Linearity and Range Validation in Analytical Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Method Development

This article provides a complete guide to linearity and range validation, essential parameters in analytical method validation for pharmaceuticals and bioanalysis.

Linearity and Range Validation in Analytical Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Method Development

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to linearity and range validation, essential parameters in analytical method validation for pharmaceuticals and bioanalysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from ICH Q2(R1/R2) guidelines, step-by-step methodologies for assays and impurities, advanced troubleshooting for non-linearity and matrix effects, and protocols for cross-validation and transfer. By integrating traditional practices with emerging approaches like double-logarithm function linear fitting, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop reliable, accurate, and regulatory-compliant analytical procedures.

Understanding Linearity and Range: Core Principles and Regulatory Definitions

In pharmaceutical analysis, demonstrating that an analytical method performs reliably across a concentration spectrum is a cornerstone of data integrity. The concepts of linearity and range are pivotal to this demonstration, ensuring that a method can produce results directly proportional to the analyte concentration and is suitable for its intended use. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines for the validation of analytical procedures provide the globally harmonized framework for this critical activity. For nearly two decades, ICH Q2(R1) served as the primary guideline, establishing the foundational definitions and requirements. However, with the finalization of ICH Q2(R2) in 2023, alongside the complementary ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development, a significant evolution has occurred [1] [2]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the terminology and requirements for linearity and range between ICH Q2(R1) and the updated Q2(R2), contextualized within the modern paradigm of analytical procedure lifecycle management.

Core Definitions: A Comparative Analysis

While the fundamental purpose of establishing linearity and range remains unchanged, the revised guideline provides enhanced clarity and aligns with a more holistic, science-based approach.

Tabular Comparison of Terminology

The following table summarizes the key definitions and nuances across the two guideline versions.

| Feature | ICH Q2(R1) | ICH Q2(R2) | Key Implications of the Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity Definition | The ability (within a given range) to obtain test results directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte [1]. | The ability of the procedure to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample [1]. | The definition is refined for grammatical precision. The core concept remains intact, ensuring continuity and harmonization. |

| Range Definition | The interval between the upper and lower concentration (amounts) of analyte in the sample (including these concentrations) for which it has been demonstrated that the analytical procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [1]. | The interval between the upper and lower concentration (amounts) of analyte in the sample for which the analytical procedure has suitable performance for its intended use, demonstrated by acceptable precision, accuracy, and linearity [1]. | The updated definition more strongly emphasizes "fitness for purpose," explicitly linking the range to the method's intended use. |

| Conceptual Emphasis | A core validation parameter to be checked. Part of a more discrete, static validation event [1]. | Integrated into the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle. Linearity and range are understood in the context of the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) from ICH Q14 [3] [2]. | Shifts the focus from a one-time demonstration to an integral part of a continuous, knowledge-driven lifecycle. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

The practical determination of linearity and range involves a structured experimental workflow, from planning to data analysis.

Experimental Workflow for Determining Linearity and Range

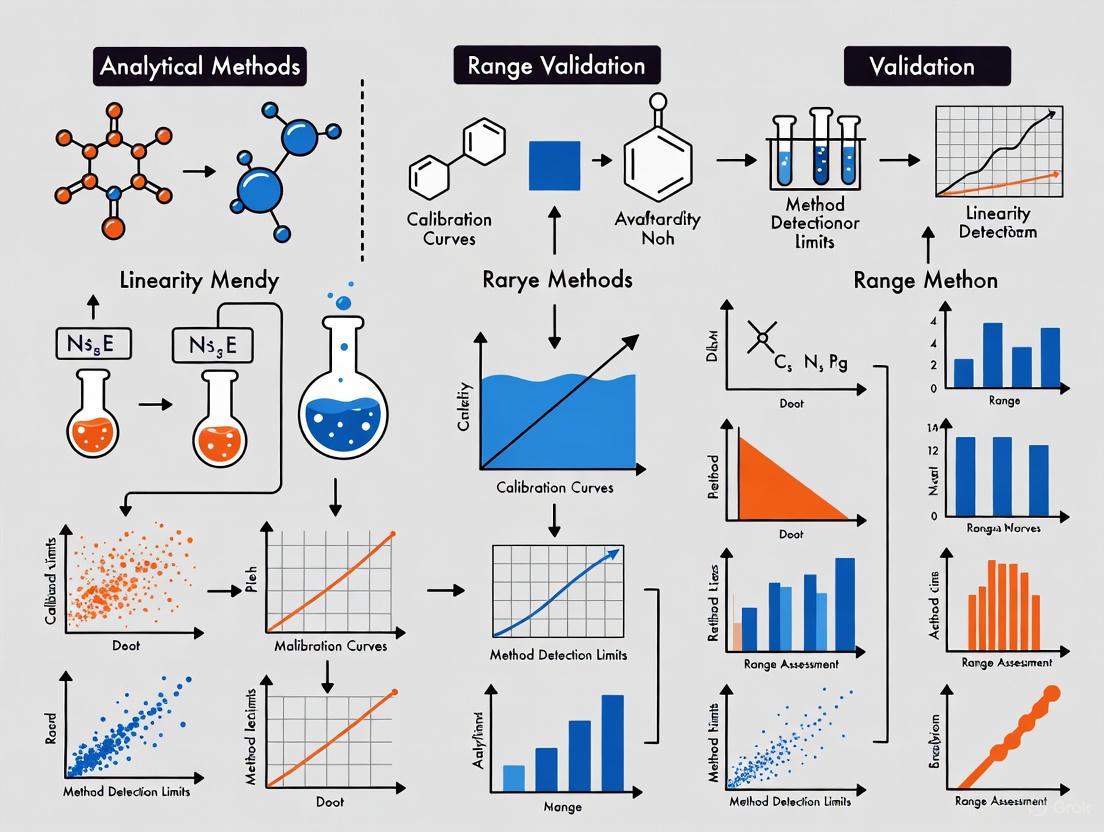

The following diagram visualizes the key stages in establishing linearity and range, applicable to both Q2(R1) and Q2(R2), though the interpretation is now deepened under Q2(R2)'s lifecycle approach.

Detailed Methodology

The general workflow can be broken down into the following detailed steps, which are consistent with regulatory expectations [4]:

- Define the Experimental Plan: Based on the method's intended purpose (e.g., assay, impurity testing), define the theoretical concentration range to be studied. For an assay, a typical range is 80-120% of the target test concentration, while for impurities, it should cover from the quantitation limit (QL) to at least 120% of the specification limit [4].

- Prepare Solutions:

- Prepare a stock solution of the analyte with high purity and known concentration.

- Using the stock solution, prepare a series of at least five to eight solutions spanning the defined range (e.g., 50%, 80%, 100%, 120%, 150% for an assay). ICH Q2(R2) encourages consideration of using independent stock solutions for different concentration levels to improve the robustness of the linearity model [5].

- Analyze Solutions: Inject each concentration level in a randomized sequence to avoid time-dependent bias. The replication strategy should reflect how the method will be used routinely to generate the "reportable result" – a concept emphasized in the revised USP 〈1225〉 which aligns with ICH Q2(R2) [3] [6].

- Record and Plot Data: Record the analytical response (e.g., peak area in chromatography) for each injection. Plot the average response (Y-axis) against the corresponding concentration (X-axis).

- Perform Regression Analysis: Calculate a linear regression line using the least-squares method. The output provides the correlation coefficient (r), coefficient of determination (r²), slope, and y-intercept.

- Evaluate Acceptance Criteria:

- Linearity: The correlation coefficient (r) should typically be ≥ 0.997 (r² ≥ 0.994) [4]. Visually inspect the plot for random residual distribution. Under Q2(R2), more rigorous statistical evaluation of residuals is encouraged [5].

