [12] [18] |

| Library Searchability | Excellent (NIST, Wiley libraries) [18] | Poor | Poor |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Analysis of Nitrosamines Using EI-GC-MS/MS

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing ionization techniques for the analysis of nine nitrosamines eluted from synthetic resins into artificial saliva [28].

- Sample Preparation: Nitrosamines are extracted from rubber-type products (e.g., pacifiers, bottle nipples) by immersion in artificial saliva. The artificial saliva serves as a physiologically relevant extraction solvent to mimic human exposure.

- Chromatography (GC): Separation is achieved using a gas chromatograph equipped with a capillary column. The specific column and temperature program are optimized for the resolution of the nine target nitrosamines.

- Ionization (EI): The GC effluent is introduced into a high-vacuum EI ion source. Ionization is performed with a standard 70 eV electron energy. The filament current and source temperature are set according to the manufacturer's specifications.

- Mass Analysis (MS/MS): Detection and quantification are performed using a tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS). The instrument operates in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode, where specific precursor ion → product ion transitions are monitored for each nitrosamine to achieve high selectivity and sensitivity.

- Validation Parameters: The method is validated by assessing linearity, limit of detection (LOD), recovery, and precision. In the cited study, EI-GC-MS/MS demonstrated an average recovery of 108.66% with a precision of < 6% RSD, outperforming APCI- and ESI-LC-MS/MS methods for this application [28].

Protocol 2: Multiresidue Pesticide Analysis in Food Comparing ESI and APCI

This protocol is derived from a study evaluating the efficiency of ESI and APCI for the analysis of 22 pesticide residues in a cabbage matrix [26].

- Sample Preparation: The QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method is employed. Cabbage samples are homogenized, and pesticides are extracted with acetonitrile. The extract is then cleaned up using dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) with sorbents like PSA (primary secondary amine) to remove interfering compounds.

- Chromatography (LC): Separation is carried out using a high-performance liquid chromatograph with a reversed-phase C18 column. A gradient elution with water and acetonitrile (both often modified with acids like formic acid) is used to separate the diverse pesticide compounds.

- Ionization (ESI & APCI): The LC effluent is directed to either an ESI or APCI source. For ESI, parameters such as capillary voltage, nebulizer gas pressure, and drying gas temperature are optimized. For APCI, the vaporizer temperature and corona discharge needle current are critical parameters. The study optimized these for all 22 pesticides in positive ion mode.

- Mass Analysis (MS/MS): A triple quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in MRM mode is used for detection.

- Method Comparison: Key validation parameters, including linearity, LOD, matrix effect, accuracy, and precision, are determined for both sources. The study concluded that while APCI was less affected by matrix-induced ion suppression, ESI provided lower LODs for most of the pesticides analyzed [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the aforementioned experimental protocols requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components for these analytical workflows.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for LC-MS and GC-MS Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Saliva | Physiologically relevant extraction solvent | Simulating oral exposure to nitrosamines from rubber products [28]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | Streamlined sample preparation for multi-residue analysis | Extracting and cleaning up pesticide residues from complex food matrices like cabbage [26]. |

| PSA (Primary Secondary Amine) | d-SPE sorbent for clean-up | Removing fatty acids and other polar organic acids from food extracts during QuEChERS [26]. |

| DB-5MS GC Column | (5%-Phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane GC column | Standard non-polar/low-polarity column for separating semi-volatile analytes like nitrosamines [28]. |

| C18 LC Column | Reversed-phase LC column | Separating a wide range of analytes by hydrophobicity, from pesticides to pharmaceuticals [26]. |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase additive | Promoting protonation of analytes in positive ion mode ESI and APCI LC-MS to improve sensitivity [26]. |

| Calibration Standards | Instrument calibration and quantification | Creating calibration curves for accurate quantification of target analytes, essential for both GC-MS and LC-MS [28] [26]. |

Application Scenarios and Decision Framework

The choice between EI, ESI, and APCI is fundamentally guided by the nature of the analyte and the analytical question. The following decision workflow visualizes the key considerations for selecting the appropriate ionization source:

GC-MS with EI is the undisputed choice for volatile and thermally stable metabolites. Its strengths are highlighted in analyzing essential oils, environmental pollutants (VOCs, PAHs), fatty acids, and drugs of abuse [18]. The ability to generate reproducible, library-searchable spectra makes it powerful for identifying unknown compounds within its applicable chemical space.