- Range: The range is established as the interval between the lowest and highest concentration levels for which the method demonstrates acceptable linearity, accuracy, and precision.

Case Study: Impurity Method Linearity

The following table presents data from a typical linearity study for an impurity method, demonstrating how the range is derived [4].

| Level | Impurity Value (%) | Concentration (mcg/mL) | Area Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| QL | 0.05% | 0.5 | 15,457 |

| 50% | 0.10% | 1.0 | 31,904 |

| 70% | 0.14% | 1.4 | 43,400 |

| 100% | 0.20% | 2.0 | 61,830 |

| 130% | 0.26% | 2.6 | 80,380 |

| 150% | 0.30% | 3.0 | 92,750 |

| Calculated Parameters | Slope: 30,746 | R²: 0.9993 |

Interpretation: The data shows excellent linearity with an R² of 0.9993, meeting the acceptance criterion (≥ 0.997). The range for this impurity method can therefore be reported as 0.05% (the QL) to 0.30% (150% of the specification limit) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully conducting linearity and range studies requires high-quality materials to ensure data integrity.

| Item | Function | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard | The highly purified analyte used to prepare known concentrations. | Must be of certified purity and quality (e.g., USP, Ph. Eur.). It is the foundation for accuracy. |

| Independent Stock Solutions | Separate weighings and dissolutions used to create different concentration levels for linearity. | Helps identify errors in preparation and provides a more robust assessment of true linearity [5]. |

| HPLC/Grade Solvents | Used for preparing mobile phases, diluents, and sample solutions. | Purity and consistency are critical to avoid baseline noise, ghost peaks, or variable retention times. |

| Volumetric Glassware | For accurate preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions. | Must be Class A to ensure precise volume measurements, directly impacting concentration accuracy. |

| Chromatography System | The instrument (e.g., HPLC, UPLC) used to generate the analytical response. | Must be qualified and well-maintained. System suitability tests are a prerequisite to validation. |

The Paradigm Shift: From Q2(R1) to Q2(R2) and the Lifecycle

The transition from ICH Q2(R1) to Q2(R2) represents more than a textual update; it signifies a fundamental shift in the philosophy of analytical validation, deeply impacting how linearity and range are perceived.

The Lifecycle Context and Relationship to ICH Q14

ICH Q2(R2) is designed to be applied in conjunction with ICH Q14 (Analytical Procedure Development) and is integrated into the broader concept of the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle (APLC) as described in USP 〈1220〉 [3] [1] [2]. This relationship is crucial for understanding the modern interpretation of linearity and range.

Under this model:

- Development (ICH Q14): The required performance for linearity and range is prospectively defined in the Analytical Target Profile (ATP). The ATP states the necessary range and the required linearity (e.g., expected R²) [2].

- Validation (ICH Q2(R2)): The linearity and range study is no longer a standalone "check-box" activity. It is a confirmation that the procedure, as developed, meets the pre-defined ATP criteria [3] [2].

- Ongoing Performance Verification: The verified linearity and range are monitored throughout the method's lifetime. If routine system suitability tests or quality control sample data indicate a drift, it may trigger a re-investigation of the method's linearity within its range [3].

Key Changes in Regulatory Scrutiny

While the core experimental approach may look similar, the regulatory expectations for the data's depth and context have evolved.

| Aspect | ICH Q2(R1) Approach | ICH Q2(R2) Enhanced Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Evaluation | Primarily relied on correlation coefficient (r or r²) and visual inspection of the plot [1]. | Encourages more rigorous statistical analysis, such as evaluation of residuals to detect non-random patterns and better statistical justification for the chosen model [5] [1]. |

| Documentation & Justification | Focused on reporting the regression data and confirming acceptance criteria were met. | Requires a more comprehensive scientific justification for the chosen range and linearity model, linked directly to the ATP and the method's intended use [1]. |

| Link to Control Strategy | Linearity and range were seen as fixed characteristics established during validation. | The established range is a key element of the analytical procedure control strategy, which includes system suitability tests to ensure the calibration curve's performance remains consistent over time [1] [2]. |

The definitions of linearity and range have remained consistent from ICH Q2(R1) to Q2(R2), preserving a harmonized global language for analytical validation. However, the context in which these parameters are established, evaluated, and managed has transformed profoundly. The move from a discrete, static validation event under Q2(R1) to an integrated, knowledge-driven lifecycle approach under Q2(R2) and Q14 demands a deeper scientific understanding. For today's drug development professional, successfully defining linearity and range means not only executing a well-designed experiment with clear acceptance criteria but also being able to articulate how these parameters ensure the method is and remains "fit for purpose" throughout the entire product lifecycle. This enhanced, holistic understanding is key to building robust, reliable, and regulatory-compliant analytical procedures.

In the world of analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the ability to trust your data is paramount. At the heart of this trust lies linearity, a fundamental parameter in analytical method validation that confirms an instrument's response is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte being measured [7] [8]. Establishing a linear relationship is not merely a regulatory checkbox; it is the foundational principle that enables researchers to accurately translate a raw instrument signal—a peak area, a voltage, an optical density—into a reliable quantitative result [9]. Without demonstrated linearity across a defined range, the accuracy of every subsequent measurement remains in question, potentially compromising drug potency, patient safety, and scientific conclusions.

Understanding Linearity and Its Validation

Linearity, together with its partner range, forms the bedrock of a reliable quantitative analytical procedure [7].

- Linearity refers to the ability of an analytical method to produce results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a sample within a given range [7] [10]. It is evaluated by preparing and analyzing a series of standards across the intended concentration span and statistically assessing the relationship between concentration and response.

- Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels of the analyte for which the method has been demonstrated to have suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [7]. The range defines the boundaries within which the method is proven to perform reliably.

The process for validating linearity typically involves preparing at least five concentration levels across the intended range, often from 50% to 150% of the target or specification limit [7] [9]. Each level is analyzed, and the results are used to plot a calibration curve. The statistical evaluation, however, must extend beyond a high correlation coefficient (R²) to ensure true proportionality [11].

Diagram 1: Workflow for validating linearity in an analytical method.

Beyond R²: A Deeper Look at Linearity Assessment

A common pitfall in linearity assessment is over-reliance on the correlation coefficient (R²). A high R² value (often >0.995 or >0.997) is typically required [7] [9], but this alone is an insufficient indicator of a proportional relationship [10] [11]. R² merely describes the goodness-of-fit and can mask systematic biases, such as a significant non-zero intercept or patterns of non-linearity [10].

A more robust evaluation involves:

- Visual inspection of the calibration curve and, more importantly, the residual plot [9] [11]. A plot of the residuals (the difference between the measured and fitted values) should show random scatter around zero. Any distinct pattern (e.g., a U-shape or funnel-shape) indicates a non-linear response or heteroscedasticity, even with a high R² [11].

- Analysis of the y-intercept and slope. The absolute value of the y-intercept should be small, and ideally, the regression line should pass through the origin for a perfectly proportional relationship [10].

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters for Linearity Assessment

| Parameter | Description | Common Acceptance Criteria | Pitfalls of Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient (R²) | Measures the strength of the relationship between concentration and response. | Typically ≥ 0.995 or 0.997 [7] [9]. | A high R² does not prove proportionality and can hide a poor fit [10] [11]. |

| Y-Intercept | The value of the response when concentration is zero. | Should be small relative to the response at the target level; often statistically indistinguishable from zero [10]. | A large intercept indicates constant systematic error, affecting accuracy at low concentrations. |

| Residual Plot | A graph of the difference between measured and predicted values. | Residuals should be randomly scattered around zero with no discernible patterns [9] [11]. | Patterns (U-shape, funnel-shape) reveal non-linearity or changing variance not captured by R² [11]. |

| Slope | The change in response per unit change in concentration. | Should be consistent and significant, indicating sufficient method sensitivity. | A low slope may indicate poor sensitivity, making the method susceptible to noise at low concentrations. |

Advanced approaches, such as the double logarithm function linear fitting method, have been proposed to more rigorously demonstrate the degree of data proportionality as defined in ICH guidelines [10].

Comparative Experimental Data: Linearity in Action

The critical nature of linearity becomes evident when examining experimental data from different analytical fields. The following table summarizes findings from two studies, highlighting how linearity is assessed and the consequences of non-linearity.

Table 2: Experimental Case Studies on Linearity Performance

| Study Focus | Methodology & Protocol | Key Findings on Linearity | Impact on Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Metabolomics (Orbitrap MS) [12] | Protocol: A stable isotope-assisted dilution series of wheat ear extracts was analyzed via RP-LC-HRMS (Q Exactive HF Orbitrap). A wide range of dilution levels was used to assess the relationship between concentration and signal intensity for 1327 metabolites. | 70% of detected metabolites showed non-linear effects across the full dilution series. When a smaller range (4 levels, 8-fold difference) was considered, 47% of metabolites demonstrated linear behavior [12]. | Non-linearity led to an overestimation of abundances in less concentrated samples, increasing the risk of false-negative findings in statistical analyses of biological data [12]. |

| Targeted Oxylipin Profiling (LC-MS/MS) [13] | Protocol: An online solid-phase extraction-LC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for 49 oxylipins in human serum. Linearity was assessed by analyzing standard solutions across a defined concentration range, with recovery and precision evaluated at multiple levels. | The method demonstrated a wide linear range with limits of quantification from 0.18 to 9 pg. It enabled accurate (80–120% recovery) and precise (RSD < 15%) quantification for 32 analytes [13]. | The confirmed linearity and sensitivity allowed for high-throughput, reliable quantification of trace-level inflammatory biomarkers in a large epidemiological study (565 samples), linking specific oxylipins to glucose tolerance [13]. |

These case studies underscore that linearity is not an absolute property but is dependent on the analyte, matrix, and instrumentation. A method perfectly linear for one analyte may be non-linear for another, even on the same platform [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Linearity Assessment

Conducting a rigorous linearity study requires high-quality materials and reagents to ensure the integrity of the results. The following table details key items essential for these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Linearity Validation

| Item | Function in Linearity Assessment |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | High-purity analytes of known concentration and identity used to prepare calibration standards. They are the foundation for establishing the true concentration-response relationship [9]. |

| Blank Matrix | The sample material without the analyte of interest (e.g., drug-free serum, placebo formulation). Used to prepare calibration standards to mimic the sample matrix and account for matrix effects that can distort linearity [9]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Chemically identical analogs of the analyte labeled with heavy isotopes (e.g., ¹³C, ²H). They are added to all samples to correct for variability in sample preparation, injection, and ion suppression/enhancement in MS, improving accuracy and precision [12]. |

| Volumetric Glassware & Calibrated Pipettes | Precision tools required for accurate and precise serial dilutions to create the standard concentration levels for the calibration curve. Inaccurate dilution is a major source of error in linearity assessment [9]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known concentrations of the analyte prepared independently from the calibration standards. They are analyzed alongside the calibration curve to verify the accuracy and precision of the method across the validated range. |

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting common causes of non-linearity and their solutions.

Linearity is far more than a technical requirement in a validation protocol. It is a critical indicator of an analytical method's fundamental reliability for accurate quantification. As demonstrated, a thorough assessment must extend beyond a single metric like R² to include residual analysis and evaluation of the intercept [10] [11]. The consequences of undetected non-linearity are significant, leading to systematic errors, inaccurate potency assessments, and flawed scientific conclusions. For researchers and drug development professionals, a rigorous, evidence-based demonstration of linearity across the intended range is non-negotiable. It provides the confidence that the data generated truly reflects the composition of the sample, thereby ensuring product quality, patient safety, and the integrity of scientific research.

In the realm of analytical method validation, few topics generate as much confusion as the distinction between linearity of results and response function. This guide cuts through the complexity, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear, objective comparison based on current regulatory science and experimental data.

Defining the Core Concepts: A Head-to-Head Comparison

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guideline provides a definition for linearity, yet its practical application often leads to the conflation of two distinct ideas [10]. The table below delineates these concepts.

| Feature | Linearity of Results | Response Function |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | The relationship between the theoretical concentration of the analyte in the sample and the final test result back-calculated from the calibration model [10]. | The relationship between the instrumental response and the concentration of the analyte [10]. |

| Primary Focus | Validates the overall analytical procedure's ability to produce proportional results across the range. It assesses the entire process from sample preparation to final calculated value [10]. | Describes the performance of the instrumental system and the mathematical model (e.g., linear, quadratic) used for the calibration curve [10]. |

| What is Evaluated | Sample dilution linearity; the proportionality between known sample concentrations and their back-calculated values [10]. | The fit of the calibration curve; often assessed using the coefficient of determination (R²), which measures correlation, not necessarily proportionality [10]. |

| Common Point of Confusion | Often mistakenly evaluated by the R² of the calibration curve, which verifies the response function, not the linearity of results from the sample [10]. | Frequently conflated with the linearity of the entire analytical procedure, leading to potential inaccuracies in method validation [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Distinction

To objectively compare the performance of evaluating "linearity of results" versus relying solely on "response function," specific experimental protocols are required. The following methodologies are cited from current research.

Protocol for Linearity of Results (Sample Dilution Linearity)

This protocol is designed to directly validate the proportionality required by the ICH definition.

- Methodology: A dilution series of the sample matrix (e.g., drug product) is prepared across the specified range (e.g., 50% to 150% of the test concentration) [7] [14]. Each dilution is analyzed, and the test result for the analyte is calculated using the established calibration curve. The known theoretical concentrations are then plotted against the back-calculated results [10].

- Data Analysis: The relationship is evaluated using the double logarithm function linear fitting method. The logarithms of the theoretical values and the back-calculated results are taken, and a linear regression is performed using the least-squares method. The slope of this log-log plot directly indicates the degree of proportionality [10]:

- A slope of 1.00 indicates a perfect directly proportional relationship.

- The acceptance criterion is derived from the confidence interval of the slope; for instance, a slope of 1.00 ± 0.03 may be acceptable [10].

- Supporting Data: A study applying this method demonstrated that while a traditional R² value was 0.9990 for a calibration curve, the double logarithm method revealed a slope of 0.941 for sample results, indicating a non-linear relationship and failing the linearity of results criterion [10].

Protocol for Response Function (Calibration Curve Linearity)

This protocol evaluates the instrumental calibration, which is the current common practice.

- Methodology: A series of standard solutions in a simple solvent are prepared across a defined range. These are injected, and the instrumental responses (e.g., peak area in HPLC) are recorded [7].

- Data Analysis: A calibration curve is constructed by plotting the response against the theoretical concentration of the standards. The data is fitted using a model (e.g., unweighted least-squares linear regression), and the coefficient of determination (R²) is calculated [7] [15].

- Supporting Data & Limitations: A typical acceptance criterion is R² ≥ 0.997 for impurity methods [7] or 0.999 for assay methods [14]. However, a high R² merely indicates a strong correlation and a good fit of the chosen model; it does not confirm that the relationship is directly proportional or that the method will yield accurate results for a sample [10]. Furthermore, R² is sensitive to heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance across the range) [10].

Comparison of Experimental Pathways for Response Function and Linearity of Results

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials required for the experiments cited in this guide.