LC-MS with ESI dominates the analysis of polar, ionic, and thermally labile molecules that are incompatible with GC. It is the workhorse for biomarker discovery, pharmaceutical analysis, proteomics, and metabolomics of polar compounds in biological fluids like plasma and urine [12] [18]. Its capacity to form multiply charged ions allows for the analysis of large biomolecules far beyond the mass range of GC-MS.

LC-MS with APCI serves as a crucial complementary technique to ESI. It extends the reach of LC-MS to less polar, semi-volatile metabolites that may ionize poorly by ESI, such as certain steroids, carotenoids, and lipids [27] [18]. A key operational advantage is its generally lower susceptibility to matrix effects compared to ESI, making it more robust for analyzing dirty samples [26].

Electron Impact (EI), Electrospray Ionization (ESI), and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) are foundational ionization techniques, each with a distinct and non-overlapping role in a modern analytical laboratory. EI-GC-MS provides unparalleled structural information and library-based identification for volatile compounds. ESI-LC-MS offers exceptional sensitivity and a broad application range for polar and high-molecular-weight analytes, particularly in biological matrices. APCI-LC-MS acts as a vital bridge, handling less polar compounds and offering greater robustness against matrix effects. The choice is not about finding a single "best" technique but about selecting the right tool for the specific analytical challenge. For a comprehensive metabolomics research program, GC-MS/EI and LC-MS/ESI/APCI should be viewed as complementary, and an ideal strategy often involves leveraging the strengths of both platforms to achieve maximum coverage of the metabolome [18].

The comparison between Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) for metabolomics research often focuses on the analytical instrumentation itself. However, the critical determinant for success or failure in metabolite analysis lies in the preliminary steps of sample preparation, specifically the choice of extraction solvents and the requirement for chemical derivatization. These preparatory steps are not merely preliminary; they fundamentally define which segments of the metabolome will be accessible for detection and quantification. This guide objectively compares the performance of LC-MS and GC-MS through the lens of these sample preparation protocols, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The goal of metabolomics is the comprehensive analysis of all small-molecule metabolites (<1500 Da) in a biological system [29] [2]. The chemical diversity of these metabolites—ranging from highly polar amino acids and sugars to non-polar lipids—presents a profound analytical challenge. No single analytical platform can capture the entire metabolome without bias, making the initial sample preparation a critical point of strategic decision-making.

Sample preparation directly influences the reliability, reproducibility, and coverage of metabolomic data [2]. It involves the crucial steps of quenching metabolic activities, extracting metabolites from the biological matrix, and potentially derivatizing them to make them amenable to analysis. The efficiency of these steps determines the accuracy with which the final data reflects the original metabolic state of the sample. Inadequate preparation can lead to the irreversible loss of labile metabolites, introduction of artifacts, or matrix effects that suppress ionization, thereby compromising the entire experiment [29] [30]. The fundamental divergence between LC-MS and GC-MS workflows often begins at this very first stage, dictating the specific chemical space each platform can effectively probe.

Comparison of Extraction Solvents for LC-MS and GC-MS

The selection of extraction solvents is a primary differentiator between LC-MS and GC-MS protocols, as it determines the classes of metabolites that will be recovered from a complex biological matrix.

Extraction for LC-MS Analysis

LC-MS is renowned for its ability to handle a broad spectrum of metabolite polarities. Consequently, its sample preparation often employs liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) to separate metabolites based on their differential solubility in immiscible solvents [2]. A biphasic system, such as the classical methanol/chloroform/water mixture, is widely used to simultaneously extract polar and non-polar metabolites. In this system, polar metabolites (e.g., sugars, amino acids) partition into the methanol/water phase, while non-polar lipids dissolve in the chloroform phase [2]. This approach was effectively employed in a recent lupus nephritis study, where a simple protein precipitation protocol using a methanol-acetonitrile mixture was sufficient to prepare serum for a comprehensive untargeted LC-MS analysis [14].