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Stock Solutions A & B [7] | Used as primary sources to prepare linearity solutions across a concentration range (e.g., 50% to 150%), ensuring traceability and consistency. |

| Linearity Solutions (Minimum 5 levels) [7] [14] | A series of solutions at defined concentrations (e.g., LOQ, 50%, 100%, 120%, 150%) used to experimentally demonstrate the method's performance across its range. |

| Stable Isotope-Labelled Internal Standard [12] | Used in complex matrices (e.g., plant metabolomics) to identify true metabolites and correct for matrix effects, thereby improving the accuracy of assessing linearity. |

| Sample Matrix (e.g., Drug Product) [10] | The actual sample containing the analyte, used in dilution linearity studies to validate the entire analytical procedure under realistic conditions, not just the standard-in-solvent response. |

| Reference Standards (Impurities/API) [7] [12] | Well-characterized materials of known purity and identity used to prepare calibration standards and spike samples, crucial for establishing accuracy and the response function. |

The distinction between linearity of results and response function is not merely semantic. Relying solely on the R² of a calibration curve (response function) to prove method linearity is a fundamental oversight that can compromise the validity of an analytical procedure [10]. The emerging best practice, supported by the ICH Q2(R2) guideline's focus on results proportional to true sample values, is to implement sample dilution linearity tests analyzed with robust statistical tools like the double logarithm method [10]. For fields like untargeted metabolomics, where non-linear behavior is prevalent [12], or for complex biological assays, this distinction becomes critical for generating reliable, high-quality data that accurately reflects sample composition.

In analytical chemistry, the validation of a method is paramount to ensuring the reliability and accuracy of data. Among the various performance characteristics, linearity and range are foundational, confirming that a method provides results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a specified interval. However, the definition of this range is not arbitrary; it is intrinsically tied to the method's intended application. This guide explores how the determination of an analytical method's range is a critical, application-dependent process, comparing established protocols across different analytical uses in pharmaceutical development.

Defining Linearity and Range in Analytical Methods

The linearity of an analytical procedure is its ability (within a given range) to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample [14]. It verifies that the instrument's response increases linearly with the analyte concentration, a principle grounded in laws like Lambert-Beer's Law for HPLC-UV methods [10].

The range, an extension of linearity, is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of an analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity using the method as written [15]. It is not merely the span over which a response is linear but is explicitly defined by the intended use of the method, ensuring the procedure is suitable for its application—from drug assay to impurity quantification.

Core Principles of Range Determination

The process of setting the range is governed by several key principles:

- Direct Proportionality: The fundamental requirement is a direct proportional relationship between concentration and response, which is validated through linear regression statistics [16].

- Fitness-for-Purpose: The range must cover all critical specification limits relevant to the method's application, ensuring reliable quantification at release and stability testing thresholds [14].

- Statistical and Visual Assessment: Linearity is established by plotting concentration against response and evaluating parameters like the coefficient of determination (r²), y-intercept, and residual sum of squares [14] [10].

- Holistic Validation: The demonstrated range must also satisfy acceptance criteria for precision and accuracy at the upper and lower limits [15].

Application-Specific Range Protocols: A Comparative Analysis

The requirements for linearity and range vary significantly depending on the analytical procedure's goal. The following table summarizes the typical ranges mandated by guidelines for different method types in pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Recommended Ranges for Different Analytical Applications

| Method Application | Recommended Range (as % of target concentration) | Key Guidelines Referenced | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Substance Assay | 80% to 120% | ICH Q2(R1) [14] | Covers expected manufacturing variability around the 100% target. |

| Content Uniformity | 70% to 130% | ICH Q2(R1) [14] | Ensures accurate measurement across a wider range to confirm dosage unit homogeneity. |

| Dissolution Testing (Immediate-Release) | -20% to +20% over the specification (e.g., 60% to 100%) | ICH Q2(R1) [14] | Validates performance from the quantification limit to the specified dissolution limit. |

| Related Substances/Impurities | Reporting Level to 120% of the specification | ICH Q2(R1) [14] | Ensures accurate quantification from the lowest reportable level up to levels exceeding the specification. |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Range

The process for establishing linearity and range follows a detailed experimental protocol.

Table 2: Standard Experimental Protocol for Linearity and Range Determination

| Protocol Step | Detailed Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Solution Preparation | A minimum of 5 concentrations are prepared within the anticipated range [14]. For an assay, this typically means 80%, 90%, 100%, 110%, and 120% of the target concentration. | Solutions should be prepared from independent weighings/dilutions to incorporate preparation variability. |

| 2. Instrumental Analysis | Each linearity level is analyzed, typically in triplicate, to assess precision [15]. The sequence should be randomized to avoid systematic drift. | The method conditions should be identical to those intended for routine use. |

| 3. Data Plotting and Analysis | The mean response (e.g., peak area) is plotted against the theoretical concentration. A regression line is calculated using the least-squares method [16] [10]. | Visual inspection of the plot is crucial to detect deviations from linearity or outliers. |

| 4. Statistical Evaluation | Key parameters are calculated:- Correlation Coefficient (r): Should be ≥ 0.999 for assay, ≥ 0.997 for impurities [14].- Y-Intercept and %Y-Intercept: Assesses constant bias; should be ≤ 2.0% for assay [14].- Residual Sum of Squares: Evaluates the goodness-of-fit. | A high r-value alone does not prove proportionality; the y-intercept must also be evaluated [10]. |

| 5. Range Verification | The upper and lower limits of the proposed range are verified to meet acceptance criteria for accuracy (e.g., 98-102% recovery) and precision (%RSD < 2.0%) [15]. | This confirms the method is valid at the range boundaries. |

Advanced Statistical Approaches

While linear regression is standard, advanced techniques are sometimes necessary. The double logarithm function linear fitting is a novel method that transforms data by taking the logarithm of both theoretical concentrations and measured results before linear fitting. The slope of this log-log plot directly indicates the degree of proportionality, providing a more rigorous assessment of linearity as defined by ICH [10].

Decision Workflow for Range Determination

The following diagram illustrates the logical process and key decision points for defining the analytical range based on the method's intended application.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for conducting robust linearity and range studies.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Linearity and Range Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Analyte Reference Standard | Serves as the basis for preparing linearity solutions to establish the concentration-response relationship. | Certified purity, stability, and identity; traceable to a primary standard. |

| Appropriate Solvent/Diluent | Used to dissolve and dilute the analyte to the required linearity levels. | Should mimic the final sample solution; must not degrade the analyte or interfere with detection. |

| Blank Matrix | For drug product or bioanalytical methods, a placebo or biological matrix is used to assess specificity and prepare spiked standards. | Must be free of the target analyte and representative of routine samples. |

| Chromatographic Columns & Mobile Phases | For LC methods, these are critical for achieving separation and generating the analytical signal. | Reproducibility between lots, suitability for the analyte, and compliance with the method's specifications. |

| Volumetric Glassware & Pipettes | Essential for accurate and precise preparation of linearity solutions. | Class A tolerance, calibrated, and appropriate for the required volume range. |

Defining the analytical range is a deliberate, application-driven process that is fundamental to method validation. As demonstrated, the acceptable range varies significantly—from 80-120% for a drug assay to the reporting level and beyond for impurities. This variation underscores the principle that an analytical method is not validated in isolation but is qualified for a specific purpose. A rigorous, statistically-supported linearity study, designed with the intended application in mind, sets the correct boundaries for the method. This ensures that throughout its lifecycle, the method will provide reliable data, thereby safeguarding product quality and supporting regulatory compliance.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the reliability of analytical data is the cornerstone of quality control, regulatory submissions, and ultimately, patient safety [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the landscape of regional regulations for method validation can be a significant challenge. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), along with regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), provide harmonized frameworks to ensure that analytical methods are validated to global standards [2]. These guidelines ensure that a method validated in one region is recognized and trusted worldwide, thereby streamlining the path from drug development to market [2]. At the heart of these guidelines are fundamental performance parameters, among which linearity and range are critical for demonstrating that an analytical method can produce results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range [17] [15]. This guide objectively compares the approaches of ICH, FDA, and EMA guidelines, with a focused lens on their expectations for linearity and range validation, providing a structured comparison for scientific application.