The pH of the extraction solvent can be strategically manipulated to improve the recovery of specific metabolite classes. By varying the pH, researchers can take advantage of the acid-base chemistry of metabolites, significantly enhancing the extraction of certain classes from biofluids or cells [2]. For robust quantification, isotopically labeled internal standards are added to the extraction solvent at known concentrations before sample processing. These standards correct for variability in extraction efficiency, ionization suppression, and other matrix effects, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reproducibility of the data [2] [30].

Extraction for GC-MS Analysis

In contrast, the utility of GC-MS is inherently limited to metabolites that are volatile and thermally stable. Since many biologically relevant metabolites do not possess these properties, the extraction for GC-MS is often just the first step in a more involved process. The initial LLE may be designed to enrich for classes of metabolites known to be amenable to GC-MS, such as organic acids, sugars, or fatty acids. However, the extracted metabolites frequently require a subsequent derivatization step to become volatile enough for GC separation [1] [18]. For instance, in the same lupus nephritis study that used LC-MS, the serum samples for GC-MS analysis underwent a multi-step derivatization process after extraction, involving methoximation and silylation before injection into the instrument [14]. This highlights how the extraction for GC-MS is intrinsically linked to the goal of producing volatile analyte derivatives.

Table 1: Common Extraction Solvents and Their Applications in Metabolomics

| Solvent System | Characteristics | Target Metabolites | Compatible Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol/Chloroform/Water | Biphasic system; classical method | Polar metabolites (aqueous phase); Lipids (organic phase) | Primarily LC-MS |

| 100% Methanol | Monophasic; efficient protein precipitation | Highly polar metabolites | Primarily LC-MS |

| Methanol/Acetonitrile | Monophasic; effective for serum/plasma | Broad range of polar metabolites | LC-MS (and GC-MS post-derivatization) |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Non-polar; forms biphasic system with MeOH/H₂O | Lipids (organic phase) | LC-MS (Lipidomics) |

The Role of Derivatization in GC-MS Analysis

Derivatization is a chemical modification process that is often mandatory for GC-MS analysis but is rarely used in LC-MS. This step is a critical differentiator that adds complexity, time, and potential for error to the GC-MS workflow.

Purpose and Protocols

The primary goals of derivatization are to: (1) increase the volatility of non-volatile metabolites, (2) improve thermal stability to prevent decomposition in the hot GC inlet, and (3) enhance the chromatographic behavior and detectability of analytes [18] [14]. A standard derivatization protocol, as used in clinical studies, typically involves a two-step process [14]:

- Methoximation: The sample is treated with methoxyamine hydrochloride to protect carbonyl groups (e.g., in sugars and keto acids) by forming methoximes, which prevents ring formation and improves peak shape.

- Silylation: The sample is then derivatized with a silylating agent like N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA), which replaces active hydrogens in groups (-OH, -COOH, -NH) with trimethylsilyl groups. This step drastically increases the volatility and thermal stability of the metabolites.

This process can extend sample preparation time by several hours and requires careful control of reaction conditions to ensure completeness and reproducibility.

Impact on Data and Analysis

Derivatization enables GC-MS to analyze a wide range of otherwise inaccessible metabolites. A key strength of this approach is the "hard" Electron Impact (EI) ionization used in GC-MS, which produces highly reproducible and compound-specific fragmentation patterns [1] [18]. These fragmentation patterns are searchable against extensive, standardized spectral libraries (e.g., NIST, Wiley), allowing for confident metabolite identification across different laboratories and over decades [18]. However, the derivatization process itself can introduce artifacts, and incomplete reactions can lead to multiple derivatives for a single metabolite, complicating data analysis. Furthermore, the additional sample manipulation increases the risk of introducing contaminants and can negatively impact the reproducibility of the analysis if not meticulously controlled [31].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Data from Practical Applications

Direct comparisons of LC-MS and GC-MS in real-world studies highlight the practical implications of their differing sample preparation requirements and analytical capabilities.