Core Principles and the Modern Lifecycle Approach

The validation of analytical procedures is not a one-time event but a continuous process integrated into the method's entire lifecycle [2]. The ICH guidelines, particularly ICH Q2(R2) on the validation of analytical procedures and the complementary ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development, embody this modernized, science- and risk-based approach [2] [18].

ICH Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures: This is the core global reference that defines the validation characteristics required to demonstrate a method is fit-for-purpose [17] [2]. The recent revision modernizes the principles from the previous Q2(R1) by expanding its scope to include modern technologies (e.g., multivariate analytical procedures) and further emphasizing a science- and risk-based approach to validation [2]. It covers procedures for identity, assay, purity, and impurity testing of both chemical and biological/biotechnological drug substances and products [17] [18].

ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development: This guideline introduces a structured framework for developing analytical procedures. It promotes the use of an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)—a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and its required performance characteristics [2] [18]. By defining the ATP at the outset, a laboratory can design a fit-for-purpose method and a validation plan that directly addresses its specific needs, including the target range for linearity and the required accuracy and precision within that range [2].

The FDA and EMA, as key members of the ICH, adopt and implement these harmonized guidelines [2]. For a U.S. submission, complying with ICH Q2(R2) is a direct path to meeting FDA requirements [2]. Similarly, the EMA has adopted the ICH Q2(R2) guideline [18]. This harmonization means that for most new drug submissions, the core principles for validating linearity and range are consistent across these regulatory bodies. The FDA's own guidance expands upon the ICH framework, often providing additional detail and emphasizing lifecycle management and robust documentation [19].

Comparative Analysis of Guidelines and Linearity & Range Requirements

The following table provides a detailed comparison of the three key regulatory guidelines, highlighting their overarching focus and specific requirements for linearity and range.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of ICH, FDA, and EMA Guidelines for Analytical Method Validation

| Feature | ICH Q2(R2) | FDA Guidance | EMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope & Role | Provides the harmonized global foundation for validation parameters and definitions [17] [2]. | Adopts and implements ICH guidelines, providing additional detail and emphasis for the U.S. market, with a focus on lifecycle management [2] [19]. | Adopts and implements ICH guidelines for the European market, ensuring compliance with EU regulatory requirements [18] [20]. |

| Primary Document | ICH Q2(R2) "Validation of Analytical Procedures" [17]. | "Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation for Drugs and Biologics" (aligned with ICH Q2(R2)) [2] [19]. | ICH Q2(R2) scientific guideline [17] [18]. |

| Core Approach | Science- and risk-based; integrated with development via Q14 [2]. | Risk-based, with emphasis on method robustness and thorough documentation [2] [19]. | Science- and risk-based, in line with ICH principles [18]. |

| Linearity Definition | The ability of the method to obtain test results directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample [15]. | Consistent with ICH: the ability of the method to produce results proportional to analyte concentration [2] [9]. | Consistent with ICH definition [18]. |

| Range Definition | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations (including these concentrations) of analyte that has been demonstrated to be determined with a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [15]. | Consistent with ICH: the interval where precision, accuracy, and linearity are acceptable [2]. | Consistent with ICH definition [18]. |

| Minimum Data Points | A minimum of 5 concentration levels [15]. | A minimum of 5 concentration levels [9]. | A minimum of 5 concentration levels (per ICH) [18]. |

| Typical Range (Assay) | 80% - 120% of the test concentration [15]. | 80% - 120% of the test concentration [19]. | 80% - 120% of the test concentration (per ICH) [18]. |

| Typical Range (Impurity Test) | From reporting level to 120% of specification [15]. | From reporting level to 120% of specification [19]. | From reporting level to 120% of specification (per ICH) [18]. |

| Key Acceptance Criteria | Correlation coefficient (R²), y-intercept, visual inspection of the plot, and residual analysis [18] [9]. | Correlation coefficient (R² > 0.995 is common), y-intercept, residual plots, and visual inspection to detect bias [9]. | Correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and residual analysis (per ICH) [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Linearity and Range

Step-by-Step Workflow for Linearity and Range Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing linearity and range, from preparation to final determination.

Detailed Protocol for an HPLC Impurity Assay

The experimental workflow for linearity and range is demonstrated through a typical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method for a related substance (Impurity A) [7].

Objective: To demonstrate the linearity of an HPLC method for Impurity A and establish its valid range [7].

Methodology:

Standard Preparation: Two independent stock solutions are prepared. A series of at least five solutions are then prepared from these stocks, spanning the intended range. For an impurity specified at 0.20%, a range from the Quantitation Limit (QL) to 150% of the specification is appropriate [7] [9]. The solutions are often analyzed in a randomized order to eliminate systematic bias [9]. Table 2: Linearity Solution Preparation for Impurity A

Level Impurity Value Impurity Solution Concentration QL (0.05%) 0.05% 0.5 mcg/mL 50% 0.10% 1.0 mcg/mL 70% 0.14% 1.4 mcg/mL 100% 0.20% 2.0 mcg/mL 130% 0.26% 2.6 mcg/mL 150% 0.30% 3.0 mcg/mL Analysis and Data Collection: Each linearity solution is injected into the HPLC system, and the chromatographic area response for Impurity A is recorded [7].

Data Analysis and Statistical Evaluation: A calibration curve is plotted with the concentration on the X-axis and the corresponding area response on the Y-axis [7]. Using statistical software, the line of best fit is calculated, yielding the regression equation (y = mx + c), its correlation coefficient (R²), and the slope [7] [9].

- Correlation Coefficient (R²): A value of ≥ 0.995 is generally considered acceptable, indicating a strong linear relationship [9]. However, a high R² value alone is not sufficient proof of linearity [9].

- Residual Plot: The differences between the observed data points and the regression line (residuals) should be plotted. A valid linear relationship is indicated by residuals that are randomly scattered above and below zero, with no discernible patterns (e.g., U-shaped or funnel-shaped) [9].

Table 3: Example Linearity Data for Impurity A

Impurity A (mcg/mL) Area Response 0.5 15,457 1.0 31,904 1.4 43,400 2.0 61,830 2.6 80,380 3.0 92,750 Slope 30,746 Correlation Coefficient (R²) 0.9993 Range Determination: The validated range is the interval between the lowest and highest concentration levels for which linearity, accuracy, and precision have been demonstrated [15]. In this case, the range for Impurity A is established as 0.05% to 0.30% (from the QL to 150% of the specification limit) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials required for performing linearity and range experiments, particularly in chromatographic analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Linearity and Range Validation

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | A material of established purity and traceability used to prepare the stock and calibration solutions, ensuring accuracy and reliability of the results [9]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used for preparing mobile phases and sample solutions. High purity is critical to minimize background noise and interference, which can affect the detection limit and linearity at low concentrations [9]. |

| Blank Matrix | The sample material without the analyte of interest. Used to prepare calibration standards to account for matrix effects that can distort the linear response, especially in complex biological samples [9]. |

| System Suitability Standards | Reference solutions used to verify that the chromatographic system is performing adequately before and during the analysis, ensuring that the data collected is valid [18]. |

Visualization of the Linearity Assessment Logic

The decision process for accepting or investigating a linearity study involves both statistical and visual checks, as summarized below.

The ICH, FDA, and EMA guidelines for analytical method validation are highly harmonized, particularly regarding the core parameters of linearity and range. The fundamental principles—requiring a minimum of five concentration levels, demonstrating a direct proportional relationship between response and concentration, and establishing a range where suitable precision and accuracy exist—are consistent across these regulatory bodies [17] [2] [18]. The modern approach, championed by ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, moves beyond a prescriptive checklist to a science- and risk-based lifecycle model [2]. For researchers, this means that a well-executed linearity study, which includes not only a strong correlation coefficient but also a critical evaluation of residual plots, will serve as robust evidence for regulatory compliance across major international markets. By adhering to these detailed protocols and understanding the comparative expectations, scientists can ensure their analytical methods are not only validated but truly robust and fit-for-purpose throughout their entire lifecycle.

Executing Validation: A Step-by-Step Guide for Assays, Impurities, and Dissolution

In analytical method validation, linearity and range are fundamental parameters that establish the reliability and suitability of a procedure for its intended purpose. Linearity is defined as the ability of a method to elicit test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a sample within a given range [2]. The range refers to the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of an analyte for which the method has demonstrated an acceptable level of linearity, accuracy, and precision [15]. For researchers and drug development professionals, proper experimental design for establishing these parameters is critical for regulatory compliance and ensuring data integrity. The design phase requires careful selection of concentration levels and a demonstrated understanding of the method's performance across the entire specified range, forming the foundation for a robust analytical procedure [9].

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

Global regulatory guidelines provide a framework for designing linearity and range experiments. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, particularly ICH Q2(R1) and its updated successor ICH Q2(R2), are the recognized global standards [2]. These guidelines, adopted by regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), emphasize a science- and risk-based approach to method validation [21] [2]. A significant modern evolution is the shift towards analytical lifecycle management, as introduced in ICH Q14, which integrates method development and validation into a continuous process, moving away from a one-time event [2]. This lifecycle approach begins with defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP), a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance criteria, which in turn informs the design of the validation study [2].

Minimum Range Requirements by Test Type

Regulatory guidelines specify minimum range requirements depending on the analytical application. These ranges are designed to ensure the method is suitable for its specific use case, whether for assessing the main component or detecting low-level impurities. The following table summarizes the typical minimum ranges as recommended by ICH guidelines [22] [15]:

| Test Type | Typical Minimum Range | Justification and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Assay | 80% to 120% of the test concentration [22] | Ensures accuracy and linearity around the target (100%) concentration. |

| Impurity Testing | Reporting level to 120% of the specification [22] | Must demonstrate the ability to quantify from the reporting level up to above the specification limit. |

| Combined Assay & Impurity | Reporting level to 120% of the assay specification [22] | The range must cover both the main component and the impurities. |

| Content Uniformity | 70% to 130% of the test concentration [22] | A wider range is required to ensure uniform dosage unit performance. |

Experimental Design for Concentration Levels

The selection of concentration levels is a critical step in demonstrating linearity. A well-designed experiment provides a comprehensive profile of the method's performance across the entire specified range.

Key Design Parameters

Researchers must adhere to several key parameters when designing a linearity study:

- Number of Concentration Levels: A minimum of five distinct concentration levels is required to establish linearity [9] [15].

- Range of Concentrations: The levels should appropriately bracket the target concentration. A common practice is to prepare standards spanning 50% to 150% of the target or expected concentration [9]. For assay methods, this is often narrowed to the 80-120% range as defined in the regulatory range requirements [22].

- Replication: Each concentration level should be analyzed in triplicate to account for variability and strengthen the statistical evaluation [9].

- Preparation and Order: To avoid propagating systematic errors, standards should be prepared independently rather than through serial dilution from a single stock solution [9]. Furthermore, analyzing standards in a randomized order, rather than in ascending or descending concentration, helps eliminate bias due to instrument drift [9].

Case Study: Impurity Linearity Design

A practical example for an impurity test illustrates the application of these design principles. For an impurity with a specification limit of 0.20%, the linearity levels can be designed from the Quantitation Limit (QL) to 150% of the specification [7].

The table below outlines a typical experimental setup:

| Level | Impurity Value | Impurity Solution Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| QL (0.05%) | 0.05% | 0.5 mcg/ml |

| 50% | 0.10% | 1.0 mcg/ml |

| 70% | 0.14% | 1.4 mcg/ml |

| 100% | 0.20% | 2.0 mcg/ml |

| 130% | 0.26% | 2.6 mcg/ml |

| 150% | 0.30% | 3.0 mcg/ml |

In this design, the range would be reported as QL (0.05%) to 0.30% [7].

Statistical Evaluation and Data Analysis

Once experimental data is collected, rigorous statistical evaluation is essential to confirm linearity. Relying on a single statistical parameter is insufficient; a multi-faceted approach is required.

- Correlation Coefficient (R²): The coefficient of determination (R²) is a commonly used metric. For a method to be considered linear, an R² value exceeding 0.995 (or often 0.997 in practice) is typically required [9] [7]. However, a high R² value alone does not guarantee linearity, as it can mask systematic biases or non-linear patterns [9] [10].

- Residual Plots: Visual inspection of residual plots is a critical and mandatory step [9]. Residuals (the differences between the observed data points and the fitted regression line) should be randomly scattered around zero. Any discernible pattern (e.g., a U-shape or funnel shape) indicates a poor model fit and potential non-linearity, even with a high R² [9].

- Regression Model Selection: The most common approach is Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. However, if the data exhibits heteroscedasticity (where the variability of the response changes with concentration), Weighted Least Squares (WLS) regression should be employed to assign appropriate weight to each data point [9]. For complex biological methods, alternative models like a double logarithm function linear fitting have been proposed to directly demonstrate the proportionality between theoretical and measured values, aligning with the ICH definition of linearity [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the statistical evaluation of linearity data:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful linearity study requires careful preparation and the use of high-quality materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in the experimental process.

| Item | Function in Linearity & Range Studies |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | High-purity analyte used to prepare stock solutions, ensuring accuracy and traceability of the calibration curve [9]. |

| Blank Matrix | The analyte-free sample medium (e.g., placebo, biological fluid, solvent) used to prepare standards, crucial for identifying and accounting for matrix effects [9]. |

| Calibrated Pipettes & Balances | Precision instruments essential for accurate volumetric and gravimetric measurements during serial dilution and standard preparation [9]. |

| Independent Stock Solutions | Separately prepared stock solutions used to create concentration levels, minimizing the risk of propagating a single preparation error [9]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | For HPLC/UV methods, a high-quality column is vital for achieving the specificity and consistent response required for a linear relationship [15]. |

Troubleshooting Common Linearity Issues

Even with careful design, linearity issues can arise. Systematic troubleshooting is required to identify and address the root cause.

- Problem: Non-Linear Patterns in Residuals. A U-shaped pattern in the residual plot suggests a quadratic relationship, indicating the use of a simple linear model may be inappropriate [9]. Solution: Consider non-linear regression models or transform the data.

- Problem: Heteroscedasticity. A funnel-shaped pattern in the residual plot (where the spread of residuals increases with concentration) violates the constant variance assumption of OLS regression [9]. Solution: Apply a Weighted Least Squares (WLS) regression model to stabilize the variance across the concentration range.

- Problem: Saturation or Contamination. The calibration curve may flatten at high concentrations due to detector saturation or show an elevated baseline from contamination [9]. Solution: Dilute samples to remain within the instrument's dynamic range and ensure cleaning procedures are followed.

- Problem: Matrix Effects. The sample matrix can interfere with the analyte response, causing distortion, particularly at concentration extremes [9]. Solution: Prepare calibration standards in a blank matrix rather than pure solvent, or employ the standard addition method for particularly complex matrices [9].