Sensitivity and Metabolite Coverage

Quantitative data demonstrates that LC-MS generally offers higher sensitivity, with detection limits as low as 10⁻¹⁵ mol for some compounds, compared to 10⁻¹² mol for GC-MS [1]. This superior sensitivity, combined with its ability to analyze compounds without derivatization, allows LC-MS to cover a wider range of substance types, including large, thermolabile, and polar molecules like peptides, phospholipids, and glycosylated compounds [1] [18]. GC-MS, while more limited in scope, provides exceptional chromatographic resolution, particularly for volatile and semi-volatile compounds, and is often more effective at separating structural isomers [18].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of LC-MS and GC-MS in Metabolite Analysis

| Performance Metric | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | 10⁻¹⁵ mol [1] | 10⁻¹² mol [1] |

| Ionization Method | Electrospray (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [1] [32] | Electron Impact (EI) [1] [18] |

| Ionization Character | Soft (produces molecular ions) [32] | Hard (produces fragment ions) [1] |

| Key Identification Data | Accurate mass, MS/MS fragmentation, Retention time [32] | Reproducible EI spectrum, Retention time, Library matching [18] |

| Required Sample Prep | Minimal to moderate (e.g., protein precipitation) [18] [14] | Often complex, frequently requires derivatization [18] [14] |

A Case Study in Clinical Research

A 2024 study on lupus nephritis (LN) patients provides a clear example of the complementary nature of these platforms. Researchers used both untargeted GC/MS and LC/MS to analyze serum from 50 LN patients and 50 healthy controls [14]. The LC-MS sample preparation involved a straightforward "dilute and shoot" protocol after protein precipitation. In contrast, the GC-MS protocol required a multi-step derivatization process following extraction [14]. This combined approach proved powerful, leading to the identification of 41 potential metabolic biomarkers associated with LN. The study concluded that using both techniques enhanced the understanding of metabolic spectrum changes, a feat that would have been difficult to achieve with either platform alone [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful metabolomics relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and materials. The following table details key items critical for sample preparation in both LC-MS and GC-MS workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (HPLC/MS Grade) | Protein precipitation; extraction of polar metabolites [2]. | High purity is critical to minimize background noise in MS. |

| Chloroform | Extraction of non-polar lipids in biphasic systems [2]. | Used in classical Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods. |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization for extraction efficiency and matrix effects; accurate quantification [2] [30]. | Added at the very beginning of sample processing. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., BSTFA) | Increases volatility and thermal stability of metabolites for GC-MS [14]. | Requires careful handling and controlled reaction conditions. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Clean-up and enrichment of specific metabolite classes; removal of interfering salts [29]. | Various sorbents (C18, ion-exchange) are used selectively. |

Workflow Visualization and Decision Guide

The following diagram summarizes the distinct sample preparation pathways for LC-MS and GC-MS, highlighting the critical decision points that determine the analytical outcome.

Sample Preparation Workflow for LC-MS and GC-MS

The choice between LC-MS and GC-MS for metabolomics research is fundamentally guided by the sample preparation strategy, particularly the use of extraction solvents and derivatization. LC-MS offers a broader, more flexible platform with simpler sample preparation, making it ideal for polar, ionic, and thermally labile metabolites, and enabling high-sensitivity targeted and untargeted discovery. GC-MS, while requiring more complex and time-consuming derivatization, provides superior chromatographic resolution and robust, library-searchable data for volatile and semi-volatile compounds. Rather than seeking a single "best" platform, researchers should view LC-MS and GC-MS as complementary. The most comprehensive metabolomic insights are often achieved by leveraging the distinct strengths of both techniques, either in parallel or in an integrated manner, to illuminate a wider spectrum of biochemical reality.}

Strategic Applications: Choosing the Right Tool for Your Analysis

In mass spectrometry-based metabolomics, the fundamental physical and chemical properties of target analytes directly determine the appropriate analytical instrumentation. The choice between Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) hinges primarily on a compound's volatility, thermal stability, and polarity [12] [18]. GC-MS excels for volatile and thermally stable molecules, while LC-MS provides a superior platform for non-volatile, polar, or thermally labile compounds that would decompose under GC conditions [12] [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal method for their metabolite analysis.

Technical Comparison: LC-MS vs. GC-MS

The core differences between these platforms stem from their separation mechanisms and the interfaces required to couple them with mass spectrometry.

Fundamental Operational Differences

The following diagram illustrates the key differences in the workflows and critical decision points for LC-MS and GC-MS analysis.