The experimental workflow for establishing linearity and range, from design to troubleshooting, can be visualized as follows:

The rigorous experimental design of concentration levels and the demonstration of a suitable range are non-negotiable components of analytical method validation. By adhering to regulatory guidelines, employing a minimum of five concentration levels across an appropriate range, and applying thorough statistical evaluation that goes beyond a simple R² value, scientists can ensure their methods are reliable, accurate, and fit-for-purpose. As the regulatory landscape evolves with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, embracing a lifecycle approach from the initial ATP through to routine monitoring will further strengthen the robustness and scientific validity of analytical procedures in drug development.

Linearity for Assay (80-120%), Content Uniformity (70-130%), and Related Substances (QL-120%)

In the pharmaceutical sciences, the validation of analytical methods is a cornerstone for ensuring the identity, potency, quality, and purity of drug substances and products. Among the various validation parameters, demonstrating linearity and establishing the range are fundamental to proving that an analytical procedure can obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a given sample [23] [24]. These parameters are not mere regulatory checkboxes; they provide the scientific evidence that the method is fit for its intended purpose across a specified span of concentrations. This guide objectively compares the experimental approaches and performance data for establishing linearity and range in three critical analytical procedures: assay, content uniformity, and related substances, framed within the broader context of modern Process Analytical Technology (PAT) and quality by design (QbD) principles [25].

The concept of linearity is universally defined as the ability of a method to elicit test results that are proportional to the concentration of the analyte. However, the specific acceptance criteria and experimental range vary significantly depending on the analytical application. The range is subsequently defined as the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels for which suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity have been demonstrated [24]. A clear understanding of these parameters, and the distinct requirements for different test procedures, is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to generate reliable and defensible analytical data.

Comparative Analysis of Linearity Requirements

The experimental design for demonstrating linearity is tailored to the specific analytical task. The following table summarizes the key requirements for the three primary procedures discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Linearity and Range Requirements for Key Analytical Procedures

| Analytical Procedure | Typical Concentration Range | Key Performance Indicators | Common Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay | 80% - 120% of the target concentration [26] | High correlation coefficient (R²), low root-mean-square error, slope and intercept of the regression line [24] | HPLC, UV-Vis Spectrophotometry [26] |

| Content Uniformity | 70% - 130% of the target unit content [26] | Accuracy (e.g., % recovery), Precision [26] | Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy [27], UV-Vis Spectrophotometry [26] |

| Related Substances | Quantitation Limit (QL) to 120% of the specification level [23] | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (for QL), Precision at the LOQ, Linearity across the range [24] | HPLC, Mass Spectrometry [25] |

Strategic Selection of Analytical Techniques

The choice of analytical technology is critical and is increasingly influenced by the drive for efficiency and real-time monitoring.

- Traditional vs. PAT Approaches: While High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) remains a gold standard for its high selectivity, modern PAT tools like Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy are revolutionizing control strategies, particularly for content uniformity. A 2025 study demonstrated that NIR transmission spectroscopy could assess content uniformity at speeds of up to 250,000 tablets per hour while maintaining a high correlation (R² = 0.9979) with HPLC results and meeting the ±15% content uniformity requirement [27].

- Advanced Spectrophotometry: For the simultaneous analysis of compounds with overlapping spectra, advanced spectrophotometric methods are emerging as green, cost-effective alternatives to chromatography. Techniques such as the Factorized Derivative Method (FDM) and Factorized Ratio Difference Method (FRM) can resolve mixtures without preliminary separation, validating linearity over ranges like 3–45 μg/mL for specific active ingredients [26].

- Regulatory Alignment: Ultimately, the integration of these technologies into a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) framework is paramount. The ultimate goal of PAT is not only process monitoring but also to validate and ensure GMP compliance, thus guaranteeing safe, effective, and quality-controlled products [25].

Experimental Protocols for Linearity Assessment

A robust linearity experiment follows a systematic workflow. The diagram below outlines the general protocol, which is then adapted for each specific analytical procedure.

Figure 1: General workflow for a linearity experiment, applicable to assay, content uniformity, and related substances testing.

Detailed Methodologies by Application

Protocol for Assay (80-120%)

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of five standard solutions spanning 80%, 90%, 100%, 110%, and 120% of the target assay concentration. The solutions should be prepared in the same matrix (e.g., placebo blend or solvent) to account for any matrix effects [28] [24].

- Analysis and Data Collection: Analyze each solution in duplicate or triplicate using the finalized chromatographic or spectroscopic conditions. Record the analytical response (e.g., peak area in HPLC, absorbance in UV-Vis).

- Data Analysis: Plot the mean response (y-axis) against the concentration (x-axis). Perform linear regression analysis to determine the slope, y-intercept, and coefficient of determination (R²). The method is considered linear if the R² value is ≥ 0.998 and the y-intercept is not significantly different from zero [24].

Protocol for Content Uniformity (70-130%)

- Sample Preparation: For non-PAT methods, prepare standard solutions at concentrations of 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%, 110%, 120%, and 130% of the label claim. For PAT methods like NIR, a calibration set is created using tablets with known API content, often determined by a primary method like HPLC [27] [26].

- Model Development (for PAT): In NIR methods, a chemometric model is developed to correlate the spectral data with the API content. The model's performance is validated against a reference method, with key metrics being the root-mean-square error of prediction (RMSEP) and correlation. A 2025 study achieved an RMSEP of 1.09% using NIR transmission, well within acceptable limits for content uniformity [27].

- Accuracy and Precision: The method must demonstrate accuracy (e.g., % recovery of 98-102%) and precision (e.g., %RSD < 2%) across the range to ensure each dosage unit meets the required specifications [26].

Protocol for Related Substances (QL-120%)

- Determination of QL: The Quantitation Limit (QL or LOQ) must first be established. This can be done based on a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1, or through a calibration-based approach using the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve: QL = 10σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [24].

- Linearity Experiment: Prepare standard solutions of the impurity from the QL up to 120% of the specified limit (e.g., if the specification is 0.5%, the upper limit would be 0.6%). A minimum of five concentration levels is recommended.

- Data Analysis: Perform linear regression. While a high R² is desirable, the critical acceptance criterion is the precision and accuracy at the LOQ, typically requiring an %RSD of ≤ 10% and a recovery of 80-120% [24].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in conducting the linearity experiments described.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Linearity Validation

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for preparing calibration solutions with known concentrations; purity is critical for accurate results. |

| Placebo Matrix | Used in assay and content uniformity to assess selectivity and ensure the analytical signal is specific to the analyte without matrix interference [24]. |

| Appropriate Solvent/Mobile Phase | Dissolves the analyte and reference standards; its compatibility with the analyte and the analytical system is vital [26]. |

| Chemometric Software | Essential for developing multivariate calibration models in PAT applications like NIR spectroscopy [25] [27]. |

| System Suitability Standards | Verifies that the analytical system (e.g., HPLC, spectrophotometer) is performing adequately before and during the linearity experiment. |

The experimental demonstration of linearity and range is a critical, application-specific undertaking in analytical method validation. As this guide has detailed, the protocols and acceptance criteria diverge significantly for assay (80-120%), content uniformity (70-130%), and related substances (QL-120%) testing. The data confirms that while traditional chromatographic methods provide high accuracy and specificity, emerging PAT tools like NIR spectroscopy offer a powerful, high-throughput alternative for applications like content uniformity, achieving real-time monitoring at industrial production speeds [27]. Furthermore, advanced, "green" spectrophotometric methods continue to evolve, providing robust, cost-effective solutions for specific quantification challenges [26]. For scientists and drug development professionals, the strategic selection of an analytical technique, followed by a rigorously designed and executed linearity study, is indispensable for ensuring product quality, streamlining manufacturing processes, and meeting stringent regulatory standards in the modern pharmaceutical landscape.

In analytical method validation, the reliability of any result is contingent upon the quality of the standards from which calibration curves are derived. Proper preparation of stock solutions and serial dilutions forms the foundational step in demonstrating method linearity—the ability of a procedure to produce results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a given range [9] [29]. This guide objectively compares single-step versus serial dilution methodologies, providing supporting experimental data to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select the optimal approach for their specific analytical applications, particularly within the framework of linearity and range validation.

Comparative Analysis: Single-Step vs. Serial Dilution Methods

The choice between single-step and serial dilution strategies involves balancing measurement uncertainty, resource consumption, and practical efficiency. The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of each approach based on experimental data.

| Characteristic | Single-Step Dilution | Serial Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Standard Uncertainty (%) | 0.10% (20→1000 mL) to 0.40% (1→50 mL) [30] | 0.40% (two-step 1→5, then 1→10) [30] |

| Solvent & Solute Consumption | Higher | Significantly lower |

| Operational Efficiency | Fewer steps, lower risk of operator error | Multiple steps, higher cumulative error risk |

| Typical Application | Assay standards where highest accuracy is critical [30] | Preparing a wide range of concentrations for linearity testing [9] [4] |

| Impact on Linearity Validation | Superior for minimizing volumetric uncertainty in final working standards [30] | Essential for establishing the calibration curve across the specified range [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Standard Preparation and Validation

Protocol 1: Preparing Stock Solutions and Single-Step Dilutions

This protocol aims to create a working standard with minimal volumetric uncertainty, ideal for assay standardization.

- Materials: Analytical balance, primary reference standard, appropriate solvent, volumetric flasks (Grade A), pipettes (Grade A).

- Procedure:

- Accurately weigh the specified quantity of analyte using an analytical balance.

- Transfer quantitatively to a volumetric flask and dissolve in a portion of solvent.

- Dilute to the mark with solvent and mix thoroughly to create the stock solution.

- For a single-step dilution, use the largest practical pipette and volumetric flask combination (e.g., a 20 mL pipette and a 1000 mL flask) to transfer and dilute the stock to the final working concentration [30].

- Data Interpretation: The chosen glassware combination directly dictates the theoretical relative standard uncertainty. Refer to tolerance tables for Grade A glassware to calculate the propagated uncertainty for the dilution sequence [30].

Protocol 2: Performing Serial Dilutions for Linearity Curves

This protocol is used to generate multiple concentration levels across the validated range for constructing a calibration curve.

- Materials: Stock solution, appropriate diluent (e.g., blank matrix), series of volumetric flasks or tubes, pipettes.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a high-concentration stock solution in the desired matrix or solvent.

- Perform a series of factored dilutions. For example, to create a 2-fold serial dilution, transfer 1 volume of solution into 1 volume of diluent and mix thoroughly. This becomes the next, half-concentration solution in the series [31] [32].

- Repeat the process sequentially to generate the required number of concentration levels (typically at least five for linearity validation) [9] [4].

- Data Interpretation: The resulting concentrations are plotted against instrument response. The linearity is evaluated via the coefficient of determination (R²), which should typically exceed 0.995 or 0.997 [9] [4]. Visually inspect residual plots to detect any non-linear patterns that a high R² value might mask [9].

Protocol 3: Validating Dilution Accuracy via Spike-and-Recovery

This experiment tests whether the sample matrix affects the accurate quantification of the analyte, which is crucial for validating dilution linearity in complex matrices like serum or urine [31] [32].

- Materials: Known analyte standard, blank sample matrix, assay diluent, standard analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC, ELISA plate reader).

- Procedure:

- Spike a known amount of the pure analyte into the sample matrix. In parallel, prepare an identical spike in the assay diluent.

- Analyze both samples and calculate the recovered concentration for each using a standard curve.

- Calculate the percent recovery: (Observed concentration in matrix / Observed concentration in diluent) × 100% [32].

- Data Interpretation: Recovery percentages between 80% and 120% are generally considered acceptable, indicating minimal matrix interference [31] [32]. Poor recovery suggests the matrix is affecting detection and the standard diluent or sample preparation method must be adjusted [32].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table details essential materials and their functions in standard preparation and validation workflows.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Primary Reference Standard | High-purity material of known composition used to prepare the primary stock solution for accurate quantification [30]. |

| Blank Matrix | The analyte-free biological fluid or sample material (e.g., serum, plasma, urine) used to prepare matrix-matched standards and assess matrix effects [31] [32]. |

| Grade A Volumetric Glassware | Glassware (flasks, pipettes) meeting high-precision tolerance standards to minimize systematic error in volume measurements [30]. |

| Appropriate Solvent/Diluent | A solvent that completely dissolves the analyte and is compatible with both the chemical stability of the analyte and the subsequent analytical technique (e.g., HPLC mobile phase, ELISA buffer) [31]. |

Workflow Visualization for Standard Preparation and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points involved in preparing and validating analytical standards, integrating both preparation methods and validation experiments.

Standard Preparation and Validation Workflow

The preparation of stock solutions and serial dilutions is a critical laboratory operation that directly impacts the success of analytical method validation, particularly for establishing linearity and range. While single-step dilutions provide superior accuracy for individual working standards, serial dilutions are indispensable for efficiently generating the multi-point concentrations required for calibration curves. The optimal strategy is dictated by the specific application: use single-step dilutions when volumetric accuracy for a single point is paramount, and employ serial dilutions to define the analytical range with minimal resource expenditure. Validating these procedures through spike-and-recovery and linearity-of-dilution experiments is essential to ensure the reliability of results, especially when working with complex sample matrices that can introduce interference. By adhering to these best practices, researchers can ensure the integrity of their standard preparations and the validity of their analytical data.

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical development, the validation of analytical procedures is paramount to ensuring the safety, quality, and efficacy of drug substances and products. Linearity and range validation stand as critical components within this framework, demonstrating that an analytical method can obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range. The correlation coefficient (R²), slope, and y-intercept serve as the fundamental statistical triad for evaluating this linear relationship. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the acceptance criteria and interpretation strategies for these key parameters, equipping scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge to robustly validate their analytical methods in compliance with regulatory standards such as ICH Q2(R2) [17].

The Statistical Triad: Definitions and Regulatory Significance

Correlation Coefficient (R²)

The coefficient of determination (R²) is a statistical measure that quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable(s) [33]. In the context of analytical method validation, it represents the percentage of the response (e.g., instrument signal) variation that is explained by the concentration of the analyte.

- Interpretation: R² is always between 0 and 100% [34] [35]. A value of 0% indicates the model explains none of the variability of the response data around its mean, while 100% indicates that it explains all the variability [35].

- Visual Clue: In a calibration curve, a high R² value generally means the observed data points are close to the fitted regression line [33].

Slope

The slope of the regression line represents the sensitivity of the analytical method. It indicates the mean change in the response variable (e.g., peak area) for a one-unit change in the independent variable (concentration). A steeper slope suggests the method is more sensitive to changes in analyte concentration.

Y-Intercept

The y-intercept indicates the expected mean response value when the analyte concentration is zero. In an ideal calibration curve for methods without a background signal, the intercept would not be significantly different from zero. A significant positive or negative intercept can suggest the presence of systematic error or background interference.

Comparative Analysis of Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria for linearity parameters can vary based on the specific analytical method, the nature of the analyte, and the regulatory context. The following table summarizes typical acceptance criteria for the statistical triad in analytical method validation.

Table 1: Acceptance Criteria for Linearity Parameters in Analytical Method Validation

| Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criterion | Rationale & Context |

|---|---|---|