Key Technical Parameters and Performance

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of LC-MS and GC-MS

| Parameter | GC-MS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Mechanism | Gas-phase separation using inert carrier gas and high-temperature capillary column [18] [3] | Liquid-phase separation using pressurized liquid mobile phase and packed column [18] [1] |

| Ionization Source | Electron Impact (EI) [18] [1] | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [5] [18] |

| Ionization Character | "Hard" ionization, generates reproducible fragment ions [18] [1] | "Soft" ionization, often produces intact molecular ions [18] [1] |

| Optimal Analyte Molecular Weight | Typically ≤ 500 Da [18] | Broad range, from small metabolites to large biomolecules (>10 kDa) [18] |

| Typical Analysis Time | Faster process [3] | Variable, but can be very fast with UHPLC (2-5 minutes) [5] |

| Spectral Libraries | Extensive, reproducible EI libraries (e.g., NIST, Wiley) [18] | Less comprehensive; relies more on MS/MS and authentic standards [18] |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Experimental comparisons consistently demonstrate technique-dependent performance. A study analyzing pharmaceuticals and personal care products in water found that HPLC-TOF-MS yielded lower detection limits than GC-MS for the same set of compounds [33]. Furthermore, the inherent sensitivity of the techniques varies, with LC-MS typically achieving detection down to 10-15 mol, compared to 10-12 mol for GC-MS [1].

Analysis of Benzodiazepines in Urine

A direct methodological comparison for analyzing benzodiazepines in urine highlights practical trade-offs [20]. Both techniques produced results with comparable accuracy (99.7-107.3%) and precision (%CV <9%). However, the sample preparation and analysis workflows differed significantly.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol Comparison for Benzodiazepine Analysis

| Protocol Step | GC-MS Method [20] | LC-MS/MS Method [20] |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Enzymatic hydrolysis, solid-phase extraction, and derivatization with MTBSTFA | Simplified sample clean-up; often just dilution or minimal extraction |

| Derivatization | Required (adds 60-80 minutes to protocol) | Not required |

| Extraction Time | Longer, multi-step process | Quicker and less extensive |

| Chromatographic Run Time | Longer run times | Shorter run times |

| Matrix Effects | Less impacted | Observed; controlled using deuterated internal standards |

This study concluded that the ease and speed of sample extraction, broader compound range, and shorter run time make LC-MS/MS a suitable and expedient alternative to GC-MS for this application [20].

Complementary Analysis in Clinical Metabolomics

A serum metabolomics study on Lupus Nephritis (LN) patients effectively utilized both platforms to maximize metabolite coverage [14]. Researchers used GC/MS for volatile organic compounds, lipids, and derivatizable molecules, leveraging its high repeatability. They simultaneously employed LC/MS for nonvolatile compounds and large or thermally unstable molecules, taking advantage of its comprehensive profiling capability. This combined approach identified 41 potential LN biomarkers, demonstrating how the techniques are complementary in practice [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols for both techniques rely on specific reagents for sample preparation, separation, and detection.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Metabolomics Analysis

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol/Chloroform Mixtures | Biphasic liquid-liquid extraction; polar metabolites (methanol phase) and non-polar lipids (chloroform phase) [2] | Sample Prep (Both) |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MTBSTFA, BSTFA) | Increase volatility and thermal stability of non-volatile compounds for GC-MS analysis [20] [14] | Sample Prep (GC-MS) |

| Internal Standards (e.g., deuterated analogs, L-2-chlorophenylalanine) | Correct for variability during sample preparation and analysis; enable accurate quantification [2] [14] | Sample Prep (Both) |

| Formic Acid in Mobile Phase | Modifies pH to improve protonation and separation of analytes in LC-MS [33] | LC-MS |

| β-Glucuronidase Enzyme | Hydrolyzes conjugated metabolites (e.g., glucuronides) in urine to free the parent compound for analysis [20] | Sample Prep (Both) |

| C18 SPE Disks/Columns | Solid-phase extraction for pre-concentrating analytes and removing matrix interferences from liquid samples [33] | Sample Prep (Both) |

The choice between LC-MS and GC-MS is not a matter of one technique being superior to the other, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific analytical challenge [18]. GC-MS is the preferred method for volatile and thermally stable compounds, offering robust separation, reproducible fragmentation, and powerful library matching. In contrast, LC-MS is indispensable for non-volatile, polar, ionic, or thermally labile compounds, including large biomolecules, providing high sensitivity with minimal sample preparation. For the most comprehensive metabolomic coverage, employing both techniques in a complementary manner provides the deepest insights into the metabolic state of a biological system [18] [14].